Stabilizing Synthetic Microbial Communities: Strategies to Mitigate Reduced Interactions for Biomedical Applications

This article addresses the critical challenge of mitigating reduced interactions in multi-species synthetic communities, a key obstacle in translating laboratory-designed consortia to reliable biomedical and biotechnological applications.

Stabilizing Synthetic Microbial Communities: Strategies to Mitigate Reduced Interactions for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

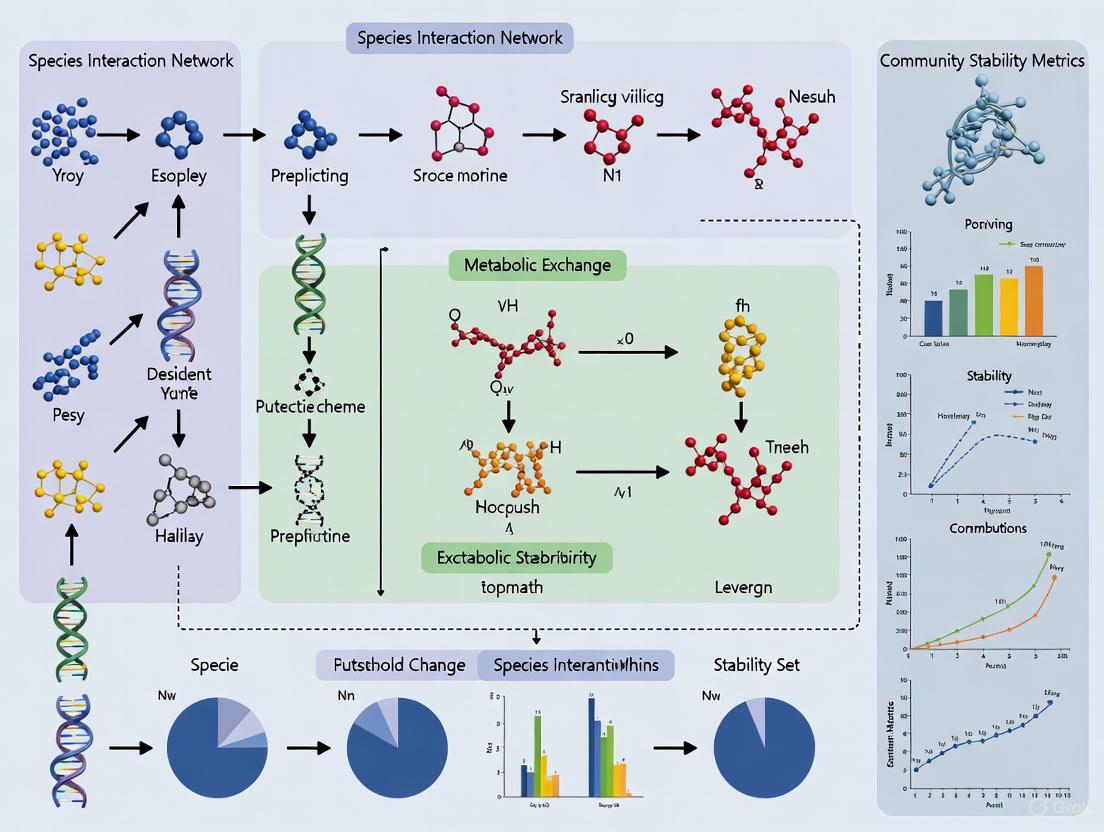

This article addresses the critical challenge of mitigating reduced interactions in multi-species synthetic communities, a key obstacle in translating laboratory-designed consortia to reliable biomedical and biotechnological applications. For researchers and drug development professionals, we synthesize foundational ecological principles with advanced engineering strategies, covering the design of robust intercellular interactions, optimization techniques to enhance community stability, troubleshooting for functional persistence, and validation through computational and experimental models. By integrating the latest research on metabolic modeling, higher-order dynamics, and combinatorial optimization, this resource provides a comprehensive framework for constructing stable, predictable microbial ecosystems for therapeutic production, biocontrol, and understanding host-microbe interactions.

The Ecology of Synthetic Communities: Understanding Interaction Networks and Stability Principles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main types of species interactions I might observe in my synthetic community experiment? The primary interaction types are Competition, Predation/Herbivory, and Symbiosis, which includes mutualism, commensalism, and parasitism [1] [2]. In mutualism, both species benefit from the interaction. In commensalism, one species benefits while the other is unaffected. In parasitism, one species benefits at the expense of the other [1]. Competition involves individuals vying for a common resource that is in limited supply, negatively affecting the weaker competitors. Predation occurs when one individual (the predator) kills and eats another (the prey) [2].

Q2: Why might the expected interactions in my synthetic community (SynCom) not manifest in experimental results? Expected interactions may not manifest due to several factors:

- Inappropriate Community Assembly: The selected strains may not accurately capture the functional diversity or ecological niches of the target ecosystem, leading to reduced or absent interactions [3].

- Insufficient Characterization: A lack of prior in silico validation (e.g., using genome-scale metabolic models) to predict potential cooperative or competitive interactions between strains [3].

- Experimental Conditions: Suboptimal growth media, temperature, or physical environment that does not support the specific requirements for the interactions to occur.

- Contamination: The introduction of unintended microbial species can disrupt delicate, planned interactions within the SynCom [4].

Q3: My SynCom is showing much lower diversity and stability than anticipated. What could be the cause? Reduced diversity and stability often stem from competitive exclusion, where a superior competitor eliminates an inferior one by outcompeting it for resources [2]. This can happen if:

- The SynCom lacks functional redundancy or cross-feeding relationships that promote stability.

- Interference competition occurs, where one strain directly alters the resource-attaining behavior of another [2].

- The community design does not account for apparent competition, where two strains that do not directly compete for resources negatively affect each other by both being a resource for the same predator or phage [2].

Q4: How can I troubleshoot a synthetic community that fails to induce a specific host phenotype? First, verify that your SynCom is functionally representative of the donor ecosystem. A taxonomy-based selection might miss key functional genes [3]. Ensure the community is stable and all members are present at the time of host exposure. Check for the presence of known effector metabolites or functions that are differentially enriched in the phenotype of interest using weighted functional profiling during community design [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpected Competitive Exclusion in SynCom

Symptoms: One or two microbial strains dominate the culture, leading to a rapid loss of other community members.

Investigation and Solutions:

| Investigation Step | Protocol & Methodology | Expected Outcome & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Identify Competition Type | Conduct paired growth experiments in a shared medium versus individual cultures. Analyze growth curves and resource depletion [3]. | A significant growth reduction in co-culture suggests exploitation competition. Direct inhibition suggests interference competition [2]. |

| In Silico Metabolic Modeling | Use genome-scale metabolic models (e.g., with tools like BacArena or GapSeq) to simulate growth of community members in a shared nutrient environment [3]. | Predicts potential for resource competition and identifies specific nutrients in conflict before wet-lab experiments. |

| Modulate Disturbance Regime | Introduce controlled disturbances (e.g., periodic dilution, nutrient pulsing) based on the intermediate disturbance hypothesis [2]. | Prevents competitive exclusion by creating opportunities for weaker competitors (often better dispersers) to regrow, fostering coexistence [2]. |

Problem: Loss of Mutualistic or Cooperative Interactions

Symptoms: A decline in the overall function or productivity of the SynCom that cannot be explained by the loss of a single species.

Investigation and Solutions:

| Investigation Step | Protocol & Methodology | Expected Outcome & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Verify Metabolic Cross-Feeding | Use genome-scale metabolic modeling to identify potential cooperative interactions, such as cross-feeding, prior to SynCom construction [3]. | Provides in silico evidence for cooperative strain coexistence. A positive score indicates a higher likelihood of successful cooperation. |

| Profile Spent Media | Grow potential mutualistic strains individually, then culture other strains in the filtered "spent" media. Monitor growth compared to fresh media controls. | Enhanced growth in spent media indicates the presence of beneficial metabolites (e.g., vitamins, amino acids) produced by the first strain, confirming cross-feeding. |

| Re-engineer Community Composition | If a key mutualist is lost, use a function-based selection pipeline (e.g., MiMiC2) to identify alternative isolates from a genome collection that encode the same critical function [3]. | Creates a more robust SynCom where essential functions are maintained even if one strain is lost, mitigating reduced interactions. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Protocol for a Function-Based Synthetic Community Design

This methodology ensures the selected strains capture the functional profile of a target ecosystem, promoting meaningful interactions [3].

- Metagenomic Analysis: Obtain metagenomic assemblies from the target ecosystem (e.g., healthy vs. diseased gut).

- Genome Collection: Curate a collection of isolate genomes or high-quality Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs).

- Functional Annotation: Annotate the proteome of both metagenomes and isolate genomes using hmmscan against a database like Pfam.

- Function Weighting: Assign weights to functions:

- Add a weight for "core" functions (prevalent in >50% of target metagenomes).

- Add a weight for functions differentially enriched in the target group (e.g., diseased) versus a control group (e.g., healthy) using a Fischer's exact test.

- Iterative Strain Selection: Use a script (e.g., MiMiC2.py) to iteratively select the highest-scoring isolate from the genome collection. The score is based on the number of matching Pfams with the target metagenome, plus the weighted scores.

- In Silico Validation: Simulate the growth of the selected SynCom members using metabolic modeling in a tool like BacArena to check for cooperative coexistence prior to experimental validation [3].

Protocol 2: Workflow for Diagnosing Unstable Community Dynamics

Diagram: Troubleshooting Unstable SynCom Dynamics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| GapSeq | A software tool for the automated construction of genome-scale metabolic models. It generates models from genome annotations that are compatible with simulation tools like BacArena, enabling in silico prediction of microbial interactions [3]. |

| BacArena | An R toolkit that allows for the simulation of microbial communities in a spatially structured environment. It is used to simulate the growth and metabolic interactions of SynCom members in silico before experimental assembly [3]. |

| MiMiC2 Pipeline | A bioinformatics pipeline for the function-based selection of synthetic communities. It selects isolates from a genome collection that best match the functional profile (Pfam domains) of a target metagenome, ensuring functional representation [3]. |

| Gnotobiotic Mouse Models | Germ-free or defined-flora animal models. They are essential for in vivo validation of SynComs, allowing researchers to study community stability and host-microbe interactions in a controlled environment [3]. |

| Hot-Start Polymerase | A modified PCR enzyme inactive at room temperature. It prevents the formation of non-specific products and primer-dimers during reaction setup, which is crucial for amplifying specific microbial genes from a complex community sample without bias [5]. |

The Impact of Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs) on Community Dynamics

FAQs: Understanding Higher-Order Interactions

What are Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs) in ecological communities? Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs) occur when the interaction between two species is modified by the presence or abundance of a third species. Unlike pairwise interactions, HOIs can alter the strength and direction of competition or facilitation in multi-species communities, making community dynamics more complex and less predictable from simple two-species experiments [6].

Why are HOIs a critical consideration in multi-species synthetic communities (SynComs) research? HOIs are critical because their existence and strength are sensitive to environmental context [6]. In SynComs research, ignoring HOIs can lead to inaccurate predictions of species coexistence and community stability. The presence of a strong HOI can enable the persistence of a species that would otherwise be competitively excluded, a outcome that cannot be predicted from pairwise data alone [6].

What are common experimental symptoms that suggest HOIs are affecting my SynCom? A key symptom is when the dynamics observed in a multi-species community significantly deviate from the predictions of a model parameterized using only data from one- and two-species treatments [6]. For instance, if a species thrives in a complex community but is consistently outcompeted in all its pairwise tests, a facilitative HOI is likely at play.

How can I determine if inconsistent functional performance across trials is due to HOIs? Inconsistent functional performance, such as variable disease suppression or plant growth promotion, can stem from context-dependent HOIs [7]. To diagnose this, compare the functional output of the full SynCom to the outputs of various simplified sub-communities. If the full community's performance is not the simple average of its parts, HOIs are likely modifying functional expression [7].

My SynCom shows low stability and one species consistently goes extinct. Could HOIs be the cause? Yes, this is a classic scenario where HOIs might be involved. The extinctions could be due to undetected competitive HOIs that intensify competition beyond what pairwise data suggests. Conversely, the problem might be that your community design lacks stabilizing HOIs, which in natural environments can create niche differences that promote coexistence [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unpredictable Community Dynamics

Symptoms: The observed multi-species community dynamics (e.g., species coexistence, biomass production) do not match model predictions based on pairwise interaction data [6].

Solution: Implement a model-fitting and validation workflow.

| Step | Action | Protocol Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Data Collection | Grow all species in all possible one- and two-species combinations under controlled conditions. Monitor population dynamics over time [6]. | A dataset for parameterizing a baseline competition model without HOIs. |

| 2 | Model Parameterization | Use the one- and two-species data to parameterize a mathematical model (e.g., a generalized Lotka-Volterra model) for your community [6]. | A predictive model that assumes no HOIs. |

| 3 | Model Validation & HOI Detection | Compare the predictions of your parameterized model against the actual observed dynamics of the full multi-species community [6]. | A significant deviation between prediction and observation indicates the presence of strong HOIs. |

Problem: Context-Dependent SynCom Performance

Symptoms: A SynCom that functions consistently in one laboratory environment (e.g., low resource enrichment) fails or behaves unpredictably in another (e.g., high resource enrichment) [6].

Solution: Systematically test the SynCom across key environmental gradients.

| Step | Action | Protocol Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify Gradient | Identify the environmental factor suspected of causing instability (e.g., resource enrichment, pH, temperature) [6]. | A targeted experimental factor for testing. |

| 2 | Replicate Experiment | Conduct the SynCom assembly experiment (as in the troubleshooting guide above) at multiple levels of the chosen environmental factor [6]. | Multiple datasets showing how interactions change with context. |

| 3 | Re-Parameterize Models | Parameterize separate models for each environmental context using the relevant one- and two-species data [6]. | Context-specific models that can reveal how HOIs change with the environment. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol for Detecting HOIs

Objective: To rigorously test for the existence and strength of HOIs among competing species and infer their long-term consequences for species coexistence [6].

Methodology:

Experimental Design:

- Select the candidate species for your SynCom (e.g., three bacterivorous ciliate species) [6].

- Establish microcosms for all possible species combinations: all monocultures, all pairwise cultures, and the full multi-species community. Each treatment should have sufficient replication.

- Implement this full design across the different environmental contexts you wish to test (e.g., low and high resource enrichment) [6].

Data Collection:

- Regularly census the population density of each species in each microcosm over a time series that is long enough to observe dynamic trends and potential equilibria [6].

Model Fitting and Analysis:

- Use the population dynamic data from the one- and two-species treatments to parameterize a competition model for your community. The model should account for nonlinear intraspecific density dependence where appropriate [6].

- Use the parameterized model to generate a prediction for the dynamics of the full multi-species community, assuming no HOIs.

- Statistically compare the model's prediction to the empirically observed dynamics of the full community. A significant deviation indicates the presence of a statistically supported HOI [6].

Interpretation:

- The direction and magnitude of the deviation reveal the nature of the HOI. For example, if a species persists in the full community but was predicted to go extinct, the HOI is facilitative and promotes coexistence [6].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram: HOI Detection Workflow.

Signaling Pathways & Conceptual Diagrams

HOI Impact on Coexistence

Diagram: HOI Alters Coexistence Outcome.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and tools for studying HOIs in synthetic communities.

| Item | Function in HOI Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Systems (e.g., sterile plant growth systems, rodent isolators) | Provides a controlled, sterile environment to assemble SynComs from the bottom-up with a known species composition [7]. | Essential for assessing the causal effects of a defined SynCom and its HOIs on a host phenotype, without interference from an unknown background microbiota [7]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) | Computational models that predict the metabolic capabilities of and interactions between microbial species based on their annotated genomes [7]. | Used in silico to predict potential resource competition or cross-feeding (metabolic HOIs) that could influence community stability and function [7]. |

| High-Throughput Phenotyping | Automated systems to screen microbial strains or simple communities for functional traits (e.g., substrate utilization, antibiotic production) [7]. | Informs the selection of SynCom members by identifying strains with specific functional traits (e.g., chitin degradation) that may lead to HOIs when combined with other members [7]. |

| Differential Abundance Analysis Tools | Bioinformatics software to identify microbial taxa that are significantly more or less abundant between different sample groups (e.g., suppressive vs. conducive soils) [7]. | A top-down approach to identify candidate strains for SynCom construction that are naturally associated with a desired phenotype and may participate in relevant HOIs [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do interaction outcomes observed in paired cultures often fail to predict behavior in more complex communities? In a multi-species setting, the presence of additional species can fundamentally alter the interactions between any two original members, a phenomenon known as a Higher-Order Interaction (HOI) [8]. For instance, an antagonistic relationship observed between two species in isolation may be suppressed by the introduction of a third, resistant species that modifies the community's chemical environment or physical structure [8]. The dynamics in complex communities are an emergent property that cannot always be extrapolated from the sum of their pairwise interactions [8] [9].

FAQ 2: How can I stabilize a synthetic community that shows a decline in one or more member species over time? Promoting cooperation and reducing negative competition is key to stability. Strategies include:

- Engineering Metabolic Complementarity: Partition metabolic pathways across different community members to create syntrophic dependencies, where each strain relies on others for essential metabolites [10] [11].

- Selecting Narrow-Spectrum Resource Utilizers: Incorporate strains that specialize in using a limited set of resources. This reduces metabolic resource overlap (MRO) and increases the potential for cooperative metabolic interactions (MIP), which enhances community stability [11].

- Introducing Spatial Structure: Use microfluidic devices, microwell arrays, or biofilm engineering to create a structured environment. Spatial segregation strengthens local positive interactions and protects cooperative members from being outcompeted by "cheaters" [10].

FAQ 3: What environmental factors most strongly influence interspecies interactions? The abiotic environment profoundly shapes interactions. Two of the most critical factors are:

- Nutrient Availability: High nutrient levels often intensify competitive interactions, potentially leading to a loss of biodiversity. In contrast, low-nutrient or otherwise stressful environments can promote cooperative interactions, such as cross-feeding, for mutual survival [9].

- Environmental pH: Bacteria frequently modify their local pH, which can in turn determine community composition and stability. A species' ability to tolerate or create a specific pH range can be a major competitive or cooperative advantage [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Reduced or Unstable Interactions in a Multi-Species Synthetic Community

Step 1: Diagnose the Nature of the Interaction Failure

First, systematically characterize the failure mode to guide your solution.

| Observation | Possible Underlying Cause | Diagnostic Experiments to Run |

|---|---|---|

| One species dies rapidly | Antagonism (e.g., antibiotic production) from another member [8] | Spot-on-lawn assays; co-culture with conditioned media to test for diffusible toxins. |

| Gradual decline of all/multiple species | Lack of cooperation; competitive exclusion; insufficient cross-feeding [11] [9] | Measure metabolic exchange metabolites (e.g., amino acids, vitamins); genome-scale metabolic modeling to assess MRO and MIP [11]. |

| Interaction is strong in pairs but lost in the full community | Higher-Order Interactions (HOIs); presence of a third species modulates the original interaction [8] | Reconstruct all possible sub-communities (pairs, triples) to identify the specific combination that disrupts the interaction. |

| Unpredictable population dynamics | Lack of spatial structure leading to "tragedy of the commons" [10] | Transition from well-mixed liquid culture to a spatially structured environment (e.g., agar plates, biofilms, microfluidic devices). |

Step 2: Implement Corrective Protocols Based on Diagnosis

Protocol A: For Diagnosed Antagonism

- Objective: To preserve a species that is sensitive to antagonism within a larger community.

- Method: Introduce a Resistant (R) species that can mitigate the antagonistic effect.

- Cultivate the Antagonistic (A) and Sensitive (S) species together in a co-culture and confirm the deleterious effect [8].

- Introduce the candidate R species. The R species should not harm A or S but must be able to interfere with the antagonistic mechanism (e.g., by degrading the toxin or altering environmental pH) [8].

- Monitor the population dynamics of all three species (A, S, R) in real-time if possible. A successful intervention will show restored growth of the S species in the triple co-culture compared to the A-S pair [8].

- Reagent Solution: The BARS community model (comprising Bacillus pumilus [A], Sutcliffiella horikoshii [S], and Bacillus cereus [R]) is a well-defined experimental system for studying this dynamic [8].

Protocol B: For Diagnosed Lack of Cooperation/Instability

- Objective: To construct a stable, cooperative community from the ground up.

- Method: Rational bottom-up design using metabolic modeling and phenotypic screening.

- Select Functionally Diverse Strains: Choose strains with desired, complementary plant-beneficial functions (e.g., nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization) [11].

- Profile Resource Utilization: Use phenotype microarrays (e.g., Biolog plates) to quantify the "resource utilization width" for each candidate strain on relevant carbon sources [11].

- Prioritize Narrow-Spectrum Strains: Favor strains with a lower resource utilization width, as they exhibit lower Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) and higher Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP), which correlates with stability [11].

- Validate In Silico and In Vivo: Construct Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GMMs) to simulate the MIP and MRO for all possible community combinations. Assemble the top-predicted stable communities experimentally and monitor population dynamics over time in the target habitat (e.g., plant rhizosphere) [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Investigating Spatiotemporal Interactions.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| BARS Model System [8] | A defined three-species community (Bacillus pumilus, Sutcliffiella horikoshii, Bacillus cereus) to study Higher-Order Interactions and immediate response to antagonism. |

| Phenotype Microarrays (e.g., Biolog Plates) [11] | High-throughput screening of carbon source utilization to determine a strain's "resource utilization width," a key predictor of community stability. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GMMs) [11] | In silico tools to compute Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) and Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) for rational community design. |

| Microfluidic/Microwell Devices [10] | Tools to impose spatial structure on microbial communities, allowing for the study of how physical segregation affects interaction dynamics. |

| COMETS (Computation of Microbial Ecosystems in Time and Space) [10] | A dynamic flux balance analysis software that simulates microbial growth and metabolic interactions in a 2D spatial environment. |

Diagrams and Workflows

Diagram 1: Higher-Order Interaction in a Three-Species Community

Diagram 2: Community Design Workflow for Enhanced Stability

Diagram 3: Relationship Between Resource Use and Stability

Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: My synthetic community collapses, with one or two species dominating the culture. How can I reduce competition? This indicates excessive metabolic resource overlap (MRO) and insufficient positive interactions. To address this:

- Diagnose Competition: Calculate the MRO for your community members using genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). A high MRO suggests strong competition for nutrients [11].

- Solution - Incorporate Specialists: Introduce narrow-spectrum resource-utilizing (NSR) strains. Research shows that strains with a lower resource utilization width contribute to lower MRO and increase community stability. For example, in one study, Cellulosimicrobium cellulans (resource width: 13.10) significantly reduced MRO compared to broad-spectrum utilizers like Bacillus megaterium (resource width: 36.76) [11].

- Design Principle: Aim for a mix of metabolic capabilities to minimize niche overlap. Use phenotype microarrays to profile the carbon source utilization of your candidate strains and select those with complementary, non-overlapping profiles [11].

FAQ 2: The community is stable but does not perform the desired function. How can I improve functional robustness? This occurs when community assembly is based solely on taxonomy or coexistence, without ensuring the encoded functions are present.

- Diagnose Function: Use a function-based design approach. Annotate the genomes of your candidate isolates for key functional genes (e.g., Pfam domains) and compare this to a list of functions identified as critical from metagenomic data of a high-performing natural community [3].

- Solution - Weight Key Functions: Assign higher selection weights to microbial strains that encode core and differentially enriched functions. For instance, when modeling a disease state, functions that are significantly more prevalent in diseased versus healthy metagenomes should be heavily weighted during the in silico selection of SynCom members [3].

- Experimental Validation: The designed community must be validated in vivo. A function-directed SynCom of 10 members designed to model inflammatory bowel disease successfully induced colitis in gnotobiotic mice, confirming it captured the disease-associated functional profile [3].

FAQ 3: How can I predict if my designed community will be stable before I culture it? Utilize in silico modeling to simulate community dynamics and interactions prior to experimental validation.

- Method - Metabolic Modeling: Employ tools like BacArena to conduct metabolic modeling with GEMs. This provides simulated evidence for cooperative potential and coexistence [3].

- Key Metrics: Calculate two critical indices from the models:

- Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP): Reflects the potential for cooperative, cross-feeding interactions. A higher MIP is better.

- Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO): Indicates the level of competition for resources. A lower MRO is better [11].

- Protocol: The simulation typically involves creating an "arena," loading the metabolic models of your strains, and simulating growth over a set period (e.g., 7 hours) to observe outcomes [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Metabolic Competition

Problem: Rapid loss of diversity due to competitive exclusion.

Investigation & Resolution Steps:

Profile Resource Utilization:

- Protocol: Use phenotype microarray plates (e.g., Biolog PM plates) to test the ability of each individual strain to utilize a wide array of single carbon sources. This quantitatively defines each strain's metabolic niche [11].

- Output: A resource utilization profile for each strain.

Calculate Resource Utilization Width and Overlap:

- Protocol: From the phenotype data, calculate the "resource utilization width" (the total number of carbon sources a strain can use) and the "pairwise overlap index" (the number of substrates shared between two strains). These are direct indicators of a strain's potential to be a broad-generalist competitor [11].

- Output: Numerical values for width and pairwise overlap.

Build and Simulate with GEMs:

Mitigation Strategy:

- If MRO is high, replace broad-spectrum resource-utilizing (BSR) strains with narrow-spectrum (NSR) strains. Data shows a clear positive correlation between resource utilization width and MRO [11].

Quantitative Data on Resource Utilization and Stability [11]:

| Bacterial Strain | Resource Utilization Width | Average Overlap Index | Role in Community Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus megaterium L | 36.76 | 0.74 | Broad-spectrum utilizer (BSR), high competition |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens J | 37.32 | 0.72 | Broad-spectrum utilizer (BSR), high competition |

| Bacillus velezensis SQR9 | 35.50 | 0.83 | Broad-spectrum utilizer (BSR), high competition |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri G | 25.59 | Information Missing | Narrow-spectrum utilizer (NSR), central to cooperation |

| Azospirillum brasilense K | 24.37 | Information Missing | Narrow-spectrum utilizer (NSR) |

| Cellulosimicrobium cellulans E | 13.10 | 0.51 | Narrow-spectrum utilizer (NSR), key for stability |

Guide 2: Designing for Functional Robustness

Problem: The community fails to execute the expected biochemical function.

Investigation & Resolution Steps:

Define a Functional Target from Metagenomes:

- Protocol: Assemble and annotate metagenomic sequences from environmental samples (e.g., healthy vs. diseased states) using Prodigal for gene prediction and HMMscan against databases like Pfam for functional annotation. Create a binarized presence-absence vector of functions for your sample group [3].

Select Strains from a Genome Collection Based on Function:

- Protocol: Apply the same annotation pipeline to a collection of isolated genomes. Use a computational tool like MiMiC2 to select the subset of strains whose combined functional (Pfam) profile best matches the target metagenomic profile. Prioritize strains that encode "core" functions (present in >50% of samples) and "differentially enriched" functions (significantly associated with a phenotype of interest) [3].

- Output: A shortlist of strains selected for their functional capacity, not just taxonomy.

Validate Cooperativity In Silico:

- Protocol: As in Guide 1, use GEMs to simulate the paired growth of selected strains. The

Paired_Growth.Rscript in BacArena, for example, places two models in a shared environment to simulate their interaction and check for mutual growth support [3].

- Protocol: As in Guide 1, use GEMs to simulate the paired growth of selected strains. The

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Function-Based SynCom Selection

This protocol details the MiMiC2 pipeline for selecting community members based on metagenomic functional profiles [3].

Metagenomic Analysis:

- Obtain metagenomic samples (raw reads or assemblies).

- If using raw reads, filter out host sequences using a tool like BBMAP.

- Perform assembly using MEGAHIT.

- Predict the proteome using Prodigal with the

-p metaoption. - Annotate protein sequences using

hmmscanagainst the Pfam database.

Genome Collection Processing:

- Obtain isolate genomes or high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs).

- Process each genome through the same proteome prediction and Pfam annotation pipeline as the metagenomes.

Strain Selection with MiMiC2:

- Vectorize the Pfam annotations into binarized vectors for both metagenomes and genomes.

- Assign weights to functions:

- Core functions (>50% prevalence in target metagenomes): Add a weight (default 0.0005).

- Differentially enriched functions (e.g., between healthy/diseased): Add a weight (default 0.0012) based on a Fisher's exact test.

- Run the main

MiMiC2.pyscript. It iteratively selects the genome that best matches the metagenomic functional profile, incorporating the weighting scheme, until the desired number of members is reached.

Protocol 2: Assessing Metabolic Interactions with GEMs

This protocol uses GapSeq and BacArena to model community metabolic interactions [3] [11].

Model Reconstruction:

- For each bacterial strain, generate a genome-scale metabolic model using GapSeq (e.g., with the

doallcommand). This creates a model compatible with BacArena. - Refine the model by constraining it with experimental data, such as carbon source utilization from phenotype microarrays [11].

- For each bacterial strain, generate a genome-scale metabolic model using GapSeq (e.g., with the

Simulation Setup:

- Use an R script to create a simulation

Arena(e.g., size 100x100). - Load the metabolic models and add them to the arena using

addOrg. For pairwise testing, add 10 cells of each strain randomly. - Set a default medium using

addDefaultMedto ensure a standardized environment.

- Use an R script to create a simulation

Run Simulation and Analyze:

- Simulate growth over a defined period (e.g., 7 hours) using

simEnv. - Extract growth data and metabolite exchanges.

- Calculate Key Metrics: Compute the Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) and Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) from the simulation results to quantify cooperation and competition [11].

- Simulate growth over a defined period (e.g., 7 hours) using

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Function-Based SynCom Design

Metabolic Interaction Network

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for SynCom Stability Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotype Microarrays (e.g., Biolog PM) | High-throughput profiling of carbon source utilization to determine metabolic niche width and overlap. | Uses 58+ common rhizosphere/resources to calculate Resource Utilization Width [11]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | In silico simulation of metabolism to predict growth, resource use, and metabolite exchange. | Built with tools like GapSeq; simulated in BacArena to calculate MIP and MRO [3] [11]. |

| Pfam Database | A curated database of protein families and hidden Markov models (HMMs) for functional annotation. | Used with HMMscan to annotate metagenomes and isolate genomes for function-based selection [3]. |

| MiMiC2 Software | A computational pipeline for the function-based selection of synthetic community members from isolate collections. | Selects strains based on matching Pfam profiles to a target metagenome, with weighting for key functions [3]. |

| Gnotobiotic Mouse Models | Animal models with a completely defined microbiota for validating the function and host impact of designed SynComs. | Used to confirm a 10-member IBD SynCom could induce disease, validating its functional accuracy [3]. |

Emergent Properties in Multi-Species Consortia

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our synthetic consortium performs well in laboratory media but fails to show the expected emergent properties, such as enhanced product output, in a more complex environmental sample. What could be the issue?

Laboratory media often provide ideal, homogeneous conditions that do not replicate the nutritional and abiotic stresses found in natural environments. The emergent functions of your consortium likely depend on specific cross-feeding interactions that are disrupted in the more complex setting. To troubleshoot:

- Diagnosis: The loss of function is likely due to insufficient activation or stability of key interactions, such as metabolite exchange, in a competitive environment [12].

- Solution: Re-design your consortium to include "helper" or "scaffold" strains that facilitate the main interaction. For example, in a consortium designed for biodegradation, you could include a strain that consumes an inhibitory byproduct, thereby protecting the primary degraders [13]. Pre-adapting your consortium to the target environment through experimental evolution can also select for more robust variants [14].

Q2: One species consistently outcompetes and eliminates another in our synthetic community, leading to a loss of the consortium. How can we improve long-term coexistence?

Unbalanced growth and collapse are common challenges often caused by competitive exclusion or the evolution of parasitic behaviors that disrupt mutualistic exchanges [14].

- Diagnosis: The system likely lacks a mechanism to stabilize the interaction, such as spatial structure or a feedback loop that benefits both parties.

- Solution:

- Spatial Structuring: Cultivate the consortium as a biofilm. The physical structure creates microenvironments and gradients that allow different species to occupy distinct niches, preventing one from overwhelming the other [13].

- Engineering Interdependence: Design the consortium so that each member provides an essential resource for the other. For instance, engineer a cross-feeding interaction where one species relies on a metabolite produced by the second, and vice-versa [13].

Q3: The emergent property of our consortium (e.g., biofuel yield) is strong initially but diminishes over successive cultivation cycles. Why is this happening, and how can we maintain stability?

This indicates a lack of evolutionary stability, where mutations in one or more members alter their functional traits or interaction dynamics over time [14].

- Diagnosis: The selective pressure to maintain the cooperative interaction may be weaker than the pressure for individual species to "cheat" and optimize their own growth.

- Solution:

- Apply Periodic Selection Pressure: Regularly passage your consortium under conditions where the desired emergent property (e.g., high product yield) is essential for growth. This enriches for community variants that maintain the cooperative function.

- Use Fluctuating Environments: If applicable, cultivate the consortium in an environment that alternates between different conditions (e.g., different carbon sources). This can prevent any single species from dominating and can help maintain functional diversity [14].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

The following table outlines specific experimental issues, their potential causes, and recommended actions.

| Problem | Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of Consortium Function | Expected emergent property (e.g., degradation rate, product titer) is not observed or is significantly lower than the sum of monocultures. | Disrupted cross-feeding; inhibitory conditions; lack of key nutrient; evolution of "cheater" strains [14]. | Verify member compatibility and growth requirements; monitor metabolite exchange; re-introduce spatial structure (biofilms); apply selective pressure [13]. |

| Unstable Species Ratio | One consortium member consistently declines in abundance or goes extinct over time. | Unbalanced growth rates; competitive exclusion; parasitic behavior; lack of interdependence [14]. | Engineer obligatory cross-feeding; use temporal environmental fluctuations; implement a kill-switch for overgrown species; utilize biofilm cultivation [14]. |

| Poor Field Performance | Consortium functions in controlled lab settings but fails to establish or function in natural/application environments. | Competition with native microbiota; insufficient colonization; inadequate environmental conditions for persistence [12]. | Pre-adapt consortium to the target environment; include native, well-adapted "scaffold" species; use encapsulation to enhance initial survival [12]. |

| Low Product Yield | The final titer of a target molecule (e.g., ethanol, enzyme) is low despite seemingly healthy consortium growth. | Inefficient metabolic flux; product inhibition; suboptimal resource allocation; nutrient limitations [13]. | Engineer a positive feedback loop (e.g., product removal drives higher production); optimize culture medium; use necromass recycling to increase resource flux [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Findings

Protocol 1: Establishing a Cross-Feeding Consortium for Enhanced Biodegradation

This protocol is adapted from research on an Acinetobacter johnsonii and Pseudomonas putida consortium, which exhibits a commensal interaction where A. johnsonii breaks down benzyl alcohol into benzoate, which is then consumed by P. putida [14].

Objective: To assemble and quantify the emergent property of enhanced substrate degradation in a two-species cross-feeding consortium.

Materials:

- Strains: Acinetobacter johnsonii, Pseudomonas putida.

- Growth Media: Minimal salts medium supplemented with benzyl alcohol as the sole carbon source.

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer, HPLC system, shaking incubator.

Methodology:

- Pre-culture: Grow each bacterial strain independently in minimal medium with benzyl alcohol to mid-exponential phase.

- Consortium Inoculation: Mix the two pre-cultures in a 1:1 cell ratio and inoculate into fresh medium containing benzyl alcohol.

- Monoculture Controls: Inoculate each strain separately into the same medium.

- Incubation: Incubate all cultures under appropriate conditions (e.g., 30°C with shaking).

- Monitoring:

- Measure optical density (OD600) every 4-6 hours to track growth.

- Collect supernatant samples to quantify benzyl alcohol depletion and benzoate accumulation using HPLC.

- Plate samples on selective media to track the abundance of each species over time.

Expected Outcome: The consortium will demonstrate an emergent property of more rapid and complete benzyl alcohol degradation compared to the A. johnsonii monoculture, as the cross-feeding interaction removes the inhibitory benzoate byproduct, driving the reaction forward [14].

Workflow: Cross-Feeding Consortium Assembly

Protocol 2: Quantifying Emergent Properties in a Biofilm Consortium

This protocol is based on work with a Clostridium phytofermentans and Escherichia coli consortium, which demonstrated significantly enhanced ethanol production and biomass accumulation in biofilms, especially under oxygen perturbations [13].

Objective: To cultivate a synthetic consortium as a biofilm and measure emergent properties like enhanced product synthesis and stress resilience.

Materials:

- Strains: Clostridium phytofermentans (obligate anaerobe), Escherichia coli (facultative anaerobe).

- Growth Media: Cellobiose-rich anoxic medium (e.g., mGS-2).

- Equipment: Anaerobic chamber, biofilm reactors (e.g., flow cells or multi-well plates with pegs), confocal laser scanning microscope (optional), gas chromatograph.

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow C. phytofermentans and E. coli to mid-exponential phase under anaerobic conditions.

- Biofilm Establishment: Mix cultures and inoculate into biofilm reactors. For controls, inoculate monocultures.

- Perturbation: Introduce controlled oxic pulses to the consortium biofilm. E. coli will consume O₂, creating anoxic niches for C. phytofermentans [13].

- Analysis:

- Biomass: Quantify biofilm biomass at the end of the experiment using crystal violet staining or by detaching and plating cells.

- Productivity: Measure ethanol titers in the supernatant using gas chromatography.

- Spatial Structure: If possible, use fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or confocal microscopy to visualize the spatial organization of the two species within the biofilm.

Expected Outcome: The consortium biofilm will show a >250% increase in biomass and a >800% increase in ethanol production compared to the sum of monoculture biofilms, demonstrating a clear emergent property driven by division of labor and niche partitioning [13].

Mechanism: Biofilm Stress Resilience

Table 1: Measured Emergent Properties in Model Consortia

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from seminal studies on synthetic microbial consortia, highlighting the performance gains attributable to emergent properties.

| Consortium Members | Interaction Type | Key Emergent Property | Quantitative Enhancement (vs. Monocultures) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clostridium phytofermentans & Escherichia coli | Cross-feeding, Necromass recycling | Ethanol Production | >800% increase in titer [13] | [13] |

| Clostridium phytofermentans & Escherichia coli | Cross-feeding, Necromass recycling | Cellobiose Catabolism | >200% increase in consumption [13] | [13] |

| Clostridium phytofermentans & Escherichia coli | Cross-feeding, Necromass recycling | Biomass Productivity | >120% increase in cell dry weight [13] | [13] |

| Clostridium phytofermentans & Escherichia coli (Biofilm) | Division of labor, O₂ consumption | Biomass Accumulation | ~250% increase under anoxic/oxic cycling [13] | [13] |

| Acinetobacter johnsonii & Pseudomonas putida | Commensalism (Cross-feeding) | Community Stability | Stable coexistence in constant environment; extinction in fluctuating environments [14] | [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for SynCom Research

A selection of key reagents, strains, and tools used in the design, construction, and analysis of synthetic microbial consortia.

| Item | Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Model Strains (Acinetobacter johnsonii, Pseudomonas putida) | Biological Model | Used to study the stability of commensal cross-feeding interactions and their response to environmental fluctuations [14]. |

| Specialist Strains (Clostridium phytofermentans, E. coli) | Biological Model | A consortium combining a primary resource specialist (cellulose degrader) with a versatile secondary-resource specialist to achieve enhanced bioconversion [13]. |

| Minimal Media with Specific Carbon Sources (e.g., Benzyl Alcohol, Cellobiose) | Growth Medium | Used to control and define the ecological interactions between consortium members, forcing cross-feeding and interdependence [14] [13]. |

| Biofilm Reactors (e.g., Flow Cells, Peg Lids) | Cultivation Equipment | Provides spatial structure, which is critical for stabilizing interactions, enabling division of labor, and enhancing stress resilience in consortia [13]. |

| d3-scale-chromatic & Viridis Palettes | Data Visualization | Color palettes for D3.js used to create accessible and clear visualizations of complex consortium data, such as species abundance over time [15]. |

| Nylon Membrane Microbial Cages | Field Experiment Tool | Allows consortia to be deployed in natural environments while preventing migration, enabling the study of evolutionary dynamics in the field [14]. |

Engineering Stable Consortia: Design Strategies and Assembly Methods

Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down Approaches for Community Construction

In multi-species synthetic communities (SynComs) research, two principal engineering philosophies are employed: the top-down and bottom-up approaches. The top-down approach involves applying selective pressure to steer a natural microbial consortium toward a desired function, while the bottom-up approach involves rationally designing a new community by assembling individual microorganisms based on prior knowledge of their metabolic pathways and potential interactions [16].

Both strategies aim to mitigate the common challenge of reduced interactions in synthetic ecosystems, which can lead to functional instability, loss of key metabolic functions, and eventual community collapse. Understanding the principles, applications, and troubleshooting aspects of each method is crucial for researchers developing robust, functionally stable SynComs for drug development, biotechnology, and other scientific applications.

Top-Down Approach: Principles and Protocols

Core Concept and Workflow

The top-down approach is a classical method that uses environmental variables to selectively steer an existing microbial consortium to achieve a target function. This method manipulates an entire natural community through selective pressure, such as specific substrate availability, temperature, pH, or other operational conditions, to enrich for community members that perform a desired function [16].

The diagram below illustrates a generalized top-down approach workflow:

Key Experimental Protocol: Selective Enrichment

Objective: To steer a natural microbial community toward a specific function through controlled environmental conditions.

Materials:

- Source Inoculum: Environmental sample containing diverse microorganisms

- Growth Medium: Minimal medium with target substrate as primary carbon/nitrogen source

- Bioreactor System: Controlled environment for maintaining selective conditions

- Monitoring Equipment: HPLC, GC-MS, spectrophotometer for process monitoring

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Collect environmental sample relevant to target function

- Selective Condition Setup: Establish culture conditions favoring desired metabolic activity

- Batch Transfers: Perform sequential transfers to fresh medium to enrich adapted community

- Process Monitoring: Regularly analyze community composition and functional output

- Stabilization: Maintain selective pressure until stable function is established

Troubleshooting Note: If the community fails to converge on the desired function, consider adjusting the selective pressure gradient or introducing additional environmental constraints to further steer community assembly.

Bottom-Up Approach: Principles and Protocols

Core Concept and Workflow

The bottom-up approach uses prior knowledge of metabolic pathways and possible interactions among consortium partners to design and engineer synthetic microbial consortia from individual isolates. This strategy offers greater control over the composition and function of the consortium for targeted bioprocesses [16] [7].

The diagram below illustrates a generalized bottom-up approach workflow:

Key Experimental Protocol: Rational Community Assembly

Objective: To construct a stable, functional synthetic community from characterized individual isolates.

Materials:

- Pure Cultures: Fully sequenced and metabolically characterized isolates

- Interaction Assay Platforms: Microplates, microfluidic devices for testing pairwise interactions

- Genetic Engineering Tools: CRISPR, plasmids for introducing specific interactions

- Analytical Tools: Sequencing platforms, metabolomics for functional validation

Procedure:

- Strain Selection: Choose isolates based on functional traits and potential interactions

- Interaction Screening: Test pairwise and higher-order interactions

- Community Design: Design consortium based on functional and ecological principles

- Ratio Optimization: Determine optimal starting ratios for community assembly

- Stability Testing: Monitor community composition and function over multiple generations

Troubleshooting Note: If the synthetic community shows instability, consider introducing spatial structure or engineering cross-feeding dependencies to stabilize interactions.

Comparative Analysis: Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches for Synthetic Community Construction

| Parameter | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity Management | Reduces complexity through selective pressure | Builds complexity from simple, defined parts |

| Design Control | Limited control over final composition | High control over composition and ratios |

| Implementation Time | Can be lengthy due to enrichment needs | Faster assembly with pre-characterized parts |

| Stability Challenges | Naturally stable but functionally variable | Engineered stability but prone to collapse |

| Required Expertise | Microbial ecology, environmental microbiology | Synthetic biology, systems biology |

| Typical Applications | Waste valorization, bioremediation, anaerobic digestion | Pharmaceutical production, biosensing, metabolic engineering |

| Success Rate | High for complex substrates, lower for specific products | Higher for defined functions, lower for complex environments |

| Key Advantage | Leverages natural microbial interactions | Enables precise control and predictability |

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes from Representative Studies Using Each Approach

| Study Focus | Approach | Community Size | Key Outcome | Stability Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Digestion [16] | Top-Down | High diversity | 0.14-0.39 L biogas/g VS | Long-term (industrial scale) |

| Waste Valorization [16] | Top-Down | Unknown | Valuable products from waste | Process-dependent |

| Model Gut Community [7] | Bottom-Up | 100+ strains (hCom1/hCom2) | Stable colonization in mice | Several weeks |

| Plant Growth Promotion [7] | Bottom-Up | 7 strains | Suppression of Fusarium wilt | Field trial duration |

| Cross-Feeding Mutualism [17] | Bottom-Up | 2 strains | Sustained cooperative growth | Laboratory scale stability |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Mitigating Reduced Interactions

Q1: Why does our synthetic community show reduced interactions and functional instability over time?

A: Reduced interactions often result from:

- Unbalanced growth rates leading to dominance by faster-growing species

- Insufficient cross-feeding dependencies to maintain stable coexistence

- Accumulation of toxic metabolites inhibiting partner growth

- Evolution of "cheater" strains that benefit from but don't contribute to community function [17]

Solution: Implement the following corrective measures:

- Engineer obligate cross-feeding dependencies through auxotrophies

- Introduce spatial structure to create ecological niches

- Adjust initial inoculation ratios to balance growth dynamics

- Include regulatory circuits that punish "cheater" behavior

Q2: How can we predict and prevent the emergence of "cheater" strains in our synthetic community?

A: Cheaters frequently evolve in synthetic communities when:

- Some members can benefit from public goods without contributing

- There are no mechanisms enforcing cooperation

- Evolutionary pressures favor metabolic streamlining

Prevention Strategies:

- Create spatial structure that gives cooperators preferential access to goods they produce [17]

- Implement negative frequency-dependent selection

- Engineer syntrophic relationships where each member depends on others for essential metabolites

- Use kill switches activated by cheating behavior

Q3: What methods can enhance long-term stability in bottom-up designed communities?

A: Several methods can significantly improve stability:

- Spatial Structuring: Use biofilms, microcapsules, or compartmentalization to create niches

- Cross-Feeding Engineering: Design obligate metabolic dependencies between members

- Ratio Optimization: Systematically test different starting ratios to find stable configurations

- Environmental Control: Maintain constant conditions that favor the designed interactions

- Evolutionary Training: Allow community to adapt under controlled conditions before application

Q4: How can we effectively monitor interaction strength in complex synthetic communities?

A: Implement multi-modal monitoring:

- Metabolomic Profiling: Track metabolite exchange and consumption

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Monitor spatial organization and growth dynamics

- Single-Cell Genomics: Assess individual cell activities within the community

- Reporter Systems: Use fluorescent tags to visualize specific interactions

- Multi-Omics Integration: Combine genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics data

Research Reagent Solutions for Community Construction

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Applications in Community Construction

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Gnotobiotic Growth Chambers | Provides controlled environment for community assembly | Both approaches, essential for reducing external variables |

| Microfluidic Devices | Enables high-throughput interaction screening | Bottom-up approach for testing pairwise interactions |

| Stable Isotope Probing (SIP) Materials | Tracks nutrient flows in communities | Both approaches for understanding interaction networks |

| Fluorescent Reporter Plasmids | Visualizes population dynamics and spatial organization | Bottom-up approach for real-time monitoring |

| Selective Media Components | Applies selective pressure in top-down approaches | Top-down approach for community steering |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) | Predicts metabolic interactions and complementarity | Bottom-up approach for rational design |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Engineers specific interactions and dependencies | Bottom-up approach for creating synthetic interactions |

| Antibiotic Markers | Maintains plasmid stability and tracks strains | Both approaches for community management |

Advanced Strategy: Integrated Top-Down/Bottom-Up Framework

To effectively mitigate reduced interactions in synthetic communities, researchers are increasingly adopting a hybrid framework that integrates both approaches:

This integrated approach leverages the functional robustness of natural communities identified through top-down methods with the precision and control of bottom-up engineering, creating synthetic communities with both high functionality and stability while effectively mitigating reduced interactions.

Metabolic Modeling for Predicting Interaction Potential and Resource Overlap

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) and Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO), and why are they important for community stability?

Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) reflects the cooperative potential within a community through metabolic exchanges, while Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) indicates the competitive pressure due to shared resource use. These metrics are pivotal for determining community coexistence and stability. Research has demonstrated that narrow-spectrum resource-utilizing (NSR) strains consistently contribute to elevated MIP scores, whereas broad-spectrum resource-utilizing (BSR) strains are associated with higher MRO. A clear negative correlation exists between resource utilization width and MIP, and a positive correlation with MRO, making these metrics essential for predicting community assembly and stability [11].

2. How can I use genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to predict interactions in my synthetic community?

Genome-scale metabolic modeling provides a powerful framework to investigate metabolic interdependencies. The standard workflow involves:

- Model Reconstruction: Developing a mathematical representation of the metabolic network for each organism based on its genome annotation. Tools like CarveMe or ModelSEED can be used for automated draft reconstruction [18].

- Model Integration: Combining individual GEMs into a unified community model, often using standardized namespaces like MetaNetX to resolve inconsistencies [18].

- Simulation and Analysis: Using Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) methods, such as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), to simulate metabolic fluxes and calculate key indices like MIP and MRO for different community combinations [11] [18].

3. My synthetic community consistently collapses, with one species outcompeting all others. What could be the cause and how can I mitigate this?

Community collapse is often driven by excessive competition. Your community may be dominated by a broad-spectrum resource-utilizing (BSR) strain with high metabolic resource overlap (MRO), leading to the exclusion of other members [11].

- Solution: Incorporate narrow-spectrum resource-utilizing (NSR) strains. Experimental and modeling results show that strains with specialized metabolic niches have lower MRO and higher MIP, which reduces competitive pressure and fosters stable coexistence. For instance, in a study, Cellulosimicrobium cellulans E, an NSR strain, acted as a central node in the metabolic network and was key to community stability [11].

4. What experimental methods can I use to validate the metabolic interactions predicted by my models?

Model predictions require experimental validation. Key methodologies include:

- Phenotype Microarrays: Profile the ability of individual strains to utilize various carbon sources. This data can be used to calculate resource utilization width and overlap, and to refine your GEMs [11].

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR) with Strain-Specific Primers: Accurately quantify the abundance of each member species in the community over time to track compositional changes and stability [19].

- "Removal" Experiments: Systematically drop individual species from the "full" community and measure the impact on total community biomass and composition. This helps identify keystone species whose removal significantly alters community function [19].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem: Unstable community composition during serial passaging.

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid loss of member species; dominance by a single strain. | High metabolic resource overlap (MRO) leading to intense competition; lack of cooperative cross-feeding. | 1. Re-design community to include narrow-spectrum resource-utilizing strains to lower MRO [11].2. Use GEMs to screen candidate strains for high MIP before assembly [11]. |

| Fluctuating species ratios between cycles. | Stochastic variation in species biomass during the reproduction of Newborn communities. | 1. Standardize the inoculation protocol to reduce biomass fluctuations [20].2. Ensure Resource is non-limiting during maturation to prevent drift [20]. |

Problem: Failure to achieve the desired emergent community function (e.g., biomass production, metabolite secretion).

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Community function is lower than the sum of individual functions. | Presence of competitive or antagonistic interactions; keystone species missing. | 1. Perform co-occurrence network analysis to identify and exclude negatively correlated strains [19].2. Identify keystone species via "removal" experiments and ensure their presence [19]. |

| Costly community function fails to improve despite selection. | Intracommunity selection favors "cheater" strains that do not contribute to the function but grow faster. | 1. Apply selective pressure at the community level (intercommunity selection) to favor groups with high contributors [20].2. Genetically engineer mutual dependency to stabilize cooperation [20]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Community Biomass and Composition

Objective: To track the dynamic changes in community biomass and the abundance of individual member species.

Materials:

- Synthetic community members

- Appropriate growth medium

- Sterile culture tubes or microplates

- Filter membranes (for pellicle biofilm harvest)

- Dry-weight balance

- qPCR instrument

- Strain-specific primers [19]

Methodology:

- Community Cultivation: Inoculate the synthetic community in a suitable medium. For biofilm communities, use static cultures to allow pellicle formation at the air-liquid interface [19].

- Biomass Harvesting: At designated time points (e.g., 24h, 36h, 48h), carefully harvest the pellicle biofilm.

- Wet and Dry Weight Measurement: Measure the wet weight immediately. Then, dry the biomass to a constant weight at a defined temperature (e.g., 60°C) and record the dry weight [19].

- DNA Extraction and qPCR: Extract total genomic DNA from the community biomass. Perform quantitative PCR (qPCR) using pre-validated, strain-specific primers to quantify the absolute abundance of each member species [19].

Protocol 2: In silico Screening of Strains Using Metabolic Models

Objective: To predict the interaction potential and resource overlap of candidate strains before experimental assembly.

Materials:

- Genome sequences of all candidate strains

- Metabolic model reconstruction software (e.g., CarveMe, ModelSEED)

- COBRA toolbox or similar simulation environment

- Phenotype microarray data (Biolog) for model refinement [11]

Methodology:

- Model Reconstruction: For each candidate strain, reconstruct a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM). This can be done automatically from genome sequences using tools like CarveMe [18].

- Model Refinement: Refine the draft models using experimental data, such as carbon source utilization profiles from phenotype microarrays, to improve predictive accuracy [11].

- Community Simulation: Combine the individual GEMs to simulate all potential community combinations (pairwise or higher). Use flux balance analysis (FBA) to compute community-level objectives.

- Calculate MIP and MRO: For each simulated community, calculate the Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) and Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) [11].

- Strain Selection: Select strains for your final SynCom that, in combination, exhibit high MIP and low MRO to maximize stability [11].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: SynCom Design and Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Metabolic Modeling and Analysis Process

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for constructing and analyzing synthetic microbial communities.

| Item | Function/Benefit | Key Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Strain-Specific qPCR Primers | Enables precise, absolute quantification of each species' abundance in a multi-species community. | Tracking dynamic compositional changes in a 6-member SynCom over time [19]. |

| Phenotype Microarrays (Biolog) | High-throughput profiling of carbon source utilization; used to calculate resource utilization width and refine GEMs. | Differentiating narrow-spectrum and broad-spectrum resource-utilizing strains to predict MRO [11]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | A mathematical representation of an organism's metabolism; predicts metabolic fluxes and interactions in silico. | Screening all possible strain combinations for high MIP and low MRO before lab assembly [11] [18]. |

| Constrained-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox | Software for simulating metabolism using GEMs, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). | Calculating the exchange of metabolites (cross-feeding) in a simulated community to estimate cooperation [18]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

FAQ: Why is my synthetic community (SynCom) unstable, with some strains being outcompeted over time?

- Problem: This is a frequent challenge caused by uncontrolled competitive interactions or the emergence of "cheater" strains that benefit from the community without contributing functionality [21].

- Solutions:

- Genomic Screening: Prior to assembly, screen candidate strains for antagonistic genes, such as biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for antibiotics, to minimize negative interactions [21].

- Spatial Structuring: Use solid or semi-solid growth media (e.g., agar). Spatial structure confines microenvironments, alters quorum sensing dynamics, and helps stabilize cooperative interactions by controlling the distribution of public goods [21].

- Engineer Interdependence: Design the community so that strains are obligately cross-feeding essential metabolites, creating mutual dependence. Computational tools like DOLMN can help identify non-intuitive metabolic partitions that enforce this [22].

FAQ: My consortia show high functional variability between replicate experiments. How can I improve reproducibility?

- Problem: Inconsistent community assembly and inoculation can lead to high variability in the final composition and function.

- Solutions:

- Standardized Protocols: Implement highly structured assembly methods. The full factorial construction protocol using multichannel pipettes and 96-well plates ensures consistent and rapid assembly of all possible strain combinations, reducing human error and contamination risk [23].

- Precise Inoculation Ratios: Use optical density (OD) measurements or cell counting to standardize the starting cell density of each strain in the consortium. The full factorial method provides a reproducible framework for this [23].

- Monitor Dynamics: Use longitudinal sampling and techniques like plating or qPCR to track the population dynamics of each strain over time, rather than just measuring the final output [21].

FAQ: The SynCom performs well in the lab but fails to maintain its function in a more complex, natural environment.

- Problem: The controlled conditions of the lab do not fully replicate the biotic and abiotic stresses of a natural environment (e.g., soil, host gut) [12].

- Solutions:

- Include Keystone Species: Incorporate microbial strains identified as "keystones" from the target environment. These species play a disproportionately large role in structuring the community and can enhance ecological robustness [21].

- Pilot in Simulated Environments: Before full field deployment, test SynComs in microcosms or growth chambers that simulate key aspects of the target environment, such as soil type, pH, or temperature fluctuations [12].

- Top-Down Refinement: Instead of a purely bottom-up design, start with a complex natural community from the target environment and progressively refine it into a reduced SynCom. This preserves evolved ecological relationships [21].

Quantitative Data for SynCom Design

Table 1: Stability and Performance Metrics in Synthetic Communities

| Design Factor | Impact on Stability & Function | Experimental Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Community Diversity | High diversity can enhance stability and pathogen resistance, but can also intensify competition under nutrient limitation [21]. | 16S/ITS rRNA amplicon sequencing; Metagenomic sequencing. |

| Interaction Type | Mutualism and commensalism (e.g., cross-feeding) increase resilience. Antagonism and competition can destabilize consortia [21]. | Pairwise co-culture growth assays; Metabolite profiling (LC-MS/GC-MS). |

| Spatial Structure | Confined microenvironments in structured media stabilize cooperation and suppress cheating behavior [21]. | Confocal microscopy; Spatial metabolomics. |

| Metabolic Partitioning | Partitioning pathways like the TCA cycle across strains can provide a competitive advantage under reaction constraints [22]. | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA); Genome-scale metabolic modeling. |

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Methods for SynCom Design

| Method/Tool | Primary Function | Key Inputs | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOLMN (Division of Labor in Metabolic Networks) | Identifies optimal ways to split a metabolic network across specialized strains to enable survival under constrained conditions [22]. | Global metabolic network; Number of strains; Constraints on intracellular/transport reactions [22]. | Partitioned subnetworks for each strain; Growth rates; Patterns of exchanged metabolites [22]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Predicts metabolic flux distribution to maximize biomass production or other objectives [22]. | Genome-scale stoichiometric model; Nutrient uptake rates [22]. | Growth rate prediction; Reaction flux values; Essentiality of reactions [22]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Models | Optimizes SynCom parameters and predicts microbial interactions from complex datasets [21]. | Genomic data; Metabolomic data; Historical performance data [21]. | Predictions of community function; Identification of key interacting strains [21]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing Metabolic Division of Labor Using DOLMN

This protocol uses the Division of Labor in Metabolic Networks (DOLMN) method, formulated as a mixed-integer linear programming problem, to computationally design a consortium where strains partition a metabolic pathway [22].

1. Define Inputs and Constraints:

- Global Network: Obtain a genome-scale stoichiometric model (e.g., for E. coli) from databases like BiGG or ModelSEED. This model is represented by a stoichiometric matrix S with associated flux bounds [22].

- Number of Strains (K): Define the number of strains (K) in the target consortium [22].

- Reaction Constraints: Set the maximum number of intracellular reactions (

TIN) and transport reactions (TTR) allowed per strain. These constraints should be strict enough to prevent any single strain from growing in isolation [22].

2. Run DOLMN Optimization:

- The optimization algorithm searches for a binary vector

tthat indicates the presence/absence of each reaction in each strain, and a continuous flux vectorxfor all reaction rates [22]. - The solution must satisfy that each strain's subnetwork is functional and can produce biomass precursors, and that all strains in the coculture have equal growth rates for stable coexistence [22].

3. Analyze Output and Validate:

- The key output is the partitioned metabolic network for each strain, revealing the split of pathways (e.g., splitting the TCA cycle into two separate halves) [22].

- The model will also predict the metabolites that are cross-fed between the strains [22].

- Experimental Validation: Genetically engineer the predicted strains using gene knockout techniques (e.g., λ-Red recombineering) to match the computed reaction sets. Co-culture the strains in a chemostat or batch culture and measure growth rates and metabolite exchange to validate the predicted division of labor [22].

Protocol 2: Full Factorial Construction of Microbial Consortia

This protocol provides a method to empirically assemble and test all possible combinations from a library of microbial strains, enabling the mapping of community-function landscapes [23].

1. Prepare Strain Library and Media:

- Grow each of the

mcandidate strains in isolation to the same growth phase (e.g., mid-exponential phase). - Standardize the cell density (e.g., by OD600) for each culture.

- Prepare a fresh, sterile medium for the co-culture experiment.

2. Logical Assembly in a 96-Well Plate:

- The method uses a 96-well plate and relies on representing each consortium by a unique binary number, where each bit represents the presence (1) or absence (0) of a specific strain [23].

- Step-by-Step Assembly:

- Begin with the first column containing all combinations of the first three strains. Each of the 8 wells in the column represents a unique binary combination from

000to111[23]. - Duplicate these 8 consortia into the second column. Using a multichannel pipette, add the fourth strain (

1000) to every well in this second column. This generates all 16 combinations of the first four strains (binary0000to1111) [23]. - Repeat this process of duplication and addition for the remaining strains. Duplicating the existing combinations and adding a new strain to half of the new wells systematically generates all

2^mpossible consortia [23].

- Begin with the first column containing all combinations of the first three strains. Each of the 8 wells in the column represents a unique binary combination from

3. Measure Community Function:

- Incubate the plate under desired conditions.

- Measure the target function(s) for each well (e.g., total biomass via absorbance, product formation via HPLC, or pathogen inhibition via zone-of-inhibition assays) [23].

- This full factorial data allows you to identify the optimal strain combination and dissect all pairwise and higher-order interactions that influence the community's function [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for SynCom Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function in SynCom Research |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) | Computational models that predict metabolic capabilities and outcomes of metabolic division of labor from genomic data [22]. |

| Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | The optimization framework used by tools like DOLMN to solve the combinatorial problem of partitioning metabolic reactions across strains [22]. |

| 96-Well Microtiter Plates | Standardized platform for high-throughput cultivation and assembly of microbial consortia, essential for full factorial designs [23]. |