The Evolution of CAR-T Cell Therapy: From First-Generation Constructs to Fifth-Generation Designs

This article provides a comprehensive review of the groundbreaking evolution of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy, tracing its development from foundational first-generation constructs to sophisticated fifth-generation designs.

The Evolution of CAR-T Cell Therapy: From First-Generation Constructs to Fifth-Generation Designs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the groundbreaking evolution of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy, tracing its development from foundational first-generation constructs to sophisticated fifth-generation designs. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes decades of immunological research, structural engineering breakthroughs, and clinical translation efforts. The scope encompasses the foundational science that enabled T-cell reprogramming, the methodological leaps in CAR design that enhanced potency and persistence, the ongoing troubleshooting of challenges like the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and toxicity, and a comparative validation of clinical outcomes across hematologic and solid tumors. By integrating the most current clinical trial insights and emerging technological trends, this article serves as a critical resource for understanding the past, present, and future trajectory of this transformative immunotherapy.

Laying the Groundwork: The Conceptual and Historical Origins of CAR-T Technology

The development of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a paradigm shift in oncology, yet this breakthrough stands on the shoulders of pioneering work in cancer immunotherapy spanning more than a century. The conceptual journey from William Coley's provocative observations to the sophisticated engineering of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) established the fundamental principles that enabled modern cellular therapeutics. This evolution reflects a growing understanding of immune surveillance, tumor microenvironment interactions, and the mechanisms of immune cell activation—knowledge essential for developing the first through fifth generations of CAR T-cell therapies. Within the broader thesis of CAR T-cell development, these precursor approaches provided the critical proof-of-concept that engineered immune cells could achieve clinically meaningful tumor regression, establishing the technical and conceptual infrastructure for the field [1] [2].

The historical progression demonstrates how empirical observations gradually gave way to mechanism-based therapeutics. Early practitioners noted the correlation between immune activation and tumor regression without understanding the underlying biological processes, while contemporary researchers leverage detailed knowledge of T-cell signaling, antigen recognition, and genetic engineering to create precision therapeutics. This transition from serendipitous observation to rational design encapsulates the development of modern cancer immunotherapy and establishes the context for understanding CAR T-cell engineering [3].

Historical Progression: From Empirical Observation to Mechanism-Based Therapeutics

The Era of Infection-Induced Tumor Regression

The earliest documented precursors to modern cellular therapies emerged from clinical observations rather than theoretical frameworks. In the 1860s, German physicians Wilhelm Busch and Friedrich Fehleisen independently observed tumor regression in patients experiencing erysipelas (a streptococcal skin infection) [1] [2]. These case reports suggested that activated immune responses could influence malignant growth, though the mechanisms remained obscure.

Building on these observations, American bone surgeon William B. Coley systematically developed "Coley's Toxins"—a mixture of heat-killed Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens—which he injected into patients with inoperable malignant tumors [3]. Beginning in 1891, Coley documented numerous cases of tumor regression, particularly in sarcoma patients, achieving complete regression in many of approximately one thousand treated patients [1]. Despite these clinical successes, Coley's approach lacked mechanistic understanding and faced declining adoption due to concerns about infectious agents, inconsistent responses, and the emergence of radiation therapy and chemotherapy [1] [2]. Nevertheless, Coley's work established the fundamental principle that the immune system could be harnessed to fight cancer, earning him the posthumous title "Father of Cancer Immunotherapy" [3].

The Dawn of Immunological Theory

The transition from empirical observation to theoretical framework began in the 1950s with the cancer immunosurveillance hypothesis proposed by Frank Macfarlane Burnet and Lewis Thomas [2] [3]. This theory posited that the immune system continuously scans for and eliminates transformed cells, preventing cancer development in immunocompetent individuals. While initially controversial, this concept gained substantial experimental support decades later through work by Schreiber, Dunn, Old, and their teams, who demonstrated T cells' crucial role in anti-tumor surveillance and responses [2].

Parallel developments in fundamental immunology revealed the cellular actors involved in immune responses. The discovery of T-cell origin and function, particularly the pioneering work of Eva and George Klein demonstrating that immune cells could eradicate cancer, provided crucial insights [4]. Additionally, the identification of cytokines—soluble immune mediators—opened new therapeutic avenues, with interferon-alpha (IFNα) becoming the first FDA-approved cancer immunotherapy in 1986 for hairy-cell leukemia, and interleukin-2 (IL-2) receiving approval in 1992 for metastatic renal cell carcinoma and in 1998 for metastatic melanoma [1].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Early Cancer Immunotherapy

| Year Period | Key Development | Principal Investigators | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860s-1890s | Observation of infection-induced tumor regression | Busch, Fehleisen | Empirical basis for immune-mediated tumor control |

| 1891-1910 | Development of Coley's Toxins | William Coley | Documented tumor regressions in sarcomas; established immunotherapeutic principle |

| 1950s | Cancer immunosurveillance hypothesis | Burnet, Thomas | Theoretical framework for immune-cancer interactions |

| 1976-1990 | BCG approval for bladder cancer | - | First approved immunotherapy for solid tumors |

| 1986-1998 | Cytokine therapies (IFNα, IL-2) | Rosenberg et al. | FDA-approved immunotherapies demonstrating systemic immune activation can yield clinical responses |

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs): The Immediate Cellular Precursor

Conceptual Foundation and Biological Rationale

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) represent the most direct cellular precursor to engineered CAR T cells, bridging the gap between native immune responses and adoptive cell transfer. TILs are naturally occurring T cells that have migrated into tumor tissue and represent the host's endogenous immune response against cancer [5]. The fundamental insight underlying TIL therapy is that these lymphocytes are already pre-selected for tumor recognition, having demonstrated the ability to traffic to tumor sites and recognize tumor-associated antigens [5] [6].

The conceptual foundation for TIL therapy emerged from several key observations. First, the presence of lymphocytes within tumors suggested ongoing immune recognition. Second, studies demonstrated that these infiltrating lymphocytes could be isolated and expanded ex vivo. Third, when reinfused in sufficient quantities, these expanded TIL populations could mediate tumor regression in certain patients, particularly those with metastatic melanoma [2] [6]. Unlike later CAR T-cell approaches, TILs utilize the native T-cell receptor repertoire without genetic modification, relying instead on selection and expansion of naturally occurring tumor-reactive clones [5].

Technical Development and Methodology

The development of TIL therapy is credited primarily to Dr. Steven Rosenberg and colleagues at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), who conducted the first clinical trials in the late 1980s [1] [6]. Their approach leveraged several technical advances in cell culture and immunology to overcome the limitations of native TIL populations, which, while tumor-specific, were typically insufficient in number and often functionally impaired within the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [2].

The standard TIL manufacturing protocol involves multiple precise steps as shown in the workflow below:

Diagram 1: TIL Therapy Workflow

Detailed TIL Protocol Methodology:

Tumor Resection and Processing: Fresh tumor tissue (typically 1-5 cm³) is obtained through surgical resection and mechanically dissociated into fragments of 1-3 mm³ using sterile techniques [5] [6].

TIL Isolation and Initial Culture: Tumor fragments are placed in culture media containing high-dose IL-2 (6000 IU/mL) to selectively expand T lymphocytes while inhibiting tumor cell growth. After 2-3 weeks, outgrown TILs are harvested and assessed for quantity and viability [6].

Rapid Expansion Protocol (REP): TILs undergo massive expansion using anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3), allogeneic feeder cells (typically irradiated peripheral blood mononuclear cells), and high-dose IL-2. This 1-2 week process can expand TIL numbers 500- to 5000-fold, generating the billions of cells required for therapeutic infusion [6].

Patient Lymphodepletion: Prior to TIL infusion, patients receive lymphodepleting chemotherapy (typically cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg/day for 2 days and fludarabine 25 mg/m²/day for 5 days) to eliminate endogenous immunosuppressive cells and create space for the transferred TILs [6].

TIL Infusion and IL-2 Support: Expanded TILs are administered intravenously, followed by high-dose IL-2 (600,000 IU/kg every 8-12 hours for up to 6 doses) to support T-cell persistence and function in vivo [6].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for TIL Therapy

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | IL-2 (aldesleukin) | Drives T-cell expansion and maintains viability; selects for tumor-reactive T cells during initial culture |

| Activation Stimuli | Anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3) | Provides TCR stimulation during rapid expansion protocol |

| Feeder Cells | Irradiated allogeneic PBMCs | Provides necessary co-stimulation for optimal T-cell expansion during REP |

| Culture Media | RPMI-1640 with human serum | Supports T-cell growth while maintaining functionality |

| Lymphodepleting Agents | Cyclophosphamide, Fludarabine | Creates immunodepleted environment to enhance engraftment of transferred TILs |

| Selection Markers | CD3, CD8 | Identifies and enumerates T-cell populations during manufacturing |

Clinical Validation and Limitations

After decades of clinical investigation, TIL therapy received its first FDA approval in February 2024 with lifileucel (Amtagvi) for advanced melanoma, marking a milestone as the first cellular therapy approved for a solid tumor [6]. The approval was based on clinical trial data demonstrating a response rate of approximately 31% in patients who had progressed on immune checkpoint inhibitors, with durable responses lasting years in some cases [6]. The success of TIL therapy in melanoma provided critical proof-of-concept that ex vivo expanded, tumor-specific T cells could mediate regression of established solid tumors.

However, TIL therapy faces several significant limitations that restricted its broader application. The manufacturing process is complex, expensive, and requires specialized facilities [2]. Tumor biopsies are not feasible for all cancer types, and some tumors contain insufficient TILs for expansion [5]. The associated lymphodepleting chemotherapy and high-dose IL-2 administration produce significant toxicity, limiting treatment to medically fit patients [6]. Perhaps most importantly, TIL therapy remains largely restricted to immunogenic "hot" tumors like melanoma, with limited efficacy in less immunogenic malignancies [2].

TILs as a Conceptual Bridge to CAR T-Cell Therapy

Parallels and Divergences in Therapeutic Approach

TIL therapy established several fundamental principles that directly informed CAR T-cell development. Both approaches utilize autologous T cells expanded ex vivo and reinfused following lymphodepletion [5] [6]. Both demonstrate that sufficiently large numbers of tumor-specific T cells can mediate regression of established tumors. However, crucial differences highlight the evolutionary steps toward more engineered solutions.

While TILs rely on naturally occurring T-cell receptors with undefined specificities, CAR T cells are engineered with synthetic receptors providing defined antigen specificity [4] [6]. This fundamental distinction represents the transition from utilizing natural immunity to creating synthetic immunity. Additionally, TIL products contain a heterogeneous mixture of T cells with multiple specificities, while CAR T cells represent a monoclonal or oligoclonal population targeting a single antigen [2]. The genetic engineering aspect of CAR T cells also enables incorporation of enhanced functionality not present in native T cells.

Technical and Conceptual Contributions to CAR T-Cell Development

The TIL field provided several essential technical and conceptual advances that enabled CAR T-cell therapy:

Ex Vivo T-Cell Expansion Protocols: The rapid expansion protocol developed for TILs demonstrated that T cells could be expanded to clinically relevant numbers (10⁹-10¹¹ cells) while maintaining effector function [6].

Lymphodepletion Strategies: Studies with TILs established the critical importance of host preconditioning with lymphodepleting chemotherapy to enhance persistence and efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells [6].

Tumor Microenvironment Understanding: Research on why native TILs failed to control tumor growth revealed key immunosuppressive mechanisms within tumors that later informed strategies to engineer resistance into CAR T cells [4] [7].

Clinical Infrastructure and Regulatory Precedent: The decades of clinical experience with TILs established treatment protocols, toxicity management strategies, and regulatory pathways that accelerated CAR T-cell development [6].

The signaling pathways utilized by TILs through their native T-cell receptors provided the blueprint for designing the intracellular domains of CAR constructs:

Diagram 2: Native T-Cell Receptor Signaling

The Direct Evolution to CAR T-Cell Generations

The limitations of TIL therapy directly motivated the development of increasingly sophisticated CAR designs. The first-generation CARs, conceptualized in 1987 by Kurosawa and colleagues and independently by Eshhar in 1989, addressed the MHC restriction of native TCRs by creating single-chain antibody fragments fused to T-cell signaling domains [1] [4]. This innovation allowed T cells to recognize surface antigens independent of MHC presentation—a crucial advantage for targeting tumors with downregulated MHC expression.

The progression through CAR generations reflects efforts to overcome limitations observed in both TIL therapy and earlier CAR approaches. Second-generation CARs incorporated costimulatory domains (CD28 or 4-1BB) to enhance persistence and functionality [4] [8]. Third-generation constructs combined multiple costimulatory signals to further enhance potency [8]. Fourth-generation "TRUCKs" were engineered to express cytokines that modify the tumor microenvironment [4] [7], while fifth-generation designs incorporate complete cytokine receptor signaling pathways [4] [7].

Table 3: Evolution from TIL Therapy to CAR T-Cell Generations

| Therapeutic Approach | Key Innovation | Addressing TIL Limitations | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIL Therapy | Use of naturally occurring tumor-specific T cells | Foundation for adoptive cell transfer | Proof-of-concept for cellular therapy; efficacy in melanoma |

| 1st Generation CAR | MHC-independent antigen recognition via scFv | Overcoming MHC downregulation; defined specificity | Limited persistence; minimal clinical efficacy |

| 2nd Generation CAR | Single costimulatory domain (CD28 or 4-1BB) | Enhanced persistence and expansion | Dramatic efficacy in B-cell malignancies; multiple FDA approvals |

| 3rd Generation CAR | Multiple costimulatory domains | Further enhanced potency and persistence | Mixed results; limited advantage over 2nd generation |

| 4th Generation CAR (TRUCK) | Inducible cytokine expression | Modifying immunosuppressive microenvironment | In clinical trials; potential for solid tumors |

| 5th Generation CAR | Integrated cytokine receptor signaling | Enhanced proliferation and resistance to exhaustion | Preclinical development; potential for broader applications |

This evolutionary progression demonstrates how the limitations of each approach motivated the innovations of the next, with TIL therapy serving as the foundational platform upon which increasingly sophisticated engineered solutions were built.

The journey from Coley's Toxins to tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes represents more than a historical prelude to modern CAR T-cell therapy—it constitutes the essential conceptual and technical foundation upon which cellular engineering approaches were built. The empirical observations of infection-induced tumor regression established the fundamental principle that immune activation could impact cancer, while the development of TIL therapy demonstrated that ex vivo selected and expanded T cells could mediate clinically meaningful responses in established tumors.

The limitations of TIL therapy—particularly its restriction to immunogenic tumors, complex manufacturing, and dependence on pre-existing tumor immunity—directly motivated the development of engineered CAR T cells that could overcome these constraints. The progressive refinement from first- to fifth-generation CAR designs represents a logical evolution from utilizing natural immunity to creating increasingly sophisticated synthetic immune responses. Within the broader thesis of CAR T-cell development, these precursor approaches provided not only the technical platform for cell processing and expansion but, more importantly, the conceptual framework for understanding how immune cells can be harnessed and enhanced to combat cancer—a principle that continues to drive innovation in cellular engineering today.

The development of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents one of the most transformative advancements in modern immunotherapy, yet its conceptual roots extend back more than a century to Paul Ehrlich's visionary Side-Chain Theory. This evolutionary journey from theoretical immunology to clinical application demonstrates how foundational biological concepts, when combined with innovative genetic engineering technologies, can yield breakthrough therapeutic modalities. Ehrlich's late-19th century proposition that cells possess specific "side chains" or receptors that can recognize and bind toxins fundamentally established the conceptual framework for understanding antibody-antigen interactions [9]. This theory, which initially explained how antibodies were produced and functioned, has now materialized into sophisticated cellular therapies wherein T lymphocytes are genetically engineered to express synthetic receptors capable of precisely targeting malignant cells [10].

The historical continuum from first to fifth-generation CAR T-cells reflects iterative improvements in receptor design, signaling optimization, and functional enhancement, all building upon Ehrlich's core principle of specific molecular recognition. Contemporary synthetic biology approaches have accelerated this evolution through CRISPR-based genome editing, combinatorial screening platforms, and sophisticated molecular engineering [11]. This technical guide examines the key immunological discoveries and genetic technologies that have facilitated this remarkable transition, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource on the theoretical foundations, technical methodologies, and future directions of CAR T-cell immunotherapy.

Historical Foundations: From Theoretical Immunology to Cellular Engineering

Paul Ehrlich's Side-Chain Theory

In 1897, Paul Ehrlich published the first iteration of his seminal Side-Chain Theory, presenting a comprehensive framework to explain immune response specificity [9] [12]. Ehrlich postulated that white blood cells normally produced antibodies that acted as "side chains" or receptors on cell membranes, with each possessing specific binding affinity for particular antigens [9]. He proposed that when toxins or infectious agents entered the body, they would selectively bind to complementary side chains, stimulating the cell to overproduce and shed these receptors into circulation as circulating antibodies [9] [13]. This "lock and key" conceptualization of molecular recognition, borrowed from Emil Fischer's enzyme-substrate model, represented the first mechanistic explanation for antibody specificity and production [9].

Ehrlich's theory contained several revolutionary elements that would later prove foundational to CAR T-cell development. The concept of pre-formed receptor specificity anticipated the clonal selection theory and modern understanding of immune receptor diversity [9]. His proposal that binding specificity resided in chemical structure provided the theoretical basis for engineered recognition domains. Most notably, Ehrlich's description of these side chains as "magic bullets" precisely predicted the targeted therapeutic approach that CAR T-cells embody [9]. The Side-Chain Theory thus established the fundamental principle that cellular immune responses could be directed through specific receptor-antigen interactions, a concept that would lie dormant for decades before reemerging in cellular engineering approaches.

Key Historical Developments in Immunotherapy

Table 1: Historical Foundations of Cellular Immunotherapy

| Year | Scientist/Event | Contribution | Significance to CAR T-Cell Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1718 | Lady Mary Wortley Montagu | Introduced smallpox inoculation to England | Established principle of induced immunity [13] |

| 1860s-1890s | Busch, Fehleisen, Coley | Observed tumor regression following infections | First evidence of immune system's anti-cancer potential [1] [2] |

| 1897 | Paul Ehrlich | Proposed Side-Chain Theory | Conceptual foundation for specific receptor-antigen interactions [9] [13] |

| 1957 | Thomas and Burnet | Cancer immunosurveillance theory | Established T cells' role in anti-tumor immunity [2] |

| 1980s | Steven Rosenberg | Developed tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy | Proof-of-concept for adoptive cell transfer [1] [2] |

| 1987 | Yoshikazu Kurosawa | First chimeric T-cell receptor | Demonstrated concept of engineered receptor signaling [1] |

The conceptual journey from Ehrlich's theory to cellular engineering required numerous intermediate discoveries that expanded understanding of immune function and manipulation. Critical among these was Macfarlane Burnet's clonal selection theory (1957), which provided a modernized framework for how specific immune responses emerge from individual lymphocyte clones [13]. The work of Steven Rosenberg on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in the 1980s demonstrated that naturally occurring T-cells with anti-tumor activity could be expanded ex vivo and reinfused to mediate cancer regression, establishing adoptive cell transfer as a viable therapeutic approach [1] [2]. However, TIL therapy faced significant limitations, including the difficulty of isolating sufficient tumor-reactive T cells from patients and their restricted specificity [2]. These challenges motivated the development of synthetic approaches to generate T cells with defined specificities.

The Evolution of CAR T-Cell Technology

Fundamental CAR T-Cell Design and Mechanism

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy represents the clinical realization of synthetic immunology, combining the targeting specificity of antibodies with the cytotoxic potency and memory capacity of T lymphocytes [10]. CAR T-cells are generated through leukapheresis of patient T cells, followed by ex vivo genetic modification to express a synthetic receptor that redirects them to surface antigens on target cells [10] [2]. The fundamental CAR structure consists of an extracellular antigen-recognition domain (typically a single-chain variable fragment derived from an antibody), a hinge region, a transmembrane domain, and intracellular signaling modules that initiate T-cell activation upon antigen engagement [2].

The manufacturing process for CAR T-cells requires approximately 3-5 weeks from blood collection to infusion of the final product [10]. During this period, T cells are activated, genetically modified using viral vectors (typically lentivirus or retrovirus), and expanded to hundreds of millions of cells [10]. Following quality control testing, the CAR T-cell product is cryopreserved and shipped back to the treatment center for infusion into the lymphodepleted patient [10]. This lymphodepletion, typically achieved through chemotherapy, creates a favorable cytokine environment for CAR T-cell expansion and persistence by eliminating endogenous immune cells that compete for homeostatic cytokines [2].

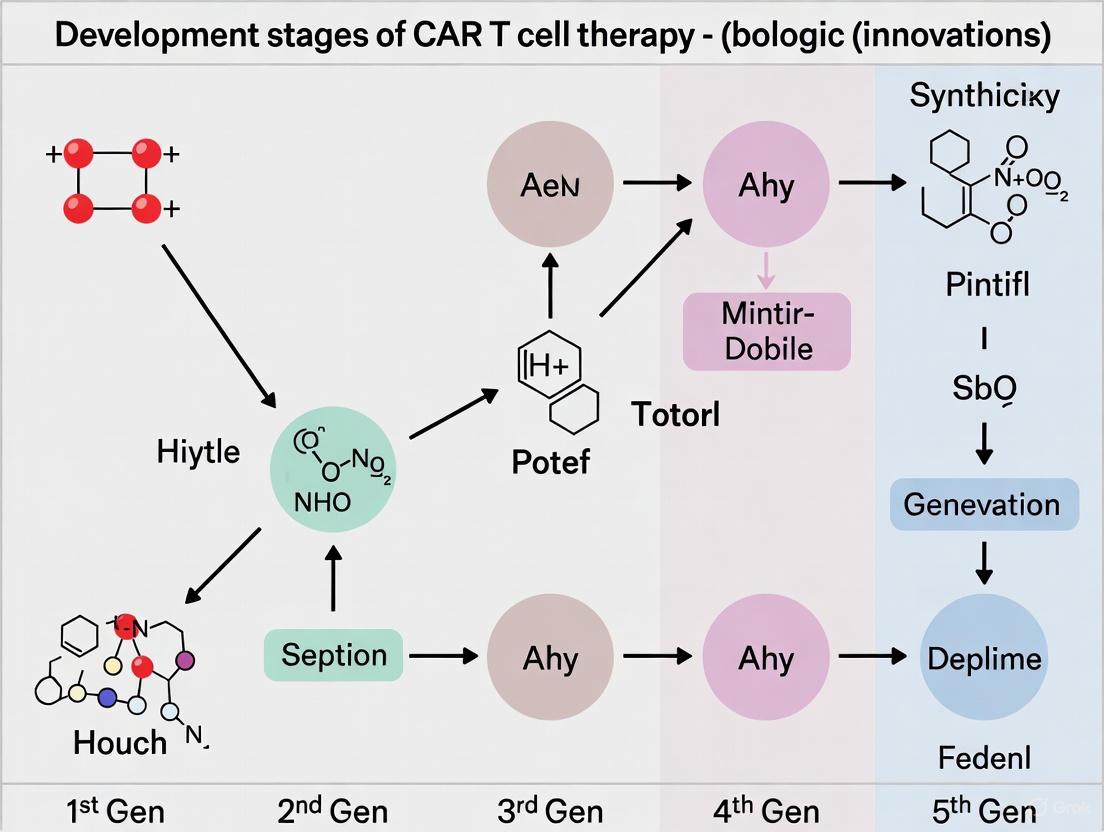

Diagram 1: Basic structure of a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). The modular design includes an antigen-recognition domain, structural components, and intracellular signaling modules.

Generational Evolution of CAR Design

Table 2: Evolution of CAR T-Cell Generations

| Generation | Signaling Components | Key Features | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | CD3ζ only | Single signaling domain; limited persistence and expansion | Primarily preclinical [2] |

| Second | CD3ζ + one costimulatory domain (CD28 or 4-1BB) | Enhanced persistence, expansion, and cytotoxicity | FDA-approved products (Kymriah, Yescarta) [10] [2] |

| Third | CD3ζ + multiple costimulatory domains (e.g., CD28+4-1BB) | Multiple costimulatory signals; further enhanced functionality | Clinical trials for hematologic malignancies [2] |

| Fourth | Incorporation of cytokine secretion or constitutive signaling | Enhanced tumor microenvironment modulation; "armored" CARs | Clinical trials for solid tumors [2] |

| Fifth | Integrated cytokine receptors or inducible pathways | Proliferation independent of exogenous cytokines; precision control | Preclinical and early clinical development [2] |

The evolutionary trajectory of CAR T-cell designs reflects iterative improvements in intracellular signaling optimization. First-generation CARs incorporating only the CD3ζ signaling domain demonstrated limited expansion and persistence in clinical applications due to the absence of costimulatory signals [2]. This limitation was addressed in second-generation CARs through the incorporation of either CD28 or 4-1BB costimulatory domains, which significantly enhanced T-cell proliferation, persistence, and cytotoxic function [10] [2]. The CD28-based costimulatory domains typically produce more potent effector responses, while 4-1BB domains favor enhanced persistence and memory formation [2].

Third-generation CARs combine multiple costimulatory signals (e.g., CD28 + 4-1BB) to further augment potency, though with increased concern about potential exhaustion from excessive signaling [2]. Fourth-generation "armored" CARs represent a more sophisticated approach, incorporating transgenic cytokine expression (e.g., IL-12) or resistance mechanisms to immunosuppressive factors in the tumor microenvironment [2]. The emerging fifth-generation CARs utilize truncated cytokine receptors (e.g., IL-2Rβ) that activate multiple signaling pathways (JAK/STAT) while maintaining antigen specificity, creating autonomous proliferation capacity without exogenous cytokine support [2].

Synthetic Biology and Advanced Engineering Approaches

CRISPR-Based CAR T-Cell Enhancement

Recent advances in synthetic biology, particularly CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, have enabled systematic discovery and optimization of CAR T-cell functions. The CELLFIE platform represents a state-of-the-art approach for high-content CRISPR screening in human primary CAR T-cells, enabling genome-wide identification of gene knockouts that enhance therapeutic efficacy [11]. This platform addresses key experimental challenges through efficient co-delivery of CAR constructs, guide RNA libraries, and CRISPR editors via optimized mRNA electroporation and lentiviral transduction [11].

In a landmark 2025 study, genome-wide CRISPR screens using the CELLFIE platform identified several unexpected gene knockouts that significantly enhance CAR T-cell function, including RHOG, PRDM1, and FAS [11]. RHOG knockout was particularly notable as RHOG deficiency causes immunodeficiency in humans, highlighting the different biological requirements of natural T-cells versus therapeutic CAR T-cells [11]. The synergistic combination of RHOG and FAS knockouts demonstrated potent enhancement of anti-tumor activity across multiple in vivo models, CAR designs, and donor samples [11]. These discoveries exemplify how synthetic biology approaches can identify counterintuitive engineering strategies that would be difficult to predict through conventional biological reasoning.

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for CRISPR-enhanced CAR T-cell manufacturing. The process combines conventional CAR transduction with CRISPR genome editing for enhanced functionality.

Research Reagent Solutions for CAR T-Cell Development

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CAR T-Cell Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAR Vectors | Lentiviral CROP-seq-CAR vector | Co-delivery of CAR and gRNA sequences | Enables single-vector delivery for screening [11] |

| CRISPR Editors | Cas9 mRNA, ABEmax, AncBE4max | Genome editing; knockout and base editing | mRNA enables versatile editor delivery [11] |

| Screen Libraries | Brunello gRNA library | Genome-wide knockout screening | Validated library for human primary T cells [11] |

| Activation Reagents | Anti-CD3/CD28 beads | T-cell activation and expansion | Mimics physiological activation [11] |

| Cytokines | IL-2, IL-7, IL-15 | T-cell expansion and persistence | Concentration affects differentiation [1] [2] |

| Selection Markers | Blasticidin resistance | Selection of successfully transduced cells | Antibiotic selection for screen robustness [11] |

The advanced engineering of CAR T-cells requires specialized reagents optimized for primary human T-cell manipulation. The CROP-seq-CAR vector system enables simultaneous expression of the CAR construct and guide RNA from a single lentiviral backbone, simplifying complex genetic modifications [11]. For CRISPR-mediated editing, mRNA-based delivery of CRISPR editors (Cas9, base editors) provides greater versatility and efficiency compared to protein or plasmid DNA approaches, with editing efficiencies typically exceeding 80% in primary T cells [11].

Functional screening depends on properly designed guide RNA libraries such as the Brunello genome-wide library, which provides comprehensive coverage with minimal off-target effects [11]. T-cell activation reagents including anti-CD3/CD28 beads are essential for initiating the expansion and genetic modification processes, with stimulation conditions significantly influencing subsequent CAR T-cell function and differentiation state [11]. Careful selection of ex vivo culture cytokines (IL-2, IL-7, IL-15) is critical as these factors profoundly affect the resulting T-cell phenotype, with lower IL-2 concentrations generally favoring less differentiated memory populations [2].

Clinical Applications and Current Challenges

Approved CAR T-Cell Therapies and Efficacy

Since the first FDA approval of tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) in 2017 for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, CAR T-cell therapies have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in treating hematologic malignancies [1] [10]. As of April 2023, six CAR T-cell products have received FDA approval for various B-cell malignancies, with unprecedented response rates in patients with otherwise untreatable diseases [1]. Clinical trials have shown that these therapies can achieve complete remission in 70-90% of children and young adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL, with many patients maintaining long-term disease-free survival [10]. Similarly, in adults with advanced lymphomas, CAR T-cell therapy has produced complete response rates of 40-50% in patients who had exhausted all conventional treatment options [10].

Table 4: FDA-Approved CAR T-Cell Therapies (as of 2023)

| Therapy Name | Target | Approved Indications | Notable Efficacy Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kymriah (tisa-cel) | CD19 | B-cell ALL (pediatric/young adult); DLBCL; Follicular lymphoma | 81% remission rate in pediatric ALL at 3 months [10] |

| Yescarta (axi-cel) | CD19 | Large B-cell lymphoma; Follicular lymphoma | 79% complete response in follicular lymphoma trial [10] |

| Tecartus (brexu-cel) | CD19 | B-cell ALL (adult); Mantle cell lymphoma | 61% complete response in mantle cell lymphoma [10] |

| Breyanzi (liso-cel) | CD19 | Follicular lymphoma; Large B-cell lymphoma; CLL; Mantle cell lymphoma | 73% overall response rate in DLBCL [10] |

| Abecma (ide-cel) | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | 72% overall response rate in multiple myeloma [10] |

| Carvykti (cilta-cel) | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | 98% overall response rate in multiple myeloma [10] |

Adverse Events and Management Strategies

The potent immune activation mediated by CAR T-cells produces characteristic toxicities that require specialized management. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) represents the most common adverse event, characterized by fever, hypotension, and potential organ dysfunction resulting from massive cytokine release following CAR T-cell activation [1] [10]. The severity of CRS correlates with pretreatment tumor burden, with higher burden predicting more severe manifestations [1]. Current management employs the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab (Actemra), often with corticosteroids for refractory cases [10].

Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) encompasses neurological complications including confusion, aphasia, impaired motor skills, and potentially cerebral edema [10]. The pathophysiology of ICANS involves endothelial activation and blood-brain barrier disruption, with elevated inflammatory cytokines in the cerebrospinal fluid [10]. Management typically involves corticosteroids, with the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra (Kineret) showing promise for severe or refractory cases [10]. Additional complications include B-cell aplasia and hypogammaglobulinemia resulting from on-target destruction of normal B cells, requiring immunoglobulin replacement [10], and infections due to associated cytopenias and immunosuppressive treatments [1].

Solid Tumor Challenges and Innovative Solutions

Despite remarkable success in hematologic malignancies, CAR T-cell therapy for solid tumors faces substantial obstacles. The immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment presents multiple barriers, including regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and inhibitory cytokines that impair CAR T-cell function and persistence [10] [2]. Tumor heterogeneity with variable antigen expression enables immune escape through antigen-loss variants [10]. Additional challenges include limited tumor infiltration due to physical and chemical barriers, and on-target/off-tumor toxicity when target antigens are expressed on healthy tissues [2].

Innovative approaches to overcome these limitations include:

- Armored CARs expressing cytokines (IL-12, IL-18) or dominant-negative receptors for TGF-β to resist immunosuppression [2]

- Multi-targeting strategies using tandem CARs or co-infusion of CARs targeting different antigens to prevent immune escape [2]

- Local delivery to overcome trafficking barriers, demonstrated in trials for glioblastoma and pleural malignancies [2]

- Safety switches (e.g., inducible caspase-9) to mitigate toxicity by enabling elimination of CAR T-cells if adverse events occur [2]

Promising clinical results have emerged for specific solid tumors, particularly diffuse midline glioma in children and young adults, where CAR T-cell therapy has demonstrated encouraging activity in early-phase trials [10]. Ovarian and colorectal cancers have also shown responses in early clinical investigations, though durability remains limited [10].

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The field of CAR T-cell therapy continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends likely to shape future development. Allogeneic "off-the-shelf" CAR T-cells derived from healthy donors aim to overcome the logistical and manufacturing limitations of autologous approaches, though they require additional engineering to prevent graft-versus-host disease and host rejection [10]. Combination therapies integrating CAR T-cells with immune checkpoint inhibitors, small molecule targeted therapies, or conventional chemotherapy seek to enhance efficacy and prevent resistance [2]. Novel engineering approaches including inducible expression systems, logic-gated receptors, and precision control mechanisms using small molecule regulators are advancing toward clinical testing [2].

The ongoing integration of synthetic biology and immunology exemplifies how Ehrlich's concept of specific cellular targeting has matured into a sophisticated therapeutic platform. The systematic discovery approaches enabled by technologies like the CELLFIE CRISPR screening platform promise to accelerate the identification of optimal genetic modifications for specific clinical contexts [11]. As the field addresses current limitations in solid tumors, toxicity management, and manufacturing accessibility, CAR T-cell therapy is poised to expand beyond its current hematologic focus to become a modular platform applicable to autoimmune diseases, chronic infections, and eventually non-malignant conditions [1] [2].

The journey from Ehrlich's Side-Chain Theory to modern CAR T-cell therapy demonstrates how foundational immunological concepts, when combined with transformative technologies, can yield paradigm-shifting therapeutic modalities. This progression from theoretical understanding to clinical implementation represents a landmark achievement in translational medicine, offering a template for how other fundamental biological insights might be similarly developed into powerful therapeutic tools. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of increasingly sophisticated engineering approaches with deep immunological understanding promises to further expand the potential of cellular immunotherapy to address diverse human diseases.

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy represents a paradigm shift in cancer treatment, demonstrating remarkable success in treating hematological malignancies. This groundbreaking approach involves genetically engineering a patient's own T cells to express synthetic receptors that redirect them to selectively target and eliminate tumor cells. The clinical success of CAR-T cells is intrinsically linked to the sophisticated design of the CAR molecule itself. Since its initial conceptualization in the late 1980s, the core structure of the CAR has evolved through multiple generations, each refining its components to enhance efficacy, persistence, and safety [1] [4] [2]. All CARs share a fundamental modular architecture, comprising four essential domains: the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) for antigen recognition, the hinge for flexibility and spacing, the transmembrane domain for anchor stability, and the intracellular signaling domain for T-cell activation [14]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical deconstruction of these core structural domains, examining their individual functions, the impact of their design choices on CAR-T cell performance, and their evolution within the broader historical context of CAR-T cell therapy development.

Historical Context: The Generational Evolution of CAR Design

The evolution of CAR-T cells is categorized into generations based primarily on the complexity of their intracellular signaling domains, which directly influence T-cell activation potency and persistence.

Table 1: Generations of Chimeric Antigen Receptors

| Generation | Intracellular Signaling Domains | Key Features & Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| First | CD3ζ only [15] | Limited efficacy; insufficient IL-2 production; low proliferation and short in vivo persistence [15]. |

| Second | CD3ζ + one co-stimulatory domain (e.g., CD28 or 4-1BB) [4] [15] | Enhanced T-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, cytokine production, and persistence [4] [15]. CD28 domains promote rapid tumor elimination, while 4-1BB domains favor long-term persistence [15]. |

| Third | CD3ζ + multiple co-stimulatory domains (e.g., CD28-4-1BB) [4] | Designed to further amplify signaling; however, they have not consistently demonstrated superior efficacy compared to second-generation CARs in clinical settings [15]. |

| Fourth (TRUCK) | CD3ζ + one co-stimulatory domain + inducible transgene (e.g., IL-12) [4] [15] | Engineered to deliver transgenic proteins (e.g., cytokines) to the tumor microenvironment, modulating the local immune response and enhancing anti-tumor efficacy [15]. |

| Fifth | CD3ζ + one co-stimulatory domain + additional membrane receptor (e.g., IL-2R β-chain) [4] | Incorporates truncated cytokine receptors (e.g., from IL-2) to activate the JAK/STAT pathway in an antigen-dependent manner, further promoting CAR-T cell growth and memory formation [4] [15]. |

The following diagram illustrates the structural evolution across these generations, highlighting the key differences in their intracellular domains.

Domain-by-Domain Deconstruction of the Core CAR Structure

Antigen Recognition Domain: The scFv

The single-chain variable fragment (scFv) is the antigen-binding domain located at the outermost end of the CAR. It is derived from the variable regions of the heavy (VH) and light (VL) chains of a monoclonal antibody, connected by a short, flexible peptide linker [4]. This design confers the critical advantage of MHC-independent antigen recognition, allowing CAR-T cells to target tumors that downregulate MHC molecules to evade native T-cell immunity [4]. The specificity of the scFv determines the target antigen and is, therefore, the primary determinant of both the efficacy and the safety profile of the CAR-T cell product, particularly with respect to "on-target, off-tumor" toxicity [4].

Hinge/Spacer Domain: The Structural Regulator

The hinge, or spacer, is a flexible extracellular region that connects the scFv to the transmembrane domain. It serves multiple critical functions:

- Accessibility: It provides steric flexibility, allowing the scFv to access membrane-proximal target antigens that might otherwise be inaccessible [16] [4].

- Signaling Threshold: The length and composition of the hinge directly influence the signaling threshold of the CAR. For instance, studies have shown that CARs with a CD8α-derived hinge domain can exhibit significant functional differences compared to those with a CD28-derived hinge, even when surface expression levels are equal [16].

- Structural Dynamics: Recent biophysical studies reveal that hinge domains, such as those from CD28 and CD8α, are intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) that exhibit local structural elements and conformational exchange (e.g., proline isomerization) amidst global disorder [17]. This structural plasticity is crucial for its function, contributing to an extended geometry that may regulate domain spacing and interaction with other surface molecules [17].

Transmembrane Domain: The Anchor and Stability Mediator

The transmembrane (TM) domain is an alpha-helical region that anchors the CAR to the T-cell membrane. It is derived from native immune proteins such as CD3ζ, CD4, CD8α, or CD28 [16]. The choice of TM domain has a profound impact on CAR function, primarily by regulating its surface expression level and stability. Research indicates that the transmembrane domain, more than the hinge, greatly affects the CAR expression level and stability on the T cell [16]. Furthermore, the TM domain can influence CAR function by mediating homodimerization (e.g., CD3ζ) or heterodimerization with endogenous signaling proteins, which can affect the tonic signaling and overall persistence of the CAR-T cells [16].

Intracellular Signaling Domains: The Activation Engine

The intracellular domain is the functional endpoint of the CAR, responsible for initiating T-cell activation upon antigen binding. Its composition defines the generation of the CAR.

- CD3ζ Chain: This is the primary signaling component, derived from the T-cell receptor (TCR) complex. It contains immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) that, when phosphorylated, initiate the canonical T-cell activation cascade leading to cytokine production, proliferation, and cytotoxic granule release [4] [15].

- Co-stimulatory Domains: The incorporation of one or more co-stimulatory domains (e.g., CD28, 4-1BB, OX40) is the hallmark of second and later-generation CARs. These domains provide a secondary signal that is crucial for full T-cell activation:

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Hinge and Transmembrane Domain Variations on CAR-T Cell Function (Experimental Data)

| CAR Variant (Hinge/TM) | CAR Expression Level | Stability on T Cell | Antigen-Specific Function | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3ζ / CD3ζ (Basic CAR) | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Used as a reference for comparison [16]. |

| CD8α / CD3ζ | Similar to other variants | Not significantly affected | Significantly different despite equal expression | Hinge domain independently affects signaling intensity [16]. |

| CD28 / CD3ζ | Similar to other variants | Not significantly affected | Significantly different despite equal expression | Hinge domain regulates the CAR signaling threshold [16]. |

| Various / Non-CD3ζ (e.g., CD4, CD8α, CD28) | Greatly affected | Greatly affected | Correlated with expression levels | Transmembrane domain regulates CAR expression level, thereby controlling the amount of CAR signaling [16]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Hinge and Transmembrane Domain Function

The following methodology outlines a systematic approach to evaluate the role of hinge and transmembrane domains, as referenced in the scientific literature [16].

Generation of CAR Structural Variants

- Vector Backbone: Utilize a retroviral vector (e.g., pMXs-Puro) for stable gene expression.

- CAR Construct Design: Clone a basic CAR construct containing an Igκ-chain leader sequence, an epitope tag (e.g., HA-tag), an scFv specific for a target antigen (e.g., mVEGFR2), and murine CD3ζ-derived hinge, transmembrane, and signaling domains (denoted as mV/3z/3z/3z).

- Domain Modification: Generate variant CARs using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and Gibson assembly to create combinations where the hinge or hinge/transmembrane domains are replaced with sequences derived from other immune molecules such as CD4, CD8α, and CD28.

- Sequence Verification: Confirm the sequence integrity of all plasmid constructs by DNA sequencing.

Production of CAR-T Cells

- Virus Production: Generate retrovirus by transducing packaging cell lines (e.g., Plat-E cells) with the constructed CAR vectors.

- T Cell Activation: Isolate and activate primary human or murine T cells using anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies.

- Transduction: Transduce activated T cells with the retroviral supernatant on Retronectin-coated plates under stimulation.

- Selection and Expansion: Culture transduced T cells in medium containing interleukin-2 (IL-2) and a selection antibiotic (e.g., puromycin) to generate a stable CAR-T cell population.

Functional and Phenotypic Analysis

- Surface Expression Analysis:

- Staining: Stain CAR-T cells with a fluorescently labeled antibody against the epitope tag (e.g., anti-HA-APC) and a viability dye.

- Quantification: Analyze CAR surface expression levels using flow cytometry. Report as Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI).

- Antigen-Binding Capacity:

- Incubation: Incubate CAR-T cells with a recombinant target antigen fused to an Fc region (e.g., mVEGFR2-Fc).

- Detection: Detect binding using a fluorescently labeled anti-Fc antibody and analyze via flow cytometry.

- Functional Assays:

- Cytotoxicity: Co-culture CAR-T cells with antigen-positive target cells and measure specific lysis using real-time cell analysis (e.g., xCelligence) or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assays.

- Cytokine Production: Measure antigen-specific cytokine release (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-2) in co-culture supernatants using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

- Proliferation: Assess CAR-T cell expansion following antigen stimulation by tracking dye dilution (e.g., CFSE) or by simply counting cells over time.

The experimental workflow for characterizing CAR-T cells is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents required for the experimental analysis of CAR structure and function as described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CAR-T Cell Development and Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | Delivery of CAR transgene into T cells. | pMXs-Puro (retroviral), pcDNA3.1-Zeo (mRNA transcription) [16]. |

| Packaging Cell Lines | Production of viral vectors for transduction. | Plat-E cells for retrovirus packaging [16]. |

| T Cell Activation Reagents | Ex vivo activation of T cells prior to genetic modification. | Anti-CD3ε mAb (e.g., clone 145-2C11), Anti-CD28 mAb (e.g., clone 37.51) [16]. |

| Gene Editing Tools | Knockout of endogenous genes (e.g., TCR, HLA) in allogeneic UCAR-T; precise CAR integration. | CRISPR/Cas9, Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Base Editors [18]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Detection of CAR expression, immunophenotyping, and analysis of T cell subsets. | Anti-HA Tag mAb (for CAR detection), Anti-CD8α mAb, Viability dyes (e.g., Zombie Aqua) [16]. |

| Recombinant Antigen Proteins | Validation of CAR antigen-binding specificity and affinity. | Recombinant VEGFR2-Fc Chimera protein [16]. |

| Cytokine Assays | Quantification of T cell activation and functional potency. | ELISA kits for IFN-γ, IL-2 [16]. |

The blueprint of a chimeric antigen receptor is a masterpiece of synthetic biology, where each domain—scFv, hinge, transmembrane, and signaling modules—can be precisely engineered to tailor the function, efficacy, and safety of the resulting cellular therapeutic. The historical journey from first to fifth-generation CARs underscores a focused effort to amplify and sustain T-cell activation while overcoming the formidable barriers posed by the tumor microenvironment and on-target/off-tumor toxicity. Future directions in CAR design are increasingly sophisticated, moving beyond the standard architecture to include universal "off-the-shelf" CAR-T cells (UCAR-T) that require gene editing to ablate the endogenous TCR and HLA to prevent graft-versus-host disease and host rejection [18]. Furthermore, the incorporation of safety switches, cytokine "arms," and logic-gated systems represents the next frontier in making CAR-T cell therapy safer, more effective, and applicable to a broader range of diseases, including solid tumors and autoimmune conditions [15] [10]. A deep and mechanistic understanding of the core CAR structure remains the essential foundation upon which these next-generation innovations are built.

The conceptualization of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a paradigm shift in cancer treatment, marking the transition from pharmacologic agents to living cellular therapeutics. The pioneering first-generation CARs, though limited in clinical efficacy, established the foundational architecture upon which all subsequent CAR designs have been built. These early constructs provided critical proof-of-concept that T-cells could be genetically reprogrammed to recognize surface antigens independently of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction, thereby overcoming a fundamental limitation of native T-cell immunity [4]. The development of these initial CARs emerged from decades of foundational immunology research, including the observations of graft-versus-tumor effects in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and the pioneering work of Steven Rosenberg with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes [1]. This review examines the structural basis, clinical implementation, and invaluable lessons from early-generation CAR trials that ultimately paved the way for modern cell therapies.

Structural Blueprint of First-Generation CARs

The fundamental architecture of first-generation CARs established the modular template that remains recognizable in contemporary designs. These pioneering receptors consisted of three core components: an extracellular antigen-recognition domain, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular signaling domain [4].

The extracellular domain featured a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from monoclonal antibodies, which provided specific binding to target antigens. This scFv was created by joining the variable regions of immunoglobulin heavy and light chains (VH and VL) via a short, flexible peptide linker [4]. This design enabled MHC-independent antigen recognition, a crucial advantage over native T-cell receptors.

The transmembrane domain, typically derived from CD4, CD8, or CD28, anchored the receptor to the T-cell membrane and facilitated stable expression. The intracellular component consisted solely of the CD3ζ chain from the T-cell receptor complex, which contained immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) necessary for initiating T-cell activation upon antigen engagement [4].

This structural configuration, while elegantly simple, proved insufficient for generating robust, persistent antitumor responses in clinical settings. The absence of co-stimulatory signaling resulted in limited T-cell proliferation, rapid exhaustion, and inadequate persistence of the engineered cells [4].

Table: Structural Components of First-Generation CARs

| Component | Description | Common Sources | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Domain | Single-chain variable fragment (scFv) | Monoclonal antibody variable regions | Antigen recognition independent of MHC |

| Hinge/Spacer | Immunoglobulin-like domains | CD8, CD28, IgG | Separates binding units from cell membrane |

| Transmembrane Domain | Hydrophobic alpha-helix | CD4, CD8, CD28 | Anchors CAR to T-cell membrane |

| Intracellular Domain | CD3ζ chain | T-cell receptor complex | Initiates activation signaling via ITAMs |

Historical Foundation and Key Pioneers

The conceptual groundwork for CAR-T therapy emerged from transformative research in the late 1980s. In 1987, Japanese immunologist Yoshikazu Kurosawa and his team published the first report of a chimeric T-cell receptor, demonstrating that engineered receptors could activate T-cells in response to specific antigens [1]. This landmark study expressed anti-phosphorylcholine chimeric receptors in murine T-cell lymphoma cells and observed calcium influx upon antigen challenge, providing the first evidence that chimeric receptors could initiate T-cell signaling [1].

Two years later, in 1989, Israeli immunologist Zelig Eshhar and colleagues at the Weizmann Institute of Science described a similar approach, creating "T-bodies" by fusing antibody-derived binding domains with T-cell signaling components [4] [1]. Eshhar's work was particularly influential in establishing the basic CAR architecture that would guide future developments.

These pioneering studies established the core principle that T-cells could be redirected to recognize predefined cell surface antigens through genetic engineering, bypassing the MHC restriction that limited native T-cell responses. This fundamental insight would eventually catalyze the entire field of CAR-T therapy, though clinical application would require more than two decades of further refinement.

Clinical Translation and Pioneering Trials

The transition of first-generation CARs from laboratory concept to clinical application revealed significant limitations in their therapeutic potential. Early clinical trials targeting ovarian cancer and neuroblastoma demonstrated the safety and feasibility of the approach but revealed inadequate antitumor efficacy and poor persistence of the engineered T-cells [4].

One particularly instructive trial investigated anti-CD19 CARs for B-cell malignancies, where researchers observed limited expansion and transient persistence of the infused cells [4]. Similarly, trials targeting carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) in renal cell carcinoma and Lewis Y in ovarian cancer confirmed that first-generation CARs could traffic to tumor sites and initiate target cell killing but failed to generate sustained responses [4].

These clinical experiences collectively highlighted a critical limitation: the CD3ζ signaling domain alone provided insufficient activation signals to generate robust, long-lasting T-cell responses against established tumors. The engineered T-cells exhibited limited proliferative capacity and underwent premature exhaustion or apoptosis, ultimately failing to establish durable immunological memory against malignant cells.

Table: Select Early Clinical Trials of First-Generation CARs

| Target Antigen | Malignancy | Key Findings | Limitations Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD19 | B-cell Leukemia/Lymphoma | Specific target cell elimination | Limited T-cell persistence and expansion |

| CAIX | Renal Cell Carcinoma | Trafficking to tumor sites | On-target off-tumor toxicity against bile duct |

| Lewis Y | Ovarian Cancer | Acceptable safety profile | Limited clinical efficacy |

| GD2 | Neuroblastoma | Feasibility of approach | Inadequate long-term persistence |

Critical Limitations and Fundamental Challenges

The clinical investigation of first-generation CARs revealed several fundamental challenges that would require structural redesign to overcome. Three primary limitations emerged as consistent themes across multiple trials:

Inadequate T-cell Activation and Persistence

The absence of co-stimulatory signaling proved to be the most significant limitation of first-generation CARs. Native T-cell activation requires both T-cell receptor engagement (signal 1) and co-stimulatory signals (signal 2) through receptors such as CD28 or 4-1BB [4]. First-generation CARs provided only the primary activation signal through CD3ζ, resulting in suboptimal T-cell proliferation, diminished cytokine production, and failure to establish long-term persistence of the engineered cells [4].

Restricted Antitumor Efficacy

The limited activation capacity of first-generation CARs translated directly to restricted antitumor efficacy in clinical settings. Without sustained expansion and persistence, the engineered T-cells could not overcome established tumors, particularly in scenarios of high tumor burden [4]. This was especially problematic for solid tumors, which present additional barriers including immunosuppressive microenvironments and physical barriers to T-cell infiltration [19].

On-Target, Off-Tumor Toxicity

Early trials revealed the critical importance of target antigen selection. The CAIX-directed CAR trial in renal cell carcinoma demonstrated that target expression on normal tissues could lead to on-target, off-tumor toxicity, with patients experiencing cholangitis due to low-level CAIX expression on bile duct epithelium [4]. This highlighted the necessity for tumor-restricted antigens, a particular challenge for solid tumors that often share surface antigens with healthy tissues [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and evaluation of first-generation CARs relied on a specialized set of research tools and methodologies that established standards for the field.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Early CAR Development

| Reagent/Technique | Function | Application in Early CAR Development |

|---|---|---|

| Retroviral Vectors | Gene delivery system | Semi-random integration of CAR transgene into T-cell genome |

| Single-Chain Variable Fragment (scFv) | Antigen recognition domain | Derived from monoclonal antibodies for MHC-independent targeting |

| CD3ζ Signaling Domain | Primary T-cell activation | Provided ITAM motifs for initial activation signaling |

| Phospholipase C Gamma Assays | Calcium flux measurement | Verification of CAR signaling functionality |

| Cytokine Release Assays | T-cell activation assessment | Quantification of IFN-γ, IL-2 production after antigen engagement |

| Chromium-51 Release Assays | Cytotoxicity measurement | In vitro assessment of CAR-mediated target cell killing |

Visualizing CAR-T Cell Workflows and Signaling

The experimental workflows for evaluating first-generation CARs established standardized approaches for T-cell engineering and functional validation. The following diagrams illustrate these processes using the specified color palette.

First-Generation CAR Structure

Early CAR-T Experimental Workflow

The investigation of first-generation CARs, while demonstrating limited clinical success, provided the essential foundation for the revolutionary cellular immunotherapies that would follow. These pioneering studies established the fundamental architecture of synthetic antigen receptors, validated the core concept of MHC-independent T-cell targeting, and identified the critical limitation of absent co-stimulation that would drive the development of second-generation constructs. The clinical experiences with these early CARs highlighted the importance of target antigen selection, the necessity for robust T-cell persistence, and the challenges of balancing efficacy with toxicity. These lessons directly informed the design of subsequent CAR generations that would eventually achieve remarkable clinical responses in hematologic malignancies. The first clinical concept of CAR-T therapy, despite its limitations, thus represents a crucial milestone in the evolution of cellular immunotherapy, establishing both the possibilities and parameters that would guide future innovation in the field.

Engineering the Revolution: Methodological Leaps from Second- to Fifth-Generation CARs

The development of second-generation chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy marks a pivotal advancement in cancer immunotherapy, primarily through the incorporation of costimulatory domains. The choice between the two predominant costimulatory molecules, CD28 and 4-1BB, represents a critical design decision that profoundly influences the phenotype, functionality, and clinical performance of CAR-T products. This technical review provides an in-depth comparison of CD28- and 4-1BB-based CARs, examining their distinct signaling pathways, metabolic profiles, kinetic behaviors, and clinical outcome correlates. Framed within the broader evolution of CAR-T technology from first to fifth-generation constructs, we synthesize preclinical evidence and clinical data to guide researchers and drug development professionals in optimizing CAR architectures for specific therapeutic applications.

The evolution of CAR-T cell therapy from concept to clinical reality has been characterized by successive innovations in receptor design, with the integration of costimulatory signaling representing the most transformative advancement. First-generation CARs, which contained only the CD3ζ signaling domain without costimulatory components, demonstrated limited efficacy due to insufficient T-cell activation, poor persistence, and inadequate cytokine production [15] [20]. This fundamental limitation reflected the biological reality that effective T-cell activation requires both a primary signal (through the TCR/CD3 complex) and a secondary costimulatory signal [21].

The advent of second-generation CARs addressed this critical limitation by incorporating a single costimulatory domain in tandem with the CD3ζ chain [15] [4]. The two costimulatory domains that have demonstrated the most clinical success are CD28 and 4-1BB (CD137), both of which are now represented in FDA-approved products [21] [22]. While these designs have produced remarkable clinical outcomes in B-cell malignancies, they impart fundamentally different functional properties on engineered T cells [22]. Understanding these distinctions is essential for optimizing CAR-T products for specific clinical contexts and patient populations.

Historical Context: The Generational Evolution of CAR-T Therapy

CAR-T technology has evolved through distinct generations, each defined by the complexity of its intracellular signaling domains.

Table 1: Generational Evolution of CAR-T Cell Therapy

| Generation | Signaling Components | Key Features | Clinical Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | CD3ζ only | Limited persistence and efficacy; required exogenous IL-2 [15] | Largely superseded |

| Second | CD3ζ + one costimulatory domain (CD28 or 4-1BB) | Enhanced proliferation, persistence, and cytotoxicity [15] [20] | Six approved products [4] |

| Third | CD3ζ + multiple costimulatory domains | Combined signaling (e.g., CD28+4-1BB); mixed efficacy improvement [15] [20] | Preclinical/clinical investigation |

| Fourth (TRUCKs) | Second-generation base + inducible transgenes | Local cytokine delivery (e.g., IL-12); modified tumor microenvironment [15] [4] | Preclinical/clinical investigation |

| Fifth | Second-generation base + additional membrane receptors | Integrated IL-2R for JAK/STAT activation; enhanced persistence [15] [4] | Preclinical development |

The progression from first to fifth-generation CARs represents an ongoing effort to recapitulate optimal physiological T-cell signaling while overcoming the challenges of the tumor microenvironment. Second-generation CARs remain the most clinically established platform, with all six currently approved CAR-T cell constructs utilizing this design [4].

Structural and Functional Divergence Between CD28 and 4-1BB

Fundamental Signaling Differences

CD28 and 4-1BB originate from different receptor superfamilies and engage distinct signaling pathways despite converging on some common functional outcomes:

- CD28: A member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, CD28 costimulation provides potent amplification of initial T-cell receptor signals primarily through PI3K-AKT pathway recruitment, leading to robust IL-2 production, enhanced metabolic switching to glycolysis, and effector T-cell differentiation [22].

- 4-1BB: A member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, 4-1BB signaling occurs through TNF-receptor-associated factor (TRAF) protein recruitment, activating NF-κB and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative metabolism, and cell survival programs that favor memory formation [22].

These differential signaling patterns establish distinct functional priorities: CD28 prioritizes immediate effector potency, while 4-1BB favors long-term persistence.

Metabolic Programming

Recent research has revealed that CD28 and 4-1BB costimulatory domains impose fundamentally different metabolic profiles on CAR-T cells:

- CD28-CAR-T cells display preferentially glycolytic metabolism, supporting an effector phenotype and increased expansion capacity [23].

- 4-1BB-CAR-T cells show increased reliance on mitochondrial metabolism, preserving mitochondrial fitness and resulting in memory-like differentiation [23].

Despite these differences, T cells in patients responding successfully to therapy were metabolically similar, irrespective of co-stimulator. In non-responders, however, CD28- and 4-1BB-co-stimulated CAR-T cells remained metabolically distinct from each other [23].

Clinical Outcome Correlates: Efficacy and Safety Profiles

Comparative Clinical Performance

Direct comparisons of CD28 versus 4-1BB costimulated CAR-T cells in clinical settings reveal distinct patterns of efficacy and toxicity:

Table 2: Clinical Comparison of CD28 vs. 4-1BB in CD19-Targeted CAR-T Therapy

| Parameter | CD28-based CAR-T | 4-1BB-based CAR-T |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetics of Response | Rapid tumor eradication [22] | Slower, more progressive response [22] |

| Persistence | Short-term to medium-term persistence [22] | Long-term persistence (months to years) [22] |

| Metabolic Phenotype | Effector memory T cells; aerobic glycolysis [20] [23] | Central memory T cells; oxidative metabolism [20] [23] |

| Toxicity Profile | Higher incidence of severe CRS and ICANS [24] | Generally more favorable safety profile [24] |

| Representative Products | Axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta), Brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus) [21] [4] | Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah), Lisocabtagene maraleucel (Breyanzi) [21] [4] |

A 2019 clinical study directly comparing CD28 versus 4-1BB co-stimulated CD19-targeted CAR-T cells in B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma found that while both constructs demonstrated similar antitumor efficacy (complete response rate of 67% within 3 months), their safety profiles differed significantly. The CD28-based CAR-T cohort experienced severe cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), leading to termination of further evaluation of that particular CD28 construct. In contrast, the 4-1BB-based CAR-T cells were well tolerated, even at escalated doses [24].

Architectural Considerations Beyond Costimulation

While much attention has focused on costimulatory domains, other structural elements significantly influence CAR function:

- Hinge/Spacer Region: The hinge region provides flexibility and access to target epitopes. CD28-derived hinges may mediate stronger cytotoxicity compared to CD8α-derived hinges [21].

- Transmembrane Domain: This domain anchors the CAR and can influence expression stability and signaling. CD3ζ transmembrane may enhance activation but reduce stability, while CD28 or CD8α transmembrane domains enhance stability [20].

- ScFv Affinity: The affinity of the single-chain variable fragment affects both efficacy and potential for on-target/off-tumor toxicity, requiring careful optimization [20].

These architectural elements interact with costimulatory domains in complex ways, making direct comparison of CD28 versus 4-1BB challenging when other structural components differ between products [21].

Experimental Methodologies for Comparing Co-Stimulatory Domains

In Vitro Functional Assays

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for directly comparing CD28 and 4-1BB costimulated CAR-T cells:

CAR-T Cell Manufacturing Protocol:

- T-Cell Isolation: Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from leukapheresis product using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation [24].

- T-Cell Activation: Activate T cells using anti-CD3/CD28 magnetic beads or soluble antibodies [24] [20].

- Genetic Modification: Transduce activated T cells with lentiviral or retroviral vectors encoding the CAR construct at an appropriate multiplicity of infection (MOI) [24].

- Expansion Culture: Expand CAR-T cells in culture media supplemented with IL-2 (typically 100-200 IU/mL) for 7-10 days [24].

- Quality Control: Assess CAR expression by flow cytometry, transduction efficiency, and cell viability before cryopreservation or infusion [24].

In Vitro Functional Assessments:

- Cytotoxic Activity: Co-culture CAR-T cells with target cells expressing the antigen of interest at various effector:target ratios (e.g., 1:1 to 20:1). Measure specific lysis using ⁵¹Cr release assays or real-time cell death analysis [20].

- Proliferation Capacity: Label CAR-T cells with CFSE or similar dyes and track dilution upon antigen exposure. 4-1BB CAR-T typically demonstrate superior long-term proliferative capacity [22].

- Cytokine Production: Measure cytokine secretion (IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α) in supernatant by ELISA or multiplex assays following antigen stimulation. CD28 CAR-T typically produce more robust early cytokine responses [20] [22].

- Metabolic Profiling: Assess metabolic phenotype by measuring extracellular acidification rate (glycolysis) and oxygen consumption rate (mitochondrial respiration) using Seahorse Analyzer [23].

In Vivo Modeling

Mouse models provide critical preclinical assessment of CAR-T cell function:

- Tumor Engraftment Models: Establish systemic or subcutaneous tumor models in immunodeficient mice (e.g., NSG mice) [22].

- CAR-T Cell Administration: Inject CAR-T cells intravenously at varying doses and track tumor burden by bioluminescent imaging or caliper measurements [22].

- Persistence Monitoring: Periodically collect blood and tissue samples to quantify CAR-T cell persistence by flow cytometry or qPCR [22].

- Tumor Rechallenge: In persistence studies, rechallenge mice with tumor cells after initial clearance to assess functional memory [22].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CAR-T Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Vector Systems | Lentiviral vectors, Retroviral vectors, Transposon systems | Stable CAR gene delivery to T cells [24] [20] |

| T-Cell Activation | Anti-CD3/CD28 magnetic beads, OKT3 antibody, IL-2 | T-cell activation and expansion during manufacturing [24] |

| Cell Culture Media | X-VIVO 15, TexMACS, RPMI-1640 with human serum | Optimized ex vivo T-cell culture [24] |

| Flow Cytometry Reagents | Anti-murine F(ab')2 fragments, Protein L, target antigen protein | Detection of CAR expression and transduction efficiency [20] |

| Target Cells | CD19+ tumor cell lines (NALM-6, Raji), Artificial APC lines | In vitro functional assays and potency measurements [20] |

| Cytokine Detection | ELISA kits, Luminex multiplex assays, ELISpot | Quantification of CAR-T cell cytokine secretion [20] |

| Metabolic Assays | Seahorse XF Analyzer kits, Mitochondrial dyes | Assessment of metabolic phenotype [23] |

Future Directions and Clinical Translation

The evolution of costimulatory domain optimization continues with several emerging strategies:

- Fine-Tuning Signaling Strength: Novel CAR designs aim to calibrate activation strength to pre-empt T-cell exhaustion while maintaining efficacy [22].

- Alternative Costimulatory Domains: Investigation of ICOS, OX40, CD27, and other domains may provide differentiated functional profiles [20].

- Conditional Activation Systems: Strategies incorporating molecular switches or logic gates to enhance specificity and safety [15] [4].

- Armored CARs: Engineering CAR-T cells to secrete cytokines or express additional receptors to overcome immunosuppressive environments [4] [20].

The choice between CD28 and 4-1BB costimulatory domains ultimately depends on the clinical context, target antigen, and desired balance between immediate potency and long-term persistence. As the field advances toward more sophisticated CAR designs, the foundational principles established through the comparison of these two costimulatory domains will continue to inform next-generation engineering strategies.

The incorporation of costimulatory domains into second-generation CARs represents a breakthrough that enabled the remarkable clinical success of CAR-T therapy. The distinct biological properties imparted by CD28 versus 4-1BB costimulation create complementary therapeutic profiles: CD28 endows CAR-T cells with potent effector function and rapid tumor clearance capacity, while 4-1BB promotes persistent memory-like cells capable of long-term disease control. The optimal choice between these domains depends on specific clinical contexts, disease kinetics, and safety considerations. As CAR-T technology advances through subsequent generations, the foundational understanding of costimulatory signaling continues to inform the design of more sophisticated, effective, and safer cellular therapies for cancer treatment.

The evolution of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a paradigm shift in cancer immunotherapy, driven by successive innovations in synthetic receptor design. First-generation CARs, limited by transient persistence, provided the foundational proof-of-concept for redirecting T-cell specificity. The advent of second-generation CARs, incorporating a single costimulatory domain, markedly enhanced antitumor efficacy and T-cell persistence, leading to groundbreaking clinical successes in hematologic malignancies. However, functional limitations in certain challenging tumor microenvironments prompted the development of third-generation CARs, which integrate multiple cytoplasmic signaling domains (e.g., CD28 plus 4-1BB) within a single construct. This review provides an in-depth technical analysis of the rationale, design, and functional outcomes of third-generation CARs, framing their development within the broader historical trajectory of CAR T-cell engineering. We synthesize quantitative data on their enhanced signaling, detail critical experimental methodologies for their evaluation, and visualize their complex signaling networks, offering a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to overcome the current barriers in cellular therapy.