Troubleshooting Synthetic Gene Circuits: Strategies for Stable Expression and Enhanced Reliability in Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the persistent challenges of synthetic gene circuit expression and stability.

Troubleshooting Synthetic Gene Circuits: Strategies for Stable Expression and Enhanced Reliability in Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the persistent challenges of synthetic gene circuit expression and stability. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explores the root causes of circuit failure, including metabolic burden, evolutionary instability, and host-circuit interactions. The content details innovative troubleshooting methodologies such as feedback controllers, memory circuits, and phase-separation techniques, alongside validation frameworks for assessing circuit longevity and performance. By synthesizing recent advances and comparative analyses of design strategies, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to build more robust and reliable genetic systems for therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Understanding the Core Challenges: Why Synthetic Gene Circuits Fail

Metabolic Burden: Core Concepts and Definitions

What is metabolic burden in the context of synthetic gene circuits? Metabolic burden is the fitness cost imposed on a host cell by the expression of synthetic gene circuits. This occurs because the circuit actively consumes significant cellular resources—such as nucleotides, amino acids, energy (ATP), and enzymatic machinery—that the host cell creates for its own physiological functions, including growth and survival [1]. This resource competition can lead to reduced host growth rates and compromised circuit function.

What are the primary cellular resources that synthetic gene circuits consume? Synthetic gene circuits primarily consume the host's gene expression resources. This includes key components like [2]:

- Ribosomes (R): Essential for translating mRNA into protein.

- RNA polymerases: Required for transcribing DNA into mRNA.

- Energy (e): Cellular energy in the form of ATP and other anabolites needed to power transcription and translation.

- Amino acids and nucleotides: The fundamental building blocks for synthesizing proteins and nucleic acids.

How does metabolic burden ultimately lead to circuit failure? Burden creates a selective pressure that favors non-functional circuit mutants. Cells expressing the functional circuit experience a growth disadvantage because resources are diverted from their own essential processes [2]. Over time, faster-growing mutant cells that have acquired mutations disrupting circuit function (e.g., in promoters or coding sequences) will outcompete the original engineered cells. This evolutionary process eventually eliminates functional circuit from the population [2].

Diagnostic Guide: Identifying Metabolic Burden in Your Experiments

What are the key experimental indicators of high metabolic burden? The table below summarizes the primary quantitative and qualitative indicators of metabolic burden.

| Indicator | Description & Measurement | Typical Thresholds / Observations |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Growth Rate | Slower cell division and prolonged culture doubling time compared to unengineered controls [2]. | Measured by optical density (OD) over time. A significant reduction (e.g., >20%) is a strong indicator. |

| Decreased Final Biomass | Lower saturation density in batch culture conditions [2]. | Measured as maximum OD. A lower yield suggests resources were diverted from biomass production. |

| Loss of Circuit Function Over Time | Decline in the population-level output of the circuit during prolonged culture (e.g., serial passaging) [2]. | Quantified by fluorescence (for reporters) or functional assays. A 50% reduction in output (τ50) is a common metric for failure [2]. |

| Increased Population Heterogeneity | Growing variability in circuit output between individual cells in a population [3]. | Observed via flow cytometry or microscopy; a wider distribution of expression levels suggests unstable control. |

How can I distinguish between metabolic burden and toxicity from my expressed protein? While both can reduce growth, they have distinct characteristics:

- Metabolic Burden: The negative effect on growth is proportional to the total level of synthetic gene expression, even for non-toxic proteins like GFP. Reducing expression levels (e.g., with a weaker promoter) should alleviate the growth defect [2].

- Protein Toxicity: The negative effect is specific to the function or misfolding of the protein itself. Growth defects will persist even at low expression levels if the protein is inherently toxic.

What modeling approaches can predict burden before experimental testing? "Host-aware" computational frameworks use ordinary differential equations to model host-circuit interactions. These models simulate the consumption of shared cellular resources (ribosomes, energy) by the circuit, dynamically coupling it to the host's growth rate. This allows for in silico prediction of burden and the evolutionary trajectory of the circuit population [2].

Mitigation Strategies: A Troubleshooting FAQ

What are the most effective design principles to minimize metabolic burden? The table below outlines key strategies supported by recent research.

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Implement Orthogonal Systems | Using genetic parts (e.g., bacterial transcription factors, phage recombinases) that interact weakly with the host's native networks [4]. | Reduces unintended cross-talk and interference with essential host processes [4]. |

| Employ Negative Feedback Control | The circuit's output protein regulates its own production, dampening overexpression and reducing resource consumption [2]. | Can extend the functional half-life (τ50) of the circuit. Post-transcriptional controllers (e.g., using sRNAs) can outperform transcriptional ones [2]. |

| Use Tunable Expression Systems | Systems like the DIAL (Distance-Induced Actuation of Levels) platform allow post-hoc adjustment of gene expression to find an optimal level that balances function and burden [3]. | Enables finding a "sweet spot" for gene expression that maintains function without over-burdening the host [3]. |

| Couple Circuit to Host Fitness | Artificially linking circuit function to an essential gene or survival mechanism [2]. | Makes mutations that disrupt the circuit also disadvantageous for survival, but can constrain circuit design [2]. |

How can I dynamically control expression to avoid burden? The DIAL system allows you to fine-tune expression after circuit delivery. It uses the distance between a promoter and gene—lengthened by a "spacer" sequence—to set a baseline expression level. Adding recombinase enzymes excises parts of the spacer, bringing the promoter closer and dialing expression up to predefined "high," "med," or "low" set points [3]. This enables real-time optimization to minimize burden while maintaining sufficient output.

My circuit function is still degrading rapidly. What advanced controllers can I use? For enhanced evolutionary longevity, consider multi-input controllers. These "host-aware" designs can use feedback based on both the circuit's output and the host's growth rate. Simulations show that growth-based feedback can extend the circuit's functional half-life more than threefold by directly countering the selective advantage of low-producing mutants [2].

Experimental Protocols for Burden Quantification

Protocol: Serial Passaging to Measure Circuit Longevity (Half-Life, τ50)

Objective: Quantify the evolutionary longevity of a synthetic gene circuit by measuring the time it takes for its population-level output to fall by 50% [2].

- Culture Inoculation: Start a batch culture of your engineered cells in a selective medium.

- Sampling and Dilution: Every 24 hours (or at your chosen interval), measure the culture's optical density (OD) and the circuit's output (e.g., fluorescence via flow cytometry). Dilute the culture into fresh medium to maintain continuous growth.

- Data Collection: Repeat Step 2 for at least 50-100 generations.

- Data Analysis:

Protocol: Measuring Single-Cell Burden with Flow Cytometry

Objective: Assess cell-to-cell heterogeneity and correlate circuit expression with growth markers at the single-cell level.

- Sample Preparation: Take samples from a growing culture of your circuit-bearing cells.

- Staining: Use a fluorescent dye (e.g., a membrane-permeable dye that binds nucleic acids) as a proxy for cellular biomass and growth rate.

- Flow Cytometry: Analyze the cells using a flow cytometer with appropriate lasers and filters to measure both the circuit reporter (e.g., GFP) and the growth marker dye simultaneously.

- Data Analysis: Create a scatter plot of circuit fluorescence versus growth marker fluorescence. A strong negative correlation indicates that high-expression cells have lower growth rates, directly demonstrating burden at the single-cell level.

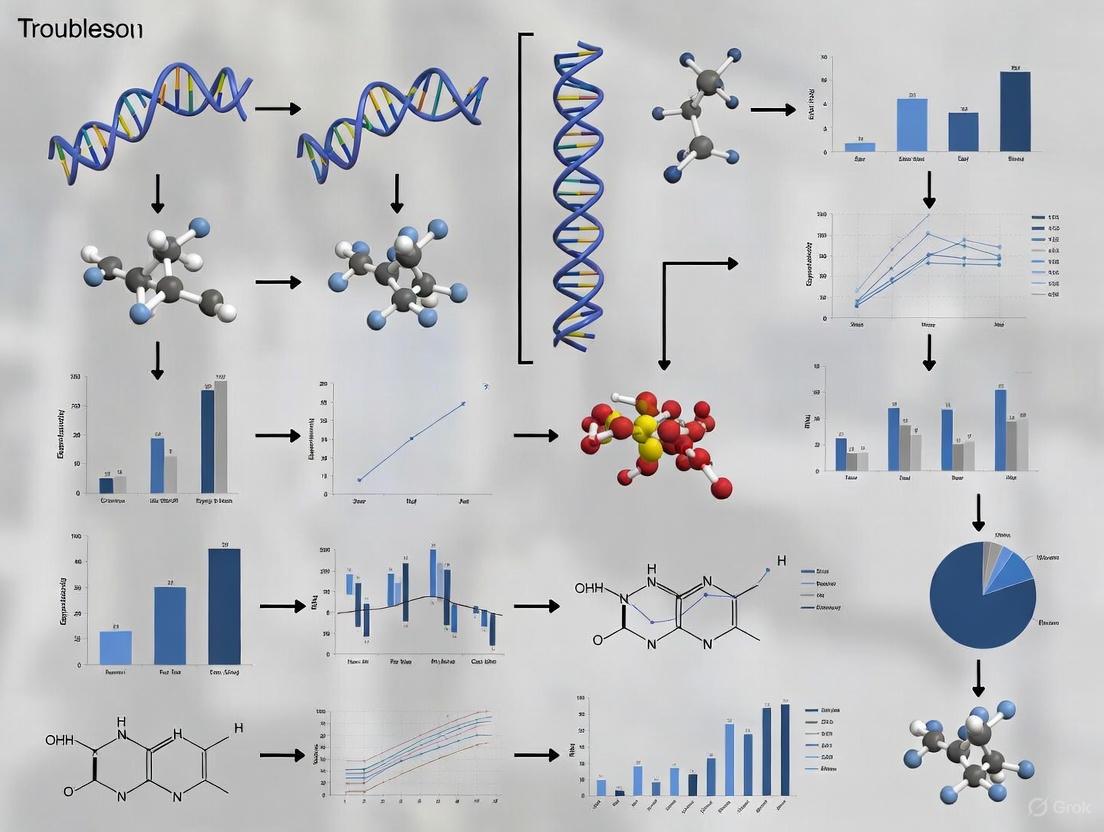

Essential Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors (e.g., bacterial TFs) | To build circuit integrators that minimize cross-talk with the host's native gene regulatory networks [4]. |

| Site-Specific Recombinases (e.g., Cre, from bacteriophage) | To implement permanent genetic memory or, as in the DIAL system, to tune expression levels by editing DNA spacer sequences [4] [3]. |

| CRISPR/Cas Components | To construct programmable synthetic gene circuits that can act as sensors, integrators, or actuators for endogenous genes without heavy reliance on host TFs [4]. |

| "Host-Aware" Modeling Software | A computational framework using ODEs to simulate host-circuit interactions, predict burden, and model population evolution before costly wet-lab experiments [2]. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems (e.g., Dexamethasone, β-Estradiol) | To provide precise temporal control over circuit activation, allowing researchers to separate growth phases from high-burden production phases [4]. |

| Small RNAs (sRNAs) | For post-transcriptional feedback control; can more effectively silence circuit mRNA and reduce burden compared to some transcriptional controllers [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Circuit Failures & Solutions

This guide addresses the most frequent issues researchers encounter with the evolutionary stability of synthetic gene circuits.

Problem 1: Rapid Loss of Circuit Function Within Generations

- Symptoms: Circuit output (e.g., fluorescence, metabolite production) declines significantly over a small number of bacterial generations, often less than 50.

- Underlying Cause: The synthetic circuit imposes a metabolic burden on the host cell, diverting resources like ribosomes and amino acids away from host growth. This reduces the host's growth rate, creating a strong selective pressure for mutants where the circuit has been inactivated by mutation. These faster-growing mutants then outcompete the functional cells in the population [2] [5].

- Solution:

- Reduce Genetic Instability: Avoid repeated genetic sequences (e.g., homologous transcriptional terminators, repeated operator sequences) in your circuit design, as these are hotspots for recombination and deletion events [5].

- Lower Expression Level: Decrease the constitutive expression level of circuit genes. High expression levels are strongly correlated with low evolutionary half-life [5].

- Implement Negative Feedback: Design circuits that use negative feedback control to dynamically regulate expression, which can reduce burden and prolong functional output [2].

Problem 2: Inconsistent Performance Across Cell Populations

- Symptoms: Heterogeneous gene expression within a clonal population, leading to unreliable circuit behavior.

- Underlying Cause: Natural variation in cellular resources and stochastic gene expression, often exacerbated by competition for limited transcriptional and translational machinery [6] [3].

- Solution:

- Use Orthogonal Parts: Employ genetic parts (e.g., bacterial transcription factors, CRISPR/Cas components) that interact minimally with the host's native systems to reduce cross-talk and improve predictability [4].

- Implement Uniform Expression Control: Utilize systems like the DIAL (Dialable Expression) platform, which allows post-hoc adjustment of a circuit's expression set point to achieve uniform protein levels across a cell population [3].

Problem 3: Circuit Function is Unstable Under Dynamic Growth Conditions

- Symptoms: Circuit behavior changes unpredictably as host cell growth rates vary, for example, between different growth phases or media.

- Underlying Cause: Growth-mediated dilution: as cells grow and divide, circuit components like transcription factors are diluted, which can destabilize circuit dynamics and lead to failure [7] [8].

- Solution:

- Leverage Transcriptional Condensates: Engineer circuits where transcription factors are fused to intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). These form droplet-like compartments via liquid-liquid phase separation, concentrating key components and buffering against dilution [8].

- Design for Growth-Feedback Robustness: Select circuit topologies that are known to maintain function, such as certain negative feedback loops or incoherent feed-forward loops, even when coupled with host growth [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key metrics for quantifying the evolutionary stability of my gene circuit?

Researchers typically use several metrics to measure evolutionary longevity [2]:

- P₀: The initial total circuit output of the ancestral population.

- τ₍±₁₀₎: The time (or number of generations) until the total population-wide output falls outside the range of P₀ ± 10%.

- τ₍₅₀₎ (Evolutionary Half-life): The time until the total population-wide output falls below 50% of P₀. This measures the "persistence" of circuit function.

Q2: My circuit needs high expression to be effective, but this makes it evolutionarily unstable. Are there design trade-offs?

Yes, this is a fundamental challenge. Quantitative studies show a direct trade-off: higher expression levels come at the cost of lower evolutionary stability [2] [5]. The table below summarizes experimental data showing how design choices impact evolutionary half-life.

Table 1: Impact of Circuit Design on Evolutionary Half-Life (Experimental Data)

| Circuit Design Feature | Impact on Evolutionary Half-life (τ₍₅₀₎) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| High Expression Level | Decreased | A 4-fold increase in expression can reduce evolutionary half-life more than 17-fold [5]. |

| Removal of Repeated Sequences (e.g., homologous terminators) | Increased | Eliminating sequence homology between terminators can more than double the circuit's half-life [5]. |

| Use of Inducible Promoters | Increased | Circuits with inducible promoters show greater stability than those with constitutive promoters [5]. |

| Negative Autoregulation | Increased (Short-term) | Prolongs the duration of stable output in the short term [2]. |

| Growth-Based Feedback | Increased (Long-term) | Extends the functional half-life (τ₍₅₀₎) of the circuit [2]. |

| Post-transcriptional Control (sRNA) | Outperforms Transcriptional Control | Generally provides stronger control with reduced controller burden, enhancing longevity [2]. |

Q3: Can a gene circuit that has lost its function ever regain it through evolution?

Under specific selective pressures, yes, lost circuit function can be regained, though not always through direct reversion of the original mutation. Research in yeast has shown that broken circuits can adapt to restoring a beneficial function (e.g., drug resistance) through extracircuit mutations in the host genome. These mutations can elevate basal expression levels of the broken circuit or otherwise compensate for the lost function, rather than repairing the circuit's original coding sequence [9].

Experimental Protocols for Stability Testing

Protocol 1: Serial Passaging for Measuring Evolutionary Half-life

This is a standard method for quantifying how long a circuit remains functional in a growing microbial population.

- Starting Culture: Inoculate a clonal population of engineered cells into fresh, selective liquid medium.

- Growth and Dilution: Allow the culture to grow for a set period (e.g., to stationary phase, or for a fixed number of generations). Each day, perform a serial transfer by diluting the culture into fresh medium. A typical dilution factor allows for approximately 6-10 new generations per day [5].

- Monitor Output: At regular intervals (e.g., every 24 hours or 20 generations), sample the population.

- Induce the circuit if it uses an inducible promoter.

- Measure the population-level output (e.g., fluorescence via flow cytometry or plate reader, production of a specific metabolite).

- Plate samples to obtain single colonies and check for function at the single-cell level.

- Data Analysis: Plot the normalized circuit output against time (or number of generations). The evolutionary half-life (τ₍₅₀₎) is the time it takes for the output to fall to 50% of its initial value [2] [5].

Protocol 2: Identifying Loss-of-Function Mutations

When a circuit fails, identifying the mutation is crucial for redesign.

- Isolate Non-Functional Clones: From the evolved population, pick single colonies that show no or low circuit output.

- Sequence the Circuit: Isolate the plasmid (or amplify the genomic region) containing the gene circuit from the non-functional clones. Use Sanger sequencing or whole-plasmid sequencing to identify mutations.

- Common Mutations to Check [5]:

- Deletions between repeated sequences (promoters, terminators).

- Point mutations in promoters, ribosome binding sites (RBS), or coding sequences.

- Insertion sequence (IS) element insertions, often in the scar sequences between BioBrick parts.

- Verify Causality: Clone the identified mutant circuit back into a fresh host cell to confirm that the mutation alone causes the loss of function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Engineering Evolutionary Robustness

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Circuit Design | Application in Stability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors (e.g., bacterial TFs in plants) [4] | Provides regulation that minimizes cross-talk with the host's native networks. | Reduces unintended interactions, making circuit performance more predictable and less likely to disrupt host fitness. |

| Small RNAs (sRNAs) [2] | Enables post-transcriptional regulation of circuit genes. | Generally outperforms transcriptional regulation in feedback controllers, offering strong control with lower burden. |

| Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) [8] | Fused to transcription factors to drive liquid-liquid phase separation. | Forms transcriptional condensates that buffer against growth-mediated dilution, stabilizing circuit memory and function. |

| Cre Recombinase (in DIAL system) [3] | Edits DNA spacer length between a promoter and gene. | Allows post-hoc fine-tuning of a circuit's expression set point in delivered cells for uniform, stable performance. |

| Serine Integrases/Recombinases (e.g., PhiC31, Bxb1, Flp) [10] | Catalyzes irreversible DNA recombination to create memory circuits. | Used to build logic gates and record past cellular events, though the logic is typically irreversible. |

| Host-Aware Computational Models [2] [7] | Multi-scale frameworks simulating host-circuit interactions, mutation, and competition. | Predicts evolutionary longevity in silico and evaluates controller architectures before costly experimental implementation. |

Visualizing Key Concepts and Workflows

Circuit Loss via Mutation & Selection

Burden-Feedback Loop

Core Concepts: Understanding Host-Circuit Interactions

What are host-circuit interactions? Synthetic gene circuits are not isolated entities; they function within a living cell and must utilize the host's native gene expression resources, such as ribosomes, amino acids, and RNA polymerases [2]. This sharing of resources creates an inherent interaction between the circuit and the host. The consumption of these cellular resources by the synthetic circuit disrupts the cell's natural homeostasis, a phenomenon often termed "metabolic burden" [4]. This burden frequently manifests as a reduction in cellular growth rate [2].

Why do these interactions cause problems? In microbes, growth rate is directly analogous to fitness. Therefore, a cell carrying a burdensome synthetic circuit is at a selective disadvantage compared to its unengineered or less-burdened counterparts [2]. During cell division, mutations can occur in the synthetic circuit. Mutations that reduce circuit function and, consequently, its resource consumption, provide a growth advantage to those cells. These "cheater" mutants can outcompete the original engineered cells, leading to the rapid evolutionary loss of circuit function in the population [2]. This is a primary reason why engineered circuits often lose functionality over time.

What is orthogonality and why is it important? Orthogonality is a fundamental design principle in synthetic biology. It refers to the use of genetic parts that interact strongly with each other but have minimal interaction with the host's natural cellular components [4]. This is often achieved by using parts derived from other organisms, such as bacterial transcription factors, phage-derived recombinases, or the CRISPR/Cas system [4]. Designing for orthogonality helps minimize unwanted cross-talk and reduces the metabolic burden on the host, thereby improving circuit stability and predictability [4].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

FAQ: My gene circuit's performance is declining rapidly over multiple cell generations. What is happening? This is a classic symptom of evolutionary instability. Your circuit is likely imposing a significant metabolic burden, creating a strong selection pressure for "cheater" mutants that have inactivating mutations in the circuit. These faster-growing mutants take over the population, causing a drop in the overall population-level output [2].

- Solution Strategies:

- Reduce Burden: Lower the expression level of your circuit components to the minimum required for function.

- Implement Genetic Controllers: Use feedback control systems that can sense and regulate circuit output or host growth to disincentivize the emergence of loss-of-function mutants [2].

- Couple to Essential Genes: Artificially link the function of your circuit to an essential gene required for host survival [2].

FAQ: The expression of my circuit is highly variable between cells, even in a clonal population. How can I fix this? Cell-to-cell variability (noise) can be caused by resource competition, stochastic binding of transcription factors, or mutations that alter the feedback dynamics of the circuit [11].

- Solution Strategies:

- Use Orthogonal Parts: Implement transcription factors and promoters from other species to avoid competition with host regulatory networks [4].

- Implement Feedback Loops: Negative feedback loops can suppress variation and stabilize expression levels [2].

- Stabilize with Transcriptional Condensates: Recent research shows that fusing transcription factors to intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) can form condensates via liquid-liquid phase separation. These condensates concentrate circuit components, buffering against dilution and potentially stabilizing expression [8].

FAQ: My circuit works perfectly in one host strain but fails in another. Why? Different host strains can have varying genetic backgrounds, resource pools, and expression capacities. Your circuit may be interacting differently with these distinct cellular contexts.

- Solution Strategies:

- Characterize Parts in New Hosts: Always re-characterize your genetic parts (promoters, RBSs) in the specific host strain you plan to use.

- Host-Aware Modeling: Use computational models that account for host-circuit interactions, such as resource sharing and growth feedback, to predict circuit behavior in a new strain before experimental testing [2].

- Consider "Mid-Scale Evolution": If possible, subject your circuit to directed evolution in the new host strain under a relevant selection pressure to optimize its function in that specific context [11].

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis & Mitigation

The table below outlines key experimental approaches for diagnosing and mitigating issues related to host-circuit interactions.

Table 1: Diagnostic and Mitigation Protocols for Host-Circuit Interactions

| Protocol Goal | Key Experimental Steps | Key Measurements & Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Quantifying Evolutionary Longevity [2] | 1. Serial passaging of engineered population in batch culture.2. Regular sampling and measurement of population-level output (e.g., fluorescence).3. Genomic analysis of sampled populations to identify mutations. | - P₀: Initial output.- τ±10: Time until output deviates by >10% from P₀.- τ₅₀: Time until output falls below 50% of P₀. |

| Implementing Growth-Based Feedback [2] | 1. Design a controller that senses host growth rate or a proxy.2. Construct a circuit where this controller actuates repression of the synthetic gene (e.g., via sRNAs).3. Integrate the controller circuit and test in serial passaging experiments. | - Comparison of τ₅₀ and τ±10 between open-loop and closed-loop (controlled) circuits.- Measurement of reduced burden (improved growth rate) in functional state. |

| Stabilizing Circuits via Phase Separation [8] | 1. Fuse transcription factors (TFs) in your circuit to Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs).2. Introduce fusion proteins into cells and confirm formation of transcriptional condensates via microscopy.3. Measure the stability of circuit output over time with and without IDR fusions. | - Visualization of condensates as bright, fluorescent foci.- Enhanced production yield in bioproduction pathways.- Increased resilience of circuit memory under dynamic growth. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Troubleshooting Host-Circuit Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Regulators | Bacterial TFs (e.g., TetR, LacI), CRISPR/Cas systems, Phage recombinases (e.g., Cre, Flp) [4] | Reduces cross-talk with host networks and decreases metabolic burden by using independent cellular machinery. |

| Inducible Promoters | Dexamethasone-, β-Estradiol-, Copper-, or Ethanol-responsive promoters [4] | Allows external control of circuit timing and expression level, enabling burden management and dynamic experiments. |

| Genetic Controllers | Negative autoregulation circuits, Growth-rate feedback controllers (using sRNAs for post-transcriptional control) [2] | Maintains circuit output and extends evolutionary longevity by automatically adjusting expression to mitigate burden. |

| Stabilization Tools | Transcription Factor-IDR fusions [8] | Forms condensates to protect circuit components from growth-mediated dilution, enhancing stability. |

| Modeling Frameworks | Host-aware ODE models, Multi-scale population models [2] | Predicts circuit behavior, burden, and evolutionary dynamics in silico before costly experimental implementation. |

Supporting Diagrams and Workflows

Diagram: Burden-Driven Evolutionary Failure of a Synthetic Gene Circuit

Diagram: Architecture of a Synthetic Gene Circuit with Controller

Growth-mediated dilution presents a fundamental challenge in synthetic biology, where the engineered gene circuits lose their functionality due to the dilution of key molecular components as host cells grow and divide. This phenomenon occurs because cell growth causes a global reduction in the concentrations of all circuit components, which can significantly destabilize circuit behavior and lead to complete functional collapse. Synthetic biology aims to program cells for useful tasks in medicine, biotechnology, and environmental engineering, but these genetic programs often fail because cell growth dilutes the key molecules needed to keep them running [8].

The problem is particularly acute in applications requiring long-term stability, such as industrial bioproduction where sustaining circuit activity during repeated culture dilutions is critical for minimizing inducer costs and ensuring consistent product yields [12]. Similarly, engineered probiotics for therapeutic applications must maintain reliable circuit performance under fluctuating nutrient conditions after ingestion [12]. Understanding and mitigating growth-mediated dilution is therefore essential for advancing synthetic biology applications from laboratory curiosities to real-world solutions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem Diagnosis Table

Table 1: Common Symptoms and Causes of Growth-Mediated Dilution Issues

| Observed Symptom | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Circuit memory loss: Inability to maintain bistable 'ON' state after removal of initial stimulus [13] | Self-activation circuit topology; Rapid dilution of transcription factors during fast growth [12] [13] | Measure temporal dynamics of fluorescence and cell density after diluting activated cells into fresh medium [13] |

| Reduced bioproduction yield in prolonged cultures [12] | Dilution of key enzymes in metabolic pathways during scale-up [12] | Monitor product formation rates across different growth phases and dilution regimes |

| Inconsistent biosensor performance under dynamic growth conditions [12] | Growth-dependent variation in transcription factor concentrations [12] | Characterize dose-response curves at different growth rates |

| Loss of population-level synchrony in coordinated behaviors [13] | Growth-mediated dilution of signaling molecules or quorum sensing components [13] | Track single-cell expression distributions over multiple generations |

Circuit Failure Mechanisms and Signatures

Table 2: Quantitative Signatures of Growth-Mediated Circuit Failures

| Failure Mechanism | Dynamic Signature | Key Parameters Affected |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous response curve deformation [7] [14] | Gradual loss of adaptation precision and sensitivity; Altered input-output relationships [7] [14] | Reduced precision (final state deviation from basal); Decreased response sensitivity [14] |

| Induced or strengthened oscillations [7] [14] | Emergence of sustained oscillations not present in non-growth conditions [7] [14] | Oscillation amplitude and period modifications; Possible circuit reconfiguration to oscillatory regime [7] |

| Sudden switching to alternative attractors [7] [14] | Bistability loss; Memory circuit failure; Hysteresis collapse [7] [13] [14] | Loss of bistable range; Reduced hysteresis width; Inability to maintain predetermined states [13] |

Figure 1: Diagnostic Framework for Growth-Mediated Dilution Issues

Experimental Protocol: Validating Phase Separation Solution

Objective: To implement and validate a phase separation strategy for buffering growth-mediated dilution in a self-activation (SA) gene circuit.

Background: This protocol describes how to engineer transcriptional condensates by fusing intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) to transcription factors, creating local concentrations that resist global dilution during cell growth [12] [15].

Materials:

- E. coli host strains (e.g., DH10B, ΔlacIΔaraCBAD mutant of MG1655)

- Plasmid constructs for SA circuit (e.g., OP174) and Drop-SA circuits (e.g., OP153 with FUSn, OP203 with RLP20)

- Inducers: L-(+)-Arabinose (Sigma A3256)

- FRAP-capable confocal microscope

- Flow cytometer

- Molecular biology reagents for cloning

Procedure:

Circuit Construction:

Transformation and Culture:

- Transform constructs into appropriate E. coli strains using standardized protocols (e.g., Zymo Research Mix & Go kit).

- Culture transformed cells in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics.

- Activate circuits by adding L-arabinose (0-10 mM range) during mid-exponential phase.

Dilution and Memory Testing:

- Dilute activated cells into fresh medium with varying L-arabinose concentrations.

- Monitor cell density (OD600) and fluorescence over time.

- Compare memory retention between SA and Drop-SA circuits.

Condensate Visualization and Validation:

- Image condensate formation using fluorescence microscopy.

- Perform FRAP (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching) to confirm liquid-liquid phase separation properties [15].

- Analyze condensate dynamics and recovery kinetics.

Quantitative Analysis:

- Measure hysteresis properties through dose-response curves under different initial conditions.

- Quantify population heterogeneity using flow cytometry.

- Calculate local concentration factors within condensates.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If condensates do not form, verify IDR fusion integrity and test different linker sequences.

- If memory improvement is suboptimal, tune expression levels and test alternative IDRs.

- Account for cell-to-cell variability by conducting sufficient replicates (≥1000 cells for microscopy) [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Addressing Growth-Mediated Dilution

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) [12] [15] | Promote phase separation through multivalent interactions; Enable condensate formation | FUSn (FUS N-terminal domain) or RLP20 (resilin-like polypeptide) fused to transcription factors [15] |

| Self-Activation (SA) Circuit [13] | Model system for studying growth-mediated memory loss; Sensitive to dilution effects | Bicistronic circuit with AraC and GFP under PBAD promoter to test memory maintenance [13] |

| Toggle Switch Circuit [13] | Alternative topology refractory to growth-mediated dilution; Double-negative feedback motif | Comparative studies with SA circuits to identify topology-dependent resilience [13] |

| FRAP (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching) [15] | Validate liquid-like properties of condensates; Measure dynamics and molecular mobility | Confirm phase separation in Drop-SA circuits; Typical recovery time ~10-11 minutes [15] |

| Growth Feedback Models [7] [14] | Computational frameworks to predict circuit-host interactions; Identify robust topologies | Systematic screening of 425+ circuit topologies for growth resilience; Parameter sampling (2×10⁵ trials) [7] [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Mechanism & Diagnosis

What exactly is growth-mediated dilution and why does it disrupt synthetic gene circuits?

Growth-mediated dilution refers to the reduction in intracellular concentration of synthetic gene circuit components that occurs as cells grow and divide. As cells increase in volume and undergo division, the molecular components of synthetic circuits (transcription factors, enzymes, signaling molecules) become distributed throughout the larger cellular volume and among daughter cells, effectively reducing their concentrations [12]. This global reduction in component concentrations can significantly destabilize circuit behavior, particularly for circuits that rely on precise concentration thresholds for proper function, such as bistable switches and oscillators [12] [13].

How can I determine if growth-mediated dilution is causing my circuit failures?

Several diagnostic approaches can help identify growth-mediated dilution as the root cause:

- Monitor the temporal dynamics of circuit components during growth phases: rapid decline in expression levels during exponential growth followed by recovery in stationary phase suggests dilution effects [13].

- Compare circuit performance in fast-growing versus slow-growing conditions: growth-mediated issues will show condition-dependent failures [7].

- Test circuit memory by activating circuits then diluting into fresh medium: inability to maintain state indicates dilution problems [13].

- Use control circuits with different topologies known to have varying sensitivity to growth feedback (e.g., compare self-activation vs. toggle switches) [13].

Are certain circuit topologies more vulnerable to growth-mediated dilution?

Yes, circuit topology significantly influences vulnerability to growth-mediated dilution. Self-activation circuits implementing positive autoregulation are particularly sensitive to dilution effects and quickly lose memory function during rapid growth [13]. In contrast, toggle switches with double-negative feedback motifs are more refractory to growth-mediated dilution and can maintain memory better under dynamic growth conditions [13]. Systematic studies of 425 adaptive circuit topologies revealed that only a small subset maintains optimal performance under growth feedback, highlighting the importance of topology selection [7] [14].

Solutions & Implementation

What is the phase separation strategy for combating growth-mediated dilution?

The phase separation strategy involves engineering biomolecular condensates that locally concentrate transcription factors at promoter regions, creating protected microenvironments that resist global dilution [12] [8]. This is achieved by fusing intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) to transcription factors, enabling them to form liquid-like droplets through liquid-liquid phase separation [12] [15]. These condensates maintain high local concentrations of key circuit components even as average cellular concentrations decrease during growth, thereby preserving circuit function [12] [15].

Figure 2: Mechanism of Phase Separation in Countering Growth-Mediated Dilution

What specific IDRs have been successfully used to buffer against growth-mediated dilution?

Two main types of IDRs have been experimentally validated for this application:

- FUSn: The N-terminal intrinsically disordered domain of the Fused in Sarcoma protein, a natural IDR known to promote liquid-liquid phase separation through multivalent interactions [15].

- RLP20: A synthetic resilin-like polypeptide engineered to drive biomolecular condensate formation with tunable properties [15]. Both have been successfully fused to transcription factors (AraC) in self-activation circuits, forming condensates at polar regions in E. coli and maintaining circuit memory under growth conditions that disrupt standard circuits [15].

How do I validate that my engineered condensates are functioning properly?

Several validation methods can confirm proper condensate function:

- Fluorescence Microscopy: Visualize condensate formation as bright, concentrated foci, typically at polar regions in bacteria [15].

- FRAP Analysis: Photobleach condensates and monitor fluorescence recovery, with typical recovery times of ~10-11 minutes confirming liquid-like properties [15].

- Hysteresis Testing: Compare dose-response curves under different initial conditions to confirm memory preservation in Drop-SA circuits [15].

- Single-Cell Analysis: Use flow cytometry to quantify population heterogeneity and identify cells with successful condensate formation [15].

Are there alternative strategies beyond phase separation for mitigating growth-mediated dilution?

Yes, several complementary strategies exist:

- Circuit Topology Engineering: Selecting naturally resilient topologies (e.g., toggle switches over self-activation circuits) [13].

- Growth Feedback Controllers: Implementing genetic controllers that monitor and regulate circuit function based on growth signals [2].

- Post-transcriptional Regulation: Using small RNAs for control, which may provide amplification enabling strong regulation with reduced burden [2].

- Host-Aware Design: Using computational frameworks that account for circuit-host interactions during the design process [2].

- Negative Autoregulation: Implementing feedback loops that can prolong short-term circuit performance [2].

Applications & Optimization

In which applications is addressing growth-mediated dilution most critical?

Growth-mediated dilution mitigation is particularly important for:

- Industrial Bioproduction: Where sustaining circuit activity during repeated culture dilutions for scale-up is critical for minimizing inducer costs and ensuring consistent product yields [12].

- Engineered Probiotics and Microbiome Therapeutics: Where therapeutic microbes must grow and divide under fluctuating nutrient conditions after ingestion while maintaining circuit function [12].

- Long-term Biosensing: Where reliable circuit performance under dynamically changing growth environments is essential for consistent detection signals [12].

- Cancer Therapeutics: Where engineered bacterial therapies must maintain function through multiple growth cycles in dynamic tumor environments [12].

What are the key metrics for evaluating solutions to growth-mediated dilution?

Several quantitative metrics can evaluate mitigation strategies:

- Memory Retention: Ability to maintain bistable states through growth phases [15] [13].

- Hysteresis Range: Width of bistable region in dose-response curves [15].

- Functional Half-life: Time for circuit output to fall by 50% (τ50) [2].

- Stability Duration: Time circuit maintains performance within ±10% of initial (τ±10) [2].

- Production Yield: Total output of desired products in bioproduction applications [12] [8].

- Precision and Sensitivity: Maintenance of adaptation properties in responsive circuits [7] [14].

How scalable is the phase separation approach for complex genetic circuits?

Current evidence suggests phase separation is a promising and potentially generalizable strategy [12] [8]. The minimal modification required (adding IDR fusions to key transcription factors) makes it applicable to various circuit designs without complete redesign [12]. Research demonstrates successful application in both simple self-activation circuits and more complex systems like cinnamic acid biosynthesis pathways [12] [8]. However, optimal implementation may require balancing condensate properties with circuit function and careful selection of IDR-cargo combinations to avoid unintended interactions [15].

Advanced Designs and Systems for Robust Circuit Function

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions for the DIAL System

This guide provides targeted troubleshooting for researchers implementing the DIAL (Dialable) promoter system to achieve precise, heritable set-points of transgene expression.

System Setup and Initial Transfection

Q: After transfection, my flow cytometry shows a completely bimodal expression profile (ON and OFF populations) instead of a uniform unimodal peak. What went wrong?

- Potential Cause 1: The synthetic Zinc Finger Activator (ZFa) is too strong. The DIAL system is designed for uniform, unimodal expression, but certain powerful transactivation domains can overwhelm this, leading to bistability and bimodality [16].

- Solution: Titrate the amount of ZFa plasmid used in transfection or switch to a ZFa with a weaker transactivation domain (e.g., from the COMET toolkit) [16]. The system should be characterized with ZFas that generate unimodal setpoints for reliable control [16].

- Potential Cause 2: Inefficient or uneven transfection. A bimodal distribution can simply mean that only a fraction of the cells received the genetic circuit.

- Solution:

- Always use a co-transfection marker (e.g., a constitutively expressed fluorescent protein on a separate plasmid) to gate and analyze only the successfully transfected cell population during flow cytometry [16].

- Optimize your transfection protocol for your specific cell line to improve efficiency and consistency. Consider using lentiviral delivery for more stable integration and uniform uptake, especially in primary cells and iPSCs [16].

Q: I am observing high background expression even in the absence of the ZFa ("OFF" state is not off).

- Potential Cause: Promoter leakiness. The minimal core promoter or the spacer sequence itself may have low-level basal activity.

- Solution:

- Verify the specificity of your ZFa and its binding sites. Ensure the ZFa binding sites are fully orthogonal to the host cell's native transcription factors [16].

- Test different minimal promoters or adjust the spacer sequence to minimize background activity. The DIAL framework is modular and allows for such optimizations [16].

Recombinase-Mediated Editing

Q: I've added Cre recombinase, but the shift to a higher expression setpoint is inefficient or incomplete.

- Potential Cause 1: Low recombinase activity or delivery issue. The Cre enzyme may not be active enough or may not have reached all cells.

- Solution:

- Validate Cre recombinase activity using a separate reporter cell line (e.g., a tdTomato-to-GFP switch reporter).

- Ensure you are using a reliable delivery method for Cre (e.g., high-efficiency transfection, cell-penetrating Cre protein, or adenoviral delivery).

- Confirm successful spacer excision by performing genotyping PCR on the extracted circuit DNA from your cell population. A successful edit will show a shorter PCR band corresponding to the excised promoter [16].

- Potential Cause 2: The spacer length is too long. While longer spacers increase the dynamic range, they might also make the initial state too repressed, and the edited state might not reach the desired absolute level [16].

- Solution: Consult the table below and consider using a DIAL promoter with a shorter spacer length for a more robust fold-change that meets your experimental needs.

Q: How do I design a DIAL system with more than two setpoints (e.g., Low, Med, High, Off)?

- Solution: Implement a nested DIAL promoter architecture. This involves incorporating multiple, orthogonal recombinase sites (e.g., loxP, FRT for Flp recombinase) within the spacer. By using different recombinases sequentially or in combination, you can create a series of progressively shorter spacers, thereby generating multiple discrete setpoints from a single promoter [3] [16].

Expression Stability and Long-Term Performance

Q: My carefully set expression level drifts down over multiple cell divisions. How can I maintain a stable setpoint?

- Potential Cause: Evolutionary burden and dilution. Cells expressing a high level of a non-essential transgene experience a growth disadvantage. Over time, faster-growing mutants with reduced expression (e.g., due to promoter mutations) will outcompete the ancestral engineered cells [2].

- Solution 1: Leverage the heritability of DIAL setpoints. A key advantage of the DIAL system is that the promoter edit is genetically encoded and stable. Once a setpoint is established via recombinase action, it is maintained heritably in daughter cells without the need for continuous input [16]. Ensure you are using a delivery method (like lentivirus) that promotes genomic integration for long-term stability.

- Solution 2: Integrate stability-enhancing genetic controllers. For very long-term cultures, consider implementing feedback circuits that couple essential host functions to your transgene. "Host-aware" designs, such as negative autoregulation or growth-based feedback, can theoretically improve evolutionary longevity by reducing the selective advantage of loss-of-function mutants [2].

- Solution 3: Explore biomolecular condensates. Emerging strategies involve fusing transcription factors to intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) to drive liquid-liquid phase separation. These transcriptional condensates form at the promoter and can buffer against growth-mediated dilution, helping to maintain consistent expression levels across dynamic growth conditions [8].

Q: The expression in my cell population is highly variable, making it difficult to map levels to a phenotypic output.

- Potential Cause: The setpoint itself is not unimodal. This returns to the initial issue of using an appropriate ZFa and ensuring uniform delivery. For mapping gene dosage to phenotypes, a unimodal, uniform population response is critical [16].

- Solution:

- Re-optimize the ZFa strength and transfection as described in the first FAQ.

- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate a cell population with a very narrow range of expression after the setpoint has been established. This will create a more homogeneous starting population for your phenotype assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Synthetic Zinc Finger Activators (ZFas) | Engineered transcription factors that bind orthogonal DNA sequences upstream of the minimal promoter. Different ZFa strengths (e.g., by varying the transactivation domain) allow for tuning the system's maximum output [16]. |

| DIAL Promoter Construct | The core genetic component containing tessellated ZFa binding sites, an excisable "spacer" sequence, and a minimal core promoter (e.g., TATA). Spacer length is a key tunable parameter [16]. |

| Cre Recombinase (and other site-specific recombinases) | Enzyme that catalyzes the excision of the DNA spacer flanked by its recognition sites (e.g., loxP), bringing the promoter closer to the transcription start site and shifting expression to a higher setpoint [3] [16]. |

| Lentiviral Delivery System | A method for stably integrating the DIAL circuit into the genome of hard-to-transfect cells, such as primary cells and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [16]. |

| Co-transfection Marker | A fluorescent protein expressed from a separate, constitutive promoter. It allows for identifying and gating on successfully transfected cells during flow cytometry analysis, ensuring you only analyze cells that received the circuit [16]. |

Quantitative Data for DIAL System Design

Table 1: Impact of Spacer Length on DIAL Promoter Output

| Spacer Length (base pairs) | Relative Expression (Pre-Excision) | Fold Change (Post- vs. Pre-Excision) |

|---|---|---|

| 27 bp | High | Low |

| 203 bp | Medium | Medium |

| 263 bp | Low | High |

This table summarizes the tunability of the DIAL system. Increasing the length of the excisable spacer sequence decreases the initial ("Low" setpoint) expression level and correspondingly increases the fold-change achieved after Cre-mediated excision [16].

Table 2: Comparison of Stability-Enhancing Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIAL (Heritable Editing) | Genetically encoded, permanent promoter shortening after a one-time recombinase input [16]. | Stable, set-and-forget control; no ongoing resource drain on the cell. | Setpoints are fixed and not easily reversible. |

| Transcriptional Feedback | Negative autoregulation senses and adjusts circuit output [2]. | Can improve short-term stability and reduce burden. | Controller itself consumes resources; can be evolutionarily disrupted. |

| Phase Separation (Condensates) | Concentrates transcriptional machinery via liquid-liquid phase separation to buffer against dilution [8]. | A physical principle that enhances robustness under dynamic growth. | A nascent technology; requires fusion of specific protein domains (IDRs). |

Experimental Workflow and Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of the DIAL system and a general workflow for its implementation and troubleshooting.

DIAL System Mechanism and Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary benefits of using negative autoregulation in a gene circuit?

Negative autoregulation (NAR), where a transcription factor represses its own promoter, provides two key advantages for synthetic gene circuits:

- Linearized Dose-Response: It can transform a steep, sigmoidal (non-linear) input-output dose-response into a linear one. This allows for more precise and graded control of gene expression over a wide range of inducer concentrations [17].

- Reduced Expression Noise: It significantly reduces cell-to-cell variability (noise) in gene expression. Experiments in yeast showed up to a 7-fold reduction in noise at intermediate induction levels, leading to a more uniform population response [17].

FAQ 2: My gene circuit's output is declining over multiple cell generations. What could be causing this?

This is a classic sign of evolutionary instability. Circuits that impose a high metabolic burden on the host cell slow its growth. Over time, faster-growing mutant cells that have lost or impaired circuit function will outcompete the original engineered cells [2]. This is a fundamental challenge in synthetic biology.

FAQ 3: What design strategies can I use to make my gene circuit more evolutionarily stable?

Controller architectures that use feedback to minimize burden can significantly extend functional longevity. Computational and experimental studies suggest:

- For Short-Term Performance: Negative autoregulation can help maintain function initially [2].

- For Long-Term Persistence: Growth-based feedback controllers, which sense and respond to the host's growth rate, can outperform other types. Post-transcriptional controllers using small RNAs (sRNAs) can also provide stronger control with less burden than transcriptional controllers [2].

- Multi-Input Controllers: Designs that combine different feedback mechanisms (e.g., sensing both circuit output and growth rate) can improve both short-term and long-term performance [2].

FAQ 4: My circuit is exhibiting high cell-to-cell variability (noise). How can I troubleshoot this?

High noise can stem from several sources. The table below outlines common causes and solutions.

| Cause | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|

| Low or Insufficient Sample | Ensure sample volume is at least 10 µL for fragment analysis. For sequencing samples cleaned with BigDye XTerminator, use a minimum of 65 µL [18]. |

| Old or Expired Reagents | Replace expired cartridges, cathode buffer containers, or other reagents before re-running samples [18]. |

| Sample Degradation | Limit the time samples are stored on-instrument. For long runs, limit plates to 48 samples. Ensure Hi-Di Formamide is less than a year old and has undergone fewer than 8 freeze-thaw cycles [18]. |

| Incorrect Dye Calibration | Perform a new spectral calibration using matrix standards and verify the correct dye set is selected in the plate setup software [18]. |

| Fundamental Circuit Design | Consider redesigning your circuit to include negative autoregulation, a known motif for noise reduction [17] [19]. |

FAQ 5: How does growth feedback generally affect gene circuit function?

Growth feedback is a major circuit-host interaction where the circuit affects cell growth, and growth in turn affects gene expression by diluting cellular components. A systematic study of over 400 adaptation circuits found it can cause failure through three main mechanisms [7]:

- Continuous Deformation: The response curve becomes distorted.

- Induced Oscillations: The circuit begins to oscillate unpredictably.

- Sudden Switching: The circuit jumps to a different, unintended stable state. Despite these generally negative effects, a small subset of circuit topologies is naturally robust to growth feedback [7].

Quantitative Data and Design Principles

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Genetic Controller Architectures [2]

| Controller Architecture | Key Feature | Short-Term Performance (τ±10) | Long-Term Persistence (τ50) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Loop (No Control) | No feedback | Low | Low | Baseline for comparison |

| Intra-Circuit Feedback | Negative autoregulation of circuit genes | High | Medium | Good initial performance |

| Growth-Based Feedback | Actuation based on host growth rate | Medium | High | Best long-term circuit survival |

| Post-Transcriptional Control | Uses sRNAs for silencing | Varies | High | Strong control with low burden |

Design Principle: Speeding Up Circuit Response Time The response time of a simple gene expression system is determined by the protein degradation rate (γ). A faster response can be achieved by destabilizing the protein (increasing γ). To maintain the same steady-state concentration, the production rate (β) must be increased proportionally. This creates a futile cycle but pays off in speed [19]. Negative autoregulation is a network motif that also accelerates the turn-on time of a gene's expression [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Negative Autoregulatory "Linearizer" Circuit

This protocol is based on the construction and validation of a linearizer circuit in yeast [17].

- Circuit Design: Replace the constitutive promoter driving your transcription factor (e.g., TetR) with a promoter that the TF itself can repress (e.g., PGAL1-D12 for TetR). This creates a negative feedback loop on the regulator.

- Chromosomal Integration: Integrate the regulator and reporter (e.g., yEGFP) parts separately into the host chromosome to minimize copy number variability.

- Induction Curve Measurement:

- Culture cells harboring the circuit across a wide range of inducer concentrations (e.g., 0-100 ng/mL anhydrotetracycline (ATc)).

- Use flow cytometry to measure the population mean and distribution of the reporter fluorescence at each concentration.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the mean fluorescence against the inducer concentration.

- A successful linearizer circuit will show a linear relationship (R² ≈ 0.99) from no induction up to ~90% saturation, unlike the sigmoidal curve of a non-autoregulatory cascade.

- The fluorescence distribution histograms should remain unimodal and narrow across all concentrations, indicating low noise.

Protocol 2: In Silico Modeling of Circuit Evolution with Growth Feedback

This protocol uses a multi-scale computational framework to predict circuit longevity [2].

- Model Formulation:

- Develop a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe host-circuit interactions, including resource consumption (ribosomes, amino acids) and its impact on cellular growth rate.

- Key variables are often in molecules per cell.

- Define Mutation Scheme:

- Implement a state-transition model with several "mutation states" (e.g., 100%, 67%, 33%, 0% of nominal expression).

- Set transition rates so that function-reducing mutations are more likely.

- Simulate Population Dynamics:

- Run the model in repeated batch conditions (nutrient replenishment every 24 hours).

- Track the competition between different mutant strains and the total population-level output over time.

- Quantify Longevity:

- P₀: Record the initial total output.

- τ±10: Calculate the time for the total output to fall outside P₀ ± 10%.

- τ₅₀: Calculate the time for the total output to fall below P₀/2.

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Negative Autoregulation with Growth Feedback This diagram illustrates the core logic of a negatively autoregulated circuit operating within a host cell. The transcription factor (TF) represses both its own gene and the output gene. The resulting output protein can impose a metabolic burden, reducing the host's growth rate. The growth rate, in turn, feeds back into the system by diluting all cellular proteins, creating a complex interaction that impacts circuit stability and longevity [17] [7] [2].

Diagram 2: Bistable Toggle Switch States The genetic toggle switch is a classic bistable system with two stable states (A and B). The intermediate state is unstable; without external control, stochastic fluctuations quickly push cells into one of the two stable attractors. Real-time feedback control can be used to maintain the population in this unstable state [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Genetic Controller Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Anhydrotetracycline (ATc) | Small-molecule inducer; binds to and inactivates the TetR repressor, allowing gene expression. | Used in TetR-based systems (e.g., [17] [20]). |

| IPTG | Small-molecule inducer; binds to and inactivates the LacI repressor, allowing gene expression. | Used in LacI-based systems (e.g., [20]). |

| Cre Recombinase | Enzyme that catalyzes site-specific recombination of DNA between two loxP sites. | Used in the DIAL system to edit expression setpoints by excising DNA spacers [3]. |

| Microfluidic Device | Allows for long-term, single-cell imaging and dynamic control of the cellular environment. | Critical for real-time feedback control experiments (e.g., [20]). |

| Flow Cytometer | Measures fluorescence of individual cells in a population, enabling quantification of mean expression and noise. | Essential for characterizing dose-response and cell-to-cell variability [17]. |

| Spectral Calibration Standards | Used to calibrate fluorescent dye detection systems, ensuring accurate signal measurement. | Necessary for troubleshooting pull-up/pull-down artifacts in data [18]. |

| BigDye XTerminator Kit | Reagent for purifying sequencing reactions to remove unincorporated terminators. | Insufficient cleanup can cause low signal or dye blobs [18]. |

| Hi-Di Formamide | Used for sample denaturation before capillary electrophoresis sequencing. | Age and freeze-thaw cycles can degrade sample resolution [18]. |

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers and scientists in troubleshooting common issues encountered when working with recombinase and CRISPR-based synthetic gene circuits for memory and logic operations. The guidance is framed within the broader thesis of troubleshooting synthetic gene circuit expression and stability, addressing specific experimental challenges related to genetic instability, burden, and unpredictable performance to enhance the reliability of your research and drug development applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common reasons my synthetic gene circuit loses function over time? Circuit failure often stems from genetic instability. The primary cause is the metabolic burden imposed by the circuit, which slows host cell growth. This creates a selective pressure for faster-growing mutants that have inactivated or lost the circuit function. Common failure modes include plasmid loss due to segregation errors, recombination-mediated deletion of repeated genetic sequences, and disruptive insertions from transposable elements [21].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the long-term evolutionary stability of my recombinase-based memory device? Two complementary strategies are "suppressing mutant emergence" and "suppressing the relative fitness of mutants." You can achieve this by:

- Genomic Integration: Integrating your circuit into the host genome to prevent plasmid loss [21].

- Reducing Genetic Repeats: Minimizing the use of repeated sequences (like identical promoters or terminators) to lower the risk of recombination [21].

- Using Reduced-Genome Hosts: Employing engineered chassis organisms with deleted transposable elements to lower the background mutation rate [21].

- Implementing Genetic Controllers: Designing feedback controllers that sense circuit output or host growth rate and adjust expression to reduce burden, thereby extending functional half-life [2].

FAQ 3: Why does my circuit function correctly in a test tube but fail inside a mammalian cell? This is frequently due to context dependence and host-circuit interactions. A circuit that is well-characterized in one organism (e.g., E. coli) may behave unpredictably in another (e.g., mammalian cells) due to differences in endogenous machinery, resource pools, and unintended interactions with native cellular components [22]. Furthermore, the metabolic burden of the circuit can differ significantly between hosts, leading to toxic effects or strong selection against circuit-bearing cells [22] [21].

FAQ 4: What can I do if my circuit shows high cell-to-cell variability (noise) in its output? High noise often results from the stochastic nature of biochemical reactions involving small numbers of molecules. This can be intrinsic (from the circuit itself) or extrinsic (from global fluctuations in cellular resources). Strategies to address this include:

- Using Orthogonal Parts: Employing genetic components (e.g., polymerases, ribosomes) that do not interact with the host's native systems to decouple from global fluctuations [22].

- Implementing Feedback Control: Negative feedback architectures can suppress variation and stabilize output [2].

- Characterizing Parts in Context: Using cell-free systems for rapid, high-throughput characterization of genetic parts before implementing them in living cells [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low or No Circuit Output

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Part Failure | Sequence circuit to check for mutations; Verify part activity with a reporter assay in a validated host. | Re-clone the defective part; Use well-characterized, high-quality parts from repositories. |

| Host-Circuit Incompatibility | Measure host growth rate with and without circuit; Perform RNA-seq to identify unintended interactions [22]. | Switch to a more compatible chassis (e.g., reduced-genome strain); Refactor the circuit to use more orthogonal parts [21]. |

| Excessive Metabolic Burden | Quantify the reduction in host growth rate upon circuit activation [21]. | Lower constitutive expression levels; Use inducible systems; Implement burden-aware feedback controllers [2]. |

| Incorrect Assembly (Recombinase Circuits) | Verify the orientation of genetic elements (promoters, genes) flanked by recombinase sites after induction [23] [24]. | Ensure the DNA sequence is "well-formed" per syntactic rules; Confirm recombinase specificity and activity [23]. |

Problem: Genetic Instability and Loss of Memory

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid Loss | Plate cells on selective and non-selective media to count plasmid-retaining colonies. | Integrate the circuit into the host chromosome; Use stable, low-copy-number plasmids [21]. |

| Evolutionary Escape | Serial passage cells for multiple generations and track functional output and population genetics [21] [2]. | Couple circuit function to an essential gene (e.g., for antibiotic resistance); Use kill-switch circuits to eliminate non-functional cells [21]. |

| Mutation in Key Parts | Isolate non-functional cells and sequence the entire circuit to identify inactivating mutations. | Avoid repeated sequences; Use robust, host-aware genetic designs; Distribute large populations into smaller, segregated compartments to confine mutants [21]. |

Problem: Unintended Logic or Leaky Expression

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinase Crosstalk | Test each recombinase individually and in combination for orthogonality. | Use bioinformatic tools to select highly orthogonal recombinase/att-site pairs [24]. |

| Promoter Interference | Characterize the activity of each promoter in isolation and in the final circuit context [22]. | Re-design circuit layout; Introduce insulating sequences between genetic parts. |

| Resource Overload | Model resource allocation (ribosomes, nucleotides) to identify potential bottlenecks [22]. | Re-balance expression levels of circuit components; Use resource-aware whole-cell models during the design phase [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Serial Passaging to Quantify Evolutionary Stability

Purpose: To experimentally determine the functional half-life of a synthetic gene circuit under prolonged cultivation.

Materials:

- Engineered bacterial strain with gene circuit.

- Appropriate liquid growth medium (e.g., LB).

- Sterile flasks or culture tubes.

- Incubator/shaker.

- Flow cytometer or plate reader for output measurement (e.g., GFP).

Methodology:

- Inoculation: Start a batch culture by inoculating the engineered strain into fresh medium.

- Growth and Dilution: Grow the culture for a set period (e.g., 24 hours). Each day, dilute an aliquot of the culture into fresh medium to maintain continuous growth. A typical dilution is 1:100 to 1:1000.

- Monitoring: At each passage, sample the culture to:

- Measure Circuit Output: Use fluorescence or other assays to quantify the population-level function.

- Measure Growth Rate: Track optical density (OD) over time.

- Check for Mutants: Plate cells to isolate single colonies and screen for loss-of-function phenotypes.

- Analysis: Continue for 10+ generations. Plot the population-level output over time. The "half-life" (τ50) is the time taken for the output to fall to 50% of its initial value [2].

Protocol 2: Validating Recombinase-Based Logic Gates

Purpose: To confirm the correct truth table operation of a recombinase-based logic gate.

Materials:

- Bacterial strains harboring the recombinase-based logic circuit.

- Chemical inducers for the specific recombinase promoters (e.g., AHL, aTc).

- Solid and liquid growth media.

- Flow cytometer or fluorescence microscope.

Methodology:

- Induction: For each possible input combination (e.g., No inducer, Inducer A, Inducer B, Both inducers), grow separate cultures and add the corresponding inducers.

- Incubation: Allow sufficient time for recombinase expression and DNA recombination to occur (typically 12-24 hours).

- Measurement: Analyze the output (e.g., GFP fluorescence) using flow cytometry to determine the ON/OFF state for each input condition.

- Verification: Isolate genomic DNA from cells in each state and perform PCR or sequencing across the recombinase sites to confirm the expected DNA inversion or excision pattern matches the logical output [23] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Orthogonal Serine Recombinases (Bxb1, phiC31) | Enzyme that catalyzes irreversible DNA inversion, excision, or integration between specific attP and attB sites. Used as the core processor in logic and memory circuits [23] [24]. |

| Well-Formed Sequence (WFS) DNA Constructs | A syntactically correct DNA sequence where genetic elements (promoters, genes) are flanked by recombinase targeting sites. Essential for predictable circuit behavior [23]. |

| Reduced-Genome E. coli Strains (e.g., MDS42) | Chassis with transposable elements and genomic islands removed. Reduces the rate of insertion-sequence-mediated circuit failure, enhancing genetic stability [21]. |

| Host-Aware Model Framework | A computational model that simulates interactions between circuit expression and host resource pools (ribosomes, energy). Used to predict burden and evolutionary dynamics in silico before building the circuit [2]. |

| Genetic Feedback Controllers | A synthetic module that senses a signal (e.g., circuit output, growth rate) and uses negative feedback to actuate the circuit (e.g., via sRNAs). Mitigates burden and extends functional longevity [2]. |

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram: Recombinase Logic Gate Mechanism

Diagram: Circuit Stability Troubleshooting Workflow

FAQs: Core Concepts and Applications

FAQ 1: What is the primary functional advantage of using transcriptional condensates to stabilize synthetic gene circuits?

The primary advantage is the ability to buffer against growth-mediated dilution. As cells grow and divide, key transcription factors (TFs) in synthetic circuits become diluted, leading to circuit failure. Transcriptional condensates concentrate these TFs at their target promoters, creating a local high-concentration environment that is resilient to global dilution in the cell, thereby maintaining consistent gene expression and circuit function across cell generations [8] [15].

FAQ 2: My synthetic circuit loses its bistable memory after cell division. Can phase separation help?

Yes. This is a common failure mode where dilution of TFs disrupts the self-reinforcing loop of a bistable switch. By fusing an Intrinsically Disordered Region (IDR) to your circuit's transcription factor, you can promote the formation of condensates. These condensates maintain a high local TF concentration at the promoter, which preserves the bistable "ON" state even after rapid cell growth and division, effectively restoring the circuit's memory function [15].

FAQ 3: Are transcriptional condensates a form of irreversible, hard-wired memory for cells?

No. Condensates stabilized through phase separation provide a form of dynamic and reversible memory. Unlike memory circuits built with DNA recombinases that create permanent, irreversible genetic changes [10], condensate-based stabilization is physical and tunable. The condensates can form and dissolve in response to cellular conditions, allowing for dynamic control while still providing protection against dilution during growth phases [8] [26].

FAQ 4: What is the most critical component for engineering phase separation into a synthetic circuit?

The most critical components are Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs). IDRs are protein domains that lack a fixed 3D structure and facilitate weak, multivalent interactions. By fusing a well-characterized IDR (e.g., from the FUS protein or a synthetic resilin-like polypeptide) to your transcription factor, you can drive the assembly of biomolecular condensates at the promoter site [8] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: My Condensates Are Not Forming

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No visible condensates under microscope. | The fused IDR has weak phase-separation capability. | Switch to a stronger IDR, such as the N-terminal domain of FUS (FUSn) or a synthetic RLP [15]. |

| Diffuse fluorescence throughout the cell. | The expression level of the fusion protein is too low to reach the concentration threshold for phase separation. | Optimize the promoter strength or ribosome binding site (RBS) to increase protein expression [15]. |

| Condensates form in the wrong cellular location. | The fusion protein lacks proper localization signals. | Include localization sequences in your construct to target the transcription factor and its condensate to the nuclear or promoter region. |

Guide 2: My Circuit Memory is Still Unstable

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Circuit loses memory after prolonged growth. | Condensates are dissipating or not dense enough to maintain a critical TF concentration. | Experiment with different IDRs to tune the stability and physical properties of the condensates. Validate via FRAP to ensure they are liquid-like and dynamic [15]. |

| High cell-to-cell variability in memory retention. | Stochastic formation or dissolution of condensates in individual cells. | Use a stronger, more consistent promoter to express the TF-IDR fusion protein and reduce expression noise. Model the system to understand the stochastic dynamics [15]. |

| The circuit imposes a high metabolic burden. | Overexpression of synthetic genes drains cellular resources. | Consider integrating a resource allocation controller or optimizing codon usage to reduce the burden on the host cell [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Phase-Separation-Stabilized Gene Circuit

This protocol outlines the key steps for engineering a synthetic self-activation (SA) circuit that uses transcriptional condensates for stability, based on the Droplet-Self-Activation (Drop-SA) design [15].

1. Design and Cloning:

- Core Circuit: Assemble a bicistronic self-activation circuit where the transcription factor (e.g., AraC) and a reporter (e.g., GFP) are under the control of a inducible promoter (e.g., Pbad).

- IDR Fusion: Genetically fuse a selected IDR (e.g., FUSn or RLP20) to the C-terminus of the transcription factor. For visualization and validation, the construct can be a triple fusion: GFP-IDR-TF (e.g., GFP-FUSn-AraC).

- Cloning: Use standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., Gibson assembly, Golden Gate) to clone the final construct into an appropriate plasmid vector.

2. Transformation and Cell Culture:

- Transform the constructed plasmid into your host cell line (e.g., E. coli).

- Culture the cells in a suitable medium. To test the circuit, grow cells to mid-log phase and activate the circuit by adding an inducer (e.g., L-arabinose for the Pbad promoter).

3. Validation and Imaging:

- Condensate Formation: Use fluorescence microscopy to check for the formation of bright, punctate droplets (condensates) within the cells, typically localizing at the cell poles in bacteria.