AI-Driven DBTL Cycle: Accelerating Precision Biological Engineering and Drug Discovery

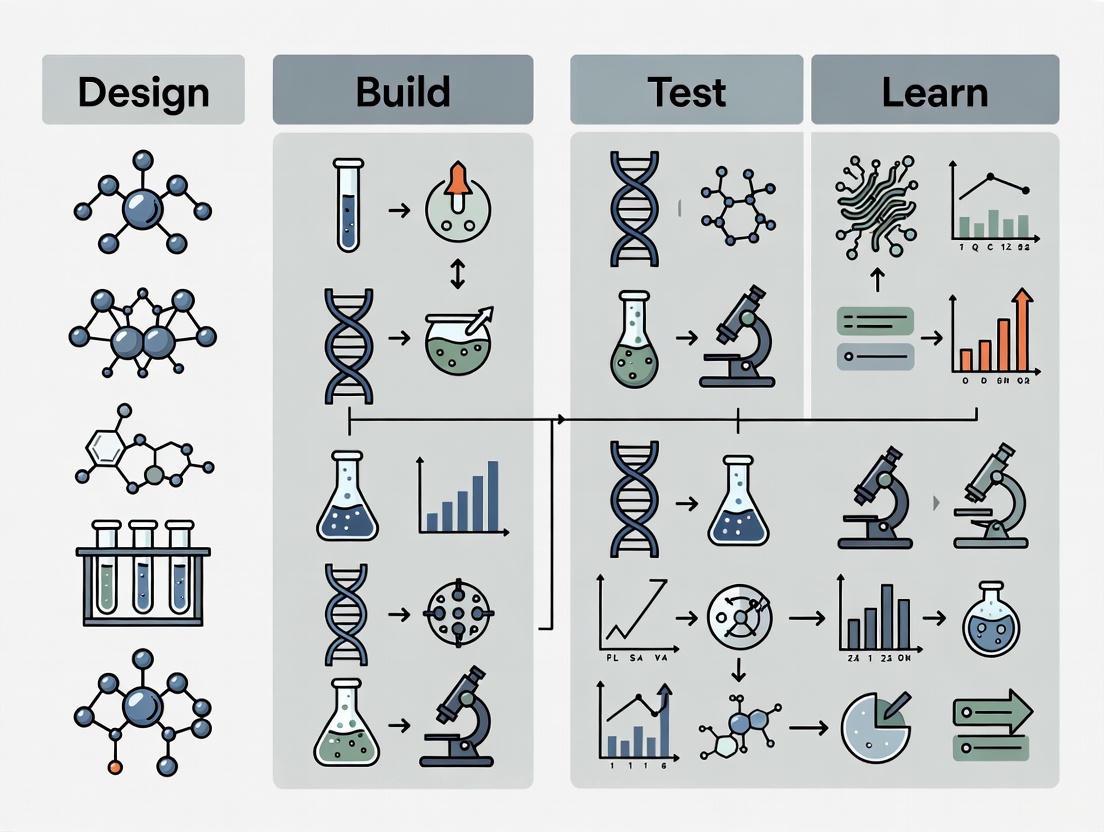

This article explores the transformative role of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle in modern biological engineering.

AI-Driven DBTL Cycle: Accelerating Precision Biological Engineering and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle in modern biological engineering. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it details how this iterative framework, supercharged by artificial intelligence and automation, is overcoming traditional R&D bottlenecks. We cover the foundational principles of DBTL, its methodological applications in strain engineering and cell therapy development, advanced strategies for optimizing its efficiency, and a comparative analysis of its validation in both industrial biomanufacturing and clinical research. The synthesis provides a roadmap for leveraging DBTL to achieve high-precision biological design and accelerate the development of next-generation therapeutics.

The DBTL Cycle: The Foundational Engine of Modern Synthetic Biology

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a systematic, iterative framework that serves as the cornerstone of modern synthetic biology and biological engineering. This engineering mantra provides a structured methodology for developing and optimizing biological systems, enabling researchers to engineer organisms for specific functions such as producing biofuels, pharmaceuticals, or other valuable compounds [1]. The cycle begins with researchers defining objectives for desired biological function and designing相应的 biological parts or systems, which can include introducing novel components or redesigning existing parts for new applications [2]. This foundational approach mirrors established engineering disciplines, where iteration involves gathering information, processing it, identifying design revisions, and implementing those changes [2].

The power of the DBTL framework lies in its recursive nature, which streamlines and simplifies efforts to build biological systems. Through repeated cycles, researchers can progressively refine their biological constructs until they achieve the desired performance or function [1]. This iterative process has become increasingly important as synthetic biology ambitions have grown more complex, evolving from simple genetic modifications to extensive pathway engineering and whole-genome editing. The framework's flexibility allows it to be applied across various biological systems, from bacterial chassis to eukaryotic cells, mammalian systems, and cell-free platforms [2].

The Core Components of the Traditional DBTL Cycle

Design Phase

The Design phase constitutes the foundational planning stage where researchers define specific objectives and create blueprints for biological systems. This phase relies heavily on domain knowledge, expertise, and computational modeling approaches [2]. During design, researchers select and arrange biological parts—such as promoters, coding sequences, and terminators—using principles of modularity and standardization that enable the assembly of diverse genetic constructs through interchangeable components [1]. The design process must account for numerous factors, including promoter strengths, ribosome binding site sequences, codon usage biases, and secondary structure propensities, all of which influence the eventual functionality of the engineered biological system [3]. Computational tools and bioinformatics resources play an increasingly vital role in this phase, allowing researchers to model and simulate system behavior before moving to physical implementation.

Build Phase

In the Build phase, digital designs transition into physical biological entities. This stage involves the synthesis of DNA constructs, their assembly into plasmids or other vectors, and introduction into characterization systems [2]. Traditional building methods include various molecular cloning techniques, such as restriction enzyme-based assembly, Gibson assembly, and Golden Gate assembly, each offering different advantages in terms of efficiency, fidelity, and scalability [1]. The Build phase has been significantly accelerated through automation, with robotic systems enabling the assembly of a greater variety of potential constructs by interchanging individual components [1]. More recently, innovative approaches like sequencing-free cloning that leverage Golden Gate Assembly with vectors containing "suicide genes" have achieved cloning accuracy of nearly 90%, eliminating the need for time-consuming colony picking and sequence verification [4]. Build outputs are typically verified using colony qPCR or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), though in high-throughput workflows, this verification step is sometimes optional to maximize efficiency [1].

Test Phase

The Test phase serves as the empirical validation stage where experimentally measured performance data is collected for the engineered biological constructs [2]. This phase determines the efficacy of decisions made during the Design and Build phases through various functional assays tailored to the specific application. Testing can include measurements of protein expression levels, enzymatic activity, metabolic flux, growth characteristics, or other relevant phenotypic readouts [1]. The emergence of high-throughput screening technologies has dramatically accelerated this phase, allowing researchers to evaluate thousands of variants in parallel rather than individually. Advanced platforms can now incorporate analytical techniques such as size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) that simultaneously provide data on multiple protein characteristics including purity, yield, oligomeric state, and dispersity [4]. The reliability and throughput of testing methodologies directly impact the quality and quantity of data available for the subsequent Learn phase, making this stage crucial for the overall efficiency of the DBTL cycle.

Learn Phase

The Learn phase represents the analytical component of the cycle, where data collected during testing is processed and interpreted to extract meaningful insights. This stage involves comparing experimental results against the objectives established during the Design phase, identifying patterns, correlations, and causal relationships between design features and functional outcomes [2]. The knowledge generated during this phase informs the next iteration of design, creating a continuous improvement loop. Traditional Learning approaches relied heavily on researcher intuition and statistical analysis, but increasingly incorporate sophisticated computational tools and machine learning algorithms to uncover complex relationships within high-dimensional datasets [3]. The effectiveness of the Learn phase depends critically on both the quality of experimental data and the analytical frameworks employed to interpret it, ultimately determining how rapidly the DBTL cycle converges on optimal solutions.

Table 1: Key Stages of the Traditional DBTL Cycle

| Phase | Primary Activities | Outputs | Common Tools & Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Define objectives; Select biological parts; Computational modeling | Genetic construct designs; Simulation predictions | CAD software; Bioinformatics databases; Metabolic models |

| Build | DNA synthesis; Vector assembly; Transformation | Physical DNA constructs; Engineered strains | Molecular cloning; DNA synthesis; Automated assembly; Sequencing |

| Test | Functional assays; Performance measurement; Data collection | Quantitative performance data; Expression levels; Activity metrics | HPLC; Spectroscopy; Chromatography; High-throughput screening |

| Learn | Data analysis; Pattern recognition; Hypothesis generation | Design rules; Predictive models; New research questions | Statistical analysis; Machine learning; Data visualization |

The Paradigm Shift: From DBTL to LDBT

The conventional DBTL cycle is undergoing a fundamental transformation driven by advances in machine learning and high-throughput experimental technologies. A groundbreaking paradigm shift, termed "LDBT" (Learn-Design-Build-Test), reorders the traditional cycle by placing Learning at the forefront [2] [3]. This approach leverages powerful machine learning models that interpret existing biological data to predict meaningful design parameters before any physical construction occurs [3]. The reordering addresses a critical limitation of the traditional DBTL cycle: the slow and resource-intensive nature of the Build-Test phases, which has historically created a bottleneck in biological design iterations [2].

The LDBT framework leverages the growing success of zero-shot predictions made by sophisticated AI models, where computational algorithms can generate functional biological designs without additional training or experimental data [2]. Protein language models—such as ESM and ProGen—trained on evolutionary relationships between millions of protein sequences have demonstrated remarkable capability in predicting beneficial mutations and inferring protein functions [2]. Similarly, structure-based deep learning tools like ProteinMPNN can design sequences that fold into specific backbone structures, leading to nearly a 10-fold increase in design success rates when combined with structure assessment tools like AlphaFold [2]. This paradigm shift brings synthetic biology closer to a "Design-Build-Work" model that relies on first principles, similar to disciplines like civil engineering, potentially reducing or eliminating the need for multiple iterative cycles [2].

Enabling Technologies Accelerating the Framework

Machine Learning and AI Integration

Machine learning has become a driving force in synthetic biology by enabling more efficient and scalable biological design. Unlike traditional biophysical models that are computationally expensive and limited in scope, machine learning methods can economically leverage large biological datasets to detect patterns in high-dimensional spaces [2]. Several specialized AI approaches have emerged for biological engineering:

Protein language models (e.g., ESM, ProGen) capture long-range evolutionary dependencies within amino acid sequences, enabling prediction of structure-function relationships [2]. These models have proven adept at zero-shot prediction of diverse antibody sequences and predicting solvent-exposed and charged amino acids [2].

Structure-based design tools (e.g., MutCompute, ProteinMPNN) use deep neural networks trained on protein structures to associate amino acids with their surrounding chemical environments, allowing prediction of stabilizing and functionally beneficial substitutions [2].

Functional prediction models focus on specific protein properties like thermostability and solubility. Tools such as Prethermut, Stability Oracle, and DeepSol predict effects of mutations on thermodynamic stability and solubility, helping researchers eliminate destabilizing mutations or identify stabilizing ones [2].

These machine learning approaches are increasingly being deployed in closed-loop design platforms where AI agents cycle through experiments autonomously, dramatically expanding capacity and reducing human intervention requirements [2].

Cell-Free Testing Platforms

Cell-free gene expression systems have emerged as a transformative technology for accelerating the Build and Test phases of the DBTL cycle. These platforms leverage protein biosynthesis machinery obtained from cell lysates or purified components to activate in vitro transcription and translation [2]. Their implementation offers several distinct advantages:

Exceptional speed: Cell-free systems can achieve protein production exceeding 1 g/L in less than 4 hours, dramatically faster than cellular expression systems [2].

Elimination of cloning steps: Synthesized DNA templates can be directly added to cell-free systems without intermediate, time-intensive cloning steps [2].

Tolerance to toxic products: Unlike living cells, cell-free systems enable production of proteins and pathways that would otherwise be toxic to host organisms [2].

Scalability and modularity: Reactions can be scaled from picoliters to kiloliters, and machinery can be obtained from organisms across the tree of life [2].

When combined with liquid handling robots and microfluidics, cell-free systems enable unprecedented throughput. For example, the DropAI platform leveraged droplet microfluidics and multi-channel fluorescent imaging to screen over 100,000 picoliter-scale reactions [2]. These capabilities make cell-free expression platforms particularly valuable for generating large-scale datasets needed to train machine learning models and validate computational predictions [2].

Automated Workflow Solutions

Automation technologies have become essential for implementing high-throughput DBTL cycles in practical research environments. Recent advancements focus on creating integrated systems that streamline the entire workflow from DNA to characterized protein:

The Semi-Automated Protein Production (SAPP) pipeline achieves a 48-hour turnaround from DNA to purified protein with only about six hours of hands-on time. This system uses miniaturized parallel processing in 96-well deep-well plates, auto-induction media, and two-step purification with parallel nickel-affinity and size-exclusion chromatography [4].

The DMX workflow addresses the DNA synthesis cost bottleneck by constructing sequence-verified clones from inexpensive oligo pools. This method uses an isothermal barcoding approach to tag gene variants within cell lysates, followed by long-read nanopore sequencing to link barcodes to full-length gene sequences, reducing per-design DNA construction costs by 5- to 8-fold [4].

Commercial systems like Nuclera's eProtein Discovery System unite design, expression, and purification in one connected workflow, enabling researchers to move from DNA to purified, soluble, and active protein in under 48 hours—a process that traditionally takes weeks [5].

These automated solutions share a common goal: replacing human variation with stable, reproducible systems that generate standardized, quantitative, high-quality experimental data at scales previously impractical [4] [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of DBTL-Enabling Technologies

| Technology | Throughput Capacity | Time Reduction | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Systems | >100,000 reactions via microfluidics [2] | Protein production in <4 hours vs. days/weeks [2] | >1 g/L protein yield; 48-hour DNA to protein [2] [5] |

| SAPP Workflow | 96 variants in one week [4] | 48-hour turnaround; 6 hours hands-on time [4] | ~90% cloning accuracy without sequencing [4] |

| DMX DNA Construction | 1,500 designs from single oligo pool [4] | 5-8 fold cost reduction [4] | 78% design recovery rate [4] |

| AI-Designed Proteins | 500,000+ computational surveys [2] | 10-fold increase in design success [2] | pM efficacy in neutralization assays [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

High-Throughput Protein Engineering Protocol

The integration of machine learning with rapid experimental validation has enabled sophisticated protein engineering workflows. The following protocol outlines a representative approach for high-throughput protein characterization:

Computational Design: Generate initial protein variants using structure-based deep learning tools (e.g., ProteinMPNN) or protein language models (e.g., ESM). For structural motifs, combine sequence design with structure assessment using AlphaFold or RoseTTAFold to prioritize designs with high predicted stability [2].

DNA Library Construction: Convert digital designs to physical DNA using cost-effective methods. For large libraries (>100 variants), employ oligo pooling and barcoding strategies (e.g., DMX workflow) to reduce synthesis costs. For smaller libraries, utilize automated Golden Gate Assembly with suicide gene-containing vectors for high-fidelity, sequence-verification-free cloning [4].

Cell-Free Expression: Transfer DNA templates directly to cell-free transcription-translation systems arranged in 96- or 384-well formats. Utilize auto-induction media to eliminate manual induction steps. Incubate for 4-16 hours depending on protein size and yield requirements [2] [3].

Parallel Purification and Analysis: Perform two-step purification using nickel-affinity chromatography followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) in deep-well plates. Use the SEC chromatograms to simultaneously assess protein purity, yield, oligomeric state, and dispersity [4].

Functional Characterization: Implement targeted assays based on protein function (e.g., fluorescence measurement, enzymatic activity, binding affinity). For high-throughput screening, leverage droplet microfluidics to analyze thousands of picoliter-scale reactions in parallel [2].

Data Integration and Model Retraining: Feed quantitative experimental results back into machine learning models to improve prediction accuracy for subsequent design rounds. Standardize data outputs using automated analysis tools to enable direct comparison between predicted and measured properties [4].

Case Study: AI-Driven Neutralizer Design

A compelling demonstration of the modern LDBT framework involved designing a potent neutralizer for Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) [4]. Researchers began with a known binding protein (cb13) and fused it to 27 different oligomeric scaffolds to create a library of 58 multivalent constructs. Using the SAPP platform, they rapidly identified 19 correctly assembled and well-expressed multimers. Subsequent viral neutralization assays revealed that the best-performing dimer and trimer achieved IC50 values of 40 pM and 59 pM, respectively—a dramatic improvement over the monomer (5.4 nM) that surpassed the efficacy of MPE8 (156 pM), a leading commercial antibody targeting the same site [4]. This success highlighted a critical insight: the geometry of multimerization is crucial for function, and only a high-throughput platform makes it feasible to screen the vast combinatorial space required to discover optimal configurations.

Case Study: Antimicrobial Peptide Discovery

Researchers have successfully paired deep-learning sequence generation with cell-free expression to computationally survey over 500,000 antimicrobial peptides (AMP) and select 500 optimal variants for experimental validation [2]. This approach led to the identification of six promising AMP designs, demonstrating the power of machine learning to navigate vast sequence spaces and identify functional candidates with minimal experimental effort [2]. The combination of computational prescreening and rapid cell-free testing enabled comprehensive exploration of a sequence space that would be prohibitively large for conventional approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free TX-TL Systems | Provides transcription-translation machinery for protein synthesis without whole cells [2] | Enables rapid testing of genetic constructs; compatible with various source organisms; scalable from µL to L [2] |

| Golden Gate Assembly Mix | Modular DNA assembly using Type IIS restriction enzymes [4] | Achieves ~90% cloning accuracy; enables sequencing-free cloning when combined with ccdB suicide gene vectors [4] |

| Oligo Pools | Cost-effective DNA library synthesis [4] | DMX workflow reduces cost 5-8 fold; enables construction of thousands of variants from single pool [4] |

| Auto-Induction Media | Automates protein expression induction [4] | Eliminates manual induction step in high-throughput workflows; compatible with deep-well plate formats [4] |

| Nickel-Affinity Resin | Purification of histidine-tagged proteins [4] | Compatible with miniaturized formats; first step in two-step purification process [4] |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Plates | High-throughput protein analysis and purification [4] | Simultaneously assesses purity, yield, oligomeric state, and dispersity [4] |

Workflow Visualization

LDBT Cycle: AI-First Biological Design

Cell-Free Protein Production Workflow

The DBTL framework continues to evolve from a conceptual model to an engineering reality that increasingly relies on the integration of computational and experimental technologies. The emergence of the LDBT paradigm represents a fundamental shift toward data-driven biological design, where machine learning models pre-optimize designs in silico before physical implementation [2] [3]. This approach is made possible by the growing success of zero-shot prediction methods and the availability of large biological datasets for training sophisticated AI models [2].

Looking forward, the convergence of several technological trends promises to further accelerate biological engineering. The integration of multi-omics datasets—transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—into the LDBT framework will enhance machine learning models' breadth and precision, capturing not only static sequence features but dynamic cellular contexts [3]. Advances in automation and microfluidics will continue to push throughput boundaries while reducing costs and hands-on time [2] [5]. Perhaps most significantly, the development of fully autonomous self-driving laboratories represents the ultimate expression of the DBTL cycle, where AI systems design, execute, and interpret experiments with minimal human intervention [4].

As these technologies mature, the DBTL framework will increasingly support a future where biological engineering becomes more predictable, scalable, and accessible. This progression promises to democratize synthetic biology research, enabling smaller labs and startups to participate in cutting-edge bioengineering without requiring extensive infrastructure [3]. By continuing to refine and implement the DBTL framework—in both its traditional and reimagined forms—the research community can accelerate the development of novel biologics, sustainable bioprocesses, and advanced biomaterials that address pressing challenges in healthcare, energy, and environmental sustainability.

The engineering of biological systems has undergone a fundamental transformation with the adoption of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, which has largely supplanted traditional linear development approaches. This iterative framework provides a systematic methodology for optimizing genetic constructs, metabolic pathways, and cellular functions through rapid experimentation and data-driven learning. By embracing DBTL cycles, synthetic biologists have dramatically accelerated the development of engineered biological systems for applications ranging from pharmaceutical production to sustainable manufacturing. This technical guide examines the core principles of the DBTL framework, its implementation across diverse synthetic biology applications, and the emerging technologies that are further enhancing its efficiency and predictive power.

Traditional linear approaches to biological engineering followed a sequential "design-build-test" pattern without structured iteration, making the process slow, inefficient, and often unreliable [6]. Each genetic design required complete development before testing, with no formal mechanism for incorporating insights from failures into improved designs. This limitation became particularly problematic in complex biological systems where unpredictable interactions between components frequently occurred.

The DBTL framework emerged as a solution to these challenges by introducing a structured, cyclical process for engineering biological systems [1]. This iterative approach enables synthetic biologists to systematically explore design spaces, test hypotheses, and incrementally improve system performance through successive cycles of refinement. The paradigm shift from linear to iterative development has fundamentally transformed synthetic biology, enabling more predictable engineering of biological systems and reducing development timelines from years to months in many applications.

The Core DBTL Cycle: Components and Implementation

Phase 1: Design

The Design phase involves creating genetic blueprints based on biological knowledge and engineering objectives. Researchers define specifications for desired biological functions and design genetic parts or systems accordingly, which may include introducing novel components or redesigning existing parts for new applications [2]. This phase relies on domain expertise, computational modeling, and increasingly on predictive algorithms.

Key Design Tools and Approaches:

- Retrosynthesis Software: Tools like RetroPath2.0 identify metabolic pathways linking target compounds to host metabolites [7]

- Standardized Biological Parts: Modular DNA components with characterized functions enable predictable system design

- Pathway Enumeration Algorithms: Computational methods generate multiple pathway alternatives for testing

- Machine Learning-Guided Design: Models trained on biological data predict part performance before physical construction [8]

Phase 2: Build

The Build phase translates digital designs into physical biological constructs. DNA sequences are synthesized or assembled into plasmids or other vectors, then introduced into host systems such as bacteria, yeast, or cell-free expression platforms [2]. Automation and standardization have dramatically increased the throughput and reliability of this phase.

Build Technologies and Methods:

- DNA Synthesis Services: Companies like Synbio Technologies and Twist Bioscience provide custom DNA library synthesis with high diversity (up to 10^10 variants) [6] [9]

- Automated Strain Engineering: Robotic systems enable high-throughput genetic modification

- Standardized Assembly Protocols: Methods like Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly, and Ligation Chain Reaction (LCR) enable modular construction [7]

- Cell-Free Systems: Cell-free gene expression using purified cellular machinery accelerates building and testing [2]

Phase 3: Test

The Test phase experimentally characterizes the performance of built constructs against design objectives. This involves measuring relevant phenotypic properties, production yields, functional activities, or other system behaviors using appropriate analytical methods [2] [1].

Testing Methodologies and Platforms:

- High-Throughput Screening: Automated systems rapidly assay thousands of variants

- Multi-Omics Analyses: Transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics provide comprehensive system characterization

- Cell-Free Testing: In vitro expression systems enable rapid functional analysis without cellular constraints [2]

- Analytical Chemistry: HPLC, MS, and fluorescence-based assays quantify product formation and kinetics

Phase 4: Learn

The Learn phase analyzes experimental data to extract insights that inform subsequent design cycles. Researchers identify patterns, correlations, and causal relationships between genetic designs and observed functions, creating knowledge that improves prediction accuracy in future iterations [1].

Learning Approaches:

- Statistical Analysis: Identifies significant correlations between design parameters and outcomes

- Machine Learning: Algorithms learn complex sequence-function relationships from experimental data [8]

- Mechanistic Modeling: Kinetic models interpret results based on biological principles [10]

- Pathway Analysis: Tools like rpThermo and rpFBA evaluate pathway performance based on thermodynamics and flux balance [7]

DBTL in Action: Experimental Applications and Protocols

Case Study 1: Optimizing Dopamine Production in E. coli

A knowledge-driven DBTL approach was applied to develop an efficient dopamine production strain in E. coli, resulting in a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over previous methods [11].

Experimental Protocol:

- Strain Engineering:

- Host strain E. coli FUS4.T2 was engineered for high L-tyrosine production by deleting the tyrosine repressor TyrR and mutating feedback inhibition in chorismate mutase/prephenate dehydrogenase (tyrA)

- Heterologous genes hpaBC (encoding 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase) and ddc (encoding L-DOPA decarboxylase) were introduced via pET plasmid system

In Vitro Pathway Testing:

- Cell-free protein synthesis systems using crude cell lysates tested different relative enzyme expression levels

- Reaction buffer contained 0.2 mM FeCl₂, 50 μM vitamin B₆, and 1 mM L-tyrosine or 5 mM L-DOPA in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7)

In Vivo Optimization:

- RBS engineering fine-tuned translation initiation rates for hpaBC and ddc genes

- 5 mL culture volumes in minimal medium (20 g/L glucose, 10% 2xTY, MOPS buffer) were used in high-throughput screening

- Dopamine production was quantified via HPLC analysis

Results and Iteration:

- Initial designs produced 27 mg/L dopamine

- After three DBTL cycles incorporating RBS optimization insights, production increased to 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L (34.34 ± 0.59 mg/g biomass)

Case Study 2: RNA Toehold Switch Optimization

The DBTL cycle was applied across 10 iterations to optimize RNA toehold switches for diagnostic applications, demonstrating rapid performance improvement through structured iteration [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Initial Design (Trial 1):

- Toehold switch designed to activate amilCP chromoprotein reporter upon target RNA binding

- DNA templates resuspended at 160 nM for consistent cell-free expression composition

Iterative Refinement (Trials 2-5):

- Trial 2: Replaced amilCP with GFP for improved kinetic measurements, revealing OFF-state leakiness

- Trial 3: Added upstream buffer sequences to stabilize the OFF state, reducing leak but limiting ON-state expression

- Trial 4: Reduced downstream guanine content to minimize ribosomal stalling

- Trial 5: Implemented superfolder GFP (sfGFP) for faster maturation and brighter signal

Validation (Trials 6-10):

- Conducted reproducibility testing across biological replicates

- Measured fluorescence kinetics and fold-activation ratios

- Final design achieved 2.0x fold-activation with high statistical significance (p = 1.43 × 10⁻¹¹¹)

Key Learning Outcomes:

- Reporter protein selection critically impacts measurement sensitivity

- Upstream sequences influence switch leakiness

- Downstream sequence composition affects translational efficiency

- sfGFP provides optimal balance of speed, brightness, and reliability for toehold switches

Quantitative Performance Comparison: DBTL vs. Linear Approaches

Table 1: Performance Metrics Comparing DBTL and Linear Development Approaches

| Development Metric | Traditional Linear Approach | DBTL Cycle Approach | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Timeline | 12-24 months | 3-6 months | 4x faster |

| Experimental Throughput | 10-100 variants/cycle | 1,000-100,000 variants/cycle | 100-1000x higher |

| Success Rate | 5-15% | 25-50% | 3-5x higher |

| Data Generation | Limited, unstructured | Comprehensive, structured | 10-100x more data |

| Resource Efficiency | High waste, repeated efforts | Optimized, iterative learning | 2-3x more efficient |

Table 2: DBTL Performance in Published Case Studies

| Application | Number of DBTL Cycles | Initial Performance | Final Performance | Key Optimized Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine Production [11] | 3 | 27 mg/L | 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L | RBS strength, enzyme expression ratio |

| Toehold Switches [12] | 10 | High leak, low activation | 2.0x fold activation, minimal leak | Reporter choice, UTR sequences |

| Lycopene Production [7] | 4 | 0.5 mg/g DCW | 15.2 mg/g DCW | Promoter strength, enzyme variants |

| PET Hydrolase [2] | 2 | Low stability | Increased stability & activity | Protein sequence, stabilizing mutations |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for DBTL Implementation

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Example Applications | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Library Synthesis Services | Generate variant libraries for screening | Protein engineering, pathway optimization | Twist Bioscience, GENEWIZ offer diversity up to 10^12 variants [13] [9] |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | Rapid in vitro testing of genetic designs | Protein production, circuit characterization | >1 g/L protein in <4 hours; pL to kL scalability [2] |

| Automated Strain Engineering Platforms | High-throughput genetic modification | Metabolic engineering, host optimization | Biofoundries enable construction of 1,000+ strains/week [7] |

| Analytical Screening Tools | Quantify strain performance | Metabolite production, growth assays | HPLC, MS, fluorescence enable high-throughput phenotyping [11] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Predictive design from experimental data | Protein engineering, pathway optimization | Gradient boosting, random forest effective in low-data regimes [10] [8] |

| Standardized Genetic Parts | Modular, characterized DNA elements | Genetic circuit design, metabolic pathway assembly | Registry of Standard Biological Parts enables predictable engineering |

Advanced DBTL: Integrating Machine Learning and Automation

The Rise of Machine Learning in DBTL Cycles

Machine learning (ML) has transformed the Learn and Design phases of DBTL cycles by enabling predictive modeling from complex biological data. ML algorithms can identify non-intuitive patterns in high-dimensional biological data, dramatically accelerating the design process [8].

Key ML Applications in DBTL:

- Protein Engineering: Models like ProteinMPNN and ESM predict protein structures and functions from sequences [2]

- Pathway Optimization: Gradient boosting and random forest models predict optimal enzyme expression levels and identify rate-limiting steps [10]

- Experimental Design: Active learning algorithms prioritize the most informative experiments for each cycle

- Automated Recommendation: Systems suggest improved designs based on previous cycle results [10]

The LDBT Paradigm Shift: Learning Before Design

A significant evolution in the DBTL framework is the emergence of the LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) paradigm, where machine learning precedes initial design [2]. This approach leverages pre-trained models on large biological datasets to make zero-shot predictions, potentially eliminating multiple DBTL cycles.

LDBT Enabling Technologies:

- Protein Language Models: ESM and ProGen capture evolutionary relationships to predict protein functions [2]

- Structure-Based Design: AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold enable structure-based protein engineering

- Foundational Models: Large-scale models trained on diverse biological data generalize across tasks

- Hybrid Modeling: Physics-informed machine learning combines statistical power with mechanistic principles [2]

Automated Workflow Platforms

Integrated platforms like Galaxy-SynBioCAD provide end-to-end workflow automation for DBTL implementation [7]. These systems connect pathway design, DNA assembly planning, and experimental execution through standardized data formats (SBML, SBOL) and automated liquid handling integration.

Visualization of DBTL Workflows and Relationships

The Core DBTL Cycle

Diagram 1: Core DBTL Cycle - The iterative engineering framework showing the four phases and their relationships.

The Emerging LDBT Paradigm

Diagram 2: LDBT Paradigm - The emerging framework where machine learning precedes design, potentially reducing iteration needs.

The DBTL cycle has fundamentally transformed synthetic biology by replacing inefficient linear development with a structured, iterative approach that embraces biological complexity. Through successive rounds of refinement, synthetic biologists can now engineer biological systems with unprecedented efficiency and predictability. The integration of machine learning, automation, and cell-free technologies continues to accelerate DBTL cycles, while the emerging LDBT paradigm promises to further reduce development timelines by leveraging predictive modeling before physical construction. As these methodologies mature, DBTL-based approaches will continue to drive innovations across biotechnology, from sustainable manufacturing to therapeutic development, solidifying their role as the cornerstone of modern biological engineering.

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle serves as the fundamental engineering framework in synthetic biology, providing a systematic and iterative methodology for developing and optimizing biological systems. This disciplined approach enables researchers to engineer microorganisms for specific functions, such as producing fine chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and biofuels [1]. The DBTL cycle's power lies in its iterative nature—complex biological engineering projects rarely succeed on the first attempt but instead make continuous progress through sequential cycles of refinement and improvement [14]. As the field advances, emerging technologies like machine learning and cell-free systems are reshaping the traditional DBTL paradigm, potentially reordering the cycle itself to accelerate biological design [2]. This technical guide examines the core components, interdependencies, and evolving methodologies of the DBTL framework within modern biological engineering research.

The DBTL Cycle: Core Components and Interdependencies

Design Phase

The Design phase initiates the DBTL cycle by establishing clear objectives and creating rational plans for biological system engineering. This stage relies on domain knowledge, expertise, and computational modeling tools to define specifications for genetic parts and systems [2]. Researchers design genetic constructs by selecting appropriate biological components such as promoters, ribosomal binding sites (RBS), and coding sequences, then assembling them into functional circuits or metabolic pathways using standardized methods [14].

Advanced biofoundries employ integrated software suites for automated pathway and enzyme selection. Tools like RetroPath and Selenzyme enable in silico selection of candidate enzymes and pathway designs, while PartsGenie facilitates the design of reusable DNA parts with simultaneous optimization of bespoke ribosome-binding sites and enzyme coding regions [15]. These components are combined into combinatorial libraries of pathway designs, which are statistically reduced using design of experiments (DoE) methodologies to create tractable numbers of samples for laboratory construction [15]. The transition from purely rational design to data-driven approaches represents a significant shift in synthetic biology, with machine learning models increasingly informing the design process based on prior knowledge [2].

Build Phase

The Build phase translates theoretical designs into physical biological reality through molecular biology techniques. This hands-on stage involves DNA synthesis, plasmid cloning, and transformation of engineered constructs into host organisms [14]. Automation has become crucial in this phase, with robotic platforms performing assembly techniques like ligase cycling reaction (LCR) to construct pathway variants [15].

High-throughput building processes enable the creation of diverse biological libraries. For example, in metabolic pathway optimization, researchers vary enzyme levels through promoter engineering or RBS modifications to create numerous strain designs [10]. After assembly, constructs undergo quality control through automated purification, restriction digest analysis via capillary electrophoresis, and sequence verification [15]. The modular nature of modern building approaches allows researchers to efficiently test multiple permutations by interchanging standardized biological components, significantly accelerating strain development [1].

Test Phase

The Test phase focuses on robust data collection through quantitative measurements of engineered system performance. Researchers employ various assays to characterize biological behavior, including measuring fluorescence to quantify gene expression, performing microscopy to observe cellular changes, and conducting biochemical assays to analyze metabolic pathway outputs [14].

Advanced testing methodologies incorporate high-throughput screening in multi-well plates combined with analytical techniques like ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) for precise quantification of target compounds and intermediates [15]. Testing also extends to bioprocess performance evaluation, where parameters such as biomass growth, substrate consumption, and product formation are monitored over time [10]. The emergence of cell-free expression systems has dramatically accelerated testing by enabling rapid in vitro protein synthesis and functional characterization without time-intensive cloning steps [2]. These systems leverage protein biosynthesis machinery from cell lysates for in vitro transcription and translation, allowing high-throughput sequence-to-function mapping of protein variants [2].

Learn Phase

The Learn phase represents the analytical core of the cycle, where experimental data transforms into actionable knowledge. Researchers analyze and interpret test results to determine whether designs functioned as expected and identify underlying principles governing system behavior [14]. This stage employs statistical methods and machine learning algorithms to identify relationships between design factors and observed performance metrics [15].

In metabolic engineering, the learning process often involves using kinetic modeling frameworks to understand pathway behavior and identify optimization targets [10]. The insights gained—whether from success or failure—directly inform the subsequent Design phase, leading to improved hypotheses and refined designs [14]. As machine learning advances, the learning phase has begun to shift earlier in the cycle, with some proposals suggesting an "LDBT" approach where learning precedes design through zero-shot predictions from pre-trained models [2].

Table 1: Key Tools and Technologies Enhancing DBTL Cycles

| DBTL Phase | Tools & Technologies | Applications | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | RetroPath, Selenzyme, PartsGenie, ProteinMPNN, ESM | Pathway design, enzyme selection, part optimization, protein engineering | Accelerates in silico design; enables zero-shot predictions |

| Build | Automated DNA assembly, ligase cycling reaction (LCR), robotic platforms | High-throughput construct assembly, library generation | Increases throughput; reduces manual labor and human error |

| Test | UPLC-MS/MS, cell-free systems, droplet microfluidics, fluorescent assays | Metabolite quantification, rapid prototyping, ultra-high-throughput screening | Enables megascale data generation; accelerates characterization |

| Learn | Machine learning (gradient boosting, random forest), kinetic modeling, statistical analysis | Data pattern recognition, predictive modeling, design recommendation | Identifies non-intuitive relationships; guides next-cycle designs |

Advanced Methodologies: Machine Learning and Automation

Machine learning has revolutionized the DBTL cycle by enabling data-driven biological design. Supervised learning models, particularly gradient boosting and random forest algorithms, have demonstrated strong performance in the low-data regimes common in biological engineering [10]. These models can predict strain performance based on genetic designs, allowing researchers to prioritize the most promising candidates for experimental testing.

Protein language models like ESM and ProGen, trained on evolutionary relationships between millions of protein sequences, enable zero-shot prediction of protein functions and beneficial mutations [2]. Structure-based deep learning tools such as ProteinMPNN facilitate protein design by predicting sequences that fold into desired backbone structures, achieving nearly 10-fold increases in design success rates when combined with structure assessment tools like AlphaFold [2]. These capabilities are transforming the DBTL paradigm from empirical iteration toward predictive engineering.

Automation represents another critical advancement, with biofoundries implementing end-to-end automated DBTL pipelines. These integrated systems handle pathway design, DNA assembly, strain construction, performance testing, and data analysis with minimal manual intervention [15]. The modular nature of these pipelines allows customization for different host organisms and target compounds while maintaining efficient workflow and iterative optimization capabilities.

Diagram 1: Traditional DBTL Cycle Workflow

Case Studies in Biological Engineering

Metabolic Pathway Optimization for Fine Chemical Production

An integrated DBTL pipeline successfully optimized (2S)-pinocembrin production in E. coli, achieving a 500-fold improvement through two iterative cycles [15]. The initial design created 2,592 possible pathway configurations through combinatorial variation of vector copy number, promoter strength, and gene order. Statistical reduction via design of experiments condensed this to 16 representative constructs. Testing revealed vector copy number as the most significant factor affecting production, followed by chalcone isomerase promoter strength. The learning phase informed a second design round focusing on high-copy-number vectors with optimized gene positioning, ultimately achieving competitive titers of 88 mg/L [15].

Development of Dopamine Production Strains

A knowledge-driven DBTL approach developed an efficient dopamine production strain in E. coli [11]. Researchers incorporated upstream in vitro investigation using cell-free protein synthesis systems to test different enzyme expression levels before DBTL cycling. This knowledge-informed design was then translated to an in vivo environment through high-throughput RBS engineering. The optimized strain achieved dopamine production of 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L (34.34 ± 0.59 mg/gbiomass), representing a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over previous state-of-the-art production systems [11].

Anti-adipogenic Protein Discovery

A systematic DBTL approach identified a novel anti-adipogenic protein from Lactobacillus rhamnosus [14]. The first cycle tested the hypothesis that direct bacterial contact inhibits adipogenesis by co-culturing six Lactobacillus strains with 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Results showed 20-30% inhibition of lipid accumulation, confirming anti-adipogenic effects. The second cycle investigated whether secreted extracellular substances mediated this effect by testing bacterial supernatants, revealing that only L. rhamnosus supernatant produced concentration-dependent inhibition (up to 45%). The third cycle isolated exosomes from supernatants, demonstrating that L. rhamnosus exosomes reduced lipid accumulation by 80% through regulation of PPARγ, C/EBPα, and AMPK pathways [14].

Table 2: Quantitative Results from DBTL Case Studies

| Case Study | Initial Performance | Optimized Performance | Key Optimization Factors | DBTL Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinocembrin Production [15] | 0.002 - 0.14 mg/L | 88 mg/L (500x improvement) | Vector copy number, CHI promoter strength | 2 |

| Dopamine Production [11] | Baseline (state-of-the-art) | 69.03 mg/L (2.6-6.6x improvement) | RBS engineering, GC content in SD sequence | Multiple with in vitro pre-screening |

| Anti-adipogenic Discovery [14] | 20-30% lipid reduction (raw bacteria) | 80% lipid reduction (exosomes) | Identification of active component, AMPK pathway regulation | 3 |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Cell-Free Protein Synthesis for Rapid Testing

Cell-free expression systems provide a powerful platform for rapid DBTL cycling [2]. These systems leverage protein biosynthesis machinery from crude cell lysates or purified components to activate in vitro transcription and translation. The standard protocol involves:

Lysate Preparation: Cultivate source organisms (e.g., E. coli), harvest cells during exponential growth, and lyse using French press or sonication. Clarify lysates by centrifugation.

Reaction Assembly: Combine DNA templates with cell-free reaction mixtures containing amino acids, energy sources (ATP, GTP), energy regeneration systems, and cofactors.

Protein Synthesis: Incubate reactions at 30-37°C for 4-6 hours, achieving protein yields exceeding 1 g/L [2].

Functional Analysis: Test synthesized proteins directly in coupled colorimetric or fluorescent-based assays for high-throughput sequence-to-function mapping.

This approach enables testing without molecular cloning or transformation steps, dramatically accelerating the Build-Test phases [2].

High-Throughput RBS Engineering

Ribosome Binding Site engineering enables precise fine-tuning of gene expression in synthetic pathways [11]. The methodology includes:

Library Design: Design RBS variants with modulated Shine-Dalgarno sequences while maintaining surrounding sequences to avoid secondary structure changes.

Library Construction: Assemble RBS variants via PCR-based methods or automated DNA assembly using robotic platforms.

Host Transformation: Introduce variant libraries into production hosts (e.g., E. coli FUS4.T2 for dopamine production).

Screening: Culture transformants in 96-deepwell plates with automated media handling and induction protocols.

Product Quantification: Analyze culture supernatants using UPLC-MS/MS for precise metabolite measurement.

Data Analysis: Correlate RBS sequences with production levels to identify optimal expression configurations.

Kinetic Modeling for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

Mechanistic kinetic models simulate metabolic pathway behavior to guide DBTL cycles [10]. The implementation involves:

Model Construction: Develop ordinary differential equations describing intracellular metabolite concentration changes, with reaction fluxes based on kinetic mechanisms derived from mass action principles.

Parameterization: Incorporate kinetic parameters from literature or experimental measurements, verifying physiological relevance through tools like ORACLE sampling.

Virtual Screening: Simulate pathway performance across combinatorial libraries of enzyme expression levels by adjusting Vmax parameters.

Machine Learning Integration: Use simulation data to train and benchmark machine learning models (e.g., gradient boosting, random forest) for predicting optimal pathway configurations.

Experimental Validation: Test model-predicted optimal designs and iteratively refine models based on experimental discrepancies.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DBTL Workflows

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Systems | In vitro transcription/translation | Rapid protein synthesis, pathway prototyping [2] |

| DNA Assembly Kits | Modular construction of genetic circuits | Golden Gate assembly, ligase cycling reaction [15] |

| RBS Libraries | Fine-tuning gene expression | Metabolic pathway optimization, enzyme balancing [11] |

| Promoter Collections | Transcriptional regulation | Combinatorial pathway optimization [10] |

| Analytical Standards | Metabolite quantification | UPLC-MS/MS calibration, product verification [15] |

| Specialized Media | Selective cultivation | High-throughput screening, production optimization [11] |

The Evolving DBTL Paradigm: LDBT and Future Directions

The traditional DBTL cycle is evolving toward an LDBT paradigm, where Learning precedes Design through machine learning [2]. This approach leverages pre-trained models on large biological datasets to make zero-shot predictions for biological design, potentially reducing or eliminating iterative cycling. Advances in protein language models (ESM, ProGen) and structure-based design tools (ProteinMPNN, MutCompute) enable increasingly accurate computational predictions of protein structure and function [2].

Cell-free platforms continue to accelerate Build-Test phases, with droplet microfluidics enabling screening of >100,000 reactions [2]. Integration of these technologies with automated biofoundries creates continuous DBTL pipelines that systematically address biological design challenges. As these capabilities mature, synthetic biology moves closer to a Design-Build-Work model based on first principles, similar to established engineering disciplines [2].

Diagram 2: Emerging LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test) Paradigm

The DBTL cycle remains the cornerstone methodology for synthetic biology and biological engineering, providing a disciplined framework for tackling biological design challenges. The interdependent phases create a powerful iterative process where each cycle builds upon knowledge gained from previous iterations. As machine learning, automation, and cell-free technologies continue to advance, the DBTL paradigm is evolving toward more predictive and efficient engineering approaches. For researchers in drug development and biological engineering, mastering DBTL principles and methodologies provides a critical foundation for success in developing novel biological solutions to complex challenges.

In the context of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for biological engineering research, the "Learn" phase represents a critical juncture where experimental data is transformed into actionable knowledge to inform the next cycle of design. This phase has historically constituted a significant bottleneck in research and drug development. The challenge has not been a scarcity of data; rather, it has been the computational and analytical struggle to extract meaningful, causal insights from the enormous volumes and complexity of biological and clinical data generated in the "Test" phase. The transition from high-throughput experimental data to reliable biological knowledge has been hampered by issues of data quality, integration, standardization, and the inherent limitations of analytical models, often causing costly delays and reducing the overall efficiency of the DBTL cycle [16] [4].

This article explores the historical and technical dimensions of this "Learn" bottleneck, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of the DBTL cycle's role in advancing biological engineering. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, overcoming this bottleneck is paramount to accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics, optimizing bioprocesses, and realizing the full potential of personalized medicine.

The Data Deluge in Biological Engineering

The "Test" phase of the DBTL cycle generates data at a scale that has overwhelmed traditional analytical approaches. The diversity and volume of this data are immense, originating from a wide array of high-throughput technologies.

Table 1: Common Types of Big Data in Biological Engineering

| Data Type | Description | Examples & Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data | Information about an organism's complete set of DNA, including genes and non-coding sequences. | European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) [17]; Genomic sequencing data from bacteriophage ϕX174 to the 160 billion base pairs of Tmesipteris oblanceolata [17]. |

| Clinical Trial Data | Structured and unstructured data collected during clinical trials to evaluate drug safety and efficacy. | Protocols, demographic data, outcomes, and adverse event reports [16]. |

| Real-World Evidence (RWE) | Data derived from real-world settings outside of traditional clinical trials. | Electronic Health Records (EHRs), claims data, wearables, and patient surveys [16] [18]. |

| Proteomic & Metabolomic Data | Data on the entire set of proteins (proteome) or small-molecule metabolites (metabolome) in a biological system. | Mass spectrometry data; multi-omics datasets for holistic biological analysis [16] [17]. |

| Pharmacovigilance Data | Data related to the detection, assessment, and prevention of adverse drug effects. | FDA's Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS), Vigibase, social media posts [16] [18]. |

| Imaging Data | Radiology scans and diagnostic imagery. | Data analyzed with AI for early detection and treatment optimization [16]. |

Table 2: Scale of Biological Data Repositories (Representative Examples)

| Repository/Database | Primary Content | Reported Scale |

|---|---|---|

| EMBL Data Resources | A collection of biological data resources. | Approximately 100 petabytes (10^15 bytes) of raw biological data across 54 resources [17]. |

| Database Commons | A curated catalog of biological databases. | 5,825 biological databases (as of 2023, increased 19.2% since) covering 1,728 species [17]. |

The sheer volume and heterogeneity of these datasets present the initial hurdle for the "Learn" phase. Integrating clinical trial results, genomic sequencing, EHRs, and post-market surveillance data requires extensive data mapping and harmonization to achieve a consistent and analyzable dataset [16]. Furthermore, the quality of the input data directly determines the reliability of the output knowledge. Duplicates, missing fields, and inconsistent units can severely distort analytical outcomes, making proactive validation pipelines and anomaly detection systems essential [16].

Historical & Technical Challenges in the 'Learn' Phase

The process of learning from big data is fraught with technical challenges that have historically slowed research progress. These challenges extend beyond simple data volume to the very structure, quality, and context of the data.

Data Integration and Standardization

A primary challenge is the fragmented nature of data sources. EHRs, laboratory instruments, and various 'omics platforms all produce data in different formats and structures (structured, semi-structured, and unstructured) [16]. Integrating these for a unified analysis is a non-trivial task that requires extensive computational and human resources. As noted in the context of pharmaceutical research, achieving interoperability between these disparate systems is a fundamental prerequisite for any meaningful learning [16].

Data Accuracy, Quality, and Context

The analytical outputs of the "Learn" phase are only as good as the input data. The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is acutely relevant here. Key issues include:

- Data Incompleteness: In EHRs, data can be missing due to patients transferring between healthcare systems or inconsistent documentation of over-the-counter medications [18].

- Reporting Bias: In spontaneous reporting systems like FAERS, reports are voluntary, which can lead to underreporting or overreporting of certain events based on factors like a drug's time on the market or media coverage [18].

- Loss of Context: The conversion of unstructured data (e.g., free-text physician notes) into structured data for analysis can lead to a loss of nuanced information [18].

Analytical and Interpretive Limitations

Even with clean, integrated data, the analytical methods themselves present challenges.

- Distinguishing Causation from Correlation: A significant challenge in data mining clinical records is distinguishing causal relationships from mere associations. For example, an analysis might find an association between a gadolinium-based contrast agent and myopathy. However, this is more likely because the agent was used to diagnose the condition, not cause it, highlighting the risk of misinterpretation without clinical expertise [18].

- The "Gold Standard" Problem: In drug-drug interaction (DDI) studies, it is notoriously difficult to define "true positive" and "true negative" interactions. The lack of a definitive standard resource for DDIs, combined with clinical prescribing biases that avoid known risky combinations, makes it hard to validate findings from data mining approaches [18].

- Model Precision and "Microbial Dark Matter": In environmental biotechnology, a vast proportion of genes identified in metagenomic datasets encode proteins of unknown function. This "microbial dark matter" limits our ability to reconstruct complete metabolic pathways, such as those for PFAS degradation, from omics data alone [17].

Case Studies & Experimental Protocols

The historical challenges of the "Learn" bottleneck can be clearly illustrated through specific experimental workflows in drug development and synthetic biology.

Case Study 1: Post-Marketing Drug Safety Surveillance

Objective: To identify novel drug-drug interactions (DDIs) leading to adverse drug events (ADEs) after a drug has been released to the market using large-scale healthcare data.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Gather data from sources such as:

- Spontaneous Reporting Systems (SRS): FDA's FAERS or WHO's Vigibase.

- Electronic Health Records (EHRs): Structured data (lab results, diagnosis codes) and unstructured data (clinical notes).

- Healthcare Claims Data: Structured data on pharmacy and medical claims [18].

- Data Preprocessing and Harmonization: Convert unstructured data to structured format using Natural Language Processing (NLP). Map different coding systems to a standard vocabulary. This step is where significant information loss can occur [18].

- Data Mining and Analysis: Apply statistical and machine learning algorithms (e.g., disproportionality analysis in SRS, regression models in EHRs) to detect signals of association between drug pairs and adverse events [18].

- Signal Validation and Triangulation:

- Clinical Expert Review: A clinician assesses the plausibility of the detected signal.

- Mechanistic Investigation: Conduct in vitro studies (e.g., cytochrome P450 inhibition assays) to explore a biological mechanism.

- Pathway Analysis: Integrate drug-gene interaction data to build drug-gene-drug networks that support the finding [18].

Historical Bottleneck: The "Learn" phase here is hampered by reporting biases, the difficulty of defining true negative DDIs, and the fundamental challenge of establishing causation from observational data. These limitations mean that findings are often hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive, requiring further costly and time-consuming experimental validation [18].

Case Study 2: High-Throughput Protein Engineering

Objective: To rapidly design, produce, and characterize thousands of protein variants and use the resulting data to improve AI models for the next design cycle—closing the DBTL loop.

Experimental Protocol (SAPP/DMX Platform): This protocol was developed to address the bottleneck that occurs when AI can design proteins faster than they can be physically tested [4].

- Design: AI models (e.g., RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN) generate digital blueprints for novel proteins.

- Build:

- DNA Construction (DMX Workflow): Use inexpensive oligo pools. Employ an isothermal barcoding method to tag each gene variant within a cell lysate. Use long-read nanopore sequencing to link each barcode to its full-length gene sequence. This reduces DNA synthesis costs by 5- to 8-fold [4].

- Cloning (SAPP Workflow): Use Golden Gate Assembly with a vector containing a "suicide gene" (ccdB) to achieve ~90% cloning accuracy, eliminating the need for sequencing [4].

- Protein Production (SAPP Workflow): Conduct expression and purification in 96-well deep-well plates using auto-induction media and a two-step parallel purification (nickel-affinity and size-exclusion chromatography).

- Test:

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): The SEC step simultaneously provides high-throughput data on protein purity, yield, oligomeric state, and dispersity for every variant [4].

- Functional Assays: Perform targeted assays (e.g., viral neutralization assays for therapeutics, fluorescence measurements for reporters).

- Learn:

- Automated Data Analysis: Use open-source software to automatically analyze thousands of SEC chromatograms, standardizing the output [4].

- Data Integration: The quantitative, high-quality data from the "Test" phase is aggregated into a structured dataset.

- Model Refinement: This dataset is fed back into the AI design models to improve their predictive accuracy for the next DBTL cycle, creating a "self-driving" laboratory for protein engineering [4].

Historical Bottleneck: Before such integrated platforms, the "Learn" phase was stymied by a lack of standardized, high-quality experimental data produced at a scale that matches AI's design capabilities. The SAPP/DMX platform directly confronts this by generating the robust, large-scale data required to effectively train and refine AI models [4].

Diagram 1: The DBTL cycle in biological engineering.

Diagram 2: An integrated computational-experimental workflow to overcome the 'Learn' bottleneck.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Data-Driven Biology

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Case Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo Pools | Large, complex mixtures of synthetic DNA oligonucleotides used for cost-effective gene library construction. | DMX workflow uses them to build thousands of gene variants, reducing DNA synthesis costs by 5-8 fold [4]. |

| Golden Gate Assembly | A modular, efficient DNA assembly method that uses Type IIS restriction enzymes. | Used in the SAPP workflow with a ccdB "suicide gene" vector for high-fidelity (~90%), sequencing-free cloning [4]. |

| Auto-induction Media | Culture media formulated to automatically induce protein expression when cells reach a specific growth phase. | Used in SAPP's miniaturized parallel processing in 96-well plates to eliminate the need for manual induction, saving hands-on time [4]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | A chromatography technique that separates molecules based on their size and shape. | In the SAPP platform, a parallelized SEC step provides simultaneous data on purity, yield, oligomeric state, and dispersity [4]. |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | A branch of AI that helps computers understand and interpret human language. | Used to analyze unstructured text from clinical notes, social media, and scientific literature for pharmacovigilance and DDI detection [16] [18]. |

| Spontaneous Reporting Systems (SRS) | Databases that collect voluntary reports of adverse drug events from healthcare professionals and patients. | Resources like FAERS and Vigibase are mined for signals of potential drug safety issues [18]. |

The "Learn" bottleneck has long been a formidable barrier in biological engineering, slowing the pace from discovery to application. Its roots lie in the multifaceted challenges of data integration, quality, and interpretation within the DBTL cycle. As the case studies in drug safety and protein engineering demonstrate, overcoming this bottleneck requires more than just advanced algorithms; it necessitates a holistic approach that includes the generation of standardized, high-quality experimental data at scale, the development of integrated computational-experimental platforms, and a critical, expert-driven interpretation of data-driven findings. The future of biological research hinges on continued innovation that tightens the DBTL loop, transforming the "Learn" phase from a historical impediment into a powerful engine for discovery.

From Code to Cell: Methodological Applications of DBTL in Strain and Therapy Development

High Throughput Screening (HTS) is a drug-discovery process widely used in the pharmaceutical industry that leverages specialized automation and robotics to quickly and economically assay the biological or biochemical activity of large collections of drug-like compounds [19]. This approach is particularly useful for discovering ligands for receptors, enzymes, ion-channels, or other pharmacological targets, and for pharmacologically profiling cellular or biochemical pathways of interest [19]. The core principle of HTS involves performing assays in "automation-friendly" microtiter plates with standardized formats such as 96, 384, or 1536 wells, enabling the rapid production of consistent, high-quality data while generating less waste due to smaller consumption of materials [19]. The integration of robotics and automation has transformed this field, allowing researchers to overcome previous limitations in manual handling techniques and significantly accelerating the pace of biological discovery and engineering.

Within the context of synthetic biology, HTS and laboratory robotics serve as critical enabling technologies for the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, a fundamental framework for systematically and iteratively developing and optimizing biological systems [1]. As synthetic biology has matured over the past two decades, the increased capacity for constructing biological systems has created unprecedented demands for testing capabilities that now exceed what manual techniques can deliver [20]. This surge has driven the establishment of biofoundries worldwide—specialized facilities where biological parts and systems can be built and tested rapidly through high-throughput automated assembly and screening methods [20]. These automated platforms leverage next-generation sequencing and mass spectrometry to collect large amounts of multi-omics data at the single-cell level, generating the extensive datasets necessary for advancing rational biological design [20].

The DBTL Cycle in Synthetic Biology

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a systematic framework employed in synthetic biology for engineering biological systems to perform specific functions, such as producing biofuels, pharmaceuticals, or other valuable compounds [1]. This iterative development pipeline begins with the rational design of biological components, followed by physical construction of these designs, rigorous testing of their functionality, and finally learning from the results to inform the next design iteration [20]. A hallmark of synthetic biology is the application of rational principles to design and assemble biological components into engineered pathways, though the complex nature of biological systems often makes it difficult to predict the impact of introducing foreign DNA into a cell [1]. This uncertainty creates the need to test multiple permutations to obtain desired outcomes, a process dramatically accelerated through automation.

The past decade has seen remarkable advancements in the "design" and "build" stages of the DBTL cycle, driven largely by massive improvements in DNA sequencing and synthesis technologies that have significantly reduced both cost and turnaround time [20]. While sequencing a human genome cost approximately $10 million in 2007, the price has dropped to around $600 today, enabling researchers to sequence whole genomes of organisms and amass vast genomic databases that form the foundation for re-designing biological systems [20]. Concurrently, easing DNA synthesis costs and novel DNA assembly methodologies like Gibson assembly have overcome limitations of conventional cloning methods, enabling seamless assembly of combinatorial genetic parts and even entire synthetic chromosomes [20]. These developments, coupled with advances in genetic toolkits and genome editing techniques, have expanded the arsenal of organisms that can serve as chassis for synthetic biology applications.

The Learning Bottleneck and Machine Learning

Despite significant progress in the "build" and "test" phases of the DBTL cycle, synthetic biologists have faced substantial challenges in the "learn" stage due to the complexity, heterogeneity, and interconnected nature of biological systems [20]. While researchers can generate enormous amounts of biological data through automated high-throughput methods, extracting meaningful insights from these datasets has proven difficult. Many synthetic biologists still resort to top-down approaches based on likelihoods and trial-and-error to determine optimum designs, deviating from the field's aspiration to rationally design organisms from characterized genetic parts [20].

Machine learning (ML) has recently emerged as a promising approach to overcome the "learning" bottleneck in the DBTL cycle [20]. ML processes large datasets and generates predictive models by selecting appropriate features to represent phenomena of interest and uncovering previously unseen patterns among them. The technique has already demonstrated success in improving biological components like promoters and enzymes at the individual part level [20]. To advance synthetic biology further, ML must facilitate system-level prediction of biological designs with desired characteristics by elucidating associations between phenotypes and various combinations of genetic parts and genotypes. As explainable ML advances, it promises to provide both predictions and rationale for proposed designs, deepening our understanding of biological relationships and accelerating the learning stage of the DBTL cycle [20].

Automation Technologies for High-Throughput Implementation

Robotic Platforms and Workcells

Modern implementation of high-throughput screening relies on sophisticated robotic platforms configured into integrated workcells. The Wertheim UF Scripps Institute's robotics laboratory exemplifies this approach, occupying 1452 ft² and sharing two Kalypsys-GNF robotic platforms between HTS and Compound Management functions [19]. Similarly, Ginkgo Bioworks has developed Reconfigurable Automation Carts (RACs) that can be rearranged and configured to meet the specific needs of each experiment [21]. These systems incorporate a robotic arm and magnetic track that move sample plates from one piece of equipment to another, with the entire system controlled by integrated software [21]. Jason Kelly, CEO of Ginkgo Bioworks, describes their approach as creating automated robots capable of performing major molecular biology lab operations in a semi-standardized way, analogous to how unit operations revolutionized chemical engineering [21].

Commercial solutions like the HighRes Biosolutions ELEMENTS Screening Work Cell are built around mobile Nucleus FlexCarts that enable vertical integration of multiple screening workflow devices [22]. These systems feature pre-configured devices and editable templates or user-scripted protocols for high-throughput automation and optimized cell-based screening [22]. A key advantage of these modular systems is their flexibility—devices can be rapidly added or removed from the work cell as experimental needs evolve, and individual components can be quickly moved offline for manual use and maintenance without disturbing overall automated workflows [22]. This modularity extends to device compatibility, with systems designed to accommodate a range of preferred devices from various manufacturers while maintaining optimal functionality within automated workflows.

Essential Hardware Components

Fully automated screening workcells incorporate a carefully curated selection of specialized devices that work in concert to execute complex experimental protocols. The following table summarizes core components typically found in these systems:

Table 1: Essential Components of Automated Screening Workcells

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Storage & Retrieval | AmbiStore D Random Access Sample Storage Carousel | Delivers and stores labware in as few as 12 seconds to enhance efficiency and throughput [22] |

| Liquid Handling | Agilent Bravo, Tecan Fluent, Hamilton Vantage, or Beckman Echo Automated Liquid Handler | Precisely dispenses liquids across microplate formats [22] |

| Plate Management | Two LidValet High-Speed Delidding Hotels | Rapidly removes, holds, and replaces most microplate lids while the robotic arm tends to other tasks [22] |

| Detection & Analysis | Microplate Reader | Measures biological or biochemical activity in well plates [22] |

| Sample Processing | Microplate Washer, Automated Plate Sealer, Automated Plate Peeler | Performs essential plate processing steps [22] |

| Incubation & Storage | Automated Incubator | Maintains optimal growth conditions for cell-based assays [22] |

| Mixing & Preparation | Shakers, MicroSpin Automated Centrifuge | Prepares samples for analysis [22] |

These integrated components enable complete walk-away automation for complex screening protocols. For instance, systems can be configured with template protocols for specific applications like Cell Titer-Glo assays (completing 40 plates in approximately 8 hours), IP-1 Gq assays (completing 80 assay-ready plates in approximately 8 hours), or Transcreener protocols (completing 30 plates in approximately 8 hours) [22]. Users can modify these existing templates or design completely new protocols from scratch, choosing from a wide variety of 96-, 384-, and 1536-well plate options to meet their specific research requirements [22].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Knowledge-Driven DBTL for Dopamine Production

A recent implementation of the automated DBTL cycle demonstrates its power for strain optimization in synthetic biology. Researchers developing an Escherichia coli strain for dopamine production employed a "knowledge-driven DBTL" approach that combined upstream in vitro investigation with high-throughput ribosome binding site (RBS) engineering [11]. This methodology enabled both mechanistic understanding and efficient DBTL cycling, resulting in a dopamine production strain capable of producing dopamine at concentrations of 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L (equivalent to 34.34 ± 0.59 mg/g biomass)—a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over state-of-the-art in vivo dopamine production [11].