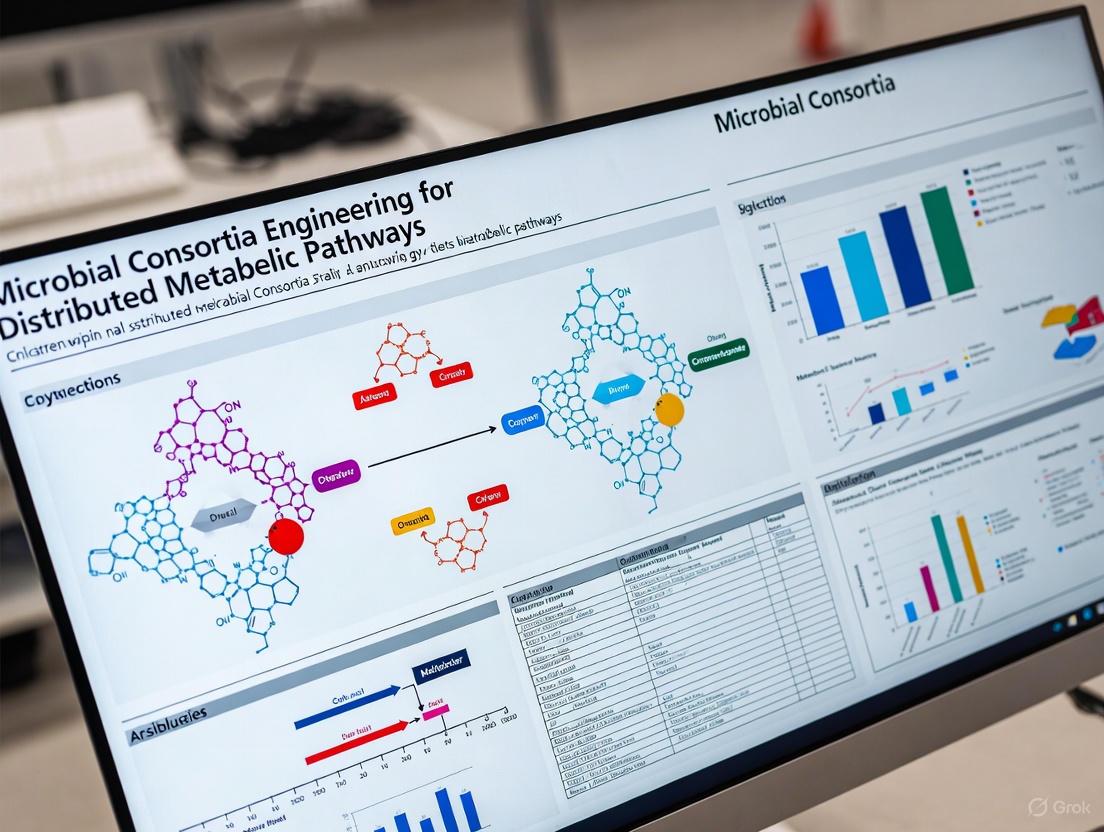

Microbial Consortia Engineering: Distributing Metabolic Pathways for Advanced Biomanufacturing and Therapeutics

This article explores the paradigm of microbial consortia engineering for distributing complex metabolic pathways across multiple specialized strains.

Microbial Consortia Engineering: Distributing Metabolic Pathways for Advanced Biomanufacturing and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm of microbial consortia engineering for distributing complex metabolic pathways across multiple specialized strains. It details the foundational principles of division of labor and synthetic ecology, the methodological toolkit for consortium design and assembly, and advanced strategies for troubleshooting stability and optimizing performance. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, it provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to harness the power of microbial communities for the efficient production of high-value chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and biomaterials, overcoming the limitations of single-strain fermentations.

The Principles and Promise of Distributed Metabolism in Synthetic Consortia

In both natural ecosystems and engineered synthetic biology, division of labor describes a functional organization where different microbial populations within a consortium perform distinct metabolic tasks. This strategy enables complex biochemical functions that would be inefficient or impossible for a single strain to accomplish [1]. The core advantage of this approach lies in its ability to reduce metabolic burden on individual cells by distributing tasks across multiple specialized strains, thereby improving overall system robustness and productivity [1]. In metabolic engineering, this principle allows researchers to partition lengthy biosynthetic pathways into manageable modules, each hosted by the microbe best suited for its specific biochemical requirements [2].

This concept mirrors natural symbiosis, where interdependent species cooperate for mutual benefit. Engineering these relationships allows for the optimization of complex pathway modules in parallel, significantly reducing development time and leveraging unique host capabilities [2]. For drug development professionals, this approach is particularly valuable for producing high-value natural products with complex structures, such as the anticancer drug paclitaxel, where different stages of the synthesis pathway require specialized cellular environments or enzymatic machinery [2] [3].

Foundational Mechanisms for Engineering Consortia

Building Blocks for Cellular Interactions

Engineering functional microbial consortia requires the implementation of specific, controlled interactions between different strains. These interactions are primarily achieved through molecular programming and can be categorized into several fundamental types.

2.1.1 Intercellular Communication The foundation of coordination in microbial consortia is often established through intercellular communication, commonly implemented via quorum-sensing (QS) systems [1]. In these systems, one cell produces signaling molecules, such as acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) in bacteria or pheromones in yeast, which regulate gene expression in other cells once a critical population density is reached [1]. This mechanism enables population-wide coordination of behavior. Synthetic biology has harnessed and expanded these natural systems, creating orthogonal signaling libraries that allow for complex, cross-species coordination without interference [1]. For example, Du et al. developed a library of six orthogonal signaling systems, including AHL-derived metabolites, organic molecules, and pheromones, significantly expanding the communication toolbox for multispecies coordination [1].

2.1.2 Negative and Positive Interactions Beyond communication, engineered consortia utilize direct positive and negative interactions to shape community dynamics. Negative interactions are typically mediated through the production of deleterious molecules such as toxins, antibiotics, or antimicrobial peptides [1]. These interactions can create competitive relationships or define spatial boundaries within a community. For instance, Fedorec et al. developed a system where one strain negatively interacts with another through bacteriocin production to precisely tune community composition [1]. Conversely, positive interactions promote growth and survival between strains, often creating interdependencies that enhance ecosystem stability [1]. These are commonly realized through the exchange of beneficial biomolecules such as metabolites, proteins, or protective factors [1]. A common strategy involves programming one strain to secrete metabolic wastes or by-products that serve as nutrients for another strain [1].

Advanced Consortium Architectures

By combining these basic building blocks, researchers have created sophisticated consortium architectures with emergent behaviors.

2.2.1 Majority Sensing Systems Scott et al. engineered a sophisticated two-strain "majority sensing" consortium that responds to population ratios rather than absolute cell density [4]. This system utilizes a co-repressive topology where each strain produces a signaling molecule that causes the other strain to downregulate production of its own orthogonal signaling molecule [4]. The genetic layout includes genes encoding an acyl-homoserine lactone synthase (RhlI or CinI), a transcriptional repressor (LacI-11 or RbsR-L), and a fluorescent reporter (sfCFP or sfYFP), with all proteins containing C-terminal ssrA degradation tags [4]. When the strains are co-cultured, the majority fraction produces more QS molecule, eventually repressing QS production in the minority strain [4]. This system is modifiable and inducible—external addition of ribose or IPTG can selectively induce one strain while repressing the other across different strain ratios [4].

2.2.2 Metabolic Division of Labor In a landmark demonstration of distributed metabolic pathways, Zhou et al. partitioned the biosynthetic pathway for paclitaxel precursors between Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2]. This approach strategically allocated pathway modules based on the unique strengths of each host: E. coli was engineered to efficiently produce taxadiene (the scaffold molecule), while S. cerevisiae, with its advanced eukaryotic protein expression machinery and intracellular membranes, hosted the cytochrome P450 enzymes required for taxadiene oxygenation [2]. Neither organism could produce the final paclitaxel precursor alone, creating obligatory cooperation [2]. To ensure stability, the researchers designed a mutualistic relationship where E. coli metabolized xylose and excreted acetate, which then served as the sole carbon source for yeast, preventing the accumulation of ethanol that would inhibit bacterial growth in the original glucose-based system [2].

Table 1: Strain Engineering for Metabolic Division of Labor in Paclitaxel Precursor Production

| Host Organism | Engineering Role | Genetic Constructs | Metabolic Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (TaxE1) | Taxadiene production | Synthetic pathway for taxadiene production | Xylose metabolism; acetate and taxadiene secretion |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (TaxS1-S4) | Taxadiene oxygenation | Taxadiene 5α-hydroxylase and CPR (5αCYP-CPR) under various promoters | Acetate metabolism; taxadiene uptake and oxygenation |

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Mutualistic Co-culture for Natural Product Synthesis

This protocol details the methodology for creating a stable mutualistic co-culture between engineered E. coli and S. cerevisiae for the production of oxygenated taxanes, based on the work of Zhou et al. [2].

3.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Consortium Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function/Application | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered E. coli TaxE1 | Taxadiene production host | Contains synthetic taxadiene production pathway; ampicillin resistant |

| Engineered S. cerevisiae TaxS1-4 | Taxadiene oxygenation host | Expresses 5αCYP-CPR (taxadiene 5α-hydroxylase + CPR); may contain antibiotic resistance as selectable marker |

| Xylose | Primary carbon source | Prefer over glucose to prevent ethanol inhibition; typically use 20 g/L in initial medium |

| Ammonium sulfate & Potassium phosphate | Nitrogen and phosphorous sources | For periodic feeding to support yeast growth; typically 2 g/L and 1 g/L respectively |

| AHL signaling molecules (C4-HSL, C14-HSL) | Inducers for quorum-sensing systems | For communication-based consortia; use at 10-100 nM depending on system sensitivity |

| IPTG & Ribose | External inducers for genetic circuits | For tuning cross-over points in majority sensing systems; typically used at 10 mM |

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

Strain Preparation

- Inoculate separate precultures of engineered E. coli TaxE1 and S. cerevisiae TaxS4 in LB+antibiotic and YPD media, respectively.

- Grow overnight at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) for E. coli and 30°C with shaking (250 rpm) for yeast.

Co-culture Initiation

- Use a bioreactor with a working volume of 1L minimal medium containing xylose (20 g/L) as the sole carbon source.

- Inoculate with E. coli TaxE1 at an initial OD600 of 0.1 and S. cerevisiae TaxS4 at an initial OD600 of 0.05.

- Maintain temperature at 30°C with agitation at 250 rpm and aeration at 1 vvm.

Fermentation Process

- Monitor optical density (OD600), acetate concentration, and ethanol concentration periodically.

- When acetate concentration falls below detection limit (indicating yeast consumption), feed additional xylose (5 g/L), ammonium sulfate (2 g/L), and potassium phosphate (1 g/L).

- Continue fermentation for 90 hours, maintaining pH at 6.8-7.0.

Product Analysis

- Extract culture broth with equal volume of ethyl acetate.

- Analyze extracts using GC-MS or LC-MS for oxygenated taxane identification and quantification.

- Compare against authentic standards for 5α-hydroxy-taxadiene and other oxygenated taxanes.

3.1.3 Critical Parameters for Success

- Carbon Source: Xylose is essential to establish the mutualistic relationship and prevent ethanol inhibition of E. coli [2].

- Inoculum Ratio: Optimal initial OD600 ratio of E. coli:yeast at 2:1 establishes balanced growth [2].

- Nutrient Feeding: Timely feeding of xylose, nitrogen, and phosphorous prevents nutrient limitation of yeast, supporting robust population maintenance [2].

- Promoter Selection: Use strong, constitutive promoters like UAS-GPDp in yeast for optimal CYP450 expression and taxadiene oxygenation efficiency [2].

Protocol 2: Assembling a Majority-Sensing Consortium

This protocol describes the construction and analysis of a two-strain co-repressive consortium that senses and responds to population ratios, based on Scott et al. [4].

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

- Engineered "cyan" and "yellow" E. coli strains containing the co-repressive circuit plasmids [4]

- LB medium with appropriate antibiotics for plasmid maintenance

- C4-HSL and C14-HSL dissolved in DMSO for calibration and control experiments

- IPTG and ribose for external induction of strain-specific expression

- 96-well plates for high-throughput ratio experiments

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

Strain Validation in Monoculture

- Grow each strain separately in LB with appropriate antibiotics.

- For each strain, test ON state (no opposite QS molecule) and OFF state (with added complementary AHL).

- Confirm fluorescent protein expression and absence of growth rate differences between ON and OFF states.

Ratio Preparation and Co-culture

- Prepare mixtures of the two strains in 10% increments from 100% cyan to 100% yellow strain.

- For spot assays, spot 5 μL of each mixture onto LB agar plates, incubate overnight at 37°C, and image with appropriate fluorescence filters.

- For quantitative analysis, grow mixed cultures in 96-well plates with 200 μL culture volume per well.

- Measure OD600 and fluorescence (cyan and yellow channels) once cultures reach stationary phase.

External Induction Testing

- Repeat ratio experiments with addition of 10 mM ribose (to fully induce cyan strain) or 10 mM IPTG (to fully induce yellow strain).

- Compare fluorescence patterns with and without inducers to demonstrate tunability.

Strain Ratio Verification

- Perform serial dilutions of final cultures and plate on LB agar without antibiotics.

- Count resulting yellow and cyan colonies to verify that final strain ratios match initial inoculation ratios.

3.2.3 Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Normalize fluorescence intensities to the maximum fluorescence (100% of either strain).

- Plot normalized fluorescence versus initial strain fraction.

- Expected result: "Majority wins" pattern with bright cyan fluorescence at high cyan fractions, bright yellow fluorescence at high yellow fractions, and dim fluorescence in near-equal mixtures.

- Compare with control consortia without communication to confirm the role of cell-cell signaling.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Performance Metrics in Engineered Consortia

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Engineered Microbial Consortia Performance

| Consortium Type & Application | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Conditions | Outcomes & Yields |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualistic E. coli-S. cerevisiae for paclitaxel precursors [2] | Oxygenated taxane titer, Taxadiene oxygenation efficiency | Fed-batch bioreactor, Xylose carbon source, 90h fermentation | Initial: 2 mg/L (glucose), 4 mg/L (xylose); Optimized: 33 mg/L with promoter and strain engineering |

| Co-repressive majority sensing consortium [4] | Fluorescence response, Strain ratio detection range | LB medium, 96-well plates, Stationary phase measurement | Clear "majority wins" pattern; Cross-over point tunable with external inducers; No growth rate impact |

| Defined yeast consortia for flavor formation [5] | Biomass, Metabolite concentrations, Interaction outcomes | Rice-based simulated starter medium, 30°C, 5 days | P.k dominance (0.82 biomass); S.c-P.k synergy (3-methylbutanal ↑20.7%, phenethyl acetate ↑31.5%) |

Analysis of Quantitative Findings

The data demonstrate that engineered division of labor significantly enhances bioproduction capabilities. In the paclitaxel precursor pathway, distributing metabolic modules between specialized hosts increased final product titers from undetectable levels in either strain alone to 33 mg/L in the optimized co-culture [2]. The coordination between strains was further refined through promoter engineering (e.g., UAS-GPDp enhanced oxygenation efficiency) and population management through carbon source selection and feeding strategies [2].

In the majority sensing system, the co-repressive consortium successfully created a predictable, tunable response to population ratios, with fluorescence patterns shifting dramatically at specific strain ratios [4]. This system maintained consistent behavior across different culture volumes and scales, indicating robust performance independent of absolute population size [4].

The defined yeast consortia for flavor formation revealed that synergistic interactions between specific strain combinations (particularly S. cerevisiae and P. kudriavzevii) significantly enhanced the production of key flavor compounds, with increases of 20.7% for 3-methylbutanal and 31.5% for phenethyl acetate compared to individual strains [5].

Visualizing Consortium Architectures

Mutualistic Metabolic Consortium Workflow

Diagram 1: Mutualistic consortium for paclitaxel precursor production. E. coli metabolizes xylose, producing taxadiene and acetate. S. cerevisiae consumes acetate as a carbon source and oxygenates taxadiene into valuable precursors.

Majority Sensing Genetic Circuit

Diagram 2: Co-repressive genetic circuit for majority sensing. Each strain produces a signaling molecule that induces a repressor in the opposing strain, creating a toggle switch based on population ratios.

The engineering of microbial consortia with defined division of labor represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering for drug development. By moving beyond single-strain approaches, researchers can harness the unique capabilities of multiple microbial hosts, creating systems that are more robust, efficient, and capable of producing complex natural products that would otherwise be inaccessible. The protocols and architectures presented here provide a framework for designing, constructing, and optimizing these sophisticated microbial communities.

For researchers in pharmaceutical development, these approaches offer tangible solutions to longstanding challenges in complex molecule synthesis. The ability to distribute metabolic pathways across specialized hosts bypasses cellular incompatibilities, reduces metabolic burden, and leverages the innate strengths of diverse microbial systems. As these technologies mature, engineered microbial consortia will play an increasingly vital role in the sustainable production of high-value therapeutics, from anticancer agents to specialized metabolites with novel bioactivities.

Microbial consortia represent an advanced paradigm in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, defined as communities of two or more genetically distinct microbial populations that work together synergistically to perform complex functions [6]. This approach marks a significant shift from traditional monoculture engineering, which often faces inherent limitations when dealing with sophisticated biotechnological challenges. Natural microbial consortia are ubiquitous in ecosystems, where multiple species collaborate to degrade complex substrates, cycle nutrients, and create stable communities that are resilient to environmental perturbations [7]. Inspired by these natural systems, researchers have developed engineering strategies to create synthetic microbial consortia with predefined functions.

The fundamental principle underlying microbial consortia is division of labor, where different subpopulations are engineered to perform specialized tasks that collectively achieve the desired overall function [8]. This division can occur through various interactive relationships, including mutualism, commensalism, and protocooperation [9]. By distributing metabolic tasks across multiple specialized strains, consortia effectively address critical limitations of monocultures, particularly metabolic burden and restricted functional capacity [6] [7]. This engineering framework has opened new possibilities for applications ranging from pharmaceutical production to environmental remediation.

Key Advantages of Microbial Consortia

Reducing Metabolic Burden

Metabolic burden represents a fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering, where the expression of heterologous pathways competes with host cellular processes for limited resources, including nucleotides, amino acids, energy molecules (ATP), and cofactors [8]. In monocultures, this burden manifests as reduced growth rates, genetic instability, and suboptimal production titers—a phenomenon described as the "metabolic cliff" where even minor perturbations can dramatically decrease performance [9].

Microbial consortia mitigate this burden through pathway compartmentalization, distributing biochemical steps across multiple strains so that no single cell bears the full metabolic cost [6] [7]. This division of labor allows each subpopulation to maintain fewer heterologous enzymes, reducing the resource competition that plagues heavily engineered monocultures [8]. Consequently, consortia can maintain higher growth rates and genetic stability while achieving improved production metrics compared to single-strain approaches [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparisons of Metabolic Burden in Monocultures vs. Consortia

| Engineering Approach | Specific Production | Genetic Stability | Pathway Complexity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoculture E. coli | ~100 mg/L/OD muconic acid | Low (high mutation rate) | Limited by host capacity | [8] |

| E. coli-E. coli Consortium | >800 mg/L/OD muconic acid | High (stable co-culture) | Expanded via distribution | [8] |

| Single Species | Challenging for long pathways | Variable | Constrained | [6] |

| Multi-Species Consortium | Enhanced for complex pathways | Improved via mutualism | Significantly expanded | [3] [7] |

Expanding Functional Capacity

Beyond reducing metabolic burden, microbial consortia substantially expand functional capacity by leveraging the unique capabilities of different microbial hosts [6]. This advantage manifests in several critical applications:

Utilization of Complex Substrates: Consortia can efficiently process heterogeneous feedstocks that monocultures cannot. For example, in consolidated bioprocessing for biofuel production, fungal strains secrete cellulases to break down lignocellulosic biomass into simple sugars, while engineered bacteria simultaneously ferment these sugars into biofuels like isobutanol [9]. This collaborative approach achieves yields up to 62% of theoretical maximum, far exceeding monoculture capabilities [9].

Incompatible Process Integration: Some biological processes require specialized cellular environments that cannot coexist in a single strain. Consortia enable spatial and temporal segregation of incompatible pathways, such as those requiring different oxygenation conditions, pH optima, or intracellular cofactors [6] [3]. The production of oxygenated taxane precursors exemplifies this advantage, where early pathway steps are optimized in E. coli while later oxygenation reactions occur more efficiently in yeast [3].

Complex Biomolecular Systems: Consortia enable the production of sophisticated multi-component systems that would overwhelm single strains. Remarkably, researchers have assembled a 34-strain consortium where each strain produces one component of the complex PURE (protein synthesis using recombinant elements) system—a feat nearly impossible to accomplish in a monoculture [10].

Table 2: Applications Demonstrating Expanded Functional Capacity

| Application Area | Consortium Composition | Achievement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Production | E. coli + S. cerevisiae | 33 mg/L oxygenated taxanes (paclitaxel precursor) | [3] |

| Biofuel Production | Trichoderma reesei + E. coli | 1.9 g/L isobutanol from cellulose | [9] |

| Multi-Protein System | 34 E. coli strains | Functional 34-component PURE protein synthesis system | [10] |

| Environmental Remediation | Acinetobacter lwoffii + Enterobacter sp. | Enhanced atrazine degradation and phosphorus mobilization | [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing a Mutualistic Consortium for Natural Product Synthesis

This protocol outlines the creation of a mutualistic E. coli-S. cerevisiae consortium for producing oxygenated taxanes, based on the pioneering work of Zhou et al. [3] [7].

Principle: Division of labor allows each organism to perform specialized metabolic steps while cross-feeding essential metabolites ensures stable coexistence [3].

Materials:

- Engineered E. coli strain containing upstream taxadiene synthesis pathway

- Engineered S. cerevisiae strain containing cytochrome P450 oxygenases

- M9 minimal medium with 2% glucose

- Carbon source crossover feed (0.1% acetate for E. coli maintenance)

- Inducers for pathway activation (e.g., IPTG, aTc)

- Analytical equipment: HPLC-MS for taxane detection

Procedure:

- Strain Engineering: Partition the metabolic pathway so early steps (taxadiene production) are expressed in E. coli, while later oxidation steps are encoded in S. cerevisiae [3].

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow monocultures of each strain overnight to stationary phase in appropriate selective media.

- Co-culture Establishment: Inoculate bioreactor containing M9 medium with 2% glucose with a 1:4 ratio of E. coli:S. cerevisiae at an initial OD600 of 0.1 [7].

- Process Optimization: Maintain co-culture by feeding 0.1% acetate to support E. coli population when glucose is depleted [7].

- Population Monitoring: Regularly sample the consortium and use species-specific selective plates to quantify population dynamics.

- Product Analysis: Extract culture samples with ethyl acetate and analyze by HPLC-MS for oxygenated taxane production [3].

Expected Outcomes: Stable co-culture maintaining approximate 1:4 ratio, producing up to 33 mg/L of oxygenated taxanes including monoacetylated dioxygenated taxane [3].

Figure 1: Metabolic Division of Labor in E. coli-S. cerevisiae Consortium for Taxane Production

Protocol 2: Consortium Stabilization via Quorum Sensing Regulation

This protocol describes implementing a quorum sensing (QS) system to stabilize population dynamics in synthetic consortia, preventing overgrowth of faster-growing strains [6] [7].

Principle: Engineered communication circuits enable population control through synchronized lysis or growth regulation based on cell density [7].

Materials:

- E. coli strains engineered with orthogonal QS systems (e.g., lux, las, rpa, tra)

- Bacteriocin genes (e.g., lactococcin A) for competitive interactions

- Antibiotic resistance genes for cooperative interactions

- AHL signaling molecules (3OC6HSL, 3OC12HSL)

- Luria-Bertani (LB) medium

- Inducers for circuit control (IPTG, aTc)

Procedure:

- Circuit Design: Implement orthogonal QS systems (e.g., lux and las) with minimal crosstalk in two E. coli strains [6].

- Genetic Construction: Engineer Strain A to produce lactococcin A bacteriocin under control of a QS promoter. Engineer Strain B to express lactococcin A resistance gene under control of a different QS promoter [6].

- System Calibration: First characterize the QS response curves for each strain in monoculture by measuring gene expression as a function of exogenous AHL concentration.

- Consortium Assembly: Inoculate both strains in a 1:1 ratio in LB medium without antibiotics.

- Dynamic Monitoring: Sample every 2 hours for 24-48 hours, measuring OD600 and using flow cytometry with strain-specific fluorescent markers to track population ratios.

- Circuit Induction: Add appropriate inducers once populations reach mid-log phase to activate the QS circuits.

Expected Outcomes: Stable coexistence of both populations with oscillatory dynamics within defined bounds, rather than extinction of the slower-growing strain [7].

Figure 2: Quorum Sensing Circuit for Population Control in Synthetic Consortia

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Consortia Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specific Components |

|---|---|---|

| Communication Systems | Enable inter-strain signaling for coordinated behavior | AHL-based systems (lux, las, rpa, tra), autoinducing peptides, cytokinin (IP) system for yeast [6] |

| Orthogonal Regulators | Independent control of multiple strains without crosstalk | Engineered transcriptional regulators, mutated promoter-operator systems, light-inducible systems [6] |

| Spatial Organization Tools | Physical segregation for stable coexistence | Chitosan microcapsules [10], biofilms, hydrogel immobilization [12] |

| Metabolic Cross-feeding Modules | Create syntrophic dependencies for consortium stability | Acetate-glucose cycling [7], amino acid auxotrophies, vitamin exchange [9] |

| Population Control Circuits | Regulate strain ratios and prevent overgrowth | Synchronized lysis circuits (SLC) [7], toxin-antitoxin systems, bacteriocin-mediated killing [6] |

| Computational Design Tools | Model and predict consortium dynamics | Metabolic flux analysis, population dynamics modeling, cross-feeding network prediction [6] [12] |

Microbial consortia engineering represents a transformative approach in biotechnology that effectively addresses fundamental limitations of traditional monocultures. Through strategic division of labor, synthetic consortia significantly reduce metabolic burden by distributing heterologous pathway expression across multiple specialized strains, thereby avoiding the "metabolic cliff" that constrains single-strain engineering [9] [8]. Furthermore, consortia dramatically expand functional capacity by enabling incompatible processes, leveraging unique host capabilities, and utilizing complex substrates with efficiencies unattainable by monocultures [6] [3].

The experimental protocols and toolkit presented here provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing consortium-based approaches. Key strategies include designing mutualistic dependencies through metabolic cross-feeding [3] [7], implementing robust population control via engineered communication circuits [6] [7], and utilizing spatial organization techniques to stabilize community composition [10]. As these technologies mature, microbial consortia are poised to enable increasingly sophisticated biotechnological applications, from distributed pharmaceutical biosynthesis to complex environmental remediation tasks that require multiple biological functionalities operating in concert [11] [12].

Application Notes: Engineering Ecological Interactions in Microbial Consortia

The engineering of synthetic microbial consortia allows for the division of labor in complex tasks, such as distributed metabolic pathways, which can reduce the cellular burden compared to implementing all components in a single strain [7]. This is achieved by programming specific, well-defined ecological interactions between different microbial populations. Below are the core interactions and their applications.

Mutualism

Mutualistic interactions are engineered to enhance the stability and productivity of co-cultures, particularly in metabolic engineering. This is often achieved by cross-feeding, where one strain consumes a byproduct of another that would otherwise be inhibitory.

- Application in Metabolic Pathways: A mutualistic consortium can be designed for efficient biochemical production. For instance, in a system for taxane production, one strain is engineered to perform the upstream steps of a pathway, excreting an intermediate. A second strain imports this intermediate to complete the biosynthesis. This division of labor can increase final product titer and process stability [7].

- Application in Waste-to-Value Conversion: A synthetic mutualism was designed for converting carbon monoxide (CO) into valuable chemicals. Eubacterium limosum naturally consumes CO and produces acetate. When acetate accumulates, it inhibits growth. An engineered E. coli strain was introduced to consume the acetate and convert it into target biochemicals like itaconic acid or 3-hydroxypropionic acid, creating a stable, productive system [7].

Predator-Prey

Predator-prey dynamics generate oscillatory population dynamics, which can be used for dynamic control of system behavior and for basic understanding of community stability.

- Application in Dynamic Control: An early synthetic predator-prey system used two E. coli populations communicating via quorum sensing (QS). The "predator" constitutively expressed a suicide gene, but the "prey" produced a QS signal that triggered the expression of an antidote in the predator. Conversely, the predator produced a different QS signal that induced death in the prey. This created a feedback loop for oscillatory populations [7]. Such systems can be used as a biological timer or to prevent the overgrowth of any single population in a consortium.

Competition and its Mitigation

In the absence of stabilizing mechanisms, competition for shared nutrients and space will lead to the extinction of the slower-growing strain by the faster-growing one. Actively mitigating this competition is therefore critical for consortium stability.

- Application in Population Control: Competition can be mitigated by introducing negative feedback loops that limit population growth. One approach uses synchronized lysis circuits (SLC). In this system, each engineered population uses QS to sense its own density. Upon reaching a high density, the population initiates its own lysis. This self-limitation prevents any one strain from dominating and allows multiple strains to coexist stably [7].

Table 1: Summary of Engineered Ecological Interactions and Their Quantitative Outcomes

| Ecological Interaction | Engineered System | Key Components | Quantitative Outcome/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | E. coli & S. cerevisiae for taxane production [7] | Cross-feeding of metabolic intermediates | Increased product titer and culture stability compared to competitive co-cultures [7] |

| Mutualism | Eubacterium limosum & engineered E. coli for CO conversion [7] | Consumption of inhibitory acetate (by E. coli) produced from CO (by E. limosum) | Improved CO consumption efficiency and biochemical production vs. monoculture [7] |

| Predator-Prey | Two E. coli strains with QS-mediated toxin/antidote [7] | Acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) QS molecules, suicide protein (CcdB), antidote protein (CcdA) | Demonstrated oscillatory population dynamics dependent on initial conditions [7] |

| Competition Mitigation | Two E. coli strains with orthogonal SLCs [7] | AHL QS molecules, lysis genes | Enabled stable coexistence of two competing populations [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Establishing a Mutualistic Co-culture for Metabolic Pathway Division

This protocol outlines the steps for creating and maintaining a stable mutualistic co-culture between two microbial strains engineered for a distributed metabolic pathway.

Principle: Two microbial strains are co-cultured in a bioreactor. Strain A consumes a primary carbon source and produces a metabolic intermediate, which is exported. Strain B imports this intermediate and converts it into a valuable final product. The consumption of the intermediate by Strain B prevents its accumulation to inhibitory levels, creating a mutually beneficial relationship [7].

Materials:

- Strains: Genetically engineered E. coli (Strain A) and S. cerevisiae (Strain B).

- Growth Medium: Defined minimal medium with appropriate carbon source (e.g., glucose).

- Bioreactor: Bench-top bioreactor with control for temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen.

- Analytical Instruments: HPLC or GC-MS for quantifying substrate, intermediate, and product concentrations.

Procedure:

- Pre-culture: Inoculate pure cultures of Strain A and Strain B in separate flasks and grow overnight to mid-exponential phase.

- Inoculation: Inoculate the bioreactor containing fresh, pre-warmed medium with a defined initial ratio of Strain A and Strain B (e.g., 1:1 cell count). Record the initial optical density (OD) for each strain if distinguishable by fluorescence or selective plating.

- Fermentation: Operate the bioreactor in batch or fed-batch mode. Maintain optimal environmental conditions (e.g., 37°C for E. coli, 30°C for yeast, pH 7.0, adequate aeration).

- Monitoring: At regular intervals (e.g., every 2-4 hours), aseptically withdraw samples from the bioreactor.

- Measure OD to track total biomass.

- Use selective agar plates or flow cytometry to determine the individual population densities of Strain A and Strain B.

- Centrifuge samples to separate cells from the supernatant. Analyze the supernatant using HPLC to quantify the concentrations of the primary carbon source, the metabolic intermediate, and the final product.

- Data Analysis: Plot the growth curves of both strains and the concentration profiles of all relevant chemicals over time. A stable mutualism is indicated by the sustained coexistence of both populations and continuous production of the target metabolite.

Protocol for Implementing a Synthetic Predator-Prey System

This protocol describes the construction and analysis of a synthetic ecosystem exhibiting oscillatory predator-prey dynamics.

Principle: Two E. coli strains are engineered to communicate via two orthogonal QS systems. The prey strain produces Signal A, which activates an antidote in the predator. The predator produces Signal B, which activates a toxin in the prey. This cross-regulation creates a network that can produce oscillations in population densities [7].

Materials:

- Strains: Engineered E. coli predator and prey strains.

- Medium: LB or M9 minimal medium.

- Inducers: Chemical inducers (e.g., IPTG) may be used to fine-tune circuit parameters.

- Microplate Reader or Flow Cytometer: For high-throughput, real-time monitoring of population densities.

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Transform predator and prey strains with plasmids encoding the respective QS circuits, toxin, and antidote genes. Include fluorescent reporter genes (e.g., GFP for prey, RFP for predator) for easy population tracking.

- Co-culture Initiation: Inoculate a fresh medium in a shake flask or a well-plate with a low initial density of both predator and prey.

- Real-time Monitoring: Place the culture in a microplate reader incubator. Measure OD and fluorescence (GFP, RFP) every 10-30 minutes over 24-48 hours.

- System Perturbation: To validate the model, repeat the experiment with different initial ratios or add varying concentrations of inducers to alter the strength of the interaction.

- Model Fitting: Develop a mathematical model (e.g., using ordinary differential equations) based on the known interaction topology. Fit the model parameters to the experimental data to predict behaviors like oscillation periods or conditions for population collapse.

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Figure 1: Predator-Prey QS Signaling Network

Figure 2: Mutualistic Cross-Feeding Metabolic Workflow

Figure 3: Synchronized Lysis Circuit (SLC) Feedback Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Engineering Microbial Consortia

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems | Enables cell-to-cell communication for coordinating gene expression across populations. | Orthogonal AHL systems (e.g., LuxI/LuxR, LasI/LasR) for independent channel communication [7]. |

| Toxin-Antitoxin Systems | Provides a mechanism for population control by inducible cell death or growth inhibition. | CcdB/CcdA system for predator-prey dynamics or population culling [7]. |

| Bacteriocins | Allows for targeted killing of specific strains without engineered resistance, enabling competitive interactions. | Colicins or microcins in E. coli to create competitive exclusion [7]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins | Labels individual populations for tracking and quantifying their dynamics in real-time via flow cytometry or microscopy. | GFP, RFP, and other color variants for distinguishing Strain A from Strain B in a co-culture [7]. |

| Orthogonal Plasmid Systems | Maintains genetic circuits in co-cultures by using different replication origins and selection markers to avoid plasmid incompatibility. | Combinations of ColE1, p15A, and pSC101 origins with complementary antibiotic resistance genes [7]. |

| Metabolic Pathway Modules | Genetically encoded sets of enzymes that perform a specific biochemical conversion, allowing for division of labor. | Modules for upstream (e.g., terpenoid precursors) and downstream (e.g., taxane synthesis) pathway steps [7]. |

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Design Strategies for Consortium Construction

The engineering of microbial consortia for distributed metabolic pathways is a cornerstone of advanced bioprocessing in synthetic biology. Two principal strategic paradigms—top-down and bottom-up design—enable researchers to construct microbial communities for complex tasks that are challenging or impossible for single strains to accomplish. These consortia leverage division of labor, where the metabolic burden of a long biosynthetic or degradative pathway is distributed across different specialized strains, enhancing overall system stability and efficiency [13]. The choice between a top-down or bottom-up approach fundamentally shapes the design process, control mechanisms, and potential applications of the resulting consortium, each offering distinct advantages and challenges for engineering distributed metabolic functions.

Top-down design is a classical approach that uses carefully selected environmental variables to steer an existing microbiome through ecological selection to perform desired biological processes [13] [14]. This method treats the microbial community as a system model where inputs and outputs are defined, including physical and chemical conditions, known abiotic and biological processes, and environmental variables [13]. Conversely, bottom-up design represents a more recent engineering strategy that employs prior knowledge of metabolic pathways and potential interactions among consortium partners to rationally design and assemble synthetic microbial consortia from individual characterized strains [14] [15]. This approach offers greater control over consortium composition and function but faces challenges in optimal assembly methods and long-term stability [14].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches

| Characteristic | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Design Philosophy | Community-level selection via environmental pressures | Rational assembly from individual characterized strains |

| Starting Material | Complex natural microbiomes | Defined, isolated microbial strains |

| Control Mechanism | Manipulation of environmental variables and selection pressures | Engineering of specific interactions and metabolic pathways |

| Implementation Complexity | Technically straightforward but difficult to deconstruct | High initial characterization requirement |

| Predictability | Lower; relies on enrichment of natural variants | Higher; based on known strain characteristics |

| Typical Applications | Wastewater treatment, bioremediation, anaerobic digestion | Production of high-value chemicals, specialized biodegradation |

Theoretical Frameworks and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Principles of Top-Down Design

The top-down approach to microbial consortia construction applies ecological principles to shape community structure and function through selective pressures. This method does not presuppose which specific organisms or detailed metabolic pathways will be employed; instead, it relies on manipulating environmental conditions to drive an existing microbiome toward performing target functions [13] [14]. The theoretical foundation rests on ecological selection principles, where environmental parameters such as nutrient availability, temperature, pH, and electron acceptors/donors create selective conditions that favor microorganisms with desired metabolic capabilities [13]. This approach has been widely successful for applications including wastewater treatment and bioremediation, where the primary goal is functional outcome rather than specific community composition [13].

A significant consideration in top-down design is that it often overlooks processes dependent on intricate interactions between consortium members [13]. The approach conceptualizes microbial consortia as a system model with defined inputs and outputs but typically does not attempt to elucidate or control the complex network of microbial interactions that emerge. While this reduces the initial engineering complexity, it also limits the ability to precisely control or optimize specific metabolic exchanges within the community. Recent research has revealed that higher-order interactions (HOIs) become increasingly important as the number of populations in a microbial consortium grows, adding layers of complexity that are difficult to predict or control in top-down designs [13]. These HOIs can either stabilize or destabilize a consortium, as the presence of additional populations can modulate existing interactions between community members in non-additive ways [13].

Fundamental Principles of Bottom-Up Design

Bottom-up design represents a more reductionist approach to consortium engineering, building microbial communities from well-characterized individual components. This strategy employs prior knowledge of metabolic pathways and potential microbial interactions to rationally assemble consortium members [14] [15]. The theoretical foundation of bottom-up design integrates principles from synthetic biology, systems biology, and ecology to create predictable, controllable microbial systems [13]. This approach enables researchers to distribute multiple catalytic enzyme expression pathways across different strains, then co-culture these specialized strains to complete complex tasks [13].

A core advantage of bottom-up design is the ability to reduce metabolic burden on individual cells by rationally dividing labor across different consortium members [13]. By compartmentalizing metabolic pathways into different strains, researchers can avoid cross-reactions and metabolic conflicts that often occur when engineering complex pathways into single organisms. However, excessive segmentation of metabolic pathways can lead to confusion and reduced mass transfer efficiency [13]. Bottom-up design also enables the implementation of synthetic communication systems, such as quorum-sensing circuits, to coordinate behavior across the consortium [16]. These engineered interactions can help maintain population balance and synchronize metabolic activities, though they also introduce additional complexity that must be carefully controlled.

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of Each Approach

| Aspect | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | - Leverages natural microbial diversity- High functional resilience- Technically accessible- Proven industrial applications | - Precise control over composition- Clear molecular mechanisms- Easier intellectual property protection- Modular optimization potential |

| Limitations | - Complex community dynamics- Difficult to reproduce- Limited mechanistic understanding- Black box characteristics | - Requires extensive strain characterization- Vulnerable to population instability- High initial development cost- Limited functional diversity |

| Ideal Use Cases | - Environmental remediation- Waste valorization- Systems where precise control is unnecessary | - High-value chemical production- Metabolic pathway prototyping- Systems requiring precise regulation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Top-Down Consortium Development

The top-down approach to consortium development employs selective enrichment from complex natural inocula to obtain microbial communities with desired functional characteristics. This protocol outlines the standard methodology for developing lignocellulose-degrading consortia, adaptable to other metabolic functions through modification of selective substrates and conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Environmental samples (soil, sediment, water, or compost)

- Mineral salts base medium

- Target substrate (e.g., lignocellulosic biomass, pollutant)

- Anaerobic chamber (for anaerobic consortia)

- Serial dilution buffers

Procedure:

- Inoculum Collection and Preparation: Collect environmental samples from habitats rich in the target functionality. For lignocellulose degradation, forest soils, decaying wood, or canal sediments are appropriate sources [17]. Suspend samples in sterile dilution buffer and homogenize.

Primary Enrichment: Inoculate the prepared environmental sample into mineral medium containing the target substrate as the sole or primary carbon source. For lignocellulose-degrading consortia, use 1-2% (w/v) pretreated lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., wheat straw, corn stover) [17]. Incubate under conditions selective for the desired function (aerobic/anaerobic, specific temperature, pH).

Serial Transfer and Stabilization: Transfer 10% (v/v) of the enrichment culture to fresh medium containing the same substrate at regular intervals (typically 7-14 days). Repeat this process for multiple generations (5-10 transfers) until stable degradation performance is observed [17].

Community Analysis and Functional Validation: Monitor substrate degradation throughout the enrichment process. For lignocellulose-degrading consortia, measure lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose content using standardized methods (e.g., NREL protocols). Characterize community composition through 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing at various transfer points to track community succession [17].

Consortium Preservation: Cryopreserve stabilized consortia in 15-25% glycerol at -80°C for long-term storage. Maintain active cultures through regular transfer on selective media.

This protocol yielded the DM-1 consortium from tree trimmings, which included Mesorhizobium, Cellulosimicrobium, Pandoraea, Achromobacter, and Stenotrophomonas as predominant genera and achieved 28.7% lignin and 10.2% cellulose degradation [17]. Similarly, this approach developed a saline-adapted consortium dominated by Joostella marina, Flavobacterium beibuense, Algoriphagus ratkowskyi, Pseudomonas putida, and Halomonas meridiana that demonstrated 64.2% cellulose and 61.4% lignin degradation [17].

Protocol for Bottom-Up Consortium Assembly

The bottom-up approach involves rational design and assembly of microbial consortia from defined, characterized strains. This protocol details the construction of algae-bacteria consortia for volatile organic compound (VOC) biodegradation, with principles applicable to other metabolic systems.

Materials and Reagents:

- Axenic cultures of candidate strains

- Defined mineral medium

- Target substrates (e.g., VOCs: benzene, toluene, phenol)

- 96-well plates for high-throughput screening

- Sterile sealing films for VOC containment

- Chlorophyll extraction and measurement reagents

Procedure:

- Strain Selection and Characterization: Select microbial strains based on prior knowledge of metabolic capabilities and compatibility. For VOC degradation, bacterial strains such as Rhodococcus erythropolis and Cupriavidus metallidurans show proven degradation capabilities, while phototrophic microalgae like Coelastrella terrestris provide oxygen and consume bacterial metabolites [15]. Characterize growth kinetics and substrate preferences of individual strains.

High-Throughput Consortium Screening: Develop a microplate-scale screening system to rapidly assess different consortium combinations. Inoculate 96-well plates with systematic combinations of algae and bacteria in defined ratios. Add 100 mg/L of target VOCs (benzene, toluene, phenol) and seal plates with gas-permeable membranes to prevent VOC loss while allowing gas exchange [15]. Monitor consortium performance through chlorophyll fluorescence measurements as a proxy for algal biomass and overall system health.

Performance Validation and Optimization: Validate promising consortia identified in primary screening by scaling up to flask cultures. Quantify VOC degradation efficiency using GC-MS or HPLC analysis. Measure biomass accumulation and population dynamics through cell counting and qPCR. Optimize consortium ratios and cultivation conditions based on performance metrics [15].

Interaction Analysis: Characterize metabolic interactions within the consortium through exometabolomic analysis of spent media. Identify cross-feeding relationships and potential inhibitory compounds. Monitor community stability through serial batch transfers or continuous culture experiments.

Application Testing: Evaluate consortium performance under realistic application conditions. For VOC degradation, test in airlift bioreactors or biofiltration systems with continuous VOC loading.

This protocol enabled the identification of robust algae-bacteria consortia that achieved 95.72% benzene degradation, 92.70% toluene degradation, and near-complete phenol removal (100%) at initial concentrations of 100 mg/L within 7 days [15]. The high-throughput screening approach facilitated rapid identification of functional consortia without requiring complete understanding of the complex interaction networks [15].

Diagram 1: Bottom-Up Consortium Screening Workflow. This high-throughput approach enables rapid identification of functional microbial partnerships without requiring complete understanding of interaction networks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development of microbial consortia requires specialized reagents and materials tailored to either top-down or bottom-up approaches. This section details essential research tools for consortium construction and characterization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Consortium Engineering

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selection Media | Minimal salts base medium | Provides essential nutrients while forcing substrate utilization | Mineral medium with lignocellulose as sole carbon source [17] |

| Target substrates | Selective pressure for desired metabolic functions | Lignocellulosic biomass, VOCs, antibiotics, dyes [13] [15] | |

| Characterization Tools | DNA extraction kits | Community composition analysis through amplicon sequencing | Metagenomic analysis of enriched consortia [17] |

| Metabolite analysis standards | Quantification of substrate degradation and product formation | GC-MS analysis of VOC degradation [15] | |

| Cultivation Systems | 96-well microplates | High-throughput screening of consortium combinations | Bottom-up screening of algae-bacteria consortia [15] |

| Anaerobic chambers | Development of oxygen-sensitive consortia | Enrichment of anaerobic lignocellulose-degrading consortia [17] | |

| Stabilization Materials | Hydrogel immobilization matrices | Spatial organization and functional preservation | Strain immobilization for improved biodegradation efficiency [13] |

| Microfluidic devices | Spatiotemporal control of consortium interactions | Fine regulation of different strains in artificial systems [13] |

Advanced Engineering Strategies for Consortium Optimization

Spatial Organization and Immobilization Techniques

The ordered spatiotemporal distribution of strains within microbial consortia significantly enhances functional efficiency by providing specialized microenvironments and establishing metabolic proximity. Strain immobilization represents a foundational application of spatial organization that plays an important role in promoting the biodegradation of complex compounds [13]. Advanced immobilization carriers, including specialized hydrogels, serve as protective matrices that maintain strain viability and functionality while permitting material exchange [13]. These innovative materials enable the co-localization of complementary strains while potentially separating incompatible microorganisms, allowing for the creation of optimized microenvironments within a shared bulk environment.

Microfluidic technology has emerged as a powerful tool for achieving fine-scale spatiotemporal control of microbial consortia [13]. These systems enable precise manipulation of different strains within miniature cultivation environments, significantly enhancing control over consortium structure and function. For example, researchers have designed specialized bioreactors that leverage spatial gradients of electron acceptors, such as oxygen, to enable the coexistence of metabolically diverse microorganisms [13]. One research team developed a ventilated biofilm reactor that utilized the spatial distribution of oxygen to support the functional complementarity of three distinct bacterial types, dramatically improving overall consortium efficiency [13]. Such approaches demonstrate how physical design and engineering principles can be harnessed to overcome physiological incompatibilities between consortium members.

Metabolic Engineering and Cross-Feeding Strategies

Advanced engineering of microbial consortia increasingly incorporates synthetic biology tools to establish and control metabolic interactions between consortium members. Rational division of long or complex metabolic pathways across specialized strains reduces cellular metabolic burden and minimizes pathway conflicts [13]. However, excessive segmentation of metabolic pathways can introduce mass transfer limitations and reduce overall efficiency [13]. A key strategy involves designing sequential substrate utilization patterns where different consortium members specialize in degrading specific components of complex mixtures or metabolic intermediates [13]. This approach not only minimizes direct competition for substrates but can also alleviate feedback inhibition by preventing the accumulation of inhibitory intermediates.

Engineering synthetic cross-feeding relationships represents a sophisticated approach to stabilizing microbial consortia [16]. These designed metabolic interdependencies create mutualistic relationships where consortium members exchange essential metabolites, thereby encouraging stable coexistence. Molecular communication systems, particularly quorum-sensing circuits, can be implemented to coordinate population dynamics and metabolic activities across the consortium [16]. Additionally, researchers are developing creative solutions to enhance metabolite exchange between consortium members, including the engineering of shared extracellular spaces and the implementation of molecular transport systems that improve the efficiency of metabolic handoffs [16]. These advanced strategies move beyond simple co-cultivation toward truly integrated, collaboratively functioning microbial communities.

Diagram 2: Advanced Consortium Engineering Strategies. Combining spatial organization with metabolic engineering approaches enables the creation of stable, high-performance microbial consortia.

Comparative Performance Analysis and Applications

Functional Performance Metrics

Quantitative assessment of consortium performance provides critical insights for selecting appropriate design strategies based on application requirements. The comparative efficiency of top-down versus bottom-up approaches varies significantly across different functional domains, with each demonstrating distinct strengths in specific applications.

In lignocellulose bioconversion, top-down enriched consortia frequently exhibit superior degradation capabilities compared to single strains or simply assembled bottom-up consortia. The DM-1 consortium, developed through top-down enrichment from tree trimmings, achieved 28.7% lignin and 10.2% cellulose degradation, outperforming pure cultures like R. opacus PD630 and Pseudomonas putida A514, which typically show 15-18% lignin consumption [17]. Similarly, a saline-adapted consortium selected through sequential cultivation on wheat straw demonstrated remarkable degradation efficiency, reaching 64.2% cellulose and 61.4% lignin degradation under saline conditions [17]. These top-down consortia leverage natural microbial complementarity that can be challenging to replicate through rational design.

For specialized biodegradation tasks, bottom-up approaches enable precise engineering of degradation pathways. In VOC removal, constructed algae-bacteria consortia achieved 95.72% benzene degradation, 92.70% toluene degradation, and near-complete phenol removal (100%) at initial concentrations of 100 mg/L within 7 days [15]. The high degradation efficiency was directly correlated with algal growth (R = 0.82, p < 0.001), demonstrating the synergistic relationship enabled by rational consortium design [15]. Bottom-up approaches also show significant promise in lignocellulose bioconversion, particularly when incorporating engineered strains with enhanced enzymatic capabilities or designed metabolic interactions.

Application-Specific Implementation Guidelines

Selecting the appropriate consortium design strategy requires careful consideration of application requirements, technical constraints, and performance priorities. The following guidelines assist researchers in matching design approaches to specific application contexts:

When to choose top-down design:

- Applications where functional outcome takes precedence over mechanistic understanding

- Environmental applications with complex, variable substrate mixtures

- Projects with limited prior knowledge of relevant microbial metabolism

- Systems where functional resilience to environmental fluctuations is critical

- Applications with technical constraints that preclude extensive genetic engineering

When to choose bottom-up design:

- Production of high-value chemicals requiring precise metabolic control

- Applications where regulatory approval requires fully defined system components

- Systems where intellectual property protection depends on precisely engineered strains

- Research aimed at elucidating specific microbial interactions or metabolic pathways

- Applications requiring modular optimization of specific pathway segments

Emerging hybrid approaches combine strengths from both strategies by using top-down selection to identify functional consortia followed by bottom-up analysis to elucidate key mechanisms and interactions [14]. This integrated approach leverages the functional power of naturally selected communities while generating knowledge for more rational design of future consortia. Additionally, computational modeling and machine learning approaches are increasingly being employed to predict consortium behavior and optimize composition, potentially bridging the gap between top-down discovery and bottom-up design [14].

Application Note: Pharmaceutical Synthesis via Distributed Metabolic Pathways

Protocol for the Synthesis of Paclitaxel Precursors

Application Overview This protocol details the establishment of a mutualistic co-culture of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of oxygenated taxanes, which are key precursors to the anti-cancer drug paclitaxel. This system leverages a distributed metabolic pathway to overcome limitations associated with expressing the entire biosynthetic pathway in a single host [2]. The design utilizes the high yield of the scaffold molecule, taxadiene, in the engineered bacterial strain and the superior capacity of the yeast for the cytochrome P450-mediated oxygenation reactions required for functionalization [2].

Experimental Workflow

Strain Engineering

- Engineered E. coli (TaxE1): Modify a suitable E. coli strain to heterologously express the metabolic pathway for the high-yield production of taxadiene. The specific genetic modifications required are detailed in the original research [2].

- Engineered S. cerevisiae (TaxS4): Modify S. cerevisiae BY4700 to express a fusion protein of taxadiene 5α-hydroxylase and its reductase (5αCYP-CPR). For optimal performance, the expression of this fusion protein should be driven by the strong, constitutive UAS-GPD promoter [2].

Co-culture Establishment

- Inoculation: Co-inoculate the engineered E. coli (TaxE1) and S. cerevisiae (TaxS4) strains into a defined bioreactor medium.

- Carbon Source: Use xylose as the sole carbon and energy source. This is critical for establishing a mutualistic relationship: E. coli metabolizes xylose and excretes acetate, which S. cerevisiae then uses as its sole carbon source without producing ethanol, a compound that inhibits E. coli growth [2].

- Initial Inoculum Ratio: Optimize the initial cell density ratio to ensure stable co-culture. A higher initial inoculum of yeast may be required to efficiently consume the acetate produced by E. coli and prevent its accumulation [2].

Fed-Batch Fermentation

- Process: Conduct the co-culture in a fed-batch bioreactor.

- Nutrient Feeding: Periodically feed additional xylose, nitrogen (ammonium), and phosphorous (phosphate) sources to ensure that nutrient limitation does not restrict yeast growth or overall system productivity [2].

- Environmental Control: Maintain standard fermentation conditions (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen) appropriate for the co-culture.

Product Quantification

- Sampling: Collect samples at regular intervals throughout the fermentation process.

- Analysis: Analyze culture samples using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) or other suitable chromatographic methods to identify and quantify taxadiene and oxygenated taxane products [2].

Performance Data

Table 1: Quantitative performance of the E. coli/S. cerevisiae co-culture system for oxygenated taxane production.

| Strain / Co-culture Configuration | Carbon Source | Fermentation Duration (h) | Oxygenated Taxane Titer (mg/L) | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaxE1 + TaxS1 (Initial) | Glucose | 72 | 2 | Proof of concept |

| TaxE1 + TaxS1 (Mutualistic) | Xylose | 72 | 4 | Eliminated ethanol inhibition |

| TaxE1 + TaxS1 (Optimized feeding) | Xylose | 90 | 16 | Improved yeast growth & acetate consumption |

| TaxE1 + TaxS4 (UAS-GPD promoter) | Xylose | 90 | 25 | Enhanced specific oxygenation activity in yeast |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential reagents and materials for the paclitaxel precursor synthesis co-culture system.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Engineered E. coli (TaxE1) | Chassis for high-yield production of the scaffold molecule, taxadiene. |

| Engineered S. cerevisiae (TaxS4) | Chassis for functionalizing taxadiene via cytochrome P450-mediated oxygenation. |

| Xylose | Sole carbon source; forces mutualism by preventing ethanol production and enabling cross-feeding of acetate. |

| UAS-GPD Promoter | Strong constitutive promoter used in yeast to drive high-level expression of the 5αCYP-CPR fusion protein. |

| Fed-Batch Bioreactor | Controlled environment for maintaining stable co-culture and supplying nutrients over an extended period. |

Application Note: Bioremediation of Complex Pollutants

Protocol for the Bioremediation of Pharmaceuticals in Biosolids

Application Overview This protocol describes the use of the white-rot fungus Trametes hirsuta for the treatment of municipal biosolids, with the objective of reducing biosolid volume and removing pharmaceutical compounds (PhACs). White-rot fungi are suitable for this application due to their non-specific extracellular and intracellular enzyme systems (e.g., laccase, peroxidases, cytochrome P-450), which can transform a wide spectrum of persistent organic pollutants [18].

Experimental Workflow

Fungal Strain and Inoculum Preparation

- Strain: Obtain Trametes hirsuta (e.g., IBB 450).

- Pelletization: Prepare the fungal strain in a pelletized mycelium form according to established methods to standardize the inoculation process [18].

- Inoculum: Use a blended mycelium suspension at a standardized concentration (e.g., 120 mg dry weight of WRF per gram of inoculum) [18].

Biosolid Slurry Preparation

- Source: Collect municipal biosolids from a wastewater treatment plant.

- Dilution: Dilute the biosolids to the desired concentration (e.g., 12% or 25% w/v) using a culture medium supplemented with low concentrations of glucose (0.4% w/v), yeast extract (0.4% w/v), and malt extract (1% w/v) to support initial fungal growth [18].

- Sterilization: Autoclave the biosolid-based media (45 min at 121°C and 19 psi) to eliminate endogenous microbial competition and ensure sterile conditions [18].

- PhACs Spiking (Optional): If investigating the removal of specific pharmaceuticals, spike the sterile bioslurry with target PhACs (e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and psychoactive compounds) and allow 72 hours for the compounds to reach sorption equilibrium with the biosolid matrix before inoculation [18].

Fungal Treatment and Cultivation

- Inoculation: Add the prepared fungal inoculum to the biosolid slurry.

- Culture Conditions: Incubate the cultures on a rotary shaker (e.g., 135 rpm) at 25°C for a treatment period of up to 35 days [18].

- Monitoring: Sacrifice replicate flasks at regular intervals (e.g., 5, 15, 20, 35 days) for analysis.

Analysis and Assessment

- Biosolid Reduction: Perform gravimetric measurements (e.g., dry weight determination) to quantify the reduction in biosolid mass. Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) can also be measured [18].

- Enzymatic Activity: Quantify laccase activity by monitoring the oxidation of 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) at 420 nm [18].

- PhACs Removal: Extract PhACs from the bioslurry and analyze their concentration using techniques like LC-MS to determine removal efficiency [18].

- Toxicity Assessment: Evaluate the reduction in toxicity of the treated biosolids using a seed germination assay (e.g., using Lactuca sativa) [18].

Performance Data

Table 3: Performance of Trametes hirsuta in bioremediating pharmaceutical compounds from biosolid slurry under different conditions.

| Biosolid Concentration | Target Pollutants | Treatment Duration (Days) | Removal Efficiency | Biosolid Mass Reduction | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12% (w/v) | 5 NSAIs* | 35 | ~100% | ~90% | High efficiency for NSAI removal. |

| 12% (w/v) | 2 PACs | 35 | ~20% | ~90% | Low removal of psychoactive compounds. |

| 25% (w/v) | 2 PACs | 35 | >50% | Not significantly affected | Higher biosolid content enhanced PACs removal. |

NSAIs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatories (e.g., naproxen, ketoprofen). *PACs: Psychoactive Compounds (e.g., carbamazepine, caffeine).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential reagents and materials for the fungal bioremediation protocol.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Trametes hirsuta (e.g., IBB 450) | White-rot fungus that produces non-specific oxidative enzymes (laccases) capable of degrading a wide range of pharmaceutical compounds. |

| Municipal Biosolids | The target waste matrix for treatment, containing organic matter, nutrients, and adsorbed pollutant compounds. |

| 2,2'-azino-bis(ABTS) | A chromogenic substrate used to spectrophotometrically quantify the activity of the extracellular enzyme laccase. |

| Culture Medium (Glucose, Yeast, Malt) | A low-nutrient supplement added to the biosolid slurry to support initial fungal growth and establishment. |

| Lactuca sativa (Lettuce) Seeds | Used in a bioassay to assess the reduction in toxicity of the biosolids after fungal treatment via seed germination tests. |

Engineering Tools and Assembly Methods for Robust Consortium Function

The engineering of synthetic microbial consortia represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, enabling complex biochemical tasks to be distributed across specialized microbial subpopulations. This approach mitigates the metabolic burden associated with implementing extensive genetic circuits in single strains and leverages natural ecological interactions for enhanced bioprocess stability and efficiency [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the toolkit for constructing these consortia rests on three foundational pillars: quorum sensing (QS) for intercellular communication, genetic circuits for programmed control, and biosensors for real-time metabolic monitoring. These components facilitate the design of sophisticated systems where microbial communities can perform distributed computation, specialized metabolite production, and environmental sensing with applications ranging from biomanufacturing to therapeutic intervention [19] [7].

The Quorum Sensing Toolkit

Orthogonal AHL Signaling Systems

Quorum sensing (QS) systems, particularly those based on acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), form the cornerstone of engineered cell-to-cell communication in microbial consortia. Their simplicity—often requiring only a single synthase enzyme (e.g., LuxI) for signal molecule production and a transcription factor for signal detection—makes them ideal for synthetic biology applications [19]. AHL molecules diffuse freely across cell membranes, and intracellularly, they bind their cognate transcription factors, forming complexes that activate specific promoters to drive downstream gene expression [19].

Advancing synthetic biology to the multicellular level requires multiple, non-interfering communication channels. A comprehensive study designed and characterized AHL-receiver devices from six different quorum-sensing systems: lux (Vibrio fischeri), rhl and las (Pseudomonas aeruginosa), cin (Rhizobium leguminosarum), tra (Agrobacterium tumefaciens), and rpa (Rhodopseudomonas palustris) [19]. The cognate AHL inducers for these systems are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Characterized AHL-Receiver Devices for Orthogonal Communication

| QS System | Cognate AHL Inducer | Maximum GFP Output (Relative to J23101 promoter) | EC50 (nM) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lux | 3-oxo-C6-HSL | 4.5 | 15.2 | High dynamic range, functional in co-culture [19] |

| las | 3-oxo-C12-HSL | 2.8 | 8.5 | Strong activation, useful for high-level expression [19] |

| rhl | C4-HSL | 1.5 | 25.1 | Lower basal expression, reduced metabolic burden [19] |

| tra | 3-oxo-C8-HSL | 3.2 | 12.8 | Demonstrated orthogonality with rpa system [19] |

| cin | C8-HSL | 2.1 | 30.4 | Moderate crosstalk profile [19] |

| rpa | p-coumaroyl-HSL | 5.0 | 5.5 | Highly orthogonal due to unique aromatic AHL structure [19] |

Quantifying and Managing Crosstalk

A critical challenge in deploying multiple QS systems is crosstalk, where an AHL molecule activates a non-cognate transcription factor (chemical crosstalk) or a transcription factor binds a non-cognate promoter (genetic crosstalk) [19]. The characterization of all cognate and non-cognate interactions among the six AHL systems revealed that each device possesses a unique crosstalk profile [19].

To manage this complexity, a software tool was developed to automatically select orthogonal communication channels from the characterized library [19]. This tool allows researchers to input their desired QS systems and operational concentration ranges, and it identifies combinations with minimal interference. Experimentally, this approach enabled the simultaneous use of three orthogonal communication channels in a polyclonal E. coli co-culture, demonstrating the feasibility of multiplexed control within a consortium [19].

Figure 1: AHL Quorum Sensing Mechanism. The AHL signal molecule diffuses into the cell and binds its cognate transcription factor. The resulting complex activates a specific QS promoter, initiating transcription of a downstream output gene [19].

Programming Consortia with Genetic Circuits and Ecological Interactions

Foundational Ecological Interactions for Consortium Design

Stable microbial consortia are engineered by programming defined ecological interactions between member populations. These interactions, implemented with genetic circuits, provide the framework for controlling population dynamics and ensuring the long-term stability of the community. The six primary pairwise interactions form the building blocks for more complex consortia [7].

Table 2: Engineered Ecological Interactions for Consortium Stability

| Interaction Type | Genetic Implementation Strategy | Effect on Strain A | Effect on Strain B | Application in Consortia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutualism | A consumes B's waste (e.g., acetate); B provides a essential nutrient to A [7] | + (Beneficial) | + (Beneficial) | Stable co-culture for distributed metabolic pathways [7] |

| Predator-Prey | Prey produces AHL to activate predator's antidote; predator produces AHL to induce prey's suicide gene [7] | - (Harmed) | + (Beneficial) | Oscillatory population dynamics for biocomputation [7] |

| Competition | Each strain expresses a bacteriocin toxin that kills the other strain [7] | - (Harmed) | - (Harmed) | Enforcing spatial segregation or controlled exclusion |

| Commensalism | Strain A secretes nisin, inducing tetracycline resistance in Strain B [7] | 0 (Neutral) | + (Beneficial) | Asymmetric support in a multi-strain community |

| Amensalism | Strain A produces an antibiotic that inhibits Strain B [7] | 0 (Neutral) | - (Harmed) | Controlling population ratios |

| Negative Feedback | Synchronized lysis circuit (SLC): QS triggers host lysis at high density [7] | Self-limiting | Self-limiting | Stabilizing competitive populations [7] |

Protocol: Implementing a Mutualistic Consortium for Metabolic Engineering

Application: Distributed taxane biosynthesis pathway between E. coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [7].

Principle: Division of labor reduces metabolic burden and improves functional stability. E. coli performs the upstream part of the pathway but produces growth-inhibiting acetate. S. cerevisiae consumes the acetate as a carbon source while performing the downstream pathway steps, creating a mutualistic cycle [7].

Materials:

- Engineered E. coli Strain: Contains genes for upstream taxane pathway modules; excretes acetate.

- Engineered S. cerevisiae Strain: Engineered to use acetate as sole carbon source; contains genes for downstream taxane pathway modules.

- Culture Medium: Defined minimal medium without carbon sources that support S. cerevisiae growth independently of acetate.

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow monocultures of each engineered strain to mid-exponential phase.

- Co-culture Initiation: Mix strains at a predetermined ratio (e.g., 1:1 cell count) in fresh minimal medium.