CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing in Streptomyces: A Complete Guide for Natural Product Discovery and Optimization

This comprehensive guide explores the transformative role of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in Streptomyces research and industrial biotechnology.

CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing in Streptomyces: A Complete Guide for Natural Product Discovery and Optimization

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores the transformative role of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in Streptomyces research and industrial biotechnology. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a foundational understanding of why Streptomycetes are prime candidates for genetic engineering due to their complex genomes and prolific secondary metabolite production. The article details current methodologies, from plasmid design and transformation protocols to multiplex editing and large deletions, enabling precise manipulation of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). It addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for overcoming low editing efficiency and homologous recombination hurdles. Finally, it validates these techniques through comparative analysis with traditional methods, highlighting CRISPR's superiority in speed and precision for strain improvement and novel compound discovery. This resource synthesizes the latest advancements to empower efficient genome mining and engineering of these invaluable antibiotic-producing bacteria.

Why Edit Streptomyces? Unlocking the Genetic Potential of an Antibiotic Powerhouse

Streptomyces species are renowned for their complex, GC-rich genomes and their unparalleled capacity to produce bioactive secondary metabolites, including the majority of clinically used antibiotics. The core thesis of modern Streptomyces research posits that the systematic application of advanced genome editing tools, specifically CRISPR/Cas9 systems, is imperative to decode their complex genomics and unlock their vast, silent biosynthetic potential for novel drug discovery. This guide details the technical approaches enabling this research frontier.

Table 1: Key Genomic Features of Model Streptomyces Species

| Species | Genome Size (Mb) | GC Content (%) | Predicted Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) | RefSeq Assembly |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. coelicolor A3(2) | 8.67 | 72.1 | ~30 | GCF_000203835.1 |

| S. avermitilis MA-4680 | 9.03 | 70.7 | ~37 | GCF_000165735.1 |

| S. bingchenggensis BCW-1 | 11.94 | 70.8 | ~78 | GCF_000448525.1 |

| S. roseosporus NRRL 11379 | 6.72 | 70.4 | ~34 | GCF_001870945.1 |

Table 2: CRISPR/Cas9 Editing Efficiency in Streptomycetes (Recent Data)

| Target Locus (Species) | Editing Goal | Delivery Method | Efficiency Range | Key Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| actII-ORF4 (S. coelicolor) | Gene Knockout | Conjugative Plasmid | 90-100% | Use of pre-assembled Cas9:gRNA RNP |

| redD (S. coelicolor) | Point Mutation | ssDNA recombineering + CRISPR | 60-80% | Length of homology arms (≥80 bp) |

| PKS Module (S. albus) | Large Deletion (30 kb) | Integrative Plasmid | ~40% | Dual-gRNA targeting |

| Cryptic BGC (S. venezuelae) | Activation (Promoter Swap) | E. coli-Streptomyces Conjugation | 50-70% | Strong constitutive promoter choice (ermE*p) |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout in S. coelicolor via Conjugative Plasmid

- gRNA Design: Design a 20-nt spacer targeting the gene of interest using an online tool (e.g., CHOPCHOP). Ensure specificity via BLAST against the host genome. Append the 5'-G- for S. coelicolor σ70-like promoters if needed.

- Plasmid Construction: Clone the spacer into a Streptomyces CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid (e.g., pCRISPomyces-2) containing a Cas9 gene (codon-optimized), the gRNA scaffold, and a temperature-sensitive origin.

- Conjugative Transfer: Transform the plasmid into E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002. Mate with S. coelicolor spores on MS agar with 10 mM MgCl2 at 30°C for 9-16 hours.

- Selection & Screening: Overlay with agar containing apramycin (plasmid selection) and nalidixic acid (counterselection against E. coli). Incubate at 30°C for 3-5 days.

- Curing: Pick exconjugants and propagate at 37°C (non-permissive temperature for plasmid replication) without antibiotic to cure the plasmid. Verify knockout via PCR and sequencing.

Protocol 2: CRISPRi for Repression of Biosynthetic Pathway Regulators

- Design: Design gRNA to target the template strand of the promoter or early coding region of a pathway-specific activator gene (e.g., pathR).

- System Assembly: Utilize a plasmid expressing a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to a transcriptional repressor domain (e.g., Mxi1) under a strong constitutive promoter.

- Integration: Introduce the plasmid via conjugation and integrate it site-specifically into a phage attachment site (e.g., attB site) for stable inheritance.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Compare metabolite production (e.g., via HPLC-MS) of the CRISPRi strain against the wild-type control to assess pathway repression.

Mandatory Visualizations

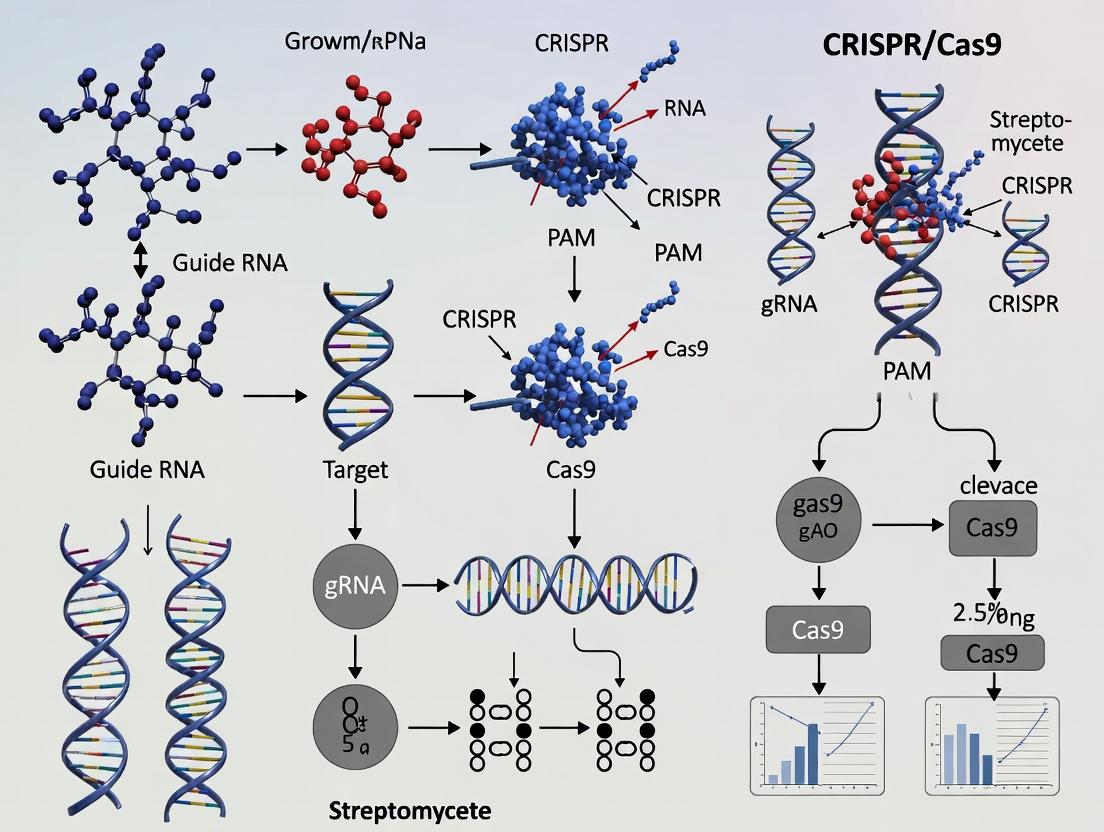

CRISPR/Cas9 Editing Workflow in Streptomyces

CRISPRa Activation of a Silent Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Streptomyces CRISPR Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| pCRISPomyces-2 Plasmid | A standard E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector with codon-optimized Cas9, temperature-sensitive replicon, and apramycin resistance. |

| E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 | Non-methylating, conjugation-competent donor strain essential for efficient plasmid transfer into Streptomyces. |

| Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) with 0.1% Tween 80 | Spore wash and germination solution; Tween 80 reduces clumping for consistent conjugation. |

| Apramycin (50 µg/mL) | Antibiotic for selection of Streptomyces exconjugants containing the CRISPR plasmid. |

| Nalidixic Acid (25 µg/mL) | Antibiotic for counterselection against the E. coli donor strain post-conjugation. |

| HR Donor DNA (ssDNA/dsDNA) | Homologous repair template for introducing precise mutations or inserting new sequences after Cas9 cleavage. |

| dCas9-Repressor/Activator Plasmids | For CRISPRi (knockdown) or CRISPRa (activation) studies to fine-tune gene expression without cleavage. |

| Mycelium Lysis Kit (Lysozyme + Proteinase K) | For high-quality genomic DNA extraction necessary for post-editing verification (PCR, sequencing). |

Within the broader thesis on CRISPR/Cas9 applications in streptomycete genome editing, this whitepaper details the transformative journey from classical, untargeted genetic manipulation to the current era of precision genome engineering. Streptomyces spp., the prolific producers of antibiotics and other bioactive natural products, have long been genetically intractable. The advent of CRISPR/Cas9 and derivative systems has revolutionized their genetic analysis and metabolic engineering, enabling targeted multiplexed edits, transcriptional modulation, and high-throughput functional genomics.

Historical Context: The Random Mutagenesis Era

Classical strain improvement relied on random mutagenesis using physical (UV, gamma radiation) or chemical (NTG, EMS) agents, followed by phenotypic screening. While successful for industrial scaling, this approach lacked precision, often introducing undesirable secondary mutations and offering no mechanistic insight.

Table 1: Comparison of Historical Mutagenesis Methods

| Method | Agent | Typical Mutation Rate | Primary Lesion | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV Irradiation | Ultraviolet Light | ~0.1-1% survivors | Pyrimidine dimers | Poor penetration, photo-reactivation |

| Chemical (NTG) | N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine | ~0.5-2% mutants | Alkylation (O⁶-guanine) | Highly toxic, requires careful neutralization |

| EMS | Ethyl methanesulfonate | ~1-5% mutants | Alkylation (Guanine) | High background of unrelated mutations |

Protocol 1: Classical NTG Mutagenesis of Streptomyces

- Culture Preparation: Grow the Streptomyces strain in a rich liquid medium (e.g., TSB) to mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ~0.5).

- Harvest and Wash: Pellet mycelia/spores by centrifugation (3000 × g, 10 min). Wash twice with 0.1 M Tris-maleate buffer (pH 9.0).

- Mutagen Treatment: Resuspend in the same buffer to ~10⁸ CFU/mL. Add NTG from a fresh stock (1 mg/mL in acetone) to a final concentration of 50-100 µg/mL. Incubate at 30°C with shaking for 30-60 min.

- Neutralization and Wash: Pellet cells, carefully discard supernatant as hazardous waste. Resuspend in 5% sodium thiosulfate to neutralize residual NTG. Wash twice with sterile buffer.

- Outgrowth and Plating: Dilute and plate on non-selective medium for survivor count and on selective medium for mutant isolation. Incubate at 30°C for 3-7 days.

- Mutant Screening: Isolate colonies and screen for desired phenotype (e.g., antibiotic overproduction).

The Recombinant DNA Revolution

The development of plasmid vectors, phage-based delivery systems (e.g., φC31, VWB), and homologous recombination techniques (e.g., PCR-targeting with λ-RED in E. coli) enabled targeted gene knockouts and heterologous expression. However, these methods were often multi-step, time-consuming, and inefficient, especially for streptomycetes with low natural recombination frequencies.

The CRISPR/Cas9 Precision Era

The adaptation of the Type II Streptococcus pyogenes CRISPR/Cas9 system has provided a quantum leap in Streptomyces genetic engineering, allowing for single-base resolution edits, multiplexing, and transcriptional control.

Core Mechanism and Delivery

The Cas9 endonuclease is guided by a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to a specific genomic locus, where it creates a double-strand break (DSB). In the absence of a repair template, error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) leads to indels and gene disruption. When co-delivered with a homologous repair template (donor DNA), high-fidelity homology-directed repair (HDR) enables precise edits.

Diagram 1: CRISPR/Cas9 Editing Workflow in Streptomyces (Max 760px)

Protocol 2: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout in S. coelicolor

- sgRNA Design: Using a target sequence (20-nt, 5'-NGG PAM), design oligonucleotides. Clone into a Streptomyces CRISPR plasmid (e.g., pCRISPomyces-2) downstream of a constitutive promoter via Golden Gate or Gibson assembly.

- Vector Construction: Verify plasmid sequence. For conjugation, the plasmid must contain an oriT and an appropriate antibiotic marker (apramycin resistance).

- Conjugal Transfer: a. Prepare electrocompetent E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 (methylation-deficient, carrying conjugation helper functions). b. Transform the CRISPR plasmid into this E. coli strain. c. Mix the E. coli donor with S. coelicolor spores (heat-shocked at 50°C for 10 min) on an SFM plate. Incubate at 30°C for 16-20h. d. Overlay plate with 1 mL water containing nalidixic acid (to counter-select E. coli) and apramycin (to select for Streptomyces exconjugants). Incubate for 3-5 days.

- Screening and Curing: Isolate exconjugants. Screen for desired deletions via colony PCR. To cure the plasmid, streak colonies onto non-selective medium and screen for apramycin-sensitive clones.

Advanced CRISPR Tools

- Base Editing: Fusion of catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) with a deaminase enzyme (e.g., APOBEC1) enables C•G to T•A conversions without requiring a DSB or donor DNA.

- CRISPRi/a: dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressors (e.g., KRAB) or activators (e.g., SoxS) allows for targeted gene knockdown (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa).

- Multiplexed Editing: Delivery of arrays of multiple sgRNAs enables simultaneous manipulation of several genomic loci, crucial for engineering biosynthetic gene clusters.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Modern Streptomyces Genome Editing Tools

| Tool | System | Editing Efficiency (Typical Range) | Time to Verified Mutant (Days) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 (KO) | pCRISPomyces-2 | 50-100% | 7-14 | Single gene disruption |

| CRISPR/Cas9 (HDR) | pCRISPR-Cas9* | 10-60%* | 14-21 | Precise allele replacement |

| Base Editor (CBE) | pBAC-bEC | 30-90% | 10-18 | Point mutations without DSB |

| CRISPRi | dCas9-Sox4 | 70-95% repression | 7-10 | Tunable gene knockdown |

*Efficiency highly dependent on donor design and homology arm length (optimal: 1 kb each side).

Diagram 2: CRISPR Tool Derivations and Key Applications (Max 760px)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Streptomyces CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Function & Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| pCRISPomyces-2 Plasmid | Addgene (#61737) | All-in-one Streptomyces CRISPR/Cas9 vector; contains cas9, sgRNA scaffold, and tracrRNA. |

| dCas9-pCRISPomyces-2 | Addgene (#141732) | Catalytically dead Cas9 variant for CRISPRi/a studies. |

| E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 | Laboratory stocks | Methylation-deficient E. coli donor strain for intergeneric conjugation. |

| S. coelicolor A3(2) | DSMZ / John Innes Centre | Model organism with well-annotated genome; ideal for protocol optimization. |

| BTX Electroporator & 2mm Cuvettes | Harvard Apparatus | Alternative delivery method for plasmids into Streptomyces protoplasts. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | NEB / Thermo Fisher | For seamless assembly of donor DNA with long homology arms into vectors. |

| Streptomyces Specific Media (SFM, MS, R5) | Formulated in-house or commercial | Optimized for growth, sporulation, and conjugation efficiency. |

| Apramycin Sulfate | Sigma-Aldrich | Common selective antibiotic for Streptomyces (typically 50 µg/mL in plates). |

| Nalidixic Acid | Sigma-Aldrich | Used in conjugation to counterselect against the E. coli donor strain (25 µg/mL). |

| Phire Plant Direct PCR Master Mix | Thermo Fisher | Enables rapid colony PCR from tough Streptomyces mycelia/spores. |

The evolution from random mutagenesis to CRISPR-driven precision tools has fundamentally reshaped Streptomyces genetic engineering. These advances, central to the thesis on CRISPR/Cas9 applications, now permit hypothesis-driven research, rational metabolic engineering, and accelerated drug discovery pipelines. Future integration of machine learning for sgRNA design and automation for high-throughput editing will further solidify Streptomyces as a premier chassis for natural product discovery and development.

This guide details the core principles of implementing CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing in bacteria, with a specific focus on the genetically complex and industrially vital Streptomyces genus. Efficient genome editing in streptomycetes is pivotal for engineering novel antibiotic and secondary metabolite pathways, a central theme in modern drug discovery research. The fundamental requirements—precise gRNA design and selection of appropriate Cas9 variants—are critical for success in these high-GC-content, often polyploid, actinobacteria.

Fundamentals of gRNA Design for Bacterial Systems

Effective gRNA design is the first critical step. For streptomycetes, specific adaptations from standard bacterial protocols are required.

Core Principles:

- Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) Specificity: The Cas9 variant dictates the PAM sequence requirement, which must be present in the target genomic DNA. The canonical S. pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) requires a 5'-NGG-3' PAM downstream of the target.

- Target Sequence Selection: The 20-nt spacer sequence immediately 5' to the PAM must be unique within the host genome to minimize off-target effects.

- gRNA Scaffold: The non-complementary, structural portion of the guide RNA is essential for Cas9 binding and nuclease activation.

Streptomycete-Specific Considerations:

- High GC-content: Spacer sequences should be designed with a GC content between 40-80%, favoring the higher end for Streptomyces (genomic GC ~70-74%), to ensure stable DNA:RNA hybridization.

- Secondary Structure: The gRNA, especially its spacer region, should be free of significant internal hairpins that could impede Cas9 binding. Tools like UNAFold or mFold are used for analysis.

- Genomic Copy Number: For targets in multi-copy genomic regions (e.g., rRNA genes), longer homology arms in repair templates are advised.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for gRNA Design in Streptomyces

| Parameter | Optimal Range / Target | Rationale for Streptomycetes |

|---|---|---|

| Spacer Length | 20 nucleotides (nt) | Standard for SpCas9; can be truncated to 18-19 nt for increased specificity. |

| GC Content | 50-75% | Higher stability in high-GC genomic context; avoid extremes. |

| On-Target Score | >50 (tool-dependent) | Predicts cleavage efficiency (e.g., using CRISPRscan, DeepCRISPR). |

| Off-Target Score | <3 potential sites with ≤3 mismatches | Ensures specificity; use BLAST against the host genome. |

| PAM Proximity | Close to edit site | For HDR, the edit should be within 10-15 bp of the PAM for high efficiency. |

Experimental Protocol: In Silico gRNA Design and Validation

- Identify Target Locus: Obtain the precise genomic sequence of the target region from a trusted database (e.g., GenBank for S. coelicolor).

- Scan for PAM Sites: Using a script or tool (e.g., Benchling, CRISPRfinder), identify all 5'-NGG-3' sequences in both strands within your locus of interest.

- Extract Spacer Candidates: Select the 20-nt sequence directly upstream of each PAM.

- Evaluate Specificity: Perform a BLASTN search of each candidate spacer against the complete genome of your streptomycete host. Reject any spacer with >90% identity over 15+ nt to other genomic locations.

- Calculate Efficiency Scores: Input selected spacer sequences into a prediction algorithm (e.g., CRISPOR, CHOPCHOP) to rank them by predicted on-target activity.

- Check Secondary Structure: Model the full gRNA (spacer + scaffold) sequence to ensure the spacer region is accessible.

Cas9 Variants for Bacterial Genome Editing

While wild-type SpCas9 is common, its use in bacteria, particularly for streptomycete engineering where precise editing is paramount, is often supplanted by engineered variants.

Key Variants and Their Applications:

- Wild-Type SpCas9: Generates a blunt-ended double-strand break (DSB) 3 bp upstream of the PAM. Can be used for gene knockouts via error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), though NHEJ is inefficient in most Streptomyces.

- Cas9 D10A (Nickase): A single-strand nicking variant. Used in pairs with offset PAMs to create staggered DSBs, reducing off-target effects by >1000-fold. Essential for precise editing in streptomycetes.

- Dead Cas9 (dCas9): Catalytically inactive. Used for transcriptional repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) when fused to effector domains, crucial for modulating secondary metabolite clusters without altering DNA sequence.

- High-Fidelity Variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9): Contain mutations that reduce non-specific electrostatic interactions with the DNA backbone. They exhibit drastically reduced off-target activity with minimal loss of on-target efficiency, ideal for multiplexed edits in large genomes.

- PAM-Relaxed Variants (e.g., SpCas9-NG, xCas9): Recognize broader PAM sequences (e.g., NG, GAA), vastly expanding the targetable genomic space, beneficial for AT-rich regions within streptomycete genomes.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Cas9 Variants for Streptomycete Editing

| Variant | Key Mutations | PAM | Primary Application in Streptomyces | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type SpCas9 | None | NGG | Gene knockout (with NHEJ machinery), plasmid curing. | Simplicity, high on-target activity. |

| Cas9 D10A (Nickase) | D10A | NGG | Precise HDR editing using paired nickases. | Drastically reduced off-target cleavage. |

| dCas9 | D10A, H840A | NGG | CRISPRi/a for gene expression modulation. | No DNA cleavage; reversible knockdown. |

| SpCas9-HF1 | N497A, R661A, Q695A, Q926A | NGG | High-accuracy multiplex editing of biosynthetic gene clusters. | Ultra-high specificity. |

| SpCas9-NG | R1335V, L1111R, D1135V, G1218R, E1219F, A1322R, T1337R | NG | Targeting AT-rich regions within high-GC genomes. | Expanded targeting range (~4x more sites). |

Experimental Protocol: HDR-Mediated Gene Editing inStreptomycesusing Cas9 Nickase

This protocol outlines a standard two-plasmid system for precise allele replacement.

Materials:

- pCRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid: Contains a Streptomyces codon-optimized cas9 (D10A nickase), a gRNA scaffold, and a temperature-sensitive origin of replication.

- pDonor Plasmid: Contains the homology-directed repair (HDR) template with desired edits, flanked by ~1 kb homology arms.

- Conjugative E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002: Donor strain for intergeneric conjugation.

- Streptomyces Spores: Recipient strain.

- Selection Antibiotics: Apramycin (for pCRISPR), Kanamycin (for pDonor), Nalidixic acid (counter-selection for Streptomyces).

Method:

- Clone gRNA: Anneal and ligate oligonucleotides encoding the target-specific 20-nt spacer into the BsaI site of the pCRISPR-Cas9 plasmid.

- Clone HDR Template: PCR-amplify the homology arms and assemble them with the mutated sequence into the pDonor plasmid via Gibson Assembly.

- Transform Donor E. coli: Co-transform the constructed pCRISPR and pDonor plasmids into the methylation-deficient E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002. Select on LB agar with Apramycin and Kanamycin.

- Intergeneric Conjugation: Mix the donor E. coli with Streptomyces spores. Plate on MS agar, incubate at 30°C for 16-20 hours. Overlay with Apramycin (to select for exconjugants) and Nalidixic acid (to counter-select E. coli). Incubate at 30°C for 5-7 days.

- Curing of Plasmids: Pick exconjugants and propagate at 37°C (non-permissive temperature for plasmid replication) without antibiotics for several rounds. Screen for Apramycin- and Kanamycin-sensitive colonies.

- Genotype Verification: Confirm the edit via colony PCR and Sanger sequencing of the target locus.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR/Cas9 Editing in Streptomycetes

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Codon-Optimized Cas9 Expression Plasmid | Expresses Cas9 variant efficiently in high-GC actinobacteria. | Plasmid with Streptomyces rpsL promoter, thiostrepton-inducible. |

| gRNA Expression Backbone | Provides the structural scaffold for the custom spacer. | Contains a strong, constitutive promoter (e.g., ermE). |

| Temperature-Sensitive Origin | Allows for easy plasmid curing after editing. | pSG5-based or pKC1139-based replicons. |

| Methylation-Deficient E. coli | Enables efficient conjugation into Streptomyces by avoiding host restriction systems. | ET12567 (dam-/dem-/hsdM-). |

| Conjugative Helper Plasmid | Provides transfer functions (tra genes) for mobilizing plasmids from E. coli. | pUZ8002 (non-integrative, Kan^R). |

| Homology-Directed Repair Template | DNA template for precise repair of Cas9-induced DSB. | Can be delivered on a plasmid or as a linear dsDNA fragment (1-2 kb arms). |

| Selection/Counter-Selection Agents | Selects for exconjugants and against donor E. coli. | Apramycin (selection), Nalidixic acid (counter-selection). |

| Inducer for Regulated Expression | Tightly controls Cas9/gRNA expression to limit toxicity. | Thiostrepton (for tipA promoter) or Anhydrotetracycline (for tet promoters). |

Diagrams

Title: CRISPR/Cas9 Workflow for Streptomyces Genome Editing

Title: DNA Repair Pathways After Cas9 Cleavage

This whitepaper, framed within the broader thesis of advancing CRISPR/Cas9 applications in streptomycete genome editing, details the principal technical barriers of host Restriction-Modification (R-M) systems and inherently low transformation efficiencies. We provide a comprehensive technical guide with current (as of 2024) strategies, quantitative data comparisons, and detailed protocols to overcome these challenges, enabling robust genetic manipulation in these industrially critical, GC-rich bacteria for drug discovery.

Streptomyces species are prolific producers of antibiotics and other pharmaceuticals but are notoriously recalcitrant to genetic manipulation. Two intertwined challenges dominate:

- Restriction-Modification (R-M) Systems: These innate bacterial defense systems recognize and cleave incoming foreign DNA (e.g., plasmid vectors), drastically reducing transformation success.

- Low Transformation Efficiency: Even when R-M systems are bypassed, classic methods like PEG-mediated protoplast transformation yield low numbers of transformants, hindering complex multiplexed CRISPR editing.

Overcoming these hurdles is essential for leveraging CRISPR/Cas9 to engineer biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for novel drug development.

In-Depth Analysis of Restriction-Modification Systems

Streptomycetes often possess multiple Type I, II, and IV R-M systems. Current internet research confirms the primary strategy is to evade or temporarily disable these systems.

Quantitative Comparison of R-M Bypass Strategies

Table 1: Strategies to Overcome R-M Systems in Streptomycetes

| Strategy | Mechanism | Relative Efficiency Increase* | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro DNA Methylation | Mimics host methylation patterns using methyltransferase enzymes (e.g., phage-derived Φ31, TuZI). | 10 - 10,000x | Direct, applicable to any strain. | Requires prior knowledge of host R-M systems; cost of enzymes. |

| Use of Restriction-Deficient Mutants | Employ mutant host strains (e.g., S. coelicolor ΔhsdMS, S. albus ΔresΔmod) as intermediates. | 100 - 100,000x | Highly effective for cloning; enables conjugation from E. coli. | Requires construction/availability of mutant; extra cloning step. |

| Conjugation from E. coli (ET12567/pUZ8002) | Delivers plasmid as single-stranded DNA, less recognizable by R-M systems. | 50 - 1,000x | Bypasses many systems; no protoplast preparation needed. | Requires biparental mating; potential for uncontrolled spread. |

| CRISPR-Aided R-M Gene Knockout | Use CRISPR/Cas9 to delete key restriction (hsdR) or methylase (hsdM) genes in the target strain. | Permanent solution | Permanently removes the barrier for future edits. | Initial transformation to deliver CRISPR machinery remains challenging. |

*Efficiency increase is highly strain-dependent and reported relative to unmethylated DNA transformation in wild-type strains.

Detailed Protocol: In Vitro Methylation and Transformation

This protocol uses commercially available methyltransferases.

Materials:

- Purified plasmid DNA (1-2 µg) for transformation.

- CpG Methyltransferase (M.SssI) or specific phage Methyltransferase (e.g., M.Φ31T from commercial suppliers).

- Corresponding S-Adenosyl methionine (SAM).

- Appropriate reaction buffer.

- PEG-assisted protoplast transformation reagents for streptomycetes.

Method:

- Methylation Reaction: Set up a 50 µL reaction containing 1x reaction buffer, 1 µg plasmid DNA, 160 µM SAM, and 4 units of methyltransferase. Incubate at 30°C (for phage enzymes) or 37°C (for M.SssI) for 4 hours.

- Enzyme Inactivation: Heat-inactivate at 65°C for 20 minutes.

- Precipitation: Ethanol-precipitate the DNA, wash with 70% ethanol, and resuspend in 10 µL TE buffer.

- Transformation: Use the methylated DNA immediately in your standard streptomycete protoplast transformation protocol. Include an unmethylated plasmid control.

Addressing Low Transformation Efficiency

High-efficiency transformation is critical for obtaining the rare double-crossover events needed for precise CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene replacements.

Quantitative Comparison of Efficiency-Enhancing Methods

Table 2: Methods to Improve Transformation Efficiency in Streptomycetes

| Method | Core Principle | Typical CFU/µg DNA* | Suitability for CRISPR Editing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PEG-Protoplast | Cell wall removal, PEG-mediated DNA uptake. | 10^2 - 10^4 | Low; often insufficient for screening CRISPR edits. |

| Intergeneric Conjugation | Plasmid transfer from E. coli via mating pore. | 10^3 - 10^5 | High; preferred method for initial CRISPR plasmid delivery. |

| Electrical Transformation of Mycelia | Electroporation of germinated spores/mycelia. | 10^3 - 10^5 | Moderate; requires strain-specific optimization of pulse parameters. |

| Chemically Competent Cell Transformation | Treatment of young mycelia with divalent cations and PEG. | 10^4 - 10^6 | Very High; emerging as the most effective method for plasmid DNA. |

*CFU = Colony Forming Units. Ranges are strain-dependent.

Detailed Protocol: High-Efficiency Chemically Competent Cell Transformation

Adapted from recent (2023) publications for S. coelicolor and S. lividans.

Materials:

- SMM Buffer: 0.5M Sucrose, 20mM Maleic Acid, 20mM MgCl2, pH 6.5.

- P Buffer: SMM Buffer supplemented with 5% (v/v) PEG 6000.

- 2xYT Medium: Standard yeast extract-tryptone medium.

- Mannitol-Soy Flour (MS) Agar.

Method:

- Culture Growth: Inoculate spores into 2xYT medium with 10% sucrose. Grow for 24-36h at 30°C until late-exponential phase (hyphal clumps visible).

- Mycelia Preparation: Harvest mycelia by gentle centrifugation (2000-3000 x g, 10 min). Wash twice with 10% sucrose.

- Competent Cell Preparation: Resuspend the washed mycelial pellets in P Buffer (1 mL per 50mL original culture). Incubate at 30°C for 1 hour. The mycelia are now competent.

- Transformation: Aliquot 100 µL of competent mycelia into a tube. Add 100-500 ng of plasmid DNA (optimally methylated). Mix gently and incubate at 30°C for 5 minutes.

- Regeneration: Add 900 µL of P Buffer and mix. Plate the entire mixture onto MS agar plates containing 10% sucrose (and appropriate antibiotics). Incubate at 30°C for 12-24 hours before overlaying with soft agar containing antibiotics to select for transformants.

Integrated Workflow and Visual Guides

Title: Integrated Workflow for CRISPR Delivery in Streptomycetes

Title: R-M System Action and Bypass Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Streptomycete CRISPR Genome Editing

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Product / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Phage-Derived Methyltransferases | Methylates plasmid DNA in vitro to evade specific host R-M systems. | M.Φ31T, M.ΦBT1, M.ΦC31 (commercial kits available). |

| CpG Methyltransferase (M.SssI) | Methylates all cytosine residues in a CpG context; broadly protects against many Type II systems. | New England Biolabs M0226S. |

| E. coli Donor Strain ET12567/pUZ8002 | A non-methylating, conjugation-helper strain for intergeneric mating with Streptomyces. | Widely available from research culture collections. |

| pCRISPomyces-2 Vector | A specifically designed, shuttle plasmid for CRISPR/Cas9 editing in Streptomyces. | Addgene Plasmid #61737. |

| pKCcas9dO Vector | A temperature-sensitive, "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) vector for CRISPR interference (CRISPRi). | Addgene Plasmid #125595. |

| S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAM) | Essential methyl donor cofactor for all in vitro methylation reactions. | Supplied with methyltransferase kits. |

| High-Purity PEG 6000 / 1000 | Critical for inducing membrane fusion during protoplast and chemical transformation. | Sigma-Aldrich 81170 (PEG 1000). |

| Mycelial Protoplasting Enzymes | Lysozyme and other lytic enzymes for cell wall removal in protoplast preparation. | Lysozyme from chicken egg white (Sigma L6876). |

| Sucrose & MgCl2 | Osmotic stabilizers in transformation buffers (SMM, P Buffer) to prevent protoplast lysis. | Standard laboratory reagents. |

| Thiostrepton & Apramycin | Common selectable antibiotics for Streptomyces genetics and CRISPR plasmid maintenance. | Sigma T8902 (Thiostrepton). |

Protocols in Practice: Step-by-Step CRISPR/Cas9 Workflows for Streptomyces Engineering

The development of efficient CRISPR/Cas9 systems for Streptomyces has been pivotal in unlocking the genetic potential of these prolific antibiotic producers. A central decision in experimental design is the choice of plasmid delivery system: integrating or replicating. This guide, framed within a broader thesis on advancing CRISPR/Cas9 tools for streptomycete metabolic engineering and natural product discovery, provides a technical comparison of two seminal vectors: the integrating pCRISPomyces systems and the temperature-sensitive replicating pKCcas9dO.

pCRISPomyces (Integrating System)

The pCRISPomyces plasmids (e.g., pCRISPomyces-1, -2) are E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vectors that integrate site-specifically into the attB site of the Streptomyces chromosome via the ΦBT1 integrase. They are maintained as single-copy, stable genetic elements.

pKCcas9dO (Replicating System)

The pKCcas9dO plasmid is a derivative of the pKC1139-based vectors. It contains a temperature-sensitive origin of replication (pSG5) that allows for plasmid replication at permissive temperatures (∼28-30°C) and facilitates plasmid curing at non-permissive temperatures (∼37-39°C), enabling the creation of marker-free strains.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Comparison of Plasmid Systems

| Feature | pCRISPomyces (Integrating) | pKCcas9dO (Replicating) |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid Backbone | pCRISPomyces-1/2 | pKC1139 derivative |

| Replication in Streptomyces | Chromosomal integration (ΦBT1 attB/int) | Temperature-sensitive (pSG5 ori) |

| Copy Number in Streptomyces | Single (integrated) | Low-copy, unstable at >37°C |

| Selection Marker | Apramycin (aac(3)IV) | Apramycin (aac(3)IV) |

| Key Components | codon-optimized cas9, sgRNA scaffold, tracrRNA | codon-optimized cas9, sgRNA expression cassette |

| Primary Advantage | Genetic stability, suitable for long-term/fermentation studies | Easy curing, rapid iterative editing, marker-free final strains |

| Primary Limitation | Permanent marker, requires recombinase for excision | Instability during extended culture, requires temperature control |

| Typical Editing Efficiency* | 30-100% for gene knockouts | 50-100% for gene knockouts |

| Key Reference | Cobb et al. (2015) ACS Synth. Biol. | Zeng et al. (2018) Metab. Eng. |

*Efficiency is highly dependent on the target locus, sgRNA design, and host strain.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Genome Editing Using pCRISPomyces-2

This protocol outlines the construction of a gene knockout in Streptomyces coelicolor.

Materials:

- E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 (non-methylating conjugal donor)

- Streptomyces sp. target strain

- pCRISPomyces-2 plasmid

- Primers for sgRNA template amplification and homology-directed repair (HDR) template assembly.

- Apramycin (50 µg/mL for E. coli, 50 µg/mL for Streptomyces), Carbenicillin (100 µg/mL), Kanamycin (50 µg/mL).

Method:

- sgRNA Design & Cloning:

- Design a 20-nt target-specific sequence (N20) adjacent to a 5'-NGG-3' PAM.

- Amplify the sgRNA expression cassette using pCRISPomyces-2 as template and primers containing the N20 overhangs (Forward: 5'-GGTGN20GTTTA-3', Reverse: 5'-AAACN20reversecomplementC-3').

- Perform Golden Gate assembly using BsaI-HFv2 into the BsaI-digested pCRISPomyces-2 plasmid.

- Transform into E. coli and select on Apramycin/Carbenicillin plates. Sequence-verify the insert.

HDR Template Construction:

- For a clean deletion, PCR-amplify ∼1 kb upstream and downstream flanking regions of the target gene.

- Assemble these fragments into a linear dsDNA HDR template via overlap extension PCR. Ensure the final product contains no PAM site or protospacer sequence.

Conjugal Transfer & Exconjugant Selection:

- Introduce the verified pCRISPomyces-2 plasmid into E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002.

- Grow donor and recipient (Streptomyces spores) separately, mix, and plate on MS agar with 10 mM MgCl2.

- After 16-20h at 30°C, overlay with sterile water containing Apramycin (final 50 µg/mL) and Nalidixic Acid (final 25 µg/mL) to inhibit E. coli.

- Incubate at 30°C until exconjugant colonies appear (5-10 days).

Screening & Verification:

- Patch exconjugants onto Apramycin plates. Screen for desired mutants via colony PCR using verification primers outside the HDR template region.

- Successful integration of the HDR template results in apramycin-sensitive candidates (as the aac(3)IV marker is not integrated).

- Validate by sequencing the target locus.

Protocol: Iterative Editing Using pKCcas9dO

This protocol enables rapid, sequential gene edits without permanent antibiotic markers.

Materials:

- pKCcas9dO plasmid.

- E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002.

- Streptomyces sp. target strain.

- Standard molecular biology reagents.

Method:

- Plasmid Construction:

- Clone the designed sgRNA expression cassette (target N20 + scaffold) into the BsaI site of pKCcas9dO. The sgRNA is expressed from a constitutive promoter (ermE*p).

- If using an HDR template for precise editing, clone it as a dsDNA fragment into a unique restriction site (e.g., PacI) located adjacent to the sgRNA cassette.

Conjugation & Primary Editing:

- Perform intergeneric conjugation as described in Section 3.1, Step 3.

- Plate conjugations on apramycin-containing medium and incubate at 30°C (permissive temperature) for exconjugant growth.

- Isolate single colonies and culture in liquid medium with apramycin at 30°C.

Plasmid Curing & Strain Purification:

- Take a sample from the primary mutant culture and streak for single colonies on non-selective medium (no antibiotic).

- Incubate at 37-39°C (non-permissive temperature) for 1-2 generations.

- Patch resulting colonies onto plates with and without apramycin. Select colonies that are apramycin-sensitive, indicating loss of the pKCcas9dO plasmid.

- Verify genotype of the cured, edited strain by PCR/sequencing.

Iterative Editing Cycle:

- Use the cured, marker-free mutant as the recipient for the next round of conjugation with a new pKCcas9dO plasmid harboring the next sgRNA/HDR template.

- Repeat steps 2 and 3.

Visual Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR/Cas9 Editing in Streptomyces

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| pCRISPomyces-2 Plasmid | Integrating vector backbone. Contains cas9, sgRNA scaffold, and apramycin resistance for selection in Streptomyces. | Available from Addgene (#61737). |

| pKCcas9dO Plasmid | Temperature-sensitive replicating vector backbone. Enables plasmid curing for marker-free strains. | Derived from pKC1139, contains pSG5 ori. |

| E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 | Non-methylating, conjugative donor strain. Essential for efficient plasmid transfer from E. coli to Streptomyces. | pUZ8002 provides tra genes for mobilization. |

| BsaI-HFv2 Restriction Enzyme | For Golden Gate assembly of sgRNA expression cassettes into pCRISPomyces/pKCcas9dO. | High-fidelity version prevents star activity. |

| Apramycin Sulfate | Antibiotic for selection of plasmid-bearing E. coli and Streptomyces exconjugants. | Working concentration: 50 µg/mL for both. |

| Nalidixic Acid | Counterselection agent against the E. coli donor strain during conjugation. | Used in overlay at 25-50 µg/mL. |

| MS Agar | A defined medium optimal for conjugation between E. coli and Streptomyces. | Contains mannitol and soy flour. |

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | For error-free amplification of HDR templates and verification PCRs. Critical for large fragment assembly. | Reduces introduction of unwanted mutations. |

| PCR Clean-Up/Gel Extraction Kit | For purification of DNA fragments during sgRNA cloning and HDR template preparation. | Essential for high-efficiency assemblies. |

| Temperature-Controlled Incubators | Critical for pKCcas9dO system: 30°C for plasmid maintenance, 37-39°C for plasmid curing. | Requires accurate temperature control. |

This guide is framed within the thesis: "Advancing Natural Product Discovery through Precision CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Engineering in Streptomycetes." Streptomycetes are prolific producers of bioactive secondary metabolites encoded by Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs). The application of CRISPR/Cas9 for targeted gene knockout or CRISPRa for activation is revolutionizing the activation of silent BGCs and the functional analysis of essential genes in this genus, accelerating drug development pipelines.

Principles of gRNA Design for Streptomycetes

Effective gRNA design must account for the high GC-content (often >70%) and unique genomic architecture of streptomycetes.

- Target Selection: For BGC knockout, target core biosynthetic genes (e.g., polyketide synthases, non-ribosomal peptide synthetases). For activation (CRISPRa), target promoter regions upstream of BGCs or pathway-specific regulators. For essential gene knockout, use a complementation strategy.

- Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): For standard Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3'. PAM must be present on the genomic DNA, not on the gRNA.

- gRNA Length: 20 nucleotides upstream of the PAM.

- Specificity: Perform BLAST against the host genome (e.g., S. coelicolor, S. avermitilis) to minimize off-target effects. Mismatches in the "seed region" (8-12 bases proximal to PAM) are most critical for specificity.

- Efficiency Prediction: Tools like Benchling or CHOPCHOP, adjusted for high GC-content, can predict on-target efficiency scores.

Table 1: Key Parameters for gRNA Design in High-GC Streptomycetes

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Rationale & Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 50-70% | Balances stability and specificity; avoid extreme highs (>80%). |

| On-Target Score | >60 (Tool-dependent) | Higher scores correlate with increased cleavage/activation efficiency. |

| Off-Target Score | Max 3-4 mismatches, especially in seed region | Minimizes unintended genomic edits. Essential for essential genes. |

| PAM for SpCas9 | 5'-NGG-3' | Must be present immediately downstream of target. |

| gRNA Length | 20 nt (spacer) + scaffold | Standard for SpCas9. |

| Self-Complementarity | Avoid hairpins in spacer | Prevents gRNA misfolding. |

Cloning Strategies for gRNA Expression Vectors

Streptomycetes often utilize plasmid-based systems with constitutive (e.g., ermEp) or inducible promoters for gRNA expression.

Protocol 1: Golden Gate Assembly for Multiplex gRNA Cloning This method allows assembly of multiple gRNA expression cassettes into a single E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector.

- Design Oligos: For each gRNA, design two oligonucleotides:

- Top strand: 5'-GGGC[20-nt target sequence]-3'

- Bottom strand: 5'-AAAC[reverse complement of target]-3' (The overhangs are compatible with BsaI-digested vector.)

- Phosphorylate & Anneal: Mix 1 µL of each oligo (100 µM), 1 µL T4 PNK, 1 µL 10x T4 Ligation Buffer, 6.5 µL H₂O. Incubate: 37°C for 30 min; 95°C for 5 min; ramp down to 25°C at 5°C/min.

- Golden Gate Reaction: Mix 50 ng BsaI-digested destination vector (e.g., pCRISPomyces-2), 1 µL diluted annealed duplex (1:200), 1 µL T4 DNA Ligase, 1 µL BsaI-HFv2, 2 µL 10x T4 Ligase Buffer, H₂O to 20 µL.

- Thermocycle: 30 cycles of (37°C for 5 min, 16°C for 5 min), then 50°C for 5 min, 80°C for 5 min.

- Transform: Transform 5 µL reaction into competent E. coli, plate on appropriate antibiotic. Verify by colony PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Protocol 2: Site-Directed Cloning into a Streptomyces CRISPRa Vector For activation, gRNA must be cloned into a vector expressing a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) fused to an activator domain (e.g., Sox2, Mxi1).

- PCR Amplify gRNA Scaffold: Using a template plasmid, amplify the gRNA expression cassette with primers containing homology arms to the target locus in the destination CRISPRa plasmid.

- Gibson Assembly: Mix ~100 ng of linearized destination vector, a 3-fold molar excess of the PCR insert, 10 µL 2x Gibson Assembly Master Mix. Incubate at 50°C for 1 hour.

- Transform and Screen: Transform into E. coli, screen colonies. The final plasmid will express the dCas9-activator fusion and the target-specific gRNA.

Experimental Workflow: From Design to Validation

Diagram 1: CRISPR Workflow in Streptomycetes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for CRISPR/Cas9 in Streptomycetes

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example (Supplier) |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Toolkits | Pre-assembled E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vectors for knockout or activation. | pCRISPomyces-2 (Addgene #61737); pCRISPRa-Sox2 (constructed in-house). |

| High-GC Polymerase | PCR amplification of genomic DNA and vector fragments from high-GC templates. | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB). |

| Golden Gate Assembly Kit | Modular cloning for multiple gRNAs. | MoClo Toolkit (Addgene) or BsaI-based custom mix. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | Seamless, single-step cloning of gRNA cassettes. | NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (NEB). |

| Methylation-Competent E. coli | Allows replication of Streptomyces plasmids that require methylation. | ET12567/pUZ8002 (Kerry Lab strain). |

| Conjugation Media | Facilitates transfer of plasmid from E. coli to Streptomyces via intergeneric conjugation. | MS agar with 10mM MgCl₂. |

| Selective Antibiotics | Selection for exconjugants. | Apramycin (plasmid), Thiostrepton (inducible promoter), Nalidixic acid (counterselection). |

| Genotyping Primers | Validate gene knockout, integration, or activation. | Designed to flank target site and internal check. |

| HPLC-MS System | Analyze secondary metabolite production from activated or mutated BGCs. | Agilent 1260 Infinity II/6546 LC/Q-TOF. |

Validation and Data Interpretation

- Genotypic Validation: Perform colony PCR using primers flanking the target site. For knockouts, look for a size shift (deletion) or loss of amplification (large deletion). Sequence the amplified product.

- Phenotypic Validation:

- For BGC Activation: Extract metabolites from wild-type and engineered strains. Analyze by HPLC-MS. Look for new or enhanced peaks. Quantify yield.

- For Essential Gene Knockout: Use a conditionally replicating plasmid or a second-site complementation. Validate via essential growth defect under non-permissive conditions and rescue under permissive conditions.

- For BGC Knockout: Confirm loss of metabolite production via HPLC-MS.

Table 3: Example Quantitative Data from a Fictional BGC Activation Study

| Strain | Target (gRNA) | HPLC Peak Area (Target Metabolite) | Relative Yield (%) | Genotyping Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type S. coelicolor | N/A | 15,500 ± 1,200 | 100% | N/A |

| pCRISPRa-empty vector | N/A | 14,800 ± 950 | 95% | 100% (vector control) |

| pCRISPRa-gRNA_1 | actII-ORF4 P1 | 285,000 ± 32,000 | 1839% | 85% (12/14 exconjugants) |

| pCRISPRa-gRNA_2 | actII-ORF4 P2 | 45,000 ± 5,500 | 290% | 80% (8/10 exconjugants) |

| pCRISPRa-gRNA_3 | actVA-ORF1 | 18,200 ± 2,100 | 117% | 90% (9/10 exconjugants) |

1. Introduction

In the context of CRISPR/Cas9 applications for streptomycete genome editing, efficient delivery of editing machinery is paramount. While techniques like protoplast transformation and electroporation exist, intergeneric conjugation from E. coli stands as the gold standard for introducing DNA into Streptomyces species. This method reliably yields high transformation efficiencies, especially for large DNA constructs like BACs or cosmids, and is less dependent on the strain-specific idiosyncrasies that often hinder other methods. This guide details the protocol, rationale, and optimization of this critical technique.

2. Core Protocol: Triparental Conjugal Transfer from E. coli to Streptomyces

2.1. Principle The method utilizes a three-strain mating system. The donor E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002) contains the plasmid with the desired CRISPR/Cas9 construct but is methylation-deficient (Dam-/Dcm-) and carries the conjugal machinery (oriT, tra genes) on a helper plasmid. The presence of a non-methylated plasmid is crucial as Streptomyces possess restriction-modification systems that degrade methylated DNA. A third E. coli strain, often HB101 containing a pRK2013 helper, can be used in biparental matings to mobilize non-mobilizable plasmids.

2.2. Required Reagents & Materials

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Conjugation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002) | Donor strain; dam-/dcm-/hsdM- to produce non-methylated DNA, carries helper plasmid with tra genes. |

| Streptomyces Spores/Mycelium | Recipient strain. Heat-shocked spores are typically used. |

| pKC1139-based or pCRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid | Shuttle vector containing oriT for mobilization, Streptomyces replicon, and CRISPR editing machinery. |

| LB with appropriate antibiotics | For growth of E. coli donor and helper strains. |

| TSBS (Trypticase Soy Broth with Sucrose) | Medium for germination of Streptomyces spores. |

| Mannitol Soya Flour (MS) Agar Plates | Solid medium for conjugal mating and subsequent selection. |

| 10mM MgSO₄ | Used for washing and diluting Streptomyces spores. |

| Nalidixic Acid | Selects against E. coli donor on mating plates. |

| Apramycin/Thiostrepton | Antibiotics for selection of Streptomyces exconjugants containing the delivered plasmid. |

| L-Glutamine (0.5%) | Optional supplement to improve Streptomyces growth on plates post-mating. |

2.3. Detailed Methodology

Day 1: Preparation

- Donor Culture: Inoculate E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002) containing your construct from a single colony into LB with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., kanamycin for pUZ8002, apramycin for CRISPR plasmid). Grow overnight at 37°C with shaking.

- Recipient Preparation: Harvest Streptomyces spores from a fresh plate (7-10 days old) using 10mM MgSO₄ and glass beads. Heat-shock the spore suspension at 50°C for 10 minutes to synchronize germination. Adjust concentration.

Day 2: Mating

- Donor Preparation: Subculture the overnight E. coli donor 1:100 into fresh LB with antibiotics and grow at 37°C to an OD₆₀₀ of ~0.4-0.6. Wash cells 2x with an equal volume of LB to remove antibiotics.

- Mixing: Mix 100 µl of washed donor cells, 100 µl of heat-shocked Streptomyces spores (~10⁸ CFU), and 800 µl of LB in a microfuge tube.

- Pellet and Plate: Pellet the mixture, gently resuspend in 100 µl LB, and spot onto the center of a pre-dried MS agar plate (without antibiotics). Let the spot absorb completely.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate right-side-up at 30°C for 16-20 hours.

Day 3: Selection

- Overlay: After incubation, overlay the conjugation spot with 1 ml of sterile water containing 0.5 mg nalidixic acid (to counter-select E. coli) and the appropriate antibiotic(s) for plasmid selection in Streptomyces (e.g., 50 µg/ml apramycin). Spread gently with a sterile spreader.

- Final Incubation: Allow the plate to dry and incubate at 30°C for 3-7 days until exconjugant colonies appear.

3. Quantitative Data & Optimization

Table 2: Typical Efficiency and Key Variables

| Factor | Typical Range/Optimum | Impact on Conjugation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Strain | ET12567(pUZ8002) | Essential for non-methylated DNA and mobilization. |

| Recipient Form | Heat-shocked spores > Mycelium | Spores are more consistent and resistant to lysis. |

| Donor-to-Recipient Ratio | 1:1 to 10:1 (by volume) | Critical; must be optimized per Streptomyces strain. |

| Mating Medium | MS Agar > SFM Agar > R5 Agar | MS provides high efficiency for many species. |

| Overlay Timing | 16-20 hours post-mating | Allows for initial cell fusion and establishment. |

| Typical Yield | 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁶ exconjugants per recipient spore | Varies significantly with plasmid size and strain. |

4. Integration within a CRISPR/Cas9 Workflow for Streptomyces

The conjugation delivery method is the first critical step in the genome editing pipeline. The delivered plasmid typically contains the Cas9 gene, a guide RNA expression cassette, and a template for homology-directed repair (HDR). After selection of exconjugants, the CRISPR machinery is induced to create a double-strand break, leading to the desired edit.

CRISPR Workflow with Conjugation Delivery

5. Molecular Basis of Conjugal Transfer

The efficiency of conjugation hinges on specific genetic elements. The helper plasmid (pUZ8002) provides the tra genes in trans for pilus formation and mating pair stabilization. The shuttle vector must contain an origin of transfer (oriT), where the relaxosome nicks and initiates transfer. The Streptomyces replicon ensures maintenance in the recipient.

Key Elements in Conjugal DNA Transfer

6. Conclusion

For CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in Streptomyces, reliable DNA introduction is non-negotiable. Conjugation from E. coli provides a robust, high-efficiency delivery platform that overcomes the significant barriers posed by Streptomyces cell walls and restriction systems. Mastery of this protocol, including optimization of donor-recipient ratios and media, is a foundational skill for any researcher aiming to leverage modern genetic tools in these industrially and medically vital bacteria.

The advent of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized genetic manipulation in streptomycetes, the prolific producers of clinically vital antibiotics and other natural products. This whitepaper details three synergistic applications enabled by this precise editing: the activation of cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), the rational redesign (refactoring) of pathways, and the generation of novel chemical entities via combinatorial biosynthesis. These approaches are central to revitalizing natural product discovery and expanding chemical diversity for drug development.

Activating Silent Gene Clusters

Silent or cryptic BGCs represent a vast untapped reservoir of bioactive compounds. CRISPR/Cas9 facilitates their activation through targeted genetic perturbations.

Core Strategies & Quantitative Outcomes:

| Activation Strategy | Target Gene/Element | Example Host | Efficiency (Activation Rate) | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter Replacement | Native promoter of cluster pathway-specific regulator | S. albus J1074 | >90% (via homologous recombination) | Production of novel polyketide |

| Deletion of Repressors | bldA (tRNA for rare leucine codon) or cluster-specific repressors | S. coelicolor | 70-80% repression relief | Enhanced actinorhodin production |

| CRISPRa Interference | dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators (e.g., SoxS) targeting promoter regions | S. venezuelae | 5-50 fold increase in transcription | Triggering of specific cryptic cluster expression |

| Epigenetic Remodeling | Deletion of histone methyltransferase (ΔlmbB2) | S. ambofaciens | Up to 100-fold yield increase | Production of stambomycins |

Detailed Protocol: Promoter Replacement for Cluster Activation

- Design: Identify the putative pathway-specific regulator within the silent BGC. Design a CRISPR/Cas9 sgRNA to introduce a double-strand break (DSB) immediately upstream of its start codon. Synthesize a donor DNA template containing a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., ermEp*) flanked by ~1 kb homology arms.

- Delivery: Transform Streptomyces protoplasts with a plasmid expressing Cas9, the sgRNA, and the donor template, or use a two-plasmid system.

- Selection & Screening: Select for apramycin resistance (or other markers). Screen colonies by PCR for correct promoter integration.

- Fermentation & Analysis: Cultivate positive clones in suitable media. Analyze metabolite profiles via LC-MS and compare to parental strain.

Pathway Refactoring

Refactoring involves the systematic redesign of a BGC into a modular, host-agnostic format for predictable expression and optimization.

Key Refactoring Metrics:

| Refactored Pathway | Original Cluster Size (kb) | Refactored Elements | Titer Improvement | Host Strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redeomycin BGC | 45 kb | Native promoters replaced with synthetic counterparts; codon optimization | 12-fold | S. albus |

| Spectinomycin | 35 kb | Regulatory genes removed; ribosomal binding sites standardized | 8-fold | S. lividans |

| Violacein (heterologous) | 7.5 kb | Divided into 3 transcriptional units under T7 promoters | 20 mg/L in S. coelicolor | S. coelicolor |

Detailed Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Multi-Gene Refactoring

- Deconstruction: Design sgRNAs to delete native promoters and intervening sequences between core biosynthetic genes. Provide a donor template containing a series of synthetic, orthogonal promoters (e.g., SF14p, gapdhp) and strong RBSs, assembled in the desired order with homology arms.

- Iterative Editing: Employ successive rounds of CRISPR/Cas9 editing, or use a multi-sgRNA plasmid for simultaneous cuts.

- Validation: Verify the final refactored locus by long-range PCR and sequencing. Transcriptional analysis via RT-qPCR confirms expected expression patterns.

- Titer Optimization: Ferment refactored strain while modulating key parameters (precursor feeding, media composition).

Combinatorial Biosynthesis

CRISPR/Cas9 enables precise swapping, deletion, or insertion of domains, modules, or entire genes from different BGCs to create hybrid pathways.

Combinatorial Biosynthesis Examples:

| Combinatorial Approach | Enzyme Domains/Genes Swapped | Parent Compounds | Number of Novel Analogs Generated | Bioactivity Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PKS Module Swapping | AT (Acyltransferase) domains from different polyketide synthases | Doxycycline / Tetracenomycin | 5 | Altered antibacterial spectrum |

| NRPS Adenylation Domain Engineering | A domains with different substrate specificities | Daptomycin / CDA | 8 | Improved anti-MRSA activity |

| Glycosyltransferase Swapping | Sugar-biosynthesis genes and glycosyltransferases | Erythromycin / Oleandomycin | >10 | Modified pharmacokinetic properties |

Detailed Protocol: Domain Swapping in a Type I PKS using CRISPR/Cas9

- Targeting: Design two sgRNAs to create DSBs precisely at the boundaries of the target AT domain within the PKS gene. The donor template should contain the heterologous AT domain, flanked by ~1.5 kb homology arms corresponding to the upstream and downstream sequences of the native domain.

- Cloning & Transformation: Clone sgRNAs and donor into a Streptomyces CRISPR/Cas9 vector. Introduce into the producer strain via conjugation from E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002.

- Screening: Screen exconjugants by PCR and sequence the modified PKS locus to confirm precise domain exchange.

- Metabolite Characterization: Iscale fermentation, extract metabolites, and purify novel polyketides using HPLC. Elucidate structures using NMR and HR-MS.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in CRISPR/Streptomyces Experiments |

|---|---|

| pCRISPomyces-2 Plasmid | Integrative Streptomyces vector expressing Cas9 and sgRNA, with temperature-sensitive origin for curing. |

| ET12567/pUZ8002 E. coli Strain | Non-methylating E. coli donor strain for intergeneric conjugation with Streptomyces. |

| Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) with Sucrose | Osmotic stabilizer for preparation and regeneration of Streptomyces protoplasts. |

| Apramycin (AprR) & Thiostrepton (TsrR) | Common selection antibiotics for Streptomyces genetic markers. |

| HR-Donor DNA Fragments | Linear dsDNA with 1-1.5 kb homology arms for high-efficiency homology-directed repair (HDR). |

| dCas9-SoxS Fusion Protein | CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) tool for targeted transcriptional upregulation of silent genes. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | For rapid, seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments (e.g., refactored operons) for donor constructs. |

| MS agar with Mannitol | Solid medium for efficient sporulation and conjugation of most Streptomyces species. |

Visualizations

Title: CRISPR/Cas9 Strategies for Activating Silent Gene Clusters

Title: Pathway Refactoring from Native to Modular Design

Title: Workflow for Combinatorial Biosynthesis via CRISPR/Cas9

Solving the Puzzle: Troubleshooting Low Efficiency and Optimizing CRISPR Editing in Streptomyces

Within the expanding thesis of CRISPR/Cas9 applications in streptomycete genome editing, the confirmation of intended genetic modifications remains a critical bottleneck. Streptomyces species, renowned for their complex life cycles and prolific secondary metabolite production, present unique challenges including high GC-content genomes, intricate DNA repair pathways, and frequent genomic rearrangements. Successful genome engineering in these industrially vital actinomycetes hinges on robust, multi-tiered diagnostic workflows to differentiate between editing success, partial outcomes, and failure. This guide details the core post-editing analytical pipeline centered on PCR screening and sequencing, providing a systematic approach to validate edits and troubleshoot common issues.

Core Diagnostic Workflow: From Colony to Sequence

The standard workflow for verifying CRISPR/Cas9 edits in streptomycetes involves sequential steps of increasing resolution, designed to efficiently triage numerous candidates before committing resources to definitive sequencing.

Primary Colony PCR Screening

The first line of analysis is a colony PCR designed to rapidly screen for the presence or absence of the edit.

Protocol: Colony PCR for Deletion/Insertion Screening

- Template Preparation: Using a sterile pipette tip, pick a portion of a candidate colony and resuspend in 20 µL of lysis buffer (e.g., 20 mM NaOH, 0.1% Tween 20). Heat at 95°C for 10 minutes, then centrifuge briefly. Use 1 µL of supernatant as PCR template.

- PCR Reaction Mix:

- 10 µL 2x High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix

- 1 µL Forward Primer (10 µM), designed ~200-300 bp upstream of the 5' edit junction

- 1 µL Reverse Primer (10 µM), designed ~200-300 bp downstream of the 3' edit junction

- 7 µL Nuclease-free water

- 1 µL Colony lysate

- Thermocycling Conditions (for a 1-2 kb amplicon):

- 98°C for 2 min (initial denaturation)

- 35 cycles of: 98°C for 10 s, 68°C for 20 s, 72°C for 60 s/kb

- 72°C for 5 min (final extension)

- Analysis: Run products on a 0.8-1.2% agarose gel. Compare amplicon size to wild-type control.

- Deletion: A smaller product indicates successful deletion.

- Insertion: A larger product indicates successful insertion.

- Wild-type size: Suggests editing failure or heterogenous culture.

- Multiple bands: Suggests mixed population or incomplete editing.

Primary Diagnostic PCR Workflow

Diagnostic PCR Strategies for Different Edit Types

Different edits require tailored primer design and interpretation.

Table 1: PCR Strategy for Common Edit Types in Streptomycetes

| Edit Type | Primer Design Strategy | Expected Outcome (vs. WT) | Common Pitfall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Knockout | One primer pair flanking the entire target deletion. | Single, smaller band. | PCR across large deletions may be inefficient. |

| Gene Insertion | One primer pair flanking the insertion site. | Single, larger band. | Mis-priming within repetitive insertion sequences. |

| Point Mutation | Primer pairs creating/removing a restriction site (RFLP-Check) or using mismatch primers for ARMS-PCR. | Altered restriction pattern or selective amplification. | Incomplete digestion; false positives in ARMS-PCR. |

| Promoter Swap | Junction-specific primers: Fwd in new promoter, Rev in downstream gene. | Band only in successful edit. | Non-specific amplification from homologous promoters. |

Sequencing-Based Confirmation

Positive candidates from primary screening must be validated by Sanger sequencing to confirm the precise genomic alteration and rule out unintended mutations.

Protocol: Amplicon Purification and Sequencing

- PCR Clean-up: Purify the diagnostic PCR product using a spin-column based PCR purification kit. Elute in 30 µL nuclease-free water.

- Quantification: Measure DNA concentration using a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop). Aim for >20 ng/µL.

- Sequencing Reaction: Prepare reaction using 5-10 ng of purified PCR product per 100 bp of amplicon length, 1 µM of either forward or reverse primer, and sequencing mix. Cycle sequencing conditions: 96°C for 1 min, followed by 25 cycles of 96°C for 10 s, 50°C for 5 s, 60°C for 4 min.

- Purification & Capillary Electrophoresis: Clean up sequencing reactions and run on a capillary sequencer.

Analysis: Align sequencing chromatograms to the reference sequence using software (e.g., SnapGene, Geneious, Benchling). Scrutinize the edit junction and the entire amplicon for:

- Precise intended edit.

- Unintended single-nucleotide variants (SNVs).

- Small insertions/deletions (indels) at the cut site, indicative of error-prone NHEJ repair.

- Multi-peak chromatograms after the edit site, suggesting a mixed clone population.

Troubleshooting Common Failure Modes

A systematic diagnostic approach identifies the root cause of editing failures.

Table 2: Common Issues and Diagnostic Pathways in Streptomycete Editing

| Observed Result | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Action | Interpretation & Next Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| No colonies after editing | Cas9 toxicity, inefficient DSB repair, lethal edit. | Check transformation efficiency with control plasmid. Perform TUNEL assay or qPCR for apoptosis markers. | Optimize Cas9 expression (inducible promoter). Use NHEJ-deficient (ΔligD) host for HDR. |

| Colonies, but all are WT by PCR | Inefficient gRNA, poor HDR template delivery, plasmid loss. | Sequence the gRNA expression cassette. PCR for editing plasmid backbone in candidates. | Re-design gRNA with improved efficiency. Use replicating or integrative templates with longer homology arms. |

| Mixed PCR results (multiple bands) | Heterogeneous population, merodiploid intermediate state. | Re-streak colony for isolation. Perform Southern blot for copy number. | Execute 2-3 rounds of single-colony isolation. Screen more colonies from initial transformation. |

| Correct size amplicon but failed Sanger | Large, complex rearrangement at target site. | Use long-range PCR across extended region. Perform whole-genome sequencing (WGS) on candidate. | Streptomyces prone to large deletions/amplifications. Design gRNAs avoiding repetitive regions. |

| Unexpected mutations elsewhere | Off-target effects, stress-induced mutagenesis. | Perform WGS or target potential off-target sites predicted in silico. | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants. Express Cas9 transiently. Validate phenotype with complemented strain. |

Decision Tree for Diagnosing Editing Failures

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Diagnostic PCR and Sequencing in Streptomyces

| Reagent / Kit | Function & Rationale | Key Consideration for Streptomycetes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) | Amplifies GC-rich templates with low error rate for sequencing. | Essential for high-GC (>70%) Streptomyces genomic DNA. Use with GC enhancer. |

| Colony Lysis Buffer (NaOH/Tween) | Rapid, PCR-compatible DNA release from tough mycelial/clonal mats. | More reliable than direct colony PCR for sporulating and mycelial samples. |

| PCR Purification Kit | Removes primers, enzymes, and dNTPs post-amplification for clean sequencing. | Mandatory step before Sanger sequencing to obtain high-quality chromatograms. |

| Cycle Sequencing Kit (BigDye etc.) | Incorporates fluorescent chain-terminators for capillary electrophoresis. | Optimize template:primer ratio due to high GC content. |

| Agarose Gel DNA Recovery Kit | Isolates specific amplicon from gel if multiple bands are present. | Necessary for resolving mixed populations or non-specific amplification. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Service/Library Kit | For whole-genome validation of edits and off-target analysis. | Crucial for final publication-quality validation in a new host strain. |

| Southern Blotting Components | Historical gold standard for detecting large deletions/insertions/rearrangements. | Useful when PCR-based methods are inconclusive due to complex edits. |

Within the broader context of CRISPR/Cas9 applications in Streptomyces genome editing, achieving high-efficiency homologous recombination (HR) is paramount. These industrially vital, GC-rich bacteria are prolific producers of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites. CRISPR-mediated double-strand breaks (DSBs) must be repaired via homology-directed repair (HDR) for precise genome engineering. This guide details two synergistic strategies to enhance HDR rates: the empirical optimization of donor DNA length and the deployment of recombineering proteins (e.g., RecET, λ-Red) to catalyze the recombination process, overcoming the inherent limitations of native streptomycete recombination machinery.

Quantitative Data on Donor DNA Homology Arm Length

The efficiency of HR in Streptomyces is directly correlated with the length of homologous sequences (homology arms) in the donor DNA. Recent studies in model species like S. coelicolor provide critical benchmarks.

Table 1: Impact of Donor DNA Homology Arm Length on Editing Efficiency in Streptomyces

| Homology Arm Length (bp) | Relative Editing Efficiency (%) | Primary Outcome & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| < 500 bp | 0 - 10% | Very low efficiency; high rate of non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or failure. |

| 500 - 800 bp | 10 - 40% | Moderate efficiency; sufficient for simple deletions/insertions with strong selection. |

| 800 - 1200 bp | 40 - 70% | High efficiency; recommended for most routine gene knock-outs and point mutations. |

| > 1200 bp | 70 - >95% | Very high efficiency; optimal for large insertions (>5 kb) or complex edits without selection. |

| Asymmetric Arms (e.g., 500 bp / 1200 bp) | 30 - 60% | Useful when upstream/downstream sequence constraints differ; longer arm dictates efficiency. |

Data synthesized from recent studies utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 systems in S. coelicolor and S. albus (2022-2024).

Protocol: Optimizing and Assembling Donor DNA

Objective: To construct a donor DNA template with optimized homology arms for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HDR in Streptomyces.

Materials:

- Genomic DNA from the target Streptomyces strain.

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Q5).

- Gibson Assembly or Golden Gate Assembly reagents.

- Desired editing cassette (e.g., antibiotic marker, promoter).

- Plasmid backbone for E. coli propagation.

Method:

- Design: Using the genomic sequence flanking the Cas9 cut site (typically within 10 bp of the PAM), design two homology arms. For a standard knock-in, aim for 1000 bp each.

- Amplification: PCR-amplify the left homology arm (LHA) and right homology arm (RHA) from wild-type genomic DNA. Include 20-30 bp overhangs complementary to your editing cassette and cloning vector.

- Assembly: Use a seamless assembly method (e.g., Gibson Assembly) to clone the LHA, editing cassette, and RHA into an appropriate E. coli vector. This plasmid serves as the donor template.

- Validation: Sequence the entire assembled donor construct to ensure perfect homology and the absence of mutations.

- Delivery: For Streptomyces, the donor DNA can be delivered as a linear PCR product (amplified from the plasmid) or as a non-replicating plasmid. Linear dsDNA with long homology arms is often most effective when combined with recombineering.

Recombineering Proteins: Mechanisms and Applications

Native HR in Streptomyces can be inefficient. Heterologous recombineering systems introduce bacterial phage-derived proteins that bind to linear dsDNA ends and promote strand annealing/invasion.

Key Systems:

- λ-Red (from phage λ): Requires three proteins: Gam (inhibits host RecBCD nuclease), Exo (a 5'→3' exonuclease that generates 3' ssDNA overhangs), and Beta (a single-stranded DNA-binding protein that promotes annealing).

- RecET (from Rac prophage): Simpler two-component system: RecE (a 5'→3' exonuclease similar to λ-Exo) and RecT (a ssDNA annealing protein similar to λ-Beta).

These systems are typically introduced into Streptomyces on a temperature-sensitive plasmid or integrated into the genome under an inducible promoter.

Protocol: Implementing λ-Red/RecET Recombineering inStreptomyces

Objective: To transiently express recombineering proteins to enhance the integration of a donor DNA template.

Materials:

- Streptomyces strain harboring a CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid targeting the locus of interest.

- Donor DNA template (linear dsDNA with ~1000 bp homology arms).

- Expression plasmid carrying λ-Red (gam, exo, bet) or RecET (recE, recT) under a constitutive or inducible promoter (e.g., tipA or ermE).

- Culture media appropriate for the strain and plasmid maintenance.

Method:

- Strain Preparation: Transform the target Streptomyces strain with the recombineering protein expression plasmid. Grow at permissive conditions.

- Induction: Inoculate the strain into fresh medium and induce expression of the recombineering proteins (e.g., by temperature shift for a heat-sensitive promoter or addition of an inducer like thiostrepton for tipA).

- Electrocompetent Cell Preparation: Harvest mycelia during late exponential growth. Wash extensively with cold 10% glycerol to create electrocompetent protoplasts or mycelial fragments.

- Co-transformation: Electroporate a mixture of the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid (or a plasmid expressing Cas9 and sgRNA) and the linear donor DNA (100-500 ng) into the induced, competent cells.

- Recovery and Selection: Allow cells to recover in non-selective liquid medium for 12-24 hours to permit recombination and repair. Plate onto selective media containing antibiotics for both the CRISPR plasmid (to maintain selection pressure for DSB repair) and the donor DNA marker.

- Screening: Isolate colonies and screen via colony PCR and sequencing to identify precise edits.

Visualization of the Enhanced HR Workflow

Diagram 1: Workflow for Enhanced HR in Streptomyces.

Diagram 2: Molecular Mechanism of RecET Recombineering.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Enhanced HR inStreptomyces

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Enhanced HR | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Homology Arm Donor DNA | Template for HDR; longer arms (>800 bp) increase recombination frequency. | Can be generated as linear PCR fragment or cloned in a vector. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmid for Streptomyces | Provides sequence-specific DSB at the target locus to stimulate repair. | Use a plasmid with a Streptomyces replicon (e.g., pKC1139 derivative) and appropriate promoter (ermE*). |

| Recombineering Protein Expression Plasmid | Expresses phage-derived proteins (RecET or λ-Red) to catalyze recombination of linear DNA. | Often temperature-sensitive (e.g., pIJ790 derivative) or inducible. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Error-free amplification of long homology arms for donor construction. | Q5, Phusion. |

| Seamless DNA Assembly Kit | For cloning long homology arms and edit cassettes without introducing scars. | Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate Assembly. |

| Electrocompetent Streptomyces Cells | Essential for high-efficiency transformation of DNA (CRISPR plasmid + linear donor). | Prepared from germinated spores or young mycelia in 10% glycerol. |

| Inducer (e.g., Thiostrepton) | To control expression of recombineering proteins or Cas9/sgRNA from inducible promoters. | Used with tipA or other inducible systems. |

| HR-Specific Selection Antibiotics | Selects for cells that have integrated the donor DNA cassette. | Choice depends on donor's resistance marker (apramycin, hygromycin, etc.). |

The synergy between optimized donor DNA design and phage-derived recombineering systems represents a powerful methodological advance for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in Streptomyces. By systematically applying the principles and protocols outlined here—employing donors with homology arms extending beyond 800 bp and transiently expressing proteins like RecET—researchers can achieve high-efficiency, precise genetic modifications. This capability is foundational for advanced metabolic engineering, silent gene cluster activation, and functional genomics in these biotechnologically critical bacteria, accelerating drug discovery and development pipelines.