Orthogonal Transcription Factor Systems: Engineering, Applications, and Validation for Advanced Genetic Control

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of orthogonal transcription factor (TF) systems, a cutting-edge toolset in synthetic biology for decoupling genetic circuits from host regulatory networks.

Orthogonal Transcription Factor Systems: Engineering, Applications, and Validation for Advanced Genetic Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of orthogonal transcription factor (TF) systems, a cutting-edge toolset in synthetic biology for decoupling genetic circuits from host regulatory networks. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of orthogonal TFs, including bacterial σ54 factors and phage-derived RNA polymerases. The scope covers methodological advances in their design and deployment, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing system performance, and rigorous validation across diverse bacterial chassis. By synthesizing recent breakthroughs, this review serves as a critical resource for the application of these systems in programming complex cellular functions, from metabolic engineering to intelligent drug development.

Core Principles and the Expanding Universe of Orthogonal Transcription

In synthetic biology, orthogonality refers to the design of genetic systems that operate independently of the host cell's native regulatory networks. This decoupling is crucial for ensuring that engineered gene circuits function predictably and robustly without interference from host processes or unintended impact on host viability. The pursuit of orthogonality has become a central theme in advancing therapeutic applications, including gene and cell therapy, where precise control over genetic output is paramount [1]. This guide provides a comparative evaluation of current orthogonal transcription factor (TF) systems, detailing their performance metrics, experimental methodologies, and key reagent solutions for research and development.

Comparative Analysis of Orthogonal Genetic Systems

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and performance data of four major classes of orthogonal genetic systems, highlighting their key features and experimentally measured orthogonality.

Table 1: Comparison of Orthogonal Genetic Systems for Synthetic Biology

| System Type | Core Components | Mechanism of Orthogonality | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ54 Factor Variants [2] | Engineered σ54 (R456H/Y/L), cognate promoters, bEBPs | Rewired promoter recognition specificity; requires activation by bEBPs. | Ideal mutual orthogonality between variants; specific transcription demonstrated in 3+ non-model bacteria. | Eukaryotic-like regulation; low basal leakage; high fold change upon induction. |

| λ cI TF Variants [3] | Engineered λ cI repressor/activator variants, synthetic bidirectional promoters. | Modified protein-DNA binding specificity to engineered operator sites. | 12 orthogonal TFs operating on up to 270 synthetic promoters. | Flexible operation as activators/repressors; slots into existing projects. |

| Phage RNAP Mutators (OTM) [4] | Deaminase-MmP1/K1F/VP4 RNAP fusions, orthogonal phage promoters. | Phage polymerase specificity for its own promoter; targeted mutagenesis. | >1,500,000-fold increased mutation rates; high specificity (minimal off-target effects). | Accelerated protein evolution; broad-host-range functionality. |

| Prime TF Reporters [5] | Optimized synthetic DNA response elements, minimal core promoters. | Optimized TF-specific response elements with minimal cross-reactive motifs. | High sensitivity & specificity for 62 TFs; outperform available reporters in >80% of comparisons. | Direct, multiplexed TF activity measurement; covers diverse signaling pathways. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Orthogonality

Protocol for Testing σ54 Orthogonality

This protocol is adapted from studies that expanded the σ54-dependent transcription system [2].

- Step 1: Construct Generation. Clone mutant σ54 genes (e.g., R456H, R456Y, R456L) and their partnered promoter sequences into separate expression plasmids. A broad-host-range plasmid vector (e.g., pBBR-derived) is recommended for transferability testing.

- Step 2: Host Strain Preparation. Generate a ΔrpoN knockout strain in E. coli using λ-red homologous recombination to eliminate the native σ54 factor, providing a clean background.

- Step 3: Reporter Assay. Co-transform the σ54 variant and its corresponding promoter driving a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP) into the ΔrpoN host. Include controls with non-cognate σ54-promoter pairs.

- Step 4: Specificity Measurement. Quantify fluorescence output to assess activation by the cognate pair. Measure the fold-change difference in output between cognate and non-cognate pairs to quantify orthogonality. A high signal from the cognate pair with minimal background from non-cognate pairs indicates strong mutual orthogonality.

- Step 5: Cross-Activation Test. Repeat the assay in multiple bacterial species (e.g., Klebsiella oxytoca, Pseudomonas fluorescens) to validate the transferability of the orthogonal system.

Protocol for Profiling TF Activity with Prime Reporters

This protocol outlines the use of massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) for evaluating orthogonal TF reporters [5].

- Step 1: Library Design and Cloning. Design a library of reporter constructs for each TF. Systematically vary key features, including the number of TF binding sites, spacer sequences and length between sites, and the core promoter sequence. Clone these constructs into a plasmid library, each associated with a unique DNA barcode.

- Step 2: Cell Transfection and Perturbation. Transfer the reporter library into the target cell line. Subject the cells to a wide array of TF perturbation conditions—including TF knockouts, overexpression, and pathway stimulation—to activate diverse TFs.

- Step 3: Barcode Sequencing and Analysis. After a set period, extract cellular RNA and sequence the barcode regions. The abundance of each barcode in the RNA pool serves as a direct measure of the transcriptional activity of its associated reporter.

- Step 4: Sensitivity and Specificity Calculation. For a given TF perturbation, the sensitivity of a reporter is its level of activation. Specificity is determined by calculating the ratio of its activity under its cognate TF perturbation versus its activity under all other non-cognate perturbations. The reporters with the highest sensitivity and specificity are designated "prime" reporters.

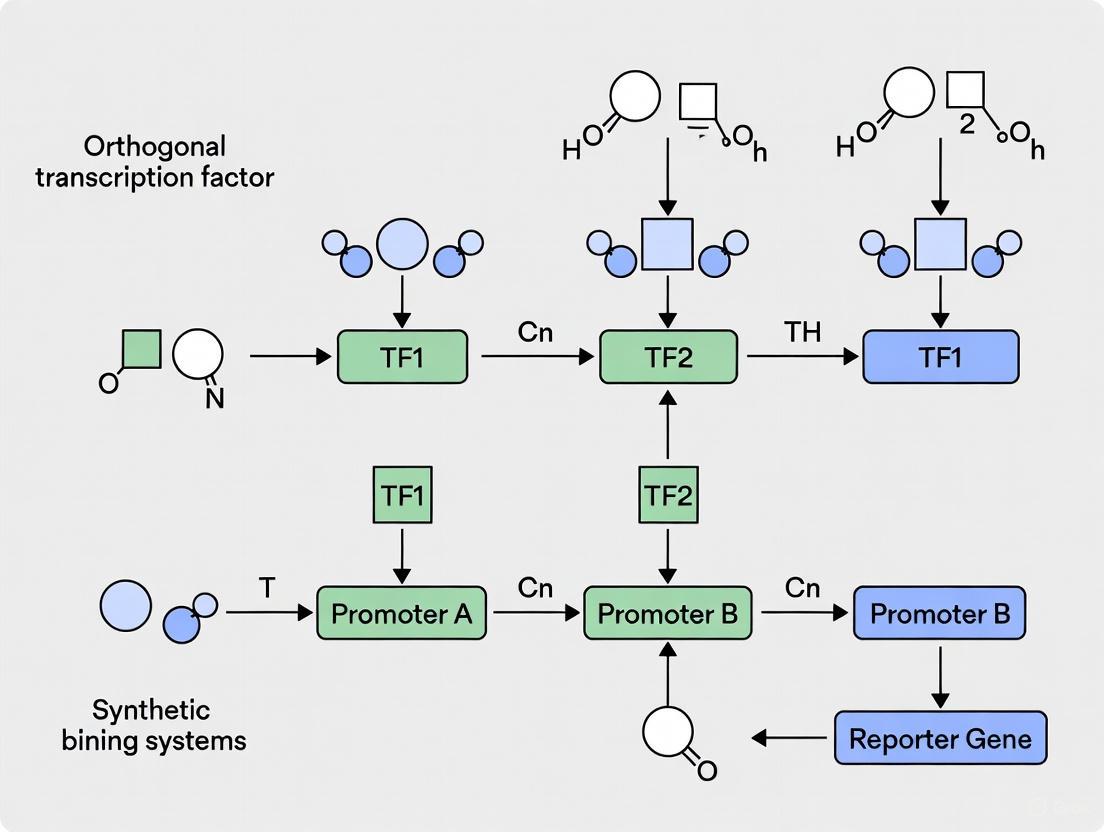

System Workflows and Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the core architectures and functional workflows of two primary orthogonal systems.

σ54-Dependent Orthogonal Transcription

Diagram Title: σ54 Orthogonal System Activation

λ cI-Based Orthogonal Logic Gate

Diagram Title: λ cI Bidirectional Logic Gate

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below catalogs key reagents and their functions essential for designing and testing orthogonal genetic systems.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Orthogonal System Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered σ Factors [2] | Provides promoter recognition specificity orthogonal to native host σ factors. | σ54 variants (R456H, R456Y, R456L) with distinct, non-cross-reacting promoter preferences. |

| Bacterial Enhancer-Binding Proteins (bEBPs) [2] | Required activator for σ54-dependent transcription; enables AND-gate logic. | Proteins like NifA; can be regulated by environmental or chemical signals for inducible control. |

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors [3] | Engineered DNA-binding proteins that regulate synthetic promoters without affecting native genes. | λ cI variant TFs that can function as activators, repressors, or dual-function switches. |

| Synthetic Promoter Libraries [5] [3] | DNA sequences containing optimized binding sites for orthogonal TFs, driving expression of downstream genes. | Bidirectional promoters for λ cI; promoters with varied spacer sequences for tuning output strength. |

| Phage RNA Polymerases [4] | Provides orthogonal transcription and a platform for targeted, in vivo mutagenesis systems. | MmP1, K1F, VP4 RNAPs; can be fused to deaminases (e.g., PmCDA1) for continuous evolution. |

| Prime TF Reporters [5] | Optimized DNA reporter constructs to directly and sensitively measure the activity of specific TFs in living cells. | A collection of 62 highly specific reporters for TFs from pathways like MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and TGF-β. |

| Conditional Phage/Phagemid Systems [3] | A selection platform for evolving new orthogonal TF-promoter pairs inside host cells. | M13 phagemid system linking TF activity to essential phage gene (gVI) production for enrichment. |

In the pursuit of predictable and customizable genetic circuits in synthetic biology, the concept of orthogonality—where a system operates without crosstalk with the host's native processes—is paramount. Among the various molecular tools, bacterial sigma factors represent a primary mechanism for promoter recognition and transcription initiation. The σ54 factor, a specialized alternative sigma factor, occupies a unique regulatory niche distinct from the housekeeping σ70 factor. Its inherent biological characteristics, including stringent dependence on activator proteins and distinct promoter recognition sequences, provide a native and robust platform for orthogonal design [6] [7]. This guide objectively evaluates the performance of σ54-based orthogonal systems against other prevalent transcriptional regulators, providing a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in engineering complex biological systems.

Comparative Analysis of Orthogonal Transcriptional Systems

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of σ54-based systems against other common transcriptional regulators used in synthetic biology, highlighting key performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Orthogonal Transcriptional Systems

| System Feature | σ54-Dependent System | σ70-Dependent System (e.g., TetR, LacI) | AraC/PBAD System | CRISPRa (σ54-based) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native Regulation | Stress responses, nitrogen metabolism [6] | Housekeeping & stress responses [6] | Carbon metabolism [8] | N/A (fully engineered) |

| Core Promoter Recognition | -24 / -12 (GG-N10-GC) [6] | -35 / -10 (TTGACA-N17-TATAAT) [6] | -35 / -10 site [8] | σ54-dependent promoter [9] |

| Activation Mechanism | ATP-dependent remodeling by bEBPs [6] | Spontaneous isomerization [6] | Conformational change in AraC [8] | Engineered dCas9-PspF fusion [9] |

| Typical Dynamic Range | > 1,000-fold [9] | ~10-100 fold | ~7-fold improvement possible [8] | > 1,000-fold [9] |

| Key Orthogonality Feature | Distinct promoter sequence & energy requirement [6] [10] | Operator sequence engineering | Operator sequence engineering | sgRNA-programmable UAS targeting [9] |

| Demonstrated Orthogonal Pairs | 3 (σ54-R456H, R456Y, R456L) [10] | Multiple (e.g., TetR, LacI) | Limited by host AraC | 1 (PspF-based) [9] |

Structural and Functional Basis for σ54 Orthogonality

Fundamental Mechanisms of σ54-Dependent Transcription

Unlike σ70-dependent transcription, which can often proceed spontaneously, σ54-dependent transcription is inherently locked in a closed complex. This complex requires ATP-dependent remodeling by specialized bacterial enhancer-binding proteins (bEBPs) to isomerize into an open complex capable of initiation [6]. This energy-dependent switch provides a fundamental layer of control not present in other systems. Structurally, σ54 achieves this inhibition through its Region I (RI) and an extra-long helix (ELH) in Region III, which physically block the DNA entry channel of RNA polymerase, preventing spontaneous DNA opening [6].

Orthogonal Engineering of the σ54-Promoter Interface

The primary strategy for creating orthogonal σ54 systems involves rewiring the specific interaction between the sigma factor and its target promoter. The RpoN domain within σ54's Region III is responsible for recognizing the conserved -24/-12 promoter element [6]. Research has demonstrated that targeted mutations in this domain, particularly at residue R456, can rewire promoter specificity. For instance, the mutations σ54-R456H, R456Y, and R456L were shown to create three mutually orthogonal sigma factor variants, each with distinct promoter preferences and minimal crosstalk with each other or the native σ54 [10]. This orthogonality was successfully transferred into three non-model bacteria, showcasing its robustness and broad-host applicability [10].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for σ54 System Engineering

| Reagent / Method | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Enhancer-Binding Proteins (bEBPs) | AAA+ ATPases that remodel σ54-RNAP closed complex; can be engineered for orthogonal control [6] [7] | Nla28 from M. xanthus used to activate natural product gene promoters [7] |

| Machine Learning (BT Model) | Computational tool to identify critical residue regions (CRRs) in transcription factors for engineering [11] | Narrowed down 669 residues in BmoR to 36 key residues for achieving strict signal molecule orthogonality [11] |

| Sort-Seq | Massively parallel reporter assay to map regulatory sequences at nucleotide resolution [8] | Used to characterize and improve arabinose (PBAD) and rhamnose (PRha) inducible promoters [8] |

| Orthogonal σ54 Variants (e.g., R456H/Y/L) | Engineered sigma factors with rewired promoter specificity for orthogonal gene circuits [10] | Used to orthogonalize complex biological pathways and genetic circuits in multiple bacterial hosts [10] |

| PspFΔHTH::λN22plus | A truncated, modular activation domain from bEBP PspF for synthetic systems [9] | Fused to RNA-binding peptides in eukaryote-like CRISPRa systems to activate σ54-dependent promoters [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Engineering and Validation

Protocol 1: Engineering Orthogonal σ54-Promoter Pairs

This protocol is adapted from the method used to create the orthogonal σ54-R456 mutants [10].

- Target Identification: Based on structural knowledge, target the RpoN domain, specifically the residues involved in -24/-12 promoter recognition (e.g., R456) [6] [10].

- Saturation Mutagenesis: Perform site-directed mutagenesis on the key residue (e.g., R456) to generate a library of σ54 variants.

- Promoter Library Design: In parallel, create a library of promoter variants with mutations in the -24/-12 region.

- Combinatorial Screening: Co-transform the σ54 variant library and promoter library into a reporter strain (e.g., carrying GFP) and use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate pairs that show strong activation only when matched.

- Orthogonality Validation: Test the top-performing σ54-promoter pairs against each other and the native system to confirm minimal cross-activation.

Protocol 2: Measuring Orthogonality and Dynamic Range

This protocol is used to quantitatively assess the performance of engineered systems [10] [9].

- Strain Construction: Create reporter strains where the expression of a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) is under the control of the orthogonal promoter.

- Transformation: Introduce the plasmid encoding the orthogonal σ54 variant and its cognate bEBP (if required) into the reporter strain.

- Culture and Induction: Grow bacterial cultures to mid-log phase and, if using an inducible bEBP, add the specific inducer.

- Flow Cytometry: Measure the fluorescence intensity of thousands of individual cells using a flow cytometer. The mean fluorescence of the induced population indicates the ON state.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the dynamic range as the ratio of the mean fluorescence in the fully induced (ON) state to the non-induced or non-cognate (OFF) state. Orthogonality ratio is calculated as the ON signal with the cognate factor divided by the ON signal with a non-cognate factor.

Diagram 1: Orthogonal System Engineering Workflow

Advanced Applications and Comparative Performance

σ54 in CRISPR-Based Activation Systems

The unique "eukaryote-like" properties of σ54 have been leveraged to create highly effective CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems. In one design, a truncated activation domain of the bEBP PspF (PspFΔHTH) was fused to an RNA-binding peptide (λN22plus) and recruited to a dCas9-sgRNA complex. This system, which targets σ54-dependent promoters, demonstrated a dynamic range exceeding 1000-fold and could be programmed for multi-input regulation due to the long-distance action of bEBPs [9]. This performance significantly surpasses that of early σ70-based CRISPRa systems, which were limited by the need for the dCas9 complex to be near the core promoter and often showed lower dynamic ranges [9].

Regulation of Natural Product Biosynthesis

σ54 systems are directly implicated in regulating bacterial natural product genes, which are crucial sources of therapeutics. In Myxococcus xanthus, σ54 promoters, activated by specific bEBPs like Nla28, control the expression of polyketide and non-ribosomal peptide gene clusters [7]. This regulatory link often ties natural product synthesis to changes in nutritional status, providing a native paradigm for using orthogonal σ54 systems to dynamically control the expression of biosynthetic pathways in response to engineered signals.

Diagram 2: σ54 Transcription Activation Pathway

The σ54 factor provides a uniquely powerful and native foundation for constructing orthogonal transcriptional systems in bacteria. Its inherent separation from σ70-driven housekeeping transcription, coupled with its mandatory requirement for ATP-dependent activation, offers layers of control that are difficult to achieve with other systems. Quantitative data confirms that well-engineered σ54 systems can achieve dynamic ranges exceeding 1000-fold, support multiple orthogonal channels within a single cell, and function across diverse bacterial species [10] [9]. While σ70-based systems and classical repressor-based switches (like TetR/LacI) remain useful for many applications, the σ54 paradigm is particularly superior for applications demanding ultra-low leakage, high-level expression, and complex, multi-input logic. As synthetic biology continues to move into non-model chassis and demand more sophisticated genetic circuitry, the σ54 system, especially when combined with modern tools like machine learning and CRISPR, is poised to be an indispensable component of the genetic engineer's toolkit.

Orthogonal transcription systems, which function independently of the host's native transcriptional machinery, are foundational tools in synthetic biology. These systems enable precise control over gene expression for applications ranging from fundamental research to industrial bioproduction and therapeutic development. Bacteriophage-derived RNA polymerases represent the most established and widely adopted orthogonal transcription systems. Among them, the T7 RNA polymerase (T7RNAP) system is considered the gold standard, prized for its high transcriptional activity and exceptional specificity for its cognate promoter. T7RNAP exhibits a transcriptional rate approximately five-fold higher than that of native Escherichia coli RNA polymerase [12]. Furthermore, its operation as a single-subunit enzyme—requiring no additional protein factors for function—simplifies its deployment across biological chassis [12].

The core principle of orthogonality ensures that the phage polymerase and its associated promoter sequence interact minimally with the host's regulatory networks. This allows synthetic genetic circuits to operate without unintended crosstalk, facilitating the predictable engineering of microbial cell factories (MCFs), advanced biosensors, and sophisticated gene expression controls. While T7RNAP has dominated the field for decades, recent research has significantly expanded the synthetic biology toolbox. The discovery and engineering of alternative phage polymerases, such as MmP1, K1F, and VP4, now provide a broader palette of orthogonal systems. These alternatives are vital for overcoming limitations of the T7 system, particularly its restricted host range and inefficient performance in non-model organisms, thereby unlocking new possibilities for genetic manipulation across diverse bacterial species [4].

Comparative Analysis of Phage Polymerases

This section provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of the performance characteristics of T7RNAP and other emerging orthogonal phage RNA polymerases, highlighting their specific advantages and suitable application contexts.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Orthogonal Phage RNA Polymerases

| Polymerase | Primary Hosts | Transcription Rate | Key Advantages | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7 RNAP | E. coli, Eukaryotes (with engineering) | ~5x native E. coli RNAP [12] | High specificity and processivity; vast established toolkit (e.g., pET systems); enables dynamic control & biosensing [12]. | Inefficient in many non-model organisms [4]; uncapped transcripts in eukaryotes limit utility [13]. |

| MmP1 RNAP | H. bluephagenesis, E. coli, P. entomophila [4] | Efficient transcription in non-model hosts [4] | High orthogonality; functions in non-model organisms like Halomonas; enables mutagenesis in new chassis [4]. | Lower baseline recognition in scientific community; toolkit less mature than T7. |

| K1F RNAP | H. bluephagenesis, E. coli, C. testosteroni [4] | Efficient transcription in non-model hosts [4] | Broad-host-range capability; high orthogonality; part of a modular system with other phage RNAPs [4]. | Similar to MmP1, requires further characterization and adoption. |

| VP4 RNAP | H. bluephagenesis, E. coli, P. putida [4] | Efficient transcription in non-model hosts [4] | Broad-host-range capability; high orthogonality; enables new application spaces for in vivo evolution [4]. | Similar to MmP1 and K1F. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics in Key Applications

| Application | Polymerase | Performance Metric | Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro mRNA Synthesis | T7RNAP (Wild Type) | mRNA Yield | 2-5 g L⁻¹ (standard); up to 12-14 g L⁻¹ (optimized) [14] | IVT reaction with optimized AT-rich downstream sequences [14]. |

| dsRNA Byproduct | Up to 30% reduction vs. wild-type promoter [14] | Using promoters with AT-rich insertions [14]. | ||

| In Vivo Mutagenesis | T7RNAP (MutaT7) | Mutation Frequency Increase | >80,000-fold vs. control [4] | C:G to T:A mutations in E. coli [4]. |

| MmP1 RNAP (pMT2-MmP1) | Mutation Frequency Increase | >80,000-fold vs. control [4] | C:G to T:A mutations in H. bluephagenesis; mutation rate of 2.9 x 10⁻⁵ s.p.b. [4]. | |

| Orthogonal Gene Expression in Eukaryotes | Evolved T7RNAP-Capping Enzyme Fusion | Protein Expression Increase | ~100x (two orders of magnitude) vs. wild-type T7RNAP [13] | Directed evolution in yeast; validated in mammalian cells [13]. |

The data reveal that T7RNAP remains unparalleled for applications in E. coli and cell-free systems, offering a combination of high yield, speed, and well-characterized behavior. Its use in cell-free protein synthesis can yield up to 2.3 mg/mL of a model protein like eGFP [12], and recent promoter engineering has pushed IVT mRNA yields to 14 g L⁻¹ [14]. However, a significant limitation of IVT with T7RNAP is the co-production of immunostimulatory double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) byproducts. Engineering efforts, including rational design of the polymerase and optimization of the promoter template, have successfully reduced these dsRNA levels by up to 30%, thereby improving the safety profile and purity of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics [12] [14].

For non-model organisms, the T7 system shows pronounced limitations. For example, in the industrially promising Halomonas bluephagenesis, T7RNAP failed to effectively transcribe genes downstream of its cognate promoter [4]. This critical shortcoming has driven the adoption of broader-host-range alternatives. The MmP1, K1F, and VP4 phage RNA polymerases have demonstrated high orthogonality and efficient transcription in Halomonas and Pseudomonas, effectively bypassing the host-range restriction of T7 [4]. When deployed for in vivo targeted mutagenesis, these systems achieved mutation frequencies more than 80,000-fold higher than controls, enabling rapid protein evolution in chassis previously intractable to such engineering [4].

In eukaryotic systems, the primary barrier for T7RNAP has been its inability to produce 5' methyl guanosine caps, which are essential for mRNA stability and translation. A groundbreaking solution involved fusing T7RNAP to a capping enzyme from the African swine fever virus and applying directed evolution in yeast. This engineered "Capping-T7" system resulted in variants exhibiting a 100-fold increase in protein expression compared to wild-type T7RNAP, finally enabling efficient, orthogonal, and programmable gene expression in both yeast and mammalian cells [13].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: In Vitro Transcription (IVT) for High-Yield mRNA Production

This protocol, adapted from recent optimizations, details the production of mRNA using T7RNAP with a focus on maximizing yield while minimizing immunostimulatory byproducts [14].

- Template DNA Preparation: A linear DNA template is required, containing the T7 promoter sequence immediately upstream of the mRNA sequence to be transcribed. The mRNA sequence should include the 5' untranslated region (UTR), the open reading frame (ORF) for the antigen or protein of interest, the 3' UTR, and a poly(A) tail sequence. The template can be generated via PCR amplification or by linearizing a plasmid vector.

- Reaction Mixture Assembly: The IVT reaction is assembled in a nuclease-free tube on ice. A standard reaction mixture includes:

- Template DNA: 5-10 μg of purified linear DNA template.

- Nucleoside Triphosphates (NTPs): A final concentration of 5-10 mM of each NTP (ATP, CTP, GTP, UTP).

- T7 RNA Polymerase: Commercially available or purified, used according to manufacturer's specifications.

- Reaction Buffer: A proprietary buffer typically supplied with the enzyme, often containing components like Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), MgCl₂, spermidine, and dithiothreitol (DTT).

- Incubation and mRNA Synthesis: The reaction mixture is incubated at 37°C for 45 minutes to 2 hours. Recent optimizations show that high yields of up to 12-14 g L⁻¹ can be achieved within 45 minutes to 2 hours using promoters with specific AT-rich downstream sequences [14].

- DNase Treatment: After incubation, 1-2 units of DNase I (RNase-free) are added to the reaction to digest the template DNA, and the mixture is incubated for an additional 15 minutes at 37°C.

- mRNA Purification: The mRNA is purified from the reaction mixture using methods such as lithium chloride precipitation or chromatographic purification to remove enzymes, proteins, and short abortive transcripts. Critical attention is paid to removing dsRNA contaminants, which can be achieved with specialized purification kits or cellulose-based purification.

dot code for In Vitro Transcription (IVT) for High-Yield mRNA Production:

IVT Workflow for mRNA Production

Protocol: Targeted In Vivo Mutagenesis Using an Orthogonal Transcription System

This protocol describes the use of deaminase-fused phage RNAPs, such as the MmP1-based system, for directed evolution in non-model bacteria like H. bluephagenesis [4].

- Mutator Plasmid Construction: A plasmid is constructed to express a fusion protein comprising a cytosine deaminase (e.g., PmCDA1), a uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI), and a phage RNA polymerase (e.g., MmP1 RNAP). The fusion protein is expressed from an inducible promoter (e.g., IPTG-inducible Ptac). The UGI is included to prevent the repair of U:G mismatches, thereby increasing mutation efficiency.

- Target Plasmid Construction: The gene of interest (GOI) to be evolved is cloned into a separate plasmid under the control of the cognate phage promoter (e.g., PMmP1).

- Strain Transformation and Culture: The host strain (e.g., H. bluephagenesis) is co-transformed with both the mutator and target plasmids. The transformed cells are grown in an appropriate medium. Once the culture reaches the desired optical density, mutagenesis is induced by adding a defined concentration of IPTG (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mM).

- Mutation and Screening/Selection: The culture is allowed to grow for a specified mutagenesis period (e.g., 24 hours). During this time, the mutator protein is expressed, binds to the target promoter, and transcribes the GOI. The associated deaminase domain introduces point mutations (C:G to T:A) into the single-stranded DNA of the non-transcribed strand during transcription. Following mutagenesis, the population is subjected to a screening or selection process to identify clones with desired, improved phenotypes.

- Isolation and Characterization: Plasmid DNA is isolated from the selected clones, and the mutated GOI is sequenced to identify the causative mutations. The target plasmid can then be retransformed into a fresh host to confirm that the phenotype is linked to the GOI.

dot code for Targeted In Vivo Mutagenesis Using an Orthogonal Transcription System:

In Vivo Mutagenesis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of orthogonal polymerase systems requires a suite of specialized reagents and genetic tools. The table below catalogues the essential components for designing and executing experiments with T7 and other phage polymerases.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Phage Polymerase Research

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Expression Systems | pET System (Chromosomal/plasmid-driven T7RNAP in E. coli) [12] | Provides controlled expression of T7RNAP for high-yield protein production. The classic system for recombinant expression. |

| Broad-Host-Range Mutator Plasmids (e.g., pSEVA241 with PmCDA1-UGI-MmP1) [4] | Enables targeted in vivo mutagenesis in non-model organisms like H. bluephagenesis and E. coli. | |

| Promoter & Template Variants | Wild-type T7 Promoter | The standard promoter sequence for initiating transcription with T7RNAP. |

| Engineered T7 Promoters (with AT-rich downstream insertions) [14] | Increase mRNA yields in IVT (up to 14 g L⁻¹) and reduce dsRNA byproduct formation by up to 30%. | |

| Orthologous Phage Promoters (PMmP1, PK1F, PVP4) [4] | Recognized by their respective orthogonal RNAPs (MmP1, K1F, VP4) for gene expression in broad hosts. | |

| Specialized Enzymes & Proteins | T7 RNA Polymerase (Wild-type and engineered variants) [12] [14] | The core catalyst for IVT and in vivo T7-based expression. Engineered variants reduce dsRNA byproducts. |

| Capping Enzyme-T7RNAP Fusion (Evolved variant) [13] | Enables efficient orthogonal gene expression in eukaryotic cells (yeast, mammalian) by producing capped mRNAs. | |

| Cytosine Deaminase-UGI-Phage RNAP Fusions (e.g., PmCDA1-UGI-MmP1) [4] | The core mutator protein for targeted in vivo evolution, introducing C:G to T:A transitions. | |

| Selection & Reporter Tools | Erythromycin Resistance Gene (ermC) with Inactivating Mutation [4] | A reporter gene for quantifying mutation frequency and efficiency in mutagenesis systems. |

| Fluorescent Proteins (sfGFP, EGFP) [14] [4] | Standard reporters for visualizing and quantifying gene expression and transcriptional activity. | |

| Critical Reaction Components | Nucleoside Triphosphates (NTPs), including modified NTPs (e.g., Pseudouridine) [12] | The building blocks for RNA synthesis. Modified NTPs are used to reduce immunogenicity of mRNA therapeutics. |

| In Vitro Transcription Buffer Systems | Provides optimal pH, ionic strength (Mg²⁺), and reducing agents (DTT) for T7RNAP activity. |

The landscape of orthogonal transcription systems has evolved from a single dominant platform, T7RNAP, into a rich ecosystem of complementary tools. T7RNAP continues to be the workhorse for applications within its effective host range, driven by continuous engineering that enhances its yield, fidelity, and controllability. The most significant advancements, however, lie in the expansion of this toolkit to overcome historical barriers. The development of broad-host-range phage polymerases like MmP1, K1F, and VP4 is a pivotal achievement, democratizing advanced synthetic biology techniques for non-model organisms with unique biotechnological value [4]. Simultaneously, the successful engineering of a T7-based system for eukaryotic orthogonality shatters a long-standing constraint, opening new avenues for therapeutic development and basic research in yeast and mammalian cells [13].

Future progress in this field will likely be driven by several key trends. The discovery and characterization of novel phage polymerases from environmental metagenomes will further expand the diversity of available systems. The engineering of polymerases with expanded substrate specificity to incorporate a wider range of non-canonical nucleotides will be crucial for advancing RNA therapeutics and creating new biomaterials. Furthermore, the integration of these orthogonal transcription engines with other powerful technologies, such as CRISPR-Cas for precise genome regulation, will continue to yield increasingly sophisticated and predictable genetic control systems [12]. As these tools become more refined, modular, and interconnected, they will profoundly accelerate the engineering of biological systems for drug discovery, sustainable manufacturing, and fundamental biological insight.

Predictable Operation, Low Basal Leakage, and High Inducibility

In the field of synthetic biology, the engineering of life is achieved through the rational design of genetic programs. A cornerstone of this endeavor is the development of orthogonal transcription factor systems, which are synthetic genetic controllers that operate independently of the host's native regulatory networks. The performance of these systems is critically evaluated based on key engineering metrics: predictable operation, which ensures consistent and reliable circuit performance; low basal leakage, which minimizes unintended gene expression in the absence of an inducer; and high inducibility, which provides a strong, clear signal upon activation. This guide objectively compares the performance of several advanced orthogonal systems, from bacterial sigma factors to mammalian synthetic receptors, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a data-driven framework for selecting the optimal system for their specific application, whether in bioproduction, therapeutic cell engineering, or fundamental biological research.

Performance Comparison of Orthogonal Systems

The quantitative performance of orthogonal systems varies significantly across different biological chassis and operational principles. The table below summarizes key performance data from recent studies to enable direct comparison.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Orthogonal Transcription Systems

| System Type | Organism | Key Inducer/Activator | Fold Induction (Dynamic Range) | Reported Basal Leakage | Key Performance Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal σ54 Factors [2] | E. coli | Bacterial Enhancer-Binding Proteins (bEBPs) | High (Precise data not given) | "Stringently regulated" and "strongly activated" | Excellent mutual orthogonality; transferable across bacterial species; AND-gate logic capability. |

| Small Molecule-Inducible Systems [15] | Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs) | 4OHT, ABA, GZV | Strong (Precise data not given) | "Minimal leakage" and "low background activation" | Titratable control; discrete (ON/OFF) or continuous response modes; functional in pluripotent stem cells. |

| TcpPH-EMeRALD Sensor [16] | E. coli | Taurocholic Acid (TCA) | 84.92-fold | Low (enabling high dynamic range) | High sensitivity (EC50: 28.344 μM); uses transmembrane sensor for extracellular cues. |

| NatE MESA Cytokine Receptors [17] | Mammalian T Cells | Cytokines (e.g., VEGF) | Varied by receptor design | "Low ligand-independent signal" in optimal designs | Orthogonal signaling; customizable for therapeutic sense-and-respond programs; can be multiplexed for logic. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Systems

Characterization of Small Molecule-Inducible Systems in mESCs

The protocol for characterizing the GAL4-UAS based inducible systems in mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (mESCs) provides a robust template for testing in mammalian cells [15].

- 1. Cell Line Engineering: A reporter mESC line (UAS-BFP mESCs) is first created by lentivirally transducing a cassette containing a 5x tandem GAL4 Upstream Activating Sequence (UAS) driving expression of mTagBFP2 (BFP). A constitutively expressed mCitrine enables sorting of successfully transduced cells.

- 2. Transduction with Transcription Factors: The reporter line is subsequently transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding the synthetic transcription factors. These factors consist of the GAL4 DNA-binding domain fused to a transactivation domain (VP16/VP64) and a regulatory domain (Ert2, ABI/Pyl, or NS3). A constitutive mCherry marker facilitates sorting of double-positive cells.

- 3. Induction and Flow Cytometry: Engineered cells are cultured for 3 days in the presence of titrated concentrations of the specific small-molecule inducers (4-Hydroxytamoxifen for Ert2, Abscisic Acid for ABI/Pyl, and Grazoprevir for NS3).

- 4. Data Analysis: Cells are analyzed by flow cytometry to quantify BFP fluorescence. Performance metrics, including dose-response curves, fold induction, and population distribution dynamics (discrete ON/OFF vs. continuous), are calculated from this data.

Establishing Orthogonality for Bacterial σ54 Systems

The methodology for validating the orthogonality of engineered σ54 factors in bacteria involves a systematic approach [2].

- 1. Strain Generation: An E. coli ΔrpoN knockout strain is constructed using λ-red homologous recombination to eliminate the native σ54 factor, providing a clean background.

- 2. Library Construction and Screening: Mutant libraries of rpoN (the gene encoding σ54) are generated, focusing on mutations at the R456 residue. These mutant σ54 factors are co-expressed with cognate promoter libraries carrying mutations in the -24 element.

- 3. Orthogonality Validation: The mutant σ54 factors and their partner promoters are tested in the ΔrpoN strain. Their ability to drive expression of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) is measured both individually and in combination to assess cross-talk.

- 4. Cross-Species Transfer: The functional orthogonal pairs are then cloned into broad-host-range plasmids and transformed into non-model bacteria (Klebsiella oxytoca, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Sinorhizobium meliloti) to demonstrate transferability.

- 5. Circuit Implementation: The orthogonal systems are integrated into more complex genetic circuits, such as layered logic gates or synthetic metabolic pathways (e.g., sucrose utilization), to test their performance under applied conditions.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core operational mechanisms of two major classes of orthogonal systems discussed in this guide.

Mammalian Inducible Transcription System

This diagram visualizes the mechanism of small molecule-inducible synthetic transcription factors in mammalian cells [15].

Bacterial Orthogonal σ54 System

This diagram depicts the unique, multi-component mechanism of orthogonal σ54-dependent transcription in bacteria [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful experiment relies on key, well-characterized reagents. The following table details essential tools and materials for working with the orthogonal systems described [15] [2] [16].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Orthogonal Transcription Systems

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Example or Source |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Promoter | A synthetic DNA sequence recognized specifically by an orthogonal transcription factor or polymerase, minimizing host crosstalk. | GAL4 Upstream Activating Sequence (UAS) [15]; Engineered σ54-dependent promoters [2] |

| Engineered Transcription Factor | The core protein component that binds the orthogonal promoter and activates transcription in a controlled manner. | GAL4-DBD fused to Ert2/ABI/Pyl/NS3 [15]; Mutant σ54 factors (e.g., R456H) [2] |

| Specific Inducer Molecules | Small molecules or proteins that trigger the activation of the orthogonal transcription system. | 4-Hydroxytamoxifen, Abscisic Acid, Grazoprevir [15]; Bacterial Enhancer-Binding Proteins (bEBPs) [2] |

| Reporter Genes | Genes with easily measurable outputs (e.g., fluorescence) used to quantify system performance. | mTagBFP2, sfGFP, mCherry [15] [16] |

| Delivery Vectors | Plasmids or viral vectors for stable and efficient delivery of genetic constructs into the target cell type. | Lentiviral vectors (mammalian cells) [15]; Broad-host-range plasmids (bacteria) [2] |

| Selection Markers | Genes that confer resistance to antibiotics or other selection pressures, enabling enrichment of successfully engineered cells. | Antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., Kanamycin, Ampicillin) [2] |

Bacterial enhancer-binding proteins (bEBPs) are a specialized class of AAA+ ATPases that function as transcriptional activators for genes dependent on the alternative sigma factor σ54 (also known as σN) [18]. Unlike the more common σ70-dependent transcription, σ54-dependent transcription exhibits a eukaryotic-like regulation mechanism where activator proteins are absolutely required for initiation [2] [18]. This dependency makes the σ54-bEBP partnership an attractive framework for engineering orthogonal genetic systems in synthetic biology [2] [10].

The σ54 factor itself recognizes distinct promoter sequences at the -12 (GG) and -24 (TGC) regions [18]. When bound to RNA polymerase (RNAP), σ54 forms a stable closed complex (RPc) that is transcriptionally inactive and cannot spontaneously isomerize to an open complex [18] [19]. This transition strictly requires the ATP-dependent remodeling activity of a bEBP, which interacts with the σ54-RNAP complex from binding sites typically located 100-150 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site [18] [19].

Structural and Mechanistic Basis of bEBP Function

Domain Architecture of bEBPs

bEBPs typically exhibit a conserved three-domain architecture:

- N-terminal regulatory domain (R): Often a receiver domain of a two-component system that senses environmental signals and regulates AAA+ domain activity.

- Central catalytic AAA+ domain (C): Responsible for ATP hydrolysis and mechano-chemical remodeling of the σ54-RNAP complex.

- C-terminal DNA binding domain (D): Contains a helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif that binds upstream activator sequences (UAS) [18].

These domains work cooperatively to ensure that transcription activation occurs only under appropriate environmental conditions sensed by the regulatory domain.

The AAA+ Domain and Conserved Motifs

The AAA+ domain of bEBPs belongs to the Helix-2-insert clade 6 of the AAA+ superfamily and contains several characteristic features [18]:

- Walker A and B motifs for nucleotide binding and hydrolysis

- Loop 1 (L1) containing the highly conserved GAFTGA motif essential for σ54 interaction

- Loop 2 (L2) that interacts with promoter DNA

The GAFTGA motif is particularly critical, as mutations in this sequence typically abolish transcription activation ability, either by impairing ATP hydrolysis, inter-subunit communication, or σ54 interaction [18].

Mechanism of Transcription Activation

Recent cryo-EM structures have captured snapshots of the conformational changes during σ54-mediated transcription initiation, revealing why bEBP activity is essential [18]. In the closed complex (RPc), σ54 regions I and III form a barrier that prevents DNA entry into the RNAP cleft [18].

bEBPs function as hexameric ring complexes that utilize ATP hydrolysis to remodel the σ54-RNAP complex through a mechanism involving:

- DNA looping facilitated by integration host factor (IHF), bringing distal bEBP binding sites proximal to the promoter

- Direct interaction between the bEBP AAA+ domain and σ54 region I

- Application of mechanical force via the GAFTGA-containing L1 loop to trigger σ54 conformational changes

- Promoter DNA melting and loading of the template strand into the RNAP active site

- Transition to open complex (RPo) competent for transcription initiation [18] [19]

This mechanism represents a sophisticated control system where transcription is tightly regulated at the isomerization step rather than RNAP binding, enabling stringent regulation and strong activation when environmental conditions dictate [2] [18].

bEBPs in Orthogonal Transcription System Engineering

Rationale for Orthogonality Engineering

The unique properties of σ54-dependent transcription make it particularly amenable to orthogonalization for synthetic biology applications. Key advantages include:

- Strict dependency on activator proteins prevents leaky expression

- Distinct promoter recognition patterns avoid crosstalk with host σ70 systems

- Strong activation potential enables high expression levels when required

- Natural stringency provides a framework for engineering predictable genetic circuits [2]

Orthogonal systems are defined by their ability to operate independently of host regulatory networks, enabling consistent and predictable performance of synthetic genetic circuits [2] [10].

Engineering Orthogonal σ54-bEBP Systems

Recent research has successfully engineered orthogonal σ54-bEBP systems through structure-guided rewiring of protein-DNA interaction interfaces. A key breakthrough involved modifying the RpoN box in σ54, which is responsible for recognizing the -24 promoter region [2] [10].

Liu et al. (2025) identified three orthogonal σ54 variants through knowledge-based screening and rational engineering:

Table 1: Orthogonal σ54 Variants and Their Properties

| σ54 Variant | Amino Acid Substitution | Promoter Preference | Orthogonality Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| σ54-R456H | Arginine → Histidine | Altered -24 recognition | Ideal mutual orthogonality |

| σ54-R456Y | Arginine → Tyrosine | Altered -24 recognition | Ideal mutual orthogonality |

| σ54-R456L | Arginine → Leucine | Altered -24 recognition | Ideal mutual orthogonality |

These engineered σ54 factors exhibit distinct promoter preferences while maintaining strong mutual orthogonality toward each other and the native σ54 system [2] [10]. The orthogonality was demonstrated to be transferable across multiple bacterial species, including Klebsiella oxytoca, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Sinorhizobium meliloti [2].

Applications in Genetic Circuit Design

The orthogonal σ54-bEBP systems have been successfully implemented in various synthetic biology applications:

- Layered logic gates with reduced crosstalk between circuit components

- Complex pathway orthogonalization to minimize metabolic burden and interference

- Environmental biosensing with customizable induction profiles

- Multi-input controllers for maintaining evolutionary longevity of synthetic circuits [2] [20]

When combined with different bEBPs, these orthogonal systems can control downstream outputs in response to environmental or chemical signals, enabling the construction of sophisticated genetic circuits with predictable computational performance [2].

Experimental Analysis of bEBP Systems

Key Experimental Methodologies

Research on bEBP structure and function employs several advanced techniques:

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods in bEBP Research

| Methodology | Application in bEBP Research | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|

| Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) | Structural analysis of σ54-RNAP complexes at different activation states | Revealed conformational changes during closed-to-open complex transition [18] |

| High-throughput transcriptomics (HTTr) | Assessment of transcriptional activation potency and specificity | Enabled quantification of orthogonal system performance and detection of crosstalk [21] [22] |

| Genetic circuit characterization | Testing orthogonality and circuit performance in live cells | Demonstrated transferability of orthogonal systems across bacterial species [2] |

| Computational modeling & host-aware design | Predicting evolutionary longevity of synthetic circuits | Informed controller design to maintain circuit function despite mutation [20] |

Protocol for Orthogonal System Characterization

A standard protocol for assessing orthogonal σ54-bEBP system performance includes:

- Host strain preparation: Creation of ΔrpoN strains using λ-red homologous recombination to eliminate native σ54 background [2]

- Plasmid construction: Assembly of expression cassettes using Golden Gate assembly with orthogonal σ54 variants and cognate promoters

- Cross-activation testing: Transformation of σ54 variants with different promoter-reporter constructs to assess specificity

- Transcriptional output quantification: Measurement of reporter gene expression (e.g., GFP/RFP) under induced vs. uninduced conditions

- Orthogonality index calculation: Determination of activation specificity relative to non-cognate promoter pairs

- Host transfer validation: Testing orthogonal system performance in multiple non-model bacterial species [2]

This systematic approach enables comprehensive characterization of orthogonal system performance while identifying potential crosstalk between engineered components.

Comparative Performance of Orthogonal Systems

Quantitative Assessment of Orthogonal σ54 Variants

The performance of engineered orthogonal σ54-bEBP systems can be quantitatively evaluated across multiple metrics:

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Orthogonal σ54-bEBP Systems

| Performance Metric | σ54-R456H | σ54-R456Y | σ54-R456L | Native σ54 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Fold-Change | High (comparable to native) | High (comparable to native) | Moderate to High | Reference level |

| Basal Expression | Low (stringent control) | Low (stringent control) | Low (stringent control) | Low (stringent control) |

| Promoter Specificity | High (altered -24 preference) | High (altered -24 preference) | High (altered -24 preference) | Native preference |

| Cross-talk with Native System | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | N/A |

| Transferability Across Species | Demonstrated in 3 species | Tested in model systems | Tested in model systems | Species-dependent |

Advantages Over Alternative Orthogonal Systems

Compared to other orthogonal transcription systems like T7 RNA polymerase, σ54-bEBP systems offer distinct advantages:

- Lower cellular toxicity due to endogenous bacterial machinery

- Higher adjustability through bEBP regulation

- Natural stress response integration via bEBP sensing domains

- Flexible input control through diverse bEBP regulatory mechanisms [2]

However, potential limitations include the energy cost of AAA+ ATPase activity and the structural complexity of the multi-component activation mechanism.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Essential research tools for studying bEBPs and engineering orthogonal systems include:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for bEBP Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | E. coli ΔrpoN strains; Klebsiella oxytoca; Pseudomonas fluorescens; Sinorhizobium meliloti | Host organisms for orthogonal system testing and characterization [2] |

| Expression Vectors | pBBR-derived broad-host-range vectors; Golden Gate compatible plasmids | Genetic cargo delivery and modular circuit assembly [2] |

| Reporter Systems | GFP; RFP; metabolic markers (e.g., sucrose utilization cassettes) | Quantitative assessment of transcriptional activity and orthogonality [2] |

| bEBP Expression Constructs | NtrC; FleT; LasR; EsaR; engineered bEBP variants | Sources of activation function for σ54-dependent transcription [18] [23] |

| Promoter Libraries | Native σ54 promoters; engineered -24 variant promoters | Testing recognition specificity and orthogonal system performance [2] |

| Analytical Tools | Cryo-EM; HTTr; RNA-seq; growth rate assays | System characterization and mechanistic studies [18] [21] [22] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

bEBP Activation Mechanism

Orthogonal System Engineering Workflow

Future Directions and Applications

The engineering of orthogonal bEBP systems continues to evolve with several promising research directions:

- Expanded orthogonal sets through comprehensive mutagenesis of σ54-DNA interface

- Integration with CRISPR technologies for multi-layer genetic control

- Evolutionary stabilization of synthetic circuits using host-aware controller designs [20]

- Clinical and biotechnological applications in smart therapeutics and biosensing

- Cross-kingdom compatibility for broad-host-range genetic toolkits

The unique combination of stringency, strong activation potential, and engineerability positions σ54-bEBP systems as foundational tools for next-generation synthetic biology applications requiring precise transcriptional control.

Design, Assembly, and Functional Deployment in Synthetic Biology

The precise rewiring of protein-DNA interactions represents a frontier in synthetic biology, enabling the programming of custom gene regulatory networks for therapeutic and biotechnological applications. Central to this endeavor are orthogonal transcription systems—engineered biological components that function independently of the host's native machinery. These systems provide a powerful platform for directed evolution, allowing researchers to rapidly optimize protein-DNA binding specificities and affinities. The core principle involves creating a synthetic replication or transcription apparatus that operates in parallel to the cell's natural systems, facilitating targeted mutagenesis and selection without compromising host cell viability [24]. This approach has dramatically accelerated our ability to engineer novel transcription factors, DNA-binding proteins, and regulatory circuits with precision.

The emergence of tools like T7-ORACLE and the Orthogonal Transcription Mutation (OTM) system has transformed the protein engineering landscape. These systems address critical limitations of traditional directed evolution methods, which often involve laborious cycles of mutagenesis and screening. By harnessing error-prone viral polymerases and fusing them with deaminase enzymes, these platforms enable continuous hyper-mutation of target genes inside living cells, compressing evolutionary timelines from months to days while generating diverse mutational landscapes [24] [4]. This review comprehensively compares these pioneering technologies, their experimental performance, and their application in rewiring protein-DNA interactions for advanced research and therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of Orthogonal Mutagenesis Systems

The table below provides a systematic comparison of two leading orthogonal systems for evolving protein-DNA interactions, highlighting their distinct mechanisms and performance characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Orthogonal Systems for Rewiring Protein-DNA Interactions

| Feature | T7-ORACLE System | Orthogonal Transcription Mutation (OTM) System |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Orthogonal T7 replisome with error-prone DNA polymerase in E. coli [24] | Deaminase-phage RNA polymerase fusion proteins [4] |

| Mutation Types | Broad spectrum (unspecified) | Transition mutations: C:G to T:A and A:T to G:C [4] |

| Mutation Rate Increase | 100,000-fold above natural mutation rate [24] | >1,500,000-fold above natural mutation rate [4] |

| Evolution Timeframe | Days (versus months for traditional methods) [24] | Single day (shortest reported period) [4] |

| Host Organisms | Escherichia coli [24] | E. coli and non-model organisms (e.g., Halomonas bluephagenesis) [4] |

| Key Innovation | Continuous hypermutation without host genome damage [24] | Modular design with three different phage RNAPs (MmP1, K1F, VP4) [4] |

| Specificity | Targets only plasmid DNA, host genome untouched [24] | High specificity with minimal off-target effects (5-14 fold increase vs. 154-fold with suboptimal construct) [4] |

Experimental Protocols for System Validation

T7-ORACLE Workflow and Validation

The T7-ORACLE system employs a meticulously engineered experimental workflow to achieve accelerated evolution of target proteins:

- Step 1: System Construction – An artificial DNA replication system derived from bacteriophage T7 is engineered into E. coli host cells. The key component is an error-prone T7 DNA polymerase that replicates only specific plasmid DNA, leaving the host genome intact [24].

- Step 2: Target Gene Cloning – The gene of interest (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene, transcription factor, or enzyme) is cloned into a special plasmid containing the T7 origin of replication, making it susceptible to the error-prone polymerase [24].

- Step 3: Continuous Evolution – The bacterial culture is propagated under standard laboratory conditions. With each cell division (approximately every 20 minutes), the target gene undergoes replication by the error-prone polymerase, introducing random mutations. This creates a continuously evolving gene library inside the cells [24].

- Step 4: Selection and Screening – Cells are subjected to selective pressure relevant to the desired protein function. In the validation experiment, cells harboring the TEM-1 β-lactamase gene were exposed to escalating doses of antibiotics. Variants with mutations conferring enhanced resistance survived and proliferated [24].

- Step 5: Outcome Analysis – In the validation study, this process yielded enzyme variants capable of resisting antibiotic levels 5,000 times higher than the original within one week. The identified mutations closely mirrored those found in clinical antibiotic resistance, confirming the system's biological relevance [24].

OTM System Workflow and Validation

The Orthogonal Transcription Mutation system utilizes a different mechanism based on transcriptional mutagenesis, with a protocol adaptable to multiple organisms:

- Step 1: Mutator Plasmid Construction – Plasmids are constructed to express fusion proteins. These fusions combine a deaminase enzyme (e.g., PmCDA1 for C→T mutations) with an orthogonal phage RNA polymerase (MmP1, K1F, or VP4) via a flexible XTEN linker [4].

- Step 2: Target Plasmid Design – The gene to be evolved is placed under the control of a promoter specific to the chosen phage RNA polymerase (e.g., PMmP1 for MmP1 RNAP) on a separate plasmid [4].

- Step 3: In Vivo Mutagenesis – Both plasmids are co-transformed into the host organism (E. coli or H. bluephagenesis). Upon induction, the fusion protein is expressed. It then transcribes the target gene and simultaneously introduces mutations into the nascent DNA transcript. Co-expression of uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) is critical for enhancing C→T mutation efficiency by preventing repair mechanisms [4].

- Step 4: Functional Screening – The population of mutated cells is screened for desired phenotypes. The OTM system was validated by evolving fluorescent proteins, chromoproteins, and a dysfunctional erythromycin resistance gene (ErmC Y104S). A C-to-T reversion mutation at a specific site successfully restored antibiotic resistance, demonstrating the system's precision and effectiveness [4].

- Step 5: Efficiency Quantification – Mutation frequency and rates are calculated using a mutation-recovery method. The most efficient OTM construct (PmCDA1-UGI-MmP1) achieved an on-target mutation frequency of 2.5 × 10⁻², over 80,000 times higher than the control, with a calculated mutation rate of 2.9 × 10⁻⁵ substitutions per base [4].

Supporting Tools: Computational Prediction of Protein-DNA Interactions

Complementing experimental evolution, computational tools are vital for predicting and analyzing rewired protein-DNA interactions. The Interpretable protein-DNA Energy Associative (IDEA) model is a notable biophysical tool that predicts DNA recognition sites and binding affinities for DNA-binding proteins like transcription factors [25].

- Principle: IDEA integrates 3D structures and sequences of known protein-DNA complexes to learn an interpretable energy model. This model quantifies the physicochemical interactions between individual amino acids and nucleotides, effectively deciphering the "molecular grammar" of binding specificity [25].

- Application: In one benchmark, the IDEA model, using only the structure of the MAX transcription factor (PDB ID: 1HLO), achieved a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.67 with experimentally measured binding affinities. Performance improved further when integrated with experimental SELEX data, providing a powerful hybrid approach for guiding and interpreting mutagenesis results [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of orthogonal evolution systems requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components for establishing these platforms in a research setting.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Orthogonal Evolution Studies

| Reagent/Tool Name | Function in Experimental Workflow | Example Application/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone T7 DNA Polymerase | Drives continuous mutagenesis of target plasmid in T7-ORACLE [24] | Engineered variant with high error rate; core of the orthogonal replisome. |

| Deaminase-Phage RNAP Fusion | Introduces transition mutations during transcription in OTM [4] | e.g., PmCDA1-UGI-MmP1; modular for different mutation types and hosts. |

| Orthogonal Origin of Replication | Confines mutagenesis to target plasmid, sparing host genome [24] | Derived from bacteriophage (e.g., T7 origin). |

| Uracil Glycosylase Inhibitor (UGI) | Enhances C→T mutation yield by blocking DNA repair [4] | Co-expressed with cytosine deaminase fusions. |

| IDEA Model | Computationally predicts binding sites & affinities of DNA-binding proteins [25] | Provides interpretable, residue-level energy predictions. |

| Reporter Plasmids | Carry selectable or screenable markers for functional selection [24] [4] | e.g., TEM-1 β-lactamase (antibiotic resistance) or sfGFP (fluorescence). |

The direct comparison of T7-ORACLE and the Orthogonal Transcription Mutation system reveals a dynamic and rapidly advancing field. T7-ORACLE excels with its very high mutation rate and operation in the widely adopted E. coli chassis, making it a robust tool for broad protein engineering projects. In contrast, the OTM system offers unparalleled speed and modularity, with the distinct advantage of functioning in non-model organisms, thus expanding the scope of synthetic biology applications.

The integration of these advanced experimental evolution platforms with powerful computational predictors like the IDEA model creates a powerful feedback loop. Researchers can not only rapidly generate novel protein-DNA interfaces but also understand the biophysical principles governing their interactions. This synergy between laboratory evolution and computational design is fundamentally advancing our capacity to rewire biological systems, paving the way for breakthroughs in gene therapy, drug development, and cellular engineering.

Library Construction and High-Throughput Screening for Orthogonal Pairs

The engineering of biological systems requires genetic components that operate predictably and independently from the host's native regulatory networks. This principle, known as orthogonality, ensures that synthetic genetic circuits perform their intended functions without undesired crosstalk or interference. Orthogonal transcription systems, particularly those based on transcription factors and RNA polymerases, have become indispensable tools for programming cells with sophisticated capabilities. These systems enable controlled gene expression, pathway optimization, and the development of complex genetic circuits for therapeutic and industrial applications.

This guide provides a comparative evaluation of contemporary platforms for constructing orthogonal genetic systems and conducting high-throughput screening. We examine three pioneering approaches that demonstrate how strategic design of protein-DNA interactions, phage RNA polymerase engineering, and innovative selection mechanisms can overcome historical limitations in predictability, efficiency, and scalability. For each platform, we present quantitative performance data, detailed experimental protocols, and practical implementation guidelines to assist researchers in selecting the most appropriate technology for their specific applications.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Orthogonal Systems

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Orthogonal Systems

| Platform | Orthogonality Mechanism | Mutation Rate/ Efficiency | Key Applications | Host Organisms | Throughput Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal σ54 System | Engineered σ54-R456 mutations with modified promoter specificity | N/A (Transcriptional control) | Genetic circuit orthogonalization, metabolic engineering | E. coli, K. oxytoca, P. fluorescens, S. meliloti | Moderate (Library screening) |

| Orthogonal Transcription Mutator (OTM) | Deaminase-phage RNAP fusions generating transition mutations | >1,500,000-fold increase vs control; 2.9 × 10⁻⁵ substitutions per base [4] | Protein evolution, metabolic engineering | E. coli, H. bluephagenesis | High (>10¹¹ variants) |

| PANCS-Binders | Split RNA polymerase reconstitution upon target binding | 10⁶-fold amplification for high-affinity binders; 10¹⁵-fold relative enrichment [26] | Binder discovery, protein-protein interaction engineering | E. coli (with mammalian cell validation) | Very High (>10¹¹ protein-protein pairs) |

Table 2: Specificity and Selectivity Metrics

| Platform | On-target Efficiency | Off-target Effects | Orthogonality Between Components | Binding Affinity Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal σ54 System | Ideal mutual orthogonality between σ54-R456H, R456Y, R456L variants [2] | Minimal basal leakage due to bEBP requirement [2] | High (transferable across species) | N/A (Transcriptional tool) |

| pMT2-MmP1 Mutator | 80,000-fold increase over control; 7.4 × 10⁻⁴ mutation frequency [4] | 5-14 fold increase vs control (high specificity) [4] | High orthogonality between phage polymerases | N/A (Mutation generation) |

| PANCS-Binders | 55-72% hit rate for novel binders across 95 targets [26] | High-fidelity selection with low false positives | Specific phage-target pairing | 206 pM - 8.4 nM (after maturation) [26] |

Orthogonal σ54-Dependent Transcription System

The σ54-dependent orthogonal transcription system represents a novel approach to decoupling synthetic genetic circuits from native host regulation. Unlike the major σ70 factor in bacteria, σ54 recognizes distinct promoter sequences and requires activation by bacterial enhancer-binding proteins (bEBPs), providing an additional layer of regulatory control [2]. This dependency creates a stringent OFF state with minimal basal leakage, making it particularly valuable for applications requiring precise temporal control. Researchers engineered this system through knowledge-based screening and rewiring of the RpoN box in σ54, identifying three key mutations (R456H, R456Y, and R456L) that exhibit ideal mutual orthogonality and distinct promoter preferences while maintaining compatibility with native bEBP activation mechanisms [2].

Experimental Protocol

Library Construction Method:

- Strain Preparation: Generate ΔrpoN E. coli JM109 strain using λ-red homologous recombination with Gm-resistant gene flanked by 60 bp homologous arms [2].

- σ54 Mutant Library: Create random mutation libraries for rpoN R456/R457 sites using inverse PCR with plasmids carrying σ54 sequences as templates.

- Promoter Engineering: Introduce random mutations in the −24 elements of σ54-dependent promoters via inverse PCR.

- Vector Assembly: Assemble expression cassettes using Golden Gate assembly with BpiI and BsaI restriction sites.

- Host Transfer: Clone orthogonal systems into pBBR-derived broad-host-range vectors for testing in non-model bacteria (K. oxytoca, P. fluorescens, S. meliloti).

Screening Protocol:

- Primary Screening: Transform σ54 mutant library into ΔrpoN strain with GFP reporter under wild-type or modified σ54 promoters.

- Orthogonality Assessment: Co-transform different σ54 mutant-promoter pairs to assess cross-activation using fluorescent reporters (GFP/RFP).

- bEBP Integration: Co-express different bEBPs (KoNifA, RcNifA) under Ptet promoter to test activation specificity.

- Quantification: Measure fluorescence intensity via flow cytometry to calculate orthogonality coefficients and activation folds.

Key Research Reagents:

- Bacterial Strains: E. coli JM109, ΔrpoN strains, K. oxytoca, P. fluorescens, S. meliloti

- Vectors: pSEVA derivatives, pBBR-derived broad-host-range vectors

- Promoters: σ54-dependent native and engineered promoters

- Induction Systems: Ptet-regulated bEBP expression

- Reporters: GFP, RFP, sucrose utilization genes (cscA, cscB, cscK)

Orthogonal Transcription Mutation (OTM) System

The Orthogonal Transcription Mutation system represents a breakthrough in targeted in vivo mutagenesis by fusing deaminase enzymes with phage RNA polymerases to create hypermutation machinery. This platform addresses critical limitations of previous targeted evolution methods by achieving unprecedented mutation rates—over 1,500,000-fold increases compared to controls—while maintaining high specificity and minimal off-target effects [4]. The system employs three different phage RNA polymerases (MmP1, K1F, and VP4) that demonstrate high orthogonality, enabling simultaneous evolution of multiple genetic targets without cross-talk. Unlike traditional methods limited to model organisms, OTM functions effectively in non-model systems like Halomonas bluephagenesis, expanding directed evolution capabilities to industrially relevant chassis [4].

The mechanism involves fusion of cytosine deaminase (PmCDA1) or adenine deaminase (TadA8e) domains to phage RNAPs, creating mutator enzymes that introduce C:G to T:A and A:T to G:C transitions across target genes. When the deaminase-RNAP fusion binds to its specific promoter sequence, it locally unwinds DNA and exposes single-stranded regions for deamination, creating uracil or inosine bases that are processed into permanent transition mutations during subsequent replication cycles. The inclusion of uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) domains significantly enhances mutation efficiency by preventing repair of uracil lesions [4].

Experimental Protocol

Mutator Library Construction:

- Plasmid Design: Clone PmCDA1 variants (PmCDA1, PmCDA1-UGI, evoPmCDA1-UGI) fused to N-terminus of MmP1, K1F, or VP4 RNAPs via XTEN linkers in high-copy-number pSEVA241 vector.

- Expression Control: Drive fusion expression with IPTG-inducible tac promoter (PTac).

- Target Plasmid Engineering: Clone sfGFP or inactivated ermC (Y104S mutation) under specific phage promoters (PMmP1, PK1F, PVP4) in pSEVA321 backbone.

Mutation Efficiency Assessment:

- Transcriptional Activity Verification: Transform mutator plasmids into H. bluephagenesis with sfGFP target plasmid, measure fluorescence intensity by flow cytometry.

- On-target Mutation Frequency: Use erythromycin resistance restoration assay with ErmC Y104S mutant, calculate mutation frequency as (EryR colonies)/(total colonies).

- Off-target Rate Evaluation: Measure rifampicin-resistant mutation frequency in genomic RNA polymerase beta subunit gene.

- Optimization: Titrate IPTG inducer concentration (0-1 mM) to balance mutation efficiency and cell viability.

High-Throughput Screening:

- Continuous Evolution: Co-culture cells containing mutator and target plasmids with appropriate antibiotic selection.

- Variant Isolation: Plate aliquots at time intervals on selective media to isolate functional mutants.

- Characterization: Sequence resistant colonies to identify mutation spectra and calculate mutation rates using maximum likelihood method.

Key Research Reagents:

- Phage RNA Polymerases: MmP1, K1F, VP4 RNAPs with cognate promoters

- Deaminase Enzymes: PmCDA1, evoPmCDA1, TadA8e

- Inhibitor Protein: Uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI)

- Vectors: pSEVA241 (high-copy), pSEVA321 (target)

- Selection Markers: Erythromycin resistance (ermC), rifampicin resistance (rpoB)

- Reporters: sfGFP, chromoproteins

PANCS-Binders Discovery Platform

PANCS-Binders (Phage-Assisted Noncontinuous Selection of Protein Binders) revolutionizes high-throughput binder discovery by linking the M13 phage life cycle to target protein binding through proximity-dependent split RNA polymerase biosensors. This platform enables comprehensive screening of protein-protein interaction pairs with unprecedented speed and scale—assessing over 10¹¹ variants against 95 separate targets in just two days [26]. The system achieves remarkable sensitivity, distinguishing binders with affinities as low as 206 pM and demonstrating 10¹⁵-fold relative enrichment for high-affinity interactions. By overcoming the sampling limitations of continuous evolution systems, PANCS-Binders successfully identifies de novo binders from extremely diverse libraries where active variants may be present at ratios below 1:10⁷ [26].

The molecular mechanism relies on engineered M13 phage encoding protein variant libraries tagged with one half of a split RNA polymerase (RNAPN). Host E. coli cells express the target protein of interest fused to the complementary RNAP fragment (RNAPC). When a phage-encoded protein variant binds to the target, the split RNAP reconstitutes and triggers expression of a required phage gene, allowing selective replication of binding clones. This direct coupling between binding and phage propagation creates a powerful selective pressure that efficiently enriches functional binders while eliminating non-functional variants from the population [26].

Experimental Protocol

Library and Strain Preparation:

- Phage Library Construction: Clone RNAPN-tagged protein variant libraries (affibodies, DARPins, etc.) into replication-deficient M13 phage vector. Achieve diversity of 10⁸-10¹⁰ unique variants.

- Selection Strain Engineering: Transform E. coli with plasmid expressing target protein fused to RNAPC under inducible promoter.

- Optimization: Validate split RNAP reconstitution efficiency with positive control binders.

PANCS Selection Protocol:

- Initial Infection: Mix phage library (10¹⁰-10¹¹ pfu) with selection cells (OD₆₀₀ ~0.5) at appropriate cell:phage ratio (optimized at 10:1).

- Primary Incubation: Incubate phage-cell mixture for 12 hours with shaking at 37°C to allow complete infection and binding-dependent replication.

- Serial Passaging: Transfer 5% of phage supernatant to fresh selection cells every 12 hours for 4-6 passages.

- Monitoring: Titer phage from each passage to track enrichment dynamics.

- Stringency Control: Adjust selection stringency using arabinose-inducible promoter strength for essential phage gene.

Hit Characterization:

- Phage Sequencing: Isolate individual phage clones from final passage, sequence variant regions.

- Affinity Measurement: Express and purify soluble binders, determine binding kinetics (K_D) via surface plasmon resonance or bio-layer interferometry.

- Functional Validation: Test binders in mammalian cells for target inhibition (Mdm2-p53) or degradation (KRAS-LC3B pathway).

Affinity Maturation:

- Secondary Library: Generate mutagenized library around initial hit sequences.

- Iterative PANCS: Perform additional selection rounds with increased stringency.

- Characterization: Identify matured binders with improved affinity (8.4 nM demonstrated from 200 nM starting binder) [26].

Key Research Reagents:

- Phage System: M13 phage derivatives, replication-deficient variants

- Split RNAP: RNAPN and RNAPC fragments with optimized split sites

- Selection Cells: E. coli with arabinose-inducible essential phage gene

- Protein Libraries: Affibody, DARPin, or other scaffold libraries

- Target Proteins: Diverse panel of 95 proteins for multiplex screening

- Mammalian Validation: HEK293T cells, degradation tag systems (LIR motifs)

Comparative Applications and Implementation Guidelines

System Selection Framework

Table 3: Application-Specific Platform Recommendations

| Research Goal | Recommended Platform | Implementation Timeline | Key Advantages | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Circuit Orthogonalization | σ54 Transcription System | 2-3 weeks | Low basal leakage, bEBP regulation, transferable across species [2] | Requires bEBP co-expression, moderate throughput |

| Rapid Protein Evolution | Orthogonal Transcription Mutator | 1-2 days | Extreme mutation rates, broad host compatibility, uniform mutation distribution [4] | Limited to transition mutations, optimization needed for each host |