A Comprehensive Guide to CRISPR Organoid Engineering: Protocols, Applications, and Troubleshooting

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement CRISPR-based genome editing in human organoid models.

A Comprehensive Guide to CRISPR Organoid Engineering: Protocols, Applications, and Troubleshooting

Abstract

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement CRISPR-based genome editing in human organoid models. It covers the foundational principles of why 3D organoids offer superior physiological relevance over traditional 2D cultures for functional genomics. The guide details step-by-step protocols for key techniques—including knockout, interference (CRISPRi), activation (CRISPRa), and knock-in—in various organoid systems like gastric, intestinal, and brain. A strong emphasis is placed on troubleshooting common challenges such as delivery efficiency and mosaicism. Finally, it explores validation strategies and comparative analyses that demonstrate the power of integrated CRISPR-organoid platforms for dissecting gene-drug interactions, modeling cancer, and advancing personalized medicine.

Why CRISPR-Engineered Organoids Are Revolutionizing Disease Modeling

For decades, two-dimensional (2D) cell culture has been the standard workhorse in biological research, enabling foundational discoveries in cell biology, drug development, and disease modeling. However, the inherent limitations of growing cells as flat monolayers on plastic surfaces have become increasingly apparent. These 2D models fail to capture the three-dimensional architectural complexity, cell-cell interactions, and physiological microenvironment of human tissues, leading to poor predictive value for human drug responses and disease mechanisms [1] [2].

The transition to three-dimensional (3D) organoids represents a paradigm shift in experimental biology. Organoids are self-organizing 3D structures derived from stem cells that recapitulate key aspects of native tissue architecture and function. Unlike 2D cultures, organoids preserve tissue-specific stem cell activity, enable multilineage differentiation, and maintain genomic alterations, histology, and pathology of primary tissues [3]. This technological advance has created unprecedented opportunities for studying human development, disease modeling, and drug discovery in systems that genuinely mirror human physiology.

The integration of CRISPR genome editing with 3D organoid models has particularly revolutionized functional genomics, enabling researchers to systematically dissect gene function and gene-drug interactions in physiologically relevant human systems [3] [4]. This combination represents a powerful toolkit for addressing fundamental biological questions and accelerating therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis: 2D vs. 3D Culture Systems

Table 1: Fundamental differences between 2D and 3D cell culture systems

| Feature | 2D Cell Culture | 3D Organoid Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Pattern | Single layer on flat surfaces [1] | Three-dimensional expansion in all directions [1] |

| Cell-ECM Interaction | Limited, unnatural adhesion [2] | Complex, physiologically relevant ECM interactions [1] |

| Cell-Cell Signaling | Primarily lateral connections | Natural 3D spatial organization and signaling gradients [1] |

| Gene Expression Profiles | Often aberrant due to artificial environment [1] | More in vivo-like gene expression patterns [1] |

| Drug Response Prediction | Often overestimates efficacy [1] | Better predicts in vivo drug responses, including resistance [1] |

| Tissue Architecture | Lacks structural complexity [2] | Mimics organ-specific microarchitecture [3] |

| Throughput & Cost | High-throughput, inexpensive [1] [2] | Medium throughput, higher cost [1] |

| Technical Ease | Simple handling, standardized protocols [1] | More complex culture requirements [5] |

Table 2: Functional outcomes in research applications

| Research Application | 2D Culture Performance | 3D Organoid Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Modeling | Poor representation of tumor microenvironment [1] | Recapitulates tumor heterogeneity and drug penetration gradients [1] |

| Drug Toxicity Screening | Limited predictive value for human toxicity [6] | Improved prediction of hepatotoxicity and cardiotoxicity [6] [7] |

| Stem Cell Differentiation | Limited differentiation potential | Enhanced differentiation and maturation [1] |

| Personalized Medicine | Limited clinical correlation | Strong correlation with patient drug responses in PDOs [6] |

| High-throughput Screening | Excellent for early-stage compound elimination [1] | Improving with automation and AI integration [8] |

| Gene Editing Efficiency | High efficiency for CRISPR manipulations [1] | More challenging but physiologically more relevant [3] |

The fundamental differences between these systems translate directly to research outcomes. A compelling example comes from cancer research, where 3D tumor organoids maintain the cellular heterogeneity and structural complexity of original tumors, enabling more accurate prediction of drug responses [6]. Similarly, in neurodegenerative disease modeling, 3D midbrain organoids recapitulate key pathological hallmarks of Parkinson's disease—including dopaminergic neuron loss and Lewy body-like formation—that cannot be adequately modeled in 2D systems [9].

CRISPR-Organoid Integration: Technical Protocols

The fusion of CRISPR technologies with 3D organoid cultures has created powerful experimental platforms for functional genomics. Below are detailed protocols for implementing CRISPR screening in gastric organoids, based on established methodologies [3].

Protocol: Large-Scale CRISPR Knockout Screening in Human Gastric Organoids

Principle: This protocol enables genome-wide identification of genes essential for cell growth and drug response using a pooled CRISPR knockout approach in primary human gastric organoids.

Materials & Reagents:

- TP53/APC double knockout (DKO) human gastric organoid line

- Lentiviral Cas9 expression vector

- Pooled lentiviral sgRNA library (e.g., 12,461 sgRNAs targeting 1093 membrane proteins + 750 non-targeting controls)

- Puromycin selection antibiotic

- Advanced DMEM/F12 culture medium

- Recombinant growth factors (EGF, Noggin, R-spondin)

- Matrigel or similar extracellular matrix

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Stable Cas9 Organoid Generation:

- Lentivirally transduce TP53/APC DKO gastric organoids with Cas9 expression vector.

- Select with appropriate antibiotics for 7-10 days until control cells are eliminated.

- Validate Cas9 activity using GFP reporter assay (should achieve >95% knockout efficiency).

Library Transduction:

- Dissociate organoids to single cells using enzyme-free dissociation buffer.

- Transduce Cas9-expressing organoids with pooled sgRNA lentiviral library at MOI of 0.3-0.5 to ensure majority receive single sgRNA.

- Maintain cellular coverage of >1000 cells per sgRNA throughout the experiment.

- Culture transduced organoids in complete growth medium for 48 hours.

Selection and Expansion:

- Initiate puromycin selection (2-5 μg/mL) 48 hours post-transduction.

- Continue selection for 5-7 days until non-transduced control organoids are eliminated.

- Harvest reference sample (T0) for genomic DNA extraction.

- Culture remaining organoids for 28 days, maintaining >1000x coverage.

Sample Processing and Sequencing:

- Harvest organoids at endpoint (T1) and extract genomic DNA.

- Amplify integrated sgRNA sequences using PCR with barcoded primers.

- Sequence amplified products using next-generation sequencing.

- Quantify sgRNA abundance by mapping sequences to reference library.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize read counts across samples.

- Calculate fold-change (T1/T0) for each sgRNA.

- Use statistical frameworks (e.g., MAGeCK) to identify significantly depleted or enriched sgRNAs.

- Gene-level scores are computed by aggregating signals from multiple sgRNAs per gene.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Low infection efficiency: Optimize viral titer and include polybrene (4-8 μg/mL).

- Poor organoid viability after transduction: Reduce centrifugation speed during infection.

- Library representation loss: Maintain minimum 1000x coverage throughout culture.

- High false-positive rates: Include sufficient non-targeting control sgRNAs and perform biological replicates.

Protocol: Inducible CRISPRi/a in Gastric Organoids

Principle: This protocol enables targeted gene repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) using doxycycline-inducible dCas9 systems for temporal control of gene expression.

Materials & Reagents:

- TP53/APC DKO gastric organoid line

- Lentiviral rtTA expression vector

- Doxycycline-inducible dCas9-KRAB (for CRISPRi) or dCas9-VPR (for CRISPRa) vectors

- Target-specific sgRNAs (e.g., CXCR4 or SOX2 promoters)

- Doxycycline (1 μg/mL working concentration)

- Flow cytometry antibodies for target validation

Procedure:

- Stable Cell Line Generation:

- Sequential lentiviral transduction: first introduce rtTA, then inducible dCas9 fusion.

- Sort mCherry-positive cells after 48 hours of doxycycline induction to establish stable pools.

- Confirm dCas9 expression by Western blot using anti-Cas9 antibodies.

Gene Expression Modulation:

- Design sgRNAs targeting promoter regions of genes of interest.

- Transduce stable inducible organoids with sgRNA vectors.

- Induce dCas9 activity with doxycycline (1 μg/mL) for 5-7 days.

- For temporal control, withdraw doxycycline to turn off system.

Validation and Phenotyping:

- Analyze target gene expression by qRT-PCR, flow cytometry, or immunostaining.

- For CXCR4 targeting, assess CXCR4-positive population by flow cytometry 5 days post-induction.

- Expected outcomes: CRISPRi should decrease CXCR4-positive population (e.g., from 13.1% to 3.3%), while CRISPRa should increase it (e.g., to 57.6%) [3].

- Monitor organoid growth and morphology for functional phenotypes.

Applications:

- Acute gene function loss without compensation

- Gene essentiality screens in specific contexts

- Modeling dosage-sensitive gene functions

- Dynamic studies of gene expression effects

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Dissecting Gene-Drug Interactions in Cancer

A landmark application of CRISPR-organoid technology demonstrated how large-scale screening in primary human 3D gastric organoids enables comprehensive dissection of gene-drug interactions [3]. Researchers performed multiple CRISPR modalities—including knockout, interference, activation, and single-cell approaches—to identify genes modulating sensitivity to cisplatin, a common chemotherapy drug.

The screens revealed unexpected connections, including a link between fucosylation pathways and cisplatin sensitivity, and identified TAF6L as a key regulator of cell recovery from cisplatin-induced damage. These findings were enabled by the physiological relevance of the 3D organoid model, which preserved the tissue architecture and cellular heterogeneity of gastric epithelium.

Key Experimental Insights:

- Pooled screens identified 68 significant dropout genes whose disruption caused growth defects

- Pathway enrichment revealed genes involved in transcription, RNA processing, and nucleic acid metabolism

- Tumor suppressor LRIG1 was identified as a top hit whose knockout enhanced proliferation

- Single-cell CRISPR screens resolved how genetic alterations interact with cisplatin at individual cell level

Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery

The application of 3D organoids extends beyond cancer to numerous disease areas. In neurodegenerative disease research, 3D midbrain organoids (MOs) have emerged as transformative tools for modeling Parkinson's disease (PD) [9]. These organoids recapitulate key pathological hallmarks including dopaminergic neuron loss and Lewy body formation, enabling mechanistic studies and drug screening.

Notable Advances:

- MOs with PD-linked mutations (LRRK2, GBA1, DNAJC6) model disease-specific phenotypes

- Optogenetics-assisted α-synuclein aggregation systems enable study of protein pathology

- High-throughput drug testing platforms identify potential neuroprotective compounds

- Successful integration and functional recovery demonstrated in animal PD models

The pharmaceutical industry is increasingly adopting organoid models for preclinical testing. Roche uses 3D tumor spheroids to model hypoxic tumor cores and test immunotherapies, while Memorial Sloan Kettering employs patient-derived organoids to match therapies to drug-resistant pancreatic cancer patients [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and solutions for CRISPR-organoid research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Systems | Cas9, dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi), dCas9-VPR (CRISPRa) [3] | Genome editing, gene repression, gene activation |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral sgRNA libraries, Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [10] | Efficient delivery of CRISPR components to organoids |

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, synthetic hydrogels, engineered scaffolds [6] [7] | 3D structural support mimicking native tissue microenvironment |

| Culture Media | Advanced DMEM/F12 with tissue-specific growth factors [3] | Support organoid growth and maintenance |

| Selection Agents | Puromycin, Geneticin (G418), Blasticidin | Selection of successfully transduced organoids |

| Induction Systems | Doxycycline-inducible cassettes, rtTA [3] | Temporal control of CRISPR activity |

| Analysis Tools | Single-cell RNA sequencing, HCS-3DX AI imaging [8] | High-content screening and analysis at single-cell resolution |

| Specialized Equipment | CERO 3D bioreactor, OrganoPlate, microfluidic chips [7] [5] | Scalable, reproducible organoid culture systems |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the considerable promise of CRISPR-engineered organoids, several challenges remain. Batch-to-batch variability, limited scalability, and incomplete microenvironmental complexity can undermine reliability and translational potential [6] [5]. The absence of vascularization in most current organoid models restricts nutrient delivery and organoid size, while the fetal phenotype of iPSC-derived organoids may limit their utility for modeling adult diseases [5].

The "Organoid Plus and Minus" framework has emerged as a strategic approach to address these limitations [6]. This integrated strategy combines technological augmentation ("Plus") with culture system refinement ("Minus") to improve screening accuracy, throughput, and physiological relevance.

Key Future Developments:

- Vascularization strategies: Co-culture with endothelial cells to create perfusable networks

- Immune system integration: Incorporation of microglia and other immune components

- Automation and AI: HCS-3DX and other automated systems for reproducible high-content screening [8]

- Organ-on-chip integration: Combining organoids with microfluidic platforms for enhanced physiological relevance [5]

- Multi-omics characterization: Comprehensive molecular profiling to validate model fidelity

The regulatory landscape is also evolving to accommodate these advanced models. The FDA's recent policy shift phasing out traditional animal testing in favor of human-relevant systems like organoids for drug safety evaluation signals growing acceptance of these technologies [6]. This regulatory transformation, combined with ongoing technical innovations, positions CRISPR-engineered organoids as cornerstone platforms for personalized drug discovery and therapeutic optimization in the coming years.

The convergence of CRISPR genome engineering with 3D organoid technology represents a transformative advance in biomedical research, enabling the creation of highly physiologically relevant human disease models. Organoids, which are three-dimensional in vitro cultures derived from adult stem cells (ASCs) or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), replicate the structural and functional complexity of native tissues [11]. When combined with the precision of CRISPR-based genetic perturbations, researchers can generate isogenic disease models to elucidate the functional impact of genetic variants in a human tissue context [12]. This powerful synergy allows for systematic dissection of gene function, drug mechanisms, and therapeutic vulnerabilities in human tissue environments that were previously inaccessible.

The expanding CRISPR toolkit now extends far beyond simple gene knockout, encompassing CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for transcriptional repression and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) for gene activation, in addition to base editing and prime editing technologies [3] [13]. These tools are revolutionizing functional genomics in organoid models, particularly through large-scale pooled screens that identify genes influencing disease processes and drug responses [3]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the current CRISPR toolkit for organoid engineering, with detailed protocols and experimental frameworks for implementing these technologies in a research setting.

The Expanded CRISPR Toolkit: Mechanisms and Applications

The CRISPR toolkit has evolved to encompass diverse functionalities for precise genetic manipulation, each with distinct mechanisms and applications in organoid research. The table below summarizes the key CRISPR technologies and their primary applications in organoid engineering.

Table 1: CRISPR Technologies and Their Applications in Organoid Research

| Technology | Cas Enzyme | Mechanism of Action | Primary Applications in Organoids | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Knockout | Cas9, Cas9 nickase | Creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) repaired by error-prone NHEJ | Generating loss-of-function mutations; creating isogenic disease models [12] | Permanent gene disruption; well-established protocols |

| CRISPRi | dCas9-KRAB fusion | Blocks transcription initiation/elongation without DNA cleavage [3] | Reversible gene silencing; studying essential genes [3] | No DNA damage; tunable repression; fewer off-target effects |

| CRISPRa | dCas9-VPR fusion | Recruits transcriptional activators to gene promoters [3] | Gene activation; studying gene dosage effects | Precise transcriptional activation without DSBs |

| Base Editing | Base editor (dCas9 or Cas9 nickase fused to deaminase) | Directly converts one DNA base to another without DSBs [13] | Introducing point mutations; disease modeling | High efficiency; minimal indel formation |

| Prime Editing | Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion | Uses pegRNA to directly copy edited sequence into genome [13] | Precise insertions, deletions, and point mutations | Versatile; no DSBs; wider editing window than base editors |

Experimental Workflow for CRISPR Screening in Organoids

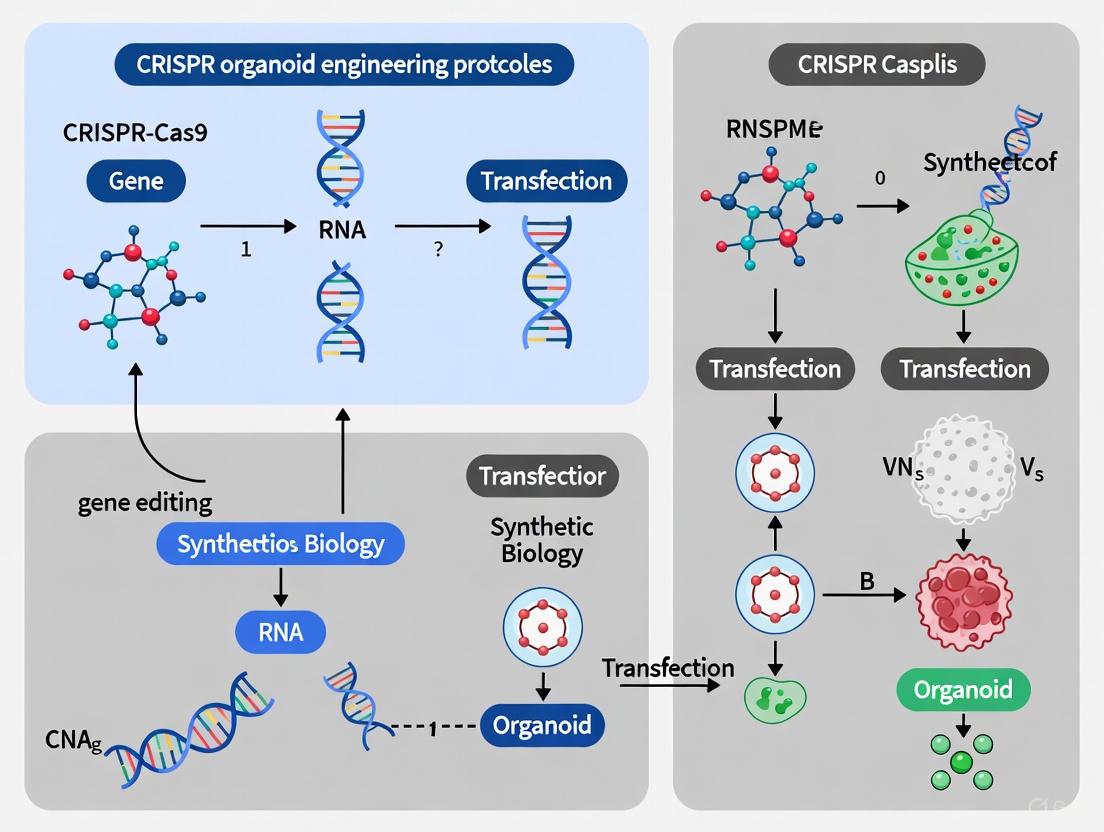

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for conducting CRISPR screens in organoid models, from establishment to hit validation:

Figure 1: Generalized workflow for CRISPR screening in organoid models, adapted from large-scale screening approaches [3] [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating Isogenic Disease Models in Organoids Using Base and Prime Editors

This protocol describes the creation of precise genetic variants in organoids using next-generation CRISPR tools that avoid double-strand breaks, enabling modeling of genetic diseases with higher efficiency and reduced cellular toxicity [12].

sgRNA Design and Cloning

- Design sgRNAs targeting the genomic region of interest using computational tools, considering the editing window of base editors (typically 4-8 nucleotides upstream of PAM for cytosine base editors and 5-10 nucleotides for adenine base editors) or the positioning requirements for prime editing guide RNAs (pegRNAs) [13].

- For base editing: Select sgRNAs with the target base within the optimal activity window for the specific base editor being used.

- For prime editing: Design pegRNAs with reverse transcriptase templates encoding the desired edit and appropriate primer binding sites.

- Clone sgRNAs into appropriate expression vectors using restriction-ligation cloning or Golden Gate assembly. For pooled screens, clone sgRNA libraries into lentiviral vectors with appropriate selection markers.

Electroporation-based Transfection

- Culture organoids to 60-80% confluence in Matrigel or similar extracellular matrix.

- Dissociate organoids into single cells using enzyme-free dissociation reagents or gentle enzymatic digestion.

- Prepare electroporation mixture containing:

- 1-5 µg base editor or prime editor mRNA/protein

- 500 ng-1 µg sgRNA expression plasmid or synthetic sgRNA

- 1-2 million dissociated organoid cells in electroporation buffer

- Electroporate using optimized parameters for your organoid type (typical conditions: 1200-1500 V, 20 ms pulse width for 2-3 pulses).

- Plate transfected cells in fresh Matrigel with organoid culture medium and allow to recover for 48 hours.

Selection and Clonal Expansion

- Initiate antibiotic selection 72 hours post-transfection if using plasmid-based systems with selection markers (e.g., puromycin at 1-5 µg/mL for 5-7 days).

- For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), use co-expressed fluorescent markers (e.g., GFP) to isolate successfully transfected cells 96 hours post-transfection.

- Plate sorted/selected cells at clonal density (500-1000 cells per well in 96-well plates) in Matrigel with organoid growth medium.

- Expand individual clones for 2-3 weeks, refreshing medium every 2-3 days.

Validation of Genome Editing

- Extract genomic DNA from expanded clonal organoid lines using standard protocols.

- Amplify target region by PCR using flanking primers.

- Validate edits by Sanger sequencing and tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE) analysis for base editors or specific allele-PCR for prime editors.

- For comprehensive characterization, perform additional validation such as:

- Western blotting to confirm protein-level changes

- RT-qPCR to assess transcriptional effects

- Functional assays relevant to the specific genetic variant

Protocol 2: Establishing Inducible CRISPRi and CRISPRa Systems in Gastric Organoids

This protocol details the implementation of inducible CRISPR interference and activation systems in human gastric organoids, enabling temporal control of gene expression for studying dynamic biological processes [3].

Generation of Stable dCas9-Expressing Organoid Lines

- Engineer TP53/APC double knockout (DKO) gastric organoid line to provide a homogeneous genetic background with minimal variability [3].

- Generate organoid lines expressing rtTA using lentiviral transduction followed by antibiotic selection.

- Introduce doxycycline-inducible dCas9 fusion protein:

- For CRISPRi: dCas9-KRAB (transcriptional repressor)

- For CRISPRa: dCas9-VPR (VP64-p65-Rta transcriptional activator)

- Transduce with lentiviral vectors containing the inducible dCas9 cassette and mCherry reporter.

- Sort mCherry-positive cells by FACS after doxycycline induction (1 µg/mL for 72 hours) to establish stable iCRISPRi and iCRISPRa organoid lines.

- Confirm expression of dCas9-KRAB or dCas9-VPR by Western blotting using anti-Cas9 antibodies.

Testing System Functionality

- Design sgRNAs targeting gene promoters of control genes (e.g., CXCR4, SOX2) with known expression patterns in gastric organoids.

- Transduce stable dCas9 organoid lines with lentiviral sgRNA vectors.

- Induce dCas9 expression with doxycycline (1 µg/mL) for 5-7 days.

- Analyze gene expression changes:

- For surface markers like CXCR4: Use antibody staining and flow cytometry

- For intracellular proteins: Perform immunofluorescence or Western blotting

- For transcript levels: Conduct RT-qPCR or RNA-seq

- Expected outcomes: iCRISPRi-sgCXCR4 organoids should show decreased CXCR4-positive population (e.g., from 13.1% to 3.3%), while iCRISPRa-sgCXCR4 should show increased positive population (e.g., to 57.6%) [3].

Protocol 3: Large-Scale Pooled CRISPR Screening in 3D Gastric Organoids

This protocol enables genome-wide functional genetic screens in organoids to identify genes involved in specific biological processes or drug responses, as demonstrated in gastric cancer organoids treated with cisplatin [3].

Screening Setup and Library Delivery

- Select appropriate CRISPR library based on screening goal:

- Knockout: Cas9-based sgRNA library

- CRISPRi: dCas9-KRAB-compatible sgRNA library targeting promoters

- CRISPRa: dCas9-VPR-compatible sgRNA library targeting promoters

- Validate Cas9 activity in organoid line using GFP reporter assay (≥95% GFP-negative cells indicates robust Cas9 activity) [3].

- Transduce organoids with pooled lentiviral library at low MOI (MOI=0.3-0.5) to ensure most cells receive single sgRNA.

- Maintain cellular coverage of >1000 cells per sgRNA throughout the screening process to maintain library representation.

- Harvest reference sample 2 days post-puromycin selection (T0) for baseline sgRNA distribution.

Selection and Phenotypic Interrogation

- Apply selective pressure relevant to biological question:

- For gene-drug interaction studies: Add drug (e.g., cisplatin for gastric cancer screens) at appropriate concentration

- For essential gene identification: Culture without selective pressure and identify dropout sgRNAs

- For fitness genes: Monitor growth over 2-4 weeks

- Maintain consistent cellular coverage (>1000 cells per sgRNA) throughout selection period.

- Harvest endpoint sample (T1) after 14-28 days of selection, depending on experimental design.

Sequencing and Hit Identification

- Extract genomic DNA from T0 and T1 samples using scalable methods.

- Amplify sgRNA regions by PCR with barcoded primers for multiplexing.

- Sequence amplified libraries using next-generation sequencing (Illumina platforms).

- Quantify sgRNA abundance by counting reads mapping to each sgRNA in the library.

- Calculate phenotype scores for each gene by comparing sgRNA abundance between T0 and T1 samples, normalized to control sgRNAs.

- Identify significant hits using statistical frameworks (e.g., MAGeCK, RSA) with thresholds for significance (e.g., FDR < 0.05).

Essential Controls and Validation Strategies

Proper experimental controls are critical for interpreting CRISPR screening results and validating candidate hits. The table below outlines essential controls for different types of CRISPR experiments in organoids.

Table 2: Essential Controls for CRISPR Experiments in Organoids

| Control Type | Composition | Purpose | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfection Control | Fluorescent reporter (GFP mRNA/plasmid) | Assess delivery efficiency | Visual confirmation of successful transfection |

| Positive Editing Control | Validated sgRNA with known high efficiency (e.g., targeting TRAC, RELA) [14] | Verify editing capability under optimized conditions | High editing efficiency in target gene |

| Negative Editing Control (Scramble) | Scramble sgRNA + Cas nuclease [14] | Establish baseline for non-specific effects | No specific editing; phenotype similar to wildtype |

| Negative Editing Control (Guide Only) | sgRNA without Cas nuclease [14] | Control for sgRNA-specific off-target effects | No editing; identifies sgRNA toxicity |

| Negative Editing Control (Cas Only) | Cas nuclease without sgRNA [14] | Control for Cas nuclease toxicity | No specific editing; identifies Cas toxicity |

| Mock Control | Cells undergoing transfection with no nucleases or guides [14] | Control for transfection stress | Phenotype similar to wildtype |

Hit Validation Strategies

- Individual sgRNA validation: Test 2-3 independent sgRNAs targeting significant hit genes in arrayed format to confirm phenotype reproducibility [3].

- Rescue experiments: For CRISPRi/CRISPRa hits, demonstrate that phenotype is reversible by withdrawing doxycycline to turn off dCas9 activity.

- Multi-modal validation: Combine complementary approaches (e.g., CRISPR knockout with RNAi) to confirm phenotype is not technology-specific.

- Functional assays: Perform pathway-specific functional assays relevant to the screened phenotype (e.g., DNA repair assays for cisplatin sensitivity hits).

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of CRISPR tools in organoid research requires carefully selected reagents and delivery systems. The following table outlines key solutions for establishing CRISPR-organoid workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Organoid Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Cas9, Base editors, Prime editors, dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-VPR | Genome editing, transcriptional regulation | Select based on desired genetic manipulation (see Table 1) |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral vectors, Electroporation systems, Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) | Deliver CRISPR components into cells | Lentiviruses for stable integration; electroporation for transient expression [12] |

| Organoid Culture Matrix | Matrigel, Synthetic hydrogels | Provide 3D extracellular environment for organoid growth | Matrigel is most common; synthetic alternatives improve reproducibility |

| Selection Markers | Puromycin, Blasticidin, Fluorescent proteins (GFP, mCherry) | Enumerate and select successfully transfected cells | Antibiotic resistance for stable lines; fluorescent markers for FACS |

| sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide knockout, CRISPRi, CRISPRa libraries | Enable large-scale genetic screens | Ensure high coverage (>1000 cells/sgRNA) and library representation [3] |

| Validation Tools | Sanger sequencing, Next-generation sequencing, ICE analysis | Verify editing efficiency and specificity | ICE analysis for quantifying editing efficiency from Sanger data [14] |

The integration of advanced CRISPR technologies with 3D organoid models has created a powerful platform for human disease modeling and functional genomics. The protocols and frameworks presented here provide researchers with comprehensive guidance for implementing these tools, from generating precise isogenic models to conducting genome-wide screens. As both technologies continue to evolve, their combination will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into human biology and disease mechanisms, accelerating the development of novel therapeutic strategies. The key to success lies in careful experimental design, appropriate control selection, and rigorous validation of genetic perturbations and their phenotypic consequences.

Organoid biobanks represent a transformative resource in biomedical research, enabling the study of human development, disease modeling, and high-throughput drug screening. The fundamental choice researchers face is between patient-derived organoid (PDO) biobanks, which preserve native human genetic and phenotypic diversity, and engineered organoid biobanks, which offer defined genetic backgrounds and tailored modifications for specific research questions [15] [16]. Patient-derived organoids are three-dimensional (3D) cell culture systems derived directly from patient tumor tissue that retain the genetic variability and phenotypic diversity of the primary tumor, effectively recapitulating the structural, functional, and heterogeneous characteristics of original tissues [15]. In contrast, engineered organoid biobanks utilize genetic engineering tools like CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce specific mutations into pluripotent or adult stem cells, generating genetically defined models for systematic investigation of gene function and disease mechanisms [17] [16]. This Application Note provides a structured comparison of these complementary approaches and detailed protocols for their establishment and application within CRISPR organoid engineering research.

Comparative Analysis: PDO vs. Engineered Organoid Biobanks

The selection between patient-derived and engineered organoid models should be guided by research objectives, required throughput, and available resources. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations, which are summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Patient-Derived vs. Engineered Organoid Biobanks

| Characteristic | Patient-Derived Organoid (PDO) Biobanks | Engineered Organoid Biobanks |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Background | Native patient genetics; preserves tumor heterogeneity [15] | Defined genetic background; enables isogenic controls [17] |

| Primary Applications | Drug screening, personalized medicine, studying tumor heterogeneity [15] | Functional genomics, disease mechanism studies, gene function validation [17] [16] |

| Development Timeline | 2-3 weeks for establishment [15] | 2-4 months including genetic engineering [18] |

| Throughput Potential | Medium; limited by patient sample availability | High; scalable from single stem cell lines |

| Technical Complexity | Medium; requires optimization of culture conditions [15] | High; requires expertise in genetic engineering [17] |

| Representative Examples | Colorectal, pancreatic, breast cancer PDOs [15] | CRISPR-engineered fetal brain organoids, intestinal organoid knockout biobanks [18] [17] |

Establishment Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Patient-Derived Organoid Biobank Development

Principle: Generate organoids directly from patient tissue samples while preserving original tissue architecture and genetic heterogeneity.

Workflow:

- Tissue Collection and Processing: Obtain fresh tumor tissue via biopsy or surgical resection. Mechanically dissociate and enzymatically digest tissue into small fragments or single cells [15].

- Extracellular Matrix Embedding: Suspend tissue fragments in Basement Membrane Extract (e.g., Matrigel) and plate as domes. Polymerize at 37°C for 30-60 minutes [15].

- Organoid Culture Medium: Overlay with defined medium containing:

- Essential growth factors (EGF, Noggin, R-spondin)

- Tissue-specific patterning factors

- Wnt pathway agonists for stem cell maintenance

- Antibiotic/Antimycotic solution [15]

- Expansion and Biobanking: Culture at 37°C with 5% CO₂, passaging every 1-2 weeks via mechanical disruption and re-embedding. Cryopreserve in freezing medium containing 10% DMSO and serum alternatives [15].

Quality Control: Validate organoids through genomic sequencing, histology, and immunostaining to confirm retention of original tissue characteristics [19].

Protocol for CRISPR-Engineered Organoid Biobank Development

Principle: Introduce specific genetic modifications into stem cell-derived organoids using CRISPR-Cas9 technology for controlled functional studies.

Workflow:

- Stem Cell Culture: Maintain human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) or adult stem cells in feeder-free conditions with daily medium changes [18].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Design: Design and validate sgRNAs targeting genes of interest. Select Cas9 system (wild-type, nickase, or dead Cas9) based on desired edit type [17].

- Delivery and Transfection: Deliver CRISPR components via electroporation or lipofection. Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate successfully transfected cells based on reporter expression (e.g., EGFP) [17].

- Clonal Selection and Expansion: Plate single cells and expand into clonal organoid lines. Screen for desired mutations via sequencing and functional assays [17].

- Biobank Curation: Cryopreserve validated clones with detailed genetic characterization. Establish 2-6 mutated clonal lines per target gene to account for potential clonal variation [17].

Validation: Confirm genetic modifications through Sanger sequencing, functional assays, and western blotting. Verify absence of off-target effects through whole-genome sequencing where necessary [17].

Figure 1: CRISPR-engineered organoid biobank development workflow.

Integrated Research Applications

Functional Genomics through CRISPR Screening in PDOs

Principle: Combine the genetic diversity of PDOs with systematic CRISPR screening to identify patient-specific genetic vulnerabilities and therapeutic targets [15].

Workflow:

- Library Design: Select CRISPR knockout, activation, or base-editing libraries targeting genes of interest (e.g., cancer driver genes, drug targets).

- Viral Transduction: Package sgRNA library into lentiviral vectors. Transduce PDO cultures at low MOI to ensure single integration events.

- Selection and Expansion: Apply selection pressure (e.g., antibiotics, drug treatment) and expand organoids for 2-3 weeks.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Harvest organoids, extract gDNA, amplify integrated sgRNAs, and sequence via next-generation sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify enriched or depleted sgRNAs using specialized algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK, BAGEL) to reveal essential genes under experimental conditions [15].

Application Example: CRISPR screens in colorectal cancer PDOs have identified novel genetic dependencies and mechanisms of resistance to targeted therapies, highlighting pathways not revealed in conventional 2D models [15].

Tumor Microenvironment and Immunotherapy Modeling

Principle: Engineer PDOs to include stromal and immune components for studying tumor-immune interactions and immunotherapy responses.

Workflow:

- Stromal Co-culture: Isolate cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) from patient tissue and co-culture with matched PDOs in 3D matrices.

- Immune Cell Integration: Expand autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) or engineer immune cells (e.g., CAR-T cells) for incorporation into PDO cultures.

- Treatment and Monitoring: Treat co-cultures with immunotherapeutic agents (e.g., immune checkpoint inhibitors) and monitor tumor cell killing via live-cell imaging [15].

- Analysis: Quantify immune cell-mediated organoid killing, cytokine production, and changes in immune cell phenotypes [15].

Figure 2: Tumor microenvironment modeling with PDO co-cultures.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Organoid Biobanking

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Matrigel, Basement Membrane Extract | Provide 3D scaffold for organoid growth and polarization [15] |

| Growth Factors | EGF, Noggin, R-spondin, Wnt-3a | Maintain stemness and support tissue-specific differentiation [15] |

| CRISPR Components | Cas9 nucleases, sgRNA libraries, HDR templates | Enable precise genetic editing for engineered biobanks [17] |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, electroporation systems | Facilitate efficient introduction of genetic elements [17] |

| Cell Culture Supplements | B-27, N-2, N-acetylcysteine | Support organoid growth and viability in defined media [15] |

| Analysis Tools | CrisprVi software, single-cell RNA seq | Enable visualization and analysis of CRISPR and sequencing data [20] |

Analytical Methods and Data Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis of Organoid Drug Responses

Principle: Employ high-content imaging and computational analysis to quantify organoid-level and cell-level responses to therapeutic interventions.

Methodology:

- Live-Cell Imaging: Label organoids with nuclear markers (e.g., H2B-GFP) and vital dyes (e.g., DRAQ7) to track cell birth and death events dynamically [19].

- Morphometric Analysis: Quantify organoid volume, sphericity, and ellipticity to assess growth patterns and structural changes [19].

- Dose-Response Modeling: Calculate IC₅₀ values and growth inhibition percentages from longitudinal size measurements.

- Response Classification: Differentiate cytotoxic vs. cytostatic effects based on live cell counts and death rates over time [19].

Data Interpretation: Organoid volume strongly correlates with live cell number, enabling both parameters as reliable metrics for dose-response studies. Morphological heterogeneity within and between patients can be quantified through sphericity and ellipticity indices [19].

Genetic Validation and Visualization

Principle: Implement computational tools for verification and visualization of genetic modifications in engineered organoid biobanks.

Methodology:

- CRISPR Array Analysis: Use specialized software (e.g., CrisprVi) to visualize and analyze CRISPR direct repeats and spacers [20].

- Sequence Alignment: Conduct multiple sequence alignment of spacer arrays to verify intended modifications.

- Consensus Sequence Finding: Identify consensus sequences of direct repeats and spacers across modified organoid lines using BLAST-based clustering [20].

- Variant Calling: Detect on-target and potential off-target edits through whole-genome or targeted sequencing.

Application: CrisprVi provides graphical representation of CRISPR loci, statistical analysis of direct repeats and spacers, and heatmap visualization of consensus sequences across multiple engineered organoid lines [20].

The strategic selection between patient-derived and engineered organoid biobanks should be guided by specific research goals. PDO biobanks offer unparalleled clinical relevance for personalized medicine and drug screening applications, preserving native genetic heterogeneity and tumor microenvironment interactions [15]. Engineered organoid biobanks provide powerful platforms for functional genomics and mechanistic studies, enabling systematic investigation of gene function in defined genetic backgrounds [17] [16]. The integration of these approaches through CRISPR engineering of PDOs represents the cutting edge of organoid research, combining physiological relevance with genetic tractability to advance precision oncology and therapeutic development [15]. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will increasingly bridge the gap between in vitro models and clinical applications, accelerating the development of personalized cancer therapies and our understanding of human disease mechanisms.

Application Notes

CRISPR-engineered organoids represent a transformative platform that bridges the gap between traditional 2D cell cultures and in vivo models. By combining the physiological relevance of three-dimensional tissue structures with precise genome editing, these models enable unprecedented investigation of disease mechanisms, drug responses, and personalized therapeutic strategies [4] [11].

Table 1: Key Applications of CRISPR-Engineered Organoids

| Application Domain | Specific Uses | Key Advantages | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personalized Medicine | • Modeling patient-specific genetic variants• Ex vivo therapeutic testing• Predicting individual drug response | • Preserves patient genomic background• Enables "clinical trials in a dish"• Recapitulates tumor microenvironment | • Gastric cancer organoids for cisplatin response testing [3]• Biobanks of patient-derived tumoroids [11] |

| Cancer Research | • Functional genomics screens• Oncogene/tumor suppressor validation• Tumor evolution studies | • Identifies gene-drug interactions• Models cancer hallmarks in 3D context• Reveals therapeutic vulnerabilities | • Genome-wide CRISPR screens in gastric organoids [3]• PTEN knockout modeling in colorectal cancer [21] |

| Drug Development | • Target identification & validation• Preclinical efficacy & toxicity testing• Mechanism of action studies | • More predictive than 2D models• Reduces reliance on animal models• High-throughput compatible | • Identification of TAF6L in cisplatin response [3]• Drug screening in colorectal carcinoma organoids [11] |

Advancing Personalized Medicine

The integration of CRISPR with patient-derived organoids (PDOs) enables the creation of bespoke disease models. These isogenic models allow researchers to study the specific impact of individual genetic variants against a consistent genetic background, pinpointing causal mutations and their functional consequences [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for assessing inter-patient variability in drug response, a technique known as pharmacotyping, which has been successfully demonstrated in pancreatic, ovarian, and colorectal cancer organoids [11]. The ability to maintain the original patient's genomic context while introducing specific edits makes these models powerful tools for predicting individual therapeutic outcomes.

Transforming Cancer Research

CRISPR-engineered organoids have significantly advanced cancer research by enabling systematic investigation of oncogenic processes in a physiologically relevant context. Large-scale CRISPR screens in 3D gastric organoids have identified novel genes modulating chemotherapy response, uncovering previously unappreciated connections such as the link between fucosylation and cisplatin sensitivity [3]. The use of complex CRISPR tools—including knockout, interference (CRISPRi), activation (CRISPRa), and single-cell approaches—in organoid models provides comprehensive insights into gene-drug interactions that were previously inaccessible using conventional models [3].

Streamlining Drug Development

The pharmaceutical industry benefits from CRISPR-engineered organoids through improved target validation and more predictive preclinical testing. Organoid models demonstrate higher clinical translatability compared to 2D cell lines, better recapitulating therapeutic vulnerabilities observed in patients [3] [4]. Recent regulatory changes, including the FDA's updated stance on animal testing requirements, have accelerated the adoption of these human-based models in drug development pipelines [4]. The high editing efficiencies achieved with non-viral RNP-based methods (up to 98%) enable rapid generation of engineered models for functional studies without the need for clonal selection, significantly reducing development timelines [21].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Large-Scale CRISPR Screening in Human Gastric Organoids

This protocol enables genome-wide CRISPR screening in primary human 3D gastric organoids to systematically identify genes affecting drug sensitivity, as demonstrated in recent studies investigating cisplatin response [3].

Materials

- Primary human gastric organoids (TP53/APC DKO model)

- Lentiviral Cas9 expression vector

- Pooled lentiviral sgRNA library (e.g., 12,461 sgRNAs targeting 1093 genes + 750 non-targeting controls)

- Puromycin selection antibiotic

- Cisplatin (or other chemotherapeutic agent for modulation studies)

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Methodology

1. Cas9-Expressing Organoid Line Generation

- Generate stable Cas9-expressing TP53/APC double knockout (DKO) gastric organoids using lentiviral transduction.

- Validate Cas9 activity through GFP reporter assay (>95% knockout efficiency recommended).

2. Pooled Library Transduction

- Transduce Cas9-expressing organoids with pooled lentiviral sgRNA library at MOI ensuring >1000 cells per sgRNA.

- Maintain cellular coverage >1000 cells per sgRNA throughout screening.

- Initiate puromycin selection 48 hours post-transduction; continue for 5-7 days.

3. Experimental Timeline & Selection

- Harvest reference sample (T0) 2 days post-selection for baseline sgRNA distribution.

- Culture remaining organoids under experimental conditions (e.g., cisplatin treatment) for 28 days (T1).

- Maintain consistent cellular coverage throughout culture period.

4. Analysis & Hit Identification

- Extract genomic DNA from T0 and T1 organoid populations.

- Amplify integrated sgRNA sequences and perform next-generation sequencing.

- Calculate sgRNA abundance changes between T0 and T1 using specialized analysis pipelines.

- Identify significantly depleted or enriched sgRNAs (compared to non-targeting controls) indicating growth disadvantages or advantages under selection.

5. Validation

- Select top hits for independent validation using individual sgRNAs.

- Confirm phenotype recapitulation in separate experiments.

- Perform downstream functional studies to characterize mechanism.

Protocol: High-Efficiency RNP-Based Editing of Human Intestinal Organoids

This non-viral protocol achieves up to 98% editing efficiency in human intestinal organoids using ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, eliminating the need for clonal selection [21].

Materials

- Human intestinal organoids (adult or fetal-derived)

- Recombinant Cas9 protein

- Synthetic sgRNAs (designed using Benchling/Indelphi)

- Electroporation system (Lonza Nucleofector recommended)

- P3 Primary Cell Solution (Lonza)

- Matrigel or similar extracellular matrix

- Intestinal organoid culture medium with growth factors

Methodology

1. Guide RNA Design & Validation

- Design 3 sgRNAs per target gene targeting early exons.

- Select guides with on-target score >40, off-target score >80, frameshifting score >80.

- Pre-test guides in cell lines and analyze editing efficiency using ICE analysis.

2. Organoid Preparation & Dissociation

- Culture intestinal organoids to appropriate size (~100-200μm diameter).

- Dissociate organoids to single cells using enzymatic digestion.

- Count cells and aliquot 100,000 cells per electroporation condition.

3. RNP Complex Formation

- Complex recombinant Cas9 protein (5μg) with synthetic sgRNA (100pmol).

- Incubate at room temperature for 10-15 minutes to form RNP complexes.

4. Electroporation

- Use Lonza Nucleofector with DS-138 program and P3 buffer.

- Electroporate RNP complexes with 100,000 cells per condition.

- Immediately transfer cells to pre-warmed recovery medium.

5. Organoid Reformation & Analysis

- Embed transfected cells in Matrigel and culture with intestinal organoid medium.

- Analyze editing efficiency 3-7 days post-electroporation using ICE or NGS.

- Validate protein knockout by Western blot, immunohistochemistry, or WesTM.

6. Functional Characterization

- Assess phenotypic consequences (e.g., budding frequency, proliferation rates).

- Perform transcriptional profiling for pathway analysis.

- Validate functional outcomes (e.g., p-AKT elevation in PTEN KO).

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Organoid Engineering

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Editors | • SpCas9 (wild-type)• dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi)• dCas9-VPR (CRISPRa)• Base editors (ABE, CBE)• Prime editors | • Gene knockout, repression, or activation• Single-nucleotide editing without DSBs• Diverse editing modalities for different applications | • Use SpCas9 for NGG PAM sites [22]• Inducible systems enable temporal control [3]• Base editors preferred for point mutations [22] |

| Delivery Systems | • Lentiviral vectors• Electroporation (RNP)• Lipofection | • Stable integration for long-term expression• High efficiency with minimal off-target effects• Alternative non-viral method | • RNP achieves >95% efficiency in intestinal organoids [21]• Viral methods enable pooled library screens [3] |

| Organoid Culture | • Matrigel/ECM substitutes• Growth factor cocktails• R-spondin, EGF, Noggin, Wnt3a | • Provides 3D structural support• Maintains stem cell niche signaling• Essential for organoid growth and differentiation | • Composition critical for phenotype retention [11]• Growth factor independence can enable selection [22] |

| Selection Tools | • Antibiotic resistance (puromycin)• Fluorescent reporters (GFP/mCherry)• Growth factor independence | • Enriches for successfully edited cells• Enables tracking and sorting of edited populations• Functional selection based on edited phenotype | • FACS sorting for inducible systems [3]• -WNT/Rspo1 selection for APC KO [22] |

Advanced Methodologies

Inducible CRISPR Systems for Temporal Control

The development of inducible CRISPR systems (iCRISPR) enables precise temporal control over gene expression in organoids. These systems utilize doxycycline-inducible dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi) or dCas9-VPR (CRISPRa) constructs for reversible gene repression or activation [3]. The tight regulation of these systems allows investigators to study gene function at specific developmental timepoints or to model the sequential acquisition of mutations, mirroring the natural progression of diseases like cancer.

Next-Generation CRISPR Tools for Precision Editing

Beyond conventional CRISPR-Cas9, base editors and prime editors offer more precise genome engineering capabilities without introducing double-strand breaks (DSBs) [22]. These tools are particularly valuable for introducing specific patient-derived point mutations or for correcting pathogenic variants in disease modeling. The editing workflow follows a strategic approach: selection of the appropriate editor based on the desired nucleotide change, careful sgRNA design to maximize efficiency, and delivery via electroporation for optimal results in organoid systems [22].

Step-by-Step Protocols for Successful CRISPR Editing in Organoids

The integration of CRISPR-based genome editing with three-dimensional (3D) organoid culture represents a transformative approach in biomedical research, enabling the development of highly physiologically relevant human disease models. Organoids are in vitro 3D cultures derived from pluripotent or adult stem cells that self-organize to recapitulate the structural, genetic, and functional characteristics of native organs [11]. The essence of a successful organoid system lies in its ability to replicate the in vivo tissue environment through presence of heterogeneous cell populations and mechanical connections with adjacent cells and the intercellular matrix [11]. When combined with CRISPR screening technologies, organoids become powerful platforms for investigating gene function, oncogenic vulnerabilities, developmental pathways, and therapeutic responses in a human physiological context [11] [3]. The fidelity of these models, however, is critically dependent on the optimization of culture conditions, extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffolds, and growth media formulations, which together provide the necessary biochemical and biophysical cues to support stem cell maintenance, differentiation, and 3D organization.

Critical Components for Organoid Culture

Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Scaffolds

The ECM serves as the fundamental scaffold for 3D organoid growth, providing structural support and essential biochemical signals that regulate cell behavior, including proliferation, differentiation, and spatial organization.

- Matrigel: This reconstituted basement membrane extract derived from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse sarcomas remains the gold standard ECM for many organoid cultures. It is rich in laminin, collagen IV, and other ECM proteins, along with growth factors that support cell adhesion and morphogenesis [11] [23]. Despite its widespread use, Matrigel has significant limitations: its murine origin and tumor derivation raise translational concerns, its complex and undefined composition leads to batch-to-batch variability, and its mechanical properties are suboptimal for certain tissues like bone [23] [24] [25].

- Animal-Free Alternatives: Recent advances have focused on developing defined, synthetic, or human-derived matrices to overcome Matrigel's limitations, enhancing reproducibility and clinical applicability.

- Fibrin-Based Hydrogels: Composed of fibrinogen and thrombin, these hydrogels offer excellent biocompatibility, support angiogenic sprouting, and are particularly effective for vascular organoid culture [23].

- PIC-Invasin Gel: A fully synthetic alternative combining polyisocyanopeptide (PIC) with the bacterial protein invasin supports long-term 3D growth of various human and mouse organoids without animal components [26].

- Vitronectin: This recombinant human protein serves as an effective xeno-free substrate for 2D culture of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) prior to 3D differentiation, maintaining pluripotency and supporting subsequent vascular organoid formation [23].

Growth Media and Signaling Molecules

Precisely formulated growth media are indispensable for directing stem cell differentiation and maintaining organoid phenotype. These media typically contain defined cocktails of growth factors, signaling molecules, and supplements that mimic the niche signaling pathways active during organ development and homeostasis [27]. The specific combination and concentration of these factors must be meticulously optimized for each organoid type. Commonly used components include Wnt agonists (e.g., R-spondin-1), growth factors (e.g., Epidermal Growth Factor), BMP inhibitors (e.g., Noggin), and TGF-β pathway modulators [11] [28]. The transition to animal-free culture conditions also necessitates the use of recombinant growth factors to eliminate variability and ethical concerns associated with animal-derived components.

Advanced Culture Techniques

Ensuring adequate oxygen and nutrient supply throughout 3D organoids remains a significant challenge. Traditional static culture systems can create diffusion-limited gradients, leading to necrotic cores in larger organoids. Advanced dynamic culture systems, such as spinning bioreactors and microfluidic devices, improve mass transfer and mimic physiological flow, promoting more uniform growth and enhanced maturation [27]. For specialized applications like bone organoids, the integration of biomechanical stimulation via bioreactors that apply cyclic stress is crucial for replicating the native bone microenvironment and promoting osteogenic differentiation [25].

Quantitative Comparison of Culture Formulations

Table 1: Comparison of Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Scaffolds for Organoid Culture

| Matrix Type | Composition | Origin | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Demonstrated Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrigel | Complex mixture of laminin, collagen IV, entactin, growth factors | Mouse tumor (EHS sarcoma) | High biocompatibility; supports diverse organoid types | Batch-to-batch variability; undefined composition; animal origin | Intestinal, breast, gastric, renal, tumoroid cultures [11] [23] |

| Fibrin Hydrogel | Fibrinogen polymerized with thrombin | Human (recombinant) | Animal-free; biocompatible; supports angiogenesis | May require optimization of stiffness and degradation | Vascular organoids, endothelial cell sprouting [23] |

| PIC-Invasin Gel | Synthetic PIC polymer functionalized with invasin protein | Synthetic (animal-free) | Fully defined and synthetic; thermo-reversible; transparent | Relatively new technology | Long-term 3D culture of mouse intestinal and human organoids [26] |

| Vitronectin | Recombinant human vitronectin protein | Human (recombinant) | Xeno-free; defined composition; supports iPSC pluripotency | Primarily for 2D culture prior to 3D differentiation | iPSC culture and expansion for subsequent vascular organoid differentiation [23] |

Table 2: Growth Media Components for Various Organoid Models

| Organoid Type | Essential Base Medium | Critical Growth Factors & Supplements | Function of Key Components | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Tumor Organoids | Varies by tissue type; often growth factor-reduced | Wnt3A, R-spondin-1, Noggin, EGF, TGF-β inhibitor | Supports stem cell expansion and maintains tumor heterogeneity | [11] [28] |

| Human Intestinal Organoids | IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium | As per commercial formulation; often includes Wnt agonist, R-spondin-1 | Maintains crypt-villus structure and stem cell compartment | [29] |

| Gastric Organoids (for CRISPR screens) | Not specified (Custom formulation) | Growth factor cocktail inducing proliferation | Supports expansion of stem cell compartment in 3D culture | [11] [3] |

| Vascular Organoids (BVOs) | Custom differentiation medium | Specific induction factors for mesoderm and endothelial lineage | Directs hiPSC differentiation into endothelial and mural cells | [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing in Human Intestinal Organoids

This protocol outlines the steps for efficient CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing in human intestinal organoids cultured in IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium using a ribonucleoprotein (RNP)-based delivery system [29].

Part I: Preparation of sgRNA Working Solution

- Centrifuge the vial of ArciTect sgRNA briefly before opening.

- Resuspend the sgRNA in nuclease-free water to a final concentration of 100 µM.

- Mix thoroughly, aliquot, and store at -20°C for up to 6 months. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Part II: Preparation of Culture Media

- Complete IntestiCult Medium: Thaw the Human Basal Medium and Organoid Supplement components. Mix 50 mL of Organoid Supplement with 50 mL of Human Basal Medium. Add antibiotics (e.g., 50 µg/mL gentamicin) immediately before use.

- DMEM + 1% BSA: Add 2 mL of 25% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to 48 mL of DMEM/F-12 with 15 mM HEPES. Mix well by inversion and keep on ice.

Part III: Preparation of Organoid Single-Cell Suspension

- Warm a 24-well tissue culture plate and complete IntestiCult medium to 37°C. Thaw Matrigel on ice.

- Carefully remove and discard the medium from the organoid culture well without disturbing the Matrigel dome.

- Add 500 µL of pre-warmed ACCUTASE containing 10 µM Y-27632 (a ROCK inhibitor) onto the dome and incubate for 1 minute at room temperature.

- Using a pre-wetted pipette tip, rinse and scrape the dome free from the well bottom, pipetting up and down to break up the organoids. Transfer the mixture to a tube.

- Repeat the washing step with another 500 µL of ACCUTASE + Y-27632 and pool the contents.

- Incubate the tube in a 37°C water bath for 20 minutes, pipetting the mixture vigorously every 5 minutes to achieve a single-cell suspension.

- Centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 minutes. Resuspend the cell pellet in 1 mL of DMEM + 1% BSA and filter through a 70 µm strainer. Count the cells.

- Prepare 1 × 10^5 cells per electroporation reaction, pellet again, and proceed immediately to electroporation.

Part IV: Electroporation with CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex

- For Neon Transfection System: Prepare the RNP complex mix by combining 6.0 µL Resuspension Buffer T, 0.90 µL ArciTect Cas9 Nuclease (4 µg/µL), and 0.60 µL of the 100 µM sgRNA per reaction (Table 2).

- Incubate the RNP complex at room temperature for 10-20 minutes.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in the RNP complex mix.

- Electroporate using the Neon system (typically 1100-1700 V, 20-30 ms, 1-2 pulses; optimize for specific cell source).

- Immediately transfer the electroporated cells into pre-warmed complete IntestiCult medium containing Y-27632.

Part V: Post-Electroporation Culture and Analysis

- Mix the cells with cold Matrigel and plate as domes in the pre-warmed 24-well plate. Allow the Matrigel to polymerize for 10-20 minutes at 37°C.

- Carefully overlay each dome with 750 µL of complete IntestiCult medium + Y-27632.

- Culture the organoids at 37°C, changing the medium every 2-3 days. Y-27632 can be removed after 2-3 days.

- Monitor organoid growth and harvest for downstream genomic DNA extraction and editing efficiency analysis (e.g., T7 Endonuclease I assay, Sanger sequencing, or next-generation sequencing) after 5-10 days.

Workflow: Establishing a CRISPR Screen in Gastric Organoids

This workflow, adapted from a large-scale screen in primary human 3D gastric organoids [3], illustrates the key steps for identifying genes that modulate responses to stimuli like chemotherapeutic drugs. Critical parameters include maintaining a cellular coverage of >1000 cells per sgRNA to ensure library representation and determining an appropriate endpoint based on the selective condition applied.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Organoid Research

| Reagent / Kit | Supplier / Reference | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium (Human) | STEMCELL Technologies [29] | Supports the growth and maintenance of human intestinal organoids | Used as a complete, optimized medium in the detailed CRISPR editing protocol. |

| ArciTect CRISPR-Cas9 System | STEMCELL Technologies [29] | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex for precise genome editing | Allows for direct delivery of precomplexed Cas9 and sgRNA, reducing off-target effects. |

| Corning Matrigel Matrix, GFR | Corning [29] | Standard basement membrane matrix for 3D organoid culture | Growth Factor Reduced (GFR) and phenol-red-free versions are often preferred. |

| PIC-Invasin Gel | Hubrecht Institute [26] | Fully synthetic, animal-free hydrogel for 3D organoid culture | Emerging alternative to Matrigel; offers defined composition and reduced variability. |

| Vitronectin XF | Various [23] | Recombinant human protein for xeno-free 2D culture of iPSCs | Serves as a feeder-free substrate for pluripotent stem cell culture prior to organoid differentiation. |

| Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) | Various [29] | Improves viability of single stem cells after dissociation | Crucial for enhancing cell survival after passaging or electroporation. |

| ACCUTASE | STEMCELL Technologies [29] | Enzyme blend for gentle cell dissociation | Used to generate single-cell suspensions from organoids for electroporation. |

| Neon Transfection System / 4D-Nucleofector X | Thermo Fisher / Lonza [29] | Electroporation devices for efficient RNP delivery into cells | Essential for introducing CRISPR RNP complexes into hard-to-transfect primary organoid cells. |

The successful integration of CRISPR technologies with organoid models hinges on the meticulous optimization of the culture microenvironment. While Matrigel remains a widely used and effective ECM, the field is steadily moving toward defined, animal-free alternatives like fibrin hydrogels and PIC-invasin gels to enhance reproducibility and clinical translation [23] [26]. Similarly, the development of standardized, xeno-free media formulations is critical for reducing batch variability. Future advancements will likely focus on increasing cellular complexity through assembloid approaches, improving vascularization to support larger organoids, and incorporating biomechanical cues via specialized bioreactors [25] [28]. The combination of optimized culture conditions, sophisticated ECM scaffolds, and precise genome editing will continue to elevate organoids as indispensable tools for decoding human development, disease mechanisms, and personalized therapeutic screening.

The development of robust CRISPR organoid engineering protocols is a cornerstone of modern biomedical research, enabling precise disease modeling and drug development. The efficacy of these protocols is profoundly influenced by the choice of gene delivery method. This Application Note provides a detailed comparative analysis of three central techniques—electroporation, lentiviral transduction, and the delivery of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes—within the context of adult stem cell (ASC)-derived organoid engineering. We summarize key performance metrics, provide actionable protocols optimized for organoid systems, and delineate a decision-making framework to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate method for their experimental goals.

The table below provides a high-level comparison of the three delivery methods, synthesizing data from recent organoid studies.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of CRISPR Delivery Methods for Organoid Engineering

| Feature | Electroporation | Lentiviral Transduction | RNP Complex Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Cargo | Plasmid DNA, mRNA, RNP complexes [21] [30] | DNA plasmids encoding Cas9 and gRNA (integrated into host genome) [31] | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and gRNA (RNP) [32] [33] |

| Editing Efficiency | Up to 98% (with RNP cargo) [21] | 30-50%, up to 80-100% with optimized protocols [21] | Consistently high, often >70-98% [33] [21] |

| Mechanism of Action | Physical application of an electrical field to create transient pores in the cell membrane [21] | Viral infection leading to genomic integration of the CRISPR cassette [31] | Direct delivery of active editing complex; transient activity [32] |

| Off-Target Rate | Lower (especially with RNP cargo) [21] | Higher (due to prolonged Cas9/gRNA expression) [31] [33] | Lowest (due to transient cellular presence) [33] [21] |

| Cytotoxicity | Variable, can be high depending on parameters [33] | Variable, can trigger immune responses [31] | Low cytotoxicity [33] |

| Indel Pattern | Clean, predominantly on-target with RNP [21] | Complex, potential for on- and off-target plasmid integration [31] [33] | Clean, minimal non-specific indels [32] [21] |

| Experimental Timeline | Days to a few weeks [21] | Weeks to months (due to viral production) [21] | Shortest; reduced by 50% compared to plasmids [33] |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

High-Efficiency RNP Delivery via Electroporation

This protocol describes the optimal procedure for achieving high-efficiency gene editing in human intestinal organoids using CRISPR RNP complexes delivered by electroporation, achieving knockout efficiencies up to 98% [21].

Key Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for RNP Electroporation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | Purified nuclease for RNP complex formation. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | High-quality, research-grade single-guide RNA; chemically modified to enhance stability [33]. |

| Lonza P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit | Contains optimized electroporation buffer and cuvettes. |

| Nucleofector Device (e.g., 4D-Nucleofector System) | Instrument for applying predefined electrical programs. |

| Organoid Culture Media | Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with essential growth factors (e.g., EGF, Noggin, R-spondin) [22]. |

| Extracellular Matrix (e.g., Matrigel) | 3D scaffold to support organoid growth and development. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

- sgRNA Design and Validation: Design sgRNAs using online tools (e.g., Benchling) with high on-target (>40) and off-target (>80) scores. Target an early exon to ensure frameshift mutations. Recommendation: Design and test three guides per gene in a cell line (e.g., HEK293T) using the ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) tool to identify the highest-performing guide before proceeding to organoids [21].

- RNP Complex Assembly: For 100,000 dissociated organoid cells, complex 5 µg of recombinant Cas9 protein with 100 pmol of synthetic sgRNA. Incubate at room temperature for 10-15 minutes to allow RNP formation [21].

- Organoid Dissociation: Harvest and dissociate human intestinal organoids into single cells or small clumps using a gentle cell dissociation reagent. Centrifuge and resuspend the cell pellet in Lonza P3 Nucleofector Solution [21].

- Electroporation: Mix the cell suspension with the pre-assembled RNP complex. Transfer the entire mixture into a Nucleofector cuvette. Electroporate using the DS-138 program on the 4D-Nucleofector System [21].

- Recovery and Seeding: Immediately after electroporation, add pre-warmed culture medium to the cuvette. Seed the transfected cells in a droplet of extracellular matrix and overlay with organoid culture medium.

- Validation and Expansion: After 5-7 days of growth, extract genomic DNA and analyze editing efficiency via Sanger sequencing and ICE analysis, or next-generation sequencing (NGS). Expand edited organoid cultures for functional studies [21].

Lentiviral Transduction for Organoid Engineering

This protocol is adapted for delivering CRISPR components via lentiviral vectors, which is suitable for long-term expression studies but requires careful biosafety considerations.

Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Lentiviral Transduction

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Lentiviral Transfer Plasmid | Plasmid encoding Cas9 and sgRNA expression cassettes, with LTRs and packaging signal. |

| Packaging Plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G) | Provide viral structural proteins and envelope glycoprotein for virus production. |

| HEK293T Cells | Production cell line for generating high-titer lentiviral particles. |

| Polybrene | Polycation that enhances viral infection efficiency by neutralizing charge repulsion. |

| Puromycin or other Antibiotics | For selection of successfully transduced organoids, if the vector contains a resistance gene. |

Step-by-Step Protocol

- Viral Particle Production: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the lentiviral transfer plasmid and packaging plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G) using a standard transfection method. Harvest the viral supernatant at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection. Concentrate the supernatant and determine the viral titer [31] [21].

- Organoid Infection: Dissociate organoids into single cells or small clusters. Incubate the cells with the concentrated lentivirus in the presence of 4-8 µg/mL Polybrene. Centrifuge the plate (e.g., at 600 x g for 60-120 minutes) to enhance infection (spinoculation) [21].

- Selection and Expansion: After 24-48 hours, begin antibiotic selection (e.g., Puromycin) if applicable to enrich for transduced cells. Culture the selected organoids for expansion. The integrated CRISPR cassette allows for continuous expression, which is useful for difficult-to-edit targets but increases off-target risks [31] [34].

- Validation: Validate editing efficiency as described in section 3.1.2. Note that the constant presence of the nuclease may require outgrowth or single-cell cloning to isolate pure edited populations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Organoid Engineering

| Category | Reagent | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease & Guides | Recombinant SpCas9 Protein | Core enzyme for DNA cleavage in RNP delivery [32] [21]. |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Programmable RNA guide; synthetic version offers high quality and consistency [33]. | |

| Delivery & Transfection | Lonza 4D-Nucleofector System & Kits | Instrumentation and optimized buffers for electroporation of sensitive primary cells [21]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A non-viral delivery vehicle for encapsulating and delivering RNP complexes [31] [30]. | |

| Cell Culture & Organoids | Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel | Standard extracellular matrix for 3D organoid culture and embedding. |

| Essential Growth Factors (EGF, Noggin, R-spondin) | Niche factors critical for sustaining stemness and growth in intestinal organoid media [22]. | |

| Selection & Analysis | Puromycin Dihydrochloride | Antibiotic for selecting cells transduced with vectors containing a puromycin resistance gene [22]. |

| Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) Tool | Software for deconvoluting Sanger sequencing traces to calculate editing efficiency [21]. |

Technical Decision Framework

Selecting the optimal delivery method requires balancing efficiency, precision, and experimental timeline. The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway based on project goals.

Pathway to Selection:

- Prioritize high efficiency and low off-targets: The primary recommendation is RNP delivery via electroporation. This combination leverages the transient nature of RNPs to minimize off-target effects while achieving knockout efficiencies upwards of 95% in various organoid systems [33] [21].

- Require stable, long-term expression: If the experimental goal necessitates persistent Cas9/gRNA expression (e.g., for in vivo screening or continuous gene repression), lentiviral transduction is the appropriate choice, despite its longer timeline and higher risk of off-target effects [31] [34].

- Balance timeline and ease-of-use: For projects where timeline is less critical and viral production is feasible, lentiviral vectors remain a viable option. However, for most applications requiring precise, transient editing, RNP electroporation offers a superior balance of speed, efficiency, and precision [33] [21].

CRISPR-based functional genomics in primary human organoids represent a significant advancement over traditional 2D cell line models, as they preserve tissue architecture, stem cell activity, and genomic alterations of primary tissues [3]. This protocol details the establishment of large-scale CRISPR screening platforms in human gastric organoids, enabling comprehensive dissection of gene-drug interactions through knockout (CRISPR-KO), interference (CRISPRi), and activation (CRISPRa) approaches [3]. The methodologies described herein were developed within the broader context of thesis research on CRISPR organoid engineering protocols, with particular focus on their application for investigating therapeutic vulnerabilities in gastric cancer and repair of disease-causing mutations [3] [35].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents for CRISPR organoid screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|