High-Throughput Screening in Biofoundries: Accelerating Discovery from Design to Clinic

This article explores the integration of high-throughput screening (HTS) systems within modern biofoundries, automated facilities that are revolutionizing synthetic biology and drug discovery.

High-Throughput Screening in Biofoundries: Accelerating Discovery from Design to Clinic

Abstract

This article explores the integration of high-throughput screening (HTS) systems within modern biofoundries, automated facilities that are revolutionizing synthetic biology and drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle and the core components of HTS, including automation and microplate technologies. It delves into methodological applications across various fields, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges in assay validation and reagent stability, and provides a comparative analysis of validation techniques and technology platforms. The synthesis of these areas provides a comprehensive guide for leveraging biofoundry capabilities to streamline R&D and bring therapeutics to market faster.

The Engine of Discovery: Core Principles of Biofoundries and High-Throughput Screening

Defining the Modern Biofoundry and the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle

A modern biofoundry is an integrated, high-throughput facility that utilizes robotic automation, sophisticated data processing, and computational analytics to streamline and accelerate synthetic biology research and applications through the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) engineering cycle [1]. These facilities function as structured R&D systems where biological design, validated construction, functional assessment, and mathematical modeling are performed iteratively [2]. The core mission of a biofoundry is to transform synthetic biology from a traditionally artisanal, slow, and expensive process into a reproducible, scalable, and efficient engineering discipline capable of addressing global scientific and societal challenges [1].

The emergence of biofoundries represents a strategic response to the growing complexity of biological systems engineering and the booming global synthetic biology market, projected to grow from $12.33 billion in 2024 to $31.52 billion in 2029 [1]. By automating the DBTL cycle, biofoundries enable the rapid prototyping of biological systems, significantly accelerating the discovery pace and expanding the catalog of bio-based products that can be produced for a more sustainable bioeconomy [1]. In recognition of their importance, the Global Biofoundry Alliance (GBA) was officially established in 2019, with membership growing from 15 initial biofoundries to over 30 facilities across the world by 2025 [1].

The DBTL Cycle: Core Framework for Biofoundry Operations

The DBTL cycle forms the fundamental operational framework for all biofoundry activities, providing a systematic, iterative approach to biological engineering [1]. This cyclical process consists of four interconnected phases that feed into one another, enabling continuous refinement and optimization of biological designs.

Design Phase

The cycle begins with the Design phase, where researchers define objectives for desired biological functions and design genetic sequences, biological circuits, or bioengineering approaches using computer-aided design software [1]. This stage relies heavily on domain knowledge, expertise, and computational modeling tools. Available software includes Cameo for in silico design of metabolic engineering strategies, RetroPath 2.0 for retrosynthesis experiments, j5 DNA assembly design software for DNA manipulation, and Cello for genetic circuit design [1]. Increasingly, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are being integrated into the Design phase to enhance prediction precision and reduce the number of DBTL cycles needed to achieve desired outcomes [3]. Protein language models such as ESM and ProGen, along with structure-based tools like MutCompute and ProteinMPNN, enable zero-shot prediction of protein sequences with desired functions [3].

Build Phase

In the Build phase, automated and high-throughput construction of the biological components predefined in the Design phase takes place [1]. This involves DNA synthesis, assembly into plasmids or other vectors, and introduction into characterization systems such as bacterial chassis, eukaryotic cells, mammalian cells, plants, or cell-free systems [3]. Biofoundries leverage integrated robotic systems and liquid handling devices to execute these processes at scale, constructing hundreds of strains across multiple species within tight timelines [1]. The development of open-source tools like AssemblyTron, which integrates j5 DNA assembly design outputs with Opentrons liquid handling systems, exemplifies the trend toward affordable automation solutions in the Build phase [1].

Test Phase

The Test phase determines the efficacy of the Design and Build phases by experimentally measuring the performance of engineered biological constructs [1]. This stage typically employs High-Throughput Screening (HTS) methods, defined as "the use of automated equipment to rapidly test thousands to millions of samples for biological activity at the model organism, cellular, pathway, or molecular level" [4]. HTS utilizes robotics, data processing/control software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors to quickly conduct millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests [5]. Standard HTS formats include microtiter plates with 96-, 384-, 1536-, or even 3456-wells, with recent advances enabling screening of up to 100,000 compounds per day [4] [5]. Detection methods span absorbance, fluorescence intensity, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), time-resolved fluorescence, and luminescence, among others [6].

Learn Phase

In the Learn phase, researchers analyze data collected during testing and compare it to objectives established in the Design stage [1]. This analysis informs the next Design round, enabling iterative improvement through additional DBTL cycles until desired specifications are met [1]. The Learning phase increasingly incorporates machine learning approaches to detect patterns in high-dimensional spaces, enabling more efficient and scalable design in subsequent cycles [3]. As datasets grow in size and quality, the Learn phase becomes increasingly powerful, potentially enabling a paradigm shift toward LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) cycles where machine learning precedes and informs initial design choices [3].

To address interoperability challenges between biofoundries, researchers have proposed a flexible abstraction hierarchy that organizes biofoundry operations into four distinct levels, effectively streamlining the DBTL cycle [2]. This framework enables more modular, flexible, and automated experimental workflows while improving communication between researchers and systems.

Table 1: Abstraction Hierarchy for Biofoundry Operations

| Level | Name | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 0 | Project | Series of tasks to fulfill requirements of external users | "Greenhouse gas bioconversion enzyme discovery and engineering" [2] |

| Level 1 | Service/Capability | Functions that external users require or that the biofoundry can provide | Modular long-DNA assembly, AI-driven protein engineering [2] |

| Level 2 | Workflow | DBTL-based sequence of tasks needed to deliver the Service/Capability | DNA Oligomer Assembly, Liquid Media Cell Culture [2] |

| Level 3 | Unit Operations | Individual hardware or software tasks that perform Workflow requirements | Liquid Transfer, Protein Structure Generation [2] |

This hierarchical abstraction allows engineers or biologists working at higher levels to operate without needing to understand the lowest-level operations, promoting specialization and efficiency [2]. The framework defines 58 specific biofoundry workflows categorized by DBTL stage and 42 hardware and 37 software unit operations that can be combined sequentially to perform arbitrary biological tasks [2].

High-Throughput Screening Implementation in Biofoundries

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) serves as a critical component of the Test phase within biofoundries, enabling rapid evaluation of thousands to millions of samples [4]. In its most common form, HTS involves screening 103–106 small molecule compounds of known structure in parallel, though it can also be applied to chemical mixtures, natural product extracts, oligonucleotides, and antibodies [4].

HTS Assay Formats and Detection Methods

HTS assays are predominantly performed in microtiter plates with 96-, 384-, or 1536-well formats, with traditional HTS typically testing each compound at a single concentration (most commonly 10 μM) [4]. Two primary screening approaches dominate HTS:

- Biochemical Assays: Measure direct enzyme or receptor activity in a defined system, such as kinase activity assays to find small-molecule enzymatic modulators [6].

- Cell-Based Assays: Capture pathway or phenotypic effects in living cells, including proliferation assays, reporter gene assays, viability tests, and second messenger signaling [6].

Table 2: HTS Detection Methods and Applications

| Detection Method | Principle | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) | Measures molecular rotation and binding | Enzyme activity, receptor-ligand interactions | Homogeneous, no separation steps [6] |

| Time-Resolved FRET (TR-FRET) | Energy transfer between fluorophores | Protein-protein interactions, immunoassays | Reduced background, high sensitivity [6] |

| Luminescence | Light emission from chemical reactions | Reporter gene assays, cell viability | High sensitivity, broad dynamic range [5] |

| Absorbance | Light absorption at specific wavelengths | Enzyme activity, cell proliferation | Simple, cost-effective [5] |

| Fluorescence Intensity (FI) | Emission intensity upon excitation | Calcium flux, membrane potential | High throughput, various assay types [6] |

Quantitative HTS (qHTS) and Recent Advances

Quantitative high throughput screening (qHTS) represents an advanced HTS method that tests compounds at multiple concentrations using an HTS platform, generating concentration-response curves for each compound immediately after screening [4]. This approach has grown popular in toxicology because it more fully characterizes biological effects of chemicals and decreases false positive and false negative rates [4].

Recent innovations in HTS include:

- Drop-based microfluidics: Enables 100 million reactions in 10 hours at 1-millionth the cost using 10−7 times the reagent volume of conventional techniques [5].

- Silicon lens arrays: Allow fluorescence measurement of 64 different output channels simultaneously with a single camera, analyzing 200,000 drops per second [5].

- AI and virtual screening integration: Combined with experimental HTS to improve prediction accuracy and hit identification [6].

- 3D cultures and organoids: Provide more physiologically relevant models for predictive biology [6].

Experimental Protocols for Biofoundry Implementation

Protocol 1: Quantitative HTS for Compound Library Screening

This protocol outlines the procedure for quantitative high-throughput screening of compound libraries to identify hits with pharmacological activity, adapted from established HTS methodologies [4] [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound library (small molecules, natural products, or oligonucleotides)

- Assay plates (384-well or 1536-well format)

- Target biological system (enzymes, cells, or pathway reporters)

- Detection reagents (fluorogenic or chromogenic substrates)

- Liquid handling robotics and plate readers

Procedure:

- Assay Plate Preparation:

- Pipette nanoliter volumes from stock plates to corresponding wells of empty assay plates using liquid handling robots [5].

- Include positive and negative controls in designated wells for quality assessment.

Reaction Setup:

- Add biological entity (protein, cells, or embryos) to each well of the plate [5].

- Incubate plates to allow biological matter to absorb, bind, or react with compounds.

Measurement and Detection:

- Take measurements across all plate wells using automated plate readers.

- Apply appropriate detection method (FP, TR-FRET, luminescence) based on assay design [6].

Data Analysis:

Hit Confirmation:

- Perform follow-up assays by "cherrypicking" liquid from source wells with interesting results into new assay plates [5].

- Run secondary screens to confirm and refine observations.

Protocol 2: Cell-Free Protein Expression for DBTL Cycling

This protocol leverages cell-free expression systems to accelerate the Build and Test phases of the DBTL cycle, enabling rapid protein prototyping without time-intensive cloning steps [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell-free protein synthesis machinery (crude cell lysates or purified components)

- DNA templates for target proteins

- Reaction mixtures containing amino acids, nucleotides, and energy sources

- Microfluidic devices or liquid handling robots for high-throughput implementation

Procedure:

- DNA Template Preparation:

- Design DNA sequences encoding target proteins using computational tools (ProteinMPNN, ESM) [3].

- Synthesize DNA templates without intermediate cloning steps.

Cell-Free Reaction Assembly:

- Combine DNA templates with cell-free expression systems in microtiter plates or microfluidic devices.

- Scale reactions from picoliter to microliter volumes depending on throughput requirements.

Protein Expression:

- Incubate reactions at optimal temperature (typically 30-37°C) for 2-4 hours.

- Monitor protein expression kinetics if using real-time detection systems.

Functional Testing:

- Apply expressed proteins directly to coupled colorimetric or fluorescent-based assays.

- Perform high-throughput sequence-to-function mapping of protein variants.

Data Generation for Machine Learning:

- Compile expression levels and functional data for thousands of protein variants.

- Use datasets to train machine learning models for improved protein design in subsequent DBTL cycles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of biofoundry workflows requires specialized reagents and equipment designed for automation, reproducibility, and high-throughput applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biofoundry Operations

| Item | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | Miniaturized reaction vessels for parallel experimentation | 384-well plates for HTS; 1536-well for uHTS [4] [5] |

| Transcreener Assays | Universal biochemical assays for diverse target classes | Kinase, ATPase, GTPase, helicase activity screening [6] |

| CRISPR Libraries | Genetic perturbation tools for functional genomics | Gain/loss-of-function screens in primary cells [7] |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | In vitro transcription/translation machinery | Rapid protein prototyping without cloning [3] |

| Nucleofector Technology | High-throughput transfection system | 384-well format integration with liquid handling robots [7] |

| Liquid Handling Robots | Automated fluid transfer for reproducibility | Echo systems, Opentrons Flex for assay setup [8] |

Advanced Methodologies: Integrating AI and Cell-Free Systems

The frontier of biofoundry research involves the tight integration of artificial intelligence with experimental workflows, potentially reordering the traditional DBTL cycle. Recent proposals suggest an LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) paradigm, where machine learning precedes design based on available large datasets [3]. This approach leverages the predictive power of pre-trained protein language models capable of zero-shot prediction of diverse antibody sequences and beneficial mutations [3].

Cell-free systems play a crucial role in this evolving paradigm by enabling ultra-high-throughput testing of computational predictions. These systems allow protein biosynthesis without intermediate cloning steps, achieving production of >1 g/L protein in <4 hours and screening of upwards of 100,000 picoliter-scale reactions when combined with droplet microfluidics [3]. The integration of cell-free platforms with liquid handling robots and microfluidics provides the megascale data generation necessary to train increasingly accurate machine learning models, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement in biological design capabilities [3].

Case Study: DARPA Biofoundry Challenge

A prominent success story demonstrating biofoundry capabilities comes from a timed pressure test administered by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), where a biofoundry was challenged to research, design, and develop strains to produce 10 small molecules in 90 days [1]. The target molecules ranged from simple chemicals to complex natural metabolites with no known biological synthesis pathways, including:

- 1-Hexadecanol: Used as a fastener lubricant in armed forces

- Tetrahydrofuran: Versatile industrial solvent and polymer precursor

- Carvone: Monoterpene with applications as mosquito repellent and pesticide

- Barbamide: Potent molluscicide for antifouling agents in marine paints

- Anticancer agents: Vincristine, rebeccamycin, and enediyene C-1027

Within the stipulated timeframe, the biofoundry constructed 1.2 Mb DNA, built 215 strains spanning five species, established two cell-free systems, and performed 690 assays developed in-house for the molecules [1]. The team succeeded in producing the target molecule or a closely related one for six out of the 10 targets and made advances toward production of the others, demonstrating the power of integrated biofoundry approaches to address complex biological engineering challenges [1].

This case study illustrates how biofoundries can leverage the complete DBTL cycle to rapidly tackle diverse synthetic biology problems, combining computational design, automated construction, high-throughput testing, and data-driven learning to accelerate biological discovery and engineering.

What is High-Throughput Screening? Core Concepts and Workflows

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated methodology used in scientific discovery to rapidly conduct millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests [5]. This approach allows researchers to quickly identify active compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate specific biomolecular pathways, providing crucial starting points for drug design and understanding biological interactions [5]. In the context of biofoundries, HTS serves as a critical component within the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, enabling rapid prototyping and optimization of biological systems for applications ranging from biomanufacturing to therapeutic development [1].

The evolution of HTS has transformed drug discovery and biological research by leveraging robotics, data processing software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors to achieve unprecedented screening capabilities [5]. Whereas traditional methods might test dozens of samples manually, modern HTS systems can process over 100,000 compounds per day, with ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) pushing this capacity even further [5] [9]. This accelerated pace is particularly valuable in biofoundries, where the integration of automation, robotic liquid handling systems, and bioinformatics streamlines synthetic biology workflows [1].

Core Principles and Key Components

Fundamental Concepts

At its core, HTS is the use of automated equipment to rapidly test thousands to millions of samples for biological activity at the model organism, cellular, pathway, or molecular level [4]. The methodology relies on three key technical considerations: miniaturization to reduce assay reagent amounts, automation to save researcher time and prevent pipetting errors, and quick assay readouts to ensure rapid data generation [10]. HTS typically involves testing large compound libraries—often containing 103–106 small molecules of known structure—in parallel using simple, automation-compatible assay designs [4].

A screening facility typically maintains a library of stock plates whose contents are carefully catalogued [5]. These stock plates aren't used directly in experiments; instead, assay plates are created as needed by pipetting small amounts of liquid (often nanoliters) from stock plates to corresponding wells of empty plates [5]. The essential output of HTS is the identification of "hits"—compounds with a desired size of effects that become candidates for further investigation [5].

Essential Hardware Components

Successful implementation of HTS relies on integrated hardware systems that work in concert to automate the screening process:

Microtiter Plates: These are the key labware of HTS, featuring grids of small wells arranged in standardized formats. Common configurations include 96, 384, 1536, 3456, or 6144 wells, all multiples of the original 96-well format with 8×12 well spacing [5]. The choice of plate format depends on the required throughput and reagent availability.

Robotics and Automation Systems: Integrated robot systems transport assay microplates between stations for sample and reagent addition, mixing, incubation, and final readout [5]. Automated liquid handlers dispense nanoliter aliquots of samples, minimizing assay setup times while providing accurate and reproducible liquid dispensing [9]. These systems can prepare, incubate, and analyze many plates simultaneously [5].

Detection Instruments: Plate readers or detectors assess chemical reactions in each well using various technologies including fluorescence, luminescence, absorption, and other specialized parameters [10]. Advanced detection systems can measure dozens of plates in minutes, generating thousands of data points rapidly [5].

Key Technical Specifications

Table 1: HTS Technical Capabilities and Formats

| Parameter | Standard HTS | Ultra-HTS (uHTS) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | 10,000-100,000 compounds/day [9] | >100,000 compounds/day [5], up to 300,000+ [9] | Throughput depends on assay complexity and automation level |

| Standard Plate Formats | 96, 384, 1536-well [4] | 1536, 3456, 6144-well [5] | Higher density enables greater throughput |

| Assay Volumes | Microliter range | 1-2 μL [9], down to nanoliters [11] | Miniaturization reduces reagent costs |

| Automation Level | Robotic workstations with some manual steps | Fully integrated, continuous operation | uHTS requires more complex automation |

| Data Output | Thousands of data points daily | Millions of data points daily | Creates significant data analysis challenges |

HTS Workflow and Experimental Protocols

The HTS process follows a structured workflow that integrates multiple steps from initial preparation to data analysis. The following diagram illustrates the core HTS workflow:

Diagram 1: High-Throughput Screening Core Workflow

Protocol 1: Assay Development and Validation

Objective: Establish robust, reproducible, and sensitive assays appropriate for miniaturization and automation [9].

Methodology:

- Assay Design: Select appropriate biochemical or cell-based assay format based on target biology. Common approaches include fluorescence-based assays, luminescence, fluorescence polarization, and time-resolved fluorescence [12] [9].

- Miniaturization Assessment: Test assay performance in progressively smaller volumes from standard 96-well to 384-well or 1536-well formats to determine minimal viable volume without sacrificing data quality.

- Robustness Validation: Implement statistical quality control measures including Z'-factor calculation, which has become a widely accepted criterion for evaluation and validation of HTS assays [12]. The Z'-factor measures the assay signal dynamic range and data variation associated with sample measurements [5].

- Control Selection: Establish effective positive and negative controls. Include controls on every plate to monitor assay performance and identify systematic errors [5].

Quality Control Parameters:

- Calculate Z'-factor using the formula: Z' = 1 - (3σ₊ + 3σ₋)/|μ₊ - μ₋|, where σ₊ and σ₋ are standard deviations of positive and negative controls, and μ₊ and μ₋ are their means [5].

- Assays with Z' > 0.5 are considered excellent for HTS [5].

- Alternatively, use Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) for assessing data quality in HTS assays [5].

Protocol 2: Library and Assay Plate Preparation

Objective: Prepare standardized, automation-friendly sample libraries for screening.

Methodology:

- Compound Management: Retrieve compound libraries from storage systems. Modern compound management involves highly automated procedures including compound storage on miniaturized microwell plates with retrieval, nanoliter liquid dispensing, sample solubilization, transfer, and quality control [9].

- Plate Replication: Create assay plates from stock plates using automated liquid handlers. Transfer small amounts of liquid (measured in nanoliters) from wells of stock plates to corresponding wells of empty plates [5].

- Plate Layout Optimization: Design plate layouts to identify systematic errors (especially position-based effects like "edge effect" caused by evaporation from peripheral wells) and determine appropriate normalization procedures [5] [10].

- Reagent Dispensing: Use non-contact dispensers for reagent addition to minimize cross-contamination. Modern systems like the I.DOT Liquid Handler can dispense volumes as low as 4 nL with high precision [11].

Technical Considerations:

- For quantitative HTS (qHTS), prepare compound dilution series across multiple plates to test compounds at various concentrations [4].

- Include appropriate controls distributed across plates to monitor positional effects.

- Use barcoding systems for plate tracking and management [11].

Protocol 3: Screening and Detection

Objective: Execute automated screening and generate reliable readouts.

Methodology:

- Assay Assembly: Using automated systems, add biological entities (proteins, cells, or animal embryos) to each well of the prepared assay plates [5].

- Incubation: Allow appropriate incubation time for biological matter to absorb, bind to, or react with compounds in the wells. Automated systems maintain optimal environmental conditions throughout this process.

- Signal Detection: Measure responses across all plate wells using specialized detectors. Selection of detection technology depends on assay type:

- Fluorescence Intensity: Measures emission intensity after excitation

- Fluorescence Polarization: Measures molecular rotation by detecting emission plane changes

- Luminescence: Measures light emission from chemical reactions

- Absorbance: Measures light absorption at specific wavelengths [9]

- Data Capture: Instrument software outputs results as grids of numeric values, with each number mapping to a value obtained from a single well [5].

Automation Integration:

- Program robotic systems to transfer plates between pipetting stations, incubators, and detectors with minimal human intervention.

- High-capacity analysis machines can measure dozens of plates in minutes, generating massive experimental datasets quickly [5].

Protocol 4: Data Analysis and Hit Identification

Objective: Process screening data to identify legitimate "hits" for further investigation.

Methodology:

- Data Normalization: Apply normalization techniques to remove systematic errors and plate-based biases identified during assay development.

- Hit Selection: Apply statistical methods to identify compounds with significant activity:

- False Positive Triage: Implement approaches to identify and filter false positives resulting from assay interference, chemical reactivity, metal impurities, autofluorescence, or colloidal aggregation [9]. Use in silico methods such as pan-assay interferent substructure filters or machine learning models trained on historical HTS data [9].

- Hit Confirmation: Perform follow-up assays by "cherrypicking" liquid from source wells that gave interesting results into new assay plates, then re-running experiments to collect further data on this narrowed set [5].

Data Analysis Considerations:

- The process of selecting hits depends on whether the screen has replicates [5].

- For primary screens without replicates, use percent inhibition, percent activity, or z-score methods [5].

- In screens with replicates, SSMD directly assesses effect size and is comparable across experiments [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | Testing vessel for HTS assays | Available in 96-6144 well formats; choice depends on throughput needs and available reagent volumes [5] |

| Compound Libraries | Source of chemical diversity for screening | Can include small molecules, natural product extracts, oligonucleotides, antibodies; quality control is critical [4] |

| Detection Reagents | Generate measurable signals from biological activity | Include fluorescent probes, luminescent substrates, antibody conjugates; must be compatible with automation [9] |

| Cell Lines | Provide biological context for cellular assays | Engineered cell lines with reporter systems are common; require consistent culture conditions [4] |

| Enzymes/Protein Targets | Biological macromolecules for biochemical assays | Require validation of activity and stability under screening conditions [9] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintain optimal biochemical conditions | Must support biological activity while preventing interference with detection technologies [5] |

HTS in Biofoundries: Integration with the DBTL Cycle

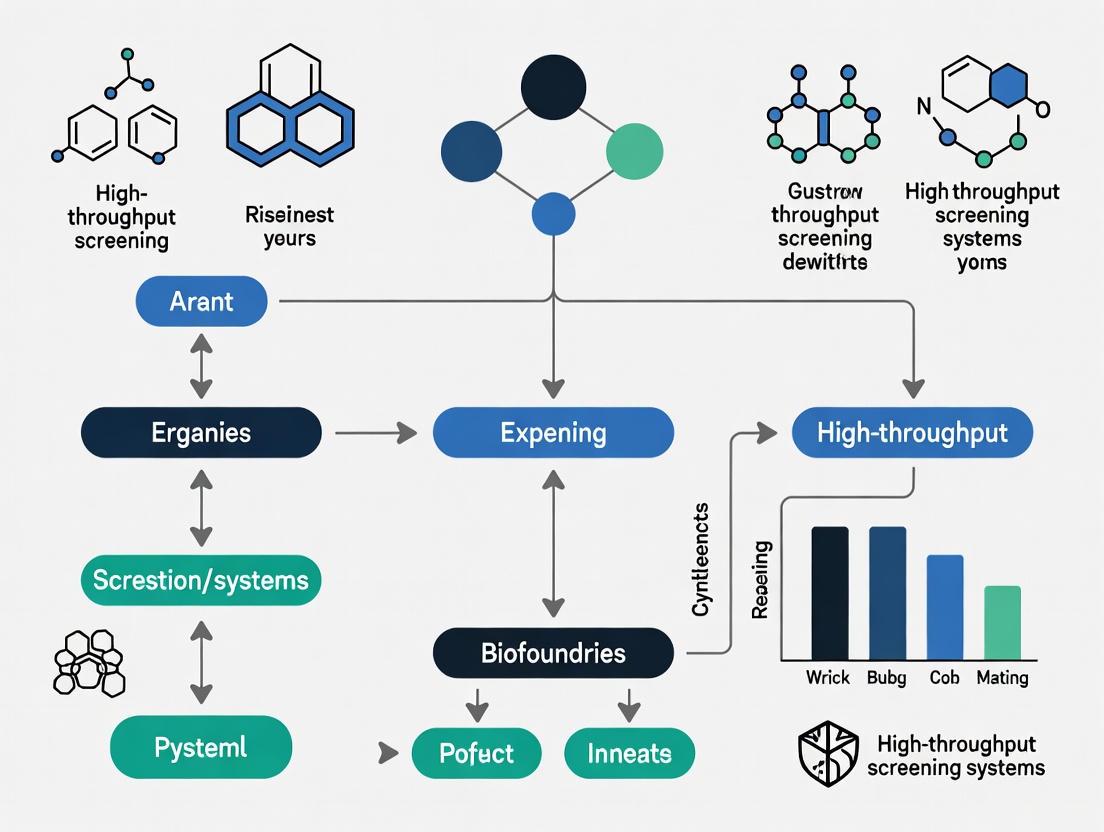

In biofoundries, HTS serves as a critical component of the Test phase within the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) engineering cycle [1]. The integration of HTS capabilities enables rapid iteration through multiple cycles of biological engineering, dramatically accelerating the development timeline. The following diagram illustrates how HTS integrates into the biofoundry DBTL cycle:

Diagram 2: HTS Integration in Biofoundry DBTL Cycle

The implementation of HTS within biofoundries has demonstrated remarkable success in accelerating biological engineering. For instance, Lesaffre's biofoundry reported increasing their screening capacity from 10,000 yeast strains per year to 20,000 per day, reducing genetic improvement projects from 5-10 years to just 6-12 months [13]. Similarly, in a challenge administered by DARPA, a biofoundry successfully researched, designed, and developed strains to produce 10 target molecules within 90 days, constructing 1.2 Mb DNA, building 215 strains across five species, establishing two cell-free systems, and performing 690 in-house developed assays [1].

Advanced HTS Methodologies

Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS)

Quantitative HTS represents an advancement over traditional HTS by testing compounds at multiple concentrations to generate full concentration-response relationships for each compound immediately after screening [5] [4]. This approach yields more comprehensive compound characterization including half maximal effective concentration (EC₅₀), maximal response, and Hill coefficient (nH) for entire libraries, enabling assessment of nascent structure-activity relationships (SAR) while decreasing rates of false positives and false negatives [5] [4].

High-Content Screening (HCS)

High-content screening combines HTS with cellular imaging and automated microscopy to collect multiple parameters from each well at single-cell resolution. This approach provides richer datasets than conventional HTS, capturing spatial and temporal information about compound effects while maintaining high-throughput capacity.

Emerging Technologies

Recent advances continue to push the boundaries of HTS capabilities:

- Microfluidics: Drop-based microfluidics has demonstrated the ability to perform 100 million reactions in 10 hours at one-millionth the cost of conventional techniques using 10⁻⁷ times the reagent volume [5].

- Advanced Detection: Silicon sheets of lenses placed over microfluidic arrays can simultaneously measure 64 different output channels with a single camera, analyzing up to 200,000 drops per second [5].

- AI Integration: Machine learning and artificial intelligence are increasingly being incorporated at each phase of the screening process to enhance prediction precision and reduce the number of DBTL cycles needed to attain desired results [1] [13].

High-Throughput Screening represents a foundational technology in modern biological research and drug discovery, providing an automated, systematic approach to testing thousands to millions of compounds for biological activity. The core workflow—encompassing assay development, library preparation, automated screening, and data analysis—enables rapid identification of hits that modulate targets of interest. When integrated into biofoundries within the DBTL cycle, HTS dramatically accelerates the pace of biological engineering, reducing development timelines from years to months while increasing screening capacity by orders of magnitude. As technologies continue to advance, particularly through microfluidics, improved detection systems, and AI integration, HTS capabilities will continue to expand, further enhancing its role as an indispensable tool for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the forefront of biological innovation.

In modern biofoundries, High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a fundamental paradigm shift from manual processing to automated, large-scale experimentation. This operational transformation is essential for contemporary drug discovery and systems biology research, where target validation and compound library exploration require massive parallel experimentation [14]. The core infrastructure enabling this shift consists of an integrated ecosystem of robotics, precision liquid handling systems, and advanced detection technologies. These systems work in concert to dramatically increase the number of samples processed per unit time while conserving expensive reagents and reducing reaction volumes through miniaturization [14]. The scientific principle guiding HTS infrastructure is the generation of robust, reproducible data sets under standardized conditions to accurately identify potential "hits" from extensive chemical or biological libraries [14] [9].

For biofoundries, which operate as automated facilities for genetic and metabolic engineering, this infrastructure is not merely convenient but essential. It provides the backbone for the design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycles that are central to synthetic biology and biomanufacturing research. The integration of sophisticated automation allows for continuous, 24/7 operation, dramatically improving the utilization rate of expensive analytical equipment and accelerating the pace of discovery [14]. This technical note details the essential components of this infrastructure, providing application-focused protocols and performance data to guide researchers in establishing and optimizing HTS capabilities within biofoundry environments.

Core Robotic Systems in HTS

Robotic Arms and Plate Handling Systems

At the heart of any HTS platform are the robotic systems that provide the precise, repetitive, and continuous movement required to realize fully automated workflows. These mechanical systems move microplates between functional modules like liquid handlers, plate readers, incubators, and washers without human intervention [14]. The primary types of laboratory robotics include Cartesian and articulated robotic arms, with the NCGC's screening system utilizing three high-precision Stäubli robotic arms for plate transport and delidding operations [15]. These systems enable complete walk-away automation, with the integration software or scheduler acting as the central orchestrator that manages the timing and sequencing of all actions [14].

A recent innovation in this space is the development of modular rotating hotel units, specifically engineered to support autonomous, flexible sample handling. These units feature up to four SBS-compatible plate nests with customizable configurations and built-in presence sensors, enabling mobile robots to transfer samples and labware seamlessly between HTS workstations automatically [16]. This technology is particularly impactful for integrating mobile robots with closed systems like high-throughput screening workstations, which are central to the Lab of the Future concept. By eliminating process interruptions and enabling 24/7 operation, these automated storage solutions significantly improve throughput and flexibility, which are essential features for next-generation biofoundries [16].

Automated Storage and Incubation Systems

Modern HTS systems require substantial capacity for storing compound libraries and assay plates during screening campaigns. The system at the NIH's Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC) provides a representative example, with a total capacity of 2,565 plates—1,458 positions dedicated to compound storage and 1,107 positions for assay plate storage [15]. Critically, every storage point on advanced systems is random access, allowing complete access to any individual plate at any given time [15]. For cell-based assays, proper incubation is essential, and advanced systems incorporate multiple individually controllable incubators capable of regulating temperature, humidity, and CO₂ levels [15]. The NCGC system, for instance, includes three 486-position plate incubators, allowing for a variety of assay types to be run simultaneously, as each incubator can be individually controlled [15].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Robotic HTS Components

| Component Type | Key Function | Technical Specifications | Throughput Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Articulated Robotic Arms | Plate transport between modules | High-precision, 6-axis movement (e.g., Stäubli) | Enables full walk-away automation |

| Rotating Hotel/Storage | Modular sample storage & transfer | Up to 4 SBS-compatible nests, presence sensors | Enables mobile robot integration; 24/7 operation |

| Random-Access Incubators | Environmental control for assays | Control of temp, humidity, CO₂; 486-position capacity | Allows multiple simultaneous assay types |

| Central Scheduler Software | Workflow orchestration | Manages timing/sequencing of all actions | Maximizes equipment utilization; prevents bottlenecks |

Liquid Handling Robotics

Liquid handling robots form the operational core of HTS infrastructure, executing the precise, sub-microliter dispensing routines that miniaturized assays demand. These systems comprise multiple independent pipetting heads that can execute precise, sub-microliter dispensing across an entire microplate within seconds [14]. This level of speed and accuracy is non-negotiable for success in HTS, as manual pipetting cannot reliably deliver the required precision across thousands of replicates [14]. The market for these systems is experiencing robust growth, driven by increasing automation across life science sectors, with major players including Flow Robotics, INTEGRA Biosciences, Opentrons, Agilent Technologies, and Corning Incorporated continually advancing the technology [17].

Liquid handling robots are characterized by their precision, accuracy, and miniaturization capabilities. Recent innovations have focused on increasing precision and accuracy through advances in robotics and software, improving the repeatability of liquid handling tasks [17]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is further revolutionizing the field, enabling these systems to optimize liquid handling protocols, predict maintenance needs, and adapt to unexpected events, significantly increasing efficiency and minimizing errors [17]. The ongoing miniaturization of liquid handling systems is making them more accessible to smaller laboratories and research groups, broadening market penetration and application in diverse research settings [17].

Application in Quantitative HTS (qHTS)

Liquid handling robotics enables advanced screening paradigms such as quantitative HTS (qHTS), which tests each library compound at multiple concentrations to construct concentration-response curves (CRCs) [15]. This approach generates a comprehensive data set for each assay and shifts the burden of reliable chemical activity identification from labor-intensive post-HTS confirmatory assays to automated primary HTS [15]. The practical implementation of qHTS for cell-based and biochemical assays across libraries of >100,000 compounds requires maximal efficiency and miniaturization, which is enabled by robotic liquid handling systems capable of working in 1,536-well plate formats [15].

At the NCGC, the implementation of a fully integrated and automated screening system for qHTS has led to the generation of over 6 million CRCs from >120 assays in a three-year period [15]. This achievement demonstrates how tailored automation can transform workflows, with the combination of advanced liquid handling and qHTS technology increasing the efficiency of screening and lead generation [15]. The system employs an innovative 1,536-pin array for rapid compound transfer and multifunctional reagent dispensers employing solenoid valve technology to achieve the required throughput and precision for these massive screening campaigns [15].

Table 2: Liquid Handling Robotic Systems and Applications

| System Type | Volume Range | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Workstations | Nanoliter to milliliter | Drug discovery, compound library screening | 96- to 1536-well compatibility; integrated pipetting heads |

| Pin Tool Transfer Systems | Nanoliter range | High-density compound reformatting | 1,536-pin arrays for simultaneous transfer |

| Modular Benchtop Systems | Microliter to milliliter | Smaller labs, specific workflow automation | Compact footprint; lower cost; user-friendly interfaces |

| Non-Contact Dispensers | Picoliter to microliter | Reagent addition, assay miniaturization | Solenoid valve technology; low cross-contamination |

Detection and Analysis Technologies

Detection Modalities for HTS Assays

HTS detection systems are critical for capturing the biological responses initiated by compound exposure or genetic perturbations. These systems primarily consist of microplate readers capable of measuring various signal types including fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance, and more specialized readouts like fluorescence polarization (FP) and time-resolved FRET (TR-FRET) [15] [18]. The choice of detection technology is heavily influenced by the assay format, with biochemical and cell-based assays often requiring different detection strategies [18]. Biochemical assays typically utilize enzymes, receptors, or purified proteins and employ detection methods that can quantify changes in enzymatic activity or binding events [9].

Cell-based assays present additional complexities, as they capture pathway or phenotypic effects in living cells [18]. These assays often employ reporter gene systems, viability indicators, or second messenger signaling readouts [18]. For luminescence-based cell reporter assays, researchers must choose between flash and glow luminescence formats, each with distinct advantages in cost, throughput, and automation compatibility [19]. The BMG Labtech blog notes that fluorescence-based detection methods remain the most common due to their "sensitivity, responsiveness, ease of use and adaptability to HTS formats" [20]. However, MS-based methods of unlabeled biomolecules are increasingly being utilized in HTS, permitting the screening of compounds in both biochemical and cellular settings [9].

Advanced Detection Applications

Emerging detection technologies are expanding the capabilities of HTS systems in biofoundries. High-content screening (HCS) combines automated imaging with multiparametric analysis, capturing complex phenotypic responses in cell-based systems [18]. These systems can perform object enumeration/scoring and multiparametric analysis, providing richer data sets from single screens [15]. Another significant advancement is the implementation of miniaturized, multiplexed sensor systems that allow continuous monitoring of multiple analytes or environmental conditions within individual microwells [9]. This technology addresses a previous limitation in uHTS where biosensors were often restricted to one analyte, constraining the ability to perform multiplex measurements in parallel [9].

For specialized applications, detection systems must be carefully selected to match assay requirements. The NCGC system employs multiple detectors including ViewLux, EnVision, and Acumen to address diverse assay needs across target types including profiling, biochemical, and cell-based assays [15]. This multi-detector approach allows the facility to maintain flexibility in assay development and implementation. As HTS evolves, next-generation detection chemistries are emerging that offer ultra-sensitive readouts, further pushing the boundaries of what can be detected in miniaturized formats [18].

Experimental Protocols for HTS Implementation

Protocol 1: Implementation of a Quantitative HTS (qHTS) Workflow

Principle: Quantitative HTS (qHTS) tests each compound at multiple concentrations to generate concentration-response curves (CRCs) for a more comprehensive assessment of compound activity [15]. This protocol outlines the steps for implementing a qHTS campaign for a biochemical enzyme assay, adapted from the approach used at the NCGC [15].

Materials:

- Compound library formatted as a concentration series

- Assay reagents (buffer, substrate, enzyme)

- 1,536-well assay plates

- Automated liquid handling system with 1,536-pin tool

- Multifunctional reagent dispensers

- Appropriate plate reader (e.g., ViewLux for luminescence/fluorescence)

Procedure:

- Plate Reformatting: Transfer compound concentration series from storage plates to 1,536-well assay plates using the 1,536-pin tool. The NCGC system can store over 2.2 million samples representing approximately 300,000 compounds prepared as a seven-point concentration series [15].

Reagent Dispensing: Add assay buffer and substrate to assay plates using solenoid valve-based dispensers. The system should maintain temperature control throughout dispensing operations.

Reaction Initiation: Initiate the enzymatic reaction by adding enzyme solution using the liquid handling system. The system at NCGC employs anthropomorphic arms for plate transport and multifunctional dispensers for reagent addition [15].

Incubation: Incubate plates for the appropriate time under controlled environmental conditions. The NCGC system uses three 486-position plate incubators capable of controlling temperature, humidity, and CO₂ [15].

Signal Detection: Read plates using an appropriate detector. For the NCGC system, this may include ViewLux, EnVision, or Acumen detectors depending on the assay type [15].

Data Processing: Automatically transfer data to the analysis pipeline for CRC generation and hit identification.

Technical Notes:

- System reliability is critical; the NCGC system achieves <5% downtime [15].

- The random-access plate storage enables flexible scheduling of different assay types.

- This approach has generated over 6 million CRCs from >120 assays at the NCGC [15].

Protocol 2: Cell-Based Reporter Assay in 384-Well Format

Principle: This protocol describes the implementation of a luminescence cell-based reporter assay, comparing flash and glow luminescence detection modes [19]. The protocol is designed for HTS automation while acknowledging that some cell-based assays may not be compatible with higher density formats beyond 384-well plates.

Materials:

- Cell line with appropriate reporter construct

- Compound library in 384-well format

- Cell culture medium and assay reagents

- Luminescence detection reagents (flash and glow)

- Automated liquid handling system

- Plate washer (if including wash steps)

- Luminescence plate reader

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells expressing the reporter construct into 384-well assay plates using automated liquid handling. Maintain consistency in cell number across wells.

Compound Addition: Transfer compounds from library plates to assay plates using liquid handling robotics. The Opentrons platform provides open-source protocols for automating this transfer [21].

Incubation: Incubate plates for the appropriate time under controlled conditions (typically 37°C, 5% CO₂).

Detection Reagent Addition: Add either flash or glow luminescence reagents using the liquid handling system:

- Flash Luminescence: Provides a strong, brief signal requiring immediate reading.

- Glow Luminescence: Offers a stable, prolonged signal allowing more flexible reading schedules.

Signal Detection: Read plates using a luminescence-compatible plate reader. The choice between flash and glow detection will influence the scheduling and throughput.

Data Analysis: Process data using appropriate software, calculating Z'-factor and other quality control metrics.

Technical Notes:

- The nature of the cellular response may necessitate remaining in 384-well plates rather than migrating to higher density formats [19].

- Pin tool transfer can dramatically affect throughput and is suitable for low-volume transfers [19].

- Assay robustness should be monitored using Z'-factor calculations, with values between 0.5-1.0 indicating an excellent assay [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HTS Implementation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in HTS Workflow | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Assays | Transcreener ADP² Assay | Universal biochemical assay for kinase, ATPase, GTPase targets | Flexible design for multiple targets; uses FP, FI, or TR-FRET [18] |

| Cell-Based Reporter Systems | Luciferase reporter constructs | Measure gene expression changes in response to compounds | Choice between flash vs. glow luminescence affects throughput [19] |

| Enzyme Targets | Histone deacetylase (HDAC) | Screening for enzyme inhibitors in biochemical assays | Fluorescence-based methods most common due to sensitivity [9] |

| Viability/Cytotoxicity Assays | Cell proliferation assays | Phenotypic screening for compound effects on cell growth | Used in both target-based and phenotypic screening [18] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrated HTS workflow for biofoundries, showing the three primary phases of library preparation, automated screening, and analysis with feedback loops for iterative optimization.

The infrastructure supporting High-Throughput Screening in biofoundries represents a sophisticated integration of robotics, precision liquid handling, and advanced detection technologies. As detailed in these application notes, successful implementation requires careful consideration of each component's specifications and how they interact within a complete workflow. The emergence of technologies like the rotating hotel system for enhanced sample management [16] and the continued advancement of AI-integrated liquid handlers [17] point toward an increasingly automated and efficient future for HTS in biofoundries. By following the protocols and specifications outlined herein, researchers can establish robust HTS infrastructure capable of supporting the massive parallel experimentation required for modern drug discovery and synthetic biology research.

The evolution of microplate technology from the 96-well to the 1536-well format represents a critical pathway in advancing high-throughput screening (HTS) systems for modern biofoundries. This progression enables researchers to address increasing demands for efficiency, scalability, and cost-effectiveness in synthetic biology and pharmaceutical development. The transition to higher density microplates allows scientific teams to achieve unprecedented throughput while minimizing reagent consumption and experimental variability, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery in biofoundry research environments. The implementation of these advanced microplate systems provides the foundational infrastructure necessary for large-scale biological engineering projects that characterize cutting-edge biofoundry operations [22] [23].

The historical context of microplate development reveals a consistent trend toward miniaturization and automation. The original 96-well microplate was invented in 1951 by Dr. Gyula Takátsy, who responded to an influenza epidemic in Hungary by developing a system that enabled more efficient batch blood testing through hand-machined plastic plates with 96 wells arranged in an 8x12 configuration [23] [24]. This innovation established the fundamental architecture that would persist through subsequent generations of microplate technology. The 384-well plate emerged as an intermediate step, followed by the 1536-well format in 1996, which marked a significant milestone in ultra-high-throughput screening capabilities [23]. This evolution has been paralleled by developments in liquid handling robotics, detection systems, and data management infrastructure that collectively support the implementation of these advanced platforms in biofoundry settings [22].

Technical Specifications and Comparative Analysis

The migration from conventional 96-well plates to higher density formats necessitates careful consideration of technical specifications and their implications for experimental design. The physical characteristics of each plate type directly influence their suitability for specific applications within the biofoundry workflow.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microplate Formats

| Parameter | 96-Well Plate | 384-Well Plate | 1536-Well Plate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Well Number | 96 | 384 | 1536 |

| Standard Well Volume | 100-400 µL | 10-100 µL | 1-10 µL |

| Common Applications | Basic screening, ELISA assays | Intermediate throughput screening | Ultra-high-throughput screening |

| Liquid Handling Requirements | Manual or automated | Typically automated | Requires specialized robotics |

| Typical Users | Academic labs, small facilities | Pharmaceutical companies, CROs | Large pharmaceutical companies, core facilities |

| Relative Reagent Cost per Test | 1x | ~0.3x | ~0.1x |

The 1536-well standard format microplate is typically manufactured from a single piece of polystyrene polymer, available in transparent, black, or white colors. These plates feature a rounded well design that promotes optimal uniform meniscus formation, which is critical for accurate liquid handling and measurements. The F-bottom shape enhances compatibility with automated systems, while surface options include non-treated and cell culture-treated variants to support different biological applications [25]. The extreme miniaturization of the 1536-well format (with working volumes typically ranging from 1-10 µL) reduces reagent costs by approximately 90% compared to 96-well plates, while increasing data point density by 16-fold [25] [22].

The implementation of 1536-well plates in biofoundries requires specialized supporting infrastructure. These plates are designed specifically for automation and necessitate the use of robotic liquid handling equipment. The high-density format demands precision instrumentation for consistent and accurate fluid transfer at microliter and sub-microliter volumes. Additionally, detection systems must be capable of reading the smaller well dimensions without compromising data quality. The transition to 1536-well plates is therefore not merely a change in consumables, but rather a system-wide upgrade that impacts multiple aspects of the screening workflow [25].

Applications in High-Throughput Screening Systems

The 1536-well microplate format has found particular utility in ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) applications that form the core of biofoundry operations. These applications span multiple domains of biological research and development, leveraging the miniaturized format to maximize testing efficiency.

Drug Discovery and Development

In pharmaceutical research, 1536-well plates enable rapid screening of extensive compound libraries against biological targets. This capability significantly accelerates the hit identification phase of drug discovery, allowing researchers to evaluate hundreds of thousands of compounds in timeframes that would be impractical with lower density formats. The miniaturization directly reduces compound requirements, which is particularly valuable when working with scarce or expensive chemicals. In secondary screening assays, 1536-well plates facilitate detailed dose-response studies with increased replication and statistical power while conserving valuable hit compounds identified in primary screens [25] [22].

Synthetic Biology and Biofoundry Applications

Biofoundries leverage 1536-well plates for massive parallel testing of genetic constructs, pathway variants, and engineered organisms. The high-density format supports the design-build-test-learn cycle central to synthetic biology by enabling comprehensive characterization of biological systems under multiple conditions. For example, researchers can simultaneously assess promoter strength, ribosome binding site variants, and gene orthologs across different growth conditions in a single experiment. This comprehensive data generation provides the foundational information needed for predictive biological design and rapid strain optimization [26].

Functional Genomics and Transcriptomics

High-throughput functional genomics approaches, including RNAi and CRISPR screening, benefit substantially from the 1536-well format. These experiments require testing numerous genetic perturbations across multiple cell lines and conditions, generating enormous experimental arrays that are ideally suited to high-density microplates. The miniaturized format makes genome-wide screens in human cell lines practically feasible and cost-effective by reducing reagent costs and handling time while increasing experimental throughput [23] [27].

Experimental Protocols for 1536-Well Applications

Protocol: Cell-Based Viability Screening in 1536-Well Format

Objective: To evaluate compound toxicity against cultured mammalian cells using a 1536-well microplate format.

Materials:

- 1536-well cell culture-treated microplates (e.g., polystyrene, transparent) [25]

- Mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293, HepG2)

- Cell culture medium appropriate for cell line

- Compound library for screening

- Viability assay reagent (e.g., resazurin, CellTiter-Glo)

- Automated liquid handling system capable of 1536-well format

- Centrifuge with 1536-well plate adapters

- Microplate reader compatible with 1536-well format

Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Using an automated liquid handler, dispense 2 µL of cell culture medium into each well of the 1536-well plate [27].

- Compound Transfer: Transfer 10 nL of compound solutions from source plates to corresponding wells of assay plates using a pintool or acoustic liquid handler.

- Cell Seeding: Prepare cell suspension at optimized density (typically 1-5×10^4 cells/mL) and dispense 3 µL into each well using an automated dispenser.

- Incubation: Place plates in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 48-72 hours.

- Viability Assessment: Add 1 µL of viability assay reagent to each well using an automated dispenser.

- Signal Development: Incubate plates according to assay reagent specifications (typically 30-120 minutes).

- Detection: Measure fluorescence or luminescence using a compatible microplate reader.

- Data Analysis: Normalize data to positive (100% inhibition) and negative (0% inhibition) controls.

Critical Considerations:

- Maintain strict sterility throughout the procedure when working with live cells.

- Optimize cell density and compound incubation time for each cell line.

- Include appropriate controls (media-only, vehicle-only, maximal effect) on each plate.

- Ensure uniform dispensing through regular calibration of liquid handling equipment.

Protocol: Microwave-Assisted Sample Preparation in 96-Well Format

Objective: To implement rapid, high-throughput sample preparation for biomolecule fragmentation and extraction using a modified microplate platform.

Materials:

- 96-well microplates (polystyrene) [28]

- Aluminum foil for passive scattering elements (PSEs)

- Microwave oven (2.45 GHz frequency)

- Thermal imaging camera (FLIR)

- Biomaterial samples (bacterial cells, tissues)

- Lysis buffers

Procedure:

- Microplate Modification: Fabricate PSE arrays by cutting aluminum foil elements and adhering them to the bottom of polystyrene microplates.

- Sample Loading: Dispense 200 µL of sample material into each well of the modified microplate.

- Microwave Irradiation: Irradiate the loaded microplate in a microwave cavity at controlled power levels (270-900 W) for 30-90 seconds.

- Thermal Monitoring: Capture thermal images immediately post-irradiation using a FLIR camera.

- Temperature Analysis: Quantify heating effects using thermal analysis software.

- Sample Processing: Proceed with nucleic acid or protein extraction from processed samples.

Applications: This protocol enables rapid sample preparation for various pathogens including E. coli and Listeria monocytogenes, reducing processing time from hours to minutes while maintaining biomolecule integrity [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of high-throughput screening in biofoundries requires access to specialized reagents and equipment optimized for 1536-well formats. The following table details essential components of the ultra-high-throughput screening workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for 1536-Well HTS

| Category | Specific Product/Instrument | Function in HTS Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Microplates | 1536-well polystyrene plates (clear, black, white) | Foundation for assays; color selection optimizes signal detection for different readouts [25] |

| Liquid Handling | Automated dispensers/robotics with 1536-well capability | Accurate transfer of microliter volumes; essential for assay miniaturization [25] |

| Detection Systems | Multi-mode microplate readers (absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence) | Quantification of biochemical and cellular reactions in high-density formats [22] [29] |

| Cell Culture Tools | Cell culture-treated 1536-well plates with rounded well bottom | Promotion of uniform cell growth and meniscus formation for consistent results [25] [27] |

| Specialized Reagents | Homogeneous assay kits with "add-and-read" functionality | Elimination of wash steps; compatibility with automation [27] |

| Automation Integration | Robotic plate handlers and hotel systems | Seamless movement of plates between instruments; workflow integration [22] |

The selection of appropriate microplates represents a critical decision point in assay design. Black plates with clear bottoms are preferred for fluorescence-based assays, while white plates enhance luminescence signals. Cell culture-treated surfaces are essential for adherent cell types, while non-treated surfaces may suffice for suspension cultures. The rounded well design found in quality 1536-well plates promotes uniform meniscus formation, which is essential for consistent liquid handling and detection [25].

Advanced detection systems represent another cornerstone of successful 1536-well implementation. Multi-mode readers capable of absorbance, fluorescence, and luminescence detection provide flexibility across diverse assay platforms. Recent innovations incorporate artificial intelligence for real-time data interpretation and anomaly detection, while improved optics maintain detection sensitivity despite reduced path lengths in miniaturized wells. These systems increasingly feature wireless connectivity and cloud-based data management, supporting the collaborative nature of biofoundry research [22] [29].

Market Outlook and Future Perspectives

The microplate systems market demonstrates robust growth, valued at USD 4.73 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 8.04 billion by 2035, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.95% [22]. This expansion reflects the increasing adoption of high-throughput technologies across life sciences research. Microplate readers specifically show even stronger growth trends, with the market expected to increase from USD 453.32 million in 2025 to USD 821.43 million by 2032, representing a CAGR of 8.71% [29].

Several key trends are shaping the future evolution of microplate technologies and their applications in biofoundries:

Automation and Artificial Intelligence: Integration of AI-powered analytics enables real-time data interpretation and anomaly detection during screening campaigns. Automated systems increasingly incorporate machine learning algorithms to optimize assay conditions and identify subtle patterns in complex datasets [22].

Miniaturization Advancements: The progression beyond 1536-well plates to 9600-well nanoplates continues, though widespread adoption awaits developments in supporting instrumentation capable of handling picoliter volumes with sufficient precision and reproducibility [23].

Sustainable Laboratory Practices: Manufacturers are increasingly focusing on developing energy-efficient instruments with reduced plastic waste and enhanced recyclability. Multi-use and biodegradable microplates are emerging as environmentally conscious alternatives to traditional consumables [22].

Integration with Microfluidic Technologies: Microfluidic cell culture systems and organ-on-a-chip platforms are being adapted to higher throughput formats, enabling more physiologically relevant screening models with reduced reagent requirements [27].

Modular and Upgradeable Instrumentation: Instrument manufacturers are developing platforms that support plugin modules or software-enabled feature expansions, allowing biofoundries to adapt to emerging assay formats without complete system replacement [29].

The future of microplate technology in biofoundries will likely focus on increasing connectivity and data integration, creating seamless workflows from assay execution to data analysis and decision-making. These advancements will further solidify the role of ultra-high-throughput microplate systems as essential tools in the synthetic biology infrastructure, enabling the rapid design and testing of biological systems at an unprecedented scale.

The global high-throughput screening (HTS) market is experiencing substantial growth, driven by its critical role in accelerating drug discovery and biomedical research. This expansion is quantified by several recent market analyses, with projections indicating a consistent upward trajectory through the next decade.

Table 1: Global High-Throughput Screening Market Size and Growth Projections

| Metric | 2023/2024 Value | 2025 Value | 2032/2033 Value | CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) | Source Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size (Projection 1) | - | USD 26.12 Billion | USD 53.21 Billion | 10.7% (2025-2032) | 2025 [30] |

| Market Size (Projection 2) | USD 24.6 Billion | - | USD 62.8 Billion | 9.8% (2024-2033) | 2024 [31] |

| High Content Screening (HCS) Segment | USD 1.52 Billion (2024) | USD 1.63 Billion | USD 3.12 Billion (2034) | 7.54% (2025-2034) | 2025 [32] |

This growth is primarily fueled by the escalating demand for novel therapeutics for chronic diseases, the expansion of the biopharmaceutical industry, and significant technological advancements that enhance screening efficiency and data analysis [31].

Key Economic Drivers and Market Segments

The adoption and economic expansion of HTS are underpinned by several key drivers, which also define the dominant segments within the market.

Table 2: Key Market Drivers and Segment Analysis

| Driver Category | Specific Example/Impact |

|---|---|

| Drug Discovery Demand | Drug discovery is the leading application segment, expected to capture 45.6% of the market share in 2025. The need for rapid, cost-effective identification of therapeutic candidates is a primary catalyst [30] [31]. |

| Technological Advancements | Integration of AI and Machine Learning for data analysis and predictive analytics is reshaping the market, enhancing efficiency, and reducing costs [30] [31]. |

| Automation & Instrumentation | The instruments segment (liquid handling systems, detectors) is projected to hold a 49.3% market share in 2025, driven by steady improvements in speed, precision, and miniaturization [30]. |

| Shift to Physiologically Relevant Models | The cell-based assays segment is projected to account for 33.4% of the market share in 2025, underscoring a growing focus on models that better replicate complex biological systems [30]. |

| Regulatory and Policy Shifts | Initiatives like the U.S. FDA's roadmap to reduce animal testing (April 2025) encourage New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), thereby increasing demand for advanced HTS using human-relevant cell models [30]. |

Regional Adoption Trends

The adoption of HTS technologies varies significantly across the globe, influenced by regional infrastructure, investment, and industrial focus.

Table 3: Regional Market Share and Growth Trends (2025)

| Region | Projected Market Share (2025) | Key Characteristics and Growth Factors |

|---|---|---|

| North America | 39.3% [30] | Dominates the market due to a strong biotechnology and pharmaceutical ecosystem, advanced research infrastructure, sustained government funding, and the presence of major industry players [30] [31]. |

| Asia-Pacific | 24.5% (Fastest-growing) [30] | Growth is fueled by expanding pharmaceutical industries, increasing R&D investments, rising government initiatives to boost biotechnological research, and the growing presence of international HTS technology vendors [30] [31]. |

| Europe | Significant market share | Held by established pharmaceutical and research institutions, with detailed country-specific analyses available in broader market reports [31]. |

HTS in Biofoundries: The DBTL Workflow

Within modern biofoundries, HTS is an integral component of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, which streamlines and accelerates synthetic biology research [1] [2]. Biofoundries are automated facilities that integrate robotics, liquid handling systems, and bioinformatics to engineer biological systems [1]. The DBTL cycle provides a structured framework for this engineering process.

Figure 1: The DBTL Cycle in Biofoundries. High-Throughput Screening is central to the "Test" phase, where constructed biological constructs are characterized on a large scale [1] [2].

Experimental Protocol: A Genetic-Chemical Perturbagen Screen

This protocol details a complex HTS experiment that combines genetic perturbations (e.g., CRISPR) with chemical compound treatments, analyzed using a tool like HTSplotter for end-to-end data processing [33].

Figure 2: Genetic-Chemical Screen Workflow. This integrated protocol assesses the combined effect of genetic and chemical perturbations on cellular phenotypes [33].

Detailed Methodology

Phase 1: Assay Preparation and Treatment

- Cell Seeding: Using an automated liquid handler (e.g., Beckman Coulter, PerkinElmer), seed cells into 384-well assay plates at a density optimized for logarithmic growth. Maintain consistency across plates to minimize variability [30] [33].

- Genetic Perturbation: Introduce the genetic perturbagen (e.g., a CRISPR sgRNA library) to the cells. For CRISPR screens, this typically involves lentiviral transduction followed by antibiotic selection to generate a stable gene-knockdown or knockout population [33].

- Compound Treatment: Using a non-contact liquid dispenser (e.g., SPT Labtech's firefly), treat cells with a library of small-molecule compounds across a specified concentration range (e.g., 0.1 nM to 10 µM). Include controls on every plate:

- Negative Control: Cells with DMSO vehicle only.

- Positive Control: Cells with a cytotoxic compound for normalization.

- Incubation and Readout: Incubate plates for the desired duration (e.g., 72 hours). For real-time assays, use a live-cell imager (e.g., Incucyte) to monitor proliferation. For endpoint assays, measure cell viability using a fluorescence or luminescence-based method (e.g., ATP-content assay) on a plate reader [33].

Phase 2: Data Processing and Analysis with HTSplotter

HTSplotter is a specialized tool that automates the analysis of complex HTS data, including genetic-chemical screens and real-time assays [33].

Data Input and Structuring:

- Prepare input files containing raw measurement data (e.g., fluorescence units, cell counts), compound identifiers, concentrations, and genetic perturbagen identifiers.

- The software automatically identifies experiment types and control wells based on a conditional statement algorithm [33].

Data Normalization:

- Normalize raw data to plate-based controls using the formula:

Normalized Viability = (Sample - Positive Control) / (Negative Control - Positive Control) - For real-time assays, HTSplotter can calculate the Growth Rate (GR) value, a robust metric that compares growth rates in the presence and absence of perturbations, making it less sensitive to variability in division rates [33].

GR = 2^(log2(Sample_t / Sample_{t-1}) / log2(NegCtrl_t / NegCtrl_{t-1})) - 1

- Normalize raw data to plate-based controls using the formula:

Dose-Response Curve Fitting:

- For each genetic-chemical perturbation combination, HTSplotter fits a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model to the dose-response data using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm for nonlinear least squares [33].

- The model determines key parameters:

- Absolute IC~50~/GR~50~: The concentration that provokes a 50% reduction in viability or growth rate.

- E~max~ / GR~max~: The maximal effect at the highest dose tested.

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Calculated using the trapezoidal rule, providing an integrated measure of compound effect [33].

Synergy Analysis (for combinations):

- HTSplotter assesses the degree of interaction between the genetic perturbagen and the chemical compound using multiple models:

- Bliss Independence (BI): Compares the observed combination effect to the expected effect if the two perturbations were independent [33].

- Zero Interaction Potency (ZIP): Assumes two non-interacting drugs incur minimal changes in their dose-response curves upon combination [33].

- Highest Single Agent (HSA): Compares the combination effect to the highest inhibition effect of a single agent alone [33].

- HTSplotter assesses the degree of interaction between the genetic perturbagen and the chemical compound using multiple models:

Visualization and Output:

- The tool automatically generates publication-ready plots, including dose-response curves over time, GR plots, and synergy score matrices, exported as PDF files [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for HTS Workflows

| Item | Function in HTS | Specific Example/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handling Systems | Automated dispensing and mixing of small, precise volumes of samples and reagents. Crucial for assay setup in 96-, 384-, or 1536-well plates. | Beckman Coulter's Cydem VT System; SPT Labtech's firefly platform; BD COR PX/GX System [30]. |

| Cell-Based Assay Kits | Pre-optimized reagents for measuring specific cellular responses, such as viability, apoptosis, or receptor activation. | INDIGO Biosciences' Melanocortin Receptor Reporter Assay family for studying receptor biology [30]. |

| CRISPR Library | A pooled collection of guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting genes across the genome for large-scale genetic screens. | Used in the CIBER platform (CRISPR-based HTS system) to label extracellular vesicles with RNA barcodes for studying cell communication [30]. |

| 3D Cell Culture Matrices | Scaffolds or hydrogels that support the growth of cells in three dimensions, providing more physiologically relevant models for screening. | Used in 3D cell culture-based HCS for more accurate prediction of drug efficacy and toxicity [32]. |

| Detection Reagents | Fluorogenic, chromogenic, or luminescent probes that generate a measurable signal upon biological activity (e.g., enzyme activity, cell death). | Promega Corporation's bioluminescent assays for cytokine detection; reagents for Fluorometric Imaging Plate Reader (FLIPR) assays [31] [34]. |

From Theory to Therapy: HTS Workflows and Real-World Applications in Biofoundries