Retroactivity in Synthetic Gene Networks: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

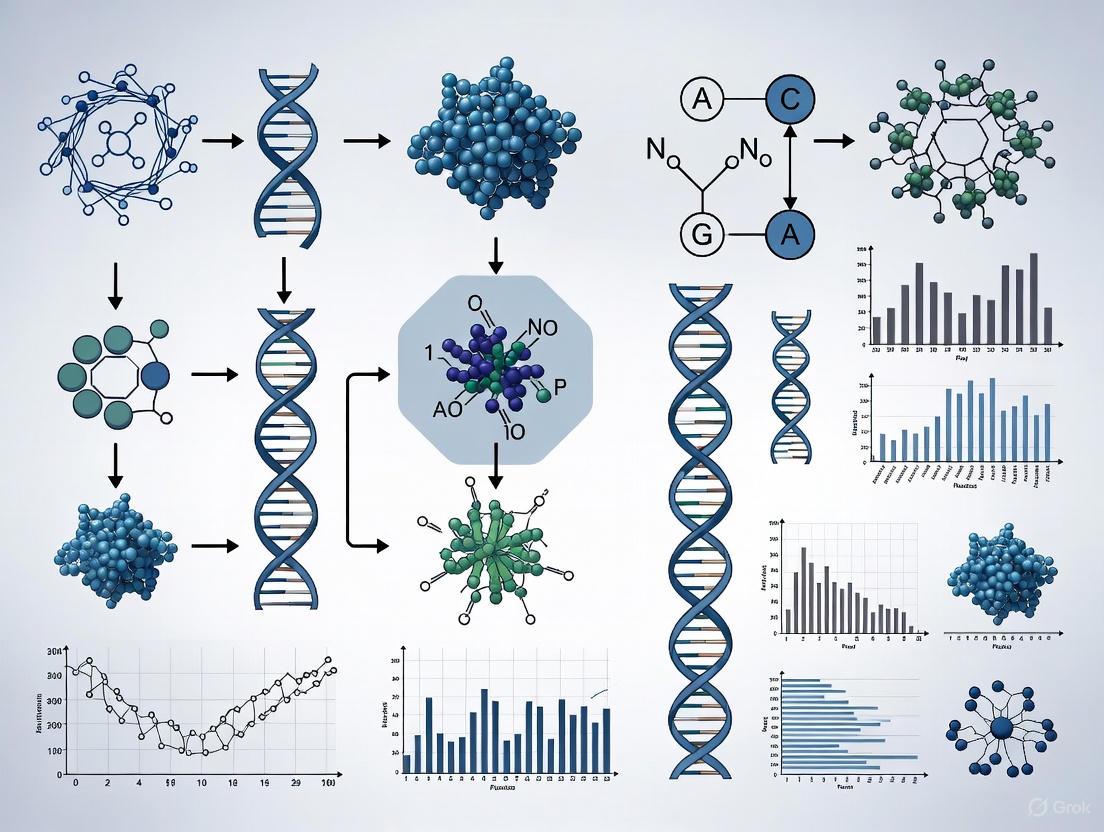

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of retroactivity, a critical form of context-dependence in synthetic gene networks where downstream modules adversely interfere with upstream components by sequestering or modifying signals.

Retroactivity in Synthetic Gene Networks: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of retroactivity, a critical form of context-dependence in synthetic gene networks where downstream modules adversely interfere with upstream components by sequestering or modifying signals. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational mechanisms of retroactivity and its interplay with other circuit-host interactions like resource competition. The content details methodological advances for mitigating retroactivity, including embedded control strategies and load driver devices, and offers troubleshooting frameworks for optimizing circuit predictability and performance. Finally, we examine the validation of these strategies across biological systems and their pivotal implications for enhancing the safety and efficacy of next-generation biomedical applications, such as smart cell therapies and regulated metabolic treatments.

Understanding Retroactivity: Defining the Hidden Interactions in Your Gene Circuit

In synthetic biology, the engineering of biological systems often follows a modular paradigm, where complex circuits are assembled from simpler, well-characterized functional units. A core challenge in this endeavor is retroactivity, a reactive phenomenon where the interconnection of modules leads to signals propagating from downstream modules back to upstream ones [1]. This phenomenon, analogous to the concept of impedance in electrical circuits, can fundamentally alter or even disrupt the intended behavior of a synthetic genetic circuit [1] [2]. When a downstream module sequesters or modifies the signals produced by an upstream module, it imposes a load on the upstream system, changing its dynamics in ways that are difficult to predict from the characterization of the isolated modules [3]. Consequently, biological systems are increasingly considered quasi-modular rather than perfectly modular, as the functional independence of components is constrained by these interconnections [1]. Understanding and mitigating retroactivity is therefore critical for the predictable design of complex synthetic gene networks in applications ranging from therapeutic drug development to biosensing.

The Fundamental Mechanism of Signal Sequestration

At its core, retroactivity in biomolecular systems is driven by molecular sequestration. This occurs when a protein or signaling molecule produced by an upstream module is bound and sequestered by a downstream component, making it unavailable for its primary signaling role.

In a typical two-module system, the upstream module produces an output signal, often an activated transcription factor (e.g., a phosphorylated protein, denoted X), which serves as the input for the downstream module. The downstream module contains specific target sites or signaling partners (e.g., promoters or other proteins) that bind X. This binding forms a complex, effectively reducing the concentration of free X* [2]. The formation of this intermediate complex is the key molecular event that couples the two modules. From a kinetics perspective, this sequestration acts as an additional drain on the upstream output, altering its apparent degradation rate and steady-state concentration [1] [2]. The strength of the retroactive effect is determined by the biochemical parameters of the interaction, including the affinity (dissociation constant) between X* and its downstream target, and the total concentration of the downstream target sites [2]. This mechanism is ubiquitous in natural signaling pathways, such as the ExsADCE regulatory cascade in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, where a series of protein sequestrations precisely controls the expression of virulence factors [4].

Table 1: Key Parameters Influencing Retroactive Effects

| Parameter | Symbol | Impact on Retroactivity |

|---|---|---|

| Total Downstream Target Concentration | ( S_{tot} ) | A higher ( S_{tot} ) increases the capacity for signal sequestration, leading to stronger retroactive effects [2]. |

| Affinity (Dissociation Constant) | ( K_d ) | A lower ( K_d ) (tighter binding) results in more stable complex formation and stronger retroactivity [2]. |

| Upstream Output Production Rate | ( k_{prod} ) | A higher production rate can partially compensate for sequestration, potentially mitigating the observable impact of retroactivity. |

| Phosphatase/Deactivation Rate | ( k_{deact} ) | Alters the steady-state concentration of the active signal (e.g., X*), thereby influencing the fraction that is sequestered [2]. |

Quantitative Analysis of Retroactivity in Signaling Pathways

The impact of retroactivity can be quantified by analyzing how the input-output (I/O) response of the upstream module is distorted upon connection to a downstream load. Analytical models reveal the conditions under which these effects are most pronounced.

For a signaling cascade composed of covalent modification cycles (e.g., phosphorylation cycles), the steady-state concentration of the active protein in the upstream cycle (X*) is a function of both its intrinsic kinetic parameters and the parameters of the downstream cycle. When the downstream module is present, the fraction of active upstream protein is generally reduced due to sequestration [2]. The retroactivity magnitude (R) can be defined as the relative change in the upstream output for a given input:

( R = \frac{|X^_{isolated} - X^{connected}|}{X^*{isolated}} )

Studies show that retroactivity is particularly strong in short signaling pathways and when the total concentration of the downstream protein (( Y_{tot} )) is high relative to the upstream protein [2]. For instance, in a bicyclic cascade, varying the total amount of downstream protein can shift the upstream system from a state of minimal retroactivity to one where its activity is significantly suppressed [2]. Furthermore, variations in the activity of the phosphatase that deactivates the downstream protein can also propagate upstream, altering the steady state of the first cycle [2]. This quantitative framework allows researchers to predict whether a circuit design will exhibit significant retroactive effects and to identify the most sensitive parameters.

Table 2: Impact of System Parameters on Retroactivity in a Bicyclic Cascade

| Parameter Variation | Effect on Upstream (X*) | Typical Experimental Range |

|---|---|---|

| Increase in Downstream Protein (( Y_{tot} )) | Decrease in free X* concentration [2] | 0.1 - 10 μM |

| Increase in Downstream Phosphatase | Non-monotonic effect; can increase or decrease X* depending on initial conditions [2] | 0.1 - 10 μM |

| Increase in Upstream Kinase | Can partially overcome sequestration, increasing X* [2] | 0.1 - 5 μM |

| Tighter Binding (Lower ( K_d )) | Greater decrease in free X* [2] | 0.001 - 1 μM |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Retroactivity

Constructing a Synthetic Sequestration Cascade

To empirically study retroactivity, a defined experimental system must be constructed. A prominent example is the reconstruction of the ExsADCE sequestration cascade from P. aeruginosa in a heterologous host like E. coli [4].

Materials:

- Plasmids: Engineered plasmids carrying genes for the regulatory proteins (e.g.,

exsA,exsD,exsC,exsE) under the control of inducible promoters (e.g., pBAD, pTet, pLux). A reporter plasmid with GFP under the control of an ExsA-dependent promoter is essential [4]. - Strain: E. coli DH10B or another suitable strain with minimal background [4].

- Media: Defined minimal media (e.g., M9) supplemented with necessary nutrients and antibiotics for plasmid maintenance [4].

- Inducers: Small molecules to control gene expression, such as Arabinose (Ara), anhydrotetracycline (aTc), and AHL (3OC6) [4].

Methodology:

- Circuit Assembly: Genetic circuits are assembled using techniques like Golden-Gate DNA assembly, which allows for the modular combination of genetic parts [4].

- Transformation: Electro-competent E. coli are transformed with the constructed plasmids, and frozen stocks are created for reproducibility [4].

- Culture and Induction: Overnight cultures are grown with aTc to repress the system ("OFF-state"). Cells are washed and subcultured into fresh media with varying concentrations of inducers (Ara, aTc, 3OC6) to activate the cascade components to different degrees [4].

- Data Collection: After a defined period (e.g., 8 hours), population-level fluorescence (GFP) and optical density (Abs600) are measured using a plate reader. Flow cytometry can provide single-cell resolution data [4].

- Data Analysis: Fluorescence values are converted to Relative Expression Units (REU) by normalizing against a constitutive GFP reference strain. This standardization allows for comparison across different experiments and labs [4].

Quantifying Retroactivity from Fluorescence Data

The protocol above yields data to quantify retroactivity's effect. For a two-module system where Module 1 drives GFP expression and Module 2 sequesters Module 1's output:

- Measure Isolated Performance: Characterize the GFP output of Module 1 (with a control plasmid) across a range of its input inducer concentrations.

- Measure Connected Performance: Characterize the GFP output of Module 1 when it is connected to Module 2, across the same range of input concentrations.

- Calculate Retroactivity: For each input level, compute the retroactivity magnitude ( R ) using the formula ( R = \frac{|GFP{isolated} - GFP{connected}|}{GFP_{isolated}} ). This generates a curve showing how retroactivity depends on the operating point of the system.

- Statistical Validation: Use statistical tests like a t-test to confirm that the differences between isolated and connected outputs are significant and not due to random chance. An F-test should first be used to verify the equality of variances between the two data sets before selecting the appropriate t-test [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Retroactivity

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Inducers | Provide independent control over the expression of different circuit modules. | Arabinose (pBAD), aTc (pTet), AHL (pLux). Used to titrate the production of upstream and downstream proteins [4]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Quantify the activity of a specific module in real-time. | GFP, RFP, etc., placed under the control of a promoter responsive to the upstream module's output [4]. |

| Protein Expression Plasmids | Harbor genes for the signaling proteins that constitute the cascade. | Plasmids with different origins of replication and resistance for compatible co-expression of ExsA, ExsD, ExsC, and ExsE [4]. |

| "Load Driver" Device | A synthetic device designed to mitigate the effects of retroactivity. | Engineered to maintain consistent output despite variable downstream load, acting as an insulator between modules [3]. |

| Golden-Gate Assembly System | Enables modular, hierarchical, and standardized construction of genetic circuits. | Uses type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI, BsmBI) to assemble multiple genetic parts in a single reaction [4]. |

Implications for Synthetic Gene Network Research

The phenomenon of retroactivity has profound implications for the design and implementation of synthetic gene circuits, particularly as they increase in complexity. It is a primary source of context-dependence, where a module's behavior changes unpredictably when removed from isolation and placed into a larger circuit or a new cellular host [3]. This contravenes the foundational engineering principle of modularity and leads to lengthy design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycles [3].

Retroactivity is also intertwined with other global cellular constraints, such as resource competition and growth feedback. Circuits compete for a finite pool of shared cellular resources, like RNA polymerase and ribosomes. A downstream module that suddenly draws significant resources can indirectly impair the function of an upstream module, creating a form of indirect retroactivity [3]. Furthermore, circuit activity can burden the host cell, reducing its growth rate. This slower growth alters the effective dilution rate of all cellular proteins, creating a feedback loop that can change the circuit's quantitative dynamics, sometimes leading to emergent behaviors like bistability or the loss of desired states [3]. Emerging strategies to overcome these challenges include the use of machine learning to model complex, uncharacterized circuit-host interactions and the development of hybrid modeling approaches that combine mechanistic models with data-driven methods to improve predictive design [6].

Distinguishing Retroactivity from Resource Competition and Other Context-Dependent Effects

Synthetic biology aims to program living cells with predictable genetic circuits for applications in health, agriculture, and biotechnology. However, the behavior of these engineered systems is often confounded by context-dependent effects, where circuit performance is influenced by interactions with the host cell's native machinery [3]. Two of the most significant sources of this context dependence are retroactivity and resource competition. While both can alter a circuit's intended function, they stem from fundamentally different mechanisms. Retroactivity describes the unintended loading effect that a downstream module imposes on an upstream module by sequestering its signaling molecules [3] [7] [8]. In contrast, resource competition arises when multiple genetic modules concurrently draw from a finite, shared pool of cellular resources, such as RNA polymerase (RNAP), ribosomes, nucleotides, and energy [3] [9]. Accurately distinguishing between these phenomena is not an academic exercise; it is a critical prerequisite for diagnosing circuit failures and implementing effective mitigation strategies during the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle. This guide provides a technical framework for differentiating retroactivity from resource competition and other contextual factors, equipping researchers with the methodologies to deconvolve these effects in their synthetic gene networks.

Defining Core Concepts and Their Mechanisms

Retroactivity: Signal Sequestration and Interference

Retroactivity is an input-output phenomenon that manifests when a downstream system (e.g., a reporter gene or another circuit module) connects to and interferes with an upstream system [3] [8]. The primary mechanism involves the sequestration of active signaling molecules, such as transcription factors (TFs), by specific binding sites on the DNA of the downstream module.

- Mechanism: When a downstream promoter contains binding sites for an upstream transcription factor, it directly competes for the free TF pool. This connection increases the total number of binding sites in the cell, effectively titrating the TF and reducing its free concentration [7] [8]. This sequestration can slow the response dynamics of the upstream module and alter its steady-state behavior, potentially disrupting key functions like oscillations [7].

- Analogy: This is analogous to an electrical circuit where connecting a low-impedance downstream component "loads" the upstream driver, causing a voltage drop and slowing the transient response.

Resource Competition: Global Scarcity and Coupling

Resource competition, unlike the direct signaling interference of retroactivity, is a global, cell-wide phenomenon. It occurs when multiple genes—both synthetic and native—compete for the same limited, essential cellular resources [3] [9].

- Mechanism: The core machinery for gene expression exists in finite quantities. During transcription, RNAPs and nucleotides are limiting. During translation, ribosomes, transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and amino acids are shared [3]. High expression from a synthetic circuit can drain these shared pools, leading to a phenomenon known as "cellular burden" [3]. This burden often reduces host cell growth, which in turn increases the dilution rate of circuit components, creating a complex growth feedback loop [3].

- Key Distinction: Resource competition introduces unintended coupling between otherwise independent modules. For example, the induced expression of one gene can suppress the expression of another, unrelated gene simply because both are drawing from the same resource pool [9]. In bacterial systems, competition for translational resources (ribosomes) is often the dominant constraint, whereas in mammalian cells, competition for transcriptional resources (RNAP) is more significant [3].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics that differentiate retroactivity, resource competition, and other common contextual factors.

Table 1: Characteristics of Key Context-Dependent Effects in Synthetic Biology

| Effect Type | Primary Mechanism | Scope of Impact | Key Observable Signatures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retroactivity | Sequestration of specific signaling molecules (e.g., TFs) by downstream binding sites [3] [7] [8]. | Localized to connected modules. | Slowed response time of the upstream module; altered steady-state levels; disruption of dynamics (e.g., oscillations) [7] [8]. |

| Resource Competition | Competition for global, shared expression resources (RNAP, ribosomes, ATP, amino acids) [3] [9]. | Global, affecting all circuits and host processes. | Negative correlation between expression of independent genes; reduced host cell growth rate; "winner-takes-all" gene expression [3] [9]. |

| Growth Feedback | Circuit burden reduces growth, altering dilution rates of all cellular components [3]. | Global, coupled with resource competition. | Emergence or loss of bistability; changes in circuit output linked to measured growth rates [3]. |

| Intergenic Context | Effects from genetic part order, orientation, and DNA supercoiling [3]. | Localized to the genetic construct. | Altered expression levels based on gene syntax (convergent, divergent, tandem); bidirectional feedback between adjacent genes [3]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Distinction

A systematic experimental approach is required to disentangle these intertwined effects. The following protocols and visual guides outline a pathway for diagnosis.

A Diagnostic Workflow for Effect Identification

The diagram below outlines a sequential experimental workflow to identify the root cause of observed circuit dysfunction.

Diagram 1: A diagnostic workflow for distinguishing context-dependence.

Protocol 1: Quantifying Retroactivity via Noise Analysis

This protocol leverages the principle that retroactivity increases the response time of a transcription factor, which is reflected in its expression noise profile [8].

- Objective: To measure the retroactivity imposed by a downstream reporter gene on an upstream oscillator circuit.

- Experimental Setup:

- Strain Construction: Implement a well-characterized synthetic genetic oscillator (e.g., a repressilator or dual-feedback oscillator) in E. coli [7].

- Reporter Variants: Create two strains with the same oscillator circuit but different downstream reporters:

- Strain A (Low Load): A reporter with a low-copy-number promoter (fewer TF binding sites).

- Strain B (High Load): A reporter with a high-copy-number promoter (more TF binding sites) [7].

- Methodology:

- Time-Lapse Microscopy: Conduct single-cell time-lapse fluorescence microscopy for both strains under identical conditions.

- Data Collection: Track the fluorescence of a circuit component (e.g., a constitutively expressed reference protein) and the reporter output over multiple oscillation periods for a large number of individual cells.

- Noise Calculation: For each strain, calculate the autocorrelation function of the gene expression noise from the time-series data. The decay time (correlation time) of this autocorrelation function is a direct measure of the slow-down in the TF's dynamics [8].

- Expected Outcome: Strain B (high load) will exhibit a significantly longer correlation time in its noise signature compared to Strain A (low load), confirming the presence of retroactivity [8]. The total output noise may also be higher in Strain B.

Protocol 2: Probing Resource Competition via Orthogonalization

This protocol tests whether observed coupling between modules is alleviated by reducing competition for shared resources.

- Objective: To determine if competition for ribosomes is the cause of suppressed expression in a two-gene cascade.

- Experimental Setup:

- Control Circuit: Construct a plasmid with two independent genes (e.g., GFP and RFP), each under the control of identical, inducible promoters.

- Test Circuit: Construct a similar plasmid where the RFP gene's coding sequence has been codon-optimized to use an orthogonal set of tRNAs, thereby minimizing competition with GFP and native genes for the host's natural tRNA and ribosome pools [9].

- Methodology:

- Cultivation & Induction: Transform both constructs into the host organism and grow cultures in identical conditions. Induce gene expression with a sweep of inducer concentrations.

- Flow Cytometry: At each inducer level, use flow cytometry to measure the single-cell fluorescence of GFP and RFP for thousands of cells.

- Data Analysis: Plot the mean GFP expression versus mean RFP expression for the control and test circuits.

- Expected Outcome: In the control circuit, a strong negative correlation between GFP and RFP expression (following an "isocost line") is expected [9]. In the test circuit using orthogonal resources, this negative correlation should be significantly weakened or eliminated, confirming that resource competition was the primary coupling mechanism [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successfully executing these diagnostic experiments requires carefully selected genetic parts and host strains. The following table catalogs key research reagents.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Context-Dependence

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Utility | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Copy vs. High-Copy Plasmids | To vary the copy number of binding sites and test for retroactivity [7]. | Plasmid backbones with different replication origins (e.g., pSC101 vs. pUC). Allows controlled titration of specific load. |

| Orthogonal Codon-Optimized Genes | To reduce competition for the host's native translational machinery [9]. | Genes recoded to use alternative codons without changing the amino acid sequence. |

| Fluorescent Protein Reporters | To provide quantitative, real-time readouts of gene expression at single-cell resolution. | Proteins like GFP, RFP, and their derivatives with distinct excitation/emission spectra [7] [9]. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems | To provide precise, tunable control over the expression level of circuit components. | Promoters induced by small molecules (e.g., aTc, IPTG, Arabinose) enabling dose-response experiments [7] [9]. |

| Tag-Specific Protease Systems | To study resource competition at the protein degradation level [7]. | A system where both circuit and reporter proteins share a degradation tag (e.g., ssrA) that is recognized by a specific, limited protease (e.g., ClpXP). |

A Practical Diagram of Retroactivity vs. Resource Competition

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic differences between retroactivity and resource competition, highlighting their distinct pathways of interference.

Diagram 2: Mechanisms of retroactivity versus resource competition.

Mastering the distinction between retroactivity and resource competition is fundamental to advancing synthetic biology from a trial-and-error discipline to a predictive engineering science. As outlined in this guide, each phenomenon has a distinct origin: retroactivity arises from specific molecular connections between modules, while resource competition stems from global scarcity. The diagnostic workflows, experimental protocols, and reagent toolkit provided here empower researchers to deconvolve these effects in their systems. Implementing load-driving devices to buffer against retroactivity and employing orthogonal genetic parts to mitigate resource competition are the logical next steps informed by accurate diagnosis [3]. This precise understanding enables the robust design of complex synthetic gene circuits, accelerating their deployment in real-world applications, including the development of novel cell-based assays and therapeutic strategies [10].

In synthetic biology, the predictable engineering of genetic circuits is fundamentally challenged by context-dependent phenomena, where a circuit's behavior is influenced by its specific genetic environment and host cell. Among these, retroactivity has emerged as a critical barrier to modular design. Retroactivity refers to the phenomenon where a downstream node in a genetic network adversely affects or interferes with an upstream node in an unintended manner [3]. This interference occurs when downstream components sequester or modify the signals used by upstream components, leading to unexpected changes in network dynamics and a failure of the circuit to perform as designed [3].

The topology of a genetic circuit—the physical arrangement and interconnection of its genetic parts—is a primary determinant of its susceptibility to retroactivity. This topology can be decomposed into intergenic context (the potential interactions between genes or genetic parts that affect the regulation and expression of a gene and its neighbors) and circuit syntax (the relative order and orientation of genes in a construct) [3]. Understanding how these topological features influence retroactivity is essential for creating robust, predictable biological systems that obey engineering principles of modularity and isolation, much like their electronic counterparts.

Core Concepts: Syntactic Elements and Their Functional Consequences

Fundamental Syntactic Arrangements

Circuit syntax involves three basic orientations for two adjacent operons on a DNA molecule [3]:

- Convergent Orientation: Transcription proceeds towards each other.

- Divergent Orientation: Transcription proceeds away from each other.

- Tandem Orientation: Transcription proceeds in the same direction, one after the other.

The specific syntax chosen for a circuit is not merely a structural detail; it directly governs the biochemical interactions between transcriptional machinery and the DNA template, leading to profound functional consequences.

The Mechanism of DNA Supercoiling

The primary mechanism through which syntax exerts its effect is DNA supercoiling [3]. As RNA polymerase transcribes a gene, it unwinds the DNA double helix ahead of it. This action creates mechanical stress that manifests as supercoiling:

- Positive Supercoiling occurs ahead of the transcription bubble, where the DNA helix is overwound. This tight coiling can slow down transcription initiation and halt elongation [3].

- Negative Supercoiling occurs behind the transcription bubble, where the DNA is underwound. This generally facilitates transcription initiation by making it easier for the DNA to unwind [3].

The expression of a gene can be actively altered by supercoiling caused by the expression of upstream genes. Whether these effects are activatory, inhibitory, or neutral is highly dependent on the circuit syntax and its boundary conditions (e.g., circular plasmid or linear chromosome) [3].

Table 1: Functional Consequences of Different Gene Syntaxes

| Syntax Type | Impact on Supercoiling | Effect on Transcription | Potential for Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convergent | Accumulation of positive supercoiling in the intergenic region | Mutual inhibition; slows transcription | High (Bidirectional) |

| Divergent | Accumulation of negative supercoiling in the intergenic region | Can enhance mutual transcription | High (Bidirectional) |

| Tandem | Directional propagation of supercoiling | Can enhance or inhibit downstream genes | Moderate (Unidirectional) |

Emergence of Supercoiling-Mediated Feedback

Under certain syntactic arrangements, supercoiling effects from multiple operons can influence each other, forming supercoiling-mediated feedback [3]. For instance, in a toggle switch circuit, the accumulation of positive or negative supercoiling in the intergenic region has been demonstrated to, respectively, enhance or diminish mutual inhibition between genes expressed in convergent or divergent manners [3]. This means two adjacent genes can affect each other's transcription activity and dynamics, creating a bidirectional feedback loop that adds a layer of complexity to synthetic gene circuit design [3].

Quantitative Effects of Topology on Circuit Performance

The topological features of a genetic circuit are not just theoretical concerns; they produce quantifiable, and sometimes drastic, effects on circuit performance. These effects can be measured through key parameters such as output signal strength, response time, and steady-state stability.

The phenomenon of retroactivity can be quantitatively assessed by measuring the change in the output of an upstream module when a downstream module is connected. A significant drop in output or a drastic change in dynamics indicates high retroactivity. Furthermore, the different syntactic arrangements lead to measurable differences in the expression levels of constituent genes. For instance, divergent orientations often yield higher co-expression due to shared negative supercoiling, while convergent orientations can lead to mutually suppressed expression.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Circuit Topology on Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | Influence of Intergenic Context | Influence of Syntax & Supercoiling | Experimental Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Output Signal Strength | High retroactivity can severely diminish output amplitude. | Divergent syntax may boost output; Convergent may suppress it. | Fluorescence (e.g., GFP) measured via flow cytometry or plate reader. |

| Response Time | Retroactivity can slow the response kinetics of a module. | Altered initiation rates from supercoiling can speed up or slow down response. | Time-lapse microscopy tracking fluorescence onset after induction. |

| Steady-State Stability | Load can cause drift from the intended steady state. | Supercoiling feedback can create or destroy bistable states. | Long-term culturing with periodic measurement of population output. |

| Resource Burden | High-load downstream modules can starve upstream modules of resources. | Energetically costly supercoiling mitigation consumes cellular ATP. | Growth rate monitoring and ribosome profiling. |

Methodologies for Analyzing Topological Effects

A systematic approach to understanding and mitigating retroactivity involves a combination of in silico modeling and carefully designed in vivo experiments.

Computational Modeling and Prediction

Mathematical frameworks are crucial for predicting circuit-host interactions. Comprehensive models now aim to integrate both resource competition and growth feedback to explore the complexity of interactions among these factors [3]. A basic model for retroactivity can be incorporated by considering the sequestration of a transcription factor (X) by its downstream binding sites (P):

Rate of change of free X: d[X]/dt = Production - Degradation - kₒₙ[X][P] + kₒff*[XP]

Where kₒₙ and kₒff are the binding and unbinding rates, and [P] is the concentration of free downstream binding sites. The key insight is that the term kₒₙ[X][P] represents the retroactive load, which pulls X away from its intended functional pool.

Experimental Workflow for Characterizing Retroactivity

A robust experimental protocol for characterizing the impact of topology and retroactivity involves the following steps:

Construct Design and Synthesis:

- Design genetic modules with identical protein-coding sequences but varying syntactic arrangements (convergent, divergent, tandem).

- Clone these constructs into standardized plasmid backbones or specific genomic loci using assembly methods (e.g., Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly).

- Incorporate inducible promoters (e.g., pTet, pLac) for controlled activation and fluorescent reporters (e.g., GFP, mCherry) for quantitative output measurement.

Cell Transformation and Culturing:

- Transform constructs into the chosen host organism (e.g., E. coli MG1655).

- Culture transformed cells in controlled bioreactors or multi-well plates to maintain consistent environmental conditions.

Data Acquisition and Measurement:

- Induce the circuit using a defined concentration of inducer (e.g., Anhydrotetracycline, IPTG).

- Measure circuit output over time using:

- Flow Cytometry: To obtain single-cell resolution data on fluorescence, revealing cell-to-cell variability and potential bimodality.

- Plate Reader Kinetics: To track population-average fluorescence and growth (OD₆₀₀) over time.

- Monitor host growth rate simultaneously, as it is a sensitive indicator of cellular burden.

Data Analysis:

- Extract key metrics: maximum expression level, response time, and growth rate inhibition.

- Compare these metrics across different syntactic arrangements to quantify the effect of topology.

- Fit mathematical models to the data to estimate parameters related to retroactivity and burden.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

To conduct research in this field, a specific toolkit of biological reagents, computational tools, and experimental systems is required.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Topology and Retroactivity Studies

| Category | Item / Reagent | Specific Function / Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Parts | Orthogonal Promoters (pTet, pBAD, etc.) | To provide isolated, inducible control of different circuit modules. |

| Fluorescent Reporters (GFP, mCherry, etc.) | To serve as quantitative proxies for gene expression output of different modules. | |

| Insulators / Transcriptional Terminators | To minimize unintended cross-talk between adjacent genetic modules. | |

| Host Organisms | Engineered E. coli Strains (e.g., MG1655, BL21) | Standard, well-characterized chassis for initial circuit prototyping. |

| "Resource-Aware" Chassis | Strains engineered with enhanced resource pools (e.g., extra rRNA operons). | |

| Computational Tools | Cello Software [11] | Automated genetic circuit design that can incorporate signal matching. |

| BioTapestry [12] | Specialized software for modeling and visualizing Genetic Regulatory Networks (GRNs). | |

| ODE Simulators (MATLAB, Python) | For building and simulating custom models of circuit dynamics including retroactivity. | |

| Analysis Methods | Flow Cytometry | To measure gene expression distributions at the single-cell level. |

| RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) | To comprehensively profile global gene expression and infer resource competition. |

Advanced Mitigation Strategies: From Load Drivers to Multi-Level Regulation

Overcoming the challenges posed by retroactivity and topological interference requires advanced design strategies that go beyond simple optimization of parts.

Embedded Control Circuits

A powerful engineering solution is the implementation of control-embedded circuit designs that actively buffer against contextual effects. One prominent example is the "load driver" device, which has been developed specifically to mitigate the undesirable impact of retroactivity [3]. This approach functions analogously to a buffer amplifier in electronics, isolating the core circuit function from the variable load presented by downstream components.

Multi-Level Regulatory Design

An emerging paradigm is the design of multi-level regulatory circuits that integrate control at the DNA, RNA, and protein levels [11]. This strategy distributes the regulatory burden across different cellular subsystems, which can reduce the load on any single resource pool (e.g., RNA polymerase or ribosomes) and minimize retroactivity. For instance, combining transcriptional activation with post-transcriptional repression using CRISPR-dCas or microRNAs can create more robust circuits whose function is less dependent on a single level of regulation that might be saturated or interfered with [11].

The role of circuit topology—encompassing intergenic context and syntax—is a fundamental determinant of retroactivity in synthetic gene networks. The physical arrangement of genes dictates the mechanical and biochemical interplay between transcriptional processes, primarily through DNA supercoiling, which can lead to emergent feedback loops and significant deviations from intended circuit behavior. This non-modularity contravenes core engineering principles and has necessitated a shift towards host-aware and resource-aware design paradigms [3].

Moving forward, the field must address several outstanding questions to advance. Can the control strategies identified in simple circuits be successfully extended to complex, multi-module architectures? To what extent can the new redesign principles for circuit-host interactions be generalized across different host organisms and environmental conditions [3]? Answering these questions will require the continued development of sophisticated computational models that integrate resource competition, growth feedback, and topological effects, coupled with high-throughput experimental validation. By systematically understanding and engineering circuit topology to minimize retroactivity, synthetic biology will progress towards its goal of creating truly modular, predictable, and deployable biological systems.

In synthetic biology, the principle of modularity is foundational, allowing researchers to design complex genetic circuits from simpler, characterized parts. However, the practical implementation of this principle is challenged by retroactivity, a phenomenon where a downstream genetic module alters the functional dynamics of an upstream module that regulates it [13]. When an upstream transcription factor (TF) is connected to downstream promoter binding sites, the binding and unbinding interactions between them can significantly slow the upstream module's response time and change its output characteristics [13]. This effect poses a substantial obstacle to predictable circuit design, as the behavior of an isolated module may differ considerably from its behavior when embedded within a larger network. Understanding and quantifying retroactivity is thus essential for advancing synthetic biology toward more reliable and scalable circuit implementations.

Theoretical work has established that retroactivity arises from loading effects at the interface between modules. When an upstream TF regulates a downstream module, it binds to specific promoter sites, effectively reducing the concentration of free TFs available for regulation and altering the kinetics of the upstream system [14]. This phenomenon is analogous to loading effects in electrical circuits, where connecting a load to a source can affect the source's output characteristics. In genetic circuits, this loading effect can manifest as slowed response dynamics, altered oscillation frequencies, or complete disruption of functional behaviors [14] [15]. Recent research has demonstrated that retroactivity impacts fundamental network motifs differently; while increasing retroactivity in a negative autoregulatory circuit consistently slows its response, in an incoherent feedforward loop (IFFL), retroactivity can either accelerate or decelerate the response depending on specific circuit parameters [15].

Theoretical Foundations of Retroactivity

Molecular Mechanisms of Retroactivity

Retroactivity emerges from two primary molecular mechanisms: competitive binding and resource sharing. The competitive binding mechanism occurs when downstream promoter binding sites compete with upstream binding sites for a limited pool of regulatory proteins [14]. This competition effectively increases the total number of binding sites in the system, reducing the number of free regulatory protein molecules and consequently lowering the binding probability to each specific site in the upstream network. The second mechanism involves resource competition for cellular degradation machinery, particularly when synthetic circuits utilize tagged proteins degraded by specific proteases with limited cellular availability [14]. When reporter proteins and regulatory proteins share the same degradation pathway, increases in reporter protein levels can sequester proteases, thereby affecting the degradation kinetics of regulatory proteins and ultimately altering circuit dynamics.

The mathematical modeling of these processes typically employs ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that capture the biochemical reactions involved in gene regulation, protein synthesis, and degradation. For a system where transcription factor X regulates downstream binding sites P, the dynamics can be described by:

Where X_total represents the total transcription factor concentration, α is the production rate, γ is the degradation rate of free TF, and γ_2 represents the effective removal rate when TF is bound to downstream sites [13]. The binding and unbinding processes between X and P are typically assumed to be fast relative to other processes, allowing a quasi-steady state approximation for the bound complex.

Quantifying Retroactivity Through Noise Analysis

A practical method for quantifying retroactivity leverages the stochastic nature of gene expression. Gene circuits exhibit significant stochastic fluctuations due to low copy numbers of transcription factors, and these fluctuations contain valuable information about system dynamics [13]. When an upstream module is connected to a downstream system, the correlation time of stochastic noise in the transcription factor expression increases, reflecting the slowdown in response dynamics caused by retroactivity.

The autocorrelation function G_Xtot(τ) of the total transcription factor concentration can be used to extract this information:

where X_tot(t) is the signal amplitude at time t and the angle brackets denote an average over time at stationary state [13]. The decay characteristics of this autocorrelation function change when the circuit is connected to a downstream module, providing a measurable signature of retroactivity. This approach is particularly valuable because it can be implemented experimentally without requiring precise knowledge of all system parameters, relying instead on measurable noise characteristics.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Quantifying Retroactivity from Stochastic Noise

| Parameter | Symbol | Biological Interpretation | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation time | T | Characteristic timescale of fluctuations | Autocorrelation decay rate |

| Intrinsic noise intensity | W_I | Magnitude of stochastic fluctuations from biochemical reactions | Variance in expression under constant conditions |

| Extrinsic noise intensity | W_E | Magnitude of fluctuations from external cellular factors | Cell-to-cell variation in identical genetic constructs |

| Intrinsic noise correlation time | T_I | Timescale of intrinsic fluctuations | Autocorrelation in isolated components |

| Extrinsic noise correlation time | T_E | Timescale of extrinsic fluctuations | Population-level synchronization analysis |

Experimental Evidence of Retroactivity Effects

Experimental System: Synthetic Genetic Oscillator

Direct experimental evidence for retroactivity comes from studies of synthetic genetic oscillators, where researchers compared circuits with identical regulatory components but different downstream reporter configurations [14]. In these experiments, the Smolen oscillator architecture—incorporating both positive and negative feedback loops—was implemented in E. coli using AraC and LacI regulatory proteins [14]. The experimental design specifically tested how variations in downstream binding sites affect oscillator dynamics, with two strains containing identical regulatory circuits but different reporter genes with varying structures of regulatory protein-binding sites.

The experimental results demonstrated that the copy number of regulatory protein-binding sites in downstream genes significantly altered upstream oscillation dynamics. Circuits with additional binding sites exhibited modified oscillation periods and amplitudes, and in some cases, complete disruption of oscillatory behavior [14]. Furthermore, even when the total number of protein-binding sites was maintained constant, different allocations of those sites between regulatory and reporter genes caused distinct perturbations in circuit dynamics due to competition for degradation resources between target proteins and their tag-specific proteases [14].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Retroactivity on Genetic Oscillator Performance

| Circuit Configuration | Oscillation Period (min) | Oscillation Amplitude (a.u.) | Damping Rate (% decrease per cycle) | Retroactivity Measure (R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated regulator | 45 ± 3 | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 0.00 |

| Low-copy reporter | 48 ± 4 | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 0.18 ± 0.03 |

| High-copy reporter | 62 ± 5 | 0.75 ± 0.08 | 12.3 ± 2.1 | 0.47 ± 0.05 |

| Optimized binding sites | 46 ± 3 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

Experimental Protocols

Mathematical Modeling and Simulation

Computational models were constructed based on biochemical reactions including promoter interactions, protein synthesis, and component decay [14]. The mathematical framework extended established models of genetic oscillators with modifications reflecting recent experimental findings—particularly regarding DNA looping dynamics where one LacI tetramer (rather than two) forms a DNA loop [14]. Key parameters included loop dissociation rates (k_ul), loop formation rates (k_l), and loop unforming rates (k_-l), with binding rates at AraC protein binding sites determined from previous studies [14]. Nonlinear ordinary differential equations were formulated and solved numerically, with stability analysis performed using linear stability analysis and modified Routh's method to determine oscillation stability [14].

Bacterial Strains and Plasmid Construction

The experimental system utilized Escherichia coli strain JS006 (MG1655 ΔaraC ΔlacI KanS) as the host organism [14]. Plasmid pJS167 served as the foundation, modified to create pJSDT267 with an alternative reporter Plac-gfp. Control plasmids pJSDT171 and pJSDT271 were constructed to quantify maximum transcription activities of reporter gfp genes driven by lac/ara and lac promoters, respectively [14]. All constructs were verified through sequencing, and transformation was performed using standard heat-shock methods with appropriate antibiotic selection.

Reporter Assay and Microscopy

Reporter assays involved growing overnight cultures of reporter strains at 37°C in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics, followed by dilution to OD600 of 0.1 in fresh medium [14]. Cultures were incubated with or without inducers (e.g., 0.1% arabinose) for 2 hours at 37°C, after which 1.0 mL of each culture was washed with phosphate-buffered saline via centrifugation. Raw fluorescence intensity was measured using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 515-545 nm [14]. For time-lapse microscopy, images were acquired using an Eclipse Ti-E inverted microscope with an Apochromat 40x objective lens and EMCCD camera, with analysis performed using NIS-Elements Advanced Research software [14].

Visualization of Retroactivity Mechanisms

Retroactivity in a Genetic Regulatory Module

This diagram illustrates how free transcription factors produced by an upstream module become bound to promoter sites in downstream modules, reducing their availability for regulation and creating retroactivity that slows the upstream system's response dynamics [14] [13].

Resource Competition and Degradation Sharing

This visualization shows how both regulatory proteins and reporter proteins compete for a limited pool of degradation machinery (proteases), creating another form of retroactivity where increased reporter levels can alter regulatory protein dynamics by reducing their degradation rate [14].

Experimental Workflow for Retroactivity Measurement

This workflow outlines the experimental process for measuring retroactivity, from initial computational design through molecular cloning, bacterial transformation, culture induction, time-series measurement, and final noise analysis to quantify retroactivity effects [14] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Retroactivity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Reporters (e.g., GFP, RFP) | Quantification of gene expression dynamics | Real-time monitoring of promoter activity | Maturation time, brightness, spectral overlap |

| Degradation Tags (e.g., ssrA) | Targeted protein degradation | Manipulating protein half-life | Protease specificity, efficiency |

| Inducible Promoters (e.g., Pbad, Plac) | Controlled gene expression | Precise timing of circuit activation | Leakiness, dynamic range |

| Low-copy Number Plasmids | Stable maintenance of genetic circuits | Mimicking chromosomal copy numbers | Compatibility, segregation stability |

| Binding Site Arrays | Titration of transcription factors | Quantitative retroactivity studies | Binding affinity, specificity |

| Protease-Deficient Strains | Studying degradation competition | Isolating resource competition effects | Viability, secondary mutations |

Implications for Synthetic Biology and Drug Development

The documented effects of retroactivity have profound implications for synthetic biology design principles and pharmaceutical development. For synthetic biologists, retroactivity represents a fundamental challenge to the modular design paradigm, necessitating strategies to mitigate its effects or exploit it for functional advantages [15]. Implementation of insulating devices—genetic components that minimize retroactivity between connected modules—has emerged as a promising approach for maintaining modularity. Alternatively, understanding how retroactivity affects different network motifs enables designers to anticipate and compensate for these effects during the design process.

In pharmaceutical development, particularly in drug repurposing research, understanding retroactivity-like effects in biological networks is crucial [16]. When existing drugs are applied to new disease contexts, their effects on cellular networks can be unpredictable due to complex interactions within the system—phenomena conceptually similar to retroactivity [16]. The systematic study of how interventions propagate through biological networks, including both intended and unintended consequences, can inform more effective drug development strategies and improve success rates in translational research.

The experimental and theoretical frameworks presented here provide a foundation for quantifying and managing retroactivity in synthetic genetic circuits. By applying noise analysis, carefully designing experimental controls, and utilizing appropriate mathematical models, researchers can both mitigate the disruptive effects of retroactivity and potentially exploit it for novel circuit functions. As synthetic biology progresses toward more complex and clinically relevant applications, understanding these fundamental network interactions will be essential for creating reliable, predictable biological systems.

In synthetic biology, the engineering of predictable gene circuits is fundamentally challenged by context-dependent phenomena, where a circuit's behavior is intricately linked to its host cell environment. Among these, retroactivity represents a critical system-level challenge. Retroactivity occurs when downstream nodes in a genetic network unintentionally interfere with or load the upstream nodes that regulate them, for instance, by sequestering transcription factors or other signaling molecules [3]. This phenomenon contravenes the engineering principle of modularity, making it difficult to predict circuit behavior from individual components alone [3] [17].

This technical guide explores the profound connection between retroactivity and two other major system-level challenges: growth feedback and cellular burden. These interactions are not isolated; they form a complex web of feedback loops that convolute circuit dynamics. When a synthetic circuit places a load on the host via resource consumption (burden), which in turn reduces cellular growth rate (growth feedback), the resulting physiological changes can alter the very kinetics that govern retroactive effects [3]. Understanding these intertwined relationships is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to design robust, predictable, and deployable synthetic gene networks for therapeutic applications, such as in next-generation CAR-T cells or metabolic disease therapies [18].

The Interplay of Core System-Level Challenges

Retroactivity: Signal Sequestration and Unintended Loading

Retroactivity is fundamentally an input-output phenomenon. In electrical engineering, connecting a load to a circuit's output can alter its voltage; similarly, in synthetic biology, connecting a downstream genetic module to an upstream one can alter the upstream module's output dynamics. This happens because the downstream module acts as a load, sequestering the upstream signal—often a transcription factor—thereby reducing its effective concentration and changing the timing or steady-state level of the upstream output [3]. This effect is a significant source of context dependence, as the same upstream module will behave differently depending on what it is connected to, breaking modularity and complicating predictive design.

Synthetic gene circuits operate within a living cell that possesses a finite pool of transcriptional and translational resources. Cellular burden (or metabolic burden) emerges when the circuit's operation diverts essential resources—such as RNA polymerases (RNAP), ribosomes, nucleotides, and energy (ATP)—away from the host's native processes [3] [19] [17]. In bacteria, the primary competition is typically for translational resources (ribosomes), whereas in mammalian cells, competition for transcriptional resources (RNAP) is often more dominant [3]. This burden disrupts cellular homeostasis and is a direct consequence of the circuit's resource consumption, creating a system-wide perturbation.

Growth Feedback: A Multiscale Reciprocal Loop

Growth feedback is a multiscale loop that intimately links circuit function and host physiology. The operation of a synthetic circuit, through the mechanism of cellular burden, reduces the host's growth rate. This slower growth, in turn, alters the circuit's behavior in two key ways:

- It changes the dilution rate of circuit components (mRNAs and proteins), as they are distributed across a growing population of cells.

- It induces broad physiological changes in the cell, including alterations in the abundance of global resources like ribosomes and changes in transcription/translation rates [3]. Thus, the circuit affects the host's growth, and the host's growth feeds back to affect the circuit, creating a dynamic, reciprocal relationship.

Integrating the Challenges: A Convoluted Web of Interactions

These three challenges are not independent but are deeply intertwined. The diagram below illustrates how retroactivity, resource competition, and growth feedback form a complex network of interactions that jointly determine system behavior.

Figure 1: System-Level Interactions. This diagram shows the feedback loops between a synthetic gene circuit, host resources, and growth. The circuit consumes resources, causing burden that slows host growth, which in turn dilutes circuit components and alters system dynamics.

The operation of the circuit consumes free resources, leading to cellular burden and a reduction in host growth rate. The resulting growth feedback then alters the concentration of circuit components via dilution and can upregulate cellular resource pools. Meanwhile, retroactive interactions between circuit modules further perturb the internal state of the circuit, affecting its resource demands [3]. This framework demonstrates that a comprehensive, host-aware and resource-aware modeling approach is necessary to predict the emergent dynamics of synthetic gene circuits.

Quantitative Emergent Dynamics and System Outcomes

The interplay between growth feedback, burden, and retroactivity can lead to several counterintuitive and emergent system behaviors, which are quantifiable through mathematical modeling and experimental observation.

Emergence and Loss of Multistability

Multistability is a key function in many synthetic circuits, enabling toggle switches and cellular memory. However, growth feedback can fundamentally alter the number of stable states a system can occupy.

Table 1: Impact of Growth Feedback on Circuit Multistability

| Circuit Type | Impact of Growth Feedback | Underlying Mechanism | Quantitative Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bistable Self-Activation Switch | Loss of the high-expression ("ON") state | Increased protein dilution rate elevates the degradation curve, eliminating its intersection with the production curve above the low-expression state [3]. | System collapses from bistable to monostable (single low-state) [3]. |

| Noncooperative Self-Activation Circuit | Emergence of bistability | Significant cellular burden reduces the host growth rate and thus the dilution rate, creating two stable states: low-expression/high-growth and high-expression/low-growth [3]. | System transitions from monostable to bistable [3]. |

| Self-Activation Circuit with Ultrasensitive Feedback | Emergence of tristability | Ultrasensitive growth feedback shifts the degradation curve in a non-monotonic manner, creating three possible intersection points with the production curve [3]. | System gains a third, intermediate stable state [3]. |

Evolutionary Instability and Mutant Takeover

The burden imposed by a functional circuit creates a selective pressure for mutant cells that have inactivated the circuit, thereby gaining a fitness advantage. This evolutionary process is a direct consequence of burden and growth feedback, leading to the eventual dominance of non-producing mutants in a population.

Table 2: Evolutionary Longevity Metrics for Synthetic Gene Circuits

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Typical Open-Loop (Uncontrolled) Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| P₀ | Initial total protein output from the ancestral population prior to any mutation [19]. | Measures the circuit's initial performance and production yield. | Higher P₀ often correlates with faster functional decline due to increased burden. |

| τ±₁₀ | Time taken for the total output (P) to fall outside the range P₀ ± 10% [19]. | Indicates the duration of short-term, stable performance near the designed level. | Generally shortens as initial burden increases. |

| τ₅₀ (Half-Life) | Time taken for the total output (P) to fall below P₀/2 [19]. | Measures long-term "persistence," or the maintenance of some function, which may be sufficient for applications like biosensing. | Increases with lower initial burden, but is often unacceptably short for high-performance circuits. |

For a simple, open-loop output circuit, simulations show that the total protein output P falls over time as the population makeup shifts from fully functional cells to faster-growing, non-producing mutants [19]. The higher the initial transcription rate (ωA), the greater the initial output P₀, but this also increases the burden, subsequently reducing both τ±₁₀ and τ₅₀ [19].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating System Challenges

To study these interconnected phenomena, researchers employ a combination of modeling and meticulous experimental workflows. The following protocol outlines a generalized approach for quantifying the effects of burden and growth feedback on circuit performance and evolutionary stability.

Protocol: Quantifying Burden and Evolutionary Longevity

Objective: To measure the impact of synthetic gene circuit expression on host growth rate and to track the loss of circuit function over evolutionary time in a bacterial model.

Materials:

- Strains: Engineered E. coli (e.g., DH5α, BL21) harboring the synthetic gene circuit of interest and an appropriate control strain (e.g., with a non-functional circuit or empty vector) [19] [20].

- Culture Conditions: LB medium supplemented with required antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin at 100 μg/mL). Inducers (e.g., IPTG, arabinose) for tunable circuit expression [20].

- Equipment: Microplate reader or spectrophotometer for high-throughput growth and fluorescence measurement, flow cytometer for population-level analysis, PCR and sequencing equipment for genotyping mutants.

Methodology:

- Strain Cultivation: Inoculate parallel cultures of the engineered and control strains in a 96-deep well plate. Use at least 6 biological replicates per strain.

- Growth and Output Monitoring:

- Transfer cultures to a transparent 96-well microplate at defined intervals (e.g., every 30-60 minutes).

- Measure the optical density (OD600) as a proxy for cell growth and biomass.

- Simultaneously, measure fluorescence (e.g., GFP/RFP) using appropriate excitation/emission filters to quantify circuit output.

- Continue measurements throughout the exponential growth phase.

- Serial Passaging for Evolution:

- Each 24-hour period constitutes one batch. Daily, dilute all cultures into fresh medium to reset the population density, maintaining the same inducer concentration [19].

- Continue this serial passaging for multiple days (e.g., 10-20 days).

- At each passage, archive samples for later analysis (e.g., flow cytometry, sequencing).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate Burden: For each day, compare the growth rate (derived from OD600 curves) and maximum OD of the engineered strain versus the control.

- Track Circuit Performance: Plot the total fluorescence output (population OD600 × mean fluorescence per cell) over time to determine

τ±₁₀andτ₅₀[19]. - Analyze Population Dynamics: Use flow cytometry to monitor the emergence of sub-populations with low or no output. Sequence key time points to identify loss-of-function mutations.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow. This protocol for quantifying burden and evolutionary longevity involves continuous monitoring of growth and output across serial batches to track performance decline and mutant takeover.

Mitigation Strategies: From Theory to Application

To combat the destabilizing effects of retroactivity, burden, and growth feedback, several embedded control strategies have been developed.

Controller Architectures for Enhanced Longevity

Feedback control can be engineered into the circuit itself to maintain performance. The choice of what the controller senses (its input) and how it acts (its actuation mechanism) is critical.

Table 3: Genetic Controller Architectures for Mitigating Evolutionary Failure

| Controller Type | Input Signal | Actuation Mechanism | Key Advantage | Reported Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-Circuit Feedback | Output level of the circuit protein itself (e.g., via negative autoregulation) [19]. | Transcriptional or post-transcriptional regulation of the circuit's expression [19]. | Improves short-term performance stability (τ±₁₀) by maintaining output set-point [19]. |

Prolongs short-term performance but may not optimize long-term half-life [19]. |

| Growth-Based Feedback | Host growth rate [19]. | Couples circuit expression to a growth-related cellular factor. | Extends the functional half-life (τ₅₀) of the circuit by aligning circuit function with host fitness [19]. |

Can improve circuit half-life over threefold without coupling to essential genes [19]. |

| Post-Transcriptional Control | Various (e.g., circuit output, external inducers). | Uses small RNAs (sRNAs) to silence circuit mRNA [19]. | Provides strong, rapid control with lower burden than protein-based controllers; outperforms transcriptional control [19]. | Enhanced performance due to amplification and reduced resource consumption [19]. |

Decoupling and Insulation Strategies

A complementary approach involves engineering circuits to minimize unintended interactions from the outset.

- Decoupling: Refactoring genetic elements to eliminate overlapping sequences and unintended interactions, thereby improving modularity [17].

- Orthogonal Systems: Using components (e.g., polymerases, ribosomes, transcription factors) from distant species or engineering novel ones that do not cross-talk with the host's native systems [17]. This reduces competition for shared resources and mitigates burden.

- Load Drivers: Designing upstream modules to be "robust to load," effectively insulating them from the retroactive effects of downstream connections [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Investigating Retroactivity, Burden, and Growth Feedback

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Promoters (e.g., pLac, pAra, Tet-On) [20] | Allows precise control of gene expression levels using small molecule inducers (IPTG, arabinose, aTc). | Titrating circuit expression to directly correlate resource consumption with growth rate reduction (burden measurement). |

| Fluorescent Reporters (e.g., GFP, mCherry) [19] | Provides a quantifiable, non-disruptive readout of circuit output and dynamics at single-cell and population levels. | Serving as the output P in evolutionary longevity experiments to track τ±₁₀ and τ₅₀ [19]. |

| Orthogonal Ribosomes & RBSs [17] | Creates separate translational machinery for the circuit, insulating it from host competition and reducing burden. | Validating the effect of resource competition by comparing burden in strains with and without orthogonal systems. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 System [21] | Enables construction of complex logic gates and synthetic regulation without altering the DNA sequence (for reversible circuits). | Implementing transcriptional controllers for negative feedback or building integrator modules that process multiple inputs. |

| Serine Integrases (e.g., PhiC31, Bxb1) [21] | Enables irreversible genetic recombination, used for building memory circuits and recording historical events. | Studying long-term stability and memory propagation in toggle switches despite growth-mediated dilution. |

| Host-Aware Modeling Frameworks [3] [19] | Mathematical models that integrate circuit kinetics, resource competition, and growth dynamics. | Predicting emergent phenomena like loss of bistability or evolutionary trajectories in silico before costly experimental implementation. |

The challenges of retroactivity, cellular burden, and growth feedback are inextricably linked, forming a complex web of interactions that define the performance and evolutionary stability of synthetic gene circuits. Addressing one challenge in isolation is insufficient; a holistic, host-aware design philosophy is required. By leveraging quantitative modeling, robust experimental protocols, and innovative mitigation strategies like embedded feedback controllers and orthogonal systems, researchers can advance the development of reliable biological systems. As synthetic biology progresses toward sophisticated clinical applications, such as smart living therapeutics [18], mastering these system-level challenges will be the cornerstone of translating engineered gene networks from the laboratory into safe and effective real-world technologies.

Engineering Solutions: Methodologies to Counteract and Leverage Retroactivity

Core Design Principles for Insulating Genetic Modules from Retroactivity

In synthetic biology, the predictable interconnection of genetic modules is fundamental to constructing complex, reliable circuits. Retroactivity poses a significant challenge to this paradigm. It is a phenomenon where downstream components in a genetic network adversely affect the behavior of upstream components upon interconnection, effectively breaking the modularity assumption that allows engineers to design systems from well-characterized parts [22] [3]. In transcriptional networks, retroactivity becomes significant when the concentration of a transcription factor is comparable to or lower than the concentration of its target promoter binding sites, or when the binding affinity of these sites is high [22]. This effect is analogous to the loading problem in electrical engineering, where connecting a load to a circuit can alter the circuit's output voltage [22]. Understanding and mitigating retroactivity is therefore critical for the advancement of robust synthetic gene network design, particularly for therapeutic applications where predictability is paramount [23].

Quantifying and Measuring Retroactivity

Theoretical Foundations and Quantitative Impact

Retroactivity can be formally quantified by analyzing the dynamic changes in a system before and after interconnection. In a module's isolated state, the dynamics of its output transcription factor (e.g., protein x) can be described by dx/dt = f(x, t). When the module is connected to a downstream system that sequesters x, the dynamics change to dx/dt = f(x, t) - R(x, t), where R(x, t) represents the retroactivity term [22]. The magnitude of this retroactivity, denoted as ℛ, measures the sensitivity difference between the quasi-steady-state dynamics of the interconnected system and the intended dynamics of the isolated system [22].

Table 1: Conditions Leading to Significant Retroactivity

| Factor | Condition for High Retroactivity | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor Concentration | [TF] ≤ [Binding Sites] |

Low abundance transcription factors are more susceptible to sequestration by downstream targets. |

| Binding Affinity | High affinity (K_d low) |

Strong binding between TF and promoter sites leads to stable complexes, effectively draining the free TF pool. |

| System Dynamics | Slow transcription factor production rate | Systems cannot rapidly replenish the free TF pool depleted by downstream binding. |

Experimental Measurement Techniques

Experimentally, retroactivity can be measured by observing its effect on the correlation time of stochastic noise in gene expression. When an upstream module is connected to a downstream load, the increased sequestration of the transcription factor reduces its effective degradation rate, leading to longer correlation times in the output signal's fluctuations [8]. The following protocol outlines this measurement approach:

Protocol 1: Measuring Retroactivity from Expression Noise

- Strain Construction: Create two bacterial strains:

- Strain A (Unloaded): Contains the upstream genetic module (e.g., a promoter driving a fluorescent reporter protein) in isolation.

- Strain B (Loaded): Contains the identical upstream module connected to a downstream module with high-affinity binding sites for the output transcription factor.

- Time-Lapse Microscopy: Grow both strains in a microfluidic device under a constant environment and perform time-lapse microscopy to capture single-cell fluorescence over multiple generations.

- Noise Analysis: For each cell trajectory, calculate the autocorrelation function of the fluorescence signal. The decay rate of this autocorrelation function provides the correlation time (

τ). - Retroactivity Quantification: Compute retroactivity as the normalized change in correlation time:

ℛ = (τ_loaded - τ_unloaded) / τ_unloaded. A positive value indicates the presence of significant retroactivity from the downstream system [8].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for measuring retroactivity from gene expression noise.

Core Insulation Principles and Mechanisms

To achieve modularity, synthetic biologists have developed insulation strategies that attenuate retroactivity. These principles are inspired by engineering solutions to analogous loading problems in electronics.

Feedback-Based Attenuation

A primary insulation strategy employs strong negative feedback inspired by the design of non-inverting amplifiers in electronics. This mechanism uses a large input gain and similarly large negative feedback to maintain a consistent output despite variations in the load [22]. A biological implementation of this principle is the phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle (PDC).

Mechanism: An upstream module produces a transcription factor X. Instead of directly regulating the downstream system, X is fed into a fast PDC. The active, phosphorylated form X_p serves as the insulated output that drives the downstream modules. The key is the timescale separation; the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation reactions are much faster than the production rate of X. This rapid cycle buffers the upstream module from the sequestration of X_p by the downstream system, as any X_p that is bound is rapidly replaced from the pool of X [22].

Diagram 2: Insulation via a phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle (PDC).

Load Drivers and Abundant Signaling

Another effective principle is the use of a "load driver" device. This approach involves placing a buffer component between a sensitive upstream module and a high-load downstream module [3]. The load driver is designed to be highly abundant and resilient to sequestration.

Biological Implementation: A common load driver employs a strong, non-leaky promoter to express an output protein at very high levels, combined with an abundant protease that degrades the protein product. This creates a high-gain negative feedback loop [22]. The large pool of output protein means that binding by downstream systems drains only a small fractional amount, leaving the free concentration largely unchanged and thus insulating the upstream module.

Transcriptional Insulation through Functional Modularity

Retroactivity can also occur at the transcriptional level due to unwanted interactions between genetic parts. A key design principle to prevent this is functional insulation of promoter elements. In prokaryotes, canonical σ70-dependent promoters are often context-sensitive, meaning that inserting different operator sequences into their spacer region can alter their intrinsic activity by over 80-fold [24].

Solution: Utilize promoter cores with high context-independence. Research has identified that promoter cores recognized by bacterial extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors and T7-family RNA polymerases exhibit superior functional modularity [24]. For example, saturation mutagenesis of the P_ECF11 promoter core revealed that sequences outside the essential -35 and -10 boxes were largely insensitive to variation, allowing operators to be inserted without perturbing the core's intrinsic activity. This enables the precise, bottom-up design of combinatorial promoters with predictable functions [24].

Table 2: Performance of Insulated Genetic Devices

| Insulation Mechanism | Experimental System | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Insulation [24] | E. coli with insulated σECF11 and T7 promoter cores | Design success rate for NOT-gate promoters | 96% (80 out of 83 designs functional) |

| Transcriptional Insulation [24] | E. coli with insulated σECF11 and T7 promoter cores | Mean error between predicted and measured activity | <1.5-fold |

| Phosphorylation-Based Insulation [22] | Theoretical analysis of PDC | Attenuation of retroactivity | High attenuation, dependent on fast kinase/phosphatase rates vs. slow upstream production. |

| Tunable Expression System [25] | E. coli TES with toehold switch | Tunable range of output (YFP) | 28-fold shift at low input; 4.5-fold shift at high input |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating and Implementing Insulation

| Reagent / Method | Function in Insulation Research | Key Features and Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ECF σ Factor Promoter Cores [24] | Context-independent promoter cores for precise transcriptional part design. | Minimal length (~19 bp); highly specific for their cognate ECF σ factor (e.g., σECF11, σECF16, σECF20). |

| T7 RNAP Promoter Cores [24] | Orthogonal, context-independent promoters for high-level, insulated expression. | Minimal length (~21 bp); requires constitutive expression of T7 RNAP in the host chassis. |

| Phosphorylation-Dephosphorylation Cycles (PDCs) [22] | Post-translational insulation mechanism buffering upstream modules. | Requires co-expression of a specific kinase and phosphatase. Fast reaction kinetics are critical for effective insulation. |

| Toehold Switches (THS) [25] | Regulates translation initiation; enables construction of tunable, insulated systems. | A 92 bp DNA sequence encoding an sRNA-responsive RBS; translation can be tuned over a 100-400 fold range. |