Automating Discovery: How Robotic Platforms and AI Are Revolutionizing the Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle in Drug Development

This article explores the transformative integration of robotic platforms and artificial intelligence in automating the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for biomedical research and drug development.

Automating Discovery: How Robotic Platforms and AI Are Revolutionizing the Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle in Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of robotic platforms and artificial intelligence in automating the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for biomedical research and drug development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination of the foundational principles, methodological applications, and optimization strategies that are reshaping laboratory workflows. The content covers the urgent industry need for these technologies in overcoming low clinical success rates, details the specific robotic and AI tools enabling high-throughput experimentation, and offers a comparative analysis of their validation and economic impact. By synthesizing current trends and real-world applications, this guide serves as a strategic resource for labs aiming to enhance efficiency, accelerate discovery, and improve the success rates of new therapeutic candidates.

The Urgent Drive for Automation: Reversing Stagnant Success Rates in Drug Development

The biopharmaceutical industry is experiencing a significant productivity paradox: despite unprecedented levels of research activity and investment, clinical success rates are declining while costs escalate. With over 23,000 drug candidates in development and more than $300 billion spent annually on R&D, the industry faces immense pressure as R&D margins are projected to decline from 29% to 21% of total revenue by 2030 [1].

Table 1: Key Indicators of the R&D Productivity Challenge

| Metric | Current Status | Trend | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 Success Rate | 6.7% (2024) | Down from 10% a decade ago | Higher attrition in early development [1] |

| R&D Spending | >$300 billion annually | Increasing | Record investment levels [1] |

| R&D Margin | 29% of revenue | Projected to fall to 21% by 2030 | Decreasing efficiency [1] |

| Internal Rate of Return | 4.1% | Below cost of capital | Unsustainable investment model [1] |

| Revenue at Risk | $350 billion (2025-2029) | Patent cliff | Pressure on innovation funding [1] |

Compounding these challenges, clinical trial complexity and costs continue to rise due to factors including uncertain regulatory environments, geopolitical conflicts, and increased data intensity [2]. This application note details how automated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) platforms can address this productivity paradox through integrated artificial intelligence and robotics.

Experimental Protocols: Automated DBTL Platform Implementation

Platform Architecture and Workflow Integration

We describe a generalized platform for autonomous enzyme engineering that exemplifies the DBTL cycle application. The platform integrates machine learning, large language models, and biofoundry automation to eliminate human intervention bottlenecks while improving outcomes [3].

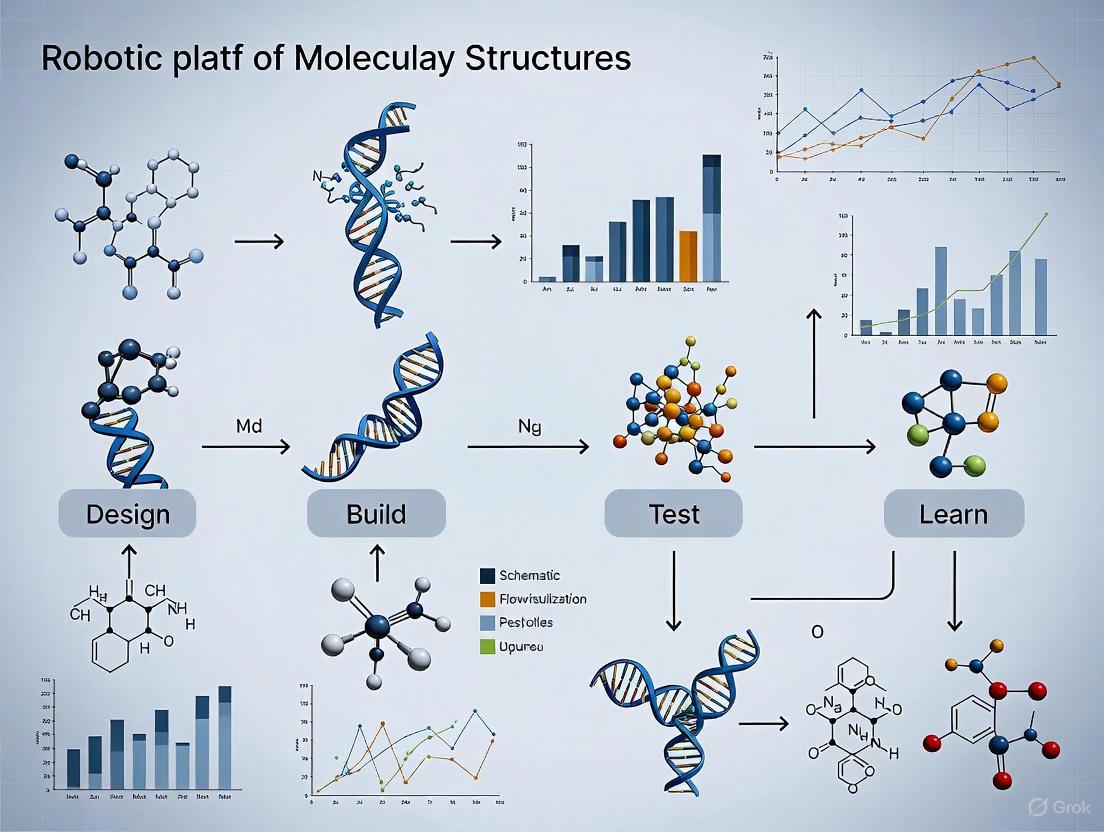

Diagram 1: Automated DBTL Cycle - Core iterative process for autonomous enzyme engineering.

Detailed Protocol: Automated Protein Engineering Workflow

Module 1: AI-Driven Protein Variant Design

- Input Requirements: Wild-type protein sequence and quantifiable fitness function [3]

- Design Method: Combine ESM-2 protein large language model with EVmutation epistasis model [3]

- Library Specifications: Generate 180 initial variants targeting diverse mutation spaces

- Success Metrics: 55-60% of variants performing above wild-type baseline [3]

Module 2: Automated Construction Pipeline

- Method: HiFi-assembly based mutagenesis eliminating intermediate sequencing verification [3]

- Accuracy: ~95% correct targeted mutations confirmed via random sequencing [3]

- Automation: Seven integrated modules programmed on iBioFAB platform

- Key Steps:

- Mutagenesis PCR preparation

- DpnI digestion

- 96-well microbial transformations

- Automated colony picking

- Plasmid purification

- Protein expression

- Functional enzyme assays [3]

Table 2: Automated DBTL Platform Performance Metrics

| Performance Indicator | AtHMT Engineering | YmPhytase Engineering | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Improvement | 16-fold (ethyltransferase) | 26-fold (neutral pH) | 4 weeks [3] |

| Substrate Preference | 90-fold improvement | N/A | 4 weeks [3] |

| Variants Constructed | <500 | <500 | 4 rounds [3] |

| Library Efficiency | 59.6% above wild-type | 55% above wild-type | Initial round [3] |

Diagram 2: Automated Experimental Workflow - Integrated modules for continuous protein engineering.

Protocol Validation: Case Studies in Enzyme Engineering

Case Study 1: Arabidopsis thaliana Halide Methyltransferase (AtHMT)

- Engineering Goal: Improve ethyltransferase activity and substrate preference [3]

- Fitness Function: Preference for ethyl iodide over methyl iodide

- Results: 90-fold improvement in substrate preference, 16-fold improvement in ethyltransferase activity [3]

- Screening Throughput: <500 variants constructed and characterized over 4 rounds [3]

Case Study 2: Yersinia mollaretii Phytase (YmPhytase)

- Engineering Goal: Enhance activity at neutral pH for animal feed applications [3]

- Fitness Function: Activity at neutral pH versus acidic optimum

- Results: 26-fold improvement in activity at neutral pH [3]

- Industrial Application: Improved gastrointestinal tract functionality [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Automated DBTL Platforms

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HiFi Assembly Mix | DNA assembly with high fidelity | Enables mutagenesis without intermediate sequencing [3] |

| ESM-2 Protein LLM | Variant fitness prediction | Unsupervised model trained on global protein sequences [3] |

| EVmutation Model | Epistasis analysis | Focuses on local homologs of target protein [3] |

| Low-N Machine Learning Model | Fitness prediction from sparse data | Trained on each cycle's assay data for subsequent iterations [3] |

| Automated Liquid Handling | High-throughput reagent distribution | Integrated with central robotic arm scheduling [3] |

| 96-well Microbial Culture Plates | Parallel protein expression | Compatible with automated colony picking [3] |

| Functional Assay Reagents | High-throughput activity screening | Quantifiable measurements compatible with automation [3] |

Discussion: Addressing the Productivity Paradox

The automated DBTL platform demonstrates a viable path to addressing the R&D productivity crisis. By completing four engineering rounds in four weeks with fewer than 500 variants per enzyme, the platform achieves order-of-magnitude improvements while significantly reducing resource requirements [3]. This approach directly counteracts the trends of rising costs and declining success rates documented in clinical development [1].

The integration of AI and automation enables more efficient navigation of vast biological search spaces while reducing human-intensive laboratory work. This is particularly valuable in the context of rising trial costs driven by complexity, regulatory uncertainty, and geopolitical factors [2]. As the industry faces the largest patent cliff in history, with $350 billion of revenue at risk between 2025-2029 [1], such platforms offer a strategic approach to maintaining innovation capacity despite margin pressures.

Future developments should focus on expanding these platforms to more complex biological systems, including mammalian cell engineering and clinical trial optimization, where the productivity challenges are most acute. The generalized nature of the described platform provides a framework for such extensions, potentially transforming R&D productivity across the biopharmaceutical industry.

The development of new therapeutic compounds often overshadows a critical and frequently underestimated challenge: the formulation bottleneck. This pivotal stage in the drug development pipeline represents a significant failure point where promising active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) stumble due to inadequate delivery systems. Effective drug delivery is paramount for ensuring optimal bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy, and patient compliance. Within modern biopharmaceutical research, the integration of robotic platforms and automated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles is emerging as a transformative approach to systematically address these formulation challenges. These automated systems enable rapid, data-driven optimization of delivery parameters, accelerating the development of robust formulations for increasingly complex modalities, including biologics, cell therapies, and nucleic acids [4] [5]. This Application Note provides a detailed framework, complete with quantitative data and standardized protocols, for leveraging automation to overcome the critical drug delivery bottleneck.

Quantitative Analysis of the Formulation Landscape

The growing importance of advanced drug delivery systems is reflected in market data and pipeline valuations. The following tables summarize key quantitative insights into the current landscape and the specific challenges posed by different drug modalities.

Table 1: Global Market Analysis for New Drug Delivery Systems (2025-2029)

| Metric | Value | Source/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2025) | USD 59.4 Billion (Projected) | Technavio, 2025 [6] |

| Forecast Period CAGR | 4.6% | Technavio, 2025 [6] |

| North America Market Share | 36% (Largest Share) | Technavio, 2025 [6] |

| Oncology Segment Value (2023) | USD 74.70 Billion | Technavio, 2025 [6] |

Table 2: New Modalities in the Pharma Pipeline (2025 Analysis)

| Drug Modality | Pipeline Value & Growth Trends | Key Formulation & Delivery Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies (mAbs, ADCs, BsAbs) | \$197B total pipeline value; Robust growth (e.g., ADCs up 40% YoY) [4] | High viscosity, volume for subcutaneous delivery; stability [4] [7] |

| Proteins & Peptides (e.g., GLP-1s) | 18% revenue growth driven by GLP-1 agonists [4] | High concentration formulations; device compatibility [4] |

| Cell Therapies (CAR-T, TCR-T) | Rapid pipeline growth, but high costs and mixed results in solid tumors [4] | Complex logistics (cold chain); in vivo manufacturing hurdles [4] |

| Gene Therapies | Stagnating growth; safety issues and commercial hurdles [4] | Vector efficiency; targeted delivery; immunogenicity [4] |

| Nucleic Acids (RNAi, ASO) | Rapid growth (e.g., RNAi pipeline value up 27% YoY) [4] | Targeted tissue delivery; endosomal escape; stability [4] |

Automated DBTL Protocols for Formulation Optimization

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, when implemented on a robotic platform, creates a closed-loop, autonomous system for overcoming formulation bottlenecks. The following protocols detail the experimental workflow for optimizing a critical formulation parameter: the induction profile for a recombinant protein-based API.

Protocol: Automated Optimization of Induction Parameters for Recombinant API Expression

1. Objective: To autonomously determine the optimal inducer concentration and feed rate that maximizes the yield of a model recombinant API (e.g., Green Fluorescent Protein, GFP) in an E. coli system using a robotic DBTL platform.

2. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential Materials for Automated Induction Optimization

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| E. coli Expression Strain | Recombinant host containing plasmid with API gene under inducible promoter. |

| Lysogeny Broth (LB) Media | Standard growth medium for bacterial cultivation. |

| Chemical Inducer (e.g., IPTG) | Triggers transcription of the target API gene. |

| Carbon Source Feed (e.g., Glucose) | Fed-batch substrate to maintain cell viability and productivity. |

| Robotic Bioprocessing Platform | Integrated system for liquid handling, incubation, and monitoring [5]. |

| Microplate Reader (on-platform) | Measures optical density (OD600) and fluorescence (GFP) in real-time. |

3. Methodology:

3.1. Design Phase: The software framework defines the experimental search space, typically a range of inducer concentrations (e.g., 0.1 - 1.0 mM IPTG) and feed rates (e.g., 0.5 - 5.0 mL/h). An optimization algorithm (e.g., Bayesian Optimization) is initialized to balance exploration of the parameter space and exploitation of known high-yield regions [5].

3.2. Build & Test Phase:

- The robotic platform automatically prepares a set of culture conditions in a deep-well microplate according to the parameters selected by the algorithm.

- The plate is transferred to an on-platform incubator-shaker, maintaining optimal temperature and agitation.

- The platform executes periodic sampling, using integrated liquid handlers to transfer aliquots to a reading plate.

- The microplate reader measures OD600 (biomass) and fluorescence/absorbance (API yield) for each well [5].

- All data is automatically written to a centralized database with full provenance.

3.3. Learn Phase:

- An optimizer software component analyzes the collected time-resolved data, calculating a fitness function (e.g., volumetric yield of API/GFP).

- The learning algorithm processes the results and selects the next set of inducer and feed rate parameters to test, effectively "closing the loop" [5].

- The cycle iterates autonomously until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., yield improvement < 2% over 3 cycles).

Protocol: Robotic Viscosity and Injection Force Profiling for Biologics

1. Objective: To characterize the injectability of high-concentration biologic formulations (e.g., mAbs) and identify parameters that minimize injection site pain using automated force analysis.

2. Methodology:

- The robotic system is equipped with a force transducer and a micro-syringe filled with the test formulation.

- The platform automates a series of injections through different gauges of subcutaneous injection needles into a simulated tissue matrix.

- It records the force versus displacement profile for each injection, calculating key metrics like glide force and maximum breakout force.

- This data is correlated with formulation viscosity and composition. The DBTL cycle can then be used to optimize excipients (e.g., surfactants, hyaluronidase) to reduce injection forces and mitigate injection site pain, a key barrier to patient adherence [7].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz using the specified color palette and contrast rules, illustrate the core logical relationships and experimental workflows described in this note.

Diagram 1: Automated DBTL Cycle for Formulation

Diagram 2: Drug Delivery Bottleneck Logic

What is the DBTL Cycle?

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a systematic, iterative framework central to synthetic biology and metabolic engineering for developing and optimizing biological systems [8]. Its power lies in the structured repetition of four key phases, enabling researchers to efficiently engineer organisms for specific functions, such as producing biofuels, pharmaceuticals, or other valuable compounds [8] [9].

The cycle begins with Design, where biological components are rationally selected and modelled. This is followed by Build, where the genetic designs are physically assembled and inserted into a host organism. Next, the Test phase involves analyzing the performance of the engineered system in functional assays. Finally, the Learn phase uses data analysis, often supported by machine learning, to extract insights that inform the design for the next cycle, creating a continuous loop of improvement [8] [9] [10].

Automation is a key enabler for the DBTL cycle, with robotic platforms—or biofoundries—dramatically increasing throughput, reliability, and reproducibility while reducing time and labor across all phases [11] [12].

The Four Phases of the DBTL Cycle in Detail

Design

The Design phase involves the rational selection and modelling of biological parts to create a genetic blueprint.

- Objective: To create a detailed genetic design that is predicted to achieve a desired function, such as optimizing metabolic flux toward a valuable product [9].

- Key Activities:

- Rational Design: Using prior knowledge to select DNA parts (e.g., promoters, coding sequences) [10].

- In Silico Modelling: Employing kinetic models to simulate pathway behavior and predict outcomes before physical assembly [9].

- Library Design: Planning combinatorial libraries of genetic variants to explore a design space, for example, by varying promoter strengths or ribosome binding sites (RBS) to tune enzyme expression levels [9] [10].

- Automation & Tools: Automated design software and data management systems help manage the complexity of designing large variant libraries [10] [11].

Build

The Build phase is the physical construction of the designed genetic elements and their introduction into a host organism.

- Objective: To accurately and efficiently assemble the designed genetic constructs and create microbial strain libraries [8] [11].

- Key Activities:

- DNA Assembly: Using modular cloning techniques (e.g., Golden Gate assembly) to piece together DNA fragments [8].

- Strain Engineering: Introducing the assembled constructs into a host chassis, such as E. coli or Corynebacterium glutamicum, via transformation [10] [11].

- Verification: Confirming the correct assembly of constructs using colony qPCR or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [8].

- Automation & Tools: Liquid handling robots execute high-throughput molecular cloning, drastically reducing manual labor and enabling the construction of large, diverse strain libraries [8] [11].

Test

The Test phase involves culturing the built strains and assaying their performance to generate quantitative data.

- Objective: To characterize the functional performance of engineered strains under controlled conditions [11].

- Key Activities:

- High-Throughput Cultivation: Growing strain variants in automated microbioreactor systems (e.g., BioLector) that monitor biomass, pH, and dissolved oxygen [11].

- Product Assay: Sampling cultures and using analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, photometric assays) to measure key performance indicators like product titer, yield, and productivity (TYR) [11] [13].

- Functional Screening: Testing for specific properties, such as enzyme activity retained after thermal stress [13].

- Automation & Tools: Integrated robotic platforms handle everything from inoculating cryo-stocks to running analytical assays, enabling fully autonomous, consecutive cultivation experiments [11].

Learn

The Learn phase is the critical step where experimental data is analyzed to generate insights for the next DBTL cycle.

- Objective: To identify the relationships between genetic design and functional performance, thereby learning how to improve subsequent designs [9] [10].

- Key Activities:

- Data Integration: Consolidating data from the Test phase for analysis [11].

- Machine Learning (ML): Training ML models (e.g., Gaussian process regression, random forest) on the experimental data to predict the performance of new, untested designs [9] [13].

- Recommendation: Using optimization algorithms (e.g., Bayesian optimization) to propose a new set of promising strain designs for the next DBTL cycle [9] [13].

- Automation & Tools: Data management systems and ML pipelines automate the analysis and recommendation process, closing the loop for autonomous cycling [11] [13].

Workflow Visualization: The Automated DBTL Cycle

The following diagram illustrates how the DBTL cycle is implemented on an automated robotic platform, integrating the four phases into a seamless, iterative workflow.

Key Quantitative Data from DBTL Implementations

The effectiveness of the DBTL cycle is demonstrated by its application in various metabolic engineering projects. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from selected case studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics from DBTL Cycle Case Studies

| Target Product / Goal | Host Organism | Key Engineering Strategy | Reported Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Escherichia coli | RBS library engineering to optimize enzyme expression levels [10] | 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L, a 2.6-fold improvement over the state-of-the-art [10] | [10] |

| Enzyme Stabilizing Copolymers | In vitro with Glucose Oxidase, Lipase, HRP | Machine learning-guided design of protein-stabilizing random copolymers [13] | Identified copolymers providing significant Retained Enzyme Activity (REA) after thermal stress, outperforming a 504-copolymer systematic screen [13] | [13] |

| Autonomous Strain Characterization | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Integration of automated deep freezer, clean-in-place protocols [11] | Achieved highly reproducible main cultures with <2% relative deviation, enabling consecutive screening without human interaction [11] | [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Representative DBTL Workflow

This protocol outlines the key steps for an automated DBTL cycle to optimize a metabolic pathway for product formation, as applied in recent studies [10] [11].

Phase 1: Design of a Combinatorial DNA Library

- Objective: Create a library of genetic designs to explore variations in enzyme expression levels.

- Procedure:

- Define Target Genes: Identify the genes of the metabolic pathway to be optimized (e.g., hpaBC and ddc for dopamine production) [10].

- Select Modulation Strategy: Choose a method for tuning gene expression, such as designing a library of Ribosome Binding Sites (RBS) with varying Shine-Dalgarno sequences [10].

- In Silico Design: Use computational tools (e.g., UTR Designer) to generate a diverse set of RBS sequences. The design space can include up to five different enzyme expression levels per gene [9] [10].

- Plan Assembly: Design oligonucleotides for the synthesis and assembly of the variant library into an appropriate expression plasmid (e.g., pET or pJNTN system) [10].

Phase 2: Automated Build of Strain Variants

- Objective: Construct the plasmid library and transform it into the production host at high throughput.

- Materials:

- Procedure:

- DNA Assembly: Program the liquid handler to set up assembly reactions in a 96-well format, mixing the designed oligonucleotides and plasmid backbone with the necessary enzymes [13].

- Transformation: Transfer the assembly reactions to the cloning strain for propagation. Isolate and verify the plasmids.

- Create Working Cell Bank (WCB): Transform the validated plasmid library into the production host. Culture the strains in a deep-well plate and prepare cryo-stocks (e.g., in 20% glycerol) for long-term storage at -20°C to -80°C within an integrated automated freezer [11].

Phase 3: High-Throughput Test of Strain Performance

- Objective: Cultivate strain variants and measure product formation automatically.

- Materials:

- Procedure:

- Inoculate Precultures: The robotic platform thaws WCBs and uses them to inoculate preculture medium in dedicated wells of a microtiter plate (MTP). The precultures are grown to a target optical density [11].

- Start Main Cultures: The platform automatically inoculates the main cultures in the BioLector MTP from the precultures.

- Monitor Cultivation: Run the BioLector to continuously monitor biomass, pH, and dissolved oxygen throughout the batch cultivation.

- Sample and Assay: At a defined timepoint or trigger, the robot performs non-invasive sampling of the culture broth. It then conducts a photometric or other assay in a separate assay plate to determine the product titer [11] [13].

Phase 4: Learn and Recommend New Designs

- Objective: Analyze data to build a predictive model and select the best strains for the next cycle.

- Procedure:

- Data Consolidation: Compile all performance data (e.g., final product titer) with the corresponding genetic design (e.g., RBS sequence) into a single dataset.

- Train Machine Learning Model: Use the compiled dataset to train a supervised learning model, such as Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) or Random Forest, to predict strain performance from genetic features [9] [13].

- Propose New Designs: Apply an optimization algorithm (e.g., Bayesian Optimization) to the trained model. The algorithm will propose a new batch of genetic designs that are predicted to have high performance, balancing exploration of new regions of the design space with exploitation of known promising areas [9] [13].

- Iterate: Return to Phase 1, using the new recommendations to initiate the next DBTL cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

A successful automated DBTL pipeline relies on a suite of integrated reagents, tools, and equipment.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Platforms for Automated DBTL

| Item | Function / Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handling Robot | Automates pipetting steps in DNA assembly, transformation, and assay setup. | Hamilton MLSTARlet [13]; Capable of handling 96- and 384-well plates. |

| Automated Deep Freezer | Provides on-demand, autonomous access to cryo-preserved Working Cell Banks. | LiCONiC; Maintains -20°C to -80°C; Integrated via mobile cart [11]. |

| Microbioreactor System | Enables parallel, monitored cultivation of hundreds of strain variants. | BioLector Pro; Monitors biomass, DO, pH in microtiter plates [11]. |

| RBS Library | Fine-tunes translation initiation rate and relative gene expression in synthetic pathways. | Library of Shine-Dalgarno sequence variants; Designed with UTR Designer [10]. |

| Expression Plasmid System | Vector for hosting and expressing the synthetic genetic construct in the host organism. | pET or pJNTN plasmid system; Compatible with inducible promoters (e.g., IPTG-inducible) [10]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System | Crude cell lysate for rapid in vitro testing of enzyme expression and pathway function. | Bypasses whole-cell constraints; used for preliminary, knowledge-driven design [10]. |

The contemporary laboratory is undergoing a profound transformation, evolving from a space characterized by manual processes into an intricate, interconnected data factory [14]. This shift is orchestrated through the seamless integration of three foundational technologies: advanced robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and sophisticated data analytics. Together, they form an operational triad that enables unprecedented levels of efficiency, reproducibility, and discovery. The core framework uniting these elements is the automated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, which applies an engineering approach to biological discovery and optimization [15] [16]. In this paradigm, robotics acts as the physical engine for execution, AI serves as the intelligent controller for design and analysis, and data analytics provides the essential insights that fuel iterative learning, creating a continuous loop of innovation.

Core Principles of the Automated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle

The automated DBTL cycle is a structured, iterative framework for the rapid development and optimization of biological systems, such as microbial strains for chemical production [16]. Its power lies in the automation and data-driven feedback connecting each phase.

- Design: In this initial phase, in silico tools are used to design genetic constructs or experimental plans. For metabolic engineering, this involves selecting enzymes and designing DNA parts with optimized regulatory elements (e.g., promoters, ribosome binding sites) using specialized software [16]. Designs can explore vast combinatorial libraries, which are then statistically reduced to a tractable number of constructs for testing.

- Build: This phase involves the physical construction of the designed genetic variants. Automated platforms, such as robotic liquid handlers, perform DNA assembly reactions (e.g., ligase cycling reaction) to build plasmids, which are then transformed into a microbial chassis. The process is supported by automated worklists and sample tracking [16].

- Test: The constructed strains are cultured in automated, high-throughput systems like 96-deepwell plate bioreactors. Target chemicals and intermediates are quantitatively screened using analytical techniques like UPLC-MS/MS. Data extraction and processing are automated with custom scripts [16].

- Learn: Data from the Test phase is analyzed using statistical methods and machine learning to identify the relationships between design parameters (e.g., promoter strength, gene order) and production titers. The insights gained directly inform the redesign of constructs in the next DBTL cycle, progressively optimizing the system [16].

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of an Automated DBTL Pipeline for Microbial Production

| DBTL Cycle | Target Product | Key Design Factors Explored | Initial Titer (mg L⁻¹) | Optimized Titer (mg L⁻¹) | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 [16] | (2S)-Pinocembrin | Vector copy number, promoter strength, gene order | 0.14 | - | - |

| Cycle 2 [16] | (2S)-Pinocembrin | Refined promoter placement and gene order | - | 88 | ~500 |

Detailed Protocol: Implementing an Automated DBTL Cycle for Microbial Metabolic Engineering

This protocol details the application of an automated DBTL pipeline to enhance the microbial production of fine chemicals, using the flavonoid (2S)-pinocembrin in Escherichia coli as a model system [16].

Application Note Objective

To establish a compound-agnostic, automated DBTL pipeline for the rapid discovery and optimization of biosynthetic pathways in a microbial chassis, achieving a 500-fold increase in (2S)-pinocembrin production titers over two iterative cycles [16].

Experimental Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Automated DBTL Protocol

| Item Name | Function / Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RetroPath [16] | In silico pathway selection tool | Identifies potential enzymatic pathways for the target compound. |

| Selenzyme [16] | Automated enzyme selection software | Selects specific enzyme sequences for the designed pathway. |

| PartsGenie [16] | DNA part design software | Designs reusable DNA parts with optimized RBS and codon-optimized coding regions. |

| Ligase Cycling Reaction (LCR) [16] | DNA assembly method | Used by the robotic platform to assemble multiple DNA parts into the final pathway construct. |

| E. coli DH5α [16] | Microbial production chassis | The host organism for the expression of the constructed flavonoid pathway. |

| UPLC-MS/MS [16] | Analytical screening platform | Provides quantitative, high-resolution data for the target product and key intermediates. |

Equipment and Software Configuration

- Robotics Platforms: Automated liquid handlers for DNA assembly and colony picking. A 96-deepwell plate system for microbial cultivation [16].

- Data Management: A centralized repository (e.g., JBEI-ICE) for storing DNA part designs, plasmid assemblies, and sample tracking with unique identifiers [16].

- Analytical Instrumentation: Ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) for high-throughput metabolite screening [16].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Phase 1: Design

- Pathway Selection: For the target compound (e.g., (2S)-pinocembrin), use RetroPath to identify a biosynthetic pathway from a core precursor (e.g., L-phenylalanine) [16].

- Enzyme Selection: Input the identified enzymatic reactions into Selenzyme to select specific enzyme coding sequences from source organisms [16].

- Genetic Design: Use PartsGenie to design the DNA parts, including optimization of ribosome-binding sites (RBS) and codon usage for the host organism [16].

- Library Design & Reduction: Combine genes and regulatory parts (promoters of varying strength) into a large combinatorial library. Apply Design of Experiments (DoE) to reduce the library to a statistically representative subset for testing [16].

Phase 2: Build

- DNA Synthesis: Source the designed coding sequences via commercial DNA synthesis [16].

- Automated Assembly Preparation: Use custom software to generate assembly recipes and robotics worklists for the Ligase Cycling Reaction (LCR) [16].

- Robotic Assembly: Execute the LCR assembly on a robotic platform [16].

- Transformation & QC: Transform the assembled constructs into the production chassis (e.g., E. coli). Quality-control candidate clones through automated plasmid purification, restriction digest, and sequence verification [16].

Phase 3: Test

- High-Throughput Cultivation: Inoculate verified constructs into 96-deepwell plates for automated growth and induction under controlled conditions [16].

- Metabolite Extraction: Automatically extract metabolites from the cultures.

- Quantitative Screening: Analyze the extracts using UPLC-MS/MS to quantify the titers of the target product (e.g., (2S)-pinocembrin) and key pathway intermediates (e.g., cinnamic acid) [16].

- Data Processing: Use custom R scripts for automated data extraction and processing [16].

Phase 4: Learn

- Statistical Analysis: Apply statistical analysis (e.g., analysis of variance) to the production data to identify the main design factors (e.g., vector copy number, promoter strength) that significantly influence product titer [16].

- Machine Learning: Use the results to train models that predict the performance of new design variants.

- Redesign: Use these insights to define the parameters for the next DBTL cycle, focusing on the most impactful factors to achieve further optimization [16].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

In the (2S)-pinocembrin case study, the first DBTL cycle identified vector copy number as the strongest positive factor affecting production, followed by the promoter strength upstream of the chalcone isomerase (CHI) gene [16]. The accumulation of the intermediate cinnamic acid indicated that phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity was not a bottleneck. These findings directly informed the second cycle's design, which focused on high-copy-number vectors and specific promoter placements, culminating in a final titer of 88 mg L⁻¹ [16].

The Integrated Technological Framework

The Role of Robotics and Automation

Robotics provides the physical engine for the automated lab, moving far beyond simple sample conveyance to execute complex, end-to-end workflows [14].

- Robotic Arms and Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMRs): Highly dexterous robotic arms mimic human manipulation skills for tasks like micro-pipetting and plating, while AMRs handle logistics, transporting materials between stations to ensure 24/7 operational continuity [14].

- Humanoid Robots: An emerging trend involves the use of affordable, general-purpose humanoid robots that can perform tasks in environments designed for humans, such as organizing equipment or interacting with touchscreens [14].

The Centrality of Data and AI

In the laboratory of the future, data is the primary asset, and every process is designed around its generation, capture, and analysis [14].

- FAIR Data and Interoperability: A major challenge is the fragmentation of data across disparate systems. The solution involves creating integrated data repositories where instruments automatically feed standardized, metadata-rich data, often facilitated by robust Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) [14] [17].

- AI and Machine Learning: AI algorithms manage experimental design, identify subtle trends, predict optimal conditions, and flag anomalies. They are crucial for analyzing the massive datasets generated in the "Learn" phase of the DBTL cycle [14] [16].

- Edge AI for Operational Resilience: To overcome the latency and internet dependence of cloud computing, leading labs are deploying Edge AI—high-performance computing resources on-premises. This enables real-time feedback to robotic systems, enhances data security, and ensures core functions continue during network outages [14].

Standardization and Open-Source Tools

The full potential of the automated lab is realized through standardization and collaboration. The development of open-source tools for tasks such as the automated standardization of laboratory units in electronic records is key to ensuring data interoperability and reducing analytic bias in large-scale datasets [18]. Furthermore, the community is moving towards an open, platform-based approach, such as a laboratory operating system that orchestrates the entire lab ecosystem through partnership and shared standards [17].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Automated DBTL Cycle for Metabolic Engineering.

Diagram 2: Hybrid AI & Data Infrastructure for the Automated Lab.

Building the Self-Driving Laboratory: A Practical Guide to Integrating Robotic Platforms and AI

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a core engineering framework in synthetic biology, enabling the systematic development and optimization of microbial strains for the production of fine chemicals and therapeutics. The manual execution of this cycle is often slow and labor-intensive, constraining the exploration of complex biological design spaces. Biofoundries address this bottleneck by integrating computer-aided design, synthetic biology tools, and robotic automation to create accelerated, automated DBTL pipelines [19] [16]. These facilities are structured research and development systems where biological design, validated construction, functional assessment, and mathematical modeling are performed following the DBTL engineering cycle [20]. The full automation of DBTL cycles, central to synthetic biology, is becoming a cornerstone for next-generation biomanufacturing and a sustainable bioeconomy [10].

Automating the DBTL cycle brings transformative advantages, including enhanced reproducibility, dramatically increased throughput, and the generation of high-quality, machine-learnable data for subsequent design iterations [15]. This article details the architecture of an automated DBTL workflow, from computational design to physical strain testing, providing application notes and detailed protocols tailored for research environments utilizing robotic platforms.

To manage the complexity of automated biological experimentation, a standardized abstraction hierarchy is essential for interoperability and clear communication between researchers and automated systems. This hierarchy organizes biofoundry activities into four distinct levels, effectively streamlining the DBTL cycle [20].

- Level 0: Project - This is the highest level, representing the overall goal or user request, such as "Develop a high-titer dopamine production strain in E. coli" [20] [10].

- Level 1: Service/Capability - This level defines the specific, modular services required to complete the project. Examples include "Modular DNA Assembly" or "AI-driven Protein Engineering" [20].

- Level 2: Workflow - Each service is broken down into sequential, DBTL-stage-specific workflows. These are abstracted, reusable modules such as "DNA Oligomer Assembly (Build)" or "High-Throughput Screening (Test)" [20].

- Level 3: Unit Operation - This is the lowest level, comprising the individual experimental or computational tasks executed by hardware or software. Examples include "Liquid Transfer" by a liquid-handling robot or "Protein Structure Generation" by RFdiffusion software [20].

This framework allows biologists to operate at higher abstraction levels (Project, Service) without needing detailed knowledge of the hardware-specific unit operations, while engineers can focus on robust execution at the lower levels [20].

Phase 1: Design – In Silico Pathway and Part Selection

The automated DBTL cycle begins with the Design phase, where computational tools are used to select and model the biological system to be constructed.

Application Note: Automated Enzyme Selection and Pathway Design

For any target compound, in silico tools enable the automated selection of candidate enzymes and pathway designs. The RetroPath tool can be used for automated enzyme selection, while Selenzyme is available for enzyme selection [16]. For a target like (2S)-pinocembrin, these tools can automatically select a pathway comprising enzymes such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL), chalcone synthase (CHS), and chalcone isomerase (CHI) [16]. Following enzyme selection, the PartsGenie software facilitates the design of reusable DNA parts, simultaneously optimizing bespoke ribosome-binding sites (RBS) and codon-optimizing enzyme coding regions [16].

Protocol: Designing a Combinatorial Library with Design of Experiments (DoE)

Objective: To create a manageable, representative library of genetic constructs for experimental testing that efficiently explores a large design space.

- Define Variables: Identify key genetic variables to test (e.g., promoter strengths, RBS sequences, gene order in an operon, plasmid copy number) [16].

- Generate Full Combinatorial Library: In silico, generate all possible combinations of the variables. For example, varying four genes' order (24 permutations), promoter strengths (3 levels), and vector backbone (4 types) can generate 2,592 possible configurations [16].

- Apply DoE Reduction: Use statistical methods like orthogonal arrays combined with a Latin square to reduce the library to a tractable number of representative constructs. This can achieve a high compression ratio (e.g., 162:1, from 2592 to 16 constructs) [16].

- Generate Assembly Instructions: Use software (e.g., PlasmidGenie) to automatically generate assembly recipes and robotics worklists for the Build phase. All designs should be deposited in a centralized repository like JBEI-ICE for sample tracking [16].

Phase 2: Build – Automated Genetic Construction

The Build phase translates digital designs into physical DNA constructs and engineered microbial strains. Automation here is critical for achieving high throughput and reproducibility.

Application Note: High-Throughput Yeast Strain Construction

A modular, automated protocol for the high-throughput transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on a Hamilton Microlab VANTAGE platform can achieve a throughput of ~2,000 transformations per week, a 10-fold increase over manual operations [19]. The workflow was programmed using Hamilton VENUS software and divided into discrete steps: "Transformation set up and heat shock," "Washing," and "Plating" [19]. A key feature is the integration of off-deck hardware (plate sealer, peeler, and thermal cycler) via the central robotic arm, enabling fully hands-free operation during the critical heat-shock step [19]. This pipeline is compatible with downstream automation, such as colony picking using a QPix 460 system [19].

Protocol: Automated Yeast Transformation in 96-Well Format

Objective: To build a library of engineered yeast strains via automated, high-throughput transformation.

Table 1: Key Reagent Solutions for Automated Yeast Transformation

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Competent S. cerevisiae Cells | Engineered host strain prepared for transformation. |

| Plasmid DNA Library | Contains genes for pathway optimization or target protein expression. |

| Lithium Acetate (LiOAc) | Component of transformation mix, permeabilizes the cell wall. |

| Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) | Blocks DNA-binding sites on cell surfaces to reduce non-specific plasmid binding. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Promotes plasmid DNA uptake by the competent cells. |

| Selective Agar Plates | Solid medium containing auxotrophic or antibiotic selection for transformed cells. |

- Deck Setup: Load the robotic deck with labware containing competent yeast cells, plasmid DNA library, and reagents (LiOAc, ssDNA, PEG) according to a predefined deck layout [19].

- Transformation Mix Setup: The robot pipettes the transformation mix (LiOAc/ssDNA/PEG) and plasmid DNA into a 96-well plate containing the competent cells. Critical: Optimize liquid classes for viscous reagents like PEG by adjusting aspiration/dispense speeds and air gaps to ensure volume accuracy [19].

- Heat Shock: The robotic arm moves the sample plate to an off-deck thermal cycler for a programmed heat-shock incubation (e.g., 42°C). The plate is sealed and peeled automatically during this process [19].

- Washing and Plating: Post heat-shock, the robot performs washing steps and finally plates the transformation mixture onto selective agar plates [19].

- Colony Picking: After incubation, transformed colonies are picked using an automated colony picker (e.g., QPix 460) for inoculation into culture plates for the Test phase [19].

Phase 3: Test – High-Throughput Screening and Analytics

The Test phase involves cultivating the engineered strains and quantifying their performance, such as the production of a target molecule.

Application Note: Screening for Verazine Production

An automated pipeline was used to screen a library of 32 genes overexpressed in a verazine-producing S. cerevisiae strain. The library included genes from native sterol biosynthesis, heterologous verazine pathways, and those related to sterol transport and storage [19]. Each engineered strain was cultured in a high-throughput 96-deep-well plate format with six biological replicates. A rapid, automated chemical extraction method based on Zymolyase-mediated cell lysis and organic solvent extraction was developed, followed by analysis via a fast LC-MS method that reduced the analytical runtime from 50 to 19 minutes [19]. This enabled efficient quantification of verazine titers across the ~200-sample library, identifying several genes (e.g., erg26, dga1, cyp94n2) that enhanced production by 2- to 5-fold [19].

Protocol: High-Throughput Cultivation and Metabolite Analysis

Objective: To test the performance of a strain library by measuring the titer of a target metabolite.

- Inoculation and Cultivation: Using a liquid handler, inoculate sterile culture medium in 96-deep-well plates from the picked colonies. Incubate plates in a controlled, high-capacity shaking incubator to support cell growth and product formation [19] [16].

- Automated Metabolite Extraction:

- Cell Lysis: Transfer an aliquot of culture to a new plate and add a lysis buffer (e.g., containing Zymolyase for yeast) [19]. Incubate to degrade cell walls.

- Solvent Extraction: Add an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate) to extract the target metabolite from the lysate. The plate can be sealed and mixed thoroughly by the robot [19].

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge the plate to achieve phase separation.

- LC-MS Analysis:

- The robotic system prepares the injection plate, possibly including a dilution or filtration step.

- A liquid handler interfaces with the LC-MS system, injecting samples for analysis.

- Use a fast, optimized LC-MS method (e.g., 19-minute runtime) for rapid separation and quantification of the target compound [19].

- Data Extraction: Use custom-developed, open-source R scripts for automated data extraction and processing of the raw LC-MS results to calculate titers for each strain [16].

Phase 4: Learn – Data Analysis and Model Refinement

The Learn phase closes the DBTL loop by transforming experimental data into actionable knowledge for the next design iteration.

Application Note: Statistical and Machine Learning Analysis

After testing a reduced library of 16 pathway constructs for pinocembrin production in E. coli, statistical analysis of the titers identified the main factors influencing production [16]. Vector copy number was the strongest significant factor, followed by the promoter strength upstream of the CHI gene [16]. This knowledge-driven approach informs the constraints for the next DBTL cycle. More advanced machine learning (ML) techniques can be applied to navigate the design space more efficiently, identifying non-intuitive relationships between genetic parts and pathway performance [15] [21]. The application of a "knowledge-driven DBTL" cycle, which incorporates upstream in vitro testing in cell lysate systems to gain mechanistic insights before in vivo strain construction, has also been shown to efficiently guide RBS engineering for optimizing dopamine production [10].

Protocol: Statistical Analysis for Pathway Bottleneck Identification

Objective: To identify key genetic and regulatory factors limiting product yield from a screened library.

- Data Compilation: Compile production titers and metadata (e.g., promoter strength, RBS sequence, gene order) for all constructs in the tested library into a single data table.

- Statistical Modeling: Perform statistical analysis, such as Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), to determine the P-values associated with each design factor, quantifying its impact on the final titer [16].

- Identify Bottlenecks: Rank factors by their statistical significance. A highly significant factor (e.g., a specific promoter strength) with a positive effect indicates a potential bottleneck when sub-optimal.

- Define New Design Space: Use the results to refine the design space for the next cycle. For example, if a high-copy number plasmid was beneficial, constrain all future designs to use it. Focus combinatorial variation on the most influential factors [16].

Integrated Case Study: Optimizing Dopamine Production in E. coli

The application of a knowledge-driven DBTL cycle for dopamine production in E. coli demonstrates the power of an integrated, automated workflow [10]. The project aim (Level 0: Project) was to develop an efficient dopamine production strain.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Automated DBTL Implementation

| DBTL Metric | Manual / Low-Throughput Workflow | Automated / High-Throughput Workflow | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Transformation Throughput | ~200 transformations per week | ~2,000 transformations per week | [19] |

| Pinocembrin Production Titer (after 2 DBTL cycles) | N/A (Starting point) | 88 mg L⁻¹ (500-fold improvement) | [16] |

| Dopamine Production Titer | 27 mg L⁻¹ (State-of-the-art) | 69 mg L⁻¹ (2.6-fold improvement) | [10] |

| LC-MS Analysis Runtime | 50 minutes per sample | 19 minutes per sample | [19] |

- Design: The pathway from l-tyrosine to dopamine via l-DOPA was designed using enzymes HpaBC and Ddc [10].

- Build (In Vitro): The pathway was first tested in a cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) system to rapidly assess enzyme expression and activity without cellular constraints, generating initial knowledge [10].

- Build (In Vivo) & Test: The knowledge from the CFPS system was translated to an in vivo environment via high-throughput RBS engineering to fine-tune the relative expression of hpaBC and ddc. An automated platform was used to build and screen the RBS library [10].

- Learn: Analysis of the strain performance data identified the impact of GC content in the Shine-Dalgarno sequence on translation efficiency, leading to the development of a strain producing 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L of dopamine, a 2.6-fold improvement over the state of the art [10].

The 'Design' phase represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving from traditional, labor-intensive methods to automated, AI-driven workflows. By leveraging generative models, researchers can now rapidly design novel compounds with desired pharmacological properties, thereby compressing the early-stage discovery timeline from years to months [22]. This approach is particularly powerful when integrated into robotic platforms that automate the entire Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, creating a closed-loop system for iterative compound optimization [22]. AI models excel at navigating the vast complexity of chemical space, where the analysis of millions of variables and extensive datasets enables the identification of meaningful patterns that would be impossible for human researchers to discern efficiently [23]. This capability is transforming how pharmaceutical companies approach therapeutic development, with multiple AI-designed small-molecule drug candidates now reaching Phase I trials in a fraction of the typical 5-year timeline required for traditional discovery and preclinical work [22].

Key AI Approaches and Architectures

Large Property Models (LPMs)

Large Property Models represent a fundamental breakthrough in solving the inverse design problem—finding molecular structures that match a set of desired properties. Unlike traditional forward models that predict properties from structures, LPMs directly learn the conditional probability P(molecule|properties) by training on extensive chemical datasets with multiple property annotations [24]. The core hypothesis behind LPMs is that the property-to-structure mapping becomes unique when a sufficient number of properties are supplied during training, effectively teaching the model "general chemistry" before focusing on specific application-relevant properties [24]. These models demonstrate that including abundant chemical property data during training, even for off-target properties, significantly improves the model's ability to generate valid, synthetically feasible structures that match targeted property profiles [24].

Multimodal Biochemical Language Models

This advanced architecture combines protein language models (PLMs) with chemical language models (CLMs) to enable generative design of active compounds with desired potency directly from target protein sequences [25]. The model operates by first generating embeddings from protein sequences using a pre-trained PLM (e.g., ProtT5-XL-Uniref50), then conditions a transformer on both these protein embeddings and numerical potency values to generate corresponding compound structures in SMILES format [25]. This approach effectively learns mappings from combined protein sequence and compound potency value embeddings to active compounds, demonstrating proof-of-concept for generating structurally diverse candidate compounds with target-specific activity [25].

Generative Adversarial Networks and Variational Autoencoders

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) and variational autoencoders (VAEs) provide complementary strengths for molecular generation. The VGAN-DTI framework integrates both approaches: VAEs capture latent molecular representations and produce synthetically feasible molecules, while GANs introduce adversarial learning to enhance structural diversity and generate novel chemically valid molecules [26]. This synergy ensures precise interaction modeling while optimizing both feature extraction and molecular diversity, ultimately improving drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction accuracy when combined with multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) for interaction classification [26].

Performance Comparison of AI Drug Discovery Platforms

Table 1: Leading AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platforms and Their Performance Metrics

| Company/Platform | AI Approach | Key Therapeutic Areas | Reported Efficiency Gains | Clinical Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia | Generative AI + "Centaur Chemist" | Oncology, Immuno-oncology, Inflammation | 70% faster design cycles; 10x fewer synthesized compounds [22] | Multiple Phase I/II trials [22] |

| Insilico Medicine | Generative AI | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) | Target to Phase I in 18 months [22] | Phase I trials [22] |

| Recursion | Phenomics + AI | Multiple | Integrated platform post-Exscientia merger [22] | Multiple clinical programs [22] |

| BenevolentAI | Knowledge graphs | Multiple | Target identification and validation [22] | Clinical stages [22] |

| Schrödinger | Physics-based simulations + ML | Multiple | Accelerated lead optimization [22] | Clinical stages [22] |

Quantitative Performance of AI Generative Models

Table 2: Performance Metrics of AI Generative Models for Molecular Design

| Model Type | Key Performance Metrics | Dataset | Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Property Models (LPMs) | Reconstruction accuracy increases with number of properties; Enables inverse design [24] | 1.3M molecules from PubChem, 23 properties [24] | Transformers for property-to-molecular-graph task [24] |

| Biochemical Language Model | Generates compounds with desired potency from target sequences; Structurally diverse outputs [25] | 87,839 compounds from ChEMBL, 1575 activity classes [25] | ProtT5 PLM + conditional transformer [25] |

| VGAN-DTI | 96% accuracy, 95% precision, 94% recall, 94% F1 score for DTI prediction [26] | BindingDB | GAN + VAE + MLP integration [26] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing Large Property Models for Inverse Molecular Design

Purpose: To generate novel molecular structures with targeted properties using LPMs. Materials:

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

- Software: Python with deep learning frameworks (PyTorch/TensorFlow)

- Data: Curated dataset of molecular structures with multiple property annotations

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Curate a dataset of molecular structures with associated properties. The LPM implementation by Jin et al. utilized 1.3 million molecules from PubChem with 23 calculated properties including dipole moment, HOMO-LUMO gap, logP, and topological polar surface area [24].

- Model Architecture Selection: Implement a transformer architecture specialized for the property-to-molecular-graph task. The model should accept a vector of property values as input and generate molecular structures (as SMILES or graph representations) as output [24].

- Training Protocol: Train the model using a dataset with diverse molecular representations and property annotations. Monitor reconstruction accuracy as a function of the number of properties supplied during training [24].

- Sampling and Generation: Query the trained model with target property vectors to generate novel molecular structures. Validate generated structures for chemical validity and property matching using independent assessment methods [24].

- Iterative Refinement: Incorporate generated compounds into the DBTL cycle, using experimental results to refine the model through continuous learning.

Protocol: Target-Specific Compound Generation Using Biochemical Language Models

Purpose: To generate potent compounds for specific protein targets using sequence and potency information. Materials:

- Protein sequences in FASTA format

- Potency data (pKi values) for known actives

- Pre-trained protein language model (ProtT5-XL-Uniref50)

- Chemical language model component

Procedure:

- Data Curation: Collect high-confidence bioactivity data from sources like ChEMBL, ensuring direct interactions (assay confidence score 9) and consistent potency measurements (e.g., Ki values converted to pKi) [25].

- Protein Sequence Embedding: Generate embeddings for target protein sequences using the pre-trained ProtT5 PLM, which captures structural and functional information from ultra-large sequence datasets [25].

- Model Training: Train a conditional transformer to learn mappings from combined protein sequence embeddings and potency value embeddings to corresponding compound structures (SMILES strings) [25].

- Conditional Generation: Generate novel compounds by providing target sequence embeddings and desired potency values to the trained model.

- Validation: Evaluate generated compounds through docking studies, synthetic accessibility scoring, and assessment of structural diversity relative to known actives.

Protocol: Enhancing Drug-Target Interaction Prediction with VGAN-DTI

Purpose: To accurately predict drug-target interactions using a hybrid generative approach. Materials:

- Binding affinity data from BindingDB

- Molecular structures in SMILES format

- Target protein information

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Preprocess drug-target interaction data from BindingDB, representing molecular structures as fingerprint vectors [26].

- VAE Implementation: Configure the VAE component with an encoder network that maps molecular features to latent-space distributions (mean and log-variance), and a decoder network that reconstructs molecular structures from latent representations [26].

- GAN Implementation: Implement the GAN component with a generator that creates molecular structures from random latent vectors and a discriminator that distinguishes between real and generated molecules [26].

- MLP Integration: Train multilayer perceptrons on generated molecular features to predict binding affinities and classify drug-target interactions [26].

- Model Validation: Evaluate the complete VGAN-DTI framework using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score metrics, comparing against baseline methods [26].

Workflow Visualization

AI-Driven DBTL Cycle for Compound Design

Biochemical Language Model Architecture

Multimodal Biochemical Language Model

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Driven Compound Design

| Resource | Type | Function in AI-Driven Design | Example Sources/Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curated Bioactivity Data | Dataset | Training and validating biochemical language models | ChEMBL, BindingDB [25] [26] |

| Pre-trained Protein Language Models | Software | Generating protein sequence embeddings for target-specific design | ProtT5-XL-Uniref50 from ProtTrans [25] |

| Molecular Property Calculators | Software/Tool | Generating training data for Large Property Models | GFN2-xTB, RDKit [24] |

| Automated Synthesis Platforms | Hardware | Translating AI-designed compounds to physical samples for testing | Robotics-mediated automation systems [22] |

| High-Throughput Screening | Assay Platform | Generating experimental data for AI model refinement | Phenotypic screening platforms [22] |

| Chemical Structure Representations | Data Format | Encoding molecular structures for AI processing | SMILES, SELFIES, Molecular graphs [24] [25] |

Within the framework of an automated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for research, the "Build" phase is critical for translating digital designs into physical biological entities. This phase encompasses the high-throughput construction of genetic constructs and the preparation of experimental cultures. The integration of robotic systems has transformed this stage from a manual, low-throughput bottleneck into a rapid, reproducible, and automated process [16]. Automation in the Build phase directly enhances the overall efficiency of the entire DBTL cycle, enabling the rapid prototyping of thousands of microbial strains or chemical synthesis pathways for discovery and optimization [15] [16]. This document details the application of high-throughput robotic systems for the synthesis and assembly of genetic parts into functional pathways within microbial hosts, providing detailed protocols and key resources.

High-Throughput Robotic Platforms for Synthesis and Assembly

Robotic systems applied in the "Build" phase can be categorized into several architectures, each offering distinct advantages for specific laboratory workflows.

Table 1: Key Robotic Platform Architectures for the "Build" Phase

| Platform Architecture | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Station-Based Automation | Integrated, specialized workstations for specific tasks (e.g., liquid handling, PCR) [27]. | Automated pathway assembly using ligase cycling reaction (LCR), sample preparation for sequencing, culture transformation [16]. | Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer for organic synthesis [28]. |

| Mobile Manipulator Systems | A free-roaming mobile robot navigates a lab, transferring samples between standard instruments [27] [28]. | End-to-end execution of multi-step experiments that involve synthesis, analysis, and sample management across different stationary instruments [27]. | Platform with mobile robots transporting samples between synthesizer, UPLC–MS, and NMR [28]. |

| Collaborative Robots (Cobots) | Robotic arms designed to work safely alongside humans in a shared workspace [29] [30]. | Repetitive but delicate tasks such as sample preparation, liquid handling, and pick-and-place operations in dynamic research environments [30]. | Used for tasks requiring flexibility, such as the production of personalized medicines [30]. |

The core application of these platforms in synthetic biology is the automated assembly of genetic pathways. A landmark study demonstrated a fully automated DBTL pipeline for optimizing microbial production of fine chemicals [16]. The Build stage involved:

- Automated DNA Assembly: Using robotic platforms to perform ligase cycling reaction (LCR) for pathway assembly based on computationally designed worklists [16].

- Clone Verification: Automated plasmid purification, restriction digest, and analysis via capillary electrophoresis, followed by sequence verification [16].

This automated Build process successfully constructed a representative library of 16 pathway variants, enabling a 500-fold improvement in the production titer of the flavonoid (2S)-pinocembrin in E. coli through two iterative DBTL cycles [16].

For chemical synthesis, the "robochemist" concept leverages mobile manipulators and robotic arms to perform core laboratory skills like pouring and liquid handling, moving beyond traditional stationary automation [27]. These systems can execute synthetic protocols written in machine-readable languages (e.g., XDL) through automated path-planning algorithms [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Automated Pathway Assembly and Strain Construction

This protocol describes an automated workflow for building a combinatorial library of genetic pathway variants in a 96-well format, adapted from established automated DBTL pipelines [16].

Pre-Build Requirements: Design and DNA Synthesis

- Input from Design Phase: The process begins with a statistically reduced library of genetic designs from the "Design" phase. A custom software (e.g., PlasmidGenie) generates assembly recipes and robotics worklists [16].

- DNA Parts Preparation: Source DNA parts (e.g., promoters, genes, terminators) are either obtained commercially via synthesis or from repository libraries. Parts require preparation, typically via PCR, before robotic assembly [16].

Automated Build Procedure

Step 1: Robotic Reaction Setup

- Configure the Liquid Handler: Ensure the robotic liquid handling platform (e.g., equipped with a 96-channel head) is calibrated. Load labware: source plates containing DNA parts, a destination 96-well PCR plate for assemblies, and reagent reservoirs with nuclease-free water and LCR master mix.

- Transfer DNA Parts: Following the automated worklist, the robot transfers specified volumes of each DNA part (e.g., 1 µL of each plasmid or fragment at 10-20 ng/µL) into the corresponding wells of the destination PCR plate.

- Add Assembly Mix: The robot dispenses the LCR master mix (containing ligase, buffer, ATP) to each reaction well. The final reaction volume is 10 µL.

- Seal the Plate: Manually or robotically apply a thermal seal to the plate.

Step 2: Off-Deck Incubation and Transformation

- Perform Assembly Reaction: Transfer the sealed plate to a thermal cycler and run the LCR program (e.g., 5 minutes at 98°C, followed by 100 cycles of 10 seconds at 98°C and 1-4 minutes at 58°C) [16].

- Transform Host Cells: This step is currently performed off-deck. Aliquot competent E. coli cells (e.g., DH5α) into a 96-well assay plate. Transfer 1 µL of the completed LCR reaction into the cells, and perform a standard heat-shock transformation protocol.

- Plate for Colony Growth: Plate the transformation mixtures onto selective LB-agar plates, either manually or using an automated colony picker. Incubate overnight at 37°C.

Step 3: Automated Clone Verification

- Inoculate Cultures: Using a colony picker, inoculate single colonies into a 96-deepwell plate containing selective LB medium.

- Perform Automated Plasmid Prep: The robotic system executes a high-throughput plasmid purification protocol from the grown cultures.

- Analyze Constructs: The robot prepares analytical restriction digests of the purified plasmids. The digest products are then analyzed by an automated capillary electrophoresis system (e.g., Fragment Analyzer) to verify the correct assembly size.

- Sequence Verification: Plasmid samples identified with the correct restriction pattern are submitted for sequencing. The entire process, from cultured cells to sequence-verified constructs, is tracked using a laboratory information management system (LIMS) with unique sample IDs [16].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Genetic Assembly

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ligase Cycling Reaction (LCR) Master Mix | Enzymatically assembles multiple linear DNA fragments into a circular plasmid in a one-pot reaction [16]. | Preferred over traditional methods for its efficiency and suitability for automation. |

| Competent E. coli Cells | Host for transformation with assembled constructs to enable plasmid propagation and subsequent testing. | High-efficiency, chemically competent cells (e.g., DH5α) suitable for 96-well transformation. |

| Selective Growth Medium | Selects for transformed cells containing the correctly assembled plasmid with an antibiotic resistance marker. | LB broth or agar supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., Carbenicillin 100 µg/mL). |

| 96-Well Plates (PCR & Deepwell) | Standardized labware for housing reactions and cultures in an automated workflow. | PCR plates for assembly; 2 mL deepwell plates for culture growth and plasmid preparation. |

Workflow and System Architecture Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow of the automated Build phase and the architecture of a integrated robotic platform.

Automated Build Phase Workflow

Modular Robotic Platform Architecture

In modern synthetic biology and drug development, the 'Test' phase is critical for transforming designed genetic constructs into reliable, empirical data. Automated analytics, screening, and data acquisition technologies have revolutionized this phase, enabling robotic platforms to execute autonomous Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles [31] [15]. This automation addresses the traditional bottleneck of manual data collection and analysis, facilitating rapid optimization of biological systems. By integrating advanced analytical instruments, machine learning algorithms, and high-throughput screening capabilities, these systems can conduct continuous, self-directed experiments. This article details the practical application of these technologies through specific experimental protocols and the underlying infrastructure that supports autonomous discovery.

Core Components of an Automated Test Platform

The transformation of a static robotic platform into a dynamic, autonomous system relies on the integration of specialized hardware and software components. These elements work in concert to execute experiments, gather high-dimensional data, and make intelligent decisions for subsequent iterations.

Hardware Architecture

The physical platform is composed of interconnected workstations, each serving a distinct function within the automated workflow. A representative setup includes [31]:

- Liquid Handling Robots: Both 8-channel (for individualized well treatment) and 96-channel (for full-plate operations) liquid handlers (e.g., CyBio FeliX) manage all reagent additions and inoculations.

- Microtiter Plate (MTP) Incubator: A shake incubator (e.g., Cytomat) maintains optimal growth conditions (e.g., 37°C, 1,000 rpm) for parallel microbial cultivations.

- Multi-mode Plate Reader: An instrument (e.g., PheraSTAR FSX) performs optical density (OD600) measurements to monitor growth and fluorescence detection to quantify target protein (e.g., GFP) expression.

- Robotic Arm: A gripper-equipped arm coordinates the transfer of MTPs between different workstations, ensuring a seamless workflow.

- Storage and Logistics: Integrated racks and refrigerated units store plates, tips, and reagents, while a de-lidder automates plate preparation for measurements.

Software and Data Framework

The software framework is the "brain" of the operation, enabling autonomy. Its key components are [31]:

- Experiment Manager: Central software (e.g., CyBio Composer) that orchestrates the physical workflow, scheduling tasks and device operations.

- Data Importer: A software component that automatically retrieves raw measurement data from platform devices (like the plate reader) and writes it into a centralized database.

- Optimizer: This is the core learning module. It accesses the database, analyzes the results, and runs a learning algorithm to select the next set of experimental conditions, balancing exploration of new parameter spaces and exploitation of known promising areas.

Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Optimization of Protein Expression

The following protocol details a specific experiment demonstrating an autonomous test-learn cycle for optimizing inducer concentration in a bacterial system, as established by Spannenkrebs et al. [31] [5].

Objective

To autonomously determine the optimal inducer concentration (e.g., IPTG or lactose) for maximizing the production of a recombinant protein (e.g., Green Fluorescent Protein, GFP) in Escherichia coli over four consecutive iterations of the test-learn cycle.

Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Specification | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plate (MTP) | 96-well, flat-bottom | Vessel for parallel microbial cultivation and analysis. |

| Bacterial Strain | E. coli or Bacillus subtilis with inducible GFP construct | Model system for evaluating protein expression. |

| Growth Media | Lysogeny Broth (LB) or other defined media | Supports microbial growth and protein production. |

| Inducer Solution | IPTG (Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside) or Lactose | Triggers expression of the target protein from the inducible promoter. |

| Polysaccharide Feed | e.g., Starch or Glycogen | Source for controlled glucose release via enzyme addition. |

| Feed Enzyme | e.g., Amyloglucosidase | Hydrolyzes polysaccharide to control glucose release rate and growth. |

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

Day 1: Platform Preparation

- Reagent Setup: Aliquot sterile growth media, inducer stock solutions, and feed enzymes into designated refrigerated (4°C) positions on the robotic platform.

- Strain Inoculation: Manually pick a single colony of the expression strain to inoculate a pre-culture in a deep-well plate filled with media. Seal the plate and load it onto the platform's incubator.

Day 2: Autonomous Test-Learn Cycle Execution The following workflow runs autonomously for the duration of the experiment (e.g., 24-48 hours), repeating for multiple cycles.

Workflow Description:

- Dispense Media & Cells: The 96-channel liquid handler transfers a precise volume of fresh media from a reservoir to a new 96-well MTP. The 8-channel handler then inoculates each well with a standardized volume from the growing pre-culture.

- Apply Inducer/Feed Conditions: Based on the parameter set provided by the optimizer, the 8-channel liquid handler adds different concentrations of inducer (e.g., IPTG) and feed enzyme to the respective wells. The first iteration may use a pre-defined range or a random search.

- Incubate & Monitor: The robotic arm moves the MTP to the shake incubator. The plate remains there, with the system potentially scheduling brief interruptions for measurement.

- Measure OD600 & Fluorescence: The robotic arm retrieves the plate, transfers it to the plate reader, which measures the optical density (OD600) and fluorescence (ex/em for GFP) for every well. The plate is then returned to the incubator. This measurement is repeated at regular intervals (e.g., every 30-60 minutes) to generate time-resolved data.

- Data Importer: After the final time point, the raw measurement data is automatically extracted from the plate reader and structured into a database, including provenance (metadata linking data to experimental conditions).

- Optimizer: The learning algorithm (e.g., Bayesian Optimization, Random Forest) accesses the complete dataset. It fits a model that correlates the input parameters (inducer, feed) with the output (e.g., final GFP yield/OD). The model balances exploration (testing uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining known high-yield regions).

- Select Next Parameter Set: The optimizer selects the most informative set of conditions for the next iteration and writes them to the database.

- Cycle Control: The experiment manager checks if the predefined number of cycles (e.g., 4) is complete. If not, the cycle repeats from Step 2 using the new parameters. If complete, the platform halts and outputs the final results.