From Molecules to Networks: Mathematical Modeling Approaches for Decoding Cellular Organization in Systems Biology

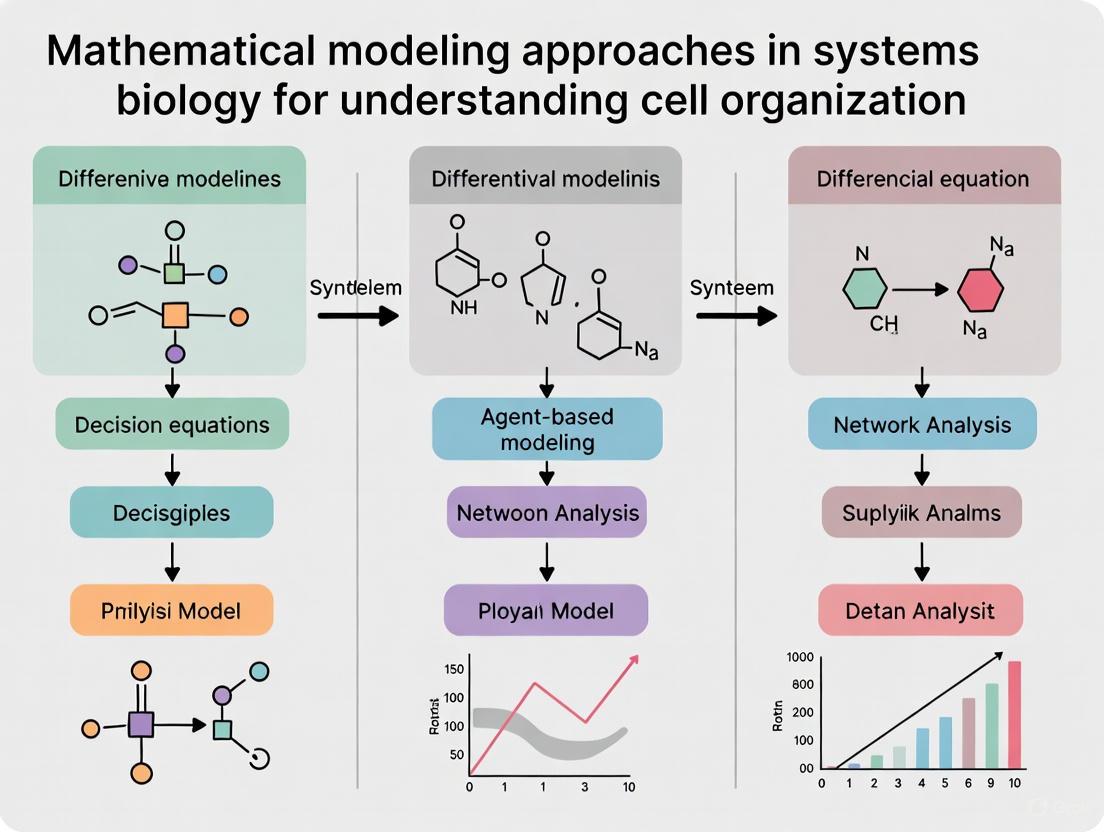

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mathematical modeling approaches used to understand the complex organization of cells, from intracellular signaling to multicellular structures.

From Molecules to Networks: Mathematical Modeling Approaches for Decoding Cellular Organization in Systems Biology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of mathematical modeling approaches used to understand the complex organization of cells, from intracellular signaling to multicellular structures. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational concepts, diverse methodological applications, and strategies for tackling computational challenges like model uncertainty and reproducibility. The content synthesizes current research and emerging trends, including the use of AI and multi-scale frameworks, to illustrate how quantitative models generate testable hypotheses, enhance predictive certainty, and offer profound implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The Conceptual Framework: How Mathematical Models Represent Biological Complexity

The integration of computational modeling with experimental biology has ushered in a new era of multiscale systems biology, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of biological complexity. The "Modeling and Analysis of Biological Systems" (MABS) study section formally defines this scope as spanning from molecular to population levels, representing a holistic framework for investigating biological organization [1]. This paradigm shift moves beyond reductionist approaches to embrace the integrative analysis of biological systems, where the interplay between scales—from genes and proteins to cells, tissues, and entire organs—creates emergent properties that cannot be understood by studying components in isolation. Within this framework, mathematical modeling serves as the critical bridge connecting theoretical understanding with empirical validation, providing researchers with powerful tools to decipher the organizational principles governing cellular behavior across spatial and temporal dimensions.

The core challenge in multiscale systems biology lies in developing unifying theoretical frameworks that can seamlessly connect biological phenomena across vastly different scales of organization. Recent research emphasizes developing "human interpretable grammar" to encode multicellular systems biology models, aiming to democratize virtual cell laboratories and make sophisticated modeling accessible to broader scientific communities [2]. This approach facilitates the creation of more accurate predictive computational models that can accelerate research in critical areas such as immunology, cancer biology, and therapeutic development. By establishing formal representations of cell behaviors and interactions, researchers can build more sophisticated in silico representations of biological reality that account for the complex, non-linear relationships characterizing living systems from molecular to organ levels.

Table: Fundamental Modeling Approaches in Multiscale Systems Biology

| Modeling Approach | Mathematical Foundation | Primary Biological Application Scale | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic Models | Differential Equations (ODEs/PDEs) | Molecular Networks, Tissue-level Phenomena | Predicts system behavior without random variation; suitable for large populations [1] |

| Stochastic Methods | Probability Theory, Random Processes | Cellular Processes, Molecular Interactions | Captures inherent randomness in biological systems; essential for small particle counts [1] |

| Mechanistic Modeling | First Principles, Biochemical Rules | Molecular Pathways, Cellular Decision Making | Based on physical/biological mechanisms; high predictive power for untested conditions [1] |

| Phenomenological Modeling | Regression, Curve Fitting | Organ-level Function, Population Dynamics | Describes observed behavior without mechanistic assumptions; useful when mechanisms unknown [1] |

| Agent-Based Modeling | Rule-Based Simulations, State Machines | Multicellular Systems, Tissue Organization | Captures emergent behaviors from individual cell interactions; spatial explicit [2] |

Mathematical Foundations and Multi-Scale Integration

The mathematical underpinnings of systems biology encompass both continuous and discrete methodologies that enable researchers to formalize biological knowledge into computable frameworks. Continuous models, typically implemented through ordinary or partial differential equations, excel at describing the dynamics of molecular concentrations and spatial gradients across tissues [1]. These approaches are particularly valuable for modeling metabolic networks, signal transduction cascades, and morphogen gradient formation. Discrete models, including Boolean networks and finite state machines, provide powerful alternatives for capturing logical relationships in gene regulatory networks and cellular decision-making processes where precise kinetic parameters may be unavailable. The integration of these approaches through multi-scale modeling frameworks creates a powerful paradigm for connecting molecular events to higher-order physiological phenomena.

A critical advancement in this field is the development of spatial-temporal analysis methods that explicitly account for the geometrical and organizational principles of biological systems. These approaches recognize that spatial constraints and organizational patterns significantly influence cellular behavior across scales—from the subcellular compartmentalization of molecular interactions to the tissue-level organization of cell populations [1]. Techniques such as mechanistic modeling leverage established biological mechanisms to build predictive frameworks, while phenomenological modeling captures observed behaviors when underlying mechanisms remain incompletely characterized [1]. The synergy between these approaches enables researchers to construct increasingly sophisticated models that balance biological realism with computational tractability, ultimately supporting more accurate predictions of system behavior under both normal and pathological conditions.

Data Visualization and Quantitative Analysis Methods

Effective data representation methodologies are essential for interpreting the complex relationships within multiscale biological systems. The strategic selection of visualization approaches directly impacts how researchers identify patterns, communicate findings, and generate new hypotheses. According to data visualization research, different visual encodings serve distinct analytical purposes: line graphs excel at displaying trends over continuous time, bar charts facilitate categorical comparisons, scatter plots reveal correlations between variables, and heatmaps visualize complex multivariate relationships through color gradients [3] [4]. The foundational principle of maximizing the "data-ink ratio"—prioritizing pixels that convey meaningful information over decorative elements—ensures that visualizations maintain clarity and focus attention on biologically significant patterns [5].

For multiscale systems biology, hierarchical visualizations such as network diagrams and dendrograms effectively represent the nested relationships spanning molecular interactions, cellular communication, and tissue organization [4]. These approaches enable researchers to maintain context while navigating between scales of biological organization. Similarly, map-based plots and spatial analyses provide critical insights into how geographical organization influences biological function across scales [4]. When designing visualizations for scientific communication, adherence to accessibility standards—particularly maintaining minimum contrast ratios of 4.5:1 for standard text and 3:1 for large text (18pt or 14pt bold)—ensures that information remains interpretable by all researchers, including those with visual impairments [6] [7] [8]. Strategic color selection that incorporates both perceptual uniformity and semantic meaning further enhances the communicative power of biological data visualizations.

Table: Data Visualization Selection Guide for Biological Data Analysis

| Analytical Question | Recommended Visualization | Biological Application Example | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trends over time | Line Graph [4] | Gene expression dynamics, Metabolic flux changes | Use continuous time intervals; Limit to 3-4 categories for clarity [5] |

| Category comparison | Bar/Column Chart [4] | Protein expression across cell types, Drug response variations | Order categories meaningfully; Use consistent color encoding [3] |

| Part-to-whole relationships | Pie Chart [4] | Cell type proportions, Metabolic pathway contributions | Limit to 5-7 segments; Use contrasting colors meeting 3:1 ratio [8] |

| Correlation analysis | Scatter Plot [4] | Gene-gene expression relationships, Dose-response curves | Include trend lines; Use size/color for additional variables [3] |

| Multivariate patterns | Heat Map [4] | Omics data integration, Spatial transcriptomics | Use perceptually uniform colormaps; Cluster similar elements [5] |

Experimental Methodologies and Research Workflows

The integration of computational modeling with experimental validation represents a cornerstone of modern systems biology research. This iterative cycle begins with hypothesis generation through computational simulations, proceeds to targeted experimental intervention, and culminates in model refinement based on empirical observations. For molecular-scale investigations, multi-omics data collection provides the quantitative foundation for constructing data-driven models of cellular processes [1]. These approaches generate massive datasets that require sophisticated probabilistic methods, including Bayesian inference, to distinguish meaningful biological signals from experimental noise and build robust predictive models [1]. At the cellular level, high-content imaging and single-cell technologies enable the quantification of spatial relationships and heterogeneous cell behaviors that inform agent-based models of multicellular systems [2].

For tissue and organ-level investigations, biological fluid dynamics and biomechanical analyses provide critical insights into the physical constraints shaping system behavior [1]. These methodologies often incorporate finite element modeling and computational fluid dynamics to simulate physiological processes across scales—from blood flow through vascular networks to mechanical forces in musculoskeletal systems. The emerging paradigm of synthetic biology further extends these approaches through the deliberate design of biological circuits that test our understanding of natural systems [1]. By engineering controlled perturbations and observing system responses, researchers can validate computational predictions and refine theoretical models of cellular regulation. Throughout these investigations, maintaining detailed experimental protocols and standardized reagent specifications ensures the reproducibility and cross-laboratory validation essential for advancing systems biology research.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The experimental investigation of biological systems across scales requires carefully selected research reagents and computational tools that enable precise measurement and manipulation of biological processes. These resources form the foundational toolkit for generating quantitative data that feeds into mathematical models and validates computational predictions. The following table summarizes essential research solutions for multi-scale systems biology investigations, spanning molecular, cellular, and organ-level analyses.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Scale Systems Biology

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Scale | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Omics Measurement Kits | Comprehensive profiling of molecular components (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [1] | Molecular to Cellular | Enables data collection for network analysis; Requires integration algorithms for cross-platform data [1] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Reagents | Preservation of geographical information in gene expression measurements [2] | Cellular to Tissue | Critical for validating spatial models; Provides positional context for cellular states [2] |

| Live-Cell Imaging Dyes | Dynamic tracking of cellular processes and interactions without fixation [2] | Cellular | Enables quantitative measurement of cell behaviors for agent-based models [2] |

| Mathematical Modeling Software | Implementation of deterministic/stochastic simulations and numerical analysis [1] | All Scales | Supports dynamical systems analysis, Bayesian inference, and multi-scale integration [1] |

| Biological Circuit Components | Engineered genetic elements for synthetic biology approaches [1] | Molecular to Cellular | Tests network motifs and control principles through deliberate design [1] |

| Biomechanical Testing Systems | Quantification of physical properties and fluid-structure interactions [1] | Tissue to Organ | Provides parameters for mechanical models; Measures emergent tissue properties [1] |

The field of systems biology is rapidly advancing toward increasingly integrative multi-scale frameworks that seamlessly connect molecular mechanisms to physiological outcomes. This progression is enabled by continuous improvements in mathematical methodologies, including more sophisticated approaches for managing complexity across biological scales and extracting meaningful insights from high-dimensional data [1]. Future advancements will likely focus on developing more accessible modeling platforms that implement human-interpretable grammars for describing biological rules, thereby democratizing computational modeling and expanding participation in virtual cell laboratory research [2]. These platforms will need to balance mathematical rigor with practical usability, enabling experimental biologists to directly engage with computational approaches without requiring extensive specialized training.

Emerging opportunities in the field include the development of more comprehensive standards for data and model sharing that facilitate collaboration and reproducibility across research communities. Additionally, the integration of machine learning approaches with mechanistic modeling promises to enhance both predictive accuracy and biological insight, particularly for complex systems where first-principles understanding remains incomplete. As these methodologies mature, researchers will be increasingly equipped to tackle fundamental questions in cell organization and develop more effective therapeutic strategies through systems-level understanding of disease mechanisms. The continued refinement of multi-scale modeling approaches—from molecular to organ-level systems—will undoubtedly play a central role in advancing our understanding of biological complexity and harnessing this knowledge for practical applications in medicine and biotechnology.

Mathematical modeling serves as a foundational tool in systems biology, enabling researchers to decipher the complex mechanisms that govern cellular organization and function. The drive to understand how biological systems—from individual cells to entire tissues—maintain their structure and behavior over time has led to the development of a diverse array of computational frameworks. These models can be broadly categorized based on how they represent state changes and time, with deterministic and stochastic approaches forming the primary dichotomy. Deterministic models, which ignore randomness, predict a single outcome for a given set of initial conditions, while stochastic models explicitly incorporate randomness to capture the inherent noise and variability in biological systems [9]. Furthermore, models can be classified as continuous or discrete based on how they represent the state of the system, such as representing gene expression with continuous concentrations or discrete ON/OFF states [9]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of these core mathematical constructs, framing them within the ongoing research to understand the principles of cell and tissue organization.

Deterministic Frameworks

Deterministic models operate on the principle that the future state of a system is entirely determined by its current state and the rules governing its evolution, with no room for randomness. These models are powerful for systems where the behavior of a large number of molecules averages out to a predictable trajectory.

Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) and the Law of Mass Action

The most prevalent deterministic framework in systems biology involves ODEs based on the law of mass action. This law states that the rate of a chemical reaction is proportional to the product of the concentrations of the reactants [10]. For a system with ( M ) chemical species and ( R ) reactions, the change in concentration ( ci ) of the ( i )-th species is given by: [ \dot{c}i = \sum{j=1}^{R} (a{ij} \cdot kj \cdot \prod{l=1}^{M} cl^{\beta{lj}}) ] Here, ( \dot{c}i ) is the time derivative of the concentration, ( kj ) is the deterministic rate constant for the ( j )-th reaction, ( a{ij} ) is the stoichiometric coefficient, and ( \beta{lj} ) are the exponents determined by the reaction stoichiometry [10]. ODE models are widely used to simulate everything from metabolic pathways to signaling networks, providing a dynamic and quantitative description of spatially homogeneous systems.

A Formal Representation for Biological Networks

The mathematical structure of a reaction network can be formally represented using a stoichiometric matrix ( N ), where rows correspond to chemical species and columns represent reactions. The system's dynamics are then described by: [ \frac{d}{dt}\vec{S} = N \vec{\nu}(\vec{S}, t, N, W, \vec{p}) ] In this equation, ( \vec{S} ) is the vector of species' amounts or concentrations, ( \vec{\nu} ) is the vector of reaction velocities, ( W ) is a modulation matrix representing regulatory influences, and ( \vec{p} ) is a parameter vector of rate constants [11]. This formal representation underpins the interpretation of community-standard model description formats like the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML).

Boolean Networks as a Discrete Deterministic Framework

For systems where precise quantitative data is scarce or where a coarse-grained understanding is sufficient, Boolean networks offer a discrete deterministic alternative. In a Boolean network, each gene or protein is represented by a binary node (( xi \in {0, 1} )), which is either "ON" (expressed/active) or "OFF" (not expressed/inactive). The state of a node at the next time step is determined by a Boolean logic function ( fi ) that takes the current states of its regulatory inputs [9]: [ xi(t+1) = fi(x{j1}(t), x{j2}(t), \dots, x{jki}(t)) ] The dynamics of the entire network are determined by the synchronous update of all nodes according to their respective functions. A key focus of analysis is the identification of attractors—stable state cycles—which are often interpreted as distinct cellular states, such as proliferation, apoptosis, or differentiation [9]. This framework simplifies complex biochemical kinetics into logical rules, capturing the essential topology and logic of a regulatory network.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Deterministic Modeling Approaches

| Feature | ODE Models (Continuous) | Boolean Networks (Discrete) |

|---|---|---|

| State Representation | Continuous concentrations | Discrete (0 or 1) node states |

| Dynamics | Defined by differential equations | Defined by logical update functions |

| Typical Analysis | Stability analysis, parameter sweeps | Attractor analysis, state transition mapping |

| Primary Justification | Law of mass action, large molecule numbers | Switch-like behavior in gene regulation |

| Ideal Use Case | Systems with abundant quantitative data | Large, qualitative networks where focus is on topology and logic |

Stochastic Frameworks

Stochastic models are essential for capturing the random fluctuations inherent in biological systems, particularly when molecule counts are low. This randomness can lead to behaviors that are impossible to predict with deterministic models.

The Chemical Master Equation (CME)

The Chemical Master Equation (CME) is a cornerstone of stochastic modeling for biochemical systems. It describes the temporal evolution of the probability distribution over all possible states of the system. The state is defined by a vector ( \vec{n} = (n1, ..., nM) ) of molecular counts. The CME is formulated as: [ \dot{p}{\vec{n}}(t) = \sum{j=1}^{R} [wj(\vec{n} - \vec{A}j) p{\vec{n} - \vec{A}j}(t) - wj(\vec{n}) p{\vec{n}}(t)] ] Here, ( p{\vec{n}}(t) ) is the probability of being in state ( \vec{n} ) at time ( t ), ( wj(\vec{n}) ) is the propensity of the ( j )-th reaction (the probability per infinitesimal time unit for the reaction to occur), and ( \vec{A}j ) is the stoichiometric vector for the reaction, describing the change in state when the reaction fires [10]. The propensity is typically ( wj(\vec{n}) = \kappaj \cdot \prod{i=1}^{M} \binom{ni}{\beta{ij}} ), where ( \kappa_j ) is the stochastic reaction constant [10].

Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs)

Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs) represent a continuous stochastic framework, often conceived as ODEs with an added noise term. They are useful for modeling systems where a continuous approximation is still valid, but intrinsic or extrinsic noise cannot be neglected. A simple SDE might take the form: [ dx = \mu(x, t)dt + \sigma(x, t)dWt ] where ( \mu(x, t) ) is the deterministic drift term, ( \sigma(x, t) ) is the stochastic diffusion term, and ( dWt ) represents a Wiener process (Brownian motion) that introduces random noise [9].

Probabilistic Boolean Networks (PBNs)

Probabilistic Boolean Networks (PBNs) are a stochastic generalization of Boolean networks. In a PBN, instead of a single Boolean function, each node has a set of possible Boolean functions, each chosen according to a fixed probability distribution at each time step [9]. This framework incorporates uncertainty into the network structure and can model asynchronous updating, allowing for a more flexible and realistic representation of biological regulation where the exact mechanism of interaction may not be known with certainty.

Comparative Analysis: Dynamics and Outcomes

The choice between deterministic and stochastic modeling frameworks can lead to significantly different interpretations of the same biological system.

Bistability vs. Bimodality

In deterministic ODE models, bistability is a property where, for a given set of parameters, the system has two stable fixed points separated by an unstable fixed point. The system will evolve toward one of the two stable states depending on its initial conditions. In stochastic CME-based models, the analogous concept is bimodality, where the stationary probability distribution ( p_{\vec{n}} ) has two distinct peaks (modes). These modes often correspond to the stable fixed points in the deterministic model, but this is not always the case [10]. Discrepancies can arise, especially in systems with low molecule numbers and nonlinear reactions. It is possible for a deterministic model to be bistable while its stochastic counterpart is unimodal, and vice versa. This challenges the straightforward mapping of deterministic stability concepts to stochastic settings, particularly in cellular signaling and regulation where component copy numbers are low [10].

First-Passage Time (FPT) and Cellular Event Timing

Many cellular events, such as cell cycle transitions or the initiation of apoptosis, are triggered when a key molecular species crosses a critical threshold. The time for this to occur is a random variable, and its analysis highlights a key difference between modeling frameworks.

- Deterministic Prediction: The time to reach a threshold is a single value found by numerically integrating the ODEs.

- Stochastic Prediction: The First-Passage Time (FPT) is stochastic. The mean FPT (( \mathbb{E}[\tau] )) is the average time for the threshold to be crossed, but individual cellular events will show variability around this mean [12].

For a continuous-time Markov process ( x(t) ), the FPT to a subset of states ( Y ) starting from state ( n ) is defined as: [ \tau_n = \inf { t \ge 0 : x(t) \in Y | x(0) = n } ] Deterministic predictions can be highly inaccurate when molecule numbers are within the range typical for many cells. Molecular noise can significantly shift mean first-passage times, either accelerating or delaying cellular events compared to deterministic predictions, a phenomenon particularly pronounced within auto-regulatory genetic feedback circuits [12].

Table 2: Comparison of Deterministic and Stochastic Predictions for a Simple Gene Expression Model

| Model Characteristic | Deterministic ODE Model | Stochastic CME Model |

|---|---|---|

| Molecule Number Representation | Continuous concentration | Discrete integer counts |

| Dynamic Output | Smooth, predictable trajectory | Noisy, variable trajectory |

| Steady-State Solution | Single, fixed concentration value | Probability distribution over all possible molecule counts |

| Prediction for Event Timing | Single, precise time value | Distribution of times (FPT distribution) |

| Prediction for System with Two Stable States | Bistability: final state depends on initial conditions | Bimodality: probability distribution with two peaks; possible spontaneous switching |

A Case Study in Multiscale Modeling: Auxin Transport in Plants

A comparative study on modeling the transport of the hormone auxin through a file of plant cells illustrates the distinct insights provided by different modeling frameworks [13]. The biological system involves auxin moving through a line of cells with cytoplasm and apoplast compartments, driven by passive diffusion of protonated auxin and active, carrier-mediated transport of anionic auxin.

Model Formulations

- Stochastic Computational Model: The study used a multi-compartment stochastic P system framework. Individual auxin molecules were modeled as objects moving between compartments (e.g., cytoplasm, apoplast) according to a set of rules with associated stochastic reaction constants. The model was executed using a multi-compartment Monte Carlo stochastic algorithm, which naturally provides information on system variability [13].

- Deterministic Mathematical Model: The same system was described by a system of coupled Ordinary Differential Equations based on mass action kinetics and Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz theory for transmembrane fluxes. The ODEs tracked the concentration of auxin in each compartment over time [13].

- Analytical Solution: Asymptotic methods were applied to derive approximate analytical solutions for the concentrations and transport speeds, providing straightforward mathematical expressions [13].

Insights from the Comparative Approach

The study found that while all three approaches generally predicted the same overall behavior, each provided unique information [13]:

- The analytical approach offered immediate insight into the functional dependencies of concentrations and transport speeds.

- The deterministic numerical simulations provided a standard, computationally efficient way to study the system's behavior.

- The stochastic simulations were crucial for understanding the variability and noise in the system, which is inherently a discrete, molecular-scale process.

This case demonstrates that the choice of modeling approach should be guided by the specific biological questions being addressed. An integrative, hybrid approach can yield the most comprehensive understanding.

Protocols for Model Implementation and Simulation

Implementing and simulating mathematical models requires careful setup and execution. The following protocols outline general methodologies.

Protocol for Deterministic ODE Simulation with SBML

This protocol uses standard software libraries to simulate a model described in SBML.

- Model Initialization: Load the SBML file using a library like JSBML or libSBML. Set all species, parameters, and compartments to their initial values as defined in the model.

- Equation Construction: Interpret the model's reactions, rules (rate, assignment, algebraic), and events to construct the full system of equations. This involves building a directed acyclic syntax graph that merges the abstract syntax trees of all model components [11].

- Preprocessing: Convert algebraic rules into assignment rules using techniques like bipartite matching if possible. This step may require symbolic computation. Process events and assignment rules to be integrated into the numerical solution.

- Numerical Integration: Pass the derived system of ODEs to a numerical solver (e.g., an explicit Runge-Kutta method for non-stiff problems or a backward differentiation formula (BDF) method for stiff problems). The solver computes the species concentrations over the desired time course.

- Output and Analysis: The solver returns a time series of concentration values. These can be analyzed for steady states, bistability, or other dynamic features.

Protocol for Stochastic Simulation using the Gillespie Algorithm

The Gillespie Algorithm (or SSA) provides exact trajectories for the Chemical Master Equation.

- Initialization: Specify the initial molecular counts of all species ( \vec{n}(0) ), the reaction channels, and their corresponding stochastic reaction constants ( \kappaj ) and stoichiometric vectors ( \vec{A}j ).

- Propensity Calculation: Calculate the propensity function ( aj(\vec{n}(t)) ) for each reaction channel ( j ) in the current state ( \vec{n}(t) ). The sum of all propensities is ( a0 = \sum{j=1}^{R} aj ).

- Monte Carlo Step: Generate two random numbers ( r1 ) and ( r2 ) from a uniform distribution over (0, 1).

- Determine Time to Next Reaction: The time interval ( \tau ) until the next reaction occurs is given by ( \tau = (1/a0) \ln(1/r1) ).

- Determine Which Reaction Fires: Find the reaction index ( \mu ) such that ( \sum{j=1}^{\mu-1} aj < r2 a0 \le \sum{j=1}^{\mu} aj ).

- Update State and Time: Update the system state: ( \vec{n}(t + \tau) = \vec{n}(t) + \vec{A}_\mu ). Update the time: ( t = t + \tau ).

- Iterate: Return to Step 2 until a desired termination condition is met (e.g., a final simulation time is reached). The output is a single stochastic trajectory. To get statistics on mean behavior or FPTs, many independent runs must be performed and averaged.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mathematical Modeling in Systems Biology

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) | Model Encoding Format | A standardized, machine-readable XML format for representing computational models of biological processes. Enables model sharing, reuse, and software interoperability [11]. |

| BioModels Database | Model Repository | A curated, peer-reviewed database of published mathematical models of biological systems, many encoded in SBML. Provides a source of validated models for simulation and analysis [11]. |

| Systems Biology Simulation Core Library | Simulation Software | A Java-based library providing efficient simulation algorithms for SBML models. It includes multiple ODE solvers and is designed for integration into third-party software [11]. |

| Gillespie Algorithm (SSA) | Simulation Algorithm | An exact stochastic simulation algorithm for generating trajectories of the Chemical Master Equation. Essential for studying systems with low copy numbers and intrinsic noise [10]. |

| Infobiotics Workbench | Software Suite | A platform for designing, simulating, and analyzing multiscale executable models, including support for stochastic P systems and spatial simulations [13]. |

Visualizing Model Structures and Relationships

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the logical relationships between different modeling frameworks and a specific biological network structure.

Model Framework Relationships

Auxin Transport Model Workflow

The quest to understand the rules governing cellular organization, exemplified by recent research identifying five core rules for tissue maintenance in the colon [14] [15], relies heavily on a diverse and powerful set of mathematical constructs. Deterministic, stochastic, and discrete methods each provide a unique and complementary lens through which to view biological systems. The choice of framework is not merely a technicality; it fundamentally shapes the questions that can be asked and the phenomena that can be observed, from the predictable flow of metabolites in a large population to the random, decisive moment a single cell triggers apoptosis. As modeling efforts advance, the integration of these frameworks into hybrid multiscale models, coupled with rigorous computational tools and standards, promises to unlock deeper insights into the hidden blueprints of life. This progression aligns with initiatives like the National Science Foundation's "Rules of Life," pushing toward a more predictive and mechanistic understanding of biology [14].

The Role of Differential Equations in Modeling Dynamic Biological Processes

Mathematical modeling has become a cornerstone of modern systems biology, providing a powerful framework for understanding the complex, dynamic interactions within biological systems. Differential equations, in particular, serve as the fundamental mathematical language for describing how biological quantities evolve over time and space. These equations enable researchers to move beyond intuitive reasoning and capture the nonlinear dynamics inherent in cellular processes, from metabolic pathways to signaling networks. The core strength of differential equation models lies in their ability to integrate prior biological knowledge with experimental data, creating in silico environments where hypotheses can be tested thousands of times faster than with traditional wet-lab experiments [16] [17].

In the context of understanding cell organization—a central theme in systems biology—differential equations provide the necessary formalism to simulate everything from intracellular processes to multi-cellular interactions. Models based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs) typically represent well-mixed systems where spatial heterogeneity can be neglected, while partial differential equations (PDEs) capture phenomena where spatial gradients and diffusion processes play critical roles [16] [18]. The integration of these mathematical approaches with experimental biology has created a powerful paradigm for unraveling the astonishing complexity and diversity of biological phenomena, for which fundamental laws often remain elusive [16].

Core Mathematical Frameworks for Biological Modeling

Fundamental Equation Types and Their Applications

The selection of an appropriate mathematical framework is crucial for effectively modeling biological systems. The table below summarizes the primary types of differential equations used in biological modeling and their characteristic applications:

Table 1: Types of Differential Equations and Their Biological Applications

| Equation Type | Key Characteristics | Typical Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) | Describe changes over time in well-mixed systems; Assume spatial homogeneity | Metabolic pathways [19], Population dynamics [20], Enzyme kinetics [16] |

| Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) | Capture spatiotemporal dynamics; Incorporate diffusion and spatial gradients | Pattern formation [17], Morphogenesis [17], Tumor growth [21], Spatial ecology |

| Stochastic Differential Equations | Incorporate random fluctuations; Account for discrete events | Gene expression [17], Biochemical signaling in low-copy number conditions [16] |

| Delay Differential Equations | Incorporate time delays; Represent maturation or processing periods | Immune response dynamics [22], Cell cycle regulation [21] |

| Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) | Combine mechanistic models with neural networks; Hybrid approach | Systems with partially unknown dynamics [19], Complex signaling networks |

The distinction between deterministic and stochastic approaches represents a critical modeling decision. Deterministic models, described by ODEs or PDEs, assume that system dynamics are entirely predictable given exact knowledge of initial conditions and parameters. These are particularly suitable for systems with large molecular populations where random fluctuations average out. In contrast, stochastic models explicitly account for random effects, making them essential for systems where molecular copy numbers are low and random fluctuations significantly impact system behavior [16].

Mathematical Formulations of Biological Principles

Biological differential equations typically encode fundamental physicochemical principles into their mathematical structure. The Mass Action Law, which states that "the number of interactions between two particles depends on the concentration of both," frequently serves as the foundation for modeling biochemical reactions [23]. This principle translates mathematically into reaction rates that are proportional to the product of reactant concentrations.

For enzymatic processes, Michaelis-Menten kinetics offers a more sophisticated formulation that accounts for enzyme saturation effects. A typical ODE implementation would take the form:

d[P]/dt = (V_max * [S]) / (K_m + [S])

where [P] represents product concentration, [S] substrate concentration, V_max the maximum reaction rate, and K_m the Michaelis constant [16].

Spatial models frequently incorporate diffusion processes using PDE formulations based on Fick's laws. A simple diffusion equation for a chemical species with concentration u takes the form:

∂u/∂t = D * ∇²u

where D is the diffusion coefficient and ∇² represents the Laplace operator [18]. Such formulations become essential when modeling processes like morphogen gradient formation, cellular patterning, and tissue development.

Workflow for Developing Biological Models with Differential Equations

A Systematic Approach to Model Development

The process of constructing mathematical models of biological systems follows a structured workflow that ensures biological relevance and mathematical rigor. The following diagram illustrates the key stages in this iterative process:

Diagram 1: Model Development Workflow

Understanding the Biological System

The initial phase involves developing a comprehensive understanding of the biological system to be modeled. While a complete understanding may be the ultimate goal of the modeling effort, a foundational knowledge is essential for defining the scope, identifying key components, and determining available data for calibration and validation. For example, in modeling phosphoinositide turnover kinetics, researchers first assembled available data on known components involved in PIP2 hydrolysis, including essential enzymes, substrates, and products, while also performing dedicated experiments to determine basal levels and kinetic changes following stimulation [16].

Creating a Graphical Scheme and Selecting Mathematical Framework

The biological knowledge is subsequently translated into a graphical scheme that visually represents key players (e.g., proteins, metabolites) and their interactions through arrows indicating biochemical reactions or regulatory relationships. This graphical representation serves as an intermediate step between biological understanding and mathematical formalization, clarifying which elements are included and which are deliberately excluded from the model [16].

The conversion from graphical scheme to mathematical model requires selecting appropriate mathematical approximations, including decisions about model scale (molecular, cellular, tissue), dynamics (static vs. dynamic), stochasticity (deterministic vs. stochastic), spatial resolution (spatially distributed vs. homogeneous), and system boundaries (open vs. closed) [16]. These decisions are guided by the specific biological questions being addressed and available computational resources.

Defining Model Components and Implementation

With the mathematical framework established, model components must be precisely defined, including:

- Variables: Biological "species" of interest (e.g., proteins, metabolites)

- Compartments: Defined volumes with specific surface-to-volume ratios

- Parameters: Fixed numerical constants (e.g., rate constants, diffusion coefficients)

- Processes: Mathematical descriptions of interactions (e.g., mass action, Michaelis-Menten) [16]

Parameter values are determined through optimization algorithms that fit models to experimental data, with approaches ranging from genetic algorithms to particle swarm optimization [16]. For spatial models, the compartmental structure must be mapped to appropriate geometries where displacement mechanisms like diffusion can be defined.

Implementation typically involves formulating the corresponding set of equations and converting them into computer code for numerical solution. While experienced modelers may code directly in languages like Python or MATLAB, software platforms like VCell automatically convert biological descriptions into mathematical systems, reducing scripting errors [16].

Parameter Estimation and Model Validation Techniques

Parameter estimation represents a significant challenge in biological modeling, particularly when dealing with limited experimental data. The parameter interdependence in complex models necessitates rigorous estimation techniques. For stochastic discrete models of biochemical networks, methods utilizing finite-difference approximations of parameter sensitivities and singular value decomposition of the sensitivity matrix have shown promise [17].

Validation frameworks like VeVaPy (a Python library for verification and validation) help determine which mathematical models from literature best fit new experimental data. These tools run parameter optimization algorithms on multiple models against datasets and rank models based on cost function values, significantly reducing the effort required for model validation [17].

Advanced Methodologies: Universal Differential Equations

Hybrid Modeling Approach

Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) represent an advanced modeling framework that combines mechanistic differential equations with data-driven artificial neural networks. This hybrid approach leverages prior knowledge through the mechanistic components while using neural networks to model unknown or overly complex processes that are difficult to specify explicitly. UDEs are particularly valuable in systems biology where datasets are often limited and model interpretability is crucial for medical applications [19].

The UDE framework addresses several domain-specific challenges:

- Handling parameters that span orders of magnitude through log-transformation

- Managing stiff dynamics common in biological systems via specialized numerical solvers

- Accounting for complex measurement noise distributions using appropriate error models

- Balancing contributions of mechanistic and neural network components through regularization [19]

Table 2: Components of Universal Differential Equations

| Component | Function | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Terms | Encode known biological mechanisms | High - Parameters have biological meaning |

| Neural Network Terms | Learn unknown processes from data | Low - Function as black boxes |

| Hybrid Structure | Combines strengths of both approaches | Medium - Balance depends on regularization |

UDE Architecture and Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the architecture of a Universal Differential Equation and the training pipeline:

Diagram 2: UDE Architecture and Training

The UDE training pipeline carefully distinguishes between mechanistic parameters (θM), which are critical for biological interpretability, and neural network parameters (θANN), which model poorly understood components. To maintain interpretability of mechanistic parameters, the pipeline incorporates likelihood functions, constraints, priors, and regularization. Weight decay regularization applied to ANN parameters adds an L2 penalty term λ‖θ_ANN‖₂² to the loss function, where λ controls regularization strength, preventing the neural network from becoming overly complex and overshadowing the mechanistic components [19].

The pipeline employs a multi-start optimization strategy that samples initial values for both UDE parameters and hyperparameters (ANN size, activation function, learning rate) to improve exploration of the parameter space. Advanced numerical solvers like Tsit5 and KenCarp4 within the SciML framework enable handling of stiff dynamics common in biological systems [19].

Essential Research Tools and Software

Computational Platforms for Biological Modeling

The implementation and simulation of differential equation models in biology is supported by numerous software platforms that cater to different levels of modeling expertise. The table below compares key tools used in the field:

Table 3: Software Tools for Biological Modeling with Differential Equations

| Software Tool | Primary Functionality | Key Features | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| ODE-Designer [23] | Visual construction of ODE models | Node-based editor; Automatic code generation; No programming required | High - Designed for accessibility |

| VCell [16] | Multiscale modeling of cellular biology | Rule-based modeling; Multiple simulation methodologies; Web-based platform | Medium - Steeper learning curve |

| COPASI [16] | Biochemical network simulation | Parameter estimation; Sensitivity analysis; Optimization algorithms | Medium - Requires biology background |

| SciML [19] | Scientific machine learning | UDE support; Advanced solvers; Julia-based framework | Low - Programming expertise needed |

| VeVaPy [17] | Model verification and validation | Python library; Parameter optimization; Model ranking | Medium - Python proficiency required |

Successful implementation of differential equation models in biological research requires both computational tools and experimental resources:

High-Throughput Data Generation Platforms: Technologies like single-cell RNA sequencing and mass cytometry provide quantitative data essential for parameterizing and validating models of cellular processes [22].

Perturbation Tools: Chemical inhibitors, RNA interference systems, and CRISPR-based approaches enable controlled manipulation of biological systems to generate data for testing model predictions [16].

Live-Cell Imaging Systems: Fluorescence microscopy with high spatiotemporal resolution provides quantitative data on protein localization and concentration dynamics, particularly important for spatial models [16].

Parameter Estimation Algorithms: Optimization methods including genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization, simulated annealing, and steepest descent approaches implemented in platforms like COPASI [16].

Sensitivity Analysis Tools: Methods like finite-difference approximations of parameter sensitivities and singular value decomposition of sensitivity matrices to determine parameter identifiability [17].

Application Case Study: Signaling Pathway Modeling

Detailed Experimental Protocol

To illustrate the practical application of differential equations in biological research, we present a detailed protocol for modeling a canonical signaling pathway based on phosphoinositide turnover kinetics [16]:

Step 1: Biological System Characterization

- Assemble known components: Identify all known enzymes, substrates, and products involved in the signaling pathway. For PIP2 hydrolysis, this includes PI, PIP, PIP2, PLC, DAG, and IP3.

- Determine basal levels: Perform experiments to quantify relative amounts and basal levels of key signaling molecules under unstimulated conditions.

- Characterize dynamics: Measure time-dependent changes in signaling molecules following stimulation (e.g., bradykinin-induced changes in PIP2 and PIP in N1E-115 cells).

- Gather kinetic parameters: Collect known kinetic parameters from literature, such as InsP3 production kinetics from previous studies.

Step 2: Model Formulation and Implementation

- Create graphical scheme: Develop a visual representation of the pathway, indicating key players, interactions, and cellular locations.

- Select mathematical framework: Choose ODEs for initial well-mixed approximation, with possible extension to PDEs for spatial analysis.

- Define model components: Specify 13 variables localized to cytosol and plasma membrane compartments with calculated surface-to-volume ratios.

- Implement reaction kinetics: Use mass action kinetics for biochemical reactions, with stimulus modeled as exponential decay.

- Parameterize model: Employ optimization algorithms to determine parameter values that fit experimental data.

Step 3: Model Simulation and Validation

- Numerical solution: Solve the system of differential equations using appropriate numerical solvers (e.g., Tsit5 for non-stiff systems, KenCarp4 for stiff systems).

- Sensitivity analysis: Perform local and global sensitivity analyses to identify parameters with greatest influence on model outputs.

- Validate predictions: Test model predictions against experimental data not used in parameter estimation.

- Iterative refinement: Refine model structure and parameters based on discrepancies between predictions and experimental results.

Workflow for Signaling Pathway Modeling

The following diagram illustrates the specific workflow for applying differential equation modeling to signaling pathways:

Diagram 3: Signaling Pathway Modeling Workflow

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The field of biological modeling with differential equations continues to evolve, with several emerging trends shaping its future. Universal Differential Equations represent a promising direction, addressing the fundamental challenge of modeling systems with partially unknown mechanisms [19]. However, UDEs face challenges in efficient training due to stiff dynamics and noisy data, necessitating continued methodological development.

The integration of multi-scale models that connect molecular-level events to cellular and tissue-level phenomena represents another frontier. Such integration requires novel mathematical approaches to bridge scales efficiently while maintaining computational tractability [22]. Similarly, developing better methods for parameter identifiability analysis remains crucial, particularly for models with many interacting components and limited experimental data [17].

As single-cell technologies generate increasingly detailed spatial and temporal data, differential equation models must adapt to leverage these rich datasets. This will likely involve closer integration between experimental and theoretical approaches, with mathematical models playing a central role in designing critical experiments and interpreting complex datasets. The continued development of accessible software tools will be essential for broadening the adoption of mathematical modeling across biological research communities [23].

In conclusion, differential equations provide an indispensable framework for understanding dynamic biological processes, offering a powerful approach to formalizing biological knowledge, generating testable predictions, and ultimately advancing our understanding of cell organization and function in both health and disease.

The quest to understand how complex spatial patterns emerge from homogeneous tissues represents one of the most fascinating challenges in developmental biology. For decades, Alan Turing's reaction-diffusion theory has provided a dominant theoretical framework for explaining these self-organization phenomena. Proposed in 1952, Turing's mechanism demonstrated how two diffusible substances—conceptualized as an activator and inhibitor—could interact to generate periodic patterns through a process of diffusion-driven instability [24]. This theoretical foundation was later operationalized by Gierer and Meinhardt in 1972 into an intuitive model requiring a short-range activator and a long-range inhibitor with differential diffusivity, creating a combination of local positive feedback and long-range negative feedback [24] [25]. For years, this "activator-inhibitor" paradigm, with its strict requirement for differential diffusion, served as the primary lens through which biologists attempted to explain patterning events in development, from digit formation to skin appendage patterning [25].

However, this elegant theoretical framework has faced a significant challenge: the stark discrepancy between the ubiquity of biological patterns and the scarcity of experimentally verified activator-inhibitor systems [24]. This paradox has driven a fundamental re-evaluation of Turing's original principles, leading to the emergence of more sophisticated models that integrate reaction-diffusion dynamics with complex gene regulatory networks. Modern mathematical biology has revealed that realistic biological systems, which incorporate cell-autonomous factors and multi-component interactions, can generate patterns under conditions far broader than classical Turing models permitted [17] [25]. This historical progression—from simple two-component systems to integrated network models—represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of self-organization in biological systems.

The Evolution of Turing's Theory: Beyond Classical Constraints

Limitations of the Classical Turing Framework

The classical Turing model, while mathematically elegant, has proven insufficient to explain the complexity of biological pattern formation. Several fundamental limitations have emerged:

- Experimental Scarcity: Despite decades of research, very few pattern-enabling molecular systems conforming to the activator-inhibitor framework have been experimentally identified and verified [24]

- Over-simplified Representations: Biological regulation often involves post-translational modifications, complex formation, and non-diffusible components that cannot be adequately captured by simple two-component models [24]

- Rigid Diffusivity Requirements: The classical model mandates differential diffusion rates between activator and inhibitor, a condition that may not always be met in biological systems [25]

These limitations prompted researchers to explore whether more complex biochemical networks, without apparent feedback loops or assigned activator/inhibitor identities, could generate Turing patterns. Systematic studies of elementary biochemical networks revealed that Turing patterns can indeed arise from widespread binding-based reactions without explicit feedback loops [24]. Surprisingly, research has demonstrated that ten simple reaction networks are capable of generating Turing patterns, with the simplest requiring only trimer formation via sequential binding and altered degradation rate constants of monomers upon binding [24].

Expansion to Multi-Component Networks

The incorporation of cell-autonomous, non-diffusible components has fundamentally altered our understanding of Turing network requirements. When models include immobile elements such as receptors, intracellular signaling components, or transcription factors, the strict diffusivity constraints of classical models no longer apply [25]. High-throughput mathematical analysis has revealed that these expanded networks fall into three distinct categories:

Table 1: Classification of Turing Networks Based on Diffusivity Requirements

| Network Type | Diffusivity Requirement | Proportion of Networks | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Differential diffusivity required | ~30% | Classical Turing systems; require short-range activation and long-range inhibition |

| Type II | Equal diffusivity allowed | Significant portion of remaining 70% | Can form patterns with equally diffusing signals due to network topology |

| Type III | Unconstrained diffusivity | Significant portion of remaining 70% | Can form patterns with any combination of diffusion coefficients |

This classification system emerged from comprehensive computational screens of minimal three-node and four-node reaction-diffusion networks, revealing that approximately 70% of realistic biological networks do not require differential diffusivity to form spatial patterns [25]. This fundamental insight dramatically expands the potential repertoire of biological systems capable of Turing-type patterning beyond the constraints of classical models.

Integrated Gene Network Models: Combining GRNs with Reaction-Diffusion

The Synthesis of Physical-Chemical and Genomic Principles

Contemporary models have transcended the either-or dichotomy between physical-chemical and genome-based pattern formation approaches. Historical analysis reveals that the most successful explanations of morphogenesis combine gene regulatory networks with physical-chemical processes [17]. This integration acknowledges that while genes provide the components and initial conditions, physical-chemical principles govern the emergent self-organization. As Deichmann (2023) concludes, "Turing's models alone are not able to rigorously explain pattern generation in morphogenesis, but that mathematical models combining physical-chemical principles with gene regulatory networks, which govern embryological development, are the most successful in explaining pattern formation in organisms" [17].

This synthetic approach recognizes that pattern formation operates across multiple scales: gene regulatory networks determine the cast of molecular players and their interaction rules, while reaction-diffusion dynamics translate these local interactions into global spatial patterns. The resulting models can account for both the robustness and plasticity observed in developmental systems, explaining how consistent patterns emerge despite environmental fluctuations and genetic variation.

Computational Frameworks for Pattern Formation Analysis

The theoretical advances in understanding pattern formation have been accompanied by the development of sophisticated computational tools that enable researchers to navigate the complexity of integrated models:

Table 2: Computational Tools for Analyzing Pattern Formation Networks

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDNets | Automated analysis of reaction-diffusion networks | Identifies pattern-forming conditions for 3-node and 4-node networks; classifies diffusivity requirements | Theoretical studies; synthetic circuit design [25] |

| VeVaPy | Verification and validation of mathematical models | Python library; ranks models based on fit to experimental data | Model selection and parameter optimization [17] |

| VCell | Computational biology platform | Abstracts biological mechanisms into mathematical descriptions; solves resulting equations | Spatial modeling of cellular processes [16] |

| COPASI | Biochemical network simulation | Parameter estimation; optimization algorithms; sensitivity analysis | Non-spatial modeling of biochemical networks [16] |

These computational resources have democratized access to sophisticated mathematical analysis, enabling biologists to explore network behaviors without requiring deep expertise in nonlinear dynamics. The RDNets platform, for instance, automates the complex linear stability analysis required to identify pattern-forming conditions, performing six key steps: network construction, selection of strongly connected networks, elimination of symmetric networks, stability analysis without diffusion, instability analysis with diffusion, and derivation of resulting pattern types [25].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Mathematical Modeling Workflow for Pattern Formation

The process of developing and validating mathematical models of pattern formation follows a systematic methodology that integrates biological knowledge with mathematical rigor:

Figure 1: Systematic Workflow for Developing Mathematical Models of Pattern Formation

This workflow begins with developing a fundamental understanding of the biological system to be modeled, including identifying key components and their interactions [16]. The second step involves creating a graphical scheme that simplifies the biology and clarifies the key players, their connections, and spatial localizations [16]. The third critical step requires selecting appropriate mathematical approximations, including decisions regarding model scale (molecular, cellular, tissue), dynamics (static vs. dynamic), stochasticity (deterministic vs. stochastic), spatial resolution (spatially homogeneous vs. distributed), and system boundaries (open vs. closed) [16].

Subsequent steps involve defining model components (variables, parameters, reactions/compartments) and implementing the model using specialized software platforms [16]. Parameter estimation follows, using optimization algorithms to fit model parameters to experimental data [16] [17]. The model then undergoes rigorous validation and verification before being used for computational experiments [17]. Finally, model predictions are compared with biological data, leading to further refinement and new hypothesis generation [16].

High-Throughput Network Screening Protocol

The identification of pattern-forming networks through high-throughput mathematical analysis follows a rigorous computational protocol:

Figure 2: Automated Pipeline for Identifying Pattern-Forming Networks

This protocol begins with the construction of all possible networks of a given size (k), typically focusing on minimal three-node and four-node networks that represent the core components of biological signaling systems [25]. The second step filters these networks to retain only strongly connected networks without isolated nodes or nodes that function solely as read-outs, ensuring biological relevance [25]. The third step eliminates symmetric networks, ensuring that isomorphic networks are considered only once to avoid redundancy in the analysis [25].

The core of the protocol involves stability analysis, first testing whether networks are stable in the absence of diffusion (homogeneous steady state stability), then determining whether they become unstable in the presence of diffusion (diffusion-driven instability) [25]. These steps implement automated linear stability analysis using computer algebra systems to handle the mathematical complexity of multi-node networks [25]. The final step characterizes the types of patterns (in-phase or out-of-phase) that emerge from unstable networks, providing insight into the potential biological relevance of each network topology [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental and computational study of pattern formation networks requires specialized tools and resources:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pattern Formation Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | RDNets | Identification of pattern-forming conditions in reaction-diffusion networks | Web-based; automated linear stability analysis; topology classification [25] |

| VeVaPy (Python library) | Verification and validation of mathematical models against experimental data | Differential evolution parameter optimization; model ranking [17] | |

| VCell | Simulation of spatial biological models | Graphical interface; automatic conversion to mathematical equations [16] | |

| COPASI | Analysis of biochemical networks | Parameter estimation; optimization algorithms; sensitivity analysis [16] | |

| Mathematical Techniques | Linear Stability Analysis | Determination of pattern-forming conditions | Identifies diffusion-driven instabilities [25] |

| Mass-Action Kinetics | Modeling of biochemical reactions | Describes complex formation and post-translational regulations [24] | |

| Ordinary/Partial Differential Equations | Dynamic modeling of biological processes | ODEs for temporal dynamics; PDEs for spatiotemporal dynamics [16] | |

| Experimental Approaches | High-Throughput Screening | Identification of pattern-forming networks | Computational analysis of millions of network topologies [25] |

| Parameter Estimation | Constraining models with experimental data | Optimization algorithms fitting models to biological data [16] [17] |

These tools collectively enable researchers to navigate the complex landscape of potential patterning networks, bridging the gap between theoretical possibilities and biological reality. The computational resources are particularly valuable for constraining candidate topologies with both qualitative and quantitative experimental data, making them practical tools for researchers studying specific developmental patterning systems [25].

The historical progression from Turing's classical reaction-diffusion model to integrated gene network models represents a fundamental shift in how biologists understand self-organization in developing systems. This evolution has expanded the potential mechanisms underlying pattern formation from a narrow set of activator-inhibitor systems with strict diffusivity requirements to a broad class of networks that can operate under diverse conditions, including equal diffusion rates and incorporating non-diffusible components [24] [25]. The integration of gene regulatory networks with reaction-diffusion principles has been particularly fruitful, generating models that successfully explain patterning in complex biological contexts from embryonic axis specification to digit patterning [17] [25].

Future research in this field will likely focus on several key areas: developing more sophisticated computational tools that can handle increasingly complex networks, improving parameter estimation methods for spatial models, and creating more effective strategies for validating model predictions against experimental data. Additionally, the application of these theoretical insights to synthetic biology—engineering synthetic circuits with spatial patterning capabilities—represents an exciting frontier with significant potential for regenerative medicine and tissue engineering [25]. As these developments unfold, the integration of mathematical modeling with experimental biology will continue to illuminate the fundamental principles governing how complexity emerges from simplicity in living systems.

The emergence of biological form and function, from the precise arrangement of a developing embryo to the coordinated response of cells to external cues, represents one of the most fundamental phenomena in biology. Understanding the principles governing pattern formation and signal transduction is crucial for advancing our knowledge of development, homeostasis, and disease. Within the framework of systems biology, mathematical modeling has become an indispensable tool for deciphering these complex processes, moving beyond intuitive reasoning to provide rigorous, predictive frameworks that can be tested experimentally [17]. This whitepaper examines core biological questions in pattern formation and signal transduction, highlighting how mathematical and computational approaches are revolutionizing our understanding of these systems for research and therapeutic development.

The integration of mathematical modeling with experimental biology allows researchers to simulate complex biological systems and reveal insights that might not be apparent through empirical methods alone [17]. For pattern formation, this involves modeling how spatial patterns emerge during development, while for signal transduction, the focus is on quantifying how cells process environmental information. Together, these approaches provide a comprehensive view of how biological systems organize themselves across multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Mathematical Frameworks for Pattern Formation

From Metaphor to Mathematical Rigor

The conceptual foundation for understanding pattern formation in development was significantly shaped by Waddington's epigenetic landscape, a metaphorical representation where a cell's path down a valley represents its progression toward a specific differentiated state [26]. While this metaphor powerfully illustrates concepts of cell fate determination and developmental trajectories, it possesses limitations as a quantitative tool. Modern mathematical frameworks have evolved beyond this metaphor to capture the dynamic, multi-scale nature of pattern formation.

Current approaches recognize that pattern formation involves complex regulatory networks that produce high-dimensional dynamics [26]. The landscape cannot generally be portrayed as a fixed, predetermined manifold because cell fate dynamics are influenced by random processes producing non-deterministic behavior. Instead, mathematical biology now employs more flexible frameworks, including random dynamical systems, which integrate both change and stability while accounting for environmental influences and stochasticity [26]. These frameworks accommodate various mathematical formulations, including ordinary, partial, and stochastic differential equations, providing a more adaptable conceptual and operational foundation for modeling developmental processes.

Mechanistic Models of Morphogenesis

Successful pattern formation models increasingly integrate gene regulatory networks with physical-chemical processes [17]. Alan Turing's reaction-diffusion models, proposed in 1952, demonstrated how spatial patterns could emerge spontaneously from homogeneous starting conditions through the interaction of diffusible morphogens. However, Turing models alone have proven insufficient to rigorously explain pattern generation in morphogenesis [17]. The most successful models combine these physical-chemical principles with gene regulatory networks that govern embryological development, creating multi-scale representations that connect molecular interactions with emergent tissue-level patterning.

For example, in the process of vessel outgrowth (angiogenesis), the mechanical interplay between cells and their extracellular environment guides pattern formation. Endothelial cells at the tips of nascent sprouts exert traction forces on the extracellular matrix (ECM), leading to realignment of ECM fibers along the direction of growing vessels [27]. This aligned ECM then influences the behavior of following cells, creating a positive feedback loop that ensures vessel integrity and guides anastomosis. This process involves coordination across multiple spatial scales, from molecular interactions within focal adhesions to tissue-level deformation of the ECM network.

Table 1: Key Mathematical Frameworks for Modeling Pattern Formation

| Framework Type | Key Features | Biological Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waddington's Landscape | Metaphorical representation; connected topological surface; attractor states [26] | Conceptualizing cell fate decisions; differentiation pathways | Static representation; doesn't consider environmental influences; oversimplified dynamics |

| Reaction-Diffusion Systems | Turing patterns; morphogen gradients; spontaneous symmetry breaking [17] | Embryonic patterning; periodic structures (e.g., limb buds, animal coats) | Limited explanation of complex embryological structures; minimal genetic regulation |

| Random Dynamical Systems | Incorporates stochasticity; time-dependent attractors; flexible mathematical formulation [26] | Cell fate dynamics with environmental noise; long transient dynamics | Mathematical complexity; challenging parameter estimation |

| Multiscale Agent-Based Models | Integrates processes across scales; mechanical force representation; individual cell-ECM interactions [27] | Angiogenesis; cancer invasion; tissue morphogenesis | Computationally intensive; many parameters require estimation |

Quantitative Analysis of Biological Organizations

Recent approaches have introduced information-based methods to quantify geometrical order in biological patterns. These methods employ Shannon entropy to measure the quantity of information in geometrical meshes of biological systems [17]. By applying this approach to biological and non-biological geometric aggregates, researchers can quantify spatial heterogeneity and identify fundamental principles of biological organization. This quantitative framework allows for rigorous comparison of pattern formation across different biological systems and experimental conditions, moving beyond qualitative descriptions to mathematical characterization of biological structures.

Signal Transduction Pathways: From Reception to Response

Fundamental Principles and Components

Signal transduction is the process by which cells convert extracellular signals into specific intracellular responses, enabling cellular communication and adaptation to changing environments [28]. These pathways form the molecular basis for numerous biological processes, including development, immune function, and homeostasis. At their core, signal transduction pathways consist of three basic components: receptors that detect signals, transduction cascades that relay and amplify the message, and effector molecules that execute the cellular response [29].

The process begins when a signaling molecule (ligand) binds to a specific receptor protein, often causing a conformational change that activates its intracellular signaling capabilities [29]. This activation triggers a cascade of intracellular events, frequently involving protein phosphorylation by kinases and the production of second messengers such as cyclic AMP (cAMP) and calcium ions (Ca²⁺) [30]. These cascates amplify the original signal, enabling a small number of extracellular signal molecules to produce a large intracellular response. The pathway culminates in specific cellular changes, which may include alterations in gene expression, metabolism, cell movement, or even programmed cell death.

Diagram 1: Core Signal Transduction Pathway with Amplification. This diagram illustrates the fundamental components and flow of information in a generic signal transduction pathway, highlighting the amplification step where secondary messengers enable signal multiplication.

Key Pathway Examples and Mechanisms

Cells employ diverse signal transduction mechanisms tailored to specific functions and contexts. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent one major class of receptors that initiate intracellular cascades by activating GTP-binding proteins, which in turn regulate enzyme activity and second messenger production [29]. Another important class, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), undergo autophosphorylation upon ligand binding, creating docking sites for intracellular signaling proteins and initiating kinase cascades such as the MAPK pathway [28].

The versatility of cellular responses to signaling is evident across biological systems. In the fight-or-flight response, epinephrine binding to GPCRs in liver cells triggers a cascade leading to glycogen breakdown and glucose release [28]. During immune responses, cytokines binding to receptors activate signaling pathways that turn on genes needed for immune cell proliferation [28]. In developing organisms, HOX genes act as master switches controlled by signal transduction pathways that determine body plans and ensure proper formation of anatomical structures [28].

Table 2: Quantitative Features of Signal Transduction Pathways

| Feature | Mechanism | Quantitative Impact | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Amplification | One receptor activating multiple intracellular mediators; second messenger diffusion [30] | Single receptor can activate 100s of downstream effectors | Enables sensitive response to weak environmental signals |

| Kinase Cascade | Sequential protein phosphorylation by kinases [30] | Each kinase can activate multiple downstream kinases | Exponential signal amplification; integration point for multiple signals |

| Second Messenger Diffusion | Small molecules (cAMP, Ca²⁺) spreading through cytoplasm [30] | Rapid dissemination (microseconds) throughout cell | Coordinated response across large cellular volumes; speed of response |

| Feedback Regulation | Protein phosphatases removing phosphate groups [30] | Precise temporal control of pathway activity | Prevents excessive response; enables adaptation and termination |

Integration with Pattern Formation

Signal transduction pathways play essential roles in pattern formation by interpreting morphogen gradients and translating them into spatial patterns of gene expression and cell differentiation. During embryonic development, signal pathways activate specific transcription factors in different regions, determining which body parts develop where [28]. The proper functioning of these pathways ensures a correctly formed organism with all components in appropriate positions, while disruptions can lead to developmental abnormalities, such as body parts forming in wrong locations.