Programming Cells to Cure: The Frontier of Synthetic Genetic Circuits in Therapeutics

Synthetic genetic circuits represent a paradigm shift in therapeutic development, enabling the programming of living cells to diagnose diseases, compute complex biological signals, and deliver precision treatments.

Programming Cells to Cure: The Frontier of Synthetic Genetic Circuits in Therapeutics

Abstract

Synthetic genetic circuits represent a paradigm shift in therapeutic development, enabling the programming of living cells to diagnose diseases, compute complex biological signals, and deliver precision treatments. This article explores the foundational principles of these engineered systems, from simple switches to complex logic gates. It delves into cutting-edge methodologies and their applications in targeting cancers, managing metabolic diseases, and enabling dynamic drug delivery. Furthermore, it addresses the critical challenges of circuit stability, evolutionary longevity, and clinical translation, while evaluating validation frameworks and comparative analyses of emerging technologies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes the current state of the art and outlines the trajectory toward clinical adoption.

The Building Blocks of Cellular Computation: From Switches to Logic Gates

Synthetic genetic circuits represent a frontier in therapeutic biotechnology, enabling the reprogramming of cellular behavior for precise medical interventions. These circuits are constructed from core molecular components that sense, process, and respond to disease signals within living cells. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the interplay of promoters, transcription factors, and output genes is fundamental to designing effective therapeutic systems. These components form the foundational framework that allows synthetic circuits to perform logical operations, from simple switches to complex diagnostic computations, within cellular environments. Their precise engineering facilitates applications in targeted cancer therapies, dynamic metabolic control, and intelligent biosensing [1] [2]. This technical guide examines the structure, function, and quantitative characterization of these core elements, focusing specifically on their integration within therapeutic frameworks for biomedical innovation.

Core Component Deep Dive

Promoters: The Initiation Gateways

Promoters are DNA sequences that initiate the transcription of a gene by providing a binding site for RNA polymerase and transcription factors. In synthetic genetic circuits, promoters serve as the primary signal processors that convert biological or environmental cues into transcriptional activity.

- Constitutive Promoters: Provide steady, unregulated baseline expression useful for expressing circuit components that require constant levels. However, their lack of regulation limits their utility as sensory components in therapeutic circuits.

- Inducible Promoters: Engineered to respond to specific molecular inducers (e.g., small molecules, light, temperature). These are crucial for creating controlled therapeutic systems where timing and dosage of therapeutic output must be precisely managed [3].

- Logic-Integrated Promoters: Synthetic promoters designed with binding sites for multiple transcription factors can perform Boolean operations. For instance, a promoter might require both the absence of a repressor AND the presence of an activator to initiate transcription, enabling sophisticated signal processing within diseased cells [4] [2].

Quantitative characterization of promoter performance is essential for predictable circuit design. Key parameters include:

- Leakiness: Baseline expression in the OFF state

- Dynamic Range: Ratio between ON and OFF states

- ED50/EC50: Inducer concentration for half-maximal activation

- Orthogonality: Specificity to intended transcription factors without cross-talk

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Common Inducible Promoter Systems

| Regulatory System | Inducer | Dynamic Range (Fold) | Leakiness (%) | ED50 | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TetR/Ptet | aTc | 50-100 | 0.5-2% | 10-100 ng/mL | Eukaryotic gene switches |

| LacI/Plac | IPTG | 20-50 | 1-5% | 10-100 µM | Bacterial circuits, metabolic engineering |

| AraC/PBAD | L-ara | 100-500 | 0.1-1% | 0.01-0.1% w/v | Tightly-regulated expression |

| NahR/Psal | Salicylate | 10-20 | 2-5% | 10-50 µM | Cascade amplification circuits |

Transcription Factors: The Signal Processors

Transcription factors (TFs) are proteins that recognize specific DNA sequences and regulate transcriptional activity. In synthetic biology, both natural and engineered TFs serve as computational elements that process biological information and transmit signals through genetic circuits.

- Natural Transcription Factors: Harnessed from bacterial, viral, or eukaryotic systems (e.g., TetR, LacI, AraC). These provide well-characterized DNA-binding specificity and regulation mechanisms but may lack orthogonality in non-native contexts [3].

- Engineered Synthetic TFs: Created by modifying DNA-binding domains or effector domains to achieve novel functions. The Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) platform demonstrates how synthetic repressors and anti-repressors with Alternate DNA Recognition (ADR) domains enable complex logic operations with minimal parts [4].

- Chimeric Sensors: Fusion proteins that combine sensing domains with transcriptional effector domains. For example, RBDCRD-NarX fusions developed for RAS-sensing circuits combine a RAS-binding domain with bacterial signaling components to create novel oncogene sensors [5].

Recent advances in TF engineering have expanded the toolbox available for therapeutic circuits:

- Anti-Repressors: Engineered TFs that activate transcription in the presence of a ligand rather than repress it, enabling NOT/NOR operations without cascade delays [4]

- Programmable DNA-Binding Domains: CRISPR/dCas9 systems fused to transcriptional effector domains enable sequence-specific targeting without DNA cleavage [2]

- Split-TF Systems: Designs where TF assembly is conditional on specific molecular interactions, increasing circuit specificity and reducing leakiness [1]

Table 2: Classification of Synthetic Transcription Factor Architectures

| TF Type | DNA-Binding Domain | Effector Domain | Regulatory Mechanism | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repressors | Zinc Finger, TetR, LacI | Repression domain | Blocks RNA polymerase binding | Titratable control, noise reduction |

| Activators | VP64, p65 AD | Activation domain | Recruits transcriptional machinery | Signal amplification, weak promoter enhancement |

| Anti-Repressors | Engineered ADR domains | Derepression domain | Displaces native repressors | Logic compression, NOT/NOR gates |

| CRISPR/dCas9 | gRNA-programmed | VP64, KRAB, SRDX | Targeted genomic regulation | Epigenetic editing, multiplexed logic |

Output Genes: The Therapeutic Effectors

Output genes represent the terminal component of genetic circuits where processed information is converted into biological action. In therapeutic applications, these genes encode proteins that execute diagnostic, therapeutic, or regulatory functions.

- Reporter Proteins: Fluorescent (e.g., CFP, YFP, RFP) [3] or luminescent proteins that enable circuit characterization, optimization, and monitoring in real-time.

- Therapeutic Proteins: Cytokines, antibodies, toxins, or corrective enzymes that directly treat disease states when expressed in specific cellular contexts [5] [1].

- Regulatory Effectors: Recombinases, nucleases, or apoptosis-inducers that alter cellular fate or function in response to circuit logic [2].

Selection of appropriate output genes depends on multiple factors:

- Therapeutic Window: Balance between efficacy and toxicity

- Pharmacokinetics: Duration and localization of effect

- Immunogenicity: Potential for immune recognition and clearance

- Manufacturability: Ease of delivery and stability in target cells

Computational Design and Workflow Integration

Modern genetic circuit design employs computational tools to navigate the complex design space and predict circuit behavior before experimental implementation. The shift from intuitive design to algorithmic approaches has become essential as circuit complexity increases.

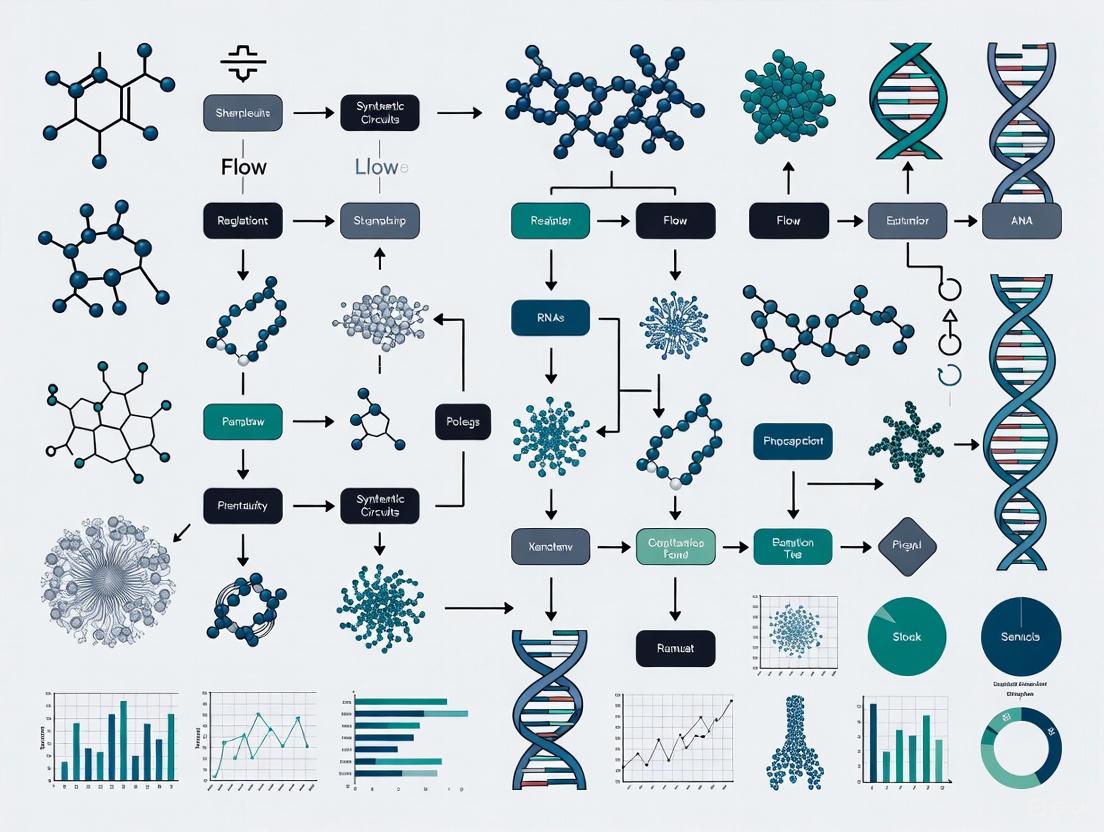

Figure 1: Computational Design Workflow for Therapeutic Circuits

Algorithmic Enumeration and Circuit Compression

For complex circuits, computational methods systematically explore possible component arrangements to identify optimal configurations. The T-Pro algorithmic enumeration approach models circuits as directed acyclic graphs and systematically enumerates designs in order of increasing complexity, guaranteeing identification of the most compressed (minimal-part) circuit for a given truth table [4].

Circuit compression reduces metabolic burden on host cells - a critical consideration for therapeutic efficacy. T-Pro compression circuits are approximately 4-times smaller than canonical inverter-based genetic circuits while maintaining equivalent function [4]. This reduction is particularly valuable for viral delivery systems with limited cargo capacity.

Host-Aware Modeling and Evolutionary Longevity

Therapeutic circuits must function reliably in complex cellular environments. "Host-aware" computational frameworks model interactions between circuit components and host cellular resources, predicting how resource competition affects circuit function and evolutionary stability [6].

Models that simulate mutation and selection dynamics reveal that circuits imposing significant metabolic burden are rapidly selected against in proliferating cell populations. Quantitative metrics for evolutionary longevity include:

- τ±10: Time until population-level output deviates by ±10% from initial designed function

- τ50: Time until population-level output falls to 50% of initial function [6]

Table 3: Controller Architectures for Enhancing Evolutionary Longevity

| Controller Type | Sensed Input | Actuation Method | Short-Term Performance (τ±10) | Long-Term Performance (τ50) | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Autoregulation | Circuit output protein | Transcriptional repression | High improvement | Moderate improvement | Low |

| Growth-Based Feedback | Host growth rate | sRNA-mediated silencing | Moderate improvement | High improvement | Medium |

| Dual-Input Controller | Circuit output + Growth rate | Combined transcriptional & post-transcriptional | Highest improvement | Highest improvement | High |

| Open-Loop Control | None | Constitutive expression | Baseline | Baseline | Lowest |

Experimental Protocols for Component Characterization

Protocol: Quantitative Characterization of Synthetic Promoters

Purpose: To measure key performance parameters of engineered promoters for predictable circuit design.

Materials:

- Reporter plasmid with promoter controlling fluorescent protein

- Inducer molecules at appropriate concentrations

- Host cells (bacterial, yeast, or mammalian)

- Flow cytometer or microplate reader

- Data analysis software

Methodology:

- Transform reporter plasmid into appropriate host cells

- Culture cells across a range of inducer concentrations

- Measure fluorescence intensity and cell density at mid-log phase

- Normalize fluorescence to cell density and autofluorescence controls

- Calculate parameters:

- Leakiness = (Mean fluorescence without inducer) / (Mean fluorescence at saturation)

- Dynamic range = (Fluorescence at saturation) / (Fluorescence without inducer)

- EC50 from dose-response curve fitting (Hill equation)

Troubleshooting:

- High leakiness: Incorporate additional transcriptional terminators; optimize RBS strength

- Low dynamic range: Screen promoter variants with mutated operator sites

- High variability: Use lower-copy number vectors; incorporate genomic integration

Protocol: RAS-Sensing Circuit Implementation for Cancer Targeting

Purpose: To implement a synthetic circuit that selectively targets cells with oncogenic RAS mutations [5].

Materials:

- Plasmids encoding RBDCRD-NarX fusion proteins

- Humanized NarL response regulator

- NarL-responsive promoter driving output gene

- Cancer cell lines with mutant vs. wild-type RAS

- RAS pulldown ELISA assay kit

Methodology:

- Circuit Delivery: Transfect all sensor components into target cells using appropriate methods (lipofection, electroporation, viral delivery)

- RAS Activation Manipulation:

- Express KRASG12D or other mutants to emulate mutant RAS

- Express wild-type KRAS as control

- Co-express Sos-1 to activate endogenous RAS

- Output Measurement: Quantify output protein (e.g., mCerulean) via fluorescence

- Specificity Validation:

- Test RBDCRD mutants (R89L, C168S) that impair RAS binding

- Correlate output with RAS-GTP levels via pulldown assays

- Therapeutic Efficacy: Link circuit to therapeutic output (e.g., cytotoxic protein) and measure cancer cell killing

Key Design Considerations:

- Use AND-gate architecture combining multiple RAS sensors to enhance specificity

- Balance sensor component ratios to optimize dynamic range

- Implement modular design to adapt circuit to different cancer cell contexts

Figure 2: RAS-Sensing Circuit Mechanism for Cancer Targeting

Advanced Therapeutic Applications

Case Study: Compressed Circuits for Higher-State Decision Making

The Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) platform enables 3-input Boolean logic with significantly reduced genetic footprint. This compression technology has been applied to therapeutic contexts where circuit complexity must be balanced with delivery constraints.

Implementation:

- Wetware Expansion: Development of orthogonal synthetic TF sets responsive to IPTG, D-ribose, and cellobiose

- Software Integration: Algorithmic enumeration identifies minimal circuit designs from >100 trillion possibilities

- Quantitative Prediction: Models with <1.4-fold error for >50 test cases enable predictive design [4]

Therapeutic Relevance: Compressed circuits are particularly valuable for viral vector-based gene therapies where packaging capacity is limited, enabling more sophisticated control systems within size-constrained delivery vehicles.

Case Study: Evolutionary-Stable Controllers for Long-Term Function

Synthetic circuits often degrade due to mutation and selection in proliferating cell populations. Genetic controllers that maintain synthetic gene expression over time represent a solution to this fundamental challenge.

Design Paradigms:

- Negative Autoregulation: Extends short-term performance by reducing burden

- Growth-Based Feedback: Monitors host growth rate and adjusts circuit activity accordingly

- Post-Transcriptional Control: Uses sRNA-mediated silencing for rapid response with reduced controller burden [6]

Performance Metrics: Optimized controller designs can improve circuit half-life over threefold without coupling to essential genes, significantly extending therapeutic duration in proliferating cell populations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Circuit Construction

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal RNA Polymerases | Transcriptional isolation | T7-based expression systems | Reduces host-circuit interference |

| Synthetic Transcription Factors | Programmable regulation | T-Pro anti-repressors [4] | Ligand-responsive, engineered DNA specificity |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins | Circuit readout | Cerulean CFP, Venus YFP, Cherry RFP [3] | Spectral separation, fast maturation |

| Site-Specific Recombinases | DNA rewriting | Cre, Flp, Bxb1 integrases [2] | State memory, irreversible switching |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Systems | Programmable targeting | Epigenetic editors, activators/repressors [2] | gRNA-programmable, catalytic activity |

| Three-Color Reporter Scaffold | Multi-parameter monitoring | Simultaneous monitoring of 3 promoters [3] | Genetic stability, minimal crosstalk |

| Host-Aware Modeling Software | Circuit performance prediction | Evolutionary longevity optimization [6] | Multi-scale simulation, burden prediction |

Synthetic biology represents a paradigm shift in biotechnology, enabling the reprogramming of cellular behavior through the design of genetic circuits that process information using Boolean logic principles. Inspired by digital computing, these biological circuits utilize molecular components—DNA, RNA, proteins, and small molecules—to perform logical operations, allowing cells to make sophisticated decisions in response to their environment [1] [7]. The core building blocks of these systems are the fundamental AND, OR, and NOT logic gates, which form the computational basis for complex cellular behaviors engineered for therapeutic applications, diagnostic tools, and personalized medicine [8].

Unlike their electronic counterparts, biological logic gates operate through biomolecular interactions, including transcriptional regulation, protein-DNA binding, and strand displacement reactions [7]. A significant limitation of numerous current genetic engineering therapy approaches is their limited control over the strength, timing, or cellular context of the therapeutic effect [1] [9]. Synthetic gene circuits address this challenge by providing precise control over gene expression and cellular behavior, enabling therapeutic interventions that activate only under specific biological conditions, thereby enhancing safety and efficacy [1] [8]. The application of Boolean logic in biology has expanded beyond basic gates to include combinational circuits and sequential logic with memory functions, opening new frontiers in programmable therapeutics [7].

Core Principles of Biological Logic Gates

Boolean Algebra in Biological Context

Boolean algebra, first introduced by George Boole in 1854, provides the mathematical foundation for biological logic gates, guiding binary calculations that define the output of any logic system [7]. In biological implementations, the binary states (0 and 1) correspond to measurable molecular events:

- State 0 (OFF): Absence of a molecular signal, low gene expression, or inactive protein

- State 1 (ON): Presence of a molecular signal, high gene expression, or active protein

These states are determined by threshold concentrations that must be carefully calibrated in biological systems to ensure reliable logic operations [7]. Biological logic gates can be classified into two broad categories: Boolean logic gates with digital (discrete) processing and non-Boolean logic with analog processing capabilities that better mimic natural biological systems like neural networks [7].

Fundamental Gate Types and Their Truth Tables

The three basic logic gates—AND, OR, and NOT—form the essential building blocks for more complex genetic circuits, each with distinct operational principles and biological implementations.

Table 1: Fundamental Biological Logic Gates and Truth Tables

| Gate Type | Biological Function | Input States | Output State | Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AND | Requires simultaneous presence of all input signals | 00, 01, 10 | 0 | Dual-antigen targeting in CAR-T cells to improve tumor specificity [8] |

| 11 | 1 | |||

| OR | Activates if any input signal is present | 00 | 0 | Targeting heterogeneous tumors with multiple antigen expression patterns [8] |

| 01, 10, 11 | 1 | |||

| NOT | Inverts the input signal (output is active when input is absent) | 0 | 1 | Preventing activation when healthy tissue markers are detected [8] |

| 1 | 0 |

Advanced genetic circuits combine these basic gates to create more sophisticated operations, including NAND, NOR, XOR, and XNOR gates, each serving specific functions in biological computing [1]. The NOR gate, for instance, is particularly significant as any logic function can be achieved by assembling NOR gates only, making it a universal gate for biological computation [10].

Implementation Platforms for Biological Logic Gates

DNA-Based Logic Systems

DNA-based logic gates primarily utilize programmable hybridization schemes of oligonucleotides, leveraging Watson-Crick base pairing to perform computations [7]. The predictable thermodynamics and kinetics of DNA interactions make them ideal for constructing complex logic circuits through several mechanisms:

DNA Strand Displacement: This technology enables the construction of sophisticated logic gates by using input DNA strands to displace pre-hybridized strands, resulting in conformational changes that can be measured as output signals [11]. For example, a three-input AND gate based on strand displacement utilizes a reporter complex where a fluorescently-labeled strand (e.g., FAM-labeled) is hybridized to a quencher-labeled strand (e.g., BHQ1), suppressing fluorescence until all three input strands simultaneously displace the reporter, generating a measurable fluorescent signal [11].

DNA Four-Way Junction (4J) Gates: These systems employ branched DNA nanostructures where oligonucleotide fragments are brought into proximity to form output sequences [12]. In 4J NOT gates, strands are stabilized by a DNA "bridge" that enables fluorescence signal in the absence of input, while addition of an oligonucleotide input decomposes the 4J structure, displacing components and turning off fluorescence [12]. Connected YES and NOT gates can implement functionally complete operations like IMPLY and NAND, providing a path toward arbitrary complexity in DNA circuits [12].

Table 2: DNA-Based Logic Gate Implementation Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Readout | Advantages | Complexity Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Strand Displacement | Input strands displace fluorescently-quenched reporter strands | Fluorescence intensity | High modularity, predictable kinetics | Basic to complex cascades [11] |

| 4-Way Junction (4J) | Branch migration and complex formation | FRET or molecular beacon fluorescence | Compatible with biological environments | Intermediate [12] |

| Transcriptional Programming | Synthetic transcription factors and promoters | Gene expression reporters | Lower metabolic burden, compression capability | Advanced multi-input gates [4] |

Genetic Circuit Platforms in Living Cells

In living cells, logic gates are implemented using synthetic gene circuits that carefully select promoters, repressors, and other genetic components to perform logical operations at the molecular level [1]. The synthetic gene circuit's structure typically involves:

- A sensor layer that detects input signals (e.g., metabolites, pathogens, light)

- A "processor" layer that manages signals through regulatory elements

- An output layer with regulated genes that influence cell functionalities [1]

Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro): This approach leverages synthetic transcription factors (TFs) and synthetic promoters for circuit engineering, utilizing engineered repressor and anti-repressor TFs that support coordinated binding to cognate synthetic promoters [4]. T-Pro enables circuit compression, reducing the number of promoters and regulators needed compared to inversion-based circuits, which minimizes metabolic burden and increases reliability [4]. Recent advances have expanded T-Pro from 2-input to 3-input Boolean logic, permitting an expansion from 16 to 256 distinct truth tables for sophisticated cellular decision-making [4].

CRISPR-Based Logic Gates: CRISPR systems offer another platform for implementing biological logic, with split Cas9 systems enabling the construction of AND gates through intein-mediated reconstitution [1]. This approach distributes the coding sequence of Cas9 across multiple vectors that reconstitute post-translationally, providing higher-level control for diagnostic and therapeutic applications [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

DNA Strand Displacement Logic Gate Assembly

The construction of DNA-based logic gates via strand displacement technology follows a standardized experimental workflow with precise biochemical requirements:

Materials and Reagents:

- Oligonucleotides: Custom-designed DNA strands with specific complementarity regions (typically 2μM working concentration) [11]

- Buffer System: 0.5 × TBE buffer with 50 mM NaCl for optimal hybridization conditions [11]

- Fluorescent Reporters: FAM-labeled strands (excitation: 495 nm, emission: 520 nm) with BHQ1 quencher [11]

- Equipment: Thermal cycler for annealing, fluorescence spectrophotometer for detection [11]

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Annealing Process: Hybridize DNA strands in the initial state configuration in appropriate buffer. Use equimolar ratios of complementary strands (typically 2μM each) with an annealing procedure from 95°C to 22°C over 8 hours to ensure proper complex formation [12] [11].

Strand Displacement Reaction: Divide the annealed product into equal samples and add corresponding input strands at a 1:1 concentration ratio (input:DNA). Incubate at room temperature for sufficient time to allow complete displacement (typically 20 minutes to several hours depending on complexity) [11].

Fluorescence Measurement: Extract samples with known DNA molar mass (e.g., 20 pmol) and dilute with buffer to standard volume (200 μl). Detect fluorescence signals at appropriate wavelengths (e.g., 495 nm excitation/520 nm emission for FAM) using a fluorescence spectrophotometer [11].

Data Analysis: Normalize fluorescence response by subtracting the average fluorescence of reporter-only solutions. Calculate average fluorescence difference (ΔF) from multiple independent samples (typically n=3) with standard deviation error analysis [12].

Genetic Circuit Implementation in Cellular Systems

For implementing logic gates in living cells, such as bacteria or yeast, a different methodological approach is required:

Molecular Cloning and Circuit Assembly:

- Part Selection: Choose promoters, repressors, and output genes compatible with the host chassis. Common regulatory elements include inducible systems (LacI/IPTG, TetR/aTc, Ara/arabinose) and corresponding promoter architectures [10].

Vector Design: Assemble genetic components in plasmid vectors with appropriate resistance markers, origins of replication, and regulatory elements. For complex circuits, distribute parts across multiple vectors to balance metabolic load [4].

Transformation: Introduce constructed plasmids into host cells via transformation or electroporation, selecting with appropriate antibiotics [10].

Characterization and Validation:

- Flow Cytometry: Analyze population-level distributions of circuit outputs using fluorescent protein reporters. Collect data from multiple independent cultures (biological replicates) to assess circuit reliability and cell-to-cell variation [4].

Fluorescence Assays: Perform bulk fluorescence measurements to characterize input-output relationships. Measure response to different input combinations to verify truth table behavior [12].

Mathematical Modeling: Develop quantitative models to predict circuit performance and identify optimal setpoints. Use parameters such as promoter strength, ribosome binding site efficiency, and protein degradation rates to refine circuit function [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Biological Logic Gate Implementation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Logic Gates | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotides | DNA strands with specific complementarity domains [12] [11] | Input recognition, gate operation, signal transmission | HPLC purification, concentration verification via UV-Vis (A260) [12] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | FAM, TAMRA, molecular beacons (MB) with quenchers (BHQ) [12] [11] | Output signal generation | Quencher-fluorophore pair selection, spectral compatibility [11] |

| Synthetic Transcription Factors | Engineered CelR, LacI, TetR variants with ADR domains [4] | Regulatory element execution in cellular circuits | Orthogonality verification, dynamic range characterization [4] |

| Inducer Molecules | IPTG, aTc, arabinose, cellobiose [10] [4] | Chemical inputs for genetic circuit control | Concentration optimization, timing considerations [10] |

| Buffer Components | Tris-HCl, MgCl₂, NaCl, Triton X-100 [12] | Maintain optimal reaction conditions | Mg²⁺ concentration critical for DNA gate kinetics [12] |

Advanced Applications in Therapeutic Interventions

Logic-Gated Cell Therapies

The application of biological logic gates has revolutionized cell-based therapies, particularly in oncology, where precision targeting is critical for success:

AND-Gated CAR-T Cells: These therapies require the simultaneous presence of two tumor-associated antigens before activating cytotoxic responses, dramatically improving specificity [8]. For example, CAR-T cells engineered to recognize both CD19 and CD20 antigens in B-cell malignancies demonstrate improved tumor targeting while minimizing off-target effects on healthy tissues [8]. This approach effectively addresses antigen escape, where tumor cells downregulate single antigens to evade immune detection [8].

NOT-Gated Safety Switches: NOT gates prevent activation when specific inhibitory signals associated with healthy tissues are detected [8]. For instance, certain CAR-T cell designs incorporate inhibitory receptors that block activation if a healthy-cell marker is present, preventing toxicity against critical tissues [8]. This approach is particularly valuable in solid tumors, where potential damage to normal cells expressing low levels of tumor-associated antigens remains a concern [8].

Combinatorial Gating with SynNotch: Synthetic Notch (SynNotch) receptors enable layered logic control, creating multi-step authentication processes for therapeutic cells [8]. In this system, cells recognize an initial antigen which then activates expression of a second receptor that responds to a different antigen, ensuring highly specific activation only in target tissues [8].

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Gene Circuits

Beyond cell therapies, biological logic gates enable sophisticated diagnostic systems and controlled therapeutic delivery:

Biosensing Circuits: Genetic circuits can be designed as highly sensitive biosensors that monitor various biomarkers or pathogens and appropriately synthesize therapeutic molecules in response [1]. These systems typically employ AND-like logic to ensure activation only when specific disease signatures are present, minimizing false positives [1].

Metabolic Disease Management: For disorders like diabetes or metabolic syndromes, logic-gated circuits can sense metabolite levels and respond with precise therapeutic outputs [1]. For example, circuits can be designed to detect abnormal glucose levels and respond with insulin or glucagon production as needed, creating autonomous closed-loop systems for disease management [1].

Precision Gene Editing: CRISPR-based systems integrated with logic gates improve safety by ensuring genome editing occurs only in specific cellular contexts [8]. This strategy allows CRISPR to remain inactive unless certain conditions are met, reducing the risk of unintended genome edits in non-target tissues [8].

Visualization of Genetic Circuit Architecture

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, biological logic gates face several challenges that must be addressed for clinical translation:

Technical and Engineering Complexity: Designing reliable multi-input biological circuits remains challenging due to signal interference, insufficient activation thresholds, and cellular exhaustion [8]. Each additional layer of logic increases the risk of unintended consequences, requiring sophisticated modeling and optimization [4].

Metabolic Burden: As circuit complexity increases, the metabolic load on chassis cells can limit functionality and lead to performance degradation or selection for non-functional mutants [4]. Circuit compression strategies, such as those enabled by Transcriptional Programming, help mitigate this issue by reducing the number of genetic parts required for complex operations [4].

Context Dependency: Biological parts often behave differently across cellular contexts and environmental conditions, challenging the modularity assumption fundamental to synthetic biology [1] [4]. Developing context-insensitive parts and predictive models that account for cellular environment is an active research area [4].

Future directions include the development of more sophisticated wetware-software integration for quantitative prediction of genetic circuit performance, expansion of the synthetic biology toolkit for mammalian cells, and clinical translation of logic-gated therapies beyond oncology to autoimmune, neurological, and metabolic disorders [8] [4]. As regulatory frameworks evolve to accommodate these advanced therapies, logic-gated systems are poised to redefine precision medicine through unprecedented specificity in therapeutic intervention [8].

The development of sophisticated synthetic genetic circuits represents a frontier in therapeutic applications, enabling engineered cells to diagnose and treat diseases with unprecedented precision. The core of these "smart" living therapeutics is their ability to sense and process specific environmental inputs, triggering predefined therapeutic actions. This technical guide details the fundamental environmental inputs—small molecules, light, and disease biomarkers—that synthetic genetic circuits are engineered to perceive. We provide an in-depth analysis of the molecular mechanisms, quantitative performance data, and experimental methodologies underlying these sensing modalities, framed within the context of their clinical translation for therapeutic applications such as solid tumor therapy, T cell-mediated immunomodulation, and metabolic disease management [13].

Small Molecule Sensing

Small molecules serve as critical inputs for synthetic genetic circuits, providing a means to externally control therapeutic activity or sense pathological conditions. These inputs are typically detected by specialized proteins or nucleic acids that undergo conformational changes upon ligand binding, subsequently modulating gene expression.

Molecular Mechanisms

Transcription Factor-Based Sensors: Native or engineered transcription factors form the basis of many small molecule sensors. For instance, bacterial TetR and AraC families have been extensively repurposed. Ligand binding alters the transcription factor's DNA-binding affinity, thereby regulating downstream gene expression. This principle enables the construction of dose-responsive genetic switches for therapeutic control [2].

Aptamer-Based Sensors: Functional nucleic acids, known as aptamers, provide an alternative sensing mechanism. These single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides bind to specific small molecule targets (e.g., toxins, drugs, or metabolites) with high affinity and selectivity. Upon binding, the aptamer undergoes a structural switch, which can be designed to control gene expression by modulating translation initiation or transcription termination [14]. A prominent application is the detection of environmental contaminants like organophosphate pesticides or bisphenol A, where aptamers are selected against targets as diverse as cyanotoxins, mycotoxins, and heavy metals [14].

VHH-Based Immunosensors: For rapid, ready-to-use detection, heavy chain-only variable domain (VHH) antibodies can be paired with peptidomimetics. These components are fused to split protein fragments (e.g., NanoLuc luciferase). Target analyte presence disrupts the VHH-peptidomimetic interaction, preventing luciferase reconstitution and reducing luminescence, enabling wash-free, quantitative detection of small molecules like the herbicide 2,4-D [15].

Quantitative Performance of Small Molecule Sensors

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Small Molecule Sensors

| Sensing Mechanism | Target Molecule | Detection Limit | Dynamic Range | Response Time | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamer-Beacon [14] | Hg²⁺, Ag⁺, Cocaine | Low nM range | 3-4 orders of magnitude | Minutes | Environmental monitoring, diagnostics |

| Split Aptamer [14] | Kanamycin A, Cocaine | nM to µM | ~100-fold | Minutes | Food safety, clinical toxicology |

| VHH Immunosensor [15] | 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid | ~0.1 ng/mL | 0.01-1000 ng/mL | < 10 minutes | Agricultural monitoring, water safety |

| Transcription Factor [2] | Antibiotics, AHLs | µM range | 10-100 fold | Hours | Bioproduction, therapeutic gene control |

Experimental Protocol: Development of a Structure-Switching Aptamer Sensor

Objective: To select and implement a DNA aptamer that undergoes a target-induced conformational change for the detection of a small molecule toxin (e.g., Ochratoxin A) [14].

Materials:

- Library: Synthetic ssDNA library with a randomized central region (e.g., 40-60 nt).

- Target: Immobilized small molecule target (e.g., conjugated to magnetic beads).

- Buffers: Selection buffer (PBS with Mg²⁺), washing buffers.

- PCR Reagents: Primers, polymerase, dNTPs.

- Equipment: Magnetic rack, thermocycler, fluorometer or plate reader.

Procedure:

- In Vitro Selection (SELEX):

- Incubation: Incubate the ssDNA library with the immobilized target for 30-60 minutes.

- Partitioning: Use a magnetic field to separate bead-bound sequences from unbound ones.

- Washing: Wash beads thoroughly to remove weakly bound sequences.

- Elution: Elute specifically bound sequences using heat or denaturing conditions. For higher specificity, target-based elution with free small molecule can be used in later rounds.

- Amplification: Amplify the eluted pool by PCR. For ssDNA recovery, use asymmetric PCR or strand separation.

- Counter-Selection: To eliminate non-specific binders, perform negative selection rounds against the immobilization matrix without the target.

- Cloning and Sequencing: After 8-15 rounds of selection, clone the final pool and sequence individual clones to identify candidate aptamer families.

- Sensor Characterization:

- Labeling: Chemically synthesize the aptamer and label it with a fluorophore (e.g., FAM) and a quencher (e.g., Dabcyl) at its 5' and 3' ends.

- Assay: Incubate the labeled aptamer (e.g., 100 nM) with varying concentrations of the target in a buffer.

- Measurement: Monitor fluorescence intensity over time. The binding-induced structure change separates the fluorophore and quencher, increasing fluorescence.

- Analysis: Calculate KD from the fluorescence vs. concentration curve and determine the limit of detection (LOD) from the mean background signal plus three standard deviations.

Light Sensing

Light provides a highly spatiotemporal, tunable, and non-invasive input for controlling synthetic genetic circuits, making it ideal for precise therapeutic interventions.

Molecular Mechanisms

Cryptochromes: These are blue-light sensing flavoproteins found in plants and animals that regulate circadian rhythms. Upon blue light absorption, the flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor captures an electron, inducing a radical pair state. This triggers large-scale conformational changes, including the unfolding of protein regions, which ultimately control interactions with downstream signaling partners and modulate gene expression [16]. In Arabidopsis, cryptochrome (CRY1) signaling is positively regulated by the Ser/Thr phosphatase AtPP7, with antisense inhibition of AtPP7 resulting in a photomorphogenesis defect phenocopying the cry1 mutant [17].

Optogenetic Tools Based on Plant Phytochromes: Phytochromes sense red/far-red light via a bilin chromophore. Light-induced isomerization alters the protein's conformation and its interaction with signaling partners like PIFs (Phytochrome Interacting Factors), which can be harnessed to control gene expression or protein localization [2].

Engineered Light-Sensing Systems: Natural photoreceptors are often engineered for improved performance and integration into genetic circuits. A key strategy involves fusing light-sensitive domains (e.g., LOV2, CRY2) to effector domains. For instance, Cre recombinase activity has been made light-dependent by fusion with the LOV2 domain, which unfolds a C-terminal helix under blue light, activating the enzyme [2]. Alternatively, splitting proteins and reconstituting them via light-inducible dimerization systems (e.g., using CRY2/CIB1 or PhyB/PIF pairs) allows for versatile control over a wide range of biological activities [2].

Quantitative Characterization of Light Sensors

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Representative Light Sensors

| Light Sensor | Wavelength | Activation Kinetics | Dynamic Range (ON/OFF ratio) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptochrome (CRY2) [16] | Blue (~450 nm) | Radical pair formation in ns-ms, full signaling in ~100 ms | N/A (Conformational change) | Circadian rhythm regulation, optogenetics |

| LOV2-based Cre [2] | Blue (~450 nm) | Seconds to minutes | >10-fold | DNA recombination, gene editing control |

| Phytochrome B (PhyB) [2] | Red (650 nm) / Far-Red (750 nm) | Seconds | >50-fold | Protein dimerization, nuclear translocation |

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing a Cryptochrome-Mediated Signaling Pathway

Objective: To validate the role of a candidate signaling component (e.g., phosphatase AtPP7) in a cryptochrome-mediated blue light signaling pathway using a phenotypic assay in plants [17].

Materials:

- Plant Lines: Wild-type (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0), cry1 mutant, and transgenic lines with inhibited expression of the candidate gene (e.g., AtPP7 antisense lines).

- Growth Chambers: Precisely controlled with adjustable blue light sources (e.g., LED panels).

- Equipment: Ruler, spectrometer, software for image analysis (e.g., ImageJ).

Procedure:

- Plant Growth and Genotyping:

- Surface-sterilize seeds of all genotypes.

- Sow seeds on identical growth media plates.

- Wrap plates in foil and stratify at 4°C for 2-4 days to synchronize germination.

- Genotype a small portion of the seedling tissue for each line to confirm identity.

- Light Treatment:

- Place all plates in a dark room under a safe green light.

- Expose one set of plates to continuous blue light (e.g., 50 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) and keep another set in complete darkness as a control for 3-5 days.

- Maintain constant temperature and humidity.

- Phenotypic Measurement:

- Hypocotyl Length Measurement: Carefully remove seedlings from the plates and lay them on agar. Capture digital images. Use image analysis software to measure the hypocotyl length of at least 20 seedlings per genotype per condition.

- Gene Expression Analysis (Optional): Harvest seedlings under light/dark conditions for RNA extraction. Perform RT-qPCR to analyze the expression of known cryptochrome-regulated genes (e.g., CHS, RBCS).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the average hypocotyl length and standard deviation for each group.

- Perform a statistical test (e.g., Student's t-test) to compare the hypocotyl length of the wild-type blue-light group versus the cry1 mutant and the candidate gene-inhibited lines. A similar de-etiolated phenotype (longer hypocotyls) in the candidate-inhibited lines and the cry1 mutant under blue light suggests the candidate functions in the CRY1 pathway.

Disease Biomarker Sensing

Sensing internal disease biomarkers allows synthetic genetic circuits to autonomously diagnose pathological states and initiate corrective therapies, forming the core of closed-loop therapeutic systems.

Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Targets

Transcriptional Profiling: Circuits can be designed to sense abnormal levels of specific transcription factors (TFs) or nuclear receptors that are hallmarks of disease. For example, in cancer, aberrant activity of TFs like NF-κB or p53 can be detected by incorporating their specific DNA-binding sites into synthetic promoters, driving the expression of therapeutic genes only in diseased cells [2] [13].

Protease Activity Sensors: Many diseases, including cancer and inflammation, are characterized by dysregulated protease activity. Synthetic circuits can incorporate protease-sensitive linkers that, when cleaved, release a transcription factor or activate a signaling molecule, thereby linking protease activity to a therapeutic output [2].

MicroRNA (miRNA) Sensors: Distinctive miRNA expression signatures are associated with various diseases and cell types. Synthetic circuits can detect these intracellular miRNAs using complementary antisense sequences. miRNA binding can be designed to destabilize a repressive mRNA secondary structure or trigger the degradation of a repressor transcript, leading to the expression of a therapeutic transgene [2].

Clinical Applications: These sensing mechanisms are being translated for:

- Solid Tumor Therapy: Circuits that sense tumor-specific biomarkers (e.g., surface antigens, hypoxia) to locally activate cytotoxic immune responses or induce apoptosis [13].

- T Cell Immunomodulation: Engineered CAR-T cells with circuits that sense multiple tumor antigens to improve specificity and safety, or that respond to small molecule inputs for controlled activation [13].

- Metabolic Disease Management: Circuits that sense metabolic waste products or hormone levels to regulate the production of therapeutic enzymes or hormones in real-time [13].

Detection Methods and Performance

Table 3: Biomarker Detection Methods for Diagnostic Integration

| Detection Method | Biomarker Examples | Limit of Detection | Throughput | Key Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital ELISA (Simoa) [18] | NfL, pTau181, GFAP | Femtomolar (fg/mL) | High / Automated | Alzheimer's, Multiple Sclerosis, TBI |

| Microfluidic Immunoassays [19] | PSA, CEA, CA-125 | Piconanomolar | Medium / Multiplexable | Cancer, Infectious Diseases |

| Imaging (PET/MRI) [18] | Amyloid-β, Tau, Myelin | N/A (Anatomical/Functional) | Low | Alzheimer's, Multiple Sclerosis |

| Electrochemical Aptasensors [14] | Ochratoxin A, Microcystin-LR | Nanomolar | High / Portable | Environmental Toxin Monitoring |

Experimental Protocol: Multiplexed Biomarker Detection on a Microfluidic Chip

Objective: To simultaneously detect multiple protein biomarkers (e.g., for cancer or infectious disease) from a small volume of serum or plasma using a PDMS-based microfluidic device with fluorescence detection [19].

Materials:

- Microfluidic Chip: Fabricated from PDMS via soft lithography, containing multiple parallel microchannels.

- Capture Antibodies: Array of specific antibodies immobilized in distinct zones within the microchannels.

- Samples and Reagents: Patient serum/plasma, detection antibodies conjugated with fluorescent tags (e.g., Alexa Fluor 647), washing buffers (PBS with Tween-20).

- Equipment: Fluorescence scanner or microscope, plasma cleaner for PDMS-glass bonding, pneumatic pressure system for fluid control.

Procedure:

- Chip Preparation and Functionalization:

- Fabrication: Create a master mold via photolithography. Pour PDMS base and curing agent (10:1 ratio) over the mold and bake. Peel off the cured PDMS and bond to a glass slide using oxygen plasma treatment.

- Antibody Immobilization: Flow solutions of capture antibodies (1-2 mg/mL in PBS) through individual channels and incubate overnight at 4°C. Block non-specific sites with BSA or casein.

- Sample Assay:

- Introduction: Dilute the patient serum sample (e.g., 1:10 in assay buffer) and introduce it into the microfluidic chip. Incubate for 15-30 minutes to allow biomarker binding to capture antibodies.

- Washing: Flush the channels with wash buffer to remove unbound proteins.

- Detection: Introduce the mixture of fluorescently-labeled detection antibodies and incubate for 15-30 minutes.

- Final Wash: Perform a final wash to remove unbound detection antibodies.

- Signal Readout and Analysis:

- Scanning: Place the chip in a fluorescence scanner to image the entire array.

- Quantification: Measure the fluorescence intensity at each capture spot. Generate a standard curve using known concentrations of recombinant biomarkers to convert intensity to concentration for each target.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Developing and Testing Environmental Sensors

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| VHH Antibodies [15] | Single-domain antibodies used for recognition; highly stable and expressible in cells. | Core component of ready-to-use immunosensors for small molecules. |

| DNA Aptamer Library [14] | A diverse pool of ssDNA sequences (10¹³-10¹⁵ variants) for in vitro selection against a target. | Starting material for selecting aptamers against toxins or biomarkers via SELEX. |

| NanoLuc Luciferase (Split) [15] | A engineered luciferase that can be split into two fragments which reconstitute upon interaction. | Reporter for protein-fragment complementation assays in immunosensors. |

| Cryptochrome (CRY2) Constructs [16] [17] | Blue-light sensitive protein used in optogenetics. | Engineered into circuits for light-dependent protein interaction or gene expression. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [19] | Silicone-based organic polymer used to fabricate microfluidic devices. | Material for creating lab-on-a-chip diagnostic devices for biomarker detection. |

| Ultra-Sensitive Immunoassay Kits (e.g., Simoa) [18] | Digital ELISA technology for detecting proteins at sub-femtomolar concentrations. | Gold-standard for validating low-abundance biomarker detection in biofluids. |

The precise sensing of environmental inputs—small molecules, light, and disease biomarkers—is the foundational capability that enables next-generation synthetic genetic circuits to function as intelligent therapeutics. This guide has detailed the core mechanisms, from aptamer-based switches and optogenetic proteins to intracellular miRNA sensors, that allow engineered cells to perceive their surroundings. The integration of these sophisticated sensing modalities, coupled with advances in delivery platforms and computational design, is poised to overcome existing challenges in safety and specificity. As the field matures, these input-sensing frameworks will be critical for realizing the full potential of dynamic, closed-loop therapies that autonomously diagnose and treat disease within the human body.

Cybergenetics represents a foundational shift in synthetic biology, introducing principles from control theory to engineer living cells with predictable and robust behaviors. This paradigm applies traditional engineering concepts, specifically feedback control systems, to biological processes, enabling the design of genetic circuits that function reliably despite inherent cellular noise and environmental perturbations [20] [21]. The core tenet of cybergenetics is the implementation of controllers that regulate biological processes (the "plant") by processing sensor measurements, comparing them to a desired reference signal, and computing corrective inputs delivered via actuators [21]. This closed-loop approach is increasingly critical for therapeutic applications, where precise, dependable control over cellular functions is necessary for effective treatments. By providing a framework to make synthetic genetic circuits more modular, scalable, and robust, cybergenetics directly addresses key challenges in deploying synthetic biology for human medicine, from dynamic metabolic engineering to next-generation cell-based therapies [22] [23].

Foundational Control Architectures in Cybergenetics

Cybergenetics implements feedback control using three primary architectural strategies, each with distinct advantages and implementation challenges for therapeutic development.

Embedded Controllers

Embedded controllers are synthetic gene regulatory networks constructed within the same cell that hosts the process to be controlled [21]. This strategy encodes the entire control system—sensing, computation, and actuation—into the host cell's genome. A primary advantage is self-sufficiency; once implemented, the controller operates autonomously without external equipment. This makes embedded control particularly suitable for in vivo therapeutic applications where continuous external monitoring is impractical [23]. However, significant challenges include the metabolic burden imposed by additional genetic elements, which can reduce host cell fitness and circuit performance [21]. Furthermore, embedded controllers often lack modularity, as any design modification requires complete re-engineering of the genetic circuit [21]. Promising applications in therapeutics include biomolecular integral feedback controllers that enable robust perfect adaptation, maintaining specific molecular outputs at constant levels despite environmental disturbances—a critical capability for consistent therapeutic protein production [21].

External (In Silico) Controllers

External control systems interface cells with computer-based controllers that monitor biological outputs and compute control inputs in real-time [21]. In this architecture, sensors measure cellular variables (e.g., gene expression via fluorescence), a computer algorithm processes these measurements against a reference setpoint, and actuators (such as pumps, optogenetic devices, or syringes) deliver precise inputs to the cells [21]. This approach offers unparalleled flexibility, as control algorithms can be modified in software without genetic re-engineering. It also eliminates the metabolic burden associated with embedded systems. However, external control requires specialized equipment and confines applications to in vitro settings, limiting direct therapeutic deployment [21]. This architecture has proven highly effective for fundamental research, including optogenetic regulation of gene expression and real-time cell cycle control, providing critical insights for developing next-generation embedded controllers [21].

Multicellular Controllers

Multicellular control represents an emerging paradigm that distributes control functions across different cell populations within a consortium [21]. Typically, one cell population is engineered to implement the control algorithm, while another contains the process to be regulated. This specialization alleviates the metabolic burden on individual cells and enhances modularity between sensing, computation, and actuation modules [21]. Cell-to-cell communication mechanisms, often through quorum-sensing molecules, enable coordination across the consortium. This architecture mirrors natural biological systems where division of labor improves overall system robustness. For therapeutic applications, multicellular control could enable sophisticated population-level behaviors, such as maintaining specific population ratios or implementing majority sensing for distributed decision-making [21]. Engineered population dynamics, including rock-paper-scissors systems, have also demonstrated improved genetic stability in microbial consortia, addressing a critical challenge in long-term therapeutic applications [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Cybergenetics Control Architectures for Therapeutic Development

| Control Architecture | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Therapeutic Application Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embedded Control | Autonomous operation; suitable for in vivo applications; closed-loop regulation | Metabolic burden; limited modularity; design complexity | High (for final therapeutic products) |

| External (In Silico) Control | High flexibility; no metabolic burden; powerful computation | Requires specialized equipment; limited to in vitro settings | Medium (for research and production) |

| Multicellular Control | Distributed burden; improved modularity; natural parallelism | Inter-population stability; communication reliability | Emerging (for complex consortia therapies) |

Experimental Implementation and Workflows

Implementing cybergenetic systems requires an iterative workflow combining computational modeling, genetic engineering, and experimental validation. The process begins with mathematical modeling of the biological process to be controlled, utilizing differential equations to capture system dynamics [21]. Control theorists then design appropriate control laws (e.g., proportional-integral-derivative controllers) to achieve desired performance specifications like stability, bandwidth, and reference tracking [23]. For embedded implementations, these abstract control laws are mapped to biomolecular components such as sensors, actuators, and computational elements [21]. Integral feedback controllers, for instance, have been implemented in mammalian cells using synthetic gene circuits to achieve perfect adaptation [21]. Following in silico simulation and validation, genetic circuits are assembled using standard parts (promoters, coding sequences, terminers) and introduced into host cells.

Experimental validation typically involves real-time monitoring of system outputs, often using fluorescent reporters, across varied reference signals and disturbance conditions [21]. For external control systems, this involves interfacing cultures with computer-controlled optogenetic stimulation or media delivery systems [21]. Performance metrics including settling time, overshoot, steady-state error, and disturbance rejection are quantified to assess controller effectiveness. Iterative refinement cycles then optimize controller parameters or architectures to improve performance. This rigorous methodology transforms abstract control principles into functional biological systems capable of robust regulation in noisy cellular environments.

Advanced Control Strategies for Therapeutic Applications

Advanced control strategies in cybergenetics move beyond simple regulation to implement sophisticated computational and dynamic behaviors with direct therapeutic relevance.

Integral Feedback for Perfect Adaptation

Biomolecular integral feedback controllers represent a landmark achievement in cybergenetics, enabling robust perfect adaptation where system outputs precisely track reference signals despite unknown disturbances or parameter variations [21]. This capability is critically important for therapeutic applications where consistent dosing is essential, particularly in metabolic disorders where enzyme levels must be maintained within narrow therapeutic windows. Natural biological systems employ integral feedback extensively in homeostasis mechanisms, and synthetic implementations have been demonstrated in both bacterial and mammalian cells [21]. The Antithetic Integral Feedback motif, utilizing two opposing species that annihilate each other, provides a general implementation that achieves perfect adaptation through a sequestration mechanism [21]. Implementation challenges include addressing the "leaky integration" caused by protein dilution during cell growth, which has been mitigated through controller designs that account for this intrinsic biological process [21].

Optogenetic Control Systems

Optogenetic control combines light-sensitive proteins with genetic circuits to enable precise spatiotemporal regulation of cellular processes [21]. This approach offers exceptional temporal resolution (seconds to minutes) and spatial specificity through targeted illumination. In cybergenetics, optogenetic systems serve as both sensors and actuators in external control configurations, with applications including real-time cell cycle synchronization in yeast and precise pattern formation in bacterial populations [21]. For therapeutic development, optogenetic control provides a powerful research tool for probing disease mechanisms and testing intervention strategies with unprecedented precision. Clinical applications are emerging in neuromodulation and could expand to include light-regulated gene therapies for conditions requiring precise dosing control.

Burden-Driven Feedback Control

Cellular resource competition creates a significant challenge for synthetic circuit performance, as gene expression burden can reduce host cell fitness and circuit function [21]. Burden-driven feedback controllers directly address this limitation by dynamically regulating synthetic circuit activity in response to the cellular resource status. These systems monitor global cellular markers like growth rate or energy charge and adjust heterologous gene expression accordingly [21]. This approach enhances circuit robustness and host cell viability, particularly important for long-term therapeutic applications where sustained circuit function is essential. Implementation strategies include monitoring ribosomal demand and coupling it to feedback regulation of synthetic gene expression [21].

Table 2: Advanced Control Strategies for Therapeutic Applications

| Control Strategy | Core Principle | Key Implementation | Therapeutic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integral Feedback Control | Elimination of steady-state error through continuous adjustment | Antithetic motif (two opposing species); biomolecular implementation | Homeostatic regulation; consistent therapeutic protein production |

| Optogenetic Control | Light-sensitive regulation with high spatiotemporal precision | External computer interface with light-emitting hardware | Precuneuromodulation; research tool for disease mechanisms |

| Burden-Driven Control | Regulation based on cellular resource availability | Ribosomal demand sensors; growth rate coupling | Long-term circuit stability; reduced cellular toxicity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing cybergenetic systems requires specialized reagents and tools that enable the construction, measurement, and control of synthetic genetic circuits.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cybergenetics

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery of CRISPR components; enables redosing [24] | CRISPR-based therapies for liver diseases; personalized treatments |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Genome editing; programmable DNA targeting [24] [22] | Gene knock-out/knock-in; disease modeling; therapeutic gene disruption |

| Optogenetic Actuators | Light-controlled proteins for precise temporal regulation [21] | Real-time control of gene expression; pattern formation studies |

| Quorum Sensing Molecules | Intercellular communication for multicellular systems [21] | Distributed computation; population-level control |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Real-time monitoring of gene expression and circuit dynamics [21] | System characterization; feedback sensor inputs |

| TALENs/ZFNs | Alternative genome editing tools for specific applications [22] | Chromosomal rearrangement modeling; disease mechanism studies |

Case Studies: Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Development

Cybergenetics principles are already enabling innovative therapeutic approaches with demonstrated clinical potential.

CRISPR-Based Therapies with Enhanced Delivery

Recent advances in CRISPR-based medicines highlight the importance of delivery systems as critical actuators in therapeutic cybergenetic systems. The first FDA-approved CRISPR therapy, Casgevy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, represents a breakthrough in genetic medicine [24]. Further innovation was demonstrated through the first personalized in vivo CRISPR treatment for an infant with CPS1 deficiency, developed and delivered in just six months [24]. This case employed lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) for delivery, enabling multiple doses to increase editing efficiency—a significant advantage over viral delivery methods that typically preclude redosing due to immune reactions [24]. This approach exemplifies how advanced delivery technologies expand the controllability of genetic interventions.

Intelligent Microbial Therapies

Synthetic biology has engineered microbial systems for therapeutic purposes, including CRISPR-enhanced phage therapies that target antibiotic-resistant bacteria [24]. These systems utilize bacteriophages armed with CRISPR constructs to selectively eliminate pathogenic bacteria while preserving beneficial microbiota. Such approaches implement sophisticated targeting logic—a form of embedded control—that distinguishes between bacterial strains based on genetic signatures. This precision represents a significant advance over conventional antibiotics and demonstrates how cybergenetic principles can enhance specificity and safety in antimicrobial therapies.

Future Directions and Challenges

The continued maturation of cybergenetics faces several key challenges that will determine its impact on therapeutic development. Delivery remains a fundamental constraint, with current methods like LNPs showing strong tropism for the liver but limited targeting of other tissues [24]. Expanding the delivery toolbox to enable tissue-specific targeting is essential for broadening therapeutic applications. Scalability presents another significant hurdle, as the field must transition from bespoke solutions for individual patients to broadly applicable platforms [24]. This requires developing more modular, standardized control modules that can be adapted across disease contexts without complete re-engineering. Additionally, safety assurance for increasingly autonomous genetic controllers demands new analytical frameworks and containment strategies to ensure reliable operation in clinical settings. Despite these challenges, the integration of control theory with synthetic biology continues to provide powerful strategies for engineering biological systems with therapeutic potential, moving the field closer to predictable, reliable genetic medicine.

From Bench to Bedside: Engineering Circuits for Cancer, Metabolic and Inflammatory Diseases

Synthetic biology is revolutionizing oncology by providing tools to engineer intelligent therapies capable of precisely distinguishing malignant from healthy cells. These advanced therapeutic systems function as molecular computers that detect intracellular disease signatures and execute programmed responses with unprecedented specificity. The foundational principle involves designing synthetic genetic circuits that perform logical operations based on the presence or absence of specific cancer biomarkers, thereby restricting therapeutic activity exclusively to tumor cells. This paradigm represents a significant evolution from conventional cancer treatments, which often lack selectivity and produce dose-limiting toxicities.

Two particularly promising approaches exemplify this next generation of precision cancer therapeutics. First, RAS-targeting synthetic gene circuits directly sense and target one of the most frequently mutated oncogene families in human cancers, employing sophisticated multi-input sensing to achieve unprecedented selectivity. Second, logic-gated chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells utilize combinatorial antigen sensing to distinguish tumor cells from healthy tissues, thereby addressing the critical challenge of on-target, off-tumor toxicity that has limited conventional CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors. Both strategies leverage the core principles of synthetic biology—modular design, standardized biological parts, and logical computation—to create living medicines with enhanced safety profiles and potent anti-cancer activity [1] [25].

RAS-Targeting Synthetic Gene Circuits

Rationale and Molecular Basis

The RAS gene family (HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS) represents the most frequently mutated oncogene in human cancers, with mutations occurring in approximately 19% of all cases. KRAS is the most commonly mutated isoform, accounting for a significant portion of pancreatic, colorectal, and lung cancers. For decades, RAS was considered "undruggable" due to the challenges in targeting its protein structure and function. While recent approvals of KRASG12C inhibitors represent a breakthrough, these therapies are limited to a specific KRAS mutation and remain susceptible to resistance development [5].

Synthetic gene circuits offer a promising alternative approach by sensing and integrating cancer-specific biomolecular inputs, including mutated RAS, to selectively express therapeutic proteins exclusively in cancer cells. A paramount challenge for these circuits lies in achieving sufficiently high cancer selectivity to prevent toxicity in healthy cells. To address this limitation, researchers have developed novel circuits that combine multiple RAS sensors in logical configurations, enabling expression of output proteins in cells with mutated RAS with unprecedented selectivity [5].

Circuit Design and Mechanism

The RAS-targeting circuit employs a sophisticated design inspired by natural RAS signaling biology. The system capitalizes on the selective binding of CRAF's RAS-binding domain/cysteine-rich domain (RBDCRD) to activated RAS-GTP. In cancer cells with mutated RAS, the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP is impaired, resulting in constitutively active RAS-GTP that drives uncontrolled proliferation [5].

Core Circuit Components:

- RBDCRD-NarX Fusion Proteins: Chimeric constructs fusing the RBDCRD domain to engineered truncated and mutated NarX variants (NarX379–598H399Q and NarX379-598N509A) derived from bacterial two-component systems. These variants transphosphorylate in mammalian cells only upon forced dimerization via fused protein domains.

- Humanized NarL Response Regulator: A phosphorylation-activated transcription factor that binds to specific response elements upon activation.

- NarL-Responsive Promoter: Drives expression of output proteins (e.g., therapeutic agents) only when activated by phosphorylated NarL.

Mechanism of Action: In the presence of activated RAS-GTP (abundant in cancer cells with RAS mutations), the RBDCRD domains bind to RAS, forcing dimerization of the fused NarX variants. This dimerization triggers transphosphorylation between NarXH399Q and NarXN509A, leading to phosphorylation of the humanized NarL transcription factor. Phosphorylated NarL then binds to its response element on the NarL-responsive promoter, inducing expression of the output protein (e.g., mCerulean for detection or therapeutic proteins for cell killing) [5].

Table 1: Key Components of the RAS-Sensing Gene Circuit

| Component | Type | Function | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBDCRD | Protein domain | Binds activated RAS-GTP | Human CRAF protein |

| NarX379–598H399Q | Engineered protein | Transphosphorylates NarXN509A upon dimerization | Bacterial two-component system |

| NarX379-598N509A | Engineered protein | Receives phosphorylation from NarXH399Q | Bacterial two-component system |

| Humanized NarL | Transcription factor | Activates output expression upon phosphorylation | Bacterial two-component system (modified) |

| NarL-responsive promoter | DNA regulatory element | Drives output gene expression when bound by phosphorylated NarL | Synthetic/Bacterial |

Experimental Validation and Performance

The RAS-sensing circuit was rigorously validated in multiple cancer cell lines, demonstrating significantly higher output expression in cells expressing oncogenic KRASG12D compared to those with wild-type KRAS. The system showed dose-dependent response to both the level of mutant KRAS expression and the amount of sensor-encoding plasmids delivered to cells [5].

Critical evidence supporting the specific RAS-dependence of the circuit came from domain mutation experiments. Mutating key residues in the RAS binding domain (R89L) and cysteine-rich domain (C168S) – residues known to be critical for RAS-RAF signaling – substantially reduced or abolished output expression, confirming that circuit activation requires specific RAS binding [5].

Furthermore, researchers directly correlated RAS-GTP levels with circuit output using RAS pulldown ELISA assays. By manipulating RAS-GTP levels in HEK293 cells through expression of different amounts of KRASWT, KRASG12D, or KRASWT with the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Sos-1, they demonstrated that higher RAS-GTP levels directly corresponded to increased output expression [5].

The modular design of these circuits enables cell-line specific adaptation to optimize selectivity and fine-tune expression levels. When linked to the expression of a clinically relevant therapeutic protein, these circuits induced robust killing of cancer cells with mutated RAS while sparing healthy cells, highlighting their therapeutic potential [5].

Logic-Gated CAR-T Cell Therapies

Foundations and Clinical Challenges

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a groundbreaking approach in cancer immunotherapy, wherein a patient's T cells are genetically engineered to express synthetic receptors that redirect their specificity toward tumor antigens. This approach has demonstrated remarkable success in treating hematological malignancies, with six FDA-approved products for B-cell lineage cancers. However, the application of CAR-T therapy to solid tumors has faced significant challenges, primarily due to the lack of truly tumor-specific surface antigens and the occurrence of on-target, off-tumor toxicity [26] [25].

The fundamental problem stems from the nature of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) – these antigens are overexpressed on tumor cells but also present at lower levels on essential healthy tissues. When CAR-T cells target these antigens, they can attack normal cells expressing the target, potentially causing severe adverse effects. For example, cases of fatal toxicity have occurred when anti-HER2 CAR-T cells targeted HER2 expressed at low levels on lung epithelium [25].

Logic Gate Architectures for Enhanced Specificity

Logic-gated CAR-T cells address the specificity challenge by requiring the recognition of multiple antigens to trigger full T-cell activation. These systems operate according to Boolean logic principles, integrating multiple antigen inputs to generate an output (T-cell activation) only when specific combinatorial conditions are met [1] [25].

Table 2: Types of Logic Gates in CAR-T Cell Design

| Logic Gate | Activation Condition | Mechanism | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| AND | Two antigens simultaneously | Split signaling domains across two receptors | Prostate cancer: PSCA (signal 1) + PSMA (signal 2) |

| OR | Either antigen present | Multiple antigen recognition domains | Targets heterogeneous tumors with antigen loss |

| NOT | Absence of an antigen | Inhibitory CAR blocks activation | Spares healthy cells expressing "self" marker |

| AND-NOT | Presence of antigen A AND absence of antigen B | Combination of activating and inhibitory signals | Targets tumor antigen while sparing healthy tissue |

AND Gate Designs: The most common logic-gated approach utilizes AND gate circuits that require simultaneous recognition of two antigens for full T-cell activation. One prominent strategy employs split CARs that separate the T-cell activation (CD3ζ) and costimulatory (CD28, 4-1BB) signaling domains across two different receptors, each recognizing a distinct tumor antigen. For instance, in prostate cancer, one CAR provides signal 1 (CD3ζ) through recognition of prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA), while a second CAR provides signal 2 (CD28/4-1BB) through recognition of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). This design ensures that only cells expressing both antigens trigger full T-cell activation capable of mediating target cell killing [25].

An alternative AND gate design co-opts proximal T-cell signaling proteins to create a more precise activation system. This approach links the adapter protein LAT to a scFv recognizing antigen 1 and SLP-76 to a scFv recognizing antigen 2. Only when both receptors engage their respective targets does proper clustering occur, triggering robust T-cell activation. To further reduce leaky activation from single antigens, researchers have introduced mutations in transmembrane domains to prevent heterodimerization and removed binding sites for bridging proteins like GADS [25].

Computational Identification of Optimal Antigen Combinations: Recent advances have introduced computational approaches like LogiCAR designer, which utilizes single-cell transcriptomics data from patient tumors to systematically identify optimal antigen combinations for logic-gated CAR therapies. This algorithm efficiently screens circuits involving up to five genes with AND, OR, and NOT logic to maximize tumor targeting while minimizing off-tumor effects. Applied to breast cancer datasets encompassing approximately 2 million cells from 342 patient samples, LogiCAR designer identified circuits with superior performance compared to both single-target therapies and previously reported circuits [27].

Notably, the analysis revealed that while shared circuits optimized across patient populations offer moderate improvements, truly personalized CAR circuits tailored to individual patients could achieve estimated tumor-targeting efficacy tantamount to complete response in 76% of patients, highlighting the potential of precision immunotherapeutic design [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Implementation of RAS-Sensing Gene Circuits

Circuit Assembly and Delivery: