CRISPR Biosensors for Pathogen Detection: Principles, Applications, and Future Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive review of CRISPR-based biosensors for pathogen detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

CRISPR Biosensors for Pathogen Detection: Principles, Applications, and Future Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of CRISPR-based biosensors for pathogen detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational molecular mechanisms of key Cas proteins (Cas9, Cas12, Cas13) and their trans-cleavage activities. The scope covers advanced methodological applications, including amplification-based and amplification-free strategies, various readout technologies (fluorescence, colorimetric, electrochemical), and point-of-care device integration. The article also addresses critical troubleshooting aspects such as sensitivity, specificity, and real-world implementation challenges, and offers a comparative validation against traditional methods like PCR and culture, discussing the pathway to clinical adoption.

The Molecular Engine: Understanding CRISPR-Cas Mechanisms for Pathogen Diagnostics

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology, originating from an adaptive immune mechanism in bacteria and archaea, has revolutionized molecular diagnostics by offering unprecedented specificity, programmability, and sensitivity [1] [2] [3]. First identified in Escherichia coli genomes in 1987 and later engineered as a programmable gene-editing tool in 2012, CRISPR has evolved into a transformative diagnostic platform [2]. The pivotal discovery of trans-cleavage activity in Cas12a in 2016 marked a paradigm shift, enabling the development of ultra-sensitive diagnostic tools capable of detecting pathogens at attomolar (aM) concentrations [2] [4]. This historical journey from a prokaryotic defense mechanism to a diagnostic powerhouse underscores its potential to address critical limitations of conventional methods like microbial culture, PCR, and immunological assays, which often require specialized equipment, trained personnel, and extended processing times [1] [2]. Framed within the context of biosensor research for pathogen detection, this article details the practical application of CRISPR-based diagnostics, providing detailed protocols and resource guidance for researchers and drug development professionals.

Molecular Mechanisms and Key Cas Proteins

The core principle of CRISPR-based diagnostics hinges on the programmable, sequence-specific recognition of nucleic acids, followed by the activation of Cas enzyme activity. The system comprises a Cas nuclease and a guide RNA (crRNA), which directs the nuclease to a complementary target sequence [2]. Upon target binding, certain Cas enzymes undergo a conformational change that activates their trans-cleavage activity—a non-specific "collateral" cleavage of surrounding reporter nucleic acids [1] [3]. This collateral activity enables robust signal amplification, forming the basis for highly sensitive detection.

The following table summarizes the characteristics of the main Cas proteins used in pathogen diagnostics.

Table 1: Key Cas Proteins in CRISPR-based Diagnostics

| Characteristic | Cas9 | Cas12a | Cas13 | Cas14 (Cas12f) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | DNA/RNA [1] | DNA/RNA [1] | RNA [1] [3] | ssDNA/dsDNA [1] [3] |

| PAM Requirement | NGG [1] | TTTV, etc. [1] | None [1] | None [1] |

| Trans-cleavage Activity | Non-specific ssDNA [1] | Non-specific ssDNA [1] | Non-specific ssRNA [1] [3] | Non-specific ssDNA [1] |

| Sensitivity | Medium [1] | High [1] | High [1] | High [1] |

| Specificity | High [1] | Medium [1] | Medium [1] | Very High [1] |

| Primary Diagnostic Application | Laboratory research [1] | DNA pathogens [1] | RNA pathogens, viruses [1] | SNP detection, short ssDNA [1] |

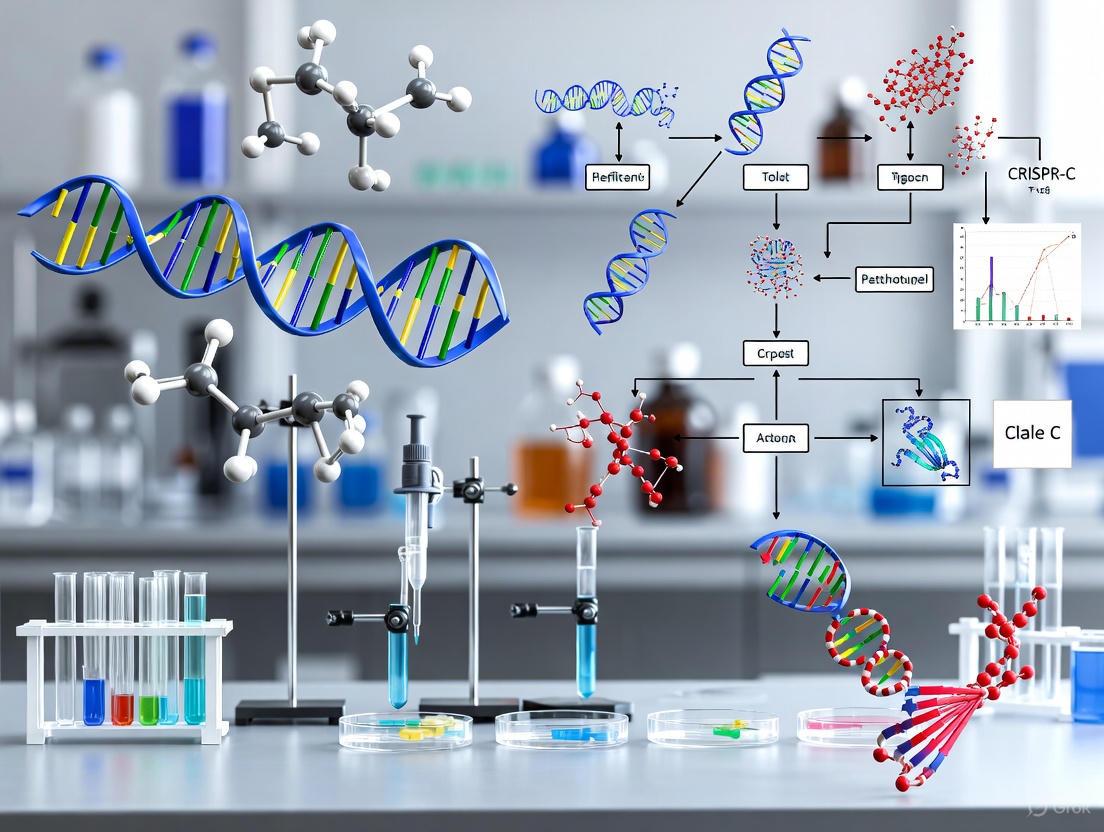

The signaling pathway from target recognition to signal generation is visualized below.

Figure 1: CRISPR Diagnostic Signaling Pathway. The binding of the Cas-crRNA complex to its target pathogen nucleic acid triggers trans-cleavage activity, leading to the cleavage of a reporter molecule and generation of a detectable signal.

Application Note: CRISPR-based Pathogen Detection

Experimental Design and Workflow

CRISPR diagnostics are broadly categorized into amplification-based and amplification-free methods. Amplification-based CRISPR, such as those combined with isothermal amplification techniques like Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) or Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), offers exceptional sensitivity and is ideal for detecting low-abundance pathogens [1]. In contrast, amplification-free CRISPR strategies eliminate nucleic acid amplification steps, reducing operational complexity, potential contamination, and detection time, making them suitable for rapid point-of-care (POC) applications [1] [2]. Examples include cascade CRISPR systems, sensor technologies, and digital droplet CRISPR [1].

The following workflow diagram and protocol outline a standard two-step amplification-based CRISPR detection method, which provides a balance of high sensitivity and robustness for laboratory settings.

Figure 2: Workflow for Amplification-based CRISPR Detection. The process involves sample preparation, target amplification, CRISPR detection, and result interpretation.

Detailed Protocol: Two-Step RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a Assay

This protocol details the detection of a specific DNA pathogen (e.g., Mycoplasma) using Cas12a, which is known for its high sensitivity and DNA targeting efficiency [1].

Stage 1: Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA)

Objective: To rapidly amplify the target pathogen DNA sequence at a constant temperature (37-42°C).

Materials:

- Template DNA: Extracted from the clinical sample.

- RPA Primers: Specifically designed to flank a ~200-300 bp region of the target gene.

- Commercial RPA Kit: Contains rehydratable reaction pellets (including recombinase, polymerase, and nucleotides).

- Magnesium Acetate (MgOAc): Serves as the reaction starter.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- Resuspend the RPA pellet in 29.5 µL of nuclease-free water.

- Add 2.4 µL of forward primer (10 µM) and 2.4 µL of reverse primer (10 µM).

- Add 5 µL of the extracted template DNA.

- Mix the components thoroughly by pipetting.

- Amplification:

- Incubate the reaction tube at 39°C for 15-20 minutes in a dry bath or heat block.

- After incubation, the amplified product can be used directly in the CRISPR detection step or stored at -20°C.

Stage 2: CRISPR/Cas12a Detection

Objective: To specifically detect the RPA-amplified target and generate a fluorescent signal via Cas12a's trans-cleavage activity.

Materials:

- Cas12a Enzyme: Purified Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cas12a (LbCas12a).

- crRNA: Designed to be complementary to a specific sequence within the RPA-amplified product. The target region must be adjacent to a TTTV PAM sequence [1].

- Fluorescent Reporter: A single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligonucleotide labeled with a 5' fluorophore (e.g., FAM) and a 3' quencher (e.g., BHQ-1).

- Nuclease-Free Buffer: Typically containing HEPES, NaCl, and DTT.

Procedure:

- CRISPR Reaction Mix:

- Prepare a 20 µL reaction mix containing:

- 1 µL of Cas12a enzyme (1 µM)

- 1.5 µL of crRNA (2 µM)

- 1 µL of fluorescent reporter (5 µM)

- 5 µL of the RPA amplification product

- 11.5 µL of nuclease-free buffer

- Mix gently and centrifuge briefly.

- Prepare a 20 µL reaction mix containing:

- Incubation and Signal Detection:

- Transfer the reaction mix to a real-time PCR instrument or a fluorescent plate reader.

- Incubate at 37°C and measure the fluorescence (FAM channel) every 30 seconds for 10-15 minutes.

- A rapid increase in fluorescence over the background level indicates a positive detection, as the target-activated Cas12a cleaves the reporter, separating the fluorophore from the quencher.

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Positive Result: A significant and exponential increase in fluorescence signal within the first 5-10 minutes of the reaction. Negative Result: Fluorescence remains at baseline levels throughout the incubation period. Validation: Include a positive control (synthetic target DNA) and a negative control (no template DNA) in each experiment to ensure assay validity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of CRISPR diagnostics requires a set of core reagents. The following table lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-based Detection

| Research Reagent | Function & Description | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease | The core enzyme that provides programmable cleavage activity. | e.g., Purified Cas12a, Cas13a. Requires aliquoting and storage at -80°C to maintain activity [1] [3]. |

| crRNA / gRNA | Guide RNA that confers specificity by binding to the target nucleic acid. | Chemically synthesized or in vitro transcribed. Must be designed with high specificity and minimal off-target potential [2]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter | ssDNA/ssRNA probe that emits signal upon Cas-mediated cleavage. | e.g., ssDNA with FAM/BHQ-1 labels for Cas12; ssRNA with FAM/BHQ-1 for Cas13. Stability is critical for low background noise [3]. |

| Isothermal Amplification Kit | Enables rapid nucleic acid amplification at constant temperature for high sensitivity. | Commercial RPA or LAMP kits. Essential for amplification-based CRISPR detection to pre-amplify the target [1] [4]. |

| Lateral Flow Strip | Provides a simple, equipment-free visual readout. | Often uses biotin- and FAM-labeled reporters. Result appears as a test line within minutes [1] [2]. |

| Nuclease-Free Buffer | Provides the optimal ionic and pH environment for Cas enzyme activity. | Typically contains HEPES, salts (NaCl, KCl), DTT, and Mg²⁺. Critical for maintaining reaction efficiency and stability [3]. |

Performance Comparison and Optimization

Understanding the performance metrics of different CRISPR systems is vital for selecting the appropriate diagnostic platform. The following table summarizes key performance data from the literature.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of CRISPR Detection Methods

| Detection Method | Cas Protein | Target Pathogen | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Time-to-Result | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPA-CRISPR | Cas12a | Mpox Virus DNA | 1 copy/µL | < 30 minutes | [1] |

| LAMP-CRISPR | Cas12a | Bacterial Pathogens | Not specified | "Rapid" (e.g., <1 hour) | [1] |

| Amplification-Free | Cas13a | SARS-CoV-2 RNA | 470 aM | ~30 minutes | [1] |

| SHERLOCK | Cas13 | Various RNA Viruses | aM level | ~1 hour | [2] [4] |

| DETECTR | Cas12a | Various DNA Targets | aM level | ~30-60 minutes | [2] [4] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization:

- Low Signal: Optimize the crRNA-to-Cas protein ratio and the concentration of the reporter molecule. Ensure the RPA amplification step is efficient.

- High Background: Check for nuclease contamination in reagents. Titrate the Cas enzyme and reporter to the lowest concentration that gives a strong positive signal. Ensure proper primer and crRNA specificity to avoid non-target amplification.

- Inconsistent Results: Include robust positive and negative controls. Ensure consistent reaction temperatures and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of enzymes and reporters.

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) system functions as an adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea, protecting them from viral and other foreign genetic material invasions [5] [6]. This system incorporates fragments of foreign DNA (spacers) into CRISPR cassettes within the host genome, creating a molecular memory of past infections [5]. Upon re-exposure, these spacers are transcribed into guide RNAs that direct Cas proteins to recognize and cleave complementary invading nucleic acids, thus providing a sequence-specific defense mechanism [5] [7].

CRISPR-Cas systems are broadly classified into two main classes based on their effector module architecture [5] [7]. Class 1 systems (types I, III, and IV) utilize multi-subunit protein complexes for target recognition and cleavage [7]. In contrast, Class 2 systems (types II, V, and VI) employ single, large effector proteins, making them more suitable for biotechnological applications due to their simplicity [6]. Type II systems feature Cas9, type V systems include Cas12 and its variants (e.g., Cas12a, Cas12f), and type VI systems are characterized by Cas13 [5] [6]. The discovery and engineering of these Class 2 effectors have revolutionized genome engineering and molecular diagnostics, providing researchers with a versatile toolkit for precise nucleic acid manipulation and detection [7] [6].

Comparative Characteristics of Cas Proteins

The Cas proteins most relevant for biosensor applications—Cas9, Cas12, Cas13, and Cas14—possess distinct molecular characteristics that determine their specific applications in pathogen detection and genome engineering.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Cas Proteins in Pathogen Detection

| Characteristic | Cas9 | Cas12a | Cas13 | Cas14 (Cas12f) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | dsDNA/RNA [1] | dsDNA/RNA [1] | ssRNA [1] | dsDNA/ssRNA [1] |

| Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) | NGG [1] [8] | TTTV, etc. [1] | None [1] | None [1] |

| Trans-cleavage Activity | Non-specific ssDNA [1] | Non-specific ssDNA [1] [2] | Non-specific ssRNA [1] [2] | Non-specific ssDNA [1] |

| Sensitivity | Medium [1] | High [1] | High [1] | High [1] |

| Specificity | High [1] | Medium [1] | Medium [1] | Very high [1] |

| Key Applications | Laboratory research, gene editing [1] [8] | DNA pathogen detection [1] [9] | RNA pathogen detection [1] [2] | SNP detection, short ssDNA targets [1] |

Table 2: Classification and Functional Properties of CRISPR-Cas Systems

| Class | Type | Signature Protein | Target | Cleavage Mechanism | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | I | Cas3 [5] | ssDNA [5] | Multi-protein complex [7] | Requires multiple Cas proteins [5] |

| III | Cas10 [5] | ssDNA, RNA [5] | Multi-protein complex [7] | Cleaves both DNA and RNA [5] | |

| IV | Csf1 [5] | - | - | Function not fully characterized [5] | |

| Class 2 | II | Cas9 [5] | dsDNA [5] | Single protein, blunt ends [8] | Requires tracrRNA, NGG PAM [8] |

| V | Cas12 [5] | ssDNA, dsDNA [5] | Single protein, staggered ends [2] | T-rich PAM, self-processing RNase [2] | |

| VI | Cas13 [5] | ssRNA [5] | Single protein [2] | No PAM requirement, collateral RNase activity [2] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Cas Proteins

Cas9: The Pioneering DNA Targeting Enzyme

Cas9 was the first Cas protein extensively utilized for genome engineering and forms the foundation of CRISPR technology [8]. The Cas9 mechanism requires two RNA components: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which contains the target-complementary spacer sequence, and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which facilitates crRNA maturation and Cas9 binding [8] [6]. In practice, these are often combined into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for simplified applications [6].

Cas9 recognizes a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence (typically 5'-NGG-3' for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) adjacent to the target DNA [8]. Upon PAM recognition, Cas9 unwinds the DNA duplex, allowing the sgRNA spacer to form an R-loop structure through complementary base pairing with the target strand [8] [6]. The nuclease domains of Cas9—HNH and RuvC—cleave the target and non-target DNA strands, respectively, generating a double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [8] [6].

Cas12: DNA-Activated Non-Specific Nucleases

Cas12 proteins (including Cas12a/Cpf1, Cas12b, and Cas12f/Cas14) represent a distinct family of Type V CRISPR effectors with unique properties [2]. Unlike Cas9, Cas12 proteins recognize T-rich PAM sequences (e.g., TTTV for Cas12a) and create staggered double-strand breaks with 5' overhangs rather than blunt ends [2].

A critical feature of Cas12 proteins is their collateral trans-cleavage activity [2]. Upon recognizing and cleaving its target DNA (cis-cleavage), Cas12 undergoes a conformational change that activates its non-specific single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) nuclease activity [2]. This activated state enables Cas12 to indiscriminately cleave any nearby ssDNA molecules, making it exceptionally valuable for diagnostic applications [9] [2]. This property forms the basis for detection platforms like DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter (DETECTR) [2].

Cas13: RNA-Targeting with Collateral Activity

Cas13 is a Type VI CRISPR effector that uniquely targets RNA rather than DNA [2]. After binding to a target RNA sequence through its crRNA guide, Cas13 exhibits collateral RNase activity, non-specifically cleaving surrounding RNA molecules [2] [10]. This activated trans-cleavage capability enables highly sensitive detection of RNA targets and forms the foundation of the Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter UnLOCKing (SHERLOCK) platform [2].

Recent research has revealed that Cas13a can also be directly activated by DNA targets under certain conditions, particularly when using crRNAs with spacer lengths of at least 20-23 nucleotides [10]. This non-canonical activation pathway enhances Cas13's versatility for diagnostic applications and increases its sensitivity for detecting single-base mismatches in DNA targets [10].

Cas14: Compact RNA-Guided DNA Targeting

Cas14 (reclassified as Cas12f) is an exceptionally compact Type V effector approximately half the size of Cas9 [1]. Despite its small size, Cas12f exhibits similar trans-cleavage activity to other Cas12 family members upon target recognition [1]. Uniquely, Cas12f does not require a specific PAM sequence for activity, significantly expanding its targeting range [1]. This protein demonstrates high specificity for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and short ssDNA targets, making it particularly valuable for precision diagnostics and genotyping applications [1].

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR Biosensors

Protocol: Cas12a-Based Detection of DNA Pathogens (DETECTR)

Principle: This protocol utilizes Cas12a's collateral trans-cleavage activity for sensitive detection of DNA targets from bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella or E. coli [9] [2].

Materials:

- Purified LbCas12a or AsCas12a protein

- Custom-designed crRNA targeting pathogen-specific DNA sequence

- Fluorescent ssDNA reporter (e.g., FAM-TTATT-BHQ1)

- Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) reagents

- Fluorescence detector or lateral flow strips

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Extract nucleic acids from food or clinical samples using standard extraction kits. For complex matrices, additional purification may be necessary to remove inhibitors [9].

- Target Amplification (Optional but Recommended):

- CRISPR Detection:

- Prepare Cas12a detection mixture containing:

- 50 nM Cas12a protein

- 50 nM crRNA

- 500 nM ssDNA reporter

- 1× Cas12a reaction buffer

- Add 2 μL of RPA product or extracted nucleic acid to the detection mixture.

- Incubate at 37°C for 10-30 minutes.

- Prepare Cas12a detection mixture containing:

- Signal Detection:

- Fluorescence Readout: Monitor real-time fluorescence using a plate reader or portable fluorometer.

- Lateral Flow Readout: Apply reaction to lateral flow strip with appropriate capture lines for visual detection [1].

Validation: Include positive and negative controls in each run. The limit of detection for optimized Cas12a assays can reach 1-10 copies/μL of target DNA [9].

Protocol: Cas13-Based SHERLOCK for RNA Viruses

Principle: The SHERLOCK platform leverages Cas13's collateral RNase activity activated by viral RNA detection, ideal for RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 or Influenza A [2] [10].

Materials:

- LbuCas13a or LwaCas13a protein

- Target-specific crRNA

- Fluorescent RNA reporter (e.g., FAM-rUrUrUrUrUrUrUrUrU-BHQ1)

- RPA or RT-RPA reagents

- T7 transcription reagents (if including transcription amplification step)

Procedure:

- RNA Extraction: Purify RNA from patient samples using appropriate RNA extraction kits.

- Reverse Transcription & Amplification:

- Perform RT-RPA using virus-specific primers.

- Alternatively, use RT-RPA followed by T7 transcription for additional signal amplification [2].

- Cas13 Detection:

- Prepare Cas13 reaction mixture containing:

- 50 nM Cas13 protein

- 50 nM crRNA

- 500 nM RNA reporter

- 1× Cas13 reaction buffer

- Add 2 μL of amplified product to the detection mixture.

- Incubate at 37°C for 10-30 minutes.

- Prepare Cas13 reaction mixture containing:

- Result Interpretation:

- Quantitative fluorescence measurement or

- Lateral flow strip readout for point-of-care applications

Optimization Notes: Cas13 can be directly activated by DNA targets with crRNAs of sufficient length (≥23 nt), enabling simplified detection workflows without transcription steps [10].

Protocol: Amplification-Free TCC Detection with CasΦ

Principle: The Target-amplification-free Collateral-cleavage-enhancing CRISPR-CasΦ (TCC) method achieves ultra-sensitive detection without pre-amplification through signal amplification with a dual-stem-loop DNA amplifier [11].

Materials:

- CasΦ (Cas12j) protein

- Two gRNAs (gRNA1 for target recognition, gRNA2 for amplifier recognition)

- TCC amplifier (specially designed dual stem-loop DNA structure)

- Fluorescent ssDNA reporter

Procedure:

- Pathogen Lysis: Lyse bacterial pathogens from clinical samples (e.g., serum) to release genomic DNA.

- One-Pot TCC Reaction:

- Prepare master mix containing:

- 50 nM CasΦ protein

- 50 nM gRNA1 and gRNA2

- 100 nM TCC amplifier

- 500 nM fluorescent ssDNA reporter

- Reaction buffer

- Add sample DNA directly to the reaction mix.

- Incubate at 37°C for 40 minutes.

- Prepare master mix containing:

- Fluorescence Measurement:

- Monitor fluorescence in real-time or measure endpoint fluorescence.

Performance: The TCC method demonstrates a record-low detection limit of 0.11 copies/μL and can detect pathogenic bacteria as low as 1.2 CFU/mL in serum within 40 minutes [11].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Biosensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Supplier/Production Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Proteins | SpyCas9, LbCas12a, LbuCas13a, Cas12f, CasΦ | Effector nucleases that recognize and cleave target nucleic acids | Commercial suppliers (NEB [12]) or recombinant expression |

| Guide RNAs | crRNA, tracrRNA, sgRNA | Sequence-specific guidance of Cas proteins to targets | Chemical synthesis or in vitro transcription |

| Reporter Molecules | FAM-TTATT-BHQ1 (ssDNA), FAM-rU₈-BHQ1 (RNA) | Trans-cleavage substrates that generate detectable signals upon cleavage | Commercial oligonucleotide synthesis |

| Amplification Reagents | RPA kits, LAMP kits | Pre-amplification of target nucleic acids to enhance sensitivity | Commercial detection kits |

| Signal Detection Platforms | Lateral flow strips, portable fluorometers | Readout systems for visual or quantitative result interpretation | Commercial diagnostic companies |

Advanced Applications in Pathogen Detection

Multiplexed Pathogen Detection Systems

Advanced CRISPR biosensing platforms now enable simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens in a single reaction through multiplexing strategies [1] [2]. By combining different Cas proteins with specific guide RNAs, researchers can create comprehensive diagnostic panels for pathogen identification. For example, a CRISPR-drCas12f1/Cas13a system has been developed for dual-target detection, allowing reliable identification of both Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 and the human reference gene POP7 in clinical samples with 100% sensitivity and specificity [10].

The key to successful multiplexing lies in selecting Cas proteins with orthogonal activities and designing specific guide RNAs without cross-reactivity. Cas12 variants target DNA sequences while Cas13 targets RNA, enabling parallel detection pathways in the same reaction tube [10]. Engineering Cas proteins with reduced non-specific activities, such as the RNase-deactivated Cas12f1 variant (drCas12f1), further enhances multiplexing accuracy by preventing interference between detection channels [10].

Point-of-Care Diagnostic Platforms

CRISPR-based biosensors have been successfully integrated into portable, point-of-care devices suitable for resource-limited settings [9] [2]. These platforms typically combine:

- Lyophilized CRISPR reagents for room-temperature stability

- Simple sample preparation methods requiring minimal equipment

- Lateral flow readouts for visual result interpretation without instrumentation

- Microfluidic chambers for automated fluid handling [2]

Commercial development of these systems focuses on creating "sample-to-answer" platforms that integrate nucleic acid extraction, amplification, and CRISPR detection in a single, automated device [2]. The portability and minimal equipment requirements make these systems ideal for rapid outbreak response, food safety monitoring at production sites, and clinical testing in primary care settings [9].

Enhancement Strategies for Sensitivity and Specificity

Recent advances in CRISPR diagnostics have focused on enhancing sensitivity through engineered Cas variants and signal amplification strategies:

Cas Protein Engineering: High-fidelity Cas variants (e.g., HypaCas9, eSpCas9) with reduced off-target effects maintain on-target activity while minimizing false positives [8]. PAM-flexible Cas proteins (e.g., xCas9, SpRY) expand the targetable genomic space [8].

Signal Amplification Systems: The TCC system using CasΦ achieves attomolar sensitivity without target amplification through a dual-stem-loop DNA amplifier that creates a catalytic cascade upon target recognition [11]. This system enhances the collateral cleavage activity through exponential accumulation of activated CasΦ over time.

Pre-concentration Methods: Microfluidic and digital droplet platforms concentrate nucleic acid targets before CRISPR detection, improving sensitivity for low-abundance targets in complex samples like blood [11].

The Cas protein toolbox—encompassing Cas9, Cas12, Cas13, and Cas14—provides an expanding repertoire of molecular tools for precision pathogen detection. Each Cas protein offers unique advantages: Cas9 for precise DNA targeting, Cas12 for DNA-activated trans-cleavage, Cas13 for RNA detection, and the compact Cas14 for PAM-flexible applications. The modular nature of these systems enables researchers to develop tailored biosensing platforms for diverse diagnostic scenarios.

Future developments in CRISPR biosensing will likely focus on multiplexing capabilities, point-of-care applicability, and integration with sequencing technologies [2] [6]. As CRISPR diagnostics evolve from laboratory tools to clinical applications, addressing challenges related to sensitivity in complex matrices, scalability, and regulatory approval will be essential [9] [2]. The expanding CRISPR toolbox continues to push the boundaries of molecular diagnostics, promising transformative impacts on public health responses to infectious disease threats.

The diagnostic application of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology represents a paradigm shift in molecular detection, leveraging a naturally occurring bacterial immune mechanism for precise pathogen identification. At the heart of this system lies the CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which functions as a guide molecule to direct CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins to specific nucleic acid sequences through complementary base pairing [2]. Upon successful recognition and binding to its target, certain Cas proteins undergo a conformational change that activates their trans-cleavage activity—a nonspecific collateral cleavage of surrounding single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or RNA (ssRNA) molecules [13] [14]. This core mechanism transforms a specific molecular recognition event into an amplified, detectable signal, forming the foundation for a new generation of highly sensitive and specific diagnostic platforms.

The programmable nature of crRNA allows researchers to design detection assays for virtually any pathogen by simply modifying the guide sequence to target conserved genomic regions, such as bacterial 16S rRNA genes or viral pathogenicity islands [2]. When combined with various signal transduction methods—including fluorescence, electrochemical detection, and lateral flow assays—this core principle enables the development of rapid, accurate, and field-deployable diagnostic tools that meet the World Health Organization's criteria for ideal point-of-care testing [1] [2].

Molecular Mechanisms of crRNA-Guided Targeting and Trans-Cleavage

crRNA-Guided Target Recognition

The CRISPR-Cas diagnostic process initiates with the crRNA-guided target recognition phase, where the designed crRNA directs the Cas effector complex to seek out and bind with its complementary nucleic acid target. The crRNA contains a spacer sequence that is computationally designed to be perfectly complementary to a specific region of the pathogen's genome, enabling exquisite specificity [2]. For DNA-targeting Cas proteins like Cas12a, recognition also requires the presence of a short protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target region, which is typically 5'-TTTN for Cas12a systems [13]. This PAM requirement adds an additional layer of specificity to the recognition process.

The binding event between the crRNA-Cas complex and the target nucleic acid triggers significant conformational changes in the Cas protein structure, particularly in the RuvC domain responsible for nuclease activity [13] [14]. This allosteric activation transitions the Cas protein from a silent state to an enzymatically active configuration, primed for both specific cis-cleavage of the target molecule and nonspecific trans-cleavage of reporter molecules [2]. The structural rearrangement opens access to the catalytic core, allowing the Cas protein to engage in collateral cleavage activity that amplifies the detection signal.

Trans-Cleavage Activation and Signal Amplification

Following target recognition and Cas protein activation, the trans-cleavage mechanism initiates, enabling the system to function as a powerful signal amplifier. Unlike the precise cis-cleavage activity that cuts only the target nucleic acid, trans-cleavage represents a nonspecific enzymatic activity that indiscriminately degrades surrounding single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules [13] [14]. This collateral cleavage activity continues catalytically as long as the Cas protein remains activated, with a single target recognition event leading to the cleavage of thousands of reporter molecules [15].

The trans-cleavage activity exhibits distinct biochemical characteristics across different Cas effectors. Cas12a demonstrates robust collateral cleavage against ssDNA reporters, while Cas13a targets ssRNA molecules [1] [2]. This fundamental difference allows researchers to select the appropriate Cas protein based on the nature of the target pathogen and desired detection modality. The catalytic nature of this process enables exceptional sensitivity, with some platforms achieving detection limits in the attomolar range without any pre-amplification steps [1] [14].

Table 1: Key Cas Effectors and Their Diagnostic Properties

| Cas Protein | Nucleic Acid Target | Trans-Cleavage Substrate | PAM Requirement | Key Diagnostic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas12a | DNA | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) | 5'-TTTN | DNA virus detection, bacterial pathogen identification [1] [2] |

| Cas13a | RNA | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) | None | RNA virus detection (e.g., SARS-CoV-2, HIV) [1] [2] |

| Cas14 | ssDNA | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) | None | Single-nucleotide polymorphism detection, short ssDNA targets [1] |

| Cas9 | DNA | Limited/None | 5'-NGG | Primarily used for gene editing, limited diagnostic application [1] [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: crRNA Design and Preparation

Principle: Effective crRNA design is paramount for successful CRISPR-based diagnostics, ensuring high specificity and sensitivity toward the target pathogen [14] [2].

Materials:

- Target pathogen genomic sequence

- crRNA design software (e.g., CHOPCHOP, CRISPRscan)

- DNA/RNA synthesizer or commercial synthesis service

- Nuclease-free water

- Storage buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5)

Procedure:

- Target Identification: Identify conserved regions within the pathogen genome suitable for targeting. For bacterial detection, the 16S rRNA gene often provides ideal target sequences [2].

- crRNA Design: Design a 20-24 nucleotide spacer sequence complementary to the target region. For Cas12a systems, ensure the target site is adjacent to a 5'-TTTN PAM sequence [13] [14].

- Sequence Validation: Verify specificity using BLAST or similar tools to minimize off-target binding.

- crRNA Synthesis: Synthesize the crRNA using in vitro transcription or commercial synthesis services. For enhanced performance, consider engineered crRNA with 3'-end ssDNA extensions (e.g., 7-mer DNA) to boost trans-cleavage activity [14].

- Quality Control: Purify synthesized crRNA using PAGE or HPLC and quantify using spectrophotometry.

- Storage: Aliquot and store at -20°C in nuclease-free storage buffer to prevent degradation.

Protocol 2: Electrochemical CRISPR (E-CRISPR) Detection

Principle: This protocol leverages the trans-cleavage activity of Cas12a to cleave ssDNA reporters labeled with electrochemical tags, generating measurable electrical signals when the target pathogen is present [13] [17].

Materials:

- LbCas12a or AsCas12a nuclease

- Designed crRNA specific to target pathogen

- Thiolated ssDNA reporter with methylene blue tag

- Disposable gold electrode three-electrode system

- Reaction buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 6.8, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT)

- Square wave voltammetry (SWV) instrument

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Clean gold working electrode with piranha solution and assemble the three-electrode system [13].

- Reporter Immobilization: Incubate the electrode with 100 nM thiolated ssDNA reporter labeled with methylene blue for 1 hour at room temperature to form a self-assembled monolayer [13].

- CRISPR Complex Formation: Pre-incubate 50 nM Cas12a with 50 nM crRNA in reaction buffer for 20 minutes at 37°C to form the ribonucleoprotein complex [13].

- Target Detection: Add the target nucleic acid (10-1000 pM) to the CRISPR complex and incubate for 5-60 minutes at 37°C to activate trans-cleavage [13].

- Electrochemical Measurement: Apply the reaction mixture to the reporter-modified electrode and measure the methylene blue signal using square wave voltammetry [13] [17].

- Signal Interpretation: A decrease in current indicates target recognition and subsequent cleavage of the ssDNA reporter. The signal reduction correlates with target concentration [13].

Optimization Notes:

- LbCas12a generally demonstrates more robust trans-cleavage activity than AsCas12a [13].

- Magnesium concentration significantly impacts trans-cleavage efficiency; optimize between 5-15 mM [13].

- Reporter surface density affects accessibility; moderate densities (100-200 nM) typically yield optimal results [13].

Protocol 3: Fluorescence-Based Detection with Engineered crRNA

Principle: This protocol utilizes crRNA engineered with DNA extensions to enhance trans-cleavage activity, enabling highly sensitive fluorescence-based detection of nucleic acid targets without target amplification [14].

Materials:

- LbCas12a nuclease

- Engineered crRNA with 3'-end 7-mer DNA extension

- FAM-quencher (BHQ) ssDNA reporter (5'-TTATT-3')

- Reaction buffer (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 5-15 mM MgCl₂, pH 6.8)

- Real-time PCR instrument or fluorescence plate reader

Procedure:

- crRNA Engineering: Synthesize crRNA with a 7-mer DNA extension on the 3'-end. This modification enhances trans-cleavage activity approximately 3.5-fold compared to wild-type crRNA [14].

- Complex Formation: Pre-incubate 50 nM LbCas12a with 50 nM engineered crRNA in reaction buffer for 20 minutes at 25°C [14].

- Reaction Assembly: Add 500 nM FAM-quencher ssDNA reporter to the CRISPR complex [14].

- Target Addition: Introduce the target nucleic acid (1 fM-1 nM) to initiate the trans-cleavage reaction.

- Fluorescence Monitoring: Immediately monitor fluorescence increase in real-time using a plate reader (excitation: 485 nm, emission: 535 nm) for 30-60 minutes [14].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the rate of fluorescence increase, which correlates with target concentration. The engineered system can achieve femtomolar sensitivity without target pre-amplification [14].

Optimization Notes:

- TA-rich reporters generally yield higher fluorescence signals than GC-rich reporters [14].

- The 3'-DNA extension position is critical; 5'-extensions show minimal enhancement effect [14].

- Kinetic studies show a 3.2-fold higher Kcat/Km ratio for engineered crRNA compared to wild-type [14].

Enhancement Strategies and Technical Optimization

crRNA Engineering for Improved Performance

Strategic modification of crRNA structure represents a powerful approach for enhancing the sensitivity and specificity of CRISPR-based diagnostics. Research demonstrates that extending the 3'-end of crRNA with short DNA oligonucleotides can significantly augment trans-cleavage activity. A 7-mer DNA extension on the 3'-end of crRNA produces approximately 3.5-fold higher fluorescence signal compared to wild-type crRNA, enabling detection limits in the femtomolar range without target pre-amplification [14]. This enhancement appears to result from conformational changes in the RuvC domain of Cas12a that increase accessibility to ssDNA reporters.

The position and composition of crRNA extensions critically determine their efficacy. While 3'-end DNA extensions markedly boost trans-cleavage activity, 5'-end extensions show minimal enhancement effect [14]. Similarly, phosphorothioate ssDNA extensions inhibit trans-cleavage activity, particularly at longer lengths (≥13 nucleotides) [14]. These structure-activity relationships highlight the importance of rational crRNA design for optimal diagnostic performance.

Reaction Condition Optimization

The trans-cleavage activity of Cas12a is strongly influenced by reaction conditions, with divalent cations playing a particularly crucial role. The RuvC domain of Cas12a cleaves ssDNA through a two-metal ion mechanism that requires Mg²⁺ ions to induce proper conformational coordination between the enzyme and its substrate [13]. Systematic optimization of Mg²⁺ concentration reveals that trans-cleavage activity increases with Mg²⁺ concentration up to 15 mM, with no activity observed in the absence of Mg²⁺ ions [13].

The surface density of ssDNA reporters significantly impacts cleavage efficiency in immobilized systems such as electrochemical biosensors. High surface densities can decrease signal change by reducing Cas12a accessibility to the ssDNA reporter, while moderate densities facilitate optimal cleavage activity [13]. The trans-cleavage period also requires optimization, as this activity persists for extended durations (up to 3 hours) after target recognition and cis-cleavage, which typically completes within 30 minutes [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Optimization Parameters for CRISPR-Cas12a Diagnostics

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Effect on Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas12a Analog | LbCas12a | More robust and stable trans-cleavage vs. AsCas12a | [13] |

| Mg²⁺ Concentration | 15 mM | Essential for RuvC domain function; maximal activity at 15 mM | [13] |

| crRNA Engineering | 3'-end 7-mer DNA extension | 3.5-fold increase in trans-cleavage activity | [14] |

| Reporter Composition | TA-rich ssDNA with FAM | Higher signal vs. GC-rich or alternative fluorophores | [14] |

| Detection Limit (with engineering) | Femtomolar (10⁻¹⁵ M) | Without target pre-amplification | [14] |

| Detection Limit (standard) | Picomolar (10⁻¹² M) | Without target pre-amplification | [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Based Diagnostics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Effectors | LbCas12a, AsCas12a, Cas13a | Core enzyme for target recognition and trans-cleavage; LbCas12a preferred for robust activity [13] [14] |

| crRNA Solutions | Wild-type crRNA, Engineered crRNA (3'-DNA7) | Guides target recognition; engineered versions enhance sensitivity [14] [2] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | FAM-TTATT-BHQ1, HEX-TTATT-BHQ2 | Signal generation via fluorophore-quencher separation upon trans-cleavage [14] |

| Electrochemical Reporters | Thiolated ssDNA with methylene blue | Enable electrochemical detection on electrode surfaces [13] [17] |

| Buffer Components | MgCl₂ (5-15 mM), HEPES (pH 6.8) | Optimize enzymatic activity; Mg²⁺ essential for RuvC domain function [13] |

| Signal Amplification Systems | RPA, LAMP kits | Pre-amplification for enhanced sensitivity; compatible with CRISPR detection [1] [17] |

Implementation Workflows and Diagnostic Applications

The core principle of crRNA-guided targeting and trans-cleavage activity has been successfully implemented in various diagnostic platforms with diverse applications in pathogen detection. The DETECTR (DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter) system leverages Cas12a for DNA virus detection, while the SHERLOCK (Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter unLOCKing) platform utilizes Cas13a for RNA pathogen identification [2]. These systems have demonstrated clinical utility in detecting human papillomavirus (HPV-16), parvovirus B19, SARS-CoV-2, and various bacterial pathogens with sensitivity comparable to PCR-based methods but with significantly faster turnaround times [13] [2].

Recent advances have focused on integrating CRISPR diagnostics with portable readout systems such as lateral flow assays and microfluidic devices, enabling point-of-care testing in resource-limited settings [1] [2]. The development of lyophilized reagent formulations further enhances field-deployment capability by eliminating cold-chain requirements [2]. These innovations position CRISPR-based diagnostics as a transformative technology for rapid outbreak response and routine clinical testing.

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Successful implementation of CRISPR diagnostics requires careful attention to potential technical challenges. Nonspecific activation of trans-cleavage can occur in some systems, leading to false-positive signals. This can be mitigated through optimized crRNA design, including the use of engineered crRNA with 7-mer 3'-DNA extensions that enhance both sensitivity and specificity [14]. Inhibitor interference from complex clinical samples (e.g., blood, sputum) may reduce detection sensitivity; incorporating sample purification steps or using inhibitor-resistant Cas variants can address this limitation [2].

The dynamic range of CRISPR diagnostics may require optimization for specific applications. For high-abundance targets, dilution of the CRISPR reaction mixture or reduction of incubation time may prevent signal saturation. Conversely, for low-abundance targets, incorporating isothermal amplification methods like RPA or LAMP prior to CRISPR detection can enhance sensitivity to attomolar levels [1] [17]. The choice of Cas effector should align with the target pathogen—Cas12a for DNA targets and Cas13a for RNA targets—to ensure optimal performance [1] [2].

Environmental factors such as temperature and humidity can significantly impact CRISPR enzyme activity, with field studies reporting up to 63% performance reduction in Cas14-based assays under high humidity conditions [2]. Implementing proper environmental controls or using stabilized reagent formulations can enhance reliability across diverse testing environments.

Within molecular diagnostics, the detection of pathogenic nucleic acids primarily follows two contrasting paradigms: amplification-based and amplification-free methods. Amplification-based techniques rely on enzymatic pre-amplification of the target sequence to boost copy numbers before detection, offering high sensitivity but introducing operational complexity and contamination risks. In contrast, amplification-free methods detect the target nucleic acid directly, leveraging advanced sensing technologies to achieve rapid results and minimize false positives, though often posing significant sensitivity challenges [1] [18]. The advent of CRISPR-Cas biosensors has profoundly impacted both fields, providing a versatile and programmable platform for pathogen detection. This Application Note delineates these two fundamental diagnostic approaches, providing a comparative analysis, detailed protocols, and a resource toolkit tailored for research scientists and drug development professionals engaged in CRISPR-based pathogen detection.

Comparative Analysis of Diagnostic Paradigms

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the amplification-based and amplification-free CRISPR diagnostic paradigms.

Table 1: Comparison of Amplification-Based and Amplification-Free CRISPR Diagnostics

| Feature | Amplification-Based CRISPR Diagnostics | Amplification-Free CRISPR Diagnostics |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Couples CRISPR detection with pre-amplification (e.g., RPA, LAMP) [1]. | Direct detection of target nucleic acids by CRISPR, often enhanced by advanced sensors [1] [18]. |

| Key Strengths | High sensitivity (e.g., single-copy detection) [1]. Broadly established protocols. | Avoids amplification-related contamination and false positives. Faster time-to-result. Simpler, more streamlined workflow [18]. |

| Key Limitations | Risk of nonspecific amplification and cross-contamination. Multi-step process increases complexity and time [1]. | Sensitivity can be a challenge without amplification. Often relies on sophisticated transducers for ultra-sensitive detection [19] [18]. |

| Typical LOD | Can achieve sensitivities as low as 1 copy/μL [1]. | Can reach attomolar (aM) levels with optimized systems (e.g., 214 aM for RNA) [19]. |

| Example Applications | Detection of Mpox virus DNA with RPA-Cas12a [1]. Detection of bacterial pathogens with LAMP-Cas12a [1]. | Direct detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA with Cas13a (470 aM) [1]. Direct detection of miRNAs in clinical samples via CRISPR-GFET [19]. |

Amplification-Free CRISPR Detection: A Detailed Protocol

The following section provides a detailed protocol for an advanced, amplification-free biosensor that integrates a Type III CRISPR-Cas10 system with a graphene field-effect transistor (GFET), achieving attomolar sensitivity for direct RNA and miRNA detection [19].

Principle and Workflow

This biosensor exploits the target RNA-activated continuous ssDNA cleavage activity of a mutant CRISPR-Cas10 effector complex. The cleavage of a high-charge-density hairpin DNA reporter immobilized on the GFET channel induces a measurable change in electrical conductivity, enabling label-free and amplification-free detection [19].

Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas10-GFET Biosensor

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LdCsm Effector Complex (Mutant) | The core Type III-A CRISPR-Cas10 complex from Lactobacillus delbrueckii. The Csm3D34A mutation prevents target RNA degradation, enabling sustained Cas10 DNase activity [19]. | Purified from E. coli BL21(DE3). Essential for continuous trans-cleavage. |

| Artificial mini-CRISPR Plasmid | Plasmid for expressing specific crRNA targeting the desired RNA/miRNA (e.g., miRNA-155) [19]. | Designed with multiple copies of Ld repeat and spacer sequences via fusion PCR. |

| Hairpin DNA Reporter | A stem-loop structured ssDNA molecule immobilized on the GFET surface. Cleavage by activated Cas10 alters the local charge density, transducing the signal [19]. | The 7nt stem-loop structure is recommended as it significantly enhances signal over linear reporters [20]. |

| Graphene Field-Effect Transistor (GFET) | The transducer. Graphene's high carrier mobility and thin structure enable highly sensitive detection of surface charge changes [19]. | Fabricated using standard microfabrication techniques. |

| Buffer A (Lysis & Resuspension) | 50 mL of buffer for cell resuspension after centrifugation during protein purification [19]. | Exact composition as per established purification protocols. |

| HisTrap Affinity Column | Used for purifying the histidine-tagged LdCsm effector complex from cell lysate [19]. | Standard for protein purification. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Procedure

Preparation of CRISPR-Cas10 Effector Complexes (Timeline: ~3-4 days)

- Plasmid Construction: Clone the artificial mini-CRISPR array targeting your specific RNA/miRNA into the pUCE plasmid using Gibson assembly. The array is generated by fusion PCR using specific primers (e.g., RNA-F/R, miR-155-F/R) [19].

- Protein Expression:

- Co-transform the mini-CRISPR plasmid (pUCE-X), pET30a-Csm2, and the mutant p15AIE-Cas-dCsm3 plasmid into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells [19].

- Inoculate a single colony into 20 mL of LB medium with appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin, kanamycin, chloramphenicol) and grow overnight at 37°C, 220 rpm.

- Dilute 10 mL of the overnight culture into 1 L of TB medium. Grow at 37°C, 220 rpm until OD600 reaches 0.8.

- Induce protein expression by adding 0.3 mM IPTG and incubate at 25°C, 180 rpm for 16 hours [19].

- Protein Purification:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 5 minutes.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in 50 mL of Buffer A.

- Lyse the cells using a French press and clarify the lysate by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Purify the LdCsm complex from the supernatant using a HisTrap affinity column, following standard elution protocols [19].

Biosensor Assembly and Detection (Timeline: ~2-4 hours)

- GFET Functionalization: Immobilize the synthesized hairpin DNA reporters onto the channel surface of the GFET biosensor. Optimize immobilization chemistry (e.g., π-π stacking, linker molecules) for maximum density and stability [19].

- CRISPR Reaction Incubation:

- Prepare the reaction mixture containing the purified mutant LdCsm effector complex and the target RNA sample in an appropriate buffer.

- Incubate the mixture to allow for target binding and activation of the trans-cleavage activity. The activated complex will continuously cleave the free hairpin DNA reporters.

- Signal Measurement and Readout:

- Measure the electrical characteristics (e.g., source-drain current vs. gate voltage) of the GFET in real-time or at the endpoint.

- The cleavage of the highly charged hairpin DNA reporters causes a measurable shift in the transfer characteristics of the GFET, which is quantitatively correlated with the target RNA concentration [19].

Amplification-Based CRISPR Detection: A Representative Protocol

For comparison, below is a core protocol for a typical two-step amplification-based detection method, such as RPA (Recombinase Polymerase Amplification) coupled with CRISPR-Cas12a.

Principle and Workflow

The target pathogen's DNA is first amplified isothermally using RPA, which rapidly multiplies the number of target copies at a constant temperature. The amplified product is then introduced into a CRISPR-Cas12a reaction. Upon recognition of the target amplicon, the activated Cas12a exhibits trans-cleavage activity, degrading a fluorescent or lateral-flow reporter molecule to generate a detectable signal [1].

Key Experimental Steps

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract and purify genomic DNA or RNA from the sample (e.g., clinical swab, plant tissue, food sample). For RNA targets, include a reverse transcription step [20].

- Isothermal Amplification (RPA):

- Prepare the RPA reaction mix according to the manufacturer's protocol, containing primers specific to the target pathogen.

- Add the extracted nucleic acid template.

- Incubate the RPA reaction at a constant temperature (e.g., 37-42°C) for 15-30 minutes to amplify the target [1].

- CRISPR Detection:

- Prepare the CRISPR reaction mix containing Cas12a protein, target-specific crRNA, and a fluorescent (FAM-Quencher) or lateral flow (FAM-Biotin) reporter.

- Manually transfer a portion of the RPA amplicon into the CRISPR reaction mix.

- Incubate the combined reaction at 37°C for 10-30 minutes to allow for signal development [1].

- Signal Visualization: Read the result using a fluorometer for quantitative analysis, a UV flashlight for visual fluorescence, or a lateral flow dipstick for a binary (yes/no) result [1] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-based Pathogen Detection

| Category | Item | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Effectors | Cas12a (LbCas12a, LbCas12a-Ultra) [20], Cas13a, Type III CRISPR-Cas10 [19] | Core nucleases for target recognition and signal generation via trans-cleavage. |

| Guide RNAs | crRNA for Cas12a/Cas10 [19], sgRNA for Cas9 | Provides target specificity; sequence dictates detection target. |

| Reporters | Linear ssDNA (FAM-Q) [1], Stem-loop/Hairpin DNA (e.g., 7nt stem) [19] [20] | Signal-generating molecule; cleavage indicates target presence. Hairpin structures can enhance signal. |

| Amplification Kits | RPA Kit, LAMP Kit [1] | For pre-amplification of nucleic acid targets to boost sensitivity in amplification-based methods. |

| Signal Transducers | Graphene Field-Effect Transistor (GFET) [19], Electrode Chips [21], Lateral Flow Strips [20] | Converts biochemical reaction (cleavage) into a quantifiable readout (electrical, visual). |

| Purification Systems | HisTrap Affinity Column [19], Plant Genomic DNA Kit [22] | For purifying recombinant Cas proteins or extracting nucleic acids from complex samples. |

From Lab to Field: CRISPR Biosensing Platforms and Their Applications

The rapid and accurate detection of pathogenic microorganisms is a cornerstone of effective public health responses to infectious disease outbreaks [1]. While traditional methods like microbial culture and quantitative PCR (qPCR) offer high sensitivity and specificity, they are often time-consuming, require sophisticated laboratory equipment, and are unsuitable for point-of-care testing (POCT) [1] [23]. The advent of CRISPR-Cas technology has ushered in a new era for molecular diagnostics, characterized by high specificity and programmability [1] [24]. However, the intrinsic sensitivity of CRISPR systems alone is often insufficient for clinical applications, typically detecting targets only in the picomolar range [25]. To overcome this limitation, amplification-based CRISPR strategies have been developed, which integrate pre-amplification steps using techniques like Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) and Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) to achieve ultra-sensitive detection of pathogens without compromising speed or simplicity [1] [23]. This Application Note details the principles, protocols, and key reagents for implementing these powerful integrated diagnostic platforms within the broader context of CRISPR biosensor research.

Principle of Amplification-Based CRISPR Detection

Amplification-based CRISPR technology synergistically combines isothermal amplification techniques with the specific recognition and trans-cleavage activity of CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins. Isothermal amplification, such as RPA or LAMP, enables the rapid multiplication of target nucleic acid sequences at a constant temperature, thereby eliminating the need for thermal cyclers and enhancing the platform's suitability for POCT [1] [23]. The amplified products then serve as targets for the CRISPR-Cas system.

Upon recognition of its specific target sequence, guided by a CRISPR RNA (crRNA), certain Cas proteins (e.g., Cas12a, Cas13) exhibit collateral trans-cleavage activity [1]. This results in the non-specific degradation of nearby reporter molecules, which are typically single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or RNA oligonucleotides labeled with a fluorophore and a quencher. The cleavage separates the fluorophore from the quencher, generating a detectable fluorescent signal that reports the presence of the pathogen [1] [24]. This combination results in a diagnostic tool that is not only highly sensitive but also specific, rapid, and amenable to miniaturization and visual readout, for example, via lateral flow assays [1].

Comparative Analysis of Integrated CRISPR Platforms

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of representative RPA/CRISPR and LAMP/CRISPR platforms, highlighting their ultra-sensitive detection capabilities for various pathogens.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RPA/CRISPR and LAMP/CRISPR Platforms

| Platform Name | Integrated Amplification Method | CRISPR System | Target Pathogen/Gene | Detection Limit | Total Assay Time | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| opvCRISPR [23] | RT-LAMP | Cas12a/Cas13a | SARS-CoV-2 | 0.5 copies/μL | 15-20 min | One-pot, spatial segregation of reagents in a single tube. |

| RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a [23] | RT-RPA | Cas12a | SARS-CoV-2 | 1 copy/μL | 15 min | Two-step in a single tube; integrated with a smartphone-based portable device. |

| DETECTR [24] [23] | RPA | Cas12a | HPV | ~aM range | 30-60 min | Early pioneering platform for DNA virus detection and genotyping. |

| SHERLOCK [24] [23] | RPA | Cas13a | Zika virus, Dengue virus | ~aM range | 30-60 min | Early pioneering platform for RNA virus detection. |

| HOLMES [24] [23] | PCR/LAMP | Cas12b | Plasmid pUC18-rs5028 | 10 aM | N/A | Demonstrates extreme sensitivity with different Cas proteins. |

Table 2: Characteristics of Common Cas Proteins Used in Pathogen Detection

| Characteristic | Cas12a | Cas13 |

|---|---|---|

| Target Nucleic Acid | DNA/RNA [1] | RNA [1] |

| Trans-cleavage Substrate | Non-specific ssDNA [1] | Non-specific ssRNA [1] |

| PAM Requirement | TTTV, etc. [1] | None [1] |

| Typical Application | DNA viruses, Bacteria [1] | RNA viruses [1] |

| Reported Sensitivity | High [1] | High [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: One-Tube RPA-Assisted CRISPR-Cas12a/Cas13a Detection

This protocol, adapted from Hu et al., describes a contamination-free method for detecting SARS-CoV-2 using a specialized tube design to separate amplification from detection [23].

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Treat the sample (e.g., 5 μL) with a nucleic acid rapid release agent. This step bypasses complex RNA extraction, crucial for a rapid POCT workflow [23].

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare the RT-RPA master mix according to the manufacturer's instructions (e.g., 29.4 μL buffer A, 1.2 μL each of forward and reverse primer (20 μM), and nuclease-free water). Distribute the mix into the inner tube of a specialized double-container device [23].

- Prepare the CRISPR detection master mix in the outer tube, containing LbaCas12a or LwaCas13a protein, specific crRNA, and the appropriate ssDNA or ssRNA fluorescent reporter (e.g., labeled with FAM and BHQ) in the provided buffer [23].

- Pre-amplification: Place the reaction device in a heating block or portable incubator at 37°C for 10 minutes for the RT-RPA reaction [23].

- Reaction Mixing: After amplification, briefly centrifuge the device to transfer the RT-RPA products from the inner tube to the outer tube through hydrophobic pores, initiating the CRISPR reaction [23].

- CRISPR Detection & Readout: Incubate the device for an additional 5 minutes at 37°C. The fluorescence signal can be visualized under a blue-light illuminator or quantified using a smartphone camera and a custom-designed app for result interpretation [23].

Protocol 2: One-Pot LAMP-CRISPR (opvCRISPR) for Viral RNA

This protocol outlines a one-pot assay where LAMP reagents and CRISPR reagents are physically separated within the same tube via the tube cap, simplifying the workflow and minimizing contamination [23].

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Tube Pre-loading:

- Dispense the LAMP reaction mix (containing primers, DNA polymerase, and dNTPs) to the bottom of a microcentrifuge tube.

- Dispense the CRISPR reaction mix (containing Cas12a protein, crRNA, and reporter) onto the inner wall of the tube's cap. Ensure the two mixes remain separate [23].

- Amplification: Add the extracted nucleic acid sample or lysate directly to the LAMP mix at the tube bottom. Close the cap and incubate the tube at 60–65°C for 20–30 minutes to allow for isothermal amplification [23].

- Reaction Activation: Briefly centrifuge the tube for a few seconds. This action combines the amplified LAMP products from the bottom with the CRISPR reagents from the cap [23].

- Detection: Incubate the combined reaction at 37°C for 5–10 minutes. The presence of the target amplicon will activate the Cas protein's trans-cleavage activity, producing a signal.

- Result Interpretation: Results can be read using a portable fluorescence reader, a lateral flow dipstick (for biotin/FAM-labeled reporters), or by visual inspection under blue light [1] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these protocols relies on a set of core reagents. The table below lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for RPA/LAMP-CRISPR Assay Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Assay | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease | The effector protein that provides specific recognition and non-specific trans-cleavage activity. | LbaCas12a (for DNA), LwaCas13a (for RNA). Select based on target nucleic acid type [1] [23]. |

| crRNA | Guide RNA that confers specificity by binding to the target amplicon and directing the Cas protein. | Designed to be complementary to the target region within the RPA/LAMP amplicon. Critical for specificity [1] [24]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter | ssDNA (for Cas12a) or ssRNA (for Cas13) molecule that is cleaved to generate a detectable signal. | Often an ssDNA oligo labeled with FAM (fluorophore) and BHQ-1 (quencher). Cleavage generates fluorescence [1] [23]. |

| Isothermal Amplification Kit | Enzymes and reagents for rapid, constant-temperature nucleic acid amplification. | Commercial RPA (e.g., AmpFuture kits) or LAMP kits. Includes polymerase, recombinase (for RPA), and primers [23]. |

| Primers | Short DNA oligonucleotides that define the target region for pre-amplification. | RPA requires a pair of primers (~30-35 nt). LAMP requires 4-6 primers recognizing distinct regions of the target for high specificity [23] [25]. |

| Specialized Reaction Vessel | A device that enables one-pot or contamination-free reactions. | Tubes with compartments (e.g., inner/outer tubes, cap-and-body systems) to keep amplification and detection separate until the correct time [23]. |

The integration of RPA and LAMP with CRISPR systems represents a significant advancement in molecular diagnostics, effectively bridging the sensitivity gap between standalone CRISPR assays and traditional PCR. These combined platforms achieve detection limits as low as 0.5 copies/μL with assay times under 20 minutes, making them formidable tools for rapid, ultra-sensitive pathogen detection [23]. The flexibility in readout modalities—from smartphone-based fluorescence detection to simple lateral flow strips—further enhances their utility in diverse settings, from central laboratories to remote field deployments [1] [23].

A key challenge in assay design is preventing the Cas protein from degrading primers and templates during one-pot reactions, which can reduce sensitivity. Strategies like spatial segregation of reagents (as shown in the protocols above) or the use of PAM-independent crRNAs to prevent target cleavage during amplification have been successfully employed to mitigate this issue [23]. Furthermore, the choice between RPA and LAMP depends on the application: RPA operates at a lower temperature (37-42°C) that is compatible with most Cas proteins, while LAMP (60-65°C) can offer higher amplification efficiency but may require a separate detection step at a lower temperature [1] [23].

In conclusion, RPA/CRISPR and LAMP/CRISPR platforms are powerful, versatile, and rapidly evolving. The protocols and guidelines provided here offer researchers a foundation for developing and optimizing these assays, contributing to the expanding toolbox for infectious disease diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and ultimately, improved global public health responses.

The field of molecular diagnostics is undergoing a transformative shift with the advent of amplification-free CRISPR-based detection technologies. Traditional pathogen detection methods often rely on nucleic acid amplification techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), to enhance sensitivity [1]. While effective, these amplification steps introduce complexity, increase the risk of contamination, require specialized equipment, and prolong detection times, making them less suitable for point-of-care testing (POCT) [1] [26]. Amplification-free CRISPR strategies represent a paradigm shift by leveraging the high intrinsic sensitivity and specificity of CRISPR-Cas systems to detect pathogenic nucleic acids directly, without any pre-amplification [27]. This approach significantly reduces operational complexity, decreases the potential for false positives due to contamination, and shortens the time-to-result, thereby paving the way for rapid, field-deployable diagnostics [1] [2]. The core principle enabling this advancement is the trans-cleavage activity of certain Cas proteins—a non-specific "collateral" nuclease activity that is triggered upon recognition of a specific target sequence [1] [2]. This review delves into the cutting-edge amplification-free strategies, including cascade CRISPR systems, digital droplet platforms, and the application of novel Cas proteins like CasΦ, framing them within the broader context of developing next-generation CRISPR biosensors for pathogen detection.

Principles of Amplification-Free Detection

The Trans-Cleavage Mechanism

The cornerstone of amplification-free CRISPR detection is the trans-cleavage activity (or collateral activity) exhibited by Cas proteins such as Cas12, Cas13, and Cas14 [1]. The detection mechanism unfolds in a sequence of critical steps, illustrated in the following diagram:

Amplification-Free CRISPR Detection Mechanism

- Complex Formation: A guide RNA (crRNA), designed to be complementary to the target pathogen's nucleic acid sequence, forms a complex with a Cas protein (e.g., Cas12a) [2].

- Target Recognition and Activation: This ribonucleoprotein complex scans the sample. Upon recognizing and binding to its specific target sequence (e.g., a viral DNA sequence), the Cas protein undergoes a conformational change that activates its catalytic site [2].

- Collateral Cleavage and Signal Generation: The activated Cas protein unleashes its non-specific trans-cleavage activity, indiscriminately degrading nearby reporter molecules. These reporters are typically single-stranded DNA (for Cas12) or RNA (for Cas13) labeled with a fluorophore and a quencher; cleavage separates the two, generating a fluorescent signal [1] [26]. The key is that a single target-binding event triggers the cleavage of thousands of reporters, leading to massive signal amplification at the molecular level without the need for nucleic acid amplification [27].

Comparative Advantages Over Amplification-Based Methods

Eliminating the amplification step bestows several critical advantages for diagnostic applications, particularly for point-of-care use:

- Speed: Detection times are substantially reduced, often to within 30-60 minutes, as there is no need for lengthy thermal cycling or isothermal amplification [1] [27].

- Simplicity and Portability: The workflow is significantly simplified, making it more amenable to miniaturization and integration into portable, low-cost devices [2] [21].

- Reduced Contamination Risk: Without target amplification, the risk of false positives due to amplicon contamination in the lab or clinical setting is minimized [1].

- Direct Quantification: Some amplification-free platforms, like digital droplet CRISPR, preserve the ability for quantitative analysis, as the initial target concentration is directly linked to the signal generation rate [1] [15].

Key Amplification-Free Strategies

Cascade CRISPR Systems

Cascade CRISPR systems represent a powerful multi-enzyme strategy designed to enhance the sensitivity of amplification-free detection. These systems sequentially employ two or more different CRISPR-Cas complexes to create a signal amplification cascade.

A typical workflow for a DNA target might involve an initial Cas protein dedicated to target recognition, which then activates a second Cas protein with strong trans-cleavage activity to generate the detectable signal. For instance, a Type I CRISPR complex (which has high sensitivity for target binding but lacks strong trans-cleavage) can be used to activate a Cas12a enzyme, which then degrades a fluorescent reporter [1]. This sequential activation creates a two-stage amplification process, significantly boosting the signal compared to a single-Cas system. The logical flow of a cascade system is outlined below:

Cascade CRISPR System Workflow

The primary advantage of cascade systems is their ability to achieve exceptional sensitivity (down to attomolar levels) while maintaining single-base specificity, all without nucleic acid amplification [1] [27]. This makes them particularly suitable for detecting low-abundance pathogens in complex clinical samples.

Digital Droplet CRISPR

Digital droplet CRISPR is a breakthrough technology that marries the principles of digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) with the specificity of CRISPR-Cas detection. This method enables the absolute quantification of nucleic acid targets without amplification by partitioning a sample into tens of thousands of nanoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets [1] [28] [29].

Each droplet functions as an isolated micro-reactor containing the CRISPR-Cas reagents. The partitioning process is highly dilute, meaning that most droplets contain either zero or one target molecule. Following incubation, droplets that contain the target pathogen nucleic acid will generate a fluorescent signal due to Cas-mediated trans-cleavage of reporters, while negative droplets remain dark. An automated droplet reader then counts the fluorescent (positive) and non-fluorescent (negative) droplets. The absolute concentration of the target in the original sample is calculated using Poisson statistics based on the ratio of positive to total droplets [1] [29]. This workflow provides a direct and precise count of target molecules.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Digital Droplet PCR (Reference Technology)

| Metric | Performance in ddPCR [29] | Significance for Digital Droplet CRISPR |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 95% concordance with gold-standard PFGE | Suggests potential for highly accurate quantitative results. |

| Precision | 5% average difference from reference method | Indicates high reproducibility and reliability. |

| Quantification | Absolute quantification without standards | Enables direct copy number measurement of pathogen DNA/RNA. |

| Sensitivity | Capable of detecting copy number variations | Suitable for detecting low viral loads or bacterial loads. |

This platform is ideal for applications requiring precise quantification, such as monitoring viral load in patients or determining the concentration of a specific bacterium in an environmental sample [1].

Novel Cas Proteins: CasΦ (Cas12j)

The CRISPR toolbox is continually expanding with the discovery of novel Cas proteins. CasΦ (classified as Cas12j) is a particularly promising enzyme for amplification-free diagnostics due to its unique properties [1]. Unlike the widely used Cas12a, CasΦ is a hypercompact protein, encoded by a much smaller gene. This small size facilitates easier delivery and packaging, which is advantageous for both therapeutic and diagnostic applications [1].

Despite its size, CasΦ possesses a strong and efficient trans-cleavage activity against single-stranded DNA reporters upon activation by a double-stranded DNA target [1]. Its compact and efficient nature may lead to faster reaction kinetics and lower reagent costs, making it an excellent candidate for integration into next-generation, low-cost, rapid diagnostic tests. Research into CasΦ is still evolving, but it holds significant potential for simplifying assay design and improving the performance of amplification-free platforms [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for an Amplification-Free CRISPR-Cas13a Assay

This protocol details the steps for detecting an RNA virus (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) using an amplification-free Cas13a system, capable of achieving detection within 30 minutes [1].

A. Reagent Preparation

- Lbu Cas13a Protein: Purified and diluted to a working concentration in nuclease-free buffer.

- crRNA: Design a crRNA complementary to a conserved region of the target viral RNA (e.g., the N gene). Resuspend in nuclease-free water to a stock concentration of 100 µM.

- Fluorescent Reporter: A synthetic ssRNA oligonucleotide labeled with a 5' fluorophore (e.g., FAM) and a 3' quencher (e.g., BHQ-1). Resuspend to a working concentration.

- Reaction Buffer: Prepare a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, pH 6.8.

B. Assay Workflow

- Sample Processing: Extract RNA from patient swabs (nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal) using a quick extraction method (e.g., 5-minute heat shock at 95°C in extraction buffer) to release viral RNA. Centrifuge briefly to pellet debris.

- Reaction Setup: In a 0.2 mL PCR tube or a microfluidic chamber, mix the following on ice:

- 5 µL of 2X Reaction Buffer

- 1 µL of Lbu Cas13a (final conc. 100 nM)

- 1 µL of crRNA (final conc. 20 nM)

- 1 µL of Fluorescent Reporter (final conc. 500 nM)

- 2 µL of Nuclease-free Water

- 5 µL of extracted RNA sample Total Volume: 15 µL

- Signal Acquisition:

- Immediately transfer the reaction tube to a real-time PCR instrument or a fluorescent plate reader pre-heated to 37°C.

- Measure the fluorescence signal (FAM channel) every 30 seconds for 30 minutes.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot fluorescence intensity over time.

- A positive sample is identified by a significant increase in the fluorescence slope compared to a negative control.

- The time-to-positive or the slope of the curve can be correlated with the initial viral load for semi-quantification.

Protocol for Digital Droplet CRISPR Assay

This protocol adapts the above CRISPR assay to a digital droplet format for absolute quantification [1] [28].

A. Reagent Preparation (Similar to Protocol 4.1, but with droplet-compatible supermix)

- Cas12a/crRNA Complex: Pre-complex Cas12a protein with target-specific crRNA.

- Droplet Digital PCR Supermix: Use a commercial ddPCR supermix (e.g., Bio-Rad ddPCR Supermix for Probes, No dUTP) [28].

- ssDNA Reporter: A fluorescent ssDNA probe (e.g., HEX/ZEN/Iowa Black FQ quenched probe).

- Droplet Generation Oil: Specific oil for probe-based assays [28].

B. Assay Workflow

- Reaction Assembly: Prepare a master mix on ice:

- 11 µL of ddPCR Supermix

- 1 µL of Cas12a/crRNA Complex

- 1 µL of ssDNA Reporter

- 4 µL of extracted DNA sample or directly lysed sample Total Volume: 17 µL

- Droplet Generation:

- Load the 20 µL reaction mix and 70 µL of Droplet Generation Oil into a DG8 Cartridge [28].

- Place the cartridge into a droplet generator. This instrument partitions the sample into ~20,000 nanoliter droplets.

- PCR Amplification (Optional) and CRISPR Reaction:

- Carefully transfer the generated droplets to a 96-well PCR plate.

- Seal the plate and place it in a thermal cycler. If including an amplification step for ultra-high sensitivity, run a PCR protocol. For a purely amplification-free assay, incubate the plate at 37°C for 60 minutes to allow the CRISPR reaction to proceed.

- Droplet Reading and Analysis:

- After incubation, transfer the plate to a droplet reader.

- The reader streams each droplet individually past a fluorescence detector.

- Droplets containing the target molecule (and thus exhibiting Cas collateral cleavage) will be brightly fluorescent and are counted as positive events.

- Quantification:

- The reader's software uses Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration of the target sequence (in copies/µL) in the original sample based on the fraction of positive droplets.