Combinatorial Optimization in Synthetic Biology: From Machine Learning to Scalable Biomanufacturing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of combinatorial optimization strategies that are revolutionizing synthetic biology, enabling the systematic engineering of biological systems without requiring prior knowledge of optimal gene expression...

Combinatorial Optimization in Synthetic Biology: From Machine Learning to Scalable Biomanufacturing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of combinatorial optimization strategies that are revolutionizing synthetic biology, enabling the systematic engineering of biological systems without requiring prior knowledge of optimal gene expression levels. It explores the foundational shift from sequential to multivariate optimization approaches, details cutting-edge methodologies including machine learning-driven tools like the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) and advanced genome editing. The content addresses critical troubleshooting challenges in scaling bioprocesses and validates these approaches through comparative case studies in metabolic engineering. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how these strategies accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle for developing therapeutic compounds, sustainable biomaterials, and efficient microbial cell factories.

The Combinatorial Optimization Landscape: Why Multivariate Strategies Are Revolutionizing Bioengineering

Synthetic biology is undergoing a fundamental transformation, evolving from engineering simple genetic circuits toward programming complex, systems-level functions. This evolution has been driven by a critical recognition: our limited knowledge of optimal component combinations often impedes efforts to construct complex biological systems [1]. Combinatorial optimization has emerged as a pivotal strategy to address this challenge, enabling multivariate optimization without requiring prior knowledge of ideal expression levels for individual genetic elements [1] [2]. This approach allows synthetic biologists to rapidly explore vast design spaces and identify optimal configurations that maximize desired functions, from metabolic pathway efficiency to therapeutic protein production.

The field has progressed through distinct waves of innovation. The first wave focused on combining genetic elements into simple circuits to control individual cellular functions. The second wave, which we are currently experiencing, involves combining these simple circuits into complex networks that perform sophisticated, systems-level operations [1]. This transition has been facilitated by advances in DNA synthesis, sequencing technologies, and computational tools that together enable the design, construction, and testing of increasingly complex biological systems [3].

Combinatorial Optimization: Core Concepts and Strategic Importance

Combinatorial optimization represents a fundamental departure from traditional sequential optimization methods in synthetic biology. Where sequential approaches test one part or a small number of parts at a time—making the process time-consuming and often successful only through trial-and-error—combinatorial methods enable the simultaneous testing of numerous combinations [1]. This paradigm shift is particularly valuable in metabolic engineering, where a fundamental question is determining the optimal enzyme levels for maximizing output [1].

The power of combinatorial optimization lies in its ability to address the multivariate nature of biological systems. When engineering microorganisms for industrial-scale production, multiple genes must be introduced and expressed at appropriate levels to achieve optimal output. Due to the enormous complexity of living cells, it is typically unknown at which level heterologous genes should be expressed, or to which level the expression of host-endogenous genes should be altered [1]. Combinatorial approaches allow researchers to navigate this complexity systematically by generating diverse genetic constructs and screening for high-performing combinations.

Table 1: Comparison of Optimization Strategies in Synthetic Biology

| Strategy | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Optimization | One part or small number of parts tested at a time | Simple implementation; Easy to track changes | Time-consuming; Expensive; Often requires trial-and-error |

| Combinatorial Optimization | Multiple components tested simultaneously in diverse combinations | Rapid exploration of design space; No prior knowledge of optimal combinations required | Requires high-throughput screening methods; Complex data analysis |

| Model-Guided Optimization | Computational prediction of optimal configurations | Reduces experimental burden; Provides mechanistic insights | Limited by model accuracy; Difficult for complex systems |

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Platforms

The COMPASS Platform for Pathway Optimization

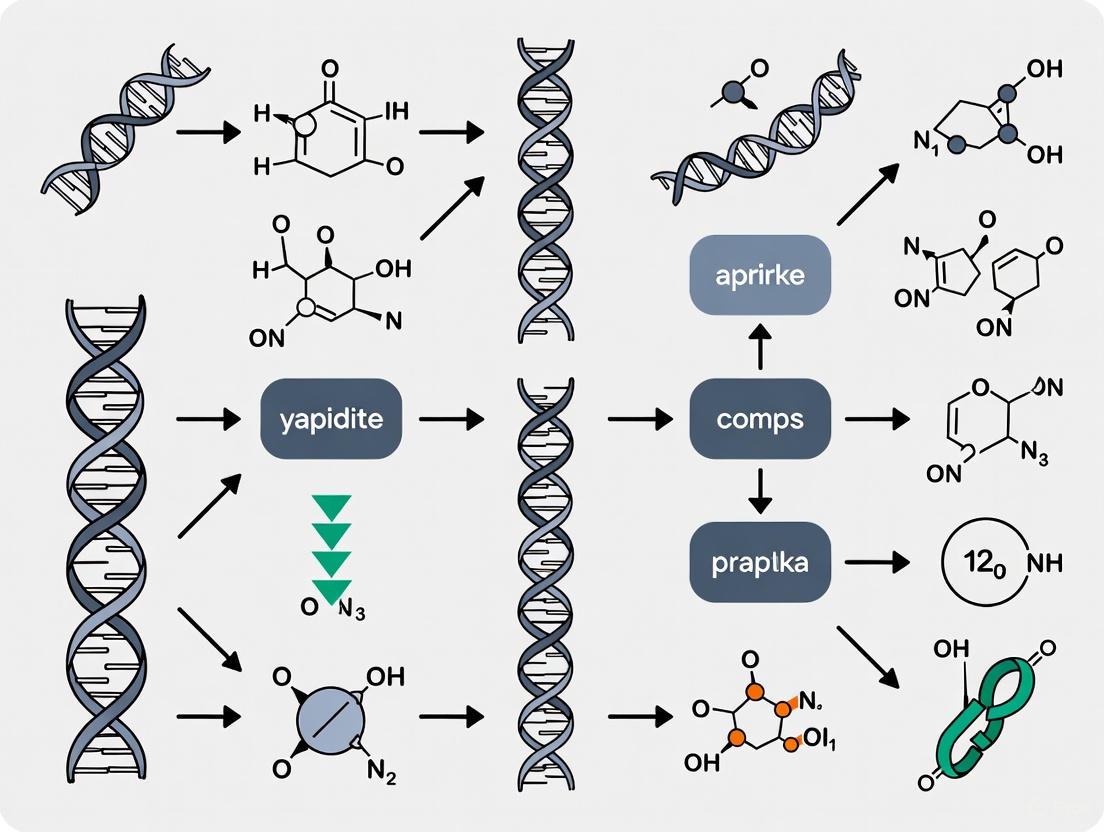

The COMbinatorial Pathway ASSembly (COMPASS) system exemplifies the application of combinatorial optimization to biochemical pathway engineering in yeast [4]. This high-throughput cloning method enables researchers to balance the expression of heterologous genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by building tens to thousands of different plasmids in a single cloning reaction tube [4]. COMPASS utilizes nine inducible artificial transcription factors and corresponding binding sites (ATF/BSs) covering a wide range of expression levels, creating libraries of stable yeast isolates with millions of different parts combinations through just four cloning reactions [4].

The COMPASS workflow operates through three cloning levels (0, 1, and 2) and employs a positive selection scheme for both in vivo and in vitro cloning procedures. The system integrates a multi-locus CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing tool to reduce turnaround time for genomic manipulations [4]. This platform demonstrates how combinatorial optimization, when coupled with advanced genome editing, can accelerate the engineering of microbial cell factories for bio-production.

Diagram 1: COMPASS workflow for combinatorial optimization of biochemical pathways

Protocol: Combinatorial Library Generation and Screening

Objective: Generate a diverse combinatorial library of genetic constructs and identify optimal configurations for maximal metabolic output.

Materials:

- Host organism (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Escherichia coli)

- Library of genetic regulators (promoters, ribosome binding sites, terminators)

- Assembly system (e.g., VEGAS, COMPASS-compatible vectors)

- CRISPR/Cas9 components for genomic integration

- Metabolic biosensors for product detection

- Flow cytometry equipment for high-throughput screening

- Selection markers (antibiotic resistance, auxotrophic markers)

Procedure:

Library Design and Assembly:

- Select diverse regulatory elements (promoters, RBS, terminators) covering a wide range of expression strengths

- Design homology regions between adjacent assembly fragments and plasmid backbones

- Perform one-pot assembly reactions to generate diverse constructs in single cloning reactions

- Transform assembled constructs into appropriate host organisms

Combinatorial Library Construction:

- Utilize multi-locus integration strategies to generate libraries with millions of combinations

- Apply positive selection schemes using bacterial and yeast selection markers

- Verify correct assemblies through sequence validation and functional tests

High-Throughput Screening:

- Employ genetically encoded whole-cell biosensors to transduce chemical production into detectable signals

- Use laser-based flow cytometry to identify high-producing strains based on fluorescence

- Isplicate promising candidates for further validation and characterization

Validation and Scale-up:

- Validate top-performing strains in small-scale bioreactors

- Analyze metabolic fluxes and potential bottlenecks

- Iterate design based on performance data for further optimization

This protocol enables the rapid generation of combinatorial diversity and identification of optimal strain configurations without prior knowledge of ideal expression levels [1] [4].

Applications Across Biological Scales

Expanding to Microbial Community Engineering

The principles of combinatorial optimization are now being extended beyond single organisms to microbial communities, giving rise to the field of synthetic ecology [5]. This approach recognizes that microbial communities can carry out functions of biotechnological interest more effectively than single strains, with benefits including natural compartmentalization of functions (division of labor), reduced fitness costs on individual strains, and enhanced robustness [5].

Synthetic ecology employs both bottom-up and top-down strategies for community optimization. Bottom-up approaches involve assembling defined sets of species into consortia based on known traits, while top-down approaches manipulate existing communities through rational interventions [5]. These strategies mirror the evolution of combinatorial approaches from individual components to complex systems.

Table 2: Combinatorial Optimization Applications Across Biological Scales

| Scale | Optimization Target | Key Technologies | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Circuits | Expression levels of individual genes | Regulatory element libraries, Biosensors | Logic gates, Oscillators, Recorders [1] |

| Metabolic Pathways | Flux through multi-enzyme pathways | COMPASS, MAGE, VEGAS | Biofuel production, High-value chemicals [1] [4] |

| Microbial Communities | Species composition and interactions | Directed evolution, Environmental manipulation | Waste degradation, Biomaterial synthesis [5] |

Data Analysis and Machine Learning in Combinatorial Optimization

The successful implementation of combinatorial optimization relies heavily on advanced data analysis and machine learning approaches [6]. The complexity and size of datasets generated by combinatorial libraries necessitate sophisticated computational tools for extracting meaningful patterns and predicting optimal configurations.

Key data analysis challenges in combinatorial optimization include:

- Data Integration: Combining diverse data types from genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics

- Data Complexity: Handling large, high-dimensional datasets generated by high-throughput technologies

- Model Development: Creating robust, interpretable models that predict biological system behavior

- Interpretability: Translating computational results into biologically meaningful insights [6]

Machine learning algorithms have demonstrated particular utility in combinatorial optimization projects. Random Forest algorithms can predict gene expression based on regulatory elements, Support Vector Machines enable classification of biological samples, and Convolutional Neural Networks facilitate analysis of complex genomic data [6]. These tools help navigate the vast design spaces explored by combinatorial approaches.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Combinatorial Optimization

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Transcription Factors (ATFs) | Orthogonal regulation of gene expression | Tuning expression levels in COMPASS system [4] |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Systems | Precise genome editing and regulation | Multi-locus integration of genetic circuits [4] |

| Metabolic Biosensors | Detection of metabolite production | High-throughput screening of combinatorial libraries [1] |

| Advanced Orthogonal Regulators | Controlled gene expression without host interference | Light-inducible systems, Quorum sensing systems [1] |

| Barcoding Tools | Tracking library diversity | Monitoring population dynamics in complex libraries [1] |

Visualizing Complex Systems and Workflows

Diagram 2: Iterative combinatorial optimization cycle for synthetic biology

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The evolution of synthetic biology from simple circuits to complex systems represents a fundamental shift in how we approach biological engineering. Combinatorial optimization methods have emerged as essential tools for navigating the complexity of biological systems, enabling researchers to explore vast design spaces without complete prior knowledge of optimal configurations [1]. As the field advances, several areas present particularly promising directions for future development.

First, the integration of biological large language models (BioLLMs) trained on natural DNA, RNA, and protein sequences offers new opportunities for generating biologically significant sequences as starting points for designing useful proteins [3]. Second, the expansion of combinatorial approaches from single organisms to microbial communities opens possibilities for engineering complex ecosystem functions [5]. Finally, advances in DNA synthesis technologies and automated strain construction will further accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycles that underpin combinatorial optimization [3].

The continued development and application of combinatorial optimization strategies will be crucial for realizing the full potential of synthetic biology in addressing global challenges in health, energy, and sustainability. By embracing complexity and developing tools to navigate it systematically, synthetic biologists are building the foundation for a new generation of biological technologies that transcend the capabilities of simple genetic circuits.

Combinatorial optimization provides a powerful, systematic framework for biological design, moving the field beyond inefficient trial-and-error approaches. In synthetic biology, researchers increasingly deal with multivariate problems where the optimal combination of genetic elements—such as promoters, coding sequences, and ribosome binding sites—is not known in advance. Combinatorial optimization addresses this challenge by allowing the simultaneous testing of numerous combinations to identify optimal configurations without requiring prior knowledge of the system's precise design rules [7]. This represents a fundamental shift from traditional sequential optimization methods, where only one or a few parts are modified at a time, making the approach time-consuming and often unsuccessful for complex biological systems [7] [2].

The mathematical foundation of combinatorial optimization problems (COPs) involves finding an optimal solution from a finite set of discrete possibilities. Formally, these problems can be represented as minimizing or maximizing an objective function c(x) subject to constraints that define a set of feasible solutions [8]. In biological contexts, the objective function might represent metabolic flux, protein production, or growth yield, while constraints could include cellular resource limitations or kinetic parameters. This approach is particularly valuable because many biological optimization problems belong to the NP-Hard class, requiring sophisticated computational strategies rather than exhaustive search methods [8].

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Core Principles and Definitions

Combinatorial optimization in synthetic biology, often termed "multivariate optimization," enables the rapid generation of diverse genetic constructs to explore a vast biological design space [7]. This methodology recognizes that tweaking multiple factors is typically critical for obtaining optimal output in biological systems, including transcriptional regulator strength, ribosome binding sites, enzyme properties, host genetic background, and expression systems [7]. Unlike trial-and-error approaches that involve attempting various solutions with limited systematic guidance [9], combinatorial optimization employs structured experimental design and high-throughput screening to efficiently navigate complex biological landscapes.

Experimental Workflow for Combinatorial Library Generation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for constructing and screening combinatorial libraries in synthetic biology:

Diagram 1: Combinatorial Optimization Workflow in Synthetic Biology

The workflow begins with in vitro construction and in vivo amplification of combinatorially assembled DNA fragments to generate gene modules [7]. Each module contains genes whose expression is controlled by a library of regulators. Advanced genome-editing tools, particularly CRISPR/Cas-based strategies, enable multi-locus integration of multiple module groups into different genomic locations across microbial cell populations [7]. This process generates extensive combinatorial libraries where each member represents a unique genetic configuration. Sequential cloning rounds facilitate construction of entire pathways in plasmids, which can be transformed into hosts or integrated into microbial genomes [7].

Advanced Orthogonal Regulators for Combinatorial Control

A critical enabling technology for combinatorial optimization in biology is the development of advanced orthogonal regulators that provide precise control over genetic expression. Unlike constitutive promoters that often impose metabolic burden, sophisticated regulation systems include:

- Auto-inducible protein expression systems that utilize cell density-based control modules to tightly regulate transcription timing [7]

- Small RNAs that control gene expression through RNA-DNA or RNA-RNA interactions at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels [7]

- Orthogonal artificial transcription factors (ATFs) developed using DNA binding domains from zinc finger proteins, transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs), and CRISPR/dCas9 scaffolds [7]

- Light-inducible (optogenetic) systems that enable precise temporal control of gene expression through light pulses [7]

- Chemical-inducible systems using cost-effective inducers that modulate protein levels in response to defined input signals [7]

These regulatory tools enable the creation of complex genetic circuits where multiple components can be independently controlled, substantially expanding the accessible design space for biological optimization.

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Analysis of Combinatorial Optimization Results

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optimization Methods in Metabolic Engineering

| Optimization Method | Number of Variables Tested | Screening Throughput | Time Requirement | Success Rate | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Optimization | 1-2 variables simultaneously | Low | Months to years | Low (highly dependent on prior knowledge) | Simple pathway optimization, single gene edits |

| Classical Trial-and-Error | Limited by experimental design | Very low | Highly variable | Very low (often serendipitous) | Proof-of-concept studies, basic characterization |

| Combinatorial Optimization | Dozens to hundreds simultaneously | High (library-based) | Weeks to months | Moderate to high (systematic exploration) | Complex pathway engineering, multi-gene circuits |

| MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering) | Multiple genomic locations | Medium | Weeks | Moderate | Genomic diversity generation, metabolic engineering |

| COMPASS & VEGAS Methods | Multiple modules with regulatory variants | Very high | 2-4 weeks | High | Metabolic pathway optimization, complex circuit design |

Combinatorial optimization strategies significantly outperform traditional methods in both throughput and efficiency. While sequential optimization examines only one or a few variables at a time, making the approach time-consuming and often unsuccessful for complex systems [7], combinatorial methods enable simultaneous testing of numerous genetic combinations. For example, one study designed 244,000 synthetic DNA sequences to uncover translation optimization principles in E. coli [7], a scale unimaginable with traditional approaches. The trial-and-error method, characterized by attempting various solutions with limited systematic guidance [9], proves particularly inefficient for biological systems where the relationship between genetic composition and functional output is complex and nonlinear.

Combinatorial Optimization in Published Studies

Table 2: Applications of Combinatorial Optimization Across Biological Domains

| Biological System | Optimization Target | Combinatorial Approach | Library Size | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli metabolic pathways | Metabolite production | COMPASS, VEGAS | 10^3 - 10^5 variants | 2-10 fold increase over wild type |

| S. cerevisiae synthetic circuits | Heterologous protein expression | Artificial Transcription Factors | 10^2 - 10^3 variants | Up to 10-fold stronger than TDH3 promoter |

| Eukaryotic transcriptional regulation | Logic gates, oscillators | Combinatorial promoter engineering | 10^2 - 10^4 combinations | Successful implementation of complex functions |

| Microbial consortia | Division of labor, cross-feeding | Modular coculture engineering | 10^1 - 10^2 strains | Enhanced stability and productivity |

| Riboswitch-based sensors | Ligand sensitivity, dynamic range | Combinatorial sequence space exploration | 10^4 - 10^5 variants | Improved detection thresholds and specificity |

The application of combinatorial optimization has led to remarkable successes across diverse biological systems. In metabolic engineering projects, the fundamental question is typically the optimal enzyme expression level for maximizing output [7]. Combinatorial approaches address this by automatically exploring the expression landscape without requiring prior knowledge of optimal combinations [2]. This methodology has proven particularly valuable for engineering microorganisms for industrial-scale production, where introducing multiple genes and optimizing their expression levels remains challenging despite extensive background knowledge [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Research Tools for Combinatorial Optimization

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Combinatorial Optimization Experiments

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Combinatorial Optimization | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly Systems | Golden Gate Assembly, Gibson Assembly, VEGAS | Combinatorial construction of genetic variants | Assembly efficiency, standardization, modularity |

| Regulatory Parts | Promoter libraries, RBS variants, terminators | Generating expression level diversity | Orthogonality, strength range, compatibility |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas systems, MAGE, recombinase systems | Multiplex genomic integration and modification | Efficiency, specificity, throughput |

| Screening Technologies | Biosensors, FACS, barcoding systems | High-throughput identification of optimal variants | Sensitivity, dynamic range, scalability |

| Analytical Tools | NGS, LC-MS, RNA-seq, machine learning algorithms | Data generation and analysis for optimization | Throughput, cost, computational requirements |

The successful implementation of combinatorial optimization requires integrated toolkits that span from DNA construction to analysis. Advanced orthogonal regulators enable precise control over genetic elements, with CRISPR/dCas9 systems particularly valuable for their programmability and specificity [7]. Barcoding tools facilitate tracking of library diversity, allowing researchers to connect genotype to phenotype at scale [7]. Genetically encoded biosensors combined with flow cytometry technologies enable high-throughput screening by transducing chemical production into detectable fluorescence signals [7]. These reagents collectively form the foundation for effective combinatorial optimization in biological systems.

Advanced Protocols and Implementation

Detailed Protocol: COMPASS Workflow for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

The Combinatorial Pathway Optimization (COMPASS) protocol provides a robust methodology for optimizing metabolic pathways in microbial hosts. The following diagram details the experimental workflow:

Diagram 2: COMPASS Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Design Module Libraries

- Select diverse regulatory parts (promoters, RBS) with varying strengths

- Include coding sequence variants (CDS) with different codon optimization schemes

- Design homology arms for subsequent assembly steps

- Critical consideration: Ensure part orthogonality to minimize unintended interactions

Step 2: In Vitro Assembly

- Perform Golden Gate or Gibson assembly with standardized parts

- Use modular vector systems compatible with downstream steps

- Transform into intermediate host for sequence verification

- Quality control: Verify assembly success through diagnostic restriction digest and Sanger sequencing

Step 3: VEGAS (Vector Editing for Genomic Assembly)

- Employ yeast homologous recombination for pathway assembly

- Utilize shuttle vectors that replicate in both yeast and target host

- Assemble complete metabolic pathways in programmable vectors

- Throughput optimization: Implement robotic automation for handling large variant numbers

Step 4: CRISPR/Cas-mediated Integration

- Design sgRNAs targeting specific genomic loci

- Prepare repair templates with integrated pathway variants

- Transform CRISPR components and repair templates simultaneously

- Efficiency enhancement: Use counter-selection markers to enrich for correct integrations

Step 5: Library Expansion and Barcoding

- Grow library under selective conditions

- Incorporate unique molecular barcodes during library construction

- Prepare samples for high-throughput screening

- Library quality assessment: Use NGS to verify library diversity and representation

Step 6: Biosensor-based FACS Screening

- Employ metabolite-responsive biosensors linked to fluorescent reporters

- Perform fluorescence-activated cell sorting to isolate high producers

- Collect multiple rounds of enriched populations

- Sensitivity optimization: Titrate biosensor response using known metabolite standards

Step 7: NGS Analysis and Hit Validation

- Sequence barcodes from sorted populations to identify enriched variants

- Reconstruct top-performing strains from individual clones

- Validate performance in small-scale cultures

- Statistical rigor: Include biological replicates and appropriate controls

Step 8: Machine Learning Model Refinement

- Train predictive models on sequencing and screening data

- Identify sequence-function relationships guiding optimization

- Inform design of subsequent library iterations

- Model validation: Use holdout test sets to evaluate prediction accuracy

This comprehensive protocol enables researchers to systematically explore vast genetic design spaces, moving beyond the limitations of trial-and-error approaches that often struggle with biological complexity [9]. The integration of computational design, high-throughput construction, and intelligent screening represents the cutting edge of biological engineering.

Combinatorial optimization represents a paradigm shift in biological engineering, providing systematic methodologies that transcend traditional trial-and-error approaches. By embracing complexity and employing sophisticated design-build-test-learn cycles, researchers can navigate biological design spaces with unprecedented efficiency and scale. The integration of advanced genome editing tools, orthogonal regulatory systems, biosensor technologies, and machine learning creates a powerful framework for biological optimization that will continue to accelerate innovation in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering.

As these methodologies mature, we anticipate further improvements in automation, computational prediction, and design rule elaboration. The future of combinatorial optimization in biology lies in the seamless integration of experimental and computational approaches, enabling increasingly sophisticated biological engineering with applications spanning therapeutics, sustainable manufacturing, and fundamental biological discovery.

Synthetic biology aims to apply engineering principles to design and construct new biological systems. However, this endeavor faces a fundamental computational challenge: the problem of biological design is often NP-hard, meaning the computational resources required to find optimal solutions grow exponentially with the number of variables in the system [10]. This exponential scaling presents a significant barrier to engineering complex biological systems with many interacting components.

The core issue stems from the combinatorial nature of biological design spaces. Whether engineering proteins, genetic circuits, or metabolic pathways, researchers must search through an astronomically large number of possible variants to find optimal designs. For a protein of just 50 amino acids, the number of possible variants with 10 substitutions exceeds 10¹², making exhaustive experimental testing impossible [10]. This article explores the manifestations of this NP-hard problem in synthetic biology and provides frameworks for developing feasible experimental protocols.

The Exponential Scaling Problem in Biological Systems

Quantitative Landscape of Combinatorial Explosion

The following table illustrates how sequence variants scale exponentially with problem size across different biological engineering contexts:

Table 1: Examples of Exponential Scaling in Biological Design Problems

| Biological Context | Number of Variables | Number of Possible Variants | Experimental Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Engineering (300 amino acids, 3 substitutions) | 3 | ~30 billion | Intractable |

| DNA Aptamer (30-mer) | 30 | ~1 × 10¹⁸ | Impossible |

| Metabolic Engineering (1000 enzymes, select 3) | 3 | ~166 million | Intractable |

| Genetic Circuit (10 parts) | 10 | >1 million | Partially tractable with screening |

This exponential relationship means that for most problems of practical interest, the search space is so vast that exhaustive exploration is impossible within meaningful timeframes [10]. The scaling challenge is further compounded by the ruggedness of biological fitness landscapes, where small changes can lead to dramatically different outcomes due to epistatic interactions between components [10].

NP-Hard Nature of Protein and Metabolic Design

Protein engineering exemplifies the NP-hard challenge. The number of sequence variants for M substitutions in a protein of N amino acids is given by the combinatorial formula: 20^M × C(N,M). For even moderately sized proteins, this creates search spaces that cannot be fully explored experimentally [10]. Similarly, in metabolic engineering, selecting the optimal combination of k enzymes out of n total possibilities generates combinatorial complexity that becomes intractable for k > 3 [10].

Computational Frameworks and Tools

Heuristic Approaches for NP-Hard Biological Problems

Since biological design problems are NP-hard and cannot be solved exactly in reasonable time for practical applications, researchers employ heuristic approaches that find good, but not provably optimal, solutions [10]. These include:

Evolutionary Algorithms: Methods that maintain a population of candidate solutions and use selection, recombination, and mutation to evolve toward improved solutions over generations [10] [11].

Active Learning: Algorithms that use existing knowledge to select the most informative next experiments, thereby reducing the total experimental burden [10].

Parallel Genetic Algorithms: implementations that distribute the computational workload across multiple processors or GPUs, significantly reducing computation time for large problems [11].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Biological Design Optimization

| Method | Key Features | Applicability | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithms | Population-based, inspired by natural evolution | Protein engineering, genetic circuit design | May converge to local optima |

| Linear Programming (LP) | Efficient for convex problems with linear constraints | Metabolic flux balance analysis | Limited to linear systems |

| Integer Programming | Handles discrete decision variables | Combinatorial mutagenesis library design | Computationally intensive for large problems |

| Bayesian Optimization | Builds probabilistic model of landscape | Resource-intensive experimental optimization | Performance depends on surrogate model |

Optimization of Combinatorial Mutagenesis

The OCoM (Optimization of Combinatorial Mutagenesis) approach addresses the NP-hard challenge in protein engineering by selecting optimal positions and corresponding sets of mutations for constructing mutagenesis libraries [12]. This method:

- Evaluates library quality using one- and two-body sequence potentials averaged over variants

- Balances library quality with explicit evaluation of novelty

- Uses dynamic programming for one-body cases and integer programming for two-body cases

- Enabled design of 18 mutations generating 10^7 variants of a 443-residue P450 in just 1 hour [12]

Experimental Protocols for Managing Complexity

Protocol: Designing Combinatorial Mutagenesis Libraries

Objective: Create a optimized combinatorial mutagenesis library that maximizes the probability of discovering variants with improved properties while managing experimental complexity.

Materials:

- Target gene or protein sequence

- Structural and functional data (if available)

- OCoM software or equivalent optimization tool

- Library construction materials (PCR reagents, primers, etc.)

- High-throughput screening capability

Procedure:

Input Preparation (Day 1)

- Gather all available structural and functional information about the target protein

- Identify constraints based on experimental capabilities (library size, screening capacity)

- Define objective function based on desired properties (stability, activity, etc.)

Position Selection (Day 1)

- Use computational tools to identify candidate positions for mutagenesis

- Consider evolutionary conservation, structural data, and known functional regions

- Balance between exploring variable and conserved regions

Library Optimization (Day 2)

- Input candidate positions into optimization algorithm (e.g., OCoM)

- Set parameters to balance quality and novelty of library members

- Run optimization to select optimal mutation combinations

- Evaluate trade-offs between library size and quality

Library Construction (Days 3-5)

- Design degenerate oligonucleotides based on optimization results

- Perform library construction using appropriate method (e.g., PCR mutagenesis)

- Clone library into expression vector

- Transform into host organism

Screening and Validation (Days 6-10)

- Implement high-throughput screening for desired properties

- Isolate and characterize hits

- Sequence variants to confirm mutations

- Use results to inform subsequent library designs

Troubleshooting:

- If library quality is poor, adjust balance between quality and novelty in optimization

- If library size is unmanageable, increase stringency of position selection

- If screening yields no hits, consider expanding diversity or adjusting selection criteria

Protocol: Heuristic Optimization of Metabolic Pathways

Objective: Engineer metabolic pathways for improved production of target compounds using heuristic optimization to navigate combinatorial complexity.

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model

- Gene editing tools (CRISPR, MAGE, etc.)

- Analytics for target compound quantification

- Optimization software

Procedure:

Problem Formulation (Day 1)

- Define objective function (e.g., maximize product yield, minimize byproducts)

- Identify decision variables (enzyme variants, expression levels, knockouts)

- Define constraints (growth requirements, resource limitations)

Initial Design (Day 2)

- Use constraint-based modeling (e.g., FBA) to identify promising targets

- Apply design principles (e.g., eliminate competing pathways, enhance flux)

- Select initial set of modifications for testing

Iterative Optimization (Days 3-15)

- Implement first-round modifications using appropriate gene editing tools

- Measure performance against objective function

- Use heuristic algorithm (e.g., evolutionary algorithm) to select next round of modifications

- Repeat implementation and measurement through multiple cycles

Validation (Days 16-20)

- Characterize optimized strain under production conditions

- Evaluate stability and robustness of improvements

- Perform omics analyses to understand systemic effects

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Combinatorial Optimization in Synthetic Biology

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Precision gene editing | Targeted mutations, gene knockouts, regulatory element engineering |

| Oligonucleotide Libraries | Source of diversity | Combinatorial mutagenesis, degenerate codon libraries |

| DNA Synthesis Platforms | de novo DNA construction | Synthetic gene circuit assembly, pathway engineering |

| Cell-Free Systems | Rapid prototyping | Testing genetic parts, pathway validation without cellular context |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Quantitative measurements | Promoter strength quantification, circuit performance characterization |

| High-Throughput Screening | Functional assessment | Identifying improved variants from large libraries |

| Genome-Scale Models | In silico prediction | Metabolic flux prediction, identification of engineering targets |

The NP-hard nature of biological design presents both a fundamental challenge and an opportunity for developing innovative solutions in synthetic biology. By recognizing that biological design problems are combinatorial optimization problems, researchers can leverage powerful computational frameworks to navigate exponentially large search spaces. The protocols and frameworks presented here provide practical approaches for managing this complexity while accelerating the engineering of biological systems with desired functions. As synthetic biology continues to mature, further development of optimization methods specifically tailored to biological complexity will be essential for realizing the full potential of this field.

The fitness landscape, a concept nearly a century old, provides a powerful metaphor for understanding evolution by representing genotypes as locations and their reproductive success as elevation [13]. Navigating these landscapes is a central challenge in synthetic biology, where the goal is to engineer biological systems with desired functions. The ruggedness of a landscape—characterized by multiple peaks, valleys, and plateaus—is primarily determined by epistasis, the phenomenon where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of other mutations [14] [15]. Understanding and quantifying this ruggedness is critical for applications ranging from optimizing protein engineering to predicting the evolution of antibiotic resistance. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for analyzing fitness landscape topography, with a specific focus on its implications for combinatorial optimization in synthetic biology research and drug development.

Quantitative Characterization of Fitness Landscape Topography

The topography of a fitness landscape can be quantitatively described by a set of features that capture its key characteristics. These features are essential for comparing landscapes, interpreting model performance, and understanding evolutionary constraints. The following table summarizes core topographic features, categorized by four fundamental aspects.

Table 1: Core Topographic Features of Fitness Landscapes

| Topographic Aspect | Feature Name | Quantitative Description | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruggedness | Number of Local Optima | Count of genotypes fitter than all immediate mutational neighbors | Induces evolutionary trapping; hinders convergence to global optimum [13] |

| Roughness/Slope Variance | Variance in fitness differences between neighboring genotypes | Measures local variability and predictability of mutational effects [13] | |

| Epistasis | Fraction of Variance from Epistasis | Proportion of total fitness variance explained by non-additive interactions | Quantifies deviation from a simple, additive model of mutations [15] |

| Epistatic Interaction Order | Highest order of significant epistatic interactions (e.g., 2-way, 3-way) | Reveals complexity of genetic interactions shaping the landscape [15] | |

| Navigability | Accessibility of Global Optimum | Number of monotonically increasing paths from wild-type to global optimum | Predicts the number of viable evolutionary trajectories [13] |

| Fitness Distance Correlation | Correlation between fitness of a genotype and its mutational distance to the global optimum | Measures the "guidance" available for evolutionary search [13] | |

| Neutrality | Neutral Network Size | Number of genotypes connected in a network with identical fitness | Impacts evolutionary exploration and genetic diversity [13] |

| Mutation Robustness | Average fraction of neutral mutations per genotype | Resistance to fitness loss upon random mutation [13] |

Tools like GraphFLA, a Python framework, can compute these and other features from empirical sequence-fitness data, enabling the systematic comparison of thousands of landscapes from benchmarks like ProteinGym and RNAGym [13].

Application Note: Inferring Landscape Topography for Model Interpretation

Background: Machine learning (ML) models are increasingly used to predict fitness from sequence, yet their performance varies significantly across different tasks. Landscape topography features provide the biological context needed to interpret this performance.

Observation: A model might achieve high prediction accuracy ((R^2 > 0.8)) on a protein stability landscape but perform poorly ((R^2 < 0.4)) on an antigen-binding landscape. Average performance metrics obscure these differences.

Analysis using Topographic Features: Applying GraphFLA to the benchmark tasks reveals that the stable protein landscape is likely smoother (lower ruggedness, weaker epistasis) and more navigable (higher fitness-distance correlation). In contrast, the binding landscape is highly rugged and epistatic, making it inherently harder for ML models to learn [13]. The Epistatic Net (EN) method directly incorporates the prior knowledge that epistatic interactions are sparse, regularizing deep neural networks to improve their accuracy and generalization on such rugged landscapes [15].

Conclusion for Combinatorial Optimization: When planning an ML-guided directed evolution campaign, an initial pilot study to characterize the landscape's topography can inform the choice of prediction model. For rugged, highly epistatic landscapes, models with built-in sparse epistatic regularization, such as EN, are preferable [15].

Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing and Analyzing an Empirical Fitness Landscape with GraphFLA

This protocol details the steps for generating a fitness landscape from deep mutational scanning (DMS) data and calculating its topographic features using the GraphFLA framework [13].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for Fitness Landscape Construction

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type DNA Sequence | Template for generating variant library. | Plasmid DNA, >95% purity. |

| Mutagenesis Kit | Generation of a comprehensive variant library. | Commercial kit for site-saturation or combinatorial mutagenesis. |

| Selection or Assay System | Linking genotype to fitness or function. | Growth-based selection, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), binding assay. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform | Quantifying variant abundance pre- and post-selection. | Illumina, PacBio. |

| GraphFLA Python Package | End-to-end framework for constructing landscapes and calculating topographic features. | https://github.com/COLA-Laboratory/GraphFLA [13] |

| Sequence-Fitness Data File | Input for GraphFLA. | CSV file with columns: variant_sequence, fitness_score. |

II. Experimental Workflow

III. Step-by-Step Procedures

Generate Variant Library & Conduct Assay:

- Using the wild-type DNA sequence, create a library of mutants. The library can be generated via random mutagenesis or, for more systematic studies, by synthesizing all possible combinations within a defined sequence space [13] [14].

- Subject the library to a high-throughput functional assay (e.g., for enzyme activity, binding affinity, or antibiotic resistance) that provides a quantitative fitness readout [14].

Sequence and Quantify:

- Use NGS to sequence the variant library both before and after the functional assay.

- For each variant ( i ), calculate its fitness ( Fi ) using the formula: [ Fi = \log2\left(\frac{\text{Count}{i, \text{post-selection}} / \text{Total}{\text{post-selection}}}{\text{Count}{i, \text{pre-selection}} / \text{Total}_{\text{pre-selection}}}\right) ]

- Compile a CSV file with two columns:

variant_sequenceandfitness_score.

GraphFLA Analysis:

- Install GraphFLA:

pip install graphfla(Check repository for latest instructions). - Use the following Python code to load your data and compute landscape features:

- Install GraphFLA:

Protocol 2: Regularizing Deep Learning Models with Epistatic Net (EN)

This protocol describes how to apply the Epistatic Net (EN) regularization method to train deep neural networks (DNNs) for fitness prediction, leveraging the sparsity of epistatic interactions as an inductive bias [15].

I. Workflow for Sparse Spectral Regularization

II. Step-by-Step Computational Procedures

Data Preparation and Model Definition:

- Format your data into a training set ( { (xi, yi) } ), where ( xi ) is a binary-encoded sequence and ( yi ) is its measured fitness.

- Define a standard DNN architecture (e.g., a multi-layer perceptron) for regression.

Integrate EN Regularization:

- The key innovation of EN is to add a regularization term to the loss function that encourages sparsity in the Walsh-Hadamard (WH) transform of the DNN's predicted landscape [15].

- The aggregate loss function ( L{\text{total}} ) is: [ L{\text{total}} = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^N (yi - \hat{y}i)^2 + \lambda \| \mathbf{w} \|1 ] where ( \hat{y}_i ) is the DNN prediction, ( \mathbf{w} ) is the vector of WH coefficients of the DNN's output over the entire combinatorial space, and ( \lambda ) is a hyperparameter controlling the strength of regularization.

- For large sequences (length ( d > 25 )), use the scalable EN-S variant, which uses a peeling-decoding algorithm on a sparsely-sampled sequence space to efficiently approximate the top-( k ) WH coefficients without full enumeration [15].

Model Training and Evaluation:

- Use stochastic gradient descent (SGD) to minimize ( L_{\text{total}} ).

- Compare the test set performance (e.g., ( R^2 )) of the EN-regularized DNN against an unregularized DNN and other baseline models (e.g., linear regression with pairwise epistasis) to demonstrate improved generalization.

Data and Modeling Standards

For reproducibility and interoperability in synthetic biology, adhering to community standards is crucial.

- Synthetic Biology Open Language (SBOL): Use SBOL to represent genetic designs unambiguously. SBOL provides a standardized data model for the electronic exchange of genetic design information, which is critical for automating the DBTL cycle [16] [17] [18].

- SBOL Visual: Employ SBOL Visual glyphs to create consistent and clear diagrams of genetic circuits. This standard defines shapes for promoters, coding sequences, and other genetic parts, enhancing scientific communication [16] [19].

- Tool Integration: Tools like LOICA for designing and modeling genetic networks can output SBOL3 descriptions, facilitating the integration of abstract network designs with dynamical models and sequence data [20].

Limitations of Sequential Optimization Approaches in Metabolic Engineering

Metabolic engineering aims to reconfigure cellular metabolic networks to favor the production of desired compounds, ranging from pharmaceuticals and biofuels to sustainable chemicals [21] [22]. The field has traditionally relied on sequential optimization, a methodical approach where researchers identify a perceived major bottleneck in a pathway, engineer a solution, and then proceed to the next identified limitation [23]. This cyclic process of design, build, and test has underpinned many successes in the field.

However, within the modern context of synthetic biology and the push towards more complex biological systems, the inherent constraints of sequential strategies have become increasingly apparent. This application note details the core limitations of sequential optimization and contrasts it with the emerging paradigm of combinatorial optimization, which is better suited for navigating the complex, interconnected landscape of cellular metabolism [23] [7]. Framed within a broader thesis on combinatorial methods, this document provides researchers and drug development professionals with a critical analysis and practical protocols for adopting more efficient, systems-level engineering approaches.

Core Limitations of Sequential Optimization

The sequential approach, while intuitive, struggles to cope with the fundamental nature of biological systems. Its primary shortcomings are summarized below and outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Sequential Optimization in Metabolic Engineering

| Limitation | Underlying Cause | Practical Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to Find Global Optima [23] | Testing variables individually cannot capture synergistic interactions between multiple pathway components. | Results in suboptimal strains and pathways that fail to achieve maximum theoretical yield. |

| Extensive Time and Resource Consumption [23] [7] | The need for multiple, iterative rounds of the Design-Build-Test (DBT) cycle. | Drains project resources and significantly prolongs development timelines for microbial strains. |

| Neglect of System-Level Interactions [21] [22] | Metabolism is a highly interconnected network ("hairball"), not a series of independent linear pathways. | Solving one bottleneck often creates new, unforeseen ones elsewhere in the network, leading to diminishing returns. |

| Low-Throughput Experimental Bottleneck [23] | Typically tests fewer than 10 genetic constructs at a time. | Inefficient exploration of the vast genetic design space, heavily reliant on trial and error [7]. |

Inability to Identify Global Optima

The most significant drawback of sequential optimization is its failure to access the global optimum for a pathway's performance. Metabolic pathways are complex systems where enzymes, regulators, and metabolites interact in non-linear and unpredictable ways [23] [7]. Optimizing the expression of one gene at a time cannot account for the synergistic effects between multiple components. In contrast, combinatorial optimization, which varies multiple elements simultaneously, allows for the systematic screening of a multidimensional design space and is capable of identifying a global optimum that is inaccessible through sequential debugging [23].

Resource Inefficiency and Time Consumption

The sequential process is inherently slow and costly. Each round of identifying a bottleneck, building a genetic construct, and testing its performance requires substantial time and investment. Consequently, successful pathway engineering often requires several laborious and expensive rounds of the DBT cycle [7]. This is compounded by the low-throughput nature of the approach, which usually involves manipulating a single genetic part and testing fewer than ten constructs at a time [23]. This makes the process ill-suited for rapid bioprocess development.

Failure to Account for Network Complexity

Cellular metabolism functions as a web of interconnected reactions, not a simple linear pathway [21]. Flux through this network is regulated at multiple levels—genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and fluxomic—creating a robust system that resists change. A core principle of Metabolic Control Analysis is that control of flux is often distributed across many enzymes, meaning there is rarely a single "rate-limiting step" [21]. Therefore, the sequential approach of conquering individual bottlenecks is a simplification that often fails because relieving one constraint simply causes another to appear elsewhere in the network, leading to diminishing returns on engineering effort [22].

Quantitative Comparison: Sequential vs. Combinatorial Optimization

The operational differences between sequential and combinatorial strategies are stark when quantified. The following table provides a direct comparison based on key performance metrics.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Optimization Strategies

| Parameter | Sequential Optimization | Combinatorial Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Constructs Tested per Cycle | < 10 constructs [23] | Hundreds to thousands of constructs in parallel [23] [7] |

| Design Space Coverage | Limited, one-dimensional | Comprehensive, multidimensional [23] |

| Typical Engineering Focus | Single genetic parts (e.g., promoters, genes) [23] | Multiple variable regions simultaneously (e.g., promoters, RBS, terminators) [7] |

| Optimum Identification | Local optimum | Global optimum [23] |

| Suitability for Complex Circuits | Low, often fails for systems-level functions [7] | High, designed for complex circuits and systems-level functions [7] |

| Underlying Principle | Trial-and-error, hypothesis-driven | Multivariate analysis, design-of-experiments [7] |

Protocol: Implementing a Combinatorial Optimization Workflow

This protocol outlines a generic pipeline for combinatorial pathway optimization, leveraging advanced DNA assembly and genome editing tools to generate and screen diverse strain libraries.

Protocol 1: Generation of a Combinatorial DNA Library

Objective: Assemble a library of genetic constructs where key pathway genes are controlled by diverse regulatory parts (e.g., promoters, RBS) to create a vast array of expression combinations.

Materials:

- GenBuilder DNA Assembly Platform: A proprietary high-throughput system capable of assembling up to 12 parts in one round and building libraries of up to 108 constructs [23].

- Library of Standardized Genetic Parts: Promoters, ribosome binding sites (RBS), gene coding sequences, and terminators from a curated repository [7].

- Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (e.g., for Golden Gate Assembly): For seamless, scarless assembly of multiple DNA fragments [23].

Method:

- Design: Select the target metabolic pathway genes (e.g., Genes A, B, C). For each gene, choose a library of regulatory elements (e.g., 3 promoters of varying strength for Gene A, 4 for Gene B, 3 for Gene C). This creates a theoretical combination space of 3 x 4 x 3 = 36 unique genetic contexts for the pathway.

- In Vitro Assembly: Perform a one-pot Golden Gate assembly reaction using the GenBuilder platform or similar. The terminal homology between adjacent fragments and the linearized plasmid backbone allows for the efficient generation of diverse constructs in a single cloning reaction [7].

- Library Amplification: Transform the assembled library into a suitable E. coli host for amplification. Isolate the pooled plasmid library for downstream integration.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Library Screening using Biosensors

Objective: Rapidly identify high-producing strains from the combinatorial library without time-consuming analytical chemistry.

Materials:

- Genetically Encoded Biosensor: A transcription factor-based circuit that detects the intracellular concentration of the target metabolite and activates a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., GFP) [7].

- Flow Cytometer: A laser-based instrument for detecting fluorescence in single cells at high throughput.

Method:

- Strain Library Construction: Integrate the combinatorial DNA library into the host genome, ensuring stable inheritance. Alternatively, deliver the pathway on a plasmid. The resulting population is a library of microbial strains, each with a unique combination of expression levels for the pathway genes.

- Biosensor Coupling: Ensure each strain in the library contains the genetically encoded biosensor for the product of interest.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Use a flow cytometer to analyze and sort the population of cells based on the fluorescence signal from the biosensor. Cells exhibiting the highest fluorescence are isolated as putative high-producing strains.

- Validation: Cultivate the sorted strains and validate product titers using standard analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS).

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical and operational relationship between the sequential and combinatorial optimization paradigms, highlighting the critical differences in their workflows and outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Success in combinatorial optimization relies on a suite of enabling technologies and reagents. The following table details essential tools for the field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Combinatorial Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Combinatorial Optimization | Key Features & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput DNA Assembly (e.g., GenBuilder) [23] | Parallel assembly of multiple DNA parts to construct vast genetic libraries. | Seamless assembly; up to 12 parts in one reaction; builds libraries of >100 constructs. |

| Orthogonal Regulators (ATFs) [7] | Fine-tuned, independent control of gene expression without interfering with host regulation. | Include CRISPR/dCas9, TALEs, plant-derived TFs; inducible by chemicals or light. |

| Genome-Scale Modeling [22] | In silico prediction of metabolic flux and identification of potential knockout/overexpression targets. | Constraint-based models (e.g., Flux Balance Analysis) to guide rational design. |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors [7] | High-throughput screening by linking metabolite production to a detectable signal (e.g., fluorescence). | Enables rapid sorting of top producers via FACS; bypasses need for slow analytics. |

| CRISPR/Cas-based Editing Tools [7] | Precise, multi-locus integration of combinatorial libraries into the host genome. | Allows stable chromosomal integration of pathway variants; essential for large pathways. |

Sequential optimization, while foundational to metabolic engineering, presents critical limitations in efficiency, cost, and its fundamental ability to navigate the complexity of biological networks for discovering optimal strains. The future of engineering complex phenotypes lies in adopting combinatorial strategies. These approaches, supported by high-throughput DNA assembly, advanced screening methods like biosensors, and powerful computational models, allow researchers to efficiently explore a vast design space and identify high-performing strains that would otherwise remain inaccessible. Integrating these combinatorial methods is essential for accelerating the development of robust microbial cell factories for sustainable chemical, biofuel, and pharmaceutical production.

Toolkit for Success: Machine Learning, CRISPR, and Advanced Regulators in Pathway Optimization

Combinatorial Optimization Problems (COPs) involve selecting an optimal solution from a finite set of possibilities, a challenge endemic to synthetic biology where engineers must choose the best genetic designs from a vast combinatorial space [24]. The Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) directly addresses this by leveraging machine learning (ML) to navigate the complex design space of microbial strains [25]. It formalizes the "Learn" phase of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, transforming it from a manual, expert-dependent process into a systematic, data-driven search algorithm. By treating metabolic engineering as a COP, ART recommends genetic designs predicted to maximize the production of valuable molecules, such as biofuels or therapeutics, thereby accelerating biological engineering [25] [26].

ART Architecture and Workflow Integration

ART integrates into the synthetic biology workflow by bridging the "Learn" and "Design" phases. Its core architecture combines a Bayesian ensemble of models from the scikit-learn library, which is particularly suited to the sparse, expensive-to-generate data typical of biological experiments [25]. Instead of providing a single point prediction, ART outputs a full probability distribution for production levels, enabling rigorous quantification of prediction uncertainty. This probabilistic model is then used with sampling-based optimization to recommend a set of strains to build in the next DBTL cycle, targeting objectives like maximization, minimization, or hitting a specific production target [25].

Table 1: Key Capabilities of the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART)

| Feature | Description | Function in Combinatorial Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Data Integration | Imports data directly from Experimental Data Depo (EDD) or via EDD-style CSV files [25]. | Standardizes input for the learning algorithm from diverse DBTL cycles. |

| Probabilistic Modeling | Uses a Bayesian ensemble of models to predict the full probability distribution of the response variable (e.g., production titer) [25]. | Quantifies uncertainty, enabling risk-aware exploration of the design space. |

| Sampling-Based Optimization | Generates recommendations by optimizing over the learned probabilistic model [25]. | Searches the discrete combinatorial space of possible strains for high-performing candidates. |

| Objective Flexibility | Supports maximization, minimization, and specification of a target production level [25]. | Allows the objective function of the COP to be aligned with diverse project goals. |

The following diagram illustrates how ART is embedded within the recursive DBTL cycle, closing the loop between data generation and design.

Quantitative Performance and Experimental Case Studies

ART's efficacy has been validated across multiple simulated and experimental metabolic engineering projects. The tool's performance is benchmarked by its ability to guide the DBTL cycle toward strains with higher production levels over successive iterations.

Table 2: Experimental Case Studies of ART in Metabolic Engineering

| Project Goal | Input Data for ART | Combinatorial Challenge | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renewable Biofuel [25] | Targeted proteomics data | Optimizing pathway enzyme expression levels | Successfully guided bioengineering despite lack of quantitatively accurate predictions. |

| Hoppy Beer Flavor [25] | Targeted proteomics data | Engineering yeast metabolism to produce specific flavor compounds | Enabled systematic tuning of strain production to match a desired flavor profile. |

| Fatty Acids [25] | Targeted proteomics data | Balancing pathway flux for fatty acid synthesis | Effectively learned from data to recommend improved strains. |

| Tryptophan Production [25] | Promoter combinations | Finding optimal combinations of genetic regulatory parts | Increased tryptophan productivity in yeast by 106% from the base strain. |

Detailed Protocol: Implementing a DBTL Cycle with ART

This protocol details the steps for using ART to guide the combinatorial optimization of a microbial strain for molecule production.

4.1 Prerequisites and Data Preparation

- ML Environment: A computing environment with Python and the ART package installed.

- Data Source: Experimental data from the current and previous DBTL cycles, formatted according to ART's requirements (e.g., an EDD-style CSV file) [25].

- Strain Libraries: The capacity to build and test the recommended microbial strains.

4.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Import Data: Load the experimental data into ART. This data should link the input variables (e.g., proteomic profiles, promoter combinations) to the response variable (e.g., production titer) [25].

- Define Objective: Specify the engineering objective within ART (e.g., "Maximize limonene production") [25].

- Train Model: Execute ART's training routine. The tool will build a Bayesian ensemble model that maps the input data to the production output, including uncertainty estimates [25].

- Generate Recommendations: Run ART's sampling-based optimization. The tool will output a list of recommended input conditions (e.g., targeted proteomic profiles) predicted to achieve the defined objective.

- Interpret and Design: Translate ART's recommendations into concrete genetic designs for the next strain library. This may involve using genome-scale models or genetic engineering techniques to achieve the recommended proteomic profile or promoter configuration [25].

- Build and Test: Synthesize the DNA, transform the host chassis, and cultivate the new strains. Precisely measure the production titer of the target molecule.

- Iterate: Add the new experimental results to the existing dataset and return to Step 1 for the next DBTL cycle.

The following flowchart depicts the logical decision process within a single ART-informed DBTL cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for an ART-Driven Project

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| DNA Parts & Libraries | Provides the combinatorial building blocks (promoters, genes, terminators) for constructing genetic variants as recommended by ART. |

| Microbial Chassis | The host organism (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae) that will be engineered to produce the target molecule. |

| Culture Media | Supports the growth of the microbial chassis during the "Build" and "Test" phases; composition can be a variable for optimization. |

| Proteomics Kits | Enables the generation of targeted proteomics data, which can serve as a key input for ART's predictive model [25]. |

| Analytical Standards | Essential for calibrating equipment (e.g., GC-MS, HPLC) to accurately quantify the titer of the target molecule during testing. |

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a systematic framework for metabolic engineering and synthetic biology, enabling more efficient biological strain development than historical trial-and-error approaches [27]. This engineering paradigm has become increasingly powerful through integration with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), which transform DBTL from a descriptive process to a predictive and generative one [28] [29]. When framed within combinatorial optimization methods, AI-driven DBTL cycles allow researchers to navigate vast biological design spaces efficiently, identifying optimal genetic constructs and process parameters through iterative computational-experimental feedback loops [28] [30].

The core challenge addressed by AI integration is the involution of DBTL cycles, where iterative strain development leads to increased complexity without proportional gains in productivity [28]. Traditional mechanistic models struggle with the highly nonlinear, multifactorial nature of biological systems, where cellular processes interact with multiscale engineering variables including bioreactor conditions, media composition, and metabolic regulations [28]. ML algorithms overcome these limitations by capturing complex patterns from experimental data without requiring complete mechanistic understanding, thereby accelerating the optimization of microbial cell factories for applications in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and bio-based product manufacturing [28] [31].

AI-Driven Predictive Modeling in the DBTL Framework

Machine Learning Approaches Across the DBTL Cycle

Table 1: ML Techniques Applied Across the DBTL Cycle

| DBTL Phase | ML Approach | Application Examples | Key Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Supervised Learning, Generative AI | Predictive biodesign, Pathway optimization, Regulatory element design | Bayesian Optimization [31], Deep Learning [30], Transformer Models [32] |

| Build | Active Learning | Experimental prioritization, Synthesis planning | ART (Automated Recommendation Tool) [30], Reinforcement Learning [28] |

| Test | Computer Vision, Pattern Recognition | High-throughput screening analysis, Multi-omics data processing | Deep Neural Networks [33], Convolutional Neural Networks |

| Learn | Unsupervised Learning, Feature Engineering | Data integration, Pattern recognition, Causal inference | Dimensionality Reduction, Knowledge Mining [28], Ensemble Methods [28] |

AI technologies enhance each stage of the DBTL cycle through specialized computational approaches. During the Design phase, generative AI models create novel biological sequences with specified properties, exploring design spaces beyond human intuition [29] [31]. Tools like the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) employ Bayesian optimization to recommend genetic designs that improve product titers based on previous experimental data [30]. For the Build phase, active learning frameworks prioritize which genetic variants to construct, significantly reducing experimental burden [30] [27]. In the Test phase, computer vision and pattern recognition algorithms analyze high-throughput screening data, while in the Learn phase, unsupervised learning and feature engineering extract meaningful patterns from multi-omics datasets to inform subsequent design iterations [28].

The Integrated AI-Driven DBTL Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the continuous, AI-enhanced DBTL cycle, highlighting the key computational and experimental actions at each stage:

Diagram 1: The AI-Enhanced DBTL Cycle. This continuous iterative process uses machine learning to bridge computational design and experimental validation.

Combinatorial Optimization in Biological Design

Combinatorial optimization provides the mathematical foundation for navigating the immense design spaces in synthetic biology. The biological design problem can be formulated as a mixed integer linear program (MILP) or mixed integer nonlinear program (MINLP) where the objective is to find optimal genetic sequences that maximize desired phenotypic outputs [34]. This approach employs topological indices and molecular connectivity indices as numerical descriptors of molecular structure, enabling the development of structure-activity relationships (SARs) that correlate genetic designs with functional outcomes [34].

In practice, combinatorial optimization with AI addresses the challenge of high-dimensional biological spaces. For example, engineering a microbial strain might involve optimizing dozens of genes, promoters, and ribosome binding sites, creating a combinatorial explosion where testing all variants is experimentally infeasible [28] [27]. ML models trained on initial experimental data can predict the performance of untested genetic combinations, guiding the selection of the most promising variants for subsequent DBTL cycles [30] [27]. This approach was demonstrated in dodecanol production, where Bayesian optimization over two DBTL cycles increased titers by 21% while reducing the number of strains needing construction and testing [27].

Application Notes: AI-Driven Dodecanol Production in E. coli

Experimental Protocol

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for AI-Driven Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Thioesterase (UcFatB1) | Releases fatty acids from acyl-ACP | Initiate fatty acid biosynthesis pathway [27] |

| Acyl-ACP/acyl-CoA Reductases | Converts acyl-ACP/acyl-CoA to fatty aldehydes | Dodecanol production pathway [27] |

| Acyl-CoA Synthetase (FadD) | Activates fatty acids to acyl-CoAs | Fatty acid metabolism [27] |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Library | Modulates translation initiation rate | Fine-tune protein expression levels [27] |

| Pathway Operon | Coordinates expression of multiple genes | Ensures balanced metabolic flux [27] |

| Proteomics Analysis Tools | Quantifies protein expression levels | Data for machine learning training [27] |

Objective: Engineer Escherichia coli MG1655 for enhanced production of 1-dodecanol from glucose through two iterative DBTL cycles aided by machine learning [27].

Strain Design and Engineering:

- Construct First-Generation Strains: Create 36 engineered E. coli strains modulating three key variables:

- Express thioesterase (UcFatB1) to initiate fatty acid biosynthesis

- Test three different acyl-ACP/acyl-CoA reductases (Maqu2507, Maqu2220, or Acr1)

- Incorporate varying ribosome binding sites to tune expression levels

- Include acyl-CoA synthetase (FadD) in a single pathway operon [27]

Culture Conditions:

- Grow strains in minimal medium with glucose as carbon source

- Maintain standardized bioreactor conditions (temperature, pH, aeration)

- Monitor cell growth and metabolite profiles [27]

Data Collection:

- Quantify dodecanol production titers using GC-MS

- Measure absolute concentrations of all proteins in engineered pathway via proteomics

- Record corresponding genetic designs (promoter combinations, RBS variants) [27]

Machine Learning Analysis:

- Train multiple ML algorithms on Cycle 1 data

- Use protein expression profiles and genetic designs as input features

- Model relationship between protein levels and dodecanol production

- Generate predictions for optimal protein profiles to maximize titer [27]

Cycle 2 Implementation:

- Design 24 new strains based on ML recommendations

- Construct strains targeting predicted optimal protein expression ratios

- Test strains using identical culture and analytics protocols

- Validate model predictions against experimental measurements [27]

Performance Metrics and Outcomes

Table 3: Quantitative Results from AI-Driven Dodecanol Production

| Metric | Cycle 1 Performance | Cycle 2 Performance | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Dodecanol Titer | 0.69 g/L | 0.83 g/L | 21% increase [27] |

| Fold Improvement vs. Literature | >5-fold over previous reports | >6-fold over previous reports | Significant benchmark advancement [27] |

| Number of Strains Tested | 36 strains | 24 strains | 33% reduction in experimental load [27] |

| Data Generation | Proteomics + production data | Proteomics + production data | Consistent data quality for ML [27] |

The implementation of two DBTL cycles for dodecanol production demonstrated that machine learning guidance can significantly enhance metabolic engineering outcomes while reducing experimental burden. The key innovation was using protein expression data as inputs for ML models, enabling predictions of optimal expression profiles for enhanced production [27]. This approach resulted in a 21% titer increase in the second cycle and a greater than 6-fold improvement over previously reported values for minimal medium, highlighting the power of data-driven biological design [27].

Implementation Protocols for AI-Enhanced DBTL

Computational Infrastructure Requirements

Successful implementation of AI-driven DBTL cycles requires specific computational infrastructure:

- Data Management Systems: Standardized ontologies and repositories like the Experiment Data Depot (EDD) to ensure consistent, machine-readable data across cycles [30]

- ML Platforms: Integration of tools like the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) capable of working with small datasets (as few as 27 instances) and providing uncertainty quantification [30]

- Model Training Frameworks: Support for supervised learning, Bayesian optimization, and active learning approaches tailored to biological data characteristics [28] [30]

Quality Control Considerations

Critical quality control measures must be implemented throughout AI-driven DBTL cycles:

- Sequencing Verification: Validate plasmids in both cloning and production strains to avoid unintended mutations [27]

- Proteomics Standards: Implement rigorous protocols for protein quantification to ensure high-quality training data [27]

- Model Validation: Employ cross-validation and holdout testing to assess prediction accuracy before experimental implementation [28]

- Benchmarking: Compare AI-directed designs against traditional approaches to quantify value addition [31]

Future Perspectives and Challenges