Synthetic Biology and Metabolic Engineering: Advanced Strategies to Boost Actinobacterial Natural Product Titers

Actinobacteria are prolific producers of bioactive natural products, yet their low production titers and silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) present major challenges for drug development and industrial application.

Synthetic Biology and Metabolic Engineering: Advanced Strategies to Boost Actinobacterial Natural Product Titers

Abstract

Actinobacteria are prolific producers of bioactive natural products, yet their low production titers and silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) present major challenges for drug development and industrial application. This article synthesizes the latest synthetic biology and metabolic engineering strategies designed to overcome these bottlenecks. We explore the foundational biology of actinobacterial regulation, detail cutting-edge methodological advances from dynamic pathway control to genome-minimized hosts, provide troubleshooting and optimization frameworks for robust strain performance, and present validation methods for comparative analysis of engineered systems. This comprehensive guide is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to accelerate the discovery and scalable production of high-value therapeutics from actinobacteria.

Unlocking the Silent Majority: Understanding Actinobacteria's Biosynthetic Potential and Regulatory Networks

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Low Titers

1. Why are native actinobacterial production levels insufficient for industrial application? Native production levels are inefficient because in wild-type strains, cellular metabolism is not optimized for producing a single, target compound at high levels. Carbon and energy resources are diverted towards growth and other essential cellular functions, leaving only a small fraction for the biosynthesis of the desired natural product [1]. This results in low titers, rates, and yields (TRY) that are not economically viable for large-scale production.

2. What is the core scientific principle behind overcoming the "Titer Problem"? The core principle is growth-coupled production. This metabolic rewiring strategy makes the production of the target metabolite essential for the microbe's growth and survival. By eliminating (knocking out) specific metabolic reactions, you force the cell to channel carbon and energy into your product pathway to generate biomass or energy, thereby directly linking production with growth [1].

3. We have implemented a growth-coupling strategy, but titers are still low. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge. Key areas to investigate include:

- Incomplete Gene Knockdown/Knockout: Verify the efficiency of your genetic interventions (e.g., CRISPRi) using genomic sequencing and proteomic methods. Incomplete repression of target reactions can create metabolic bypasses.

- Precursor or Cofactor Limitation: Your growth-coupled design may have created a bottleneck. Check the availability of key precursors (e.g., amino acids, acyl-CoAs) and cofactors (e.g., ATP, NADPH) through flux balance analysis (FBA) and metabolomic profiling [1].

- Genetic Instability: The engineered strain might be reverting or losing the heterologous biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC). Ensure stable genomic integration of the BGC and use selection pressure where appropriate [2].

4. How can we make our high-titer lab strain perform consistently in a bioreactor? Scalability is a known hurdle. To improve scale-up success:

- Shift Production to Exponential Phase: Strains engineered for growth-coupled production naturally exhibit this trait, making performance more robust across different growth phases and scales [1].

- Implement Dynamic Regulation: Use metabolite-responsive promoters or biosensors to dynamically control gene expression in response to the physiological state of the culture, preventing metabolic burden during scale-up [2].

- Optimize Process Parameters: At the bioreactor level, closely control dissolved oxygen, pH, and feeding strategies (e.g., fed-batch) to maintain the metabolic state achieved in your lab-scale experiments [1].

5. Beyond gene knockouts, what other synthetic biology tools can boost titer? Several advanced strategies can be integrated:

- BGC Amplification: Increase the copy number of the target biosynthetic gene cluster in the chromosome to elevate gene dosage and pathway flux [2].

- Promoter Engineering: Refactor the native promoters of the BGC with strong, constitutive, or inducible promoters to maximize and precisely control expression [2].

- Utilize Genome-Minimized Hosts: Employ streamlined chassis strains (e.g., Streptomyces hosts with deleted non-essential genomic regions) to reduce metabolic competition and background noise, focusing cellular resources on product synthesis [2].

Experimental Guide: Implementing Growth-Coupled Production

This protocol outlines the genome-scale metabolic modeling and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) approach used to achieve high-level production of indigoidine in Pseudomonas putida, a strategy that can be adapted for actinobacteria [1].

Objective

To computationally design and experimentally construct a microbial strain where the production of a target natural product is obligatorily coupled to growth, thereby significantly increasing titer, rate, and yield (TRY).

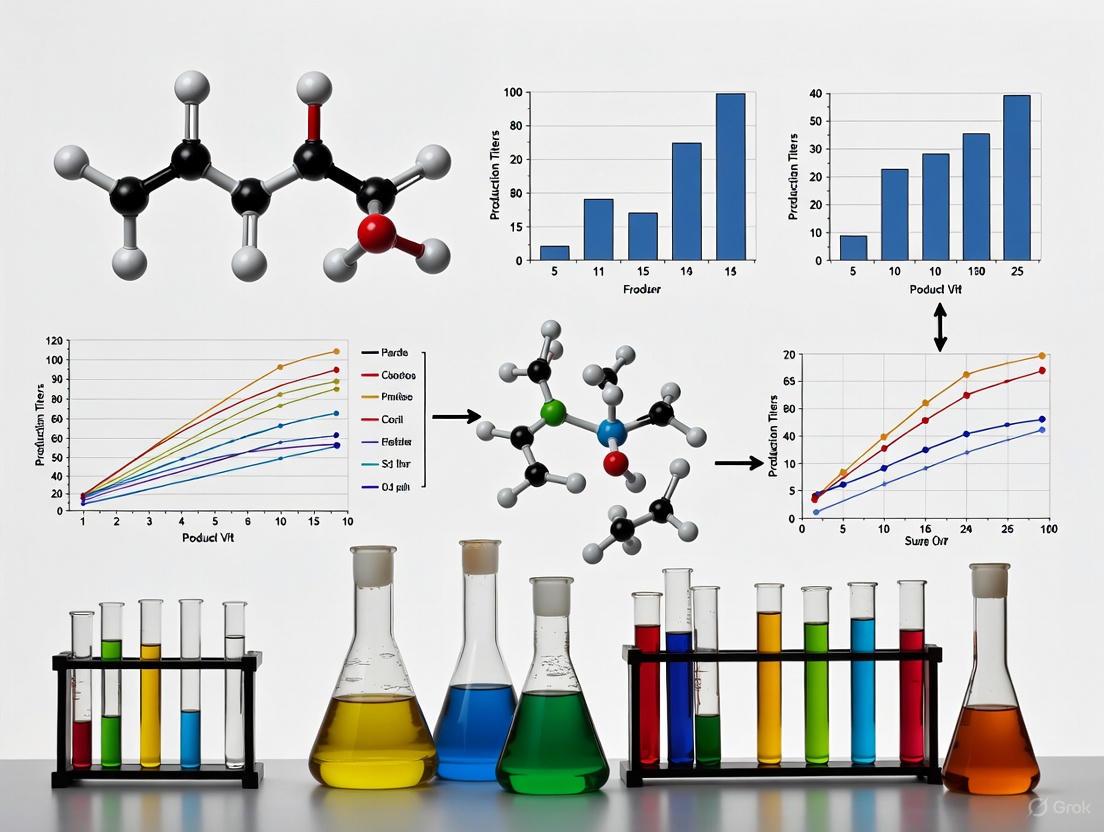

Workflow Diagram

Materials and Reagents

| Category | Item | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GSMM) | In silico representation of organism's metabolism for simulations [1]. |

| MCS Algorithm | Computes minimal reaction sets to eliminate for growth-coupled production [1]. | |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Predicts metabolic flux distributions to optimize growth and production [1]. | |

| Molecular Biology | dCpf1 / CRISPRi System | Enables multiplexed repression of target genes without knockout [1]. |

| gRNA Expression Plasmids | Deliver guide RNAs for targeted gene repression [1]. | |

| Integrative Vectors | For stable genomic integration of heterologous pathways [1]. | |

| Analytical Chemistry | LC-MS / HPLC | Quantifies product titer and yield [3]. |

| GC-MS | Profiles central metabolites and precursors. | |

| Culture Systems | Shake Flasks, Microbioreactors (e.g., ambr) | Lab-scale cultivation and process optimization [1]. |

| Benchtop Bioreactors | Controlled, scaled-up production runs [1]. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: In Silico Model Construction and MCS Calculation

- Model Preparation: Obtain or reconstruct a high-quality genome-scale metabolic model (GSMM) for your production host (e.g., Streptomyces spp.). Add a reaction representing the biosynthesis of your target natural product, including all required precursors and cofactors (e.g., ATP, NADPH) [1].

- Define Constraints: Set the carbon source (e.g., glucose) and the minimum theoretical product yield you wish to enforce (e.g., 80% of the maximum theoretical yield).

- Run MCS Algorithm: Use specialized software (e.g., the MCS tool) to compute all minimal sets of reactions whose elimination forces the cell to produce the target product at the defined yield to achieve growth [1]. This analysis might generate dozens of potential solution sets.

Step 2: Omics-Guided Cut Set Selection

- Filter by Essentiality: Cross-reference the reactions in the MCS solution sets with essential gene data from transposon mutagenesis or gene knockout libraries to avoid targeting genes critical for survival.

- Assess Implementability: Prioritize solution sets that target reactions with single-gene associations and avoid multifunctional enzymes to minimize unintended metabolic disruptions [1].

- Select a Feasible cMCS: Choose one constrained Minimal Cut Set (cMCS) that is experimentally tractable. For example, the indigoidine study selected a set requiring 14 simultaneous reaction interventions [1].

Step 3: Multiplex CRISPRi Strain Engineering

- Design gRNAs: Design and synthesize single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the coding sequences of each of the genes identified in your chosen cMCS.

- Assemble CRISPRi System: Genomically integrate a nuclease-deficient CRISPR system (e.g., dCpf1) under a constitutive promoter. Introduce the pool of sgRNA expression plasmids.

- Verify Repression: Confirm the knockdown efficiency of the target genes using quantitative PCR (qPCR) to measure transcript levels.

Step 4: Lab-Scale Cultivation and Analysis

- Cultivate Engineered Strain: Inoculate your engineered strain and a control strain in shake flasks with the defined medium.

- Monitor Growth and Production: Measure cell density (OD600) and sample the broth at regular intervals throughout the growth cycle.

- Analyze Metabolites: Use LC-MS or HPLC to quantify the titer of your target natural product. Calculate the yield from the carbon source.

- Confirm Growth Coupling: A successful implementation will show product synthesis primarily during the exponential growth phase, unlike native production, which is often stationary-phase specific [1].

Step 5: Scale-Up to Bioreactors

- Transition to Controlled Systems: Transfer the production process from shake flasks to lab-scale (e.g., 2-L) bioreactors.

- Optimize Process Parameters: Implement fed-batch mode with controlled feeding of the carbon source to maintain metabolic activity while avoiding overflow metabolism. Optimize dissolved oxygen, pH, and temperature.

- Evaluate Performance: Assess the final titer, productivity rate, and overall yield. A robust, growth-coupled strain should maintain its high TRY characteristics across this scale transition [1].

Quantitative Data: Industry Standards & Case Study

Table 1: Historical Improvement in Commercial Bioprocess Titers

Data based on an analysis of nearly 40 biopharmaceuticals, focusing on mammalian-cell produced proteins and antibodies. While not from actinobacteria, this illustrates the industry-wide drive for titer improvement that serves as a benchmark for natural product research. [4]

| Timeline | Average Commercial-Scale Titer (g/L) | Key Technological Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| 1985 - Early 1990s | < 0.2 - 0.5 g/L | First recombinant systems, basic media. |

| 2008 - 2014 | ~ 2.56 g/L | Improved expression systems, media optimization, process control. |

| 2019 (Projected) | > 3.0 g/L | Advanced cell line engineering, modeling software, PAT. |

| Near-Future (New Products) | Up to 6 - 7 g/L | Next-generation genetic tools and bioprocessing innovations. |

Table 2: Case Study - MCS Engineering for Indigoidine Production

Performance data for a Pseudomonas putida strain engineered with 14 reaction knockouts via multiplex CRISPRi to enforce growth-coupled production. [1]

| Performance Metric | Native / Baseline Strain | MCS-Engineered Strain | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final Titer | Not specified (low) | 25.6 g/L | Significant |

| Productivity Rate | Not specified | 0.22 g/L/h | Significant |

| Yield (on Glucose) | Not specified | ~50% of theoretical max (0.33 g/g) | Significant |

| Production Phase | Stationary phase | Exponential phase | Critical shift enabling high TRY |

| Scalability | Often lost | Maintained from flasks to 2-L bioreactors | High robustness |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Titer Improvement |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GSMM) | The computational foundation for predicting metabolic interventions (e.g., MCS) to couple production with growth [1]. |

| Multiplex CRISPRi System | Enables simultaneous repression of multiple target genes without DNA cleavage, crucial for implementing complex MCS designs [1]. |

| Biosensor-Driven Dynamic Regulation | Genetic circuits that automatically upregulate pathway flux in response to metabolite levels, reducing metabolic burden and optimizing resource allocation [2]. |

| Integrative Vectors (e.g., Bacteriophage) | Allows stable, single-copy integration of large biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) into the host genome, preventing plasmid loss during scale-up [2]. |

| Genome-Minimized Chassis | A host strain with deleted non-essential genes, reducing metabolic redundancy and competition, thereby channeling resources toward product synthesis [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My BLAST analysis against BGCs is not displaying all gene names, even for perfect matches. What should I check? This is a common issue often related to input formatting or software parameters.

- Cause 1: Input File Errors. Inconsistent or incorrect formatting of gene names in your input file can cause them to be misread or omitted.

- Cause 2: BLAST Parameters. Overly stringent command-line settings, such as a very low e-value threshold, can filter out valid matches. The output format might also be truncating the results.

- Solution: First, verify the formatting of your input file for consistency. Then, review your BLAST command-line arguments, ensuring you are using a comprehensive output format and an appropriate e-value threshold. Finally, check that the BLAST database you are using is up-to-date [5].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the visual alignment of BGCs for comparison? When comparing two BGCs, a poor visual alignment with low percentage identity scores can make analysis difficult.

- Solution: Many BGC visualization tools offer an option to flip or invert the entire gene cluster. This simple action can reorient the sequence, often revealing a much cleaner alignment and higher similarity scores. If your primary tool lacks this feature, you can export the sequence, flip it using a sequence editor, and re-import it for visualization [5].

FAQ 3: The scale bars for my BGC visualizations are inconsistent, making direct comparison impossible. How can I fix this? Inconsistent scaling is a typical visualization challenge that can be resolved through tool settings.

- Solution: To compare gene lengths directly, you must standardize the scale. Use your visualization tool's options to set a fixed scale bar for all BGCs. Alternatively, scale all BGCs relative to a common reference length. Tools like Geneious or CLinker often provide these scaling controls [5].

FAQ 4: What is a key genetic strategy for breaking rate-limiting steps in a BGC pathway? Direct Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) engineering is a powerful synthetic biology strategy to optimize the translation efficiency of each gene within a BGC operon.

- Application: For the violacein biosynthetic cluster (

vioABCDE), researchers used inverse PCR to perform multiple rounds of RBS mutagenesis. This approach successfully broke through predicted pathway bottlenecks, resulting in a 2.41-fold improvement in production titer in E. coli [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Production Titer in a Heterologous Host

A cloned BGC is successfully expressed, but the final metabolite titer is too low for characterization or scale-up.

| Troubleshooting Step | Methodology & Specific Details | Key Outcomes & Quantitative Data |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Dynamic Metabolic Regulation | Implement metabolite-responsive promoters or biosensors to dynamically control gene expression in response to intermediate metabolite levels [2]. | Prevents toxic accumulation of intermediates and optimizes flux; can lead to >10-fold titer improvements in some systems. |

| 2. RBS Engineering | Use site-specific mutagenesis (e.g., inverse PCR, CRISPR-Cas9) to systematically optimize the native RBSs of each gene in the BGC operon [2] [6]. | For violacein, this broke rate-limiting steps and increased yield to 3269.7 µM in optimized batch fermentation [6]. |

| 3. Multi-Copy Chromosomal Integration | Integrate multiple copies of the target BGC into the host chromosome using site-specific recombination systems [2]. | Increases gene dosage and can significantly boost production without the instability of plasmid-based systems. |

| 4. Promoter Engineering & Pathway Refactoring | Replace native promoters with well-characterized, constitutive, or inducible synthetic promoters to rationally control the expression level of each gene [2]. | Refactoring the entire daptomycin BGC through a DBTL cycle resulted in a ~2300% improvement in total lipopeptide titer [7]. |

| 5. Use Genome-Minimized Hosts | Express your BGC in engineered Streptomyces hosts with deleted endogenous BGCs to reduce metabolic burden and background interference [2]. | Provides a "clean" metabolic background that often leads to higher yields and easier detection of the target compound. |

Issue 2: BGC is Not Expressed in a Heterologous Host

The BGC has been cloned and transferred into a host, but no expected product is detected.

- Step 1: Verify BGC Integrity and Cloning. Ensure the entire BGC has been successfully captured without internal rearrangements. For large, complex BGCs with repetitive sequences (e.g., NRPS/PKS), consider partial codon-reprogramming to facilitate error-free cloning [7].

- Step 2: Try Multiple Expression Hosts. BGC expression is highly host-dependent. What works in one strain may fail in another. A multiplexed approach using different hosts like S. albus J1074 and S. lividans can dramatically increase success rates. One study showed that from 70 cryptic BGCs, 24% produced detectable compounds, with activation patterns varying significantly between hosts [8].

- Step 3: Optimize Fermentation Conditions. Systematically optimize culture parameters, which can profoundly impact BGC expression.

- Methodology: Use a "one factor at a time" approach or statistical methods like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to test variables such as temperature, medium composition, and induction timing [9].

- Example: Contrary to previous reports, an RBS-engineered violacein strain in E. coli performed better at 30°C and 37°C than at 20°C, highlighting the need for condition re-optimization after genetic modifications [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Direct RBS Engineering of a BGC via Inverse PCR

This protocol outlines the steps to optimize the translation efficiency of genes within a BGC [6].

1. Principle By mutating the native Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) preceding each gene in an operon, you can modulate the translation initiation rate, thereby balancing the metabolic flux and overcoming rate-limiting steps in the biosynthetic pathway.

2. Reagents and Equipment

- Plasmid containing the entire BGC operon (e.g., pETduet-1 with

vioABCDE). - High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., PrimeSTAR GXL).

- Inverse PCR primers designed to introduce specific mutations into the target RBS region.

- DpnI restriction enzyme (to digest the methylated template DNA).

- Cloning kit (e.g., ClonExpress Ultra One Step Cloning Kit).

- Competent E. coli cells (DH5α for cloning, BL21(DE3) for expression).

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Primer Design. Design inverse PCR primers that are complementary to the region you wish to mutate. The primers should contain the desired RBS sequence mutation at their 5' ends.

- Step 2: Inverse PCR. Use the plasmid containing the BGC as a template. Perform PCR amplification with the high-fidelity polymerase. This creates a linear, amplified product incorporating your mutations.

- Step 3: Template Digestion. Treat the PCR product with DpnI to digest the original, methylated template plasmid.

- Step 4: Recircularization. Use a cloning enzyme to catalyze the self-ligation of the linear PCR product, forming a circular plasmid with the mutated RBS.

- Step 5: Transformation and Screening. Transform the recircularized plasmid into competent E. coli DH5α cells. Isolve plasmids and send for sequencing to confirm the introduction of the correct mutation.

- Step 6: Fermentation and Validation. Transform the verified plasmid into your expression host and measure the production titer compared to the control strain.

Protocol 2: Multiplexed BGC Capture and Heterologous Expression

This high-throughput protocol enables the parallel capture and expression of numerous BGCs from a strain collection [8].

1. Principle Genomic DNA from multiple bacterial strains is pooled and used to create a single, large-insert clone library. A targeted sequencing pipeline (CONKAT-seq) then identifies and locates clones carrying intact BGCs, which are subsequently transferred into heterologous hosts for expression screening.

2. Workflow Diagram: Multiplexed BGC Capture & Expression

3. Key Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| PAC Shuttle Vector | A large-insert cloning vector that can replicate in E. coli and contains the necessary elements for transfer and integration into Streptomyces hosts [8]. |

| Degenerate Primers (e.g., for Adenylation & Ketosynthase domains) | Used to amplify conserved biosynthetic domains from the library pools, enabling the CONKAT-seq tracking and co-occurrence analysis of NRPS and PKS BGCs [8]. |

| S. albus J1074 & S. lividans RedStrep | Engineered Streptomyces heterologous expression hosts known for their "clean" metabolic backgrounds and superior ability to express cryptic BGCs [8]. |

| Triton X-100 | A surfactant used in the chemical preparation of Bacterial Ghost Cells (BGCs) for vaccine development; demonstrates the use of chemical agents to permeabilize bacterial membranes [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Advanced Techniques

1. Self-Supervised Learning for BGC Detection: Traditional BGC detection tools like antiSMASH rely on curated rules and profile HMMs. A newer approach, BiGCARP, uses a self-supervised masked language model. It represents BGCs as chains of functional protein domains (Pfams) and trains a neural network to reconstruct corrupted sequences. This allows it to learn meaningful representations of BGCs, improving the detection of novel clusters and the prediction of their product classes directly from genomic data [11].

2. Selective Isolation of Actinobacteria: Accessing novel BGCs starts with isolating novel actinobacterial strains from diverse habitats.

- Habitats: Primeval forests, hypersaline soils, oceans, plants, lichens, and animal feces harbor unique actinobacterial communities [12].

- Pretreatment: Sample pretreatment (e.g., air-drying, heating, or treatment with chemicals like benzethonium chloride) can selectively eliminate fast-growing bacteria and enrich for actinobacterial spores [12].

- Selective Media: Use media with specific nutrients and inhibitors (e.g., antibiotics, adjusted pH/salinity) to isolate rare or novel actinobacteria, which are the most likely sources of new BGCs [12].

In the quest to improve production titers of bioactive natural products from actinobacteria, understanding cellular regulation is paramount. These Gram-positive bacteria possess a sophisticated multi-tiered regulatory system that controls the biosynthesis of valuable compounds, including antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and anticancer agents. This system integrates broad environmental signals through global regulators while enabling precise pathway-specific control through cluster-situated regulators (CSRs) [13]. The intricate interplay between these regulatory layers ultimately determines the yield of target metabolites, presenting both challenges and opportunities for metabolic engineers and industrial microbiologists. Research has demonstrated that overcoming the limitations imposed by native regulation is often the key to unlocking the full biosynthetic potential of these organisms, with strategies ranging from targeted genetic modifications to comprehensive multi-omics approaches [14] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Silent or Poorly Expressed Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

Problem: Your target BGC shows minimal or no expression under standard laboratory fermentation conditions, resulting in undetectable or very low product yields.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome | Potential Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Verify cluster annotation using antiSMASH and check for the presence of pathway-specific regulatory genes within the BGC. | Identification of potential activator or repressor genes co-localized with the BGC. | Overlooking small or atypical regulatory genes; misannotation of regulatory function. |

| 2. | If a putative CSR activator (e.g., SARP, LAL) is present, construct an overexpression strain using a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., ermE*). | Significant increase (5-fold or more) in transcription of biosynthetic genes and detectable product formation [16]. | Potential metabolic burden or toxicity from unbalanced pathway expression. |

| 3. | If a putative repressor (e.g., TetR, GntR) is identified, perform in-frame deletion of the repressor gene. | Derepression of the BGC and detectable product formation [13]. | Removal of pleiotropic repressors may affect other cellular processes. |

| 4. | If no obvious CSR is identified, overexpress global regulatory genes (e.g., crp, adpA, redD) using an integrative plasmid system. | Approximately 2-fold expansion in accessible metabolic space and potential activation of silent BGCs [15]. | Global regulators may activate multiple clusters simultaneously, complicating analysis. |

| 5. | Apply the "One Strain Many Compounds" (OSMAC) approach by varying cultivation parameters (media, temperature, aeration). | Production of previously unobserved metabolites under optimized conditions [15]. | Time-consuming empirical process with results varying significantly between strains. |

Detailed Protocol for Cluster-Situated Regulator Overexpression:

- Amplify the target regulator gene from genomic DNA using high-fidelity PCR.

- Clone the gene into an appropriate integrative vector (e.g., pSET152 derivative) downstream of the constitutive ermE* promoter.

- Introduce the construct into the wild-type actinobacterial strain via intergeneric conjugation or protoplast transformation.

- Verify integration by PCR and sequence analysis.

- Ferment the overexpression strain alongside the wild-type control in an appropriate production medium.

- Analyze transcript levels of key biosynthetic genes using RT-qPCR with the housekeeping gene hrdB as an internal standard [16]. A significant increase (dozens to hundreds of fold) indicates successful activation.

- Extract metabolites from culture broth with ethyl acetate and analyze by TLC and HPLC-MS to detect new or increased compound production [16].

Troubleshooting Low Titer in Genetically Modified Producer Strains

Problem: Despite successful genetic manipulation to activate a BGC, the final product titer remains suboptimal for industrial application.

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unbalanced metabolic burden | Overexpression of a potent activator draining cellular resources. | Fine-tune expression using a tunable promoter instead of a strong constitutive one. | [13] |

| Inefficient precursor supply | Limited availability of essential CoA precursors (malonyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA). | Engineer primary metabolism to enhance precursor flux; overexpress precursor biosynthesis genes. | [17] |

| Bottleneck in tailoring steps | Rate-limiting post-PKS modifications (glycosylation, oxidation). | Co-overexpress genes encoding bottleneck enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450s, glycosyltransferases). | [17] |

| Inadequate cultivation conditions | Non-optimal medium composition or physical parameters. | Use statistical experimental design (e.g., Response Surface Methodology) to optimize fermentation conditions. | [18] |

| Incomplete regulatory understanding | Undiscovered repressors or hierarchical control. | Employ multi-omics (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to identify additional regulatory nodes [14]. | [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common types of cluster-situated regulators in actinobacteria and how do they function?

A: The most prevalent CSRs belong to distinct protein families with characteristic mechanisms:

- SARP (Streptomyces Antibiotic Regulatory Protein): OmpR-family regulators that function as potent activators, typically binding to direct repeats in promoter regions to enhance transcription. Examples include ActII-ORF4 for actinorhodin and DnrO for daunorubicin [13].

- LAL (Large ATP-binding regulators of the LuxR family): Large regulators that also primarily function as activators of their associated pathways, such as AveR for avermectin [13].

- TetR Family: Typically function as repressors, whose DNA-binding activity is often inhibited by ligand binding, leading to derepression. They frequently control transporter and resistance genes [13].

- LmbU Family: A recently characterized family that can function as both an activator and repressor for different genes within the same cluster, as seen in lincomycin biosynthesis [13].

Q2: How can I identify potential global regulators for overexpression to activate silent BGCs?

A: Successful studies have employed a suite of well-characterized global regulators from model Streptomyces species. Key candidates include:

- Crp (Cyclic AMP Receptor Protein): A central regulator of carbon catabolite control.

- AdpA (A-Factor Dependent Protein A): A key player in the regulatory cascade controlling morphological differentiation and secondary metabolism.

- SARP (e.g., RedD): While some SARPs are cluster-situated, others can have broader regulatory influence.

- SarA (Sporulation and Antibiotics Related gene A): Involved in linking sporulation with antibiotic production. A combinatorial approach of expressing these regulators in native and heterologous hosts has been shown to expand the accessible metabolite space approximately 2-fold [15].

Q3: What multi-omics approaches can help unravel complex regulatory hierarchies?

A: Integrating multiple data layers is crucial for understanding interconnected regulation:

- Genomics & Transcriptomics: Identify BGCs and their expression profiles under different conditions. RNA-seq can reveal co-regulated genes and regulons.

- Proteomics: High-throughput mass spectrometry-based proteomics quantifies protein abundance, revealing key players in regulation that may not be apparent at the transcript level [14].

- Interactomics: Protein-protein interaction networks can identify crucial regulatory hubs that connect primary and secondary metabolism [14].

- Metabolomics: LC-MS/MS profiling of fermentation extracts, analyzed via molecular networking, links regulatory changes to actual metabolic output, identifying both known and novel compounds [15].

Q4: What are the practical steps for linking an orphan biosynthetic gene cluster to its metabolic product?

A: A successful workflow involves:

- Bioinformatic Identification: Use antiSMASH to locate and annotate the orphan BGC of interest.

- Regulator Manipulation: Overexpress putative pathway-specific activators (e.g., LuxR regulators) or delete repressors within the cluster [16].

- Metabolic Profiling: Compare the metabolic extracts of the engineered strain to the wild-type using HPLC-MS and TLC.

- Scale-Up and Isolation: Ferment the promising engineered strain at a larger scale (liters) and isolate the target compounds using chromatographic methods.

- Structure Elucidation: Determine the chemical structure using NMR, HR-MS, and other spectroscopic techniques.

- Genetic Validation: Perform gene knockout or disruption of key biosynthetic genes (e.g., PKS KS domain) to confirm the loss of compound production, definitively linking the cluster to the product [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Genetic Tools for Regulatory Engineering in Actinobacteria

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pSET152-based vectors | ΦC31 attP/int-based integrative plasmids; stable chromosomal integration. | Constitutive expression of cluster-situated regulators (e.g., lmbU, luxR1/luxR2) under ermE* promoter. | [16] |

| Constitutive Promoter ermE | Strong, constitutive promoter derived from erythromycin resistance gene. | Driving high-level expression of activator genes to overcome native repression. | [16] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Targeted genome editing tool for precise gene knockouts or knock-ins. | Disruption of repressor genes (e.g., TetR-family) or introduction of point mutations in regulatory genes. | [19] |

| Global Regulator Plasmid Library | Collection of plasmids overexpressing key global regulators (Crp, AdpA, SarA, etc.). | Broad activation of silent BGCs to expand metabolic diversity in wild-type strains. | [15] |

| Heterologous Hosts (e.g., S. coelicolor, S. lividans) | Engineered model streptomycetes with minimized genomes and reduced native BGC background. | Expression of entire BGCs from rare actinobacteria in a more tractable and predictable host environment. | [2] |

Regulatory Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: Integrated Regulatory Network in Actinobacteria. This diagram illustrates how environmental signals are integrated by global regulators, which in turn influence the activity of cluster-situated regulators (CSRs) to control the expression of biosynthetic gene clusters and ultimately determine natural product yield.

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for BGC Activation. This workflow outlines the key steps from identifying a silent biosynthetic gene cluster to optimizing production of its encoded natural product through genetic and cultivation-based strategies.

Linking Morphological Differentiation to Secondary Metabolism

In the industrial-scale production of bioactive compounds from actinobacteria, a persistent and costly challenge is the inconsistency in product yield. A critical, often overlooked, source of this variation lies in the intricate and often unpredictable relationship between the microorganism's physical development—its morphological differentiation—and its chemical output—secondary metabolism [20] [21]. For researchers and fermentation scientists, observing a high-producing strain in small-scale shake flasks only to have it underperform in large bioreactors is a common frustration. This frequently traces back to a failure to adequately control morphology, which is intrinsically linked to the metabolic pathways that produce valuable therapeutics like antibiotics, anticancer agents, and immunosuppressants [22] [23]. This guide provides a targeted, troubleshooting-focused resource to help you diagnose, understand, and solve the problems that arise at the intersection of morphology and metabolism, thereby enabling more robust and predictable scale-up processes for achieving high production titers.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my actinobacterial strain exhibit high morphological variability between fermentation batches, and how does this impact secondary metabolite production? Batch-to-batch morphological variability is typically driven by inconsistencies in the initial inoculum preparation or subtle variations in the cultivation environment. In actinobacteria, the transition from vegetative (substrate) mycelium to reproductive (aerial) mycelium and spores is tightly coupled with the activation of secondary metabolite gene clusters [20] [21]. Inconsistent morphology directly leads to unpredictable titers because this differentiation process is a key physiological trigger for antibiotic production.

2. What are the most common nutrient-based triggers that simultaneously influence both morphology and secondary metabolism? The most significant nutrient triggers are phosphate, nitrogen, and carbon sources. Phosphate limitation is a classic and powerful signal that represses primary growth and promotes antibiotic synthesis and morphological differentiation [21]. Similarly, the depletion of a preferred nitrogen or carbon source can trigger a metabolic shift towards secondary metabolism and sporulation. Precise control over the type and concentration of these nutrients in your medium is therefore essential.

3. How can I activate 'silent' biosynthetic gene clusters that are not expressed under standard laboratory conditions? Silent gene clusters represent a vast untapped resource. Effective strategies to activate them include the OSMAC (One Strain-Many Compounds) approach, which involves systematically varying cultivation parameters like media composition, aeration, or temperature [22] [24]. Co-cultivation with other microorganisms can also mimic ecological competition and induce silent pathways. Furthermore, modern genome mining can identify these clusters, allowing for targeted genetic or environmental manipulation to trigger their expression [24].

4. When scaling up from flasks to bioreactors, why do yields of target secondary metabolites often drop significantly, and how can morphology management help? Scale-up failure often occurs due to heterogenous conditions in large-scale bioreactors, such as gradients in nutrient concentration, dissolved oxygen, and pH. These sub-optimal conditions can push the culture towards an undesirable morphological state (e.g., excessive pellet formation or fragmented mycelia) that is not conducive to high-level production [21]. Actively controlling parameters to maintain the optimal morphology identified at bench scale is key to a successful tech transfer.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Production Titer Despite High Cell Density

| Observation | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High biomass accumulation but low yield of target secondary metabolite (e.g., antibiotic). | Nutrient repression: Excess phosphate or preferred nitrogen source (e.g., ammonium) in the medium. | - Measure residual phosphate/NH₄⁺ in broth at mid-fermentation.- Analyze transcript levels of pathway-specific regulatory genes (e.g., SARPs). | - Reformulate medium to limit the repressing nutrient.- Use slowly metabolized nitrogen/phosphate sources (e.g., proline, tricalcium phosphate). |

| Lack of morphological differentiation: Culture remains in vegetative growth phase. | - Perform daily microscopic analysis to check for aerial hyphae and spore formation.- Stain for intracellular storage compounds (e.g., polyphosphates, lipids). | - Introduce a controlled nutrient limitation step.- Optimize inoculation density to prevent overly rapid, undifferentiated growth. | |

| Imbalanced metabolic flux: Precursors are diverted towards primary growth, not secondary synthesis. | - Conduct metabolomic profiling of central carbon metabolism intermediates.- Measure activity of key enzymes linking primary and secondary metabolism. | - Engineer or select strains with modulated precursor supply.- Supplement with low levels of specific precursor molecules. |

Problem: Uncontrolled Mycelial Morphology in Bioreactors

| Observation | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation of dense, compact pellets that limit mass transfer. | Inoculum-related issues: Over-aged seed culture or inappropriate spore germination conditions. | - Track inoculum viability and physiological state.- Test different spore pre-germination protocols. | - Standardize inoculum growth phase (e.g., use mid-exponential phase cultures).- Adjust spore concentration for desired pellet size. |

| High shear stress from agitation and aeration. | - Visually assess pellet structure and size distribution.- Correlate morphology with impeller tip speed. | - Optimize agitation speed and aeration rate.- Consider using a different impeller type to reduce shear. | |

| Suboptimal physical-chemical environment (e.g., pH, osmolarity). | - Monitor and profile pH throughout the run.- Test the impact of medium osmolarity on morphology. | - Implement a pH-stat feeding strategy.- Adjust ion concentration and medium composition. |

Problem: Inconsistent Morphology and Titer Between Batches

| Observation | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Significant batch-to-batch variation in both morphology and final product titer. | Genetic instability: Strain degeneration or plasmid loss over serial sub-culturing. | - Plate for single colonies and check for morphological heterogeneity.- Perform genetic analysis (PCR, sequencing) on production strains. | - Implement a rigorous seed train management system with limited sub-cultures.- Use cryopreserved master and working cell banks. |

| Uncontrolled variability in raw materials. | - Conduct a component quality analysis (e.g., trace element analysis).- Run calibration fermentations with a reference medium. | - Secure a consistent supply of critical raw materials (e.g., complex nitrogen sources).- Establish strict quality control specifications for all medium components. |

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Causality

Protocol 1: Linking Morphological Phases to Metabolite Production

Objective: To quantitatively correlate defined morphological stages with the onset and peak of secondary metabolite synthesis in a fermenter.

Methodology:

- Fermentation Setup: Establish a controlled batch fermentation in a bioreactor with online monitoring of dissolved oxygen and pH.

- Systematic Sampling: Aseptically withdraw samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 6-12 hours) throughout the fermentation cycle.

- Morphological Quantification:

- Fix a sub-sample of the broth immediately with a preservative (e.g., formaldehyde).

- Analyze using light microscopy and image analysis software to quantify the percentage of total culture exhibiting: vegetative mycelium, aerial hyphae, and spores.

- Alternatively, use a dry mass ratio of aerial to total mycelium as a quantitative metric.

- Metabolite Analysis:

- Centrifuge the sample to separate biomass from supernatant.

- Analyze the supernatant for the target secondary metabolite using HPLC or LC-MS.

- For intracellular compounds, perform a solvent extraction on the biomass prior to analysis.

- Data Integration: Plot the quantitative morphological data against the metabolite concentration profile over time to identify the precise developmental stage that triggers production.

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact of Phosphate on Differentiation and Production

Objective: To determine the critical phosphate concentration that shifts the culture from growth to production phase.

Methodology:

- Medium Design: Prepare a chemically defined base medium with all essential nutrients except phosphate.

- Phosphate Gradient: Supplement this base medium to create a series of flasks or parallel bioreactors with a gradient of phosphate concentrations (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10 mM).

- Inoculation and Cultivation: Inoculate all vessels with a standardized seed culture and incubate under optimal conditions.

- Monitoring and Analysis:

- Monitor biomass growth (e.g., dry cell weight).

- At stationary phase, harvest and perform both morphological analysis (as in Protocol 1) and metabolite titer analysis.

- Identification of Threshold: Identify the phosphate concentration that yields the optimal balance of adequate biomass and maximal metabolite production, noting the corresponding morphological state.

Visualization: Signaling and Metabolic Pathways

The following diagram synthesizes the key regulatory inputs that connect environmental cues to morphological differentiation and secondary metabolism in actinobacteria.

Figure 1: Regulatory Network Linking Environment, Morphology, and Metabolism

Table 1: Key Reagents for Studying Actinobacterial Differentiation and Metabolism

| Reagent / Resource | Function & Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Humic Acid-Vitamin Agar (HVA) | Selective isolation medium for rare actinobacteria, promoting growth and differentiation [24]. | Used for initial isolation of novel actinobacterial strains from soil samples to access new chemical diversity. |

| Gamma-Butyrolactones | Small signaling molecules that act as quorum-sensing autoinducers, regulating antibiotic production and morphological development [21]. | Added exogenously in small quantities to induce silent secondary metabolite gene clusters in a co-culture. |

| Amberlite XAD-16 Resin | Hydrophobic adsorption resin used for in-situ extraction of secondary metabolites from fermentation broth, stabilizing unstable compounds and facilitating recovery [24]. | Added directly to the bioreactor to capture non-ribosomal peptides as they are produced, preventing degradation. |

| Gellan Gum | A gelling agent used as a substitute for agar in solid media; allows for better diffusion of nutrients and signaling molecules, improving colony differentiation [24]. | Used in plates for morphological observation, often resulting in better sporulation and pigment production compared to agar. |

| Silica Gel 60 | Standard stationary phase for open column chromatography; essential for the initial fractionation of crude extracts during bioassay-guided purification of active compounds [25]. | Used in the first purification step to separate a complex crude extract from a Streptomyces fermentation into distinct chemical fractions for antibacterial testing. |

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers in leveraging genome mining to unlock the vast, untapped biosynthetic potential of actinobacteria and cyanobacteria for natural product discovery. Despite the fact that these microbes possess numerous Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)—with over 80% remaining orphan and uncharacterized in cyanobacteria, and streptomycetes alone containing 20-30 BGCs per genome—achieving high production titers remains a significant bottleneck [26] [27]. This resource provides targeted troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to address the specific challenges you may encounter, from initial bioinformatic analysis to the activation and optimization of silent gene clusters, all within the critical context of improving production yields.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary bioinformatic tool for identifying BGCs, and what is its output? A1: The primary tool is antiSMASH (Antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell). It takes a genome sequence as input and identifies known types of BGCs (e.g., NRPS, PKS, RiPPs, terpenes) by comparing them against a curated database. Its output is a genomic map showing the location, type, and key enzymatic domains of the predicted BGCs, which serves as the starting point for all downstream analysis [28] [27].

Q2: A significant portion of BGCs are "silent" under lab conditions. What are the main strategies to activate them? A2: There are three primary strategies for BGC activation:

- Genetic Manipulation: Using CRISPR-based genome editing to delete repressors, insert strong promoters, or manipulate global regulators that control secondary metabolism [29] [30].

- Co-culture/Elicitation: Culturing the producer strain with other microorganisms (e.g., Mycolic Acid-Containing Bacteria) or adding chemical elicitors to simulate ecological competition and trigger defense metabolite production [31].

- Heterologous Expression: Cloning the entire BGC and expressing it in a well-characterized, genetically tractable host strain (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor) to bypass native regulation and optimize production [26] [30].

Q3: After identifying a promising BGC, how can I prioritize which ones to pursue for improving production titers? A3: Prioritization can be achieved through metabologenomics. This involves correlating the presence of a specific BGC (identified via genome mining) across a collection of strains with the detection of a specific molecular family in their metabolomic profiles (e.g., via LC-MS). A strong correlation suggests the BGC is active and produces a detectable metabolite, making it a high-priority target for titer improvement [32].

Q4: What are the key considerations for heterologous expression to maximize production titers? A4: Critical considerations include:

- Host Selection: Choose a host that is genetically well-characterized, has a high transformation efficiency, and is known to supply necessary precursors. Common hosts include Streptomyces lividans and S. coelicolor [26].

- Vector System: Use a BAC (Bacterial Artificial Chromosome) or cosmic vector capable of carrying large DNA inserts to capture the entire BGC.

- Cluster Refactoring: Replacing native promoters with strong, constitutive ones to ensure high and consistent expression of all biosynthetic genes [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge: Silent or Poorly Expressed BGCs

A very common problem where the target BGC shows no or very low metabolite production under standard laboratory fermentation conditions.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution(s) | Protocol for Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| No product detected via LC-MS, but BGC is present in genome. | Repressive native regulation or lack of ecological cue. | Co-culture with elicitor strains. | 1. Select a partner strain (e.g., Tsukamurella pulmonis TP-B0596) [31].2. Inoculate both the actinobacterial strain and the elicitor strain on the same agar plate or in the same liquid culture medium.3. Monitor metabolic profile changes using HPLC-DAD or LC-MS over 3-7 days. |

| CRISPR-mediated activation. | 1. Identify potential regulatory genes within or near the BGC via antiSMASH annotation.2. Design a CRISPR system to delete a suspected repressor gene or to integrate a strong promoter upstream of the core biosynthetic genes.3. Verify the genetic modification and screen for metabolite production [29]. | ||

| Inconsistent production between replicates. | Unoptimized or undefined culture conditions. | Systematic media engineering. | 1. Test a matrix of different carbon and nitrogen sources.2. Investigate the effect of trace metal ions (e.g., copper) which can act as essential co-factors or morphogenetic signals [33].3. Use statistical design of experiments (DoE) to optimize the key parameters. |

Challenge: Low Production Titers in a Heterologous Host

After successfully cloning and expressing a BGC in a heterologous host, the final product titer remains too low for scaled-up production or comprehensive bioactivity testing.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution(s) | Protocol for Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low yield of target compound in the heterologous host. | Insufficient precursor supply or competing metabolic pathways. | Precursor pathway engineering. | 1. Identify key biosynthetic building blocks (e.g., malonyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA, amino acids).2. Overexpress genes that enhance the flux towards these precursors.3. Knock out genes that divert these precursors into side pathways [29]. |

| Inefficient transcription/translation of the heterologous cluster. | Promoter and RBS engineering. | 1. Replace the native promoters of the BGC with a suite of well-characterized, strong promoters in the host.2. Optimize Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) strength for each gene to balance expression levels. | |

| Host growth impairment or genetic instability. | Toxicity of the intermediate or final product. | Manipulate transporter genes. | 1. Identify and co-express putative exporter genes located within or near the BGC to facilitate product secretion [33].2. This reduces intracellular accumulation and potential toxicity. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Genome Mining and BGC Prioritization Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps from a raw genome sequence to a shortlist of high-priority BGCs for experimental characterization.

Materials:

- Software: antiSMASH [28] [27], BiG-SCAPE [32]

- Input: Assembled genome sequence of the target actinobacterium (FASTA format).

Method:

- BGC Identification: Submit the genome sequence to the antiSMASH web server or run it locally. Use default parameters to identify all putative BGCs.

- Generate Sequence Similarity Network (SSN): Use the BiG-SCAPE tool with the antiSMASH output files as input. BiG-SCAPE will calculate pairwise distances between your BGCs and those in its database, grouping them into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) [32].

- Prioritization by Correlation (Metabologenomics):

- Correlate the genomic presence of specific GCFs across a library of actinobacterial strains with LC-MS metabolomic data from the same strains.

- GCFs that strongly correlate with a specific Molecular Family (MF) are high-priority targets, as this suggests a producer-metabolite link [32].

- Phylogenomic Analysis (Optional): For high-priority GCFs, use the CORASON tool to perform a detailed phylogenomic analysis of the BGCs, which can reveal unique or novel enzymatic features and evolutionary relationships [32].

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

Protocol: Activation of Silent BGCs via Combined-Culture

This protocol details the use of co-culture with Mycolic Acid-Containing Bacteria (MACB) to activate silent BGCs, a method proven to induce the production of novel compounds like alchivemycins and arcyriaflavin E [31].

Materials:

- Strains: Your target actinobacterial strain(s) and the elicitor strain Tsukamurella pulmonis TP-B0596 (or other MACB like Rhodococcus sp.).

- Media: Suitable solid and liquid media for both strains (e.g., ISP-2 agar and broth).

- Equipment: HPLC system equipped with a Diode Array Detector (DAD) or LC-MS.

Method:

- Pre-culture: Independently grow the actinobacterial strain and T. pulmonis in liquid media for 2-3 days to obtain active pre-cultures.

- Inoculation (Solid Co-culture):

- On an agar plate, streak the actinobacterium in a straight line.

- Perpendicular to it, or in a parallel line, streak the MACB elicitor strain.

- Incubate at an appropriate temperature (e.g., 28°C) for 5-14 days.

- Inoculation (Liquid Co-culture):

- Inoculate the actinobacterium into liquid medium.

- Simultaneously or after 24-48 hours, inoculate with the MACB elicitor.

- Incubate with shaking for 5-10 days.

- Metabolic Profiling:

- Extract the culture (both mono-culture and co-culture) with a suitable organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Analyze the extracts by HPLC-DAD or LC-MS.

- Compare the chromatograms of the co-culture with the sum of the mono-cultures to identify metabolites whose production is induced or significantly enhanced.

- Scale-up and Isolation: Scale up the successful co-culture and use activity-guided or UV-signal-guided fractionation to isolate the induced compounds for structural elucidation.

The experimental setup and outcome are summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Tools for Genome Mining and Titer Improvement

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | Bioinformatics tool for the automated identification and annotation of BGCs in genomic data. | Initial genome mining to catalog all BGCs in a newly sequenced actinobacterium [27]. |

| BiG-SCAPE & CORASON | Computational tools for large-scale comparison and phylogenomic analysis of BGCs, grouping them into GCFs. | Prioritizing BGCs by understanding their relationships to known clusters and identifying unique, novel families [32]. |

| CRISPR-BEST | A CRISPR-based genome editing system specifically optimized for Streptomyces. | Efficient knockout of regulatory genes to activate silent BGCs or to delete competing pathways for titer improvement [29]. |

| Mycolic Acid-Containing Bacteria (MACB) | Elicitor strains used in combined-culture to trigger secondary metabolism in actinobacteria. | Activating silent BGCs in hard-to-engineer strains without genetic manipulation [31]. |

| Heterologous Hosts (e.g., S. lividans) | Genetically tractable production chassis that can express heterologous BGCs. | Expressing BGCs from slow-growing or uncultivable bacteria in a high-yielding, controllable system [26] [30]. |

| HPLC-HR-MS | High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry coupled with Liquid Chromatography for metabolomic profiling. | Detecting and characterizing novel metabolites produced upon BGC activation, and for metabologenomics correlation [32] [31]. |

Quantitative Data and Benchmarking

To set realistic expectations for your projects, the table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent genome mining studies.

Table: Quantifying Biosynthetic Potential in Microbial Genomes

| Organism / Study Type | Key Quantitative Finding | Implication for Production Titer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanobacteria (Phylum-wide) | >80% of non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) and polyketide synthase (PKS) BGCs are unassigned to products, representing a vast unexplored resource [26]. | The discovery space for novel compounds is enormous, but connecting a BGC to its product is the critical first step towards titer optimization. |

| Streptomyces spp. (Model actinobacteria) | Genomes contain 20-30 BGCs per strain, far exceeding the number of metabolites typically detected under standard lab conditions [27]. | Significant hidden potential exists within even well-studied strains, requiring activation strategies (e.g., co-culture, genetic engineering) to access this chemical diversity. |

| Combined-Culture Screening | Co-culture of 112 Streptomyces strains with MACB changed the metabolic profile in 97 strains (87%), with 35 strains (31%) showing enhanced production of specific metabolites [31]. | Co-culture is a highly effective and broadly applicable method for activating silent BGCs, providing a fertile starting point for discovering and subsequently optimizing the production of new compounds. |

A Toolkit for Titer Enhancement: From Dynamic Regulation to Host Engineering

FAQs: Troubleshooting Biosensor Implementation in Actinobacteria

Q1: Our metabolite-responsive biosensor shows high background noise (leaky expression) in the absence of the target inducer. What are the primary corrective steps?

- A: Leaky expression is a common challenge. You can address it by:

- Promoter Engineering: Weaken the constitutive promoter controlling the expression of the transcriptional factor itself to reduce intracellular levels and minimize unintended activation [34].

- Operator Site Modification: Fine-tune the affinity between the transcriptional factor and its operator site on the promoter. Altering the sequence or copy number of the operator can reduce unwanted binding and lower background signal [35].

- Transcription Factor Engineering: Mutate the ligand-binding domain of the transcription factor to improve its specificity and reduce the chance of activation by non-target molecules [35].

Q2: The dynamic range of our biosensor is insufficient for effective high-throughput screening. How can we improve the signal-to-noise ratio?

- A: A narrow dynamic range limits the ability to distinguish between high and low producers. Consider these approaches:

- Tune Sensor Components Systematically: As demonstrated in whole-cell biosensor development, simultaneously engineer the promoter of the output module, the operator sequence, and the ligand affinity of the transcription factor module. This multi-pronged approach can significantly enhance the operational and dynamic ranges [35].

- Optimize Genetic Context: Ensure that the genetic parts (promoters, ribosome binding sites) for both the biosensor and the reporter gene are well-matched. A strong promoter for the reporter paired with a moderately expressed transcription factor can often yield a better output [34].

Q3: A biosensor calibrated in a model Streptomyces strain fails when transferred to a wild-type production strain. What factors should we investigate?

- A: Performance variation across strains is frequent. Troubleshoot by checking:

- Host-Specific Interference: The new host may have different native regulatory networks or metabolite pools that interfere with the biosensor's function [2].

- Genetic Instability: Ensure the biosensor construct is stably maintained, especially if it's on a multi-copy plasmid. Using chromosomal integration systems, such as those mediated by Streptomyces bacteriophage integrases, can enhance stability [2].

- Membrane Permeability: Confirm that the target metabolite can adequately enter the cell to interact with the biosensor. Differences in cell envelope composition between strains can affect uptake [36].

Q4: What are the best practices for selecting and characterizing a reporter gene for a biosensor in actinobacteria?

- A: The choice of reporter is critical for sensitive detection.

- For High Sensitivity and Low Background: Luciferase enzymes (e.g., NanoLuc) are excellent due to their extremely low background signal in microbial cells and the availability of cell-permeable substrates. This allows for highly sensitive whole-cell assays [34].

- For Convenience and Versatility: Fluorescent proteins (e.g., yEGFP) are widely used but may have higher background noise from cellular autofluorescence. They require careful measurement using flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy to determine mean fluorescence intensity [34].

- Characterization Protocol: Always perform a time-course experiment with a range of effector molecule concentrations to establish a dose-response curve. This allows you to quantitatively determine the biosensor's dynamic range, sensitivity, and specificity [34].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fine-Tuning Biosensor Performance Using Promoter and Operator Engineering

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to optimize antibiotic-specific whole-cell biosensors in actinobacteria [35].

Objective: To increase the dynamic range and reduce the background of a metabolite-responsive biosensor.

Materials:

- Genetic Tools: A library of synthetic promoters with varying strengths; plasmids for gene expression in actinobacteria.

- Strains: The actinobacterial host strain harboring the biosensor genetic circuit.

- Media: Appropriate liquid and solid fermentation media (e.g., Soybean Mannitol broth, ISP2) [15].

- Equipment: Shaking incubator, spectrophotometer, microplate reader (for fluorescence/luminescence).

Procedure:

- Construct Variants: Generate a suite of biosensor constructs where the promoter controlling the reporter gene (output module) is replaced with promoters from a library with pre-characterized strengths.

- Engineer the Operator: In parallel, create variants with mutations in the transcriptional factor's operator sequence to modulate binding affinity.

- Transform and Cultivate: Introduce the constructed variants into the host actinobacterium. Inoculate cultures and grow them to mid-exponential phase.

- Induce and Measure: Challenge the cultures with a gradient of concentrations of the target metabolite. Incubate for a standardized period.

- Assay Reporter Output: Measure the reporter signal (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) and the optical density of the cultures.

- Calculate Performance Metrics: For each variant, plot the dose-response curve. Calculate the dynamic range (fold-change between induced and uninduced states) and the EC50 (concentration giving half-maximal response).

- Select Optimal Construct: Identify the variant that offers the best combination of high dynamic range, low background noise, and desired sensitivity for your application.

Protocol: Statistical Optimization of Fermentation for Metabolite Production

This protocol outlines the use of Design of Experiments (DoE) to enhance the production of a target metabolite, using uricase production in Streptomyces rochei as a model [37].

Objective: To systematically identify and optimize key fermentation parameters that maximize the yield of a bioactive natural product.

Materials:

- Strain: Actinobacterial production strain (e.g., Streptomyces rochei NEAE-25).

- Fermentation Media: Basal medium (e.g., containing a carbon source, nitrogen source, and salts).

- Analytical Equipment: HPLC system or specific activity assay kits (e.g., for enzyme activity).

Procedure:

- Screening with Plackett-Burman Design:

- Select 10-15 variables to screen (e.g., carbon source, nitrogen source, temperature, pH, medium volume, incubation time, trace elements).

- Set up the fermentation experiments according to the Plackett-Burman design matrix.

- Inoculate and incubate the cultures.

- Harvest and analyze the product titer.

- Statistically analyze the data to identify the most significant variables that positively affect production.

- Optimization with Response Surface Methodology (RSM):

- Take the 2-4 most significant positive variables identified from the Plackett-Burman design.

- Design a Central Composite Design (CCD) experiment to explore the interaction effects between these variables.

- Run the fermentation experiments as per the CCD matrix.

- Measure the product yield for each run.

- Fit the data to a quadratic model and generate contour plots to identify the optimal concentrations/conditions for each variable that predict the maximum product titer.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Different Reporter Systems for Biosensors in Actinobacteria

| Reporter Gene | Detection Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NanoLuc (Nluc) [34] | Luminescence (requires furimazine substrate) | Extremely low background, high sensitivity, ATP-independent, small size (19 kDa) | Substrate (furimazine) can be toxic to some cells | High-throughput screening where maximum sensitivity is required |

| Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., yEGFP) [34] | Fluorescence (requires specific excitation/emission) | No substrate needed, real-time monitoring possible | Cellular autofluorescence can create background noise, sensitive to pH and oxygen | General-purpose applications and spatial localization studies |

| Firefly Luciferase [34] | Luminescence (requires D-luciferin and ATP) | Very high signal intensity, well-established | Large size (~61 kDa), requires ATP, signal can be affected by cellular metabolic state | When a very strong optical output is needed and ATP-dependence is not an issue |

| Optimization Stage | Key Variables Optimized | Original Yield (U mL⁻¹) | Optimized Yield (U mL⁻¹) | Fold-Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plackett-Burman Design (Screening) | 15 variables (e.g., incubation time, uric acid, medium volume) | 16.1 | Not Applicable (Screening Phase) | - |

| Central Composite Design (Optimization) | Incubation time, medium volume, uric acid concentration | 16.1 | 47.49 | ~3.0 |

Visualizations

Biosensor Workflow

Optimization Flow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Engineering in Actinobacteria

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite-Responsive Transcriptional Factors (MRTFs) [34] | Protein switches that bind a small molecule and change their DNA-binding affinity, activating or repressing transcription. | Core component for building a biosensor circuit to detect a specific intracellular metabolite. |

| Synthetic Promoter Libraries [2] [34] | A collection of engineered DNA promoters with a range of defined transcriptional strengths. | Fine-tuning the expression levels of biosensor components or pathway genes to maximize flux and minimize burden. |

| PhiC31 Integrase System [2] | A site-specific recombination system that allows stable chromosomal integration of genetic constructs in actinobacteria. | Creating stable, single-copy biosensors or biosynthetic gene clusters without relying on plasmids. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [38] [39] | Synthetic antibody mimics with cavities tailored for a specific analyte. Used in wearable electrochemical sensors. | Detecting non-electroactive metabolites and nutrients (e.g., amino acids, vitamins) in fermentation broths or sweat for bioprocess monitoring. |

| Plackett-Burman & Central Composite Designs [37] | Statistical experimental designs for efficiently screening and optimizing multiple variables. | Rapidly identifying the most critical media components and environmental factors that influence natural product titer. |

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers employing CRISPR-Cas and PhiC31 integrase systems to improve production titers in actinobacterial natural products research. These tools are pivotal for activating and optimizing silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), offering powerful strategies to unlock Nature's vast chemical repertoire [40].

System Selection Guide

The choice between CRISPR-Cas and PhiC31 integrase depends on your experimental goals. The table below compares their core attributes to guide your selection.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR-Cas and PhiC31 Integrase Systems

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 System | PhiC31 Integrase System |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Targeted gene knockout, editing, and repression [2] | Site-specific, single-copy integration of large DNA constructs [41] [40] |

| Key Strength | High-precision editing; gene disruption [42] | Highly reliable and consistent transgene expression; stable integration [41] [43] |

| Typical Application | Gene knockout, promoter engineering, and BGC refactoring [2] | Stable heterologous expression of BGCs; consistent overexpression of activator genes [40] |

| Editing Outcome | Can generate indels or precise edits via HDR [44] | Unidirectional, irreversible recombination resulting in stable integration [41] |

| Efficiency in Actinobacteria | Highly efficient but highly dependent on transformation efficiency [40] | Broader host range; successful in 21 out of 23 tested actinobacterial strains [40] |

CRISPR-Cas System Troubleshooting FAQ

Q1: How can I minimize off-target effects in my CRISPR-Cas9 experiments? Off-target activity is a common challenge. Several proven strategies can enhance specificity:

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Engineered enzymes like eSpCas9 contain mutations that reduce non-specific binding to DNA, dramatically lowering off-target cuts [42].

- Employ a Cas9 Nickase: Utilize a mutated Cas9 that makes single-strand breaks (nicks). By using two adjacent guide RNAs targeting opposite strands, you can create a double-strand break, significantly raising specificity as two independent binding events are required [44].

- Optimize gRNA Design: Carefully design guide RNAs with highly specific sequences. Utilize online algorithms to predict potential off-target sites. Ensure the 12-nucleotide "seed" region adjacent to the PAM sequence is unique to your target [45] [44].

- Titrate Components: The amount of Cas9 and sgRNA can be titrated to optimize the on-target to off-target cleavage ratio. However, this may also reduce on-target efficiency and requires careful balancing [44].

Q2: What should I do if I observe low editing efficiency? Low efficiency can stem from multiple factors. Consider these solutions:

- Verify gRNA Design and Delivery: Test 3-4 different gRNA target sequences to find the most effective one. Ensure your delivery method (electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors) is optimal for your specific actinobacterial host [45] [44].

- Check Component Expression: Confirm that the promoters driving Cas9 and gRNA expression are functional in your host. Codon-optimization of the Cas9 gene for your host organism can significantly improve expression levels [45].

- Utilize Enrichment Strategies: Increase the proportion of modified cells by employing antibiotic selection or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) after modification [44].

Q3: My experiments are resulting in high cell toxicity. How can I mitigate this? Cell toxicity is often linked to the high concentration or prolonged expression of CRISPR components.

- Optimize Delivery Concentration: Start with lower doses of CRISPR-Cas9 components and titrate upwards to find a balance between effective editing and cell viability [45].

- Use Alternative Delivery Methods: Delivering pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes can shorten the exposure time and reduce toxicity compared to plasmid-based delivery [45].

PhiC31 Integrase System Troubleshooting FAQ

Q1: Why should I choose PhiC31 integrase for activating natural product synthesis in actinobacteria? PhiC31 integrase is an exceptionally robust tool for stable genetic engineering in actinobacteria. A key study demonstrated that an integration vector (pSET152) was successfully integrated into 21 out of 23 unique actinobacterial strains tested, showing a broader host range and higher success rate compared to a CRISPR-Cas system (pCRISPomyces-2) under the same conditions [40]. This reliability makes it ideal for introducing activator genes across diverse native strains.

Q2: How do I achieve consistent transgene expression with PhiC31? The PhiC31 system enables site-specific integration of your transgene into a pre-determined genomic "landing site" (attP). This ensures that every successful recombination event places the transgene in the same genomic context, which minimizes position effects that cause variable expression—a common problem with random insertion methods [41]. This results in predictable and consistent expression levels across different transgenic lines.

Q3: What is a proven experimental workflow for using PhiC31 for strain activation? A robust, multi-pronged activation strategy using PhiC31 has been successfully applied to 54 actinobacterial strains, nearly doubling the accessible metabolite space [40] [15]. The workflow is as follows:

- Step 1: Plasmid Construction. Generate a PhiC31 integration plasmid (e.g., based on pSET152) containing an "activator" gene of interest under the control of a strong constitutive promoter like kasO*p [40].

- Step 2: Strain Transformation. Introduce the plasmid into the target actinobacterial strain via conjugation.

- Step 3: Integration. The PhiC31 integrase catalyzes irreversible recombination between the plasmid's attB site and a genomic attP site (or a native pseudo-attP site), resulting in stable integration of the entire plasmid [41] [40].

- Step 4: Cultivation and Analysis. Ferment the generated mutants in 3-5 different media to apply "one strain many compounds" (OSMAC) conditions. Analyze the fermentation extracts using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to profile metabolic changes [40] [15].

Q4: Which "activator" genes should I use to improve natural product titer? The multi-pronged activation study successfully used a library of five key regulators [40]:

- Global Regulators: Crp (cyclic AMP receptor protein) and AdpA (A-factor dependent protein A) to modulate primary/secondary metabolic balance and sporulation.

- Pathway-Specific Activators: SARPs (Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory proteins, e.g., RedD) to directly upregulate specific biosynthetic pathways.

- Metabolic Flux Enhancers: FAS (fatty acyl CoA synthase) to mobilize triacylglycerol flux for increased antibiotic production.

Combined and Advanced Applications

The TICIT Approach: A novel method combines the strengths of both systems. "Targeted Integration by CRISPR-Cas9 and Integrase Technologies" (TICIT) uses CRISPR-Cas9 to first knock a minimal 39-bp PhiC31 landing site (attP) into a precise genomic locus. The PhiC31 integrase is then used to repeatedly insert large DNA fragments (e.g., reporter genes) at this pre-defined site with high efficiency and precision [43]. This facilitates consistent transgene expression and enables applications like instantaneous visual genotyping in zebrafish, a strategy that could be adapted for microbial hosts.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and their functions as featured in the cited research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 (eSpCas9) | Reduces off-target editing effects through engineered mutations [42] | Achieving more specific gene knockouts in actinobacteria. |

| PhiC31 Integrase & pSET152 Vector | Enables stable, site-specific genomic integration in actinobacteria [40] | Constitutively expressing activator genes (e.g., Crp, AdpA) in native strains. |

| Activator Gene Library (Crp, AdpA, SARP, FAS) | Globally perturbs and upregulates silent or low-yielding secondary metabolites [40] | Multi-pronged activation strategy to expand accessible metabolite space. |

| TICIT System | Enables repeated, precise transgene integration into a CRISPR-knocked-in landing site [43] | Creating consistent reporter lines and facilitating visual genotyping. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide for Pathway Refactoring

Table 1: Common Issues and Solutions in Pathway Refactoring

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low or no product titers after BGC refactoring. | Use of weak or incompatible native promoters. | Replace native promoters with a suite of strong, synthetic modular regulatory elements to unlock microbial natural products [2]. | |

| Unstable expression or genetic instability of the refactored pathway. | Inefficient chromosomal integration. | Utilize Streptomyces temperate bacteriophage integration systems for stable genetic engineering of actinomycetes [2]. | |