Evaluating Zero-Shot Predictors in the DBTL Cycle: A Framework for Accelerating Biomedical Discovery

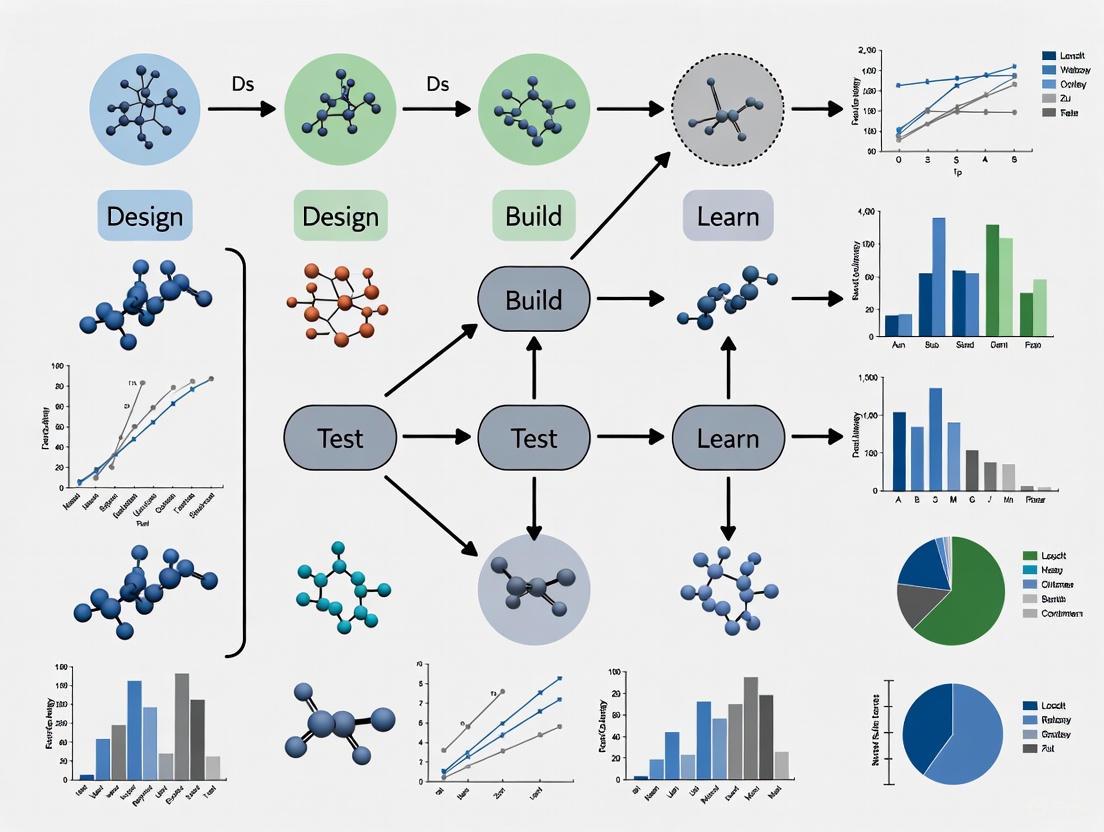

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate and integrate zero-shot predictors into the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle.

Evaluating Zero-Shot Predictors in the DBTL Cycle: A Framework for Accelerating Biomedical Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate and integrate zero-shot predictors into the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle. Covering foundational concepts, practical methodologies, and optimization strategies, it explores how machine learning models that require no prior experimental data can transform protein engineering and drug discovery. We detail validation techniques, including novel metrics and high-throughput testing, and present comparative analyses of leading predictors to guide the selection and application of these powerful tools for enhancing the efficiency and success rate of biological design.

The Rise of Zero-Shot Prediction: Redefining the DBTL Cycle for Synthetic Biology

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle has long been the cornerstone of systematic engineering in synthetic biology and therapeutic development. This iterative process begins with designing biological systems based on existing knowledge, building DNA constructs, testing their performance in vivo or in vitro, and finally learning from the data to inform the next design cycle. However, this approach inherently relies on empirical iteration, where the crucial "Learn" phase occurs only after substantial resources have been invested in the "Build" and "Test" phases. Recent advances in artificial intelligence are fundamentally challenging this paradigm, giving rise to the LDBT cycle, where "Learning" precedes "Design" through the application of foundational models trained on vast biological datasets [1].

This shift represents more than a simple reordering of letters; it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how we approach biological design. Foundational models, pre-trained on extensive datasets encompassing scientific literature, genetic sequences, protein structures, and clinical data, can now make zero-shot predictions—generating functional designs without requiring additional training on specific tasks [1] [2]. This capability is particularly valuable for drug repurposing and protein engineering, where it enables identifying therapeutic candidates for diseases with limited treatment options or designing novel enzymes without iterative experimental optimization. This guide evaluates the performance of this emerging LDBT paradigm against traditional DBTL approaches, providing experimental data and methodologies for researchers navigating this transition.

The DBTL Paradigm: Traditional Workflows and Limitations

The Standard DBTL Cycle in Practice

In traditional DBTL implementations, each phase follows a linear sequence:

- Design: Researchers define objectives and design biological parts using domain knowledge and computational modeling. This phase typically relies on established biological principles and existing literature.

- Build: DNA constructs are synthesized and assembled into plasmids or other vectors, then introduced into characterization systems (e.g., bacterial chassis, cell-free systems).

- Test: Engineered constructs are experimentally measured for performance against objectives set during the Design stage.

- Learn: Data from testing is analyzed and compared to design objectives to inform the next Design round [1].

This cyclic approach has demonstrated success across numerous applications. For instance, in developing a dopamine production strain in Escherichia coli, researchers implemented a knowledge-driven DBTL cycle that achieved a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over state-of-the-art in vivo dopamine production, reaching concentrations of 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L [3]. Similarly, the Riceguard project for iGEM 2025 underwent seven distinct DBTL cycles to refine a cell-free arsenic biosensor, with pivots ranging from system transitions (GMO-based to cell-free) to user reorientation (farmers to households) [4].

Experimental Limitations of Sequential DBTL

Despite its successes, the traditional DBTL framework faces inherent limitations:

- Temporal Inefficiency: Each cycle requires substantial time for building and testing, with constructs often requiring weeks for synthesis and assembly [4].

- Resource Intensity: Extensive experimental iteration consumes significant materials, personnel time, and financial resources.

- Knowledge Lag: Learning occurs only after building and testing, potentially resulting in multiple costly cycles before arriving at optimal solutions [1].

These limitations become particularly pronounced when tackling problems with sparse solution landscapes or limited existing data, such as developing treatments for rare diseases or engineering novel enzyme functions.

The LDBT Revolution: Foundational Models and Zero-Shot Prediction

Core Principles of the LDBT Framework

The LDBT cycle fundamentally reimagines the engineering workflow by placing "Learn" first through the application of foundational models:

- Learn: Foundational models pre-trained on megascale biological datasets perform zero-shot predictions to generate candidate designs [1].

- Design: Computational designs are created based on model predictions without iterative experimental feedback.

- Build: Selected designs are physically constructed, often leveraging high-throughput platforms like cell-free systems.

- Test: Built designs are evaluated experimentally, with results potentially enriching future model training [1].

This approach effectively shifts the iterative learning process from the physical to the computational domain, where exploration is faster, cheaper, and more comprehensive.

Key Foundational Models Enabling LDBT

Table 1: Foundational Models for Biological Design

| Model Name | Domain | Key Capabilities | Zero-Shot Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| TxGNN [2] | Drug repurposing | Predicts drug indications/contraindications across 17,080 diseases | 49.2% improvement in indication prediction, 35.1% for contraindications |

| ESM & ProGen [1] | Protein engineering | Predicts protein structure-function relationships from sequence | Designs functional antibodies and enzymes without additional training |

| ProteinMPNN [1] | Protein design | Generates sequences that fold into specified backbone structures | Nearly 10-fold increase in design success rates when combined with AlphaFold |

| AlphaFold 3 [5] | Biomolecular structures | Predicts structures of protein-ligand, protein-nucleic acid complexes | Outperforms specialized tools in interaction prediction |

| ChemCrow [5] | Chemical synthesis | Integrates expert-designed tools with GPT-4 for chemical tasks | Autonomously plans and executes synthesis of complex molecules |

These models share common characteristics: large-scale pre-training on diverse datasets, generative capabilities for novel designs, and fine-tuning potential for specialized tasks [5]. Their architecture often leverages transformer-based networks or graph neural networks capable of capturing complex biological relationships.

Comparative Performance Analysis: DBTL vs. LDBT

Quantitative Benchmarking Across Applications

Table 2: Performance Comparison of DBTL vs. LDBT Approaches

| Application Domain | Traditional DBTL Performance | LDBT Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Repurposing [2] | Limited to diseases with existing drugs; serendipitous discovery | 49.2% improvement in indication prediction across 17,080 diseases | Zero-shot prediction on diseases with no treatments |

| Enzyme Engineering [1] | Multiple DBTL cycles for optimization | Zero-shot design of functional enzymes (e.g., PET hydrolase) | Increased stability and activity over wild-type |

| Pathway Optimization [1] | Iterative strain engineering required | 20-fold improvement in 3-HB production using iPROBE | Neural network prediction of optimal pathway sets |

| Protein Design [1] | Limited by computational expense of physical models | 10-fold increase in design success rates with ProteinMPNN+AF | De novo protein design with specified structures |

| Biosensor Development [4] | 7 DBTL cycles for optimization | Not reported | Cell-free arsenic biosensor development |

The data demonstrates that LDBT approaches particularly excel in scenarios requiring exploration of vast design spaces or leveraging complex, multi-modal data relationships. For drug repurposing, TxGNN's zero-shot capability addresses the "long tail" of diseases without treatments—approximately 92% of the 17,080 diseases in its knowledge graph lack FDA-approved drugs [2].

Case Study: TxGNN for Zero-Shot Drug Repurposing

Experimental Protocol:

- Knowledge Graph Construction: TxGNN was trained on a medical knowledge graph integrating decades of biological research across 17,080 diseases, containing 9,388 indications and 30,675 contraindications [2].

- Model Architecture: The framework employs a graph neural network with a metric learning module to embed drugs and diseases into a latent space reflecting the KG's geometry. For zero-shot prediction, it creates disease signature vectors based on network topology and transfers knowledge from well-annotated to sparse diseases [2].

- Interpretability Module: The TxGNN Explainer uses GraphMask to generate sparse subgraphs and importance scores for edges, providing multi-hop interpretable rationales connecting drugs to diseases [2].

- Evaluation: Benchmarking against 8 methods under stringent zero-shot conditions, focusing on diseases with limited or no treatment options.

Results: TxGNN achieved a 49.2% improvement in indication prediction accuracy and 35.1% for contraindications compared to existing methods. Human evaluation showed its predictions aligned with off-label prescriptions in a large healthcare system, and explanations were consistent with medical reasoning [2].

Diagram 1: TxGNN Architecture for Zero-Shot Drug Repurposing

Experimental Protocols for LDBT Implementation

Foundational Model Training and Fine-Tuning

Protocol for Training Domain-Specific Foundational Models:

- Data Curation: Assemble large-scale, diverse datasets encompassing the target domain (e.g., protein sequences, drug-disease interactions, metabolic pathways). TxGNN utilized 9,388 indications and 30,675 contraindications across 17,080 diseases [2].

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate architectures (transformers, graph neural networks) based on data structure. Protein language models often use transformer architectures with attention mechanisms [1].

- Pre-training: Train models on self-supervised tasks (e.g., masked token prediction, contrastive learning) to capture underlying patterns without labeled data.

- Metric Learning: Implement distance-based learning techniques to enable knowledge transfer between related domains, crucial for zero-shot prediction to sparse regions [2].

- Validation: Establish rigorous benchmarks with holdout datasets representing real-world application scenarios.

Cell-Free Systems for High-Throughput Validation

Protocol for Cell-Free Testing of LDBT Predictions:

- System Preparation: Prepare crude cell lysates or purified component systems from appropriate source organisms (e.g., E. coli, wheat germ) [1] [3].

- DNA Template Design: Synthesize DNA templates encoding predicted designs without intermediate cloning steps when possible.

- Reaction Assembly: Combine cell-free machinery, DNA templates, and necessary substrates in microtiter plates or droplet microfluidics formats.

- High-Throughput Screening: Implement automated measurement systems (e.g., plate readers, fluorescence-activated sorting) for rapid functional assessment.

- Data Integration: Feed results back to enrich foundational model training datasets [1].

This approach enables testing thousands of predictions in parallel, dramatically accelerating the Build-Test phases that follow Learn-Design in the LDBT cycle.

Diagram 2: LDBT Workflow with Foundational Models

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for LDBT Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in LDBT | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Design Models | ESM, ProGen, ProteinMPNN, MutCompute | Zero-shot protein sequence and structure design | GitHub repositories, web servers |

| Drug Repurposing Platforms | TxGNN, ChemCrow | Predicting new therapeutic uses for existing drugs | Web interfaces, API access |

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold 2 & 3, RoseTTAFold | Biomolecular structure prediction for design validation | Local installation, cloud services |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | PURExpress, homemade lysates | High-throughput testing of genetic designs | Commercial kits, custom preparation |

| Automation Platforms | Liquid handling robots, microfluidics | Scaling Build-Test phases for validation | Biofoundries, core facilities |

These tools collectively enable the end-to-end implementation of LDBT cycles, from initial computational learning to physical validation. Cell-free systems are particularly valuable as they bypass cellular constraints, enable rapid testing (protein production in <4 hours), and scale from picoliters to production volumes [1].

The transition from DBTL to LDBT represents more than a methodological adjustment—it constitutes a fundamental reorientation of biological engineering toward a more predictive, first-principles discipline. The experimental data demonstrates that LDBT approaches can achieve significant performance improvements, particularly for problems with sparse data or vast design spaces. Foundational models enabling zero-shot prediction are no longer theoretical curiosities but practical tools producing functionally validated designs.

However, this paradigm shift does not render experimental work obsolete. Instead, it repositions experimentation toward high-throughput validation and dataset generation for further model refinement. The most successful research programs will likely integrate both approaches: using LDBT for initial design generation and DBTL for fine-tuning and context-specific optimization. As foundational models continue to evolve and biological datasets expand, the LDBT framework promises to accelerate progress across therapeutic development, metabolic engineering, and synthetic biology applications.

What Are Zero-Shot Predictors? Principles and Core Mechanics

Zero-shot predictors are a class of AI models capable of performing tasks or making predictions on data from categories they have never explicitly seen during training. This approach allows models to generalize to novel situations without requiring new labeled data or retraining, a capability that is reshaping research cycles in fields like drug development and synthetic biology [6] [7]. Unlike traditional supervised learning, which needs vast amounts of labeled data for each new category, zero-shot learning relies on auxiliary knowledge—such as semantic descriptions, attributes, or pre-trained representations—to understand and predict unseen classes [6].

Core Principles of Zero-Shot Prediction

The operation of zero-shot predictors is governed by several key principles that enable them to handle unseen data.

Leveraging Auxiliary Knowledge: Without labeled examples, these models depend on additional information to bridge the gap between seen and unseen classes. This can be textual descriptions, semantic attributes, or embedded representations that describe the characteristics of new categories [6] [7]. For instance, a model can learn the concepts of "stripes" from tigers and "yellow" from canaries; it can then identify a "bee" as a "yellow, striped flying insect" without ever having been trained on bee images [6].

The Role of Transfer Learning and Semantic Spaces: Zero-shot learning often uses transfer learning, repurposing models pre-trained on massive, general datasets. These models convert inputs (like words or images) into vector embeddings—numerical representations of their features or meaning [6]. To make a classification, the model compares the embedding of a new input against the embeddings of potential class labels. This comparison happens in a joint embedding space, a shared high-dimensional space where embeddings from different data types (e.g., text and images) can be directly compared using similarity measures like cosine similarity [6].

Foundation Models and Zero-Shot Capabilities: Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-3.5 and protein language models like ESM are inherently powerful zero-shot predictors. They acquire a broad understanding of concepts and relationships from their pre-training on vast corpora of text or protein sequences. This allows them to perform tasks based solely on a natural language prompt or a novel sequence input, without task-specific fine-tuning [8] [1].

Core Mechanics: How Zero-Shot Predictors Work

The mechanical process of zero-shot prediction can be broken down into a sequence of steps, from data preparation to final output.

The flowchart above outlines the general workflow of a zero-shot prediction system.

Input Data and Semantic Representation: The process begins with gathering general input data. The model then processes this input to build semantic representations, organizing information based on the meaning and context of words, phrases, or other features. This step captures deep relationships that go beyond surface-level patterns [7].

Connection to Prior Knowledge: When presented with a new, unseen class or task, the system connects it to the knowledge it acquired during pre-training. It leverages understood concepts, attributes, or descriptions to form a hypothesis about the unfamiliar input [6] [7].

Mapping to a Joint Embedding Space: Both the input data and the auxiliary information (like class labels) are projected into a joint embedding space. This is a critical step that allows for an "apples-to-apples" comparison between different types of data, such as an image and a text description [6]. Models like OpenAI's CLIP are trained from scratch to ensure this alignment is effective.

Similarity Calculation and Prediction: The model calculates the similarity (e.g., cosine similarity) between the embedding of the input data and the embeddings of all potential candidate classes. The class whose embedding is most similar to the input's embedding is selected as the most likely prediction [6].

Output and Evaluation: The system produces its final prediction, which is then reviewed. In enterprise or research settings, this often involves human review, especially for high-stakes decisions, to ensure accuracy and maintain trust [7].

Evaluation in Practice: A DBTL Framework

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a fundamental framework in synthetic biology and drug development for engineering biological systems. Zero-shot predictors are revolutionizing this cycle by accelerating the initial "Design" phase and providing a more reliable in silico "Test" phase.

The Paradigm Shift: From DBTL to LDBT

A significant shift is occurring, moving from the traditional DBTL cycle to a new LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) paradigm. In LDBT, the "Learn" phase comes first, where machine learning models trained on vast datasets are used to make zero-shot designs. This leverages prior knowledge to generate functional designs from the outset, potentially reducing the need for multiple, costly experimental cycles [1]. The table below compares the two approaches.

| Cycle Phase | Traditional DBTL Approach | LDBT with Zero-Shot Predictors |

|---|---|---|

| Learn | Analyze data from previous Build-Test cycles. | Leverage pre-trained models and foundational knowledge for initial design. |

| Design | Rely on domain expertise and limited computational models. | Use AI for zero-shot generation of novel, optimized candidates. |

| Build | Synthesize DNA and introduce into chassis organisms. | Use rapid, automated platforms like cell-free systems for building. |

| Test | Experimentally measure performance in the lab (slow, costly). | Use high-throughput screening and in silico validation (faster). |

Case Study: Zero-Shot Prediction for De Novo Binder Design

A landmark meta-analysis by Overath et al. (2025) provides a robust, real-world example of evaluating zero-shot predictors in a DBTL context for designing protein binders [9]. The study assessed the ability of various computational models to predict the experimental success of 3,766 designed protein binders.

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: To identify the most reliable computational metric for predicting successful binding between a computationally designed protein and its target.

- Dataset: 3,766 designed binders targeting 15 different proteins, with an overall experimental success rate of 11.6% [9].

- Method: Each designed binder-target complex was analyzed with multiple state-of-the-art structure prediction models, including AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3 (AF3), and Boltz-1. Over 200 structural and energetic features were extracted for each complex [9].

- Evaluation: The predictive power of these features was rigorously benchmarked against the ground-truth experimental results.

Key Quantitative Findings:

The analysis identified a single AF3-derived metric as the most powerful predictor of experimental success.

| Predictor Metric | Key Finding | Performance vs. Common Metric (ipAE) |

|---|---|---|

| AF3 ipSAE_min | Most powerful single predictor; evaluates predicted error at high-confidence binding interface. | 1.4-fold increase in Average Precision [9]. |

| Simple Linear Model | A simple model using 2-3 key features outperformed complex black-box models. | Consistently best performance [9]. |

| Optimal Feature Set | AF3 ipSAEmin, Interface Shape Complementarity, and RMSDbinder. | Provides an actionable, interpretable filtering strategy [9]. |

This study highlights a critical insight for the field: complexity does not guarantee better performance. A simple, interpretable model using a few key, high-quality metrics can be the most effective tool for prioritizing designs, thereby streamlining the DBTL cycle [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Integrating zero-shot predictors into a research workflow involves both computational and experimental components. The following table details key resources for implementing this approach.

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models (ESM, ProGen) | Computational Model | Makes zero-shot predictions for protein function, stability, and beneficial mutations from sequence data [1]. |

| Structure Prediction Models (AlphaFold2/3) | Computational Model | Provides structural features (pLDDT, pAE, ipSAE) for in silico validation and ranking of designed proteins [9]. |

| Structure-Based Design Tools (ProteinMPNN) | Computational Model | Designs new protein sequences that fold into a desired backbone structure, often used in a zero-shot manner [1]. |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | Experimental Platform | Rapidly expresses synthesized DNA templates without cloning, enabling high-throughput testing of AI-generated designs [1]. |

| Linear Model with ipSAE_min | Analytical Filter | A simple, interpretable model to rank designed binders and focus experimental efforts on the most promising candidates [9]. |

Zero-shot predictors represent a transformative advancement in computational research, enabling scientists to navigate complex design spaces with unprecedented speed. Their core mechanics—rooted in leveraging auxiliary knowledge and operating within a joint semantic space—provide the foundation for making reliable predictions on novel data. When integrated into the DBTL cycle, particularly within the emerging LDBT paradigm, these tools accelerate the path from concept to validated function. As evidenced by rigorous meta-analyses in protein design, the future lies in combining powerful AI with simple, interpretable evaluation metrics to create a more efficient and predictive bio-engineering pipeline.

The integration of artificial intelligence into protein engineering is catalyzing a fundamental shift from empirical, iterative processes toward predictive, computational design. Central to this transformation is the emergence of sophisticated model architectures capable of zero-shot prediction, where models generate functional protein sequences or structures without requiring additional training data or optimization cycles for each new task. This capability is reshaping the traditional Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, creating a new paradigm where machine learning precedes design in what is being termed the "LDBT" (Learn-Design-Build-Test) framework [1]. Within this context, two complementary architectural approaches have demonstrated remarkable capabilities: protein language models (exemplified by ESM and ProGen) that learn from evolutionary patterns in sequence data, and structure-based tools (including AlphaFold and ProteinMPNN) that operate primarily on three-dimensional structural information. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these key architectures, their performance across standardized benchmarks, and their practical integration in zero-shot protein design pipelines for drug development and biotechnology applications.

Protein Language Models (Evolutionary Sequence-Based)

ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling)

- Architecture & Training: ESM models are transformer-based protein language models trained through self-supervision on millions of natural protein sequences from evolutionary databases [1]. The training objective involves predicting masked amino acids in sequences, allowing the model to learn evolutionary constraints and structural patterns embedded in primary sequences.

- Key Variants: ESM-2 and ESM-3 represent progressively larger parameter models, with ESM-3 featuring up to 98 billion parameters and demonstrating strong performance in both structure prediction and sequence generation tasks [10]. ESM-Inverse Folding (ESM-IF) specifically addresses the inverse folding problem using graph neural networks with geometric vector perceptron layers to encode structural inputs [11].

- Methodology: These models operate on the principle that evolutionary relationships captured in multiple sequence alignments contain implicit structural and functional information. They leverage attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies within amino acid sequences, enabling predictions of structure-function relationships without explicit structural input [1].

ProGen

- Architecture & Training: ProGen is a transformer-based language model trained on a massive dataset of over 280 million protein sequences across diverse families and functions [1] [12]. Unlike ESM's focus on evolutionary sequences, ProGen incorporates natural language tags specifying protein properties and functions, enabling conditional generation.

- Methodology: The model learns the joint distribution of sequences and their functional annotations, allowing for controlled generation of novel proteins with desired properties. ProGen2 represents an advancement with improved training techniques and expanded dataset coverage [10].

Structure-Based Design Tools

AlphaFold2

- Architecture & Training: AlphaFold2 employs a novel transformer-like architecture with invariant point attention and triangle multiplicative updates, enabling end-to-end differentiablestructure prediction from multiple sequence alignments [13]. It was trained on experimentally determined structures from the Protein Data Bank alongside evolutionary sequence data.

- Methodology: The system combines physical and geometric constraints with learned patterns from known structures, producing highly accurate atomic-level predictions. Its Evoformer module processes multiple sequence alignments to extract co-evolutionary signals, while the structure module generates atomic coordinates [13].

ProteinMPNN

- Architecture & Training: ProteinMPNN utilizes a message-passing neural network (MPNN) architecture operating on k-NN graphs of protein backbones [11] [14]. It was trained on a large corpus of high-quality protein structures to predict amino acid sequences that will fold into a given backbone structure.

- Methodology: The model treats each residue as a node in a graph and updates node features through message-passing between spatial neighbors. This enables efficient reasoning about side-chain interactions and structural constraints for sequence design [11]. Unlike autoregressive approaches, it can generate sequences in a single forward pass with conditional independence between positions.

Table 1: Core Architectural Characteristics of Key Protein AI Models

| Model | Architecture | Primary Input | Primary Output | Training Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESM | Transformer | Protein Sequences | Sequences/Structures | Millions of natural sequences [1] |

| ProGen | Transformer | Sequences + Tags | Novel Sequences | 280M+ diverse sequences [1] |

| AlphaFold2 | Evoformer + Structure Module | MSA + Templates | 3D Atomic Coordinates | PDB structures + sequences [13] |

| ProteinMPNN | Message-Passing Neural Network | Backbone Structure | Optimal Sequences | Curated high-quality structures [11] |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Comparison

Sequence Recovery and Inverse Folding Capabilities

Inverse folding—designing sequences that fold into a target structure—represents a critical benchmark for protein design tools. The PDB-Struct benchmark provides comprehensive evaluation across multiple metrics, including sequence recovery (similarity to native sequences) and refoldability (ability to fold into target structures) [14].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Inverse Folding Tasks (CATH 4.2 Benchmark)

| Model | Sequence Recovery (%) | TM-Score | pLDDT | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProteinMPNN | 43.9% (MHC-I) 32.0% (MHC-II) | 0.77 | 0.81 | Fixed-backbone design with MPNN [11] |

| ESM-IF | 50.1% (MHC-I) | 0.79 | 0.83 | Graph neural networks with GVP layers [11] [14] |

| ESM-Design | Moderate | 0.71 | 0.75 | Structure-prediction based sampling [14] |

| AF-Design | Low | 0.69 | 0.72 | Gradient-based optimization [14] |

Experimental data from TCR design applications shows that ESM-IF achieves approximately 50.1% sequence recovery for MHC-I complexes, outperforming ProteinMPNN's 43.9% recovery on the same dataset [11]. Both methods significantly exceed physics-based approaches like Rosetta in sequence recovery metrics.

Functional Protein Design Applications

TCR and Therapeutic Protein Design In designing T-cell receptors (TCRs) for therapeutic applications, structure-based methods demonstrate particular strength. ProteinMPNN and ESM-IF were evaluated for designing fixed-backbone TCRs targeting peptide-MHC complexes. The designs were assessed through structural modeling with TCRModel2, Rosetta energy scores, and molecular dynamics simulations with MM/PBSA binding affinity calculations [11]. Results indicated that both deep learning methods produced designs with modeling confidence scores and predicted binding affinities comparable to native TCRs, with some designs showing improved affinity [11].

Enzyme and Binding Protein Design ProteinMPNN has successfully designed functional enzymes, including variants of TEV protease with improved catalytic activity compared to parent sequences [1]. When combined with deep learning-based structure assessment (AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold), ProteinMPNN achieved a nearly 10-fold increase in design success rates compared to previous methods [1].

Zero-Shot Antibody and Miniprotein Design Language models like ESM have demonstrated capability in zero-shot prediction of diverse antibody sequences [1]. Similarly, structure-based approaches have created miniproteins specifically engineered to bind particular targets and innovative antibodies with high affinity and specificity [14].

Refoldability and Stability Metrics

The PDB-Struct benchmark introduces refoldability as a critical metric, assessing whether designed sequences actually fold into structures resembling the target. This is evaluated using TM-score (structural similarity) and pLDDT (folding confidence) from structure prediction models [14]. ProteinMPNN and ESM-IF achieve TM-scores of 0.77 and 0.79 respectively, significantly outperforming ESM-Design (0.71) and AF-Design (0.69) [14]. These results highlight the advantage of encoder-decoder architectures for structure-based design over methods that rely on structure prediction models for sequence generation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Benchmarking Protocols

PDB-Struct Benchmark Implementation

- Dataset Curation: High-quality structures are selected from CATH database, ensuring non-redundancy and structural diversity [14]

- Sequence Generation: Each model generates sequences for fixed backbone structures using recommended parameters

- Structure Prediction: Generated sequences are folded using AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to predict their 3D structures

- Metric Calculation: TM-score (structural similarity to target) and pLDDT (confidence metrics) are computed [14]

- Stability Assessment: Sequences are evaluated with protein stability predictors where experimental data exists [14]

TCR Design Evaluation Protocol

- Structural Dataset Preparation: Non-redundant TCR:pMHC complexes (32 MHC-I, 6 MHC-II) are curated [11]

- Interface Design: CDR3 positions (α and β chains) are designed while keeping backbone fixed

- Sequence Recovery Calculation: Percentage identity between designed and native amino acids at designed positions

- Structural Modeling: Designed sequences are modeled with TCRModel2 for structural validation [11]

- Energetic Assessment: Rosetta energy functions evaluate interface quality and complex stability

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Molecular Dynamics with MM/PBSA calculations benchmarked against experimental binding data [11]

Zero-Shot Prediction Assessment

For evaluating zero-shot capabilities, models are tested on sequences or structures without prior exposure to similar folds or families. Performance is measured through:

- Sequence Recovery: Ability to reproduce native-like sequences for natural structures [14]

- Structural Faithfulness: TM-score between predicted structure of designed sequence and target backbone [14]

- Functional Success: Experimental validation of designed proteins in intended applications [1]

Integration in the DBTL Cycle and Workflow Diagrams

The integration of these tools is transforming the traditional DBTL cycle into the LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) paradigm, where machine learning precedes design [1].

Diagram 1: LDBT Paradigm Shift - Machine learning precedes design

Structure-Based Design Workflow

Diagram 2: Structure-Based Protein Design Pipeline

Inverse Folding with Structural Feedback

Recent advances incorporate structural feedback to refine inverse folding models through Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) [10]:

Diagram 3: Inverse Folding with Structural Feedback Loop

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Tools

Table 3: Key Research Resources for AI-Driven Protein Design

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB | Database | 200M+ predicted structures for target identification [13] | Public |

| ESM Metagenomic Atlas | Database | 700M+ predicted structures from metagenomic data [13] | Public |

| Protein Data Bank | Database | Experimentally determined structures for training/validation [13] | Public |

| CATH | Database | Curated protein domain classification for benchmarking [14] | Public |

| Cell-Free Expression | Platform | Rapid protein synthesis without cloning [1] | Commercial |

| RoseTTAFold | Software | Alternative structure prediction for validation [13] | Public |

| PDB-Struct Benchmark | Framework | Standardized evaluation of design methods [14] | Public |

The comparative analysis of key protein AI architectures reveals distinct strengths and optimal applications for each platform. Protein language models like ESM and ProGen excel in zero-shot generation of novel sequences and leveraging evolutionary patterns, while structure-based tools including AlphaFold and ProteinMPNN demonstrate superior performance in fixed-backbone design and structural faithfulness. The integration of these complementary approaches through workflows that incorporate structural feedback represents the cutting edge of computational protein design.

Experimental benchmarks consistently show that encoder-decoder models (ProteinMPNN, ESM-IF) outperform structure-prediction-based methods (ESM-Design, AF-Design) in refoldability metrics, achieving TM-scores of 0.77-0.79 versus 0.69-0.71 [14]. Meanwhile, the emergence of preference optimization techniques like DPO fine-tuned with structural feedback demonstrates potential for further enhancements, with reported TM-score improvements from 0.77 to 0.81 on challenging targets [10].

As these technologies mature, their integration into the LDBT paradigm—combining machine learning priors with rapid cell-free testing—is accelerating the protein design process from months to days while expanding access to unexplored regions of the protein functional universe [1] [12]. This convergence of architectural innovation, standardized benchmarking, and experimental validation promises to unlock bespoke biomolecules with tailored functionalities for therapeutic, catalytic, and synthetic biology applications.

The Role of Megascale Data in Training Foundational Models for Biology

In the field of modern biology, "megascale data" refers to datasets characterized by their unprecedented volume, variety, and velocity [15]. These datasets are transforming biological research by enabling the training of foundational models (FMs)—sophisticated artificial intelligence systems that learn fundamental biological principles from massive, diverse data collections. The defining characteristics of biological megadata include volumes reaching terabytes, such as the ProteomicsDB with 5.17 TB covering 92% of known human genes; variety spanning genomic sequences, protein structures, and clinical records; and velocity enabled by technologies that produce billions of DNA sequences daily [15]. This data explosion is critically important because it provides the essential feedstock for training AI models that can accurately predict protein structures, simulate cellular behavior, and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The relationship between data scale and model capability follows a clear pattern: as datasets expand from thousands to millions of data points, foundational models transition from recognizing simple patterns to uncovering complex biological relationships that elude human observation and traditional computational methods. For protein researchers and drug development professionals, this paradigm shift enables a new approach to the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, where models pre-trained on megascale data can make accurate "zero-shot" predictions without additional training, potentially streamlining the entire protein engineering pipeline [1] [16].

Megascale Data in Action: Key Experiments and Case Studies

Case Study: Mega-Scale Protein Folding Stability Analysis

A landmark 2023 study demonstrated the power of megascale data generation through cDNA display proteolysis, a method that measured thermodynamic folding stability for up to 900,000 protein domains in a single week [17]. This approach yielded a curated set of approximately 776,000 high-quality folding stabilities covering all single amino acid variants and selected double mutants of 331 natural and 148 de novo designed protein domains [17]. The experimental protocol involved several key steps: creating a DNA library encoding test proteins, transcribing and translating them using cell-free cDNA display, incubating protein-cDNA complexes with proteases, and then using deep sequencing to quantify protease resistance as a measure of folding stability [17].

The resulting dataset uniquely comprehensive because it measured all single mutants for hundreds of domains under identical conditions, unlike traditional thermodynamic databases with their skewed assortment of mutations measured under varied conditions [17]. This megascale approach revealed novel insights about environmental factors influencing amino acid fitness, thermodynamic couplings between protein sites, and the divergence between evolutionary amino acid usage and folding stability. The data's consistency with traditional purified protein measurements (Pearson correlations >0.75) validated the method's accuracy while highlighting its extraordinary scale [17].

Case Study: Automated Protein Engineering with Foundational Models

A 2025 study showcased the integration of protein language models (PLMs) with automated biofoundries in a protein language model-enabled automatic evolution (PLMeAE) platform [16]. This system created a closed-loop DBTL cycle where the ESM-2 protein language model made zero-shot predictions of 96 variants to initiate the process. The biofoundry then constructed and evaluated these variants, with results fed back to train a fitness predictor, which designed subsequent rounds of variants with improved fitness [16].

Using Methanocaldococcus jannaschii p-cyanophenylalanine tRNA synthetase as a model enzyme, the platform completed four evolution rounds within 10 days, yielding mutants with enzyme activity improved by up to 2.4-fold [16]. The system employed two distinct modules: Module I for proteins without previously identified mutation sites used PLMs to predict high-fitness single mutants, while Module II for proteins with known mutation sites sampled informative multi-mutant variants for experimental characterization [16]. This approach demonstrated superior performance compared to random selection and traditional directed evolution, highlighting how megascale data generation and foundational models can dramatically accelerate protein engineering.

Table 1: Key Experimental Case Studies Utilizing Megascale Data

| Case Study | Data Scale | Methodology | Key Findings | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Folding Stability [17] | ~776,000 folding stability measurements | cDNA display proteolysis with deep sequencing | Quantified environmental factors affecting amino acid fitness and thermodynamic couplings between sites | Revealed quantitative rules for how sequences encode folding stability |

| PLMeAE Platform [16] | 4 rounds of 96 variants each | Protein language models + automated biofoundry | Improved enzyme activity 2.4-fold within 10 days | Demonstrated accelerated protein engineering via closed-loop DBTL |

Comparative Analysis of Foundational Models and Zero-Shot Predictors

Benchmarking Single-Cell Foundation Models

A comprehensive 2025 benchmark study evaluated six single-cell foundation models (scFMs) against established baselines, assessing their performance on two gene-level and four cell-level tasks under realistic conditions [18]. The study examined models including Geneformer, scGPT, UCE, scFoundation, LangCell, and scCello across diverse datasets representing different biological conditions and clinical scenarios like cancer cell identification and drug sensitivity prediction [18]. Performance was assessed using 12 metrics spanning unsupervised, supervised, and knowledge-based approaches, including a novel metric called scGraph-OntoRWR designed to uncover intrinsic biological knowledge encoded by scFMs [18].

The benchmark revealed several critical insights about current foundation models. First, no single scFM consistently outperformed others across all tasks, emphasizing the need for task-specific model selection [18]. Second, while scFMs demonstrated robustness and versatility across diverse applications, simpler machine learning models sometimes adapted more efficiently to specific datasets, particularly under resource constraints [18]. The study also found that pretrained zero-shot scFM embeddings genuinely captured biologically meaningful insights into the relational structure of genes and cells, with performance improvements arising from a smoother cell-property landscape in the latent space that reduced training difficulty for task-specific models [18].

Evaluation of Zero-Shot Predictors on Megascale Data

The protein folding stability dataset of 776,000 measurements has served as a critical benchmark for evaluating various zero-shot predictors [17] [1]. These analyses revealed how different models leverage megascale data to make accurate predictions without task-specific training. Protein language models like ESM and ProGen demonstrate particular strength in zero-shot prediction of beneficial mutations by learning evolutionary relationships from millions of protein sequences [1]. Similarly, structure-based tools like MutCompute use deep neural networks trained on protein structures to associate amino acids with their chemical environments, enabling prediction of stabilizing substitutions without additional data [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Foundation Model Categories and Applications

| Model Category | Representative Models | Training Data | Zero-Shot Capabilities | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models | ESM-2, ProGen [1] [16] | Millions of protein sequences | Predicting beneficial mutations, inferring function | Antibody affinity maturation, enzyme optimization |

| Single-Cell Foundation Models | Geneformer, scGPT, scFoundation [18] | 27-50 million single-cell profiles | Cell type annotation, batch integration | Tumor microenvironment analysis, cell atlas construction |

| Multimodal Foundation Models | ProCyon, PoET-2 [19] | Text, sequence, structure, experimental data | Biological Q&A, controllable generation | Multi-property optimization, knowledge-grounded design |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

cDNA Display Proteolysis Workflow

The cDNA display proteolysis method for megascale protein stability measurement follows a detailed experimental protocol [17]:

Library Preparation: Synthetic DNA oligonucleotide pools are created, with each oligonucleotide encoding one test protein.

Transcription/Translation: The DNA library is transcribed and translated using cell-free cDNA display, resulting in proteins covalently attached to their cDNA at the C terminus.

Protease Incubation: Protein-cDNA complexes are incubated with varying concentrations of protease (trypsin or chymotrypsin), leveraging the principle that proteases cleave unfolded proteins more readily than folded ones.

Reaction Quenching & Pull-Down: Protease reactions are quenched, and intact (protease-resistant) proteins are isolated using pull-down of N-terminal PA tags.

Sequencing & Analysis: The relative abundance of surviving proteins at each protease concentration is determined by deep sequencing, with stability inferred using a Bayesian model of the experimental procedure.

The method models protease cleavage using single turnover kinetics, assuming enzyme excess over substrates, and infers thermodynamic folding stability (ΔG) by separately considering idealized folded and unfolded states with their unique protease susceptibility profiles [17].

Automated DBTL Cycle Implementation

The protein language model-enabled automatic evolution (PLMeAE) platform implements a sophisticated, automated Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle [16]:

Design Phase: Protein language models (ESM-2) perform zero-shot prediction of promising variants. For proteins without known mutation sites (Module I), each amino acid is individually masked and analyzed to predict mutation impact. For proteins with known sites (Module II), the model samples informative multi-mutant variants.

Build Phase: An automated biofoundry constructs the proposed variants using high-throughput core instruments including liquid handlers, thermocyclers, and fragment analyzers coordinated by robotic arms and scheduling software.

Test Phase: The biofoundry expresses proteins and conducts functional assays, with comprehensive metadata tracking and real-time data sharing.

Learn Phase: Experimental results are used to train a supervised machine learning model (multi-layer perceptron) that correlates protein sequences with fitness levels, informing the next design iteration.

This closed-loop system completes multiple DBTL cycles within days, continuously improving protein fitness through data-driven optimization [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Megascale Biology

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| cDNA Display Platform [17] | Links proteins to their encoding cDNA for sequencing-based functional analysis | High-throughput protein stability measurements (776,000 variants) |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems [1] | Enables rapid protein synthesis without living cells | Coupling with cDNA display for megascale stability mapping |

| Automated Biofoundry [16] | Integrates liquid handlers, thermocyclers, and robotic arms for automated experimentation | Closed-loop protein engineering (PLMeAE platform) |

| Protein Language Models (ESM-2) [16] | Predicts protein function and stability from evolutionary patterns | Zero-shot variant design in automated DBTL cycles |

| Single-Cell Foundation Models [18] | Analyzes transcriptomic patterns at single-cell resolution | Cell type annotation, drug sensitivity prediction |

The integration of megascale data generation with foundational AI models is fundamentally transforming biological research and therapeutic development. As evidenced by the case studies and comparisons presented, datasets comprising hundreds of thousands to millions of measurements are enabling a new paradigm where zero-shot predictors can accurately forecast protein behavior, cellular responses, and molecular function without additional training. This capability is particularly valuable within the DBTL cycle framework, where it accelerates the engineering of proteins with enhanced stability, activity, and manufacturability.

Looking forward, the field is evolving toward multimodal foundation models that integrate sequence, structure, chemical, and textual information into unified representational spaces [19]. Systems like ProCyon exemplify this trend, combining 11 billion parameters across multiple data modalities to enable biological question answering and phenotype prediction [19]. Simultaneously, the concept of "design for manufacturability" is becoming embedded in AI-driven biological design, with models increasingly optimizing not just for structural correctness but for practical considerations like expression yield, solubility, and stability under industrial processing conditions [19]. As these trends converge, megascale data will continue to serve as the essential foundation for AI systems that can reliably design functional biological molecules and systems, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics and biotechnologies.

Implementing Zero-Shot Predictors: From In-Silico Design to Wet-Lab Validation

The traditional Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle has long been a cornerstone of engineering disciplines, including synthetic biology and drug development. This iterative process begins with designing biological systems, building DNA constructs, testing their performance, and finally learning from the data to inform the next design cycle [20]. However, this approach often requires multiple expensive and time-consuming iterations to achieve desired functions. A significant paradigm shift is emerging with the integration of advanced machine learning, particularly zero-shot predictors, which can make accurate predictions without additional training on target-specific data [20]. This transformation is reordering the classic cycle to Learning-Design-Build-Test (LDBT), where machine learning models pre-loaded with evolutionary and biophysical knowledge precede and inform the design phase [20]. This review compares the practical implementation of zero-shot prediction methods within automated DBTL pipelines, evaluating their performance across various biological applications and providing experimental protocols for researchers seeking to adopt these transformative approaches.

Comparative Analysis of Zero-Shot Prediction Performance

Integration of zero-shot predictors into DBTL pipelines has demonstrated significant improvements in success rates and efficiency across multiple domains, from drug discovery to protein engineering. The following comparative analysis examines the quantitative performance of prominent approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Zero-Shot Prediction Methods in Biological Applications

| Method | Application Domain | Performance Metrics | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZeroBind [21] | Drug-target interaction prediction | AUROC: 0.8139 (±0.0035) on inductive test sets; AUPR: Superior to baselines | Protein-specific modeling with subgraph matching for novel target identification |

| PLMeAE Module I [22] | Protein engineering without known mutation sites | 2.4-fold enzyme activity improvement in 4 rounds (10 days) | Identifies critical mutation sites de novo using protein language models |

| PLMeAE Module II [22] | Protein engineering with known mutation sites | Enabled focused optimization at specified sites | Efficient combinatorial optimization with reduced screening burden |

| AF3 ipSAE_min [9] | De novo binder design | 1.4-fold increase in average precision vs. ipAE | Superior interface-focused binding prediction |

| DDI-JUDGE [23] | Drug-drug interaction prediction | AUC: 0.642/0.788 (zero-shot/few-shot); AUPR: 0.629/0.801 | Leverages LLMs with in-context learning for DDI prediction |

Table 2: Experimental Success Rates Across Protein Design Approaches

| Design Approach | Experimental Success Rate | Key Enabling Technologies | Typical Screening Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Physics-Based [9] | <1% | Rosetta, molecular dynamics | Hundreds to thousands |

| AF2 Filtering [9] | Nearly 10x improvement over traditional | AlphaFold2, pLDDT, pAE metrics | Hundreds |

| Zero-Shot AF3 ipSAE [9] | 11.6% overall (3,766 designed binders) | AlphaFold3, interface shape complementarity | Focused libraries (tens to hundreds) |

| Simple Linear Model [9] | Consistently best performance | AF3 ipSAEmin, shape complementarity, RMSDbinder | Minimal screening required |

The data reveal that zero-shot methods consistently outperform traditional approaches, particularly in scenarios involving novel targets or proteins where training data is scarce. The success of simple, interpretable models combining few key features challenges the assumption that complexity necessarily correlates with better performance in biological prediction tasks [9].

Experimental Protocols for Zero-Shot Integration

Protein-Specific Zero-Shot DTI Prediction with ZeroBind

The ZeroBind protocol implements a meta-learning framework for drug-target interaction prediction, specifically designed for generalization to unseen proteins and drugs [21].

Methodology Details:

- Data Preparation: Employ network-based negative sampling to alleviate annotation imbalance, creating a balanced dataset for training [21].

- Meta-Task Formulation: Define each protein's binding drug predictions as a separate learning task within a meta-learning framework.

- Graph Representation: Represent proteins and drugs as graph structures, processed through Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) to generate embeddings [21].

- Subgraph Information Bottleneck (SIB): Implement weakly supervised SIB to identify maximally informative and compressive subgraphs in protein structures as potential binding pockets, enhancing interpretability [21].

- Task-Adaptive Attention: Incorporate a self-attention mechanism to weight the contribution of different protein-specific tasks to the meta-learner.

- Training Strategy: Utilize MAML++ as the training framework, with support and query sets for meta-learning [21].

Validation Approach:

- Perform five independent experiments with different random seeds for dataset partitioning

- Evaluate on three independent test sets: Transductive, Semi-inductive, and Inductive

- Report AUROC and AUPRC with standard deviations [21]

Protein Language Model-Enabled Automatic Evolution (PLMeAE)

The PLMeAE platform integrates protein language models with automated biofoundries for continuous protein evolution [22].

Module I Protocol (Proteins Without Known Mutation Sites):

- Zero-Shot Variant Design: Mask each amino acid in the wild-type sequence and use ESM-2 protein language model to predict single-residue substitutions with high likelihood of improving fitness [22].

- Variant Selection: Rank variants by predicted fitness gains and select top 96 candidates for experimental testing.

- Automated Construction: Utilize biofoundry capabilities for automated DNA synthesis, pathway assembly, and sequence verification.

- High-Throughput Testing: Implement automated 96-well growth protocols with ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) for functional characterization [22].

- Model Retraining: Feed experimental results back to train a supervised multi-layer perceptron model as a fitness predictor for subsequent rounds.

Module II Protocol (Proteins With Known Mutation Sites):

- Focused Library Design: For proteins with previously identified mutation sites, use PLMs to sample high-fitness multi-mutant variants at specified positions [22].

- Combinatorial Optimization: Explore synergistic effects between mutations at known functional sites.

- Iterative Refinement: Conduct multiple DBTL rounds with progressively improved variants.

Diagram 1: PLMeAE workflow showing Module I and II integration. The system uses zero-shot prediction to initiate the cycle, then iteratively improves proteins through automated biofoundry testing.

De Novo Binder Design with Interface-Focused Metrics

Recent meta-analysis of 3,766 computationally designed binders established a robust protocol for predicting experimental success in de novo binder design [9].

Experimental Workflow:

- Dataset Compilation: Curate diverse designed binders experimentally tested against 15 different targets, acknowledging severe class imbalance (11.6% overall success rate) [9].

- Structure Prediction: Re-predict binder-target complexes using multiple state-of-the-art models (AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3, Boltz-1).

- Feature Extraction: Calculate over 200 structural and energetic features for each complex.

- Metric Evaluation: Assess predictive power of features, identifying AF3-derived interaction prediction Score from Aligned Errors (ipSAE) as optimal.

- Model Validation: Compare simple linear models against complex machine learning approaches, finding optimal performance with minimal feature sets.

Optimal Feature Combination:

- AF3 ipSAE_min: Evaluating predicted error at highest-confidence binding interface regions

- Interface Shape Complementarity: Traditional biophysical surface fitting measure

- RMSD_binder: Structural deviation between design and AF3-predicted structure [9]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing zero-shot prediction pipelines requires specific reagent systems and computational tools. The following table details key solutions for establishing these workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Zero-Shot DBTL Pipelines

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function in Pipeline | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 [22] | Protein Language Model | Zero-shot prediction of high-fitness variants | PLMeAE platform for protein engineering |

| AlphaFold3 [9] | Structure Prediction | ipSAE metric calculation for interface quality | De novo binder design evaluation |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems [20] | Protein Synthesis Platform | Rapid in vitro transcription/translation | High-throughput protein variant testing |

| RetroPath [24] | Pathway Design Software | Automated enzyme selection for metabolic pathways | Flavonoid production optimization |

| JBEI-ICE [24] | Data Repository | Centralized storage of DNA parts and designs | Automated DBTL pipeline data tracking |

| PartsGenie [24] | DNA Design Tool | Automated ribosome binding site optimization | Combinatorial library design for pathway engineering |

| DropAI [20] | Microfluidics Platform | Ultra-high-throughput screening (100,000+ reactions) | Protein stability mapping |

| PlasmidMaker [22] | Automated Construction | High-throughput plasmid design and assembly | Biofoundry-based variant construction |

Implementation Workflow for Zero-Shot Enhanced DBTL

Successful integration of zero-shot prediction into automated DBTL pipelines follows a systematic workflow that merges computational and experimental components.

Diagram 2: LDBT cycle emphasizing the repositioning of Learning as the initial phase, enabled by zero-shot predictors with pre-trained biological knowledge.

Critical Implementation Considerations

Computational Infrastructure:

- Protein language models (ESM-2) require significant GPU resources for inference and training [22]

- Structure prediction tools (AlphaFold3) demand high-performance computing clusters for large-scale applications [9]

- Automated data tracking systems (JBEI-ICE) are essential for maintaining sample provenance across design-build-test transitions [24]

Experimental Optimization:

- Cell-free expression systems enable rapid testing but require optimization of expression conditions [20]

- Microfluidics platforms increase throughput but introduce technical complexity in fluid handling [20]

- Analytical methods (UPLC-MS/MS) must be validated for quantitative measurements of target compounds [24]

The integration of zero-shot prediction into automated DBTL pipelines represents a fundamental shift in biological engineering, moving from empirical iteration toward predictive design. The comparative data demonstrate that methods like ZeroBind, PLMeAE, and AF3 ipSAE consistently outperform traditional approaches, particularly for novel targets with limited experimental data. The emergence of simple, interpretable models that match or exceed complex algorithms suggests a maturation of the field toward practical, actionable prediction frameworks [9].

Future developments will likely focus on expanding the scope of zero-shot prediction to more complex biological functions, improving the integration between computational and experimental components, and developing standardized benchmarks for comparing different approaches. As these technologies mature, the vision of first-principles biological engineering similar to established engineering disciplines comes closer to reality, potentially ultimately achieving a Design-Build-Work paradigm that minimizes iterative optimization [20].

The classical paradigm for engineering biological systems has long been the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle. In this workflow, researchers design biological parts, build DNA constructs, test them in living systems, and learn from the data to inform the next design iteration [1]. However, the integration of advanced machine learning (ML) and cell-free expression systems is fundamentally reshaping this approach, enabling a reordered "LDBT" cycle (Learn-Design-Build-Test) where learning precedes design through zero-shot predictors [1]. This case study examines how cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) serves as the critical "Build-Test" component that synergizes with computational learning to accelerate protein engineering campaigns. We evaluate the performance of CFPS against traditional cell-based alternatives within the context of evaluating zero-shot predictors, highlighting its unique advantages in generating rapid, high-quality data for model training and validation.

Cell-free systems leverage the protein synthesis machinery from cell extracts or purified components, enabling in vitro transcription and translation without the constraints of living cells [25]. This technology provides the experimental throughput required to close the loop between computational prediction and experimental validation, making it particularly valuable for assessing the performance of AI-driven protein design tools [1] [9].

Technology Comparison: CFPS vs. Cell-Based Expression

Performance Metrics and Operational Characteristics

The table below summarizes key performance differences between cell-free and cell-based protein expression systems relevant to protein engineering workflows.

| Parameter | Cell-Free Protein Synthesis | Traditional Cell-Based Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Process Time | 1-2 days (including extract preparation) [26] | 1-2 weeks [26] |

| Typical Protein Yield | >1 g/L in <4 hours [1]; up to several mg/mL in advanced systems [25] | Highly variable; depends on protein and host system |

| Toxic Protein Expression | Excellent (no living cells to maintain) [25] [26] | Poor (toxicity affects host viability and yield) [25] |

| Experimental Control & Manipulation | High (open system, direct reaction access) [25] [26] | Low (limited by cellular barriers and metabolism) [26] |

| Throughput Potential | Very High (compatible with microfluidics and automation) [1] [25] | Moderate (limited by transformation and cultivation) |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acid Incorporation | Straightforward [25] [26] | Complex (requires engineered hosts and specific conditions) |

| Membrane Protein Production | Good (with supplemented liposomes/nanodiscs) [25] | Challenging (often results in misfolding or inclusion bodies) |

Application in Evaluating Zero-Shot Predictors

The critical advantage of CFPS in the LDBT cycle is its ability to rapidly generate the large-scale experimental data needed to benchmark computational predictions. A landmark example is the ultra-high-throughput mapping of protein stability for 776,000 protein variants using cDNA display and CFPS. This massive dataset became an invaluable resource for objectively evaluating the predictability of various zero-shot predictors [1]. Similarly, in de novo binder design, where computational tools can generate thousands of designs, CFPS enables the high-throughput testing necessary to move beyond heuristic filtering. Research has shown that using a simple linear model based on interface-focused metrics like AF3 ipSAE_min and biophysical properties to rank designs, followed by experimental testing, can significantly improve success rates [9]. CFPS provides the ideal "Test" platform for this optimized filtering strategy.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Protein Stability Profiling

This protocol is adapted from studies that generated large-scale stability data for benchmarking zero-shot predictors [1].

- Objective: To experimentally determine the folding stability (ΔG) of thousands of protein variants designed in silico.

- CFPS Platform: Coupled transcription-translation system based on E. coli lysate [25].

- Key Reagents & Setup:

- DNA Template: PCR-amplified linear DNA templates encoding variant libraries.

- Reaction Format: Small-scale (e.g., 10-50 µL) batch reactions in multi-well plates.

- Coupling to cDNA Display: The synthesized protein is covalently linked to its encoding mRNA via a puromycin linker, creating a physical link between genotype and phenotype [1].

- Denaturation Challenge: The protein-cDNA complexes are subjected to a gradient of denaturant (e.g., urea).

- Functional Test: Stable, folded proteins protect their cDNA from degradation. The amount of intact cDNA for each variant after denaturation is quantified by high-throughput sequencing, allowing for ΔG calculation [1].

- Data Analysis: The experimentally determined ΔG values for all variants are compiled and used as a ground-truth dataset to assess the accuracy and robustness of different zero-shot stability predictors.

Protocol 2: Validation of De Novo Designed Binders

This protocol outlines the testing of computationally designed protein binders, a workflow where CFPS drastically accelerates the DBTL cycle [9].

- Objective: To express and validate the binding function and affinity of AI-generated protein binders.

- CFPS Platform: Reconstituted system (e.g., PUREfrex) for high purity and reduced background [26].

- Key Reagents & Setup:

- DNA Template: Plasmid DNA encoding the designed binder sequence.

- Reaction Format: 96-well or 384-well plate format for parallel expression.

- Labeling: Incorporation of a fluorescent or affinity tag (e.g., FLAG-tag) during synthesis for detection and purification.

- Functional Test:

- Direct Binding Assay: The cell-free reaction mixture containing the synthesized binder is applied directly to an ELISA plate coated with the target antigen. Binding is detected via the incorporated tag.

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI): For affinity quantification, the synthesized binder can be captured from the CFPS mixture onto a sensor chip via its tag, and the binding kinetics to the flowing target are measured.

- Data Analysis: Results from the binding assays are used to calculate success rates and correlate with computational confidence metrics (e.g.,

ipSAE_min,pLDDT), thereby validating and refining the predictive models [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents and their functions in a typical CFPS workflow for protein engineering.

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Cell Extract (Lysate) | Provides the fundamental enzymatic machinery for transcription and translation (e.g., RNA polymerase, ribosomes, translation factors). Common sources are E. coli, wheat germ, and insect cells [25] [27]. |

| Energy Source | Regenerates ATP, the primary energy currency for protein synthesis. Common systems use phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), creatine phosphate, or other secondary energy sources [25]. |

| Amino Acid Mixture | Building blocks for protein synthesis. Mixtures can be modified to include non-canonical amino acids for specialized applications [25] [26]. |

| DNA Template | Encodes the gene of interest. Can be circular plasmid or linear PCR product. The template is added directly to the reaction to initiate synthesis [25]. |

| Liposomes / Nanodiscs | Membrane-mimicking structures co-added to the reaction to facilitate the correct folding and solubilization of membrane proteins [25]. |

| Reconstituted System (PURE) | A fully defined system composed of individually purified components of the translation machinery. Offers superior precision and control, reduces background, and is ideal for incorporating non-canonical amino acids [25] [26]. |

Workflow Visualization: Traditional vs. Accelerated LDBT

The following diagram contrasts the classical DBTL cycle with the machine learning-accelerated LDBT cycle enabled by cell-free testing.

Discussion and Future Outlook

The integration of cell-free expression systems into the protein engineering workflow represents a transformative advancement, particularly for the evaluation of zero-shot predictors. The quantitative data presented in this study unequivocally demonstrates that CFPS outperforms cell-based methods in speed, flexibility, and suitability for high-throughput testing. This capability is the cornerstone of the emerging LDBT paradigm, where large-scale experimental data generated by CFPS is used both to benchmark computational models and to serve as training data for the next generation of predictors [1] [28].

The future of this field points toward even tighter integration. As biofoundries increase automation [29], and as AI tools become more sophisticated at tasks like predicting experimental success from complex feature sets [9], the role of CFPS will become more central. Its utility will expand from primarily testing predictions to also generating the "megascale" datasets required to build the foundational models that will power future zero-shot design tools [1]. The ongoing commercialization and scaling of CFPS, evidenced by a market projected to grow at a CAGR of 7.3% to over $300 million by 2030 [27], will further cement its status as an indispensable technology for modern protein engineering and computational biology.

The ability to design protein binders from scratch—a process known as de novo binder design—stands as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology with profound implications for therapeutic development, diagnostics, and basic research. While computational methods have advanced to the point where thousands of potential binders can be generated in silico, the field has faced a persistent bottleneck: the notoriously low and unpredictable experimental success rates, historically often falling below 1% [9]. This discrepancy between computational abundance and experimental validation has represented a significant challenge for researchers. However, recent advances are signaling a paradigm shift. The integration of artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning models, with high-throughput experimental validation is beginning to close this gap, moving the field from heuristic-driven exploration toward a more standardized, data-driven engineering discipline [30] [9]. This case study examines this transition through the lens of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, with a specific focus on evaluating how "zero-shot" predictors—computational models that make predictions without being specifically trained on the target system—are accelerating the quest for predictable success in binder design.

The Evolving DBTL Cycle: From DBTL to LDBT

The traditional DBTL cycle has long served as the foundational framework for engineering biological systems. In this paradigm, researchers Design a biological part, Build the DNA construct, Test its function experimentally, and Learn from the results to inform the next design round [1]. However, the integration of AI is fundamentally reshaping this workflow.

A proposed paradigm shift, termed "LDBT" (Learn-Design-Build-Test), places machine learning at the beginning of the cycle [1]. In this model, learning from vast biological datasets precedes design, enabling zero-shot predictions that generate functional protein sequences without requiring multiple iterative cycles. The emergence of this approach is made possible by protein language models (such as ESM and ProGen) and structure-based models (such as AlphaFold2 and ProteinMPNN) trained on evolutionary and structural data [1]. When combined with rapid Building and Testing phases powered by cell-free expression systems and biofoundries, this reordered cycle dramatically accelerates the development of functional proteins, inching closer to a "one design-one binder" ideal [1] [31].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference between the traditional cycle and the emerging AI-first approach.

Experimental Platforms and Methodologies

The reliability of any binder design assessment hinges on robust and consistent experimental methodologies. The transition toward more predictable design has been fueled by standardized validation protocols.

Key Experimental Assays for Validation

- Binding Affinity Measurement: Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) are widely used to quantify binding kinetics (KD) and affinity. For example, studies validating BindCraft and Latent-X designs utilized BLI/SPR to demonstrate nanomolar to picomolar affinities [31] [32].

- Functional Activity Assays: Depending on the target, these assays measure the binder's ability to modulate biological function. Examples include:

- Biophysical Characterization: Circular Dichroism (CD) for secondary structure analysis, Size Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) for assessing oligomeric state and stability, and Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) for measuring thermal stability (ΔTm) [31] [34].

High-Throughput Building and Testing

The "Build" and "Test" phases have been accelerated by adopting cell-free expression systems and biofoundries. Cell-free platforms leverage transcription-translation machinery in lysates, enabling rapid protein synthesis ( >1 g/L in <4 hours) without cloning [1]. This facilitates direct testing of thousands of designs. Biofoundries, such as the Illinois Biological Foundry for Advanced Biomanufacturing (iBioFAB), automate the entire DBTL cycle—from DNA construction and transformation to protein expression and functional assays—dramatically increasing throughput and reproducibility [35].

Comparative Analysis of De Novo Binder Design Platforms

The landscape of computational binder design is populated by diverse approaches, ranging from diffusion-based generative models to inverse folding and hallucination-based methods. The table below provides a structured comparison of leading platforms based on recent experimental validations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of De Novo Binder Design Platforms

| Platform / Method | Core Approach | Reported Success Rate | Typical Affinity Range | Key Experimental Validations |

|---|---|---|---|---|