Comparative Performance of Metabolic Pathway Optimization Methods: From Foundational Algorithms to AI-Driven Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the performance of metabolic pathway optimization methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Performance of Metabolic Pathway Optimization Methods: From Foundational Algorithms to AI-Driven Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the performance of metabolic pathway optimization methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of constraint-based modeling, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). The review delves into advanced methodological frameworks such as topology-informed optimization (TIObjFind) and machine learning applications, examining their use in predicting flux distributions and engineering microbial cell factories. It addresses common troubleshooting challenges in parameter estimation and model refinement, and critically validates method performance through case studies in biotechnology and oncology. By synthesizing insights across these four intents, this analysis aims to guide the selection and application of optimal strategies for metabolic engineering and pharmaceutical research.

Core Principles: Understanding the Fundamental Frameworks of Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) as a Cornerstone Constraint-Based Modeling Approach

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a fundamental computational method in systems biology for predicting the flow of metabolites through metabolic networks. By relying on stoichiometric models and optimization principles, FBA enables the study of cellular metabolism without requiring detailed kinetic parameters. This guide compares its performance against other constraint-based modeling approaches, detailing their methodologies, applications, and experimental protocols.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a mathematical approach used to understand the flow of metabolites through a biochemical network. It uses a numerical matrix of stoichiometric coefficients from a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) to impose constraints and create a solution space of possible metabolic fluxes. An optimization function is then applied to identify the specific flux distribution that maximizes a biological objective (e.g., biomass production or metabolite export) while satisfying these constraints [1]. A key assumption is that the metabolic system operates at a steady state, where metabolite concentrations do not change over time [1].

Several advanced frameworks have been developed to address specific limitations of traditional FBA:

- TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to identify context-specific metabolic objectives. It assigns Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) to quantify each reaction's contribution to a cellular goal, aligning model predictions with experimental flux data. This is particularly useful for capturing metabolic shifts under changing environmental conditions [2] [3].

- ObjFind, a precursor to TIObjFind, also infers objective functions by maximizing a weighted sum of fluxes while minimizing the deviation from experimental data. However, it weights all metabolites and can be prone to overfitting [2].

- Enzyme-Constrained Models, such as those built with the ECMpy workflow, add constraints based on enzyme availability and catalytic efficiency (kcat values). This prevents FBA from predicting unrealistically high fluxes and improves prediction accuracy without altering the structure of the original GEM [1].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these related approaches.

Table: Comparison of Constraint-Based Metabolic Modeling Approaches

| Method | Core Innovation | Key Inputs | Primary Output | Major Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBA [1] | Static optimization of a biological objective | Stoichiometric matrix, exchange bounds | Flux distribution maximizing objective | Simple, fast, requires no kinetic parameters |

| TIObjFind [2] [3] | Infers objective from data using network topology | FBA model, experimental flux data | Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), data-aligned fluxes | Identifies context-specific metabolic goals |

| ObjFind [2] | Infers objective as a weighted sum of fluxes | FBA model, experimental flux data | Weighted objective function, flux distribution | Captures multi-objective optimization |

| Enzyme-constrained FBA (e.g., ECMpy) [1] | Incorporates enzyme capacity constraints | Stoichiometric matrix, enzyme kcat values, protein mass fraction | Enzyme-efficient flux distribution | Avoids unrealistic high flux predictions |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Practical application of these methods requires a structured workflow, from model preparation to simulation and validation. The following diagram outlines a generalized protocol for conducting FBA and related analyses.

Protocol 1: Standard FBA for Metabolite Overproduction

This protocol details the steps for using FBA to engineer a microbial strain for enhanced metabolite production, as demonstrated in an L-cysteine overproduction study [1].

Step 1: Model Selection and Curation

Step 2: Incorporation of Genetic Modifications

- Modify model parameters to reflect engineered enzymes. This includes updating kcat values to reflect increased enzyme activity and gene abundance levels to represent stronger promoters or increased plasmid copy number [1].

- Example Modification: To model a mutant SerA enzyme without feedback inhibition, the kcat for the PGCD reaction was increased from 20 1/s to 2000 1/s [1].

Step 3: Definition of Environmental Conditions

- Set the upper bounds for metabolite uptake reactions to reflect the culture medium (e.g., SM1 + LB broth). These bounds are calculated based on the initial concentration and molecular weight of each component [1].

- Example: The upper bound for glucose uptake (EX_glc__D_e) was set to 55.51 mmol/gDW/h [1].

Step 4: Simulation and Optimization

- Use a computational package like COBRApy to perform FBA [1].

- To avoid solutions with no cell growth, apply lexicographic optimization: first optimize for biomass, then constrain the model to require a percentage of that optimal growth (e.g., 30%) while optimizing for the target product (e.g., L-cysteine export) [1].

Protocol 2: Identifying Metabolic Objectives with TIObjFind

The TIObjFind framework is used to infer a cell's metabolic objectives from experimental data, which is crucial when the objective function is not known a priori [2] [3].

Step 1: Formulate the Optimization Problem

- The framework solves a problem that minimizes the difference between FBA-predicted fluxes ((v)) and experimental flux data ((v^{exp})), while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal represented by a weighted sum of fluxes ((c^{obj} \cdot v)) [2].

Step 2: Construct a Mass Flow Graph (MFG)

- Map the FBA solution onto a directed, weighted graph where nodes represent reactions and edges represent metabolic flows [2].

Step 3: Apply Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA)

- Use a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) on the MFG to identify critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs). These coefficients act as pathway-specific weights in the objective function [2].

Step 4: Validation with Case Studies

- The method was validated by analyzing the fermentation of glucose by Clostridium acetobutylicum and a multi-species system, showing a good match with experimental data and successfully capturing stage-specific metabolic objectives [3].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The table below synthesizes key experimental outcomes and performance metrics from studies utilizing different FBA-based approaches.

Table: Experimental Performance of FBA and Advanced Frameworks

| Modeling Approach | Organism/System | Primary Objective | Key Experimental Outcome / Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-Constrained FBA (ECMpy) [1] | E. coli K-12 | L-cysteine overproduction | Generated feasible flux distributions reflecting engineered enzymes (SerA, CysE); Addressed unrealistic flux predictions by capping fluxes with enzyme availability. |

| TIObjFind [2] [3] | Clostridium acetobutylicum | Identify stage-specific objectives | Reduced prediction error and improved alignment with experimental flux data during fermentation; Quantified shifting reaction priorities (CoIs). |

| TIObjFind [2] [3] | Multi-species IBE system | Assess cellular performance | Achieved a good match with observed experimental data; Successfully captured metabolic objectives for each species in a co-culture. |

| FluTO (Trade-off Analysis) [4] | E. coli, S. cerevisiae | Identify metabolic trade-offs | Identified invariant reaction fluxes and absolute trade-offs dependent on available carbon sources using Flux Variability Analysis (FVA). |

Successful implementation of FBA and related methods relies on key computational tools and databases.

Table: Key Resources for Constraint-Based Metabolic Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| COBRApy [1] | Software Toolbox | A Python package for performing constraint-based reconstructions and analysis, including FBA simulations. |

| ECMpy [1] | Software Workflow | Used to add enzyme constraints to a GEM without altering the stoichiometric matrix, improving flux prediction accuracy. |

| iML1515 [1] | Genome-Scale Model | A highly curated metabolic model of E. coli K-12 MG1655, serving as a base model for simulations and engineering. |

| BRENDA [1] | Database | A comprehensive enzyme information database used to obtain enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat values). |

| EcoCyc [1] | Database | A curated database of E. coli biology, used for model curation, gap-filling, and verifying Gene-Protein-Reaction relationships. |

| TIObjFind Code [2] | Software Framework | A MATLAB-based implementation for identifying metabolic objectives using the TIObjFind framework. |

Flux Balance Analysis remains a cornerstone for modeling metabolic networks. While standard FBA is powerful, the emergence of frameworks like enzyme-constrained FBA and TIObjFind addresses its limitations in prediction realism and adaptability. The choice of method depends on the research goal: enzyme-constrained models are superior for predicting flux distributions under enzyme limitations, while TIObjFind is more effective for inferring cellular objectives from omics data. Understanding these comparative strengths allows researchers to select the optimal tool for metabolic engineering and drug development.

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) and Their Role in Linking Genotype to Phenotype

Genome-scale metabolic models are comprehensive computational representations of the metabolic network of an organism. They provide a mathematical framework that encapsulates the relationship between an organism's genotype and its metabolic phenotype. A GEM catalogs all known metabolic reactions within a cell, systematically linking them to the corresponding genes, enzymes, and metabolites. This is formalized through Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations, which create a direct connectome from genetic information to catalytic function and ultimately to biochemical transformation [5] [6]. The core of a GEM is the stoichiometric matrix (S matrix), a mathematical structure where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions. This matrix enforces mass-balance constraints, ensuring that the consumption and production of each metabolite are balanced within the network [7].

The primary computational method used to simulate GEMs is Flux Balance Analysis. FBA calculates the flow of metabolites through this metabolic network, enabling the prediction of growth rates, metabolic flux distributions, and nutrient uptake rates under steady-state conditions. By optimizing a defined biological objective—such as biomass production—FBA can predict phenotypic outcomes from genotypic information [5] [7]. The first GEM was reconstructed for Haemophilus influenzae in 1999. Since then, the field has expanded dramatically, with models now available for thousands of organisms across bacteria, archaea, and eukarya. As of February 2019, GEMs had been reconstructed for 6,239 organisms, including 5,897 bacteria, 127 archaea, and 215 eukaryotes [6]. This extensive coverage makes GEMs a powerful platform for contextualizing big data, enabling researchers to move from mere data collection to meaningful biological interpretation and phenotypic prediction.

Comparative Performance of GEMs Against Alternative Methods

The utility of GEMs is best evaluated by comparing their predictive capabilities and applications against other metabolic modeling approaches. The table below summarizes this comparative performance across several key criteria.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Metabolic Pathway Optimization Methods

| Criterion | GEMs (Constraint-Based) | Kinetic Models | Stoichiometric Models (Non-Genome Scale) | Isolated Omics Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype-Phenotype Link | Direct, via GPR rules [5] [6] | Indirect (requires kinetic parameters) | No direct link | Correlative, not mechanistic |

| Network Coverage | Comprehensive, genome-wide [6] | Pathway-specific | Limited, core metabolism only | Comprehensive but non-mechanistic |

| Data Integration Capacity | High (multi-omics) [5] [8] | Low (requires specific parameters) | Medium (flux data) | High but non-integrative |

| Phenotype Prediction | Quantitative (growth, fluxes) [6] [7] | Quantitative (dynamics) | Quantitative (steady-state fluxes) | Qualitative |

| Gene Essentiality Prediction | High accuracy (e.g., 93.4% in iML1515 E. coli model) [6] | Possible but parameter-dependent | Not applicable | Not directly applicable |

| Drug Target Identification | Established success in pathogens [6] [8] | Limited by parameter availability | Limited | Based on expression, not function |

| Time & Resource Requirements | Moderate (reconstruction); Fast (simulation) | High (parameter estimation) | Low to Moderate | Low (analysis only) |

Key Performance Advantages of GEMs

- Predictive Accuracy: High-quality GEMs demonstrate exceptional predictive performance for essential metabolic functions. For example, the E. coli model iML1515 achieves 93.4% accuracy in predicting gene essentiality under minimal media with different carbon sources [6]. Furthermore, consensus models built using tools like GEMsembler, which integrate multiple individual reconstructions, have been shown to outperform even manually curated gold-standard models in predictions of auxotrophy and gene essentiality [9].

- Scope and Versatility: Unlike kinetic models that are often restricted to well-characterized pathways due to a lack of reliable enzyme kinetic data, GEMs offer genome-wide coverage. This allows for system-wide investigations, including the study of non-intuitive network effects that emerge from the interconnection of metabolic pathways [5] [6]. Their ability to integrate various omics data types (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) makes them superior to isolated omics analyses, which often struggle to establish mechanistic links [5].

- Application Range: GEMs support a wider and more impactful range of applications than other methods. They are uniquely positioned to guide metabolic engineering for chemical production, identify drug targets in pathogens, elucidate host-microbe interactions, and understand the metabolic basis of human diseases [6] [8] [10]. Their capacity to build context-specific models for particular tissues or cell lines provides a level of personalization and functional insight that other methods cannot easily replicate [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Protocol: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

Flux Balance Analysis is the cornerstone computational method for simulating GEMs. The protocol involves several key steps designed to predict metabolic flux distributions that optimize a cellular objective.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for GEM Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [7] | Software Package (MATLAB) | Simulation and analysis of constraint-based models | FBA, CSOM, gene deletion studies |

| COBRApy [7] | Software Package (Python) | Python version of COBRA tools | FBA, CSOM, gene deletion studies |

| GEMsembler [9] | Software Package (Python) | Builds consensus models from multiple reconstructions | Improving model accuracy and performance |

| AGORA2 [10] | Database & Framework | Curated GEMs for 7,302 gut microbes | Host-microbiome and LBP research |

| Gene Expression Data (e.g., RNA-Seq) [11] | Omics Data | Defines active reactions in context-specific models | Building cell line- or tissue-specific models |

| Exometabolomics Data [11] | Experimental Data | Constrains uptake/secretion fluxes in models | Refining model constraints with experimental measurements |

Step 1: Network Reconstruction and Matrix Formulation. The process begins with the construction of the stoichiometric matrix S, where each element Sᵢⱼ represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. This matrix defines the system's solution space, encompassing all possible flux distributions [7].

Step 2: Application of Physiological Constraints. The solution space is constrained to physiologically relevant states by defining lower and upper bounds (lb and ub) for each reaction rate (flux), typically expressed in mmol/gDW/h. For example, glucose uptake might be constrained to a measured value, and irreversible reactions are set to have non-negative fluxes [11] [7].

Step 3: Objective Function Definition. A biological objective function is chosen and linear programming is used to find a flux vector v that maximizes or minimizes this objective. The most common objective is the biomass reaction, which represents the composition of essential macromolecules needed for cellular growth, thereby simulating growth rate maximization [11] [7].

Step 4: Problem Formulation and Optimization. The FBA problem is formally defined as: Maximize Z = cᵀv (where Z is the objective, and c is a vector indicating the coefficient for each reaction in the objective). Subject to: S ∙ v = 0 (mass balance) and lb ≤ v ≤ ub (flux constraints) [7].

Step 5: Simulation and Output Analysis. The optimized flux distribution v is analyzed to predict growth phenotypes, nutrient uptake, byproduct secretion, and essential genes. Validation is performed by comparing these predictions against experimental data, such as measured growth rates or gene essentiality screens [6] [11].

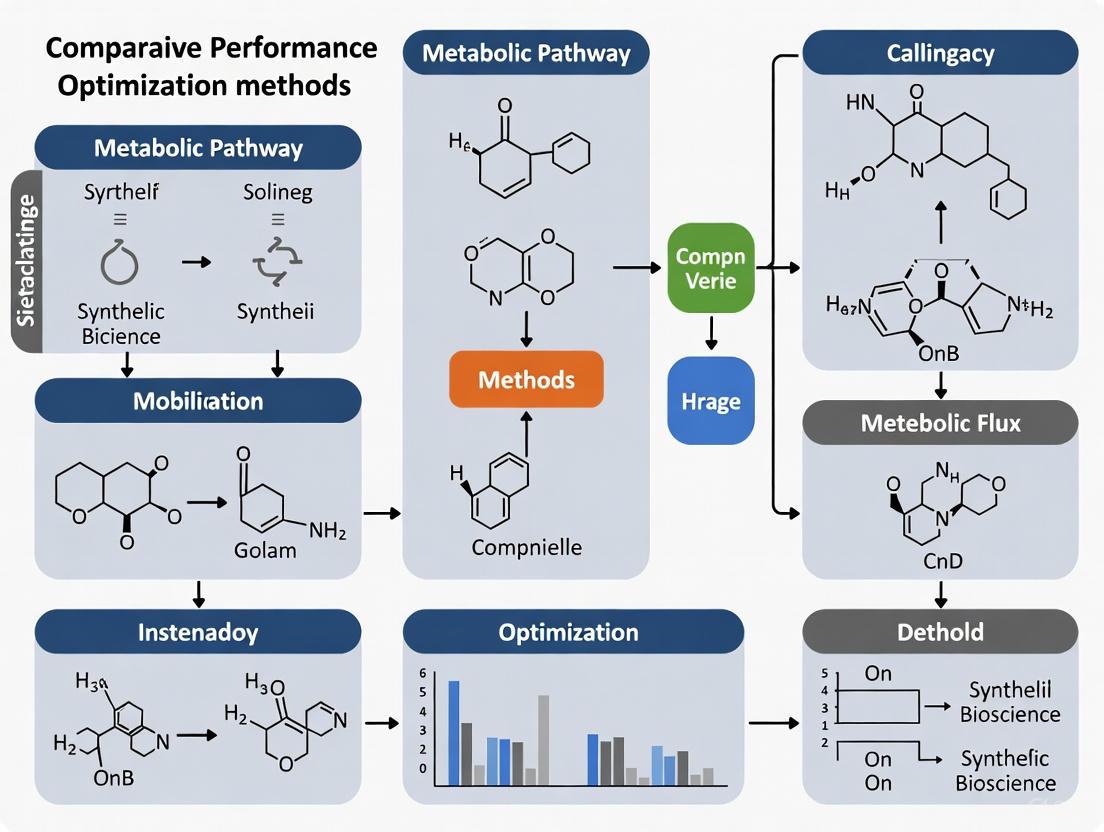

Figure 1: The Flux Balance Analysis Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in FBA, from network reconstruction to phenotype prediction.

Protocol for Building Context-Specific Models

The creation of cell line- or tissue-specific models from a generic GEM is a critical protocol for many biomedical applications. A systematic evaluation has shown that the choice of algorithm, gene expression threshold, and input constraints significantly impacts the predictive accuracy of the resulting models [11].

Step 1: Data Preparation. Collect and pre-process omics data, most commonly transcriptomics data (e.g., RNA-Seq). A threshold must be chosen to determine which genes are considered "expressed" and thus active in the specific context [11].

Step 2: Selection of Model Extraction Method (MEM). Choose an algorithm tailored to the available data and research question. The main families of MEMs are [11]:

- GIMME-like: Minimizes flux through reactions associated with low-expression genes while maintaining a defined objective (e.g., growth).

- iMAT-like: Finds an optimal trade-off between including reactions linked to highly expressed genes and removing reactions associated with low-expression genes.

- MBA-like: Uses a set of high-confidence "core" reactions (e.g., based on expression) that must be active, and parsimoniously removes other non-essential reactions.

Step 3: Model Constraining. Integrate available exometabolomic data to constrain the uptake and secretion fluxes of the model, creating a more physiologically realistic input model for the extraction process. This can range from "unconstrained" (all exchanges open) to "fully constrained" (exchanges set to measured values) [11].

Step 4: Model Extraction and Validation. Execute the chosen MEM to produce a context-specific model. The model must then be validated by assessing its ability to predict functional outcomes, with gene essentiality prediction compared against CRISPR-Cas9 screens being a key benchmark [11].

Figure 2: Context-Specific Model Construction. This chart illustrates the process of building tailored models using omics data and different extraction algorithms.

Quantitative Performance Data and Benchmarking

Performance Across Model Organisms

The predictive power of GEMs is rigorously benchmarked against experimental data. The following table compiles key performance metrics for high-quality, manually curated GEMs of several model organisms.

Table 3: Performance Benchmarks of Manually Curated GEMs

| Organism | Model Name | Genes in Model | Key Prediction Accuracy | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli [6] | iML1515 | 1,515 | 93.4% (Gene Essentiality) | Metabolic Engineering, Core Metabolism |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae [6] | Yeast 7 | >1,000 | High (Growth on Different Carbon Sources) | Biotechnology, Eukaryotic Metabolism |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis [6] | iEK1101 | 1,101 | Validated for in vivo Hypoxic State | Drug Target Identification |

| Bacillus subtilis [6] | iBsu1144 | 1,144 | Incorporates Thermodynamic Constraints | Gram-Positive Bacteria, Enzyme Production |

| Homo sapiens (Recon series) [11] | Recon 1 / 2.2 | N/A | Benchmark for Context-Specific Models | Disease Modeling, Drug Target Discovery |

Performance of Model Extraction Algorithms

A critical comparative study evaluated six prominent MEMs by building hundreds of models for four cancer cell lines (A375, HL60, K562, KBM7). The models were assessed based on their content and, most importantly, their accuracy in predicting gene essentiality as measured by CRISPR-Cas9 screens [11]. The study revealed a clear hierarchy of factors influencing model accuracy:

- Choice of Algorithm: The model extraction method itself had the largest impact on predictive accuracy [11].

- Gene Expression Threshold: The threshold used to define "expressed" genes significantly affected which reactions were included in the model.

- Metabolic Constraints: The use of exometabolomic data to constrain uptake and secretion fluxes further refined model predictions.

This benchmarking effort provides researchers with crucial guidance for selecting appropriate methods and parameters when building context-specific models for studying human diseases, ensuring the highest possible predictive fidelity [11].

Applications in Drug Development and Biotechnology

The ability of GEMs to link genotype to phenotype has enabled transformative applications across biotechnology and medicine, demonstrating their superiority in tackling complex biological problems.

Drug Target Identification in Pathogens: GEMs of pathogenic bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, have been extensively used to simulate metabolism under in vivo conditions (e.g., hypoxic states) to identify essential metabolic functions that can be targeted by new antibiotics [6]. Furthermore, multi-strain GEMs of species like Klebsiella pneumoniae and Salmonella allow for the identification of conserved, strain-independent drug targets, as well as strain-specific virulence factors [5] [6].

Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs): GEMs are guiding the rational design of next-generation microbiome-based therapeutics. Frameworks like AGORA2, which contains 7,302 curated GEMs of gut microbes, enable the in silico screening of bacterial strains for desired therapeutic functions. This includes predicting the production of beneficial postbiotics (e.g., short-chain fatty acids), assessing interactions with host cells and resident microbes, and optimizing multi-strain consortia for treating conditions like Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Parkinson's disease [10].

Understanding Human Diseases: Systematic reviews have cataloged a vast number of studies applying GEMs to investigate cancer, metabolic disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases. By building context-specific models of diseased tissues or cell lines, researchers can identify metabolic drivers of pathology and repurposable drug targets [8]. The capacity of GEMs to integrate patient-specific data paves the way for personalized metabolic medicine.

Constraint-based metabolic modeling provides a powerful mathematical framework for analyzing cellular metabolism at the genome scale without requiring detailed kinetic parameters. These approaches rely on stoichiometric models of metabolic networks that impose mass-balance constraints, with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serving as the cornerstone methodology for predicting steady-state metabolic fluxes. FBA formulates cellular metabolism as a linear programming problem that optimizes an objective function—typically biomass production for microbial systems—within stoichiometric and capacity constraints [3] [2].

The accurate prediction of metabolic behavior across varying environmental conditions and genetic backgrounds remains challenging due to the critical dependence of FBA on the selected objective function. Traditional implementations often assume a single, static objective that may not reflect the adaptive priorities of cells in dynamic environments. This limitation has prompted the development of advanced frameworks that better capture flux variations observed in experimental data, leading to more accurate and biologically relevant model predictions [3] [2] [12].

This guide comprehensively compares contemporary methods for metabolic pathway optimization, with particular emphasis on their approaches to objective function selection and capability to capture flux variations. We evaluate computational frameworks based on their underlying algorithms, data requirements, and performance in predicting metabolic behaviors under different biological conditions.

Comparative Analysis of Metabolic Optimization Methods

The table below summarizes key methodological approaches for metabolic pathway optimization, highlighting their strategies for addressing objective function selection and flux variation challenges.

Table 1: Comparison of Metabolic Pathway Optimization Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Objective Function Strategy | Handling of Flux Variations | Experimental Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind | Integrates FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) | Infers objective via Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) | Uses flux-dependent weighted reaction graph to capture adaptive shifts | Experimental flux data for pathway weighting |

| Traditional FBA | Linear programming optimization | User-defined single objective (e.g., biomass max) | Limited; assumes static cellular objectives | Optional for validation |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | Flux range calculation via multiple LPs | Requires predefined objective function | Quantifies feasible flux ranges under optimality | Optional constraint tightening |

| Flux Sampling | Random sampling of solution space | Objective-independent or optionally constrained | Maps probability distributions of flux solutions | Can incorporate data as constraints |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Pattern identification from multi-omics data | Learned from data correlations | Predicts dynamics from proteomic/metabolomic time-series | Time-series multi-omics data |

| Metaheuristic Algorithms (PSO, ABC, CS) | Evolutionary optimization strategies | Multi-objective optimization | Identifies knockout strategies for flux redistribution | Fitness evaluation data |

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Case Studies

| Method | Prediction Error Reduction | Condition-Specific Adaptation | Computational Intensity | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind | 35-60% reduction vs traditional FBA | High - captures stage-specific metabolic objectives | Medium (requires pathway analysis) | High (pathway-level CoIs) |

| Traditional FBA | Baseline | Limited - single objective across conditions | Low | Medium |

| Improved FVA Algorithm | Not quantified | Medium - identifies flexible/rigid reactions | High (solves multiple LPs) | Medium (flux ranges) |

| Flux Sampling (CHRR) | Not primarily error-focused | High - maps entire solution space without objective bias | High (sampling convergence) | Low (probabilistic) |

| Machine Learning | 20-45% vs kinetic models | High - data-driven dynamic predictions | Varies with model training | Low (black-box) |

| PSOMOMA | 15-30% production rate improvement | Medium - predicts mutant flux distributions | Medium (population-based optimization) | Medium |

Detailed Methodological Examination

TIObjFind: Topology-Informed Objective Identification

The TIObjFind framework represents a significant advancement in addressing objective function selection challenges by integrating FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) to systematically infer cellular objectives from experimental data [3] [2]. This approach introduces Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each metabolic reaction's contribution to an inferred objective function, effectively distributing importance across pathways rather than focusing on a single reaction.

The TIObjFind methodology follows a structured three-step process. First, it formulates objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal. Second, it maps FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG), enabling pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions. Finally, it applies a minimum-cut algorithm (specifically the Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm) to extract critical pathways and compute CoIs, which serve as pathway-specific weights in optimization [3] [2]. This approach has demonstrated a 35-60% reduction in prediction errors compared to traditional FBA in case studies involving Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation, successfully capturing stage-specific metabolic objectives during batch fermentation [3].

Flux Variability Analysis: Enhanced Algorithmic Approaches

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) addresses the degeneracy problem in FBA solutions by quantifying the feasible ranges of reaction fluxes that maintain optimal or sub-optimal biological objective function values [13]. Traditional FVA requires solving 2n+1 linear programming problems (where n is the number of reactions), creating significant computational burdens for large-scale metabolic models.

Recent algorithmic improvements leverage the basic feasible solution property of linear programs to reduce computational requirements. By inspecting intermediate solutions, these enhanced algorithms identify when flux variables have already attained their maximum or minimum possible values during earlier optimization steps, eliminating redundant calculations [13]. Implementation considerations include using the primal simplex method rather than dual simplex, as the former allows warm-starting subsequent linear programs from previous solutions, reducing solve times by 30-100% [13]. Benchmarking on metabolic models ranging from yeast (iMM904) to human metabolism (Recon3D) demonstrates significant reductions in both the number of linear programs required and total solution time [13].

Flux Sampling: Objective-Independent Solution Space Analysis

Flux sampling methods provide an alternative approach to metabolic network analysis that minimizes observer bias by not assuming any particular cellular objective function [12]. These methods generate probability distributions of steady-state reaction fluxes by randomly sampling the feasible solution space, offering comprehensive insights into metabolic capabilities across changing environmental conditions.

A rigorous comparison of sampling algorithms identified the Coordinate Hit-and-Run with Rounding (CHRR) algorithm as the most efficient method, demonstrating run-times 2.5-8 times faster than alternative approaches across models of varying complexity [12]. When applied to study photosynthetic acclimation to cold in Arabidopsis thaliana, flux sampling revealed the regulated interplay between diurnal starch and organic acid accumulation that defines plant acclimation processes, predicting γ-aminobutyric acid as having a key role in metabolic signaling under cold conditions [12]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying organisms where cellular objectives are not well-defined or may shift in response to environmental perturbations.

Machine Learning and Metaheuristic Approaches

Machine learning methods offer a fundamentally different approach to predicting metabolic pathway dynamics by learning relationships between system components directly from multi-omics data without presuming specific functional forms [14]. These methods frame metabolic prediction as a supervised learning problem where algorithms learn to predict metabolite time derivatives from proteomic and metabolomic concentrations [14]. In studies of limonene and isopentenol producing pathways, machine learning approaches outperformed classical kinetic models, with prediction accuracy improving systematically as more time-series data was incorporated [14].

Metaheuristic algorithms including Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Artificial Bee Colony (ABC), and Cuckoo Search (CS) have been hybridized with MOMA (Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment) to identify gene knockout strategies that maximize metabolite production [15]. These approaches implement multi-objective optimization balancing competing goals such as production rate and growth rate, generating Pareto-optimal solutions representing trade-offs between objectives. In comparative studies, PSOMOMA demonstrated 15-30% improvements in succinic acid production rates in E. coli while maintaining viable growth rates [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

TIObjFind Implementation Protocol

The experimental implementation of TIObjFind follows a standardized workflow with distinct computational phases. First, researchers must reconstruct or obtain a genome-scale metabolic model for the organism of interest, with networks available from databases such as KEGG or EcoCyc. The model must be converted to appropriate constraint matrices (stoichiometric matrix S, lower/upper flux bounds).

The core TIObjFind analysis proceeds with single-stage optimization using a Karush-Kuhn-Tucker formulation to identify candidate objective functions that minimize squared error between predicted and experimental fluxes. For each candidate objective, the algorithm computes optimal flux distributions, then constructs a Mass Flow Graph where nodes represent metabolic reactions and edge weights correspond to flux values [3] [2].

The final phase applies metabolic pathway analysis using the minimum-cut algorithm to identify essential pathways between designated start (e.g., glucose uptake) and target reactions (e.g., product secretion). The algorithm returns Coefficients of Importance quantifying each reaction's contribution to the inferred cellular objective. Implementation is available in MATLAB with visualization support via Python's pySankey package [3] [2].

Flux Sampling Experimental Protocol

Flux sampling experiments begin with model specification including reaction stoichiometry, thermodynamic constraints (reversibility/irreversibility), and flux bounds based on experimental measurements. For the CHRR algorithm, researchers must determine appropriate sampling parameters including total samples (typically 50,000,000 with thinning), number of saved points (typically 5,000), and convergence criteria [12].

The critical implementation consideration involves validating convergence using diagnostic metrics including autocorrelation analysis and between-chain discrepancy measurements. For the Arabidopsis cold acclimation study, models were constrained with experimentally measured diurnal CO2 uptake and organic carbon accumulation data from both control and cold conditions [12]. The resulting flux samples enabled comparison of solution space properties across conditions, revealing metabolic adaptations essential for cold tolerance.

Visualization of Key Concepts

TIObjFind Workflow Diagram

Flux Analysis Methods Relationship

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Metabolic Flux Optimization Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Databases | KEGG, EcoCyc | Pathway information and genomic annotations | Network reconstruction and validation |

| Modeling Software | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB), COBRApy (Python) | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | FBA, FVA, and pathway analysis implementation |

| Optimization Solvers | Gurobi, CPLEX | Linear and quadratic programming solutions | Solving FBA and optimization problems |

| Sampling Algorithms | CHRR, ACHR, OPTGP | Flux space sampling without objective bias | Objective-independent solution space analysis |

| Machine Learning | scikit-learn, TensorFlow | Pattern recognition in multi-omics data | Predictive modeling of pathway dynamics |

| Visualization | pySankey, Graphviz | Metabolic pathway and flux distribution rendering | Results interpretation and presentation |

The accurate selection of objective functions remains a fundamental challenge in metabolic modeling, directly impacting the predictive capability of computational frameworks across varying biological conditions. Traditional FBA with static objectives demonstrates significant limitations in capturing the flux variations observed in experimental studies, particularly during environmental transitions or metabolic adaptations.

Advanced methodologies including TIObjFind, enhanced FVA, flux sampling, and machine learning approaches each offer distinct strategies for addressing these challenges. TIObjFind excels in identifying condition-specific objectives through pathway-level coefficients of importance. Flux sampling provides objective-independent analysis of metabolic capabilities, while machine learning methods leverage multi-omics data to predict dynamic behaviors. The choice among these methods depends on specific research objectives, data availability, and computational resources.

Future methodological developments will likely focus on integrating these approaches, leveraging their complementary strengths to create more comprehensive frameworks for metabolic analysis that better capture the complex, adaptive nature of cellular metabolism across diverse biological conditions.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) for systematic interpretation of flux distributions

Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) serves as a critical methodology for the systematic interpretation of flux distributions within constraint-based metabolic models. As a cornerstone of systems biology, MPA provides researchers with a structured framework to decipher complex cellular metabolic activities, enabling the prediction of cellular behaviors under various genetic and environmental conditions [3] [16]. The integration of MPA with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a powerful approach for understanding how microorganisms dynamically adjust their metabolic priorities, particularly when responding to environmental perturbations or genetic modifications [3]. This combined approach allows scientists to move beyond simple flux prediction toward a more nuanced understanding of metabolic network functionality and cellular adaptation mechanisms.

The fundamental principle underlying MPA is the decomposition of complex metabolic networks into biologically meaningful pathways, facilitating the identification of key metabolic routes and their contributions to overall cellular objectives [3]. This decomposition becomes particularly valuable when analyzing metabolic shifts throughout different stages of biological systems, as it enables researchers to quantify how reactions reorganize their fluxes to maintain cellular functions under changing conditions. For researchers and drug development professionals, MPA offers a computational lens through which to examine potential therapeutic targets, especially in pathogenic organisms where understanding metabolic redundancies and essential pathways can inform treatment strategies [17].

Comparative Analysis of MPA Methodologies and Tools

Table 1: Key Methodologies in Metabolic Pathway Analysis

| Methodology | Primary Function | Key Metrics | Applications | Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind Framework | Identifies metabolic objective functions | Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) | Analysis of adaptive shifts in cellular responses | Aligns optimization results with experimental flux data [3] |

| GEMsembler | Consensus model assembly | Model agreement metrics, functional performance | Model curation, gap identification | Outperforms gold-standard models in auxotrophy and gene essentiality predictions [9] |

| minRerouting Algorithm | Identifies flux rerouting in synthetic lethals | Synthetic lethal clusters, flux switching patterns | Understanding metabolic redundancies, drug target identification | Minimizes rerouting between reaction deletions [17] |

| Improved FVA Algorithm | Determines feasible flux ranges | Flux variability ranges, optimality factors | Identifying high-importance reactions, network flexibility analysis | Reduces computational load by minimizing linear programs solved [13] |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across MPA Tools

| Tool | Computational Basis | Data Requirements | Validation Approach | Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind | Optimization integrating MPA with FBA | Stoichiometric matrix, experimental flux data | Comparison with observed external compounds | Good match with experimental data, captures stage-specific objectives [3] |

| GEMsembler | Python-based consensus building | Multiple GEMs from different reconstruction tools | Auxotrophy and gene essentiality tests | Improved gene essentiality predictions even in gold-standard models [9] |

| minRerouting | Constraint-based optimization p-norm minimization | Genome-scale metabolic models | Comparison with known synthetic lethals and flux distributions | Qualitatively matches experimental flux rates for 16 of 17 reactions in test case [17] |

| Enhanced FVA | Linear programming with solution inspection | Metabolic network stoichiometry | Benchmarking on models from iMM904 to Recon3D | Maintains accuracy while reducing computation time [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Key MPA Methodologies

TIObjFind Protocol for Objective Function Identification

The TIObjFind framework implements a three-stage workflow for identifying context-specific metabolic objective functions from experimental data. First, the algorithm reformulates objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while simultaneously maximizing an inferred metabolic goal [3]. This stage employs linear programming to calculate flux distributions that satisfy both stoichiometric constraints and alignment with experimental observations. Second, the computed FBA solutions are mapped onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG), enabling pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions. This transformation from reaction-centric to pathway-centric view allows researchers to identify dominant metabolic routes under specific conditions. Finally, the framework applies a minimum-cut algorithm (specifically the Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm) to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), which serve as pathway-specific weights in the optimization [3]. These coefficients quantitatively represent each reaction's contribution to the cellular objective function, with higher values indicating reactions whose fluxes align closely with their maximum potential.

The technical implementation of TIObjFind utilizes MATLAB for core computations, with custom code for the main analysis and the minimum cut set calculations performed using MATLAB's maxflow package [3]. For visualization of results, the framework employs Python with the pySankey package to create intuitive diagrams of flux distributions and pathway contributions. Validation studies have demonstrated TIObjFind's effectiveness in case studies including Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation and multi-species isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE) systems, where it successfully identified stage-specific metabolic objectives and showed strong alignment with experimental flux data [3].

GEMsembler Protocol for Consensus Model Assembly

The GEMsembler package addresses the challenge of variability in genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) reconstruction by implementing a consensus-building approach. The protocol begins with collecting multiple GEMs for the same organism reconstructed using different automated tools [9]. The package then performs comprehensive comparative analysis across these models, identifying common metabolic capabilities and tool-specific variations. Using this analysis, GEMsembler constructs consensus models that incorporate metabolic reactions and pathways present in any subset of the input models, effectively creating a unified metabolic network that captures the collective knowledge embedded in the individual reconstructions.

A critical component of the GEMsembler workflow is its agreement-based curation system, which identifies inconsistencies between models and provides guidance for resolution [9]. The package includes functionality for identification and visualization of biosynthesis pathways, growth assessment under different nutrient conditions, and evaluation of gene essentiality predictions. Experimental validation has demonstrated that GEMsembler-curated consensus models built from four Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Escherichia coli automatically reconstructed models outperform manually curated gold-standard models in both auxotrophy and gene essentiality predictions [9]. Furthermore, the optimization of gene-protein-reaction (GPR) combinations from consensus models has been shown to improve gene essentiality predictions, even in manually curated models, highlighting the value of the consensus approach.

Figure 1: GEMsembler Consensus Model Assembly Workflow

minRerouting Protocol for Analyzing Synthetic Lethals

The minRerouting algorithm provides a systematic approach for identifying flux rerouting in synthetic lethal reaction pairs. Synthetic lethals represent pairs of reactions where simultaneous deletion abrogates cell growth, but individual deletion permits survival through metabolic rewiring [17]. The protocol begins with identifying all synthetic lethal pairs in a metabolic model using Fast-SL or similar computational methods. For each synthetic lethal pair, the algorithm solves a minimum p-norm problem to identify flux distributions that satisfy three conditions: adherence to stoichiometric constraints, maximization of biomass objective, and minimization of the number of reactions with varying metabolic flux values [17].

This approach addresses the challenge of multiple flux solutions in FBA by explicitly minimizing metabolic rewiring, based on biological evidence that flux rerouting carries fitness costs that cells seek to minimize. The output of minRerouting is a set of reactions vital for metabolic rewiring, known as the synthetic lethal cluster, which reveals how organisms maintain robustness through redundant pathways. The algorithm has been validated on eight genome-scale metabolic models of bacterial pathogens, including E. coli, Helicobacter pylori, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, showing consistency with previous experimental observations of flux distributions in mutant strains [17]. The protocol has proven particularly valuable for identifying reactions that span different metabolic modules, illustrating the complex inter-pathway connections that enable metabolic flexibility.

Research Reagent Solutions for MPA Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MPA

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application in MPA | Source/Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Provide stoichiometric representation of metabolism | Serve as foundation for flux analysis | BiGG Database, ModelSEED, AGORA [17] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling | Perform FBA, FVA, and pathway analysis | Open-source community development [13] |

| TIObjFind Framework | Identify metabolic objective functions | Determine Coefficients of Importance for reactions | MATLAB implementation with Python visualization [3] |

| GEMsembler | Python package for consensus model assembly | Combine multiple GEMs to improve predictive accuracy | Python-based open-source tool [9] |

| BRENDA Database | Enzyme kinetic parameters | Provide Kcat values for enzyme-constrained models | Curated enzyme database [1] |

| EcoCyc Database | E. coli genes and metabolism database | Curate GPR relationships and reaction directions | Curated organism-specific database [1] |

Visualization of Metabolic Pathways and Flux Distributions

Effective visualization of metabolic pathways and flux distributions represents an essential component of MPA, enabling researchers to interpret complex network behaviors and identify key regulatory points. The integration of MPA with FBA facilitates the creation of flux-dependent weighted reaction graphs that quantitatively represent metabolic flux distributions under different conditions [3]. These graphs transform abstract stoichiometric matrices into intuitive pathway representations, highlighting the relative importance of different metabolic routes and their contributions to cellular objectives.

Figure 2: Metabolic Flux Distribution Visualization Example

For specialized applications such as analyzing L-cysteine overproduction in engineered E. coli strains, MPA enables the detailed tracking of flux through both native and engineered pathways [1]. This includes monitoring flux redistribution through serine biosynthesis, sulfur assimilation, and export mechanisms, while accounting for competing pathways and resource allocation constraints. Visualization tools such as pySankey diagrams can effectively represent these complex flux distributions, highlighting how carbon and sulfur flow through interconnected metabolic networks to achieve production targets [3] [1].

The comparative analysis of MPA methodologies reveals distinct performance advantages across different application scenarios. The TIObjFind framework demonstrates superior capability in identifying context-specific objective functions and quantifying reaction importance through Coefficients of Importance, making it particularly valuable for studying metabolic adaptations in changing environments [3] [16]. GEMsembler consistently outperforms individual model approaches in prediction accuracy, with validated improvements in auxotrophy and gene essentiality predictions compared to gold-standard models [9]. The minRerouting algorithm provides unique insights into metabolic robustness and redundancy, successfully identifying synthetic lethal clusters that represent potential therapeutic targets in pathogenic organisms [17].

The integration of MPA with advanced computational techniques continues to expand the methodology's applications in biotechnology and pharmaceutical development. Future directions include the development of multi-scale approaches that incorporate regulatory information and kinetic parameters, further enhancing the predictive accuracy of metabolic models. For researchers and drug development professionals, these advanced MPA tools offer increasingly sophisticated capabilities for understanding metabolic adaptations in pathogens, identifying novel drug targets, and optimizing microbial strains for industrial applications. The consistent demonstration of improved prediction accuracy across multiple validation studies underscores the growing importance of MPA as an essential component of the systems biology toolkit.

Metabolic pathway databases serve as essential resources for researchers in bioinformatics, systems biology, and metabolic engineering. Among the most widely used are KEGG, MetaCyc, and EcoCyc, each with distinct philosophical approaches, curation methodologies, and application strengths. Understanding their comparative capabilities is crucial for selecting appropriate tools in metabolic pathway optimization research. KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) adopts a broad coverage approach, aiming to catalog all known pathways across diverse organisms. In contrast, MetaCyc focuses on experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways from all domains of life, serving as a curated reference database. EcoCyc specializes in providing deep, literature-based curation for Escherichia coli K-12 substr. MG1655, modeling its complete genome, metabolic pathways, and regulatory network. These databases differ significantly in content scope, curation quality, and applications, factors that critically influence their utility in research workflows ranging from genomic annotation to metabolic engineering and systems biology modeling [18] [19] [20].

Database Scope and Content Comparison

Quantitative Content Analysis

The structural content of these databases varies significantly in terms of pathways, reactions, and compounds, reflecting their different curation philosophies and scope.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Database Contents

| Database Component | KEGG | MetaCyc | EcoCyc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathways | 237 map pathways, 179 module pathways [18] | 3,153 pathways (as of current) [19] | 201 pathways (for E. coli) [20] |

| Reactions | 8,692 total, 6,174 in pathways [18] | 19,020 reactions [19] | Specific to E. coli metabolism |

| Compounds | 16,586 total, 6,912 as substrates [18] | 19,372 metabolites [19] | Comprehensive E. coli metabolome |

| Organisms Covered | Thousands via genomic mapping | 3,443 different organisms [21] | 1 primary organism (E. coli) with 500+ strain databases [22] |

| Literature Citations | Not systematically provided | 76,283 associated citations [21] | 44,000+ publications [20] |

Taxonomic and Metabolic Coverage

The databases exhibit distinct patterns in taxonomic and metabolic coverage. KEGG contains significantly more compounds than MetaCyc, whereas MetaCyc contains significantly more reactions and pathways than KEGG [18]. MetaCyc includes specialized pathways from plants, fungi, metazoa, and actinobacteria that are not found in KEGG, while KEGG provides more comprehensive coverage of xenobiotic degradation, glycan metabolism, and metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides [18]. EcoCyc provides the most complete description of the regulatory network of any organism, including substrate-level enzyme regulation, attenuation, and regulation by small RNAs [20].

Experimental Methodology for Database Comparison

Systematic Comparison Framework

The experimental approach for comparing metabolic databases involves meticulous matching of core components across databases and validation of correspondences. The methodology established in systematic comparisons includes:

- Compound Matching: Utilizing multiple complementary approaches including manual curation, PubChem standardization pipeline, molecular fingerprint matching with Tanimoto coefficient >0.75, and "all-but-one" inference where corresponding reactions have all substrates matched except one pair [23].

- Reaction Correspondence: Establishing reaction mappings through computational and manual methods, evaluating stoichiometric balance, and identifying generic versus specific reaction representations [18].

- Pathway Conceptualization Analysis: Examining differences in how pathways are defined, with KEGG pathways containing 3.3 times as many reactions on average as MetaCyc pathways, reflecting different conceptualizations of metabolic pathways [18].

- Validation Sampling: Random sampling of matched and unmatched objects for manual validation to quantify accuracy of correspondences and identify false negatives [23].

Data Collection and Processing Protocols

The experimental workflow for comprehensive database assessment requires standardized data extraction and processing methods:

- Data Extraction: Utilizing official APIs and data downloads (KEGG SOAP services, BioCyc flatfiles) to ensure complete and consistent data capture across databases [23].

- Schema Normalization: Loading heterogeneous database contents into a unified schema (e.g., Pathway Tools database) to enable comparable queries and analyses [23].

- Attribute Comparison: Systematic evaluation of database attributes beyond core content, including literature citations, taxonomic range annotations, enzyme kinetic data, and regulatory information [18] [21].

- Enrichment/Depletion Analysis: Statistical assessment to detect whether specific metabolic areas are disproportionately represented between databases [23].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Content Quality and Usability Assessment

The databases show significant differences in data quality, annotation richness, and usability for various research applications.

Table 2: Qualitative Feature Comparison for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

| Feature | KEGG | MetaCyc | EcoCyc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curation Basis | Expert-defined pathways | Literature-based experimental data [24] | Deep literature curation from 44,000+ publications [20] |

| Literature Citations | Limited or not provided [25] | Extensive with 76,283 citations [21] | Comprehensive with mini-review summaries [20] |

| Enzyme Properties | Basic EC number associations | Detailed kinetics, regulation, subunits [21] | Complete enzyme characterization with cofactors, inhibitors [20] |

| Pathway Variants | Combined representations | Separate variant pathways recorded [24] | Organism-specific pathway variants |

| Reaction Balancing | Contains unbalanced reactions | Fewer unbalanced reactions, better for metabolic modeling [18] | Stoichiometrically balanced for flux analysis |

| Taxonomic Range | Broad genomic mapping | Experimentally determined organisms per pathway [24] | Single organism focus with comparative tools |

Applications in Metabolic Pathway Optimization

Each database offers distinct advantages for specific research applications in metabolic pathway optimization:

- Genome Annotation and Pathway Prediction: MetaCyc's experimentally verified pathways provide higher-quality reference data for predicting metabolic networks from genomic data, while KEGG offers broader taxonomic coverage for comparative analysis [18] [21].

- Metabolic Engineering: MetaCyc and EcoCyc provide detailed enzyme information including substrate specificity, cofactors, and regulatory properties essential for selecting enzymes for pathway engineering [19] [20].

- Metabolic Modeling: MetaCyc contains fewer unbalanced reactions, facilitating metabolic modeling applications such as flux-balance analysis [18]. EcoCyc provides a validated quantitative metabolic model for E. coli [22].

- Metabolomics Research: MetaCyc's rich metabolite content with chemical structures and monoisotopic mass data supports metabolite identification from mass spectrometry experiments [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential computational tools and resources for metabolic pathway optimization research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Tools | Software Platform | Supports curation, visualization, and analysis of BioCyc databases including MetaCyc and EcoCyc [21] |

| KEGG API | Programming Interface | Enables computational access to KEGG data for automated retrieval and analysis [23] |

| BioCyc SmartTables | Data Analysis Tool | Enables creation, sharing, and analysis of sets of genes, metabolites, and pathways [19] |

| Cellular Omics Viewer | Visualization Tool | Paints omics data onto metabolic pathway maps for integrated data analysis [20] |

| Pathway Collages | Visualization Tool | Creates customizable multi-pathway diagrams for presenting research findings [19] |

| MetaFlux | Modeling Tool | Generates metabolic flux models from pathway databases for simulation and optimization [21] |

The selection of appropriate metabolic pathway databases depends significantly on the specific research objectives and required data quality. For pathway prediction and comparative genomics, KEGG offers the advantage of broad taxonomic coverage and established integration with genomic data. For metabolic engineering and pathway design, MetaCyc provides superior enzyme characterization and experimentally verified pathways that reduce errors in engineering decisions. For detailed organism-specific studies, particularly with E. coli, EcoCyc offers unprecedented depth of curated information including regulatory networks and gene essentiality data. The most robust research approach often involves using multiple databases complementarily, leveraging the strengths of each while compensating for their respective limitations. Future developments in metabolic pathway optimization would benefit from integrated approaches that combine KEGG's breadth with MetaCyc's curation quality and EcoCyc's depth of organism-specific knowledge.

Advanced Frameworks and AI Integration: Next-Generation Optimization Techniques

Metabolic network modeling is a cornerstone of systems biology, providing critical insights for drug discovery, microbial strain improvement, and understanding cellular functions [2] [3]. Among various computational approaches, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a principal tool for predicting metabolic flux distributions by optimizing a biological objective function, typically biomass maximization, under steady-state conditions [3] [26]. However, traditional FBA faces significant challenges in capturing flux variations under different environmental conditions and cellular states, largely due to its reliance on predefined objective functions that may not reflect actual cellular priorities [2] [27].

The emerging paradigm of topology-informed methods represents a significant advancement in the field by leveraging the inherent structural properties of metabolic networks. These approaches recognize that a reaction's position within the network architecture often provides more robust predictive power than functional simulations alone [26]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of topology-informed optimization methods, particularly the TIObjFind framework, against traditional and alternative approaches, evaluating their performance through experimental data and implementation protocols.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Optimization Methods

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Methods

Table 1 summarizes the performance characteristics of major metabolic pathway optimization methods based on experimental validations and case studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Metabolic Pathway Optimization Methods

| Method | Primary Approach | Prediction Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard FBA | Biomass yield maximization | Low sensitivity (misses many essential genes) [26] | High | Simple implementation; Fast computation [26] | Poor handling of biological redundancy; F1-Score: 0.000 for gene essentiality [26] |

| FBA with Molecular Crowding | Incorporates enzyme kinetics & crowding effects | Minimal improvement over standard FBA [27] | Moderate | Accounts for protein investment costs [27] | Fails to predict >66% of experimentally observed epistasis [27] |

| MOMA | Minimizes metabolic adjustment after perturbation | Recall: 2.8-4% for negative epistasis [27] | Moderate | Better for non-essential gene knockouts [27] | Low precision (6%) for epistasis prediction [27] |

| Topology-Based Machine Learning | Graph-theoretic features + Random Forest | F1-Score: 0.400 for gene essentiality [26] | High after training | Overcomes redundancy limitations [26] | Requires curated training data [26] |

| TIObjFind | MPA-FBA integration with Coefficients of Importance | High alignment with experimental flux data [2] | Moderate to High | Captures stage-specific metabolic objectives [2] | Requires experimental flux data for calibration [2] |

Specialized Capabilities and Applications

Table 2: Specialized Capabilities Across Optimization Methods

| Method | Condition-Specific Adaptation | Multi-Species System Support | Pathway Identification Strength | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard FBA | Limited without manual reconfiguration [3] | Limited | Weak | Poor correlation with experimental epistasis [27] |

| FBA with Molecular Crowding | Improved through enzyme constraints [27] | Not demonstrated | Moderate | Minimal improvement over FBA [27] |

| MOMA | Designed for perturbation conditions [27] | Not demonstrated | Moderate | Recall: 12.9% for positive epistasis [27] |

| Topology-Based Machine Learning | Built through training diversity [26] | Possible with appropriate training | Excellent structural insights [26] | Solid performance on E. coli core model [26] |

| TIObjFind | Excellent via Coefficients of Importance [2] | Demonstrated for multi-species IBE system [2] | Excellent through MPA integration [2] | Good match with observed experimental data [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

TIObjFind Implementation Workflow

The TIObjFind framework implements a structured three-stage methodology for identifying context-specific objective functions in metabolic networks [2] [3]. The workflow can be visualized as follows:

Stage 1: Optimization Problem Formulation The framework begins by reformulating objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted fluxes and experimental data while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal. Mathematically, this combines maximizing a weighted sum of fluxes (c·v) while minimizing the sum of squared deviations from experimental flux data [2]. This single-stage optimization uses a Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) formulation to evaluate candidate objectives.

Stage 2: Mass Flow Graph Construction FBA solutions are mapped onto a Mass Flow Graph where nodes represent metabolic reactions and directed edges represent metabolite flow between reactions. This graph-theoretic representation enables pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions and serves as the foundation for subsequent topological analysis [2].

Stage 3: Metabolic Pathway Analysis and Coefficient Calculation The framework applies a minimum-cut algorithm (typically Boykov-Kolmogorov for computational efficiency) to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance. These coefficients quantify each reaction's contribution to cellular objectives and serve as pathway-specific weights in optimization [2] [3].

Experimental Protocol for Method Validation

Case Study 1: Clostridium acetobutylicum Fermentation

- Objective: Determine pathway-specific weighting factors during glucose fermentation

- Implementation: TIObjFind was applied to assess the influence of Coefficients of Importance on flux predictions

- Validation Metrics: Prediction error reduction and improved alignment with experimental data [2]

Case Study 2: Multi-Species IBE System

- Objective: Assess cellular performance in a system comprising C. acetobutylicum and C. ljungdahlii

- Implementation: Coefficients of Importance were used as hypothesis coefficients within objective functions

- Validation Metrics: Match with observed experimental data and capture of stage-specific metabolic objectives [2]

Topology-Based Machine Learning Protocol

For comparative analysis, the experimental protocol for topology-based machine learning approach includes:

Network Representation

- Construct a directed reaction-reaction graph from metabolic models

- Filter out highly connected "currency metabolites" (H₂O, ATP, ADP, NAD, NADH) to focus on meaningful metabolic transformations [26]

Feature Engineering

- Calculate graph-theoretic metrics for each reaction node: Betweenness Centrality, PageRank, and Closeness Centrality

- Aggregate reaction-level metrics to gene level using gene-protein-reaction rules

- Create feature matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent topological features [26]

Model Training and Validation

- Implement RandomForestClassifier with balanced class weights to address dataset imbalance

- Train model on graph-theoretic features

- Validate against curated ground-truth essentiality data from experimental databases [26]

Technical Implementation and Research Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for TIObjFind Implementation

| Tool/Category | Specific Solution | Function/Role in Workflow | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Environment | MATLAB R2020b or newer | Primary computational framework | Custom code for main analysis [2] |

| Graph Algorithms | MATLAB maxflow package | Minimum cut set calculations | Uses Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm [2] |

| Visualization Tools | Python with pySankey package | Results visualization and pathway representation | Alternative to MATLAB visualization [2] |

| Metabolic Models | Organism-specific GEMs (e.g., iCAC802, iJL680) | Stoichiometric representation of metabolism | Required for FBA simulations [2] |

| Data Sources | KEGG, EcoCyc, ModelSEED | Pathway information and reaction databases | Foundational databases for network construction [3] |

| Code Availability | GitHub Repository | Custom scripts for TIObjFind implementation | Includes MATLAB and Python codes [3] |

Algorithmic Specifications for Pathway Analysis

The TIObjFind framework employs sophisticated graph algorithms for metabolic pathway analysis:

Minimum-Cut Algorithm Implementation

- Primary Algorithm: Boykov-Kolmogorov method selected for superior computational efficiency

- Performance: Delivers near-linear performance across various graph sizes

- Comparison: Significantly surpasses conventional algorithms (Ford-Fulkerson, Edmonds-Karp, Push-Relabel) [2]

Mass Flow Graph Construction

- Graph Type: Directed, weighted reaction graph

- Nodes: Metabolic reactions

- Edges: Metabolite flow between reactions with weights corresponding to flux values [2]

Performance Interpretation and Method Selection Guidelines

Decision Framework for Method Selection

The relationship between optimization approaches and their performance characteristics can be visualized as follows:

Key Performance Differentiators

TIObjFind Advantages

- Adaptive Objective Functions: Overcomes the fundamental limitation of static objective functions in traditional FBA by dynamically weighting reactions through Coefficients of Importance [2]

- Experimental Alignment: Demonstrates superior alignment with experimental flux data compared to FBA and MOMA approaches [2]

- Multi-Stage Modeling: Successfully captures metabolic adaptation throughout different biological stages, as evidenced in the IBE system case study [2]

Topology-Based Machine Learning Strengths

- Redundancy Resilience: Effectively handles biological redundancy that cripples traditional FBA, achieving F1-Score of 0.400 versus 0.000 for FBA in gene essentiality prediction [26]

- Architectural Focus: Leverages the primacy of network structure in determining biological function, providing more robust predictions [26]

Traditional FBA Limitations

- Redundancy Failure: Systematically fails to identify essential genes in redundant networks due to optimization-based flux rerouting [26]

- Epistasis Prediction: Poor performance in predicting experimentally observed epistasis, with molecular crowding modifications providing minimal improvement [27]

The comparative analysis demonstrates that topology-informed methods represent a significant advancement over traditional optimization approaches in metabolic modeling. TIObjFind specifically addresses critical limitations in standard FBA by integrating pathway topology with flux balance analysis through Coefficients of Importance, enabling more accurate prediction of cellular metabolic behavior under varying conditions.

For researchers selecting metabolic optimization methods, the key considerations should include: (1) availability of experimental flux data for calibration, (2) network complexity and redundancy, (3) need for condition-specific adaptation, and (4) computational resources. TIObjFind emerges as the superior approach for modeling complex, adaptive systems with available experimental data, while topology-based machine learning offers powerful alternatives for gene essentiality prediction, particularly when handling biological redundancy.

The integration of topological information with constraint-based modeling represents the future of metabolic network analysis, moving beyond single-objective optimization to capture the complex, multi-scale regulation of cellular metabolism.

The construction of high-fidelity Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) represents a cornerstone in systems biology, enabling the predictive understanding of cellular metabolism for applications ranging from biofuel production to drug development. This process has been fundamentally transformed by the integration of machine learning (ML) methodologies, which address two critical bottlenecks: the functional annotation of enzymes and the refinement of metabolic networks. Deep learning approaches have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in predicting Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers directly from amino acid sequences, with models like DeepECtransformer utilizing transformer layers to extract latent features from protein sequences for accurate enzyme function prediction [28]. Concurrently, tools like BoostGAPFILL leverage integrated constraint-based and pattern-based methods to identify and rectify gaps in metabolic network reconstructions with unprecedented fidelity [29]. This comparative analysis examines the performance, experimental protocols, and practical applications of these ML-driven tools, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on their specific GEM construction requirements.

DeepECtransformer: Architecture and Performance

Model Architecture and Methodology

DeepECtransformer employs a sophisticated neural network architecture that incorporates transformer layers specifically designed for EC number prediction. The model operates through a dual-engine approach: (1) a primary neural network that utilizes transformer architecture to extract latent features from enzyme amino acid sequences, and (2) a homologous search component that activates when the neural network provides no prediction [28]. This hybrid methodology ensures comprehensive coverage of enzyme functions.

The training protocol for DeepECtransformer utilized the UniProtKB/TrEMBL database containing approximately 22 million enzyme sequences covering 2,802 distinct EC numbers with complete four-digit classifications [28]. The model was trained to recognize sequence patterns corresponding to specific catalytic functions, with the transformer layers enabling the identification of functional motifs critical for enzymatic activity. For sequences where the neural network could not make predictions, the system defaults to homology-based assignment using UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot as the reference database, extending the tool's coverage to 5,360 EC numbers, including the EC:7 class (translocases) not covered in the original DeepEC implementation [28].

Performance Analysis and Experimental Validation

The performance of DeepECtransformer was rigorously evaluated against established benchmarks and alternative tools, demonstrating significant advancements in prediction accuracy.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Enzyme Function Prediction Tools

| Tool | Architecture | Precision Range | Recall Range | F1 Score Range | EC Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepECtransformer | Transformer layers + homology | 0.7589-0.9506 | 0.6830-0.9445 | 0.6990-0.9469 | 5,360 EC numbers |

| DeepEC | CNN-based | Lower than DeepECtransformer | Lower than DeepECtransformer | Lower than DeepECtransformer | Fewer than DeepECtransformer |

| DIAMOND | Homology-based | Slightly higher micro-precision | Comparable | Comparable | Database-dependent |

| MAPred | Multi-modal (sequence + 3Di) | Not specified | Not specified | Outperforms existing models | Not specified |

Performance evaluation revealed that DeepECtransformer achieved superior performance in terms of precision, recall, and F1 score compared to DeepEC and DIAMOND, with the exception of micro-precision where DIAMOND showed a slight advantage [28]. The model demonstrated particular strength in predicting EC numbers for enzymes with low sequence identities to those in the training dataset, addressing a critical limitation of homology-based methods [28].