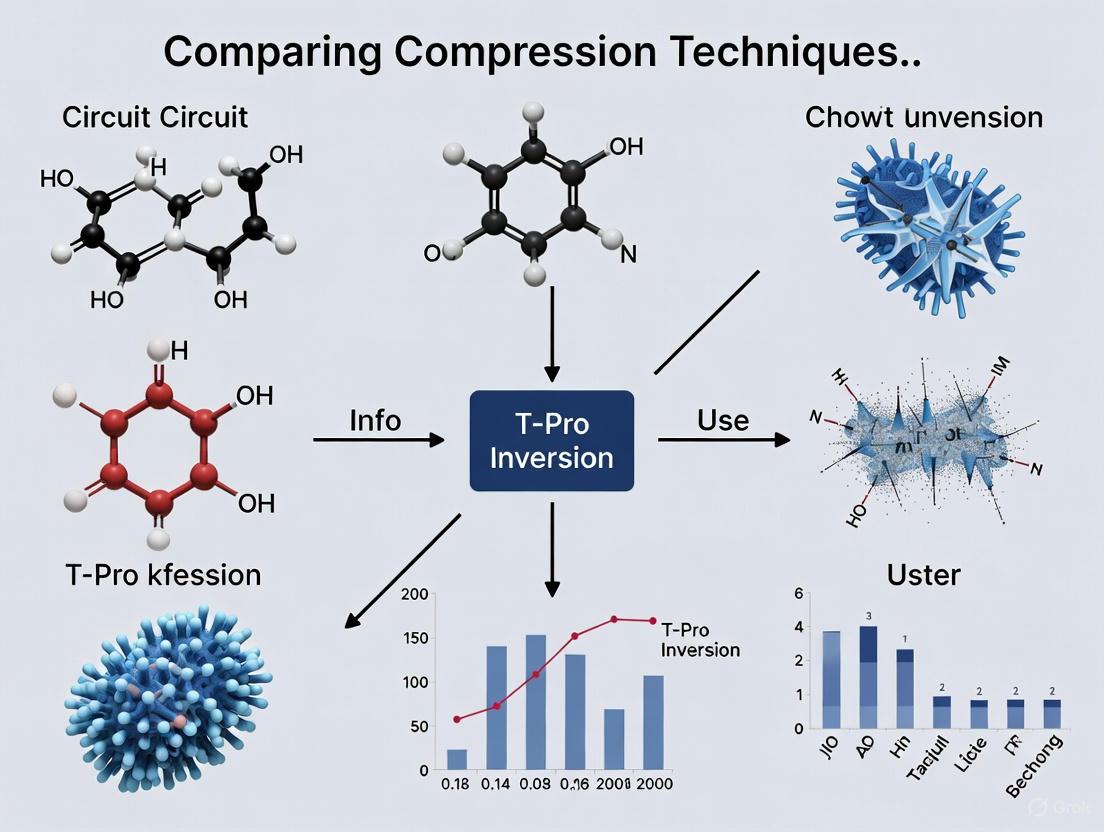

Circuit Compression in Synthetic Biology: A Comparative Analysis of T-Pro vs. Inversion-Based Genetic Circuit Design

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of circuit compression techniques in synthetic biology, focusing on the emerging Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) approach against traditional inversion-based methods.

Circuit Compression in Synthetic Biology: A Comparative Analysis of T-Pro vs. Inversion-Based Genetic Circuit Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of circuit compression techniques in synthetic biology, focusing on the emerging Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) approach against traditional inversion-based methods. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of both methodologies, detail the wetware and software enabling T-Pro's predictive design, address critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and validate performance through direct comparative analysis. The synthesis of this information highlights how advanced compression technologies are enabling more complex genetic circuits with minimal metabolic burden, offering significant implications for biomedical research, therapeutic development, and precision bio-manufacturing.

Deconstructing Genetic Circuit Design: From Traditional Inversion to Advanced Transcriptional Programming

The field of synthetic biology aims to program living cells with predictable functions by designing genetic circuits that sense, compute, and respond to biological signals. However, a fundamental challenge persists: while we can qualitatively design genetic circuits that perform basic logical operations, we struggle to quantitatively predict their performance in living systems. This discrepancy between intended design and actual biological behavior constitutes the core "Synthetic Biology Problem." As circuit complexity increases, limitations in biological modularity and host metabolic burden amplify this challenge, restricting our ability to engineer sophisticated cellular functions for therapeutic and bioproduction applications [1].

This comparison guide examines contemporary approaches addressing this problem, with particular focus on circuit compression techniques like Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) that minimize genetic footprint while maintaining predictable function. We objectively evaluate competing methodologies based on experimental performance data, provide detailed protocols for key experiments, and identify essential research tools for scientists working at this interface of computational design and biological implementation.

Comparative Analysis of Leading Technological Approaches

Circuit Compression via Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro)

The T-Pro framework represents a significant advancement in genetic circuit design, utilizing synthetic transcription factors (TFs) and cognate promoters to implement logical operations with minimal components. Unlike traditional inversion-based circuits that require multiple cascading gates to implement simple logic, T-Pro employs anti-repressor systems that directly implement NOT/NOR operations with fewer genetic parts [1].

Core Mechanism: T-Pro leverages engineered repressor and anti-repressor transcription factors that coordinately bind synthetic promoters. This architecture eliminates the need for transcriptional inversion, reducing part count and metabolic burden. Recent work has expanded T-Pro from 2-input to 3-input Boolean logic, enabling higher-state decision-making with eight possible input combinations (000 through 111) [1].

Experimental Validation: Researchers developed a complete set of synthetic T-Pro anti-repressors responsive to cellobiose, building upon existing IPTG and D-ribose responsive systems. Using the CelR regulatory scaffold, they engineered E+TAN repressors and subsequent anti-repressors (EA1TAN, EA2TAN, EA3TAN) through site-saturation mutagenesis and error-prone PCR. These components were paired with synthetic promoters featuring tandem operator designs, creating orthogonal regulatory systems [1].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of T-Pro Circuit Compression

| Metric | T-Pro 3-Input Circuits | Traditional Inversion Circuits | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Part Count | Minimal (compressed) | ~4x larger | ~4x reduction |

| Quantitative Prediction Error | <1.4-fold average error | Typically >2-fold error | >40% improvement |

| Boolean Operations Supported | 256 distinct truth tables | Limited by complexity | Significant expansion |

| Metabolic Burden | Reduced | High | Substantial reduction |

| Application Demonstrated | Recombinase memory, metabolic pathway control | Limited by scaling constraints | Broader applicability |

Dynamic Delay Modeling for Predictive Analysis

The Dynamic Delay Model (DDM) offers a complementary approach to the synthetic biology problem by focusing on temporal aspects of circuit behavior. This modeling framework separates circuit dynamics into two components: a dynamic determining part and a dose-related steady-state determining part [2].

Methodology: DDM provides explicit formulas for dynamic determination functions, traditionally represented as simple delay times without clear mathematical formulation. Researchers developed measurement protocols using microfluidic systems to parameterize eight activators and five repressors, then validated the model across three synthetic circuits with improved prediction accuracy [2].

Comparative Advantage: While T-Pro addresses part count reduction and qualitative design simplification, DDM specifically enhances quantitative prediction of temporal behavior, addressing a different dimension of the synthetic biology problem.

Structure-Augmented Regression for Machine Learning Prediction

Machine learning approaches offer a data-driven solution to the prediction challenge. Structure-Augmented Regression (SAR) exploits intrinsic lower-dimensional structures in biological response landscapes to improve prediction accuracy with limited training data [3].

Experimental Validation: Researchers demonstrated SAR on multiple biological systems and input dimensions, showing superior performance with limited datasets compared to other machine learning methods. The algorithm identifies characteristic response patterns (e.g., synergistic vs. antagonistic drug interactions), then uses these learned structures to constrain quantitative predictions [3].

Application Scope: Unlike mechanistic approaches like T-Pro, SAR requires no prior knowledge of underlying biological mechanisms, making it applicable to diverse systems from drug combinations to metabolic engineering.

Table 2: Comparison of Approaches to the Synthetic Biology Problem

| Approach | Core Methodology | Primary Advantage | Limitations | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-Pro Circuit Compression | Synthetic transcription factors & promoters | 4x part reduction, <1.4-fold prediction error | Requires specialized TF engineering | Complex logic circuits, metabolic burden-sensitive applications |

| Dynamic Delay Modeling | Temporal dynamics separation | Improved kinetic prediction | Less focus on part count reduction | Applications requiring precise temporal control |

| Structure-Augmented Regression | Machine learning with structural constraints | High accuracy with minimal data | Black-box prediction, limited interpretability | Systems with unknown mechanisms, high-dimensional optimization |

| Probabilistic Bit Circuits | Weighted random number generation | Handles biological noise naturally | Sequential updating challenging biologically | Environmental sensing, adaptive systems |

| Automated Recommendation Tool | Algorithmic strain recommendation | Guides experimental design | Requires substantial training data | Metabolic engineering, pathway optimization |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

T-Pro Anti-Repressor Engineering Protocol

Objective: Engineer anti-repressor transcription factors from repressor scaffolds for T-Pro circuit implementation.

Materials:

- CelR regulatory core domain (RCD) scaffold

- Site-saturation mutagenesis reagents

- Error-prone PCR kit

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) system

- Synthetic promoter library with tandem operator designs

Procedure:

- Repressor Selection: Identify candidate repressors based on dynamic range and ON-state expression level in presence of inducer (cellobiose).

- Super-Repressor Generation: Perform site-saturation mutagenesis at amino acid position 75 to create ligand-insensitive DNA-binding variants.

- Anti-Repressor Library Creation: Conduct error-prone PCR on super-repressor template at low mutation rate to generate ~10^8 variants.

- FACS Screening: Sort variant library for anti-repressor phenotype (expression in presence of repressing conditions).

- ADR Expansion: Equip validated anti-repressors with additional alternate DNA recognition domains (YQR, NAR, HQN, KSL).

- Orthogonality Validation: Test anti-repressor sets against synthetic promoters to confirm orthogonal operation.

Validation Metrics: Dynamic range >100-fold, ON-state expression sufficient for downstream signaling, orthogonality to existing TF systems (IPTG, D-ribose responsive) [1].

Algorithmic Circuit Enumeration for Compression Optimization

Objective: Identify minimal genetic implementation for 3-input Boolean logic operations.

Materials:

- T-Pro component library (synthetic TFs, promoters)

- Algorithmic enumeration software

- Directed acyclic graph representation framework

Procedure:

- Component Generalization: Abstract synthetic transcription factors and promoters to enable >5 orthogonal protein-DNA interactions.

- Space Enumeration: Systematically enumerate circuits in order of increasing complexity using directed acyclic graph models.

- Compression Optimization: For each of 256 possible truth tables, identify circuit with minimal component count.

- Context Accounting: Incorporate genetic context parameters to predict expression levels.

- Validation: Test predicted circuits experimentally, compare measured vs. predicted outputs.

Computational Considerations: Search space approximately 10^14 possible circuits; sequential enumeration ensures most compressed solution identification [1].

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

T-Pro Circuit Compression Architecture

Synthetic Biology Problem Bridge

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Synthetic Biology Problem Investigation

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293T Designer Cells | Stable host for circuit implementation | Viral protease inhibitor screening [4] | Dual-fluorescence outputs, safety for viral targets |

| T-Pro Anti-Repressor Library | Engineered transcription factors | Circuit compression implementation [1] | Orthogonal response to IPTG, ribose, cellobiose |

| Synthetic Promoter Library | Tandem operator designs | T-Pro circuit construction [1] | Compatible with synthetic TF ADR domains |

| Microfluidic Parameterization System | Dynamic measurement of circuit components | DDM parameterization [2] | High-temporal resolution for 8 activators, 5 repressors |

| Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) | Machine learning recommendation engine | Strain optimization [5] | Predicts optimal genetic configurations |

| SAR Algorithm Platform | Structure-augmented regression | Limited-data prediction [3] | Exploits low-dimensional biological structures |

| Probabilistic Bit Components | Weighted random number generation | Noise-tolerant circuits [6] | Implements probabilistic Boolean logic |

The synthetic biology problem represents a critical challenge in our ability to reliably engineer biological systems. Through comparative analysis, T-Pro circuit compression demonstrates significant advantages in reducing genetic footprint while maintaining predictive accuracy, with 4-fold size reduction and <1.4-fold prediction error. However, complementary approaches including dynamic delay modeling and structure-augmented regression address different dimensions of the prediction challenge, suggesting that integrated methodologies may provide the most comprehensive solution.

For research teams selecting approaches, T-Pro offers particular advantage for implementing complex logical operations in metabolic burden-sensitive contexts, while machine learning methods excel in systems with unknown mechanisms. As the field progresses, the increasing integration of computational design with experimental validation through platforms like automated recommendation tools represents a promising direction for bridging the qualitative-quantitative divide and enabling predictable programming of biological systems.

Inversion-based genetic circuits represent a foundational technology in synthetic biology for implementing Boolean logic, particularly the NOT function, in cellular programming. While these circuits have enabled sophisticated cellular reprogramming for biotechnology and therapeutic applications, they are characterized by significant limitations in scalability and metabolic burden. This review provides a comparative analysis of inversion-based circuits against emerging circuit compression technologies, with particular focus on Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) as a promising alternative. We examine quantitative performance metrics, detailed experimental methodologies, and practical implementation considerations to guide researchers in selecting appropriate genetic circuit architectures for specific applications. The evidence suggests that while inversion-based circuits remain valuable for simpler applications, compressed architectures offer substantial advantages for complex circuits requiring higher computational density and reduced cellular burden.

Genetic circuits are engineered networks of biological components that program cells to perform predefined functions, enabling applications spanning bioproduction, living therapeutics, and diagnostic systems [7]. These circuits process intracellular and extracellular signals using logic operations analogous to electronic circuits. The architecture of these circuits—how genetic components are organized and interconnected—fundamentally determines their performance characteristics, implementation complexity, and cellular impact [8]. Inversion-based genetic circuits represent a classical approach that utilizes transcriptional repression to implement Boolean NOT and NOR logic, forming the foundation for more complex genetic computing [1]. While conceptually straightforward and widely implemented, this architecture imposes significant constraints on circuit scalability due to component count and metabolic burden on host cells [1].

Recent advances in circuit design have introduced compression techniques that minimize genetic footprint while maintaining or expanding computational capability. Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) exemplifies this approach by leveraging synthetic transcription factors (repressors and anti-repressors) and cognate synthetic promoters to achieve complex logic with reduced component count [1]. This review systematically compares these architectural paradigms, providing researchers with experimental data, implementation protocols, and performance metrics to inform circuit selection for specific applications. Understanding these architectural trade-offs is particularly crucial for drug development professionals engineering cellular therapies, where predictable performance and minimal cellular burden are paramount for therapeutic efficacy and safety.

Principles of Inversion-Based Genetic Circuits

Fundamental Operational Mechanisms

Inversion-based genetic circuits function by implementing transcriptional repression as their primary operational mechanism, effectively creating genetic analogues to electronic NOT gates. These circuits typically employ repressor proteins that bind to specific operator sequences within promoter regions, preventing transcription initiation of downstream genes [7]. The foundational architecture involves a repressor gene under control of an input-sensitive promoter, which then regulates an output gene. When an input signal is present, it either induces or represses repressor production, leading to the inverted output expression pattern [1]. This basic building block can be combined to create more complex logic functions, such as NOR gates, which are functionally complete for implementing any Boolean logic operation.

The molecular components of inversion circuits typically include well-characterized repressor systems such as LacI, TetR, and Lambda CI, which have been extensively engineered for orthogonality and predictable performance [7]. These systems leverage small molecule inducers (e.g., IPTG, aTc) to control repressor DNA-binding activity, enabling external control of circuit behavior. Implementation requires careful balancing of repressor expression levels, DNA binding affinities, and promoter strengths to achieve desired input-output characteristics. The performance of these circuits is typically quantified by their dynamic range (ratio between ON and OFF states), response threshold (input concentration triggering state transition), and leakage (undesired expression in OFF state) [8].

Experimental Implementation and Validation

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Inversion-Based Genetic Circuits

| Component Type | Specific Examples | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repressor Proteins | LacI, TetR, Lambda CI | Implement NOT logic by blocking transcription | Well-characterized kinetics, available mutants |

| Inducer Molecules | IPTG, aTc, Arabinose | Control repressor activity | Varying permeability, specificity, and toxicity |

| Promoter Systems | PLac, PTet, PLambda | Drive repressor and output expression | Different strengths, regulation mechanisms |

| Reporter Genes | GFP, RFP, LacZ | Quantify circuit performance | Different maturation times, stability, detection methods |

| Vector Backbones | Plasmids with different copy numbers | Circuit delivery and maintenance | Varying copy numbers, compatibility, stability |

Experimental implementation of inversion-based circuits begins with selection of orthogonal repressor systems that minimize crosstalk. A typical implementation protocol involves assembling genetic components using standard molecular biology techniques such as Golden Gate assembly or Gibson assembly [7]. The input-output relationship is characterized by measuring output protein levels (typically fluorescent reporters) across a range of input concentrations. For the inverting amplifier circuit described by Nagaraj et al., testing involved both fluorometer measurements and flow cytometry to quantify performance at population and single-cell levels [9]. This circuit successfully performed as an inverting amplifier, echoing the function of its electronic counterpart, though cellular loading by synthetic circuits impacted performance [9].

Characterization protocols must account for context-dependence of parts, where identical genetic elements can behave differently depending on their genetic context, including upstream and downstream sequences, plasmid copy number, and host factors [7]. Optimization often requires iterative tuning of ribosome binding sites, promoter strengths, and repressor levels to achieve desired performance. Validation should include long-term stability assays to assess evolutionary stability, as circuits that impose significant burden may accumulate inactivating mutations over time.

Limitations of Inversion-Based Circuits

Metabolic Burden and Resource Competition

The implementation of inversion-based genetic circuits imposes substantial metabolic burden on host cells, primarily through competition for limited cellular resources. This burden manifests as reduced growth rates, decreased viability, and impaired physiological function [10]. The mechanisms underlying this burden include: (1) diversion of transcriptional and translational machinery (RNA polymerase, ribosomes, amino acids, nucleotides) toward circuit components rather than essential cellular functions; (2) energy consumption for synthesis, maintenance, and degradation of circuit components; and (3) potential toxicity from heterologous protein expression or circuit operation [10]. This metabolic burden becomes increasingly severe as circuit complexity grows, fundamentally limiting the scalability of inversion-based architectures.

Metabolic burden impacts both circuit performance and host cell fitness, creating evolutionary pressure toward circuit inactivation. Cells may develop mutations that disrupt circuit function to alleviate burden, leading to population heterogeneity and loss of function over time. This is particularly problematic for long-term applications such as continuous bioproduction or persistent therapeutic activity. Studies have demonstrated that burdened cells exhibit global transcriptional and metabolic changes, including altered expression of genes involved in energy metabolism, stress response, and ribosome biogenesis [10]. These systemic effects complicate circuit behavior prediction and can lead to context-dependent performance variations across different host strains or growth conditions.

Scalability Constraints and Performance Limitations

The resource-intensive nature of inversion-based circuits creates fundamental scalability constraints. Each additional logic gate requires dedicated genetic components (promoters, coding sequences, terminators), linearly increasing genetic footprint and resource consumption [1]. This parts proliferation problem means that complex circuits comprising multiple gates become prohibitively large and burdensome, with diminishing performance as complexity increases. Additionally, the physical space constraints of delivery vectors (particularly viruses with limited cargo capacity) further restrict implementation complexity.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Genetic Circuit Architectures

| Performance Metric | Inversion-Based Circuits | T-Pro Compression Circuits | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parts Count (3-input) | ~12-15 components | ~3-4 components | ~4x reduction [1] |

| Prediction Error | Often >2-fold | <1.4-fold average error | >1.4x improvement [1] |

| Metabolic Burden | High (linear increase with complexity) | Reduced (minimal footprint) | Significant reduction [1] |

| Design Complexity | Manual, intuitive design | Algorithmic enumeration | Automated optimization [1] |

| Orthogonality Requirements | High (multiple repressors needed) | Moderate (engineered ADR variants) | More efficient part reuse |

Performance limitations include limited dynamic range, signal attenuation, and slow response times. As signals propagate through multiple inversion stages, each gate introduces noise, delay, and potential loss of signal integrity [9]. This necessitates careful balancing and tuning of each component, a process that becomes exponentially more difficult as circuit complexity grows. The qualitative understanding of how to design fundamental genetic circuit architectures does not translate reliably to quantitative performance prediction, creating what has been termed the "synthetic biology problem" – the discrepancy between qualitative design and quantitative performance prediction [1]. This predictability gap necessitates labor-intensive experimental optimization, further increasing development time and resources.

Circuit Compression Techniques: The T-Pro Approach

Fundamental Principles of Circuit Compression

Circuit compression refers to genetic circuit design strategies that minimize component count while maintaining or expanding computational capability. Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) represents a leading compression approach that leverages synthetic transcription factors (repressors and anti-repressors) and cognate synthetic promoters to implement complex logic with reduced parts count [1]. Unlike inversion-based circuits that primarily utilize repression, T-Pro circuits employ both repression and anti-repression mechanisms, where anti-repressors bind promoters and actively recruit transcriptional machinery in a signal-responsive manner. This enables more efficient implementation of Boolean operations, particularly those requiring AND-like logic.

The compression advantage stems from several key features: (1) multi-input promoter architectures that integrate multiple signals at single promoters rather than requiring separate gates for each operation; (2) reusability of synthetic transcription factor cores with different DNA-binding specificities; and (3) elimination of intermediary inversion steps required to transform logic operations in traditional architectures [1]. T-Pro has demonstrated the capability to implement all 2-input Boolean operations (16 logic functions) with significantly reduced complexity compared to inversion-based implementations. Recent work has expanded this capability to 3-input Boolean logic (256 functions) through the development of additional orthogonal synthetic transcription factor systems responsive to cellobiose, IPTG, and D-ribose [1].

Computational Design and Automation

A critical advancement enabling practical implementation of compressed circuits is the development of computational design tools that automate circuit architecture optimization. Huang et al. developed an algorithmic enumeration method that systematically identifies minimal circuit implementations for specified truth tables from a combinatorial space exceeding 100 trillion putative circuits [1]. This software approach guarantees identification of the most compressed circuit for a given operation, eliminating the need for intuitive design and manual optimization.

The computational workflow involves: (1) generalized description of synthetic transcription factors and promoters to accommodate expanding orthogonal sets; (2) modeling circuits as directed acyclic graphs; (3) systematic enumeration of circuits in order of increasing complexity; and (4) optimization for minimal genetic footprint while meeting quantitative performance specifications [1]. This automated approach achieves remarkable predictive accuracy, with quantitative predictions averaging below 1.4-fold error across more than 50 test cases. The integration of computational design with modular wetware components creates a virtuous cycle where experimental data improves model accuracy, which in turn guides more effective experimental designs.

Comparative Experimental Analysis

Methodology for Circuit Performance Evaluation

Rigorous evaluation of genetic circuit performance requires standardized methodologies and metrics. For both inversion-based and compression circuits, characterization typically involves the following experimental protocol:

Genetic Construction: Circuits are assembled using standardized parts and modular cloning systems (e.g., Golden Gate or MoClo) to ensure reproducibility and enable combinatorial variation. Parts are typically encoded on plasmids with controlled copy numbers, though chromosomal integration is preferred for long-term stability.

Transformation and Cultivation: Constructs are transformed into host cells (typically E. coli for initial characterization), with multiple clones selected to control for position effects. Cells are cultivated under defined conditions with appropriate selection pressure.

Input-Output Characterization: Cultures are exposed to systematic variations of input signals (inducer concentrations), and output is quantified using flow cytometry to capture population distributions and single-cell variability. Fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP variants) serve as reporters, with careful attention to maturation times and stability.

Burden Assessment: Growth rates are monitored via optical density measurements, with relative fitness compared to control strains lacking circuits. More sophisticated burden metrics may include RNA sequencing to assess global transcriptional changes or resource balance analysis.

Long-Term Stability: Cultures are passaged repeatedly without selection to assess evolutionary stability, with periodic sampling to determine circuit retention and function.

For T-Pro circuits specifically, the experimental workflow includes additional validation steps for synthetic transcription factor performance, including measurement of dynamic range, ligand sensitivity, and orthogonality against other regulatory components in the system [1].

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

Direct comparison of inversion-based and compression circuits reveals significant advantages for compressed architectures across multiple metrics. T-Pro circuits demonstrate approximately 4-fold reduction in size compared to canonical inverter-type genetic circuits implementing equivalent functions [1]. This compression directly translates to reduced metabolic burden, though quantitative burden metrics were not explicitly reported in the available literature. The parts count reduction is particularly dramatic for complex operations – where a 3-input logic circuit might require 12-15 components in inversion-based architecture, T-Pro implementations typically achieve equivalent functionality with just 3-4 components.

Perhaps more significantly, T-Pro circuits demonstrate superior predictability, with quantitative performance predictions averaging below 1.4-fold error compared to experimental measurements [1]. This predictability stems from the more modular nature of the components and the sophisticated modeling approaches employed. For inversion-based circuits, performance prediction is considerably more challenging due to context effects and the complex interplay between multiple regulatory layers. This predictability advantage substantially reduces the iterative optimization cycle, accelerating development timelines for novel circuit implementations.

Diagram 1: Architectural comparison showing simplified T-Pro implementation of equivalent logic function with reduced component count.

Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Therapeutic Development

Dynamic Regulation of Metabolic Pathways

Both inversion-based and compression circuits find important applications in metabolic engineering, where they enable dynamic control of metabolic fluxes to optimize product synthesis. Genetic circuits can balance the inherent trade-off between cell growth and product synthesis by dynamically regulating pathway expression in response to metabolic states [8]. For example, circuits can be designed to repress pathway expression during growth phases and activate expression during production phases, or to respond to metabolite levels to avoid toxic intermediate accumulation.

A notable application involves controlling flux through toxic biosynthetic pathways, where T-Pro circuits have demonstrated precise setpoint control [1]. Similarly, inversion-based circuits have been employed for dynamic regulation in Corynebacterium glutamicum for high-level gamma-aminobutyric acid production from glycerol [8] and in Escherichia coli for balancing malonyl-CoA node allocation in (2S)-naringenin biosynthesis [8]. These implementations maximize metabolic flux toward product synthesis while maintaining cell viability, addressing a fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering.

High-Throughput Screening and Diagnostics

Genetic circuits serve as powerful tools for high-throughput screening of enzyme variants or producer strains. Biosensor circuits that respond to specific metabolites can be coupled to fluorescent reporters or antibiotic resistance markers to enable selection of high-performing variants from combinatorial libraries [8]. For example, erythromycin biosensors with modulated sensitivity have been developed for precise high-throughput screening of strains with different production characteristics [8]. Similarly, biosensors for p-coumaroyl-CoA have been implemented for dynamic regulation of naringenin biosynthesis in yeast [8].

In diagnostic applications, inversion-based logic has been employed in cell-based biosensors for disease markers, potentially enabling smart therapeutics that activate only in presence of disease-specific signals. The compression advantage of T-Pro circuits is particularly valuable for therapeutic applications where delivery vector capacity is limited, such as in viral vector-based gene therapies. The reduced genetic footprint enables incorporation of more complex control logic within size-constrained delivery systems.

Research Toolkit and Implementation Guidelines

Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for T-Pro Compression Circuits

| Component Type | Specific Examples | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Anti-Repressors | EA1TAN, EA2TAN, EA3TAN | Implement NOT/NOR logic with fewer parts | Engineered from repressor scaffolds |

| Synthetic Repressors | E+TAN, E+YQR, E+NAR | Transcriptional repression | Orthogonal DNA binding specificities |

| Synthetic Promoters | T-Pro promoter variants | Regulated by synthetic TFs | Tandem operator designs |

| Inducer Systems | IPTG, D-ribose, Cellobiose | Control synthetic TF activity | Orthogonal signal response |

| Algorithmic Tools | Enumeration-optimization software | Automated circuit design | Identifies minimal implementations |

Implementation of advanced genetic circuits requires specialized reagents and computational tools. For T-Pro circuits, essential components include synthetic transcription factors with engineered DNA-binding specificities and cognate synthetic promoters. The anti-repressor set (EA1TAN, EA2TAN, EA3TAN) developed through error-prone PCR screening provides NOT/NOR functionality with minimal parts count [1]. These are complemented by synthetic repressors (E+TAN, E+YQR, E+NAR) that recognize orthogonal operator sequences. Inducer systems responsive to IPTG, D-ribose, and cellobiose provide orthogonal control of the respective synthetic transcription factor sets [1].

Critical computational tools include the algorithmic enumeration-optimization software that identifies minimal circuit implementations for specified truth tables from the vast combinatorial design space [1]. This software models circuits as directed acyclic graphs and systematically enumerates solutions in order of increasing complexity, guaranteeing identification of the most compressed implementation. Additional modeling tools account for genetic context in predicting expression levels, enabling quantitative performance prediction with high accuracy.

Implementation Workflow and Best Practices

Diagram 2: T-Pro circuit implementation workflow showing integrated computational and experimental phases.

Successful implementation of compressed genetic circuits follows a structured workflow that integrates computational design with experimental validation. The process begins with precise specification of the desired logic function as a truth table. This truth table serves as input to the algorithmic enumeration software, which identifies all possible minimal implementations from the combinatorial design space [1]. The researcher then selects the optimal implementation based on additional constraints such as part availability, prior characterization data, or specific performance requirements.

Experimental implementation involves assembly of selected components using standardized cloning methods, followed by quantitative characterization of input-output relationships and dynamic range. For metabolic engineering applications, circuits should be validated under conditions mimicking the final application environment, as performance can vary significantly across different growth phases and media conditions. Best practices include: (1) characterizing parts individually before circuit assembly; (2) using integrated genomic landing pads rather than plasmids for final implementations to enhance stability; (3) implementing control circuits lacking functional elements to distinguish burden effects from specific circuit functions; and (4) measuring both population-level and single-cell performance to identify heterogeneity issues.

Inversion-based genetic circuits provide a well-established foundation for implementing Boolean logic in cellular systems, but face fundamental limitations in scalability, predictability, and metabolic burden. Circuit compression techniques, particularly Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro), address these limitations by minimizing component count through sophisticated architectural strategies and computational design. Quantitative comparisons demonstrate that compressed circuits achieve equivalent or superior functionality with approximately 4-fold reduction in size and significantly improved performance predictability [1].

The choice between architectural approaches depends on application requirements. For simple circuits with minimal burden concerns, inversion-based implementations remain viable due to their well-characterized parts and design principles. For complex circuits, high-burden applications, or implementations requiring high predictability, compression techniques offer compelling advantages. Future directions include further expansion of orthogonal synthetic transcription factor sets, integration of CRISPR-based regulation for enhanced programmability, and development of more sophisticated computational tools that account for host-circuit interactions and evolutionary stability.

As synthetic biology advances toward more complex cellular programming, circuit compression will play an increasingly critical role in enabling implementations that are robust, predictable, and compatible with host cell physiology. The integration of computational design with modular biological parts represents a paradigm shift from intuitive, trial-and-error approaches to principled engineering of cellular behavior.

The field of synthetic biology is increasingly constrained by a fundamental challenge: as genetic circuits grow more complex to perform advanced functions, they impose a greater metabolic burden on host cells, which limits their functionality and reliability [1]. Circuit compression has emerged as a critical strategy to address this limitation by reducing the number of genetic parts required to implement a given logical operation [11]. Among competing approaches, Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) has established itself as a platform technology that leverages synthetic transcription factors (TFs) and cognate synthetic promoters to achieve unprecedented circuit compression [1]. Unlike traditional inversion-based genetic circuits that rely on cascading NOT/NOR gates, T-Pro utilizes engineered repressor and anti-repressor transcription factors that support coordinated binding to cognate synthetic promoters, significantly reducing component count while expanding computational capacity [1]. This paradigm shift enables the implementation of complex decision-making programs in living cells with applications ranging from biomanufacturing and metabolic engineering to biocontainment and therapeutic development [11].

The compression achieved by T-Pro becomes increasingly valuable as circuit complexity scales. While traditional genetic circuits require extensive part counts to implement multi-input Boolean operations, T-Pro facilitates the development of compressed higher-order circuits that maintain functionality with significantly reduced genetic footprint [1]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of T-Pro against alternative circuit design methodologies, examining quantitative performance metrics, experimental validation, and implementation requirements to guide researchers in selecting appropriate circuit compression strategies for their specific applications.

Comparative Analysis of Circuit Compression Platforms

Performance Metrics and Compression Efficiency

Table 1: Comparison of Circuit Compression Platforms

| Platform | Circuit Compression Ratio | Input Economy | Implementation Complexity | Scalability to Multi-Input |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-Pro | ~4x reduction vs. standard [1] | High (1-INPUT, 2-OUTPUT) [11] | Moderate | Excellent (3-input demonstrated) [1] |

| Classical Inversion-Based | Baseline | Low | Low | Limited by resource burden [1] |

| CRISPR-Based | Moderate | Moderate | High | Good but requires multiple guides |

| Quantum-Inspired T-Pro | Highest (fewer INPUTs relative to OUTPUTs) [11] | Highest (2-INPUT, 4-OUTPUT) [11] | High | Excellent with specialized design |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison for 3-Input Circuits

| Platform | Part Count | Prediction Error | Metabolic Burden | Truth Table Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-Pro | Minimal (compressed) [1] | <1.4-fold [1] | Low | 256 Boolean operations [1] |

| Classical Architecture | 4x more than T-Pro [1] | Not systematically quantified | High | Limited by practical constraints |

| Community-Level Platforms | Distributed | Prone to fluctuation [11] | Variable | Limited to population-level logic |

Key Differentiators of T-Pro Technology

T-Pro represents a fundamental departure from conventional genetic circuit design through several key innovations. The platform employs synthetic bidirectional promoters regulated by synthetic transcription factors to construct 1-INPUT, 2-OUTPUT logical operations, achieving what researchers have termed biological QUBIT and PAULI-X logic gates [11]. This quantum-inspired approach enables reversible logic wherein each OUTPUT state can be mapped to a specific INPUT state, dramatically increasing information transfer efficiency in genetic circuits [11]. Unlike population-level systems that require community interactions and are prone to instability due to fluctuation, T-Pro operates at the single-cell level, providing greater reliability and precision [11].

The platform's wetware consists of orthogonal sets of synthetic transcription factors responsive to different inducters (IPTG, D-ribose, and cellobiose), enabling the systematic construction of 3-input Boolean logical operations encompassing 256 distinct truth tables [1]. Recent research has expanded this wetware through the engineering of CelR-based anti-repressors that maintain orthogonality while providing additional regulatory capacity [1]. The algorithmic enumeration software developed alongside this wetware can identify maximally compressed circuit architectures from a combinatorial space of >100 trillion putative circuits, guaranteeing the most efficient implementation for any given truth table [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

T-Pro Circuit Implementation Workflow

The experimental implementation of T-Pro circuits follows a structured workflow beginning with user-defined truth tables and culminating in performance validation. Researchers first define the desired logical operation as a truth table, which serves as input to specialized enumeration software that identifies the most compressed circuit architecture from combinatorial possibilities [1]. Following computational design, specific genetic parts are selected from the T-Pro toolkit, including appropriate repressor/anti-repressor combinations and cognate synthetic promoters [1]. These components are then assembled using Golden Gate Assembly with BsaI-HF v2 or BsmBI-HF v2 kits, depending on the specific components [11]. The assembled circuits are transformed into chemically competent E. coli cells (typically strain 3.32 with genotype lacZ13, lacI22, LAM−, el4−, relA1, spoT1, and thiE1) [11]. Transformed cells are cultured in M9 minimal media supplemented with appropriate inducers (IPTG, d-ribose, or cellobiose at 10 mM concentrations), followed by flow cytometry analysis to quantify circuit performance using fluorescent reporters (sfGFP, mCherry, tagBFP, phiYFP) [11].

Quantum-Inspired Gate Construction

For quantum-inspired logical operations, researchers engineer synthetic bidirectional promoters that facilitate transcription of dual-state OUTPUTs [11]. These gates implement single-INPUT transcriptional control through complementary synthetic repressor and anti-repressor transcription factors from the T-Pro toolkit [11]. The fundamental biological QUBIT operation is designed such that each INPUT state maps to a unique dual-state OUTPUT vector: |0〉 = [1,0] when INPUT is 0, and |1〉 = [0,1] when INPUT is 1 [11]. These fundamental units can be layered to form operations of higher complexity, such as FEYNMAN and TOFFOLI gates, enabling the construction of multi-INPUT multi-OUTPUT biological programs with superior INPUT economy [11]. The 2-INPUT, 4-OUTPUT quantum operation utilizes the entire permutation INPUT space, dramatically increasing information density compared to classical genetic circuits [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for T-Pro Implementation

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factors | Engineered repressors/anti-repressors for circuit computation | LacI/GalR family variants with alternate DNA recognition domains [1] |

| Synthetic Promoters | Cognate regulatory elements responding to synthetic TFs | Tandem operator designs for coordinated TF binding [1] |

| Reporter Plasmids | Circuit output measurement | pZS*22-sfGFP with pSC101 origin (copy number 3-5/cell) [11] |

| TF Expression Plasmids | Synthetic transcription factor expression | pLacI plasmid with p15a origin (copy number 20-30/cell) [11] |

| Inducer Compounds | Circuit input signals | IPTG (10 mM), d-ribose (10 mM), cellobiose (10 mM) [11] |

| Assembly Systems | Circuit construction | Golden Gate Assembly (BsaI-HF v2, BsmBI-HF v2 kits) [11] |

Technical Implementation and Pathway Architecture

The core architecture of T-Pro circuits centers on the interaction between synthetic transcription factors and cognate synthetic promoters [1]. These components form the fundamental building blocks of all T-Pro circuits, whether implementing basic Boolean operations or advanced quantum-inspired logic. The synthetic transcription factors include both repressors and anti-repressors, which can be abstracted as BUFFER and NOT logic gates, respectively [11]. When these transcription factors are deployed to regulate genetic architectures composed of cognate synthetic promoters, they form complete sets of compressed Boolean logical operations that serve as the fundamental decision-making units of cellular programs [11]. The recent expansion to 3-input Boolean logic was enabled by engineering CelR-based anti-repressors that are responsive to cellobiose and orthogonal to existing IPTG and D-ribose responsive systems [1]. These components interact through coordinated binding to tandem operator sites in the synthetic promoters, enabling complex logic with minimal genetic footprint [1].

The platform's efficiency stems from its input economy - the ability to control multiple OUTPUTs with fewer INPUTs compared to classical systems [11]. A notable example is the 2-INPUT, 4-OUTPUT quantum operation that utilizes the entire permutation INPUT space [11]. This efficient architecture reduces the resource burden on chassis cells while expanding computational capacity, addressing a fundamental constraint in synthetic biology [1]. The platform has been successfully paired with recombinase-based memory operations that enable truth table remapping between disparate logic gates, such as converting a QUBIT operation to an antithetical PAULI-X operation in situ [11]. This integration of memory and logic represents a significant advancement toward intelligent biological systems capable of complex decision-making.

Applications and Future Directions

The compression efficiency of T-Pro opens new possibilities for applications that require complex decision-making in resource-limited cellular environments. In biomanufacturing, multi-product pathways can be regulated with precision using fewer genetic resources, minimizing metabolic burden while maintaining productivity [11]. For metabolic engineering, the platform enables branched-pathway control with efficient input economy, allowing dynamic regulation of flux through competing pathways [11] [1]. The technology shows particular promise in therapeutic applications, where circuit complexity must be balanced against cellular resource constraints to maintain functionality in clinical settings [11]. Additionally, the platform's capacity for implementing biological security systems through novel biocontainment strategies represents an emerging application area [12].

Future development of T-Pro focuses on expanding both wetware and software components. Current research aims to develop novel anti-repressor variants from the LacI/GalR family to further expand the regulatory toolkit available for constructing modular and orthogonal gene circuits [12]. Complementary software development focuses on computational frameworks for designing compressed higher-order genetic circuits that leverage these expanded anti-repressor biosensors [12]. The integration of predictive modeling with part performance data has already demonstrated remarkable accuracy, with prediction errors below 1.4-fold for >50 test cases [1]. As these tools mature, T-Pro is positioned to enable increasingly sophisticated cellular programming while minimizing the genetic footprint, ultimately advancing the frontier of synthetic biology applications across biotechnology, medicine, and biological computing.

In the field of synthetic biology, the construction of sophisticated genetic circuits is often hampered by a fundamental limitation: as complexity increases, so does the metabolic burden on the host cell, ultimately limiting functional capacity. Traditional genetic circuit design, often reliant on inversion-based architectures (e.g., NOT/NOR gates), requires a large number of genetic parts to implement complex logic, making quantitative prediction and scalability challenging [1]. This "synthetic biology problem" describes the growing discrepancy between qualitative design and quantitative performance prediction.

Circuit compression has emerged as a critical strategy to overcome these limitations. It refers to the design of genetic circuits that achieve higher-state decision-making with a minimal genetic footprint. The Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) platform represents a significant advance in this area. Instead of using inversion, T-Pro leverages engineered synthetic transcription factors (TFs) and cognate synthetic promoters to build compressed circuits, enabling the implementation of complex Boolean logic with far fewer components and a more predictable performance profile [1]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of T-Pro's core components and their performance against alternative approaches.

Core Component Engineering in T-Pro

Synthetic Transcription Factors: Repressors and Anti-Repressors

The T-Pro platform utilizes a set of engineered, ligand-responsive synthetic transcription factors that form the active processing units of the genetic circuits. These TFs are designed to be orthogonal, meaning they operate independently without cross-talk, which is essential for building multi-input systems.

- Repressor TFs: These proteins bind to their cognate synthetic promoter in the absence of an input ligand, thereby repressing transcription. The presence of the ligand induces a conformational change that causes the repressor to release from the DNA, allowing gene expression to occur.

- Anti-Repressor TFs: A key innovation of T-Pro, anti-repressors are engineered variants that perform a NOT/NOR operation with fewer components. They are designed to bind to their cognate promoter and activate transcription only in the absence of the input ligand. The presence of the ligand prevents DNA binding, turning expression off [1].

The wetware for 3-input T-Pro biocomputing is built upon three orthogonal sets of synthetic TFs, responsive to different input signals. The table below details these component sets.

Table 1: Orthogonal Synthetic Transcription Factor Sets in T-Pro

| Input Signal | TF Scaffold | Core Type | Key Engineered Variants (ADR Domains) | Function in Circuit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPTG | LacI-derived | Repressor & Anti-Repressor | Not Specified in Detail [1] | 1st Input Signal |

| D-ribose | RhaR-derived | Repressor & Anti-Repressor | Not Specified in Detail [1] | 2nd Input Signal |

| Cellobiose | CelR-derived (E+TAN) | Repressor & Anti-Repressor | EA1ADR, EA2ADR, EA3ADR (ADR = TAN, YQR, NAR, HQN, KSL) [1] | 3rd Input Signal |

Synthetic Promoters

The synthetic promoters in T-Pro are engineered DNA sequences that contain specific operator sites for the coordinated binding of the synthetic TFs. These promoters are designed to be activated or repressed based on the combinatorial state of the TFs in the system. A critical feature is the tandem operator design, which allows multiple TFs to interact with a single promoter, facilitating complex logic in a compressed space [1]. The identity of the operator sequence is determined by the Alternate DNA Recognition (ADR) domain of the bound TF, creating a specific protein-DNA interaction pair.

Engineering Workflow for a Novel Anti-Repressor

The development of the cellobiose-responsive anti-repressors illustrates the systematic protocol for expanding the T-Pro toolkit.

Figure 1: The process of engineering a synthetic anti-repressor transcription factor, involving site-directed and random mutagenesis followed by high-throughput screening.

Methodology Details:

- Selection of Repressor Scaffold: A high-performing repressor TF (e.g., the E+TAN repressor responsive to cellobiose) is selected based on its dynamic range and ON-state expression level [1].

- Super-Repressor Generation: Site saturation mutagenesis is performed at a key amino acid position (e.g., position 75 on CelR) to create a "super-repressor" variant that retains DNA binding but becomes insensitive to the input ligand. The L75H mutant was identified to have this desired phenotype [1].

- Anti-Repressor Library Creation: The super-repressor gene is used as a template for error-prone PCR (EP-PCR) at a low mutational rate to generate a large library of variants (~10^8 clones) [1].

- High-Throughput Screening: The variant library is screened using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to isolate clones exhibiting the anti-repressor phenotype (i.e., gene expression is ON without ligand and OFF with ligand) [1].

- Functional Expansion: Unique anti-repressor hits (e.g., EA1TAN, EA2TAN, EA3TAN) are then equipped with a set of additional ADR domains, creating a complete set of orthogonal TFs that recognize different synthetic promoter sequences [1].

Comparative Performance Analysis

T-Pro vs. Canonical Inversion-Based Circuits

The primary advantage of T-Pro becomes clear when its performance is compared directly with traditional, inversion-based genetic circuits. The following table summarizes a quantitative comparison based on data from the development of 3-input Boolean logic circuits [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison: T-Pro vs. Canonical Inversion Circuits

| Feature | T-Pro Compression Circuits | Canonical Inversion Circuits | Improvement/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit Size (Part Count) | ~4x smaller on average [1] | Baseline | Reduced metabolic burden, increased design capacity. |

| Boolean Implementation | Direct via anti-repressors & coordinated promoter binding [1] | Requires cascaded NOT/NOR gates [1] | Fewer parts and regulatory steps needed for the same logic. |

| Quantitative Prediction Error | Average error < 1.4-fold across >50 test cases [1] | Not explicitly stated, but "design-by-eye" is noted as untenable [1] | Enables prescriptive, predictable circuit design. |

| Software-Guided Design | Algorithmic enumeration guarantees minimal circuit design [1] | Largely intuitive or labor-intensive trial-and-error [1] | Scalable and systematic for complex circuits. |

| Demonstrated Applications | Synthetic memory, metabolic pathway control [1] | N/A | Proven in complex, functional biological programs. |

Conceptual Comparison of Circuit Architectures

The core difference between T-Pro and inversion-based circuits lies in their fundamental architecture for implementing logic. The following diagram illustrates this conceptual contrast.

Figure 2: A conceptual comparison of a canonical inversion-based circuit (top) implementing a NOR logic, requiring multiple promoters and repressors, versus a compressed T-Pro circuit (bottom) achieving the same logic directly at a single synthetic promoter through coordinated TF binding.

Experimental Protocols for T-Pro Circuit Design

The predictive design of T-Pro circuits relies on a combination of advanced wetware and dedicated software workflows. The key experimental and computational steps are outlined below.

Algorithmic Enumeration for Circuit Compression

Scaling to 3-input logic (256 distinct Boolean operations) makes intuitive circuit design impossible. To address this, a dedicated software algorithm was developed to guarantee the identification of the most compressed circuit for any given truth table.

Methodology:

- Generalized Component Modeling: Synthetic TFs and promoters are modeled abstractly to allow for a large number of orthogonal protein-DNA interactions [1].

- Circuit Representation: A circuit is modeled as a directed acyclic graph, where nodes represent components and edges represent regulatory interactions [1].

- Systematic Enumeration: The algorithm systematically enumerates all possible circuits in sequential order of increasing complexity (i.e., part count) [1].

- Optimization and Selection: The first circuit generated that matches the desired truth table is, by definition, the most compressed version. This ensures a minimal genetic footprint for any desired operation [1].

Workflow for Predictive Circuit Design

The end-to-end process for designing a T-Pro circuit with prescriptive quantitative performance involves the following integrated steps:

- Truth Table Definition: The desired higher-state decision-making logic is defined as a Boolean truth table.

- Circuit Synthesis: The algorithmic enumeration software is used to generate the most compressed DNA sequence that implements the logic.

- Context-Aware Modeling: The software uses workflows that account for genetic context (e.g., Ribosome Binding Site strength, gene order) to predict quantitative expression levels of all components [1].

- Construction and Validation: The designed circuit is synthesized and assembled in the chassis cell. Its performance is measured and compared to predictions, with an average error of less than 1.4-fold [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers aiming to implement or build upon the T-Pro platform, the following table catalogs the essential research reagents and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for T-Pro Circuit Implementation

| Reagent / Material | Function and Role in T-Pro |

|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factors (Repressor/Anti-Repressor sets) | Engineered proteins responsive to IPTG, D-ribose, and cellobiose; the core processing elements that execute logical operations [1]. |

| T-Pro Synthetic Promoters (Tandem Operator Design) | Engineered DNA sequences that are regulated by the synthetic TFs; the interface where logical computation is performed [1]. |

| Orthogonal Inducer Molecules (IPTG, D-ribose, Cellobiose) | Small molecule inputs that serve as the primary signals to trigger changes in the state of the genetic circuit [1]. |

| Fluorescence Reporter Genes (e.g., GFP) | Genes encoding fluorescent proteins used to quantitatively measure the output and performance of the genetic circuits via flow cytometry or plate readers [1]. |

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | A kit for performing random mutagenesis, essential for the engineering of novel anti-repressor TFs from a super-repressor template [1]. |

| Flow Cytometer (FACS) | An instrument for high-throughput screening and sorting of cell libraries based on fluorescence, critical for isolating functional TF variants [1]. |

| Algorithmic Enumeration Software | Custom software for generating the most compressed genetic circuit design for any given Boolean truth table [1]. |

| Chassis Cells (e.g., E. coli) | The host microorganisms in which the genetic circuits are implemented and tested [1]. |

Synthetic biology aims to reprogram cellular decision-making by implementing predictable logic operations within living cells. The construction of biologic gates—including AND, OR, and NOT functions—using genetic components like promoters, transcription factors, and coding DNA represents a fundamental step toward cellular reprogramming for therapeutic and biotechnological applications [13]. As the field progresses, a critical challenge has emerged: increasing circuit complexity imposes significant metabolic burden on host cells, limiting practical implementation [1]. This review examines the evolution from 2-input to 3-input Boolean operations, focusing specifically on circuit compression techniques that minimize genetic footprint while maintaining computational capability.

The transition from 2-input to 3-input logic represents more than a simple incremental improvement—it marks a fundamental shift in biological computing capacity. While 2-input systems can process 4 possible input states (00, 01, 10, 11) corresponding to 16 Boolean logic operations, 3-input systems expand this to 8 possible input states (000-111) and 256 distinct Boolean operations [1]. This expanded state space enables higher-level decision-making with applications ranging from precision therapeutics to metabolic engineering. We objectively compare the performance of next-generation compression technologies against conventional approaches, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies for implementation.

Comparative Analysis: Circuit Compression Technologies

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Genetic Circuit Architectures

| Technology | Circuit Footprint | Input Capacity | Boolean Operations | Metabolic Burden | Quantitative Predictability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Inversion-Based | Large (Modular gates connected sequentially) | 2-input | 16 possible | High | Limited; requires labor-intensive optimization |

| T-Pro Compression | ~4x smaller than canonical circuits | 3-input | 256 possible | Significantly reduced | High (average error <1.4-fold for >50 test cases) |

| Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) with Anti-Repressors | Minimal (Fewer promoters/regulators) | Scalable to higher inputs | All 2-input and 3-input operations | Minimal | Prescriptive quantitative performance |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for 3-Input T-Pro Circuits

| Parameter | T-Pro 3-Input Performance | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Signal Systems | IPTG, D-ribose, and cellobiose-responsive TF sets | Engineered CelR-based anti-repressors with dynamic regulation |

| Circuit Compression | Approximately 4x size reduction vs. canonical circuits | Demonstrated across multiple circuit designs |

| Prediction Accuracy | Average error below 1.4-fold | Validated in >50 test cases |

| Application Range | Biocomputing to metabolic pathway control | Predictive design of recombinase genetic memory and metabolic flux |

Methodology: Experimental Protocols for 3-Input Circuit Construction

T-Pro Anti-Repressor Engineering Workflow

The expansion from 2-input to 3-input Boolean logic requires developing additional orthogonal repressor/anti-repressor sets. The following protocol outlines the engineering of cellobiose-responsive synthetic transcription factors for 3-input T-Pro circuits [1]:

Repressor Selection: Identify synthetic transcription factors compatible with established synthetic promoter sets through synthetic alternate DNA recognition. Selection criteria prioritize dynamic range and ON-state expression level in presence of ligand (e.g., cellobiose).

Super-Repressor Generation: Create ligand-insensitive DNA-binding variants via site saturation mutagenesis. For CelR-based systems, the L75H mutation generated the ESTAN super-repressor variant.

Anti-Repressor Library Construction: Perform error-prone PCR on the super-repressor template at low mutational rates to generate variant libraries (~10⁸ diversity).

FACS Screening: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting to identify functional anti-repressors (e.g., EA1TAN, EA2TAN, EA3TAN) exhibiting the desired anti-repression phenotype.

ADR Expansion: Equip validated anti-repressors with additional alternate DNA recognition functions (EAYQR, EANAR, EAHQN, EAKSL) to expand operational range while maintaining anti-repressor functionality.

Algorithmic Enumeration for Compressed Circuit Design

Scaling to 3-input logic eliminates the possibility of intuitive circuit design due to a combinatorial space exceeding 100 trillion putative circuits [1]. The T-Pro framework employs this systematic approach:

Graph Representation: Model circuits as directed acyclic graphs where nodes represent genetic components and edges represent regulatory interactions.

Sequential Enumeration: Systematically enumerate circuits in order of increasing complexity, guaranteeing identification of the most compressed implementation for each target truth table.

Complexity Optimization: Define complexity by the number of genetic parts (promoters, genes, RBS, transcription factors), seeking minimal implementations.

Orthogonality Verification: Ensure component orthogonality through in silico screening of potential cross-talk between the three input systems (IPTG, D-ribose, cellobiose-responsive components).

Graph 1: Three-input compressed T-Pro circuit architecture. The system integrates three orthogonal signal-responsive transcription factor sets regulating a single synthetic promoter with tandem operator design, minimizing genetic footprint compared to traditional cascaded gate approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions for Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for T-Pro Circuit Implementation

| Reagent/Component | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factors | Circuit computation elements | Engineered repressors/anti-repressors responsive to IPTG, D-ribose, cellobiose |

| T-Pro Synthetic Promoters | Regulatory targets for TFs | Tandem operator designs supporting coordinated TF binding |

| Orthogonal Inducer Molecules | Input signals | IPTG, D-ribose, cellobiose (three orthogonal systems) |

| Algorithmic Design Software | Circuit enumeration | Custom software for compressed circuit identification from truth tables |

| Quantitative Prediction Workflows | Performance forecasting | Context-aware tools predicting expression with <1.4-fold error |

Case Study: Predictive Design of Genetic Memory Circuits

The T-Pro compression framework successfully demonstrated practical application in predictive design of recombinase genetic memory circuits [1]. The experimental implementation followed this protocol:

Circuit Specification: Define the desired memory behavior and corresponding truth table for the 3-input system.

Compressed Circuit Identification: Apply algorithmic enumeration to identify the minimal genetic implementation matching the specification.

Quantitative Performance Prediction: Use established workflows to predict circuit behavior before construction, including recombinase expression levels and switching thresholds.

Experimental Validation: Construct the predicted circuit and measure performance against predictions, demonstrating <1.4-fold error between predicted and observed activities.

This approach successfully controlled flux through a toxic biosynthetic pathway, highlighting how compressed circuits minimize metabolic burden while maintaining precise control over cellular functions [1].

Graph 2: Boolean network inference workflow for predictive modeling. This complementary approach uses logic programming to infer network models from transcriptomic data, enabling prediction of cellular reprogramming targets.

The evolution from 2-input to 3-input Boolean operations in biological systems represents a significant milestone in synthetic biology, enabled primarily through circuit compression technologies like Transcriptional Programming. The T-Pro framework demonstrates that increasing computational complexity need not come at the cost of increased genetic burden—properly designed compressed circuits can achieve sophisticated 3-input logic with approximately 75% reduction in component count compared to traditional implementations [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances open new possibilities in cellular programming for therapeutic applications. The availability of standardized reagent systems and predictive design tools lowers the barrier to implementation, while the expanded state space of 3-input logic enables more sophisticated decision-making algorithms for diagnostic and therapeutic applications [13] [1]. As the field progresses, further compression innovations and additional orthogonal signaling systems will continue to expand the frontiers of biological computation.

The field of synthetic biology aims to reprogram cellular functions using engineered genetic circuits. However, as circuit complexity increases, a fundamental challenge emerges: the metabolic burden imposed on host chassis cells. This burden manifests as a drain on the cell's finite resources—energy, nucleotides, amino acids, and transcriptional/translational machinery—leading to reduced growth rates and compromised circuit function [14]. The expression of heterologous genes requires host cells to allocate intracellular resources, which creates selective pressure for mutants that inactivate or lose the circuit function to gain a fitness advantage [14]. This evolutionary pressure results in culture populations being overtaken by non-functional mutants, ultimately leading to circuit failure [14].

The relationship between circuit size and metabolic burden is direct and consequential. Larger circuits with more genetic parts consume more cellular resources, imposing greater burden and accelerating the emergence of escape mutants [1] [14]. This review examines circuit compression techniques, focusing specifically on the Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) approach versus traditional inversion-based methods, to address how synthetic biologists can minimize metabolic burden while maintaining sophisticated circuit functions.

Circuit Compression Techniques: T-Pro vs. Inversion-Based Methods

Fundamental Architectural Differences

Traditional inversion-based circuits typically utilize NOR logic operations implemented through transcriptional inversion (NOT gates). This approach requires multiple promoters and regulators to implement basic logical operations, resulting in larger genetic constructs with increased part count [1]. For example, canonical inverter-type genetic circuits require approximately four times more genetic material compared to compressed alternatives [1].

In contrast, Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) represents an architectural shift that enables circuit compression. Rather than relying on inversion, T-Pro leverages engineered repressor and anti-repressor transcription factors (TFs) that coordinate binding to cognate synthetic promoters [1]. This design facilitates direct implementation of Boolean operations with significantly fewer genetic components [1]. Specifically, T-Pro utilizes synthetic anti-repressors to achieve NOT/NOR Boolean operations that require fewer promoters relative to inversion-based circuits [1].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance differences between T-Pro and inversion-based genetic circuits:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of T-Pro vs. Inversion-Based Circuits

| Parameter | T-Pro Circuits | Canonical Inversion-Based Circuits | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Circuit Size | ~1× (Baseline) | ~4× larger | Component count reduction [1] |

| Boolean Implementation | Direct via anti-repressors | Indirect via inversion | Qualitative design analysis [1] |

| Part Composition | Synthetic TFs + promoters | Multiple promoters + regulators | Genetic architecture analysis [1] |

| Prediction Error | <1.4-fold average error | Not consistently reported | Quantitative performance prediction across >50 test cases [1] |

| Metabolic Burden | Reduced | Higher | Inference from stability studies [14] |

Impact on Genetic Stability

The stability advantages of compressed circuits are quantifiable. Research has demonstrated that circuit half-life decreases exponentially with increased target gene expression level [14]. In one study, reducing circuit burden improved stability significantly, with minimized cultures showing only 3% non-producer cells compared to 96% in industrial-scale fermenters [14]. This relationship underscores why compression techniques like T-Pro that reduce part count directly address the root causes of genetic instability.

Experimental Evidence: Validating Circuit Compression Advantages

Methodology for Circuit Performance Validation

Researchers employed systematic workflows to validate T-Pro circuit compression advantages:

Wetware Expansion: Development of orthogonal synthetic transcription factor systems responsive to IPTG, D-ribose, and cellobiose [1]. This included engineering CelR-based anti-repressors (EA1TAN, EA2TAN, EA3TAN) with alternate DNA recognition functions (EAYQR, EANAR, EAHQN, EAKSL) [1].

Software Development: Creation of algorithmic enumeration-optimization software to identify minimal circuit designs from combinatorial spaces exceeding 100 trillion putative circuits [1]. This guaranteed identification of the most compressed circuit for each truth table.

Quantitative Validation: Implementation of workflows accounting for genetic context to quantify expression levels, with testing across numerous genetic circuits to verify prediction accuracy [1].

Key Experimental Findings

Experimental data from compression circuit implementation reveals significant advantages:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for Compression Circuits

| Application | Performance Metric | Result | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-input Boolean Logic | Circuit size reduction | 4× smaller than canonical circuits | Average reduction across designs [1] |

| Quantitative Prediction | Model accuracy | <1.4-fold average error | Across >50 test cases [1] |

| Metabolic Engineering | Flux control | Precise setpoints achieved | Dynamic regulation of toxic pathways [1] |

| Genetic Memory | Recombinase activity | Predictive design successful | Application to synthetic memory circuits [1] |

The experimental data demonstrates that T-Pro compression circuits achieve high-predictability design while minimizing genetic footprint. This balance is crucial for applications where persistent function is required, such as in metabolic engineering or therapeutic circuits.

Research Reagents and Experimental Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents

The table below catalogues key reagents required for implementing and testing circuit compression approaches:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Circuit Compression Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Variants / Types |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factors | Core circuit components for transcriptional control | Repressors: E+TAN; Anti-repressors: EA1TAN, EA2TAN, EA3TAN [1] |

| Alternate DNA Recognition (ADR) Domains | Enable orthogonal promoter recognition | TAN, YQR, NAR, HQN, KSL [1] |

| Inducer Molecules | Activate orthogonal TF systems | Cellobiose, IPTG, D-ribose [1] |

| Synthetic Promoters | Engineered regulatory elements for T-Pro | Tandem operator designs [1] |

| Reduced-Genome Strains | Enhance genetic stability | E. coli ΔIS elements, Pseudomonas putida KT2440 variants [14] |

| Fluorescence Reporters | Circuit output measurement | GFP and variants [14] |

Specialized Experimental Systems

- Stability Assessment Platforms: Microfluidic devices and microencapsulation systems that minimize population sizes to suppress mutant emergence [14]

- Directed Evolution Systems: For host optimization to enhance circuit tolerance [14]

- Population Control Circuits: Rock-paper-scissors logic systems for ecological containment of mutants [14]

Visualizing Circuit Architectures and Experimental Workflows

T-Pro Circuit Compression Mechanism

Metabolic Burden and Genetic Stability Relationship

Experimental Workflow for Circuit Validation

Applications and Implementation Guidelines

Practical Applications in Biotechnology

Circuit compression techniques have demonstrated significant utility in multiple biotechnology domains:

Metabolic Engineering: T-Pro circuits enable dynamic regulation of metabolic networks, balancing the trade-off between cell growth and product synthesis [8]. Implementation of compressed circuits for flux control in toxic biosynthetic pathways has achieved precise setpoints without compromising viability [1].

Biocomputing and Diagnostics: Compressed circuits facilitate higher-state decision-making capabilities within cellular frameworks, enabling sophisticated biosensing and diagnostic applications [1].

Therapeutic Development: The enhanced genetic stability of compressed circuits makes them promising candidates for long-term therapeutic applications where persistent circuit function is essential [14].

Implementation Recommendations

For researchers implementing circuit compression strategies: