Microfluidics for Synthetic Biology: Advanced Tools for Biomanufacturing, Diagnostics, and Drug Development

This article explores the transformative integration of microfluidics and synthetic biology, a convergence driving breakthroughs in biomedical research and industrial bioprocesses.

Microfluidics for Synthetic Biology: Advanced Tools for Biomanufacturing, Diagnostics, and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of microfluidics and synthetic biology, a convergence driving breakthroughs in biomedical research and industrial bioprocesses. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it details how droplet-based and continuous-flow microfluidic platforms enable ultra-high-throughput screening, single-cell analysis, and precise biomolecule fabrication. The content covers foundational principles, diverse methodological applications—from enzyme evolution to organ-on-a-chip models—and provides practical solutions for common experimental challenges. By comparing microfluidic approaches to traditional methods and validating their enhanced performance, this review serves as a comprehensive guide for leveraging these powerful technologies to accelerate innovation in green biomanufacturing, therapeutic discovery, and precision medicine.

Microfluidics and Synthetic Biology: Principles, Synergies, and Core Advantages

Microfluidics is the science and technology of systems that process or manipulate small amounts of fluids (10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹⁸ liters), using channels with dimensions of tens to hundreds of micrometers [1]. The behavior of fluids at this microscale is fundamentally different from macroscale behavior, characterized by low Reynolds numbers, resulting in laminar flow where fluids flow in parallel streams without turbulence [2] [1]. This unique physical environment allows for high specificity of chemical and physical properties, leading to more uniform reaction conditions and higher-grade products [1]. The field has evolved from foundational discoveries in capillary action and fluid dynamics to sophisticated applications in inkjet printheads, DNA chips, and lab-on-a-chip technology [1].

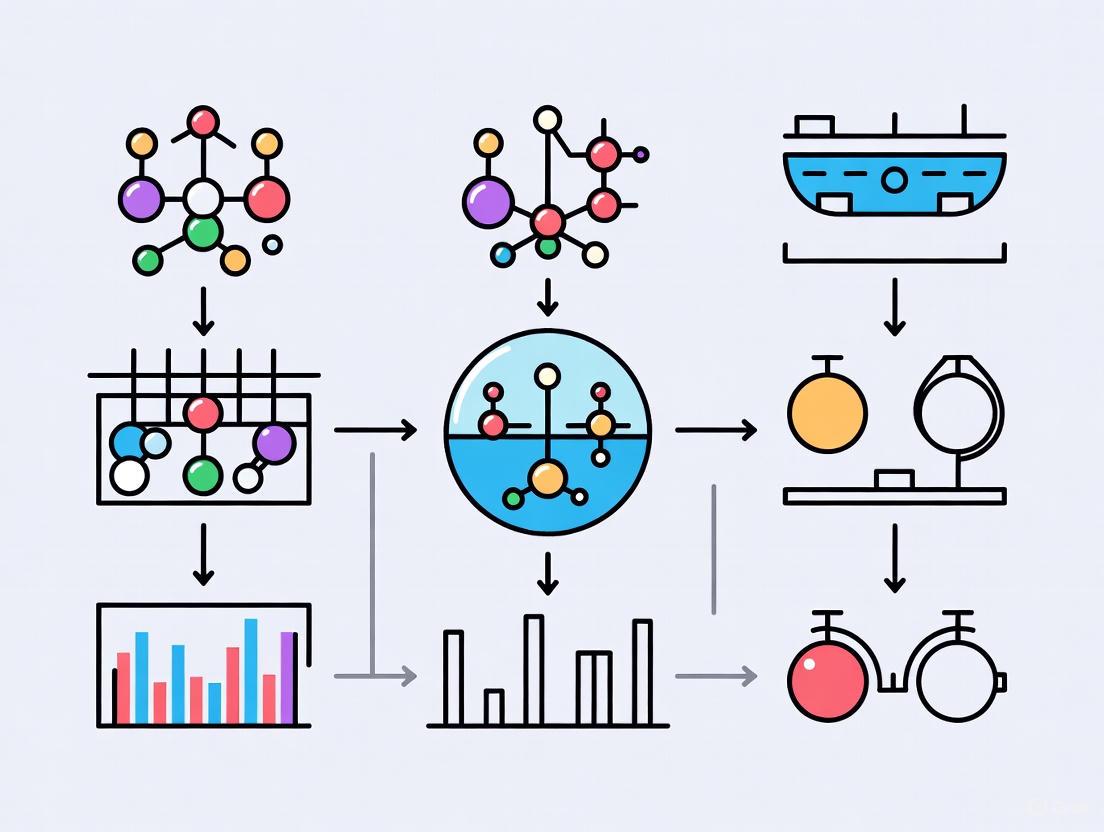

Synthetic biology, conversely, is an engineering discipline dedicated to designing and constructing novel biological systems and functions for useful purposes [3] [4]. It aims to create predictable and robust biological parts and systems, from genetic circuits to entire metabolic pathways, for applications ranging from drug development to sustainable biomaterial production [4]. A cornerstone methodology in synthetic biology is the iterative design-construct-test-analyze (DCTA) research cycle, which allows for the progressive refinement of biological systems [5].

The convergence of these two fields is natural and powerful. The inherent complexity of biological systems and the physical variations in biological behavior present significant challenges to synthetic biology [4]. Microfluidic technology addresses these challenges by providing tools for high-throughput, automated, and precise analysis and construction, thereby accelerating the entire synthetic biology research cycle [6] [5] [4]. By enabling the miniaturization of experiments, microfluidics reduces costs, time, and reagent consumption while increasing the resolution and accuracy of data collected from biological systems [5] [4].

Key Applications of Microfluidics in Synthetic Biology

Microfluidics enhances various aspects of synthetic biology, from fundamental cellular analysis to the construction of complex genetic programs. The table below summarizes the primary application areas where this technological convergence is making a significant impact.

Table 1: Key Application Areas of Microfluidics in Synthetic Biology

| Application Area | Key Function | Microfluidic Platform Examples | Impact on Synthetic Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell & Population Analysis | Long-term monitoring of gene expression and growth of individual cells in precisely controlled environments [2]. | Microchemostats [2], Microfluidic arrays [4] | Enables study of population heterogeneity, gene expression noise, and dynamics of genetic oscillators unavailable to bulk measurement techniques like flow cytometry [2]. |

| Gene Expression & Regulation Dynamics | High-resolution profiling of cellular responses to rapid environmental changes and dynamic gene regulation [4]. | Droplet-based systems [4], Array-based devices with diffusive mixing [4] | Reveals distinct dynamics in gene expression and facilitates the functional assessment of synthetic biological parts under various stimuli [4]. |

| Cell-Free Synthetic Biology | Implementation of multi-step, long-term, and continuous cell-free reactions in miniature volumes [3]. | Microfluidic chemostats [3], Droplet compartments [3] | Allows for steady-state transcription-translation reactions, high-throughput characterization of biomolecular components, and the construction of artificial cells [3]. |

| Automated DNA Assembly & Construction | Automated assembly of DNA molecules from smaller fragments and subsequent transformation into hosts [5]. | 2D microvalve arrays [5], Platforms for Gibson Assembly & Isothermal Hierarchical DNA Construction (IHDC) [5] | Integrates and automates the "construct" phase of the DCTA cycle, reducing assembly time and labor while increasing throughput and reliability [5]. |

| Whole-Cell Analysis & Biosensing | On-chip functional assays, including growth, induction, and metabolic output analysis [5] [4]. | Integrated platforms with environmental control and detection [5] [4] | Provides a closed-loop system for the "test" and "analyze" phases of synthetic biology, enabling rapid debugging and reprogramming of biological systems [5]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Isothermal Hierarchical DNA Construction (IHDC) on a Microfluidic Platform

This protocol describes a method for automated, hierarchical assembly of long DNA molecules from shorter oligonucleotides, optimized for a programmable microfluidic platform using 2D microvalve array technology [5].

I. Principle IHDC is an isothermal DNA assembly method derived from Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) [5]. It takes two overlapping double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) fragments as input and produces an elongated dsDNA output. The method uses recombinase proteins to incorporate primers between the strands, which are then polymerase-elongated to produce single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). The overlapping ssDNA molecules hybridize, priming each other for overlap extension elongation to form dsDNA, which is subsequently amplified isothermally [5].

II. Equipment and Reagents

- Programmable Microfluidic Platform: Equipped with a 2D microvalve array chip, electronic pneumatic control system, and temperature regulation capable of maintaining isothermal conditions (e.g., 37°C) [5].

- Software: PR-PR programming language for laboratory automation or equivalent [5].

- IHDC Reagent Mix: Contains recombinase, polymerase, single-stranded DNA-binding protein, nucleotides, and cofactors in an appropriate buffer [5].

- DNA Inputs: Synthetic oligonucleotides or DNA fragments with designed overlapping regions.

- Elution Buffer: Low-EDTA TE buffer or nuclease-free water.

III. Procedure

- Chip Priming: Use the software to run a priming protocol, rinsing the microvalves with a cleansing solution to prevent cross-contamination [5].

- Reagent Loading: Assign and load reagents into the chip's designated input wells:

- Well A: IHDC Reagent Mix

- Well B: DNA Fragment 1

- Well C: DNA Fragment 2

- Well D: Elution Buffer [5]

- Reaction Execution:

- The software executes a transfer command, routing and mixing precise volumes (e.g., 150 nL per transfer) of the DNA fragments and reagent mix into a reaction chamber [5].

- The temperature control system maintains the chip at a constant 37°C for the reaction duration (15 minutes per hierarchical assembly step) [5].

- The process is repeated for each hierarchical step, with intermediate products being moved and mixed with new fragments according to the pre-designed construction tree [5].

- Product Recovery: Upon completion, the final assembled DNA product is transferred to an output well and eluted for collection [5].

IV. Analysis

- Analyze the intermediate and final DNA products using off-chip agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the size and yield of the constructs [5].

- The assembled DNA can be integrated into a vector via on-chip Gibson Assembly for subsequent transformation [5].

The workflow for this automated DNA construction is illustrated below.

Protocol: Single-Cell Microchemostat Cultivation and Imaging

This protocol outlines the use of a microfluidic "microchemostat" device for long-term cultivation and high-resolution imaging of microbial cells, such as E. coli or S. cerevisiae, under dynamic environmental control [2].

I. Principle Microchemostat devices are designed with microscopic traps to physically confine individual cells while allowing fresh medium to perfuse continuously. This setup enables precise control over the cells' chemical environment and prevents the population from overgrowing the field of view. Combined with automated, high-resolution microscopy, it allows for the tracking of gene expression and morphological changes in single cells over multiple generations [2].

II. Equipment and Reagents

- Fabricated PDMS Microchemostat Device: Bonded to a glass coverslip, featuring an array of cell traps and integrated channels for medium and inducer inflow [2].

- Microscope System: Inverted microscope fully automated for stage movement, focus, and equipped with phase-contrast and fluorescence (e.g., GFP, RFP) capabilities. A sensitive CCD or sCMOS camera is required [2].

- Environmental Control: System for maintaining the chip at a constant temperature (e.g., 30°C for yeast).

- Medium Reservoirs: Source reservoirs for different media and inducers, connected to the chip via tubing. A system for modulating hydrostatic pressure or using syringe pumps is needed to control medium mixing and flow rates [2].

- Cell Sample: Late-log phase culture of the engineered microorganism.

III. Procedure

- Device Priming: Flush all channels of the microfluidic device with sterile, cell-free medium to remove bubbles and condition the surfaces [2].

- Cell Loading: Introduce the cell suspension into the device at a high flow rate to load cells into the traps. Subsequently, reduce the flow to the desired rate for the long-term experiment [2].

- Environmental Programming: Use the pressure modulation system to create dynamic environments. For example, to generate a time-varying inducer concentration, adjust the mixing ratio between a reservoir with plain medium and one with inducer [2].

- Automated Time-Lapse Imaging: Program the microscope to acquire images at regular intervals:

- Phase-contrast images every 1 minute to track cell growth and position.

- Fluorescence images every 5 minutes to monitor gene expression dynamics, minimizing phototoxicity [2].

- The microscope hardware automatically moves between multiple stage positions to image different chambers on the chip.

- Experiment Duration: Run the experiment for the desired period (typically 24-72 hours), ensuring medium reservoirs do not run dry [2].

IV. Data Analysis

- Use automated cell-tracking software to segment cells in each frame and link them across time, reconstructing lineage trees.

- Extract quantitative data for each cell over time, including size, morphology, and fluorescence intensity.

- Analyze data to reveal population heterogeneity, dynamic responses to environmental changes, and gene expression noise [2].

The experimental setup and workflow for microchemostat analysis are depicted below.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key reagents and materials essential for executing the microfluidics-based synthetic biology protocols described above.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microfluidic Synthetic Biology

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Application/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Elastomeric polymer used for rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices via soft lithography; it is gas-permeable and optically clear [3]. | Standard material for building microchemostats and other chip designs for cell culture [2] [3]. |

| Cell-Free Transcription-Translation System | A crude cell lysate (e.g., from E. coli) or a reconstituted system (e.g., PURE) containing the necessary biochemical machinery for protein synthesis from DNA templates [3]. | Used in microfluidic chemostats for continuous, steady-state gene expression and for building artificial cells [3]. |

| Isothermal Assembly Mix (IHDC or Gibson) | A proprietary enzymatic mix containing recombinase, polymerase, and exonuclease for assembling overlapping DNA fragments in a single, isothermal reaction [5]. | Critical for automated, on-chip DNA construction of genetic circuits and combinatorial libraries [5]. |

| Fluorescent Proteins and Reporters | Genetically encoded proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP) whose expression is linked to promoter activity, serving as quantitative reporters of gene expression [2] [4]. | Enables real-time, non-invasive monitoring of synthetic circuit dynamics in single cells within microfluidic devices [2]. |

| Engineered Biological Cells | Model organisms (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae) genetically modified to contain the synthetic genetic circuit or pathway under investigation. | The core subject of study; microfluidics provides a controlled environment to probe their function [2] [5]. |

Application Note: Harnessing Laminar Flow for Concentration Gradients

Physical Principle and Quantitative Profile

In microfluidic systems, the flow of fluids is predominantly laminar, characterized by parallel layers of fluid moving without mixing except by molecular diffusion [7]. This behavior is governed by a low Reynolds number (Re), a dimensionless quantity representing the ratio of inertial to viscous forces [7] [8].

- Reynolds Number Calculation:

Re = (ρ v L) / μρ= fluid density (kg/m³)v= fluid velocity (m/s)L= characteristic length of the channel, e.g., diameter (m)μ= dynamic viscosity of the fluid (Pa·s) [9]

- Flow Regime:

This laminar flow property allows two or more streams to flow side-by-side within a single microchannel, forming a stable interface where molecules exchange only by diffusion [8]. The predictable nature of this diffusion enables the creation of precise, stable concentration gradients, which are invaluable for studying cellular responses, chemical reactions, and gradient-sensitive biological processes [8].

Experimental Protocol: Generating a Linear Chemical Gradient

Objective: To create a stable, linear concentration gradient of a chemical across a microchannel for cell culture or chemical synthesis studies.

Materials:

- Microfluidic Chip: PDMS-based device with a "Y" or "tree" shaped channel network [7].

- Flow Control System: Pressure-driven pump (e.g., OB1 Pressure Controller) or volumetric syringe pumps [8].

- Reagents: Aqueous solution of your molecule of interest (e.g., a fluorescent dye for visualization) and a buffer solution.

- Analysis Equipment: Inverted microscope coupled with a CCD camera.

Procedure:

- Chip Priming: Introduce the buffer solution into the entire microfluidic network to remove air bubbles and ensure all channels are filled.

- Flow Rate Calculation: Based on your channel dimensions and desired diffusion profile, calculate the flow rate required to achieve a low Reynolds number (typically <<100). For a pressure controller, the relationship is

Flow rate = Pressure / Resistance, where resistance depends on channel geometry and fluid viscosity [8]. - Solution Loading: Load the molecule-of-interest solution into one inlet reservoir and the buffer solution into the other.

- Flow Initiation: Activate the flow control system to drive both fluids into the main channel at identical, low flow rates (e.g., 0.1 - 10 µL/min, depending on channel size). The fluids will flow side-by-side without turbulent mixing [8].

- Gradient Establishment: Allow the flow to stabilize for approximately 5-10 minutes. A steady-state interface will form between the two streams.

- Diffusion and Imaging: As the streams flow parallel, molecules from the solute stream will diffuse across the fluidic interface into the buffer stream, establishing a concentration gradient perpendicular to the flow direction. Capture images of the gradient using fluorescence microscopy.

- Validation: Quantify the gradient profile by measuring fluorescence intensity across the width of the channel.

Troubleshooting:

- Unstable Interface: Check for inconsistencies in flow rates from the two inlets. Ensure your pump provides stable, pulse-free flow.

- No Gradient Formed: The flow rate may be too high, reducing the time available for diffusion. Decrease the flow rate to increase the residence time of the fluid in the channel.

Application Note: Diffusion-Controlled Reactions in Cell-Free Synthetic Biology

Physical Principle and Quantitative Analysis

Molecular diffusion is the net movement of molecules from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration due to random thermal motion [10]. In microfluidics, the absence of turbulence in laminar flow makes diffusion the primary mixing mechanism [8]. The timescale and extent of diffusion are critical for initiating and controlling biochemical reactions in confined spaces, such as in artificial cells or droplet-based reactors used in cell-free synthetic biology [3].

- Fick's First Law of Diffusion:

J = -D (dC/dx)J= diffusion flux (amount of substance per unit area per unit time)D= diffusion coefficient (m²/s)dC/dx= concentration gradient (mol/m⁴) [10]

- Diffusion Coefficients (Examples):

- Water (self-diffusion) at 25°C: 2.299 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s [10]

- Small molecules (e.g., glucose in water): ~10⁻⁹ m²/s

- Proteins (e.g., BSA in water): ~10⁻¹⁰ to 10⁻¹¹ m²/s

The following table summarizes key parameters for diffusion-based mixing in microfluidics:

Table 1: Key Parameters for Diffusion-Based Mixing in Microfluidics

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range in Microfluidics | Impact on Mixing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Coefficient | D | 10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹¹ m²/s | Larger D enables faster mixing. |

| Channel Width | w | 50 - 500 µm | Smaller width reduces mixing time. |

| Flow Velocity | v | 0.1 - 10 mm/s | Lower velocity increases residence time. |

| Characteristic Mixing Time | t | t ~ w² / D | Time required for significant mixing. |

Experimental Protocol: Initiating Cell-Free Protein Synthesis with Diffusive Reagent Mixing

Objective: To use controlled diffusion at a microfluidic interface to initiate a cell-free transcription-translation (TX-TL) reaction for protein synthesis [3].

Materials:

- Microfluidic Device: A chip featuring a chemostat or a multi-inlet channel for sustained reactions [3].

- Cell-Free System: Commercially available E. coli lysate-based or PURE (Protein synthesis Using Recombinant Elements) system [3].

- Reagents: DNA template encoding the protein of interest, NTPs, amino acids, and energy regeneration system components.

- Precision Flow Control System: Pressure controller capable of maintaining stable, low flow rates.

Procedure:

- Reagent Preparation: Reconstitute the cell-free master mix according to the manufacturer's protocol, but omit the DNA template. Keep the mix on ice to prevent premature reaction initiation.

- Template Preparation: Prepare a separate solution containing the DNA template.

- Device and Flow Setup: Prime the microfluidic device with a neutral buffer. Use the flow control system to establish stable, side-by-side laminar flow of the DNA template solution and the cell-free master mix.

- Reaction Initiation: As the two streams flow adjacently, DNA templates will diffuse from their stream into the master mix stream. Upon reaching a critical concentration within the master mix, the TX-TL reaction is initiated, leading to protein synthesis.

- Continuous Operation: For longer reactions, use a chemostat design where fresh reagents are continuously supplied, and waste products are removed, maintaining the reaction for hours [3].

- Output Monitoring: Monitor protein synthesis in real-time if using a fluorescent protein reporter (e.g., GFP). Collect output samples from the device outlet for further analysis (e.g., SDS-PAGE).

Troubleshooting:

- Low Protein Yield: Ensure the flow rates are slow enough to allow sufficient DNA diffusion. Check the activity of the cell-free system.

- Rapid Reaction Exhaustion: In a continuous-flow setup, optimize the flow rate to balance reagent replenishment and product dilution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers employing microfluidics in synthetic biology, the choice of materials and reagents is critical. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microfluidics in Synthetic Biology

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [7] [3] | Elastomeric polymer for rapid device prototyping via soft lithography. Ideal for cell culture due to gas permeability. | Highly permeable to water vapor and organic solvents; can absorb small hydrophobic molecules. |

| Cell-Free System (Lysate or PURE) [3] | Extracted cellular machinery for in vitro transcription and translation outside of living cells. | Lysate-based systems are complex but powerful; PURE systems are defined but more expensive. |

| Pressure-Driven Flow Controller [8] | Provides precise, pulse-free fluid actuation by applying air pressure to fluid reservoirs. | Offers faster response and better stability for complex networks compared to some syringe pumps. |

| Fluorinated Oil with Surfactants | Continuous oil phase for droplet-based microfluidics; surfactants stabilize aqueous droplets to prevent coalescence. | Biocompatibility with the biological reaction inside droplets must be confirmed. |

| Surface Passivation Agents (e.g., Pluronic F-127, BSA) | Coat channel walls to prevent nonspecific adsorption of proteins or DNA. | Essential for maintaining the activity of cell-free systems and avoiding clogging. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Laminar Flow Gradient Generator Workflow

Microfluidic System for Cell-Free Synthesis

Microfluidics, the science and technology of manipulating fluids at the micron scale (one millionth of a meter), has emerged as a transformative tool at the intersection of engineering, biology, and chemistry [11]. This technology enables precise control of liquids within channels thinner than a strand of hair, allowing researchers to conduct experiments and diagnostics using minimal volumes of liquids, which leads to significant savings in cost, time, and resources [12]. The foundation of microfluidics lies in miniaturization and integration, where complex laboratory functions such as mixing, separation, and detection can be performed within compact devices known as "lab-on-a-chip" systems [12]. For the field of synthetic biology—which involves the design and modification of biological systems for specific functions by integrating disciplines like engineering, genetics, and computer science—microfluidics offers a powerful solution to longstanding challenges [13]. Despite the significant impact of synthetic biology in addressing global challenges across diverse domains, the field has faced difficulties in achieving precise, dynamic, and high-throughput manipulation of biological processes [13]. Microfluidics addresses these limitations by enabling controlled fluid handling at the microscale, which offers lower reagent consumption, faster analysis of biochemical reactions, automation, and high-throughput screening capabilities [13].

The integration of microfluidics with host organisms—including bacterial cells, yeast, fungi, animal cells, and cell-free systems—has proven instrumental in advancing synthetic biology applications [13]. By creating synthetic genetic circuits, pathways, and organisms within controlled environments, microfluidic platforms have become essential tools for understanding and engineering biological systems [13]. The technology's ability to provide excellent spatiotemporal control over the cellular microenvironment, coupled with short diffusion path lengths and operation at low volumes, increases sensitivity, lowers the Limit of Detection (LoD), and improves time-to-result of analytical assays [14]. These advantages are particularly valuable in bio-engineering applications where traditional methods face limitations in throughput, cost-effectiveness, and reproducibility. As microfluidics continues to evolve, it is positioned to play a central role in shaping modern science and technology, with the global microfluidics market projected to grow from USD 36.2 Billion in 2024 to approximately USD 102.9 Billion by 2033, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.3% [12].

Microfluidic Advantages Over Conventional Methods

Microfluidics provides distinct advantages over conventional bio-engineering methods across three critical parameters: throughput, cost, and reproducibility. The technology's fundamental characteristics directly address limitations that have historically constrained synthetic biology and related fields.

Throughput Enhancement

Traditional macroscopic systems face significant challenges in achieving high-throughput experimentation due to manual handling requirements, slow processing times, and substantial reagent volumes. Microfluidics overcomes these limitations through parallelization and miniaturization. The ability to process numerous samples simultaneously in microfluidic devices dramatically increases experimental throughput [13]. For instance, in sperm selection for assisted reproduction, researchers have identified parallelization as a key solution to overcome low throughput in current microfluidic sperm selection chips [15]. Similarly, in CAR-T cell therapy manufacturing, microfluidic technology enables high-throughput quality control testing, which is crucial for monitoring critical quality attributes (CQAs) of the drug product [14]. The automation capabilities of microfluidic systems further enhance throughput by reducing manual intervention and enabling continuous operation.

Cost Reduction

The economic impact of microfluidics stems from multiple factors that collectively reduce the overall cost of bio-engineering processes. By operating at the microscale, these systems significantly minimize reagent and sample consumption, leading to substantial cost savings [13] [14]. This reduction in resource usage is particularly valuable when working with expensive reagents or rare biological samples. In the context of CAR-T cell therapy manufacturing, where the current cost of goods (COGs) includes 32% attributed to quality control testing alone, the implementation of microfluidic analytical methods could generate significant savings [14]. The miniaturized nature of microfluidic devices also reduces material costs for device fabrication, especially when using polymers like PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane), which is not only cost-effective but also offers excellent biochemical performance and biocompatibility [11].

Improved Reproducibility

The precise fluid control achievable in microfluidic systems directly enhances experimental reproducibility—a critical requirement in both research and clinical applications. The laminar flow regime dominant at the microscale (characterized by low Reynolds numbers, typically Re < 2000) enables highly predictable fluid behavior [11]. This flow characteristic, where viscous forces dominate over inertial forces, allows for exact manipulation of fluids and cells, reducing experimental variability [13]. In applications such as droplet-based microfluidics, highly monodispersed alginate beads can be consistently generated, demonstrating the technology's capability for reproducible particle synthesis [16]. The automation potential of microfluidic systems further minimizes human error, contributing to more reliable and consistent outcomes across experiments [14].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Conventional Methods vs. Microfluidic Approaches

| Parameter | Conventional Methods | Microfluidic Approaches | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reagent Consumption | Milliliter to liter ranges | Microliter to nanoliter ranges | 100-1000x reduction [14] |

| Analysis Time | Hours to days | Minutes to hours | 3-10x acceleration [14] |

| Experimental Throughput | Limited by manual processing | High through parallelization | 10-100x increase [13] |

| Device Footprint | Benchtop equipment requiring significant space | Compact "lab-on-a-chip" systems | 5-20x reduction [12] |

| Limit of Detection | Micromolar to nanomolar | Nanomolar to picomolar | 100-1000x improvement [14] |

Application Note 1: Microfluidic Quality Control in CAR-T Cell Therapy

Background and Significance

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies have revolutionized the treatment of hematological cancers, achieving high remission rates in previously unresponsive patients [14]. However, the prohibitive cost of approximately USD 500k per treatment restricts accessibility for the broader patient population [14]. The complex and often labor-intensive manufacturing process itself accounts for USD 170-220k per batch, with quality control (QC) comprising approximately 32% of the total cost of goods (COGs) [14]. The current QC workflow for CAR-T cell manufacturing relies on multiple analytical techniques, including flow cytometry, microscopy, impedance-based real-time cell analysis, qPCR, and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), which require trained scientists to operate and analyze results [14]. These conventional methods are not only time-consuming and expensive but also face challenges in standardization and reproducibility. Microfluidic technology offers a transformative approach to QC testing by integrating multiple analytical assays into automated devices with integrated readouts, thereby decreasing complexity while improving sensitivity, lowering the Limit of Detection (LoD), and enhancing time-to-result of analytical assays [14].

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To implement a microfluidic-based quality control platform for monitoring Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) in CAR-T cell manufacturing, specifically focusing on identity, purity, and potency assessments.

Materials:

- OB1 pressure & flow controller (Elveflow) or equivalent microfluidic pressure control system

- Microfluidic device with integrated cell capture regions

- Cell culture media appropriate for T-cell maintenance

- CAR-T cell samples at various manufacturing stages

- Target cancer cell lines for cytotoxicity assessment

- Fluorescently labeled antibodies for CD3, CD4, CD8, and CAR-specific markers

- Viability dyes (e.g., propidium iodide)

- Cytokine detection reagents

Procedure:

Device Priming and Preparation:

- Connect the microfluidic device to the pressure controller following manufacturer's instructions.

- Prime the system with appropriate cell culture media, ensuring no air bubbles remain in the microchannels [16].

- Set the flow rate to 10-50 μL/min using the pressure controller and flow sensor feedback mechanism [16].

Sample Loading and Cell Capture:

- Introduce the CAR-T cell sample (100-500 μL volume) into the injection port.

- Utilize hydrodynamic focusing or surface capture methodologies to isolate individual cells within the microfluidic device [14].

- Allow cells to settle for 5-10 minutes under minimal flow conditions (1-5 μL/min).

Multiparameter Analysis:

- Viability Assessment: Introduce viability dye through a separate inlet and monitor fluorescence to distinguish live/dead cells.

- Phenotypic Characterization: Perfuse fluorescently labeled antibodies for CD3, CD4, CD8, and CAR-specific markers through the system.

- Cytotoxicity Assessment: Introduce target cancer cells at specific effector-to-target ratios and monitor cell death in real-time using impedance-based measurements or fluorescent markers [14].

Data Collection and Analysis:

- Acquire time-lapse images or continuous impedance measurements for 2-24 hours.

- Use integrated software to quantify fluorescence intensity, cell count, and cytotoxicity metrics.

- Calculate critical quality attributes including viability percentage, CAR+ expression, and specific cytotoxicity.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If air bubbles form in the system, increase pressure briefly to flush them out or use dedicated bubble traps [16].

- For inconsistent cell capture, optimize surface functionalization or adjust flow rates to improve efficiency.

- If signal detection is weak, confirm reagent activity and consider increasing incubation time or concentration.

Results and Interpretation

The microfluidic QC platform enables simultaneous assessment of multiple CQAs from a single miniaturized device. Typical results should include:

- Viability: >70% for manufacturing process continuity [14]

- Identity: CAR+ expression >20% with precise cell counting and dosage determination [14]

- Potency: Specific cytotoxicity >10% against target cells, with dose-response relationship [14]

The integration of multiple analytical functions into a single microfluidic device significantly reduces the time-to-result from several days to hours while cutting reagent consumption by 10-100x compared to conventional methods. The automated operation minimizes operator-induced variability, enhancing reproducibility across batches. The continuous monitoring capability provides dynamic information about cell function that is not available from endpoint assays, offering richer data for manufacturing decisions.

Diagram 1: CAR-T Cell QC Workflow

Application Note 2: Microfluidic Sperm Selection for Assisted Reproduction

Background and Significance

Infertility treatment represents a significant challenge in healthcare, with obtaining functional sperm cells being the first crucial step to address male infertility [15]. Conventional sperm selection methods, such as wash and swim-up or density gradient centrifugation, often cause damage to sperm DNA and fail to efficiently isolate the most viable spermatozoa [15]. These limitations have prompted the development of advanced selection techniques, with microfluidics emerging as a promising solution. Microfluidic platforms leverage the unique physics of fluid behavior at the microscale, including laminar flow and low Reynolds numbers, to provide unprecedented opportunities for sperm selection [15]. Previous studies have demonstrated that microfluidic platforms can offer a novel approach to this challenge, with researchers attacking the problem from multiple angles using various sperm properties including self-motility, boundary following, rheotaxis, chemotaxis, and thermotaxis [15]. The technology enables the selection of sperm based on their physiological function and morphological integrity without subjecting them to damaging centrifugal forces, potentially maximizing the chance for successful pregnancy in assisted reproductive technology (ART) laboratories.

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To implement a microfluidic sperm selection protocol based on rheotaxis and chemotaxis properties for isolating highly motile and functional sperm for assisted reproduction.

Materials:

- Pressure-driven flow controller (e.g., Elveflow OB1)

- Custom-designed microfluidic sperm selection device

- Semen sample prepared by standard liquefaction procedure

- Sperm washing medium (commercial preparation)

- Sperm capacitation medium

- Chemoattractant solution (e.g., progesterone)

- Incubator maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2

- Phase-contrast or differential interference contrast microscope

Procedure:

Device Preparation:

- Sterilize the microfluidic device using UV light or appropriate sterilizing agents.

- Connect the device to the pressure controller and prime with sperm washing medium.

- Set up a chemotactic gradient by pre-loading one reservoir with chemoattractant solution.

Sample Processing:

- Introduce the prepared semen sample into the input reservoir.

- Apply precise pressure control (0.1-2 psi) to create a gradual flow gradient within the microchannels [15].

- Allow sperm to migrate through the device for 15-30 minutes under controlled temperature conditions.

Sperm Selection Mechanism:

- Utilize rheotaxis (the ability of sperm to swim against fluid flow) as a primary selection parameter [15].

- Incorporate chemotaxis (guidance by chemical gradients) to enhance selection of functional sperm [15].

- Exploit boundary following behavior where the most motile sperm tend to swim along channel walls.

Collection and Assessment:

- Collect the selected sperm population from the output reservoir.

- Assess sperm parameters including motility, morphology, and DNA fragmentation.

- Compare with conventionally prepared samples to validate selection efficiency.

Validation Methods:

- Computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA) for motility parameters

- Sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA) for DNA fragmentation

- Morphological assessment using strict Kruger criteria

- Clinical outcomes including fertilization rate and embryo quality

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If sperm recovery is low, optimize flow rates to balance selection stringency and yield.

- For inconsistent chemotactic response, verify chemoattractant activity and gradient stability.

- If device clogging occurs, pre-filter semen samples or adjust channel dimensions.

Results and Interpretation

Microfluidic sperm selection typically demonstrates significant improvements over conventional methods:

- Motility Enhancement: 2-3 fold increase in progressive motile sperm compared to initial sample [15]

- DNA Integrity: Significant reduction in DNA fragmentation index compared to conventional methods [15]

- Morphological Selection: Higher percentage of morphologically normal sperm in selected population

The exploitation of rheotaxis and chemotaxis in microfluidic devices enables selection of sperm based on their functional competence rather than merely density or swim-up capability. This functional selection correlates with improved fertilization outcomes and embryo quality. The parallelization of microfluidic devices addresses throughput limitations, making the technology suitable for clinical application where sufficient sperm numbers are required for procedures like in vitro fertilization (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). Future development directions include the integration of microfluidic sperm selection with subsequent ART steps toward fully integrated start-to-finish assisted reproductive technology systems [15].

Application Note 3: Droplet Microfluidics for High-Throughput Screening

Background and Significance

Droplet-based microfluidics has emerged as a powerful platform for high-throughput screening applications in synthetic biology and drug discovery. This technology enables the generation and manipulation of picoliter to nanoliter volume droplets, functioning as discrete microreactors for biological assays [16]. The generation of highly monodispersed droplets offers tremendous advantages including better control over small volumes of fluid, enhanced mixing, and high throughput experiments [16]. In the context of synthetic biology, droplet microfluidics facilitates the rapid testing of genetic circuits, enzyme variants, and metabolic pathways encapsulated within isolated compartments. Similarly, for drug discovery, particularly in antifungal screening, single spore encapsulation in droplets provides a breakthrough approach for fungicide discovery [16]. The ability to create millions of discrete reaction vessels in a short time dramatically accelerates the design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycle in synthetic biology, addressing a critical bottleneck in conventional approaches where throughput is limited by manual handling, large reagent volumes, and slow processing times.

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To implement a droplet microfluidics platform for high-throughput screening of synthetic genetic circuits in yeast, enabling rapid characterization of circuit behavior under different conditions.

Materials:

- Pressure-driven droplet generation system (e.g., Elveflow OB1 with microfluidic droplet chip)

- Water-in-oil surfactant solution (e.g., 2% fluorosurfactant in HFE-7500)

- Aqueous phase containing yeast cells expressing genetic circuits

- Fluorescence-activated droplet sorting (FADS) system or equivalent

- Collection reservoirs for sorted droplets

- Incubation system for droplet culture

- Microscopy setup for droplet monitoring

Procedure:

Droplet Generation:

- Set up the microfluidic droplet device with appropriate surface treatment for stable droplet formation.

- Connect oil and aqueous phase reservoirs to the pressure controller.

- Pre-pressurize the system to 0.5-2 psi to establish stable flows without droplets [16].

- Adjust oil and aqueous phase pressure ratios to generate monodisperse droplets of 50-100 μm diameter.

- Collect emerging droplets in a storage reservoir for incubation.

Droplet Incubation and Monitoring:

- Transfer droplets to an incubation chamber maintained at appropriate temperature (30°C for yeast).

- Monitor droplet contents over time using time-lapse microscopy.

- Measure fluorescence output from genetic circuits at regular intervals.

Droplet Sorting:

- Set up fluorescence detection threshold based on desired circuit behavior.

- Implement sorting parameters in the FADS system to isolate droplets of interest.

- Collect sorted droplets in separate reservoirs for downstream analysis.

Downstream Analysis:

- Break sorted droplets to recover biological content.

- Plate cells on solid media for colony formation or proceed to molecular analysis.

- Sequence genetic circuits from sorted populations to validate design principles.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If droplet size is inconsistent, check for pressure fluctuations and ensure surfactant is properly dissolved in oil phase.

- For unstable droplets, verify surface treatment of device and adjust surfactant concentration.

- If sorting efficiency is low, calibrate detection system and ensure proper droplet spacing.

Results and Interpretation

A typical droplet microfluidics screening experiment should yield:

- Droplet Generation Rate: 100-10,000 droplets per second depending on device design and flow parameters [16]

- Droplet Uniformity: Coefficient of variation <5% for diameter, ensuring consistent reaction volumes

- Encapsulation Efficiency: Single cell encapsulation following Poisson distribution statistics

- Sorting Purity: >90% recovery of desired variants in the sorted population

The encapsulation of individual cells or reactions in picoliter droplets reduces reagent consumption by 100-1000x compared to conventional microtiter plate-based screening. The high generation rate enables testing of library sizes that would be impractical with conventional methods, dramatically expanding the exploration of design space in synthetic biology. The compartmentalization prevents cross-contamination between reactions and enables the detection of weak signals that would be diluted in bulk measurements. The integration of droplet generation, incubation, and sorting in automated platforms significantly reduces hands-on time and improves reproducibility across experiments. Applications extend beyond genetic circuit characterization to include enzyme evolution, single-cell analysis, and combinatorial drug screening, demonstrating the versatility of droplet microfluidics as a platform technology for bio-engineering.

Diagram 2: Droplet Screening Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of microfluidic applications in synthetic biology requires specific materials and reagents optimized for microscale operations. The selection of appropriate components is critical for achieving reliable and reproducible results.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microfluidic Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | Device fabrication | Biocompatible, gas permeable, optically transparent, inexpensive [11] | Sylgard 184, RTV615 |

| Thermoset Polyester (TPE) | Device fabrication for solvent resistance | Resistant to non-polar solvents, high mechanical strength [11] | Various thermoset polymers |

| Fluorosurfactants | Stabilization of water-in-oil emulsions | Prevents droplet coalescence, biocompatible [16] | EA-surfactant, Pico-Surf |

| HFE-7500 Oil | Continuous phase for droplet generation | Biocompatible, high oxygen permeability, low viscosity [16] | Fluorinated oils, Mineral oil |

| Pressure Controller | Precise fluid handling | Fast response, stable pressure control, programmability [16] | Elveflow OB1, Fluigent MFCS |

| Flow Sensors | Flow rate monitoring and feedback | High accuracy, compatibility with microfluidic flow rates [16] | Bronkhorst Coriolis, Elveflow BFS |

| Surface Modification Reagents | Channel surface functionalization | Enables cell adhesion or prevents fouling | Poly-L-lysine, PEG-silane, BSA |

Microfluidics technology has demonstrated significant potential in overcoming the traditional limitations of throughput, cost, and reproducibility in bio-engineering applications. By enabling precise fluid control at the microscale, this technology has transformed synthetic biology workflows, quality control in cell therapy manufacturing, sperm selection for assisted reproduction, and high-throughput screening platforms. The miniaturization inherent in microfluidic systems directly addresses cost barriers through dramatic reductions in reagent consumption, while automation and parallelization enhance both throughput and reproducibility. The integration of multiple processing and analysis steps into compact "lab-on-a-chip" devices streamlines experimental workflows and reduces human error, contributing to more reliable and standardized outcomes.

Looking forward, several emerging trends are poised to further expand the impact of microfluidics in bio-engineering. The development of increasingly sophisticated materials, including advanced polymers and hydrogels, will enhance device functionality and biocompatibility [11]. The integration of microfluidics with other emerging technologies such as 3D printing and artificial intelligence will enable more complex device architectures and intelligent experimental control [12]. In the clinical realm, the transition of microfluidic technologies from research tools to diagnostic and therapeutic applications represents a significant frontier, with point-of-care diagnostics and personalized medicine emerging as key growth areas [12]. For synthetic biology specifically, the convergence of microfluidics with cell-free systems and automated strain engineering platforms promises to accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle, potentially reducing development timelines from years to months. As these technologies mature and overcome current challenges related to fabrication complexity and standardization, microfluidics is positioned to become an increasingly indispensable tool in the bio-engineering toolkit, driving innovations that address pressing challenges in healthcare, energy, and environmental sustainability.

Diagram 3: Synthetic Biology DBTL Cycle

Microfluidics, the science and technology of systems that process or manipulate small amounts of fluids (10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹⁸ liters) using channels with dimensions of tens to hundreds of micrometers, has emerged as a distinct multidisciplinary field [17] [1]. This platform offers significant advantages for synthetic biology applications, including low reagent consumption, short analysis times, controlled reaction environments, and high-throughput experimentation capabilities [17] [18]. The characteristic laminar flow behavior and high surface-to-volume ratios at the microscale enable precise control over concentrations of molecules in space and time, facilitating faster reaction times and higher efficiency compared to macroscopic systems [17] [19]. This article provides a comprehensive overview of three core microfluidic modalities—droplet-based, continuous-flow, and organ-on-a-chip platforms—focusing on their fundamental operating principles, key applications in synthetic biology, and detailed experimental protocols for implementation.

Core Modalities and Operating Principles

Droplet-Based Microfluidics

Droplet-based microfluidic systems manipulate discrete volumes of fluids in immiscible phases with low Reynolds number, creating isolated microreactors ranging from nano- to femtoliter volumes [17] [20]. These systems utilize two immiscible phases: a continuous phase (the medium in which droplets flow) and a dispersed phase (the droplet phase), typically forming either water-in-oil (W/O) or oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions [20]. The key advantage of this approach lies in the ability to perform a large number of reactions in parallel without increasing device size or complexity, with generation rates reaching up to twenty thousand droplets per second [17].

Table 1: Primary Droplet Generation Methods in Microfluidics

| Method | Geometry | Droplet Size Range | Formation Rate | Key Controlling Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-flowing | T-junction, Y-junction | Usually >10 μm [20] | Up to 7 kHz [20] | Flow rate ratio, capillary number, channel dimensions [20] |

| Flow-focusing | Nozzle-like constraint | Several hundred nanometers [20] | Several hundred Hz to tens of kHz [20] | Fluid viscosity, channel geometry, flow rates [18] |

| Co-flowing | Concentric channels | Several hundred nanometers [20] | Up to tens of kHz [20] | Velocity ratio, interfacial tension, dripping/jetting regime [20] |

Droplet formation can be achieved through either passive or active methods. Passive methods, which rely solely on channel geometry and fluid dynamics, are more common due to their simpler device designs and ability to produce highly monodisperse droplets [20]. The size of generated droplets is primarily controlled by the flow rate ratio of the continuous and dispersed phases, interfacial tension between the two phases, and the geometry of the channels [20]. In microfluidic systems, droplet generation is characterized by the capillary number (Ca), which represents the ratio of viscous stress to interfacial tension [17]. The low Reynolds number flow regime (Re << 2300) ensures laminar flow within the system, which is essential for predictable droplet behavior [20].

Continuous-Flow Microfluidics

Continuous-flow microfluidics involves the control of a steady-state liquid flow through narrow channels or porous media, predominantly by accelerating or hindering fluid flow in capillary elements [1]. This modality maintains fluids in a continuous stream rather than discrete droplets, with actuation implemented through external pressure sources, external mechanical pumps, integrated mechanical micropumps, or combinations of capillary forces and electrokinetic mechanisms [1]. A significant characteristic at the microscale is the low Reynolds number, which results in strictly laminar flow where mixing occurs primarily through molecular diffusion at fluid interfaces rather than turbulence [19].

This laminar flow behavior enables the generation of precise concentration gradients that have been employed in studies of cell migration and chemical kinetics [17]. Continuous-flow systems are particularly well-suited for applications requiring steady-state conditions, such as chemical separations, continuous monitoring, and perfusion cell culture [1] [19]. However, these systems face challenges in scalability and flexibility, as permanently etched microstructures lead to limited reconfigurability and poor fault tolerance capability [1]. The fluid flow at any location within a continuous-flow system is dependent on the properties of the entire system, making integration and scaling inherently difficult [1].

Organ-on-a-Chip Platforms

Organ-on-a-chip platforms represent an advanced application of microfluidic technology that aims to mimic the structure and function of human organs in vitro. These devices typically incorporate continuous-flow principles to create physiologically relevant microenvironments for cultured cells and tissues [19]. While not explicitly detailed in the search results, these platforms represent a convergence of droplet-based and continuous-flow principles with advanced cell culture techniques, typically incorporating hydrodynamic trapping, perfusion systems, and precise environmental control to recreate organ-level functionality [19].

These devices enable researchers to cultivate small cell clusters or even single cells under defined environmental conditions with high spatio-temporal resolution, making them particularly valuable for drug screening, disease modeling, and reducing reliance on animal testing [18] [19]. The compartmentalized design allows for the establishment of physiological gradients, mechanical stimulation, and tissue-tissue interfaces that better recapitulate the in vivo environment compared to traditional cell culture systems [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Core Microfluidic Modalities

| Parameter | Droplet-Based | Continuous-Flow | Organ-on-a-Chip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Very high (up to 10⁵ samples/day) [18] | Moderate | Low to moderate |

| Volume Range | Nanoliter to femtoliter [17] | Microliter to nanoliter | Microliter to nanoliter |

| Mixing Efficiency | High (via internal circulation) [20] | Low (diffusion-based) [19] | Variable (designed) |

| Reaction Time | Seconds or less [17] | Minutes to hours | Hours to days |

| Scalability | High (parallelization) [17] | Limited [1] | Moderate |

| Cell Culture Compatibility | Limited (encapsulation) | Good (perfusion) [19] | Excellent (microenvironment) [19] |

Applications in Synthetic Biology and Drug Development

High-Throughput Screening

Droplet-based microfluidics has revolutionized high-throughput screening (HTS) by enabling the analysis of thousands to millions of discrete reactions in dramatically reduced volumes and timeframes. Microfluidic HTS achieves a notable 10³ to 10⁶-fold decrease in the volume of bioassays compared to traditional procedures, with sample manipulation rates exceeding 500 Hz—significantly higher than robotic liquid handling which operates below 5 Hz [18]. This ultrahigh-throughput capability (up to 10⁵ samples per day) makes droplet platforms particularly suitable for screening large compound libraries, mutant libraries, and environmental samples [18].

The application of droplet-based microfluidics to genetic analysis has demonstrated significant utility in developing low-cost, efficient, and rapid workflows for DNA amplification, rare mutation detection, antibody screening, and next-generation sequencing [21]. By encapsulating single DNA molecules in droplets along with PCR reagents, researchers can perform digital PCR with exceptional sensitivity and precision, enabling absolute quantification of nucleic acids without the need for standard curves [21]. This approach has become a critical component of next-generation sequencing technologies and single-cell genomic analyses [21].

Single-Cell Analysis

Microfluidic cultivation devices allow the cultivation and analysis of small cell clusters or even single cells in microfluidic structures or droplets, ranging from microliter to picoliter volumes [19]. When combined with live-cell imaging, time-lapse microscopy enables the analysis of cellular behavior in a timely resolved manner, facilitating studies of cell-to-cell heterogeneity, aging and death, growth dynamics, cell cycle monitoring, gene expression, and metabolic processes [19]. Different chamber designs—including 3D, 2D, 1D (mother machines), and 0D configurations—provide varying degrees of spatial constraint for cellular growth and colony development, each optimized for specific experimental requirements [19].

Drug Delivery and Nanomaterial Synthesis

Droplet-based microfluidic systems have been successfully employed to directly synthesize particles and encapsulate many biological entities for biomedicine and biotechnology applications [17]. These platforms enable the production of highly monodisperse particles, double emulsions, hollow microcapsules, and microbubbles with precise control over size, composition, and release characteristics [17]. The ability to generate uniform nanoparticles and drug carriers in a continuous, scalable fashion positions microfluidics as a valuable tool for pharmaceutical development and formulation [17] [18].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Droplet-Based Microfluidic Experiment

Objective: To create water-in-oil (W/O) emulsion droplets for high-throughput screening of enzymatic activity.

Materials:

- Microfluidic Device: PDMS-based flow-focusing droplet generator [17]

- Continuous Phase: Fluorinated oil with 2% (w/w) biocompatible triblock copolymer surfactant [20]

- Dispersed Phase: Aqueous solution containing substrate and buffer

- Equipment: Syringe pumps, tubing, microscope with high-speed camera

Procedure:

- Device Preparation: Fabricate PDMS device via soft lithography using standard photolithography methods [19]. Plasma-treat and bond to glass slide. Treat channels with hydrophobic coating if necessary.

- Phase Preparation: Filter both phases through 0.2 μm filters to remove particulates. Add surfactant to oil phase at 2% (w/w) concentration and mix thoroughly [20].

- System Priming: Load continuous phase into syringe and connect to device. Slowly prime device with continuous phase until all channels are filled and no air bubbles remain.

- Droplet Generation: Set continuous phase flow rate to 1000 μL/h and dispersed phase to 300 μL/h using syringe pumps. Observe droplet formation at flow-focusing junction under microscope.

- Droplet Collection: Collect emulsion in PCR tube or reservoir for downstream incubation or analysis.

- Optimization: Adjust flow rate ratios to achieve desired droplet size (typically 10-100 μm diameter). Monitor droplet uniformity using high-speed camera.

Troubleshooting:

- If droplets are not forming, check for channel blockages and ensure proper surface wettability.

- If droplet size is inconsistent, verify stable flow rates and consider adding additional surfactant.

- If droplets coalesce, increase surfactant concentration or check for proper stabilization.

Protocol 2: Microfluidic Cultivation for Single-Cell Analysis

Objective: To cultivate and monitor bacterial cells in a microfluidic device for single-cell analysis over multiple generations.

Materials:

- Microfluidic Device: PDMS-glass device with 2D cultivation chambers [19]

- Cell Preparation: Mid-log phase bacterial culture in appropriate medium

- Medium: Filter-sterilized growth medium

- Equipment: Syringe pump, microscope with environmental chamber, image analysis software

Procedure:

- Device Sterilization: Sterilize assembled microfluidic device by flushing with 70% ethanol, followed by sterile water and finally growth medium.

- Cell Loading: Dilute bacterial culture to OD₆₀₀ = 0.1 in fresh medium. Load cell suspension into device at low flow rate (50-100 μL/h) to allow cells to enter cultivation chambers via hydrodynamic trapping [19].

- Perfusion Cultivation: Once chambers are populated, switch to continuous medium perfusion at appropriate flow rate (typically 50-200 μL/h) to maintain nutrient supply and waste removal while minimizing shear stress.

- Environmental Control: Maintain device temperature at optimal growth condition using microscope environmental chamber or on-chip heating elements.

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Program microscope to acquire images at regular intervals (e.g., every 5-15 minutes) across multiple positions. Use phase contrast and/or fluorescence imaging as required.

- Data Analysis: Extract single-cell data (growth, division, morphology, fluorescence) using automated image analysis pipelines.

Troubleshooting:

- If cells do not enter traps, adjust flow rate or check trap dimensions relative to cell size.

- If cells escape from chambers, reduce chamber height or increase retention structure effectiveness.

- If nutrient gradients form, increase flow rate or redesign chamber geometry to improve mass transfer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Microfluidic Experiments

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chip Materials | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [17] | Primary material for rapid prototyping; biocompatible and transparent | Prone to swelling with organic solvents; requires surface treatment |

| Glass, Silicon [17] | Alternative materials with greater solvent resistance | Better for optical detection methods [17] | |

| Thiolene [17] | Polymer with superior chemical resistance | ||

| Surfactants | Triblock copolymer (PFPE-PEG-PFPE) [20] | Stabilizes aqueous droplets in fluorinated oil; biocompatible | Critical for preventing droplet coalescence; affects biochemical reactions |

| Fluorinated linear polyglycerols [20] | Customizable surfactant for specific applications | ||

| Continuous Phases | Fluorinated oils [20] | Carrier fluid for W/O emulsions; oxygen permeable | Biocompatible; reduces molecule extraction from aqueous phase |

| Hydrocarbon oils | Lower cost alternative for non-biological applications | Not compatible with living cells [20] | |

| Surface Chemistry | Pluronics, PEG-silanes | Prevents non-specific adsorption of biomolecules | Critical for maintaining protein activity and cell viability |

| Biological Components | Enzymes, nucleotides, antibodies | Core reagents for biochemical assays | Stability in confined volumes must be verified |

| Cell culture media | Supports growth and function of encapsulated cells | Must be compatible with surfactants and oils |

The three core microfluidic modalities—droplet-based, continuous-flow, and organ-on-a-chip platforms—offer complementary capabilities that address diverse needs in synthetic biology and drug development research. Droplet-based systems provide unparalleled throughput for screening and single-cell analysis, continuous-flow platforms enable precise environmental control for perfusion cultures and chemical synthesis, while organ-on-a-chip technologies bridge the gap between in vitro assays and in vivo physiology. As these technologies continue to mature and standardize, they promise to accelerate the pace of biological discovery and therapeutic development through increased efficiency, reduced costs, and enhanced biological relevance. The ongoing development of integrated systems that combine multiple modalities represents the next frontier in microfluidic technology, potentially enabling complete experimental workflows from single-cell analysis to tissue-level functionality assessment within unified platforms.

From Droplets to Data: Microfluidic Applications in Strain Engineering, Diagnostics, and Biomolecule Production

The transformation of engineered microbial cells constitutes a pivotal link in sustainable green biomanufacturing, which aims to replace traditional fossil-based chemical processing with sustainable cell factories for biofuel and commodity chemical production [22]. This transition fundamentally minimizes or prevents toxic pollutants and greenhouse gas emissions. A critical bottleneck in developing these microbial cell factories lies in the rapid acquisition of target strains, which requires the establishment of sophisticated high-throughput screening (HTS) strategies aimed at identifying desirable phenotypes such as enhanced enzyme activity and specific product yields [22].

Recent technological advancements have dramatically accelerated the screening process, moving from traditional microtiter plate-based methods that achieve approximately 10^6 variants per day toward ultrahigh-throughput approaches capable of analyzing up to 10^8 variants daily [22] [23]. These innovations are particularly crucial for navigating the immense combinatorial space of microbial diversity generated through random mutagenesis and directed evolution techniques. The integration of microfluidics, biosensors, and artificial intelligence has created a powerful ecosystem for optimizing strain performance beyond the limitations of mechanistic knowledge, ultimately reducing the time and cost required to obtain industrially attractive production levels [24].

Microfluidic Platforms for Ultrahigh-Throughput Screening

Droplet-Based Microfluidics (DMF) Technology

Droplet-based microfluidics (DMF) has emerged as a transformative technology for high-throughput screening, enabling the generation of discrete droplets using immiscible multiphase fluids at kHz frequencies [22]. Each droplet functions as an independent micro-reactor with a single strain encapsulated inside, facilitating distinct microbial analysis without cross-contamination. The environment within these picoliter to nanoliter droplets closely resembles conventional liquid medium, with sufficient oxygen supply for individual strain growth [22]. This compartmentalization greatly reduces reagent consumption and associated costs while providing uniform and tunable reaction environments.

The microfluidic platforms leverage laminar flow physics, characterized by low Reynolds numbers (Re < 1), which ensures highly predictable, parallel flow streams essential for reproducible experimental conditions [2]. Mainstream research typically employs single emulsion systems based on passive hydrodynamic pressure, with microchannel junctions classified into flow-focusing, cross-flow, and co-flow configurations [22]. The manufacturing of these microchemostats involves photolithographic processing of wafers followed by bonding of poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) chips to glass coverslips, creating devices with favorable air permeability and optical properties for cell observation [25] [2].

Detection Signals and Screening Modalities

Droplet microfluidics enables versatile detection approaches, expanding the variety of screenable strains and metabolites. The transparency of droplets allows accurate signal detection without interference for both intracellular and extracellular products [22]. Ordinary screening signals include fluorescence, absorbance, Raman spectrum, and mass spectrometry, with fluorescence-based sorting achieving rates up to 300 droplets per second [22].

When target products lack inherent detectable characteristics, researchers employ four main strategies to generate measurable signals:

- Fluorescent substrates for enzyme activity determination

- Fluorescent protein labeling of target compounds

- Fluorescent probe coupling with metabolic products

- Biosensors enabling sensing of target products [22]

A particularly innovative approach involves designing living biosensors where the production strain is co-embedded with a sensing strain that homogeneously responds to the former's products by emitting a fluorescent signal, indirectly reflecting targeted metabolite content [22]. This method is especially valuable for screening unexpected products or genetically difficult-to-manipulate engineered strains.

Comparative Analysis of High-Throughput Screening Platforms

Table 1: Performance comparison of major high-throughput screening platforms

| Method | Detection Signals | Sensitivity | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (MTP) | Fluorescence, Absorbance | Normal | 10^6/day | Standard screening, growth assays |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Fluorescence | High | 10^8/hour | Intracellular product detection |

| Droplet Microfluidics (DMF) | Fluorescence, Raman, Absorbance, Mass Spectrometry | High | 10^8/day | Extracellular secretions, enzyme activity, co-cultures |

Mutagenesis Methods for Library Generation

Atmospheric Room Temperature Plasma (ARTP) Mutagenesis

Atmospheric and Room Temperature Plasma (ARTP) mutagenesis has emerged as a powerful physical mutation technology for microbial strain improvement, operating at atmospheric pressure and room temperature using a helium plasma jet [26]. The system generates reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), including ions, electrons, radicals, and excited atoms that interact with cellular DNA, proteins, and membranes, triggering oxidative stress and DNA damage [26]. This damage rapidly activates the error-prone SOS repair pathway, introducing random mutations across the genome, including base substitutions, deletions, insertions, and chromosomal rearrangements [26].

ARTP offers significant advantages over traditional mutagenesis techniques, including higher mutation rates, greater safety, and avoidance of genetic modification concerns. The technology achieves higher mutation rates because the reactive species induce more extensive DNA damage compared to conventional methods like UV irradiation or chemical mutagens [26]. The workflow consists of three main stages: sample pretreatment, parameter optimization, and mutant screening. Cells in the logarithmic growth phase (typically OD600 0.6-0.8 for prokaryotes) are most suitable due to their high metabolic activity and sensitivity to external stimuli [26].

Table 2: Optimal ARTP exposure parameters for different microorganisms

| Organism Type | Power (W) | Helium Flow Rate (SLM) | Exposure Time | Optimal Lethality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 100-120 | 0-15 | 15-120 seconds | ~90% |

| Actinomycetes | 100-120 | 0-15 | 30-180 seconds | ~90% |

| Yeasts | 100-120 | 0-15 | 30-240 seconds | ~90% |

| Fungi | 100-120 | 0-15 | 60-360 seconds | ~90% |

| Microalgae | 100-120 | 0-15 | 5-150 seconds | ~90% |

In Vivo Continuous Directed Evolution

Recent advances in directed evolution have enabled continuous in vivo mutagenesis systems that simulate natural evolution in laboratory settings with reduced human intervention. These systems employ error-prone DNA polymerases and engineered DNA repair mechanisms to achieve targeted mutagenesis within living cells [23]. One innovative platform utilizes a thermo-sensitive inducible system based on engineered thermal-responsive repressor cI857 and genomic MutS mutants with temperature-sensitive defects for mutation fixation in Escherichia coli [23].

This system employs a two-plasmid approach: a low-copy mutator plasmid pSC101 carrying the mutator gene pol I under control of a thermal-responsive PR promoter, and a multicopy target plasmid pET28a containing ColE1 origin and genes of interest [23]. Temperature upshift to 37-42°C induces expression of error-prone DNA Pol I while simultaneously creating temporary defects in mismatch repair machinery, enabling increased plasmid mutagenesis rates. This platform has demonstrated approximately 600-fold increases in targeted mutation rates, significantly accelerating the evolution of biomolecules with improved or novel functions [23].

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Droplet Microfluidics Screening for Enzyme Activity

Principle: This protocol describes a droplet-based microfluidic platform for rapid screening of enzyme activity at ultrahigh throughput, particularly suitable for hydrolytic enzymes like α-amylase [23]. The method encapsulates single cells in microdroplets containing fluorogenic substrates, enabling direct correlation between enzyme activity and fluorescence intensity.

Materials:

- Microfluidic droplet generator chip (flow-focusing design)

- Syringe pumps with high precision (0.1 µL/min resolution)

- Surfactant-containing oil phase (fluorinated oil with 2-5% PEG-PFPE block copolymer)

- Aqueous cell suspension (OD600 ≈ 0.5-1.0 in appropriate growth medium)

- Fluorogenic enzyme substrate (e.g., fluorescein-di-acetate derivatives)

- In-line droplet sorter (dielectrophoretic or acoustic)

- PDMS-glass hybrid microfluidic device

Procedure:

- Device Preparation: Fabricate microfluidic devices using standard photolithography and soft lithography. Use PDMS cured on SU-8 masters and bond to glass coverslips via oxygen plasma treatment [2].

- Droplet Generation: Prepare the aqueous phase containing cells, growth medium, and fluorogenic substrate. Mix with oil phase at flow-focusing junction with typical flow rates of 100-500 µL/h for aqueous phase and 300-800 µL/h for oil phase [22].

- Incubation: Collect droplets in sealed syringe or PTFE tubing and incubate at appropriate temperature (e.g., 30-37°C for most microbes) for 2-24 hours to allow enzyme expression and substrate conversion.

- Detection and Sorting: Re-inject droplets into sorting chip and analyze fluorescence at 100-1000 droplets/second. Apply electric fields (200-1000 V/cm) to sort droplets exceeding fluorescence threshold into collection channel [22].

- Recovery and Validation: Break collected droplets using perfluorooctanol or electrocoalescence. Plate cells on solid medium for colony formation and validate hits using conventional assays.

Applications: This protocol successfully identified an α-amylase mutant with 48.3% improved activity after iterative rounds of enrichment using microfluidic droplet screening [23].

Protocol 2: ARTP Mutagenesis and Screening for Metabolite Production

Principle: ARTP mutagenesis induces widespread genomic mutations through reactive species and DNA damage, generating diverse mutant libraries for metabolite overproduction [26]. When combined with biosensor-based screening, this approach enables rapid strain improvement for compounds like resveratrol.

Materials:

- ARTP mutagenesis system (e.g., ARTP-IIS or ARTP-IIIS models)

- High-purity helium gas (≥99.99%)

- Microbial cells in mid-logarithmic growth phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6-0.8)

- Phosphate buffer or 10% glycerol solution for cell washing

- Appropriate solid and liquid growth media

- Biosensor strain responsive to target metabolite

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Harvest cells by centrifugation (5000 × g, 5 min) and wash twice with sterile phosphate buffer or 10% glycerol. Resuspend to concentration of 10^8-10^9 cells/mL [26].

- ARTP Treatment: Place 5-10 µL cell suspension on sterile carrier slide. Expose to plasma jet with optimal parameters: 100-120 W power, 2 mm distance, helium flow rate 10 SLM, with exposure time optimized for specific microbe (typically 30-120 s) [26].

- Post-Treatment Recovery: Transfer treated cells to recovery medium and incubate with shaking for 2-4 hours. Perform serial dilution and plate on solid medium to achieve 90% lethality rate.

- Biosensor Screening: For metabolite producers, co-culture with biosensor strain responsive to target compound. For resveratrol, use biosensor regulating fluorescent protein expression based on metabolite concentration [23].

- FACS Enrichment: Sort cells exhibiting highest fluorescence intensity using FACS. Collect top 0.1-1% of population for further validation.

- Validation: Cultivate sorted clones in shake flasks or microtiter plates and quantify metabolite production using HPLC or LC-MS.

Applications: This approach yielded a resveratrol-producing variant with 1.7-fold higher production when coupled with an in vivo biosensor and FACS screening [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for high-throughput screening

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorinated Oils with PEG-PFPE Surfactants | Continuous phase for droplet stabilization | Droplet microfluidics platforms | Biocompatible, prevents droplet coalescence, oxygen-permeable |

| Fluorogenic Enzyme Substrates | Generate detectable signals from enzyme activity | Detection of hydrolytic enzymes, oxidoreductases | Non-fluorescent until enzymatically cleaved |

| Transcriptional Factor-Based Biosensors | Report metabolite concentrations via fluorescence | Screening for metabolite overproducers | Specific binding to target metabolite, regulates reporter gene expression |

| Error-Prone DNA Polymerase I Mutants | In vivo mutagenesis for continuous evolution | Pol I* (D424A I709N A759R) with reduced fidelity | Targeted plasmid mutagenesis without genome alterations |

| Thermal-Responsive Repressor Systems | Regulate mutator expression in evolution systems | cI857* mutant for temperature-controlled evolution | Strong repression at 30°C, efficient induction at 37-42°C |

| Microfluidic Chip Materials (PDMS) | Device fabrication for cell encapsulation and sorting | Droplet generators, microchemostats | Optical clarity, gas permeability, flexibility |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Integrated Screening Workflow

Biosensor Signaling Pathway