Building Better Bones: How a Nano-Scaffold is Revolutionizing Healing

Discover how surface-immobilized nano-hydroxyapatite on porous hybrid scaffolds is transforming bone regeneration and healing.

The Challenge of the Missing Piece

Imagine breaking a major bone, one so severely shattered that your body can't piece it back together. This is the reality for thousands of people due to trauma, disease, or the simple wear-and-tear of aging.

While our bones are incredible at self-repair, there's a limit. For large defects, the body's natural construction crew is left without a blueprint or scaffolding, leading to incomplete healing and permanent disability.

Traditional Solution

For decades, the gold standard has been bone grafts—taking bone from another part of the patient's body or from a donor. But this is a painful and imperfect solution.

Innovative Approach

What if we could engineer a perfect, custom-made scaffold that not only fills the gap but actively instructs the body to regenerate its own, healthy bone?

The Blueprint for Regeneration

To understand this breakthrough, we need to break down the key components of this high-tech scaffold.

The Scaffold Itself

Think of the scaffold as a temporary apartment complex for bone-forming cells (osteoblasts). It can't be a solid block; it needs to be a porous, 3D structure.

This architecture allows cells to migrate inside, provides space for new blood vessels to form (crucial for delivering nutrients), and gives the tissue a framework to grow in the right shape.

The Material

Early scaffolds were made from a single material, often a polymer like PLGA. While biocompatible, they can be too flexible or weak.

The solution? Hybrid scaffolds. By combining a polymer with a ceramic like bio-glass, scientists get the best of both worlds: the flexibility and biodegradability of the polymer with the strength and bioactivity of the ceramic.

The Secret Weapon

This is the star of the show. Hydroxyapatite is the primary mineral component of your natural bone and teeth. By engineering it at the nano-scale (billionths of a meter), its properties are supercharged.

Nano-HA is exceptionally bioactive, meaning it sends a powerful "build bone here!" signal to the body's cells. However, simply mixing nHA powder into the scaffold isn't enough—it can get lost inside and not interact effectively with cells.

The Game-Changing Technique

This is the critical innovation. Instead of mixing nHA in, scientists developed methods to firmly attach, or "immobilize," it directly onto the surface of the scaffold's pores.

It's the difference between throwing seeds randomly into a field versus carefully planting them in fertile soil. Surface immobilization ensures that the very first thing a bone cell "feels" when it enters the scaffold is the familiar, stimulating signal of nHA, dramatically accelerating the regeneration process.

A Closer Look: The Pivotal Experiment

How do we know this surface-immobilized nHA truly works? Let's examine a typical, crucial experiment that demonstrated its superior performance.

Methodology: A Step-by-Step Comparison

The goal was simple: compare the bone-regenerating ability of three different scaffolds.

1. Scaffold Fabrication

Researchers created three types of porous, hybrid (PLGA/Bio-glass) scaffolds:

- Group A (Control): A plain hybrid scaffold with no nHA.

- Group B (Mixed): A hybrid scaffold with nHA particles simply mixed into the material.

- Group C (Immobilized): A hybrid scaffold with nHA chemically immobilized onto its surface.

2. Cell Seeding

Bone-forming cells (osteoblasts) were carefully "seeded" onto each type of scaffold.

3. In-Vitro Analysis (Lab Testing)

The cell-scaffold constructs were cultured for several weeks. Scientists regularly checked for:

- Cell Proliferation: How quickly were the cells multiplying?

- Cell Differentiation: Were the cells maturing into functional, bone-producing osteoblasts?

- Mineralization: Were the cells depositing new bone mineral?

4. In-Vivo Testing (Animal Study)

The most promising scaffolds (Group B and C) were then implanted into critical-sized bone defects in the femurs of laboratory animals, with Group A as a control. After 8 and 12 weeks, the bone samples were analyzed to see how much new bone had formed.

Results and Analysis: The Proof is in the Regeneration

The results were clear and striking. The scaffolds with surface-immobilized nHA (Group C) consistently outperformed the others.

In the lab

- Cells on the immobilized scaffolds adhered more strongly and spread out better, indicating they "felt at home."

- These cells showed significantly higher expression of genes related to bone formation (like Osteocalcin and Runx2).

- They produced a much larger amount of calcium phosphate mineral, the building block of bone.

In the animal studies

- Micro-CT scans and microscope images revealed that defects treated with the immobilized nHA scaffold were filled with significantly more new, well-organized bone tissue that integrated seamlessly with the surrounding native bone.

The Data: Seeing is Believing

Table 1: Cell Proliferation Rate After 7 Days

This table shows how quickly bone cells multiplied on the different scaffolds. A higher absorbance value indicates more cells.

| Scaffold Type | Cell Viability (Absorbance) |

|---|---|

| Control (A) | 0.45 |

| Mixed nHA (B) | 0.68 |

| Immobilized nHA (C) | 0.92 |

Conclusion: The immobilized nHA scaffold created a more favorable environment for cells to grow and multiply.

Table 2: Expression of Bone-Specific Genes (Relative to Control)

This measures how "active" the bone-forming genes were in the cells. A higher value means the cells were more specialized for making bone.

| Scaffold Type | Osteocalcin | Runx2 |

|---|---|---|

| Control (A) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Mixed nHA (B) | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Immobilized nHA (C) | 5.8 | 6.4 |

Conclusion: Surface immobilization powerfully stimulated the cells to become mature, bone-producing factories.

Table 3: New Bone Volume in Defect Site After 8 Weeks

This data, from animal studies, quantifies the amount of bone regeneration.

| Scaffold Type | New Bone Volume (% of Defect) |

|---|---|

| Control (A) | 18% |

| Mixed nHA (B) | 35% |

| Immobilized nHA (C) | 62% |

Conclusion: The immobilized nHA scaffold led to the most robust and complete healing of the bone defect.

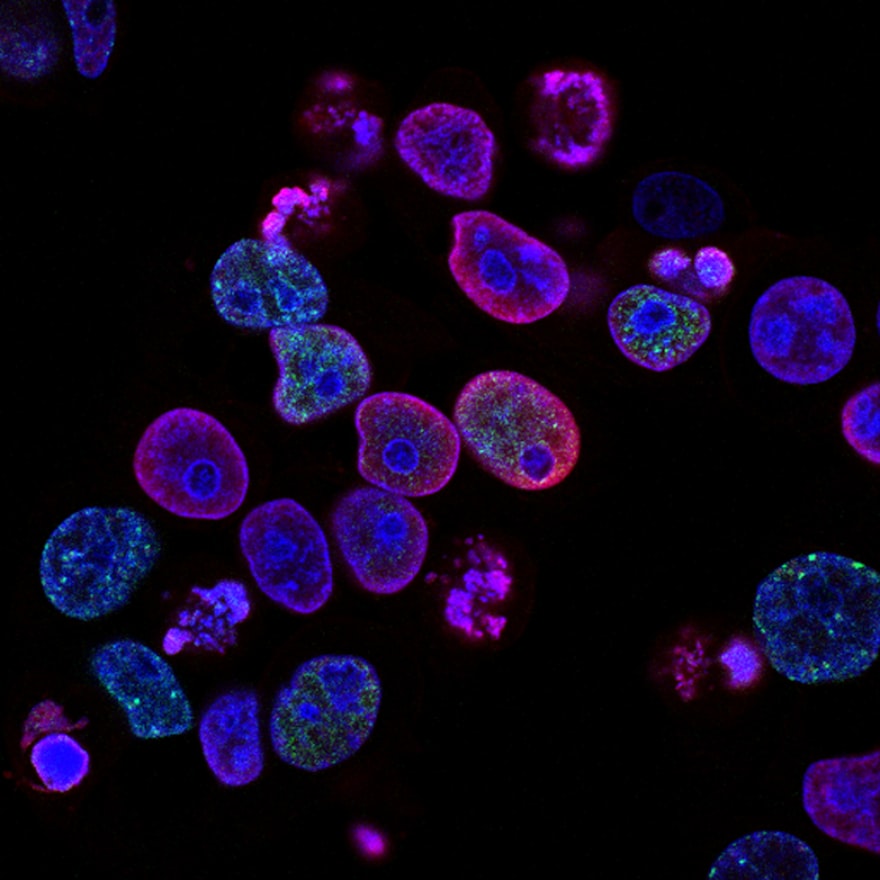

Visual Comparison: Bone Regeneration Performance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Ingredients for Bone Regeneration

Here are the essential components used to create and test these next-generation scaffolds.

PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid))

The biodegradable polymer backbone of the scaffold. It provides the 3D structure and safely dissolves as new bone grows.

Bio-glass

A ceramic material added to create the "hybrid" scaffold. It improves mechanical strength and is inherently bioactive.

Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHA)

The bioactive signal. It mimics natural bone mineral, encouraging cell attachment, proliferation, and bone formation.

Coupling Agent (e.g., APTES)

The "molecular glue." This chemical is used to permanently immobilize the nHA particles onto the scaffold's polymer surface.

Osteoblasts

The "construction crew." These bone-forming cells are used in lab tests to see how the scaffold performs.

Cell Culture Medium

The "nutrient soup." A specially formulated liquid that provides all the nutrients, vitamins, and growth factors cells need to survive and thrive outside the body.

Conclusion: A Stronger Future for Patients

The journey from a lab concept to a clinical reality is long, but the enhanced performance of scaffolds with surface-immobilized nano-hydroxyapatite represents a monumental leap forward. This technology moves us beyond simply replacing tissue to truly regenerating it.

In the future, a patient with a severe bone injury might receive a custom-designed, 3D-printed scaffold, perfectly shaped for their defect and coated with this powerful nano-signal. This implant would then guide their body to rebuild living, strong, and natural bone.

It's a future where the most complex fractures are no longer a life sentence of disability, but a temporary setback on the path to full recovery, built from the nano-scale up.