HITI Revolution: Mastering Homology-Independent Targeted Integration for Advanced Gene Therapies

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Homology-Independent Targeted Integration (HITI), a groundbreaking CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing technology that leverages the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway.

HITI Revolution: Mastering Homology-Independent Targeted Integration for Advanced Gene Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Homology-Independent Targeted Integration (HITI), a groundbreaking CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing technology that leverages the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we examine HITI's core mechanism enabling efficient transgene integration in both dividing and non-dividing cells—a key advantage over homology-directed repair. The content details practical methodologies from vector design to clinical manufacturing, addresses critical troubleshooting for genotoxicity and optimization, and presents validation data and comparative analysis against other editing strategies. Supported by recent preclinical and emerging clinical evidence, this resource underscores HITI's transformative potential in developing durable therapies for dominant genetic disorders, cancer, and beyond.

Beyond HDR: Unveiling the Core Principles and Advantages of HITI Technology

Homology-Independent Targeted Integration (HITI) is a CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing technique that leverages the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway for targeted transgene insertion. Unlike homology-directed repair (HDR), which requires homologous templates and active cell division, HITI operates throughout the cell cycle, enabling efficient gene editing in both dividing and non-dividing cells. This mechanism provides substantial advantages for therapeutic applications in primary cells, including hematopoietic stem cells and T lymphocytes, offering improved efficiency and simplified manufacturing for next-generation cell therapies.

Homology-Independent Targeted Integration (HITI) represents a paradigm shift in CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing by exploiting the cell's predominant DNA repair pathway—non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). This approach circumvents the major limitation of homology-directed repair (HDR), which is inherently inefficient in many therapeutically relevant primary cells due to its dependence on specific cell cycle phases and complex repair machinery [1] [2].

The fundamental innovation of HITI lies in its engineered donor design, which incorporates Cas9 target sites as reverse complements of the genomic target. This architecture enables bidirectional selection for proper integration orientation: correctly oriented insertions disrupt the Cas9 recognition site, protecting them from repeated cleavage, while reverse integrations maintain functional Cas9 target sites, allowing for repeated cleavage until proper orientation is achieved [3]. This self-correcting mechanism drives high-fidelity integration without requiring homologous recombination machinery.

Molecular Mechanism and Comparative Advantages

HITI Workflow and Key Components

The HITI mechanism employs CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes to create simultaneous double-strand breaks at both the genomic target locus and the donor DNA template. The cellular NHEJ machinery then ligates these broken ends, resulting in precise integration of the transgene into the designated genomic site [1] [2].

Comparative Analysis: HITI vs. HDR

Table 1: Comparative analysis of HITI versus HDR integration mechanisms

| Parameter | HITI | HDR |

|---|---|---|

| Repair Pathway | NHEJ [1] | Homology-directed repair [2] |

| Cell Cycle Dependence | Cell cycle independent [2] | Requires S/G2 phases [2] |

| Efficiency in Primary Cells | High (~21% in HSPCs) [1] | Limited [1] |

| Template Design | Reverse complement Cas9 target sites [3] | Homology arms [2] |

| Therapeutic Applications | HSPCs, T cells, post-mitotic cells [1] [2] | Limited to dividing cells [2] |

| Manufacturing Simplicity | Compatible with non-activated T cells [4] | Requires T cell activation [4] |

Experimental Implementation and Workflow

HITI Protocol for CAR-T Cell Engineering

The following protocol outlines HITI-mediated CAR knock-in into the TRAC locus for clinical-scale CAR-T cell manufacturing, adaptable to other primary cell types [2]:

Day 0: T Cell Isolation and Preparation

- Isolate primary human T cells from leukopaks using negative selection (EasySep Human T Cell Isolation Kit)

- Optional: For HITI, T cell activation is not required, unlike HDR-based approaches [4]

- Resuspend cells in TexMACS medium supplemented with IL-7 (12.5 ng/mL) and IL-15 (12.5 ng/mL) with 3% human AB serum

Day 2: Electroporation and HITI Knock-in

- Remove Dynabeads if activation was performed

- Wash cells once in electroporation buffer and resuspend at 2×10⁸ cells/mL

- Prepare RNP complex:

- Mix wild-type Cas9 (61 μM) with sgRNA (125 μM) at 2:1 molar ratio

- Incubate 10 minutes at room temperature

- Add nanoplasmid DNA (3 mg/mL) and incubate ≥10 minutes to allow RNP cutting of nanoplasmid

- Electroporate using Maxcyte GTx with Expanded T Cell 4 protocol (activated T cells) or Resting T Cell 14-3 protocol (non-activated T cells)

- Rest cells in electroporation buffer for 30 minutes post-electroporation

- Transfer to final G-Rex vessels for expansion

Days 3-14: Expansion and Enrichment

- Expand cells maintaining concentration at ~1.5×10⁶/mL

- For enrichment, apply CRISPR EnrichMENT (CEMENT) using methotrexate (MTX) selection for cells expressing dihydrofolate reductaseL22F/F31S (DHFR-FS)

- MTX treatment enriches CAR+ T cells to approximately 80% purity [2]

- Harvest cells after 14-day process, yielding 5.5×10⁸–3.6×10⁹ CAR+ T cells from starting population of 5×10⁸ T cells [2]

Critical Reagent Specifications

Table 2: Essential research reagents for HITI-based genome editing

| Reagent | Specification | Function | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Protein | Wild-type (61 μM) [2] | Creates DSBs at target loci | Use high-purity, endotoxin-free grade |

| sgRNA | TRAC-targeting: 5'-GGGAATCAAAATCGGTGAAT-3' [2] | Guides Cas9 to specific genomic locus | Include mismatch base for optimal on-target performance [4] |

| Donor Template | Nanoplasmid (450bp backbone) [2] [4] | Delivers transgene for integration | Single cut site design yields higher KI efficiency vs. 0 or 2 cut sites [4] |

| Electroporation System | Maxcyte GTx [2] | Deliver RNP and donor to cells | Use preset Expanded T-Cell 4 protocol (activated) or Resting T cell 14-3 (non-activated) [2] |

| Selection System | DHFR-FS with methotrexate [2] | Enriches successfully edited cells | Shortened MTX exposure maintains cell viability while achieving ~80% purity [2] |

Therapeutic Applications and Performance Data

Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells (HSPCs)

HITI-mediated genome editing achieves approximately 21% stable editing efficiency in repopulating human mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs after transplantation into immunodeficient mice [1]. This approach, utilizing recombinant AAV serotype 6 vectors for donor delivery, demonstrates robust site-specific transgene integration at clinically relevant genetic loci, offering promising therapeutic potential for inherited blood disorders like leukocyte adhesion deficiency type 1 (LAD-1) [1].

CAR-T Cell Manufacturing

HITI enables non-viral, site-directed integration of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) transgenes into the TRAC locus, achieving at least 2-fold higher cell yields compared to HDR-based approaches [2] [5]. When combined with CEMENT enrichment, this platform generates therapeutically relevant doses of 5.5×10⁸–3.6×10⁹ CAR+ T cells from a starting population of 5×10⁸ T cells across a 14-day manufacturing process [2]. The resulting CAR-T cells demonstrate functional comparability to virally transduced counterparts while eliminating requirements for viral vector manufacturing [2].

In Vivo Therapeutic Applications

HITI has been successfully applied for in vivo gene correction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) models using AAV9 vectors, achieving editing of 1.4% of genomes in heart tissue leading to 30% transcript correction and restoration of 11% normal dystrophin levels [3]. This approach corrects mutations upstream of intron 19, potentially benefiting approximately 25% of DMD patients [3].

Safety Considerations and Limitations

Genotoxicity Assessment

Comprehensive safety profiling is essential for clinical translation of HITI-based therapies. Key considerations include:

- Off-target editing: Utilize in silico tools (COSMID, CCTop) for gRNA design and empirical methods (GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq) for off-target nomination [4]

- Structural variations: Employ long-read sequencing and single primer amplification to detect large deletions, translocations, and chromothripsis not captured by standard sequencing [6] [4]

- On-target integrity: Monitor chromosomal translocations using ddPCR, particularly for loci like TRAC where chromosome 14 aneuploidy has been reported [4]

Technical Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

While HITI offers significant advantages, several limitations require consideration:

- Random integration events: Sequencing reveals occasional integration of fragmentary and recombined AAV genomes at target sites [3]

- Optimization requirements: Maximal efficiency requires careful optimization of Cas9:donor ratios (1:5 optimal for DMD correction) [3]

- Vector design constraints: Donor templates must include appropriately oriented Cas9 target sites to enable the HITI mechanism [3]

HITI represents a significant advancement in CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology, particularly for therapeutic applications in non-dividing and primary cells. By leveraging the efficient NHEJ pathway and incorporating a self-correcting mechanism for integration orientation, HITI achieves robust transgene integration efficiencies that surpass traditional HDR-based approaches. The compatibility with non-viral donor templates and clinical-scale manufacturing platforms positions HITI as a transformative technology for next-generation cell and gene therapies, with demonstrated applications across hematopoietic stem cells, CAR-T engineering, and in vivo gene correction. As the field advances, continued refinement of safety assessment protocols and standardization of manufacturing processes will be essential for clinical translation.

The efficacy of Homology-Independent Targeted Integration (HITI) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) in non-dividing cells hinges on fundamental differences in the DNA repair pathways they exploit. Non-dividing, or post-mitotic, cells constitute the majority of adult mammalian tissues, presenting a significant barrier for therapeutic genome editing strategies that rely on HDR [7] [8]. The core differentiator lies in the activity levels of their respective DNA repair mechanisms across the cell cycle. HDR is largely restricted to the S and G2 phases, as it requires a sister chromatid template, which is only available after DNA replication [4] [9]. In contrast, the Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway, which facilitates HITI, is active throughout all phases of the cell cycle, including the quiescent G0 phase, making it the predominant repair mechanism in non-dividing cells [4] [8]. This fundamental biological distinction is the primary reason HITI has emerged as a powerful tool for in vivo gene therapy in tissues such as the brain, retina, and airway epithelium [10] [11] [8].

Molecular Mechanisms: A Pathway-Centric View

The HDR Pathway and Its Cell Cycle Dependence

HDR is a high-fidelity process that uses a homologous DNA template to accurately repair double-strand breaks (DSBs).

- Key Steps: The pathway initiates with the MRN complex (MRE11-Rad50-NBS1) binding to the DSB. 5' to 3' resection of the DNA ends creates single-stranded overhangs, which are bound by Replication Protein A (RPA). The essential recombinase Rad51, aided by BRCA2 and PALB2, then displaces RPA to form a nucleoprotein filament. This filament performs a homology search and invades the sister chromatid, forming a D-loop structure. DNA polymerase then uses the sister chromatid as a template to synthesize the missing genetic information, leading to accurate repair [9].

- The Critical Limitation: The requirement for a sister chromatid as a repair template confines HDR activity almost exclusively to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [4] [9]. Consequently, in non-dividing cells, which have exited the cell cycle, HDR is inefficient or inactive, severely limiting its application for in vivo therapeutic editing [7] [8].

The NHEJ Pathway and Its Application in HITI

NHEJ is a more error-prone but universally available repair pathway that directly ligates broken DNA ends.

- Key Steps: The Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer binds to the DSB ends, recruiting DNA-PKcs. The ends may be processed by nucleases like Artemis and filled in by polymerases before being ligated by the DNA Ligase IV/XRCC4/XLF complex [9].

- The HITI Strategy: HITI co-opts the NHEJ machinery. A CRISPR-Cas9 system creates simultaneous DSBs in the genomic target and a donor DNA vector containing the transgene flanked by Cas9 cut sites. The linearized donor is then integrated into the genomic break via NHEJ [4] [8]. A key feature is that correct, forward-oriented integration disrupts the original Cas9/gRNA target sequence, preventing re-cutting, while incorrect integrations remain susceptible to further cleavage and repair attempts [8].

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes

The following tables summarize key experimental data that highlight the efficiency advantage of HITI over HDR, particularly in non-dividing cells.

Table 1: Knock-in Efficiency Comparison in Different Cell Types

| Cell Type / Model | Target Locus | HITI Knock-in Efficiency | HDR Knock-in Efficiency | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Primary Neurons (in vitro) | Tubb3 | ~55.9% (relative in transfected cells) | Minimal to none | [8] |

| HEK293 GFP-Correction Line | GFP-IRES | Significantly higher than HDR | Lower than HITI | [8] |

| Human CD34+ HSPCs (in vivo engraftment) | Clinically relevant locus | ~21% (stable in repopulating cells) | Inefficient (NHEJ is primary pathway) | [12] |

| CAR-T Cell Manufacturing (TRAC Locus) | TRAC | At least 2-fold higher CAR+ cell yield | Lower yield | [2] |

| Adult Mouse Visual Cortex (in vivo) | Tubb3 | Achieved knock-in | Not demonstrated | [8] |

Table 2: Analysis of HITI Editing Outcomes and Fidelity

| Parameter | Finding | Implication | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indel Frequency at Junction | Majority of forward knock-ins showed no indels | HITI can achieve precise integration | [8] |

| Directional Bias | Strong bias for forward-oriented integration | Strategy enforces correct orientation of the transgene | [8] |

| Therapeutic Protein Restoration | Restored 11% of normal dystrophin levels in mouse heart (DMD model) | Functional protein can be produced from HITI-edited genes | [13] |

| Genomic Toxicity | No evidence of off-target genomic toxicity in CAR-T cells; low-level aneuploidy monitored | Acceptable safety profile for therapeutic development | [4] [2] |

Experimental Protocol: HITI-Mediated Gene Knock-in in Primary T Cells

This protocol details the application of HITI for site-specific integration of a Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) into the TRAC locus of primary human T cells, as described by Balke-Want et al. [2].

Materials and Reagents

- Primary Cells: Human T cells isolated from leukopaks.

- Activation Reagent: Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28.

- Cell Culture Media: TexMACS medium supplemented with IL-7 and IL-15 (12.5 ng/mL each).

- CRISPR Components:

- Wild-type Cas9 protein

- sgRNA targeting TRAC locus (sequence: 5'-GGGAATCAAAATCGGTGAAT-3')

- HITI Donor Template: Nanoplasmid DNA (3 mg/mL) containing the anti-GD2 CAR expression cassette flanked by the TRAC sgRNA target sequences. The nanoplasmid backbone is only ~430 bp, which helps reduce transgene silencing and cytotoxicity [4] [2].

- Electroporation System: Maxcyte GTx with appropriate processing assemblies (e.g., OC-25×3 for small scale, CL1.1 for large scale).

- Electroporation Buffer: Proprietary buffer from Maxcyte.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Day 0: T Cell Isolation and Activation

- Isolate T cells from a leukopak using negative selection.

- Activate the T cells using CD3/CD28 activation beads at a 1:1 bead-to-cell ratio.

- Culture cells in supplemented TexMACS medium.

Day 2: Electroporation

- Remove activation beads magnetically and wash cells once in electroporation buffer.

- Resuspend T cells at a concentration of 2 × 10^8 cells/mL.

- Prepare RNP Complex: Mix wild-type Cas9 and TRAC sgRNA at a 2:1 molar ratio (e.g., 61 µM Cas9 with 125 µM sgRNA) and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

- Formulate Electroporation Mix: Add the required amount of nanoplasmid DNA (e.g., 5-10 µg per 5 million cells) to the pre-formed RNP complex. Incubate for at least 10 minutes to allow Cas9 to linearize the nanoplasmid donor.

- Combine the cell suspension with the RNP/nanoplasmid mix.

- Electroporation: Transfer the mixture to a Maxcyte GTx processing assembly and electroporate using the "Expanded T cell 4" protocol.

- Post-Electroporation Recovery: After electroporation, rest the cells in the processing assembly for 30 minutes before transferring them back into culture vessels with fresh, supplemented medium.

Days 3-14: Cell Expansion and Analysis

- Expand the edited T cells, maintaining the cell concentration at approximately 1.5 × 10^6 cells/mL.

- Enrichment (Optional): To enrich for successfully edited cells, implement the CEMENT strategy by incorporating a mutant DHFR-FS gene in the HITI donor. Between days 5 and 10, treat cultures with Methotrexate (MTX) to select for transgene-positive cells, which can achieve ~80% purity [4] [2].

- Analysis: On day 14, harvest cells and analyze CAR integration efficiency via flow cytometry, and assess functionality and safety through appropriate assays (e.g., cytotoxicity, cytokine release, ddPCR for karyotype) [4] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HITI

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HITI Workflows

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoplasmid DNA | Minimal plasmid backbone (~430 bp) lacking bacterial antibiotic resistance genes, reducing silencing and improving biosafety [4] [2]. | Preferred donor template for non-viral HITI in T cells. |

| Cas9 RNP Complex | Pre-complexed Ribonucleoprotein of Cas9 and sgRNA; enables rapid, transient nuclease activity with reduced off-target effects. | Standard for electroporation-based delivery in primary cells. |

| NHEJ Inhibitor (e.g., NU7026) | Small molecule inhibitor of DNA-PKcs, a key NHEJ protein. Used to confirm HITI is NHEJ-dependent [8]. | Mechanistic validation in control experiments. |

| Enrichment Marker (DHFR-FS) | Mutant dihydrofolate reductase conferring resistance to methotrexate. Allows for pharmacological selection of edited cells (CEMENT) [4] [2]. | Enrichment of HITI-edited CAR-T cells to high purity. |

| rAAV Vectors (e.g., serotype 9) | Highly efficient delivery vehicle for in vivo gene editing, particularly in tissues like muscle and retina [13] [8]. | In vivo HITI delivery for DMD therapy in mouse models. |

| In Silico Off-Target Prediction Tools (CCTop, COSMID) | Computational tools to screen and select gRNAs with high on-target and minimal off-target activity during design phase [4]. | Pre-experimental gRNA design and risk mitigation. |

Critical Considerations and Concluding Remarks

While HITI overcomes the major limitation of HDR in non-dividing cells, several aspects require careful consideration for experimental and therapeutic application.

- On-Target Genomic Aberrations: CRISPR-Cas9 editing, including HITI, can lead to unintended on-target outcomes such as large deletions, translocations, or chromosomal aneuploidy [4]. It is crucial to employ comprehensive sequencing methods (e.g., long-read sequencing, ddPCR) to monitor these events.

- Donor Design is Critical: The configuration of the donor DNA significantly impacts efficiency and precision. Using a single cut-site (1cs) donor and minimizing bacterial plasmid sequences in the final integrated product (e.g., using minicircles or nanoplasmids) enhances performance and reduces the risk of unwanted immune responses or silencing [4] [8].

- Therapeutic Scope: HITI is exceptionally well-suited for knock-in of large transgenes (e.g., CARs, full-length dystrophin mini-genes) to restore or introduce function [13] [2]. However, it is not suitable for directly correcting point mutations without an accompanying knock-in strategy, a limitation that base or prime editing may address [10] [7].

In conclusion, the core differentiator establishing HITI as a transformative technology is its exploitation of the NHEJ pathway, a ubiquitous DNA repair mechanism active in both dividing and non-dividing cells. This fundamental advantage over the cell cycle-dependent HDR pathway enables robust and precise gene integration in a wide range of therapeutically relevant post-mitotic tissues, opening new avenues for curing genetic diseases.

Homology-independent targeted integration (HITI) is a sophisticated genome-editing technique that facilitates precise DNA insertion into specific genomic loci without the need for homologous templates. Unlike homology-directed repair (HDR), which requires a template with homologous arms and is primarily active in dividing cells, HITI leverages the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway, making it effective in both dividing and non-dividing cells [2] [14]. This capability is particularly valuable for therapeutic applications in post-mitotic cells, such as neurons and photoreceptors.

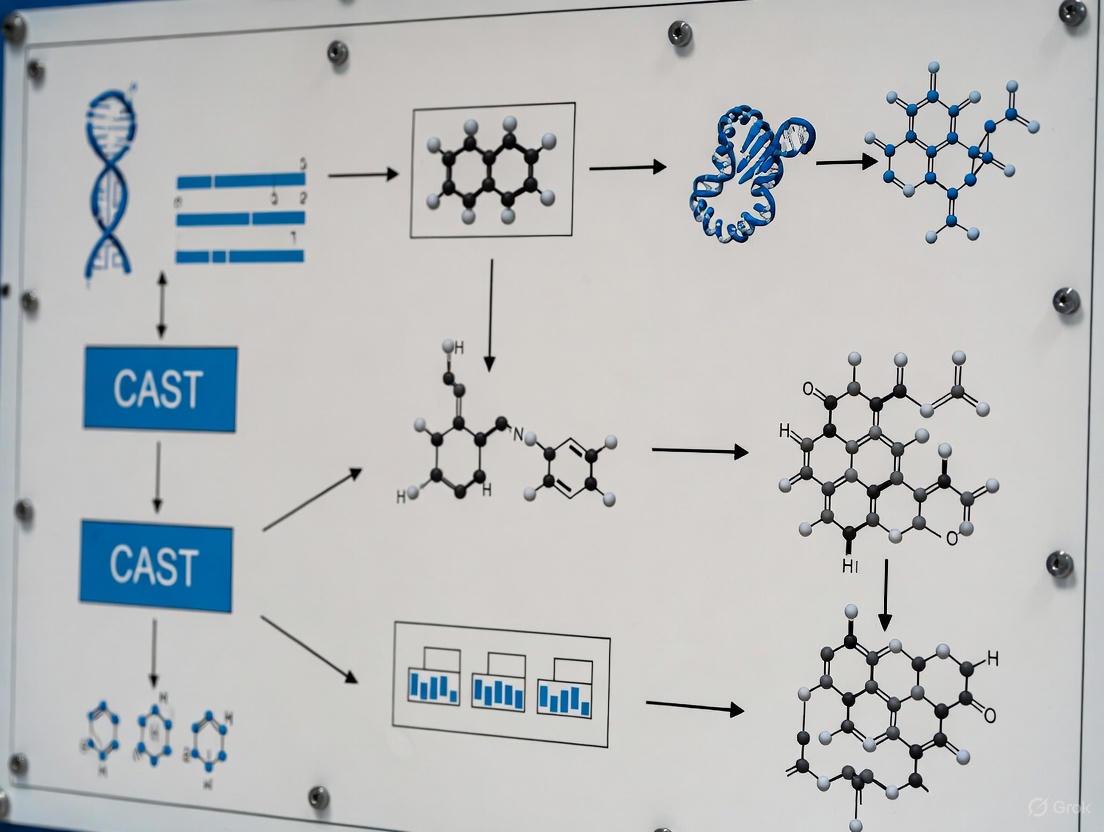

The foundational principle of HITI involves using CRISPR/Cas9 to create a double-strand break (DSB) at a predetermined genomic target site. A donor DNA construct, flanked by the same CRISPR/Cas9 target sequences in the same orientation as the genomic target, is provided. When Cas9 cleaves both the genomic locus and the donor DNA, the cellular NHEJ machinery ligates the donor fragment into the DSB, resulting in precise integration [2] [15]. This review details the HITI workflow and protocols, contextualized within the emerging research on CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems for HITI, providing a practical guide for its application in genetic research and therapeutic development [14].

The Core HITI Mechanism: A Comparative Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and comparative outcomes of the HITI mechanism alongside the traditional HDR pathway.

Key Protocol Steps for HITI-Mediated Knock-in

The successful implementation of HITI requires careful execution of the following protocol, optimized for primary human T cells but adaptable to other cell types [2]:

- sgRNA Design and Complex Formation: Design sgRNAs to target a specific genomic locus (e.g., the TRAC locus for CAR-T cell generation). Synthesize the sgRNA and complex it with wild-type Cas9 protein at a molar ratio of 2:1 (sgRNA:Cas9). Incubate the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex for 10 minutes at room temperature [2].

- Donor Template Preparation: Clone the transgene of interest (e.g., a GD2-CAR) into a nanoplasmid donor vector. This vector should be optimized for gene therapy, featuring a minimal backbone (e.g., ~430 bp R6K origin) to prevent transgene silencing. The transgene must be flanked by the same sgRNA target sequences recognized by the RNP complex. Add this nanoplasmid DNA directly to the pre-formed RNP complex and incubate for at least 10 minutes to allow Cas9 to pre-cleave the donor plasmid [2].

- Cell Preparation and Electroporation: Isolate primary human T cells and activate them with CD3/CD28 beads. On day 2 post-activation, remove the beads and wash the cells. Resuspend the cells in electroporation buffer at a concentration of 2 × 10^8 cells/mL. Combine the cell suspension with the RNP/nanoplasmid mixture and electroporate using a system like the Maxcyte GTx. For activated T cells, use the "Expanded T cell 4" protocol; for non-activated cells, use the "Resting T cell 14–3" protocol and stimulate immediately after electroporation [2].

- Post-Electroporation Recovery and Culture: After electroporation, rest the cells in the electroporation buffer for 30 minutes. Then, transfer them to culture vessels containing TexMACS media supplemented with cytokines (e.g., IL-7 and IL-15 at 12.5 ng/mL each) and human serum. Maintain the cells at a concentration of approximately 1.5 × 10^6 cells/mL, expanding the culture volume as needed [2].

- Enrichment of Knock-in Cells (CEMENT): To enrich for successfully edited cells, incorporate a selection marker like dihydrofolate reductaseL22F/F31S (DHFR-FS) into the donor construct. Between days 4 and 10 post-electroporation, add a selection agent such as methotrexate (MTX) to the culture. This enriches the population of CAR-positive T cells to approximately 80% purity [2].

Quantitative Performance of HITI in Practice

The efficiency and yield of HITI have been quantitatively evaluated in pre-clinical studies, demonstrating its potential for clinical application. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from a study generating anti-GD2 CAR-T cells.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of HITI-Mediated CAR Knock-in in Primary Human T Cells [2]

| Parameter | Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Knock-in Efficiency | ~80% purity post-CEMENT | HITI into the TRAC locus followed by methotrexate selection [2]. |

| Cell Yield | 5.5 × 10^8 – 3.6 × 10^9 CAR+ T cells | Starting from 5 × 10^8 T cells in a 14-day manufacturing process [2]. |

| Comparison to HDR | ≥2-fold higher yield | HITI yielded at least twice as many CAR-positive T cells as HDR using the same nanoplasmid donor [2]. |

| In Vivo Rodent Efficacy | Effective tumor control | HITI/CEMENT GD2 CAR-T cells mediated control of metastatic neuroblastoma in vivo [2]. |

| Therapeutic Transgene Size | Demonstrated with large constructs | HITI is effective for transgenes >5 kb [2]. |

The application of HITI extends beyond immunology to other fields, such as treating inherited retinal dystrophies. For instance, HITI-mediated gene insertion of a normal RHO gene into rod photoreceptor cells achieved integration in 80% to 90% of transduced cells and effectively restored visual function in mutant mouse models [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HITI

A successful HITI experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table catalogs the essential components of the HITI workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for the HITI Workflow [2] [15]

| Reagent / Tool | Function in HITI Workflow | Specifications & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Induces a precise DSB at the genomic target and pre-cleaves the donor template. | Wild-type S. pyogenes Cas9 protein complexed with target-specific sgRNA as an RNP complex [2]. |

| HITI Donor Vector | Provides the transgene for integration into the DSB. | Nanoplasmid with minimal backbone (e.g., R6K origin); transgene flanked by gRNA target sites [2]. Can also be delivered via AAV [15]. |

| Electroporation System | Enables efficient co-delivery of RNP and donor DNA into the target cells. | Instruments like the Maxcyte GTx with optimized protocols for specific cell types (e.g., activated or resting T cells) [2]. |

| Selection System | Enriches for cells with successful knock-in. | Integration of a selection marker (e.g., DHFR-FS) allowing for drug-based selection (e.g., with Methotrexate) in the CEMENT protocol [2]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Cytokines | Supports cell viability, recovery, and expansion post-electroporation. | Specialized media (e.g., TexMACS) supplemented with cytokines like IL-7 and IL-15 for T cell culture [2]. |

HITI in the Context of CAST Systems

The workflow and logical progression of HITI technology, particularly its relationship with newer CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems, can be visualized as follows. CAST systems represent a cutting-edge evolution in homology-independent integration, leveraging RNA-guided mechanisms for precise DNA insertion.

HITI serves as a robust, well-characterized platform for homology-independent integration. Its development addressed a critical limitation of HDR—dependence on the cell cycle [14]. The principles and workflows established by HITI provide a foundational understanding for exploring and utilizing more advanced systems like CAST, which utilize RNA-guided transposases for targeted DNA insertion without creating double-strand breaks in the recipient genome [14]. This positions HITI as a crucial technological milestone and a reliable protocol for current therapeutic and research applications.

Allele-Independent Editing and Stable Expression in Proliferating Tissues

CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems represent a transformative advance in genome engineering, enabling precise, targeted integration of large DNA sequences without relying on the host cell's DNA repair mechanisms. This application note details the key advantages of CAST systems, focusing on their allele-independent editing capability and capacity for stable transgene expression in proliferating cells. We provide a detailed experimental protocol for implementing a type I-F CAST system for targeted gene integration in human cells, based on the structurally engineered PseCAST system [16].

Key Advantages of CAST Systems

Allele-Independent Gene Editing

Traditional CRISPR-Cas9 editing requires cellular repair pathways (HDR or NHEJ) that are inefficient, cell-type dependent, and can produce heterogeneous editing outcomes [17] [18]. In contrast, CAST systems function independently of these pathways, leveraging a completely different mechanism for DNA integration:

- No Double-Strand Break Dependency: CAST systems catalyze the direct insertion of large DNA fragments through a transposition mechanism that bypasses DSBs, eliminating the associated DNA damage response, p53 activation, and unintended indel mutations [16] [18].

- Homology-Independent Integration: The insertion process does not require homologous sequences or donor DNA templates with extensive homology arms, simplifying vector design and improving reproducibility [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Genome Engineering Platforms

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 HDR | HITI | CAST Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editing Mechanism | Homology-Directed Repair | Non-Homologous End Joining | RNA-guided transposition |

| Dependency on DSBs | Yes | Yes | No |

| Payload Capacity | Limited (few kb) | Limited (few kb) | Multi-kilobase (kb-scale) |

| Allele Independence | Limited (requires HDR) | Limited | Yes |

| Product Purity | Low (mixed outcomes) | Low (high indel rate) | High (precise, homogeneous) |

Stable Expression in Proliferating Tissues

CAST systems facilitate long-term transgene expression through specific integration mechanisms suited for dividing cells:

- Faithful Copy Number Integration: CAST systems typically integrate a single, full-length copy of the donor transgene, avoiding the multi-copy, concatemeric insertions common with viral vectors that can lead to gene silencing [18].

- Durable Expression in Proliferating Cells: Once integrated into the host genome, the transgene is replicated and partitioned into daughter cells during cell division, enabling persistent expression [16] [18]. This is critical for therapeutic applications involving hematopoietic stem cells or actively dividing tissues.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of CAST Systems in Recent Studies

| CAST System | Target Cell Type | Integration Efficiency | Payload Size | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PseCAST (I-F) | Human cells [16] | Improved efficiencies with engineered variants | Multi-kilobase | Demonstrated RNA-guided transposition in human cells |

| Type I-F CASTs | E. coli [18] | Highly specific and homogeneous integration | Kilobase-level | Superior product purity compared to other subtypes |

| Type V-K CASTs | Diverse bacteria [18] | Functional in challenging industrial strains | Kilobase-level | Enabled efficient genome editing without homologous recombination |

Experimental Protocol: Targeted Gene Insertion Using Type I-F CAST

This protocol describes the use of the engineered PseCAST system for targeted, DSB-free integration of a gene of interest into the genome of human cells.

Principle

The system consists of two core modules: a DNA targeting module (QCascade complex) that uses a guide RNA to locate a specific genomic site, and an integration module (TnsA, TnsB, TnsC transposase proteins) that catalyzes the excision of a donor gene from a plasmid and its insertion into the target site. This process is independent of the cell's DNA repair machinery [16].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CAST Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example or Note |

|---|---|---|

| PseCAST Plasmid System | Provides genes for CAST machinery (QCascade & TnsABC) | Deliver as plasmid DNA or mRNA [16] |

| Donor Plasmid | Contains transgene flanked by necessary recognition sequences | Must include transposon ends recognized by TnsA/B [16] |

| Guide RNA (crRNA) | Directs QCascade complex to specific genomic target | Design guide sequence complementary to target genomic DNA [16] |

| Human Cell Line | Target for gene integration | HEK293T or other relevant cell types |

| Transfection Reagent | For delivery of CAST components into cells | Use method suitable for your cell type (e.g., lipofection, electroporation) |

| Selection Antibiotics | For enriching successfully transfected cells | Optional, depends on donor plasmid design |

Procedure

Guide RNA and Donor Plasmid Design

- gRNA Design: Design a crRNA sequence with a 20-nt spacer complementary to your target genomic locus. For the PseCAST system, ensure the target site is adjacent to a 5'-CC-3' PAM sequence [16].

- Donor Plasmid Construction: Clone your gene of interest (GOI) into a donor plasmid, ensuring it is flanked by the specific transposon end sequences (e.g., attL and attR) recognized by the TnsA and TnsB transposase proteins [16].

Cell Preparation and Transfection

- Culture human cells (e.g., HEK293T) in appropriate medium until they are 60-80% confluent.

- Co-transfect the cells with the following components using a suitable transfection method:

- Plasmids encoding the PseCAST QCascade and TnsABC proteins.

- Plasmid expressing the designed crRNA.

- Donor plasmid containing the GOI.

Incubation and Expression

- Incubate the transfected cells for 48-72 hours under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂) to allow for expression of the CAST components and completion of the integration process.

Analysis and Validation

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA.

- Integration Efficiency Assessment: Use junctional PCR with one primer binding within the genomic target site and another binding within the integrated GOI to confirm precise insertion.

- Functional Assays: Perform relevant assays (e.g., flow cytometry, Western blot, enzymatic activity) to confirm stable expression of the integrated transgene.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

- Optimizing Expression: The large size of the type I-F CAST system (~8 kb coding sequence) can be a delivery challenge. Consider using mRNA delivery or split systems to improve efficiency [16].

- DNA Binding Bottleneck: The initial DNA binding by the QCascade complex can be a limiting factor. The use of structurally engineered PseCAST variants with enhanced DNA binding can mitigate this issue [16].

- Specificity Confirmation: Always sequence the integration junctions to verify on-target, precise insertion and rule out large-scale deletions or rearrangements.

The following diagram illustrates the core components and mechanism of a CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) system for targeted gene integration.

CAST systems provide a powerful and precise alternative to DSB-dependent editors, offering a unique combination of allele-independent editing and reliable long-term transgene expression. This makes them particularly suited for therapeutic applications requiring the integration of large genetic elements into dividing cell populations, such as in ex vivo hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy [16] [18]. The continuous engineering of CAST components promises further enhancements in efficiency and specificity, solidifying their role as a next-generation genome engineering tool.

From Bench to Bedside: HITI Workflow, Delivery Systems, and Therapeutic Applications

Within the rapidly advancing field of genome engineering, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-based systems have emerged as powerful tools for targeted DNA modification. For therapeutic applications and sophisticated disease modeling, a paramount goal is the efficient knock-in of large DNA fragments. This application note focuses on the design of donor templates to maximize knock-in efficiency, specifically within the context of the CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) system, a leading platform for homology-independent targeted integration. CAST systems facilitate the precise insertion of substantial genetic payloads without relying on endogenous DNA repair pathways, thereby offering a versatile solution for large-scale DNA engineering [19]. The following sections provide a detailed examination of CAST system performance, structured protocols for implementation, and key design principles to optimize donor templates for this innovative technology.

CAST systems represent a significant evolution in gene insertion technology by combining the programmability of CRISPR with the DNA integration capabilities of transposases. Unlike methods that create double-strand breaks (DSBs) and harness cellular repair mechanisms like homology-directed repair (HDR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), CAST systems facilitate a "cut-and-paste" transposition mechanism. This process is guided by a CRISPR RNA, which directs the integration complex to a specific genomic locus without inducing DSBs, thereby minimizing unintended on-target indels and off-target effects [19].

These systems are categorized into subtypes, with type I-F and type V-K being the most well-characterized. The performance of a CAST system, particularly its integration efficiency, is highly dependent on the design of the donor DNA template. The table below summarizes the documented performance of different CAST systems across various host organisms, highlighting the critical impact of donor size and design.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of CAST Systems for Large DNA Insertion

| CAST Subtype | Host System | Donor DNA Size | Reported Efficiency | Key Features & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I-F | Escherichia coli | ~15.4 kb | Nearly 100% [19] | Stable integration; high efficiency in prokaryotes. |

| Type I-F | HEK293 Cells | ~1.3 kb | ~1% [19] | Low editing efficiency in human cells. |

| Type V-K | Escherichia coli | Up to 30 kb | High [19] | Large cargo capacity; replicative pathway. |

| Type V-K (nAnil-TnsB fusion) | HEK293T (plasmid target) | 2.6 kb | 0.06% [19] | Early-stage development for eukaryotic use. |

| V-K (MG64-1) | HEK293 Cells (AAVS1 locus) | 3.2 kb | ~3% [19] | Identified via metagenomic mining; promising for therapeutics. |

| V-K (MG64-1) | Hep3B Cells | 3.6 kb | <0.05% [19] | Highlights significant cell-type dependency. |

Donor Template Design and Workflow Protocol

A critical component of the CAST system is the donor DNA plasmid, which must be meticulously designed to serve as an effective substrate for the transposase. The following workflow and detailed protocols outline the steps for designing the donor template, delivering the CAST components, and validating successful integration.

Critical Donor Plasmid Design Specifications

The efficiency of transposition is profoundly influenced by the architecture of the donor plasmid. Adherence to the following design principles is essential:

- Essential Flanking Sequences: The donor DNA sequence to be integrated must be flanked by the specific recognition sites for the transposase TnsB. These sites are non-negotiable for the transposition reaction to occur [19].

- Orientation of Recognition Sites: The TnsB recognition sites must be in an inverted repeat orientation relative to each other. This specific configuration is crucial for the assembly of the active transposase complex and subsequent excision and integration of the donor fragment [19].

- Cargo Placement: The genetic cargo of interest (e.g., a therapeutic gene or reporter) must be located between the two TnsB recognition sites. Any sequence outside these sites will not be integrated into the genome.

Delivery and Validation Protocol

This protocol is adapted for human cell lines such as HEK293T, utilizing the type V-K CAST system.

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for CAST Genome Editing

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Plasmid | Provides the DNA template for integration, flanked by TnsB sites. | Maximize plasmid quality (e.g., endotoxin-free); confirm inverted repeat orientation of TnsB sites. |

| Cas12k Expression Plasmid | Encodes the Cas protein for type V-K systems. | Alternative: Deliver as mRNA or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex to boost speed and reduce off-targets. |

| gRNA Expression Plasmid | Directs Cas12k to the specific genomic target site. | Critical to design gRNA with high on-target efficiency; verify PAM sequence (TTTV for Cas12k) is present. |

| TnsB & TniQ Expression Plasmids | Provide the transposase and accessory proteins for integration. | TniQ recruits TnsC to the Cas complex; optimal stoichiometry of components must be determined. |

| Transfection Reagent | Enables delivery of plasmids/molecules into cells. | For hard-to-transfect cells (e.g., iPSCs), electroporation is preferred [20]. |

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed HEK293T cells in an appropriate culture vessel to reach 70-90% confluency at the time of transfection.

- Complex Formation: Prepare the transfection mixture. A suggested starting ratio for the plasmids is Donor:Cas12k:gRNA:TnsB:TniQ = 5:2:2:2:2. This ratio requires empirical optimization for specific experimental conditions [19] [3].

- Transfection: Introduce the plasmid mixture into the cells using a high-efficiency transfection method suitable for the cell type.

- Incubation: Allow the cells to recover and express the integrated DNA for a minimum of 72 hours before analysis.

- Validation:

- Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): Design probes to detect the unique junction between the integrated donor and the genomic target site. This method provides absolute quantification of knock-in efficiency with high sensitivity [3] [21].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): For a comprehensive analysis of editing outcomes, design primers to create an amplicon spanning the integration site. NGS can precisely quantify the rate of correct integration and detect any spurious editing events [20].

Strategic Considerations for Enhancing Efficiency

Achieving high knock-in efficiency requires more than a correctly designed donor template. The following strategic factors are critical for success:

- Component Stoichiometry: The ratio of the delivered CAST components is a major determinant of efficiency. A higher relative amount of the donor plasmid has been shown to enhance knock-in rates in vivo. For instance, in a HITI-based DMD correction study, a Cas9:donor ratio of 1:5 yielded superior results compared to a 1:1 ratio [3]. Systematic titration of the donor, Cas protein, and transposase plasmids is highly recommended.

- Target Site Selection: Not all genomic loci are equally amenable to integration. Local chromatin architecture (e.g., open vs. closed) can dramatically influence efficiency [21] [22]. Furthermore, a study aiming to correct the SLC26A4 c.919-2A>G variant using HITI reported very low efficiency (0.15%), suggesting that the specific genomic context of that region was unfavorable for integration [20]. Preliminary screening of multiple gRNAs is advised.

- Minimizing Off-Target Effects: While CAST systems are more specific than DSB-dependent methods, off-target integration remains a concern [23]. The use of purified ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes instead of plasmid-based expression can reduce the duration of nuclease activity and potentially lower off-target events [22]. Comprehensive off-target analysis using unbiased methods like NGS is essential for therapeutic applications.

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of the type V-K CAST system, showing how the donor template and gRNA direct integration.

The efficacy of homology-independent targeted integration (HITI) for advanced genome editing is fundamentally constrained by the delivery vehicle efficiency. This application note provides a comparative analysis of two prominent delivery systems: Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) vectors and non-viral nanoplasmid DNA. Within the context of CRISPR-associated transposon (CAST) system research, the choice of delivery vehicle impacts critical parameters including packaging capacity, integration efficiency, immunogenicity, and scalability for therapeutic development. We present structured quantitative data, detailed protocols for both delivery methods, and key reagent solutions to inform strategic decision-making for research and drug development professionals.

Technical Comparison of Delivery Vehicles

The selection between AAV and nanoplasmid delivery systems requires careful consideration of their fundamental properties, which are summarized in the following table.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of AAV and Nanoplasmid Delivery Vehicles for HITI Applications

| Characteristic | AAV Vectors | Non-Viral Nanoplasmid |

|---|---|---|

| Packaging Capacity | Limited (<4.7 kb) [24] | Significantly larger; can accommodate entire CAST systems and donor templates [2] |

| Backbone Size | N/A (viral capsid) | ~430-500 bp minimal backbone [25] [2] |

| Selection System | N/A | RNA-OUT antibiotic-free selection [25] |

| Integration Mechanism | Primarily episomal; limited integration | Designed for NHEJ/HITI-mediated integration [2] |

| Immunogenicity | Moderate to high; pre-existing immunity common [26] | Lower immunogenicity profile [27] |

| Manufacturing Scalability | Complex and costly viral production [26] [27] | Simplified, cost-effective bacterial fermentation [25] |

| Typical HITI Efficiency | Varies by serotype and tissue (e.g., 20% in retinal cells) [20] | High in primary cells (e.g., 2-fold greater yield than HDR in T-cells) [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Nanoplasmid-Mediated HITI in Primary Human T-Cells

This protocol, adapted from Balke-Want et al. [2], details the knock-in of a therapeutic transgene into the TRAC locus using nanoplasmid DNA and HITI, achieving high yields of engineered cells suitable for clinical-scale manufacturing.

Key Reagents:

- Nanoplasmid DNA: Designed with R6K origin of replication and RNA-OUT selection marker, resuspended at 3 mg/mL in H₂O [2].

- Cells: Primary human T-cells isolated from leukopaks via negative selection.

- Activation: Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 at a 1:1 bead-to-cell ratio.

- Culture Media: TexMACS medium supplemented with IL-7 (12.5 ng/mL) and IL-15 (12.5 ng/mL).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Day 0: T-Cell Activation. Isolate T-cells and activate them with CD3/CD28 beads in culture media.

- Day 2: Electroporation Preparation.

- Magnetically remove activation beads.

- Count cells and wash once in electroporation buffer.

- Resuspend cells at a concentration of 2 × 10⁸ cells/mL.

- Prepare RNP complex by mixing wild-type Cas9 (61 µM) and sgRNA (125 µM) at a 2:1 molar ratio and incubating for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Add the required amount of nanoplasmid DNA (e.g., 5-10 µg per 5×10⁶ cells) to the pre-formed RNP complex and incubate for ≥10 minutes to allow RNP cleavage of the nanoplasmid.

- Day 2: Electroporation.

- Combine cell suspension with the RNP/nanoplasmid mixture.

- Electroporate using the Maxcyte GTx system with the "Expanded T cell 4" protocol for activated T-cells.

- Post-electroporation, rest cells in the electroporation buffer for 30 minutes before transferring them back into culture media.

- Days 3-14: Cell Expansion and Analysis.

- Expand cells in G-Rex vessels, maintaining a density of ~1.5 × 10⁶ cells/mL.

- Assess knock-in efficiency around Day 7-10 via flow cytometry for surface marker expression or genomic analysis.

- For enrichment, apply CRISPR EnrichMENT (CEMENT) using a selection marker like DHFR-FS and methotrexate to achieve >80% purity of knock-in cells [2].

The workflow for this protocol is illustrated below.

AAV-Mediated In Vivo HITI Delivery

This protocol outlines the use of recombinant AAV for delivering HITI components in vivo, a strategy constrained by the vector's limited packaging capacity but valuable for direct in vivo applications [24] [28].

Key Reagents:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Vector Design and Packaging:

- All-in-One AAV: Clone a compact Cas ortholog (e.g., Cas12f, IscB, or TnpB) and its guide RNA into a single AAV vector. This is suitable for edits <4.7 kb [24].

- Dual AAV System: Package the Cas nuclease and the HITI donor template (containing the transgene flanked by AAV inverted terminal repeats and CRISPR target sites) into separate AAV vectors. A third vector for sgRNA may be required [24].

- Vector Production and Purification: Produce high-titer rAAV vectors using standard triple-transfection in HEK293 cells or baculovirus-insect cell systems, followed by purification via ultracentrifugation or chromatography.

- In Vivo Administration:

- Dosage: Determine the optimal titer based on the target organ. High doses (e.g., >1e14 vg/kg for systemic delivery) are often needed but carry toxicity risks [26].

- Route of Administration: Inject via a route appropriate for the target tissue (e.g., systemic intravenous for liver, subretinal for retina [24] [20]).

- Efficiency and Safety Assessment:

- After 1-4 weeks, analyze target tissues for HITI integration efficiency using next-generation sequencing (NGS) [20].

- Assess potential off-target effects and immune responses (e.g., hepatotoxicity).

- Vector Design and Packaging:

The logical workflow for implementing an AAV-HITI strategy is as follows.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of HITI strategies relies on a core set of specialized reagents. The following table outlines essential solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HITI Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Key Features / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoplasmid DNA Backbone | Non-viral delivery vector for HITI templates [25] [2] | - ~430-500 bp minimal backbone [2]- R6K origin of replication- RNA-OUT antibiotic-free selection [25] |

| RNA-OUT Selection System | Antibiotic-free plasmid maintenance in bacteria [25] | - 150 bp antisense RNA represses toxic SacB marker- Allows high-yield manufacturing without antibiotic resistance genes |

| Compact Cas Orthologs | Enables all-in-one AAV packaging [24] | - Cas12f, IscB, TnpB, SaCas9, CjCas9- Small molecular size fits AAV capacity |

| Electroporation Systems | Non-viral delivery of RNP and nanoplasmid to primary cells [2] [29] | - Maxcyte GTx with optimized T-cell protocols- High viability and efficiency in sensitive primary cells |

| CRISPR EnrichMENT (CEMENT) | Postsynthetic enrichment of HITI-edited cells [2] | - Uses selection marker (e.g., DHFR-FS) and drug (Methotrexate)- Enriches knock-in cells to >80% purity |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The quantitative data and protocols presented herein underscore a clear technological trade-off. Nanoplasmids offer superior packaging capacity, simplified manufacturing, and high HITI efficiency in ex vivo settings like CAR-T cell manufacturing [2]. In contrast, AAV vectors provide excellent transduction efficiency for in vivo delivery but are severely limited by packaging constraints and immunogenicity concerns [26] [24].

For CAST system research, which often involves large multi-component assemblies, nanoplasmids currently present a more viable delivery solution for ex vivo applications. However, innovations in AAV technology, such as the development of hypercompact editors and trans-splicing systems, are crucial for advancing in vivo HITI-based therapies [24]. Future developments in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and other non-viral carriers may further bridge the gap between delivery efficiency and cargo capacity, opening new avenues for therapeutic genome editing [27].

Application Notes

The CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) system represents a transformative advancement in genome engineering, enabling homology-independent, RNA-guided integration of large DNA cargo. This technology is particularly suited for addressing loss-of-function genetic disorders, as it allows for the one-time, allele-agnostic installation of therapeutic genes at specific genomic loci without relying on double-strand break (DSB) repair pathways [30] [18]. Its application in vivo for complex tissues such as the retina and liver offers a promising therapeutic pathway for conditions that have been historically challenging to treat.

Key Advantages for In Vivo Therapy

CAST systems offer several distinct benefits for in vivo gene therapy compared to traditional CRISPR-Cas systems or viral gene addition:

- DSB-Free Integration: Unlike CRISPR-Cas9 which induces double-strand breaks, CAST systems facilitate "cut-and-paste" transposition, avoiding the inherent risks of indel formation, chromosomal translocations, and p53 activation associated with DSBs [30] [18].

- Large Cargo Capacity: CAST systems can integrate DNA fragments ranging from 1 kb to over 10 kb, enabling the delivery of full-length cDNA sequences for most genes, which is a significant limitation for prime editing technologies [30] [18].

- Homology- and Cell Cycle-Independence: The integration mechanism does not depend on host homology-directed repair (HDR) machinery, making it effective in both dividing and, crucially, non-dividing cells such as neurons and photoreceptors [19] [30].

- High Product Purity and Unidirectional Insertion: Evolved CAST (evoCAST) systems produce predominantly precise, unidirectional integration products with minimal byproduct formation, a key advantage for therapeutic safety and predictability [30].

Quantitative Profile of Advanced CAST Systems

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Evolved CAST Systems in Human Cells

| System | Average Integration Efficiency | Cargo Size Demonstrated | Indel Formation | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type PseCAST | < 0.1% | ~1.3 kb | Undetectable | Minimal baseline activity in human cells [30] |

| PseCAST + ClpX | ~1% | ~1.3 kb | Undetectable | Bacterial unfoldase supplement boosts activity [30] |

| Evolved CAST (evoCAST) | 10-25% (across 14 genomic loci) | Kilobase-scale | Undetectable | Protein-evolved variant; therapeutically relevant efficiency [30] |

| Type V-K CAST (MG64-1) | ~3% (at AAVS1 locus) | 3.2 - 3.6 kb | Data not specified | Identified via metagenomic mining [19] |

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols detail the application of CAST systems for in vivo gene therapy development for retinal degeneration and liver fibrosis. These methodologies are adapted from recent breakthrough studies and are designed for preclinical model systems.

Protocol 1: Targeted Gene Insertion for Retinal Degeneration in a Mouse Model

This protocol outlines the use of an evolved CAST system to install a healthy cDNA copy of a mutated gene into a defined "safe harbor" locus in retinal cells, providing a universal strategy for various loss-of-function mutations causing diseases like retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) [31] [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Retinal Gene Integration

| Reagent | Function | Example or Specification |

|---|---|---|

| evoCAST Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex | Catalyzes RNA-guided transposition | Purified evolved TnsA, TnsB, TnsC, and QCascade complex [30] |

| Target-Specific gRNA | Directs CAST complex to genomic locus | sgRNA targeting the 3' end of the ALB intron 1 or a safe harbor locus [30] |

| ssAAV Donor Template | Carries therapeutic transposon cargo | Single-stranded AAV vector containing therapeutic cDNA (e.g., CNGA1 for RP), flanked by the necessary ~150 bp transposon ends [32] [30] |

| Subretinal Injection Delivery System | Enables localized in vivo delivery | NanoFil syringe with a 36-gauge blunt-end needle [32] |

Detailed Methodology

Vector Design and Production:

- Clone the therapeutic cDNA (e.g., a 2.5 kb wild-type CNGA1 cDNA for a form of RP) into an ssAAV donor vector between the defined ~150 bp transposon ends recognized by the evoCAST system [30].

- Package the donor construct into an AAV serotype with high tropism for photoreceptor cells (e.g., AAV8, as used in retinal gene therapy studies) and purify via iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation [32].

- Complex the purified evoCAST proteins with the target-specific sgRNA to form the RNP complex.

In Vivo Delivery:

- Anesthetize 2-week-old Cnga1-/- mice using an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg) [32].

- Dilate pupils with a topical application of 0.5% tropicamide and 0.5% phenylephrine hydrochloride.

- Using a surgical microscope, make a small incision through the sclera behind the iris with a 32-gauge needle.

- Insert a 36-gauge blunt-end needle attached to a NanoFil syringe into the subretinal space.

- Co-inject a total of 1 µL containing the evoCAST RNP complex and the ssAAV donor template (∼1×10^12 vg/mL). A visible bleb confirms successful subretinal delivery [32] [30].

Functional and Structural Validation:

- Electroretinography (ERG): At 1-month and 3-months post-injection, record scotopic (rod-mediated) and photopic (cone-mediated) ERG responses under anesthesia to assess restoration of retinal function [32].

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): Perform in vivo longitudinal imaging to measure the thickness of the outer nuclear layer (ONL), which contains photoreceptor nuclei, to evaluate photoreceptor survival [32].

- Immunohistochemistry: At the study endpoint, analyze retinal sections for correct localization of the expressed therapeutic protein (e.g., CNGA1 protein in rod outer segments) and markers of healthy photoreceptors [32].

Diagram 1: Workflow for retinal gene integration.

Protocol 2: Nanoparticle-Mediated CAST Delivery for Liver Fibrosis

This protocol combines the high payload capacity of the CAST system with the targeted delivery capabilities of nanoparticles (NPs) to deliver a therapeutic transgene specifically to activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), the primary effector cells in liver fibrosis [33] [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Liver-Targeted Integration

| Reagent | Function | Example or Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery vehicle for CAST components | LNPs composed of ionizable lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid [33] |

| Targeting Ligand-Modified LNPs | Enables cell-specific targeting | LNPs surface-functionalized with a ligand for the PDGFβ receptor, highly expressed on activated HSCs [33] |

| mRNA Encoding CAST System | Provides transient expression of transposase | mRNA encoding evolved TnsA, TnsB, TnsC, and Cas12k/Cascade [30] |

| pDNA Donor Template | Carries therapeutic transposon | Plasmid DNA containing an anti-fibrotic gene (e.g., TGF-β antagonist) flanked by transposon ends [30] |

Detailed Methodology

LNP Formulation and Characterization:

- Formulate LNPs using microfluidic mixing to encapsulate both the mRNA encoding the evoCAST components and the pDNA donor template.

- Incorporate a PDGFβR-targeting peptide onto the LNP surface via PEG-lipid conjugation to achieve active targeting of activated HSCs [33].

- Characterize the final LNP preparation for size (aim for 80-150 nm), polydispersity index, zeta potential, and encapsulation efficiency using dynamic light scattering.

In Vivo Dosing in a Fibrosis Model:

- Induce liver fibrosis in a mouse model via repeated injections of carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄) or a methionine-choline-deficient (MCD) diet.

- Administer the targeted LNPs intravenously via the tail vein at a dose of ~0.5 mg/kg mRNA and ~1.0 mg/kg pDNA when fibrosis is established.

- Repeat dosing if necessary based on pharmacokinetic and efficacy data.

Efficacy and Safety Assessment:

- Histological Analysis: Score liver sections stained with Sirius Red or Masson's Trichrome to quantify collagen deposition and fibrosis stage.

- Biochemical Assays: Measure serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to monitor liver injury and treatment-related toxicity.

- qPCR and Western Blot: Quantify the integration efficiency of the therapeutic transgene and its expression in isolated HSCs. Assess the downregulation of pro-fibrotic markers (e.g., α-SMA, collagen I).

- Off-Target Analysis: Use GUIDE-seq or similar unbiased methods to profile the genome-wide specificity of integration [30].

Diagram 2: Nanoparticle delivery for liver therapy.

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of hematological malignancies, yet its widespread adoption faces significant challenges related to manufacturing complexity, cost, and scalability. Homology-Independent Targeted Insertion (HITI) has emerged as a powerful CRISPR-Cas9-based genome editing strategy that leverages the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway to enable efficient transgene integration. Unlike homology-directed repair (HDR), which is active only in specific cell cycle phases, NHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle, making HITI particularly suitable for engineering primary human T cells [2] [4].

The CAST system (CRISPR-associated transposase systems) for homology-independent targeted integration represents a paradigm shift in cell engineering methodologies. By eliminating the reliance on viral vectors and homology arms, HITI streamlines the manufacturing process while maintaining precision. This application note details the implementation of HITI for CAR insertion into the T Cell Receptor Alpha Constant (TRAC) locus, enabling simultaneous CAR expression and endogenous TCR disruption [2].

Theoretical Foundation: HITI Mechanism and Advantages

Molecular Mechanism of HITI

HITI utilizes CRISPR-Cas9 to create double-strand breaks (DSBs) at both the genomic target site and the donor DNA vector. The repair of these breaks via NHEJ results in the integration of the transgene cargo into the genome. The strategic design of the donor plasmid is crucial—it contains the CAR transgene flanked by Cas9 guide RNA (gRNA) target sequences that are reverse complements of the genomic target sites. This design enables re-cleavage and correction of reverse integrations, ensuring high efficiency and directional accuracy [2] [4] [35].

Comparative Advantages of HITI for CAR-T Manufacturing

Cell cycle independence represents a fundamental advantage of HITI over HDR-based approaches. Since NHEJ is active throughout all phases of the cell cycle, HITI enables efficient gene editing in both activated and non-activated T cells, providing greater flexibility in manufacturing workflows [4]. This characteristic is particularly valuable for clinical-scale production where cell synchronization is impractical.

Additional benefits include:

- Reduced manufacturing complexity: Elimination of homology arms simplifies vector design

- Higher yield: HITI generates at least 2-fold more CAR-T cells compared to HDR in primary human T cells [2]

- Versatile cargo capacity: Successful integration of large transgenes (>5 kb) including promoter elements and multiple exons [13] [3]

- Reduced pre-stimulation requirements: Potential for engineering non-activated T cells, potentially enhancing safety profiles [4]

Experimental Protocol: HITI-Mediated CAR-T Cell Generation

T Cell Isolation and Culture

Begin with fresh leukopaks from human donors. Isplicate T cells using negative selection with the EasySep Human T Cell Isolation Kit. Activate isolated T cells with Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 at a 1:1 bead-to-cell ratio. Culture cells in TexMACS medium supplemented with 12.5 ng/mL human IL-7 and 12.5 ng/mL IL-15, plus 3% human male AB serum. Maintain cells at approximately 1.5 × 10^6 cells/mL using appropriate culture vessels such as G-Rex plates [2].

gRNA Design and RNP Complex Formation

Design gRNAs targeting the TRAC locus (e.g., 5'-GGGAATCAAAATCGGTGAAT-3') [2]. For optimal results:

- Utilize bioinformatics tools (COSMID, CCTop) for gRNA selection and off-target prediction [4]

- Include a mismatch base in the gRNA sequence to enhance specificity

- Form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes by mixing wild-type Cas9 (61 µM) with sgRNA (125 µM) at a 2:1 molar ratio (sgRNA:Cas9)

- Incubate the mixture for 10 minutes at room temperature to allow RNP complex formation [2]

Nanoplasmid Donor Design and Preparation

Employ nanoplasmid vectors optimized for gene therapy applications. Key features include:

- R6K origin of replication and antibiotic-free selection system

- Minimal backbone size (~430 bp) to reduce cytotoxicity and prevent transgene silencing [2] [4]

- CAR expression cassette flanked by single gRNA cut sites (not two) for optimal efficiency [4]

- Anti-GD2 CAR transgene followed by enrichment markers (DHFR-FS, tEGFR, or tNGFR)

Clone the CAR construct into the nanoplasmid backbone using NheI and KpnI restriction sites. Produce high-quality nanoplasmid DNA at concentrations of 3 mg/mL in sterile water [2].

Electroporation Process

On day 2 post-activation, magnetically remove Dynabeads and count cells. Wash cells once in electroporation buffer and resuspend at 2 × 10^8 cells/mL. Add the predetermined amount of nanoplasmid DNA (typically 1-2 µg per 10^6 cells) to the pre-formed RNP complex and incubate for at least 10 minutes to allow RNP-mediated linearization of the nanoplasmid. Electroporate using the Maxcyte GTx system with the Expanded T Cell 4 protocol for activated T cells or the Resting T Cell 14-3 protocol for non-activated T cells. After electroporation, rest cells in the electroporation buffer for 30 minutes before transferring to final culture vessels [2] [4].

Post-Electroporation Culture and CRISPR EnrichMENT (CEMENT)

Following electroporation, continue culturing cells in cytokine-supplemented media. For enrichment of successfully edited cells, implement the CEMENT system using integrated selection markers:

Table 1: Enrichment Strategies for HITI-Edited CAR-T Cells

| Selection Method | Mechanism | Efficiency | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHFR-FS + Methotrexate | Metabolic selection with methotrexate-resistant dihydrofolate reductase | ~80% CAR+ purity [2] | Scalable, cost-effective, compatible with closed systems | Requires optimization of timing/dosage |

| tEGFR | Surface marker detection with anti-EGFR antibodies | Variable | Rapid detection, magnetic separation | Additional processing steps, yield loss |

| tNGFR | Surface marker detection with anti-NGFR antibodies | Variable | Rapid detection, magnetic separation | Additional processing steps, yield loss |

For DHFR-FS-based enrichment, add methotrexate (MTX) to the culture media during the expansion phase. Optimize MTX concentration and exposure duration to achieve effective selection while maintaining cell viability [2] [4].

Analytical and Functional Validation

Comprehensive characterization of HITI-edited CAR-T cells should include:

- Flow cytometry to quantify CAR expression and T cell phenotype

- ddPCR to assess vector copy number and chromosomal integrity

- Next-generation sequencing (GUIDE-seq, rhAMPSeq) to evaluate on-target efficiency and off-target effects [4]

- Functional assays including cytokine release, cytotoxicity, and exhaustion markers

- In vivo models to assess antitumor efficacy and persistence [2]

Performance Data and Benchmarking

Quantitative Assessment of HITI Efficiency

Rigorous evaluation of HITI-edited CAR-T cells from multiple donors demonstrates robust manufacturing outcomes:

Table 2: HITI Performance Metrics for Clinical-Scale CAR-T Manufacturing

| Parameter | HITI Performance | HDR Benchmark | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Yield | 5.5 × 10^8 – 3.6 × 10^9 CAR+ cells from 5 × 10^8 input T cells [2] | ~2-fold lower than HITI [2] | Meets clinical dosing requirements |

| Purity Post-CEMENT | ~80% CAR+ cells [2] | Variable without selection | Reduces need for additional purification |

| TRAC Disruption | Efficient knockout | Similar efficiency | Ensures endogenous TCR disruption |

| Off-target Editing | Minimal with optimized gRNA [2] [4] | Comparable | Acceptable safety profile |

| Functional Potency | Equivalent to viral transduced CAR-T cells [2] | Similar when achieved | Therapeutically relevant |

Process Workflow and Timeline

The complete HITI-based CAR-T manufacturing process requires 14 days from leukopak to final product, comparing favorably with viral manufacturing processes that typically require longer durations [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of HITI for CAR-T cell generation requires the following key reagents and systems:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HITI CAR-T Cell Generation

| Reagent/System | Function | Specifications | Alternative/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoplasmid DNA | Donor vector for CAR transgene | R6K origin, ~430 bp backbone, antibiotic-free selection [2] [4] | Superior to conventional plasmids for reduced cytotoxicity |

| High-fidelity Cas9 | CRISPR nuclease for DSB generation | Wild-type, 61 µM working concentration [2] | Can be substituted with other precise nucleases (e.g., Cas12a) |

| TRAC-specific gRNA | Targets TRAC locus for integration | Sequence: 5'-GGGAATCAAAATCGGTGAAT-3' [2] | Mismatch base included for enhanced specificity |

| Electroporation System | Delivery of RNP and donor DNA | Maxcyte GTx with Expanded T Cell protocol [2] | CL1.1 assembly for GMP-compatible scale-up |

| Enrichment Marker | Selection of successfully edited cells | DHFR-FS, tEGFR, or tNGFR [2] [4] | DHFR-FS enables methotrexate-based selection |

| Cell Culture Platform | T cell expansion and maintenance | G-Rex vessels with IL-7/IL-15 supplementation [2] | Enables gas-permeable rapid expansion |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common Challenges and Solutions

- Low Knock-in Efficiency: Optimize RNP:donor ratio (typically 2:1 molar ratio sgRNA:Cas9), verify nanoplasmid quality, and ensure proper electroporation parameters [2]

- Poor Cell Viability Post-Electroporation: Reduce DNA concentration, optimize electroporation buffer, and ensure proper post-electroporation recovery conditions [4]

- Incomplete TCR Disruption: Verify gRNA activity using T7E1 assay, optimize RNP concentration, and consider using multiple gRNAs targeting TRAC [2]

- Variable Enrichment Efficiency: Titrate methotrexate concentration (for DHFR-FS) and optimize timing of selection pressure application [2] [4]

Safety Assessment and Mitigation Strategies

Implement comprehensive genotoxicity screening:

- Utilize ddPCR to monitor chromosomal translocations and aneuploidy [4]

- Perform genome-wide insertion site analysis (LAM-PCR, TLA) to identify potential genotoxic events [2]

- Employ GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq for unbiased off-target nomination [4]

- Conduct long-term persistence studies in relevant animal models to assess functional safety [2]

HITI technology represents a significant advancement in non-viral CAR-T cell engineering, offering a streamlined manufacturing process that addresses critical bottlenecks in current cell therapy production. The protocol outlined herein enables researchers to consistently generate therapeutically relevant doses of CAR-T cells with functional properties equivalent to virally transduced products [2].

The integration of HITI with the CAST system framework provides a versatile platform that may be extended to other therapeutic cell engineering applications beyond CAR-T cells, including CAR-NK and CAR-macrophage therapies [36]. Future developments may focus on further enhancing the specificity and efficiency of integration through novel computational design tools [37] and potentially adapting the system for in vivo applications [36] [38] [39].

As the field advances, HITI-based manufacturing is poised to increase accessibility to CAR-T cell therapies by reducing costs and complexity while maintaining the high quality standards required for clinical applications [2].

Navigating Challenges: A Guide to Enhancing HITI Efficiency and Safety

The advent of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-associated transposases (CASTs) represents a significant leap forward for homology-independent targeted integration of large DNA cargos. Unlike traditional methods that rely on homology-directed repair (HDR), CAST systems facilitate precise, one-step integration of kilobase-scale transgenes without requiring donor DNA templates or cellular replication phases. This technology is particularly transformative for therapeutic applications, including gene correction therapies and the engineering of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells, where it enables mutation-agnostic treatments for loss-of-function genetic diseases. The efficiency of these systems, however, hinges on two critical experimental pillars: the rational design of guide RNAs (gRNAs) and the optimization of electroporation parameters for delivery. This application note provides a detailed framework for maximizing editing efficiency in CAST-based experiments through optimized gRNA design and electroporation protocols.

Comprehensive gRNA Design for CAST Systems

Designing a highly efficient gRNA is the foremost step for successful CAST system application. While CASTs use a nuclease-deficient Cas, the gRNA remains paramount for directing the complex to the specific genomic target. The principles of gRNA design for CAST systems share similarities with traditional CRISPR-Cas9 systems but require special considerations for homology-independent integration.

Fundamental gRNA Design Parameters

The foundational parameters for effective gRNA design focus on ensuring on-target activity and minimizing off-target effects. The target sequence must be unique within the genome to ensure specificity, a consideration especially critical in polyploid organisms or genomes with high repetitive content [40]. The target site must also be adjacent to a compatible Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence. While the canonical PAM for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 is 5'-NGG-3', CAST systems may utilize different Cas proteins with distinct PAM requirements [41]. The seed sequence (the 8–10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA targeting sequence) requires perfect homology to the target DNA, as mismatches in this region are known to significantly inhibit target binding and complex activity [41].

Advanced Design Strategies for Enhanced Specificity

To enhance the specificity of genomic integration, leverage multiplexed gRNA strategies. Using two or more gRNAs targeting the same locus can significantly increase the efficiency of large cargo integration and is particularly useful for defining the boundaries of large genomic deletions or inversions [41]. Furthermore, a thorough in silico off-target analysis is non-negotiable. Utilize BLAST and specialized gRNA design tools to scan the entire genome for sequences with partial homology to your gRNA, particularly those with mismatches in the 5' region distal to the PAM, which are more permissive of cleavage in nuclease-active systems [40].

The physical properties of the gRNA itself also contribute to its efficiency. Assess the secondary structure and Gibbs free energy of the synthesized gRNA. Stable secondary structures can occlude the spacer region, impairing its ability to bind the target DNA. Tools that predict secondary structure and calculate binding stability are essential for selecting gRNAs with optimal physical characteristics [40].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Efficient gRNA Design

| Parameter | Description | Optimal Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Uniqueness of the target sequence within the genome [40] | Unique match with no or minimal off-target sites |