Automated Recommendation Algorithms in DBTL Cycles: Accelerating Synthetic Biology and Drug Development

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning-based Automated Recommendation Tools (ART) in the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for researchers and drug development professionals.

Automated Recommendation Algorithms in DBTL Cycles: Accelerating Synthetic Biology and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning-based Automated Recommendation Tools (ART) in the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational shift from manual to data-driven bioengineering, details methodological implementations like the ART tool and the emerging LDBT paradigm, addresses critical troubleshooting for real-world application, and provides validation through case studies in metabolic engineering and therapeutic production. The synthesis offers a roadmap for integrating these algorithms to drastically reduce development timelines and enhance predictive design in biomedical research.

From Manual Iteration to AI-Driven Design: The Foundation of Modern DBTL Cycles

Synthetic biology aims to reprogram organisms with desired functionalities through established engineering principles. A cornerstone of this discipline is the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, a systematic framework used to iteratively develop and optimize biological systems [1] [2]. This cyclical process allows researchers to engineer organisms to perform specific functions, such as producing biofuels, pharmaceuticals, or other valuable compounds [1]. The DBTL cycle provides a structured approach to tackle the complexity and unpredictability of biological systems, moving beyond ad-hoc engineering practices toward a more predictable and efficient methodology [3].

This article explores the core principles of the DBTL cycle, with a specific focus on the emerging role of machine learning and automated recommendation tools in accelerating biological design. We will provide practical troubleshooting guidance and contextualize these concepts within modern research on automated algorithms for DBTL cycles.

The Core DBTL Cycle: A Stage-by-Stage Breakdown

The DBTL cycle consists of four interconnected phases that form an iterative loop for biological engineering. The table below summarizes the key activities and outputs for each stage.

| Stage | Key Activities | Primary Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Rational design of biological parts and systems; pathway design; selection of genetic components [1] [2] | DNA construct designs; genetic circuit blueprints; experimental plans |

| Build | DNA assembly; molecular cloning; plasmid construction; genome editing; transformation into host cells [1] [4] [2] | Assembled genetic constructs; engineered microbial strains |

| Test | Functional assays; multi-omics profiling (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics); production measurement [1] [2] [3] | Performance data (titer, yield, rate); omics datasets; phenotypic characterization |

| Learn | Data analysis; statistical evaluation; machine learning; model building; hypothesis generation [2] [3] | New insights; refined designs; predictive models; recommendations for next cycle |

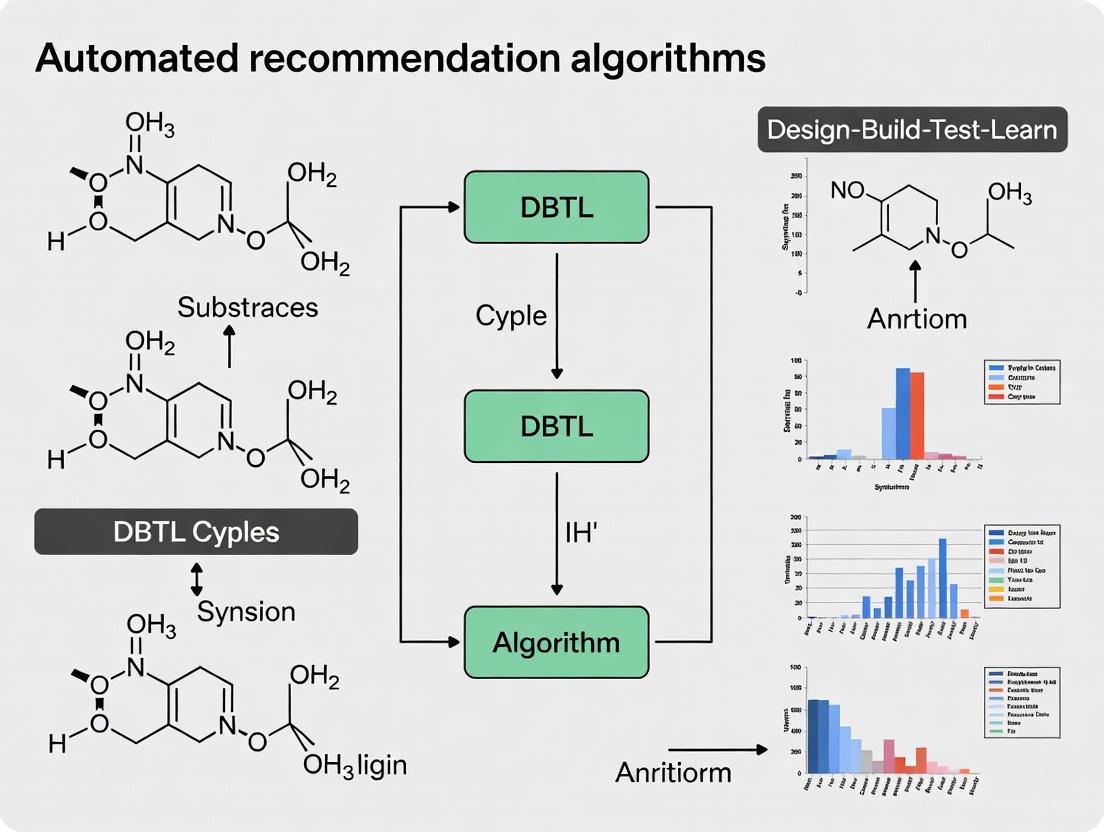

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow and key technologies involved in each phase of the DBTL cycle:

Machine Learning and Automated Recommendation Tools

The "Learn" phase has traditionally been the most significant bottleneck in the DBTL cycle [2] [3]. However, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful approach to distill complex biological information and generate predictive models from experimental data [2]. ML can process large datasets to identify non-obvious patterns and relationships between genetic designs and phenotypic outcomes, even without a complete mechanistic understanding of the biological system [3].

The Automated Recommendation Tool (ART)

The Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) represents a specialized ML application for synthetic biology that bridges the Learn and Design phases [3]. ART uses probabilistic modeling to recommend specific genetic designs likely to improve target metrics in the next DBTL cycle. Key capabilities include:

- Predictive Modeling: ART trains on available experimental data to build models that predict biological system behavior, providing full probability distributions rather than single-point estimates [3]

- Uncertainty Quantification: The tool quantifies prediction uncertainty, enabling researchers to balance exploration of new designs against exploitation of known productive regions [3]

- Multi-Objective Optimization: ART supports various engineering goals, including maximizing production, minimizing toxicity, or achieving specific target levels [3]

In practice, ART has demonstrated significant successes, such as improving tryptophan productivity in yeast by 106% from the base strain [3]. The following diagram illustrates how ML systems like ART integrate into the DBTL workflow:

Troubleshooting Guide: Common DBTL Challenges and Solutions

Build Phase: Molecular Cloning Issues

The Build phase, particularly molecular cloning, is a frequent source of experimental challenges. The table below outlines common problems and evidence-based solutions.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Few or no transformants | Non-viable cells; incorrect heat-shock protocol; toxic DNA insert; inefficient ligation [5] | Transform uncut plasmid to check cell viability; use fresh ligation buffer with ATP; incubate at lower temperature (25-30°C) for toxic inserts [5] |

| Too much background growth | Incomplete restriction digestion; inefficient dephosphorylation; low antibiotic concentration [5] | Run proper digestion controls; heat-inactivate enzymes before dephosphorylation; verify antibiotic concentration [5] |

| Colonies contain wrong construct | Recombination in host; incorrect PCR amplicon; internal restriction sites [5] | Use recA– strains (e.g., NEB 5-alpha); sequence verify inserts; analyze sequence for internal restriction sites [5] |

| Unexpected mutations in sequence | PCR errors; nuclease contamination [5] | Use high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase); clean up DNA fragments prior to assembly [5] |

Test Phase: Analytical and Screening Challenges

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in screening data | Inconsistent culturing conditions; assay technical noise; cellular heterogeneity [6] | Implement automated cultivation systems; increase biological replicates; use controlled growth conditions [7] |

| Poor correlation between omics data and product titer | Insufficient pathway coverage; missing regulatory elements; incorrect sample timing [3] | Include targeted proteomics for pathway enzymes; analyze at multiple time points; integrate multiple omics layers [3] |

Learn Phase: Modeling and Data Interpretation Challenges

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Machine learning models fail to generalize | Small training datasets; inappropriate feature selection; experimental bias [6] [3] | Use ensemble methods (e.g., gradient boosting); incorporate prior knowledge; apply transfer learning [6] |

| Inability to extract mechanistic insights | Black-box ML approaches; insufficient hypothesis generation [2] [7] | Combine ML with mechanistic modeling; use explainable AI techniques; design experiments specifically for learning [7] |

Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Workflows

Successful implementation of DBTL cycles relies on high-quality reagents and tools. The table below details essential materials and their applications in synthetic biology workflows.

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in DBTL Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Assembly Methods | NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly, Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate Assembly [4] | Modular assembly of genetic constructs from standardized parts during the Build phase [4] |

| Competent Cells | NEB 5-alpha, NEB 10-beta, NEB Stable Competent E. coli [5] | Transformation of assembled DNA constructs; specialized strains for large constructs or toxic genes [5] |

| Restriction Enzymes & Ligases | Various restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA Ligase, Quick Ligation Kit [4] [5] | Traditional cloning and modular assembly; DNA fragment preparation and vector construction [4] |

| High-Fidelity Polymerases | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [5] | PCR amplification of DNA fragments with minimal errors during the Build phase [5] |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | Crude cell lysate systems [7] | In vitro testing of enzyme expression and pathway function before full strain engineering [7] |

Case Study: Knowledge-Driven DBTL for Dopamine Production

A recent study demonstrates the practical application of a knowledge-driven DBTL cycle with upstream in vitro investigation for optimizing dopamine production in E. coli [7]. This approach highlights how strategic implementation of the DBTL framework can yield significant improvements in strain performance.

Experimental Methodology and Workflow

Initial In Vitro Investigation: Researchers first used cell-free protein synthesis systems to test different relative enzyme expression levels without the constraints of whole cells [7]

In Vivo Translation: Optimal expression levels identified in vitro were translated to the in vivo environment through high-throughput ribosome binding site (RBS) engineering [7]

Host Strain Engineering: The native E. coli host was engineered for increased L-tyrosine production (dopamine precursor) by depleting the transcriptional regulator TyrR and mutating the feedback inhibition of chorismate mutase/prephenate dehydrogenase (TyrA) [7]

Pathway Optimization: A bicistronic system expressing 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase (HpaBC) and L-DOPA decarboxylase (Ddc) was fine-tuned using RBS engineering to balance expression levels [7]

Results and Impact

This knowledge-driven DBTL approach achieved dopamine production of 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L (equivalent to 34.34 ± 0.59 mg/g biomass), representing a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over previous state-of-the-art in vivo production methods [7]. The study also provided mechanistic insights, demonstrating the impact of GC content in the Shine-Dalgarno sequence on RBS strength [7].

FAQs: DBTL Cycles in Synthetic Biology

Q: What is the primary advantage of using iterative DBTL cycles over single-pass engineering? A: Iterative DBTL cycles allow for continuous refinement of biological designs based on experimental data. Each cycle incorporates learning from previous iterations, enabling systematic convergence toward optimal strains rather than relying on one-time rational design, which often fails to account for biological complexity and unpredictable interactions [1] [6].

Q: How does machine learning address the "Learn" bottleneck in DBTL cycles? A: ML processes large, complex biological datasets to identify non-obvious patterns and generate predictive models that inform the next Design phase. This enables semi-automated recommendation of genetic designs likely to improve performance, significantly accelerating the engineering process [2] [3].

Q: What are the data requirements for effective machine learning in DBTL cycles? A: ML typically requires structured, high-quality datasets with sufficient examples to train accurate models. In synthetic biology, this often means combining multi-omics data (proteomics, transcriptomics) with phenotypic measurements from multiple engineered strains [6] [3]. Data standardization is crucial for effective learning across cycles.

Q: How can researchers mitigate combinatorial explosion in pathway optimization? A: Combinatorial explosion occurs when testing all possible combinations of genetic parts becomes infeasible. Strategic DBTL cycling with ML guidance helps explore the design space efficiently by focusing on the most promising regions, thus reducing experimental burden while still identifying high-performing combinations [6].

Q: What role does automation play in modern DBTL implementations? A: Automation is critical for high-throughput Building and Testing phases, enabling rapid construction and screening of numerous genetic variants. Automated biofoundries allow researchers to implement multiple DBTL cycles efficiently, dramatically reducing development timelines [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving the "Learn" Bottleneck

This guide helps researchers diagnose and solve common issues that cause delays in the "Learn" phase of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle.

1. Problem: Inadequate or Poor-Quality Data

- Question: Why are my machine learning (ML) models failing to make accurate predictions, leading to unsuccessful subsequent cycles?

- Diagnosis:

- Check if your experimental data is from low-throughput, manual methods.

- Verify for inconsistencies in how data is recorded and labeled across different experiments or team members.

- Assess if the dataset is too small for the complexity of the biological system you are modeling.

- Solution: Implement automated, high-throughput testing systems to generate large, consistent datasets rapidly [8] [9]. Use integrated software platforms that enforce standardized data formats and metadata recording from the point of data generation [8].

2. Problem: Inefficient Model Training and Learning

- Question: How can I accelerate the learning process from experimental data to inform the next design?

- Diagnosis:

- Determine if you are relying solely on traditional statistical analysis without leveraging modern ML.

- Check if model training is a manual, time-consuming process that cannot keep pace with new data generation.

- Solution: Integrate ML algorithms that are specifically designed to work with smaller datasets ("low-N" ML) [9]. Utilize platforms that automate the training of predictive models on experimental data to make genotype-to-phenotype predictions, turning data into actionable insights faster [8].

3. Problem: Lack of Integration Between Phases

- Question: Why is there a significant delay between the "Test" and "Learn" phases, and between "Learn" and the next "Design"?

- Diagnosis:

- Check if data from testing instruments must be manually transferred, formatted, and analyzed before learning can begin.

- Verify if design decisions are made separately from the data analysis environment.

- Solution: Adopt end-to-end biofoundry automation platforms where software automatically collects Test data, feeds it into ML models, and allows the outputs to directly inform the Design of the next variant library [8] [9]. This creates a continuous, closed-loop cycle.

Quantitative Impact of the Learn Bottleneck and Solutions

The tables below summarize the time, cost, and data challenges of the traditional "Learn" phase and the performance improvements offered by modern solutions.

Table 1: Traditional vs. AI-Powered Learn Phase

| Aspect | Traditional Learn Phase | AI/ML-Powered Learn Phase | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Analysis | Manual, time-consuming statistical analysis [10] | Automated machine learning models [8] [9] | Speed, ability to find complex patterns |

| Data Dependency | Relies on small, often private datasets [10] | Can leverage large public datasets and generate its own high-quality data [11] [9] | Better, more generalizable predictions |

| Predictive Power | Limited, based on direct experimental results only | High, can predict outcomes for unsynthesized variants [9] | Reduces number of physical experiments needed |

| Cycle Integration | Often disconnected from Design phase | Directly feeds into AI-driven Design for next cycle [9] | Creates a seamless, autonomous DBTL loop |

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Case Studies

| Engineering Campaign | Traditional Method Timeline (Estimated) | AI/Automated Platform Timeline | Fold Improvement | Variants Tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme (AtHMT) | Several months to years [10] | 4 weeks for 4 rounds [9] | 16-fold activity [9] | < 500 variants [9] |

| Enzyme (YmPhytase) | Several months to years [10] | 4 weeks for 4 rounds [9] | 26-fold activity [9] | < 500 variants [9] |

| Metabolic Pathway | Multiple, lengthy DBTL cycles [8] | Accelerated by ML-guided predictions [8] | 20-fold product increase [8] | Data used to train models [8] |

Experimental Protocol: Autonomous DBTL for Enzyme Engineering

This protocol is based on a generalized platform for AI-powered autonomous enzyme engineering [9].

1. Design of Variant Library

- Objective: Create a high-quality, diverse initial library of protein variants.

- Methodology:

- Input: Provide the wild-type protein sequence and a defined fitness objective (e.g., improved activity at neutral pH).

- AI Tools: Use a combination of unsupervised models:

- Output: A ranked list of ~180 single-point mutations for the initial Build phase.

2. Build via Automated Biofoundry

- Objective: Physically construct the designed DNA variants with high fidelity and throughput.

- Methodology:

- Automated Workflow: Utilize a biofoundry (e.g., iBioFAB) with integrated robotic arms and liquid handlers.

- Key Module - HiFi-assembly Mutagenesis: A high-fidelity DNA assembly method that eliminates the need for intermediate sequencing verification, ensuring a continuous workflow with ~95% accuracy [9].

- Process: The platform automates mutagenesis PCR, DNA assembly, transformation, colony picking, and plasmid purification in 96-well format without human intervention [9].

3. Test with High-Throughput Assays

- Objective: Rapidly characterize the performance (fitness) of each variant.

- Methodology:

- Automated Protein Expression & Assay: The biofoundry automates protein expression in a 96-well microtiter format, cell lysis, and the enzyme activity assay [9].

- Data Collection: Assay results (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence) are automatically recorded by plate readers and fed directly into the central data system [8] [9].

4. Learn with Machine Learning

- Objective: Analyze test data to predict the next, better set of variants.

- Methodology:

- Model Training: The fitness data from the Test phase is used to train a supervised machine learning model (e.g., a low-N ML model) to predict variant performance based on sequence [9].

- Iterative Design: This trained model is used to design the next library, often focusing on combining beneficial mutations from the first round. The cycle (L-D-B-T) repeats autonomously.

Workflow Visualization: AI-Enhanced DBTL Cycle

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, AI-driven DBTL cycle that accelerates the "Learn" phase.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Modern DBTL Cycles

| Item / Solution | Function in DBTL Cycle |

|---|---|

| Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM-2) | AI models that use evolutionary sequence data to zero-shot predict beneficial mutations, jump-starting the Design phase [11] [9]. |

| Structure-Based Design Tools (e.g., ProteinMPNN) | AI tools that design protein sequences which fold into a desired 3D structure, enabling precise engineering of stability and function [11]. |

| Automated Biofoundry (e.g., iBioFAB) | Integrated robotic platform that automates the Build and Test phases (transformation, colony picking, assay execution) for high-throughput and reproducibility [9]. |

| Integrated Software Platform (e.g., TeselaGen) | Centralized software that orchestrates the entire DBTL cycle, managing design, inventory, automated protocols, and data, ensuring seamless phase integration [8]. |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | In vitro protein synthesis platforms that accelerate the Build and Test phases by bypassing cell cloning and enabling direct testing of designed DNA templates [11]. |

| Low-N Machine Learning Models | Specialized ML algorithms that can make accurate predictions from the small datasets typically generated in initial DBTL cycles, accelerating learning [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our lab doesn't have a multi-million dollar biofoundry. Can we still address the "Learn" bottleneck? Yes. The core principle is better data management and leveraging accessible AI tools. You can start by standardizing your data recording and using cloud-based or on-premises software platforms to structure your data for analysis [8]. Many AI protein design tools (e.g., ESM-2, ProteinMPNN) are publicly available and can be used for the Design phase, even if the Build and Test phases are semi-automated [11] [9].

Q2: Is the goal to completely remove humans from the DBTL cycle? No. The goal is to augment human expertise. AI and automation handle repetitive, data-intensive tasks and explore vast sequence spaces more efficiently. Scientists define the initial problem, set the fitness objectives, and interpret the final biological insights from the results, focusing on higher-level strategy and innovation [10] [9].

Q3: What is the "LDBT" paradigm shift mentioned in recent literature? LDBT proposes reordering the cycle to Learn-Design-Build-Test. This reflects that with powerful pre-trained AI models (the "Learn" step first), you can make highly accurate, zero-shot predictions to design optimal variants without any prior experimental cycles in your specific system. This can potentially deliver functional solutions in a single pass, moving closer to a "Design-Build-Work" ideal [11].

Q4: How critical is data quality for a successful AI-enhanced Learn phase? It is paramount. The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is central to ML. Inconsistent, noisy, or poorly annotated data will lead to unreliable models and poor predictions. Investing in robust, automated, and standardized experimental protocols for the Test phase is a prerequisite for successful learning [8] [9].

Automated Recommendation Tools (ART) represent a transformative advancement in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, leveraging machine learning to bridge the "Learn" and "Design" phases of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle. These algorithms guide bioengineering efforts by using probabilistic models to recommend optimal genetic designs or experimental conditions, enabling researchers to achieve desired biological outcomes, such as increased production of valuable molecules, more efficiently than with traditional ad-hoc methods [3]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers successfully implement these powerful tools in their experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is an Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) in the context of DBTL cycles? ART is a machine learning system that closes the loop between the "Learn" and "Design" phases of the DBTL cycle. It trains a model on experimental data (e.g., from proteomics or promoter combinations) to predict system performance (e.g., product titer). Using sampling-based optimization, it then recommends a set of strains or conditions to build and test in the next cycle, alongside probabilistic predictions of their outcomes [3].

My experimental data is limited (<100 data points). Can I still use these machine learning algorithms effectively? Yes. Automated recommendation algorithms like ART are specifically designed for the data-sparse environments common in synthetic biology. They employ Bayesian approaches and probabilistic modeling, which are well-suited for making predictions and guiding experiments with limited data, unlike deep learning which requires larger datasets [3].

What is the difference between exploration and exploitation in the algorithm's recommendation? The algorithm balances a key trade-off:

- Exploitation: Recommending conditions similar to the best-performing ones found so far.

- Exploration: Recommending conditions in uncertain regions of the design space to gather new information and avoid local optima. Acquisition functions, such as Expected Improvement (EI), automatically manage this balance to maximize the chance of finding the global optimum [12].

Anomaly detection job is failing. What are the first recovery steps? A failed job may indicate a transient or persistent issue. The standard recovery procedure is:

- Force stop the corresponding datafeed using the API with the

forceparameter set totrue. - Force close the anomaly detection job using the API with the

forceparameter set totrue. - Restart the job via the management interface. If the job fails again immediately, it is a persistent issue requiring investigation of the node logs for specific error messages [13].

- Force stop the corresponding datafeed using the API with the

What is the minimum amount of data required to initialize an effective model? Requirements can vary, but a general rule of thumb is more than three weeks of data for periodic processes or a few hundred data buckets for non-periodic data. For specific metrics, the minimum is often the larger of either eight non-empty bucket spans or two hours of data [13].

Troubleshooting Guide

Poor Model Performance or Inaccurate Recommendations

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low predictive accuracy | Input features not predictive of output response [3] | Re-evaluate feature selection; incorporate different -omics data (e.g., transcriptomics) or design parameters. |

| Model fails to find global optimum | Improper balance between exploration and exploitation [12] | Adjust or change the acquisition function (e.g., ensure Expected Improvement is properly configured). |

| Recommendations are erratic or non-converging | High experimental noise or biological variability [14] | Increase biological replicates, review protocol standardization on automated platforms, and ensure model accounts for experimental error [12]. |

| Algorithm performs poorly from the start | Insufficient initial data to build a prior model [13] | Begin with a larger initial dataset or a design-of-experiments (DoE) set before starting the autonomous learning cycle. |

Platform and Integration Issues

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Failed data transfer between platform and algorithm | Incorrect data formatting or import/export errors [3] | Ensure data is exported in the required format (e.g., EDD-style .csv). Verify the importer module in the software framework is correctly configured [14]. |

| Robotic platform fails to execute recommended experiments | Scheduling conflicts or resource allocation errors on the platform [14] | Check the platform's scheduler system and the interoperability of all components (incubators, liquid handlers, readers). |

| "Failed" state in an anomaly detection job | Transient system error or resource contention [13] | Follow the standard recovery procedure: force stop the datafeed, force close the job, and restart it. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Optimizing a Lycopene Biosynthetic Pathway with BioAutomata

This protocol details the fully automated DBTL cycle for pathway optimization as performed by BioAutomata [12].

- 1. Objective Definition: Define the optimization goal. In this case, the objective was to maximize lycopene production in E. coli by fine-tuning the expression levels of genes in the biosynthetic pathway.

- 2. Initial Setup: Select the predictive model and acquisition function. The study used a Gaussian Process (GP) as the probabilistic model and Expected Improvement (EI) as the acquisition function to balance exploration and exploitation.

- 3. Automated Cycle Execution:

- Design: The Bayesian optimization algorithm selects the next batch of strain variants (points in the expression landscape) to evaluate based on the updated model.

- Build & Test: The iBioFAB robotic platform automatically constructs the genetic variants and measures their lycopene production.

- Learn: The new production data is fed back to the GP model, which updates its belief about the entire expression-production landscape. This cycle repeats autonomously.

- 4. Outcome: This approach evaluated less than 1% of all possible variants and outperformed random screening by 77% [12].

Protocol 2: Autonomous Optimization of Protein Production Induction

This protocol describes using a robotic platform with active learning to optimize inducer concentrations [14].

- 1. System Preparation:

- Biological System: Use bacterial strains (Bacillus subtilis or E. coli) with a GFP reporter gene under an inducible promoter.

- Robotic Platform: Utilize an integrated platform with incubators, liquid handlers (8-channel and 96-channel), and a plate reader.

- 2. Workflow Execution:

- The platform's software manager retrieves the next set of conditions (e.g., inducer concentration) from the database, which is populated by the optimizer module.

- The robotic arm transports microtiter plates to the liquid handler, which adds inducers and nutrients.

- Plates are incubated, and the plate reader periodically measures OD600 and fluorescence.

- 3. Data Analysis and Learning:

- An importer module retrieves measurement data from the plate reader and writes it to a database.

- The optimizer module (running a machine learning algorithm like Bayesian optimization or a random search baseline) analyzes the data to select the next most informative measurement points.

- The cycle runs for multiple consecutive iterations without human intervention [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials used in the featured experiments for setting up automated DBTL platforms.

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model | A probabilistic model that predicts the expected performance and uncertainty for untested genetic designs or conditions. | Used as the core predictive model in BioAutomata and ART [3] [12]. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | An acquisition function that recommends the next experiments by calculating the point offering the highest expected improvement over the current best. | Balances exploration and exploitation in Bayesian optimization [12]. |

| Microbial Chassis | The host organism (e.g., E. coli, yeast) that is engineered to produce the target molecule. | E. coli for lycopene [12]; Bacillus subtilis and E. coli for GFP [14]. |

| Reporter Protein | A measurable protein (e.g., GFP) used as a proxy for system performance and to rapidly collect data. | GFP for optimizing induction parameters [14]. |

| Inducers | Chemicals that trigger gene expression from specific promoters (e.g., IPTG, lactose). | Key variables for optimizing protein production in bacterial systems [14]. |

| Robotic Liquid Handler | Automates the dispensing of liquids (culture media, inducers) in microtiter plates, ensuring high reproducibility. | CyBio FeliX liquid handlers [14]. |

| Plate Reader | Integrated into the robotic platform to automatically measure optical density (OD600, for growth) and fluorescence (for production). | PHERAstar FSX plate reader [14]. |

Automated DBTL Workflow with Machine Learning Bridge

The following diagram illustrates the continuous cycle of an algorithm-driven DBTL platform.

Bayesian Optimization Algorithm Workflow

This diagram details the core algorithmic process within the "Learn" and "Design" phases.

FAQs: Recommendation Systems in DBTL Cycles

FAQ 1: What are the core types of recommendation systems and how are they applied in a biological DBTL cycle?

Recommendation systems in DBTL cycles primarily use three filtering approaches to suggest optimal strain designs [15] [16] [17]:

- Collaborative Filtering: Recommends designs based on the performance of similar strains or from similar users, without needing detailed biological knowledge. It struggles with new projects lacking historical data (cold start problem) [16] [18].

- Content-Based Filtering: Recommends strain designs based on known biological features (e.g., promoter strengths, RBS sequences, enzyme concentrations). It is robust for new projects but can miss novel, high-performing designs by focusing only on existing feature spaces [15] [16].

- Hybrid Filtering: Combines both collaborative and content-based methods to mitigate their individual weaknesses. For example, the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) uses a hybrid, ensemble machine learning approach to guide synthetic biology projects, leveraging probabilistic modeling to recommend new strains for the next DBTL cycle [3] [19] [20].

FAQ 2: Our research group is new to ML. What is a recommended, user-friendly tool for implementing recommendations in our DBTL cycle?

The Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) is specifically designed to leverage machine learning for synthetic biology without requiring deep ML expertise [3]. It integrates with the scikit-learn library and uses a Bayesian ensemble approach, which is tailored for the low-data, high-noise experimental environments common in biological research. ART is designed to bridge the Learn and Design phases by providing a set of recommended strains to build next, alongside probabilistic predictions of their production levels [3].

FAQ 3: How do we evaluate the performance and success of our recommendation system?

Evaluation happens at two levels: the machine learning model and the business/biological outcome [15].

- Model-Centric Metrics: Depending on your algorithm, use similarity metrics (e.g., Cosine similarity, Jaccard similarity) for content-based systems, or predictive and classification metrics (e.g., Mean Absolute Error, Precision, Recall) for collaborative and hybrid systems [15] [18].

- Business/Biological Metrics: The ultimate success is measured by the improvement in your Target Molecule's Titer, Rate, and Yield (TRY) [15] [3]. The recommendation system's goal is to help you reach your production target faster and with fewer experimental cycles.

FAQ 4: We face a "cold start" problem with a new pathway. How can we overcome this?

The cold start problem occurs when there is no prior user interaction or performance data [16] [21]. Solutions include:

- Leverage Content-Based Features: Start by using a content-based or hybrid approach. Use available biological features (e.g., DNA library parts, proteomics data, promoter strengths) to make initial recommendations [16] [19].

- Implement a Knowledge-Driven DBTL Cycle: Conduct upstream in vitro investigations, such as testing enzyme expression and pathway flux in cell-free systems, to generate initial data and guide the first in vivo engineering cycle [7].

- Use Global Recommendations: Begin with a "global" strategy, such as testing the most popular or theoretically optimal genetic parts from literature, to bootstrap your initial dataset [15].

FAQ 5: Our experimental data is noisy and limited. Is machine learning still viable?

Yes. Machine learning methods like Random Forest and Gradient Boosting have been shown to be particularly robust and effective in the low-data, noisy regimes typical of early DBTL cycles [6]. Furthermore, tools like ART are specifically designed for these conditions, using probabilistic modeling to quantify prediction uncertainty, which helps guide experimental design even when absolute accuracy is lower [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Stagnating DBTL Cycles - Failure to Improve Production Titer After Multiple Rounds

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Recommendations are always similar to past high-performers. | Over-exploitation by the algorithm, leading to a lack of diversity and exploration of the design space. | Adjust the exploration/exploitation parameter in your tool (e.g., in ART). Increase the weight on exploration to recommend riskier but potentially higher-performing strains [3]. |

| Model predictions are inaccurate and unreliable. | Data sparsity or a training set bias from a non-representative initial DNA library. | * Use a hybrid recommendation system to incorporate different data types [19].* In the next cycle, consciously build strains that cover a wider range of the biological feature space to reduce bias [6]. |

| The algorithm fails to learn from cyclical data. | Incorrect model choice for the data type and size. | For combinatorial pathway optimization with limited data, switch to or incorporate ensemble models like Random Forest or Gradient Boosting, which are known to be effective in this context [6]. |

Problem: The "Cold Start" - Unable to Generate Meaningful Initial Recommendations

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No prior data for the new pathway or host. | The collaborative filtering approach has no user-item interactions to learn from. | Switch from a collaborative to a content-based or hybrid approach from the outset [16] [19]. Use any available meta-data about the genetic parts (e.g., promoter strength, RBS sequence, terminator efficiency) [15]. |

| Even content-based filtering lacks features. | Limited mechanistic understanding of the pathway. | Adopt a knowledge-driven DBTL approach. Use in vitro cell-free systems to rapidly test pathway components and generate initial performance data to feed into the recommendation system [7]. |

Table 1: Comparison of Core Recommendation Filtering Techniques

| Technique | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Biological Context Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative Filtering [15] [16] | Leverages behavior/performance data from similar users/strains. | No domain knowledge needed; can discover novel serendipitous connections. | Cold start problem; requires large amounts of data; can be computationally intensive. | Recommending a promoter to User A because it worked well in a similar strain built by User B. |

| Content-Based Filtering [15] [16] | Suggests items similar to those a user/strain has liked before, based on item features. | No cold-start for new users; highly transparent and interpretable. | Requires good feature data; limits discovery (no serendipity); can over-specialize. | Recommending a strong RBS because strong RBSs have historically led to high protein expression in your system. |

| Hybrid Filtering [19] [20] | Combines collaborative and content-based methods. | Mitigates weaknesses of individual methods; more robust and accurate. | More complex to implement and maintain. | Using ART to combine proteomics data (content) with historical strain performance data (collaborative) [3]. |

Table 2: Performance of Machine Learning Models in Simulated DBTL Cycles (Low-Data Regime) [6]

| Machine Learning Model | Robustness to Training Set Bias | Robustness to Experimental Noise | Relative Performance for Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting | High | High | Top Tier |

| Random Forest | High | High | Top Tier |

| Other Tested Methods (e.g., Linear Models) | Lower | Lower | Lower |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Hybrid Recommendation System with ART

Objective: To integrate the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) into a DBTL cycle for optimizing microbial production of a target compound (e.g., dopamine [7], biofuels [3]).

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the automated DBTL cycle, with ART central to the Learn and Design phases.

Materials/Reagents:

- Biological Strains: Microbial chassis (e.g., E. coli FUS4.T2 for dopamine production [7]).

- Genetic Parts: Plasmid system (e.g., pET or pJNTN vectors [7]), promoter/RBS library, genes of interest (e.g., hpaBC, ddc for dopamine [7]).

- Software & Data: Python environment with ART installation [3], access to an Experimental Data Depo or standardized .csv files for data input [3].

- Culture & Assay: Appropriate growth medium (e.g., defined minimal medium [7]), analytical equipment for titer measurement (HPLC, GC-MS).

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Initial Design & Build:

- Design an initial library of strain variants. For a new project, this can be based on rational design or a diverse sampling of genetic parts (e.g., a set of RBS sequences with varying predicted strengths [7]).

- Build these strains using standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., cloning, CRISPR).

Test & Data Collection:

- Cultivate the built strains under controlled conditions in a microtiter plate or bioreactor.

- Measure the key performance indicator (Titer, Rate, or Yield) for each strain variant.

- Compile the data into a standardized format. ART can import data directly from an Experimental Data Depo or from EDD-style .csv files [3]. The dataset should clearly link each strain design (input features) to its production level (output response).

Learn with ART:

- Input the historical data (including all previous cycles) into ART.

- ART trains an ensemble of machine learning models to build a predictive function that links your strain designs to production levels. Instead of a single prediction, ART provides a full probability distribution for the production level of any new design, rigorously quantifying uncertainty [3].

- Define your objective within ART (e.g., "Maximize production," "Minimize toxicity," or "Achieve a specific production level" [3]).

Recommendation:

- ART uses sampling-based optimization on the probabilistic model to provide a set of recommended strains to be built in the next DBTL cycle [3].

- The recommendations balance exploring uncertain regions of the design space and exploiting known high-performing regions.

Iterate:

- The recommended strains form the Design basis for the next DBTL cycle.

- Repeat the cycle until the production objective is met or the design space is sufficiently explored.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for DBTL-Driven Strain Engineering

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) [3] | Machine learning tool that uses Bayesian ensemble models to recommend the best strain designs for the next DBTL cycle based on all accumulated data. | Used to optimize production of renewable biofuels, fatty acids, and tryptophan, leading to a 106% productivity increase in tryptophan production [3]. |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Library [7] | A set of DNA sequences with varying translation initiation rates, used to fine-tune the expression levels of pathway enzymes without changing the coding sequence. | Used in a knowledge-driven DBTL cycle to optimize relative enzyme expression for dopamine production in E. coli [7]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System [7] | A crude cell lysate used for in vitro transcription and translation. Allows for rapid testing of enzyme expression and pathway flux without the constraints of a living cell, generating data to inform the first in vivo cycle. | Leveraged to test different relative enzyme expression levels for a dopamine pathway before moving to in vivo strain construction, accelerating the learning phase [7]. |

| Core Kinetic Model (e.g., in SKiMpy) [6] | A mechanistic model of cellular metabolism that uses ordinary differential equations. Can simulate the effect of perturbations (e.g., changing enzyme concentrations) on flux, used to generate in-silico data for benchmarking ML methods. | Used to create a simulated metabolic engineering scenario for benchmarking machine learning models like Gradient Boosting and Random Forest [6]. |

Implementing AI Recommenders: Tools, Techniques, and Real-World Workflows

The Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) is a machine learning tool designed to guide synthetic biology projects in a systematic fashion, without the need for a full mechanistic understanding of the biological system [3]. It powerfully enhances the Learn phase of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle [3]. In traditional synthetic biology, the Learn phase is often the most weakly supported, hindering the rapid development of strains for producing valuable molecules like biofuels or pharmaceuticals. ART bridges the Learn and Design phases by using data from previous cycles to build predictive models and recommend which strains to build and test next, thereby accelerating the entire bioengineering process [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Core Functionality

Q: What is the primary function of ART? A: ART leverages machine learning and probabilistic modeling to predict the performance of biological systems (e.g., production of a target molecule) and provides a set of recommended genetic designs to be built and tested in the next DBTL cycle [3].

Q: What types of engineering objectives does ART support? A: ART supports three common metabolic engineering objectives [3]:

- Maximization: Increasing the titer, rate, or yield (TRY) of a target molecule.

- Minimization: Decreasing the production of a toxic by-product.

- Specification: Achieving a specific level of a molecule for a desired product profile.

Data and Modeling

Q: What kind of data can ART use? A: ART can use various data types as input, including promoter combinations, proteomics data, and other -omics data that can be expressed as a vector [3]. It can import data directly from Experimental Data Depo (EDD) or from EDD-style CSV files [3].

Q: How does ART handle prediction uncertainty? A: Instead of providing only a single prediction, ART provides a full probability distribution for the possible outcomes. This rigorous quantification of uncertainty is crucial for gauging prediction reliability and guiding recommendations toward the least-known parts of the design space [3].

Q: My dataset is small (less than 100 data points). Can I still use ART? A: Yes. ART is specifically tailored for the data-sparse environments typical in synthetic biology, where generating data is expensive and time-consuming. Its Bayesian ensemble approach is designed to function effectively with limited training instances [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance or Inaccurate Predictions

Problem: The model's predictions do not match the experimental test results.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient or low-quality training data. | Increase the number of engineered variants in your training set. Ensure experimental measurements are reproducible and accurate. |

| The chosen input features are not predictive of the output response. | Re-evaluate your experimental design. Consider using different -omics data (e.g., transcriptomics) or genetic parts (e.g., different promoter libraries) that may have a stronger causal link to production. |

| Underlying biological assumptions are violated. | ART assumes that recommended inputs can be built and will express as designed. Verify that genetic constructs are built correctly and that the host chassis can accommodate the changes. |

Issue 2: Data Formatting and Import Errors

Problem: ART cannot read the provided data file.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| File is not in a compatible format. | Use the standard EDD export format. Ensure your CSV file follows EDD nomenclature and structure exactly [3]. |

| Missing metadata or incorrect column headers. | Consult the EDD documentation and the "Importing a study" section in ART's supplementary information to ensure all required fields are present and correctly labeled [3]. |

Issue 3: Interpreting Recommendations

Problem: It is unclear how to proceed with the list of strains recommended by ART.

Solution:

- ART provides a set of recommendations, not just one. It is advisable to build multiple top recommendations in parallel to maximize the chance of success [3].

- Use the provided probabilistic predictions to set experimental priorities. A strain with a slightly lower predicted yield but higher uncertainty might be worth investigating to expand the model's knowledge.

- Cross-reference recommendations with biological knowledge. If a recommendation seems biologically infeasible, it may indicate a problem with the model or training data.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an ART-Guided DBTL Cycle

This protocol outlines the methodology for using ART to guide the optimization of a microbial production strain, as demonstrated in experimental work on tryptophan and dopamine production [3] [22].

Design Phase

- Define Goal: Specify the engineering objective (e.g., maximize dopamine production) [22].

- Plan Library: Design a library of genetic variants. This could involve modulating enzyme expression levels using tools like RBS engineering [22].

Build Phase

- Strain Construction: Use automated genetic engineering tools to build the planned library of strains in your chosen microbial host (e.g., E. coli) [22].

Test Phase

- Cultivation & Assaying: Cultivate the built strains in a defined medium under controlled conditions and assay for the desired output (e.g., dopamine titer) and potential input features (e.g., targeted proteomics) [3] [22].

- Data Collection: Collect data in a standardized format. Record production yields and corresponding -omics or part combination data for each strain.

Learn Phase with ART

- Data Import: Import the collected data into ART.

- Model Training: Train ART's machine learning model on the data to learn the relationship between inputs (e.g., proteomics) and the output (e.g., production) [3].

- Generate Recommendations: Use ART to obtain a list of recommended strains (e.g., specific proteomic profiles or genetic designs) predicted to improve performance in the next cycle [3].

Cycle Iteration

- Return to the Design Phase, using ART's recommendations to inform the design of the next strain library. Repeat the DBTL cycle until the production goal is met.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials used in a typical metabolic engineering project that could be optimized with ART, such as the development of a dopamine production strain [22].

| Research Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| E. coli FUS4.T2 | A production host strain engineered for high precursor (l-tyrosine) production [22]. |

| Plasmids with RBS libraries | Vectors containing the heterologous pathway genes (e.g., hpaBC, ddc) with modified Ribosome Binding Sites to fine-tune enzyme expression levels [22]. |

| Defined Minimal Medium | Provides essential nutrients and a controlled environment for reproducible fermentation and metabolite production [22]. |

| Inducer (IPTG) | A chemical used to precisely trigger the expression of genes in the engineered pathway [22]. |

| Analytical Standards (e.g., Dopamine) | Pure chemical compounds used as references for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to identify and quantify metabolite production [22]. |

Conceptual Foundation: FAQs on the LDBT Paradigm

FAQ 1: What is the LDBT cycle, and how does it fundamentally differ from the traditional DBTL cycle?

The LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) cycle represents a paradigm shift from the established DBTL (Design-Build-Test-Learn) cycle in synthetic biology and bioengineering. In the traditional DBTL cycle, knowledge is gained retrospectively by analyzing data from the "Test" phase to inform the next "Design" round, often requiring multiple, time-consuming iterations. In contrast, the LDBT cycle places "Learn" at the forefront by leveraging advanced machine learning models capable of zero-shot prediction. This allows researchers to start with a knowledge-rich foundation, generating initial designs that are already highly informed, potentially reducing the need for multiple iterative cycles and accelerating the path to functional biological systems [23].

FAQ 2: What is zero-shot learning in the context of protein and pathway engineering?

Zero-shot learning refers to the capability of a machine learning model to make accurate predictions on data it was never explicitly trained on. In protein engineering, this is achieved by models that have been pre-trained on vast, evolutionary-scale datasets comprising millions of protein sequences or hundreds of thousands of structures. These models learn the underlying "grammar" of protein sequences and structures, allowing them to predict the function, stability, or beneficial mutations for a novel protein sequence without requiring additional, task-specific training data. This enables the "Learn" phase to precede any physical "Build" or "Test" activity [23].

FAQ 3: What are the primary advantages of using a cell-free system in the "Build" and "Test" phases?

Cell-free gene expression systems are a critical enabler for the LDBT paradigm. They use the protein synthesis machinery from cell lysates or purified components in an in vitro setting. Their key advantages include [23]:

- Speed: They can produce more than 1 gram per liter of protein in under 4 hours.

- Throughput: They are easily integrated with liquid handling robots and microfluidics, allowing for the screening of hundreds of thousands of reactions (e.g., in picoliter-scale droplets).

- Flexibility: They can express proteins that are toxic to living cells and allow for easy customization of the reaction environment, including the incorporation of non-canonical amino acids.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Poor zero-shot prediction performance for my target protein.

- Problem: The designed sequences from a zero-shot model fail to show the desired function or stability when tested.

- Solution:

- Model Selection: Verify you are using the appropriate model for your task. Sequence-based language models (e.g., ESM, ProGen) are excellent for capturing evolutionary relationships, while structure-based models (e.g., ProteinMPNN, MutCompute) are better for stability and fold-specific design. A hybrid approach may be necessary [23].

- Input Quality: For structure-based models, ensure the input protein backbone structure is of high quality. Inaccurate structural templates will lead to poor sequence design.

- Model Augmentation: Consider using models that have been augmented with additional biophysical or evolutionary information, as they often show enhanced predictive power for specific functions like thermostability or solubility [23].

Issue 2: Low yield or misfolded protein in cell-free expression.

- Problem: The protein of interest is not expressed efficiently or is insoluble in the cell-free reaction.

- Solution:

- Template Quality: Ensure the DNA template is pure and of sufficient concentration. Linear DNA templates can be used for rapid prototyping without cloning.

- Codon Optimization: Check if the gene sequence has been optimized for the specific cell-free system you are using (e.g., derived from E. coli, wheat germ).

- Reaction Conditions: Optimize the reaction environment. Key parameters to adjust include magnesium and potassium ion concentrations, energy source concentration (e.g., phosphoenolpyruvate), and incubation temperature [23].

Issue 3: High background noise in high-throughput cell-free screening assays.

- Problem: The signal-to-noise ratio in the functional assay (e.g., fluorescence-based) is too low to reliably distinguish active variants.

- Solution:

- Assay Validation: First, validate the assay with a known positive control and a negative control in a low-throughput format.

- Reagent Purity: Confirm the purity of substrates and co-factors used in the assay. Impurities can lead to high background.

- Dispensing Accuracy: When using microfluidics or liquid handlers, check for consistent and accurate droplet or well dispensing. Inconsistent volumes can cause significant signal variation [23].

Experimental Protocols for LDBT Workflows

Protocol 1: In Silico Protein Variant Design Using a Zero-Shot Model

This protocol outlines the steps for designing novel protein variants using a pre-trained, zero-shot capable model.

- Objective: To generate a library of protein variant sequences predicted to have enhanced functional properties (e.g., enzymatic activity, stability) without prior experimental data on the target.

- Methodology:

- Define Input: For a structure-based model like ProteinMPNN, provide the 3D atomic coordinates of your target protein's backbone in PDB format. For a sequence-based model like ESM-2, provide the wild-type amino acid sequence in FASTA format.

- Set Parameters: Specify design constraints, such as which residues are allowed to mutate and which must remain fixed.

- Run Model: Execute the model to generate a set of predicted variant sequences. The number of sequences can range from hundreds to thousands.

- Filter Output: Rank the generated sequences based on the model's confidence score or other integrated metrics (e.g., predicted ΔΔG for stability). Select the top candidates for synthesis.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Protein Function Screening via Cell-Free Expression

This protocol describes how to rapidly test the function of hundreds of designed protein variants using a cell-free system.

- Objective: To experimentally measure the functional output (e.g., enzyme activity, binding affinity) of a large number of protein variants designed in silico.

- Methodology:

- DNA Template Preparation: Synthesize the DNA templates for the selected variants as linear fragments or cloned plasmids. Normalize the DNA concentration.

- Cell-Free Reaction Assembly: Use an automated liquid handler to dispense cell-free reaction mix into a 96-well or 384-well plate. Add individual DNA templates to separate wells.

- Expression Incubation: Incubate the plate at a defined temperature (e.g., 30-37°C) for 2-4 hours to allow for protein synthesis.

- Functional Assay: Directly add the relevant assay reagents to the same well. For an enzymatic assay, this would include the substrate and any necessary cofactors. Measure the output (e.g., fluorescence, absorbance) using a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Normalize the activity signals, identify top-performing variants, and correlate the experimental results with the in-silico predictions.

Performance Metrics of Zero-Shot Learning Models

The table below summarizes the predictive performance of various zero-shot learning models as cited in recent literature, providing a benchmark for researchers.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Zero-Shot Learning Models in Biology

| Model Name | Model Type | Primary Application | Reported Performance / Advantage | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESM & ProGen | Protein Language Model (Sequence-based) | Predicting beneficial mutations, inferring function, designing antibody sequences. | Capable of zero-shot prediction of diverse antibody sequences; used to design libraries for engineering enantioselective biocatalysts [23]. | [23] |

| MutCompute | Structure-based Deep Neural Network | Residue-level optimization for stability/function. | Successfully engineered a hydrolase for increased stability and PET depolymerization activity [23]. | [23] |

| ProteinMPNN | Structure-based Deep Learning | Designing sequences that fold into a given protein backbone. | Led to a nearly 10-fold increase in design success rates when combined with AlphaFold/RoseTTAFold [23]. | [23] |

| AI Sleep Apnea Model | Machine-learning (Clinical) | Predicting adverse outcomes of obstructive sleep apnea. | Predicted sleepiness with ~87% accuracy and cardiovascular mortality with ~81% accuracy, outperforming the standard index [24]. | [24] |

| LogitMat | Zero-shot Learning Algorithm (Recommender Systems) | Tackling cold-start problems without transfer learning. | Generates competitive results by leveraging Zipf Law properties of user-item rating values; described as fast, robust, and effective [25]. | [25] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and reagents essential for implementing the LDBT cycle, specifically the Build and Test phases.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for LDBT Cycle Implementation

| Reagent / Material | Function in LDBT Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Kit | Provides the biological machinery for in vitro transcription and translation in the "Build" phase. | Choose based on source organism (e.g., E. coli, wheat germ), yield, and ability to produce functional, complex proteins [23]. |

| Linear DNA Template | Serves as the genetic blueprint for protein expression in cell-free systems. | Enables rapid "Building" without time-consuming cloning steps; purity and sequence accuracy are critical [23]. |

| Microfluidic Droplet Generator | Partitions reactions into picoliter-volume droplets for ultra-high-throughput "Testing." | Allows screening of >100,000 variants in a single experiment; requires compatible surfactants and oils [23]. |

| Fluorescent or Colorimetric Assay Substrates | Enables detection and quantification of protein function (e.g., enzyme activity) in the "Test" phase. | Must be specific, sensitive, and compatible with the cell-free reaction environment and high-throughput detection systems [23]. |

Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagrams

LDBT Cycle Flow

LDBT Troubleshooting Guide

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource addresses common challenges researchers face when integrating cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems with automated biofoundries. The guidance is framed within the context of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, enhanced by automated recommendation algorithms.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can machine learning accelerate the DBTL cycle in a biofoundry? Machine learning (ML) models, such as the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART), leverage experimental data to predict optimal genetic designs, drastically reducing the number of experimental cycles needed. ART uses a Bayesian ensemble approach to recommend strain designs or proteomic profiles likely to improve production titers, effectively bridging the Learn and Design phases of the DBTL cycle [3]. This is particularly valuable for optimizing "black-box" biological systems where a full mechanistic understanding is lacking [12].

FAQ 2: What are the key advantages of using CFPS over cell-based systems in automated workflows? CFPS platforms are cell-free and offer an open, programmable environment. This decouples gene expression from cell viability and growth constraints, enabling several key advantages for automation [26]:

- Rapid Iteration: Eliminates lengthy transformation and cell cultivation steps.

- High-Throughput Compatibility: Easily miniaturized for parallel experimentation in microplates or droplets.

- Precise Control: Allows direct manipulation of reaction conditions, enzyme concentrations, and cofactors.

- Tolerance: Capable of expressing toxic proteins or producing labile intermediates that would inhibit cell-based systems [26].

FAQ 3: What are the essential components of a functional CFPS reaction? A functional CFPS system requires a specific set of biochemical components to execute transcription and translation in vitro [26]:

Table 1: Core Components of a Cell-Free Protein Synthesis System

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Template | Plasmid DNA, linear PCR products | Provides the genetic blueprint for the protein to be synthesized. |

| Enzymatic Machinery | RNA polymerase, ribosomes, translation factors | Orchestrates the processes of transcription and translation. |

| Energy Source | Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), creatine phosphate | Regenerates ATP/GTP to sustain prolonged reaction activity. |

| Building Blocks | Amino acids, nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) | The raw materials for synthesizing proteins and RNA. |

| Cofactors & Salts | Mg2+, K+, NAD+, CoA | Maintains optimal ionic and biochemical conditions for enzyme function. |

FAQ 4: How does a fully automated, algorithm-driven DBTL platform work? Platforms like BioAutomata integrate robotic hardware with machine learning in a closed-loop system. The workflow is as follows [12]:

- A predictive model (e.g., Gaussian Process) is trained on available data to create a probabilistic "landscape" of system performance.

- An acquisition policy (e.g., Expected Improvement algorithm) selects the most informative set of experiments to perform next.

- An automated biofoundry (e.g., the iBioFAB) executes the recommended experiments.

- Results are fed back to the model, which updates its predictions.

- The cycle repeats autonomously until a performance objective is met, evaluating only a tiny fraction of the total possible design space [12].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Low or No Protein Yield in CFPS Reactions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Yield in CFPS

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Consistently low yield across all designs | Depleted energy system; suboptimal reaction conditions | Verify the integrity of the energy regeneration system (e.g., PEP). Titrate essential cofactors (Mg2+) and use a structured experimental design (e.g., DoE) to optimize concentrations [26]. |

| Low yield with a specific genetic construct | Poor translation initiation; toxic protein | Redesign the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) using computational tools (e.g., UTR Designer) to modulate strength [7]. Consider using a different cell lysate (e.g., wheat germ for complex eukaryotic proteins) [26]. |

| High variability between replicate reactions | Inconsistent lysate preparation or pipetting errors | Standardize the lysate preparation protocol. On an automated platform, ensure regular calibration of liquid-handling robots and use of clean, contamination-free labware [27]. |

Issue 2: High-Throughput Data is Noisy and Inconsistent

- Cause: Technical variability in automated liquid handling, sensor calibration drift, or non-standardized protocols can obscure biological signals.

- Solution:

- Implement Alerting: Set up automated monitoring and alerting for key platform metrics, such as pipetting accuracy or incubator temperature, to quickly identify and respond to hardware issues [27].

- Regular Training: Provide continuous training for personnel on monitoring and alerting tools to build confidence and efficiency in troubleshooting [27].

- Standardize Protocols: Use integrated software platforms like

AssemblyTronorSynBiopythonto standardize DNA assembly and experimental workflows across the biofoundry, improving reproducibility [28].

Issue 3: Machine Learning Recommendations Are Not Improving System Performance

- Cause: The input features (e.g., promoter combinations, proteomics data) may not be predictive of the desired output, the training data set may be too small, or the underlying biological assumptions may be incorrect [3].

- Solution:

- Feature Re-evaluation: Re-assess the chosen input variables. A knowledge-driven approach, such as preliminary in vitro CFPS testing to inform which enzyme levels are critical, can provide more mechanistic insight and better features for the model [7].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Use an ML tool like ART, which provides probabilistic predictions. Prioritize experiments in regions of the design space with high uncertainty (exploration) to improve the model's global understanding, not just in areas predicted to be high-performing (exploitation) [3] [12].

- Increase Data Volume: Leverage the high-throughput capacity of the biofoundry to generate larger training data sets, which generally improve model accuracy [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Knowledge-Driven DBTL for Pathway Optimization

This protocol details a methodology for optimizing a metabolic pathway, as demonstrated for dopamine production in E. coli [7]. It combines upstream in vitro testing with high-throughput in vivo engineering.

1. Design Phase: In Vitro Pathway Prototyping with CFPS

- Objective: Rapidly identify rate-limiting enzymes and optimal relative expression levels without the constraints of a living cell.

- Methodology: a. Construct Design: Clone genes of interest (e.g., hpaBC and ddc for dopamine) into compatible expression plasmids for the CFPS system [7]. b. CFPS Reaction: Use a crude cell lysate CFPS system (e.g., E. coli S30 extract) supplemented with an energy source, amino acids, and NTPs [26]. c. Expression Titration: Set up reactions with varying DNA template ratios to mimic different expression levels of the pathway enzymes. d. Product Quantification: After incubation, measure the concentration of the target product (e.g., dopamine) using HPLC or other analytical methods. This data identifies which enzyme ratios maximize flux through the pathway [7].

2. Build Phase: High-Throughput RBS Library Construction

- Objective: Translate the optimal expression ratios identified in vitro into a library of production strains.

- Methodology: a. RBS Design: Design a library of RBS sequences with varying translation initiation rates (TIR). A simplified approach is to modulate the Shine-Dalgarno sequence while keeping flanking regions constant to minimize secondary structure impacts [7]. b. Automated DNA Assembly: Use automated biofoundry platforms (e.g., with j5 and Opentrons robotics) to assemble the RBS variants into the target pathway construct [28]. c. Strain Transformation: Automatically transform the constructed library into a high-producing chassis strain (e.g., an E. coli strain engineered for high precursor supply) [7].

3. Test Phase: Automated Screening

- Objective: Characterize the library strains for product yield.

- Methodology: a. High-Throughput Cultivation: Using liquid handling robots, inoculate deep-well plates with the library strains and cultivate them in a defined medium [7]. b. Analytics: Automatically sample the cultures and quantify product titer and biomass using methods like online HPLC or spectrophotometry [12].

4. Learn Phase: Data Analysis and Model-Guided Redesign

- Objective: Identify top-performing strains and inform the next DBTL cycle.

- Methodology: a. Data Analysis: Correlate RBS sequence features (e.g., GC content) with production titers [7]. b. Machine Learning: Input the "Build" and "Test" data into a tool like ART. The model will predict the performance of untested RBS combinations and recommend a new set of strains to build in the next cycle, aiming for even higher production [3].

Workflow Visualization: Automated DBTL Cycle with Machine Learning

The following diagram illustrates the fully integrated, algorithm-driven DBTL cycle that forms the core of a modern biofoundry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential materials and tools for conducting research at the intersection of CFPS, biofoundries, and automated DBTL cycles.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item | Function/Description | Example Tools / Components |

|---|---|---|

| CFPS Lysates | Source of transcriptional/translational machinery. Choice affects folding and post-translational modifications. | E. coli S30 extract, wheat germ extract, reconstituted PURE system [26]. |

| Automated Recommendation Tool | Machine learning software to guide the DBTL cycle by predicting optimal designs from data. | Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) [3]. |

| DNA Assembly Software | Standardizes and automates the design of complex DNA assemblies for robotic construction. | j5, AssemblyTron [28]. |

| Liquid Handling Robots | Core hardware for automating pipetting, dilution, and plate preparation in high-throughput workflows. | Opentrons, integrated systems in iBioFAB [28] [12]. |

| Energy Regeneration Systems | Maintains ATP/GTP levels to prolong CFPS reaction duration and increase protein yield. | Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), creatine phosphate [26]. |

| RBS Library Kits | Pre-designed genetic parts for fine-tuning gene expression levels within a synthetic pathway. | Libraries of Shine-Dalgarno sequence variants [7]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | The core computational engine for efficient black-box optimization, balancing exploration and exploitation. | Gaussian Process with Expected Improvement acquisition function [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core innovation of the knowledge-driven DBTL cycle compared to a traditional DBTL approach? The knowledge-driven DBTL cycle incorporates upstream in vitro investigation before the first full engineering cycle begins. This provides mechanistic understanding of the system, such as enzyme expression and interaction, which is then used to rationally select engineering targets for the subsequent in vivo DBTL cycles. This contrasts with traditional DBTL cycles that often start with statistical or random selection of targets, which can be more time and resource-intensive [22].

FAQ 2: Why is ribosome binding site (RBS) engineering a preferred method for fine-tuning metabolic pathways in this context?

RBS engineering allows for the precise control of translation initiation rates without altering the promoter or the coding sequence itself. In the dopamine production case, high-throughput RBS engineering was used to balance the expression of genes in the bicistronic operon (e.g., hpaBC and ddc), which is crucial for optimizing the flux through the pathway and minimizing the accumulation of intermediate metabolites like L-DOPA [22] [29].

FAQ 3: How does the "LDBT" paradigm differ from the classic "DBTL" cycle, and is it relevant to this work? The LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) paradigm proposes a shift where machine learning (Learn) based on large existing datasets precedes the Design phase. This can enable highly accurate, zero-shot predictions of functional biological parts, potentially reducing the need for multiple iterative cycles. This approach, accelerated by rapid cell-free testing, represents a future direction that could build upon the knowledge-driven methodology demonstrated in this case study [23].

FAQ 4: What are common reasons for low dopamine yield despite a functional pathway being present in E. coli? Low yield can stem from several factors:

- Precursor Limitation: Inadequate supply of the precursor L-tyrosine.

- Suboptimal Enzyme Ratios: Imbalanced expression of HpaBC and Ddc enzymes, leading to bottlenecks or intermediate accumulation.

- Cofactor Limitations: Insufficient supply of essential cofactors like FADH2 for the HpaBC enzyme [29].

- Product Degradation: Dopamine can be oxidized or degraded by host enzymes, such as tyramine oxidase (TynA) [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Biomass and Cell Growth After Genetic Modifications

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden | Measure growth rate and plasmid stability. | Use genomic integrations instead of multi-copy plasmids to stabilize the pathway [29]. |

| Toxic Intermediate Accumulation | Quantify L-DOPA levels in the medium; if high, it may indicate a downstream bottleneck. | Fine-tune the expression of ddc relative to hpaBC using RBS engineering to ensure efficient conversion of L-DOPA to dopamine [22]. |

| Disruption of Essential Pathways | Review engineered modifications (e.g., gene knockouts). | Ensure that knockouts (e.g., tynA) do not have unintended polar effects on essential genes. |

Issue 2: High L-DOPA Accumulation with Low Dopamine Conversion

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rate-Limiting Ddc Enzyme | Measure enzyme activity in cell lysates. | Screen for a more efficient Ddc variant (e.g., from Drosophila melanogaster) [29] or use directed evolution to improve the existing enzyme's activity. |

Weak RBS for ddc Gene |

Sequence the RBS region and measure relative protein levels of HpaBC and Ddc. | Employ high-throughput RBS library screening to find a stronger RBS sequence for the ddc gene to enhance its translation [22]. |

| Insufficient Cofactor (PLP) | Check culture medium for PLP (Vitamin B6) supplementation. | Ensure the medium is supplemented with 50 µM vitamin B6, an essential cofactor for Ddc [22]. |

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine Oxidation | Observe browning of the fermentation broth. | Implement a two-stage pH fermentation strategy and a combined feeding of Fe²⁺ and ascorbic acid to act as antioxidants and reduce product degradation [29]. |

| Insufficient Precursor Supply (L-tyrosine) | Quantify intracellular L-tyrosine levels. | Engineer the host strain for high L-tyrosine production by deleting transcriptional regulators (TyrR), using feedback-resistant enzymes (TyrAfbr), and knocking out competing pathways [30]. |

| Inefficient Cofactor Regeneration | Analyze metabolic flux. | Construct an FADH2-NADH supply module within the host to support the high energy demands of the HpaBC enzyme [29]. |

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

Table 1: Dopamine Production in EngineE. coliStrains: A Performance Comparison*

| Strain | Engineering Strategy | Dopamine Titer | Productivity | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge-Driven DBTL Strain | RBS fine-tuning based on in vitro lysate studies | 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L | 34.34 ± 0.59 mg/gbiomass | [22] |