CRISPRa vs CRISPRi: Mechanisms, Applications, and Optimization for Precision Genetic Control

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) technologies for researchers and drug development professionals.

CRISPRa vs CRISPRi: Mechanisms, Applications, and Optimization for Precision Genetic Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) technologies for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational mechanisms of these programmable transcriptional tools, detailing how catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) is fused to effector domains like VP64 or KRAB to upregulate or repress gene expression. The scope extends to methodological considerations for experimental design, troubleshooting common challenges, and a comparative analysis of their performance against alternative technologies like RNAi and ORF overexpression. By synthesizing recent advances, including novel drug-inducible and dual-mode systems, this review serves as a practical guide for leveraging CRISPRa/i in functional genomics screens and therapeutic development.

The Core Machinery: Deconstructing CRISPRa and CRISPRi Mechanisms

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) system, derived from a bacterial adaptive immune system, has revolutionized genetic engineering. While the native system functions as programmable "DNA scissors" capable of cutting DNA, a transformative advancement emerged with the creation of catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9). This engineered variant contains point mutations (D10A and H840A in Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) that abolish its nuclease activity while preserving its programmable DNA-binding capability [1] [2]. This fundamental shift converted CRISPR from a destructive tool into a precise targeting system, enabling transcriptional modulation without altering the underlying DNA sequence [3].

This technical guide explores the core mechanisms and applications of dCas9-based systems, specifically CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for gene repression and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) for gene upregulation. Framed within a broader thesis on CRISPRi versus CRISPRa mechanisms, this review provides an in-depth analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the experimental paradigms, key reagent solutions, and therapeutic potential of these powerful technologies.

Core dCas9 Mechanisms: CRISPRi vs. CRISPRa

The dCas9 protein serves as a programmable DNA-binding scaffold. When guided by a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to a specific genomic locus, it can sterically hinder transcription or recruit effector domains to repress or activate gene expression [3] [4]. The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of these two systems.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of CRISPRi and CRISPRa Systems

| Feature | CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) | CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Gene knockdown/silencing | Gene overexpression/activation |

| dCas9 Fusion | Transcriptional repressors (e.g., KRAB domain) | Transcriptional activators (e.g., VP64, VPR, SunTag, SAM) |

| Mechanism of Action | Blocks RNA polymerase binding or elongation; induces heterochromatin formation [4] [5] | Recruits transcriptional machinery to promoter/enhancer regions [4] [5] |

| Level of Regulation | Transcriptional (DNA level) | Transcriptional (DNA level) |

| Typical Repression/Activation | Up to 60-80% with dCas9 alone; >90% with dCas9-KRAB [4] | Varies by system; advanced systems (SAM, VPR) enable robust, synergistic activation [5] |

| Analogous Technology | RNA interference (RNAi) | ORF (Open Reading Frame) overexpression [5] |

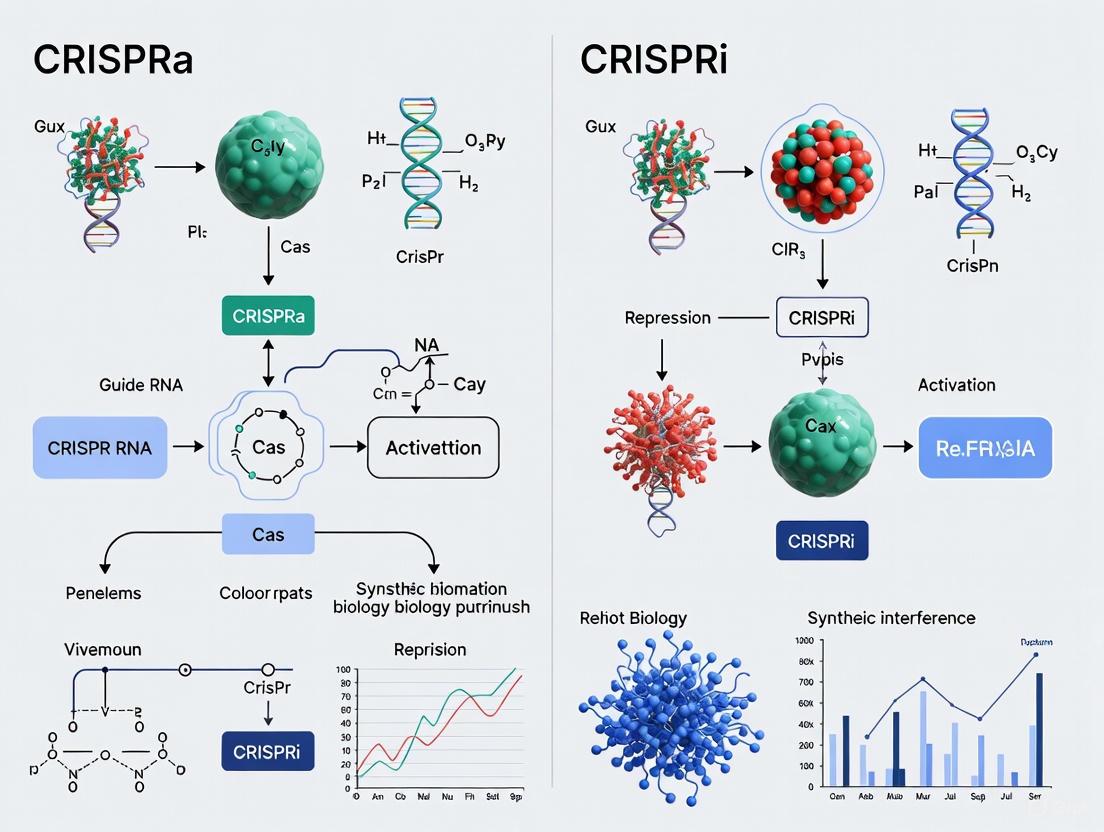

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic differences and key components of the CRISPRi and CRISPRa systems.

Advanced Architectures & Experimental Workflows

Enhanced System Architectures

While a simple dCas9-effector fusion can modulate transcription, more sophisticated architectures have been developed for enhanced efficacy, particularly for CRISPRa.

- Direct Fusion Systems: The simplest format, where the effector domain (e.g., KRAB for repression, VP64 for activation) is directly fused to dCas9. The VPR system is a potent direct fusion activator, combining VP64, p65, and Rta domains [5].

- Protein Scaffold Systems: These systems separate the dCas9 binder from the effector proteins. The SunTag system uses dCas9 fused to a repeating peptide array (GCN4), which is then recognized by single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) fused to effector domains like VP64. This allows for the recruitment of multiple activator molecules per dCas9, significantly amplifying the transcriptional signal [4] [5].

- RNA Scaffold Systems: This approach leverages modifications to the sgRNA itself. The Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) system uses an sgRNA engineered with RNA aptamers (e.g., MS2). These aptamers recruit fusion proteins (e.g., MCP-p65-HSF1), which work synergistically with a dCas9-VP64 fusion to drive strong gene activation [5].

A Standard Workflow for Pooled CRISPRi/a Screens

Pooled genetic screens are a primary application for CRISPRi/a, enabling the systematic identification of genes involved in biological processes or drug mechanisms. The general workflow is summarized below.

Table 2: Key Stages of a Pooled CRISPRi/a Screen

| Stage | Key Actions | Output/Quality Control |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Library Design & Cloning | Select genome-wide or sub-library of sgRNAs; clone into lentiviral vector [5]. | A plasmid library representing the entire sgRNA pool. |

| 2. Viral Production & Cell Transduction | Produce lentivirus from plasmid library; transduce target cells at low MOI. | A population of cells where each cell receives, in theory, a single sgRNA. |

| 3. Phenotypic Selection | Apply selective pressure (e.g., drug treatment, FACS sorting based on reporter, or long-term growth) [5]. | Enrichment or depletion of specific sgRNA-containing cells based on phenotype. |

| 4. Sequencing & Hit Identification | Extract genomic DNA from pre- and post-selection cells; PCR-amplify sgRNA sequences; NGS to quantify abundance [5]. | List of sgRNAs significantly enriched/depleted, revealing candidate hit genes. |

The corresponding experimental workflow is visualized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of CRISPRi/a experiments requires a suite of well-characterized reagents. The table below details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for dCas9 Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples / Systems | Function & Utility |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Effector Plasmids | dCas9-KRAB (for CRISPRi), dCas9-VP64, dCas9-VPR, SunTag, SAM [4] [5] [6] | Constitutive or inducible expression of the dCas9-effector fusion protein. The core of the system. |

| sgRNA Cloning Vectors | Lentiviral sgRNA vectors (single or multiplex), with Pol III promoters (e.g., U6) [1] [6] | For expression of one or more sgRNAs. Multiplex vectors enable targeting several genomic sites simultaneously. |

| sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide human/mouse knockout (GeCKO) libraries, focused sub-libraries (e.g., kinase-family) [4] [5] | Pre-designed pools of sgRNAs for large-scale genetic screens. Available from multiple non-profit and commercial sources. |

| Delivery Tools | Lentiviral, adenoviral (AVV) vectors; lipid nanoparticles (LNPs); synthetic sgRNA [4] [7] [1] | Enable efficient introduction of CRISPR components into target cells, both in vitro and in vivo. |

| Validation Assays | RT-qPCR, RNA-seq; Western blot; flow cytometry; targeted bisulfite sequencing (for epigenome editing) [6] | Essential for confirming changes in gene expression, protein levels, and epigenetic state at on-target and potential off-target sites. |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T (for virus production), K562, HeLa, iPSCs, and other disease-relevant models [5] [6] | Well-characterized models used for tool development and functional screens. |

Quantitative Data & Applications in Functional Genomics

Performance in Genetic Screens

CRISPRi and CRISPRa screens have become indispensable for functional genomics. The table below summarizes quantitative findings and applications from key studies, demonstrating their power and versatility.

Table 4: Applications and Findings from CRISPRi/a Screens

| Application Area | System Used | Key Finding / Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identifying Essential Genes | Genome-wide CRISPRi in K562 cells | Successfully identified "gold-standard" essential genes (e.g., ribosomal subunits) and cell-type specific essential genes. | [5] |

| Drug Target & Mechanism | CRISPRa screen in A375 melanoma cells | Identified genes whose overexpression conferred resistance to a BRAF inhibitor, revealing drug resistance mechanisms. | [5] |

| Non-Coding RNA Functional Screening | CRISPRi screen targeting lncRNAs in multiple cell lines | Discovered cell-type specific essential long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), a class difficult to study with other methods. | [5] |

| Epigenetic Therapy Exploration | dCas9-TET1 targeting miR-200c promoter | Targeted demethylation reactivated the tumor-suppressor miR-200c, reducing cell viability and increasing apoptosis in breast cancer cells. | [6] |

| Neuroscience & Disease Modeling | CRISPRi in iPSC-derived neurons | Uncovered genes essential for neuronal growth and survival that were not essential in pluripotent stem cells or cancer cells. | [4] |

Advantages Over Alternative Technologies

Compared to previous technologies for gene modulation, CRISPRi/a offers distinct advantages:

- vs. RNA Interference (RNAi): CRISPRi suppresses gene expression at the transcriptional level, leading to more complete and specific knockdown with fewer off-target effects than RNAi, which operates at the post-transcriptional level [3] [5].

- vs. CRISPR Nuclease (CRISPRn): Unlike CRISPRn, which causes permanent DNA double-strand breaks and gene knockouts, CRISPRi/a is reversible and does not damage the DNA. This is crucial for studying essential genes, as CRISPRn knockout can be lethal, while CRISPRi knockdown allows for viable phenotypic analysis [4].

- vs. cDNA Overexpression: CRISPRa drives expression from the native endogenous gene locus, preserving natural splice variants, regulatory feedback, and gene dosage, which is often not the case with cDNA ORF overexpression from viral vectors [4].

Clinical & Commercial Translation

The dCas9 platform is paving the way for next-generation therapeutics. The global gene editing market is projected to surpass $13 billion USD by 2025, with a significant portion driven by CRISPR technologies [8]. As of Q2 2025, the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy (ASGCT) reported 4,469 advanced therapies in development, with 49% being gene therapies [7].

A compelling clinical example is the development of a bespoke CRISPR treatment for a child with a rare defect in protein metabolism; the therapy was developed in under six months through rapid collaboration across academia, industry, and regulators [7]. This highlights the potential for patient-specific gene editing in clinical care.

In drug discovery, CRISPRi/a screens are used to identify novel drug targets and biomarkers. For instance, screens have successfully identified 19S proteasomal subunit levels as a biomarker predictive of patient response to the proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib [5]. Furthermore, the adaptability of CRISPRi has been demonstrated in challenging organisms like the malaria parasite Plasmodium yoelii, opening new avenues for combating infectious diseases [4].

The creation of catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) has fundamentally expanded the CRISPR toolkit beyond simple genome editing. By serving as a programmable DNA-binding scaffold, dCas9 powers both CRISPRi and CRISPRa technologies, allowing for precise, reversible, and efficient modulation of gene expression. As detailed in this guide, the mechanistic understanding, experimental protocols, and reagent toolkits for these systems are now mature, enabling their widespread application in functional genomics, drug discovery, and therapeutic development.

The distinct yet complementary nature of CRISPRi and CRISPRa mechanisms provides researchers with an unparalleled ability to probe gene function, model disease, and identify novel therapeutic targets. While challenges remain—particularly in optimizing delivery and minimizing off-target effects—the continued refinement of dCas9-based systems solidifies their role as indispensable "gene dimmers" in the modern molecular biology arsenal, poised to drive significant innovation in both basic research and clinical medicine.

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) represents a powerful gain-of-function technology within the broader landscape of CRISPR-based transcriptional regulation. This approach utilizes a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) that binds to DNA without introducing double-strand breaks, serving as a programmable platform for recruiting transcriptional activators to specific genomic loci [9] [10]. When contrasted with CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), which employs dCas9 fused to repressors like KRAB to silence gene expression, CRISPRa enables precise upregulation of endogenous genes [11] [12]. This capability is particularly valuable for investigating gene function, modeling genetic diseases, and developing therapeutic strategies aimed at compensating for deficient gene expression.

The evolution of CRISPRa systems has progressed significantly from first-generation constructs to sophisticated multi-component architectures. While the initial dCas9-VP64 fusion demonstrated proof-of-concept, its modest activation levels prompted the development of enhanced systems including VPR, SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator), and SunTag, which employ distinct strategies to amplify transcriptional output [9] [13]. This technical guide examines the core mechanistic principles, comparative performance, and experimental implementation of three principal CRISPRa effector systems—VP64, VPR, and SAM—providing researchers with a framework for selecting and applying these tools in diverse biological contexts.

Molecular Architecture and Mechanism

Core Components and Activation Strategies

CRISPRa systems share fundamental components but diverge in their strategies for recruiting transcriptional machinery. Each system utilizes dCas9 for programmable DNA binding and VP64 domains as foundational activation units, but differs in how these units are organized and amplified.

dCas9-VP64: As the first-generation CRISPR activator, this system employs a direct fusion of dCas9 to a single VP64 activation domain (a tetramer of the Herpes Simplex Viral Protein 16) [9]. The simplicity of this architecture is both its strength and limitation: while facilitating easy delivery, the solitary VP64 domain provides limited recruitment capacity, resulting in modest transcriptional activation typically around 2-fold for many target genes [9].

VPR (VP64-p65-Rta): This system enhances activation potency through a tripartite activator fusion, combining VP64 with two additional strong activation domains: p65 (a subunit of NF-κB) and Rta (a transcriptional activator from Epstein-Barr virus) [9] [13]. Unlike multi-component systems, VPR functions as a single fusion protein with dCas9, streamlining delivery while significantly increasing activation levels—generally exceeding dCas9-VP64 though typically lower than SAM for single-gene targeting [9].

SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator): SAM employs a cooperative, multi-component approach that leverages both protein and RNA engineering. The system consists of: (1) dCas9-VP64; (2) specially engineered sgRNAs containing two MS2 RNA aptamers; and (3) MS2 coat proteins fused to the heterologous activation domains p65 and HSF1 (Heat Shock Factor 1) [9] [13]. This design enables the recruitment of multiple activator complexes per dCas9 molecule, creating a highly potent transcriptional activation platform that consistently demonstrates the highest activation levels for single-gene targeting [9] [13].

Table 1: Core Components of Major CRISPRa Systems

| System | dCas9 Fusion | RNA Components | Additional Protein Components | Recruitment Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-VP64 | dCas9-VP64 | Standard sgRNA | None | Direct fusion |

| VPR | dCas9-VP64-p65-Rta | Standard sgRNA | None | Tripartite direct fusion |

| SAM | dCas9-VP64 | sgRNA with MS2 aptamers | MS2-p65-HSF1 fusion | Aptamer-mediated recruitment |

Mechanism Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the structural organization and transcriptional activation mechanisms of the three CRISPRa systems:

Comparative Performance Analysis

Activation Efficiency Across Systems

The quantitative performance of CRISPRa systems varies significantly depending on target genes, cell types, and experimental conditions. Direct comparisons reveal distinct activation profiles and efficiency patterns across platforms.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of CRISPRa Systems

| System | Activation Level | Multiplexing Efficiency | Specificity | Delivery Complexity | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-VP64 | ~2-10 fold (modest) [9] | Moderate reduction [13] | High [13] | Low (single component) [9] | Modest activation requirements, minimal delivery constraints |

| VPR | Significantly higher than VP64, lower than SAM for single genes [9] | Comparable to SAM and SunTag [9] [13] | High [13] | Medium (single fusion protein) [9] | Balanced applications requiring good activation with simplified delivery |

| SAM | Highest for single-gene activation [9] [13] | Comparable to VPR and SunTag [9] | High [13] | High (three components) [9] | Maximal single-gene activation, when delivery complexity is manageable |

Performance characteristics exhibit notable context-dependence. In HEK293T cells, SAM consistently delivers the highest activation levels, though typically within five-fold of VPR or SunTag systems [13]. However, in other cell lines including U-2 OS and MCF7, VPR and SunTag can outperform SAM, indicating that cell-type-specific factors influence optimal system selection [13]. This pattern extends across species, with VPR, SAM, and SunTag showing similar activation levels (within five-fold) in mouse and Drosophila cells [13].

All three systems maintain high specificity according to RNA-seq analyses, with global gene expression correlations between activator-targeted samples and controls nearly identical to biological replicate correlations (R ≈ 0.98) [13]. This suggests that CRISPRa-mediated effects are highly specific to intended targets without widespread transcriptional disruption.

Advanced System Characterization

Recent single-cell analyses provide deeper insights into how these systems modulate transcriptional dynamics. The SunTag3xVPR system—a hybrid approach combining SunTag scaffolding with VPR activators—demonstrates exceptional potency by prolonging transcriptional burst duration (approximately 95 minutes) and increasing burst amplitude [14]. This system achieved a 48.6% activation ratio in single-cell analyses, surpassing SAM (35.8%), VPR (18.8%), and dCas9-VP64 (13.2%) [14].

Unexpectedly, increasing activator recruitment beyond optimal points can diminish effectiveness. Systems with 10 or more SunTag scaffolds can form solid-like condensates that sequester co-activators like p300 and MED1, reducing dynamicity and impairing activation [14]. This demonstrates that maximal activator multimerization does not necessarily correlate with optimal transcriptional output.

Experimental Implementation

Protocol for CRISPRa System Evaluation

Implementing CRISPRa experiments requires careful planning and optimization. The following protocol outlines key steps for evaluating and comparing CRISPRa systems:

1. System Selection and Vector Assembly:

- Select appropriate CRISPRa plasmids (available from Addgene and other repositories) [9]

- For SAM: Obtain dCas9-VP64, MS2-p65-HSF1, and modified sgRNA with MS2 aptamers [9] [13]

- For VPR: Utilize single vector encoding dCas9-VP64-p65-Rta fusion [9]

- For VP64: Use dCas9-VP64 construct [9]

- Clone sgRNAs targeting promoters of interest into appropriate expression vectors

2. Cell Line Development and Transfection:

- Culture relevant cell lines (HEK293T, HeLa, U-2 OS, or specialized models) [13]

- For stable expression: Use lentiviral transduction with puromycin selection to generate dCas9-expressing cells [12]

- Transfect CRISPRa components using appropriate methods (lipofection, electroporation)

- Include controls: non-targeting sgRNA, transfection controls, and uninduced controls for inducible systems

3. Induction and Timing:

- For inducible systems (e.g., Tet-On), administer doxycycline (1 μg/mL) to initiate dCas9 expression [12]

- Allow 48-72 hours for robust activation before analysis [14]

- For time-course studies, collect samples at 24, 48, and 72 hours post-induction

4. Activation Assessment:

- Quantify mRNA expression using RT-qPCR for target genes

- Normalize to housekeeping genes and calculate fold-change versus controls

- For single-cell resolution: Use flow cytometry with reporter systems (e.g., BFP, GFP) [14]

- Assess protein expression by Western blot or immunofluorescence when antibodies available

- For genome-wide specificity: Perform RNA-seq on activated samples versus controls [13]

5. Data Analysis and Validation:

- Calculate fold-activation for each system across multiple target genes

- Determine statistical significance using appropriate tests (t-tests, ANOVA)

- Confirm specificity by examining off-target gene expression

- Validate phenotypes through functional assays relevant to target genes

Specialized Applications and Model Systems

Inducible CRISPRa Systems: Recent advances enable precise temporal control through drug-responsive designs. The iCRISPRa/i systems fuse mutated human estrogen receptor (ERT2) domains to CRISPRa components, causing cytoplasmic sequestration until 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) administration induces nuclear translocation [11]. These systems show rapid response, reversibility, and lower baseline leakage compared to constitutive expression systems [11].

Complex Model Systems: CRISPRa implementation has expanded to physiologically relevant models including primary human 3D organoids. In gastric organoid models, doxycycline-inducible dCas9-VPR (iCRISPRa) systems successfully upregulated endogenous genes like CXCR4, with target-positive populations increasing from 13.1% to 57.6% following activation [12]. This demonstrates the efficacy of CRISPRa in challenging, translationally relevant systems.

Bacterial CRISPRa Considerations: Bacterial systems present unique challenges with strict target site requirements. Effective activation in E. coli requires precise positioning (2-4 base windows with 10-11 base periodicity) approximately 80 bases upstream of the transcriptional start site [15]. Successful bacterial CRISPRa also depends on promoter strength, sigma factor compatibility, and intervening sequence composition [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for CRISPRa Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Activators | dCas9-VP64, dCas9-VPR, dCas9-VP64-p65-Rta | Programmable DNA binding and transcriptional activation | Addgene [9] |

| Engineered sgRNAs | MS2-modified sgRNAs (for SAM), standard sgRNAs | Target specification and additional recruiter binding (SAM) | [9] [13] |

| Recruitment Modules | MS2-p65-HSF1 (for SAM), scFv-VP64 (for SunTag) | Enhanced activator recruitment for amplified response | [9] [13] |

| Inducible Systems | ERT2-fused constructs, Tet-On dCas9 | Temporal control of CRISPRa activity | [11] [12] |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral, piggyBac transposon, plasmid systems | Efficient delivery to diverse cell types | [12] |

| Reporter Systems | BFP, GFP, mCherry, luciferase | Quantitative assessment of activation efficiency | [14] |

| Validation Tools | RT-qPCR primers, RNA-seq, Western blot antibodies | Confirmation of transcriptional and translational activation | [12] [13] |

CRISPRa technologies have evolved substantially from the initial dCas9-VP64 design to sophisticated multi-activator systems. The VP64, VPR, and SAM architectures represent distinct approaches to transcriptional activation, each with characteristic strengths and optimal applications. VP64 offers simplicity and reliable delivery, VPR provides balanced potency with reduced complexity, and SAM delivers maximal activation at the cost of increased component complexity.

Future developments will likely focus on enhancing precision, reducing off-target effects, and improving in vivo delivery efficiency. The integration of CRISPRa with single-cell technologies and advanced model systems like human organoids will expand its applications in functional genomics and therapeutic development [12] [14]. As these tools mature, they will increasingly enable researchers to precisely manipulate transcriptional programs in both basic research and clinical applications, providing powerful capabilities to complement the CRISPRi toolkit for comprehensive gene regulation.

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has emerged as a powerful genetic tool that enables precise, reversible silencing of gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This technology centers on a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) that serves as a programmable DNA-binding platform. When fused to transcriptional repressor domains and guided to specific genomic loci by a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), dCas9 can effectively suppress transcription [4]. The earliest and most widely adopted repressor domain is the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) from the human protein KOX1, which recapitulates natural heterochromatin formation to silence target genes [16] [17]. However, inconsistent performance across cell lines, gene targets, and guide RNAs has highlighted the need for improved repressors [16]. Recent advances in protein engineering have yielded a new generation of CRISPRi systems with enhanced repression efficacy and reliability. This technical guide explores the mechanistic basis, performance characteristics, and experimental implementation of both established and novel CRISPRi repressor domains, providing researchers with the insights needed to select optimal tools for their specific applications.

Core Mechanisms of CRISPRi Repression

Foundational KRAB Domain Function

The KRAB domain is a potent transcriptional repressor derived from human zinc finger proteins. When dCas9-KRAB is targeted to a promoter or enhancer region, it initiates a native chromatin remodeling process. The KRAB domain recruits the co-repressor KAP1, which in turn assembles a heterochromatin-forming complex containing histone methyltransferases (e.g., SETDB1) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) [17]. This complex catalyzes the deposition of repressive histone marks, primarily H3K9me3, leading to chromatin condensation and transcriptional silencing. Genome-wide studies have confirmed that dCas9-KRAB targeted to distal regulatory elements like the HS2 enhancer in the globin locus specifically induces H3K9me3 at the intended site with minimal off-target effects, demonstrating its precision for epigenetic editing [17].

Novel Repressor Domains and Combinatorial Approaches

Research has revealed that KRAB domains from different human proteins exhibit varying repression potencies. For instance, the ZIM3(KRAB) domain demonstrates significantly stronger silencing activity than the historically used KOX1(KRAB) [16] [18]. Beyond KRAB domains, other potent repressor modules include:

- MeCP2(t): A truncated 80-amino acid version of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 that interacts with Sin3A and histone deacetylases [16]

- SCMH1, CTCF, and RCOR1: Non-KRAB domains identified through systematic screening with repressive activity exceeding canonical MeCP2 [16]

- MAX: A transcriptional regulator that functions effectively in combinatorial repressors [16]

Combinatorial fusion of multiple repressor domains to dCas9 creates synergistic effects that enhance gene knockdown. Engineering efforts have produced bipartite and tripartite repressors such as dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) and dCas9-ZIM3-NID-MXD1-NLS, which show substantially improved repression across diverse cell lines and target genes [16] [19].

Table 1: Key CRISPRi Repressor Domains and Their Characteristics

| Repressor Domain | Type | Size (aa) | Key Mechanisms | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KOX1(KRAB) | KRAB | ~45 | Recruits KAP1, SETDB1, HDACs, H3K9me3 | Foundational domain, moderate silencing |

| ZIM3(KRAB) | KRAB | ~45 | Enhanced KRAB activity | Superior to KOX1(KRAB) in silencing [16] [18] |

| MeCP2 (full) | Non-KRAB | 283 | Binds Sin3A/HDAC complex | Improves silencing in fusion proteins [16] |

| MeCP2(t) | Non-KRAB | 80 | Compact repressor core | Performance similar to full MeCP2 [16] |

| SCMH1 | Non-KRAB | Varies | Chromatin association | Outperforms MeCP2 in initial screens [16] |

| RCOR1 | Non-KRAB | Varies | Corepressor for REST complex | Novel repressor with strong activity [16] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison of CRISPRi Systems

Systematic Screening and Validation

Recent large-scale screening approaches have enabled the direct comparison of CRISPRi repressor efficacy. One comprehensive study screened >100 bipartite and tripartite repressor fusion proteins in HEK293T cells using an eGFP reporter system to quantify knockdown efficiency [16]. This systematic approach identified several novel repressor combinations that significantly outperformed gold standard systems like dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB). The top-performing variants included dCas9-KRBOX1(KRAB)-MAX, dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MAX, and dCas9-KOX1(KRAB)-MeCP2(t), which improved gene knockdown by approximately 20-30% compared to dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB) alone [16]. Notably, the dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2 combination – while highly effective – was identified as a previously characterized system, highlighting the importance of proper attribution in technology development [20].

Further engineering optimization has included nuclear localization signal (NLS) configuration, with the addition of a carboxy-terminal NLS enhancing gene knockdown efficiency by an average of ~50% [19]. The current state-of-the-art system, dCas9-ZIM3-NID-MXD1-NLS, incorporates an optimized MeCP2 NID truncation domain with additional repressor elements and proper localization signals to achieve superior silencing capabilities across multiple cell lines and in genome-wide dropout screens [19].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected CRISPRi Repressor Systems

| CRISPRi System | Repressor Architecture | Relative Knockdown Efficiency | Key Advantages | Validation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-KOX1(KRAB) | Single domain | Baseline | Established, well-characterized | Multiple cell lines [16] [17] |

| dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB) | Single domain | ++ vs. KOX1 | Enhanced KRAB activity | HEK293T, stem cells [16] |

| dCas9-KOX1(KRAB)-MeCP2 | Bipartite | +++ vs. single domain | Synergistic repression | Gold standard [16] |

| dCas9-ZIM3-MeCP2 | Bipartite | ++++ vs. single domain | Potent long-term silencing | Previously characterized [20] |

| dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MAX | Bipartite | +20-30% vs. ZIM3 | Novel effective combination | HEK293T reporter [16] |

| dCas9-KOX1(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) | Bipartite | +20-30% vs. ZIM3 | Compact, highly efficient | HEK293T reporter [16] |

| dCas9-ZIM3-NID-MXD1-NLS | Optimized bipartite | +50% with NLS | Superior silencing, optimized | Multiple cell lines, genome-wide screens [19] |

Cell Type-Specific Performance Considerations

CRISPRi performance varies across cellular contexts, influencing repressor selection for specific applications. Studies comparing induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), neural progenitors, and differentiated cells have revealed distinct dependencies on translation machinery genes when targeted with the same dCas9-KRAB system [21]. For instance, iPSCs demonstrated higher sensitivity to mRNA translation perturbations compared to differentiated cell types, potentially reflecting their elevated global protein synthesis rates [21]. These findings underscore that optimal CRISPRi repressor choice may depend on the specific biological context, with certain cell types potentially requiring enhanced repressor systems for effective gene knockdown.

Experimental Design and Implementation

Delivery Methods for CRISPRi Systems

Effective delivery of CRISPRi components is crucial for successful gene silencing. Multiple delivery strategies have been developed, each with distinct advantages:

- Lentiviral Transduction: Enables stable integration and long-term expression, ideal for pooled screens and chronic knockdown studies. Used in the Virtual Cell Challenge with dual-guide designs to ensure strong and consistent knockdown [22].

- Virus-Like Particles (VLPs): The RENDER platform (Robust ENveloped Delivery of Epigenome-editor Ribonucleoproteins) facilitates transient delivery of CRISPRi ribonucleoprotein complexes, minimizing off-target exposure and enabling editing in hard-to-transfect cells, including primary T cells and neurons [18].

- Plasmid Transfection: Suitable for transient expression in easily transfectable cell lines like HEK293T, commonly used for initial system validation [16].

Recent advances in VLP delivery have demonstrated efficient packaging and transfer of various CRISPRi effectors, with the ZIM3 KRAB domain showing higher epigenetic silencing compared to KOX1 within CRISPRi-eVLPs [18]. This delivery method is particularly valuable for therapeutic applications where transient editor expression is desirable.

Guide RNA Design and Target Selection

Effective CRISPRi requires careful sgRNA design with particular attention to:

- Target Location: sgRNAs should bind to promoter regions or transcriptional start sites (TSS), though these are not always well-annotated in the genome [4]. For enhancer targeting, coverage across the core regulatory region (e.g., 400bp for HS2 enhancer) with multiple sgRNAs is recommended [17].

- Dual-guide Designs: Empirical data shows that expressing two guides per target gene from the same vector significantly improves knockdown consistency and efficacy compared to single-guide approaches [22].

- Nucleosome Positioning: Histone-DNA binding can impede dCas9 access, necessitating consideration of chromatin accessibility in guide design [23].

- Specificity Controls: Include non-targeting sgRNAs and target-negative cell lines to distinguish specific effects from background [17].

Validation and Optimization Methodologies

Rigorous validation of CRISPRi systems involves multiple complementary approaches:

- Reporter Assays: Fluorescent reporters (e.g., eGFP) under control of targeted promoters enable rapid quantification of knockdown efficiency via flow cytometry [16].

- Endogenous Gene Analysis: qRT-PCR and RNA-seq measure transcript-level changes, while western blotting and flow cytometry assess protein knockdown [16] [17].

- Epigenetic Modification Tracking: Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for H3K9me3 and other repressive marks confirms expected mechanism of action [17].

- Phenotypic Characterization: Growth assays following essential gene knockdown and genome-wide dropout screens validate functional impact [16] [21].

The Virtual Cell Challenge established rigorous evaluation metrics including Differential Expression Score (DES), Perturbation Discrimination Score (PDS), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) that provide standardized frameworks for assessing CRISPRi performance [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for CRISPRi Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Repressor Fusions | dCas9-KOX1(KRAB), dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB), dCas9-ZIM3-MeCP2, dCas9-ZIM3-NID-MXD1-NLS | Core effector proteins; selection depends on required knockdown strength |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral constructs with dual-guide expression, Plasmid vectors for transient expression, VLP systems for RNP delivery | Determine expression stability and duration |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T (validation), K562 (erythroid models), H1 ESCs (pluripotent models), iPSC-derived lineages | Impact repressor performance; choose biologically relevant models |

| Validation Tools | qPCR primers for target genes, RNA-seq libraries, Flow cytometry antibodies, Western blot antibodies | Essential for quantifying knockdown at transcript and protein levels |

| Control Reagents | Non-targeting sgRNAs, dCas9-only constructs, Untargeted cell lines, Expression markers (mCherry) | Critical for establishing specificity and normalization |

The CRISPRi landscape continues to evolve with several promising research directions. First, the engineering of compact, highly efficient repressor domains like MeCP2(t) (80aa) addresses the packaging constraints of viral delivery systems, particularly AAVs with limited cargo capacity [16] [18]. Second, transient delivery methods like the RENDER platform enable precise temporal control over gene silencing while minimizing potential off-target effects associated with prolonged editor expression [18]. Third, the application of CRISPRi to increasingly complex biological systems, including patient-derived primary cells and organoid models, will further elucidate cell-type-specific genetic dependencies [21] [18].

The development of novel repressor domains beyond KRAB represents a significant advancement in CRISPRi technology. While KRAB-based systems remain valuable for many applications, new combinatorial repressors like dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) and dCas9-ZIM3-NID-MXD1-NLS offer substantially enhanced performance with reduced variability across guide RNAs and cellular contexts [16] [19]. These improved tools provide researchers with more reliable and potent options for probing gene function, conducting genetic screens, and developing potential therapeutic applications. As the CRISPRi toolbox continues to expand, careful consideration of repressor selection, delivery method, and experimental design will ensure optimal outcomes for specific research objectives.

In the realm of CRISPR-based transcriptional regulation, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and interference (CRISPRi) have emerged as powerful tools for precise gene expression control. While both systems utilize a guide RNA (gRNA) and a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) to target specific genomic loci, their functional outcomes are diametrically opposed. The strategic design of the gRNA is the paramount factor determining the success of either approach. gRNA targeting is not a one-size-fits-all process; optimal sequences for activation differ significantly from those for repression. This guide details the key differences in gRNA design principles for CRISPRa and CRISPRi, providing researchers with a framework for effective experimental implementation within the broader context of programmable transcription factors.

Fundamental Mechanisms: How gRNA Targeting Directs Activation and Repression

The core difference between CRISPRa and CRISPRi lies in the effector domain fused to the dCas9 protein. Despite this difference, both systems rely entirely on the gRNA for DNA binding and specificity.

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) Mechanism

In CRISPRi, the dCas9 protein is typically fused to a repressor domain such as the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) [11] [4]. The gRNA-dCas9 complex binds to the target DNA, and the KRAB domain recruits additional proteins that establish a transcriptionally silent heterochromatin state, effectively shutting down gene expression [4]. The binding location of the gRNA is critical for effective repression. The most effective CRISPRi occurs when the gRNA targets a region that physically blocks the binding or progression of RNA polymerase (RNAP). This is typically achieved by designing gRNAs to bind within a window of -50 to +300 nucleotides relative to the transcription start site (TSS), with the most potent repression often occurring when targeting the region immediately downstream of the TSS [4].

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) Mechanism

Conversely, CRISPRa employs a dCas9 protein fused to transcriptional activator domains, such as VP64, VP64-p65-Rta (VPR), or components of the Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) system [24] [25] [4]. The gRNA directs this complex to the promoter region of a target gene, where the activation domain recruits the cellular transcription machinery to initiate gene expression. For CRISPRa, gRNA binding location is even more constrained. Effective activation requires targeting upstream regulatory elements, typically in the region between -200 and -500 base pairs upstream of the TSS [26]. This positioning is believed to mimic natural enhancer elements, allowing the activator domains to interact effectively with the basal transcription apparatus at the core promoter.

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanistic differences and optimal gRNA binding sites for CRISPRa and CRISPRi.

Comparative gRNA Design Principles: A Detailed Analysis

The divergent mechanisms of CRISPRa and CRISPRi necessitate distinct gRNA design strategies. The table below summarizes the critical differences in gRNA targeting parameters for the two systems.

Table 1: Key gRNA Design Parameters for CRISPRa vs. CRISPRi

| Design Parameter | CRISPRa (Activation) | CRISPRi (Interference) |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Target Region | Upstream of TSS (-200 to -500 bp) [26] | Overlapping or downstream of TSS (-50 to +300 bp) [4] |

| Primary Goal | Recruit transcriptional machinery | Sterically hinder RNA polymerase |

| gRNA Efficiency | Highly variable; depends on local chromatin state [4] | Generally high and more consistent |

| Specificity Concerns | Potential for inadvertent enhancer effects | Blocking expression of overlapping genes |

| Multiplexing Strategy | qgRNAs (4 guides/gene) significantly boost efficacy [27] | Often effective with a single guide, but multiples enhance robustness |

A leading cause of failed CRISPRa experiments is the use of gRNAs designed with CRISPRi principles. The most critical distinction is the target location relative to the TSS. A gRNA designed for CRISPRi that binds downstream of the TSS will be ineffective for CRISPRa, as this location is not conducive to recruiting activators to the promoter. Furthermore, the inherent openness of the chromatin at the target site is a more significant factor for CRISPRa than for CRISPRi. A gRNA targeting a region in tightly packed heterochromatin may fail to activate transcription, even if its sequence is perfectly designed, because the dCas9-activator complex cannot access the DNA [4].

Advanced Strategies and Quantitative Performance

Enhancing Efficiency with Multiplexed gRNAs

For CRISPRa, using multiple gRNAs (multiplexing) per gene is highly advantageous. Single sgRNAs often induce variable and low-level gene activation [27]. A powerful solution is the use of quadruple-guide RNA (qgRNA) vectors, where a single plasmid expresses four distinct sgRNAs targeting the same gene. Research has demonstrated that this approach massively increases target gene activation compared to individual sgRNAs, delivering more robust and consistent results [27]. This synergistic effect is less critical for CRISPRi, which can be highly effective with a single, well-chosen gRNA, though multiplexing can still ensure complete repression.

Orthogonal Systems for Simultaneous Application

A cutting-edge application involves using CRISPRa and CRISPRi simultaneously within the same cell. This requires orthogonal CRISPR systems to prevent cross-talk. For example, a study used dSpCas9-VPR for activation and dSaCas9-KOX1 for repression, exploiting the fact that the gRNAs for these different Cas9 orthologs are not interchangeable [24]. This allows for concurrent activation of one gene and repression of another in a single experiment, enabling complex genetic engineering workflows.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Optimized CRISPRa/i Systems

| Application | System Used | Reported Efficiency | Key Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRa | dCas9-VPR with qgRNAs | Up to 98% positive cells for surface markers (e.g., CD123) [24] | Flow cytometry on primary human T cells |

| CRISPRi | dSaCas9-KOX1 | ~5% of CD5-positive cells remaining [24] | Flow cytometry on Jurkat cells |

| Genome-wide Screening | dxCas9-CRP dual-mode system | Coordinated activation/repression increased violacein production [26] | Fluorescent reporters and metabolite production in E. coli |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for gRNA Design and Validation

Implementing a successful CRISPRa or CRISPRi experiment requires a structured workflow. The following diagram and detailed protocol outline the key steps from initial design to final validation.

Step 1: Annotate the Transcription Start Site (TSS). Precise TSS annotation is the most critical step. Use curated databases like RefSeq to identify the canonical TSS for your gene of interest. An error of even 100 base pairs can determine the success or failure of the experiment.

Step 2: Define the gRNA Target Window. Based on the chosen modality (CRISPRa or CRISPRi), define the genomic search window. For CRISPRa, scan the region from -200 to -500 bp upstream of the TSS. For CRISPRi, scan the region from -50 to +300 bp around the TSS.

Step 3: Design and Select gRNA Sequences. Within the target window, identify all possible gRNA sequences with appropriate PAM sites (e.g., NGG for SpCas9). Use modern design algorithms (e.g., from platforms like Synthego) that incorporate rules for specificity and on-target efficiency [4]. For CRISPRa, design 3-4 non-overlapping gRNAs per gene to be used in a qgRNA vector for maximal effect [27].

Step 4: Select and Synthesize Guides. For the highest editing efficiency and lowest off-target effects, synthetic, chemically modified sgRNAs in a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) format are the preferred choice [28]. This avoids the variability and potential toxicity associated with plasmid-based expression.

Step 5: Deliver System and Validate Targeting. Co-deliver the dCas9-effector (as mRNA or protein) and the sgRNA(s) into your target cells. Validate successful on-target binding and transcriptional modulation 48-72 hours post-delivery by measuring changes in mRNA levels using quantitative RT-PCR.

Step 6: Conduct Functional Phenotypic Assay. The final step is to link the transcriptional change to a functional phenotype. This can be assessed by flow cytometry (for surface proteins), immunoblotting (for protein levels), or a specific functional assay (e.g., metabolite production or drug resistance) [26] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPRa/i Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Effector Fusions | Targetable transcription core; defines a/i function | dCas9-VPR (for CRISPRa), dCas9-KRAB (for CRISPRi) [24] [4] |

| gRNA Expression Format | Determines specificity and delivery efficiency | Synthetic sgRNA (RNP format recommended for high efficiency) [28] |

| qgRNA Vectors | Plasmid expressing 4 guides for synergistic activation | Significantly boosts CRISPRa efficacy versus single guides [27] |

| Orthogonal Cas Proteins | Enable simultaneous a/i in one cell; prevent cross-talk | dSpCas9 for activation + dSaCas9 for repression [24] |

| Delivery Method | Critical for primary and hard-to-transfect cells | Electroporation of RNP complexes is highly effective [24] |

| Inducible Systems | Provide temporal control over CRISPRa/i activity | ERT2-based iCRISPRa/i systems activated by 4OHT [11] |

The precision of gRNA targeting is the cornerstone of effective CRISPRa and CRISPRi experiments. The fundamental distinction—targeting upstream promoter regions for activation versus the core promoter/TSS region for repression—must guide all experimental design. By adhering to these specialized principles, employing multiplexed gRNAs for activation, and leveraging orthogonal systems for complex manipulations, researchers can fully harness the power of programmable transcription to dissect gene function and engineer novel cellular phenotypes. As the field advances, continued optimization of gRNA design and delivery will further solidify CRISPRa and CRISPRi as indispensable tools in functional genomics and therapeutic development.

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) are powerful technologies derived from the CRISPR-Cas9 system that enable precise transcriptional control without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These systems utilize a catalytically inactive or "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) that retains its ability to bind DNA target sites specified by a guide RNA (sgRNA) but does not cleave the DNA. The fundamental distinction between CRISPRa and CRISPRi lies in the effector domains fused to dCas9: CRISPRa employs transcriptional activators to increase gene expression, whereas CRISPRi uses repressors to decrease it. While in vitro applications of these tools are well-established, their function in vivo—particularly the critical processes of nuclear translocation and complex assembly—presents unique challenges and considerations for therapeutic development. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for applying CRISPRa/i to gene therapy, functional genomics, and the treatment of complex diseases in living organisms.

Core Mechanisms of Nuclear Translocation

For CRISPRa/i systems to function, the dCas9-effector fusion proteins must efficiently localize to the nucleus where they can access genomic DNA. This process of nuclear translocation is a critical regulatory point, especially for in vivo applications.

The Challenge of Cytoplasmic Sequestration

In the context of in vivo models, a significant barrier to nuclear import is the sequestration of CRISPR components in the cytoplasm. Research has shown that the use of nuclear localization signals (NLS) is a standard method to facilitate nuclear import. However, a more sophisticated, controllable method involves fusing the CRISPRa/i components to a mutated human estrogen receptor (ERT2) domain. This ERT2 domain causes the fusion protein to be sequestered in the cytoplasm through interaction with heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), effectively preventing its uncontrolled entry into the nucleus [11].

Inducible Nuclear Translocation

The ERT2-based system provides a drug-inducible mechanism for nuclear translocation. Upon administration of an estrogen analogue such as 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4OHT), the conformational change of the ERT2 domain disrupts its interaction with HSP90. This disruption releases the CRISPRa/i fusion protein, allowing its subsequent translocation into the nucleus [11]. A specific system named iCRISPRa/i, which features two ERT2 domains at the N-terminus and one at the C-terminus of the CRISPRa/i construct, demonstrates rapid and efficient nuclear translocation upon 4OHT induction. This process is reversible; upon withdrawal of 4OHT, the system can be restored to its original state, highlighting its potential for precise temporal control of gene expression in vivo [11].

Table: Key Systems for Controlling Nuclear Translocation In Vivo

| System Name | Inducing Molecule | Core Mechanism | Effect on Translocation | Reversibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iCRISPRa/i [11] | 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4OHT) | ERT2 domain fusion; dissociation from HSP90 complex | Drug-induced nuclear import | Yes |

| CRISPR-StAR [29] | Tamoxifen (for Cre-ERT2) | Cre recombinase-mediated sgRNA activation | Controls functional sgRNA assembly in the nucleus | No (irreversible recombination) |

Nuclear Entry in Therapeutic Delivery

The mode of delivery for CRISPR components significantly impacts nuclear translocation in vivo. For instance, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) used for systemic delivery tend to naturally accumulate in liver cells. Once inside hepatocytes, the Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA are released into the cytoplasm, where the mRNA is translated into protein. The resulting dCas9-effector fusion proteins, equipped with NLSs, are then actively imported into the nucleus [30]. This principle is leveraged in several ongoing clinical trials for liver-specific diseases [30] [31].

Assembly of Functional Complexes In Vivo

Once inside the nucleus, the dCas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complex must locate and bind its target DNA sequence. Subsequently, the transcriptional effector domains must recruit the cellular machinery to either activate or repress gene expression.

CRISPRi Complex Assembly and Repression Mechanism

CRISPRi complexes are typically formed by fusing dCas9 to a transcriptional repressor domain, most commonly the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) domain. The assembled dCas9-KRAB/sgRNA complex binds to the promoter region of a target gene, typically within a window from -50 to +300 base pairs relative to the transcriptional start site (TSS), with the most effective binding sites often located just downstream of the TSS [32]. The KRAB domain then recruits co-repressors and histone-modifying enzymes that promote the formation of heterochromatin—a compact, transcriptionally silent form of DNA—thereby effectively interfering with the initiation and elongation of transcription by RNA polymerase [4] [5].

CRISPRa Complex Assembly and Activation Mechanism

CRISPRa systems are designed to recruit multiple transcriptional activator domains to a gene's promoter. Simple CRISPRa systems involve direct fusion of activator domains like VP64 to dCas9. However, more powerful and sophisticated systems have been developed to achieve robust gene activation in vivo. The primary strategies include:

- Direct Fusions: Such as dCas9-VPR, a tripartite fusion of VP64, p65, and Rta transactivator domains [11] [5].

- Protein Scaffolds: Such as the SunTag system, where dCas9 is fused to a peptide array that recruits multiple copies of antibody-activator fusions [4] [5].

- RNA Scaffolds: Such as the Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM), where engineered sgRNAs contain RNA aptamers that recruit additional activator proteins like p65 and HSF1 [5] [32].

For effective activation, the CRISPRa complex must bind upstream of the TSS, typically within the -400 to -50 bp window [32]. Once bound, the activator domains recruit co-activators and the general transcription machinery to initiate gene expression.

Advanced Systems for Controlled Assembly In Vivo

Novel screening systems like CRISPR-StAR (Stochastic Activation by Recombination) demonstrate sophisticated control over functional complex assembly in complex in vivo models, such as tumors in mice [29]. This system uses a Cre-lox mechanism to stochastically and irreversibly generate either an active or an inactive sgRNA configuration within each single-cell-derived clone. This design creates an internal control by ensuring that within each clone, a population of cells with active sgRNAs is intermingled with a corresponding wild-type population carrying the identical sgRNA in an inactive state. This internal control accounts for both intrinsic cellular heterogeneity and extrinsic microenvironmental factors, allowing for high-resolution genetic screening in vivo by comparing cells with active versus inactive sgRNAs within the same clonal population and microenvironment [29].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows and logical relationships of inducible CRISPRa/i systems for in vivo application.

Quantitative Data and Experimental Comparisons

The functionality of CRISPRa/i systems in vivo is quantifiable through various metrics, including efficiency, specificity, and dynamic range.

Table: Quantitative Comparison of CRISPRa/i Performance In Vivo

| Parameter | CRISPRi (dCas9-KRAB) | CRISPRa (e.g., dCas9-VPR/SAM) | Inducible System (iCRISPRa/i) | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repression/Efficiency | Up to 80-90% repression [4] [5] | Up to several hundred-fold activation [5] [32] | Comparable to non-inducible counterparts [11] | Endogenous gene regulation in cell lines & mouse models |

| Targeting Window | -50 to +300 bp from TSS [32] | -400 to -50 bp from TSS [32] | N/A (same as fused effector) | Optimal sgRNA binding region for efficacy |

| Leakiness | Variable (constitutive systems) | Variable (constitutive systems) | Lower leakage [11] | Basal activity in the absence of induction |

| Response Time | Hours to days (constitutive) | Hours to days (constitutive) | Fast drug response [11] | Time from induction to detectable transcriptional change |

| Reversibility | Limited (requires degradation of components) | Limited (requires degradation of components) | Reversible upon 4OHT withdrawal [11] | Ability to return to basal expression state |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for In Vivo Study

To investigate nuclear translocation and complex assembly in vivo, robust experimental methodologies are required. The following protocol details the use of the iCRISPRa/i system, incorporating key steps for controlled nuclear import.

Protocol: Evaluating Inducible CRISPRa/i in a Mouse Model

This protocol outlines the steps to test the functionality of an ERT2-based inducible CRISPRa/i system, such as iCRISPRa/i, in a murine model, with a focus on tracking nuclear translocation and transcriptional outcomes [11].

Materials:

- Plasmids:

pHR-CMV-iCRISPRa/i-2A-mCherry(for expressing the inducible dCas9-effector) andpU6-sgRNA-EF1Alpha-puro-T2A-BFP(for expressing the sgRNA). - Cell line: e.g., B16 murine melanoma cells or NIH/3T3 cells.

- Inducer: 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4OHT) prepared in an appropriate vehicle (e.g., corn oil).

- Animal Model: Immunocompromised mice (e.g., NSG) for xenograft studies.

- Analytical Tools: Immunofluorescence microscopes, flow cytometer, RNA extraction kit, qPCR system.

Procedure:

- Stable Cell Line Generation:

- Co-transduce target cells (e.g., B16) with lentivirus produced from the

pHR-CMV-iCRISPRa/i-2A-mCherryplasmid and thepU6-sgRNAplasmid. - Select successfully transduced cells using antibiotics (e.g., puromycin) and/or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for mCherry and BFP markers.

- Validate the cytoplasmic localization of the iCRISPRa/i fusion protein in the absence of 4OHT via immunofluorescence staining against the myc-His tag or the mCherry reporter.

- Co-transduce target cells (e.g., B16) with lentivirus produced from the

In Vivo Tumor Engraftment and Induction:

- Subcutaneously inject ~1 million stable cells into the flanks of mice.

- Allow tumors to establish to a palpable size (~100-150 mm³).

- Randomize mice into two groups: experimental and control.

- Administer 4OHT (e.g., 2 mg/dose via intraperitoneal injection) to the experimental group. The control group receives the vehicle only.

Monitoring Nuclear Translocation:

- At various time points post-induction (e.g., 6, 12, 24 hours), harvest tumors from a subset of animals from each group.

- Fix tumor tissue sections and perform immunofluorescence staining for the dCas9-effector fusion protein and a nuclear marker (e.g., DAPI).

- Image using confocal microscopy to qualitatively and quantitatively assess the shift in protein localization from the cytoplasm to the nucleus upon 4OHT administration.

Assessing Transcriptional and Phenotypic Outcomes:

- Harvest tumor tissues at a later time point (e.g., 48-72 hours post-induction) to assess downstream effects.

- Gene Expression Analysis: Extract total RNA from tumor tissue, reverse transcribe to cDNA, and perform qPCR to measure the mRNA levels of the target gene(s). Compare the 4OHT-induced group to the vehicle control group.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Measure tumor growth characteristics or other relevant phenotypic changes (e.g., melanin synthesis in B16 models) over time.

Protocol: Internally Controlled Screening with CRISPR-StAR

The CRISPR-StAR protocol is designed for high-resolution genetic screening in complex in vivo environments like tumors, providing a robust method to control for heterogeneity [29].

Procedure:

- Library Cloning and Cell Preparation:

- Clone an sgRNA library (e.g., targeting 1,245 genes) into the CRISPR-StAR backbone, which contains a Cre-inducible, barcoded sgRNA expression cassette.

- Transduce a Cas9- and Cre-ERT2-expressing cell line (e.g., mouse melanoma cells) with the lentiviral library at high coverage (>500 cells per sgRNA).

In Vivo Engraftment and Clonal Expansion:

- Inject transduced cells into mouse models and allow tumors to develop. The engraftment process creates a natural bottleneck, resulting in tumors derived from a few thousand clones, each marked by a unique barcode.

Induction of Stochastic sgRNA Activation:

- Once tumors are established, administer tamoxifen to activate the nuclear Cre-ERT2. This stochastically and irreversibly generates two populations within each single-cell-derived clone: one with active sgRNAs and one with inactive sgRNAs, serving as an internal control.

Analysis and Hit Calling:

- Harvest tumors and extract genomic DNA.

- Amplify and sequence the sgRNA and barcode regions.

- For each unique barcode (clone), compare the abundance of the active sgRNA conformation to the inactive one. This internal comparison controls for clonal variability and microenvironmental effects.

- Genes are identified as hits (e.g., essential for in vivo growth) if their active sgRNAs are significantly depleted compared to the internal control across many independent clones.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for In Vivo Studies

Table: Key Research Reagents for Investigating CRISPRa/i Function In Vivo

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Effector Plasmids | Core protein component for transcription modulation. | pcDNA3.1-CMV-CRISPRa/i-myc-His for constitutive expression; pHR-CMV-iCRISPRa/i-2A-mCherry for inducible expression [11]. |

| Inducible Systems (ERT2) | Enables drug-controlled nuclear translocation. | Fusing ERT2 domains to CRISPRa/i components for 4OHT-inducible nuclear import [11]. |

| sgRNA Expression Vectors | Delivers targeting specificity to the genomic locus. | pU6-sgRNA EF1Alpha-puro-T2A-BFP for co-expression of a selection marker [11]. |

| Cre-lox Systems | Allows irreversible, stochastic activation of genetic elements. | CRISPR-StAR vector for creating internal control populations during in vivo screening [29]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery vehicle for CRISPR components. | Systemic delivery of Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA to liver cells for gene regulation [30]. |

| 4-Hydroxy-Tamoxifen (4OHT) | Small-molecule inducer for ERT2-based and Cre-ERT2 systems. | Activating nuclear translocation of iCRISPRa/i or inducing recombination in CRISPR-StAR [11] [29]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | DNA barcodes for tracking clonal populations. | Tracing the origin and expansion of single cells in complex in vivo models like tumors [29]. |

From Bench to Bedside: Experimental Design and Translational Applications

Within the expanding CRISPR toolkit, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) have emerged as powerful technologies for the precise, reversible modulation of gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These techniques are foundational for functional genomics screens, target validation, and elucidating complex gene networks in drug discovery. Their efficacy, however, is profoundly dependent on one critical factor: the precise genomic positioning of the guide RNA (gRNA). This technical guide delineates the optimal gRNA design windows—targeting -400 to -50 bp for CRISPRa and -50 to +300 bp for CRISPRi—framing them within the context of their distinct mechanistic operations. A thorough grasp of these principles is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to harness these technologies for robust and reproducible scientific and therapeutic outcomes [32].

Core Principles: Mechanisms of CRISPRa and CRISPRi

Both CRISPRa and CRISPRi utilize a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) variant, which retains its programmable DNA-binding capability but is incapable of cleaving the DNA backbone [4] [32]. The fundamental difference lies in the effector domains fused to dCas9, which dictate transcriptional outcome.

- CRISPRi (Interference): This approach represses gene transcription. The most common system fuses dCas9 to a transcriptional repressor domain, most frequently the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) [5] [32]. When guided to a target site, the dCas9-KRAB complex recruits additional proteins that promote the formation of heterochromatin—a tightly packed, transcriptionally silent form of DNA—thereby sterically hindering the binding and progression of RNA polymerase [5] [4].

- CRISPRa (Activation): This approach enhances gene transcription. Simple fusions of dCas9 to a single activator domain (e.g., VP64) often yield modest activation [5]. More advanced, highly effective systems, such as the Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM), employ sophisticated protein or RNA scaffolds to recruit multiple, distinct transcriptional activator domains (e.g., VP64, p65, HSF1) to the promoter region, leading to robust gene upregulation [5] [32].

Optimal gRNA Design Windows: A Quantitative Guide

The mechanistic differences between CRISPRa and CRISPRi necessitate distinct gRNA positioning strategies relative to the Transcription Start Site (TSS). The TSS is the reference point (0 bp) from which all targeting positions are measured, and accurate TSS annotation, using databases like FANTOM, is critical for success [33].

Table 1: Optimal gRNA Design Windows for CRISPRa and CRISPRi

| Parameter | CRISPRa (Activation) | CRISPRi (Interference) |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Targeting Window | -400 to -50 bp upstream of the TSS [34] [32] | -50 to +300 bp relative to the TSS [34] [32] |

| Mechanistic Rationale | Positions activators within the core promoter region to efficiently recruit the transcriptional machinery [32]. | For maximal efficiency, best-performing gRNAs target the first 100 bp downstream of the TSS [32]. This blocks the binding or elongation of RNA polymerase [4]. |

| Key Consideration | Alternative or poorly annotated TSSs can complicate design [34]. | Alternative TSSs can complicate design [34]. Off-targets near other genes' TSSs are a concern [34]. |

Experimental Protocol for gRNA Design and Screening

The following workflow provides a detailed methodology for designing and executing a CRISPRa or CRISPRi experiment, from initial gRNA selection to final validation.

gRNA Design and Library Preparation

- TSS Identification: For the gene of interest, determine the precise TSS using a reliable database such as FANTOM, which uses CAGE-seq data for accurate mapping [33].

- gRNA Selection: Using a specialized design tool (see Section 5), generate a list of candidate gRNAs that fall within the optimal windows specified in Table 1. For CRISPRa, focus on the region from -400 to -50 bp upstream. For CRISPRi, prioritize the region from -50 to +300 bp, with the highest efficacy often found within the first +100 bp downstream of the TSS [32].

- Sequence Optimization: Filter candidate gRNAs using on-target efficacy prediction algorithms (e.g., Doench rules) [35]. Avoid gRNAs with long homopolymers (e.g., AAAA) and those with high sequence similarity to off-target genomic sites [32].

- Library Cloning: Clone the selected gRNA sequences into an appropriate sgRNA expression vector. Ensure the gRNA sequence itself does not contain unintended restriction sites used for cloning or promoter terminator sequences [34].

Cell Line Engineering and Screening

- Generate Helper Cell Line: Create a stable cell line expressing the dCas9-effector fusion (e.g., dCas9-KRAB for CRISPRi or the SAM complex for CRISPRa). Lentiviral transduction is the most consistent method for achieving robust and uniform expression [32].

- Deliver gRNA Library: Transduce the helper cell line with the pooled sgRNA lentiviral library at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) to ensure most cells receive only one sgRNA [5].

- Apply Selective Pressure: Culture the transduced cells and subject them to the relevant phenotypic screen, such as cell growth/proliferation, sensitivity to a drug or toxin, or a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based assay [5].

- Sequence and Analyze:

- At the beginning (t0) and end of the experiment, harvest cells and isolate genomic DNA.

- PCR-amplify the integrated sgRNA locus and subject the products to next-generation sequencing.

- Quantify the enrichment or depletion of each sgRNA in the final population compared to t0. sgRNAs that confer a selective advantage or disadvantage will be significantly enriched or depleted, respectively, pointing to genes involved in the screened phenotype [5].

Validation

- Essential Step: Never base conclusions on a single gRNA. The gold standard for validation is to demonstrate that multiple, independent gRNAs targeting the same gene produce the same phenotypic effect, confirming an on-target result [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of CRISPRa/i screens relies on a suite of key reagents and bioinformatic tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPRa/i Experiments

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Effector Systems | dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi), SAM, VPR, SunTag (CRISPRa) | The core protein complex that determines transcriptional outcome (repression or activation) [5] [32]. |

| gRNA Design Tools | CHOP-CHOP [34] [36], CRISPR-ERA [34], Benchling [35] [36], E-CRISP [34] | Bioinformatics platforms to design gRNAs within optimal windows, predict on-target efficiency, and minimize off-target effects. |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral sgRNA Vectors | Ensure consistent and efficient delivery of sgRNA constructs into a wide variety of cell types, including hard-to-transfect cells [32]. |

| Analysis Software | MAGeCK, CRISPResso2 [36] | Bioinformatics tools for analyzing next-generation sequencing data from pooled screens to identify hit genes. |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Technologies

Understanding how CRISPRa/i compare to other perturbation technologies highlights their unique advantages and guides technology selection.

- CRISPRi vs. RNAi: Both achieve gene knockdown, but CRISPRi is generally more specific with fewer sequence-based off-target effects. Furthermore, RNAi is primarily effective in the cytoplasm, whereas CRISPRi can efficiently target non-coding RNAs in the nucleus [4] [32].

- CRISPRi vs. CRISPR Nuclease (KO): CRISPR knockout (KO) permanently disrupts a gene, which is ideal for complete LOF studies but can be cytotoxic or lethal for essential genes. CRISPRi offers a reversible, titratable knockdown, making it superior for studying essential genes and providing a better mimic of pharmacological inhibition [4] [32].

- CRISPRa vs. ORF Overexpression: Traditional ORF overexpression uses strong viral promoters to drive supraphysiological expression of a transgenic cDNA. CRISPRa, in contrast, upregulates genes from their native genomic context, preserving physiological splice variants and avoiding positional effects associated with random transgene integration [32].

The precise delineation of gRNA design windows is not a mere suggestion but a foundational requirement for harnessing the full potential of CRISPRa and CRISPRi technologies. Adherence to the -400 to -50 bp window for CRISPRa and the -50 to +300 bp window for CRISPRi, as outlined in this guide, ensures maximal on-target efficacy by aligning the molecular tools with their underlying biological mechanisms. For the drug development community, these precision controls enable the systematic identification of novel therapeutic targets, validation of mechanism of action, and the discovery of resistance pathways through highly robust genetic screens. As these technologies continue to evolve, their strategic application, grounded in sound design principles, will undoubtedly accelerate the pace of discovery and therapeutic innovation.

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) represent powerful technologies for precise transcriptional modulation without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These systems are derived from the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing platform but utilize a catalytically inactive or "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) that retains its DNA-binding capability but lacks endonuclease activity [32]. The dCas9 serves as a programmable scaffold that can be fused to various effector domains to regulate gene expression [23]. When targeted to promoter or enhancer regions by guide RNAs (gRNAs), CRISPRa recruits transcriptional activators to increase gene expression, while CRISPRi recruits repressors to decrease expression [37] [32].

The core distinction between these mechanisms lies in their fused effector domains. For CRISPRi, the most common repressor is the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) domain, which silences gene expression by recruiting chromatin-remodeling factors that promote heterochromatin formation [38] [32]. Additional repressor domains include SID4X [37]. For CRISPRa, common activators include VP64 (a tetramer of the VP16 domain), VP160, p65, and Rta (VP64-p65-Rta or VPR) [37] [23]. More advanced systems like the Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) combine multiple activators (e.g., dCas9-VP64 with MS2-p65-HSF1) for enhanced potency [39].

The effectiveness of CRISPRa and CRISPRi is highly dependent on the delivery system used to introduce these components into target cells. Optimal delivery vehicles must efficiently transport often bulky genetic constructs while maintaining safety and providing appropriate persistence of expression for the intended application [40] [41].

Lentiviral Vectors for CRISPR Delivery

Lentiviral vectors (LVs), particularly those derived from HIV-1, represent one of the primary delivery vehicles for CRISPR/Cas systems due to their ability to carry large and complex transgenes and sustain robust, long-term expression in both dividing and non-dividing cells [40].

Basic Biology and Engineering

Lentiviral vectors are enveloped viruses approximately 100 nm in diameter with a single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 10.7 kb [40]. The engineering of LVs for gene therapy has progressed through several generations focused on improving safety:

- Second-generation systems retained only the essential tat and rev genes from HIV, removing accessory genes to enhance safety and create space for larger inserts [40].

- Third-generation systems further improved safety by eliminating the tat gene and the endogenous promoter harboring the TAR element, instead utilizing heterologous promoters like CMV or RSV [40].

- Fourth-generation systems represent the safest option by splitting gag/pol and rev sequences into separate cassettes [40].

Additional enhancements include the incorporation of the woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE) and central polypurine tract (cPPT) to improve RNA stability, transcription efficiency, and overall viral titer [40].

Life Cycle and Integration

The LV life cycle begins with attachment and entry mediated by envelope-receptor interactions, with VSV-G being the most common envelope used for pseudotyping due to its broad tropism [40]. Following entry and uncoating, reverse transcriptase converts viral RNA to double-stranded DNA, which is then imported into the nucleus via host importin complexes [40]. A key distinction exists between integrase-competent lentiviral vectors (ICLVs), which permanently integrate into the host genome, and integrase-deficient lentiviral vectors (IDLVs), which remain primarily as episomal DNA [40]. IDLVs significantly reduce the risk of insertional mutagenesis while still supporting substantial transgene expression, particularly in non-dividing cells [40] [42].

Stable Cell Line Generation

Lentiviral vectors are particularly valuable for generating stable cell lines expressing CRISPRa/i components. The process typically involves:

- Vector Design: Packaging CRISPRa/i components (dCas9-effector and selection marker) into a lentiviral transfer plasmid [38] [39].

- Virus Production: Transfecting HEK293T packaging cells with the transfer plasmid along with packaging plasmids (psPAX2) and envelope plasmid (pCMV-VSV-G) using transfection reagents like polyethylenimine (PEI) [38].

- Transduction: Incubating target cells with viral supernatant in the presence of polybrene to enhance infection efficiency [38].

- Selection: Treating transduced cells with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., G418, puromycin) for 2-3 weeks to select successfully transduced cells [38].

- Validation: Confirming dCas9-effector expression and functionality through Western blot, qPCR, and reporter assays [38] [39].

Advanced systems incorporate inducible elements, such as tetracycline-responsive (TRE) promoters, allowing controlled expression of dCas9-effectors using doxycycline [38]. The piggyBac transposon system represents an alternative non-viral method for generating stable cell lines, offering higher cargo capacity and the ability to incorporate multiple transgene cassettes within a single vector [39].