Genome Mining for Natural Products: A Data-Driven Blueprint for Novel Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging genome mining for natural product discovery.

Genome Mining for Natural Products: A Data-Driven Blueprint for Novel Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging genome mining for natural product discovery. It explores the foundational shift from traditional bioactivity-guided isolation to targeted, gene-based strategies for uncovering bioactive compounds. The content details advanced methodological frameworks, including orthogonal mining and multi-omics integration, alongside practical solutions for overcoming challenges in cluster activation and heterologous expression. Finally, it examines rigorous validation techniques and comparative genomic approaches that confirm novel discoveries and assess their potential to yield new therapeutics against pressing threats like antimicrobial resistance.

The Genomic Revolution: From Bioactivity-Guided Isolation to Targeted Genome Mining

The field of natural product discovery is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from traditional activity-guided screening to a genome-first approach. This paradigm shift was catalyzed by a critical revelation from early microbial genome sequences: that the genetic potential for natural product biosynthesis far exceeds the small molecules detected under standard laboratory conditions [1] [2]. For decades, natural product discovery relied on bioassay-guided fractionation of microbial extracts, an approach that yielded many clinically valuable compounds but suffered from high rediscovery rates and diminishing returns [1] [3]. The observation that sequenced bacteria encoded numerous biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) with no known metabolic products revealed an untapped reservoir of chemical diversity [4] [5]. This discovery spawned the field of genome mining, which takes a bioinformatics-driven approach to identify, prioritize, and characterize the products of BGCs [1].

This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and tools enabling this transition to a genome-first framework. We explore how integrated computational and experimental workflows are revitalizing natural product discovery by systematically connecting genetic potential to chemical structures, thereby unlocking bioactive molecules that previously evaded detection.

The Limitations of Traditional Approaches and the Genomic Imperative

The Traditional Discovery Pipeline

Classical natural product discovery followed a standardized workflow: (1) cultivation of microbial strains from environmental samples, (2) extraction of metabolites from fermentation broths, (3) bioactivity screening against therapeutic targets, and (4) bioassay-guided fractionation to isolate active compounds [2]. While this approach successfully identified many clinically important drugs, including approximately half of all approved anti-infectives and anticancer agents [1] [3], it presented several fundamental limitations:

- High Rediscovery Rates: Frequently re-isolating known compounds made the process increasingly inefficient [1] [2]

- Bias Toward Expressed Molecules: Only BGCs expressed under laboratory conditions were detectable, missing silent genetic potential [1]

- Limited Structural Insight: Bioactivity screening provided no prior information about chemical structure or biosynthetic origin [4]

The Genomic Revelation

The sequencing of the first Streptomyces genomes in the early 2000s revealed a striking discrepancy: these organisms encoded 20-30 secondary metabolite BGCs while typically producing only a handful of detectable compounds under standard fermentation conditions [4] [5]. This observation demonstrated that the metabolic capabilities of microbial producers had been severely underestimated and that traditional approaches accessed only a fraction of their biosynthetic potential [2]. This revelation established the imperative for a genome-first approach—one that begins with genomic data to guide downstream experimental efforts.

Core Principles of the Genome-First Paradigm

Foundational Concepts

The genome-first approach is built upon several key biological insights and technological capabilities:

- Biosynthetic Gene Clustering: Genes encoding specialized metabolic pathways are typically clustered in microbial genomes, facilitating their identification and analysis [4]

- Biosynthetic Logic: Enhanced understanding of the enzymatic logic of assembly-line systems like nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) and polyketide synthases (PKS) enables structural prediction from gene sequences [1] [6]

- Sequence-Structure Relationships: Conserved domain sequences can predict substrate specificity and structural features [7] [6]

Clarifying the Lexicon

As the field matured, precise terminology has evolved to describe different classes of uncharacterized BGCs [1]:

- Orphan BGCs: Gene clusters that cannot be linked to their metabolic products (or vice versa)

- Silent BGCs: Clusters that show little to no transcriptional activity under standard laboratory conditions

- Cryptic BGCs: A more general term sometimes used interchangeably with both of the above

Importantly, transcriptional silencing represents only one reason why BGCs may remain orphaned; challenges can also occur at the levels of translation, functional protein assembly, small molecule detection, or structure elucidation [1].

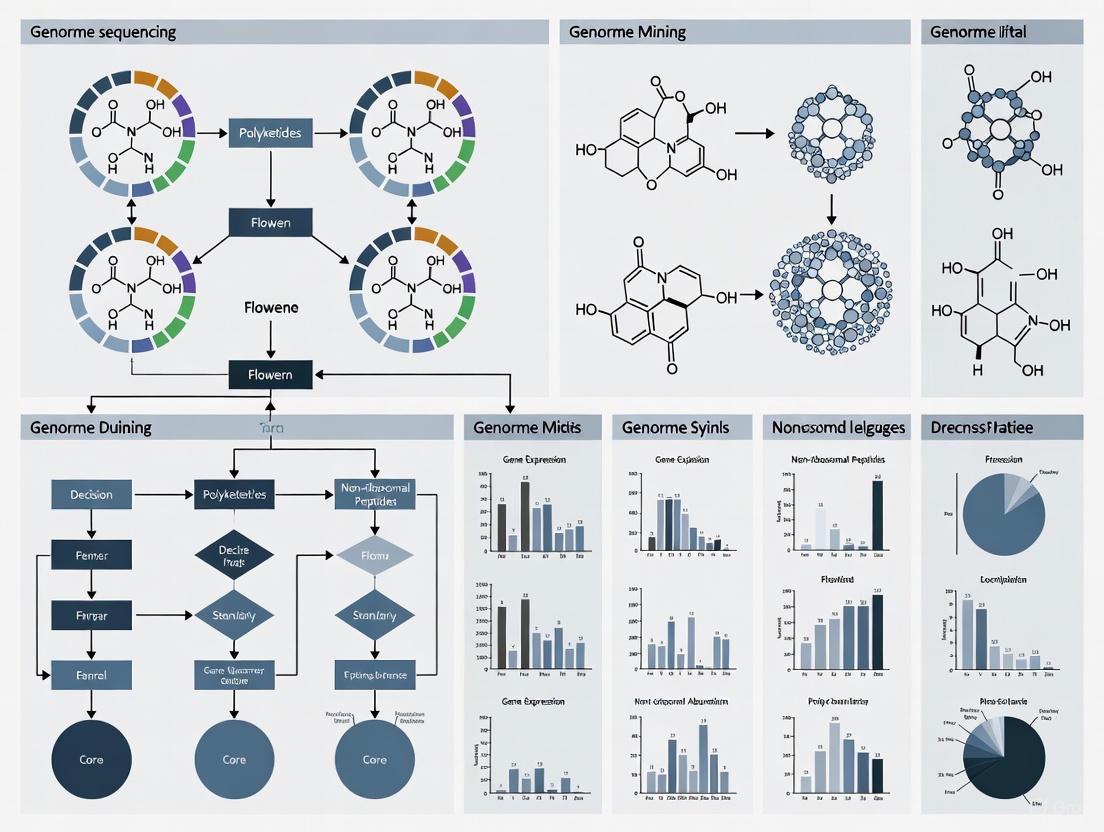

The Genomic Discovery Workflow: From Sequence to Compound

Integrated Computational-Experimental Pipeline

The genome-first approach follows a systematic workflow that integrates bioinformatic predictions with experimental validation:

Critical Tools and Databases

The genome mining workflow relies on specialized computational tools and databases for BGC identification and analysis:

Table 1: Essential Bioinformatics Tools for Genome Mining

| Tool/Database | Primary Function | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | BGC identification & annotation | Comprehensive analysis of secondary metabolite BGCs | [1] [7] [4] |

| PRISM | Natural product structure prediction | Prediction of NRPS/PKS-derived structures | [1] [4] |

| MIBiG | Repository of known BGCs | BGC dereplication and comparative analysis | [1] [4] |

| GNPS | Tandem MS networking | Metabolomic profiling & dereplication | [4] [3] |

| GNP | Automated genomes-to-natural products platform | LC-MS/MS data analysis with genomic predictions | [6] |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

BGC Activation Strategies

Many orphan BGCs remain transcriptionally silent under standard laboratory conditions, requiring specialized activation strategies:

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for BGC Activation and Product Identification

| Method | Protocol Summary | Applications | Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Expression | Clone entire BGC into amenable host (e.g., S. coelicolor, E. coli) | BGCs from unculturable or genetically-intractable organisms | Requires cluster cloning and host compatibility | [8] [2] |

| Promoter Engineering | Replace native promoters with constitutive or inducible variants | Targeted activation of specific silent BGCs | Depends on genetic tractability of host organism | [1] [8] |

| Cocultivation | Cultivate producer strain with other microorganisms | Simulate ecological interactions that trigger BGC expression | Empirical approach with unpredictable outcomes | [2] |

| Omic-Guided Induction | Use transcriptomic/proteomic data to identify growth conditions that activate BGCs | Data-driven cultivation optimization | Requires multi-omic infrastructure and expertise | [1] |

Integrated Genomic-Metabolomic Workflows

Modern discovery platforms integrate genomic predictions with metabolomic data to efficiently identify cluster products. The Genomes-to-Natural Products (GNP) platform exemplifies this approach [6]:

- Genome Analysis: Identify NRPS/PKS BGCs and predict substrate specificities of adenylation and ketosynthase domains

- Structure Prediction: Generate predicted chemical scaffolds based on colinearity rules and domain specificities

- Library Generation: Combinatorialize predictions to account for biosynthetic promiscuity or prediction inaccuracies

- In Silico Fragmentation: Calculate predicted MS/MS fragmentation patterns for all library compounds

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Acquire high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry data from microbial extracts

- Spectral Matching: Compare experimental MS/MS data with predicted fragmentation patterns to identify candidate molecules

This workflow successfully identified the nonribosomal peptides WS9326A and WS9326C from Streptomyces calvus and the novel metallophores acidobactin and variobactin from proteobacterial species [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of genome-first discovery requires specialized experimental and computational resources:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Genome-First Discovery

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Technical Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | PacBio, Oxford Nanopore | Long-read sequencing for complete BGC assembly | Essential for repetitive NRPS/PKS genes | [5] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | antiSMASH, PRISM, MIBiG | BGC identification and analysis | Require specialized computational expertise | [1] [7] [4] |

| Heterologous Hosts | S. coelicolor, E. coli | Expression of silent BGCs | Host compatibility with biosynthetic machinery | [8] [2] |

| Analytical Platforms | LC-HRMS/MS, NMR | Metabolite detection and structure elucidation | High sensitivity required for low-abundance metabolites | [6] [3] |

| Genetic Manipulation | CRISPR-Cas, BAC cloning | BGC engineering and refactoring | Dependent on host genetic tractability | [8] |

Case Studies: Genome-First Discovery in Action

Automated Metallophore Discovery

Recent work demonstrates how automated genome mining can predict and identify specialized metabolites across bacterial taxa. Researchers developed a comprehensive algorithm within antiSMASH to detect nonribosomal peptide metallophore BGCs by identifying genes encoding specific chelator biosynthesis pathways [7]. This approach achieved 97% precision and 78% recall against manual curation when applied to 69,929 bacterial genomes, predicting that approximately 25% of all bacterial NRPS encode metallophore production [7]. The study experimentally characterized novel metallophores from several taxa, validating predictions and revealing significant undiscovered chemical diversity.

Streptomyces Genome Mining

A guide to genome mining in Streptomyces outlines a systematic protocol for identifying and characterizing secondary metabolite BGCs in this prolific genus [8]. The workflow employs antiSMASH for BGC identification, followed by genetic manipulation techniques to activate cryptic clusters, including promoter engineering, regulatory gene overexpression, and heterologous expression. This approach demonstrates how genome-first strategies enable targeted discovery of valuable natural products from well-studied organisms that still harbor extensive uncharacterized biosynthetic potential.

Visualizing BGC Characterization Pathways

The process of connecting BGCs to their metabolic products requires multiple experimental strategies depending on cluster characteristics and host organism:

Quantitative Insights: Measuring the Paradigm Shift

The impact of the genome-first approach is evident in quantitative assessments of biosynthetic potential and discovery outcomes:

Table 4: Quantitative Assessment of Genomic Potential versus Traditional Discovery

| Metric | Traditional Approach | Genome-First Approach | Implications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGCs per Genome | 1-5 detectable metabolites | 20-30 BGCs in typical actinomycete | 5-10 fold increase in potential | [4] [5] |

| Characterized BGCs | ~1,400 in MIBiG repository | >25,000 orphan NRPS/PKS clusters | Vast majority remain uncharacterized | [1] [6] |

| NRPS Dedicated to Metallophores | Unknown | ~25% of all bacterial NRPS | Reveals specialized ecological functions | [7] |

| Draft Genome Limitations | Not applicable | ~60% of important NPs from NRPS/PKS | Highlights need for finished genomes | [5] |

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The transition to a genome-first paradigm represents a fundamental shift in natural product discovery, moving from random screening to targeted, hypothesis-driven approaches. This transformation has been enabled by converging technological developments in DNA sequencing, bioinformatics, and metabolomics [4] [3]. Current challenges include improving BGC assembly in draft genomes, particularly for large repetitive NRPS and PKS genes [5], developing more accurate structure prediction algorithms, and expanding genetic manipulation tools for non-model organisms [8].

As the field advances, several emerging trends will shape the next generation of genome mining: the integration of machine learning for improved structure prediction, the application of single-cell genomics to access unculturable diversity, and the development of more sophisticated synthetic biology approaches for BGC refactoring and expression [4] [5]. These innovations promise to further accelerate the discovery of novel bioactive compounds, reaffirming the value of natural products as an essential source of therapeutic agents and chemical probes.

The genome-first approach has fundamentally transformed our relationship with microbial chemical diversity, turning what was once a process of random exploration into a targeted engineering discipline. By beginning with the blueprint encoded in microbial genomes, researchers can now strategically access nature's full biosynthetic potential, revitalizing natural product discovery for the genomic age.

The advent of high-throughput genome sequencing has unveiled a profound disparity between the observed chemical output of microorganisms and their encoded biosynthetic potential. Filamentous fungi and bacteria, renowned for producing life-saving pharmaceuticals, harbor a vast reservoir of silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs)—genetic loci capable of producing novel natural products but which remain transcriptionally inactive under standard laboratory conditions [9] [10]. These cryptic or silent BGCs represent a formidable untapped resource for novel drug discovery, as their activation can yield previously unknown chemical scaffolds with potential therapeutic applications [11]. The systematic exploration of this hidden potential, driven by genome mining, is revolutionizing natural product research, moving it from traditional activity-guided screening to a targeted, gene-based discovery paradigm [10] [12]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the strategies and methodologies employed to unlock the chemical diversity encoded within these silent genetic reservoirs, framed within the broader context of advancing natural product discovery.

Quantitative Landscape of BGC Diversity

The scale of unexplored natural product diversity is immense. Large-scale genomic studies across various taxonomic groups have begun to quantify this potential, revealing that the majority of BGCs in any given genome are orphaned (not linked to a known compound) or silent [13] [10].

Table 1: BGC Diversity in Selected Genomic Studies

| Study Organism | Number of Genomes Analyzed | Total BGCs Detected | Average BGCs per Genome | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria & Relatives (Pleosporaceae) | 187 | 6,323 | 34 (Avg. for all genomes)29 (Avg. for Alternaria) | BGCs were grouped into 548 Gene Cluster Families (GCFs), with distribution patterns correlating with phylogeny [13]. |

| Marine Actinomycete (Salinispora) | 75 | Not Specified | Not Specified | Over 50% of identified BGCs were observed in only one or two strains, indicating extreme population-level diversity and recent acquisition via Horizontal Gene Transfer [10]. |

| Global Bacterial Analysis | 1,154 | >33,000 | ~28.6 (Average) | The vast majority of the >33,000 putative BGCs identified were uncharacterized, highlighting the vast undiscovered chemical space [10]. |

The distribution of BGCs is not random but often reflects phylogenetic relationships and ecological niches. For instance, a groundbreaking analysis of 187 genomes from the fungal family Pleosporaceae, which includes the genus Alternaria, revealed that the divergent sections Infectoriae and Pseudoalternaria possessed highly unique GCF profiles compared to other groups [13]. Furthermore, the critical alternariol (AOH) mycotoxin GCF was found to be restricted to Alternaria sections Alternaria and Porri, providing actionable intelligence for food safety monitoring [13]. This quantitative understanding allows researchers to prioritize taxa for bioprospecting based on genetic potential and novelty.

Computational Genome Mining for BGC Discovery

The first step in unlocking silent BGCs is their accurate identification and annotation from genomic data. This process, known as genome mining, relies on a suite of bioinformatics tools and databases designed to detect BGCs based on known biosynthetic logic [11].

Key Databases and Prediction Tools

A robust ecosystem of databases has been developed to support BGC discovery, which can be categorized by their focus [11]:

- Comprehensive Databases: Resources like the Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster (MIBiG) standard provide curated information on experimentally characterized BGCs and their molecular products, serving as a critical reference for linking genotypes to chemotypes [10] [11].

- Organism-Specific Databases: These target the BGC diversity of particular groups, such as the Streptomyces genome sequences, which are a major focus of natural product discovery [12].

- Specialized Metabolite Databases: Databases focusing on specific classes of metabolites, such as RiPPs (Ribosomally synthesized and Post-translationally modified Peptides) [11].

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for BGC Mining

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Application in Silent BGC Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [11] [12] | BGC Identification & Analysis | Detects known BGC classes using rule-based algorithms; predicts core biosynthetic structures and regulatory elements. | The primary tool for initial, comprehensive BGC prediction in bacterial and fungal genomes. A step-by-step protocol for its use in Streptomyces is available [12]. |

| PRISM [11] | BGC Identification & Chemical Prediction | Combines genomic analysis with chemical structure prediction for non-ribosomal peptides and polyketides. | Used to predict the likely chemical output of a BGC, helping prioritize clusters for experimental activation. |

| Machine Learning Models [11] | Novel BGC Prediction | Uses deep learning to identify BGCs beyond known rules, detecting patterns from training data. | Critical for discovering entirely novel BGC architectures that are missed by rule-based tools, expanding the scope of genome mining. |

| BiG-FAM [11] | BGC Classification | Groups BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) based on shared biosynthetic genes. | Enables comparative genomics to understand BGC distribution and evolutionary relationships across taxa. |

Workflow for Computational BGC Identification

The standard pipeline for identifying BGCs from a novel microbial genome involves a sequential process of sequencing, annotation, and targeted analysis. The following diagram visualizes this workflow, from raw DNA to prioritized BGCs.

As illustrated, the process begins with whole-genome sequencing, followed by unified gene prediction and annotation using pipelines like funannotate to ensure consistency [13]. The annotated genome is then subjected to BGC mining with tools like antiSMASH, which identifies clusters based on known biosynthetic rules [11] [12]. The final, crucial step is prioritization, where BGCs are grouped into GCFs and evaluated based on novelty, presence of regulatory genes, and similarity to clusters encoding desirable activities [13] [11].

Experimental Strategies for Activating Silent BGCs

Once silent BGCs are identified computationally, the central challenge becomes their experimental activation to link the genotype to a chemical product. The following diagram provides a high-level overview of the primary strategies employed.

Endogenous Non-Targeted Activation

This approach aims to trigger silent BGCs within the native host by altering the physiological or environmental conditions.

- The OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds) Approach: This method systematically varies cultivation parameters such as media composition, temperature, aeration, and time [9]. By subjecting a single strain to a multitude of fermentation conditions, researchers can mimic the environmental cues that may naturally trigger BGC expression.

- Co-cultivation: Growing the target organism in the presence of another microbe can induce chemical defense responses, leading to the activation of otherwise silent pathways [9]. This strategy recapitulates the ecological interactions that drive natural product biosynthesis in the environment.

Single-Target Activation

This strategy involves precise genetic manipulations designed to directly perturb the regulatory controls governing a specific BGC of interest [9].

- Overexpression of Pathway-Specific Activators: Identifying and overexpressing a positive transcription factor within the BGC can kick-start its expression [9] [12].

- Deletion of Repressive Regulators: Knocking out genes encoding transcriptional repressors that silence the cluster is an effective method for activation [9].

- Promoter Engineering: Replacing the native promoter of key biosynthetic genes with a strong, inducible promoter allows for direct, artificial control over cluster expression [9].

Heterologous Expression

Heterologous expression involves cloning the entire silent BGC into a genetically tractable surrogate host, such as Streptomyces coelicolor or S. lividans, which is optimized for natural product production [9] [12]. This method physically removes the BGC from its native regulatory context and places it in a host designed for high-level expression. While technically challenging, it is a powerful solution for BGCs in hosts that are slow-growing, uncultivable, or genetically recalcitrant.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials required for the genetic manipulation and activation of BGCs, particularly in model actinomycetes like Streptomyces.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for BGC Genetic Manipulation

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application in BGC Research |

|---|---|

| antiSMASH Pipeline [12] | A computational essential. This bioinformatics tool is the primary reagent for in silico identification and preliminary annotation of BGCs in a sequenced genome. |

| E. coli-Streptomyces Shuttle Vector [12] | A specialized plasmid capable of replicating in both E. coli (for cloning) and Streptomyces (for expression). Used for heterologous expression and genetic manipulations. |

| Conjugal Transfer System [12] | A method for transferring DNA from E. coli into Streptomyces. This is often more efficient than conventional transformation for introducing large BGC constructs. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System for Actinomycetes [11] | Enables targeted gene knock-outs (e.g., of repressive regulators) and precise promoter engineering, dramatically accelerating genetic manipulation. |

| Inducible Promoters (e.g., tipA, ermE*) | Strong, chemically inducible promoters used in promoter engineering strategies to drive the expression of key biosynthetic genes in a controlled manner. |

| Model Host Strains (e.g., S. coelicolor, S. lividans) [12] | Genetically minimized and optimized surrogate hosts used for heterologous expression of BGCs to overcome native host limitations. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: BGC Deletion inStreptomyces

The following step-by-step protocol, adapted from established methodologies, outlines a core genetic manipulation technique: in-frame gene deletion to validate the function of a biosynthetic gene or to remove a repressive regulator [12].

Application: Functional validation of a biosynthetic gene or activation of a silent BGC by deleting a repressor.

Materials:

- Donor E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002

- Receptor Streptomyces spores

- Shuttle vector (e.g., pKC1132) with temperature-sensitive origin

- Appropriate antibiotics for selection

- LB and SFM media

Procedure:

Vector Construction:

- Flanking regions (typically ~2 kb each) of the target gene are amplified via PCR.

- These fragments are cloned, using Gibson Assembly or traditional restriction-ligation, into the shuttle vector upstream and downstream of a selectable marker (e.g., apramycin resistance gene).

- The construct is verified by sequencing and then introduced into the donor E. coli strain.

Conjugal Transfer:

- Donor E. coli cells are grown to mid-log phase, washed, and resuspended to remove antibiotics.

- Receptor Streptomyces spores are germinated by heat shock and washed.

- Donor and receptor cells are mixed in a defined ratio, pelleted, and plated on SFM agar.

- After overnight incubation, the plate is overlaid with a selective antibiotic (e.g., apramycin) and an antibiotic to counterselect against the E. coli donor (e.g., nalidixic acid).

Screening and Verification:

- Exconjugants appear after 3-7 days. These are screened by PCR to identify double-crossover events where the target gene has been replaced by the resistance cassette via homologous recombination.

- Genomic DNA of potential mutants is isolated and analyzed by PCR with verification primers outside the homologous regions.

Phenotypic Analysis:

- The metabolic profile of the mutant strain is compared to the wild-type using analytical techniques like Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) to detect newly produced compounds resulting from the genetic manipulation.

The field of silent BGC activation is being propelled by the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning. While conventional tools like antiSMASH excel at finding known BGC types, emerging deep learning models are being trained to identify novel BGCs beyond predefined rules, uncovering an even greater breadth of biosynthetic diversity [11]. The future lies in combining these powerful predictive models with high-throughput genetic engineering and advanced analytical chemistry to systematically characterize the vast universe of cryptic natural products.

In conclusion, the reservoir of silent and cryptic BGCs represents the next frontier in natural product discovery. Through a multidisciplinary approach combining computational genomics, microbial genetics, and synthetic biology, researchers are now equipped to unlock this hidden potential. The methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide a roadmap for de-orphaning these clusters, paving the way for the discovery of novel chemical entities that will fuel the next generation of therapeutics and deepen our understanding of microbial chemical ecology.

Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) are sets of two or more genes that are physically clustered on a genome and work in concert to encode the biosynthesis of a specialized metabolite [14] [15]. These specialized metabolites, also known as natural products, are not essential for basic growth or reproduction but confer critical ecological advantages to the producing organisms, such as defense, communication, and nutrient acquisition [14] [10]. From a human perspective, these compounds are the source of a vast array of pharmaceuticals, including antibiotics, anticancer agents, and immunosuppressants [15] [10]. The discovery and characterization of BGCs have become a cornerstone of modern natural product research, enabling a shift from traditional activity-based screening to targeted genome mining for novel compounds [10] [11].

BGCs are widely found in bacteria, fungi, and some plants. In bacteria, they are often located in variable regions of the chromosome known as genomic islands, which are hotspots for genomic innovation [10]. The clustering of these genes, while not universal, is a common feature that is thought to facilitate coregulation and horizontal gene transfer (HGT), allowing beneficial metabolic pathways to spread through populations and across species [14] [10]. This mobility means BGCs can be studied as independent evolutionary entities, providing immediate functional capabilities to their new hosts [10].

Core Components of a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

A BGC is a genetic package that contains most, if not all, the genetic information required to produce a final specialized metabolite. While the exact composition varies, a canonical BGC typically includes several types of core components.

Core Biosynthetic Genes

These genes encode the enzymes responsible for constructing the basic scaffold or backbone of the metabolite. They are the defining feature of the cluster and determine the class of compound produced [16]. Key examples include:

- Polyketide Synthases (PKSs): These large, multi-functional enzymes act in an assembly-line fashion, successively adding acyl units to form complex polyketides [10].

- Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPSs): Similar to PKSs, NRPSs assemble peptides from amino acid building blocks without the direct involvement of ribosomes [10].

- Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs): This class involves a ribosomally synthesized precursor peptide that is extensively modified by tailoring enzymes [15].

- Terpene Cyclases: These enzymes catalyze the cyclization of terpene precursors into diverse ring structures [16].

Tailoring Enzymes

Genes encoding tailoring enzymes modify the core scaffold built by the backbone enzymes, significantly increasing the structural diversity and biological activity of the final product [13] [16]. Common tailoring enzymes include:

- Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases: Often involved in oxidation reactions.

- Methyltransferases: Catalyze the transfer of methyl groups.

- Glycosyltransferases: Attach sugar moieties.

- Acyltransferases: Add acyl groups.

Regulatory Genes

Many BGCs include dedicated transcription factors that regulate the expression of the cluster genes in response to environmental or developmental cues [16]. This ensures that metabolically costly compounds are produced only when needed.

Resistance and Transport Genes

To protect the host organism from its own toxic compounds, BGCs often include:

- Resistance Genes: These confer self-resistance, often by encoding proteins that modify the target site or otherwise detoxify the metabolite [10] [16].

- Transporters: Membrane transporters, such as ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters or major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters, are responsible for exporting the final product out of the cell [16].

Table 1: Core Components of a Typical Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

| Component Type | Key Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Backbone Enzyme | Synthesizes the basic molecular scaffold | PKS, NRPS, Terpene Cyclase [16] |

| Tailoring Enzyme | Modifies the scaffold to add chemical diversity | Methyltransferase, Glycosyltransferase, P450 monooxygenase [13] [16] |

| Regulatory Protein | Controls the expression of cluster genes | Pathway-specific transcription factor [16] |

| Resistance Gene | Protects the host from its own metabolite | Target-site modification enzyme [10] |

| Transporter | Exports the final product from the cell | ABC transporter, MFS transporter [16] |

The following diagram illustrates the typical organization of these core components within a BGC and their functional roles in producing the final metabolite.

Methodologies for BGC Discovery and Analysis

The process of discovering and characterizing BGCs, known as genome mining, involves a multi-step workflow that integrates bioinformatics, genetics, and analytical chemistry.

In Silico Prediction and Identification

The first step is the computational identification of BGCs within genome sequences.

- Tools and Databases: The most widely used tool is antiSMASH (Antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell), which uses rule-based algorithms to identify known and novel BGCs by comparing genomic regions against a database of characterized profiles [13] [11] [17]. Other tools include PRISM and DeepBGC, the latter leveraging machine learning to identify BGCs beyond known rules [11]. The MIBiG (Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster) repository serves as a critical community resource, providing a standardized data standard for annotated and experimentally characterized BGCs [15].

- Comparative Genomics: Identified BGCs are often grouped into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) using tools like BiG-SCAPE and BiG-SLiCE, which compare BGCs across multiple genomes based on sequence similarity [14] [18]. This allows researchers to prioritize BGCs that are novel or linked to desirable bioactivities.

Table 2: Key Bioinformatics Tools and Databases for BGC Discovery

| Tool/Database | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [13] [17] | BGC Prediction & Annotation | Rule-based detection of known BGC classes; most widely used platform |

| MIBiG [15] [13] | BGC Repository | Curated database of experimentally characterized BGCs with a community standard |

| BiG-SCAPE [18] | BGC Comparative Analysis | Groups BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) based on sequence similarity |

| BiG-SLiCE [14] | Large-Scale BGC Clustering | Highly scalable tool for clustering millions of BGCs into GCFs |

| DeepBGC [11] | Machine Learning-based Prediction | Uses deep learning to identify BGCs with features beyond known rules |

Experimental Characterization and Validation

Once a BGC of interest is identified, experimental work is required to link it to its encoded metabolite.

- Genetic Manipulation: The most direct method to validate BGC function is through gene knockout or knockout-complementation experiments. Inactivating a core biosynthetic gene (e.g., via homologous recombination or CRISPR-Cas9) should lead to the loss of metabolite production, while reintroducing the gene should restore it [10] [8]. In heterologous expression, the entire BGC is transferred into a well-characterized host strain (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor, Bacillus subtilis) that is easily cultured and genetically engineered [8] [19]. This strategy is particularly powerful for activating "cryptic" clusters that are silent in their native hosts [19].

- Metabolite Analysis: Following genetic manipulation, advanced analytical techniques, primarily mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, are used to detect, isolate, and elucidate the structure of the metabolic product [15] [10].

The following workflow summarizes the integrated process of genome mining and experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental characterization of BGCs relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for BGC Experimentation

| Reagent / Material | Function in BGC Research |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate amplification of BGC fragments for cloning or diagnostic PCR. |

| Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs) | Stable propagation of large, intact BGC DNA inserts in E. coli for heterologous expression [19]. |

| Methylation-Competent E. coli Strains | Host for propagating DNA that must be protected from restriction systems in actinomycetes. |

| Gateway or Gibson Assembly Cloning Kits | Modular assembly of large BGC DNA constructs for heterologous expression [8] [19]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid Systems | Targeted gene knockouts and edits within native BGCs in the host chromosome [8]. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems (e.g., Tet-On) | Controlled overexpression of pathway-specific regulators to activate silent BGCs [16]. |

| Specialized Heterologous Hosts (e.g., B. subtilis) | Engineered strains lacking competing BGCs for clean metabolite production and analysis [19]. |

| Silica Gel Chromatography Resins | Purification of specialized metabolites from culture extracts for structural elucidation. |

BGCs in Context: Diversity, Evolution, and Ecological Significance

BGCs are not static entities; their distribution and evolution provide deep insights into microbial ecology and adaptation.

- Phylogenetic Distribution and Diversity: The number and type of BGCs vary tremendously across taxa. A single fungal Alternaria genome can contain an average of 34 BGCs [13], while global analyses of marine bacteria have revealed many thousands [18]. This diversity is a reflection of evolutionary arms races and niche adaptation.

- Evolution and Horizontal Gene Transfer: BGCs are dynamic genomic elements. They can arise through gene duplication, genome rearrangement, and, importantly, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) [14]. Their frequent linkage to mobile genetic elements and their clustered nature support the "selfish operon" theory, which posits that clustering is maintained because it facilitates the coordinated transfer of beneficial traits [14] [10]. This HGT allows BGCs to move between even distantly related organisms, meaning their distribution often does not follow strict phylogenetic lines [10].

- Ecological Roles and Virulence: BGCs encode compounds that mediate critical organismal interactions. While many are beneficial as antibiotics, others function as virulence factors in pathogens. For example, ESKAPE pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii harbor BGCs for siderophores (iron-chelators) and other metabolites that enhance their pathogenicity [17]. Understanding these "harmful" BGCs is as important as discovering therapeutic ones.

Biosynthetic Gene Clusters are the genomic architects of chemical diversity in the microbial world. A thorough understanding of their core components—backbone enzymes, tailoring genes, regulators, and resistance mechanisms—provides the foundation for targeted genome mining. The integrated use of powerful bioinformatics tools and robust experimental protocols, including heterologous expression and genetic manipulation, enables researchers to move from a genome sequence to a characterized natural product. As the field advances, leveraging these approaches to explore understudied taxa and activate cryptic clusters will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of BGCs, driving forward the discovery of next-generation pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals.

The integration of targeted covalent inhibitors (TCIs) into genome mining workflows represents a paradigm shift in natural product discovery. This technical guide details how reactive warheads and binding moieties serve as bioactive "hooks" to efficiently isolate and characterize novel therapeutic compounds from biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). We provide a comprehensive overview of warhead chemistries, computational and experimental methodologies for their application, and data presentation standards essential for research and development professionals. By framing covalent targeting within the context of genome mining, this whitepaper outlines a strategic approach to overcome traditional screening limitations and accelerate drug development.

Natural product discovery is undergoing a renaissance, fueled by advanced genomic sequencing that has revealed a vast repository of uncharacterized biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [20]. The central challenge lies in the efficient prioritization and functional characterization of these BGCs. Targeted covalent inhibitors (TCIs), molecules designed to form a covalent bond with their protein target, offer a powerful solution [21] [22]. These inhibitors consist of two key components: a binding moiety that provides selective affinity through reversible interactions, and a reactive warhead that forms a covalent bond with a specific nucleophilic amino acid residue, dramatically enhancing binding affinity and duration of action [21] [23].

The process of genome mining excels at identifying similar BGCs based on key biosynthetic enzymes across multiple genomes [20]. By integrating knowledge of warhead-target residue interactions, researchers can use these bioactive features as "hooks" to fish for specific biological activities within complex genomic datasets. This approach moves beyond serendipitous discovery to a rational design strategy where warheads are installed on noncovalent scaffolds with high binding affinity to a target site, creating highly selective TCIs [21]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on leveraging these principles for efficient discovery, complete with methodologies, data standards, and visualization tools.

Covalent Warheads: Chemistry and Quantitative Reactivity

Warheads are the electrophilic functional groups that engage in covalent interactions with enzyme/receptor residues, either reversibly or irreversibly [21]. Their reactivity must be carefully balanced to achieve maximal target inhibition while minimizing off-target effects and toxicity [22].

Table 1: Common Covalent Warheads and Their Properties

| Warhead Class | Target Residue(s) | Reaction Mechanism | Reversibility | Example Compound(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamides | Cysteine | Michael Addition | Irreversible | Ibrutinib, Osimertinib [21] [23] |

| Cyanoacrylamides | Cysteine | Michael Addition | Reversible | N/A [23] |

| β-Lactams | Serine | Nucleophilic Substitution | Irreversible | Penicillin [21] |

| Sulfonyl Fluorides | Lysine, Tyrosine, Serine | Sulfur(VI) Fluoride Exchange (SuFEx) | Irreversible | N/A [22] |

| Chloroacetamides | Cysteine | Nucleophilic Substitution | Irreversible | N/A [21] |

| 2-Sulfonylpyridines | Cysteine | Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution (SNAr) | Irreversible | Covalent Adenosine Deaminase Modulator [23] |

| Nitrofurans | Cysteine | SNAr / Redox Activation | Irreversible | C-178 (STING inhibitor) [23] |

| Aldehydes | Lysine, Cysteine | Reversible Addition | Reversible | N/A [21] |

The kinetics of covalent inhibitors are unique and described by a two-step mechanism (Figure 1). The initial, reversible binding step is characterized by the dissociation constant (Kᵢ). This is followed by the covalent bond formation step, characterized by the rate constant kᵢₙₐcₜ [21] [22]. The overall efficiency of covalent inhibition is captured by the second-order rate constant (kᵢₙₐcₜ/Kᵢ), which should be maximized for potency, analogous to minimizing Kᵢ for non-covalent inhibitors [21].

Figure 1. Covalent Inhibition Two-Step Mechanism. The inhibitor (I) first forms a reversible complex (EI) with the enzyme (E). A subsequent, slower step leads to covalent bond formation. For irreversible inhibitors, the reverse reaction rate (k₋₂) is near zero [21] [22].

Cysteine is the most frequently targeted residue due to the high nucleophilicity of its thiolate group when deprotonated [23]. However, warheads targeting other residues like lysine, serine, and tyrosine are expanding the druggable proteome, with 16 out of 21 amino acids now known to be covalently targeted [21]. Warheads such as sulfonyl fluorides are particularly useful for targeting tyrosine residues flanked by basic amino acids or pKa-perturbed lysines, demonstrating how protein micro-environment fine-tunes warhead reactivity and selectivity [22].

Experimental Protocols: From Warhead Screening to Validation

Covalent Docking and Virtual Screening

Computational methods are indispensable for the rational design of TCIs. Covalent docking protocols predict the binding conformation of covalent inhibitors by simulating the geometry of the covalent complex.

Protocol: Covalent Docking with CovalentInDB [21] [22]

- Target and Residue Selection: Identify a solvent-accessible, non-conserved nucleophilic residue (e.g., Cys, Lys) near a druggable pocket.

- Warhead Selection: Query databases like WHdb, CovPDB, or CovalentInDB to identify warheads with known reaction mechanisms for the target residue [21].

- Structure Preparation: Obtain the target protein structure (PDB). Prepare the structure by adding hydrogens, assigning bond orders, and optimizing the protonation state of the target residue.

- Covalent Complex Generation: Define the reactive residue and warhead in the docking software. The docking algorithm will generate poses that position the warhead for covalent bond formation, often sampling different rotamers of the target residue.

- Scoring and Ranking: Score the generated poses using energy functions that account for the covalent bond geometry and non-covalent interactions in the binding pocket. Top-ranked compounds proceed to experimental validation.

Alternative Approach: Reactive Docking for "Inverse Drug Discovery" This method uses proteomics data to train predictive models for screening entire compound libraries based on desired phenotypes, ideal for early-stage discovery when target structure may be unknown [22].

Kinetic Analysis of Covalent Inhibition

Determining the kinetics of covalent modification is crucial for evaluating inhibitor potency and selectivity.

Protocol: Determining kᵢₙₐcₜ and Kᵢ [21] [22]

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a solution of the target enzyme at a concentration significantly below the expected Kᵢ.

- Time-Dependent Inhibition: Pre-incubate the enzyme with a range of inhibitor concentrations for varying time periods (t).

- Residual Activity Measurement: At each time point, dilute the reaction mixture significantly (e.g., 100-fold) into a buffer containing substrate at saturating concentration ([S] >> Kₘ) to measure residual enzyme activity (v).

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the natural logarithm of residual activity (ln(vₜ/v₀)) against time for each inhibitor concentration. The slope of each line is the observed inactivation rate (kₒbₛ) at that concentration.

- Plot kₒbₛ against the inhibitor concentration ([I]). The data are fit to the equation: kₒbₛ = kᵢₙₐcₜ [I] / (Kᵢ + [I]).

- The second-order rate constant for inactivation is kᵢₙₐcₜ/Kᵢ.

Proteome-Wide Selectivity Profiling

A critical step in TCI development is assessing off-target reactivity to minimize toxicity.

Protocol: Assessing Off-Target Effects with MS-Based Proteomics [22]

- Compound Treatment: Treat a representative cell line (e.g., Hep G2) or tissue lysate with the covalent inhibitor candidate, using a DMSO vehicle as a control.

- Protein Extraction and Digestion: Lyse cells, extract proteins, and digest the proteome into peptides using a protease like trypsin.

- Enrichment and Labeling (Optional): Enrich for cysteine-containing peptides using thiol-reactive probes. Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) labeling can enable multiplexed experiments.

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Analyze the peptides via LC-MS/MS to identify and quantify modified peptides.

- Data Analysis: Compare peptide abundances between treated and control samples. Significant enrichment in the treated sample indicates a covalent modification event. Identify off-targets by mapping peptides back to their proteins of origin.

Data Presentation and Visualization Standards

Clear presentation of quantitative data and complex relationships is essential for scientific communication.

Table 2: Second-Order Rate Constants (kᵢₙₐcₜ/Kᵢ) for Representative Covalent Warheads

| Inhibitor Name | Target Protein | Warhead | Target Residue | kᵢₙₐcₜ/Kᵢ (M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibrutinib | Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) | Acrylamide | Cys 481 | 1.2 x 10³ [23] |

| Osimertinib | EGFR (T790M) | Acrylamide | Cys 797 | 4.7 x 10⁴ [21] |

| THZ1 | CDK7 | Acrylamide | Cys 312 | 1.9 x 10² [23] |

| Sulfonyl Fluoride Probe | Model Kinases | Sulfonyl Fluoride | Lys/Lys/Tyr | Varies by target [22] |

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Fragment Libraries | Screening for initial hits against a target residue. | Small molecules (150-300 Da) decorated with mild electrophilic warheads (e.g., acrylamides, sulfonyl fluorides) [22]. |

| Warhead Databases (WHdb, CovPDB) | Informing rational warhead selection. | Curate information on warhead-target pairs, reaction mechanisms, and PDB complexes [21]. |

| Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) Probes | Proteome-wide profiling of warhead reactivity and target engagement. | Contain a warhead, a reporter tag (e.g., biotin, fluorophore), and a linker [22]. |

| Glutathione (GSH) | Experimental assessment of warhead reactivity. | A biological nucleophile used to measure non-specific reactivity and estimate inherent warhead electrophilicity [22]. |

| Cell Painting Assay Kits | Phenotypic screening and MoA prediction. | Uses fluorescent dyes to label cellular components; morphological changes are analyzed to predict bioactivity [24]. |

The following workflow diagram (Figure 2) integrates the concepts of genome mining with covalent inhibitor discovery, illustrating the strategic use of bioactive "hooks."

Figure 2. Integrated Workflow for Covalent Natural Product Discovery. This pathway outlines the process from genome mining to covalent lead identification, highlighting the two primary design strategies for TCIs [21] [22] [20].

The strategic integration of reactive warheads and binding moieties as bioactive "hooks" provides a powerful framework for efficient discovery in the genomic era. By moving from serendipitous finding to rational design, researchers can leverage the extensive toolkit of covalent warheads, computational methods, and experimental protocols outlined in this guide to rapidly characterize and target novel BGCs. The future of this field lies in the continued expansion of novel warhead chemistries, the refinement of predictive computational models, and the deeper integration of phenotypic profiling with genomic data. This approach holds immense promise for unlocking the dark matter of natural products and delivering the next generation of therapeutics.

Advanced Genome Mining Toolkits: Strategies, Algorithms, and Real-World Applications

The declining discovery rate of novel bioactive compounds from traditional natural product discovery pipelines has necessitated a paradigm shift towards genome-guided approaches. Microbial genomes are treasure troves of biosynthetic potential, harboring a vast number of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that encode for structurally diverse natural products with pharmaceutical relevance. The core bioinformatics platforms—antiSMASH, BAGEL, and PRISM—have emerged as indispensable tools for systematically identifying and characterizing these BGCs directly from genomic data, enabling researchers to prioritize the most promising candidates for experimental validation [25] [26]. These tools have fundamentally transformed natural product discovery from a serendipitous process to a rational, target-driven endeavor.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these three core platforms, detailing their underlying methodologies, complementary strengths, and practical implementation. By framing their use within a comprehensive genome mining workflow, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge to leverage these tools for accelerated discovery of novel therapeutic agents. The integration of these platforms has proven particularly valuable for exploring understudied microbial taxa and metagenomic assemblies, where chemical diversity often remains largely untapped [26].

antiSMASH (Antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis SHell)

antiSMASH represents the most widely adopted platform for the initial detection and annotation of BGCs across bacterial, archaeal, and fungal genomes [27]. This tool employs a rule-based system that utilizes manually curated profile hidden Markov models (pHMMs) to identify signature biosynthetic domains and genes associated with secondary metabolism.

- Detection Mechanism: antiSMASH version 7 incorporates detection rules for 81 distinct BGC types, a significant expansion from the 71 types covered in previous versions [27]. The platform scans input genomic sequences against a comprehensive library of pHMMs from databases including PFAM, TIGRFAM, SMART, and custom models to identify core biosynthetic enzymes.

- Key Enhancements: Recent versions have introduced dynamic Python-coded detection profiles for specific motifs too small for reliable pHMM detection, such as the cyanobactin precursor motif M.KKN[IL].P….PV.R [27]. Additional improvements include enhanced NRPS/PKS annotation through updated substrate prediction libraries (NRPyS) and the integration of Trans-AT PKS-specific KS domain annotations via transATor [27].

- Visualization and Analysis: antiSMASH 7 provides new visualizations for NRPS and PKS assembly lines in conventional publication style, filterable gene tables for rapid cluster inspection, and comparative analysis features like CompaRiPPson for evaluating RiPP precursor novelty against database entries [27].

PRISM (PRediction Informatics for Secondary Metabolomes)

PRISM distinguishes itself through its advanced chemical structure prediction capabilities, moving beyond BGC detection to generate putative chemical structures for genomically encoded natural products [28] [26]. This platform employs a chemical graph-based approach that models natural product scaffolds as interconnected subgraphs, enabling the prediction of both modular and non-modular biosynthetic classes.

- Structure Prediction Mechanism: Unlike linear module-based approaches, PRISM represents residues and functional groups as chemical subgraphs, with tailoring enzymes catalyzing virtual reactions that create or break bonds between these subgraphs [28]. This framework supports prediction for 16 classes of secondary metabolites, including nonribosomal peptides, polyketides, RiPPs, aminoglycosides, β-lactams, and phosphonates [26].

- Comprehensive Reaction Library: PRISM 4 implements 618 in silico tailoring reactions and utilizes 1,772 hidden Markov models to connect biosynthetic genes to their catalytic functions, enabling the in silico reconstruction of complete biosynthetic pathways [26]. The platform accounts for substrate ambiguity by generating combinatorial libraries of predicted structures when enzymatic specificity cannot be unambiguously determined.

- Validation Performance: In benchmark assessments, PRISM 4 detected 96% of a curated set of 1,281 BGCs with known products and generated structure predictions for 94% of the detected clusters [26]. The predicted structures showed significant chemical similarity to known products, with an average maximum Tanimoto coefficient of 0.81 across validation datasets [28] [26].

BAGEL

BAGEL is a specialized genome mining platform focused exclusively on the identification of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) [27]. This tailored focus allows BAGEL to provide sensitive detection and accurate annotation of RiPP BGCs, which are often overlooked by more generalist tools.

- Detection Mechanism: BAGEL utilizes a library of pHMMs and sequence motifs specifically designed to identify RiPP precursor peptides and their associated modification enzymes [27]. The platform excels at recognizing the characteristic genetic architecture of RiPP BGCs, which typically consist of a small precursor peptide gene and adjacent modification enzyme genes.

- Complementary Function: While antiSMASH and PRISM cover a broader spectrum of BGC classes, BAGEL provides specialized sensitivity for RiPP discovery and is integrated into the antiSMASH analysis pipeline for comprehensive BGC detection [27].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Core Bioinformatics Platforms for BGC Prediction

| Platform | Primary Function | BGC Classes Covered | Key Methodology | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | BGC detection & annotation | 81 cluster types | pHMM-based detection with rule-based classification | Most comprehensive detection; user-friendly web interface; integrates multiple databases |

| PRISM | Chemical structure prediction | 16 metabolite classes | Chemical graph-based prediction with virtual reactions | Predicts complete chemical structures; handles both modular and non-modular biosynthesis |

| BAGEL | RiPP-specific detection | Ribosomally synthesized peptides | Specialized pHMMs for RiPP recognition | High sensitivity for RiPP BGCs; complementary to broader platforms |

Experimental Protocols for BGC Analysis

Comprehensive BGC Detection Using antiSMASH

Protocol Objective: To identify and annotate biosynthetic gene clusters in microbial genome sequences using antiSMASH.

Input Requirements: Microbial genomic data in FASTA, GenBank, or EMBL format. For accurate annotation, ensure the sequence data is of high quality (high coverage, minimal contamination).

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Obtain genome sequence of the target organism. For draft genomes, consider scaffolding to improve BGC detection continuity. For metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), ensure adequate completeness and contamination estimates.

- Tool Execution:

- Access the antiSMASH web server (https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org/) or install the standalone version.

- Upload genomic sequence file and specify the taxonomic classification (Bacteria, Archaea, or Fungi) to enable lineage-specific detection rules.

- Select appropriate analysis modules based on target BGC classes. For comprehensive analysis, enable all available detection options.

- For NRPS/PKS clusters, enable the detailed analysis options to obtain substrate specificity predictions and module organization.

- Output Interpretation:

- Review the HTML output to identify detected BGCs, their types, and genomic locations.

- Examine the ClusterCompare and KnownClusterBlast results to identify similarities to characterized BGCs in databases.

- For RiPP clusters, utilize the CompaRiPPson analysis to assess precursor peptide novelty against database entries [27].

- For NRPS/PKS clusters, analyze the domain architecture and substrate predictions to hypothesize about potential structural features.

Technical Notes: antiSMASH version 7 introduces a filterable gene table for each region, allowing researchers to quickly identify specific genes of interest based on name, biosynthetic type, or functional annotation [27]. The platform also now provides visualization of transcription factor binding sites using the LogoMotif database, offering insights into potential regulatory mechanisms [27].

Chemical Structure Prediction Using PRISM

Protocol Objective: To predict the chemical structures of natural products encoded by identified BGCs.

Input Requirements: BGC sequences in GenBank format or microbial genomes in FASTA format. PRISM can utilize antiSMASH output files directly through its sideloading functionality.

Methodology:

- Data Input: Provide genomic sequence containing target BGCs. This can be a complete genome, a genomic region containing the BGC, or antiSMASH output files.

- Analysis Configuration:

- Specify the classes of natural products for focused analysis or enable comprehensive detection for all supported classes.

- For NRPS/PKS clusters, enable the detailed assembly-line analysis to predict backbone structures.

- For combinatorial classes, determine the appropriate balance between prediction comprehensiveness and computational burden.

- Structure Elucidation:

- PRISM generates chemical structure predictions by applying its virtual reaction library to the identified biosynthetic enzymes [28].

- For classes with ambiguous tailoring reactions, PRISM generates combinatorial libraries representing all possible structural permutations.

- The platform outputs predicted structures in SMILES format and provides chemical descriptors for similarity analysis.

- Validation and Prioritization:

- Calculate chemical similarity between predicted structures and known natural products using Tanimoto coefficients or other metrics.

- Assess natural product-likeness using dedicated scoring algorithms [26].

- Evaluate structural complexity and drug-likeness parameters to prioritize leads for experimental investigation.

Technical Notes: Benchmark analyses indicate that PRISM 4 generates structurally complex, natural product-like predictions that more closely resemble known natural products compared to other tools [26]. The maximum Tanimoto coefficient between predicted and true structures often exceeds the median, highlighting the importance of examining the complete combinatorial output [28].

Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive BGC Analysis

Protocol Objective: To combine multiple platforms for synergistic BGC discovery and characterization.

Methodology:

- Primary Detection: Use antiSMASH for initial BGC detection and annotation across all major classes. This provides comprehensive coverage of biosynthetic potential in the target genome.

- Specialized Analysis:

- For RiPP BGCs, utilize BAGEL for sensitive detection and precise annotation of precursor peptides and modification enzymes.

- For modular NRPS/PKS clusters, employ PRISM for detailed structure prediction, leveraging its updated NRPyS library for improved substrate specificity predictions [27].

- For non-modular natural products (aminocoumarins, bisindoles, phosphonates, etc.), PRISM's chemical graph-based approach provides unique predictive capabilities [28].

- Structure-Activity Relationship Analysis:

- Convert predicted structures to chemical descriptors or fingerprints.

- Apply machine learning models to predict potential biological activities based on structural features [29].

- Prioritize BGCs based on predicted novelty, structural properties, and potential bioactivities.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for BGC Prediction

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Database | Function in BGC Analysis | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| BGC Databases | MIBiG (Minimum Information about a BGC) | Repository of experimentally characterized BGCs for comparison | https://mibig.secondarymetabolites.org/ |

| Specialized Prediction Tools | DeepBGC | Random forest classifier for BGC detection and product class prediction | Standalone tool or antiSMASH integration |

| Structure Prediction | NaPDoS2 (Natural Product Domain Seeker) | Phylogenetic analysis of PKS KS and NRPS C domains | Web server |

| Activity Prediction | Machine Learning Classifiers | Prediction of antibacterial, antifungal, or cytotoxic activity from BGC features | Custom scripts [30] |

| Chemical Databases | Natural Products Atlas | Curated database of known natural products for dereplication | https://www.npatlas.org/ |

Workflow Visualization and Integration

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for comprehensive BGC analysis using the core bioinformatics platforms:

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for BGC prediction and analysis. The core platforms function synergistically to provide comprehensive BGC detection and characterization.

Advanced Applications and Emerging Methodologies

Machine Learning-Enhanced BGC Analysis

Recent advances have integrated machine learning approaches with traditional rule-based BGC detection to improve prediction accuracy and enable novel functionalities. Deep self-supervised learning methods, such as BiGCARP (Biosynthetic Gene Convolutional Autoencoding Representations of Proteins), represent BGCs as sequences of functional protein domains and train masked language models to learn meaningful representations of BGCs and their constituent domains [25]. These approaches demonstrate improved performance in both BGC detection and product classification compared to purely homology-based methods.

Activity prediction models represent another significant advancement, enabling researchers to prioritize BGCs based on predicted biological activities. By extracting feature vectors from BGC sequences (including PFAM domains, resistance genes, and sub-PFAM domains identified through sequence similarity networks), machine learning classifiers can predict the likelihood of antibacterial, antifungal, or cytotoxic activity with accuracies up to 80% in some cases [29] [30]. Implementation scripts for these models are publicly available, allowing integration with antiSMASH and RGI (Resistance Gene Identifier) outputs [30].

Specialized Mining for Underrepresented BGC Classes

Emerging methodologies address the challenge of detecting atypical BGCs that may be overlooked by standard detection rules. For fungal genome mining, tools like FunBGCeX (Fungal BGC eXtractor) have been developed to identify BGCs encoding "domainless enzymes" - biosynthetic proteins that lack detectable Pfam domains and are consequently not recognized by conventional tools [31]. This approach has enabled the discovery of novel fungal triterpenoids and associated biosynthetic mechanisms that would have remained hidden using standard detection pipelines.

Similarly, targeted mining for specific chemical classes can be achieved by focusing on signature enzymes or biosynthetic logic. For example, mining for BGCs encoding both Pyr4-family terpene cyclases and squalene-hopene cyclases has led to the discovery of previously unreported fungal onoceroid triterpenoids [31]. These specialized approaches complement the comprehensive detection provided by platforms like antiSMASH and PRISM, enabling researchers to explore specific corners of natural product chemical space.

The integrated use of antiSMASH, BAGEL, and PRISM provides a powerful framework for comprehensive BGC prediction and characterization in microbial genomes. Each platform brings unique capabilities to the genome mining workflow: antiSMASH offers the most extensive BGC detection coverage, BAGEL provides specialized sensitivity for RiPP identification, and PRISM enables unprecedented chemical structure prediction for diverse natural product classes. As these platforms continue to evolve—incorporating machine learning, expanding BGC class coverage, and improving prediction accuracy—they will play an increasingly vital role in unlocking the vast, untapped chemical diversity encoded in microbial genomes for drug discovery and natural product research.

The relentless pursuit of novel natural products (NPs) has entered a transformative era with the advent of orthogonal mining strategies. This sophisticated approach moves beyond traditional biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) analysis to integrate multiple layers of genetic information, creating a powerful framework for targeted discovery. Orthogonal mining simultaneously examines disparate genetic elements—including resistance, transport, and regulatory genes—that are functionally linked to NP biosynthesis but reside outside core biosynthetic machinery. This multidimensional analysis provides critical functional insights that significantly enhance the prioritization of BGCs for experimental characterization, addressing a fundamental challenge in modern NP research where the vast majority of BGCs remain orphaned (lacking linked products) [32].

The strategic importance of orthogonal approaches lies in their ability to generate corroborating evidence for BGC functionality through multiple independent genetic channels. Where conventional mining might focus solely on identifying conserved biosynthetic domains, orthogonal mining incorporates contextual genetic markers that signal biological activity, host interaction, and ecological function. This methodology is particularly valuable for addressing the prioritization crisis in NP discovery; with an estimated 16,984 gene cluster families identified across bacterial genomes and commercial synthesis costs approximating $0.09 per base pair, the financial and logistical barriers to experimental characterization are substantial [32]. Orthogonal mining provides a rational triage system, focusing research efforts on the most promising BGCs with multiple independent genetic indicators of functionality and novelty.

Theoretical Foundation of Orthogonal Approaches

The Genetic Architecture of Natural Product Biosynthesis

Natural product biosynthetic pathways typically exist as self-contained genetic modules with coordinated functional components. Beyond the core biosynthetic enzymes (e.g., non-ribosomal peptide synthetases [NRPS] and polyketide synthases [PKS]), these clusters often include:

- Resistance genes: Protect the host organism from its own toxic compounds

- Transport genes: Facilitate compound secretion and cellular distribution

- Regulatory genes: Control cluster expression in response to environmental or physiological cues

The evolutionary conservation of these accessory genes within BGC contexts provides the fundamental premise for orthogonal mining. Their co-localization with biosynthetic machinery is non-random, reflecting functional interdependence that has been maintained through evolutionary selection. This genetic architecture creates multiple entry points for cluster identification and functional prediction beyond analysis of core biosynthetic components alone [32] [33].

Principles of Orthogonality in Genomic Analysis

Orthogonal mining employs independent but complementary lines of evidence to build confidence in BGC predictions. Each genetic element provides a distinct perspective on cluster functionality:

- Resistance genes indicate biological activity and potential mode of action

- Transport genes suggest environmental interaction and cellular processing

- Regulatory genes reveal expression dynamics and ecological context

This tripartite analysis creates a robust predictive framework where convergence of evidence from multiple genetic domains strongly indicates a functional, specialized metabolite pathway. The orthogonality principle ensures that predictions are not reliant on a single type of genetic evidence, reducing false positives and providing deeper functional insights than unitary approaches [32].

Targeting Resistance Genes for Mode-of-Action Prediction

Theoretical Basis and Strategic Value

Resistance genes confer protection to the producer organism against its own bioactive metabolites, making them exceptional predictors of biological activity and molecular targets. These genes typically encode either drug-modified targets with reduced binding affinity, efflux systems, or drug-inactivating enzymes. Their co-localization with BGCs provides direct insight into the compound's mechanism of action, effectively revealing the cellular process or molecular structure that the metabolite disrupts [32]. This approach transforms BGC prioritization from structural prediction to functional prediction, enabling researchers to focus on clusters with desired biological activities before compound isolation.

Methodological Framework

Table 1: Experimental Protocol for Resistance Gene Mining

| Step | Protocol Description | Key Tools/Techniques | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identification | Scan flanking regions of BGCs for known resistance motifs | antiSMASH, PRISM, custom HMM profiles | Catalog of putative resistance genes co-localized with BGCs |

| 2. Validation | Heterologous expression in model organisms | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, B. subtilis transformation | Confirmed resistance phenotype against putative target classes |

| 3. Mechanistic Analysis | Characterize resistance mechanism through biochemical assays | Enzyme activity assays, binding studies, transcriptomics | Elucidation of molecular resistance strategy (target modification, efflux, inactivation) |

| 4. Correlation | Link resistance mechanism to potential compound mode of action | Bioinformatics correlation, structural modeling | Predicted molecular target for the encoded natural product |

Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential process for mining and validating resistance genes associated with BGCs:

Exploiting Transport Genes for Bioactivity Insights

Functional Significance in BGC Context

Transport genes integrated within BGCs provide crucial information about compound localization and host interaction dynamics. These genes typically encode efflux pumps, membrane transporters, or secretion systems that govern the spatial distribution of the natural product. Their presence indicates active environmental interaction, suggesting the compound functions in intercellular communication, competitive inhibition, or environmental modification. Analysis of transporter identity and specificity can predict cellular targets (intracellular vs. extracellular) and potential bioactivity profiles [32] [34].

Experimental Methodology

Table 2: Transport Gene Analysis Framework

| Component | Analysis Method | Information Gained | Downstream Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transporter Classification | Transporter family analysis (TCDB) | Substrate specificity (ions, peptides, sugars) | Bioactivity class prediction |

| Membrane Topology | Transmembrane domain prediction | Subcellular localization | Target site prediction (membrane vs. intracellular) |

| Expression Profiling | RNA-seq under inducing conditions | Regulation dynamics and ecological context | Cultivation condition optimization |

| Functional Characterization | Gene knockout and complementation | Compound accumulation and toxicity | Production strain engineering |

Implementation Pathway

The strategic integration of transport gene analysis follows this logical progression:

Regulatory Gene Analysis for Expression Activation

Regulatory Networks in BGC Expression

Regulatory genes embedded within BGCs serve as expression control points that activate biosynthesis under specific environmental or developmental conditions. These elements include pathway-specific regulators, sigma factors, two-component systems, and quorum-sensing components that integrate cluster expression with broader physiological programs. Regulatory gene analysis provides insights into the ecological function of the natural product and enables strategies to activate silent (cryptic) clusters through simulated environmental cues or genetic manipulation [33] [34].

Protocol for Regulatory Gene Exploitation

Table 3: Regulatory Gene Mining and Activation Strategies

| Step | Objective | Technical Approach | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulator Identification | Discover regulatory elements within BGC | Promoter motif analysis, regulator domain identification | Catalog of potential pathway-specific regulators |

| Expression Correlation | Link regulator expression to product synthesis | Dual RNA-seq of regulator and biosynthetic genes | Expression correlation coefficients |

| Heterologous Regulator Expression | Activate silent BGCs in native hosts | CRISPRa, constitutive promoter swap | Metabolite production levels (LC-MS) |

| Signal Molecule Identification | Discover natural inducers | Co-culture, conditioned media, chemical screening | Induction fold-change relative to baseline |

Workflow for Regulatory Network Exploitation

The process for leveraging regulatory genes to activate and study BGCs involves:

Integrated Orthogonal Mining Workflow

Unified Analytical Pipeline

The full power of orthogonal mining emerges from the integrative analysis of all three genetic components simultaneously. This comprehensive approach generates a multi-parameter prioritization score that predicts both novelty and bioactivity before experimental characterization. The unified workflow combines computational prediction with experimental validation in an iterative design that continuously improves prioritization algorithms [32] [33] [35].

Comprehensive Experimental Design

Table 4: Integrated Orthogonal Mining Protocol

| Phase | Activities | Tools/Platforms | Decision Gates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Triage | BGC identification, Resistance/transport/regulatory gene annotation, Phylogenetic analysis | antiSMASH, PRISM, DeepBGC, custom scripts | BGC novelty score, Genetic context completeness |

| Priority Ranking | Multi-parameter scoring, Mode-of-action prediction, Expression potential assessment | Machine learning classifiers, Similarity networks | Prioritized BGC list for experimental work |

| Experimental Validation | Heterologous expression, Regulatory manipulation, Metabolite analysis, Bioactivity testing | CRISPR, Expression hosts (E. coli, Streptomyces), LC-MS/MS, Phenotypic assays | Compound detection, Bioactivity confirmation |

| Iterative Refinement | Model retraining with new data, Priority score adjustment | Continuous learning systems | Improved prediction accuracy |

Complete Orthogonal Mining System

The comprehensive orthogonal mining strategy integrates all genetic elements into a unified discovery pipeline:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Orthogonal Mining Implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Experimental Function | Example Sources/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|