Optimizing DNA Assembly: Strategies for High-Efficiency, High-Fidelity Large Constructs

The synthesis of large DNA constructs is a cornerstone of synthetic biology and therapeutic development, yet achieving high efficiency and fidelity remains a significant challenge.

Optimizing DNA Assembly: Strategies for High-Efficiency, High-Fidelity Large Constructs

Abstract

The synthesis of large DNA constructs is a cornerstone of synthetic biology and therapeutic development, yet achieving high efficiency and fidelity remains a significant challenge. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern DNA assembly strategies tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We first explore the foundational limitations of traditional cloning and the pressing need for decentralized, cost-effective workflows. The review then details advanced methodological frameworks, including data-optimized design and enzymatic assembly techniques like Golden Gate and Gibson Assembly, which enable the successful construction of complex sequences, even those with high GC content or repeats. A dedicated troubleshooting section offers actionable protocols for optimizing fragment ratios, purification, and transformation to maximize success rates. Finally, we present a comparative validation of current technologies, assessing scalability and error rates to guide method selection. This synthesis of foundational principles, application protocols, and optimization benchmarks provides a definitive guide for accelerating the design-build-test cycle in genetic engineering and biopharmaceutical research.

The DNA Assembly Bottleneck: Understanding Challenges with Large Constructs

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

What are the primary limitations of traditional restriction enzyme cloning?

Traditional restriction enzyme cloning, specifically using Type IIP enzymes, faces two major limitations that hinder efficiency and precision in DNA assembly for large constructs [1].

- Restriction Site Dependency: The method requires unique, non-overlapping restriction sites that are absent from the DNA sequence of interest. For longer DNA sequences, avoiding internal restriction sites becomes increasingly difficult, complicating experimental design [1].

- Introduction of Scar Sequences: The recognition sites of the restriction enzymes are retained in the final construct. This leaves behind extra, unwanted base pairs (scars) at the junctions of the cloned fragments. These scars can disrupt open reading frames if they occur within coding sequences, leading to frameshift mutations or the introduction of unintended amino acids [1] [2].

How do 'scar sequences' impact downstream research applications?

Scar sequences, the unwanted nucleotides left at DNA junctions, can have several negative consequences [1]:

- Disruption of Coding Sequences: In coding regions, scar sequences can alter the reading frame or add unintended amino acids, potentially compromising protein function and fidelity.

- Interference with Regulatory Elements: In promoters or other regulatory regions, these extra nucleotides can affect the binding of transcription factors and other proteins, leading to unpredictable gene expression levels.

- Reduced Predictability: The presence of scars makes the DNA sequence less predictable and can complicate the rational design of subsequent genetic constructs, a significant drawback in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering.

What troubleshooting steps can I take if my restriction digestion is incomplete?

Incomplete digestion is a common cause of cloning failure. The table below summarizes potential causes and solutions [3] [4] [5].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or No Digestion | Contaminants in DNA preparation (e.g., salts, phenol, EDTA) inhibiting the enzyme | Purify DNA using column purification, spin columns, or ethanol precipitation [4] [5]. |

| DNA methylation blocking the restriction site | Use a restriction enzyme insensitive to methylation or use competent cells from a DNA methyltransferase-free E. coli strain [4] [5]. | |

| Suboptimal reaction conditions (buffer, temperature, time) | Follow the manufacturer's recommended buffer and incubation temperature; increase incubation time or amount of enzyme used [3] [5]. | |

| PCR product design lacking necessary flanking bases | Ensure PCR primers add extra nucleotides (a "leader" sequence) on the 5' side of the restriction site for efficient enzyme binding and cleavage [5]. |

Why am I getting no colonies or too few colonies after transformation?

A lack of transformed colonies indicates a failure at one or more steps in the cloning workflow. Key areas to investigate are listed below [3] [4].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Colonies / Few Colonies | Low transformation efficiency of competent cells | Check cell competency with a known supercoiled plasmid (e.g., pUC19); use commercial high-efficiency competent cells [3] [4]. |

| Toxic DNA insert for the host E. coli strain | Use a low-copy-number plasmid, a tightly regulated inducible promoter, or a specialized host strain (e.g., Stbl2 for repeats); grow at lower temperature (25-30°C) [3] [4]. | |

| Inefficient ligation | Verify T4 DNA ligase activity; optimize vector-to-insert molar ratio (from 1:1 to 1:10); use fresh ATP-containing ligation buffer; ensure insert has 5' phosphate groups [4]. | |

| Large construct size | For inserts >5 kb, use electroporation instead of chemical transformation and select competent cells validated for large plasmids [3] [4]. |

How can I reduce background colonies containing empty vectors?

High background, where many colonies contain the vector without the desired insert, is often due to vector self-ligation [5].

- Cause: Incomplete digestion of the vector or recircularization of a single-vector fragment during ligation.

- Solutions:

- Dephosphorylate the Vector: Treat the digested vector with an alkaline phosphatase (e.g., CIP, SAP, or rSAP) to remove 5' phosphate groups, preventing DNA ligase from re-circularizing it [3] [5].

- Ensure Complete Digestion: Gel-purify the digested vector to separate it from any uncut vector before proceeding to ligation [3].

- Use Controls: Perform a control ligation with the digested and dephosphorylated vector alone. This should yield very few colonies, confirming the dephosphorylation was effective [4].

Modern Solutions: Moving Beyond Traditional Limitations

What are the key advantages of Golden Gate assembly?

Golden Gate assembly is a scarless cloning method that overcomes the major limitations of traditional cloning by using Type IIS restriction enzymes [1] [6].

- Scarless Cloning: Type IIS enzymes cut outside their recognition sites, allowing for the design of fragments that, when ligated, fuse together without any extra nucleotides (scars), creating a seamless junction [1].

- Multi-Fragment Assembly: This method allows for the simultaneous, ordered assembly of many DNA fragments in a single reaction, with reports of successfully assembling up to 52 fragments [1].

- High Efficiency: The simultaneous digestion and ligation in one tube drives the reaction toward the final product, as the assembled product lacks the restriction sites and is no longer a substrate for digestion. This results in high efficiency and reduced hands-on time [1] [6].

The diagram below contrasts the workflows and outcomes of traditional restriction cloning and Golden Gate assembly.

How does Golden Gate assembly achieve scarless, multi-fragment cloning?

Golden Gate assembly utilizes Type IIS restriction enzymes, which have the unique property of cleaving DNA at a defined distance outside of their asymmetric recognition sequence [1] [6]. This allows researchers to design custom overhangs. In a single-tube reaction, the Type IIS enzyme excises the fragments from their vectors, generating the desired overhangs, and T4 DNA ligase then joins these complementary overhangs. Because the recognition sites are external to the cleaved overhangs, they are absent from the final, assembled construct, making the process scarless and preventing re-digestion [1].

What quantitative improvements does Golden Gate offer?

The performance advantages of modern assembly methods like Golden Gate are significant, especially for complex constructs [1] [6].

| Performance Metric | Traditional Restriction Cloning | Golden Gate Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Seamlessness | Scarred (adds extra nucleotides) | Scarless (no extra nucleotides) |

| Typical Fragment Number | Low (often 1-2) | High (up to 52 reported) |

| Cloning Efficiency (for 5+ fragments) | Very Low | >50% |

| Single-Fragment Cloning Efficiency | Variable | >97% (with 5-min reaction) |

| Reaction Incubation Time | Several hours/overnight | 5 minutes to several hours |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and their functions for troubleshooting traditional cloning and implementing modern assembly methods [1] [3] [4].

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Type IIP Restriction Enzymes | Traditional cloning (e.g., EcoRI, BamHI). Cleave within palindromic recognition sites, leaving scars [1]. |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | Golden Gate assembly (e.g., BsaI, BbsI, AarI). Cleave outside recognition sites for scarless cloning [1] [6]. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments by catalyzing phosphodiester bond formation between adjacent 5' phosphate and 3' hydroxyl ends [5]. |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | Removes 5' phosphate groups from vectors to prevent self-ligation, reducing background colonies [3] [5]. |

| High-Efficiency Competent Cells | Essential for transformation, especially for large constructs (>5 kb) or to avoid recombination (use recA- strains) [3] [4]. |

| T4 Polynucleotide Kinase | Adds 5' phosphate groups to DNA fragments (e.g., synthetic oligonucleotides) required for ligation [4]. |

| Gel Extraction Kits | Purify correctly digested vector and insert fragments from agarose gels, removing enzymes and contaminants [3] [4]. |

For researchers in synthetic biology and drug development, obtaining custom synthetic DNA is a critical first step for experiments ranging from protein engineering to gene therapy vector development. The dominant model for this process has been centralized manufacturing, where specialized commercial vendors synthesize and deliver DNA constructs. While reliable for simple sequences, this model presents significant limitations for advanced research, particularly when working with large or complex DNA constructs. Centralized DNA synthesis is often characterized by lengthy turnaround times of several weeks, high costs that constrain project scope, and an inability to reliably produce sequences deemed "complex" due to high GC content, repetitive elements, or secondary structures [7] [8]. This article establishes a technical support framework to help researchers troubleshoot these limitations and provides guidance on emerging decentralized alternatives that can accelerate your research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Centralization Problems

This section addresses specific issues researchers encounter when relying on centralized DNA synthesis vendors and offers practical solutions.

FAQ 1: My DNA sequence was rejected by a vendor as "not synthesizable." What does this mean and what are my options?

- Problem: Vendor rejection of complex DNA sequences.

- Explanation: Commercial DNA synthesis vendors primarily use chemical synthesis methods (phosphoramidite chemistry) that damage DNA during production. This forces them to stitch together dozens of short molecules, a process that fails for sequences with complex features [8]. These features include:

- High GC Content (>70% or <30%): Impedes proper base pairing during assembly.

- Homopolymers: Stretches of repeated bases (e.g., AAAA...).

- Hairpins and Secondary Structures: Sequences that fold back on themselves.

- Long Repetitive Elements: Complicates accurate assembly and sequencing.

- Solution:

- Enzymatic Synthesis Services: Consider vendors like Ansa Biotechnologies, which use enzymatic DNA synthesis (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, TdT). This method is less damaging and allows for the direct synthesis of long, complex sequences without stitching, bypassing many traditional limitations [8] [9].

- In-House Decentralized Workflow: Implement a lab-scale gene construction method. A decentralized workflow using pooled oligonucleotides, optimized assembly design (DAD), and Golden Gate Assembly can successfully construct genes rejected by commercial providers [7].

FAQ 2: How can I reduce the cost and time required to obtain DNA constructs for iterative design-build-test cycles?

- Problem: Multi-week turnaround times and high costs slow down research cycles.

- Explanation: Centralized vendors have inherent logistical delays and high markups, especially for double-stranded DNA fragments [7].

- Solution: Adopt a decentralized, in-house DNA construction pipeline.

- Cost Savings: Using pooled oligonucleotides as starting material can deliver a 3- to 5-fold reduction in raw DNA costs compared to ordering dsDNA fragments [7].

- Speed: A well-optimized, parallelized lab workflow can deliver sequence-confirmed constructs in as little as four days, compared to several weeks with commercial vendors [7].

- Protocol: The core of this approach is a streamlined, three-step workflow:

- Design and Retrieval: Use tools like the NEBridge SplitSet Lite High-Throughput web tool to divide gene sequences into codon-optimized fragments. Combine this with Data-Optimized Assembly Design (DAD) to computationally optimize ligation fidelity. Fragments are then retrieved from a pooled oligo library via multiplex PCR [7].

- One-Pot Assembly: Perform Golden Gate Assembly using a Type IIS restriction enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2) and T4 DNA ligase to seamlessly assemble the fragments [7].

- Transformation and Verification: Transform the assembled product into E. coli and screen for correct constructs [7].

FAQ 3: I am attempting to clone a large construct (>10 kb) and getting few or no transformants. What is the cause and how can I fix it?

- Problem: Low cloning efficiency for large DNA constructs.

- Explanation: Large DNA constructs are more susceptible to damage and pose a greater physical challenge for bacterial cells to uptake. Standard cloning strains and protocols are often optimized for smaller plasmids [10].

- Solution:

- Competent Cells: Use specialized competent cell strains designed for large constructs, such as NEB 10-beta or NEB Stable Competent E. coli [10].

- Transformation Method: For constructs larger than 10 kb, use electroporation instead of heat shock, as it is generally more efficient for large molecules [10].

- Molar Ratios: When setting up ligations, remember that with large constructs, you may need to adjust the mass of DNA used to achieve the optimal 20-30 fmol range for end compatibility [10].

Quantitative Analysis: Centralized vs. Decentralized DNA Workflows

The tables below summarize key performance and capability differences between traditional centralized DNA synthesis and modern decentralized workflows.

Table 1: Performance and Economic Comparison

| Metric | Centralized Vendor Synthesis | Decentralized In-House Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Turnaround Time | Several weeks [7] | ~4 days [7] |

| Cost per Construct | High, with significant markup on dsDNA fragments | 3- to 5-fold reduction vs. dsDNA fragments [7] |

| Iteration Speed | Slow, constrained by shipping and vendor scheduling | Fast, enables rapid design-build-test cycles [7] |

| Optimal Use Case | Standard, non-complex sequences; labs without molecular biology capabilities | Complex sequences; high-throughput projects; iterative engineering |

Table 2: DNA Construct Capability Comparison

| Capability | Centralized Vendor Synthesis | Decentralized & Advanced Vendor Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Length (Typical) | ~10 kb [9] | Up to 50 kb (enzymatic synthesis) [9] |

| Handling of Complex Sequences | Often rejects or fails on high GC%, repeats, hairpins [8] | Specialized workflows and enzymes can succeed [7] [8] |

| Example Success | N/A | 389 kb of functional DNA from 458 genes, including sequences with extreme GC content [7] |

Experimental Protocol: Decentralized Gene Assembly via Golden Gate Assembly

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for constructing genes in-house, based on the decentralized workflow that addresses centralization problems [7].

Objective: To assemble a target gene from a pool of oligonucleotides in 4 days using a DAD-optimized Golden Gate Assembly workflow.

Principle: The protocol leverages NEBridge SplitSet Lite for fragment design, Data-Optimized Assembly Design (DAD) for selecting optimal overhangs, and Golden Gate Assembly. Golden Gate Assembly uses Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI-HFv2), which cleave DNA outside their recognition site, enabling the creation of custom overhangs that facilitate the seamless, one-pot, directional assembly of multiple DNA fragments [7] [2].

Workflow Diagram:

Materials & Reagents:

- Oligonucleotide Pool: Designed by NEBridge SplitSet Lite and ordered from a vendor.

- PCR Reagents: Polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and barcode primers for fragment retrieval.

- Golden Gate Assembly Mix: Type IIS Restriction Enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2), T4 DNA Ligase, and corresponding reaction buffer.

- Cloning Reagents: Competent E. coli cells (e.g., NEB 10-beta for large constructs), LB media, and antibiotic plates.

Procedure:

Day 1: Design and Retrieval

- Input your codon-optimized gene sequence into the NEBridge SplitSet Lite High-Throughput web tool. The tool will automatically divide the sequence into equal-sized fragments with optimal break points and assign unique barcode primers.

- The design is integrated with DAD, which analyzes a fidelity dataset to assign the most reliable overhangs for assembly, minimizing misligation.

- Order the designed oligonucleotides as a single, pooled library.

- Upon receiving the pool, perform multiplex PCR using a single primer pair to retrieve the specific DNA fragments for your target gene. Purify the PCR products.

Day 2: Golden Gate Assembly

- Set up the Golden Gate Assembly reaction by combining the purified fragments, BsaI-HFv2, T4 DNA Ligase, and reaction buffer in a single tube.

- Run the reaction in a thermocycler with a program that cycles between the restriction enzyme's cutting temperature (e.g., 37°C) and the ligase's optimal temperature (e.g., 16°C). This allows for iterative cutting and ligation, driving the assembly toward the correct product where the restriction sites are eliminated.

Day 3: Transformation

- Transform the Golden Gate Assembly reaction into an appropriate strain of competent E. coli cells.

- Plate the transformation on antibiotic-containing agar plates and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Day 4: Screening and Verification

- Pick colonies and screen for correct assemblies (e.g., by colony PCR or analytical digestion).

- Send positive clones for sequencing to verify the final, seamless construct.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Advanced DNA Assembly

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Assembly

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIS Restriction Enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2) | Cleaves DNA at an offset from its recognition site, enabling creation of custom, seamless overhangs. | Core enzyme for Golden Gate Assembly and other modern, seamless assembly methods [7] [2]. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments by catalyzing phosphodiester bond formation. | Used in conjunction with Type IIS enzymes in Golden Gate Assembly for one-pot, simultaneous digestion and ligation [7]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5) | Amplifies DNA with very low error rates. | Essential for accurate PCR amplification of inserts and fragments for assembly, minimizing introduced mutations [10]. |

| Specialized Competent E. coli (e.g., NEB 10-beta) | High-efficiency bacterial strains for plasmid transformation. | RecA- strains reduce recombination; McrA-/McrBC-/Mrr- strains prevent degradation of methylated plant/mammalian DNA; some are optimized for large constructs [10]. |

| Data-Optimized Assembly Design (DAD) | Computational framework that predicts optimal overhangs for multi-fragment assembly. | A data-driven tool that increases assembly fidelity and success rates by minimizing misligation in complex designs [7]. |

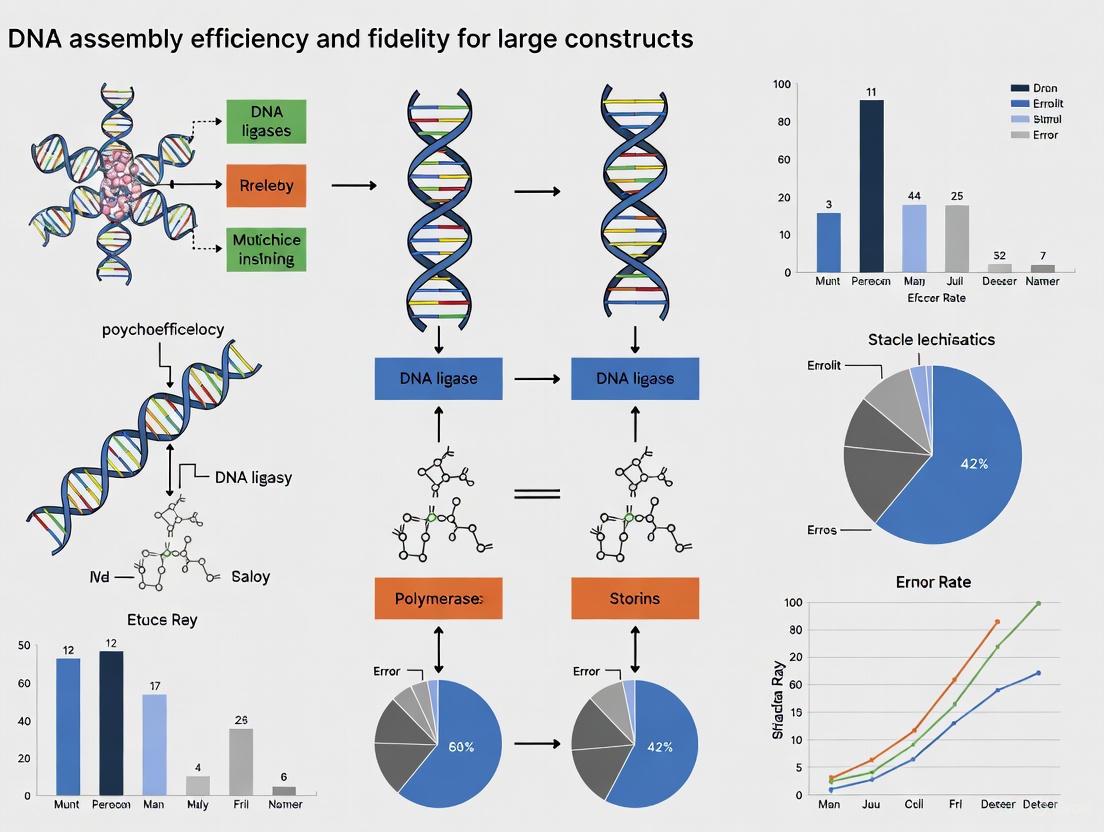

For researchers in drug development and synthetic biology, the successful assembly of DNA constructs is a foundational step. When working with large constructs, such as those for gene therapy vectors or complex metabolic pathways, two metrics become paramount: efficiency (the success rate of the assembly reaction) and fidelity (the accuracy with which fragments are joined without errors). Understanding and optimizing the factors that govern these metrics is critical for accelerating research and development timelines. This guide defines these key parameters, provides standardized protocols for their assessment, and offers solutions for common experimental challenges.

FAQ: Understanding Efficiency and Fidelity

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between assembly efficiency and fidelity?

Efficiency refers to the success rate of an assembly reaction, typically measured by the number of correct colonies obtained after transforming the assembled product into a host cell. It is often quantified as Colony Forming Units (CFU) per microgram of assembled DNA or the percentage of correct assemblies obtained. High efficiency is crucial for complex assemblies involving many fragments, as it increases the likelihood of finding a correct clone without extensive screening [2].

Fidelity refers to the accuracy of the junctions between assembled DNA fragments. A high-fidelity reaction produces constructs where all fragments are joined in the correct order and orientation, with no sequence errors at the fusion sites. Low fidelity results in assemblies with scrambled orders, incorrect ligation, or base pair mutations at the junctions, rendering the construct useless [11].

Q2: Which method is best for assembling a large number of DNA fragments with high fidelity?

Golden Gate Assembly is particularly well-suited for this task. It utilizes Type IIS restriction enzymes, which cut DNA outside of their recognition sequence, generating unique, user-defined overhangs (or "sticky ends") for each fragment. When combined with a high-fidelity DNA ligase like T4 ligase, this allows for the simultaneous and orderly assembly of many fragments in a single reaction [2].

Recent advances using data-optimized assembly design have dramatically increased the complexity achievable with Golden Gate Assembly. By applying comprehensive datasets on ligase fidelity, researchers can now select optimal sets of overhang sequences that minimize mis-ligation. This approach has enabled the successful one-pot assembly of 12, 24, or even 36+ DNA fragments into constructs exceeding 40 kilobases [12] [11].

Q3: Our assembly reactions are efficient but often produce clones with incorrect sequences. How can we improve fidelity?

This common issue often stems from mis-ligation of overhangs. To address it:

- Use Pre-Validated Overhang Sets: Instead of designing custom overhangs, use published, high-fidelity overhang sets that have been experimentally validated to minimize cross-hybridization and mis-ligation [11].

- Leverage Online Design Tools: Apply web-based tools that use comprehensive ligation fidelity data to analyze your proposed junction sequences or generate new high-fidelity overhang sets for your specific fragments [11].

- Optimize Reaction Conditions: Ensure your protocol uses a high-fidelity ligase and the correct cycling conditions (alternating between digestion and ligation temperatures) to favor accurate assembly.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Assembly Efficiency | - Insufficient DNA quantity or purity- Suboptimal enzyme ratios- Inefficient transformation | - Check DNA concentration and purity via spectrophotometry- Titrate restriction enzyme and ligase concentrations- Include a positive control assembly to test transformation efficiency [2] |

| High Efficiency, Low Fidelity | - Mis-ligation of compatible overhangs- Limited number of unique overhangs | - Redesign fragments using a high-fidelity, sequence-validated overhang set- Use software tools to select overhangs with minimal cross-talk [11] |

| Incorrect Fragment Order | - Non-unique overhang sequences- Incomplete digestion by restriction enzymes | - Verify that each fusion site uses a distinct overhang sequence- Ensure fresh, high-activity restriction enzymes are used; extend digestion time [2] |

Quantitative Comparison of DNA Assembly Methods

The choice of assembly method significantly impacts both efficiency and fidelity. The table below summarizes key characteristics of prominent techniques, highlighting trade-offs between seamlessness, cost, and suitability for large constructs [2].

| Method | Junction Type | Sequence Dependency | Typical Max Fragments (One-Pot) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzyme (REC) | Scarred | Dependent (requires specific sites) | 1-2 | Simple, well-established | Leaves unwanted "scar" sequences; limited flexibility [2] |

| Gateway | Scarred | Dependent (requires att sites) | 1 (for entry clone) | Highly efficient for cloning and transfer | Introduction of long att site "scars"; requires proprietary vectors [2] |

| TOPO-TA | Scarred | Independent | 1 | Very fast and simple | Limited to 1 fragment; low fidelity; costly [2] |

| Golden Gate | Seamless | Independent (via overhang design) | 36+ [12] | High fidelity, multi-fragment, scarless | Requires careful overhang design [2] [11] |

| Exonuclease-based Seamless (ESC) | Seamless | Independent | 4-6 | Scarless, sequence-independent | Can be less efficient than Golden Gate for very high complexity [2] |

| In Vivo Assembly | Seamless | Independent | Varies | Cost-effective, uses cellular machinery | Lower efficiency; requires optimization of host strain [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Efficiency and Fidelity

Protocol 1: Standardized Golden Gate Assembly with High-Fidelity Overhangs

This protocol is optimized for assembling multiple fragments using data-optimized design principles [12] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Type IIS Restriction Enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2): Cleaves DNA to generate specific overhangs.

- High-Fidelity T4 DNA Ligase: Joins DNA fragments with high accuracy.

- DNA Fragments with Validated Overhangs: Each fragment must be flanked by designed overhangs.

- Competent E. coli (High Efficiency): Essential for transforming large assembled constructs.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a single tube, combine:

- 50-100 ng of each DNA fragment (equimolar ratio)

- 1 µL of Type IIS Restriction Enzyme (e.g., BsaI, 10,000 units/mL)

- 1 µL of T4 DNA Ligase (400,000 units/mL)

- 2 µL of 10x T4 Ligase Buffer

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 µL.

- Thermocycling: Place the tube in a thermocycler and run the following program:

- Cycle 1: 37°C for 5 minutes (digestion), then 16°C for 5 minutes (ligation). Repeat this cycle for 50 rounds.

- Final Step: 60°C for 10 minutes (enzyme inactivation), then hold at 4°C.

- Transformation: Transform 2-5 µL of the assembly reaction into 50 µL of high-efficiency competent E. coli. Plate onto selective agar and incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Efficiency Calculation: Count the number of colonies.

- Efficiency (CFU/µg) = (Number of colonies × Dilution factor) / (Amount of DNA transformed in µg)

Protocol 2: Verifying Assembly Fidelity by Diagnostic PCR and Sequencing

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Colony PCR Master Mix: Contains Taq polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer.

- Sequence-Specific Primers: Designed to span each junction in the final assembled construct.

- Sanger Sequencing Services: For definitive verification of sequence accuracy.

Procedure:

- Colony PCR: Pick 8-12 individual colonies and resuspend in a PCR mix containing primers that flank the fusion sites of your assembled construct.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Run the PCR products on an agarose gel. Correct assemblies will show a single band of the expected size.

- Sequence Verification: Inoculate a culture from colonies that passed the PCR screen. Isolate plasmid DNA and submit for Sanger sequencing using primers that cover every junction between fragments.

- Fidelity Calculation:

- Fidelity (%) = (Number of sequence-verified correct clones / Total number of clones screened) × 100

Workflow and Optimization Cycle

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for designing, executing, and troubleshooting a high-fidelity DNA assembly, incorporating the modern Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle used in automated biofoundries [13] [14].

DNA Assembly Optimization Workflow

Emerging Technologies and Future Outlook

The field of DNA assembly is being transformed by automation and artificial intelligence. Biofoundries (automated synthetic biology labs) are now integrating machine learning (ML) models into their workflows. These AI-driven systems can dynamically optimize assembly protocols, diagnose failures by analyzing experimental data, and continuously improve the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, leading to progressively higher efficiency and fidelity with each iteration [13] [14].

For the most challenging applications involving very large DNA constructs, such as entire synthetic genomes or complex therapeutic vectors, hierarchical assembly strategies are key. This involves first assembling smaller fragments (e.g., 5-10 kb) in a primary Golden Gate reaction, and then using these larger "sub-assemblies" as parts for a subsequent, higher-level assembly round. This modular approach significantly increases the reliability and success rate of building constructs over 100 kb in size [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

GC Content Bias

Problem: Uneven sequencing coverage and reduced representation of genomic regions with extremely high or low GC content, leading to gaps in data and inaccurate copy number variation analysis [15] [16].

Underlying Cause: During library preparation, PCR amplification is less efficient for both GC-rich fragments (which form stable secondary structures) and AT-rich fragments (which have less stable DNA duplexes), causing their under-representation in sequencing results [15] [16].

Table: Identifying and Correcting GC Content Bias

| Problem Manifestation | Recommended Experimental Protocol Adjustments | Bioinformatic Correction Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Low coverage in GC-rich regions (>60% GC) [16] | Use polymerases engineered for high GC content; reduce PCR cycle number; employ mechanical fragmentation (e.g., sonication) over enzymatic methods [16]. | Use algorithms (e.g., in Picard tools) to normalize read depth based on local GC content [15] [16]. |

| Low coverage in AT-rich regions (<40% GC) [16] | Optimize PCR parameters; use PCR-free library prep workflows (requires higher input DNA) [16]. | Apply GC-curve modeling to correct coverage imbalances [15]. |

| Skewed fragment count data in DNA-seq | Analyze the GC content of the entire DNA fragment, not just the sequenced read, for more accurate bias modeling [15]. | Implement a parsimonious unimodal model that predicts under-representation of both high-GC and high-AT fragments [15]. |

Repetitive Sequences and Tandem Repeats

Problem: Repetitive DNA sequences, particularly tandem repeats (TRs), cause misassembly during sequencing, leading to gaps, collapsed regions, and mis-annotation in genome databases [17] [18]. This is especially problematic for large constructs.

Underlying Cause: Short-read sequencing technologies cannot unambiguously resolve long stretches of identical or highly similar repeat units, confusing assembly algorithms [17].

Table: Strategies for Managing Repetitive Sequences in Large Constructs

| Challenge | Impact on Large Constructs | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Assembly Collapse [17] | The number of repeats in the final assembly is fewer than in the original genome. | Use long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio, Nanopore) to span repetitive regions [18]. |

| Mis-assembly & Mis-annotation [17] [18] | Incorrect assembly leads to frameshifts and errors in protein databases, affecting functional studies. | Employ specialized bioinformatics tools (e.g., RepeatExplorer) for detection and characterization; manual curation of automated annotations [18]. |

| Unclassifiable Repeats [18] | Complex loci, like satellite DNA associated with Helitron transposable elements, resist standard classification. | Combine multiple assembly strategies and leverage updated repeat databases tailored to specific model organisms [18]. |

Secondary Structures

Problem: Intramolecular base-pairing within single-stranded nucleic acids creates stable secondary structures (e.g., hairpins, stem-loops, G-quadruplexes) that hinder enzymatic processes in cloning and sequencing [16].

Underlying Cause: These structures block the progression of DNA polymerases during PCR and can interfere with restriction enzymes and ligases during cloning [16].

Solutions:

- Experimental Adjustments:

- Use DNA polymerases with high strand displacement activity.

- Increase reaction temperature to destabilize secondary structures.

- Include additives like DMSO, betaine, or formamide in PCR or sequencing reactions to denature stable structures.

- Redesign primers or constructs to avoid highly structured regions, if possible.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Use prediction tools (e.g., Mfold, RNAfold) to identify regions prone to forming stable secondary structures prior to experiment design [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My sequencing data shows a severe coverage drop in a GC-rich promoter region I am studying. What is the most effective wet-lab method to correct this? A: The most effective wet-lab method is to adopt a PCR-free library preparation workflow. This eliminates the PCR amplification step, which is the primary cause of GC bias, thereby ensuring a more uniform representation of all genomic regions regardless of their GC content. Note that this approach typically requires higher amounts of input DNA [16].

Q2: Why do repetitive sequences remain a major challenge even with modern sequencing platforms? A: While long-read technologies have improved the situation, repetitive sequences remain challenging due to classification problems. Many repetitive sequences, especially in organisms like bivalves, exist in complex loci where tandem repeats are associated with transposable elements (e.g., Helitrons). These "hybrid" structures often remain unclassified by automated pipelines, leading to gaps in genomic data and requiring manual curation for accurate characterization [18].

Q3: I suspect secondary structure formation is causing my cloning efficiency to plummet. What are my first steps in troubleshooting? A: Your first step should be to use a specialized cloning strain and polymerase. For the transformation, use a strain like NEB 5-alpha F´ Iq Competent E. coli, which provides tighter transcriptional control and can help with toxicity. For PCR amplification of the insert, use a high-fidelity polymerase engineered to amplify through difficult secondary structures. Additionally, you can add DMSO (1-5%) to your PCR reaction to help denature stable structures [20].

Q4: How can I check my sequencing data for the presence of GC bias? A: You can use quality control tools like FastQC or MultiQC, which provide graphical reports showing the relationship between GC content and read coverage across your sequenced genome. A uniform distribution indicates minimal bias, while a skewed distribution confirms GC bias [16].

Experimental Workflow for Mitigating Hurdles in Large Construct Assembly

The following diagram outlines a integrated experimental strategy to overcome GC bias, repetitive sequences, and secondary structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Overcoming DNA Assembly Hurdles

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Specific Application |

|---|---|---|

| PCR-free Library Prep Kits | Eliminates PCR amplification bias during NGS library preparation, ensuring uniform coverage of high/low GC regions. | Mitigating GC bias for accurate whole-genome sequencing [16]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Engineered enzymes with high processivity and strand-displacement activity. | Amplifying GC-rich templates and disrupting stable secondary structures during PCR [20]. |

| Competent E. coli (e.g., NEB Stable) | Specialized bacterial strains deficient in recombination systems (recA-) and restriction systems (McrA-, McrBC-). | Improving yield and stability of large, repetitive, or methylated DNA constructs [20]. |

| Additives (DMSO, Betaine) | Reduce secondary structure formation by lowering DNA melting temperature. | Added to PCR mixes to improve amplification efficiency through structured regions [20]. |

| Long-read Sequencing (PacBio/Oxford Nanopore) | Generates sequencing reads thousands of bases long, spanning repetitive regions. | Resolving complex, repetitive areas in large constructs that confuse short-read assemblers [18]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools (FastQC, MultiQC, RepeatExplorer) | QC tools for bias detection and specialized software for repeat identification and classification. | Identifying GC bias and characterizing complex repetitive elements post-sequencing [16] [18]. |

Modern DNA Assembly Frameworks: From Golden Gate to Gibson and Beyond

FAQs: Understanding Data-Optimized Assembly Design (DAD)

Q1: What is Data-Optimized Assembly Design (DAD) and how does it differ from traditional Golden Gate Assembly design?

A1: Data-Optimized Assembly Design (DAD) is a computational framework that uses comprehensive, data-driven insights to select the most reliable fusion-site overhangs for multi-fragment Golden Gate Assembly (GGA) [21] [22]. Unlike traditional methods that rely on semi-empirical rules (e.g., ensuring every overhang has at least a two-base-pair difference), DAD leverages vast datasets from ligation fidelity experiments to predict and minimize misligation events before the experiment begins [22]. This shift from rule-based to data-based design enables more complex, high-fidelity, one-pot assemblies.

Q2: What specific problems does DAD solve?

A2: DAD directly addresses the core challenge of misligation in complex assemblies, which leads to two major problems:

- Reduced Yields: Misligation consumes DNA fragments non-productively [22].

- Increased Screening: Misligation creates clones with incorrect constructs, forcing researchers to screen more colonies [22]. By virtually eliminating misligation through intelligent overhang selection, DAD ensures that assemblies with 12, 24, or even more fragments proceed with high efficiency and accuracy [21] [22].

Q3: What online tools are available for implementing DAD?

A3: The following online tools, available through the NEBridge platform, are essential for implementing a DAD-guided workflow [22]:

- NEBridge SplitSet Lite High-Throughput: Automates the division of input DNA sequences into codon-optimized fragments and assigns unique barcodes for retrieval from an oligo pool [21].

- NEBridge Ligase Fidelity Viewer: Allows researchers to evaluate the predicted fidelity of an existing set of overhangs.

- NEBridge GetSet Tool: Generates new, high-fidelity overhang sets from scratch based on the desired assembly conditions [22].

Q4: What are the practical benefits of using this DAD-guided workflow?

A4: Adopting a DAD-guided, decentralized workflow for gene construction offers significant advantages [21]:

- Speed: Delivers sequence-confirmed constructs in as little as four days, compared to weeks with commercial vendors.

- Cost Reduction: Achieves a three- to five-fold reduction in raw DNA costs by using pooled oligonucleotides.

- Accessibility: Enables the successful assembly of sequences often rejected by commercial services, such as those with extreme GC content (>70% or <30%) or high repeat content [21].

Troubleshooting Guide for DAD and Golden Gate Assembly

This guide helps diagnose and resolve common issues encountered when using DAD and Golden Gate Assembly workflows.

Problem 1: Low Assembly Yield or No Correct Colonies

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inefficient Fragment Retrieval | Gel-purify the PCR-amplified fragments from the oligo pool to ensure you are assembling the correct, full-length pieces. Quantify DNA concentration accurately [23]. |

| Suboptimal Overhang Set | Use the NEBridge Ligase Fidelity Viewer to verify your overhang set's predicted fidelity. For new designs, always use the GetSet Tool to generate a high-fidelity set [22]. |

| Too Many Fragments in a Single Assembly | While DAD enables high-complexity assemblies, success rates for constructs with >12 fragments can decline. Consider a hierarchical assembly strategy for very large constructs [21]. |

| Oligo Synthesis Errors | Errors in the starting oligo pool are a common failure point. Using high-quality oligo synthesis services is critical. The workflow is robust to typical error rates, but failures can occur [21]. |

| Incorrect Transformation | Ensure you are using high-efficiency competent cells. For large constructs (>5 kb), consider using electroporation. Do not use more than 5 µL of ligation mixture for 50 µL of chemically competent cells [24] [3]. |

Problem 2: High Background (Many Colonies with Incorrect Constructs)

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Misligation Events | This is the primary issue DAD aims to solve. Re-evaluate your overhang set with the Ligase Fidelity Viewer. Ensure you are using the correct, DAD-optimized overhangs for your specific assembly conditions (enzyme and temperature) [22]. |

| Vector Self-Ligation | If using a holding vector, ensure the restriction digestion is complete. Gel-purify the cut vector to remove any uncut background [3]. |

| Low Antibiotic Concentration | Verify the correct antibiotic concentration is used in your plates. If the concentration is too low, non-resistant satellite colonies may form [24] [3]. |

Problem 3: Mutations in the Assembled Sequence

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Errors in PCR Amplification | Use a high-fidelity PCR enzyme during the fragment retrieval step from the oligo pool to minimize introducing nucleotide errors [3] [23]. |

| Oligo Synthesis Errors | As above, the quality of the starting oligonucleotides is paramount. Sequence multiple colonies to identify and select a correct clone [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: A DAD-Guided Golden Gate Assembly Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the streamlined, three-step workflow for implementing DAD-guided gene assembly.

Step 1: Design and Retrieval of Fragments from Pooled Oligonucleotides

- Design: Input your codon-optimized gene sequence into the NEBridge SplitSet Lite High-Throughput web tool. The tool will automatically divide the sequence into equal-sized fragments at optimal break points and append the necessary Type IIS restriction enzyme sites [21].

- DAD Integration: The fragment design is seamlessly integrated with the DAD tool, which assigns high-fidelity overhangs to each fusion site to ensure optimized ligation fidelity [21].

- Oligo Pool and Retrieval: Order the designed oligonucleotides as a single, pooled library. To retrieve the double-stranded DNA fragments for assembly, perform a single round of multiplex PCR using the barcoded primers assigned by the SplitSet tool, then purify the PCR products [21].

Step 2: DAD-Guided Golden Gate Assembly

- Set Up Reaction: Combine the purified DNA fragments in a single tube with a Type IIS restriction enzyme (such as BsaI-HFv2 or BsmBI-v2) and T4 DNA Ligase in an appropriate buffer [21].

- Cycle Reaction: Run the Golden Gate Assembly using a themocycler program that alternates between the digestion temperature (e.g., 37°C) and the ligation temperature (e.g., 16°C) for 25-50 cycles. This repeated cutting and ligation drives the assembly toward the correct, seamless product where the restriction sites are eliminated [22].

Step 3: Transformation and Sequence Verification

- Transform: Transform the final assembly reaction into competent E. coli cells using a standard transformation protocol [21] [3].

- Screen and Sequence: Pick several colonies, grow them in small cultures, and isolate the plasmid DNA. Analyze the plasmids by restriction digest and Sanger sequencing to confirm the assembly is correct [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools are essential for successfully implementing the DAD-guided assembly workflow.

| Item | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (e.g., BsaI-HFv2) | Enzymes that cut distal to their recognition site to generate the custom 4-base overhangs that direct fragment assembly [21]. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins the DNA fragments via their complementary overhangs in a one-pot reaction with the Type IIS enzyme [21]. |

| NEBridge SplitSet Lite High-Throughput Tool | A web tool that automates the design process, dividing genes into fragments and assigning barcodes for retrieval from an oligo pool [21]. |

| NEBridge Ligase Fidelity Viewer / GetSet Tool | Web tools that use comprehensive fidelity data to analyze or generate high-fidelity overhang sets, which is the core of the DAD methodology [22]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Polymerase | Essential for the accurate amplification of DNA fragments from the oligonucleotide pool during the retrieval step, minimizing mutations [3]. |

| Pooled Oligonucleotide Library | The cost-effective starting material containing all the designed oligos for one or many genes, which are retrieved via PCR [21]. |

| High-Efficiency Competent E. coli Cells | Used for transformation of the assembled plasmid. For large constructs (>10 kb), electrocompetent cells are recommended [24] [21]. |

Golden Gate Assembly is a powerful molecular cloning technique that enables the seamless, one-pot assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction. This method leverages Type IIS restriction enzymes, which cleave DNA outside of their recognition sites, to create unique, user-defined overhangs that facilitate the ordered assembly of DNA parts. By combining restriction digestion and ligation in a single tube, Golden Gate Assembly eliminates scar sequences and allows for the efficient construction of complex DNA constructs, making it an indispensable tool for synthetic biology, metabolic engineering, and large-scale DNA construction projects aimed at increasing DNA assembly efficiency and fidelity for large constructs research.

How Golden Gate Assembly Works

The Golden Gate Assembly process relies on the coordinated activity of a Type IIS restriction enzyme and a DNA ligase within the same reaction tube [25]. The mechanism can be broken down into two concurrent steps:

- Type IIS Restriction Enzyme Digestion: Type IIS restriction enzymes recognize specific non-palindromic DNA sequences but cleave the DNA at a predetermined distance outside this recognition site [26] [25]. This property is crucial, as it allows for the generation of custom overhangs (typically 4-base pair sequences) that are not dictated by the enzyme's recognition sequence.

- DNA Ligation: The complementary overhangs created on the vector and insert fragments anneal to each other. T4 DNA ligase then seals the nicks, joining the DNA fragments together. The final ligated product lacks the original Type IIS recognition sites, making the assembly irreversible and driving the reaction toward completion [26] [25].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism and workflow of a Golden Gate Assembly reaction.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful Golden Gate Assembly depends on carefully selected reagents. The table below details the essential components and their functions.

| Component | Function & Importance | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIS Restriction Enzyme | Recognizes specific sequence but cuts outside it, generating custom overhangs for seamless assembly [26] [25]. | BsaI-HFv2, BsmBI-v2, PaqCI (7-bp site reduces need for domestication) [26] [27]. |

| DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments by sealing nicks in the sugar-phosphate backbone [26]. | T4 DNA Ligase; NEBridge Ligase Master Mix is optimized for assembly fidelity [26] [27]. |

| Destination Vector | Plasmid backbone into which inserts are assembled; requires outward-facing Type IIS sites [25] [27]. | Vectors like pGGAselect (versatile, no internal BsaI/BsmBI/BbsI sites) [27]. |

| Insert DNA | DNA fragments to be assembled; can be PCR amplicons or pre-cloned in entry vectors with inward-facing Type IIS sites [28] [25]. | For fragments <250 bp or >3 kb, or with repeats, use pre-cloned inserts for higher efficiency [28]. |

| Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal conditions for simultaneous restriction and ligation enzyme activity. | T4 DNA Ligase Buffer (supplemented with ATP/DTT) is standard; specific NEBuffers are alternatives [27]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Standard Golden Gate Assembly Workflow

This protocol is suitable for most assemblies and can be scaled down to a 10 µL volume to increase enzyme-to-DNA concentration [28].

- Reaction Setup: In a single tube, combine the following:

- Destination vector (e.g., 75-100 ng for pre-cloned inserts in assemblies with ≤10 fragments) [28] [29].

- Insert fragments at a 2:1 molar ratio relative to the destination plasmid [28] [29].

- Type IIS restriction enzyme (e.g., 5 units of BsaI or BsmBI) [29].

- T4 DNA ligase (e.g., 200 units) [29].

- Appropriate reaction buffer (e.g., T4 DNA Ligase Buffer).

- Thermal Cycling:

- Transformation and Screening: Transform 1-2 µL of the reaction into competent E. coli and plate on selective media [28].

Advanced and Alternative Protocols

For more complex scenarios, the following optimized protocols are recommended.

| Protocol Type | Application Context | Detailed Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Extended Cycling | Complex assemblies (>10 fragments) to increase efficiency without sacrificing fidelity [27]. | Increase total thermocycles from 30 to 45-65 cycles, maintaining 5-minute digestion and ligation steps [27]. |

| Two-Step, Non-Cycling | Fragments with internal Type IIS sites; critical to end reaction with a ligation step [28]. | Step 1: Incubate with restriction enzyme only at 37°C for 30 min.Step 2: Heat-inactivate at 65°C for 20 min.Step 3: Add T4 DNA ligase, incubate at 25°C for 30 min [28]. |

| Cold-Treated Ligation | Simplified method for creating entry clones where the final product contains recognition sites (e.g., Golden EGG system) [30]. | Perform standard digestion-ligation incubation (e.g., 37°C for 5-15 min), then shift reaction to 4°C for 15 minutes to favor ligase activity over restriction [30]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

This section addresses specific problems researchers may encounter during Golden Gate Assembly experiments.

| Problem & Phenotype | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Optimizations |

|---|---|---|

| No ColoniesNo growth on selective plates after transformation. | • Low-efficiency competent cells.• Plasmid mutation or DNA degradation.• Ligation enzyme issue [28]. | • Use high-efficiency cells (e.g., ~1e4 cfu/ng pUC18 for electrocompetent) [28].• Sequence all parts; check for DNase contamination [28].• Plate the entire transformation mixture [28]. |

| High Background / Fluorescent ColoniesMany colonies with empty vector (e.g., fluorescent when using a dropout marker). | • Inactive/old Type IIS restriction enzyme.• Suboptimal cycling conditions [28]. | • Use fresh aliquots of BsaI/BsmBI; perform diagnostic digest [28].• Extend cutting time per cycle (1.5 min to 3-5 min); increase total cycles to 30+ [28]. |

| Incorrect AssembliesRepetitive mutations or misassembled plasmids in final construct. | • Misligation due to non-unique overhangs.• Costly, toxic, or unstable inserts [28]. | • Use NEBridge Ligase Fidelity Tool to design high-fidelity overhangs [27]. Ensure 3 of 4 overhang bases are unique [29].• Use stable backbones (e.g., p15A origin); pick more colonies [28]. |

| Low Efficiency for Complex AssembliesFew correct colonies with multi-fragment assemblies. | • High number of fragments (>10-12).• Internal Type IIS sites in fragments.• Primer dimers in amplicon inserts [28] [27]. | • Pre-clone fragments <250 bp or >3 kb [28]. For >10 fragments, reduce each pre-cloned insert to 50 ng [27].• "Domesticate" internal sites via mutagenesis or use an enzyme with a longer recognition site (e.g., PaqCI) [27].• Gel-purify PCR amplicons to remove primer dimers [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I handle DNA fragments that contain internal BsaI or BsmBI restriction sites? Internal sites can be addressed in several ways. The preferred method is domestication, which involves using site-directed mutagenesis to silently remove the internal restriction site [25] [27]. Alternatively, you can switch to a Type IIS enzyme with a longer, rarer recognition site, such as PaqCI (7-base pair site) [27], or employ a two-step protocol that ends with a ligation step to prevent re-digestion of the final product [28].

Q2: What is the recommended molar ratio of inserts to vector, and how is it calculated?

A 2:1 insert-to-vector molar ratio is generally recommended for optimal results [28] [29]. The amount of each insert (in nanograms) to add to a reaction can be calculated using the formula: [Insert Size (bp) / Vector Size (bp)] x 200 = ng of insert [29]. The process is robust and 1:1 ratios can also work [28].

Q3: Can Golden Gate Assembly be used with vectors not specifically designed for it? Yes, recent advancements like Expanded Golden Gate (ExGG) allow Golden Gate-like assembly into a much broader range of plasmids with standard Type IIP restriction sites (e.g., EcoRI, XhoI) [31] [32]. In ExGG, inserts are designed with Type IIS sites (e.g., BsaI) that generate overhangs compatible with the digested vector. A key feature is a "recut blocker," a single base change that prevents the restored vector site from being cleaved after ligation, enabling one-pot, one-step reactions [31].

Q4: How can I improve the efficiency and fidelity of a complex assembly with many fragments? For assemblies involving more than 10 fragments:

- Increase Cycling: Extend the total number of thermocycling steps from 30 to 45-65 cycles to drive the reaction further to completion [27].

- Optimize Overhang Design: Use data-driven tools like NEB's NEBridge Ligase Fidelity Tool or Data-optimized Assembly Design (DAD) to select overhang sequences that minimize misligation and improve assembly accuracy [33] [27].

- Use High-Quality DNA: For complex assemblies, use midi-prepped plasmid DNA instead of mini-preps to ensure high purity and accurate concentration [29].

Q5: What are the key considerations when designing primers to generate inserts via PCR?

- Orientation: Type IIS recognition sites in the primers must face inwards towards the DNA insert to be assembled [25] [27].

- Fidelity: Use a high-fidelity, proofreading DNA polymerase (e.g., Q5 DNA Polymerase) and avoid over-cycling the PCR to prevent mutations [27].

- Specificity: Ensure PCR produces a specific product without primer dimers, as dimers containing restriction sites can participate in the assembly and cause misassemblies [27].

- Overhang Sequence: Carefully design the 4-base overhang sequence for each junction to ensure correct and ordered assembly [27].

The pursuit of increased efficiency and fidelity in DNA assembly is a cornerstone of modern synthetic biology and therapeutic development. For researchers and drug development professionals engineering complex genetic circuits or large metabolic pathways, the limitations of traditional, restriction-enzyme-based cloning are a significant bottleneck. Gibson Assembly, and a new generation of exonuclease-based methods derived from it, represent a powerful alternative. These isothermal, one-pot techniques enable the seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction without the need for specific restriction sites, dramatically accelerating the construction of even the largest DNA constructs [34] [35]. This technical resource center details the mechanisms, optimal protocols, and troubleshooting strategies for these methods, providing a foundation for maximizing assembly success and fidelity in your research.

Core Mechanism: The Enzymatic Workflow

Gibson Assembly is an elegant, one-pot reaction that utilizes three enzymes acting in concert to join multiple overlapping DNA fragments. The process is isothermal, typically performed at 50°C, and can be completed in as little as 15-60 minutes [34] [35]. The mechanism relies on sequence homology between the ends of adjacent DNA fragments, which allows them to anneal after enzymatic processing.

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated, multi-step enzymatic mechanism that allows for the seamless assembly of DNA fragments.

This synergistic process is highly efficient, allowing for the simultaneous assembly of several fragments. The key to successful assembly lies in the careful design of the DNA fragments to ensure sufficient and accurate homology at the junctions [34] [36].

Method Comparison and Selection Guide

While Gibson Assembly is a foundational technique, several related methods have been developed, each with unique advantages. The table below provides a structured comparison of key exonuclease-based assembly methods to help you select the best one for your experimental needs.

| Method | Core Enzymes | Key Feature | Optimal Overlap | Reaction Temperature | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibson Assembly | T5 Exo, Polymerase, Ligase | Classic one-pot, three-enzyme system [35] | 20-40 bp [34] [36] | 50°C [34] | Standard multi-fragment assembly; large constructs up to 100 kb+ [34] |

| NEBuilder HiFi | Proprietary enzyme mix | Enhanced fidelity and efficiency; lower DNA input [37] | 15-30 bp [37] | Defined by manufacturer | High-fidelity applications; assembling fragments with low DNA inputs [37] |

| SENAX | XthA (ExoIII) only | Single 3'-5' exonuclease; very short fragment assembly [38] | 12-18 bp [38] | 30-37°C [38] | Direct assembly of short fragments (down to 70 bp); low-temperature reactions [38] |

| AFEAP Cloning | PCR + T4 DNA Ligase | Two-round PCR creates sticky ends for ligation [39] | 5-8 bp (optimized) [39] | PCR + Ligation steps | Assembling a high number of fragments (up to 13) [39] |

Quantitative Performance Data

When planning experiments, especially with large or complex constructs, understanding the practical limits and expected outcomes of each method is crucial. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from the literature.

| Method | Max Fragments Assembled | Max Construct Size Demonstrated | Reported Fidelity/Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibson Assembly | 5+ fragments documented [34] | ~100 kb+ [34] | Potential for mutations at boundaries (~1 in 50 assemblies) [34] |

| NEBuilder HiFi | Not specified | >15 kb (requires high-efficiency cells) [37] | Virtually error-free, high-fidelity assembly [37] |

| SENAX | Up to 6 fragments [38] | Tested with 1-10 kb backbones [38] | High efficiency, comparable to Gibson and In-Fusion [38] |

| AFEAP Cloning | Up to 13 fragments [39] | 35.6 kb (from 5 fragments), 200 kb BAC [39] | 81.67% (35.6 kb) to 91.67% (11.6 kb) [39] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful assembly reaction requires high-quality reagents and materials. The table below lists the essential components for a standard Gibson Assembly reaction and their specific functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| T5 Exonuclease | Chews back the 5' ends of DNA fragments to create single-stranded 3' overhangs for annealing [35]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Phusion) | Fills in the gaps within the annealed DNA fragments after the overhangs have hybridized [34] [35]. |

| DNA Ligase (e.g., Taq Ligase) | Seals the nicks in the assembled DNA backbone, creating a contiguous, double-stranded molecule [34] [35]. |

| Isothermal Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal conditions (pH, salts, co-factors) for all three enzymes to function simultaneously at 50°C [34]. |

| dNTPs | Nucleotide building blocks used by the polymerase to fill in the gaps in the annealed DNA [34]. |

| NAD | Essential cofactor required for the DNA ligase to function effectively [34]. |

| High-Efficiency Competent E. coli (e.g., NEB 10-beta) | Critical for transforming the assembled plasmid, especially for constructs larger than 15 kb [37]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Primer and DNA Fragment Preparation

- Design: For each junction between DNA fragments, design primers to amplify your parts such that each adjacent pair shares a 20-40 base pair overlap. For a simple insertion, the insert should have ends homologous to the target site in the linearized vector [35] [36].

- Amplify: PCR-amplify all DNA fragments using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase to minimize introduced errors.

- Purify: Gel-purify PCR products to ensure correct size and remove non-specific amplification. Alternatively, a PCR cleanup kit can be used, though this may yield more background colonies from undigested template plasmid [34].

Gibson Assembly Reaction Setup

- Thaw: Thaw an aliquot of the Gibson Assembly master mix on ice.

- Combine: In a thin-walled PCR tube, mix the following on ice:

- DNA Fragments: 0.1 pmol of each DNA fragment to be assembled. For a typical ~6 kb fragment, use 10-100 ng. For larger fragments, use proportionally more DNA (e.g., 250 ng for a 150 kb segment) [34].

- Master Mix: 15 μl of Gibson Assembly master mix.

- Ensure the final mixture contains DNA fragments in equimolar amounts for optimal results [35].

- Incubate: Incubate the reaction tube at 50°C for 15-60 minutes (60 minutes is optimal for most assemblies) [34].

- Transform: Transform 2-5 μl of the assembly reaction into high-efficiency chemically competent or electrocompetent E. coli cells. Note that the reaction product is salty, which can be problematic for electroporation; dilution of the competent cells may be necessary [34].

Advanced Application: Modular DNA Assembly with SENAX

For projects requiring high modularity and the reuse of short genetic parts like promoters and RBSs, the SENAX method offers a significant advantage. Its ability to assemble very short fragments (down to 70 bp) using a single enzyme and short homology arms (12-18 bp) enables a more flexible and cost-effective workflow compared to traditional methods [38]. The diagram below contrasts the standard Gibson workflow with the modular SENAX approach for reusing short bioparts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: I am getting very few or no colonies after transformation. What could be wrong?

- Check DNA Quality and Quantity: Ensure your DNA fragments are clean and in equimolar amounts. Too little DNA will yield few colonies, while too much can be inhibitory. Verify concentrations with a fluorometer [34] [35].

- Verify Overlap Design: Ensure homology overlaps are sufficient in length (at least 20 bp for Gibson) and do not contain strong secondary structures like hairpins, which can prevent annealing [35].

- Transformation Efficiency: Use high-efficiency competent cells. For constructs larger than 15 kb, NEB recommends NEB 10-beta Competent E. coli [37]. Remember that the Gibson reaction product is salty; if using electrocompetent cells, diluting the cells or performing an ethanol precipitation of the DNA may be necessary [34].

Q2: Many of my colonies contain plasmids with incorrect assemblies or mutations at the junctions. How can I improve fidelity?

- Use High-Fidelity Polymerase: Always use a high-fidelity polymerase during the initial PCR amplification of your fragments to reduce errors introduced prior to assembly.

- Screen with Diagnostic Digests: Before sequencing, perform analytical restriction digests to quickly identify correctly assembled plasmids [35].

- Sequence the Junctions: Always sequence the seams between assembled parts, as this is where mutations are most likely to occur. One study noted a mutation rate of approximately 1 in 50 assemblies at the boundaries [34].

- Consider NEBuilder HiFi: If fidelity is a persistent issue, switching to NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix may help, as it was specifically developed for high accuracy and virtually error-free assembly [37].

Q3: How many DNA fragments can I assemble simultaneously in a single reaction? While the original Gibson Assembly paper documented the successful assembly of 5 fragments (4 inserts + backbone) [34], many labs observe a sharp decrease in success rate when assembling more than five fragments at a time [35]. For highly complex assemblies, consider breaking the process into hierarchical steps, assembling smaller sub-parts first before combining them into the final construct.

Q4: Can I use raw PCR product in the assembly, or is gel purification necessary? You can use PCR product purified with a cleanup kit or even the raw PCR mix in an assembly to save time. However, using a cleanup kit without subsequent gel purification may result in more false positives from the PCR template plasmid. Gel purification provides the highest assurance of fragment size and purity, leading to fewer background colonies, but it does involve more handling and potential DNA loss [34]. Treating the PCR product with DpnI (if the template was a dam+ E. coli plasmid) can help reduce background without the need for gel extraction.

Ligase Cycling Reaction (LCR) and Polymerase Cycling Assembly (PCA) for Oligo Pool Assembly

For researchers in synthetic biology and drug development, the construction of large, high-fidelity DNA constructs from oligonucleotide pools is a fundamental process. Two powerful in vitro techniques for this purpose are Ligase Cycling Reaction (LCR) and Polymerase Cycling Assembly (PCA). LCR is a scarless, efficient method that assembles plasmids from DNA fragments using bridging oligos (BOs) and a thermal process of denaturation, annealing, and ligation [40]. PCA, also known as assembly PCR, assembles short oligonucleotides into kilobase-sized DNA fragments using overlapping ssDNA oligos and one to three rounds of PCR [41] [42]. Both methods enable the construction of gene-length fragments without template dependency, facilitating the creation of synthetic genes, metabolic pathways, and regulatory elements for therapeutic applications [41]. The selection between LCR and PCA typically depends on project-specific requirements regarding construct length, desired fidelity, and available laboratory resources.

Technical Comparison: LCR vs. PCA

Understanding the operational parameters and performance characteristics of LCR and PCA is crucial for selecting the appropriate method for a specific research goal. The table below provides a detailed technical comparison.

Table 1: Technical comparison between LCR and PCA

| Parameter | Ligase Cycling Reaction (LCR) | Polymerase Cycling Assembly (PCA) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Mechanism | Uses thermostable ligase and bridging oligos (BOs) to join DNA fragments [40]. | Uses DNA polymerase to extend overlapping single-stranded oligonucleotides [41] [42]. |

| Typical Construct Size | Efficient for 500 bp to 10,000 bp assemblies [42]. | Efficient for 200 bp to 1,000 bp assemblies [42]. |

| Key Steps | Denaturation, annealing, and ligation cycling [40]. | (1) Gene assembly via overlapping oligos, (2) Amplification with terminal primers [41]. |

| Critical Success Factors | Melting temperature ((T_m)) of BOs; avoidance of secondary structures [40]. | Optimization of PCR conditions; oligo length and overlap design [41]. |

| Fidelity & Error Correction | Fidelity depends on input oligonucleotide quality; may require separate error correction [42]. | Often incorporates error correction (e.g., using enzymes like CorrectASE or Authenticase) after assembly [41]. |

| Reported Success Rates | High efficiency reported with optimized protocols [40]. | ~25% (1 in 4 clones) without screening; up to ~80% (4 in 5) with phenotypic screening [41]. |

| Primary Advantages | Scarless assembly; high efficiency for multi-fragment plasmid construction [40]. | Protocol speed (2-3 days); template-independent synthesis [41]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

LCR Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Common issues and solutions for Ligase Cycling Reaction

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Few or no assembled products | Suboptimal Bridging Oligo (BO) design | Design BOs with appropriate and uniform melting temperatures. Avoid BOs with high molecular crosstalk [40]. |

| Inhibitory secondary structures | Avoid additives like DMSO and betaine, which can negatively impact LCR efficiency [40]. | |

| Inefficient ligation | Optimize experimental parameters: annealing temperature, ligation temperature, and BO-melting temperature [40]. | |

| Low assembly efficiency | Degraded reagents | Use fresh ligation buffer, as ATP degrades after multiple freeze-thaw cycles [43] [44]. |

| Low purity of starting oligonucleotides | Purify DNA fragments to remove contaminants such as salts and EDTA that can inhibit ligase activity [43] [44]. |

PCA Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Common issues and solutions for Polymerase Cycling Assembly

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No product or low yield | Suboptimal primer design | Verify primers are non-complementary and design for an annealing temperature 3-5°C below the primer (T_m) [45] [46]. Use software like DNAWorks for design [41]. |

| Incorrect annealing temperature | Perform a temperature gradient test, starting at 5°C below the calculated primer (T_m) [46]. | |

| Poor template quality | Use high-quality, purified oligonucleotides. For complex templates (GC-rich), use a polymerase with high processivity and consider GC enhancers [45] [46]. | |

| Sequence errors in final construct | Low-fidelity polymerase | Use a high-fidelity polymerase [46]. |

| Unbalanced dNTP concentrations | Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mixes to reduce PCR error rates [45] [46]. | |

| Errors from input oligonucleotides | Implement a dedicated error-correction step using enzyme cocktails like CorrectASE or Authenticase after the initial assembly [41]. | |

| Multiple or non-specific products | Low annealing temperature | Increase the annealing temperature to improve specificity [45] [46]. |

| Excess primer concentration | Optimize primer concentration, typically between 0.1–1 µM, to reduce primer-dimer formation [45]. | |

| Premature replication | Use a hot-start polymerase to prevent non-specific amplification during reaction setup [45] [46]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose between a one-step and a two-step PCA protocol? A one-step PCA protocol is faster and cheaper but is generally limited to shorter and simpler gene fragments. A two-step method, which includes an error correction step between the assembly and final amplification, is more accurate and performs better on longer gene fragments (over 1 kb) [41].

Q2: What is the most critical factor in designing Bridging Oligos (BOs) for LCR? The melting temperature ((T_m)) of the BOs is a critical success factor. BOs should be designed to have appropriate and uniform melting temperatures to ensure efficient and specific hybridization during the annealing phase. Molecular crosstalk between BOs must be minimized through careful in silico design [40].

Q3: Can these methods assemble sequences with high GC content or complex secondary structures? Yes, but they require optimization. Both LCR and PCA can struggle with such sequences. For PCA, using DNA polymerases with high processivity and adding PCR co-solvents or enhancers can help denature GC-rich templates and resolve secondary structures [45] [46]. For LCR, secondary structures in BOs or templates can be detrimental and should be avoided in the design phase [40].

Q4: How does the length of the starting oligonucleotides impact PCA success? Longer oligonucleotides can improve the success rate of PCA. For example, one study assembling a 1,698 bp hemagglutinin (HA) gene found that using 120-mer oligos provided a higher success rate (1 in 5 perfect clones) compared to using 60-mer oligos (1 in 6 perfect clones) [41].

Q5: What are the primary sources of error in these assembly methods, and how can they be mitigated? The final fidelity of constructs assembled by both LCR and PCA is highly dependent on the quality of the input oligonucleotides [42]. Errors from oligonucleotide synthesis are the primary concern. Mitigation strategies include using enzymatic error correction methods (e.g., MutS protein or T7 endonuclease) to remove mismatched duplexes after assembly [41] [42].

Workflow Visualization

Polymerase Cycling Assembly (PCA) Workflow

Ligase Cycling Reaction (LCR) Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of LCR and PCA relies on high-quality reagents. The table below lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 4: Key reagents and materials for LCR and PCA

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable DNA Ligase | Catalyzes the formation of phosphodiester bonds between adjacent nucleotides at high temperatures. | Essential for LCR [40]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurately extends DNA strands from primers with very low error rates (e.g., Q5, Phusion). | Critical for PCA to minimize mutations [41] [46]. |

| Bridging Oligos (BOs) | Short, complementary oligonucleotides that hybridize to the ends of adjacent DNA fragments, facilitating their ligation. | Required for LCR assembly [40]. |

| dNTP Mix | Provides the nucleotide building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for DNA synthesis by polymerase. | Essential for PCA and other PCR steps [45] [41]. |

| Error Correction Enzyme Mix | A cocktail of enzymes (e.g., CorrectASE, Authenticase) that identifies and degrades DNA heteroduplexes containing mismatches. | Used post-assembly in PCA to improve final construct fidelity [41]. |

| Competent E. coli Cells | Genetically engineered bacteria (e.g., recA- strains like NEB 10-beta) that can uptake foreign DNA for cloning and propagation. | Required for transforming assembled constructs after both LCR and PCA [44]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for a decentralized, high-throughput gene synthesis workflow. This method enables researchers to construct sequence-verified DNA constructs from pooled oligonucleotides in as little as four days, offering a significant reduction in time and cost compared to commercial gene synthesis services [47] [48]. The following FAQs and guides address common challenges in implementing this streamlined process for large-scale DNA assembly projects.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of this decentralized workflow over commercial gene synthesis? This approach offers three key benefits:

- Speed: Turnaround time is reduced from several weeks to just four days from receiving oligo pools to obtaining sequence-verified clones [47].

- Cost: It delivers a greater than three-fold reduction in raw DNA costs, with savings exceeding five-fold when all sequences in a pool are successfully assembled [47].

- Accessibility: It enables the successful assembly of sequences often rejected by commercial vendors, such as those with extreme GC content (>70% or <30%), long repeats, or complex secondary structures [47] [48].

Q2: My construct has high GC content and was flagged as "not synthesizable" by a vendor. Will this method work? Yes. The workflow has been experimentally validated to assemble genes with GC contents outside standard specifications, including sequences from S. griseofuscus (GC-rich, >70% GC) and S. ludwigii (AT-rich, <30% GC) [48]. The DAD-guided design and Golden Gate Assembly are less dependent on sequence homology, which helps overcome challenges associated with stable secondary structures [47] [48].

Q3: What is the maximum number of DNA fragments I can reliably assemble with this method? The workflow is highly robust for assemblies of up to 12 fragments, with success rates exceeding 80% for such constructs. While assemblies with more than 12 fragments are possible, they typically show a modest decline in efficiency. For example, a study successfully constructed 343 out of 458 attempted genes, with fragment numbers being a key factor in success [47] [48].