Validating Simulated DBTL Cycles: A Framework for Robust Computational Models in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of simulated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles, a critical component of modern computational biomedical research.

Validating Simulated DBTL Cycles: A Framework for Robust Computational Models in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of simulated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles, a critical component of modern computational biomedical research. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges the gap between model development and real-world application. We explore the foundational principles of model validation, detail methodological approaches and their applications across domains like musculoskeletal modeling and survival analysis, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present rigorous techniques for comparative and predictive validation. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to build, evaluate, and trust computational models that accelerate discovery and improve clinical translation.

The Pillars of Trust: Foundational Principles for Simulated DBTL Model Validation

Defining Validation and Verification in the Context of DBTL Cycles

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a fundamental engineering framework in synthetic biology and drug development, providing a systematic, iterative process for engineering biological systems [1]. Within this framework, verification and validation serve as critical quality assurance processes that ensure reliability and functionality throughout the development pipeline. Verification answers the question "Did we build the system correctly?" by confirming that implementation matches specifications, while validation addresses "Did we build the correct system?" by demonstrating the system meets intended user needs and performance requirements under expected operating conditions [2] [3]. These processes are particularly crucial in regulated environments like pharmaceutical development, where the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed approaches that encourage the use of designed experiments for validation [2].

The DBTL cycle begins with the Design phase, where researchers define objectives and design biological parts or systems using computational modeling and domain knowledge [1]. The Build phase involves synthesizing DNA constructs and assembling them into vectors for introduction into characterization systems. The Test phase experimentally measures the performance of engineered biological constructs, while the Learn phase analyzes collected data to inform the next design iteration [1]. Verification activities occur primarily during the Build and Test phases, ensuring proper construction and function, while validation typically occurs after successful verification to demonstrate fitness for purpose.

Recent advances have introduced variations to the traditional DBTL cycle, including LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test), where machine learning and prior knowledge precede initial design, potentially reducing iteration needs [1]. Additionally, the knowledge-driven DBTL cycle incorporates upstream in vitro investigation to provide mechanistic understanding before full DBTL cycling [4]. These evolving approaches maintain verification and validation as essential components for ensuring robust outcomes in biological engineering.

Methodological Approaches for Verification and Validation

Design of Experiments (DOE) for Validation

Design of Experiments (DOE) represents a powerful statistical approach for validation that systematically challenges processes to discover how outputs change as variables fluctuate within allowable limits [3]. Unlike traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches that vary factors individually while holding others constant, DOE simultaneously varies multiple factors across their specified ranges, enabling researchers to identify significant factors, understand factor relationships, and detect interactions where the effect of one factor depends on another [5]. This capability to reveal interactions is particularly valuable, as OFAT methods always miss these critical relationships [2].

The application of DOE in validation follows a structured process. Researchers first identify potential factors that could affect performance, including quantitative variables (e.g., temperature, concentration) tested at extreme specifications and qualitative factors (e.g., reagent suppliers) tested across available options [2]. Using specialized arrays like Taguchi L12 arrays or saturated fractional factorial designs, researchers can minimize trials while ensuring all possible factor combinations are tested to detect unwelcome interactions [2]. For example, a highly fractionated two-level factorial design testing six factors required only eight runs instead of 64 for a full factorial approach [3].

The analysis phase uses statistical methods like analysis of variance (ANOVA) and half-normal probability plots to identify significant effects and determine whether results remain within specification across all tested conditions [3]. When validation fails or aliasing (correlation between factors) occurs, follow-up strategies like foldover designs can reverse variable levels to eliminate aliasing and identify true causes [3]. This systematic approach typically halves the number of trials compared to traditional methods while providing more comprehensive validation [2].

Verification Methods in DBTL Cycles

Verification in DBTL cycles employs distinct methodologies focused on confirming proper implementation at each development stage. During the Build phase, verification techniques include PCR amplification, Sanger sequencing, and restriction digestion to confirm genetic constructs match intended designs [6] [7]. For instance, the Lyon iGEM team used colony PCR and Sanger sequencing to verify plasmid construction, discovering through repeated failures that their Gibson assembly was producing only empty backbones despite multiple optimization attempts [7].

In the Test phase, verification focuses on confirming that individual components function as specified before overall system validation. The Wist iGEM team employed meticulous control groups including negative controls (lacking key components) and positive controls (known functional elements) to verify their cell-free arsenic biosensor performance [6]. Similarly, fluorescence measurements with controls verified proper functioning of individual promoters before overall biosensor validation [7].

Analytical methods form another critical verification component, with techniques like mass spectrometry verifying chemical production in metabolic engineering projects [4]. The knowledge-driven DBTL cycle for dopamine production used high-performance liquid chromatography to verify dopamine titers and confirm pathway functionality before proceeding to validation [4].

Comparative Experimental Data Across DBTL Applications

Case Study: Dopamine Production Optimization

A recent study demonstrating dopamine production in Escherichia coli provides quantitative data comparing different DBTL approaches [4]. The knowledge-driven DBTL cycle, incorporating upstream in vitro investigation, achieved significant improvements over traditional methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Dopamine Production Strains

| Engineering Approach | Dopamine Concentration (mg/L) | Specific Yield (mg/g biomass) | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| State-of-the-art (previous) | 27.0 | 5.17 | 1.0 (baseline) |

| Knowledge-driven DBTL | 69.03 ± 1.2 | 34.34 ± 0.59 | 2.6 (concentration) / 6.6 (yield) |

The experimental protocol for this case involved several key stages [4]. First, researchers engineered an E. coli host (FUS4.T2) for high L-tyrosine production by depleting the transcriptional dual regulator TyrR and introducing feedback inhibition mutations in tyrA. The dopamine pathway was constructed using genes encoding 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase (HpaBC) from native E. coli and L-DOPA decarboxylase (Ddc) from Pseudomonas putida in a pET plasmid system. For in vitro testing, crude cell lysate systems were prepared with reaction buffer containing FeCl₂, vitamin B₆, and L-tyrosine or L-DOPA supplements. High-throughput RBS engineering modulated translation initiation rates by varying Shine-Dalgarno sequences while maintaining secondary structure. Dopamine quantification used HPLC analysis with standards, validating assay robustness through spike-recovery experiments.

Case Study: Cell-Free Biosensor Development

The Wist iGEM team's development of a cell-free arsenic biosensor demonstrates DBTL iteration with quantitative performance data across multiple cycles [6].

Table 2: Arsenic Biosensor Performance Across DBTL Cycles

| DBTL Cycle | Key Parameter Adjusted | Detection Range | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 5 | Plasmid pair combination | Not achieved | Not achieved | High background |

| Cycle 6 | Incubation conditions (temperature/time) | Not achieved | Incomplete reactions | Variable |

| Cycle 7 | Plasmid concentration ratio (1:10) | 5-100 ppb | Reliable at 50 ppb | Optimized dynamic range |

The experimental methodology for this project involved specific protocols for each phase [6]. For the Build phase, the team prepared master mixes containing buffer, lysate, RNA polymerase, RNase inhibitor, and nuclease-free water. Sense plasmids (A, B, and E) were incubated at 37°C for one hour to produce ArsC and ArsR repressors. Reporter plasmids (NoProm and OC2) were added, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. In the Test phase, mixtures were distributed in 96-well plates with DFHBI-1T fluorescent dye, testing across arsenic concentrations (0 ppb and 800 ppb). The final optimized protocol used simultaneous addition of all reagents (lysate, T7 polymerase, plasmids, DFHBI-1T, rice extract) with real-time kinetic analysis over 90 minutes at 37°C. Verification included control groups without reporter plasmids (negative control) and without sense plasmids (positive control), with fluorescence measured using a plate reader.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | Rapid in vitro protein synthesis without cloning steps | Crude cell lysates; >1 g/L protein in <4 hours; scalable pL to kL [1] |

| DNA Assembly Systems | Vector construction and genetic part assembly | Gibson assembly; Golden Gate; SEVA (Standard European Vector Architecture) backbones [7] |

| Reporter Systems | Monitoring gene expression and system performance | LuxCDEAB operon (bioluminescence); GFP/mCherry (fluorescence); RNA aptamers [7] |

| Analytical Instruments | Quantifying outputs and performance metrics | Plate readers (fluorescence/luminescence); HPLC; mass spectrometry [6] [4] |

| Inducible Promoter Systems | Controlled gene expression testing | pTet/pLac with regulatory elements (TetR, LacI); IPTG/anhydrotetracycline inducible [7] |

| Machine Learning Models | Zero-shot prediction and design optimization | ESM; ProGen; ProteinMPNN; Prethermut; Stability Oracle [1] |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualizations

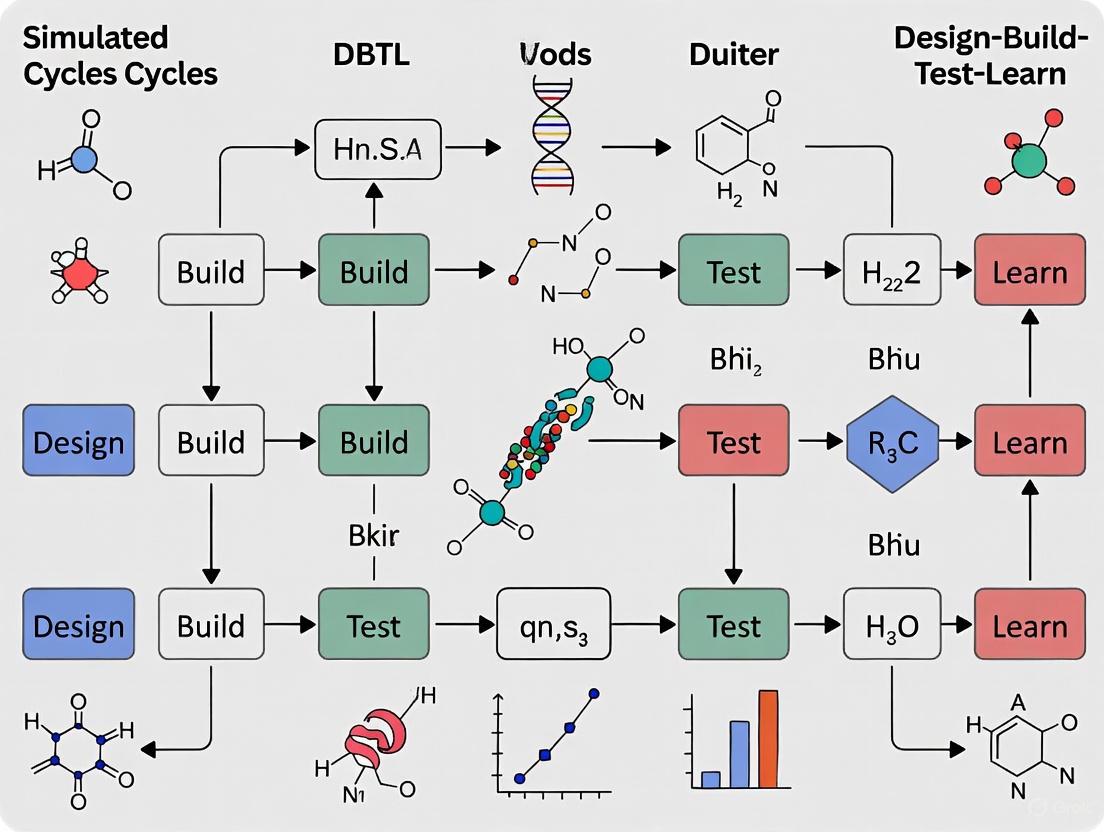

DBTL Cycle with Verification & Validation Checkpoints

Knowledge-Driven DBTL with In Vitro Testing

Arsenic Biosensor Signaling Pathway

Verification and validation represent distinct but complementary processes within DBTL cycles that ensure both correct implementation and fitness for purpose. Methodologies like Design of Experiments provide powerful validation approaches that efficiently challenge systems across expected operating ranges while detecting critical factor interactions that traditional methods miss. Case studies demonstrate that structured approaches incorporating upstream knowledge, whether through machine learning or in vitro testing, can significantly accelerate development timelines and improve outcomes. As DBTL methodologies evolve toward LDBT cycles and increased automation, robust verification and validation practices remain essential for translating engineered biological systems from laboratory research to real-world applications, particularly in regulated fields like drug development where reliability and performance are paramount.

The Critical Role of Validation in Translational Research and Clinical Applications

In translational research, the journey from a computational model to a clinically impactful tool is fraught with challenges. Validation serves as the critical bridge between theoretical innovation and real-world application, ensuring that models are not only statistically sound but also clinically reliable and actionable. As artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) permeate drug development and clinical practice, the rigor of validation methodologies has emerged as the definitive factor determining successful implementation. This comparison guide examines the multifaceted landscape of validation techniques across different computational approaches, providing researchers with a structured framework for evaluating and selecting appropriate validation strategies for their specific contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Performance Across Modeling Approaches

| Modeling Approach | Primary Application Context | Key Validation Metrics | Reported Performance | Validation Strengths | Validation Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning (LSTM) | Equipment failure prediction in industrial systems [8] | MAE: 0.0385, MSE: 0.1085, RMSE: 0.3294 [8] | Statistically significant improvement over Fourier series (p<0.001) [8] | Superior at capturing complex, non-periodic patterns in sequential data; handles high-dimensional sensor data effectively [8] | Requires large labeled datasets; computationally intensive; "black box" interpretation challenges |

| Fourier Series Model | Signal processing for industrial equipment monitoring [8] | Higher MAE, MSE, and RMSE compared to LSTM [8] | Lower predictive accuracy than LSTM for complex failure patterns [8] | Interpretable results; computational efficiency; well-suited for periodic signal analysis [8] | Limited capacity for capturing non-linear, complex failure dynamics [8] |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Personalized longevity intervention recommendations [9] | Balanced accuracy across 5 requirements: Comprehensiveness, Correctness, Usefulness, Explainability, Safety [9] | GPT-4o achieved highest overall accuracy (0.85 comprehensiveness); smaller models (Llama 3.2 3B) performed significantly worse [9] | Capable of processing complex clinical contexts; Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) can improve some metrics [9] | Limited comprehensiveness even in top models; inconsistent RAG benefits; potential age-related biases [9] |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | X-ray image classification for pneumonia detection [10] | Overall classification accuracy | VGGNet achieved 97% accuracy in pneumonia vs. COVID-19 vs. normal lung classification [10] | High accuracy with balanced, curated datasets; effective for image-based clinical tasks [10] | Performance dependent on data curation and augmentation techniques [10] |

| Conventional Biomarker Models | Diagnostic classification in clinical practice [11] | Sensitivity, specificity, likelihood rates, predictive values, AUC-ROC [11] | Many proposed biomarkers fail clinical translation despite statistical significance [11] | Established statistical frameworks; clear regulatory pathways for qualification [11] | Often overestimate clinical utility; between-group significance doesn't ensure classification accuracy [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation Methodologies

Protocol 1: Time-Series Predictive Model Validation

Application Context: Predictive maintenance in industrial settings using sensor data [8]

Experimental Workflow:

- Data Acquisition: Collect multivariate time-series sensor data from industrial equipment, including both normal operation and failure events [8]

- Feature Extraction: Reduce dataset dimensionality while preserving critical signal characteristics relevant to failure prediction [8]

- Model Training: Implement both LSTM and Fourier series models on historical data, using appropriate sequence length and parameter optimization [8]

- Performance Validation: Calculate MAE, MSE, and RMSE for both models on holdout test data [8]

- Statistical Significance Testing: Apply paired t-test to confirm performance differences are statistically significant (p<0.001) [8]

- Residual Analysis: Visualize and analyze prediction residuals to identify systematic errors [8]

Validation Framework:

- Training/validation/test split with chronological partitioning

- k-fold cross-validation with temporal preservation

- Comparison against baseline mathematical models

Protocol 2: LLM Clinical Recommendation Validation

Application Context: Benchmarking LLMs for personalized longevity interventions [9]

Experimental Workflow:

- Test Item Development: Create synthetic medical profiles across different age groups and intervention types [9]

- Prompt Engineering: Develop system prompts of varying complexity addressing clinical requirements [9]

- RAG Implementation: Augment with domain-specific knowledge retrieval where applicable [9]

- LLM-as-Judge Evaluation: Use validated LLM judge with expert-curated ground truths [9]

- Multi-Axis Validation: Assess responses across five requirements: Comprehensiveness, Correctness, Usefulness, Explainability, and Safety [9]

- Statistical Analysis: Compute balanced accuracy metrics and significance testing between models [9]

Validation Framework:

- Human expert-validated ground truths

- Multiple prompting strategies to assess stability

- Cross-comparison of proprietary and open-source models

Protocol 3: Biomarker Classifier Validation

Application Context: Diagnostic biomarker development for clinical application [11]

Experimental Workflow:

- Population Definition: Establish well-defined clinical and healthy comparison groups [11]

- Model Selection: Apply multiple classification algorithms (LASSO, elastic net, random forests) with mathematical model selection [11]

- Comprehensive Metric Assessment: Evaluate sensitivity, specificity, likelihood rates, predictive values, and AUC-ROC with confidence intervals [11]

- Cross-Validation: Implement proper cross-validation techniques avoiding data leakage [11]

- Classification Error Analysis: Calculate probability of classification error (PERROR) rather than relying solely on p-values [11]

- Reliability Testing: Establish test-retest reliability using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) [11]

Validation Framework:

- Sample size determination based on classification objectives

- Multiple classifier comparison

- Rigorous reliability assessment for longitudinal applications

Visualization of DBTL Cycle in Model Validation

DBTL Cycle in Model Validation - This diagram illustrates the iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle that forms the foundation of rigorous model validation in translational research, showing how models progress from development to clinical application.

Visualization of Multi-Dimensional AI Validation Framework

Multi-Dimensional AI Validation Framework - This diagram shows the three critical dimensions of AI model validation in clinical contexts, highlighting how technical performance, clinical utility, and regulatory requirements converge to support prospective evaluation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Medical Profiles | Benchmark test items for LLM validation | Evaluating AI-generated clinical recommendations; consists of 25+ profiles across age groups with 1000+ test cases [9] |

| Multivariate Sensor Datasets | Time-series equipment monitoring data | Predictive maintenance model validation; includes normal and failure state data for industrial equipment [8] |

| Balanced X-ray Image Datasets | Curated medical imaging collection | Pneumonia classification model validation; 6,939 images across normal, bacterial, viral, and COVID-19 categories [10] |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) | Domain knowledge enhancement framework | Improving LLM accuracy by augmenting with external knowledge bases; impacts comprehensiveness and correctness metrics [9] |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Reliability quantification statistic | Measuring test-retest reliability of biomarker panels; essential for longitudinal monitoring applications [11] |

| LLM-as-a-Judge System | Automated evaluation framework | Assessing LLM response quality using validated judge model with expert-curated ground truths [9] |

| Digital Twin Infrastructure | Real-time simulation environment | Validating simulation models against physical systems; enables iterative calibration and DoE validation [12] |

| Elastic Net Model Selection | Feature selection algorithm | Biomarker panel optimization; prevents overfitting and improves interpretability over single-algorithm approaches [11] |

Key Validation Considerations Across Model Types

Performance Metrics Beyond Statistical Significance

Validation must extend beyond traditional p-values to clinically relevant metrics. Between-group statistical significance often fails to translate to classification accuracy, with examples showing p=2×10⁻¹¹ but classification error P_ERROR=0.4078 (barely better than random) [11]. Comprehensive biomarker validation should include sensitivity, specificity, likelihood rates, predictive values, false discovery rates, and AUC-ROC with confidence intervals [11]. For predictive models, error metrics like MAE, MSE, and RMSE provide more actionable performance assessment [8].

Prospective Clinical Validation as Critical Gate

Most AI tools remain confined to retrospective validation, creating a significant translation gap. Prospective evaluation in clinical trials is essential for assessing real-world performance, with randomized controlled trials (RCTs) representing the gold standard for models claiming clinical impact [13]. The requirement for RCT evidence correlates directly with the innovativeness of AI claims - more transformative solutions require more comprehensive validation [13].

Reliability and Longitudinal Performance

For monitoring biomarkers, test-retest reliability establishes the foundation for longitudinal utility. Reliability should be quantified using appropriate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) rather than linear correlation, with careful selection from multiple ICC variants depending on study design [11]. The minimum detectable difference must be distinguished from the minimal clinically important difference to ensure practical utility [11].

Model Selection and Cross-Validation Rigor

Proper model selection using mathematically informed approaches like LASSO, elastic net, or random forests prevents overfitting and improves generalizability [11]. Cross-validation, while commonly used, is vulnerable to misapplication that can produce misleadingly optimistic results (>0.95 sensitivity/specificity) with random data [11]. Best practices recommend repeating classification problems with multiple algorithms and investigating significant divergences in performance [11].

Validation represents the critical pathway from computational innovation to clinical impact in translational research. As demonstrated across diverse applications from industrial predictive maintenance to clinical decision support, rigorous multi-dimensional validation frameworks are essential for establishing real-world utility. The most successful approaches integrate technical performance metrics with clinical relevance assessments and regulatory considerations, employing prospective validation in realistic environments. By adopting the comprehensive validation strategies outlined in this guide, researchers can significantly improve the translation rate of computational models into clinically impactful tools that advance patient care and therapeutic development.

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a foundational framework in modern synthetic biology and biomanufacturing, enabling iterative optimization of biological systems for diverse applications. This cyclical process involves designing genetic constructs or microbial strains, building these designs in the laboratory, testing their performance through rigorous experimentation, and learning from the results to inform subsequent design iterations [4]. As the complexity of engineered biological systems increases, particularly in pharmaceutical development, the validation of DBTL models has emerged as a critical challenge. Effective validation ensures that predictive models accurately reflect biological reality, thereby reducing development timelines and improving the success rate of engineered biological products.

The validation of DBTL cycles is particularly crucial in drug development, where regulatory requirements demand rigorous demonstration of product safety, efficacy, and consistency. Current validation practices span multiple domains, from biosensor development for metabolite detection to optimization of microbial strains for therapeutic compound production. However, significant gaps remain in standardization, reproducibility, and predictive accuracy across different biological contexts and scales. This review examines current validation methodologies within DBTL frameworks, identifies persistent gaps, and explores emerging solutions to enhance the reliability of biological models in pharmaceutical applications.

Current Validation Methodologies in DBTL Cycles

Biosensor Validation for Metabolic Engineering

Biosensors function as critical validation tools within DBTL cycles, enabling real-time monitoring of metabolic pathways and dynamic regulation of engineered systems. Recent research has demonstrated the development and validation of transcription factor-based biosensors for applications in precision biomanufacturing. In one significant study, researchers assembled a library of FdeR biosensors for naringenin detection, characterizing their performance under diverse conditions to build a mechanistic-guided machine learning model that predicts biosensor behavior across genetic and environmental contexts [14].

The validation methodology employed in this study involved a comprehensive experimental design assessing 17 distinct genetic constructs under 16 different environmental conditions, including variations in media composition and carbon sources. This systematic approach enabled researchers to quantify context-dependent effects on biosensor dynamics, a crucial validation step for applications in industrial fermentation processes where environmental conditions frequently vary. The validation process incorporated both mechanistic modeling and machine learning approaches, creating a predictive framework that could determine optimal biosensor configurations for specific applications, such as screening or dynamic pathway regulation [14].

Strain Optimization for Therapeutic Compound Production

Microbial strain optimization represents another domain where DBTL validation practices have advanced significantly. A notable example involves the development of an Escherichia coli strain for dopamine production, a compound with applications in emergency medicine and cancer treatment. The validation approach implemented a "knowledge-driven DBTL" cycle that incorporated upstream in vitro investigations to guide rational strain engineering [4].

The validation methodology included several crucial components. First, researchers conducted in vitro cell lysate studies to assess enzyme expression levels before implementing changes in vivo. These results were then translated to the in vivo environment through high-throughput ribosome binding site (RBS) engineering, enabling precise fine-tuning of pathway expression. The validation process quantified dopamine production yields, achieving concentrations of 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L (equivalent to 34.34 ± 0.59 mg/g biomass), representing a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over previous state-of-the-art production methods [4]. This validation approach demonstrated the value of integrating in vitro and in vivo analyses to reduce iterative cycling and enhance strain development efficiency.

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Validated Biological Systems in DBTL Cycles

| Biological System | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Validation Results | Validation Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine Production Strain [4] | Production titer, Yield per biomass | 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L, 34.34 ± 0.59 mg/g biomass | In vitro lysate studies + high-throughput RBS engineering |

| Naringenin Biosensor Library [14] | Dynamic range, Context dependence | Significant variation across 16 environmental conditions | Mechanistic-guided machine learning across genetic/environmental contexts |

| Automated Protein Evolution Platform [15] | Enzyme activity improvement, Process duration | 2.4-fold activity improvement in 10 days | Closed-loop system with PLM design and biofoundry testing |

Automated Protein Engineering Platforms

Recent advances in protein engineering have incorporated DBTL cycles within fully automated biofoundry environments. One study developed a protein language model-enabled automatic evolution (PLMeAE) platform that integrated machine learning with robotic experimentation for tRNA synthetase engineering [15]. The validation framework for this system employed a closed-loop approach where protein language models (ESM-2) made zero-shot predictions of 96 variants to initiate the cycle, with a biofoundry constructing and evaluating these variants.

The validation methodology included multiple rounds of iterative optimization, with experimental results fed back to train a fitness predictor based on a multi-layer perceptron model. This approach enabled a 2.4-fold improvement in enzyme activity over four evolution rounds completed within 10 days [15]. The validation process demonstrated superior performance compared to random selection and traditional directed evolution strategies, highlighting the value of integrated computational and experimental validation frameworks.

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for DBTL Validation Methods

| Validation Method | Key Procedural Steps | Experimental Parameters Measured | Analytical Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biosensor Response Characterization [14] | 1. Library construction with combinatorial parts assembly2. Growth under reference conditions3. Fluorescence measurement with ligand exposure4. Testing across environmental contexts | Fluorescence intensity, Response dynamics, Dynamic range, Sensitivity | Mechanistic modeling, Machine learning prediction, D-optimal experimental design |

| Knowledge-Driven Strain Engineering [4] | 1. In vitro cell lysate studies2. Translation to in vivo via RBS engineering3. High-throughput screening4. Production yield quantification | Enzyme activity, Pathway flux, Final product titer, Biomass yield | Statistical evaluation, Comparative analysis against benchmarks, Pathway flux analysis |

| Automated Protein Evolution [15] | 1. Zero-shot variant prediction by PLMs2. Automated DNA construction3. High-throughput expression and screening4. Fitness predictor training | Enzyme activity, Expression levels, Thermal stability, Specificity | Bayesian optimization, Multi-layer perceptron training, Sequence-function mapping |

Critical Gaps in Current Validation Practices

Reproducibility Across Biological Contexts

A significant validation gap identified across multiple studies concerns the reproducibility of DBTL outcomes across different biological contexts. The naringenin biosensor study explicitly demonstrated that biosensor performance varied substantially across different media compositions and carbon sources [14]. This context dependence presents a critical validation challenge for pharmaceutical applications, where consistent performance across production scales and conditions is essential for regulatory approval and manufacturing consistency.

The dopamine production study further highlighted how cellular regulation and metabolic burden can alter the performance of engineered pathways when transferred from in vitro to in vivo environments [4]. This transition between experimental contexts represents a persistent validation challenge, as predictive models trained on in vitro data often fail to accurately forecast in vivo behavior due to the complexity of cellular regulation and resource allocation.

Standardization of Validation Metrics

The analysis of current DBTL validation practices reveals a substantial lack of standardized metrics and protocols across different research domains. Each study examined employed distinct validation criteria, measurement techniques, and reporting standards, making cross-comparison and replication challenging. For instance, while the dopamine production study focused on production titers and yield per biomass [4], the biosensor validation emphasized dynamic range and context dependence [14], and the protein engineering study prioritized enzyme activity improvements and process efficiency [15].

This metric variability reflects a broader gap in validation standardization, particularly concerning the assessment of model predictive accuracy, uncertainty quantification, and scalability predictions. The absence of standardized validation protocols hinders the translation of research findings from academic settings to industrial pharmaceutical applications, where regulatory requirements demand rigorous and standardized validation approaches.

Emerging Solutions and Future Directions

Integrated Computational-Experimental Frameworks

Recent advances in DBTL validation emphasize the integration of computational modeling with high-throughput experimental validation. The protein language model-enabled automatic evolution platform represents a promising approach, combining the predictive power of protein language models with automated biofoundry operations [15]. This integrated framework addresses validation gaps by enabling rapid iteration between computational predictions and experimental validation, enhancing model accuracy through continuous learning.

Similarly, the mechanistic-guided machine learning approach developed for biosensor validation offers a template for addressing context-dependent performance challenges [14]. By combining mechanistic understanding with data-driven modeling, this approach improves the predictive accuracy of biosensor behavior across diverse environmental conditions, potentially addressing the reproducibility gaps observed in current validation practices.

Knowledge-Driven DBTL Cycles

The knowledge-driven DBTL cycle implemented in the dopamine production study offers another promising validation approach [4]. By incorporating upstream in vitro investigations before proceeding to in vivo implementation, this methodology enhances the efficiency of the validation process and reduces the number of cycles required to achieve performance targets. This approach addresses resource and timeline gaps in conventional DBTL validation, particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development where development speed impacts clinical translation.

Diagram 1: Integrated DBTL Cycle Framework for Enhanced Validation. The diagram illustrates the integration of computational and experimental components within the DBTL cycle, highlighting how in vitro studies, computational modeling, high-throughput screening, and in vivo validation interact with the core cycle phases to enhance validation robustness.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Validation

The implementation of robust DBTL validation requires specialized research reagents and materials tailored to specific validation challenges. The following table summarizes key reagent solutions identified across the examined studies, along with their functions in the validation process:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Examples | Validation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems [4] | Bypass cellular constraints for preliminary pathway validation | Testing enzyme expression levels before in vivo implementation | Knowledge-driven DBTL cycles |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Libraries [4] | Fine-tune gene expression levels in metabolic pathways | Optimizing relative expression of dopamine pathway enzymes | High-throughput strain optimization |

| Reporter Plasmids with Fluorescent Proteins [14] | Quantify biosensor response dynamics and sensitivity | Characterizing naringenin biosensor performance across conditions | Biosensor validation |

| Automated Biofoundry Components [15] | Enable high-throughput construction and testing of variants | Robotic protein engineering with continuous data collection | Automated DBTL platforms |

| Specialized Growth Media Formulations [4] [14] | Assess context-dependence under different nutrient conditions | Testing biosensor performance across media and carbon sources | Context-dependence validation |

| Inducer Compounds [4] | Control timing and level of gene expression in engineered systems | Regulating pathway enzyme expression in dopamine production | Metabolic engineering validation |

The validation of DBTL cycles represents a critical frontier in synthetic biology and pharmaceutical development. Current practices have advanced significantly through the integration of computational modeling, high-throughput experimentation, and knowledge-driven approaches. However, substantial gaps remain in standardization, reproducibility across biological contexts, and predictive accuracy for industrial-scale applications. Emerging solutions that combine mechanistic modeling with machine learning, incorporate upstream in vitro validation, and leverage automated biofoundries offer promising pathways to address these limitations. As DBTL methodologies continue to evolve, developing robust, standardized validation frameworks will be essential for translating engineered biological systems from research laboratories to clinical applications, ultimately accelerating drug development and biomanufacturing innovation.

In metabolic engineering and drug discovery, the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a central framework for iterative optimization. Simulated DBTL cycles, which use computational models to predict outcomes before costly laboratory experiments, have become crucial for accelerating research. The core of these simulations lies in the sophisticated interplay between different model types, each with distinct strengths and applications. Mechanistic models, grounded in established biological and chemical principles, provide a deep understanding of underlying processes but are often computationally demanding. In contrast, machine learning (ML) models can identify complex patterns from data and make rapid predictions but may lack inherent explainability. This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and validation of these model types within the context of simulated DBTL cycles, providing researchers with the data and methodologies needed to select the right tool for their projects [16] [17].

Model Type Comparison: Characteristics and Workflows

Defining the Model Types

- Mechanistic Models: These models are built from first principles, using mathematical equations to represent our understanding of biological systems, such as metabolic pathways or cell physiology. They are often formulated using Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) or Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs) to describe the dynamics of system components [16] [17]. For example, a mechanistic model might represent a metabolic pathway integrated into an E. coli core kinetic model to simulate the production of a target compound [16].

- Machine Learning (ML) Models: These are data-driven models that learn input-output relationships from existing data without explicit pre-programmed rules. In DBTL cycles, supervised learning models like gradient boosting and random forests are commonly used to predict strain performance based on genetic designs [16].

- Hybrid/Surrogate ML Models: This approach bridges the gap between the two paradigms. A surrogate ML model is trained to approximate the input-output behavior of a complex mechanistic model. Once built, the surrogate can replace the original model for many tasks, offering simulations that are several orders of magnitude faster [17].

Comparative Analysis of Model Characteristics

The table below summarizes the core differences between these model types.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Different Model Types in Simulated DBTL Cycles

| Characteristic | Mechanistic Models | Machine Learning Models | Surrogate ML Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | First principles (e.g., laws of mass action) [16] | Statistical patterns in data [16] | Approximation of a mechanistic model [17] |

| Interpretability | High (parameters are biologically relevant) [16] | Low to Moderate (often "black box") [16] | Inherits interpretability limitations of ML |

| Computational Demand | High (simulations can take hours/days) [17] | Low (after training, prediction is fast) [16] | Very Low (fast execution once trained) [17] |

| Data Requirements | Lower (relies on established theory) | High (performance depends on data volume/quality) [16] | High (requires many runs of the mechanistic model for training) [17] |

| Typical Applications in DBTL | Exploring pathway dynamics, in-silico hypothesis testing [16] | Recommending new strain designs, predicting TYR values [16] | Rapid parameter space exploration, sensitivity analysis, real-time decision support [17] |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways in DBTL Cycles

The DBTL cycle provides a structured framework for strain optimization. The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow and how different models integrate into this process.

Diagram 1: The DBTL cycle and model integration.

The "Learn" phase is where model training and validation occur. Data from the "Test" phase is used to calibrate mechanistic models or train ML models. These models then feed into the next "Design" phase, proposing promising new genetic configurations to test. Surrogate models, trained on data generated by the mechanistic model, can be inserted into this cycle to rapidly pre-screen designs in silico before committing to laboratory work [16] [17].

Performance and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Empirical data from simulated and real-world studies demonstrate the performance trade-offs between model types. The following table synthesizes findings from metabolic engineering and systems biology applications.

Table 2: Empirical Performance Comparison of Model Types

| Model Application / Type | Reported Accuracy | Computational Improvement | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting / Random Forest (in low-data metabolic engineering) [16] | Outperformed other ML methods in low-data regime | Not specified (low prediction time) | Robust to training set biases and experimental noise [16] |

| LSTM Surrogate for SDE model of MYC/E2F pathway [17] | R²: 0.925 - 0.998 | Not specified | Effectively captured dynamics of a 10-equation SDE system [17] |

| LSTM Surrogate for pattern formation in E. coli [17] | R²: 0.987 - 0.99 | 30,000x acceleration | Enabled rapid simulation of complex spatial dynamics [17] |

| Feedforward Neural Network Surrogate for artery stress analysis [17] | Test Error: 9.86% | Not specified | Provided fast approximations for complex PDE-based systems [17] |

| XGBoost Surrogate for left ventricle model [17] | MAE for volume: 1.495, for pressure: 1.544 | 100 - 1,000x acceleration | Accurate and fast emulation of a biomechanical system [17] |

| Gaussian Process Surrogate for human left ventricle [17] | MSE: 0.0001 | 1,000x acceleration | High-fidelity approximation with uncertainty quantification [17] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and validation of these models rely on a suite of computational tools and data resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Model Development and Validation

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SKiMpy [16] | Software Package | Symbolic kinetic models in Python; used for building and simulating mechanistic metabolic models [16]. |

| Veeva Vault CDMS [18] | Data Management System | Combines Electronic Data Capture (EDC) with data management and analytics; ensures data integrity for model training [18]. |

| SAS (Statistical Analysis System) [18] | Statistical Software | A powerful suite used for advanced analytics, data management validation, and decision support in clinical trials and data analysis [18]. |

| R Programming Language [18] | Statistical Software | Environment for statistical computing and graphics; enables complex data manipulations, validation, and trend analysis [18]. |

| dbt (data build tool) [19] | Data Transformation Tool | Used to implement core data quality checks (uniqueness, non-nullness, freshness) via version-controlled YAML files, ensuring reliable input data [19]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol for Benchmarking ML Models in Metabolic Engineering

This protocol, derived from a framework for consistently testing ML methods over multiple DBTL cycles, allows for a fair comparison of different algorithms [16].

- Define the Pathway and Objective: Integrate a synthetic pathway into a representative host model (e.g., an E. coli core kinetic model). The objective is typically to maximize the flux toward a product of interest [16].

- Generate Training Data: Use the kinetic model to simulate a large library of strain designs by varying enzyme concentrations (e.g., by changing

Vmaxparameters). This creates a combinatorial library of input (enzyme levels) and output (product flux) pairs [16]. - Create Iterative DBTL Cycles: Split the simulated data into multiple sequential DBTL cycles. An initial set of designs is used for the first cycle. The ML model's role is to learn from the accumulated data in each cycle and recommend the next set of promising designs to "build" and "test" (simulate) [16].

- Train and Compare ML Models: In each cycle, train multiple ML models (e.g., gradient boosting, random forest, neural networks) on all data collected so far.

- Evaluate Performance: The key metric is the model's success in recommending designs that lead to high product flux over successive cycles. This tests the model's ability to learn and guide the optimization process efficiently. The framework can also test robustness to training set biases and experimental noise [16].

Protocol for Building and Validating an ML Surrogate Model

This methodology outlines the general process for creating a machine learning surrogate for a complex mechanistic model [17].

- Define Scope and Input/Output: Decide which outputs of the mechanistic model need to be predicted and which input parameters or initial conditions will be varied.

- Generate Training Dataset: Run the mechanistic model multiple times with the chosen inputs varied across their expected ranges. This creates a dataset of input-output pairs for training the surrogate. A large number of simulations may be required.

- Split Data and Train Surrogate: Split the generated data into training (80-90%) and testing (10-20%) sets. Train the selected ML algorithm (e.g., LSTM, Gaussian Process, XGBoost) on the training set.

- Validate Surrogate Accuracy: Use the held-out test set to validate the surrogate. Common metrics include R², Mean Absolute Error (MAE), or Mean Squared Error (MSE). The surrogate's predictions are also compared against the mechanistic model's outputs for new input values not in the training set.

- Deploy for Analysis: Once validated, the surrogate model can be used for tasks that were previously infeasible with the slow mechanistic model, such as large-scale parameter sweeps, sensitivity analysis, or uncertainty quantification [17].

Data Validation and Quality Assurance

For models to be reliable, the data fueling them must be trustworthy. Robust data validation processes are critical, especially when integrating high-throughput experimental data.

Table 4: Essential Data Quality Checks for DBTL Analytics

| Check Type | Description | Example in DBTL Context |

|---|---|---|

| Uniqueness [19] | Ensures all values in a column are unique. | Checking that strain identifiers or primary keys in a screening results table are not duplicated. |

| Non-Nullness [19] | Verifies that critical columns contain no null/missing values. | Ensuring that measured product titer, yield, or rate (TYR) values are always recorded. |

| Accepted Values [19] | Confirms that data falls within a predefined set of valid values. | Verifying that "promoter strength" is labeled as 'weak', 'medium', or 'strong' and nothing else. |

| Freshness [19] | Monitors that data is up-to-date and pipelines are stable. | Tracking that high-throughput screening data is loaded into the analysis database without significant delays. |

| Referential Integrity [19] | Checks that relationships between tables are consistent. | Ensuring that a strain ID in a results table has a corresponding entry in a master strain library table. |

The choice between mechanistic, machine learning, and hybrid surrogate models in simulated DBTL cycles is not a matter of selecting a single superior option. Each model type occupies a distinct and complementary niche. Mechanistic models provide an irreplaceable foundation for understanding fundamental biology and generating high-quality synthetic data for training ML models. Pure machine learning models excel at rapidly identifying complex, non-intuitive patterns from large datasets to guide design choices. Surrogate ML models powerfully combine these strengths, making detailed mechanistic understanding practically usable for rapid iteration and exploration.

The future of optimization in metabolic engineering and drug discovery lies in the intelligent integration of these approaches. Leveraging mechanistic models for their explanatory power and using ML—particularly surrogates—for their speed and pattern recognition capabilities creates a powerful, synergistic toolkit. This allows researchers to navigate the vast design space of biological systems more efficiently than ever before, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics and bio-based products.

State-Space Representations, Cached Data, and Model Fidelity

In computational research, particularly in drug development, the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle provides a framework for iterative model refinement. A critical challenge within this cycle is ensuring that the models used for simulation and prediction are faithful representations of the underlying biological systems. The concepts of state-space representations, cached data, and model fidelity are interlinked pillars supporting robust model validation. State-space models (SSMs) offer a powerful mathematical framework for describing the dynamics of a system, while cached data—often in the form of pre-computed synthetic datasets—accelerates the "Build" and "Test" phases. Ultimately, the utility of this entire pipeline hinges on model fidelity, the accuracy with which a model captures the true system's behavior, which must be rigorously assessed against biologically relevant benchmarks before informing high-stakes decisions in the drug development process.

Theoretical Foundations: State-Space Models and Cached Synthetic Data

State-Space Representations in Computational Science

State-space representations are a foundational formalism for modeling dynamic systems. They describe a system using two core equations:

- A state equation that defines the evolution of the system's internal (latent) states over time.

- An observation equation that defines how these internal states are mapped to measurable outputs.

In the context of systems biology and neuroscience, a primary goal is to discover how ensembles of neurons or cellular systems transform inputs into goal-directed outputs, a process known as neural computation. The state-space, or dynamical systems, framework is a powerful language for this, as it connects observed neural or cellular activity with the underlying computation [20]. Formally, this involves learning a latent dynamical system ( \dot{z} = f(z, u) ) and an output projection ( x = h(z) ) whose time-evolution approximates the desired input/output mapping [20]. Modern deep state-space models (SSMs) have revived this classical approach, overcoming limitations of models like RNNs and transformers by incorporating strong inductive biases for continuous-time data, enabling efficient training and linear-time inference [21].

The Role and Generation of High-Fidelity Cached Data

Cached data, particularly synthetic data, is artificially generated data that mimics real-world datasets. It is crucial for the "Build" and "Test" phases of the DBTL cycle, especially when real data is scarce, privacy-sensitive, or expensive to collect. The caching of such data allows researchers to rapidly prototype, train, and validate models without constantly regenerating datasets from scratch.

Traditional approaches to generating cached synthetic data have included:

- Simulation-based approaches using 3D rendering engines, which are scalable but require complex scene setup and are often limited to generic object categories [22].

- GAN-based methods, which can produce realistic images but often struggle with spatial consistency and require computationally intensive, task-specific training [22].

- Copy-paste techniques, which are simple but can result in unrealistic object placements and poor integration with background features [22].

A frontier approach involves diffusion-based models, which achieve high visual quality. However, they can struggle with precise spatial control. A more flexible method involves leveraging a 3D representation of an object (e.g., via 3D Gaussian Splatting) to preserve its geometric features, and then using generative models to place this object into diverse, high-quality background scenes [22]. This enhances fidelity and adaptability without the need for heavy retraining.

A critical consideration when using cached synthetic data is the fidelity-utility-privacy trade-off. A novel "fidelity-agnostic" approach prioritizes the utility of the data for a specific prediction task over its direct resemblance to the original dataset. This can simultaneously enhance the predictive performance of models trained on the synthetic data and strengthen privacy protection [23].

Comparative Analysis: State-Space Models and Alternative Architectures

Evaluating model architectures requires standardized benchmarks and metrics. The Computation-through-Dynamics Benchmark (CtDB) is an example of a platform designed to fill the critical gap in validating data-driven dynamics models [20]. It provides synthetic datasets that reflect the computational properties of biological neural circuits, along with interpretable metrics for quantifying model performance.

Table 1: Comparative performance of state-space models and other architectures on temporal modeling tasks.

| Model Architecture | Theoretical Complexity | Key Strength | Key Limitation | Exemplar Performance (S2P2 model on MTPP tasks [21]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-Space Models (SSMs) | Linear | Native handling of continuous-time, irregularly sampled data; strong performance on long sequences. | Can be less intuitive to design and train than discrete models. | 33% average improvement in predictive likelihood over best existing approaches across 8 real-world datasets. |

| Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) | Sequential | Established architecture for sequence modeling. | Struggles with long-term dependencies; no inherent continuous-time bias. | Outperformed by modern SSMs on continuous-time event sequences [21]. |

| Transformers | Quadratic (in sequence length) | Powerful context modeling with self-attention mechanisms. | High computational cost for long sequences; discrete-time operation. | SSM-based 3D detection paradigm (DEST) showed +5.3 AP50 improvement over transformer-based baseline on ScanNet V2 [24]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

A robust DBTL cycle requires standardized experimental protocols to ensure that performance comparisons are meaningful and that model fidelity is accurately assessed.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking against the Computation-through-Dynamics Benchmark (CtDB)

The CtDB framework provides a methodology for evaluating a model's ability to infer underlying dynamics from observed data [20].

- Dataset Selection: Choose one or more synthetic datasets from the CtDB library. These datasets are generated by "task-trained" (TT) models to reflect goal-directed, input-output transformations, making them better proxies for biological neural circuits than non-computational chaotic attractors [20].

- Model Training: Train the data-driven (DD) model (e.g., an SSM) to reconstruct the observed neural activity from the chosen dataset.

- Performance Quantification: Evaluate the model using CtDB's multi-faceted metrics, which go beyond simple reconstruction accuracy. These are designed to be sensitive to specific failure modes in dynamics inference [20]:

- Dynamics Prediction: Assess the model's ability to predict future system states.

- Fixed Point Analysis: Compare the attractor structures of the inferred dynamics against the ground truth.

- Input-Driven Response: Evaluate how well the model's dynamics respond to external inputs.

- Interpretation: Use the results to guide model development, tuning, and troubleshooting. A high-fidelity model should perform well across all metrics, indicating that its inferred dynamics (( \hat{f} )) closely match the ground-truth dynamics (( f )) [20].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this validation protocol:

Protocol 2: Validating Marked Temporal Point Process Models

This protocol is tailored for evaluating models on sequences of irregularly-timed events, which are common in healthcare (e.g., patient admissions) and drug development.

- Data Preparation: Split multiple real-world datasets of marked event sequences (e.g., MIMIC-IV for healthcare) into training, validation, and test sets, preserving the temporal order of events.

- Model Training and Comparison: Train the target SSM (e.g., the State-Space Point Process (S2P2) model) and a suite of baseline models (e.g., Transformer-based models, RNNs, classical Hawkes processes) on the training data. The S2P2 model uses an architecture that interleaves stochastic jump differential equations with non-linearities to create a highly expressive intensity-based model [21].

- Evaluation: Use the predictive log-likelihood on the held-out test set as the primary metric to evaluate the model's performance. This measures how well the model's predicted distribution of future events matches the ground truth.

- Efficiency Analysis: Benchmark the computational cost and scaling behavior of the models, for instance, by confirming that the SSM achieves linear time complexity via a parallel scan algorithm [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

For researchers embarking on model development and validation within the DBTL cycle, the following tools and resources are essential.

Table 2: Key research reagents and resources for model development and validation.

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CtDB Benchmark [20] | Software/Data | Provides biologically-inspired synthetic datasets and standardized metrics for objectively evaluating the fidelity of data-driven dynamics models. |

| S2P2 Model [21] | Software/Model Architecture | A state-space point process model for marked event sequences; serves as a state-of-the-art baseline for temporal modeling tasks in healthcare and finance. |

| 3D Gaussian Splatting [22] | Algorithm | A 3D reconstruction technique used in synthetic data generation pipelines to create high-fidelity, controllable 3D representations of unique objects for training detection models. |

| Fidelity-agnostic Synthetic Data [23] | Methodology | A data generation approach that prioritizes utility for a specific prediction task over direct resemblance to real data, enhancing performance and privacy. |

| DEST (Interactive State Space Model) [24] | Software/Model Architecture | A 3D object detection paradigm that models queries as system states and scene points as inputs, enabling simultaneous feature updates with linear complexity. |

The integration of high-fidelity state-space representations with rigorously generated cached data is paramount for advancing simulated DBTL cycles in computationally intensive fields like drug development. As the comparative data and experimental protocols outlined here demonstrate, state-space models offer distinct advantages in modeling complex, continuous-time biological processes. The critical reliance on synthetic cached data for training and validation further underscores the need for community-wide benchmarks like CtDB to ensure model fidelity is measured against biologically meaningful standards. The continued development and objective comparison of these computational tools, grounded in robust validation protocols, will be essential for accelerating the pace of scientific discovery and therapeutic innovation.

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Approaches and Cross-Domain Applications

In the field of synthetic biology, simulated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles have emerged as a powerful computational approach to accelerate biological engineering, particularly for metabolic pathway optimization. These simulations leverage mechanistic models and machine learning to predict strain performance before resource-intensive laboratory work, guiding researchers toward optimal designs more efficiently. This guide compares the performance and methodologies of two predominant frameworks for implementing simulated DBTL cycles: the Mechanistic Kinetic Model-based Framework and the Machine Learning Automated Recommendation Tool (ART).

The DBTL cycle is a cornerstone of synthetic biology, providing a systematic framework for bioengineering [25]. However, traditional DBTL cycles conducted entirely in the laboratory can be time-consuming, costly, and prone to "involution," where iterative trial-and-error leads to endless cycles without significant productivity gains [26]. Simulated DBTL cycles address this challenge by using in silico models to explore the design space and recommend the most promising strains for physical construction [16] [27].

A primary application is combinatorial pathway optimization, where simultaneous modification of multiple pathway genes often leads to a combinatorial explosion of possible designs [16]. Strain optimization is therefore performed iteratively, with each DBTL cycle incorporating learning from the previous one [16]. The core challenge these simulations address is the lack of a consistent framework for testing the performance of methods like machine learning over multiple DBTL cycles [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The implementation of simulated DBTL cycles relies on sophisticated experimental and computational protocols. Below, we detail the methodologies for the two main approaches.

Protocol 1: Mechanistic Kinetic Model-Based Framework

This protocol uses kinetic models to simulate cellular metabolism and generate training data for machine learning models [16].

- Kinetic Model Representation: A synthetic pathway is integrated into a host organism's core kinetic model, such as the established Escherichia coli core model implemented in the SKiMpy package [16]. This model uses ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to describe changes in intracellular metabolite concentrations over time.

- Bioprocess Embedding: The cell model is embedded within a basic bioprocess model, such as a 1 L batch reactor, to simulate realistic fermentation conditions including biomass growth and substrate consumption [16].

- In-silico Strain Design: Enzyme expression levels are varied in silico by changing the Vmax parameters in the kinetic model. This simulates the effect of using different genetic parts (e.g., promoters, RBS) from a predefined DNA library [16].

- Data Generation for ML: The model simulates the production outcome (e.g., titer, yield, rate) for a wide array of combinatorial strain designs. The input (enzyme levels) and output (production level) data are recorded to form a comprehensive dataset for machine learning [16].

- Machine Learning Model Training: The generated dataset is used to train ML models (e.g., Gradient Boosting, Random Forest) to predict production based on enzyme levels [16].

- Recommendation and Validation: A recommendation algorithm uses the trained ML model's predictions to propose new, high-performing strain designs for the next DBTL cycle. The framework allows for testing different DBTL strategies, such as varying the number of strains built per cycle [16].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Automated Recommendation Tool (ART)

ART is a general-purpose tool that leverages machine learning and probabilistic modeling to guide DBTL cycles, even with limited data [28].

- Data Collection and Import: Data from previous DBTL cycles is collected. ART can import this data directly from online repositories like the Experiment Data Depot (EDD) or from EDD-style .csv files [28].

- Predictive Model Building: ART uses a Bayesian ensemble of machine learning models from the scikit-learn library to build a predictive function. This function maps input variables (e.g., proteomics data, promoter combinations) to a probability distribution of the output response (e.g., production level) [28].

- Uncertainty Quantification: A key feature of ART is its rigorous quantification of prediction uncertainty. This is crucial for guiding experiments toward the least-known parts of the design space and for assessing the reliability of recommendations [28].

- Strain Recommendation: Based on the predictive model, ART provides a set of recommended strains to build in the next cycle. It supports various metabolic engineering objectives, including maximization, minimization, or targeting a specific level of production [28].

- Experimental Validation and Cycle Iteration: The recommended strains are built and tested in the laboratory. The resulting new data is fed back into ART, and the cycle repeats, recursively improving the model with each iteration [28].

Performance Comparison of Simulation Frameworks

The table below summarizes a direct comparison of the two frameworks based on key performance indicators and application data.

- Performance Comparison of Simulated DBTL Frameworks

| Feature | Mechanistic Kinetic Model Framework | Machine Learning ART Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Mechanistic modeling of metabolism using ODEs [16] | Bayesian ensemble machine learning [28] |

| Primary Data Input | Enzyme concentration levels (Vmax parameters) [16] | Multi-omics data (e.g., targeted proteomics), promoter combinations [28] |

| Key Output | Prediction of metabolite flux and product concentration [16] | Probabilistic prediction of production titer/rate/yield [28] |

| Experimental Context | Simulated data for combinatorial pathway optimization [16] | Experimental data from metabolic engineering projects (e.g., biofuels, tryptophan) [28] |

| Recommended ML Models | Gradient Boosting, Random Forest (for low-data regimes) [16] | Ensemble of Scikit-learn models (adaptable to data size) [28] |

| Handles Experimental Noise | Robust to training set biases and experimental noise [16] | Designed for sparse, noisy data typical in biological experiments [28] |

| Key Advantage | Provides biological insight into pathway dynamics and bottlenecks [16] | Does not require full mechanistic understanding; quantifies prediction uncertainty [28] |

A study using the kinetic model framework demonstrated that Gradient Boosting and Random Forest models outperformed other methods, particularly in the low-data regime common in biological experiments [16]. The same study used simulated data to determine that an optimal DBTL strategy is to start with a large initial cycle when the total number of strains to be built is limited, rather than building the same number in every cycle [16].

In a parallel experimental study using ART to optimize tryptophan production in yeast, researchers achieved a 106% increase in productivity from the base strain [28]. ART has also been successfully applied to optimize media composition, leading to a 70% increase in titer and a 350% increase in process yield for flaviolin production in Pseudomonas putida [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successfully implementing simulated DBTL cycles requires a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details key resources.

- Research Reagent Solutions for Simulated DBTL Cycles

| Item Name | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|

| SKiMpy (Symbolic Kinetic Models in Python) | A Python package for building and simulating kinetic models of metabolism, used to generate initial training data [16]. |

| Scikit-learn | A core open-source machine learning library in Python; provides the algorithms for ART's ensemble model [28]. |

| Experiment Data Depot (EDD) | An online tool for standardized storage of experimental data and metadata, which ART can directly import from [28]. |

| Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) | A dedicated tool that combines machine learning with probabilistic modeling to recommend strains for the next DBTL cycle [28]. |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Library | A defined set of genetic parts with varying strengths; used to fine-tune enzyme expression levels in the "Build" phase [30]. |

| Biofoundry Automation Platform | An integrated facility of automated equipment (liquid handlers, incubators) that executes the "Build" and "Test" phases at high throughput [31]. |

Workflow Visualization and Logical Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical structures of the two main simulated DBTL workflows.

Simulated DBTL with Kinetic Models

Machine Learning-Driven DBTL with ART

Simulated DBTL cycles represent a paradigm shift in synthetic biology, moving away from purely trial-and-error approaches toward a more predictive and efficient engineering discipline. The Mechanistic Kinetic Model-based Framework excels in scenarios where deep biological insight into pathway dynamics is required, providing a transparent, hypothesis-driven approach. In contrast, the Machine Learning ART Framework offers a powerful, flexible solution that can deliver robust recommendations even without a complete mechanistic understanding, making it highly adaptable to diverse bioengineering challenges.

The future of simulated DBTL cycles lies in the integration of mechanistic models with machine learning [26]. This hybrid approach can overcome the "black box" nature of pure ML by offering both correlation and causation information, potentially resolving the involution state in complex strain development projects [26]. As these tools mature and biofoundries become more standardized [31], the ability to design biological systems predictively will fundamentally accelerate the development of novel drugs, sustainable chemicals, and advanced materials.

Leveraging Established Software and Platforms (e.g., OpenSim)

In the context of computational biology and biomedical research, the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle provides a rigorous framework for iterative model development and validation. Within this paradigm, established simulation platforms like OpenSim serve as critical infrastructure for the "Test" phase, enabling researchers to computationally validate musculoskeletal models against experimental data before proceeding to physical implementation or clinical application. This guide objectively compares OpenSim's performance and capabilities against other modeling approaches, focusing on its role in generating predictive simulations of human movement. Unlike general-purpose platforms like MATLAB Simulink, OpenSim offers built-in, peer-reviewed capabilities for inverse dynamics, forward dynamics, and muscle-actuated simulations, eliminating the need for custom programming for common biomechanical analyses and enhancing reliability and reproducibility [32]. This specialized focus makes it particularly valuable for research requiring patient-specific modeling and the investigation of internal biomechanical parameters impossible to measure in vivo.

Platform Comparison: OpenSim Versus Alternative Approaches

Selecting the appropriate simulation platform is crucial for the efficiency and validity of DBTL cycles. The table below provides a structured comparison of OpenSim against other common approaches in biomechanical research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biomechanical Simulation Platforms

| Platform/Approach | Primary Use Case | Key Strengths | Typical Sample Size in Studies [32] | Validation Data Utilized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenSim | Musculoskeletal dynamics & movement simulation | - Open-source, community-driven development- Built-in tools (IK, ID, CMC)- Extensive model repository [32] | 0 - 40 participants (Shoulder studies) | Motion capture, force plates, EMG, medical imaging [33] [34] |

| Custom MATLAB/Python Scripts | Specific, tailored biomechanical analyses | - High customization- Direct control over algorithms | Varies widely | Researcher-defined (often force plates, motion capture) |

| Commercial Software (e.g., AnyBody, LifeMod) | Industrial & clinical biomechanics | - Polished user interface- Commercial support | Often proprietary or smaller samples | Motion capture, force plates |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | Joint contact mechanics & tissue stress/strain | - High-fidelity stress analysis- Detailed material properties | Often cadaveric or generic models | Medical imaging (CT, MRI) |

The comparative advantage of OpenSim is evident in its integrated workflow, which is specifically designed for dynamic simulations of movement. A scoping review of OpenSim applications in shoulder modeling found that its built-in analysis tools, particularly Inverse Kinematics (IK) and Inverse Dynamics (ID), are the most commonly employed in research, enabling the calculation of joint angles and net joint loads from experimental data [32]. Furthermore, its open-source nature and extensive repository of shared models and data on SimTK.org facilitate reproducibility and collaborative refinement—key aspects of the "Learn" phase in DBTL cycles. For instance, researchers can access and build upon shared datasets that include motion capture, ground reaction forces, and even muscle fascicle length data [35] [34].

Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarking

Quantitative validation is the cornerstone of model credibility in the DBTL framework. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from published studies that utilized OpenSim, demonstrating its application in generating and validating simulations against experimental data.

Table 2: Experimental Data and Performance Metrics in OpenSim Studies

| Study / Model | Experimental Data Used for Validation | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result / Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle-Driven Cycling Simulations [35] | Motion capture, external forces, EMG from 16 participants | Reduction in tibiofemoral joint reaction forces | Minimizing joint forces in the objective function improved similarity to experimental EMG timing and better matched in vivo measurements. |

| Model Scaling (Best Practices) [36] | Static pose marker data | Marker Error | Maximum marker errors for bony landmarks should be < 2 cm; RMS error should typically be < 1 cm. |

| Inverse Kinematics (Best Practices) [36] | Motion capture marker trajectories | Marker Error | Maximum marker error should generally be < 2-4 cm; RMS under 2 cm is achievable. |

| MSK Model Validation Dataset [34] | Fascicle length (soleus, lateral gastrocnemius, vastus lateralis) and EMG data | Model-predicted vs. measured muscle mechanics | Dataset provided for validating muscle mechanics and energetics during diverse hopping tasks. |

The cycling simulation study exemplifies a sophisticated DBTL approach, where the model was not just fitted to kinematics but also validated against independent electromyography (EMG) data [35]. This multi-modal validation strengthens the model's predictive power for internal loading, a variable that cannot be directly measured non-invasively in vivo. Similarly, the published best practices for OpenSim provide clear, quantitative targets for model scaling and inverse kinematics, establishing benchmarks for researchers to "Test" the quality of their models during the DBTL cycle [36].

Workflow for Model Validation and Simulation

The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for creating and validating a simulation in OpenSim, which aligns with the "Build," "Test," and "Learn" phases of a DBTL cycle.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Model Validation