Biosensor Dynamic Range and Operational Range Explained: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the dynamic range and operational range of biosensors, two fundamental performance parameters critical for researchers and drug development professionals.

Biosensor Dynamic Range and Operational Range Explained: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the dynamic range and operational range of biosensors, two fundamental performance parameters critical for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the core definitions and the inherent 81-fold dynamic range limitation of single-site binding, explores advanced engineering strategies for tuning these ranges, and discusses practical methodologies for troubleshooting and optimization. The content also outlines the essential frameworks for validating biosensor performance and comparing different systems, equipping scientists with the knowledge to select, design, and implement biosensors effectively for applications in high-throughput screening, bioproduction monitoring, and precise clinical diagnostics.

Core Concepts: Demystifying Dynamic Range and Operational Range in Biosensors

In the development and application of biosensors, two parameters are paramount for evaluating performance: the dynamic range and the operational range. While sometimes used interchangeably, these terms describe fundamentally different characteristics. The dynamic range refers to the concentration span over which a biosensor can produce a quantifiable change in its output signal, effectively defining its sensitivity and limit of detection. In contrast, the operational range describes the full spectrum of environmental conditions—such as pH, temperature, and ionic strength—under which the biosensor maintains its specified performance metrics, including its dynamic range. Understanding and optimizing both parameters is crucial for deploying biosensors in real-world applications, from biomedical diagnostics to environmental monitoring.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of both parameters, exploring their definitions, methodologies for enhancement, and interplay within biosensor systems. Framed within broader research on biosensor performance, this analysis equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to systematically characterize and improve their biosensing platforms.

Dynamic Range: The Concentration Response Window

The dynamic range is a core performance parameter that quantifies a biosensor's ability to respond to varying analyte concentrations. It is typically defined as the range of analyte concentrations between the limit of detection (LOD) and the point of signal saturation, where the output is quantitatively correlated with the analyte level. A wide dynamic range is essential for applications requiring the detection of analytes that can vary significantly in concentration, such as metabolites in physiological fluids or pathogens in environmental samples.

Quantifying Dynamic Range

The dynamic range is most commonly visualized using a dose-response curve, where the sensor's output signal (e.g., fluorescence intensity, voltage, or FRET ratio) is plotted against the logarithm of the analyte concentration. The curve typically has a sigmoidal shape, featuring a linear region where the response is proportional to concentration. The dynamic range is often reported as the span of concentrations across this linear responsive region. The sensitivity of the biosensor is directly derived from the slope of this curve.

Table 1: Quantified Dynamic Range Enhancements in Recent Biosensor Studies

| Biosensor Target | Base Dynamic Range | Enhanced Dynamic Range | Enhancement Method | Key Metric Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-Carnitine [1] | Not specified (Limited) | 10⁻⁴ mM – 10 mM | Directed Evolution (CaiFY47W/R89A variant) | 1000-fold wider range; 3.3-fold higher signal |

| Calcium, ATP, NAD+ [2] | Low (Conventional FRET pairs) | Unprecedented (Specific values not given) | Chemogenetic FRET pairs (e.g., ChemoG5) | Near-quantitative FRET efficiency (≥94%) |

| Lysine [3] | Low dynamic range | Significantly improved | Multilevel optimization (Point mutations, promoter engineering) | Improved dynamic range and lysine response |

Methodologies for Extending Dynamic Range

Research has yielded several powerful strategies for expanding the dynamic range of biosensors.

Directed Evolution and Rational Protein Design: As demonstrated with the l-carnitine biosensor, the transcription factor CaiF was engineered using a "Functional Diversity-Oriented Volume-Conservative Substitution Strategy" on key amino acids. The resulting variant, CaiFY47W/R89A, exhibited a 1000-fold wider concentration response range and a 3.3-fold higher output signal compared to the wild-type control [1]. This approach relies on computer-aided design to model protein structure and identify mutation sites, followed by experimental validation.

Chemogenetic FRET Pair Engineering: A groundbreaking method involves engineering a reversible interaction between a fluorescent protein (FP) and a synthetically labeled HaloTag (HT7). This creates a FRET pair with near-quantitative efficiency (≥94%). By optimizing the interface between the FP donor and the rhodamine-labeled HT7 acceptor, researchers developed biosensors for calcium, ATP, and NAD+ with "unprecedented dynamic ranges" [2]. The protocol involves:

- Fusing a FP (e.g., eGFP) to the N-terminus of HT7.

- Identifying key interface residues (e.g., eGFP Y39, K41, F223) via X-ray crystallography.

- Introducing stabilizing mutations (e.g., eGFP: A206K, T225R; HT7: E143R, E147R, L271E) in a stepwise manner to create variants (ChemoG1 to ChemoG5).

- Labeling the optimized construct (ChemoG5) with cell-permeable rhodamine derivatives (e.g., SiR, JF525, JF669) to achieve spectrally tunable, high-efficiency FRET.

Multilevel Optimization: For the lysine biosensor in E. coli, a low dynamic range was overcome by combining key point mutations in the sensing proteins (LysP and CadC) with engineered modifications to the promoter (Pcad) controlling the output gene [3]. This synergistic approach simultaneously improved the sensor's dynamic range and operational pH stability.

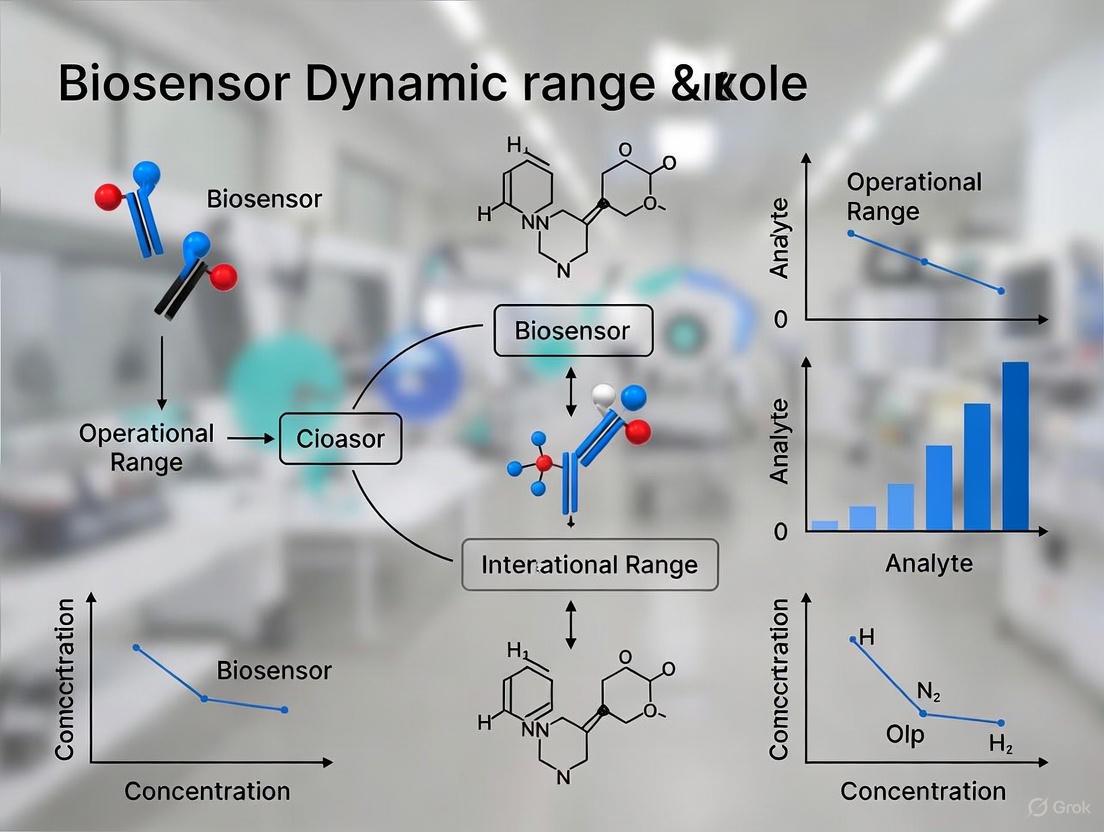

Figure 1: Experimental pathways for enhancing biosensor dynamic range, combining protein engineering and system-level optimization.

Operational Range: The Environmental Stability Domain

The operational range defines the environmental boundaries within which a biosensor functions reliably. It is not a single value but a multi-dimensional space encompassing parameters such as pH, temperature, salinity, and the presence of interfering substances. A biosensor may have an excellent dynamic range under ideal laboratory conditions, but if its performance degrades outside a narrow pH or temperature window, its practical utility is severely limited.

Key Dimensions of the Operational Range

- pH Range: The stability of the biological recognition element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, transcription factor) is often highly pH-dependent. For instance, an initial lysine biosensor in E. coli was found to have a "narrow pH operating range," which was addressed through subsequent engineering [3].

- Temperature Stability: Temperature affects reaction kinetics, protein folding, and the stability of the bioreceptor-transducer complex. The operational temperature range must be specified for applications like industrial bioprocessing or wearable sensors.

- Ionic Strength and Interferents: The concentration of salts and other molecules in the sample matrix can influence biosensor performance by affecting protein structure or generating non-specific signals.

Strategies for Broadening the Operational Range

Engineering a robust operational range focuses on stabilizing the biological components against environmental fluctuations.

- Protein Engineering for Stability: As with dynamic range extension, directed evolution and rational design can be employed to create bioreceptor variants that are functional across a wider pH spectrum or more resistant to denaturation at elevated temperatures. The optimization of the lysine biosensor is a prime example where the operational pH range was broadened [3].

- Material Selection and Sensor Encapsulation: The choice of materials in the sensor's construction can define its operational limits. For example, a glucose sensor designed for stability in interstitial fluid used a nanostructured composite electrode integrated on a printed circuit board, contributing to its excellent durability [4]. Similarly, encapsulating the biological element in a protective polymer hydrogel can shield it from harsh environmental conditions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development and Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Development | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| HaloTag7 (HT7) [2] | Self-labeling protein fusion partner; enables covalent, specific labeling with synthetic fluorophores for FRET-based sensing. | Creating chemogenetic FRET pairs (ChemoX) for tunable biosensors. |

| Silicon Rhodamine (SiR) [2] | Cell-permeable, far-red synthetic fluorophore; used as a FRET acceptor with HaloTag7. | Labeling ChemoG5 to achieve near-quantitative FRET efficiency. |

| CaiF Transcription Factor [1] | Biological recognition element; pivotal transcriptional activator of l-carnitine metabolism. | Core sensing component in an l-carnitine biosensor. |

| LysP & CadC [3] | Lysine transporter and transcription activator; form the core sensing module for lysine. | Constructing a lysine biosensor for dynamic regulation in E. coli. |

| Engineered Promoters [3] | Genetic parts that control the expression level of the output module (e.g., reporter gene). | Fine-tuning the output signal and dynamic range of genetic circuits. |

The Interplay and Trade-offs in Biosensor Design

A critical challenge in biosensor engineering is that optimizing one parameter can inadvertently compromise another. The relationship between dynamic range and operational range is often characterized by trade-offs. For instance, a mutation that increases the affinity of a bioreceptor for its analyte (potentially lowering the LOD and altering the dynamic range) might also make the protein more susceptible to denaturation at higher temperatures (narrowing the operational range). Therefore, a holistic optimization strategy that considers both sets of parameters simultaneously is essential for developing robust biosensors.

The interplay can be visualized as a design space where the goal is to maximize both the dynamic range and the operational range. Successful engineering strategies, such as the multilevel optimization used for the lysine biosensor, address both aspects concurrently by selecting for mutations that improve performance metrics without sacrificing stability under process-relevant conditions [3].

Figure 2: Logical relationships between key biosensor performance parameters, showing synergy and potential trade-offs.

The distinction between dynamic range and operational range is fundamental to the rigorous characterization and successful application of biosensors. The dynamic range defines the sensor's concentration detection window, while the operational range sets the environmental conditions for its reliable use. As evidenced by recent advances, strategies such as directed evolution, chemogenetic FRET pair engineering, and multilevel optimization provide powerful tools to expand both parameters.

Future research will continue to close the gap between laboratory performance and real-world application demands. This will involve developing more sophisticated engineering techniques that minimize trade-offs and create biosensors that are not only exquisitely sensitive across a wide concentration span but also robust enough to function in complex, variable environments like the human body, industrial fermenters, and natural ecosystems. A deep understanding of these key performance parameters is the first step in this engineering journey.

Biomolecular recognition forms the cornerstone of modern biosensing technologies, enabling the highly specific detection of an enormous range of analytes through protein- and nucleic acid-based interactions. The theoretical foundation governing these single-site binding events follows a fundamental hyperbolic relationship between target concentration and receptor occupancy. This relationship, while providing the basis for countless diagnostic applications, imposes a significant inherent constraint known as the 81-fold dynamic range limit. For any biosensor operating under single-site binding conditions, the transition from 10% to 90% site occupancy requires precisely an 81-fold increase in target concentration [5].

This fixed dynamic range presents substantial limitations for real-world applications where target concentrations may vary across several orders of magnitude. Clinical measurements of HIV viral loads, for example, can span from approximately 50 to over 10^6 copies/mL—a range exceeding five orders of magnitude that dwarfs the intrinsic 81-fold dynamic range of single-site binding [5]. Similarly, therapeutic drug monitoring for agents with narrow therapeutic indices (such as cyclosporine and aminoglycosides) requires a precision difficult to achieve with a system necessitating an 81-fold concentration change to transition from minimal to near-maximal signal response [5]. Understanding this fundamental limitation is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals working to optimize biosensor performance for specific applications.

Theoretical Framework and Mathematical Basis

The Law of Mass Action and Binding Isotherm

The 81-fold limit arises directly from the Law of Mass Action applied to reversible bimolecular binding interactions. For a simple equilibrium where a receptor (R) binds to a ligand (L) to form a complex (RL):

R + L ⇌ RL

The dissociation constant Kd is defined as Kd = [R][L]/[RL], where brackets denote concentrations. The fractional occupancy (θ) of receptors is given by:

θ = [L] / (Kd + [L])

This equation generates a hyperbolic binding curve when fractional occupancy is plotted against ligand concentration. The dynamic range is conventionally defined as the concentration interval between 10% and 90% occupancy. Solving the fractional occupancy equation for these values:

When θ = 0.1: [L]₁₀ = Kd/9 When θ = 0.9: [L]₉₀ = 9Kd

The ratio between these concentrations gives the fundamental 81-fold limit:

[L]₉₀ / [L]₁₀ = 9Kd / (Kd/9) = 81

This mathematical relationship demonstrates that the 81-fold dynamic range is an intrinsic property of single-site binding thermodynamics, independent of the specific receptor-ligand pair or absolute affinity [5].

Biosensor Response and Practical Implications

In practical biosensing applications, the receptor occupancy is converted through a transducer into a measurable signal (e.g., optical, electrochemical). The useful dynamic range of the biosensor is therefore constrained by this fundamental 81-fold limit between 10% and 90% signal saturation [5]. The following table summarizes key characteristics of this binding isotherm:

Table 1: Characteristics of Single-Site Binding Isotherm

| Parameter | Symbol/Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Curve Shape | Hyperbolic | Non-linear relationship between concentration and occupancy |

| Half-Maximal Effect | EC₅₀ = Kd | Concentration at 50% receptor occupancy equals Kd |

| Lower Detection Limit | [L]₁₀ = Kd/9 | Concentration at 10% occupancy |

| Upper Detection Limit | [L]₉₀ = 9Kd | Concentration at 90% occupancy |

| Useful Dynamic Range | 81-fold | Fixed ratio between upper and lower detection limits |

This fixed dynamic range creates significant challenges for applications requiring either exceptional sensitivity to small concentration changes or the ability to quantify analytes across wide concentration ranges.

Engineering Strategies to Overcome the 81-Fold Limit

Biological Inspiration and Engineering Approaches

Evolution has developed sophisticated mechanisms to overcome the limitations of single-site binding, inspiring parallel engineering approaches for artificial biosensors. Research has identified three primary strategies for editing the dynamic range of biosensors [5]:

- Extended Dynamic Range: Employing pairs or sets of closely related receptors with different affinities for the same target

- Narrowed Dynamic Range: Creating steep, ultrasensitive responses through mechanisms like sequestration

- Complex Dose-Response: Engineering multi-state systems that respond sensitively only within specific concentration windows

These approaches manipulate the fundamental binding curve to better align with application-specific requirements, whether calling for expanded range, heightened sensitivity within a narrow window, or multi-threshold detection capabilities.

Structure-Switching Receptors

A key advancement in overcoming the 81-fold limit involves engineering structure-switching receptors where binding is coupled to a conformational change. This approach enables tuning of apparent affinity without altering the specific chemical interactions that determine specificity [5].

By stabilizing an alternative "non-binding" state and tuning the switching equilibrium constant, researchers can generate receptor variants spanning a wide affinity range while maintaining identical specificity profiles [5]. This strategy mirrors approaches found in nature, such as intrinsically unfolded proteins that reduce affinity by coupling binding to an unfavorable folding event without compromising specificity [5].

Figure 1: Structure-Switching Receptor Mechanism. Receptors exist in equilibrium between non-binding and binding-competent states. Engineering the switching equilibrium constant (Ks) enables tuning of apparent affinity without altering binding site specificity.

Experimental Implementation and Protocols

Generating Receptor Variants with Tunable Affinities

Molecular beacons (DNA stem-loop structures) serve as an excellent model system for demonstrating dynamic range engineering. The following protocol outlines the generation of affinity variants through stem stability modulation [5]:

Materials:

- DNA oligonucleotides for molecular beacon construction

- Fluorescent reporter (e.g., FAM) and quencher (e.g., BHQ1)

- Thermal cycler or water bath for temperature control

- Buffer reagents (Tris-HCl, MgCl₂, NaCl)

- Target DNA sequences (perfect match and mismatch controls)

Method:

- Design molecular beacon variants with identical target-recognition loops but different stem sequences. Vary the stem length and GC content to create a stability gradient.

- Synthesize and purify molecular beacons with 5' fluorophore and 3' quencher modifications.

- Characterize stem stability using thermal denaturation profiles measuring fluorescence vs. temperature.

- Determine binding affinity for each variant by titrating target DNA and measuring fluorescence recovery. Fit data to binding isotherm to extract Kd values.

- Verify specificity by testing each variant against mismatched targets to ensure discrimination is maintained across affinity variants.

Using this approach, researchers have generated molecular beacon sets with dissociation constants spanning from 0.012 μM to 128 μM—a 10,000-fold affinity range—while maintaining similar specificity profiles (on average 35-fold difference in affinity between matched and single-base mismatched targets) [5].

Extending Dynamic Range Through Receptor Mixing

Rationale: Combining multiple receptor variants with different affinities creates a composite sensor with extended dynamic range. The optimal affinity difference between variants is approximately 100-fold to maximize log-linear range while minimizing deviations from linearity [5].

Protocol:

- Select receptor variants with affinity difference near 100-fold (e.g., molecular beacons with Kd values of 0.1 μM and 10 μM).

- Adjust molar ratios to compensate for differences in signal gain. For variants with 83% and 100% maximum fluorescence change, use approximately 59:41 ratio.

- Mix variants in optimized ratios and characterize response across target concentration range.

- Verify specificity across extended dynamic range using mismatch targets.

This approach has demonstrated extension of dynamic range to 8,100-fold with excellent log-linearity (R²=0.995) and 9-fold signal gain [5]. Further extension to ~900,000-fold (more than four orders of magnitude beyond single receptors) can be achieved by combining four appropriately selected variants in optimized ratios [5].

Table 2: Molecular Beacon Variants for Dynamic Range Engineering

| Variant | Dissociation Constant (Kd) | Relative Affinity | Maximum Fluorescence Change | Application in Mixtures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0GC | 0.012 μM | Highest | ~70% | Extended range, Three-state systems |

| 1GC | 0.11 μM | High | 83% | Extended range (paired with 3GC) |

| 2GC | 1.1 μM | Medium | ~90% | Intermediate in 4-variant mixtures |

| 3GC | 11 μM | Low | 100% | Extended range (paired with 1GC) |

| 5GC | 128 μM | Lowest | ~60% | Extended range, Three-state systems |

Creating Narrowed Dynamic Range and Threshold Sensors

Sequestration Approach: Narrowing dynamic range creates steep, ultrasensitive responses valuable for threshold detection. This employs a non-signaling, high-affinity "depletant" receptor that sequesters target until saturation, after which free target concentration rises dramatically [5].

Protocol:

- Design non-signaling receptor with higher affinity than signaling receptor (e.g., DNA sequence complementary to target but without fluorophore/quencher pair).

- Mix signaling and non-signaling receptors at optimized ratio. The non-signaling receptor acts as a sink until saturated.

- Characterize response to observe threshold effect with compressed dynamic range.

This approach can compress the dynamic range by an order of magnitude and rationally tune threshold response to selected target concentrations [5].

Site-Specific Immobilization for Enhanced Performance

Controlled orientation of receptors on biosensor surfaces significantly impacts performance. Site-specific immobilization using bioorthogonal chemistry addresses limitations of random conjugation [6].

Materials:

- Recombinant protein with incorporated noncanonical amino acid (e.g., AzK)

- Orthogonal pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase (PylRS)/tRNACUAPyl pair

- Alkyne-functionalized biosensor surface

- Biotin linker for detection

Method:

- Incorporate reactive ncAA using stop codon suppression technology at selected position in protein sequence.

- Conjugate with biotin linker via strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC).

- Immobilize on sensor surface through biotin-neutravidin interaction.

- Validate orientation and function using binding assays with target molecule.

This approach has demonstrated 12-fold enhancement in binding sensitivity compared to random immobilization methods [6].

Figure 2: Site-Specific vs. Random Immobilization. Directed immobilization through genetic incorporation of noncanonical amino acids enables optimal orientation of binding sites, significantly enhancing biosensor sensitivity compared to random conjugation approaches.

Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Dynamic Range Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Structure-Switching Receptors | Molecular beacons with variable stem stability | Generate affinity variants while maintaining specificity for extended dynamic range systems [5] |

| Noncanonical Amino Acids | Nε-((2-azidoethoxy)carbonyl)-l-lysine (AzK) | Enable site-specific immobilization via bioorthogonal chemistry for optimized receptor orientation [6] |

| Orthogonal Translation System | PylRS/tRNACUAPyl pair from M. mazei | Genetic incorporation of ncAAs for controlled surface attachment [6] |

| Bioorthogonal Conjugation | Strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) reagents | Directed coupling of receptors to sensor surfaces without interfering with binding function [6] |

| Transcription Factor Scaffolds | CaiF variants for l-carnitine detection | Protein-based biosensors for metabolite detection; platform for directed evolution [1] |

Applications and Recent Advances

Pharmaceutical and Clinical Applications

The ability to engineer biosensor dynamic range has significant implications for pharmaceutical research and clinical diagnostics. Engineered biosensors with extended dynamic ranges are particularly valuable for monitoring therapeutic drugs with narrow therapeutic indices, where precise quantification across clinically relevant concentrations is essential for optimizing efficacy while avoiding toxicity [5]. Similarly, the detection of viral loads that naturally span orders of magnitude, such as HIV monitoring, benefits from expanded dynamic range systems [5].

Threshold sensors with narrowed dynamic ranges offer applications in point-of-care diagnostics where simple "yes/no" or "above/below critical threshold" outputs are clinically sufficient and practically desirable. Three-state dynamic range systems that respond sensitively only when target concentrations fall above or below defined intermediate regimes enable sophisticated monitoring applications in therapeutic drug monitoring and metabolic disorder management [5].

Directed Evolution Approaches

Recent research has complemented the structure-switching and receptor mixing approaches with directed evolution strategies. For example, engineering of the transcription factor CaiF for l-carnitine detection has demonstrated substantial improvements in biosensor performance. Through computational design and functional diversity-oriented substitutions, researchers developed CaiF variants with 1000-fold wider response range (from 10^-4 mM to 10 mM) and 3.3-fold higher output signal intensity compared to the wild-type biosensor [1].

This directed evolution approach involved:

- Computer-aided design of CaiF structure and DNA binding site simulation

- Alanine scanning to validate predicted functional residues

- Diversity-oriented substitution at key positions to generate functional variants

- High-throughput screening to identify variants with improved dynamic range

The success of this methodology highlights the potential for combining rational design with directed evolution to overcome fundamental limitations in biosensor performance [1].

The fundamental 81-fold dynamic range limit represents a significant constraint inherent to single-site binding interactions that underpins many biosensing technologies. Through understanding of this thermodynamic principle and implementation of sophisticated engineering strategies—including structure-switching receptors, optimized receptor mixing, sequestration mechanisms, and site-specific immobilization—researchers can now rationally design biosensors with tailored dynamic ranges optimized for specific applications. These approaches, inspired by natural systems and enhanced through modern protein engineering and directed evolution methodologies, enable unprecedented control over biosensor response characteristics. The continued refinement of these strategies promises to expand further the utility of biosensors in pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring applications where precise quantification across wide concentration ranges is required.

Dynamic range, a fundamental performance metric for biosensors, is critically defined as the span between the minimal and maximal detectable signals [7]. In both industrial biomanufacturing and clinical diagnostics, this parameter directly determines the efficacy of high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns and the accuracy of diagnostic results. This technical review examines the profound implications of dynamic range on biosensor functionality, detailing established and emerging methodologies for its optimization. We present quantitative data linking expanded dynamic range to enhanced screening efficiency and diagnostic reliability, supported by experimental protocols and reagent specifications to provide researchers with a practical framework for biosensor development and implementation.

Biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect specific analytes [8]. Their performance is characterized by several interdependent parameters:

- Dynamic Range: The concentration interval over which the biosensor produces a measurable and usable signal response, typically bounded by the limit of detection (LOD) at the lower end and signal saturation at the upper end [7].

- Operating Range: The specific concentration window where the biosensor performs with optimal accuracy and precision, often a subset of the full dynamic range [7].

- Sensitivity: The magnitude of output signal change per unit change in analyte concentration.

- Response Time: The speed at which the biosensor reaches its maximum signal after analyte exposure [7].

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: The ratio between the meaningful signal and the underlying background noise, determining detection clarity [7].

These metrics collectively define biosensor utility across applications ranging from metabolic engineering to point-of-care diagnostics. However, dynamic range holds particular significance as it establishes the fundamental boundaries within which a biosensor can operate effectively.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Biosensor Characterization

| Metric | Definition | Impact on Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Span between minimal and maximal detectable signals [7] | Determines the concentration window for reliable detection |

| Operating Range | Concentration window for optimal performance [7] | Defines practical utility limits for specific applications |

| Sensitivity | Signal change per unit analyte concentration change | Affects ability to distinguish small concentration differences |

| Response Time | Speed of signal response to analyte exposure [7] | Critical for real-time monitoring and rapid screening |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Ratio of meaningful signal to background noise [7] | Impacts detection reliability and measurement confidence |

The Critical Role of Dynamic Range in High-Throughput Screening

High-throughput screening relies on the rapid assessment of thousands to millions of biological variants to identify candidates with desired properties. In this context, biosensor dynamic range becomes a throughput-determining factor.

Pathway Optimization and Strain Development

In metabolic engineering, biosensors are indispensable for optimizing synthetic pathways and screening strain libraries. A restricted dynamic range can mask superior producers during screening, as variants producing metabolite concentrations beyond the sensor's detection上限 fail to generate discriminable signals [7]. This necessitates multiple screening rounds with sample dilution or different sensors, drastically reducing throughput and increasing resource requirements. Furthermore, biosensors with nonideal dose–response characteristics or high signal noise exacerbate scalability challenges by increasing false positives or masking true high-performing strains [7].

Advanced Screening Methodologies

Emerging technologies are addressing these limitations through sophisticated screening platforms. The BeadScan system combines droplet microfluidics with automated fluorescence imaging to encapsulate, express, and screen vast libraries of biosensor variants [9]. This platform enables parallel evaluation of multiple biosensor features—including dynamic range, affinity, and specificity—across thousands of variants, representing an order-of-magnitude increase in screening throughput [9].

Figure 1: The BeadScan workflow for high-throughput biosensor screening utilizes gel-shell beads (GSBs) as microscale dialysis chambers to assay thousands of variants against multiple analyte conditions in parallel [9].

Dynamic Range and Diagnostic Precision

In diagnostic applications, dynamic range directly influences clinical accuracy and utility across diverse patient populations and disease stages.

Impact on Diagnostic Accuracy

A biosensor with insufficient dynamic range may fail to detect clinically significant analyte concentrations falling outside its detection window, leading to false negatives in hypersecreting conditions or false positives due to nonspecific binding in complex matrices like serum [8]. This is particularly critical for biomarkers with wide physiological and pathological concentration ranges. For example, C-reactive protein (CRP) circulates at concentrations ranging from μg/mL to hundreds of μg/mL during infection [8]. A biosensor with a narrow dynamic range would require multiple dilutions for accurate quantification across this span, increasing assay complexity and potential for error.

Mitigating Nonspecific Binding

Nonspecific binding (NSB) presents a significant challenge in label-free biosensors, particularly when analyzing complex biological samples. NSB from serum constituents can produce signals indistinguishable from specific binding events, effectively reducing the functional dynamic range and compromising diagnostic precision [8]. Implementation of appropriate reference channels with optimized negative controls (e.g., isotype-matched antibodies) enables subtraction of NSB contributions, preserving the integrity of the biosensor's dynamic range in complex media [8].

Enhancing Precision Through Computational Approaches

Innovative computational methods are now addressing dynamic range limitations by extracting more information from biosensor responses. Theory-guided deep learning leverages domain knowledge to improve biosensor accuracy and speed using dynamic signal changes [10]. By training recurrent neural networks with cost function supervision based on biosensing theory, researchers have achieved 98.5% average prediction accuracy for microRNA quantification across nanomolar to femtomolar concentrations—a range spanning six orders of magnitude [10]. This approach significantly reduces false-negative and false-positive results while enabling accurate concentration determination from initial transient responses, effectively expanding the usable dynamic range.

Experimental Approaches for Dynamic Range Optimization

Multiple strategic approaches exist for optimizing the dynamic range of biosensors, from molecular engineering to directed evolution.

Transcription Factor Engineering

Protein-based biosensors, particularly those utilizing transcription factors (TFs), offer numerous engineering handles for dynamic range modulation. Research on the CaiF transcription factor-based biosensor for L-carnitine detection demonstrates that rational engineering of DNA binding domains can dramatically expand dynamic range [1]. Through computer-aided design and alanine scanning, researchers identified key residues affecting DNA binding affinity. The variant CaiF-Y47W/R89A exhibited a 1000-fold wider concentration response range (10⁻⁴ mM to 10 mM) with a 3.3-fold higher output signal intensity compared to the wild-type biosensor [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Engineered CaiF Biosensor Variants

| Biosensor Variant | Dynamic Range | Signal Intensity | Key Structural Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type CaiF | Reference range | Reference intensity | Native DNA-binding domain |

| CaiF-Y47W/R89A | 1000-fold wider [1] | 3.3-fold higher [1] | Dual substitution in DNA interaction interface |

RNA-Based Biosensor Design

RNA-based biosensors, including riboswitches and toehold switches, provide complementary advantages for dynamic range tuning. Their compact size and reversible ligand binding characteristics facilitate integration into metabolic regulation circuits [7]. Toehold switches offer particularly programmable dynamic range control through careful design of the trigger RNA binding region, enabling logic-gated control of metabolic pathways in microbial factories [7].

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Comprehensive dynamic range optimization typically follows an iterative design-build-test cycle, incorporating both rational design and screening approaches.

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for biosensor dynamic range optimization combines rational design with high-throughput screening and data-driven modeling in an iterative refinement cycle [7] [1] [9].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development and implementation of biosensors with optimized dynamic ranges requires specific reagent solutions and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | Protein-based biosensor scaffolds for metabolite detection | CaiF for L-carnitine sensing [1] |

| RNA Scaffolds | Modular, programmable biosensors with tunable response | Riboswitches, toehold switches [7] |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | High-yield protein synthesis for biosensor production | PUREfrex2.0 system [9] |

| Microfluidic Components | High-throughput screening platform fabrication | Gel-shell beads (GSBs), droplet generators [9] |

| Reference Control Probes | Nonspecific binding correction in label-free biosensors | Isotype-matched antibodies, BSA, anti-FITC [8] |

| Surface Chemistry Reagents | Sensor functionalization and biomolecule immobilization | Silane chemistry for non-planar surfaces [11] |

Dynamic range stands as a critical determinant of biosensor performance in both high-throughput screening and diagnostic applications. The concentration window over which a biosensor operates reliably directly impacts screening efficiency, strain development timelines, diagnostic accuracy, and clinical utility. Through integrated approaches combining molecular engineering, advanced screening platforms, and computational methods, researchers can systematically optimize this fundamental parameter. The continued refinement of biosensors with expanded dynamic ranges will accelerate advancements across synthetic biology, biomanufacturing, and precision medicine, enabling more sensitive detection, more accurate quantification, and more reliable decision-making across biological research and clinical practice.

Biosensors are fundamental biological tools that combine a sensor module, which detects specific intracellular or environmental signals, with an actuator module, which drives a measurable or functional response [7]. These devices are indispensable in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology for enabling real-time monitoring, high-throughput screening, and dynamic regulation of metabolic pathways [7]. The performance of biosensors is critically evaluated through key metrics such as dynamic range (the span between minimal and maximal detectable signals), operating range (the concentration window for optimal performance), response time, and signal-to-noise ratio [7]. Within this framework, transcription factors, riboswitches, and two-component systems represent core natural mechanisms that have been engineered to construct sophisticated synthetic biosensing systems. This review provides an in-depth technical overview of these mechanisms, emphasizing their operational principles, quantitative performance characteristics, and experimental methodologies for engineering enhanced dynamic and operational ranges.

Core Biosensor Mechanisms

Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

Sensing Principle: Transcription factor (TF)-based biosensors function through ligand-induced allosteric regulation. The binding of a specific target metabolite to the transcription factor induces a conformational change, enabling or disabling its binding to a specific DNA operator sequence, thereby regulating the expression of a downstream reporter gene [7] [12]. This mechanism allows for direct genetic regulation in response to metabolite levels.

Key Characteristics: TFs typically exhibit moderate sensitivity and are suitable for high-throughput screening due to their direct coupling to gene expression [7]. A significant advantage is their broad analyte range, capable of sensing diverse compounds including alcohols, flavonoids, and organic acids [7]. Their performance is often characterized by a dose-response curve, which defines sensitivity and dynamic range.

Engineering Methodologies:

- Dynamic Range Tuning: The dynamic and operational ranges of TF-based biosensors can be tuned by exchanging promoters and ribosome binding sites (RBS), or by altering the number and position of the operator region within the genetic construct [7].

- Specificity Engineering: The chimeric fusion of DNA-binding domains and ligand-binding domains from different transcription factors has been successfully used to engineer novel biosensor specificities [7].

- Directed Evolution: High-throughput techniques like fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), combined with directed evolution strategies, are employed to improve biosensor sensitivity and specificity. This involves creating mutant libraries of the transcription factor and screening for variants with desired response characteristics [7] [12].

Riboswitches

Sensing Principle: Riboswitches are structured RNA elements located in the 5' untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNAs. They sense intracellular metabolites through direct ligand binding, which induces a conformational change in the RNA structure [7]. This structural switch then affects downstream gene expression by either activating or repressing translation initiation or transcription termination.

Key Characteristics: Riboswitches are compact, tunable, and often reversible, making them ideal for integrating into metabolic regulation circuits [7]. They are particularly useful for sensing fundamental intracellular metabolites such as nucleotides and amino acids, and they generally exhibit faster response times compared to protein-based systems due to the absence of a protein synthesis step [7] [12].

Engineering Methodologies:

- Sequence Rational Design: The sequence of the aptamer domain (responsible for ligand binding) and the expression platform (responsible for the structural switch) can be rationally designed or mutated to alter ligand specificity, affinity, and the dynamic range of the response.

- High-Throughput Screening: As with TFs, generating mutant riboswitch libraries and screening them via FACS or other selection methods is a common approach to isolate variants with improved characteristics, such as a wider dynamic range or altered ligand specificity [12].

Two-Component Systems (TCSs)

Sensing Principle: Two-component systems are modular signaling pathways typically comprising a membrane-associated sensor kinase and a cytoplasmic response regulator. Upon detection of an extracellular or intracellular signal (e.g., ions, pH, small molecules), the sensor kinase autophosphorylates and then transfers the phosphate group to the response regulator [7]. The phosphorylated response regulator then activates the transcription of target genes.

Key Characteristics: TCSs are highly adaptable and specialized for environmental signal detection [7]. Their modular architecture allows for the engineering of hybrid systems where the sensor domain of one kinase is fused to the regulatory domain of another, enabling the creation of novel input-output relationships.

Engineering Methodologies:

- Domain Swapping: The sensor domains of different kinases can be swapped to create chimeric TCSs that respond to new environmental or intracellular cues [7].

- Promoter and RBS Engineering: The output of a TCS can be fine-tuned by engineering the promoter and RBS of the gene(s) controlled by the response regulator, thereby adjusting the amplitude of the output signal within the operational range [7].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Biosensor Mechanisms

| Category | Biosensor Type | Sensing Principle | Key Advantages | Typical Analyte Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Based | Transcription Factors (TFs) | Ligand binding induces DNA interaction to regulate gene expression | Suitable for high-throughput screening; broad analyte range | Alcohols, flavonoids, organic acids [7] |

| Protein-Based | Two-Component Systems (TCSs) | Sensor kinase autophosphorylates and transfers signal to response regulator | High adaptability; environmental signal detection; modular signaling | Ions, pH, small molecules [7] |

| RNA-Based | Riboswitches | Ligand-induced RNA conformational change affects translation | Compact; tunable response; reversible; fast response time | Nucleotides, amino acids [7] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics and Engineering

A critical aspect of biosensor development is the rigorous characterization and engineering of its performance parameters. The following table summarizes the key metrics and common strategies for their optimization.

Table 2: Key Biosensor Performance Parameters and Engineering Strategies

| Performance Parameter | Definition | Engineering & Tuning Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | The ratio between the maximal and minimal output signals [7]. | Promoter engineering, RBS tuning, plasmid copy number variation [7]. |

| Operating Range | The concentration window of the analyte where the biosensor performs optimally [7]. | Operator site position/number manipulation, directed evolution of ligand-binding domain [7]. |

| Response Time | The speed at which the biosensor reaches its maximum output signal after analyte exposure [7]. | Using faster-acting components (e.g., riboswitches), hybrid system design [7]. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | The clarity and reliability of the output signal under constant conditions [7]. | Optimizing expression levels of sensor and reporter components to minimize basal expression [7]. |

Experimental Protocol for Characterizing Dose-Response:

- Strain Cultivation: Grow the engineered microbial strain harboring the biosensor to mid-exponential phase.

- Analyte Exposure: Aliquot the culture into multi-well plates and expose to a concentration gradient of the target analyte. Include a negative control (no analyte).

- Output Measurement: For fluorescent reporters, measure fluorescence intensity over time using a plate reader. For other reporters (e.g., colorimetric, luminescent), use the appropriate detector.

- Data Analysis: Normalize the output signal (e.g., fluorescence) to cell density (e.g., OD600). Plot the normalized output against the logarithm of the analyte concentration.

- Curve Fitting: Fit the data to a sigmoidal function (e.g., Hill equation) to extract key parameters: minimum and maximum output (dynamic range), EC50 (sensitivity), and Hill coefficient (cooperativity).

Visualization of Biosensor Mechanisms and Workflows

Transcription Factor Biosensor Mechanism

Two-Component System Biosensor Mechanism

High-Throughput Screening Workflow for Biosensor Engineering

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for the construction and testing of genetic biosensors.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Allosteric Transcription Factors (aTFs) | Core sensing element for protein-based metabolite detection; can be sourced from native hosts or engineered for new specificities [12]. |

| Riboswitch DNA Sequences | Synthetic DNA fragments encoding the aptamer and expression platform; used to construct RNA-based sensors for intracellular metabolites [7] [12]. |

| Plasmid Vectors (various copy numbers) | Backbone for biosensor circuit construction; plasmid copy number is a key variable for tuning biosensor sensitivity and dynamic range [7]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins (eGFP, mCherry, etc.) | Provide a measurable output signal for high-throughput screening and quantitative characterization of biosensor performance [7] [12]. |

| Microfluidic Droplet Generation Systems | Enable high-throughput screening by encapsulating single cells or biosensor reactions in picoliter droplets for analysis and sorting (e.g., FADS) [12]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) Systems | In vitro systems for rapid prototyping of biosensors and pathways, bypassing cellular constraints and allowing for direct control of the reaction environment [12]. |

Transcription factors, riboswitches, and two-component systems provide a versatile toolkit for constructing genetic biosensors with applications ranging from metabolic engineering to diagnostics. The effective deployment of these biosensors relies on a deep understanding of their inherent mechanisms and a systematic approach to engineering their performance parameters, particularly the dynamic and operational ranges. By leveraging structured experimental protocols, high-throughput screening methodologies, and computational design, researchers can continually refine these biological devices, enhancing their reliability and expanding their applicability in both industrial and therapeutic contexts.

Engineering and Application: Strategies for Extending and Tailoring Biosensor Ranges

In the fields of therapeutic drug development and basic cellular research, the ability to accurately measure biochemical signals within their native, complex environments is paramount. Biosensors, which convert biological events into measurable signals, are foundational tools for this purpose. A biosensor's dynamic range—the span between the minimum and maximum concentrations of a target molecule it can accurately detect—directly determines its utility. A wide dynamic range is crucial for capturing the full spectrum of physiological fluctuations, from subtle basal signaling to robust, pathway-saturated responses. However, many naturally occurring and first-generation engineered biosensors often possess an insufficient dynamic range, leading to signal saturation and an inability to resolve critical quantitative differences at the upper and lower limits of target concentration.

This technical guide explores the strategy of strategic mixing, a method involving the deliberate combination of receptor variants with distinct ligand-binding affinities to construct a composite biosensor system with a significantly widened effective dynamic range. Framed within a broader research thesis on biosensor operational range, this approach moves beyond the limitations of single-component sensors. By creating a system where different receptor variants are active across different concentration windows, researchers can achieve a more linear and extensive response profile. This guide provides a detailed examination of the underlying principles, quantitative characterization methods, and practical experimental protocols for implementing this powerful technique, equipping scientists with the knowledge to deploy it in advanced drug screening and signaling studies.

Core Principles: Receptor Affinity and Composite Response

The theoretical foundation of strategic mixing rests on the well-defined binding characteristics of individual receptor-ligand pairs. A receptor's affinity for its ligand, typically quantified by its dissociation constant (Kd), defines the concentration range over which it is most sensitive to changes in ligand concentration. A receptor with a low Kd (high affinity) will saturate at relatively low ligand concentrations, making it ideal for detecting subtle changes in low-abundance analytes. Conversely, a receptor with a high Kd (low affinity) will only begin to respond at higher ligand concentrations and will resist saturation, making it suitable for measuring robust signals.

The Strategic Mixing Hypothesis

The central hypothesis of strategic mixing is that by co-deploying multiple receptor variants—each with a deliberately tuned and distinct Kd for the same target ligand—within a single experimental system, their individual responsive ranges can be made to overlap and combine. The resulting composite output is a summation of their individual response curves. When these variants are coupled to the same reporting mechanism (e.g., fluorescence), the system's overall dynamic range is extended to cover a much broader concentration spectrum than any single variant could achieve alone. This method effectively linearizes the sensor's response over a wider interval, enhancing the resolution and accuracy of quantitative measurements across diverse experimental conditions, from the tumor microenvironment to intracellular second-messenger signaling.

Table 1: Characteristics of Receptor Variants for Strategic Mixing

| Variant Name | Theoretical Kd (nM) | Optimal Sensing Range | Primary Role in Composite System |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Affinity (Variant H) | 10 - 50 nM | Low (Basal) Concentrations | Provides sensitivity to subtle, low-level changes in signaling. |

| Medium-Affinity (Variant M) | 200 - 500 nM | Mid (Physiological) Concentrations | Covers the core range of active biological fluctuations. |

| Low-Affinity (Variant L) | 1000 - 5000 nM | High (Saturated) Concentrations | Prevents saturation and captures data at peak concentrations. |

Quantitative Characterization of Biosensor Performance

To effectively design and implement a strategic mixing protocol, a rigorous quantitative assessment of each receptor variant's performance is non-negotiable. This involves determining key parameters that define the sensor's operational envelope. The most critical of these is the dissociation constant (Kd), which provides a direct measure of binding affinity. Furthermore, the dynamic range of each sensor must be precisely measured as the fold-change in output signal between the minimal (ligand-free) and maximal (saturating ligand) states. For fluorescent biosensors, this is often reported as the ratio of fluorescence intensity or the change in Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) efficiency.

Recent advances in biosensor engineering, particularly using directed evolution, have demonstrated the dramatic improvements possible in these metrics. For instance, the development of the cdGreen2 biosensor for the bacterial second messenger c-di-GMP involved iterative cycles of mutagenesis and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). This process yielded a final biosensor variant with a 12-fold increase in fluorescence intensity upon ligand binding and a Kd of 214 nM, showcasing a combination of high sensitivity and a wide dynamic range that is ideal for such applications [13]. Quantitative data, as summarized in the table below, must be collected under standardized conditions to enable rational selection of variants for mixing.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Biosensor Performance Metrics

| Performance Parameter | Definition & Measurement Method | Target Value for Strategic Mixing |

|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Constant (Kd) | Ligand concentration at half-maximal sensor response. Determined from dose-response curve fitting. | Variants should have Kd values spaced across a log scale (e.g., 50 nM, 500 nM, 5 µM). |

| Dynamic Range (Fold-Change) | Maximal signal output / Minimal signal output. Measured via fluorometry or plate reader. | A high fold-change (>5) is desirable for each variant to ensure a strong composite signal. |

| Brightness (Molecular Brightness) | Fluorescence intensity per sensor molecule. Measured relative to standard fluorescent proteins. | High brightness is critical for signal-to-noise ratio in cell-based assays. |

| Ligand Binding Kinetics (kon, koff) | Rates of ligand association and dissociation. Measured via stopped-flow or surface plasmon resonance. | Variants with similar kon but different koff rates often yield the desired Kd spacing. |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide to Strategic Mixing

The following section outlines a detailed, actionable protocol for implementing the strategic mixing approach. This methodology is adapted from best practices in protein engineering and biosensor validation, drawing on techniques used in the development of cutting-edge tools like transcription factor-based biosensors [14] and FRET-based signaling reporters [15].

Phase 1: Affinity Variant Generation and Selection

- Generate Receptor Variants: Create a library of receptor variants with a range of affinities for your target ligand. This can be achieved through:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Target residues in the ligand-binding pocket based on structural data (e.g., from PDB files 6E2Q, 4BSK used in computational design [16]).

- Directed Evolution: Use iterative FACS under alternating high/low ligand regimes to select for desired affinities, as successfully demonstrated with the cdGreen2 biosensor [13].

- Characterize Individual Variants: Express and purify each candidate variant. Using a plate reader or fluorometer, generate a dose-response curve by measuring the sensor's output (e.g., fluorescence intensity at 513 nm for GFP-based sensors) across a logarithmic concentration range of the purified ligand (e.g., 1 nM to 100 µM).

- Determine Kd and Dynamic Range: Fit the dose-response data to a sigmoidal curve (e.g., Hill equation) to calculate the Kd and dynamic range (fold-change) for each variant. Select at least three variants whose Kd values are spaced approximately one order of magnitude apart.

Phase 2: Composite System Assembly and Validation

- Define Mixing Ratios: Based on the characterized Kd values and dynamic ranges, establish a theoretical mixing ratio. A starting point is a 1:1:1 total signal contribution ratio, which may require adjusting the actual plasmid DNA or protein amounts based on the relative brightness of each variant.

- Co-Express Variants: In your chosen cellular system (e.g., HEK293T cells for testing, or a relevant therapeutic cell line like engineered T cells [17]), co-transfect the expression plasmids for the selected receptor variants. Ensure the use of a single, unified reporter (e.g., a single fluorescent protein type) to avoid spectral cross-talk.

- Validate Composite Output: Stimulate the cells with a wide range of ligand concentrations and measure the composite output signal using live-cell imaging [15] or flow cytometry. Compare the resulting dose-response curve to those of the individual variants. A successful mix will show a linear response over a significantly wider concentration range than any single component.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful application of the strategic mixing methodology relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details the key components required for the experiments described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Strategic Mixing

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Engineering & Cloning | CRISPR/Cas9 system [17], site-directed mutagenesis kit, rAAV6 vector [17] | Used for generating and integrating receptor variants with precise genomic modifications. |

| Biosensor Expression & Purification | Mammalian expression vectors (e.g., pcDNA3.4), HEK293T cells, protein purification columns (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins) | For producing and isolating functional receptor variants for in vitro characterization. |

| Ligand Binding & Characterization | Purified target ligand, plate reader (e.g., for FRET/fluorescence), surface plasmon resonance (SPR) instrument | Essential for generating dose-response curves and determining Kd, kon, and koff. |

| Cell-Based Assay & Readout | Flow cytometer, live-cell imaging microscope, deep learning-based image analysis software [15] | Enables high-throughput screening and real-time, multiplexed tracking of biosensor activity in live cells. |

| Data Analysis & Modeling | R package for non-linear mixed models (e.g., SynergyLMM [18]), GraphPad Prism, Python with SciPy | Critical for fitting dose-response data, calculating synergy, and performing statistical power analysis. |

The strategic mixing of receptor variants represents a powerful and rational engineering approach to overcome a fundamental limitation in molecular biosensing: restricted dynamic range. By moving beyond single-component systems to embrace defined heterogeneity, researchers can construct biosensors capable of delivering accurate, quantitative data across the vast spectrum of analyte concentrations found in complex biological settings. This methodology, underpinned by rigorous quantitative characterization and detailed experimental protocols, provides a clear pathway for enhancing drug screening assays, deciphering nuanced cell signaling networks, and developing more robust therapeutic cell products. As the toolbox of protein engineering and computational design continues to expand, the deliberate design of multi-affinity sensor systems will undoubtedly become a standard strategy for pushing the boundaries of measurable biology.

Biosensors are analytical devices that combine a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect specific analytes, enabling real-time monitoring in fields from biomedicine to industrial biotechnology [19]. A biosensor's performance is critically dependent on its dynamic range—the concentration interval over which the sensor can produce a quantifiable response—and its operational range, which defines the conditions under which it functions reliably. A restricted dynamic range poses significant limitations in practical applications, potentially leading to inaccurate measurements and missed detections when analyte concentrations fall outside the sensor's narrow detection window [1].

The CaiF-based biosensor for L-carnitine presents a compelling case study in addressing these challenges. L-carnitine is a quaternary amine essential for eukaryotic metabolism, primarily involved in the oxidative decomposition of medium- and long-chain fatty acids to provide cellular energy [1] [20]. Its importance in health and nutrition has led to widespread use in healthcare products and food additives, creating a pressing need for robust detection methods. The transcriptional activator CaiF, a pivotal component in L-carnitine metabolism, is naturally activated by crotonobetainyl-CoA, a key intermediate in the carnitine metabolic pathway [1]. While this natural mechanism provided the foundation for a sophisticated biosensor, its initially restricted detection range limited its utility in practical scenarios, necessitating protein engineering interventions to enhance its performance characteristics.

The Core Engineering Challenge: CaiF's Restricted Detection Range

The fundamental limitation of the native CaiF-based biosensor was its relatively constrained detection range, which created specific practical application barriers [1]. In industrial biotechnology, particularly in optimizing L-carnitine production processes, a narrow dynamic range prevents comprehensive monitoring of metabolic fluxes across varying fermentation conditions. This restriction hinders the ability to capture the full spectrum of analyte concentrations present in complex biological systems, ultimately limiting the biosensor's utility in bioprocess optimization and metabolic engineering.

The core engineering objective was therefore to substantially extend both the dynamic and operational ranges of the CaiF biosensor while simultaneously enhancing its output signal intensity. This multi-faceted improvement would enable more accurate monitoring of L-carnitine concentrations across diverse application scenarios, from industrial bioreactors to research laboratories. The technical approach combined computational protein design with directed evolution methodologies, creating a synergistic engineering strategy that leveraged both rational design and screening-based optimization.

Experimental Strategy: An Integrated Computational and Directed Evolution Approach

Phase 1: Computational Analysis and Target Identification

The protein engineering initiative began with a comprehensive structural analysis of CaiF to identify key residues involved in its DNA-binding and activation mechanisms. Researchers employed computer-aided design to formulate the structural configuration of CaiF and simulate its DNA binding site [1] [20]. This computational modeling provided critical insights into the molecular architecture governing CaiF's function as a transcriptional activator.

To validate the computational predictions experimentally, the team performed alanine scanning mutagenesis—a systematic technique where individual residues are replaced with alanine to assess their functional contribution without altering the protein's main chain conformation. This verification step confirmed the importance of specific residues in DNA binding and provided a foundation for subsequent engineering efforts [1].

Phase 2: Diversity-Oriented Site-Directed Mutagenesis

With key functional residues identified, researchers implemented a Functional Diversity-Oriented Volume-Conservative Substitution Strategy [1]. This sophisticated mutagenesis approach focused on substituting target residues with amino acids of similar molecular volume to minimize structural perturbations while exploring diverse chemical properties. The strategy aimed to create a comprehensive library of CaiF variants with modified functional characteristics, particularly targeting residues involved in the allosteric regulation and DNA-binding affinity.

Phase 3: High-Throughput Screening and Characterization

The resulting mutant library underwent rigorous high-throughput screening to identify variants with improved biosensing capabilities. Screening focused on two primary performance metrics: (1) expanded concentration response range, and (2) enhanced output signal intensity. Successful variants were isolated and characterized to quantify their performance improvements relative to the wild-type CaiF biosensor, leading to the identification of the superior-performing CaiFY47W/R89A double mutant [1].

Diagram Title: CaiF Biosensor Engineering Workflow

Results: Quantifiable Enhancement of Biosensor Performance

The protein engineering effort yielded significant improvements in the CaiF biosensor's performance metrics. The engineered variant CaiFY47W/R89A demonstrated exceptional characteristics that substantially exceeded the capabilities of the wild-type biosensor.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Wild-Type vs. Engineered CaiF Biosensor

| Performance Metric | Wild-Type CaiF Biosensor | Engineered CaiFY47W/R89A | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Range | Not specified in available data | 10-4 mM – 10 mM | 1000-fold wider range |

| Output Signal Intensity | Baseline reference | 3.3-fold higher | 3.3-fold enhancement |

| Lower Detection Limit | Not specified in available data | 10-4 mM (0.1 μM) | Substantially improved sensitivity |

| Upper Detection Limit | Not specified in available data | 10 mM | Suitable for high concentration monitoring |

The engineered biosensor achieved a remarkable 1000-fold wider concentration response range compared to the control biosensor, spanning from 10-4 mM to 10 mM [1]. This extraordinary expansion enables the detection of L-carnitine across six orders of magnitude, making the biosensor applicable to diverse scenarios from trace analysis to concentrated industrial samples. Additionally, the 3.3-fold enhancement in output signal intensity significantly improved the biosensor's signal-to-noise ratio, facilitating more accurate and reliable measurements [1].

The strategic mutations Y47W and R89A represent key modifications that altered CaiF's functional properties. The tyrosine to tryptophan substitution at position 47 (Y47W) likely enhanced hydrophobic interactions or π-stacking within the protein structure, while the arginine to alanine change at position 89 (R89A) probably reduced steric hindrance or electrostatic repulsion, collectively optimizing the protein's conformational dynamics and DNA-binding characteristics.

The L-Carnitine/CaiF Signaling Pathway: Molecular Mechanism

Understanding the molecular mechanism of the CaiF biosensor requires examining the natural signaling pathway it exploits. The biosensor capitalizes on the native biological pathway where L-carnitine metabolism generates crotonobetainyl-CoA, which serves as the actual activator for the CaiF transcription factor.

Diagram Title: L-Carnitine/CaiF Biosensor Signaling Pathway

The pathway begins with the metabolic conversion of L-carnitine to crotonobetainyl-CoA, a key intermediate in the carnitine metabolic pathway [1]. This metabolite serves as the natural activator of CaiF, binding to the transcription factor and inducing a conformational change that enables it to bind specific DNA sequences. In the engineered biosensor system, this binding event triggers the expression of a reporter gene, which generates a measurable signal output proportional to the L-carnitine concentration present in the system.

The CaiFY47W/R89A mutations optimize this signaling pathway by enhancing the transcription factor's responsiveness to activator binding and its subsequent DNA-binding efficiency. The expanded dynamic range suggests that the mutations may have altered the allosteric regulation of CaiF, reducing its activation threshold while maintaining specificity, thereby allowing it to respond to a broader concentration range of the activating metabolite.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Biosensor Engineering

The successful engineering of the CaiF biosensor relied on several key research reagents and methodologies that enabled the precise modification and characterization of the protein's function.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Engineering

| Research Reagent/Methodology | Function in CaiF Engineering | Technical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computer-Aided Protein Design | Structural configuration formulation and DNA binding site simulation | Enabled rational identification of mutation targets prior to experimental validation |

| Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis | Functional validation of key residues in DNA binding and allostery | Systematically determined residue-specific contributions to CaiF function |

| Volume-Conservative Substitution Strategy | Diversity-oriented mutagenesis of key functional sites | Maximized functional diversity while minimizing structural perturbations |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Identification of variants with enhanced dynamic range | Enabled rapid assessment of mutant library for desired biosensor properties |

| Reporter Gene Systems | Quantification of biosensor performance and output signal | Provided measurable output correlating with CaiF activation and DNA binding |

These research tools created an integrated engineering pipeline that combined computational prediction with experimental validation. The computer-aided design identified potential optimization targets, while the specialized mutagenesis strategies created diverse variant libraries. Finally, high-throughput screening enabled the identification of superior performers from these libraries, yielding the enhanced CaiFY47W/R89A variant.

Implications and Future Perspectives in Biosensor Technology

The successful engineering of the CaiF biosensor demonstrates the transformative potential of protein engineering in overcoming fundamental limitations in biosensor technology. The 1000-fold expansion in dynamic range achieved through the CaiFY47W/R89A variant represents a significant advancement for L-carnitine detection, with direct implications for improving L-carnitine production processes [1]. Similar engineering approaches could be applied to other biosensor systems facing dynamic range limitations.

The field of biosensor engineering is increasingly incorporating artificial intelligence methodologies to further enhance development capabilities. AI algorithms can process complex biological data to identify patterns and predict optimal mutation sites, potentially accelerating the engineering process [21]. Machine learning approaches are being integrated into biosensor technology to enhance sensitivity, specificity, and stability by filtering out undesirable noise and signals to provide more accurate and reliable measurements [21]. These computational approaches may complement traditional directed evolution methods, creating hybrid engineering strategies that leverage both computational prediction and experimental screening.

Future developments in biosensor technology will likely focus on creating multiplexed sensing systems capable of detecting multiple analytes simultaneously. The color tunability demonstrated by recent biosensor platforms [2] could be integrated with dynamic range engineering to create versatile multi-analyte detection systems. Furthermore, the integration of biosensors with organ-on-chip technologies and microfluidic systems [22] presents opportunities for creating more physiologically relevant screening platforms for drug development and toxicology studies.

As biosensor technology continues to evolve, the protein engineering strategies demonstrated in the CaiF case study provide a valuable template for overcoming performance limitations in molecular sensing systems. The integration of computational design, directed evolution, and AI-assisted optimization represents a powerful paradigm for the next generation of biosensors with enhanced capabilities for biomedical research, industrial biotechnology, and diagnostic applications.

In the field of synthetic biology, the engineering of predictable and high-performance genetic circuits remains a fundamental challenge. Biosensor performance, particularly its dynamic range and operational range, is critically dependent on the precise tuning of its genetic components. The promoter, which regulates transcriptional initiation, and the ribosome binding site (RBS), which controls translational efficiency, serve as the primary genetic dials for modulating circuit behavior [23]. While extensive research has focused on forward engineering approaches using characterized parts, the integration of combinatorial tuning of both promoters and RBSs has emerged as a powerful strategy for achieving user-defined operational specifications [23]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of promoter and RBS tuning methodologies, framed within the context of optimizing biosensor performance for applications in research and therapeutic development. We explore systematic approaches for fine-tuning these genetic parts, enabling synthetic biologists to precisely control the transfer function of biosensing systems and achieve predictable, robust performance across diverse biological contexts.

Theoretical Foundations of Genetic Regulation

The Interplay Between Transcriptional and Translational Control

Genetic circuit performance is governed by the complex interplay between transcriptional and translational regulation. Promoter strength determines the rate of transcription initiation, influencing the number of mRNA molecules available for translation. Subsequently, RBS efficiency governs the rate at which ribosomes initiate translation on these mRNA transcripts, directly impacting protein production levels [23]. This hierarchical regulation creates a multi-layered control system that enables sophisticated tuning of gene expression outputs. The inherent coupling between a synthetic circuit and the host's endogenous systems—through mechanisms such as resource competition and regulatory cross-talk—further complicates this relationship, giving rise to the well-documented chassis effect [23]. Strategic exploitation of this interplay allows researchers to access a broader performance space for genetic devices, moving beyond the limitations of traditional single-layer tuning approaches.

Quantitative Metrics for Biosensor Performance

Characterizing biosensor performance requires quantitative assessment of key operational parameters. The dynamic range represents the fold-difference between the fully induced ("on") and uninduced ("off") states, determining the sensor's ability to distinguish between signal presence and absence. The operational range defines the concentration window of the target analyte over which the biosensor responds effectively. Additional critical metrics include sensitivity (the minimal inducer concentration required to trigger a response), leakage (baseline expression in the absence of inducer), and response time (kinetics of signal activation) [23]. Systematic measurement of these parameters during the tuning process enables researchers to iteratively refine biosensor performance toward specific application requirements, whether for high-sensitivity diagnostic applications or broad-range environmental monitoring.

Experimental Methodologies for Systematic Tuning

Combinatorial Library Construction and Design

The construction of combinatorial libraries represents a foundational step in the genetic tuning workflow, enabling high-throughput exploration of the design space defined by promoter-RBS combinations.