Taming Contextual Effects: Strategies for Robust Synthetic Genetic Circuits in Biomedical Applications

Synthetic genetic circuits hold transformative potential for biotechnology and medicine, but their predictable design is hampered by pervasive contextual effects.

Taming Contextual Effects: Strategies for Robust Synthetic Genetic Circuits in Biomedical Applications

Abstract

Synthetic genetic circuits hold transformative potential for biotechnology and medicine, but their predictable design is hampered by pervasive contextual effects. These effects—including circuit-host interactions, resource competition, and metabolic burden—compromise circuit performance, stability, and clinical translation. This article provides a comprehensive framework for biomedical researchers and drug development professionals to understand, mitigate, and control these contextual factors. We explore the foundational principles of emergent circuit dynamics, present advanced methodological and computational design strategies, detail troubleshooting and optimization techniques to enhance evolutionary longevity, and examine validation frameworks for clinical application. By synthesizing the latest advances in host-aware and resource-aware design, this review serves as a strategic guide for engineering robust, reliable, and effective genetic circuits for therapeutic interventions.

Understanding the Challenge: How Contextual Effects Undermine Synthetic Circuit Performance

Synthetic biology aims to program living cells with predictable novel functions. However, a core challenge undermining predictability is contextual effects, where a genetic circuit's behavior depends not just on its design but also on its cellular environment. These effects arise from complex, often unintended, interactions between the synthetic construct, the host cell, and the environment [1]. Two of the most significant sources of context-dependence are resource competition and growth feedback [2] [1]. Resource competition occurs when multiple genetic modules within a circuit compete for the cell's finite, shared pools of transcriptional and translational machinery, such as RNA polymerase (RNAP) and ribosomes [2] [3]. Growth feedback describes a mutual inhibition loop where circuit expression imposes a metabolic burden, reducing host cell growth, which in turn alters circuit dynamics through effects like protein dilution [2] [1]. Understanding and managing these intertwined phenomena is essential for advancing robust synthetic biology applications in therapy and biotechnology.

FAQs on Core Concepts

Q1: What are resource competition and growth feedback, and how do they differ?

- Resource Competition is an indirect interaction between genetic modules where one module consumes limited, shared cellular resources (e.g., ATP, RNAP, ribosomes, amino acids) at the expense of another module's expression. This can lead to unexpected outcomes, such as the intended monotonically increasing dose-response curve of an activation cascade becoming biphasic or a winner-takes-all effect in a multi-module circuit instead of the expected co-activation [2] [3].

- Growth Feedback is a multiscale feedback loop between the synthetic circuit and the host cell's growth rate. The expression of the circuit consumes energy and resources, imposing a metabolic burden that reduces the host's growth rate. The slower growth rate, in turn, reduces the dilution of cellular components, thereby altering the concentration and dynamics of the circuit's own products [2] [1].

- Key Difference: While resource competition is a static phenomenon concerning the partitioning of a finite resource pool, growth feedback introduces a dynamic, time-varying interaction that couples circuit performance directly to the physiological state of the cell [1].

Q2: Why do my carefully characterized modules fail to function as expected when assembled into a larger circuit?

This failure is a classic symptom of violated modularity, primarily caused by contextual effects [2]. When characterized in isolation, a module's resource consumption and burden profile are specific to that simple context. Upon assembly, new emergent behaviors arise:

- Resource Competition: The combined modules now compete for the same global resource pool. A highly expressed module can "starve" others, leading to depressed or unexpected outputs [2] [3].

- Growth Feedback: The total metabolic burden of the full circuit is larger than the sum of its parts, leading to a more significant reduction in growth rate. This reduced growth rate decreases dilution, which can non-monotonically affect all module concentrations in the circuit, potentially activating or deactivating them in unpredictable ways [2] [1].

Q3: Can contextual effects ever be beneficial for circuit function?

Yes, recent research shows that what are often considered problematic interactions can be harnessed. A key finding is that growth feedback can confer cooperativity between otherwise competing genetic modules [2] [4]. In a system with two competing genes, an increase in the expression of the first gene (Module 1) can, under certain conditions, lead to a temporary increase in the expression of the second gene (Module 2). This occurs because the burden from Module 1 reduces the growth rate, which slows the dilution rate of Module 2's products, thereby increasing their concentration. This cooperative effect can attenuate the destructive "winner-takes-all" dynamics typically caused by resource competition alone [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unstable or Unpredictable Circuit Output

Symptoms: Circuit performance drifts over time, differs between batch cultures, or does not match model predictions. The output may be highly sensitive to small changes in inducer concentration or growth phase.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Strong Growth Feedback | Measure the correlation between optical density (OD) or growth rate and your output signal (e.g., fluorescence) over time. | - Use weaker promoters or RBSs to reduce metabolic burden [3].- Implement feedback control circuits that can compensate for growth-induced changes [1].- Switch to a more robust host chassis [5]. |

| Resource Competition between Modules | Characterize the dose-response of each module individually and then together. Look for biphasic responses or mutual suppression. | - Decouple modules using genetic insulation devices like "load drivers" [1].- Use orthogonal expression systems (e.g., different sigma factors, T7 RNAP) to create separate resource pools [3] [6].- Fine-tune the expression of each module to balance resource usage [3]. |

Problem 2: Loss of Bistability or Memory in a Switch

Symptoms: A toggle switch or self-activation circuit fails to maintain its state, spontaneously reverting to a default state, or cannot be switched reliably.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Growth-Mediated Memory Loss | Measure the switching efficiency and memory retention in different growth phases (exponential vs. stationary) and in different media. | - Choose a toggle switch topology over a self-activation switch, as it has been shown to be more refractory to growth feedback [7].- Engineer the circuit to be less burdensome [1].- Operate the circuit in slow-growth or stationary-phase conditions. |

| Resource Competition Affecting Feedback Loops | Measure the expression levels of all components in the "ON" and "OFF" states. Check if one node is disproportionately affected. | - Ensure key regulatory proteins are highly expressed and robust. - Use resource-aware modeling to predict and correct for competition effects [2] [1]. |

Problem 3: Inconsistent Performance Across Different Chassis or Growth Conditions

Symptoms: A circuit that works perfectly in one bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli DH5α) fails in another (e.g., E. coli CC118λpir) or in Pseudomonas putida.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Varying Genetic Context & Resource Pools | Quantify circuit performance (transfer function) in all relevant hosts and with different plasmid backbones (low/medium/high copy) [5]. | - Use the Context Matrix framework to systematically map construct-host-environment interactions [6].- Employ broad-host-range parts and backbones [5].- Re-tune the circuit (e.g., promoter/RBS strength) specifically for the new host context. |

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

Quantitative Framework for Growth Feedback and Resource Competition

The following mathematical model integrates both resource competition and growth feedback, providing a framework for analyzing their combined effect [2]. The general ordinary differential equation for a circuit with n genes is:

Where:

xᵢ: Concentration of the product of genei.vᵢ: Maximum expression rate of genei.Rᵢ: Concentration of active promoters for genei.Qᵢ: Parameter representing the capacity of limited resources available for genei's expression (Resource Competition).dᵢ: Degradation rate constant.k_g₀: Base growth rate without burden.Jᵢ: Metabolic burden threshold for genei(Growth Feedback).

Table 1: Key Parameters in the Integrated Host-Circuit Model [2].

| Parameter | Description | Interpretation & Experimental Mapping |

|---|---|---|

| Qᵢ | Resource competition factor | A lower Qᵢ means gene i has a higher load on the shared resource pool. Can be inferred by measuring expression reduction when other genes are introduced. |

| Jᵢ | Metabolic burden threshold | A lower Jᵢ means gene i causes a greater burden per molecule, leading to stronger growth feedback. Can be measured by correlating its expression level with reduction in growth rate. |

| k_g₀ | Basal growth rate | The growth rate of the host cell without any synthetic circuit, measurable via OD600 in minimal medium. |

Condition for Emergent Cooperativity

Model analysis reveals that growth feedback can cause two competing genes to exhibit cooperative behavior under this condition [2]:

This inequality shows that cooperativity is favored when the resource competition factors (Q) are large (low competition) and the metabolic burden thresholds (J) are small (high burden), creating a strong growth feedback that couples the modules' fates.

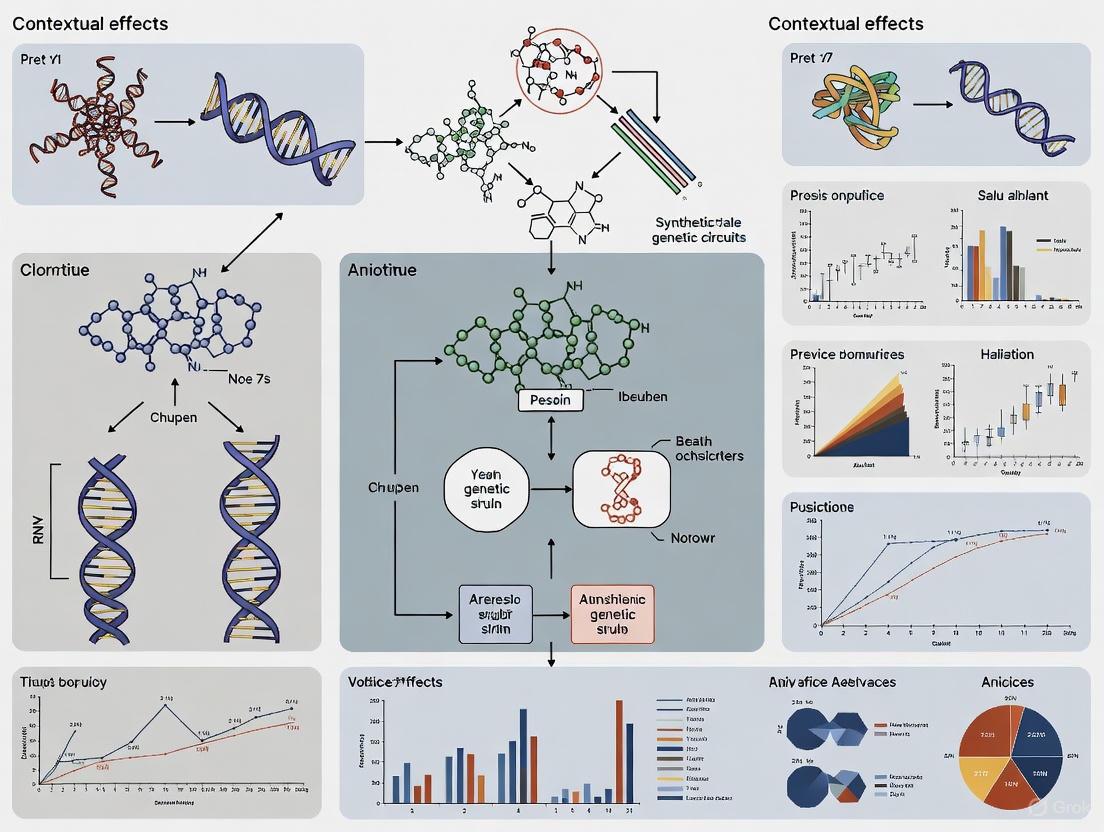

Figure 1: Interplay of Resource Competition and Growth Feedback. Solid lines show the primary initial effects; dashed lines show secondary feedback effects that can lead to emergent cooperativity [2].

Protocol: Characterizing Contextual Effects in a Two-Module Circuit

This protocol allows you to quantitatively assess the strength of resource competition and growth feedback in your system.

Objective: To measure the interaction between two genetic modules (an inducible module and a constitutive module) and parameterize their effect on host growth.

Materials:

- Strain 1: Host containing only the constitutive reporter module (Module 2).

- Strain 2: Host containing both the inducible module (Module 1) and the constitutive reporter module (Module 2).

- Inducer: The molecule that triggers expression of Module 1 (e.g., IPTG, AHL).

- Microplate Reader capable of measuring OD and fluorescence (e.g., for YFP, CFP).

Procedure:

- Inoculate & Induce: Inoculate both strains in triplicate in a 96-well deep-well plate with medium. Add a gradient of inducer concentrations (e.g., 0, 0.1, 1, 10 mM IPTG) to Strain 2. Strain 1 receives no inducer.

- Measure Kinetics: Transfer cultures to a microplate reader. Incubate with shaking and measure OD600 and fluorescence for both reporter channels every 10-15 minutes for 12-24 hours.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the maximum growth rate (

k_g) for each culture from the exponential phase of the OD600 curve. - Calculate the steady-state (or peak) fluorescence expression for Module 2 in all conditions.

- For Strain 2, plot the expression level of Module 2 against the expression level of Module 1 (both at steady-state).

- Plot the growth rate

k_gagainst the expression level of Module 1.

- Calculate the maximum growth rate (

Interpretation:

- Pure Competition: A monotonic decrease in Module 2 expression as Module 1 expression increases.

- Growth Feedback-Cooperation: An initial increase in Module 2 expression as Module 1 expression increases, followed by a decrease at high induction levels. This is accompanied by a measurable decrease in growth rate [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Context-Aware Genetic Circuit Design.

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Broad-Host-Range Vectors (e.g., pSEVA) [5] | Allows testing the same genetic construct across different bacterial species. | Vectors with different origins of replication (low/medium/high copy number) help probe the effect of gene dosage and burden. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins (e.g., YFP, CFP) [5] | Quantitative measurement of gene expression and circuit output. | Use a panel of spectrally distinct fluorophores to monitor multiple modules simultaneously without cross-talk. |

| Orthogonal Regulators (e.g., CRISPRi/dCas9, T7 RNAP) [3] [6] | Creates separate, dedicated resource pools for transcription/translation, mitigating resource competition. | Orthogonality must be validated in your specific host, as cross-talk can occur in new contexts. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems (e.g., LacI/Plac, TetR/Ptet) [3] | Provides precise, tunable control over the expression level of specific circuit modules. | Essential for characterizing dose-response relationships and probing the effects of different expression levels on context. |

| Host-Aware Modeling Software | Computational frameworks that incorporate resource competition and growth feedback equations [2] [1]. | Enables in silico prediction of circuit performance and failure modes before costly experimental implementation. |

Figure 2: The Context-Aware DBTL Cycle. Integrating the Context Matrix framework into the synthetic biology workflow helps systematically navigate and document the impact of construct, host, and environment on circuit function [6].

The Impact of Metabolic Burden on Host Fitness and Circuit Function

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers addressing the impact of metabolic burden in synthetic genetic circuits. The guidance is framed within the broader thesis of understanding and mitigating contextual effects to improve the predictability and robustness of your designs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is "metabolic burden" and why is it a primary concern in synthetic biology applications?

Answer: Metabolic burden is the fitness cost imposed on a host cell by the expression of a synthetic gene circuit. This burden arises from the consumption of the host's finite intracellular resources, such as nucleotides, amino acids, energy (ATP), and transcriptional/translational machinery (RNA polymerases and ribosomes) [1] [8]. It is a primary concern because it can reduce host growth rates, lead to genetic instability, and cause unpredictable or complete loss of circuit function, ultimately derailing applications in biomanufacturing, diagnostics, and therapeutics [8].

FAQ 2: What are the key observable symptoms of high metabolic burden in my bacterial culture?

Answer: The key symptoms are:

- Reduced Growth Rate: A slower specific growth rate (μ) and a longer lag phase [1] [9].

- Decreased Biomass Yield: Lower final optical density (OD) in batch cultures [8].

- Genetic Instability: An increased emergence of mutants that have lost or inactivated the circuit to gain a fitness advantage. This can manifest as a loss of fluorescence or a decline in product formation over time [8].

- Changes in Cell Physiology: A stress-response-like transcriptomic profile and potential activation of stress pathways [8].

FAQ 3: My multi-module circuit is behaving unpredictably. The individual parts work fine in isolation. Could resource competition be the cause?

Answer: Yes. Resource competition occurs when multiple modules in a synthetic biological system compete for a finite pool of shared global resources [1]. This is a major source of context dependence. When modules compete for resources like ribosomes (a primary bottleneck in bacteria) or RNA polymerases (a primary bottleneck in mammalian cells), they can indirectly repress each other's expression in an unanticipated way, leading to emergent and unpredictable system dynamics [1].

FAQ 4: What is "growth feedback" and how does it impact my circuit's dynamics?

Answer: Growth feedback is a multiscale feedback loop where circuit-induced metabolic burden reduces the host's growth rate, and this altered growth rate, in turn, affects the circuit's behavior [1]. A key mechanism is the dilution effect: a slower growth rate reduces the dilution rate of cellular components, including your circuit's proteins and mRNAs. This can fundamentally alter circuit dynamics, for example, by causing the emergence, loss, or shift of bistable states in a genetic toggle switch [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Plasmid-Induced Metabolic Burden

Problem: A drop in host growth rate and circuit performance after introducing or inducing a plasmid-based circuit.

Investigation & Resolution Pathway:

Experimental Protocol for Quantifying Burden

Objective: To quantitatively assess the metabolic burden imposed by your plasmid construct.

Method:

- Strain Preparation:

- Experimental Strain: Host strain carrying your target plasmid.

- Control Strain 1: Host strain carrying an empty plasmid vector.

- Control Strain 2: The wild-type host strain with no plasmid.

- Culture Conditions: Grow all strains in triplicate in appropriate media, with any required inducers for the experimental strain. If using antibiotics for selection, ensure they are used consistently for plasmid-bearing strains.

- Data Collection:

- Measure the optical density (OD₆₀₀) at regular intervals (e.g., every 30-60 minutes) over a sufficient period to capture the entire growth curve.

- For the experimental strain, also sample to determine the plasmid retention rate (e.g., by plating on selective and non-selective media and counting colonies).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the specific growth rate (μ) for each strain during the exponential phase.

- Determine the maximum biomass yield (Xₘₐₓ) for each strain.

- Compare the μ and Xₘₐₓ of the experimental strain to the controls. A significant reduction indicates metabolic burden [9].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Metabolic Burden

| Metric | Formula/Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Growth Rate (μ) | (\mu = \frac{\text{ln}(OD2) - \text{ln}(OD1)}{t2 - t1}) | A lower μ in the recombinant strain indicates a higher burden. |

| Maintenance Coefficient (m) | Determined from relationship between growth rate and energy demand; see [9]. | A higher 'm' value reflects a greater energy demand for non-growth purposes (e.g., plasmid maintenance). An induced recombinant showed m=0.32 g·g⁻¹·h⁻¹ vs. 0.12 for the host [9]. |

| Plasmid Retention Rate | (\frac{\text{CFU on selective media}}{\text{CFU on non-selective media}} \times 100\%) | A low rate indicates high genetic instability due to burden. |

Guide 2: Addressing Inter-Module Interference and Resource Competition

Problem: A complex circuit with multiple modules shows unexpected behavior not observed when modules are tested individually.

Investigation & Resolution Pathway:

Experimental Protocol for Profiling Resource Competition

Objective: To identify if global resource pools are a bottleneck causing interference between circuit modules.

Method:

- Modular Expression Test:

- Construct strains where individual modules are expressed alone.

- Construct a strain where all modules are expressed together.

- Fluorescence Profiling: If modules are tagged with different fluorescent proteins, measure the fluorescence output of each module in both the "alone" and "together" conditions using flow cytometry or a plate reader. Normalize fluorescence to cell density (OD).

- Data Analysis:

- Compare the normalized fluorescence of each module when expressed "alone" versus "together".

- If the output of a module is significantly lower when all modules are co-expressed, this is a strong indicator of global resource competition [1].

- This profiling can be combined with growth rate measurements to understand the coupling between resource usage and host fitness.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Genomic Integration Systems | Mitigates plasmid-related burden and instability by inserting the circuit directly into the host chromosome, eliminating issues like segregation loss [8]. |

| Reduced-Genome Host Strains | Engineered hosts (e.g., E. coli ΔIS elements) with deleted transposable elements and non-essential DNA, resulting in a lower background mutation rate and improved genetic reliability for circuit maintenance [8]. |

| Orthogonal Ribosomes & RNAPs | Engineered transcriptional/translational machinery that operates independently of the host's native systems. They decouple circuit expression from global resource pools, mitigating resource competition [1]. |

| Tunable Promoters | Promoters (e.g., inducible or synthetic promoters of varying strengths) that allow for precise control of gene expression levels, enabling the fine-tuning of circuit activity to minimize burden while maintaining function [1]. |

| "Load Driver" Devices | Genetic devices designed to mitigate the undesirable effects of retroactivity, where a downstream module sequesters signals from an upstream module, by insulating the upstream node [1]. |

Advanced Analysis: Modeling Circuit-Host Interactions

Understanding the coupled dynamics of the circuit, host, and resources is crucial for predictive design. The following diagram and model summarize these interactions.

Mathematical Framework for Failure Dynamics: The emergence and takeover of non-functional mutants can be modeled using a simple population dynamics approach [8]:

[ \begin{align} \frac{dW}{dt} &= (\mu_W - \delta_W)W - \eta \ \frac{dM}{dt} &= (\mu_M - \delta_M)M + \eta \end{align} ]

Where:

- (W) = Population of functional, circuit-carrying cells ("Wildtype")

- (M) = Population of mutant cells that have lost circuit function

- (\muW, \muM) = Specific growth rates of W and M

- (\deltaW, \deltaM) = Specific death rates of W and M

- (\eta) = Rate of mutant emergence (failure rate)

The relative fitness advantage of the mutant is given by (\alpha = \frac{\muM - \deltaM}{\muW - \deltaW}). If (\alpha > 1), mutants will eventually dominate the population. Mitigation strategies thus focus on either reducing the failure rate ((\eta)) or minimizing the relative fitness advantage ((\alpha)) [8].

Core Concepts: Growth Feedback and Circuit Bistability

What is Growth Feedback? Growth feedback is a multiscale interaction where a synthetic gene circuit and the host cell's growth rate reciprocally influence each other. Circuit activity consumes the host's finite transcriptional and translational resources, creating a "cellular burden" that slows the host's growth rate. This reduced growth rate, in turn, changes the circuit's behavior, primarily by altering the dilution rate of cellular components [1].

The Bistability-Growth Feedback Connection Bistability allows a genetic circuit to exist in two distinct, stable steady states (e.g., "ON" and "OFF") under the same environmental conditions, forming the basis for cellular memory and decision-making. Growth feedback can fundamentally alter the number of steady states a system can exhibit [1].

- Emergent Bistability: A self-activation circuit with a noncooperative promoter, which normally shows only one stable state, was found to exhibit bistability. The circuit's high activity imposed a significant burden, slowing growth and dilution. This created two distinct states: a low-expression, high-growth state and a high-expression, low-growth state [10] [1].

- Loss of Bistability: In a classic bistable self-activation switch, growth feedback can increase the protein dilution rate to a point where the production and degradation curves intersect at only one point, eliminating the high-expression "ON" state and resulting in monostable behavior [1].

- Emergent Tristability: Under specific conditions where growth feedback is ultrasensitive, the dilution curve can shift non-monotonically, potentially creating three stable steady states in a self-activation circuit [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Unstable or Unpredictable Circuit Behavior

Problem: Your bistable circuit fails to maintain its state or shows unpredictable switching in a new host strain or growth condition.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Questions | Experimental Checks |

|---|---|---|

| High Cellular Burden | Is the circuit built on a high-copy plasmid? Are potent promoters used? | Measure the host's doubling time when the circuit is active versus inactive. A significant increase indicates high burden [11]. |

| Resource Competition | Does the host strain have limited transcriptional/translational resources? Are other genetic modules present? | Use a constitutive fluorescent reporter as a sentinel. A drop in its expression upon circuit activation indicates resource competition [1]. |

| Insufficient Positive Feedback | Does the circuit's output strongly enough activate its own expression? | Quantify the transfer function of the self-activation promoter. The feedback loop must be strong enough to overcome dilution at high expression levels [10]. |

Resolution Steps:

- Reduce Burden: Switch to a lower-copy plasmid backbone or weaken promoter strengths to lower resource consumption [11].

- Characterize Context: Measure the circuit's transfer function and growth rate impact in your specific host and condition to establish a new baseline [11].

- Model the System: Use a host-aware mathematical model that incorporates growth rate and resource pools to predict new steady states [1].

Guide 2: Addressing Failure in Circuit Portability

Problem: A circuit designed and functioning correctly in one host organism (e.g., E. coli) loses its function when transferred to another host (e.g., Pseudomonas putida).

| Observation | Underlying Issue | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Complete loss of logic function (e.g., NOT gate stops inverting) | The new host context fails to support the required expression levels of the regulatory parts due to differing genetic machinery [11]. | Re-tune the circuit by screening a library of regulatory parts (promoters, RBS) in the new host to re-establish desired expression levels [11]. |

| Significant reduction in dynamic range | The interaction between the circuit and the new host's physiology alters the input-output relationship, compressing the range between "ON" and "OFF" states [11]. | Experiment with different plasmid copy numbers in the new host. A medium-copy plasmid may offer a better compromise between function and burden than a high-copy one [11]. |

| Altered switching thresholds | Host-specific factors, such as basal expression levels or growth rates, shift the point at which the circuit transitions between states [1]. | Use the new host's growth characteristics to inform the re-design. Model how the new dilution rate will affect the circuit's nullclines and adjust feedback strength accordingly [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Growth-Modulated Bistability in a Self-Activation Circuit

This protocol is based on the study where a T7 RNA polymerase-based self-activation circuit exhibited emergent bistability due to growth feedback [10].

1. Objectives

- To quantify the bistable behavior of a self-activation gene circuit.

- To measure the correlation between gene expression states and host growth rates.

2. Materials Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| T7 RNAP* Autogene Circuit | A self-activating genetic circuit where a mutant T7 RNA polymerase (T7 RNAP*) drives its own expression [10]. |

| E. coli Chassis | The host organism for the circuit. Standard lab strains (e.g., DH5α, NEB10β) are suitable [10] [11]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter (e.g., YFP) | A reporter gene placed under the control of the T7 promoter to quantify circuit activity at the single-cell level [10]. |

| Flow Cytometer | Instrument for measuring the distribution of fluorescence (circuit output) across thousands of individual cells. |

| Plate Reader | Instrument for simultaneously measuring population-level fluorescence (circuit output) and optical density (OD600, growth) over time. |

3. Workflow

4. Procedure

- Circuit Construction: Clone the gene for T7 RNAP* under the control of its cognate T7 promoter. Place a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., YFP) downstream of the same or an identical T7 promoter.

- Cell Culture & Sampling: Grow transformed cells in liquid medium. Take samples at various time points throughout the growth phase (lag, exponential, stationary).

- Data Collection:

- Population-Level: Use a plate reader to monitor optical density (OD600) and fluorescence in a culture over time.

- Single-Cell Level: Use flow cytometry to analyze fluorescence from tens of thousands of individual cells in each sample.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot a histogram of fluorescence intensities from flow cytometry data. A bimodal distribution indicates two distinct populations (ON and OFF), evidence of bistability.

- From plate reader data, plot fluorescence versus OD600. A negative correlation suggests that higher circuit output (fluorescence) is associated with slower growth (lower OD600), indicating growth feedback.

Protocol 2: Characterizing Context-Dependent Circuit Performance

This protocol outlines how to test a genetic circuit across different contexts to assess portability and contextual effects [11].

1. Objectives

- To assess the performance robustness of a genetic circuit across different host strains and plasmid backbones.

- To generate data for modeling context-dependent effects.

2. Materials Key additional materials include:

- Alternative Host Chassis: e.g., different E. coli strains (DH5α, CC118λpir) and evolutionarily distant species like Pseudomonas putida [11].

- Plasmid Backbones: Vectors with different origins of replication (e.g., low-copy pSEVA221, medium-copy pSEVA231, high-copy pSEVA251) [11].

3. Workflow

4. Procedure

- Context Library Generation: Clone the same genetic circuit (e.g., a NOT gate) into multiple plasmid backbones with varying copy numbers. Transform these constructs into several different bacterial host strains.

- Transfer Function Characterization: For each context (host-backbone combination), measure the circuit's output (e.g., fluorescence) across a range of input inducer concentrations.

- Data Analysis:

- Dynamic Range: Calculate the difference between the maximum (ON) and minimum (OFF) output levels for each context.

- Qualitative Changes: Note if the circuit's fundamental logic function changes (e.g., a NOT gate loses its inversion property).

- Growth Impact: Correlate the circuit's output levels with the measured growth rate in each context.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Our circuit works perfectly in lab strains but fails in a production strain. Is the design flawed? Not necessarily. The design may be sound but optimized for the wrong context. Circuit performance is deeply intertwined with host physiology [11]. A production strain often has a different genetic background, growth rate, and resource allocation compared to a lab strain. These differences can alter burden, dilution, and resource competition, disrupting a circuit designed for a different context. Troubleshooting should start by characterizing the circuit's transfer function and host growth in the production strain (see Guide 2).

FAQ 2: We observe a wide distribution of expression states in our population. Is this noise or bistability? This is a key distinction. Bistability is characterized by a distinct, bimodal distribution where cells clearly cluster into two separate groups (e.g., low and high fluorescence). Noak typically shows a continuous, often unimodal, distribution around a single mean value. Flow cytometry is the essential tool for distinguishing between them, as it allows you to visualize the distribution of expression across thousands of individual cells [10].

FAQ 3: Can we completely eliminate growth feedback to make a more predictable circuit? It is likely impossible to eliminate growth feedback entirely because circuit activity inherently consumes cellular resources. The goal is not elimination but management and prediction. By adopting a "host-aware" design philosophy, you can model these interactions and design circuits that are robust to them or even exploit them. Using lower-copy plasmids and tuning promoter strength to minimize unnecessary burden are practical steps to reduce the impact of growth feedback [1] [11].

FAQ 4: How does resource competition differ from growth feedback? These are related but distinct concepts:

- Resource Competition: This is a direct, instantaneous effect where multiple genes or modules compete for a limited shared pool of resources (e.g., ribosomes, RNA polymerases). It can cause the output of one module to drop when another is activated, even if the growth rate hasn't yet changed [1].

- Growth Feedback: This is an indirect, slower feedback loop. Resource competition from the circuit leads to cellular burden, which modulates the host's growth rate. The change in growth rate then affects the circuit over time by altering the dilution rate of all cellular proteins, including those in the circuit [1]. In practice, these two interactions are often intertwined.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating Growth Feedback

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Plasmid Systems (e.g., pSEVA) [11] | Allows easy swapping of origins of replication (copy number) and antibiotic markers. | Crucial for systematically testing the effect of gene dosage and burden without redesigning the entire circuit. |

| Broad-Host-Range Vectors [11] | Enables circuit testing in diverse bacterial chassis beyond E. coli. | Essential for assessing circuit portability and generalizability across different physiological contexts. |

| Fluorescent Reporters (e.g., YFP, CFP) [10] [11] | Provides a quantifiable readout of circuit activity at both population and single-cell levels. | Using multiple colors allows for simultaneous monitoring of different circuit modules or a sentinel for resource competition. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems (e.g., lac, ara) [10] [11] | Allows precise external control of gene expression levels to measure transfer functions. | Necessary for characterizing the input-output relationship of the circuit and its dependence on context. |

| Host-Aware Mathematical Models [10] [1] | Computational frameworks that incorporate growth rate and resource pools to predict circuit behavior. | Moves beyond ideal models; helps predict how circuit function will change in a new host or growth condition. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is intergenic context, and why is it a problem for my synthetic gene circuit? Intergenic context refers to the interactions between different genes or genetic parts within a circuit that can unintendedly affect each other's regulation and expression [1]. Unlike isolated parts, genes in a circuit do not operate in a vacuum; their physical arrangement on the DNA can lead to emergent issues like retroactivity and supercoiling-mediated interference, which distort the intended logic and dynamics of your design [1] [12].

Q2: What is retroactivity? Retroactivity is a phenomenon where a downstream module in your genetic circuit (e.g., a gene you are trying to express) interferes with an upstream module (e.g., its activator) by sequestering or modifying the signal that connects them [1]. Imagine a hose feeding two sprinklers; if you turn on the second sprinkler, the water pressure to the first one might drop. Similarly, a downstream gene can "load" the upstream component, reducing its output signal and altering the circuit's performance [1].

Q3: How does DNA supercoiling affect my circuit? As RNA polymerase transcribes a gene, it unwinds the DNA helix. This action creates positive supercoiling (overtwisted DNA) ahead of the polymerase and negative supercoiling (undertwisted DNA) behind it [13]. If two genes are close together, the supercoiling from one gene's transcription can spread and directly influence the transcription of its neighbor [1] [12]. This is a primary mechanism of transcriptional interference, and its effect—whether activatory or inhibitory—depends heavily on the genes' relative orientation [1].

Q4: What are the basic gene orientation syntaxes, and which one is best? There are three primary orientations for two adjacent genes or operons [1]:

- Convergent: The genes are transcribed towards each other.

- Divergent: The genes are transcribed away from each other.

- Tandem: The genes are transcribed in the same direction, one after the other. No single orientation is universally "best." The optimal choice depends on your circuit's function. For instance, convergent orientation has been shown to yield significantly higher gene expression and greater dynamic range in some induced systems, while divergent and tandem orientations can suffer from supercoiling-mediated repression [12].

Q5: What is a practical first step to diagnose supercoiling issues? A direct experimental approach is to treat your cells with a topoisomerase inhibitor, such as a gyrase inhibitor (e.g., novobiocin). Gyrase introduces negative supercoils and relieves positive supercoils. If the aberrant behavior of your circuit is abrogated upon gyrase inhibition, it strongly suggests that DNA supercoiling is a key contributor to the problem [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unanticipated Load from Retroactivity

Symptoms:

- The output of an upstream module (e.g., a transcriptional activator's production rate) decreases when a downstream module is connected.

- The circuit's response dynamics become slower or distorted.

- The expected signal threshold is not met.

Underlying Cause: The downstream module acts as a "load" on the upstream module. For example, if the upstream module produces a transcription factor (TF), and the downstream module contains a promoter with multiple binding sites for that TF, the downstream promoter can sequester a significant fraction of the TF. This leaves fewer TFs available to regulate other targets or to be measured by your reporter system [1].

Solutions:

- Implement a "Load Driver" Device: Incorporate a dedicated genetic device designed to mitigate the impact of retroactivity. These devices act as buffers, insulating the upstream module from the load imposed by the downstream components [1].

- Amplify the Signal: Use a transcriptional or translational amplifier between the sensitive upstream module and the high-load downstream module. This ensures a strong signal is propagated forward, making it less susceptible to sequestration.

- Characterize Part Load: When designing a circuit, characterize the "load" imposed by each part. Prefer parts (e.g., promoters) that have a lower inherent load on shared resources for connections that are particularly sensitive.

Problem: Emergent Behavior from DNA Supercoiling

Symptoms:

- Gene expression levels are highly dependent on the orientation and order of genes on the plasmid or chromosome.

- Expression of one gene strongly represses or activates an adjacent, unrelated gene.

- Circuit behavior is unstable and changes with transcription rates.

- Treatment with a gyrase inhibitor (e.g., novobiocin) significantly alters circuit performance.

Underlying Cause: The transcription of one gene creates waves of positive and negative supercoiling that diffuse along the DNA. These topological changes can alter the energy required for a neighboring promoter to open and initiate transcription, either facilitating it (e.g., through negative supercoiling) or hindering it (e.g., through positive supercoiling) [1] [12] [13].

Solutions:

- Strategic Gene Orientation: Experiment with different gene orientations. For a toggle switch, rebuilding it with genes in a convergent orientation has been shown to improve threshold detection and switch stability by leveraging supercoiling effects [12]. The table below summarizes the general impact of orientation on expression.

| Orientation | Impact on Expression | Mechanism | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convergent | Can yield up to 400% higher expression and greater dynamic range upon induction [12]. | Accumulation of positive supercoiling in the intergenic region can facilitate transcription initiation [1] [12]. | Can enhance mutual inhibition in a toggle switch, improving function [12]. |

| Divergent | Can lead to reduced expression due to transcriptional interference [12]. | Positive supercoiling accumulating between diverging polymerases can inhibit initiation [1]. | May result in stronger repression between adjacent genes. |

| Tandem | Can lead to reduced expression of the downstream gene [12]. | Positive supercoiling from the upstream gene can inhibit the downstream promoter [1]. | Order of genes in a tandem arrangement matters. |

- Use Genetic Insulators: Incorporate genetic insulators, such as transcriptional terminators or "insulator" sequences, between genes. These elements can help block the propagation of supercoiling from one transcriptional unit to the next.

- Leverage Chromosomal Context: If using multi-copy plasmids, be aware that supercoiling effects can be more pronounced. Integrating the circuit into the chromosome at a specific, well-characterized locus can provide a more stable topological environment.

- Direct Supercoiling Measurement: For persistent, complex problems, employ advanced methods like GapR-seq to generate high-resolution maps of positive supercoiling in your specific construct and host. This method uses a bacterial protein (GapR) that preferentially binds overtwisted DNA, allowing for genome-wide mapping via Chromatin Immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) [13].

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Supercoiling with Gyrase Inhibition

Purpose: To determine if DNA supercoiling is a significant factor in your circuit's unexpected behavior.

Reagents:

- Your bacterial strain harboring the synthetic gene circuit.

- An appropriate gyrase inhibitor (e.g., Novobiocin).

- Liquid and solid growth media with necessary antibiotics.

- Inducers for your circuit, if applicable.

- Equipment for measuring output (e.g., plate reader for fluorescence/OD).

Procedure:

- Culture Setup: Inoculate two cultures of your circuit-harboring strain in fresh media.

- Inhibitor Treatment: Once the cultures reach mid-exponential phase (OD600 ~0.3-0.5), add the gyrase inhibitor (e.g., 100 µg/mL novobiocin) to one culture. Add an equivalent volume of solvent (e.g., DMSO) to the other culture as a vehicle control.

- Induction: If your circuit requires induction, add the inducer to both cultures.

- Monitoring: Continue incubating the cultures and measure your circuit's output (e.g., fluorescence) and cell density (OD600) over time.

- Analysis: Compare the output dynamics and final levels between the inhibitor-treated and control cultures. A significant difference in behavior upon gyrase inhibition confirms that DNA supercoiling is a key contextual factor affecting your circuit.

Visual Guide: Supercoiling in Different Gene Orientations

The following diagram illustrates how transcription-induced supercoiling manifests in different gene orientations, based on the twin-domain model [13].

Visual Guide: The Mechanism of Retroactivity

The following diagram illustrates how a downstream module can create a load on an upstream module through retroactivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Investigating Intergenic Context

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Gyrase Inhibitors (e.g., Novobiocin, Ciprofloxacin) | Small molecule inhibitors of DNA gyrase, an enzyme that manages DNA supercoiling. | Used to experimentally perturb supercoiling levels in vivo to test if it is a factor in circuit behavior [12]. |

| GapR Protein & GapR-seq | A bacterial protein that preferentially binds positively supercoiled DNA; used in a ChIP-seq method to map positive supercoiling genome-wide [13]. | For high-resolution mapping of supercoiling distribution in your specific construct and host to identify topological trouble spots. |

| Site-Specific Recombinases (e.g., Cre, Flp, Serine Integrases) | Enzymes that catalyze precise DNA rearrangement, such as inversion or excision of DNA segments [3] [14]. | To create different gene orientations of the same circuit without tedious re-cloning, allowing for rapid testing of orientation effects. |

| Orthogonal Transcriptional Components (e.g., bacterial TFs in plants, CRISPR-dCas9) | Genetic parts that function independently of the host's native regulatory networks [15] [14]. | To minimize unintended cross-talk with the host genome and reduce the host's context-dependent effects on the circuit. |

| SBOL Visual Standards | A graphical language with standardized symbols for genetic designs [16]. | To clearly communicate and document genetic designs, including gene orientations and parts, minimizing ambiguity when troubleshooting or sharing designs with collaborators. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary emergent stochastic sources in synthetic gene circuits? The primary stochastic sources are categorized into two main types of feedback contextual factors:

- Growth Feedback: A multiscale feedback loop where the operation of the synthetic circuit imposes a cellular burden by consuming key resources (like transcriptional/translational machinery), which reduces the host's growth rate. This altered growth rate, in turn, feeds back to influence the circuit's behavior by changing dilution rates and the availability of cellular resources [1].

- Resource Competition: This occurs when multiple modules within a synthetic circuit, or between the circuit and the host, compete for a finite, shared pool of essential resources. The most common forms are competition for translational resources (ribosomes) in bacterial cells and transcriptional resources (RNAP) in mammalian cells. This indirect repression can lead to unexpected coupling and noise in circuit dynamics [1].

FAQ 2: How can circuit-host interactions lead to qualitative changes in circuit behavior? Circuit-host interactions can fundamentally alter the expected behavior of a circuit by modifying its dynamic stability. For instance:

- A self-activation switch designed to be bistable can lose its high-expression ("ON") state due to growth feedback enhancing protein dilution to a point where the production and degradation rates no longer intersect at three points [1].

- Conversely, significant cellular burden from a self-activation circuit can create emergent bistability in a system that would otherwise be monostable, by reducing the growth and dilution rates enough to create two distinct stable states: a low-expression high-growth state and a high-expression low-growth state [1].

FAQ 3: What modeling frameworks are recommended to account for circuit-host coupling?

A host-aware modeling paradigm is essential. A minimal model for a self-activating gene switch coupled to host growth can be described by the following equations, which capture the mutual regulation [17]:

dx/dt = W(g)H(x) - gx (Circuit dynamics)

g = g0[1 - α * W(g)H(x)] (Host growth rate)

Here, x is the protein concentration, g is the host growth rate, H(x) is the intrinsic circuit regulation (e.g., a Hill function), W(g) describes how host growth affects circuit production, g0 is the maximal host growth rate, and α is a loading factor quantifying the burden the circuit imposes on the host [17].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Unexpected Loss or Emergence of Bistability

| Observation | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of the high-expression (ON) state in a bistable switch. | Strong growth feedback increasing dilution rate of circuit components [1]. | Measure the correlation between host growth rate and circuit output expression level across multiple iterations. | - Weaken the promoter strength to reduce burden.- Use a more efficient ribosome binding site (RBS) to lower resource load [1]. |

| Emergence of bistability in a monostable self-activation circuit. | High cellular burden from circuit operation significantly reducing host growth and dilution [1]. | Quantify the growth rate of cells in the putative ON and OFF states to check for differential growth. | - Implement a load driver device to buffer the upstream module from downstream retroactivity [1].- Tune the loading factor (α) by optimizing codons to reduce resource consumption [17]. |

Problem: Increased Cell-to-Cell Variability and Oscillations

| Observation | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High phenotypic heterogeneity in a clonal population. | Resource competition creating stochastic coupling between modules; "winner-takes-all" dynamics [1]. | Use single-cell time-lapse microscopy to track the expression of different fluorescent reporters for each module. | - Decouple modules by using orthogonal RNAPs and ribosomes.- Introduce negative feedback loops to suppress oscillations [1]. |

| Erratic or oscillatory expression output not predicted by deterministic models. | Stochastic effects from intrinsic noise (e.g., low copy number of components) amplified by circuit-host coupling [17]. | Perform single-molecule mRNA FISH to count transcript numbers and quantify intrinsic noise. | - Increase plasmid copy number or use stronger promoters to boost component levels.- Use the Fokker-Planck equation formalism to analyze and predict noise-driven behaviors [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Growth Feedback and Resource Competition

Title: Protocol for Systematically Measuring Circuit-Host Coupling Parameters

Objective: To quantitatively determine the loading factor (α) and production factor (β) for a synthetic gene circuit, enabling predictive modeling of its behavior in a specific host.

Background: The loading factor (α) quantifies how much the circuit's activity burdens the host and reduces its growth. The production factor (β) quantifies how changes in host growth rate affect the circuit's protein production capacity [17].

Materials:

- Strain with the synthetic gene circuit of interest, with an inducible promoter system.

- Control strain with an empty vector or a non-burdening reporter.

- Appropriate culture medium and inducer molecules.

- Spectrophotometer or flow cytometer for measuring optical density (OD) and fluorescence.

- Microplate reader or bioreactor for high-throughput growth monitoring.

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Transform the host with two constructs: (1) your circuit and (2) a constitutive fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP) that is independent of the circuit's logic but acts as a proxy for host resource state.

- Induction Curve: In a 96-well plate, set up a dilution series of the inducer for the circuit. For each concentration, inoculate multiple wells with the circuit strain and the control strain.

- Continuous Monitoring: Place the plate in a pre-warmed microplate reader and initiate a program to cycle between:

- Orbital shaking (to aerate).

- OD600 measurement (for growth rate,

g). - Fluorescence excitation/emission for the circuit's output (e.g., mCherry).

- Fluorescence excitation/emission for the constitutive reporter (GFP).

- Data Collection: Run the experiment for at least 24 hours, collecting data every 10-15 minutes.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate Growth Rate (

g): For each inducer concentration, fit the exponential phase of the OD600 curve to determine the growth rate. - Calculate Protein Production: For each inducer concentration, take the maximum expression level of the circuit output (mCherny) during the exponential phase.

- Plot and Fit:

- Plot growth rate (

g) against circuit output production. The slope of this relationship (at a giveng0) informs the loading factor (α) [17]. - Plot the constitutive reporter (GFP) level against growth rate (

g). The slope of this relationship informs the production factor (β), as the constitutive reporter's expression is dependent on global resource availability [17].

- Plot growth rate (

- Calculate Growth Rate (

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal RNA Polymerases | Reduces transcriptional resource competition by providing a dedicated transcription machinery for the synthetic circuit, decoupling it from host gene expression [1]. | Implementing a T7 RNAP-based expression system in E. coli to insulate circuit genes from host RNAP fluctuations. |

| "Load Driver" Device | A genetic device designed to mitigate the undesirable effects of retroactivity, where a downstream module sequesters signals from an upstream module, enhancing modularity [1]. | Placing a load driver between a sensor module and an actuator module to ensure the sensor's output is not distorted by the actuator's load. |

| Dual-Reporter System | Enables simultaneous monitoring of circuit output and host physiological state (resource availability). A constitutive reporter acts as an internal standard for global cellular capacity [17]. | Using a circuit-driven mCherry and a constitutive GFP to disentangle specific circuit regulation from global resource effects during troubleshooting. |

| Host-Aware Modeling Software | Computational tools (e.g., custom C++, Mathematica) that incorporate equations for circuit-host coupling, moving beyond isolated circuit models to predict emergent dynamics [17]. | Using a Fokker-Planck equation formalism to predict how growth feedback will alter the steady-state probability distribution of a switch at the population level. |

Signaling Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Diagram Title: Circuit-Host Interaction Feedback Loops

Diagram Title: Parameter Quantification Workflow

Diagram Title: Growth Feedback Altering Circuit Stability

Advanced Design Paradigms: Host-Aware and Resource-Aware Circuit Architectures

Synthetic biology aims to program living cells with predictable behaviors using genetic circuits. However, circuit performance is often hampered by context-dependent effects—unintended interactions between the synthetic construct and the host cell environment. Control theory, specifically the implementation of feedback and feedforward loops, provides a powerful framework to mitigate these issues and enhance circuit robustness [1].

These control-embedded designs are fundamental for applications requiring high precision, such as therapeutic drug delivery and sustainable bioproduction, where circuit malfunction can have significant consequences [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Core Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between feedback and feedforward control in genetic circuits?

A1: The core difference lies in how they respond to disturbances:

- Feedback Control is reactive. It measures the output of a system (e.g., the concentration of a protein) and compares it to a desired setpoint. It then calculates an error and adjusts the system's input to correct for any deviation. This is ideal for correcting errors caused by unmeasured or unknown disturbances [18] [19].

- Feedforward Control is proactive. It measures a known disturbance to the system (e.g., a change in growth rate or nutrient level) and preemptively adjusts the system's input to prevent the disturbance from affecting the output. It requires prior knowledge of how the disturbance will impact the system [18] [19].

Q2: Why is my genetic circuit's performance unpredictable across different host strains or growth conditions?

A2: This is a classic symptom of context-dependence, primarily caused by two key feedback contextual factors [1]:

- Resource Competition: Your circuit modules compete with each other and the host's native genes for a finite pool of shared cellular resources, such as RNA polymerases, ribosomes, nucleotides, and amino acids. This competition can lead to unintended coupling and repression between otherwise independent modules [1].

- Growth Feedback: The act of expressing your circuit consumes cellular resources, creating a burden that slows the host's growth rate. This change in growth rate, in turn, alters the circuit's behavior by affecting the dilution rate of cellular components and the cell's physiological state, forming a multiscale feedback loop [1].

Design and Implementation

Q3: When should I use a feedback loop versus a feedforward loop?

A3: The choice depends on the nature of the disturbance and your system knowledge.

- Use Feedback when:

- The source of disturbance is unknown or cannot be easily measured.

- You need to compensate for long-term system drift or degradation.

- A mathematical model of the process is not available [19].

- Use Feedforward when:

- A major, measurable disturbance frequently impacts your system (e.g., a substrate pulse in a bioreactor).

- You have a good understanding of how that disturbance affects your circuit (a process model) [19].

- Feedback alone is too slow, leading to unacceptable performance overshoot or instability.

Q4: Can I combine feedback and feedforward control?

A4: Yes, and this is often the most effective strategy. A combined FF/FB system uses feedforward control to rapidly reject major, known disturbances, while feedback "trim" compensates for inaccuracies in the feedforward model, unmeasured disturbances, and long-term drift. This combination has been shown to improve robustness and dynamic performance in both engineering and biological systems [18] [20].

Q5: What is an Incoherent Feedforward Loop (I1-FFL) and what is it used for?

A5: An I1-FFL is a common network motif in biology. In this three-node structure, an input X activates both an output Z and a repressor Y, which also acts on Z. This creates two opposing pathways: a direct path that activates Z and an indirect, delayed path that represses it [20]. This architecture can perform several functions, including:

- Perfect Adaptation: The system returns to its exact pre-stimulus output level after a response, even under a persistent input signal.

- Pulse Generation: It produces a transient pulse of output activity in response to a steady input.

- Response Acceleration: The output can change more rapidly than it would through a single transcription step [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unstable Circuit Output and Bistability Loss

Symptoms: Circuit output fails to maintain a steady state; expected bistable switch shows only a single state; unpredictable transitions between ON and OFF states.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Strong Growth Feedback Diluting Circuit Components.

- Diagnosis: Monitor both circuit output and host cell growth rate simultaneously. An inverse correlation suggests strong growth feedback.

- Solution: Incorporate a negative feedback loop to regulate the expression rate of key circuit proteins, making the output less sensitive to growth-induced dilution [1]. Use promoters that are less sensitive to growth-rate changes.

- Cause 2: Host Mutations or Evolution.

- Diagnosis: Sequence host genome after prolonged cultivation to identify mutations that alleviate burden.

- Solution: Implement auxotrophic controls or toxin-antitoxin systems in your host strain to reduce its ability to evade circuit function. Use model-predictive control in a chemostat setting to maintain optimal conditions [1].

Problem: Resource Competition Between Modules

Symptoms: Expression of one module inversely correlates with the performance of another; overall circuit performance is weaker than expected from characterized parts.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Competition for Transcriptional/Translational Resources.

- Diagnosis: Measure the impact of expressing a "load module" on the performance of your circuit of interest.

- Solution:

- Decouple Resources: Use orthogonal RNA polymerases and ribosomes that specifically recognize synthetic genetic parts, minimizing competition with host genes [14].

- Implement Feedforward Control: Design a controller that senses the load on resource pools (e.g., by monitoring a sentinel gene's expression) and upregulates resource synthesis or downregulates non-essential circuit functions to compensate [1].

- Cause 2: Retroactivity from Downstream Modules.

- Diagnosis: Isolating a downstream module and observing a change in the upstream module's output.

- Solution: Design a "load driver" device—a buffer-like component that can maintain the upstream signal strength even when a downstream module is connected, thereby insulating modules from each other [1].

Problem: Incoherent Feedforward Loop (I1-FFL) Not Showing Perfect Adaptation

Symptoms: The output of your I1-FFL circuit does not return to its baseline level after a stimulus; the adaptation is incomplete.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Improper Fine-Tuning of Parameters.

- Diagnosis: Perfect adaptation in an I1-FFL is often highly sensitive to specific kinetic parameters (e.g., production and degradation rates of X, Y, Z) [20].

- Solution:

- Mathematical Modeling: Create a quantitative model of your I1-FFL to identify the critical parameters for perfect adaptation.

- Parameter Screening: Systematically vary promoter strengths and RBS sequences for components X and Y.

- Add Negative Feedback: Integrate a negative feedback loop where the output Z represses its own production. This can make the perfect adaptation behavior more robust to variations in component parameters [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantifying Growth Feedback

Objective: To measure the strength of growth feedback on a synthetic gene circuit.

Materials:

- Strains: Host strain containing the genetic circuit and a control strain without the circuit.

- Media: Appropriate growth medium.

- Equipment: Microplate reader or spectrophotometer for OD600 measurement, flow cytometer (if using fluorescent reporters).

Methodology:

- Inoculation: Inoculate triplicate cultures of both the circuit strain and control strain in fresh medium.

- Monitoring: Grow cultures in a microplate reader, measuring OD600 (biomass) and fluorescence (circuit output) every 10-15 minutes.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot growth curves (OD600 vs. time) and circuit output (fluorescence vs. time).

- Calculate the instantaneous growth rate (µ) and plot it against the instantaneous circuit output.

- A strong negative correlation (high output associated with low growth rate) confirms significant growth feedback [1].

Protocol: Implementing a Combined Feedforward/Feedback (FF/FB) Controller

Objective: To build a genetic circuit that combats resource competition using a combined control strategy.

Rationale: The feedforward loop anticipates and mitigates the load, while the feedback loop provides precise setpoint tracking and corrects for model inaccuracies.

The following diagram illustrates the architecture of this combined control system.

Materials:

- Plasmids:

- Feedforward Sensor: A promoter that responds to a global stress signal (e.g., ppGpp) or resource depletion.

- Actuator: A gene that upregulates a limiting resource (e.g., a ribosome synthesis factor) or a orthogonal RNAP.

- Feedback Sensor: A promoter that is sensitive to the specific output of your circuit.

- Circuit of Interest: Your main genetic circuit whose performance needs stabilization.

Methodology:

- Construct the Feedforward Module: Place the resource-upregulating actuator under the control of the feedforward sensor promoter.

- Construct the Feedback Module: Design a controller that compares the output of your circuit (via the feedback sensor) to a desired setpoint and computes an error signal. This could be implemented with a repressor or activator that adjusts the input to your main circuit.

- Integrate Modules: Combine the feedforward module, feedback module, and your main circuit in the same host cell.

- Characterize: Subject the combined system to a known disturbance (e.g., induction of a high-load gene) and measure the stability of the main circuit's output compared to a system with only feedback or no control [18] [20].

Data Presentation

Performance Comparison of Control Strategies

This table summarizes the key characteristics of different control strategies to guide selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Control Strategies for Mitigating Context Dependence

| Control Strategy | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best for Mitigating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feedback [19] | Corrects error based on measured output | • Simple conceptual implementation• Does not require a process model• Robust to unmeasured disturbances | • Corrective action is delayed (reactive)• Can be slow or oscillatory• Theoretically cannot achieve perfect control | Long-term drift, unknown disturbances, noise |

| Feedforward [19] | Preempts error based on measured disturbance | • Potentially faster response (proactive)• Can theoretically achieve perfect rejection of a known disturbance | • Requires an accurate process model• Disturbance must be measurable• Sensitive to model inaccuracies | Large, frequent, and measurable disturbances (e.g., metabolic burden) |

| Combined FF/FB [18] [20] | Feedforward rejects known disturbances; feedback corrects remaining error | • Superior dynamic performance and robustness• Compensates for model inaccuracies | • Increased design complexity | Systems requiring high stability and accuracy |

| Adaptive Control [18] | Automatically adjusts controller parameters over time | • Can compensate for slow system degradation or changing environments• Basis for "artificial intelligence" in control systems | • Highest design complexity• Requires a reference model and monitoring system | Long-running processes, systems that age or change |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Control-Embedded Circuit Design

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal RNA Polymerases [14] | Provides a dedicated transcription machinery that does not compete with host genes, reducing resource competition. | Expressing multiple circuit modules simultaneously without cross-talk. |

| Programmable DNA-Binding Domains (dCas9, ZFPs, TALEs) [14] | Enables the construction of synthetic transcription factors for implementing feedback regulators and feedforward sensors. | Creating a feedback loop where an output protein uses dCas9 to repress its own promoter. |

| Two-Component Systems [14] | Provides a modular sensor-kinase/response-regulator pair for sensing external and internal signals. | Implementing a feedforward loop that senses an environmental disturbance (e.g., pH, metabolite). |

| Site-Specific Recombinases (Cre, Flp, Bxb1) [14] | Enables permanent, digital-like genetic changes to store memory or switch circuit states. | Building a memory device that "records" a past stimulus, a key feature in some adaptive controllers. |

| Degrons (LAA, ssrA tags) [14] | Allows for precise control of protein half-life, a key parameter for tuning the dynamics of feedback and feedforward loops. | Shortening the response time of a repressor protein in an Incoherent Feedforward Loop (I1-FFL). |

| Orthogonal Ribosomes [1] | Provides a dedicated translation machinery, decoupling synthetic gene translation from host demands. | Alleviating translational resource competition, a major bottleneck in bacterial systems. |

Circuit Compression with Transcriptational Programming (T-Pro) to Minimize Burden

FAQs: Core Concepts and Design Principles

Q1: What is circuit compression in synthetic biology, and how does T-Pro achieve it? Circuit compression is the design of genetic circuits that achieve complex computational functions, such as higher-state decision-making, using a significantly reduced number of genetic parts. The primary goal is to minimize the metabolic burden imposed on the host chassis, which becomes a critical constraint as circuit complexity increases. Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) achieves compression by leveraging synthetic transcription factors (repressors and anti-repressors) and their cognate synthetic promoters. Unlike traditional designs that often rely on inverter-based NOT gates, T-Pro utilizes anti-repressors to perform NOT/NOR Boolean operations directly, eliminating the need for multiple cascading promoters and resulting in a smaller genetic footprint [21].

Q2: Why is minimizing metabolic burden so important for genetic circuit performance? Metabolic burden refers to the strain that heterologous gene expression places on a host cell's limited transcriptional and translational resources (e.g., RNA polymerase, ribosomes, nucleotides, energy). This burden can lead to reduced cell growth, unpredictable circuit performance, and even circuit failure. Context-dependent effects, such as resource competition and growth feedback, create complex interdependencies between the circuit and the host [1]. For instance, a burdensome circuit can slow host growth, which in turn alters the dilution rate of cellular components and further affects circuit dynamics. Compressed circuits mitigate these issues by consuming fewer resources, leading to more predictable behavior and robust performance [21] [1].

Q3: What are the main contextual effects that can disrupt a compressed T-Pro circuit? Even compressed circuits are susceptible to contextual effects, which can be categorized as follows [1]:

- Intergenic Context: This includes retroactivity (where a downstream module sequesters signals from an upstream module) and transcriptional interference caused by the relative orientation of genes (e.g., convergent, divergent, tandem) on the DNA. Such interference can be mediated by DNA supercoiling.

- Feedback Contextual Factors: These are system-level phenomena:

- Resource Competition: Multiple genes in a circuit compete for a finite, shared pool of host resources, primarily ribosomes in bacteria and RNA polymerase in mammalian cells. This competition can cause unintended coupling between circuit modules.

- Growth Feedback: A burdensome circuit slows the host's growth rate. The altered growth rate then changes the effective dilution rate of all cellular components, impacting the circuit's output and potentially leading to emergent dynamics like the loss or gain of bistable states.

Q4: What is the quantitative performance of compressed T-Pro circuits? The wetware and software suite developed for T-Pro enables highly accurate quantitative prediction of circuit behavior. On average, multi-state compression circuits are approximately 4-times smaller than canonical inverter-type genetic circuits. Furthermore, quantitative predictions of circuit performance have an average error below 1.4-fold for over 50 tested cases, demonstrating high predictability [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Circuit Performance or Unpredictable Output

Problem: Your compressed circuit is not producing the expected output levels or logic. The expression is weaker than predicted or varies between experiments.

| Potential Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High Metabolic Burden | Measure the host cell's growth rate (doubling time) compared to a control strain without the circuit. A significantly slower growth rate indicates high burden. | Further optimize the circuit design for compression. Weaken RBS strengths to reduce protein expression to the minimum required level [1]. |

| Resource Competition | Test circuit modules in isolation and then together. If co-expression drastically reduces the output of one module, it suggests competition. | Implement an "insulation" strategy, such as using different plasmid backbones with compatible copy numbers or integrating genes into the chromosome to reduce competition [1]. |

| Insufficient Part Orthogonality | Characterize the input-output response of individual TFs and promoters in a simple test setup. Look for crosstalk (e.g., a TF regulating a non-cognate promoter). | Re-screen your library of synthetic transcription factors (e.g., anti-repressors like EA1ADR) to select for variants with higher specificity and dynamic range [21]. |

| Inaccurate Model Parameters | Re-measure the key parameters of your biological parts (e.g., promoter strength, repressor binding affinity) in your specific host strain. | Refine the parameters in your algorithmic design software. The complementary T-Pro software accounts for genetic context; ensure all part data is up-to-date [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Context-Dependent Load

- Transform your host strain with a plasmid containing your circuit and a compatible plasmid expressing a high-level reporter protein (e.g., GFP).

- Transform a control group with the same GFP plasmid and an empty vector control.

- Grow both cultures in triplicate under identical conditions.

- Measure the optical density (OD600) and fluorescence (e.g., GFP) at regular intervals.

- Calculate the relative fluorescence per OD unit for both cultures. A significantly lower GFP output in the circuit-containing strain indicates that the circuit is consuming substantial resources, thereby limiting the expression capacity for the second reporter [1].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting During the Expansion of T-Pro Wetware

Problem: You are engineering a new set of synthetic transcription factors (like the CelR-based TFs) but are not achieving a good dynamic range or proper anti-repressor function.

| Potential Cause | Investigation Method | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Dynamic Range of Repressor | Measure the fluorescence output of the reporter construct in the presence of the synthetic repressor, both with and without its inducing ligand (e.g., cellobiose). | Screen a wider library of repressor variants (e.g., E+ADR). Select for mutants with a low OFF-state (high repression) and a high ON-state (good derepression) as performed for the E+TAN repressor [21]. |

| Ineffective Anti-Repressor | Test the putative anti-repressor variant with its cognate promoter. It should produce high output regardless of the ligand presence. If it acts as a super-repressor (always OFF), the ligand insensitivity is incomplete. | Perform additional rounds of error-prone PCR (EP-PCR) on the super-repressor template at a low mutation rate. Use FACS to screen for clones that exhibit high fluorescence in the presence of the ligand, indicating a successful anti-repressor phenotype [21]. |

| Ligand Permeability or Toxicity | Check cell growth and circuit function across a range of ligand concentrations. | Switch to an alternative, orthogonal ligand or optimize the delivery method for the existing ligand. |

Experimental Protocol: Engineering an Anti-Repressor

- Generate a Super-Repressor: Start with your chosen repressor scaffold (e.g., E+TAN for CelR). Perform site-saturation mutagenesis at key amino acid positions (e.g., position 75) to create a variant that represses the promoter but is no longer inactivated by the ligand (e.g., mutant L75H) [21].

- Create a Variant Library: Use error-prone PCR (EP-PCR) on the super-repressor gene at a low mutational rate to generate a diverse library (~10^8 variants).

- High-Throughput Screening: Use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to screen the library for cells that show high fluorescence (reporter output) in the presence of the ligand, indicating the desired anti-repressor function.

- Validate and Characterize: Isolate unique anti-repressor clones (e.g., EA1TAN, EA2TAN, EA3TAN) and characterize their transfer functions to confirm the anti-repressor phenotype and quantify their performance [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in T-Pro Circuit Development |

|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factors (Repressors/Anti-Repressors) | Engineered proteins that bind to specific synthetic promoters to repress or de-repress transcription. They form the core computational unit of T-Pro circuits. Examples include the IPTG-responsive and D-ribose-responsive sets, and the cellobiose-responsive set built on the CelR scaffold (e.g., E+TAN, EA1TAN) [21]. |