The Synthetic Biology DBTL Cycle: A Comprehensive Guide for Accelerating Research and Drug Development

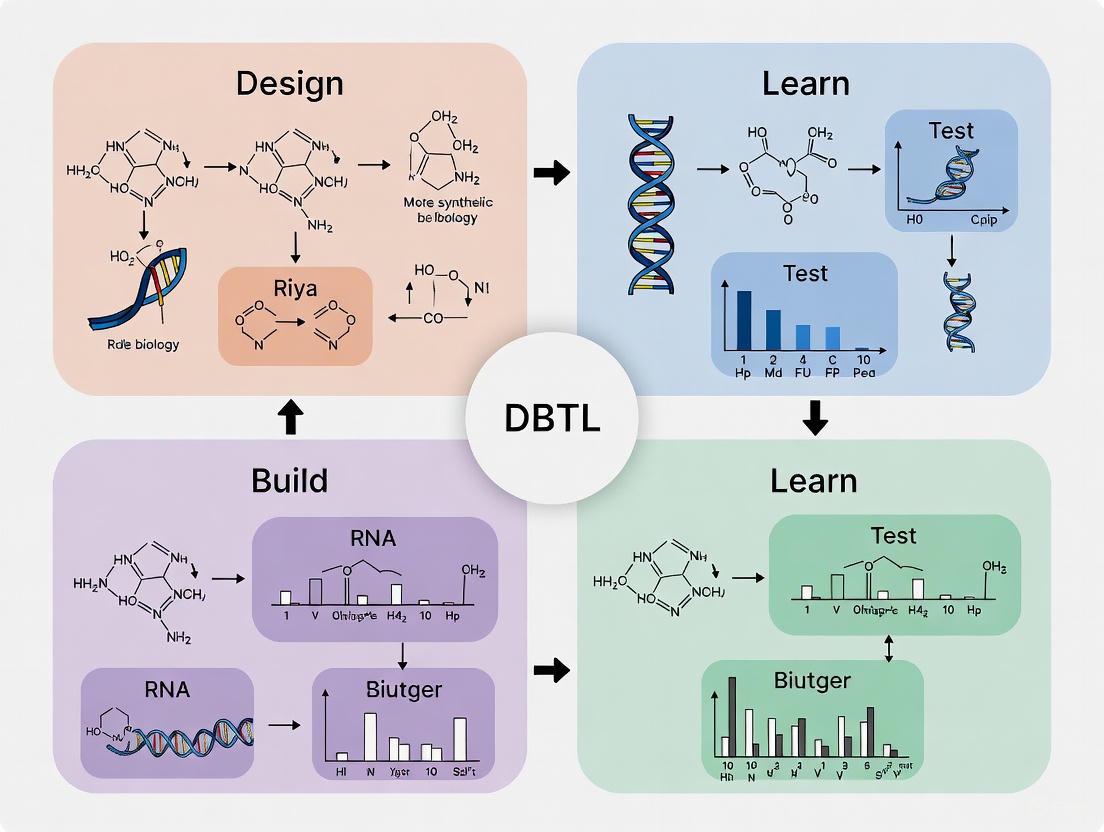

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, the foundational framework of synthetic biology.

The Synthetic Biology DBTL Cycle: A Comprehensive Guide for Accelerating Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, the foundational framework of synthetic biology. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the core principles of each phase, from initial genetic design to data-driven learning. It delves into advanced methodologies, including the integration of machine learning and laboratory automation, to optimize the cycle for efficiency and predictability. The content also covers practical troubleshooting strategies and validates the approach with real-world case studies, illustrating how the DBTL cycle is revolutionizing the engineering of biological systems for therapeutic and industrial applications.

Deconstructing the DBTL Cycle: The Core Engine of Synthetic Biology

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a systematic, iterative framework that serves as the cornerstone of modern synthetic biology and metabolic engineering [1]. This engineering-based approach provides a structured methodology for developing and optimizing biological systems, enabling researchers to engineer organisms for specific functions such as producing biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and other valuable compounds [1]. The power of the DBTL framework lies in its recursive nature, allowing for continuous refinement of biological designs through successive iterations that progressively incorporate knowledge from previous cycles.

The DBTL cycle has become particularly vital in addressing the fundamental challenge of synthetic biology: the difficulty of predicting how introduced genetic modifications will function within the complex, interconnected networks of a living cell [1]. Even with rational design, the impact of foreign DNA on cellular processes can be unpredictable, necessitating the testing of multiple permutations to achieve desired outcomes [1]. By emphasizing modular design of biological parts and automating assembly processes, the DBTL framework enables researchers to efficiently explore a vast design space while systematically accumulating knowledge about the system's behavior.

The Four Phases of the DBTL Cycle

Design Phase

The Design phase constitutes the initial planning stage where researchers define specific objectives for the desired biological function and computationally design the genetic parts or systems required to achieve these goals [2]. This phase relies heavily on domain expertise, bioinformatics, and computational modeling tools to create blueprints for genetic constructs [2] [3]. During design, researchers select appropriate biological components such as promoters, ribosomal binding sites (RBS), coding sequences, and terminators, considering their compatibility and potential interactions within the host system [4].

The design process often involves the application of specialized software and computational tools that leverage prior knowledge about biological parts and systems. In traditional DBTL cycles, this phase primarily draws upon existing biological knowledge and first principles. However, with the integration of machine learning, the design phase has been transformed through the application of predictive models that can generate more optimized starting designs [2] [5]. The emergence of sophisticated protein language models (such as ESM and ProGen) and structure-based design tools (like ProteinMPNN and MutCompute) has enabled more intelligent and effective design strategies that increase the likelihood of success in subsequent phases [2].

Build Phase

In the Build phase, the computationally designed genetic constructs are physically realized through laboratory synthesis and assembly [2]. This process involves synthesizing DNA sequences, assembling them into plasmids or other vectors, and introducing these constructs into a suitable host system for characterization [2] [1]. Host systems can include various in vivo platforms such as bacterial, yeast, mammalian, or plant cells, as well as in vitro cell-free expression systems [2].

The Build phase has been dramatically accelerated through automation and standardization of molecular biology techniques. Automated platforms enable high-throughput assembly of genetic constructs, significantly reducing the time, labor, and cost associated with creating multiple design variants [1]. This automation is crucial for generating the large, diverse libraries of biological strains needed for comprehensive screening and optimization [1]. The Build phase also encompasses genome engineering techniques such as multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) and CRISPR-based editing, which allow for precise genetic modifications in host organisms [3]. Recent advances have particularly highlighted the value of cell-free transcription-translation (TX-TL) systems as rapid building platforms that circumvent the complexities of engineering living cells [2] [6].

Test Phase

The Test phase focuses on experimentally characterizing the performance of the built biological constructs through functional assays and analytical methods [1]. This phase determines the efficacy of the design and build processes by quantitatively measuring key performance indicators such as protein expression levels, metabolic flux, product yield, growth characteristics, and other relevant phenotypic metrics [2] [4].

High-throughput screening technologies have revolutionized the Test phase by enabling rapid evaluation of thousands of variants in parallel [3]. Advanced analytical techniques including next-generation sequencing, proteomics, metabolomics, and fluxomics provide comprehensive data on system behavior at multiple molecular levels [3]. The integration of microfluidics, robotics, and automated imaging systems has further enhanced testing capabilities, allowing for massive parallelization of assays while reducing reagent costs and time requirements [2]. For metabolic engineering applications, testing often occurs in controlled bioreactor environments where critical process parameters can be systematically varied and monitored to assess strain performance under different conditions [4] [5].

Learn Phase

The Learn phase represents the knowledge extraction component of the cycle, where data collected during testing is analyzed to generate insights that will inform subsequent design iterations [2]. This phase involves comparing experimental results with initial design objectives, identifying patterns and correlations in the data, and formulating hypotheses about the underlying biological mechanisms governing system behavior [2] [4].

Traditional learning approaches rely on statistical analysis and mechanistic modeling to interpret results. However, the advent of machine learning has dramatically enhanced learning capabilities, enabling researchers to detect complex, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional biological data [4] [5]. Machine learning algorithms can integrate multi-omics datasets (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to build predictive models that map genetic designs to functional outcomes [3] [5]. The knowledge generated in this phase is essential for refining biological designs and developing more accurate predictive models that accelerate convergence toward optimal solutions in successive DBTL cycles [4].

The Evolving DBTL Paradigm: From DBTL to LDBT

Limitations of Traditional DBTL Cycles

Despite its systematic approach, the traditional DBTL framework faces significant challenges that can limit its efficiency and effectiveness. A primary issue is the phenomenon of "DBTL involution," where iterative cycles generate substantial amounts of data and constructs without producing corresponding breakthroughs in system performance [5]. This often occurs because addressing one metabolic bottleneck frequently reveals or creates new limitations elsewhere in the system, leading to diminishing returns from successive engineering cycles [5].

The Build and Test phases typically constitute the most time-consuming and resource-intensive stages of traditional DBTL cycles, creating a practical constraint on how rapidly iterations can be completed [2]. Furthermore, the quality of learning is often limited by the scale and diversity of experimental data generated in each cycle, particularly when working with complex biological systems where the relationship between genetic design and functional output is influenced by numerous interacting factors [4] [5]. These challenges have motivated the development of new approaches that leverage recent technological advances to accelerate and enhance the DBTL process.

The LDBT Paradigm: Learning-First Approach

A transformative shift in the DBTL paradigm has been proposed with the introduction of the LDBT cycle (Learn-Design-Build-Test), which repositions learning at the beginning of the process [2] [6]. This reordering leverages powerful machine learning models that have been pre-trained on vast biological datasets, enabling zero-shot predictions of biological function directly from sequence or structural information without requiring experimental data from previous cycles on the specific system being engineered [2].

In the LDBT framework, the initial Learn phase utilizes protein language models (such as ESM and ProGen) and structure-based design tools (like ProteinMPNN and MutCompute) that have learned evolutionary and biophysical principles from millions of natural protein sequences and structures [2]. These models can generate optimized starting designs that have a higher probability of success, effectively front-loading the learning process and reducing reliance on iterative trial-and-error [2] [6]. The subsequent Design phase then incorporates these computationally generated designs, which are built and tested using high-throughput methods, particularly cell-free expression systems that dramatically accelerate the Build and Test phases [2] [6].

The workflow below illustrates how machine learning and cell-free systems are integrated in the LDBT cycle:

Case Studies and Applications

The LDBT approach has demonstrated significant success across various synthetic biology applications. Researchers have coupled cell-free expression systems with droplet microfluidics and multi-channel fluorescent imaging to screen over 100,000 picoliter-scale reactions in a single experiment, generating massive datasets for training machine learning models [2]. In protein engineering, ultra-high-throughput stability mapping of 776,000 protein variants using cell-free synthesis and cDNA display has provided extensive data for benchmarking computational predictors [2].

Metabolic pathway optimization has particularly benefited from the LDBT framework. The iPROBE (in vitro prototyping and rapid optimization of biosynthetic enzymes) platform uses cell-free systems to test pathway combinations and enzyme expression levels, with neural networks predicting optimal pathway configurations [2]. This approach has successfully improved the production of 3-HB in Clostridium by over 20-fold [2]. Similarly, machine learning guided by cell-free testing has been applied to engineer antimicrobial peptides, with computational surveys of over 500,000 variants leading to the experimental validation of 500 optimal designs and identification of 6 promising antimicrobial peptides [2].

Enabling Technologies and Methodologies

Machine Learning and AI in DBTL

Machine learning (ML) has become a transformative technology across all phases of the DBTL cycle, enabling more predictive and efficient biological design [2] [5]. Different ML approaches offer distinct advantages for various aspects of biological engineering:

Table: Machine Learning Approaches in Biological Engineering

| ML Approach | Applications in DBTL | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Predicting protein function, stability, and solubility from sequence | Prethermut (stability), DeepSol (solubility) [2] |

| Protein Language Models | Zero-shot prediction of functional sequences, mutation effects | ESM, ProGen [2] |

| Structure-Based Models | Designing sequences for target structures, optimizing local environments | ProteinMPNN, MutCompute [2] |

| Generative Models | Creating novel biological sequences with desired properties | Variational Autoencoders (VAE), Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) [3] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Modeling metabolic networks, predicting pathway performance | Graph-based representations of metabolic pathways [3] |

The integration of ML with mechanistic models represents a particularly powerful approach. Physics-informed machine learning combines the predictive power of statistical models with the explanatory strength of physical principles, creating hybrid models that offer both correlation and causation insights [2] [5]. For metabolic engineering, ML models can integrate multi-scale data from enzyme kinetics to bioreactor conditions, enabling more accurate predictions of strain performance in industrial settings [5].

Cell-Free Systems for High-Throughput Testing

Cell-free transcription-translation (TX-TL) systems have emerged as a critical technology for accelerating the Build and Test phases of both DBTL and LDBT cycles [2] [6]. These systems utilize protein biosynthesis machinery from cell lysates or purified components to activate in vitro transcription and translation without the need for living cells [2]. The advantages of cell-free platforms include:

- Speed: Protein production exceeding 1 g/L in less than 4 hours [2]

- Flexibility: Ability to express proteins toxic to living cells and incorporate non-canonical amino acids [2]

- Scalability: Operation across volumes from picoliters to kiloliters [2]

- Control: Precise manipulation of reaction conditions and composition [6]

When combined with liquid handling robots and microfluidics, cell-free systems enable unprecedented throughput in biological testing. The DropAI platform, for instance, leverages droplet microfluidics and multi-channel fluorescent imaging to screen over 100,000 picoliter-scale reactions [2]. This massive parallelization generates the large-scale, high-quality datasets essential for training effective machine learning models in the Learn phase [2].

Automation and Biofoundries

The automation of DBTL cycles through biofoundries represents another critical advancement in synthetic biology [3]. These facilities integrate robotic automation, advanced analytics, and computational infrastructure to execute high-throughput biological design and testing [3]. Biofoundries implement fully automated DBTL workflows that can rapidly iterate through design variants with minimal human intervention, dramatically accelerating the engineering of biological systems [3].

Key components of biofoundries include automated DNA synthesis and assembly systems, robotic liquid handling platforms, high-throughput analytical instruments, and data management systems that track the entire engineering process from design to characterization [3]. The integration of machine learning with automated experimentation enables closed-loop design platforms where AI agents direct experiments, analyze results, and propose new designs in an iterative, self-driving manner [2]. This integration marks a significant step toward fully autonomous biological engineering systems that can systematically explore vast design spaces with minimal human guidance.

Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Workflows

Implementing effective DBTL cycles requires specialized reagents and tools that enable high-throughput construction and characterization of biological systems. The table below outlines essential research reagents and their applications in synthetic biology workflows:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for DBTL Workflows

| Reagent/Tool | Function in DBTL | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free TX-TL Systems | Rapid protein expression without living cells | High-throughput testing of enzyme variants [2] [6] |

| DNA Assembly Kits | Modular construction of genetic circuits | Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly for part standardization [1] |

| Promoter/RBS Libraries | Tunable control of gene expression | Combinatorial optimization of pathway enzyme levels [4] |

| Biosensors | Real-time monitoring of metabolic fluxes | High-throughput screening of metabolite production [3] |

| Protein Stability Assays | Quantifying thermodynamic stability | Screening mutant libraries for improved stability [2] |

| Metabolomics Kits | Comprehensive metabolic profiling | Identifying pathway bottlenecks [3] [5] |

These reagents and tools are particularly powerful when integrated into automated workflows within biofoundries, where they enable the systematic exploration of biological design space [3]. The standardization of these components through initiatives such as the Synthetic Biology Open Language (SBOL) facilitates reproducibility and sharing of designs across different research groups and platforms [3].

Quantitative Framework for DBTL Implementation

Effective implementation of DBTL cycles requires careful consideration of strategic parameters that influence both the efficiency and success of biological engineering projects. Research using simulated DBTL cycles based on mechanistic kinetic models has provided quantitative insights into how these parameters affect outcomes:

Table: Strategic Parameters for Optimizing DBTL Cycles

| Parameter | Impact on DBTL Efficiency | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle Number | Diminishing returns after 3-4 cycles | Plan for 2-4 cycles based on project complexity [4] |

| Strains per Cycle | Larger initial cycles improve model accuracy | Favor larger initial DBTL cycle when total strain count is limited [4] |

| Library Diversity | Reduces bias in machine learning predictions | Maximize sequence space coverage in initial library [4] |

| Experimental Noise | Affects model training and recommendation accuracy | Implement replicates and quality controls [4] |

| Feature Selection | Critical for predictive model performance | Include enzyme kinetics, expression levels, host constraints [5] |

Simulation studies have demonstrated that gradient boosting and random forest models outperform other machine learning methods in the low-data regime typical of early DBTL cycles, showing robustness to training set biases and experimental noise [4]. When the total number of strains that can be built is constrained, starting with a larger initial DBTL cycle followed by smaller subsequent cycles is more effective than distributing the same number of strains equally across cycles [4].

The workflow below illustrates how these strategic parameters are integrated in a simulated DBTL framework for metabolic pathway optimization:

The DBTL framework continues to evolve toward increasingly integrated and automated implementations. The emergence of the LDBT paradigm represents a significant shift from empirical iteration toward predictive engineering, potentially moving synthetic biology closer to a "Design-Build-Work" model similar to more established engineering disciplines [2]. Future developments will likely focus on several key areas:

First, the integration of multi-omics datasets (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) into machine learning models will enhance their predictive power by capturing dynamic cellular contexts in addition to static sequence information [6]. Second, the development of more sophisticated knowledge mining approaches will help structure the vast information contained in scientific literature into computable formats that can inform biological design [5]. Finally, advances in automation and microfluidics will further accelerate the Build and Test phases, potentially enabling fully autonomous self-driving laboratories for biological discovery [2] [6].

In conclusion, the DBTL cycle provides a powerful conceptual and practical framework for engineering biological systems. While traditional DBTL approaches have proven effective, the integration of machine learning and advanced experimental platforms like cell-free systems is transforming this paradigm into a more efficient and predictive process. As these technologies mature, they promise to accelerate the design of biological systems for applications ranging from therapeutic development to sustainable manufacturing, ultimately expanding our ability to program biological function for human benefit.

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a foundational framework in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, providing a systematic, iterative process for engineering biological systems. This cyclical approach enables researchers to bioengineer cells for synthesizing novel valuable molecules, from renewable biofuels to anticancer drugs, with increasing efficiency and predictability [7]. The cycle's power lies in its recursive nature; it is extremely rare for an initial design to behave as desired, and the DBTL loop allows for continuous refinement until the desired specifications—such as a particular titer, rate, or yield—are achieved [7]. The adoption of this framework represents a shift away from ad-hoc engineering practices toward more predictable, principle-based bioengineering, significantly accelerating development timelines that traditionally required hundreds of person-years of effort for commercial products [7].

Recent advancements are reshaping traditional DBTL implementations. The integration of machine learning (ML) and automation is transforming the cycle's dynamics, with some proponents even suggesting a reordering to "LDBT" (Learn-Design-Build-Test), where machine learning algorithms pre-loaded with biological data precede and inform the initial design phase [2]. Furthermore, the use of cell-free expression systems and automated biofoundries is dramatically accelerating the Build and Test phases, enabling megascale data generation that fuels more sophisticated models [2]. These technological evolutions are bringing synthetic biology closer to a "Design-Build-Work" model similar to more established engineering disciplines like civil engineering, though the field still largely relies on empirical iteration rather than purely predictive engineering [2].

The Design Phase

Objectives and Strategic Planning

The primary objective of the Design phase is to define the genetic blueprint for a biological system expected to meet desired specifications. This phase establishes the foundational plan that guides all subsequent experimental work, transforming a biological objective into a detailed, implementable genetic design. Researchers define the system's architecture, select appropriate biological parts, and plan their organization to achieve a desired function, such as producing a target compound or sensing an environmental signal [2]. The Design phase relies heavily on domain knowledge, expertise, and computational modeling, with recent advances incorporating machine learning to enhance predictive capabilities [2].

A significant strategic consideration in the Design phase is the choice between rational design and empirical approaches. Traditional DBTL cycles often begin without prior knowledge, potentially leading to multiple iterations and extensive resource consumption [8]. To address this limitation, knowledge-driven approaches are gaining traction, where upstream in vitro investigations provide mechanistic understanding before full DBTL cycling begins [8]. This approach leverages computational tools and preliminary data to make more informed initial designs, reducing the number of cycles needed to achieve optimal performance.

Key Activities and Methodologies

The Design phase encompasses multiple specialized activities that collectively produce a complete genetic design specification:

Protein Design: Researchers select natural enzymes or design novel proteins to perform required biochemical functions. This may involve enzyme engineering for improved catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, or stability under desired conditions [9].

Genetic Design: This core activity involves translating amino acid sequences into coding DNA sequences (CDS), designing regulatory elements such as ribosome binding sites (RBS), and planning operon architecture for multi-gene pathways [9]. For example, in a dopamine production strain, researchers designed a bicistronic system containing genes for 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase (HpaBC) and L-DOPA decarboxylase (Ddc) to convert L-tyrosine to dopamine [8].

Assembly Design: This critical step involves breaking down plasmids into fragments and planning their assembly, considering factors such as restriction enzyme sites, overhang sequences, and GC content [9]. Tools like TeselaGen's platform can automatically generate detailed DNA assembly protocols tailored to specific project needs, selecting appropriate cloning methods (e.g., Gibson assembly or Golden Gate cloning) and strategically arranging DNA fragments in assembly reactions [9].

Assay Design: Researchers establish biochemical reaction conditions and analytical methods that will be used to test the constructed systems in subsequent phases [9].

Experimental Protocols for In Silico Design

Protocol 1: Computational Pathway Design Using BioCAD Tools

- Define Objective: Specify target compound and preferred host chassis (e.g., E. coli, yeast).

- Pathway Retrieval: Search databases (e.g., KEGG, MetaCyc) for biosynthetic pathways to target compound.

- Enzyme Selection: Identify candidate enzymes for each pathway step, considering kinetics, expression compatibility, and intellectual property.

- Codon Optimization: Optimize coding sequences for expression in host chassis using algorithms that consider codon usage bias, mRNA secondary structure, and GC content.

- Regulatory Element Design: Incorporate appropriate promoters, RBS sequences, and terminators using computational tools like the UTR Designer for modulating RBS sequences [8].

- Compatibility Checking: Verify that all genetic parts work harmoniously without unexpected interactions.

Protocol 2: Knowledge-Driven Design with Upstream In Vitro Testing

- In Vitro Prototyping: Express pathway enzymes in cell-free transcription-translation systems to rapidly assess functionality without host constraints [8].

- Enzyme Ratio Optimization: Test different relative expression levels in crude cell lysate systems to determine optimal stoichiometries [8].

- Pathway Balancing: Use in vitro results to inform initial genetic designs for in vivo implementation, translating optimal enzyme ratios to appropriate RBS strengths and promoter activities [8].

The Build Phase

Objectives and Quality Assurance

The Build phase focuses on the physical construction of the biological system designed in the previous phase, with the primary objective of accurately assembling DNA constructs and introducing them into the target host organism or expression system. Precision is paramount in this phase, as even minor errors in assembly can lead to significant deviations in the final system's behavior [9]. The Build phase has been dramatically accelerated by automation technologies that enable high-throughput construction of genetic variants, facilitating more comprehensive exploration of the design space than manual methods would permit.

A key quality consideration in the Build phase is the verification of constructed strains. After DNA assembly, constructs are typically cloned into expression vectors and verified with colony qPCR or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), though in some high-throughput workflows this verification step may be optional to increase speed [1]. The Build phase also encompasses the preparation of necessary reagents and host strains, ensuring that all components are available for the subsequent Test phase. Modern biofoundries integrate these steps into seamless automated workflows that track samples and reagents throughout the process, maintaining chain of custody and reducing opportunities for human error [9].

Key Activities and Methodologies

The Build phase involves both molecular biology techniques and robust inventory management:

DNA Construct Assembly: Using synthetic biology methods such as Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate cloning, or PCR-based techniques to assemble genetic parts into complete expression constructs [9]. Automated liquid handlers from companies like Labcyte, Tecan, Beckman Coulter, and Hamilton Robotics provide high-precision pipetting for PCR setup, DNA normalization, and plasmid preparation [9].

Strain Transformation: Introducing assembled DNA into microbial chassis (e.g., E. coli, yeast) through transformation or transfection methods appropriate for the host organism.

Library Generation: Creating diverse variant libraries for screening, often through RBS engineering [8], promoter swapping, or targeted mutagenesis. For example, in developing a dopamine production strain, researchers used high-throughput RBS engineering to fine-tune the expression levels of HpaBC and Ddc enzymes [8].

Inventory Management: Tracking DNA parts, strains, and reagents using laboratory information management systems (LIMS) to ensure reproducibility and efficient resource utilization [9]. Platforms like TeselaGen integrate with DNA synthesis providers (e.g., Twist Bioscience, IDT, GenScript) to streamline the flow of custom DNA sequences into lab workflows [9].

Experimental Protocols for Genetic Construction

Protocol 1: High-Throughput DNA Assembly Using Automated Liquid Handling

- Reaction Setup: Program liquid handlers to dispense DNA fragments, assembly master mix, and water into microtiter plates.

- Assembly Reaction: Incubate plates at appropriate temperature and duration for the selected assembly method (e.g., 50°C for 60 minutes for Gibson Assembly).

- Transformation: Transfer assembly reactions to competent cells using heat shock or electroporation methods.

- Outgrowth: Add recovery medium and incubate with shaking to allow expression of antibiotic resistance markers.

- Plating: Spread transformations on selective agar plates containing appropriate antibiotics.

- Colony Picking: Isolate individual colonies using automated colony pickers for subsequent verification and testing.

Protocol 2: RBS Library Construction for Pathway Optimization

- SD Sequence Design: Design variant Shine-Dalgarno sequences with different GC content to modulate translation initiation rates without altering secondary structures [8].

- Oligonucleotide Synthesis: Synthesize forward and reverse primers containing the variant RBS sequences.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify target genes using RBS-variant primers to generate a library of constructs with different translation initiation rates.

- Assembly and Cloning: Clone the variant library into expression vectors using high-throughput methods.

- Sequence Verification: Verify a subset of clones by Sanger sequencing or NGS to confirm library diversity and sequence accuracy.

The Test Phase

Objectives and Performance Metrics

The Test phase serves the critical function of experimentally characterizing the biological systems built in the previous phase to determine whether they perform as designed. This phase provides the essential empirical data that fuels the entire DBTL cycle, enabling researchers to evaluate design success, identify limitations, and generate insights for subsequent iterations. The core objective is to measure system performance against predefined metrics, which typically include titer (concentration), rate (productivity), and yield (conversion efficiency) of the desired product, as well as host fitness and other relevant phenotypic characteristics [7].

Modern Test phases increasingly leverage high-throughput screening (HTS) technologies to rapidly characterize large variant libraries. Automation has been pivotal in enhancing the speed and efficiency of sample analysis, with automated liquid handling systems, plate readers, and robotics enabling the testing of thousands of constructs in parallel [9]. The choice of testing platform—whether in vivo chassis (bacteria, yeast, mammalian cells) or in vitro cell-free systems—represents a key strategic decision. Cell-free expression platforms are particularly valuable for high-throughput testing as they allow direct measurement of enzyme activities without cellular barriers, enable production of toxic compounds, and provide a highly controllable environment for systematic characterization [2].

Key Activities and Methodologies

The Test phase integrates sample preparation, analytical measurement, and data management:

Cultivation and Sample Preparation: Growing engineered strains under defined conditions and preparing samples for analysis. For metabolic engineering projects, this often involves cultivation in minimal media with precise control of nutrients, inducers, and environmental conditions [8].

High-Throughput Analytical Measurement: Using automated systems to quantify strain performance and product formation. Platforms like the EnVision Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer) and BioTek Synergy HTX Multi-Mode Reader efficiently assess diverse assay formats [9].

Omics Technologies: Applying large-scale analytical methods for comprehensive system characterization. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) provide genotypic analysis, while automated mass spectrometry setups (e.g., Thermo Fisher Orbitrap) enable proteomic and metabolomic profiling [9].

Data Collection and Integration: Systematically capturing experimental results and linking them to design parameters. Platforms like TeselaGen act as centralized hubs, collecting data from various analytical equipment and integrating it with the design-build process [9].

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Metabolic Pathway Variants

- Cultivation: Inoculate variant strains in deep-well plates containing defined minimal medium with appropriate carbon sources and inducers [8].

- Growth Monitoring: Measure optical density (OD600) at regular intervals to track growth kinetics using plate readers.

- Metabolite Extraction: At appropriate growth phase, extract intracellular and extracellular metabolites using quenching solutions and appropriate extraction solvents.

- Product Quantification: Analyze samples using HPLC, GC-MS, or LC-MS to quantify target compounds and potential byproducts.

- Data Processing: Convert raw analytical data into standardized formats for comparative analysis and modeling.

Protocol 2: Cell-Free Testing for Rapid Characterization

- Lysate Preparation: Prepare crude cell lysates from production host by cell disruption and centrifugation to remove debris [8].

- Reaction Setup: Combine cell-free extracts with DNA templates, substrates, cofactors, and energy regeneration systems in microtiter plates.

- Incubation and Monitoring: Incubate reactions at controlled temperature while monitoring substrate consumption and product formation in real-time where possible.

- Reaction Quenching: Stop reactions at appropriate timepoints using acid, base, or heat denaturation.

- Product Analysis: Quantify reaction products using colorimetric assays, fluorescence detection, or mass spectrometry.

Table 1: Key Analytical Methods in the Test Phase

| Method | Application | Throughput | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plate Readers | Growth curves, fluorescent reporters, colorimetric assays | High | OD600, fluorescence intensity, absorbance |

| HPLC/UPLC | Separation and quantification of metabolites | Medium | Retention time, peak area, concentration |

| GC-MS/LC-MS | Identification and quantification of volatile/non-volatile compounds | Medium | Mass-to-charge ratio, retention time, fragmentation pattern |

| NGS | Genotype verification, mutation identification | High | Read depth, variant frequency, sequence accuracy |

| Flow Cytometry | Single-cell analysis, population heterogeneity | High | Fluorescence intensity, cell size, granularity |

The Learn Phase

Objectives and Knowledge Integration

The Learn phase represents the critical bridge between empirical testing and improved design, serving to extract meaningful insights from experimental data to inform subsequent DBTL cycles. The primary objective is to analyze the results from the Test phase, identify patterns and relationships, and generate actionable knowledge that will improve future designs. This phase has traditionally been the most weakly supported in the DBTL cycle, but advances in machine learning and data science are dramatically enhancing its power and effectiveness [7]. The Learn phase enables researchers to move beyond simple trial-and-error approaches toward predictive biological design.

A key challenge addressed in the Learn phase is the integration of diverse data types into coherent models. Experimental data in synthetic biology is often sparse, expensive to generate, and multi-dimensional, requiring specialized analytical approaches [7]. The Learn phase also serves to contextualize results within broader biological understanding, determining whether unexpected outcomes stem from design flaws, unanticipated biological interactions, or experimental artifacts. Modern learning approaches increasingly leverage Bayesian methods and ensemble modeling to quantify uncertainty and make robust predictions even with limited data, which is particularly valuable in biological contexts where comprehensive data generation remains challenging [7].

Key Activities and Methodologies

The Learn phase transforms raw data into actionable knowledge through systematic analysis:

Data Integration and Standardization: Combining results from multiple experiments and analytical platforms into unified datasets. TeselaGen's platform provides standardized data handling with automatic dataset validation and integrated data visualization tools [9].

Pattern Recognition and Model Building: Using statistical analysis and machine learning to identify relationships between genetic designs and phenotypic outcomes. For example, the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) combines scikit-learn with Bayesian ensemble approaches to predict biological system behavior [7].

Hypothesis Generation: Formulating new testable hypotheses based on analytical results to guide subsequent design iterations.

Uncertainty Quantification: Assessing confidence in predictions and identifying knowledge gaps that require additional experimentation. ART provides full probability distributions of predictions rather than simple point estimates, enabling principled experimental design [7].

Experimental Protocols for Data Analysis

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Guided Strain Optimization

- Feature Engineering: Identify relevant input variables (e.g., enzyme expression levels, promoter strengths, genetic modifications) that potentially influence the output (e.g., product titer) [7].

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate machine learning algorithms based on dataset size and complexity. For smaller datasets (<100 instances), Bayesian ensemble methods often outperform deep learning approaches [7].

- Model Training: Train predictive models using available experimental data, implementing cross-validation to avoid overfitting.

- Prediction and Recommendation: Use trained models to predict performance of untested genetic designs and recommend the most promising candidates for further testing [7].

- Experimental Validation: Build and test recommended designs to generate new data for model refinement.

Protocol 2: Pathway Performance Analysis

- Multi-omics Data Integration: Combine transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to build comprehensive views of pathway operation.

- Flux Analysis: Calculate metabolic fluxes through different pathway branches to identify bottlenecks or competing reactions.

- Correlation Analysis: Identify relationships between enzyme expression levels, metabolite pools, and final product yields.

- Constraint-Based Modeling: Use genome-scale metabolic models to simulate system behavior under different genetic and environmental conditions.

- Design Revision: Based on analytical insights, propose specific genetic modifications (e.g., RBS tuning, enzyme engineering, gene knockouts) to improve pathway performance.

Table 2: Key Tools and Technologies for the Learn Phase

| Tool/Technology | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) | Predictive modeling for strain engineering | Bayesian ensemble approach, uncertainty quantification, tailored for small datasets [7] |

| TeselaGen Discover Module | Phenotype prediction for biological products | Advanced embeddings for DNA/proteins/compounds, predictive models [9] |

| Pre-trained Protein Language Models (ESM, ProGen) | Protein design and optimization | Zero-shot prediction of beneficial mutations, function inference from sequence [2] |

| Structure-Based Design Tools (ProteinMPNN, MutCompute) | Protein engineering based on structural information | Sequence design for specific backbones, residue-level optimization [2] |

| Stability Prediction Tools (Prethermut, Stability Oracle) | Protein thermostability optimization | ΔΔG prediction for mutations, stability landscape mapping [2] |

Integrated Case Study: Development of a Dopamine Production Strain

Experimental Implementation Across DBTL Phases

A recent study demonstrating the development of an optimized dopamine production strain in E. coli provides a comprehensive example of the DBTL cycle in action, incorporating a knowledge-driven approach with upstream in vitro investigation [8]. This case study illustrates how the four phases integrate in a real metabolic engineering project and highlights the strategic advantage of incorporating mechanistic understanding before full DBTL cycling.

In the Design phase, researchers planned a bicistronic system for dopamine biosynthesis from L-tyrosine, incorporating the native E. coli gene encoding 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase (HpaBC) to convert L-tyrosine to L-DOPA, and L-DOPA decarboxylase (Ddc) from Pseudomonas putida to catalyze dopamine formation [8]. The host strain was engineered for high L-tyrosine production through genomic modifications, including depletion of the transcriptional dual regulator tyrosine repressor TyrR and mutation of the feedback inhibition of chorismate mutase/prephenate dehydrogenase (tyrA) [8].

For the Build phase, researchers implemented RBS engineering to fine-tune the relative expression levels of HpaBC and Ddc. They created variant libraries by modulating the Shine-Dalgarno sequence without interfering with secondary structures, exploiting the relationship between GC content in the SD sequence and RBS strength [8]. This high-throughput approach enabled systematic exploration of the expression space.

In the Test phase, researchers first conducted in vitro experiments using crude cell lysate systems to rapidly assess enzyme expression levels and pathway functionality without host constraints [8]. Following promising in vitro results, they translated these findings to in vivo testing, cultivating strains in minimal medium and quantifying dopamine production using appropriate analytical methods. The optimal strain achieved dopamine production of 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L, equivalent to 34.34 ± 0.59 mg/g biomass [8].

The Learn phase involved analyzing the relationship between RBS sequence features, enzyme expression levels, and final dopamine titers. Researchers discovered that fine-tuning the dopamine pathway through high-throughput RBS engineering clearly demonstrated the impact of GC content in the Shine-Dalgarno sequence on RBS strength [8]. These insights enabled the development of a significantly improved production strain, outperforming previous state-of-the-art in vivo dopamine production by 2.6 and 6.6-fold for different metrics [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DBTL Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example from Case Study |

|---|---|---|

| Crude Cell Lysates | In vitro pathway prototyping and testing | Used for upstream investigation of dopamine pathway enzymes before in vivo implementation [8] |

| RBS Library Variants | Fine-tuning gene expression levels | SD sequence modulation to optimize HpaBC and Ddc expression ratios [8] |

| Minimal Medium | Controlled cultivation conditions | Consisted of glucose, salts, MOPS buffer, trace elements, and selective antibiotics [8] |

| Inducers (e.g., IPTG) | Controlled gene expression induction | Added to liquid medium and agar plates at 1 mM concentration for pathway induction [8] |

| Analytical Standards | Metabolite quantification and method calibration | Dopamine and L-DOPA standards for HPLC or LC-MS quantification |

Visualizing the DBTL Workflow

Diagram 1: The DBTL Cycle Workflow - This diagram illustrates the iterative nature of the Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle in synthetic biology, showing how knowledge gained in each cycle informs subsequent iterations until the desired biological objective is achieved.

Diagram 2: The LDBT Paradigm - This diagram shows the emerging paradigm where Machine Learning (Learn) precedes Design, leveraging large datasets and predictive models to generate more effective initial designs, potentially reducing the number of experimental cycles needed.

The DBTL cycle represents a powerful framework for systematic bioengineering, enabling researchers to navigate the complexity of biological systems through iterative refinement. As synthetic biology continues to mature, advancements in automation, machine learning, and foundational technologies like cell-free systems are transforming each phase of the cycle. The integration of computational and experimental approaches across all four phases—from intelligent design through automated construction, high-throughput testing, and data-driven learning—is accelerating our ability to engineer biological systems for diverse applications in medicine, manufacturing, and environmental sustainability. The continued evolution of the DBTL cycle toward more predictive, first-principles engineering promises to further reduce development timelines and expand the boundaries of biological design.

For years, the engineering of biological systems has been guided by the systematic framework of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle [1]. This iterative process begins with researchers defining objectives and designing biological parts using domain knowledge and computational modeling (Design). The designed DNA constructs are then synthesized and introduced into living chassis or cell-free systems (Build), followed by experimental measurement of performance (Test). Finally, researchers analyze the collected data to inform the next design round (Learn), repeating the cycle until the desired biological function is achieved [2]. This methodology has streamlined efforts to build biological systems by providing a systematic, iterative framework for biological engineering [1].

However, the traditional DBTL approach faces significant limitations. The Build-Test phases often create bottlenecks, requiring time-intensive cloning and cellular culturing steps that can take days or weeks [6]. Furthermore, the high dimensionality and combinatorial nature of DNA sequence variations generate a vast design landscape that is impractical to explore exhaustively through empirical iteration alone [2] [6]. These challenges have prompted a fundamental rethinking of the synthetic biology workflow, especially given recent advancements in artificial intelligence and high-throughput testing platforms.

The Paradigm Shift: Rationale for LDBT

The Machine Learning Revolution

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative force in synthetic biology, enabling a conceptual shift from iteration-heavy experimentation to prediction-driven design [2]. ML models can economically leverage large biological datasets to detect patterns in high-dimensional spaces, enabling more efficient and scalable design than traditional computational models, which are often computationally expensive and limited in scope when applied to biomolecular complexity [2].

Table 1: Key Machine Learning Approaches in the LDBT Paradigm

| ML Approach | Key Functionality | Representative Tools | Applications in Synthetic Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models | Capture evolutionary relationships in protein sequences; predict beneficial mutations | ESM [2], ProGen [2] | Zero-shot prediction of antibody sequences; designing libraries for engineering biocatalysts [2] |

| Structure-Based Models | Predict sequences that fold into specific backbones; optimize residues given local environment | ProteinMPNN [2], MutCompute [2], AlphaFold [2] | Design of stabilized hydrolases for PET depolymerization; TEV protease variants with improved activity [2] |

| Functional Prediction Models | Predict protein properties like thermostability and solubility | Prethermut [2], Stability Oracle [2], DeepSol [2] | Eliminating destabilizing mutations; identifying stabilizing substitutions; predicting protein solubility [2] |

| Hybrid & Augmented Models | Combine evolutionary information with biophysical principles | Physics-informed ML [2], Force-field augmented models [2] | Exploring evolutionary landscapes of enzymes; mapping sequence-fitness landscapes [2] |

The predictive power of these ML approaches has advanced to the point where zero-shot predictions (made without additional training) can generate functional biological designs from the outset [2]. For instance, protein language models trained on millions of sequences can predict beneficial mutations and infer protein functions, while structure-based models like ProteinMPNN can design sequences that fold into desired structures with dramatically improved success rates [2].

The Rise of Cell-Free Testing Platforms

Complementing the ML revolution, cell-free transcription-translation (TX-TL) systems have emerged as a powerful experimental platform that circumvents the bottlenecks of traditional in vivo testing [2] [6]. These systems leverage protein biosynthesis machinery from cell lysates or purified components to activate in vitro transcription and translation, enabling direct use of synthesized DNA templates without time-consuming cloning steps [2].

The advantages of cell-free systems are numerous: they are rapid (producing >1 g/L of protein in <4 hours), scalable (from picoliters to kiloliters), capable of producing toxic products, and amenable to high-throughput screening through integration with liquid handling robots and microfluidics [2]. This enables researchers to test thousands to hundreds of thousands of variants in picoliter-scale reactions, generating the massive datasets needed to train and validate ML models [2] [6].

The LDBT Framework: A Technical Examination

Core Architecture and Workflow

The LDBT cycle represents a fundamental reordering of the synthetic biology workflow. It begins with the Learn phase, where machine learning models pre-trained on vast biological datasets generate initial designs [2] [6]. This is followed by Design, where researchers use these computational predictions to specify biological parts with enhanced likelihood of functionality. The Build phase employs cell-free systems for rapid synthesis, while Test utilizes high-throughput cell-free assays for experimental validation [2] [6].

Diagram 1: The LDBT workflow begins with Learning, where pre-trained models inform the Design of biological parts, which are rapidly Built and Tested using cell-free systems, generating data that can further refine models.

This reordering creates a more efficient pipeline that reduces dependency on labor-intensive cloning and cellular culturing steps, potentially democratizing synthetic biology research for smaller labs and startups [6]. The integration of computational intelligence with experimental ingenuity sets the stage for transforming how biological systems are understood, designed, and deployed [6].

Quantitative Comparison: DBTL vs. LDBT

Table 2: Systematic Comparison of DBTL and LDBT Approaches

| Parameter | Traditional DBTL Cycle | LDBT Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Phase | Design based on domain knowledge and existing data [2] | Learn using pre-trained machine learning models [2] |

| Build Methodology | In vivo chassis (bacteria, yeast, mammalian cells) [2] | Cell-free expression systems [2] [6] |

| Build Timeline | Days to weeks (including cloning) [6] | Hours (direct DNA template use) [2] |

| Testing Throughput | Limited by cellular growth and transformation efficiency [6] | Ultra-high-throughput (100,000+ reactions) [2] |

| Primary Learning Source | Experimental data from previous cycles [2] | Foundational models trained on evolutionary and structural data [2] |

| Key Advantage | Systematic, established framework [1] | Speed, scalability, and predictive power [2] [6] |

| Experimental Readout | Product formation, -omics analyses [10] | Growth-coupled selection or direct functional assays [10] |

Implementation Protocols

Machine Learning-Guided Design Protocol

For implementing the Learn phase, researchers can utilize the following protocol:

Model Selection: Choose appropriate pre-trained models based on the engineering goal:

- For sequence-based design: Employ protein language models (ESM, ProGen) to generate sequences with desired evolutionary properties [2].

- For structure-based design: Utilize ProteinMPNN or MutCompute to design sequences folding into specific structures or optimizing local environments [2].

- For property optimization: Apply specialized predictors (Prethermut, DeepSol) for thermostability or solubility enhancement [2].

Zero-Shot Prediction: Generate initial designs without additional training, leveraging patterns learned from vast datasets during pre-training [2].

Library Design: Select optimal variants from computational surveys for experimental testing. For example, in antimicrobial peptide engineering, researchers computationally surveyed over 500,000 candidates before selecting 500 optimal variants for experimental validation [2].

Cell-Free Build-Test Protocol

The Build-Test phases in LDBT utilize cell-free systems through this standardized protocol:

DNA Template Preparation:

- Use linear DNA templates or plasmid DNA synthesized based on ML-designed sequences

- No requirement for cloning or transformation into living cells [2]

Cell-Free Reaction Assembly:

High-Throughput Testing:

Data Generation and Model Refinement:

- Collect functional data for thousands to hundreds of thousands of variants

- Use results to validate computational predictions and refine ML models [2]

Research Reagent Solutions for LDBT Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for LDBT Workflows

| Reagent/Platform | Function in LDBT | Key Features | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free TX-TL Systems | Rapid protein synthesis without living cells | >1 g/L protein in <4 hours; scalable from pL to kL; amenable to high-throughput automation [2] | Pathway prototyping; toxic protein production; enzyme engineering [2] |

| Droplet Microfluidics | Ultra-high-throughput screening | Enables screening of >100,000 picoliter-scale reactions; multi-channel fluorescent imaging [2] | Protein stability mapping; enzyme variant screening [2] |

| Protein Language Models (ESM, ProGen) | Zero-shot protein design | Trained on millions of protein sequences; captures evolutionary relationships [2] | Predicting beneficial mutations; designing libraries for biocatalyst engineering [2] |

| Structure-Based Design Tools (ProteinMPNN, MutCompute) | Sequence design based on structural constraints | Predicts sequences folding into specific backbones; optimizes residues for local environment [2] | Engineering stabilized hydrolases; designing proteases with improved activity [2] |

| cDNA Display Platforms | Protein stability mapping | Allows ΔG calculations for hundreds of thousands of protein variants [2] | Benchmarking zero-shot predictors; large-scale stability datasets [2] |

Case Studies and Experimental Evidence

Enzyme Engineering with Zero-Shot Predictions

The power of the LDBT approach is exemplified by engineering a hydrolase for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) depolymerization. Researchers used MutCompute, a deep neural network trained on protein structures, to identify stabilizing mutations based on local chemical environments [2]. The resulting variants exhibited increased stability and activity compared to wild-type, demonstrating successful zero-shot engineering without iterative optimization [2]. This approach was further enhanced by combining large language models trained on PET hydrolase homologs with force-field-based algorithms, essentially exploring the evolutionary landscape computationally before testing [2].

Ultra-High-Throughput Protein Stability Mapping

In a groundbreaking study, researchers coupled cell-free protein synthesis with cDNA display to map the stability of 776,000 protein variants in a single experimental campaign [2]. This massive dataset provided unprecedented benchmarking for zero-shot predictors and demonstrated how cell-free systems can generate the megascale data required for training and validating sophisticated ML models [2]. The integration of such extensive experimental data with computational prediction represents the core strength of the LDBT paradigm.

Antimicrobial Peptide Design

The LDBT framework enabled researchers to computationally survey over 500,000 antimicrobial peptide sequences using deep learning models, from which they selected 500 optimal variants for experimental validation in cell-free systems [2]. This approach identified 6 promising antimicrobial peptide designs with high efficacy, showcasing how ML-guided filtering can dramatically reduce the experimental burden while maintaining success rates [2].

Pathway Engineering with iPROBE

The in vitro prototyping and rapid optimization of biosynthetic enzymes (iPROBE) platform uses cell-free systems to test pathway combinations and enzyme expression levels, then applies neural networks to predict optimal pathway sets [2]. This approach successfully improved 3-HB production in Clostridium by over 20-fold, demonstrating the power of combining cell-free prototyping with machine learning for metabolic pathway engineering [2].

Comparative Workflow Visualization

Diagram 2: Comparison of traditional DBTL, an iterative cycle beginning with Design, versus the LDBT paradigm, a more linear workflow that begins with Learning through machine learning.

The transition from DBTL to LDBT represents more than just a conceptual reshuffling—it signals a fundamental shift in how biological engineering is approached. By placing Learning at the forefront and leveraging cell-free platforms for rapid validation, the LDBT framework promises to accelerate biological design, optimize resource usage, and unlock novel applications with greater predictability and speed [6].

This paradigm shift brings synthetic biology closer to a "Design-Build-Work" model that relies on first principles, similar to established engineering disciplines like civil engineering [2]. Such a transition could have transformative impacts on efforts to engineer biological systems and help reshape the bioeconomy [2].

Future advancements will likely focus on expanding the capabilities of both computational and experimental components. For ML, this includes developing more accurate foundational models trained on even larger datasets, incorporating multi-omics information, and improving the integration of physical principles with statistical learning [2] [6]. For cell-free systems, priorities include reducing costs, increasing scalability, and enhancing the fidelity of in vitro conditions to match in vivo environments [2].

As the field progresses, the LDBT approach is poised to dramatically compress development timelines for bio-based products, from pharmaceuticals to sustainable chemicals, potentially reducing what once took months or years to a matter of days [6]. This accelerated pace of biological design and discovery promises to open new frontiers in biotechnology and synthetic biology, driven by the powerful convergence of machine intelligence and experimental innovation.

The engineering of biological systems relies on a structured iterative process known as the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle. This framework allows researchers to systematically develop and optimize biological systems, such as engineered organisms for producing biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and other valuable compounds [1]. As synthetic biology advances, efficient procedures are being developed to streamline the transition from conceptual design to functional biological product. Computer-aided design (CAD) has become a necessary component in this pipeline, serving as a critical bridge between biological understanding and engineering application [11]. This technical guide examines the essential tools and technologies supporting each phase of the DBTL cycle, with particular focus on CAD platforms and emerging cell-free systems that are accelerating progress in synthetic biology.

The DBTL Cycle in Synthetic Biology

The DBTL cycle represents a systematic framework for engineering biological systems. In the Design phase, researchers use computational tools to model and simulate biological networks. The Build phase involves the physical assembly of genetic constructs, often leveraging high-throughput automated workflows. During the Test phase, these constructs are experimentally evaluated through functional assays. Finally, the Learn phase involves analyzing the resulting data to refine designs and inform the next iteration of the cycle [1]. This iterative process continues until a construct producing the desired function is obtained.

Table 1: Core Activities and Outputs in the DBTL Cycle

| Phase | Primary Activities | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Network modeling, parts selection, simulation | Biological model, DNA design specification |

| Build | DNA assembly, cloning, transformation | Genetic constructs, engineered strains |

| Test | Functional assays, characterization | Performance data, quantitative measurements |

| Learn | Data analysis, model refinement | Design rules, improved constructs for next cycle |

Phase 1: Design Tools and Technologies

Computer-Aided Design (CAD) Platforms

CAD applications provide essential features for designing biological systems, including building and simulating networks, analyzing robustness, and searching databases for components that meet design criteria [12]. TinkerCell represents a prominent example of a modular CAD tool specifically developed for synthetic biology applications. Its flexible modeling framework allows it to accommodate evolving methodologies in the field, from how parts are characterized to how synthetic networks are modeled and analyzed computationally [12] [11].

TinkerCell employs a component-based modeling approach where users build biological networks by selecting and connecting components from a parts catalog. The software uses an underlying ontology that understands biological relationships - for example, it recognizes that "transcriptional repression" is a connection from a "transcription factor" to a "repressible promoter" [11]. This biological understanding enables TinkerCell to automatically derive appropriate dynamics and rate equations when users connect biological components, significantly streamlining the model creation process.

Key Features of Modern Biological CAD Tools

Flexible Modeling Framework: TinkerCell does not enforce a single modeling methodology, recognizing that best practices are still evolving in synthetic biology. This allows researchers to test different computational methods relevant to their specific applications [12] [11].

Extensibility: The platform readily accepts third-party algorithms, allowing it to serve as a testing platform for different synthetic biology methods. Custom programs can be integrated to perform specialized analyses and even interact with TinkerCell's visual interface [12] [11].

Support for Uncertainty: Biological parameters often have significant uncertainties. TinkerCell allows parameters to be defined as ranges or distributions rather than single values, though analytical functions leveraging this capability are still under development [11].

Module Reuse: Supporting engineering principles of abstraction and modularity, TinkerCell allows researchers to construct larger circuits by connecting previously validated smaller circuits, with options to hide internal details for simplified viewing [11].

Automated Workflow Platforms

The Galaxy-SynBioCAD portal represents an emerging class of integrated workflow platforms that provide end-to-end solutions for metabolic pathway design and engineering [13]. This web-based platform incorporates tools for:

- Retrosynthesis: Identifying pathways to synthesize target compounds in chassis organisms using tools like RetroPath2.0 and RP2Paths

- Pathway Evaluation: Ranking pathways based on multiple criteria including thermodynamics, predicted yield, and host compatibility

- Genetic Design: Designing DNA constructs with appropriate regulatory elements and formatting them for automated assembly

These tools use standard exchange formats like SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) and SBOL (Synthetic Biology Open Language) to ensure interoperability between different stages of the design process [13].

Phase 2: Build Tools and Technologies

DNA Assembly and Automated Workflows

The Build phase transforms designed genetic circuits into physical DNA constructs. Automation is critical for increasing throughput and reducing the time, labor, and cost of generating multiple construct variants [1]. Modern synthetic biology workflows employ:

- Standardized Assembly Methods: Double-stranded DNA fragments are designed for easy gene construction, often using standardized assembly protocols like Golden Gate or Gibson Assembly

- Automated Liquid Handling: Robotic workstations enable high-throughput assembly of genetic constructs, with platforms like Aquarium and Antha providing instructions for either manual or automated execution of assembly protocols [13]

- Quality Control Verification: Assembled constructs are typically verified using colony qPCR or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), though this step may be optional in some high-throughput workflows [1]

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Synthetic Biology

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Parts/Libraries | Basic genetic components for circuit construction | Promoters, RBS, coding sequences, terminators |

| Assembly Reagents | Enzymatic assembly of genetic constructs | Restriction enzymes, ligases, polymerase |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | In vitro testing and prototyping | E. coli extracts, wheat germ extracts, PURE system |

| Chassis Strains | Host organisms for circuit implementation | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, specialized production strains |

| Selection Markers | Identification of successful transformants | Antibiotic resistance, auxotrophic markers |

High-Throughput Strain Engineering

The DBTL approach enables development of large, diverse libraries of biological strains. This requires robust, repeatable molecular cloning workflows to increase productivity of target molecules including nucleotides, proteins, and metabolites [1]. Automated platforms from companies like Culture Biosciences provide cloud-based bioreactor systems that enable scientists to design, run, monitor, and analyze experiments remotely, significantly reducing R&D timelines [14].

Phase 3: Test Tools and Technologies

Cell-Free Systems for Rapid Prototyping

Cell-free systems (CFS) have emerged as powerful platforms for testing synthetic biological systems without the constraints of living cells [15]. These systems consist of molecular machinery extracted from cells, typically containing enzymes necessary for transcription and translation, allowing them to perform central dogma processes (DNA→RNA→protein) independent of a cell [15].

CFS can be derived from various sources, each with distinct advantages:

Table 3: Comparison of Major Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Platforms

| Platform | Advantages | Disadvantages | Representative Yields | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PURE System | Defined composition, flexible, minimal nucleases/proteases | Expensive, cannot activate endogenous metabolism | GFP: 380 μg/mL [16] | Minimal cells, complex proteins, unnatural amino acids |

| E. coli Extract | High yields, low-cost, genetically tractable | Limited post-translational modifications | GFP: 2300 μg/mL [16] | High-throughput prototyping, antibodies, vaccines, diagnostics |

| Wheat Germ Extract | Excellent for eukaryotic proteins, long reaction duration | Labor-intensive preparation | GFP: 1600-9700 μg/mL [16] | Eukaryotic membrane proteins, structural biology |

| Insect Cell Extract | Capable of complex PTMs including glycosylation | Lower yields, requires more extract | Not specified | Eukaryotic proteins requiring modifications |

Key Advantages of Cell-Free Testing Systems

- Rapid Prototyping: Genetic instructions can be added directly to CFS at desired concentrations and stoichiometries using linear or circular DNA formats, bypassing the need for cloning and cellular transformation [15].

- Biosafety: CFS can be made sterile via filtration and are inherently biosafe as they lack self-replicating capacity, enabling deployment outside laboratory settings [15].

- Precise Control: The open nature of CFS allows direct manipulation of reaction conditions and addition of supplements that might not cross cellular membranes [16].

- Material Stability: Freeze-dried cell-free (FD-CF) systems remain active for at least a year without refrigeration, enabling room temperature storage and distribution [15].

Applications in Biosensing and Diagnostics

CFS have enabled development of field-deployable diagnostic tools. For example, paper-based FD-CF systems embedded with synthetic gene networks have been used for detection of pathogens like Zika virus at clinically relevant concentrations with single-base-pair resolution for strain discrimination [15]. These systems can be activated simply by adding water, making them practical for use in resource-limited settings.

Phase 4: Learn Tools and Technologies

Data Analysis and Machine Learning

The Learn phase focuses on extracting meaningful insights from experimental data to inform subsequent design cycles. Key computational approaches include:

- Pathway Scoring and Ranking: Tools like rpThermo (for thermodynamic analysis) and rpFBA (for flux balance analysis) enable quantitative evaluation of pathway performance [13]

- Machine Learning Optimization: Algorithms can be trained on experimental data to predict optimal genetic designs, reducing the number of iterations needed in the DBTL cycle [16]

- Multi-parameter Analysis: Integrated platforms like Galaxy-SynBioCAD combine multiple ranking criteria including pathway length, predicted yield, host compatibility, and metabolite toxicity [13]

Integrated Workflow Platforms

The Galaxy-SynBioCAD portal exemplifies the trend toward integrated learning environments, where tools for design, analysis, and data interpretation are combined in interoperable workflows [13]. These platforms enable researchers to:

- Chain together specialized tools using standard file formats

- Compare predicted versus actual performance across multiple design iterations

- Extract design rules from successful and failed constructs

- Share and reproduce computational experiments across research groups

Integrated Case Study: Lycopene-Production Pathway Optimization

A multi-site study demonstrated the power of integrated DBTL workflows using the Galaxy-SynBioCAD platform to engineer E. coli strains for lycopene production [13]. The study implemented:

- Pathway Design: Retrosynthesis tools identified multiple pathway variants connecting host metabolites to lycopene

- Construct Design: DNA assembly designs were automatically generated with variations in promoter strength, RBS sequences, and gene ordering

- Automated Building: Scripts driving liquid handlers were generated for high-throughput plasmid assembly and transformation

- Performance Testing: Lycopene production was measured across the strain library

- Learning: Successful designs were analyzed to extract principles for future optimizations

This integrated approach achieved an 83% success rate in retrieving validated pathways among the top 10 pathways generated by the computational workflows [13].

Future Directions

The integration of CAD tools with cell-free systems and automated workflows is poised to further accelerate synthetic biology applications. Emerging trends include:

- AI-Driven Design: Companies like Ginkgo Bioworks and Ligo Biosciences are leveraging generative AI models to design novel biological systems, from optimized enzymes to complete metabolic pathways [14]

- Expanded Cell-Free Applications: CFS are being applied to increasingly complex challenges, including natural product biosynthesis where they enable rapid prototyping of biosynthetic pathways and production of novel compounds [17]

- Industrial Scale-Up: Cell-free protein synthesis is transitioning to industrial scales, with demonstrations reaching 100-1000 liter reactions for therapeutic production [15] [16]

The synthetic biology toolkit has evolved dramatically, with CAD platforms like TinkerCell providing flexible design environments and cell-free systems enabling rapid testing and prototyping. The integration of these technologies into automated DBTL workflows, as exemplified by platforms like Galaxy-SynBioCAD, is reducing development timelines and increasing the predictability of biological engineering. As these tools continue to mature and integrate AI-driven design capabilities, they promise to accelerate the transformation of synthetic biology from specialized research to a reliable engineering discipline capable of addressing diverse challenges in medicine, manufacturing, and environmental sustainability.

From Code to Cell: Implementing and Automating the DBTL Workflow

Streamlining the Build Phase with High-Throughput DNA Assembly and Automated Liquid Handling

In the synthetic biology framework of Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL), the Build phase is a critical gateway where digital designs become physical biological constructs. This stage, which involves the synthesis and assembly of DNA sequences, has traditionally been a significant bottleneck in research and development cycles. The integration of high-throughput DNA assembly methods with automated liquid handling robotics transforms this bottleneck into a rapid, reproducible, and scalable process. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastering this integration is essential for accelerating the development of novel therapeutics, diagnostic tools, and sustainable bioproduction platforms. This technical guide details the core methodologies, instrumentation, and protocols that enable this streamlined Build phase.

The Build Phase within the DBTL Cycle

The DBTL cycle is a systematic framework for engineering biological systems [1] [18]. Within this cycle, the Build phase is the physical implementation of a genetic design.

- Design: Researchers define objectives and create a blueprint using genetic parts (promoters, coding sequences, etc.) [18].

- Build: This phase translates the digital blueprint into physical DNA constructs. It involves DNA synthesis, assembly into plasmids or other vectors, and transformation into a host organism [2] [18].

- Test: The engineered constructs are experimentally characterized to measure performance and function [18].

- Learn: Data from the Test phase are analyzed to inform the next Design round, creating an iterative optimization loop [1] [18].

Automating the Build phase is crucial for increasing throughput, enhancing reproducibility, and enabling the construction of large, diverse libraries necessary for comprehensive screening and optimization [19] [1]. The following diagram illustrates the DBTL cycle and the integration of high-throughput technologies within the Build phase.

High-Throughput DNA Assembly Strategies

Selecting the appropriate DNA assembly method is foundational to a successful high-throughput workflow. The table below compares the key characteristics of modern assembly techniques amenable to automation.

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput DNA Assembly Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Junction Type | Typical Fragment Number | Key Advantages | Automation Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly [19] | Exonuclease-based seamless cloning | Seamless | 2-11 fragments | High fidelity (>95% efficiency), less sequencing needed, compatible with synthetic fragments | High (supports nanoliter volumes) |

| NEBridge Golden Gate Assembly [19] [20] | Type IIS restriction enzyme digestion and ligation | Seamless (Scarless) | Complex assemblies (>10 fragments) | High efficiency in GC-rich/repetitive regions, flexibility in master mix choice | High (supports miniaturization) |