CAR-T Cell Engineering: From Foundational Principles to Next-Generation Clinical Protocols

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell engineering protocols, tracing the evolution from foundational concepts to cutting-edge clinical applications.

CAR-T Cell Engineering: From Foundational Principles to Next-Generation Clinical Protocols

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell engineering protocols, tracing the evolution from foundational concepts to cutting-edge clinical applications. It details the structural components and modular design of synthetic CAR receptors, established manufacturing workflows for hematologic malignancies, and critical troubleshooting for challenges like T-cell exhaustion and cytokine release syndrome. The content further explores advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses of novel engineering strategies—including logic-gated, armored, and allogeneic CAR-T cells—that are pushing the boundaries in solid tumors. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current literature and clinical trial data to serve as a methodological guide and innovation roadmap for the next generation of cancer immunotherapies.

The Architecture and Evolution of CAR-T Cells: Deconstructing the Engineering Blueprint

Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs) are synthetic receptors designed to redirect immune effector cells, primarily T cells, to recognize and eliminate cancer cells with specified surface antigens. The modular architecture of a CAR allows for the customization of its functional properties, making the understanding of its core structural domains fundamental to cancer immunotherapy research [1] [2]. These engineered receptors typically fuse an extracellular antigen-recognition domain to intracellular T-cell signaling modules, enabling Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC)-independent T-cell activation [3]. This application note details the core structural domains of a CAR, provides protocols for their evaluation, and visualizes the critical relationships and workflows to aid in the rational design of CAR constructs for preclinical research.

Core Structural Domains of a CAR

The functional efficacy of a CAR is dictated by the synergistic operation of its four core domains: the antigen-binding domain, the hinge region, the transmembrane domain, and the intracellular signaling domain [2]. The structure and selection of each component directly influence the stability, signaling potency, and ultimate success of the CAR-T cell product.

Antigen-Binding Domain

The antigen-binding domain, typically a single-chain variable fragment (scFv), confers specificity to the target antigen. Derived from the variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) chains of a monoclonal antibody connected by a flexible linker, the scFv enables the CAR to bind directly to cell surface antigens without the need for antigen presentation by MHC molecules [1] [2]. Beyond simple recognition, the affinity of the scFv is a critical parameter. A high affinity must be balanced to ensure effective tumor cell recognition while avoiding activation-induced cell death or excessive on-target, off-tumor toxicities that can occur when the target antigen is expressed on healthy tissues [2]. The epitope location and target antigen density on the tumor cell surface are also key considerations that influence CAR functionality [2].

Hinge/Spacer Region

The hinge or spacer is an extracellular structural region that links the antigen-binding domain to the transmembrane domain. Its primary functions are to provide flexibility, overcome steric hindrance from the cell membrane or complex glycans, and allow sufficient intercellular distance for the formation of a stable immunological synapse [2]. The length and composition of the hinge (commonly derived from CD8α, CD28, or IgG Fc regions) significantly impact CAR expression, signaling strength, and epitope recognition [2]. The optimal spacer length is often determined empirically and is dependent on the position of the target epitope; for instance, membrane-proximal epitopes may require long spacers, while membrane-distal epitopes are more effectively targeted with short hinges [2]. Researchers should note that IgG-derived spacers can interact with Fcγ receptors on innate immune cells, potentially leading to off-target activation and CAR-T cell depletion in vivo; this can be mitigated by selecting alternative spacers or engineering the Fc portion to eliminate binding [2].

Transmembrane Domain

The transmembrane (TM) domain is a hydrophobic alpha helix that anchors the CAR to the T cell membrane. While its primary role is structural, the choice of TM domain can influence CAR expression levels, stability, and function [1] [2]. The TM domain can mediate CAR dimerization and functional interaction with endogenous signaling molecules. For example, a CD3ζ-derived TM domain may facilitate incorporation of the CAR into the native TCR complex, potentially enhancing signaling but possibly at the cost of decreased receptor stability compared to a CD28 TM domain [2]. The TM domain is frequently selected to match the extracellular spacer or intracellular co-stimulatory domains for compatibility, but its impact on overall CAR function warrants careful consideration during the design phase [2].

Intracellular Signaling Domain

The intracellular domain is the functional engine of the CAR, responsible for transmitting activation signals upon antigen binding. Its design has evolved through several generations, outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Evolution of CAR Intracellular Signaling Domains

| Generation | Signaling Components | Key Features & Functional Consequences | Representative Targets in Clinical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | CD3ζ only [1] | Provides Signal 1 (primary T-cell activation); limited persistence & cytokine secretion; requires exogenous IL-2 [1] | CD19 [1] |

| Second | CD3ζ + one co-stimulatory domain (e.g., CD28 or 4-1BB) [1] | Provides both Signal 1 and Signal 2; enhances proliferation, cytokine production, cytotoxicity, and in vivo persistence [1] [2]. CD28ζ favors potent activation; 4-1BBζ favors persistence [1]. | CD19 (Kymriah, Yescarta) [4] |

| Third | CD3ζ + two or more co-stimulatory domains (e.g., CD28+4-1BB or CD28+OX40) [1] | Aims to augment potency with stronger cytokine production and killing ability; clinical outcomes not consistently superior to 2nd gen [1]. | CD20, HER2 [1] |

| Fourth (TRUCK) | Second-gen base + inducible cytokine (e.g., IL-12) [1] | "Armored CARs" modify the tumor microenvironment (TME); recruit/activate innate immune cells; can target antigen-negative cancer cells [1]. | In clinical trials for solid tumors [5] |

Advanced Engineering and Universal CAR Systems

To address challenges like antigen escape, toxicity, and complex manufacturing, advanced universal CAR (UniCAR) systems have been developed. These platforms split the conventional CAR into two separate components: a universal signaling module expressed on the T cell and a soluble switch module that directs specificity [6]. This design allows for control over the timing, intensity, and target of the CAR-T cell response. The switch molecule serves as a bridge between the UniCAR T cell and the tumor cell, and its administration can be titrated or interrupted to fine-tune anti-tumor activity or mitigate side effects [6]. Examples include the SUPRA CAR system, which uses leucine zipper pairing, and the biotin-binding immunoreceptor (BBIR) system, which utilizes high-affinity biotin-avidin interaction [6]. This modular approach enables one batch of UniCAR T cells to be redirected against multiple tumor antigens without genetic re-engineering, offering a versatile and potentially more cost-effective strategy [6].

Experimental Protocols for CAR-T Cell Evaluation

Protocol: In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay (Standard Chromium-51 Release Assay)

This protocol measures the ability of CAR-T cells to lyse antigen-expressing target cells.

Preparation of Target Cells:

- Harvest and wash antigen-positive and antigen-negative (control) tumor cell lines (e.g., MC38-CEA vs. MC38).

- Resuspend cells at 1x10^6 cells/mL in culture medium and label with 100 µCi of Na₂⁵¹CrO₄ for 1 hour at 37°C with occasional gentle mixing.

- Wash cells three times with PBS to remove unincorporated radioactivity and resuspend in complete RPMI-1640 medium at 1x10^5 cells/mL.

Preparation of Effector CAR-T Cells:

- Thaw or harvest expanded CAR-T cells and control T cells (e.g., non-transduced or mock-transduced).

- Count and serially dilute the cells in complete medium to create effector-to-target (E:T) ratios (e.g., 40:1, 20:1, 10:1, 5:1) in a 96-well U-bottom plate.

Co-culture and Assay Execution:

- Add 100 µL of labeled target cells (1x10^4 cells) to each well containing effector cells.

- Include controls for spontaneous release (target cells + medium only) and maximum release (target cells + 1% Triton X-100).

- Centrifuge the plate briefly and incubate for 4-6 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- After incubation, centrifuge the plate and transfer 50 µL of supernatant from each well to a LumaPlate.

- Measure radioactivity using a gamma counter.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage of specific lysis using the formula:

% Specific Lysis = (Experimental Release – Spontaneous Release) / (Maximum Release – Spontaneous Release) x 100. - Plot % specific lysis against E:T ratios for CAR-T and control cells. Effective CAR-T cells should show potent, antigen-specific lysis.

- Calculate the percentage of specific lysis using the formula:

Protocol: Flow Cytometric Analysis of CAR Expression and T-cell Phenotype

This protocol is used to determine transduction efficiency and characterize the resulting CAR-T cell product.

Staining for CAR Expression:

- For CARs with an extracellular tag (e.g., a truncated EGFR), use a biotinylated or fluorophore-conjugated protein (e.g., recombinant EGF or an anti-tag antibody) followed by a secondary staining reagent if needed [3].

- For CARs where the scFv is accessible, use a recombinant target antigen protein fused to a marker like Fc or fluorescent protein.

- Resuspend 0.5-1x10^6 CAR-T cells in FACS buffer (PBS + 2% FBS). Incubate with the detection reagent for 30 minutes on ice in the dark. Wash twice with FACS buffer.

Immunophenotyping of T-cell Subsets:

- Perform surface staining with antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, and memory markers (e.g., CD45RO, CD62L, CCR7).

- For intracellular staining of exhaustion markers (e.g., PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3), use a fixation/permeabilization kit according to the manufacturer's instructions after surface staining.

- Incubate with antibodies for 30 minutes on ice, wash, and resuspend in FACS buffer for acquisition.

Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire data on a flow cytometer. Use fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls to set positive gates accurately.

- Analyze data to determine the percentage of CAR-positive cells and the distribution of T-cell subsets (naive, central memory, effector memory, terminally differentiated) and exhaustion markers within the CAR+ population.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CAR-T Cell Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in CAR-T Cell Development | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors (Lentivirus/Retrovirus) [1] [3] | Stable genomic integration and long-term CAR expression. | Standard method for generating persistent clinical CAR-T products. |

| mRNA Electroporation [3] | Transient CAR expression; mitigates genotoxicity risk. | Ideal for testing novel scFvs in vitro or for targets where safety concerns are high. |

| Sleeping Beauty Transposon System [3] | Non-viral, cost-effective method for stable gene transfer. | An alternative to viral transduction; requires optimization for high efficiency. |

| Recombinant Antigen Protein | Detection of CAR surface expression via flow cytometry. | Quality control of CAR-T product pre-infusion. |

| Cytokine Detection Assays (ELISA/ELISpot) | Quantification of cytokine secretion (IFN-γ, IL-2) upon antigen stimulation. | Measurement of CAR-T cell functional activation. |

| Automated Manufacturing Platforms (e.g., Cocoon, CliniMACS Prodigy) [7] | Closed, automated system for cell washing, activation, transduction, and expansion. | Standardizing and scaling CAR-T production for clinical applications. |

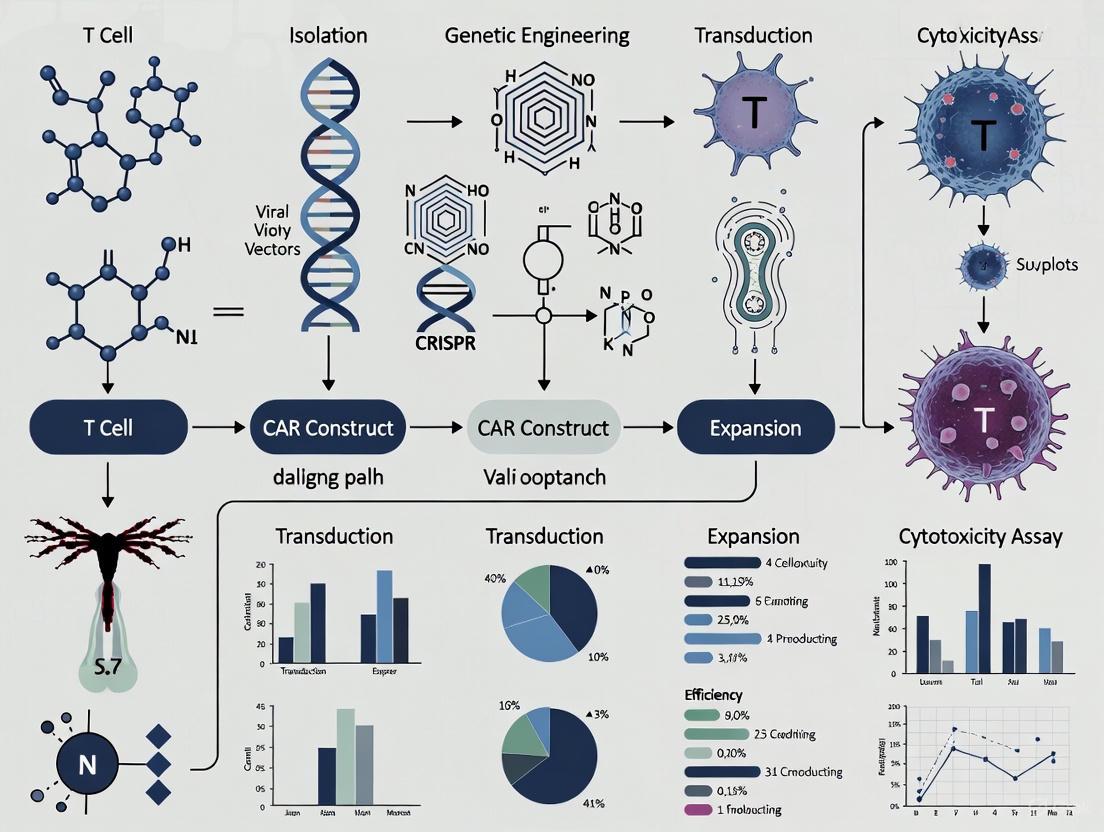

CAR Structure and Engineering Workflow Visualizations

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts of CAR architecture and the experimental workflow for their evaluation.

CAR Domain Architecture and Signaling

Diagram 1: Core CAR Structure and Signaling Output. This diagram depicts the modular domains of a second-generation CAR. Antigen binding initiates intracellular signaling through primary (CD3ζ) and co-stimulatory (e.g., CD28/4-1BB) domains, leading to T-cell effector functions.

CAR-T Cell Functional Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: CAR-T Cell Engineering and Validation Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key stages in generating and validating CAR-T cells, from construct design to in vitro and in vivo functional assessment.

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a paradigm shift in cancer immunotherapy, enabling the direct targeting of tumor antigens through engineered synthetic receptors. Since the concept was first proposed in 1987 and independently illustrated in 1989, CAR technology has undergone remarkable evolution through five distinct generations, each addressing critical limitations in persistence, efficacy, and safety [8] [9]. This evolution has transformed CAR-T cells from research curiosities to powerful clinical tools with proven efficacy against hematological malignancies, culminating in the first FDA approvals in 2017 [8] [10]. The structural refinements across generations have progressively enhanced T-cell activation, persistence, and tumor eradication capabilities while introducing sophisticated control mechanisms. This application note provides a comprehensive technical overview of CAR design generations, detailing their structural characteristics, signaling mechanisms, and experimental protocols to support researchers in developing next-generation CAR-T therapies.

Structural Foundations of CAR Design

The foundational architecture of all CAR constructs consists of three core domains: an extracellular antigen recognition domain, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular signaling domain [9]. The extracellular domain typically features a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from monoclonal antibodies, though alternative binding scaffolds like nanobodies, DARPins, and natural ligands are increasingly employed [10] [9]. This domain is connected via a hinge region that provides flexibility and access to target epitopes. The transmembrane domain anchors the receptor in the cell membrane and is often derived from CD8α, CD28, or CD4. The intracellular signaling domain initiates T-cell activation and has been systematically enhanced across generations with additional costimulatory domains and signaling modules [8] [9].

Table 1: Core Structural Components of CAR Constructs

| Domain | Key Components | Function | Common Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular | scFv, Nanobodies, Ligands | Antigen recognition | Antibody VH and VL regions [9] |

| Hinge/Spacer | Immunoglobulin domains | Flexibility, epitope access | CD8α, CD28, IgG [9] |

| Transmembrane | Hydrophobic alpha-helices | Membrane anchoring | CD8α, CD28, CD3ζ [9] |

| Intracellular | Signaling domains | T-cell activation, persistence | CD3ζ, CD28, 4-1BB, ICOS [8] |

The Generational Progression of CAR Designs

First-Generation CARs: Proof of Concept

First-generation CARs established the fundamental principle of redirecting T-cell specificity through a simple architecture consisting of an extracellular scFv fused directly to an intracellular CD3ζ signaling domain [8]. These receptors demonstrated that T cells could be engineered to recognize surface antigens independent of MHC restriction, triggering cytotoxicity upon target engagement [8]. However, clinical applications revealed critical limitations including poor persistence, limited expansion, and inadequate antitumor activity in vivo due to the absence of costimulatory signaling [8]. The CD3ζ domain alone provided primary activation signal but failed to sustain long-term T-cell function, leading to activation-induced cell death and limited therapeutic efficacy in early clinical trials [8] [10].

Second-Generation CARs: Clinical Breakthrough

Second-generation CARs addressed the persistence limitation by incorporating a single costimulatory domain (CD28 or 4-1BB) alongside the CD3ζ signaling domain [8] [10]. This architectural innovation provided both Signal 1 (activation) and Signal 2 (costimulation) through a single receptor, dramatically enhancing T-cell expansion, persistence, and antitumor efficacy [8]. The specific costimulatory domain incorporated significantly influenced functional properties: CD28 domains promoted rapid, robust expansion and effector function, while 4-1BB domains enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis, memory formation, and long-term persistence [11] [10]. This generation achieved remarkable clinical success in B-cell malignancies, leading to the first FDA-approved CAR-T therapies (Kymriah, Yescarta) targeting CD19 [8] [10].

Third-Generation CARs: Signal Amplification

Third-generation CARs further amplified T-cell signaling by incorporating two distinct costimulatory domains (typically CD28 plus 4-1BB or OX40) in tandem with CD3ζ [8] [10]. This design aimed to synergize the advantages of different costimulatory pathways to enhance potency, persistence, and cytokine production [10]. Preclinical studies demonstrated that third-generation CARs exhibited superior expansion and prolonged persistence compared to second-generation constructs in some CD19-targeted therapies [10]. However, concerns emerged regarding potential overactivation leading to accelerated T-cell exhaustion and increased risk of severe adverse effects, highlighting the delicate balance between enhanced efficacy and toxicity [10].

Fourth-Generation CARs (TRUCKs): Armored Engineering

Fourth-generation CARs, also termed "TRUCKs" (T cells Redirected for Universal Cytokine Killing) or "armored CARs," represent a paradigm shift from simply enhancing T-cell signaling to modifying the tumor microenvironment [11] [10]. These constructs are based on second-generation CARs but incorporate inducible cytokine expression cassettes (e.g., IL-12, IL-15, IL-18) that activate upon antigen engagement [11] [10]. These engineered cells function as "mini pharmacies" that locally release immunomodulatory cytokines to enhance the antitumor response by recruiting and activating endogenous immune cells, countering immunosuppressive factors in the tumor microenvironment, and promoting CAR-T cell survival [11]. This approach shows particular promise for solid tumors, where the immunosuppressive microenvironment presents a major barrier to CAR-T efficacy [11] [12].

Fifth-Generation CARs: Precision Control

Fifth-generation CARs represent the cutting edge of CAR engineering, incorporating cytokine receptor signaling domains (e.g., IL-2Rβ) that activate the JAK/STAT pathway upon antigen engagement [12] [10]. These constructs create an autocrine loop that enhances cell proliferation and survival while maintaining the costimulatory advantages of earlier generations [12]. Additionally, fifth-generation designs increasingly incorporate logic-gated systems, inducible suicide switches, and synthetic regulatory circuits that enable precise control over T-cell activity, potentially mitigating toxicity risks while enhancing antitumor efficacy [10]. These advanced systems represent the transition from constantly active receptors to smart therapeutics that can integrate multiple environmental signals [10].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of CAR Generations

| Generation | Intracellular Domains | Key Innovations | Clinical Status | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | CD3ζ [8] | MHC-independent targeting | Historical significance | Proof of concept | Poor persistence, limited efficacy [8] |

| Second | CD3ζ + 1 costimulatory domain (CD28 or 4-1BB) [8] [10] | Integrated costimulation | FDA-approved for hematologic malignancies [8] | Enhanced persistence and efficacy | Limited solid tumor activity, toxicity concerns [11] |

| Third | CD3ζ + 2 costimulatory domains (e.g., CD28+4-1BB) [8] [10] | Multiple costimulatory signals | Clinical trials [10] | Potentially enhanced potency | Risk of overactivation and exhaustion [10] |

| Fourth | Second-generation base + inducible cytokines [11] [10] | Local cytokine delivery | Clinical trials for solid tumors [11] | Modifies tumor microenvironment | Complex manufacturing, potential off-tissue effects [10] |

| Fifth | Second-generation base + cytokine receptor domains (e.g., IL-2Rβ) [12] [10] | JAK/STAT activation, logic gates | Preclinical and early clinical development [12] [10] | Enhanced proliferation, precision control | High design complexity, safety validation needed [10] ``` |

CAR Signaling Pathways

The intracellular signaling architecture of CAR constructs has evolved considerably across generations, with each addition enhancing T-cell activation, persistence, and functionality. First-generation CARs relied exclusively on CD3ζ-derived immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) that initiate the canonical T-cell receptor signaling cascade [8] [9]. Second-generation constructs incorporated costimulatory domains that activate distinct signaling pathways: CD28 enhances PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling for rapid effector function, while 4-1BB promotes TRAF/NF-κB signaling that supports mitochondrial biogenesis and long-term persistence [8] [10]. Third-generation CARs combine multiple costimulatory signals to potentially synergize these advantages. Fourth and fifth-generation designs introduce cytokine signaling and inducible gene expression, creating more complex regulatory networks that integrate environmental cues [11] [12] [10].

Experimental Protocols for CAR-T Cell Generation

T-Cell Isolation and Activation

Purpose: To obtain high-quality T cells from donor blood and activate them for genetic modification. Procedure: (1) Collect peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patient or donor via leukapheresis; (2) Isolate T cells using negative selection (Pan T Cell Isolation Kit) or positive selection (CD3/CD28 beads); (3) Activate T cells using anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (1 µg/mL) or Dynabeads (bead-to-cell ratio 3:1) in complete media (RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS + 2 mM L-glutamine + 1% penicillin/streptomycin + 10 mM HEPES) supplemented with IL-2 (100 IU/mL); (4) Culture at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 24-48 hours before transduction [13] [10].

CAR Gene Delivery Methods

Viral Transduction (Lentiviral/Adenoviral) Purpose: Achieve stable genomic integration and long-term CAR expression. Procedure: (1) Preload RetroNectin-coated plates (10 µg/mL) with lentiviral vectors (MOI 5-20) by centrifugation (2000 × g, 90 minutes, 32°C); (2) Seed activated T cells (1×10⁶ cells/mL) in viral supernatant; (3) Centrifuge (1000 × g, 90 minutes, 32°C); (4) Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 24 hours; (5) Replace with fresh complete media with IL-2; (6) Repeat transduction if necessary [13] [10].

Non-Viral Transfection (Electroporation) Purpose: Avoid viral vector limitations using transposon systems or mRNA. Procedure: (1) Use Sleeping Beauty or PiggyBac transposon systems with corresponding transposase; (2) Resuspend activated T cells in electroporation buffer with DNA plasmids (CAR transposon + transposase at 4:1 ratio); (3) Electroporate using optimized program (e.g., 500V, 5ms pulse for Neon system); (4) Immediately transfer to pre-warmed complete media; (5) For mRNA electroporation, use 2-5 µg mRNA with similar parameters for transient expression [13] [10].

CAR-T Cell Expansion and Validation

Purpose: Expand transduced T cells to therapeutic doses and validate CAR expression and function. Expansion Protocol: (1) Culture transduced T cells at 0.5-1×10⁶ cells/mL in complete media with IL-2 (50-100 IU/mL); (2) Monitor cell density and split every 2-3 days to maintain optimal concentration; (3) Expand for 7-14 days to achieve target cell numbers (typically 1-10×10⁸ CAR-T cells for infusion); (4) Perform analytical assessments throughout expansion [13].

Validation Assays: (1) Flow cytometry for CAR expression using protein L or target antigen staining; (2) Coculture assays with target cells to measure cytokine production (ELISA for IFN-γ, IL-2) and cytotoxicity (LDH release, real-time cell analysis); (3) Proliferation assays (CFSE dilution) following antigen stimulation; (4) Memory phenotype characterization (CD45RO, CD62L, CD27) by flow cytometry [13] [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CAR-T Cell Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, Gamma-retroviral vectors, Sleeping Beauty transposon, PiggyBac transposon, mRNA [13] [10] | CAR gene transfer | Lentiviral: High efficiency, stable integration [10]; mRNA: Transient, safer profile [13] |

| T-cell Activation | Anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies, IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, Dynabeads [13] | T-cell stimulation and expansion | CD3/CD28 beads provide strong activation signal; Cytokines influence differentiation [13] |

| Culture Media | X-VIVO 15, TexMACS, RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS, Serum-free media [13] | Cell maintenance and expansion | Serum-free media preferred for clinical applications [13] |

| Detection Reagents | Protein L, Recombinant target antigen, Anti-Fab antibodies [13] | CAR expression detection | Protein L detects most scFvs without interfering with antigen binding [13] |

| Functional Assays | LDH release kit, IFN-γ ELISA, CFSE, Real-time cell analyzers (e.g., xCelligence) [13] | Efficacy assessment | Multiple assays recommended for comprehensive functional characterization [13] |

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

The evolution of CAR designs has enabled expansion into novel therapeutic areas beyond hematological malignancies. In solid tumors, targets such as MSLN (mesothelin), GPC3, HER2, and GD2 are being investigated in clinical trials, though challenges remain with the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [12]. For autoimmune diseases, CD19-targeted CAR-T cells have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in eliminating pathogenic B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus, with sustained remissions in 80% of treated cases in clinical trials [11]. Similar approaches are being explored for multiple sclerosis, systemic sclerosis, and autoimmune neuropathies [11]. Emerging delivery technologies including in vivo CAR generation using targeted viral vectors or lipid nanoparticles could revolutionize manufacturing by eliminating complex ex vivo processes [13]. Additionally, advanced gene editing tools like CRISPR/Cas9 enable precise integration of CAR constructs into safe harbor loci, potentially enhancing safety and efficacy profiles [8] [10].

The generational evolution of CAR designs represents a remarkable convergence of immunology, synthetic biology, and genetic engineering. From the simple first-generation constructs to the sophisticated fifth-generation systems, each iteration has addressed critical limitations while expanding therapeutic possibilities. The progressive incorporation of costimulatory domains, cytokine signaling modules, and regulatory circuits has transformed CAR-T cells from simple cytotoxic agents to intelligent therapeutic systems capable of complex environmental integration. For researchers developing next-generation CAR therapies, careful consideration of structural components, signaling architecture, and safety controls remains paramount. As the field advances toward more universal, controllable, and persistent CAR therapies, these fundamental principles of CAR design will continue to guide innovation in this transformative cancer immunotherapy modality.

Key Historical Milestones and Paradigm Shifts in CAR-T Therapy

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a transformative approach in cancer immunotherapy, marking a significant paradigm shift from conventional cancer treatments. This groundbreaking modality involves genetically engineering a patient's own T lymphocytes to express synthetic receptors that recognize specific tumor-associated antigens, thereby redirecting the immune system to target and eliminate malignant cells. The development of CAR-T therapy spans several decades of intensive research, culminating in unprecedented clinical success for patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. This application note details the key historical milestones, provides detailed experimental protocols central to CAR-T development and manufacturing, and outlines advanced computational approaches that are shaping the next generation of CAR-T therapies. Framed within the broader context of CAR T-cell engineering protocols for cancer immunotherapy research, this resource provides scientists and drug development professionals with both foundational knowledge and cutting-edge methodologies driving the field forward.

Historical Milestones and Paradigm Shifts

The evolution of CAR-T therapy is characterized by several distinct phases of innovation, each representing a fundamental shift in how researchers approach cancer treatment. Table 1 summarizes the key historical milestones that have defined this revolutionary therapeutic field.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in CAR-T Therapy Development

| Year | Milestone | Significance | Key Researchers/Entities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860s-1890s | Early observations of infection-induced tumor regression | Foundation of cancer immunotherapy; established that immune system can fight cancer | Busch, Fehleisen, Coley [14] |

| 1987 | First concept of chimeric T-cell receptor | Proof-of-concept that antibody-derived variable regions could be fused to TCR constant regions to activate T cells | Kurosawa et al. [14] |

| 1989 | Redirection of T cells to specific antigens | Demonstrated engineered receptors could redirect T-cell specificity | Eshhar et al. [14] |

| 2017 | First FDA approval of CAR-T therapy (tisagenlecleucel) | Landmark regulatory approval for pediatric and young adult r/r B-cell ALL | FDA, Novartis [14] |

| 2023 | Six approved CAR-T therapies | Demonstrated unprecedented efficacy in B-cell malignancies and multiple myeloma | Various pharmaceutical companies [14] |

| 2024-2025 | Expansion into autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE) | Paradigm shift beyond oncology; early success in refractory autoimmune conditions | Various academic and industry groups [14] [15] |

The conceptual foundation for CAR-T therapy emerged from early observations in the 1860s-1890s by German physicians Wilhelm Busch and Friedrich Fehleisen, and later by Dr. William B. Coley at New York Hospital, who noted tumor regression in patients with concurrent bacterial infections [14]. This established the fundamental principle that the immune system could be harnessed to fight cancer, laying the groundwork for modern cancer immunotherapy.

The modern era of CAR-T therapy began with groundbreaking work in the late 1980s. In 1987, Japanese immunologist Dr. Yoshikazu Kurosawa and his team reported the first chimeric T-cell receptor, combining antibody-derived variable regions (VH/VL) with T-cell receptor constant regions [14]. This landmark study demonstrated that modified receptors could activate T cells in response to specific antigens. Two years later, Dr. Zelig Eshhar and colleagues at the Weizmann Institute of Science described a similar approach to redirect T cells to recognize predefined antigens, establishing the basic architecture of modern CAR constructs [14].

The most significant translational milestone occurred in 2017 when the FDA approved tisagenlecleucel for pediatric and young adult patients with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia [14]. This landmark approval validated decades of research and established CAR-T therapy as a viable treatment modality. By 2023, six CAR-T therapies had received regulatory approval, demonstrating remarkable efficacy against various B-cell malignancies and multiple myeloma [14].

A recent paradigm shift has been the application of CAR-T therapy beyond oncology. Early studies have demonstrated promising results in autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antisynthetase syndrome [14]. As of 2025, dual-target CAR-T products such as CTA313 (targeting both CD19 and BCMA) have shown encouraging early results in patients with refractory active SLE, potentially offering a more comprehensive immune reset and drug-free remission for some patients [15].

Experimental Protocols in CAR-T Therapy

CAR-T Cell Manufacturing Workflow

The manufacturing of CAR-T cells is a multi-step process that requires strict adherence to protocol to ensure product quality, efficacy, and safety. Figure 1 illustrates the complete workflow, from leukapheresis to final infusion.

Figure 1: CAR-T Cell Manufacturing Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in producing clinical-grade CAR-T cells, from initial T-cell collection through activation, genetic modification, expansion, and final product formulation.

Detailed Manufacturing Protocol

Step 1: Leukapheresis and T-cell Collection

- Procedure: Collect patient's peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) via leukapheresis. Process within 24 hours of collection.

- Critical Parameters: Target yield of 1-10 × 10^9 PBMCs; maintain sterility throughout processing.

- Quality Check: Cell viability >90% by trypan blue exclusion; enumerate CD3+ T-cell percentage by flow cytometry (target >40% of PBMCs).

Step 2: T-cell Activation

- Procedure: Resuspend cells at 1-2 × 10^6 cells/mL in appropriate media (X-VIVO 15 or TexMACS). Add T-cell activator (e.g., CD3/CD28 antibodies conjugated to magnetic beads) at 1:1 bead-to-cell ratio.

- Culture Conditions: Incubate at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24-48 hours.

- Media Composition: Supplement with 5-10% human AB serum or serum-free replacements; add IL-2 (100-300 IU/mL) to promote T-cell survival and proliferation [16] [17].

Step 3: Genetic Modification

- Procedure: Transduce activated T cells with lentiviral or retroviral vectors encoding CAR construct at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5-20. Use centrifugation (2000 × g, 90-120 minutes at 32°C) or static transduction with retronectin to enhance transduction efficiency.

- Critical Parameters: Determine transduction efficiency 48-72 hours post-transduction by flow cytometry for CAR expression or surface markers (e.g., LNGFR for truncated selection marker).

- Alternative Approaches: For non-viral methods, use transposon/transposase systems (e.g., Sleeping Beauty) or CRISPR-based gene editing for targeted integration [16].

Step 4: Ex Vivo Expansion

- Procedure: Culture transduced cells in gas-permeable culture bags or G-Rex bioreactors at 0.5-1 × 10^6 cells/mL. Maintain culture for 7-14 days with regular feeding (50-70% media exchange every 2-3 days).

- Cytokine Support: Include IL-2 (50-100 IU/mL) or cytokine combinations (IL-7/IL-15 at 10-20 ng/mL each) to promote central memory phenotype and enhance persistence [16] [17].

- Monitoring: Monitor cell density, viability, and CAR expression daily. Target expansion fold of 20-100× from initial T-cell count.

Step 5: Formulation and Cryopreservation

- Procedure: Harvest cells when viability >80% and target cell number achieved. Wash cells and resuspend in cryopreservation medium (e.g., 5% DMSO, 40% human AB serum, 55% saline).

- Final Product: Fill in infusion bags; cryopreserve using controlled-rate freezer. Store in vapor phase liquid nitrogen until infusion.

- Release Testing: Perform sterility (bacterial/fungal culture), mycoplasma, endotoxin, and identity/potency assays before release [16].

In Vitro Functional Assessment Protocols

Cytotoxicity Assay (xCELLigence System)

Purpose: To quantitatively measure CAR-T cell-mediated killing of tumor cells in real-time.

Materials:

- xCELLigence RTCA instrument (ACEA Biosciences)

- E-Plate 16 or 96

- Target tumor cells expressing cognate antigen

- CAR-T cells and untransduced T-cell controls

- Appropriate cell culture medium

Procedure:

- Background Measurement: Add 50 μL of culture medium to each well of the E-Plate and measure background impedance.

- Seed Target Cells: Add 50,000 tumor cells in 100 μL medium per well (for 96-well format). Allow cells to adhere and proliferate for 24 hours.

- Establish Baseline: Monitor Cell Index (CI) every 15 minutes until plateau phase is reached (typically 18-24 hours).

- Add Effector Cells: Add CAR-T cells at various effector-to-target (E:T) ratios (e.g., 1:1, 3:1, 10:1) in 50 μL medium. Include controls (target cells alone; untransduced T cells).

- Continuous Monitoring: Monitor CI every 15 minutes for 3-7 days. Normalize CI to time of effector cell addition.

- Data Analysis: Calculate specific lysis using formula: % Specific Lysis = [1 - (CI{sample}/CI{target alone})] × 100 [18].

Troubleshooting:

- Low CI values may indicate poor cell adhesion; optimize seeding density.

- Edge effect in plates can cause well-to-well variation; use interior wells for critical comparisons.

- For non-adherent target cells, use alternate systems (e.g., flow cytometry-based killing assays).

Cytokine Release Assay

Purpose: To quantify T-cell activation by measuring cytokine secretion following antigen engagement.

Materials:

- CAR-T cells and target cells

- Culture plates (96-well U-bottom recommended)

- Cytokine detection kit (Luminex or ELISA for IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α)

- Plate reader or Luminex instrument

Procedure:

- Co-culture Setup: Seed 100,000 CAR-T cells with 100,000 target cells in 200 μL complete medium per well. Include controls (CAR-T cells alone; target cells alone; untransduced T cells with targets).

- Incubation: Incubate for 18-24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2.

- Supernatant Collection: Centrifuge plates at 300 × g for 5 minutes; carefully transfer 150 μL supernatant to new plate.

- Cytokine Quantification: Analyze supernatants using multiplex bead array (Luminex) or ELISA according to manufacturer's protocols.

- Data Analysis: Calculate antigen-specific cytokine production by subtracting background from control wells. Report as pg/mL/10^6 cells [16].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for CAR-T Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | X-VIVO 15, TexMACS, RPMI-1640 with supplements | Supports T-cell growth and maintains optimal phenotype during expansion | Different media yield varied T-cell phenotypes and functions [16] [17] |

| Activation Reagents | CD3/CD28 antibodies conjugated to magnetic beads, soluble agonists | Activates T-cell signaling pathways prior to genetic modification | Bead-to-cell ratio and activation duration impact differentiation state [16] |

| Gene Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral vectors, retroviral vectors, transposon systems | Mediates stable integration of CAR transgene into T-cell genome | Vector choice affects transduction efficiency, insertion site profile, and safety [16] |

| Cytokine Supplements | IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, IL-21 | Promotes T-cell survival, expansion, and modulates differentiation | IL-7/IL-15 combination favors less differentiated memory phenotypes [16] [17] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CAR detection reagents, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45RA, CCR7 | Assesses transduction efficiency, phenotype, and differentiation status | Central memory (CD45RA-CCR7+) and naive (CD45RA+CCR7+) subsets correlate with persistence [16] |

Computational and Modeling Approaches

The complexity of CAR-T cell behavior in vivo has prompted the development of sophisticated computational models to understand and predict therapy performance. These approaches are particularly valuable for addressing challenges in solid tumors and optimizing dosing strategies.

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) Modeling

Background: QSP modeling integrates multiscale data to characterize CAR-T cell fate and antitumor cytotoxicity, from cellular interactions to clinical-level patient responses [19].

Application Protocol:

- Model Framework Establishment:

- Define key model components: CAR-T cell trafficking, tumor cell dynamics, antigen expression heterogeneity, and tumor microenvironment factors.

- Incorporate known biological parameters: CAR-T proliferation rates, tumor doubling times, antigen density, and immunosuppressive factors.

Data Integration:

- Input preclinical data: in vitro cytotoxicity, CAR-T proliferation kinetics, cytokine secretion profiles.

- Incorporate patient-specific parameters: tumor burden, antigen expression patterns, immune cell infiltration.

Virtual Patient Population Generation:

- Create in silico cohorts reflecting physiological and pathophysiological variability.

- Define parameter distributions based on clinical data from relevant patient populations.

Simulation and Prediction:

- Simulate clinical responses to different CAR-T dosing regimens (e.g., fractionated dosing vs. flat dosing).

- Identify critical factors driving response variability and potential resistance mechanisms [19].

Case Example: A recent multiscale QSP model for CLDN18.2-targeted CAR-T therapy in gastric cancer integrated in vitro and in vivo data to project clinical efficacy and optimize dosing strategies. The model successfully characterized the paired cellular kinetics-cytotoxicity response and informed clinical trial design [19].

SINDy Algorithm for Model Discovery

Background: Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDy) is a data-driven approach that discovers governing equations from time-series data without pre-specified model structures [18].

Application Protocol:

- Data Preparation:

- Collect high-temporal resolution data on cancer cell and CAR-T cell populations from in vitro killing assays.

- Preprocess data: smooth noise, interpolate missing time points if necessary.

Library Construction:

- Build a comprehensive library of candidate mathematical terms that could describe the interaction dynamics (e.g., linear, quadratic, cubic terms; predator-prey interaction terms).

Sparse Regression:

- Apply sequential thresholded least-squares algorithm to identify the minimal set of terms that accurately describe the dynamics.

- Validate discovered models against held-out data.

Biological Interpretation:

- Relate identified mathematical terms to biological mechanisms (e.g., single vs. double CAR-T-cancer cell binding; functional responses; density-dependent growth) [18].

Implementation Example: In a recent application to CAR T-cell killing of glioblastoma cells, SINDy revealed interaction dynamics that included terms suggestive of single CAR T-cell binding and logistic growth constraints, providing unique insight into the mechanisms governing CAR T-cell efficacy [18].

Figure 2 illustrates the integration of computational and experimental approaches in CAR-T therapy development.

Figure 2: Computational and Experimental Workflow Integration. This diagram shows how experimental data feeds into both mechanistic (QSP) and data-driven (SINDy) modeling approaches to generate predictions that inform therapy optimization.

CAR-T therapy has undergone remarkable evolution from conceptual beginnings to established therapeutic modality, with ongoing paradigm shifts expanding its application into autoimmune diseases. The historical milestones outlined in this application note demonstrate how fundamental scientific discoveries have been translated into clinically impactful treatments. The detailed experimental protocols provide researchers with standardized methodologies for CAR-T cell manufacturing and functional assessment, while the computational approaches offer powerful tools to overcome persistent challenges, particularly in solid tumors. As the field continues to advance, the integration of sophisticated engineering strategies with multiscale computational modeling will be essential for developing next-generation CAR-T therapies with enhanced efficacy, improved safety profiles, and broader applicability across diverse disease indications.

The integration of costimulatory domains is a critical advancement in chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell engineering, moving beyond first-generation designs that relied solely on the CD3ζ activation signal [20] [21]. Second-generation CARs incorporate a single costimulatory domain, with CD28 and 4-1BB emerging as the most prevalent and clinically successful choices [20] [21]. All currently marketed CAR-T cell products are of this second generation, and the choice between these two costimulatory domains profoundly influences the clinical behavior of the resulting cellular therapy, impacting everything from initial cytotoxic potency to long-term persistence and safety profile [22] [23] [21]. This application note provides a structured, comparative analysis of CD28 and 4-1BB to inform research and development protocols in cancer immunotherapy.

Functional and Clinical Comparison

The selection of a costimulatory domain dictates the functional phenotype, metabolic programming, and clinical performance of CAR-T cells. The table below summarizes the core characteristics and comparative outcomes associated with CD28 and 4-1BB.

Table 1: Functional and Clinical Characteristics of CD28 vs. 4-1BB Costimulatory Domains

| Characteristic | CD28 | 4-1BB |

|---|---|---|

| Signaling Kinetics | Rapid, high-amplitude signaling [24] | Slower, lower-amplitude signaling [24] |

| Metabolic Profile | Glycolysis-biased metabolism; supports an effector phenotype [23] | Enhanced mitochondrial fitness and oxidative metabolism; supports memory phenotype [23] |

| In Vivo Persistence | Shorter persistence; prone to exhaustion [22] [25] [24] | Superior long-term persistence [26] [27] [21] |

| T cell Differentiation | Promotes effector/effector memory differentiation [23] [25] | Favors central memory differentiation [26] [23] |

| Clinical Safety Profile | Associated with more severe CRS and ICANS in a B-NHL study [22] | Better tolerated; lower incidence of severe CRS and ICANS in a B-NHL study [22] |

| Representative Products | Axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta), Brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus) [21] | Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah), Lisocabtagene maraleucel (Breyanzi) [21] |

Signaling Mechanisms and Downstream Pathways

The distinct clinical profiles of CD28 and 4-1BB are rooted in their differential engagement of downstream signaling cascades.

CD28 Signaling Motifs and Pathways

The cytoplasmic tail of CD28 contains key signaling motifs—YMNM, PRRP, and PYAP—that activate downstream pathways by recruiting specific kinases and adaptor proteins [25]. Upon engagement, these motifs:

- YMNM: Recruits the p85 subunit of PI3K, activating the PI3K-AKT pathway and promoting glucose uptake and glycolytic metabolism [25].

- PYAP/PRRP: Binds LCK and GRB2-GADS, activating the Ras-MAPK pathway and regulating actin polymerization and immune synapse formation [25]. This robust signaling drives potent effector functions but can also lead to terminal differentiation and exhaustion [25] [24].

4-1BB Signaling Pathway

The 4-1BB costimulatory domain signals primarily through TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs), leading to the activation of the NF-κB pathway [26] [27]. This signaling axis enhances cell survival, promotes the development of long-lived memory T cells, and sustains mitochondrial biogenesis and fitness, which underpin the superior persistence of 4-1BB-co-stimulated CAR-T cells [26] [23].

Comparative Signaling Pathway Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and transcriptional outcomes initiated by the CD28 and 4-1BB costimulatory domains, integrating with the core CD3ζ activation signal.

Experimental Protocols for In Vitro Evaluation

A standardized in vitro evaluation is essential for directly comparing the function of CAR-T cells incorporating different costimulatory domains.

CAR-T Cell Manufacturing Protocol

Objective: To generate human CAR-T cells expressing either CD28 or 4-1BB costimulatory domains. Key Reagents:

- Source of T cells: Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors or patients [22] [27].

- T cell Activation: Stimulate purified T cells with plate-bound anti-CD3 (e.g., 0.25 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (e.g., 1 μg/ml) antibodies for 72 hours [27].

- Genetic Transduction: Transduce activated T cells with lentiviral vectors encoding the CAR constructs at a predetermined multiplicity of infection (MOI; e.g., MOI 10) [27].

- Cell Culture: Culture transduced T cells in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with IL-2 (e.g., 200 IU/ml) [27]. For persistent stimulation, cells can be re-stimulated weekly with irradiated tumor cells [27].

Cytotoxic Killing Assay

Objective: To quantify the specific cytotoxic potency of CAR-T cells against target tumor cells. Procedure:

- Coculture Setup: Seed target tumor cells (e.g., Raji or NALM-6 for CD19+ targets) in a 96-well plate. Add CAR-T cells at various effector-to-target (E:T) ratios (e.g., 1:0.5, 1:1, 1:2) [27].

- Incubation: Coculture cells for 12-24 hours at 37°C.

- Analysis: Harvest cells and analyze tumor cell lysis by flow cytometry. Use antibodies against markers like CD3 (for T cells) and CD19 (for target B cells) to distinguish populations and quantify specific killing [27].

Cytokine Release Assay

Objective: To measure T cell activation strength by quantifying secreted cytokines. Procedure:

- Stimulation: Coculture CAR-T cells with target tumor cells at specified E:T ratios for 12-24 hours.

- Supernatant Collection: Centrifuge the coculture plates and collect the cell-free supernatant.

- Quantification: Analyze supernatant concentrations of key cytokines like IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 using a Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) or ELISA, following manufacturer protocols [27]. CD28-CAR T cells typically exhibit more rapid and robust cytokine secretion [22] [24].

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The standard workflow for generating and functionally testing CAR-T cells with different costimulatory domains is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful evaluation of costimulatory domains requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table lists essential materials for the protocols described in this note.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Costimulatory Domain Evaluation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vectors | Delivery of CAR constructs into T cells. | Constructs with identical scFv, hinge/TM, and CD3ζ, differing only in CD28 vs. 4-1BB costimulatory domain [22] [21]. |

| Anti-CD3/Anti-CD28 Antibodies | Polyclonal T cell activation during manufacturing. | Plate-bound or bead-bound antibodies for initial T cell stimulation [27]. |

| Recombinant Human IL-2 | Supports T cell survival and expansion in culture. | Used at 200 IU/ml during ex vivo expansion [27]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Cell phenotyping and cytotoxicity analysis. | Anti-CD3, anti-CD19 (for target cells), anti-CD45RO/RA, anti-CD62L (memory phenotyping), viability dyes [27]. |

| Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) | Multiplexed quantification of cytokine secretion. | Commercial kits for human IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, etc. [27]. |

| Target Cell Lines | Antigen-positive cells for functional assays. | CD19+ lines: Raji, Daudi, NALM-6 [27]. Ensure consistent antigen density. |

| NSG Mice | In vivo model for evaluating persistence and anti-tumor efficacy. | NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ mice for xenograft studies [27]. |

Emerging Strategies and Combinatorial Approaches

Given the complementary strengths of CD28 and 4-1BB, advanced engineering strategies are being explored to harness the benefits of both.

- Third-Generation CARs: These constructs incorporate both CD28 and 4-1BB costimulatory domains in tandem within the same CAR molecule. Research indicates that the specific order and structure of these combined domains are critical for optimal function, influencing LCK recruitment and enhancing expansion and persistence [26].

- Optimized CD28 Mutants: Rather than using the full native domain, researchers are engineering mutated versions of CD28 (e.g., mut06 with a modified PYAP motif) to reduce exhaustion and improve signaling quality. Combining this optimized CD28 with 4-1BB in a third-generation design has shown enhanced anti-tumor activity in preclinical models [26].

- Constitutive 4-1BB Co-expression: An alternative to domain stacking is to express a canonical CD28-based CAR alongside a separate, constitutively expressed full-length 4-1BB receptor. This strategy has been shown to improve proliferation, reduce apoptosis, and enhance in vivo tumor control compared to the CD28-CAR alone [27].

The choice between CD28 and 4-1BB is not a matter of identifying a universally superior domain, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific therapeutic context. CD28 drives powerful, rapid effector responses suitable for aggressive malignancies but carries a higher risk of toxicity and limited durability. 4-1BB promotes long-term persistence and a favorable safety profile, which may be critical for controlling relapsing disease. The future of costimulatory engineering lies in sophisticated combination strategies—such as third-generation CARs and optimized domain mutants—that aim to synthetically engineer T cells with the rapid strike capability of CD28 and the enduring persistence of 4-1BB, thereby overcoming the limitations of each individual domain.

From Bench to Bedside: CAR-T Cell Manufacturing and Clinical Translation Protocols

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy represents a groundbreaking advancement in cancer immunotherapy, demonstrating remarkable efficacy in treating hematological malignancies. The manufacturing of CAR-T cells is a multi-step process that begins with the collection of a patient's immune cells and culminates with the infusion of engineered T cells capable of selectively targeting and destroying tumor cells. This application note delineates a standardized, robust workflow for the production of research-grade CAR-T cells, encompassing the critical stages of leukapresis processing, T-cell activation, viral transduction, and in vitro expansion. The protocols and data presented herein are framed within the context of advancing CAR T-cell engineering protocols for cancer immunotherapy research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with detailed methodologies to enhance reproducibility and efficacy in pre-clinical studies.

The journey from patient leukapheresis to CAR-T cell infusion product is a meticulously orchestrated sequence. Figure 1 below provides a holistic overview of this complex process, highlighting the key stages and their temporal relationships.

A critical initial decision in the workflow is the selection and processing of the starting material. The choice between fresh and cryopreserved leukapheresis, or the use of PBMCs, can significantly impact initial cell quality and downstream manufacturing success. Table 1 summarizes key quantitative benchmarks for different starting materials, providing researchers with critical quality attributes to target.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of CAR-T Starting Materials [28] [29]

| Parameter | Fresh Leukapheresis | Cryopreserved Leukapheresis | PBMCs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Viability | >95% | 90-97% | >90% |

| Post-Thaw Viability | N/A | ≥90% (Target) | Variable |

| Lymphocyte Proportion | ~68.7% | ~66.6% | ~52.2% |

| T Cell (CD3+) Proportion | High | 42-51% | Variable |

| Key Advantage | Maximum initial viability | Supply chain flexibility, scheduling freedom | Established protocol |

| Primary Challenge | Strict 24-72hr processing window [29] | Optimized freeze/thaw protocol required | Potential cell loss during isolation |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Leukapheresis Processing and PBMC Isolation

The initial step in CAR-T manufacturing involves obtaining a sufficient number of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), which include T lymphocytes, from a leukapheresis product [28].

Principle: Density gradient centrifugation separates PBMCs from other blood components based on density differences [30].

Materials:

- Leukapheresis product (fresh or cryopreserved)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Density Gradient Medium (e.g., Ficoll-Paque or Lymphoprep)

- Centrifuge

- SepMate tubes (optional, for process acceleration)

Procedure:

- Dilution: Dilute the leukapheresis product 1:1 to 1:2 with PBS [28].

- Layering: Carefully layer the diluted blood over the density gradient medium in a centrifuge tube. Maintain a sharp interface [30] [28].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 400 × g for 30 minutes at room temperature with the brake disengaged [28].

- Collection: After centrifugation, carefully aspirate the plasma and PBMC layers. The PBMCs form a distinct white ring at the plasma/gradient medium interface. Collect this layer into a new tube [28].

- Washing: Wash the collected PBMCs with PBS or a balanced salt solution and centrifuge to pellet the cells. Perform a cell count and viability assessment.

T Cell Activation

Isolated T cells must be activated to enter the cell cycle and become receptive to genetic modification via transduction.

Principle: T-cell receptor (TCR) complex engagement with co-stimulatory signals initiates T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.

Materials:

- Isolated PBMCs

- Complete Medium (e.g., AIM-V medium supplemented with 2-10% human AB serum [28])

- T-Cell Activator (e.g., anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies)

- Recombinant Human IL-2

Procedure:

- Resuspension: Resuspend PBMCs in complete medium at a concentration of 1-2 × 10^6 cells/mL [28].

- Stimulation: Add T-cell activation reagents. A common method is using a combination of 50 ng/mL anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (e.g., OKT-3) and 300 IU/mL recombinant human IL-2 [28]. Alternatives include coated magnetic beads or soluble antibodies.

- Incubation: Culture cells in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24-48 hours prior to transduction.

CAR Transduction

This critical step introduces the CAR gene into activated T cells, enabling them to express the chimeric antigen receptor.

Principle: Viral vectors, such as gamma-retroviruses or lentiviruses, are engineered to carry the CAR transgene and facilitate its integration into the host T-cell genome, leading to stable CAR expression [31] [28].

Materials:

- Activated T cells

- CAR Viral Vector Supernatant (Lentiviral or Retroviral)

- Retronectin or other transduction enhancers

- Polybrene (for lentiviral transduction)

- Centrifuge

Procedure (Retronectin-assisted Retroviral Transduction):

- Coating: Coat non-tissue culture treated plates with Retronectin (10 µg/mL in PBS) for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C [28].

- Blocking: Block the plates with 2.5% human albumin in PBS for 30 minutes, then wash [28].

- Vector Loading: Load the diluted retroviral supernatant onto the coated plates. Centrifuge at 2000 × g for 0.5-2 hours at 32°C, then aspirate the supernatant [28].

- Transduction: Seed the activated T cells onto the vector-coated plates. Centrifuge the plates at 1000 × g for 15 minutes (spinoculation) and incubate at 37°C overnight [28].

- Harvest: Approximately 24 hours post-transduction, harvest the cells and transfer them to expansion vessels [28].

Table 2 compares the primary viral vector systems used in CAR-T research, highlighting their distinct characteristics to guide experimental design.

Table 2: Comparison of CAR Transduction Methods [31]

| Vector System | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vector | Integrates into host genome, including non-dividing cells. | High transduction efficiency; broad tropism. | Complex production; safety concerns regarding insertional mutagenesis. |

| Retroviral Vector | Integrates into host genome (requires cell division). | Robust, well-established methodology. | Requires cell division; safety concerns regarding insertional mutagenesis. |

| Non-Viral Methods (e.g., Transposon Systems, mRNA Electroporation) | Genome integration via transposase (Sleeping Beauty) or transient cytoplasmic expression (mRNA). | Reduced risk of insertional mutagenesis; often more cost-effective. | Historically lower efficiency than viral methods (transposons); transient expression (mRNA). |

In Vitro Expansion

Following transduction, CAR-T cells are expanded ex vivo to achieve the target cell dose required for therapeutic efficacy.

Principle: Transduced T cells are cultured in cytokine-supplemented media to promote proliferation and achieve the desired cell numbers while maintaining a less differentiated, more therapeutically potent cell phenotype.

Materials:

- Transduced T cells

- Complete Medium

- Recombinant Human IL-2

- Culture Flasks or Bioreactors (e.g., G-Rex flasks)

Procedure:

- Initiation of Culture: Resuspend the harvested, transduced cells in complete medium supplemented with IL-2 (e.g., 300 IU/mL) at a density of 0.5 × 10^6 cells/mL [28].

- Maintenance: Culture the cells in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 7-14 days. Maintain cell concentration between 0.5-2.0 × 10^6 cells/mL by diluting with fresh medium + IL-2 as needed [28].

- Monitoring: Monitor cell density, viability, and CAR expression regularly via flow cytometry.

- Harvest: Once the target cell number is achieved and viability is confirmed to be >90%, harvest the cells for downstream assays, cryopreservation, or infusion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of the CAR-T workflow relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below details essential components and their functions.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Products / Components |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Separation Kits | Isolation of specific cell subsets (e.g., T cells) from complex starting materials like leukopaks with high purity and viability. | EasySep [30], Akadeum Microbubble Kits [31] [32] |

| T Cell Activators | Provides signal 1 (TCR engagement via anti-CD3) and signal 2 (co-stimulation via anti-CD28) for robust T cell activation and proliferation. | Anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies, TransAct |

| CAR Viral Vectors | Delivery vehicle for the stable integration of the CAR transgene into the host T cell genome. | Lentiviral/CD19 CAR retroviral supernatant [28] |

| Transduction Enhancers | Increases transduction efficiency by co-localizing viral particles and target cells. | Retronectin [28], Polybrene |

| Cell Culture Media | Provides nutrients and essential components for T cell growth, expansion, and maintenance of function. | AIM-V medium [28], X-VIVO, TexMACS |

| Cytokines | Supports T cell survival, proliferation, and can influence differentiation state (e.g., memory vs. effector phenotypes). | Recombinant Human IL-2 [28], IL-7, IL-15 |

| Cryopreservation Media | Protects cells from damage during freezing and long-term storage, preserving viability and function. | CS10 (10% DMSO) [29] |

Signaling Pathways in CAR-T Cell Activation

Understanding the intracellular signaling that governs CAR-T cell function is essential for optimizing their therapeutic potential. The core signaling architecture of a second-generation CAR, the most clinically advanced design, integrates signals from both the TCR complex and co-stimulatory receptors. Figure 2 illustrates this integrated signaling pathway, which is triggered upon CAR engagement with its target antigen.

This application note provides a detailed, standardized framework for the key manufacturing stages of research-grade CAR-T cells: leukapheresis processing, T-cell activation, transduction, and expansion. By adhering to the protocols, quantitative benchmarks, and reagent specifications outlined herein, researchers can enhance the consistency, efficacy, and safety profiling of their CAR-T cell products. The continued refinement of these workflows, informed by a deep understanding of CAR signaling and cell biology, is paramount for advancing the next generation of cancer immunotherapies and translating pre-clinical success into broader clinical application.

The engineering of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells represents a paradigm shift in cancer immunotherapy, showing remarkable efficacy against hematological malignancies. The success of this cellular therapy is fundamentally dependent on the methods used for gene delivery, which can be broadly categorized into viral and non-viral approaches [33]. Viral vectors, particularly lentiviruses and gammaretroviruses, have been the historical workhorses for CAR gene delivery, offering high transduction efficiency and stable long-term transgene expression. However, concerns regarding immunogenicity, insertional mutagenesis, complex manufacturing, and high costs have prompted the development of non-viral alternatives [34]. Non-viral methods, including electroporation of mRNA or DNA and nanoparticle-based delivery, are emerging as promising strategies that offer enhanced safety profiles, greater payload capacity, reduced manufacturing timelines, and lower costs [35] [36]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these platforms and outlines optimized protocols for their implementation in CAR T cell research, framed within the context of a broader thesis on CAR T cell engineering protocols.

Vector Platform Comparison

The choice between viral and non-viral vector systems involves critical trade-offs between transduction efficiency, safety, manufacturability, and clinical performance. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the predominant vector platforms used in CAR T cell engineering.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Viral and Non-Viral Vector Platforms for CAR T Cell Engineering

| Feature | Lentiviral (LV) Vectors | Adenoviral (Ad) Vectors | Electroporation (mRNA) | Electroporation (DNA/CRISPR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transduction/Transfection Efficiency | High (>70%) [33] | High [37] | High (CAR+ levels ~70%) [38] | High (Knockin efficiency 35-89%) [36] |

| Integration Profile | Semi-random integration [34] | Non-integrating [37] | Non-integrating (transient) [38] | Targeted integration (with CRISPR) [36] |

| Cargo Capacity | ~8 kb [34] | Large capacity [37] [34] | Limited by mRNA size [38] | Limited by DNA plasmid size [36] |

| Stability of Expression | Stable, long-term [33] | Transient [37] | Transient (2-3 days) [38] | Stable (with targeted knockin) [36] |

| Key Advantages | Stable expression, well-characterized [33] [34] | High transgene expression, large cargo capacity [37] [34] | Rapid production, high safety, no genomic integration [38] [33] | Precise genome editing, "off-the-shelf" potential [33] [36] |

| Key Limitations | Risk of insertional mutagenesis, high cost, complex GMP manufacturing [34] | High immunogenicity, transient expression [34] | Transient CAR expression, potential for repeated dosing [38] | Technical complexity, requires optimization of HDR [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Non-Viral CRISPR-Mediated CAR Knockin via Electroporation

This protocol, adapted from a presentation by MaxCyte, details the optimized steps for achieving precise, high-efficiency knockin of a CAR construct into the TRAC locus of primary human T cells using CRISPR/Cas9 and electroporation [36].

Key Reagents and Materials

- Primary Human T Cells: Isolated from leukapheresis product or PBMCs of healthy donors.

- T Cell Activation Reagent: Anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies immobilized on a polymeric nanomatrix (e.g., for protocol B from [38]).

- Culture Medium: TheraPEAK T-VIVO medium supplemented with IL-2 [38].

- CRISPR Components:

- Cas9 Nuclease: High-quality, research-grade.

- sgRNA: Targeting the TRAC locus.

- HDR Template: A Nanoplasmid DNA vector containing the CAR expression cassette flanked by homology arms to the TRAC locus. The inclusion of a Cas9-targeting sequence (CTS) within the template is recommended to enhance knockin efficiency [36].

- Electroporation System: MaxCyte ExPERT GTx instrument with corresponding electroporation buffers [36].

- HDR Enhancer: Small molecule M3814 (2 µM final concentration), added post-electroporation [36].

Step-by-Step Workflow

- T Cell Isolation and Activation: Isolate T cells from PBMCs using a standard density gradient centrifugation or magnetic bead-based negative selection kit. Activate the isolated T cells (1-2 x 10^6 cells/mL) using the immobilized anti-CD3/anti-CD28 nanomatrix in TheraPEAK T-VIVO medium supplemented with IL-2 (e.g., 100 IU/mL) for 48 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 [38] [36].

- Pre-Electroporation Preparation: Harvest the activated T cells and wash them with PBS. Resuspend the cell pellet in MaxCyte electroporation buffer at a concentration of 1-2 x 10^8 cells/mL [36].

- Complex Formation and Electroporation:

- Pre-complex the TRAC-targeting RNP by incubating 0.5 µM Cas9 protein with a 2x molar ratio (1.0 µM) of sgRNA for 10-15 minutes at room temperature.

- Mix the cell suspension with the pre-complexed RNP and 200 µg/mL of the Nanoplasmid HDR template.

- Immediately transfer the mixture to an electroporation cuvette and electroporate using the Expanded T Cell Four (ETC4) protocol on the MaxCyte ExPERT GTx platform [36].

- Post-Electroporation Recovery and Expansion:

- Transfer the electroporated cells to pre-warmed culture medium.

- Add the HDR enhancer M3814 to a final concentration of 2 µM.

- Culture the cells at 37°C and 5% CO2, expanding them for 14 days with periodic medium changes and IL-2 supplementation. Monitor cell density, viability, and CAR expression regularly [36].

Expected Outcomes and Quality Control

- Cell Viability: A significant drop in viability is expected immediately post-electroporation, but cells should recover to >80% within 48 hours [36].

- Knockin Efficiency: Using this optimized workflow, CAR knockin efficiencies of 67% to 89% can be achieved by day 7-14 post-electroporation, as measured by flow cytometry for the CAR protein [36].

- Functional Assessment: On day 14, co-culture engineered CAR-T cells with CD19-expressing target cells (e.g., Ramos cells) at various Effector:Target (E:T) ratios. Assess specific target cell killing and the production of effector molecules (Granzyme B, IFN-γ) via cytotoxicity assays and ELISA, respectively [36].

Protocol 2: mRNA-Based Transient CAR T Cell Generation

This protocol is ideal for applications requiring rapid testing of CAR designs or for generating transient CAR T cells for research purposes, avoiding genomic integration [38].

Key Reagents and Materials

- Culture Medium: TheraPEAK T-VIVO medium (Protocol B), which supports higher expansion rates and viability compared to some alternatives [38].

- T Cell Activator: Immobilized anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies (for Protocol B) [38].

- CAR-mRNA: In vitro transcribed (IVT) mRNA encoding the full CAR construct, capped and polyadenylated.

- Electroporation System: A research-grade electroporator with optimized settings for primary T cells (e.g., Pulse Code "CM-138" as identified in [38]).

Step-by-Step Workflow

- T Cell Expansion: Isolate and activate T cells as described in Protocol 1, step 1. Expand the activated T cells for 6-10 days. Days 6-10 post-activation have been identified as the most suitable window for mRNA transfection, balancing cell number, viability, and activation status [38].

- Electroporation:

- Harvest expanded T cells and wash with PBS.

- Resuspend cells in appropriate electroporation buffer.

- Mix cells with CAR-mRNA (typically 5-10 µg per 1x10^6 cells) and electroporate using the pre-optimized pulse code.

- Recovery and Analysis:

- Immediately transfer cells to culture medium.

- Analyze CAR expression and viability 18-24 hours post-electroporation. CAR expression is typically transient, peaking at 24 hours and declining significantly by 48-72 hours [38].

Expected Outcomes and Quality Control

- CAR Expression: >70% CAR-positive T cells at 24 hours post-transfection, dropping by at least 50% at 48 hours [38].

- Cell Viability: >80% viability at 24 hours post-transfection [38].

- Phenotype: Protocol B tends to promote a higher fraction of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, which may be beneficial for antitumor cytotoxicity [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful CAR T cell engineering relies on a suite of critical reagents. Table 2 lists key materials and their functions based on the cited protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CAR T Cell Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| T Cell Medium | Supports ex vivo T cell viability, activation, and expansion. | TheraPEAK T-VIVO; ImmunoCult-XF T Cell Expansion Medium [38] |

| T Cell Activator | Provides signal 1 (CD3) and signal 2 (CD28) for T cell activation. | Immobilized anti-CD3/anti-CD28 on nanomatrix; soluble antibody mixtures [38] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise genomic editing for targeted CAR integration. | Cas9 protein, TRAC-targeting sgRNA, HDR template plasmid/Nanoplasmid [36] |

| HDR Enhancer | Small molecule inhibitor that improves Homology-Directed Repair efficiency. | M3814; used post-electroporation to boost knockin rates [36] |

| Electroporation System | Enables efficient delivery of nucleic acids (mRNA, DNA, RNP) into T cells. | MaxCyte ExPERT GTx; optimized protocols (e.g., ETC4) are critical for high viability and efficiency [36] |

| mRNA Construct | Template for transient CAR expression without genomic integration. | In vitro transcribed (IVT) CAR-mRNA; used for rapid testing/transient expression [38] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the key procedural and mechanistic workflows described in the protocols.

Non-Viral CAR-T Engineering Workflow

CAR Signaling & Engineering Evolution

Clinical Application and Efficacy in Hematologic Malignancies (ALL, NHL, MM)

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has revolutionized the treatment of relapsed and refractory hematologic malignancies by engineering a patient's own T-cells to recognize and eliminate cancer cells. This adoptive cell transfer approach has demonstrated remarkable success across various blood cancers, particularly B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and multiple myeloma (MM). [39] [40]

The therapy involves extracting T-cells from a patient, genetically modifying them to express chimeric antigen receptors specific to tumor antigens, expanding the population ex vivo, and reinfusing them back into the patient. These engineered cells then recognize and destroy malignant cells expressing the target antigen, producing durable responses in many patients who have exhausted conventional treatment options. [40] [41]

Table 1: Clinical Efficacy of CAR-T Therapy Across Hematologic Malignancies

| Malignancy | Molecular Target | Representative Products | Efficacy Metrics | Patient Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-ALL | CD19 | Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) | High remission rates (60-80%) in refractory patients [40] | Relapsed/refractory B-ALL |

| NHL | CD19 | Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) | 91.7% ORR, 75% CR in novel AT101 trial [42] | Relapsed/refractory DLBCL, FL, MCL |

| Multiple Myeloma | BCMA | Abecma (ide-cel), Carvykti (cilta-cel) | High rates of MRD negativity; improved PFS/OS [43] | ≥1 prior line of therapy (updated 2024) |

The field continues to evolve with improvements in CAR design, expansion techniques, and combination approaches. Recent advances include targeting novel antigens, optimizing costimulatory domains, and developing strategies to enhance CAR-T cell persistence and functionality within the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. [44] [45]

Detailed Application Protocols by Malignancy

B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B-ALL)

CD19-directed CAR-T therapy has demonstrated exceptional efficacy in B-ALL, with remission rates exceeding 60-80% in some patient populations who had limited treatment options remaining. [40] The critical success factor is targeting the CD19 antigen ubiquitously expressed on B-lineage cells.

Key Protocol Parameters:

- Target Antigen: CD19

- CAR Construct: Anti-CD19 scFv (typically FMC63-derived) coupled with CD3ζ signaling domain and costimulatory domains (CD28 or 4-1BB)

- Manufacturing Time: 2-3 weeks

- Lymphodepletion: Fludarabine/cyclophosphamide regimen 3-5 days pre-infusion

- Cell Dose: 1-5×10⁶ CAR-T cells/kg (for children) or 0.5-2.5×10⁸ CAR-T cells (fixed dose for adults)