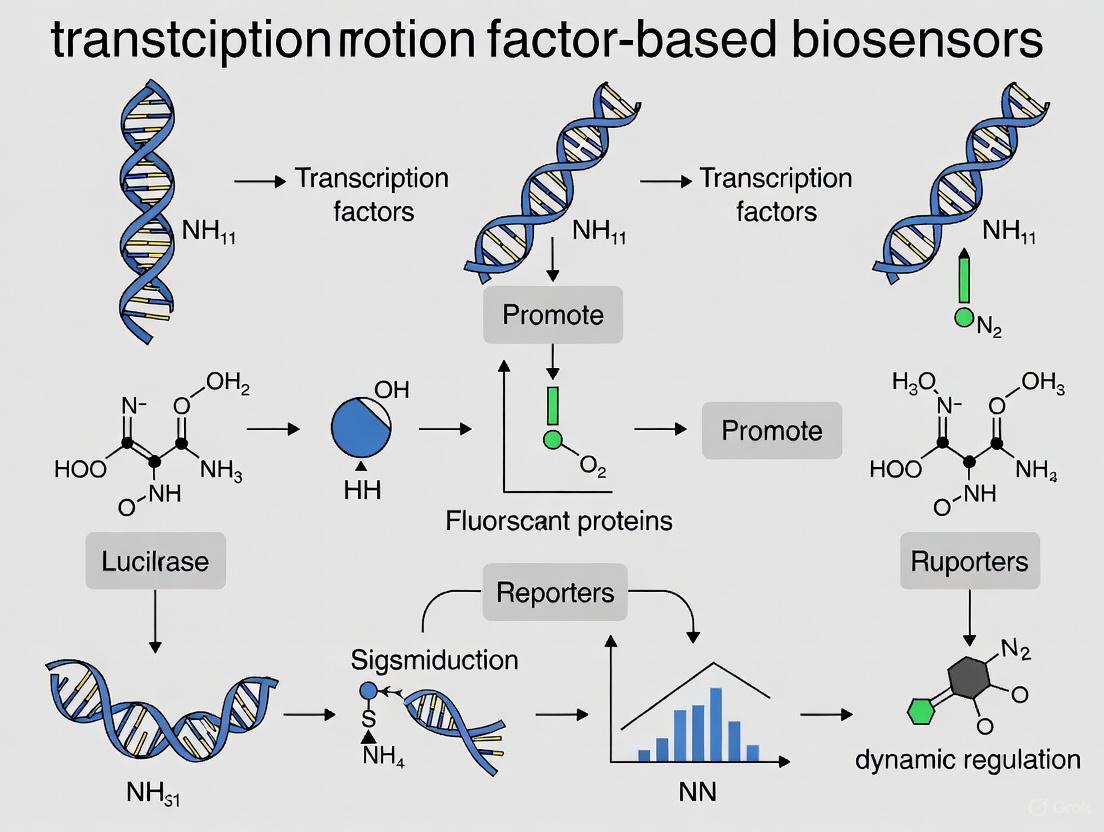

Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors for Dynamic Regulation: From Design Principles to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of transcription factor (TF)-based biosensors as powerful tools for dynamic regulation in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering.

Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors for Dynamic Regulation: From Design Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of transcription factor (TF)-based biosensors as powerful tools for dynamic regulation in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental mechanisms of these genetically encoded devices, detailing how they convert small-molecule detection into precise control of cellular processes. The content covers established and emerging engineering strategies—from promoter and ribosome binding site tuning to advanced computational design—for optimizing biosensor performance parameters such as dynamic range, specificity, and sensitivity. Furthermore, it examines critical applications in high-throughput screening and dynamic pathway control, discusses validation frameworks and comparative analyses with other biosensor types, and concludes with future perspectives on integrating artificial intelligence and cell-free systems to overcome current limitations in bioproduction and therapeutic development.

The Core Mechanics of TF-Based Biosensors: Understanding Nature's Molecular Switches

Transcription factor (TF)-based biosensors are genetically encoded tools that enable engineered cells to detect specific small molecules and convert this recognition into a measurable biological output [1] [2]. These systems are fundamental to advancing synthetic biology, serving as critical components for dynamic metabolic regulation, high-throughput screening of microbial cell factories, and real-time monitoring of metabolic fluxes [3] [4]. Their operation mirrors conventional biosensor architecture, comprising three core modules: a sensing module for analyte recognition, a transduction module for signal conversion, and an output module for generating a quantifiable signal [5]. This guide details the basic components and working principles of these modules, providing a technical foundation for their application in dynamic regulation research.

Core Component 1: The Sensing Module

The sensing module is responsible for the specific detection of an intracellular or extracellular analyte. Its core component is the transcription factor (TF), a protein that binds a target molecule (ligand) and undergoes a conformational change that modulates its ability to regulate transcription [1] [5].

Mechanism of Analyte Recognition

Transcription factors are typically modular proteins consisting of two primary domains:

- Effector-Binding Domain (EBD): This domain is responsible for ligand recognition and specificity. Upon binding its cognate ligand, the EBD undergoes a conformational change [2] [5].

- DNA-Binding Domain (DBD): This domain recognizes and binds to a specific DNA sequence, known as the operator or transcription factor binding site (TFBS), within a promoter region [2] [5].

The binding of the ligand to the EBD allosterically affects the DNA-binding affinity of the DBD. This mechanism varies depending on whether the TF functions as a repressor or an activator [5]:

- Transcriptional Repressors: In the absence of the inducer molecule, the repressor TF is bound to its operator site, physically blocking RNA polymerase (RNApol) and preventing transcription. Ligand binding induces a conformational change that causes the repressor to dissociate from the DNA, allowing transcription to proceed [5].

- Transcriptional Activators: These TFs typically bind to their operator site and recruit RNApol to the promoter only when the ligand is bound. The ligand-induced conformational change enables productive interactions with the RNApol, initiating transcription [5].

Table 1: Major Transcription Factor Families and Their Analytes

| TF Family | Primary Analyte Types | Example TFs | Regulatory Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| MerR | Metal ions, antibiotics | MerR, ArsR | Activator/Repressor |

| AraC/XylS | Aromatic compounds | XylS, AraC | Activator |

| LysR | Aromatic compounds, metabolites | LysR | Activator |

| TetR | Antibiotics, diverse small molecules | TetR | Repressor |

| MarR | Antibiotics, phenolic compounds | MarR | Repressor |

Core Component 2: The Transduction Module

The transduction module transmits the signal from the sensing module to the gene expression machinery, ultimately controlling the production of the output signal. This module is primarily composed of the TF-specific promoter [4].

The Promoter as a Signal Transducer

The promoter is a DNA sequence located upstream of the output gene. The key element for transduction is the Transcription Factor Binding Site (TFBS), the specific DNA sequence recognized by the TF's DBD [4]. The interaction between the ligand-bound TF and its TFBS determines the rate of transcription initiation for the downstream output gene. The design of this promoter, including the number, affinity, and precise location of the TFBS relative to the core promoter elements (e.g., -35 and -10 boxes), is critical for defining the performance of the biosensor [6].

Core Component 3: The Output Module

The output module is responsible for generating a quantifiable signal based on the transcriptional activity of the promoter. This allows researchers to infer the concentration of the target analyte.

Common Reporter Outputs

- Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., GFP, eGFP): Enable real-time, non-destructive monitoring of analyte concentration via fluorescence intensity measurements [1] [7].

- Luminescent Enzymes (e.g., Luciferase): Produce light as a readout, offering high sensitivity and a broad dynamic range [5].

- Enzymatic Reporters (e.g., β-Galactosidase): Catalyze reactions that generate colorimetric or chemiluminescent products, suitable for endpoint assays [5].

The output module's choice depends on the application, with fluorescent proteins being favored for high-throughput screening and real-time monitoring within live cells [1].

Performance Characterization of TF-Based Biosensors

The performance of a TF-based biosensor is evaluated using a set of key metrics, typically characterized by an input-output dose-response curve [3] [6]. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and performance parameters.

Diagram 1: Biosensor workflow and key performance metrics

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Biosensor Evaluation

| Performance Metric | Definition | Impact on Biosensor Function |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | The ability to distinguish the target analyte from other similar molecules [6]. | Reduces false positives and ensures output accuracy. |

| Sensitivity | The minimal change in analyte concentration required to produce a detectable change in output signal [6]. | Determines the biosensor's ability to detect subtle concentration changes. |

| Dynamic Range | The fold-change between the maximal and minimal output signal levels [1] [6]. | A larger dynamic range provides a clearer distinction between induced and uninduced states. |

| Operating Range | The concentration window of the analyte over which the biosensor responds effectively [3]. | Defines the useful detection limits for the biosensor. |

| Response Time | The speed at which the biosensor reaches its half-maximal output after analyte exposure [3] [6]. | Critical for applications requiring real-time monitoring and rapid feedback control. |

Essential Methodologies for Biosensor Implementation and Tuning

Constructing and optimizing a TF-based biosensor for a specific research context requires a structured experimental approach. The process typically involves genetic circuit construction, performance characterization, and iterative tuning.

Genetic Circuit Construction and Validation

The foundational step involves assembling the genetic components into a functional biosensor within a host organism (e.g., E. coli).

Detailed Protocol: Construction of a TtgR-based Flavonoid Biosensor [7]

- Component Amplification: Amplify the gene encoding the transcription factor (e.g.,

ttgRfrom Pseudomonas putida genomic DNA) and its native promoter/operator region (PttgABC) using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). - Plasmid Assembly: Clone the

ttgRgene into a plasmid with an appropriate antibiotic resistance marker (e.g., pCDF-Duet, spectinomycin resistance). Clone thePttgABCpromoter upstream of a reporter gene (e.g.,egfp) in a compatible plasmid (e.g., pET-21a(+), ampicillin resistance). - Host Transformation: Co-transform both plasmids into a suitable microbial host, such as E. coli BL21(DE3).

- Biosensor Assay:

- Inoculate overnight cultures of the biosensor strain.

- Dilute cultures into fresh medium and expose them to a range of analyte concentrations (e.g., flavonoids like naringenin or quercetin).

- Incubate with shaking to allow for gene expression.

- Measure the output signal (e.g., fluorescence intensity for eGFP) using a microplate reader or flow cytometry.

- Data Analysis: Plot the dose-response curve (output signal vs. analyte concentration) to determine initial performance metrics like dynamic range and sensitivity.

Biosensor Tuning Strategies

Native biosensors often require optimization to achieve desired performance. Tuning can be applied at multiple levels:

- Promoter Engineering: Modifying the TF-specific promoter by altering the number, sequence, or position of the TF binding sites (TFBS) to fine-tune sensitivity, dynamic range, and cooperativity [6] [2].

- Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Engineering: Varying the strength of the RBS upstream of the TF or the reporter gene to control translation efficiency, thereby adjusting the dynamic range and output signal intensity [6] [4].

- Transcription Factor Engineering: Using directed evolution or rational design to mutate the TF's ligand-binding domain, altering its specificity, sensitivity, or operational range [6] [2] [7]. For example, engineering a TtgR variant (N110F) altered its sensing profile for flavonoids like resveratrol [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials essential for developing and working with TF-based biosensors.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors | Core sensing element; determines analyte specificity. | TtgR (flavonoids), ArsR (arsenic), ZntR (zinc/cadmium), LuxR (acyl-homoserine lactones) [1] [7]. |

| Reporter Genes | Generates measurable output signal. | Fluorescent proteins (eGFP, Venus), luminescent enzymes (luciferase), chromogenic enzymes (LacZ) [7] [5]. |

| Expression Vectors | Plasmid backbone for hosting biosensor genetic circuits. | pCDF-Duet, pET-21a(+), pZnt-eGFP; chosen for copy number and compatibility [7]. |

| Host Strains | Microbial chassis for biosensor operation. | E. coli BL21(DE3), E. coli DH5α [7]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Equipment | Enables rapid screening of mutant libraries or analyte detection. | Flow Cytometry (for fluorescence-activated cell sorting), Microplate Readers [3] [1]. |

| Analytes/Inducers | Used for biosensor calibration and functional testing. | Flavonoids (naringenin, quercetin), heavy metals (Hg²âº, As³âº), antibiotics, metabolic intermediates [1] [7]. |

Activator-Based vs. Repressor-Based Systems

Transcription factor (TF)-based biosensors are indispensable tools in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, enabling real-time monitoring of metabolites and dynamic control of genetic circuits. The core of these biosensors lies in their mode of action, primarily determined by whether the transcription factor functions as an activator or a repressor. Activator-based systems enhance gene expression upon sensing a target ligand, while repressor-based systems reduce it. Within the broader context of developing advanced biosensors for dynamic regulation research, understanding the distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations of these two systems is paramount for designing efficient microbial cell factories and high-throughput screening platforms [8] [4]. This guide provides a technical comparison of these systems, supplemented with quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visual resources tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development and related fields.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

The operational principle of both systems hinges on allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) that undergo a conformational change upon binding a specific effector molecule (ligand). This conformational change alters the TF's ability to bind its target DNA sequence, thereby modulating transcription of the downstream gene [9] [10].

- Activator-Based Systems: In the absence of the inducer, the activator TF is typically in an inactive state and cannot bind DNA. When the ligand is present, it binds to the TF, inducing a conformational change that allows the TF to bind its cognate promoter. This binding facilitates the recruitment of RNA polymerase (RNAP), leading to the activation of gene expression [11]. A simple analogy is an activator "unlocking" a promoter to allow transcription to proceed.

- Repressor-Based Systems: Conversely, in a repressor-based system, the TF is often active in its apo state and binds to the operator site within the promoter, physically blocking RNAP from initiating transcription. Binding of the effector molecule causes the repressor to dissociate from the DNA, thereby derepressing gene expression and allowing transcription to occur [11]. This is akin to a repressor "guarding" a promoter until the key ligand tells it to step aside.

It is crucial to note that some TFs exhibit duality, meaning they can function as activators for some genes and repressors for others. Furthermore, recent research identifies incoherent TFs, which can simultaneously exert both activating and repressive effects on a single target gene, potentially leading to non-monotonic, concentration-dependent responses [12].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanisms of activator-based and repressor-based biosensor systems.

Performance Characteristics and Quantitative Comparison

The choice between an activator and a repressor system depends heavily on the required performance characteristics, which include dynamic range, sensitivity, and the basal expression level (leakiness). These parameters are typically derived from an input-output response curve fitted using the Hill equation [4].

Key Performance Metrics:

- Dynamic Range: The fold difference between the fully induced (ON) and the uninduced (OFF) states of the biosensor. A wider dynamic range is generally preferred for clear signal distinction.

- Sensitivity (EC50/IC50): The ligand concentration required to achieve half of the maximum response. For activators, this is the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50); for repressors, it is the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50).

- Operating Range: The span of ligand concentrations over which the biosensor responds.

- Basal Expression (Leakiness): The level of output signal in the absence of the inducing ligand.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Characteristics of Activator vs. Repressor Systems

| Feature | Activator-Based System | Repressor-Based System |

|---|---|---|

| Default State (No Ligand) | Low output (OFF) | High output (ON) |

| State with Saturating Ligand | High output (ON) | Low output (OFF) |

| Typical Promoter Strength | Often uses weak promoters that require activation for significant transcription [11] | Often uses strong promoters that are constitutive unless repressed [11] |

| Basal Expression (Leakiness) | Can be very low | Can be high if repression is incomplete |

| Dynamic Range | Can be very high if basal expression is minimized | Can be high if repression is strong and leakiness is low |

| Common Applications | Dynamic upregulation of pathway genes; detection of metabolite accumulation [4] | High-throughput screening of producers; repression of competing pathways [9] |

Table 2: Example Biosensors and Their Modes of Action

| Transcription Factor | Effector/Ligand | Mode of Action | Host Organism | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LuxR | Acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) | Activator | E. coli | Quorum sensing, microbial communication [8] |

| MerR / ArsR | Hg²⺠/ As³⺠| Activator | E. coli | Heavy metal detection in environmental monitoring [8] |

| FadR | Fatty acyl-CoAs | Repressor | S. cerevisiae, E. coli | Screening for strains with enhanced fatty acid pools [4] |

| TetR | Tetracycline | Repressor | E. coli | Dynamic regulation, gene circuit control [9] |

| Phenolic Acid-responsive TFs | Protocatechuic acid, others | Activator | E. coli, P. putida | High-throughput screening of enzyme variants [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Implementation

Protocol: Construction and Validation of a Novel TFB

This protocol outlines the steps for developing and testing a new transcription factor-based biosensor, applicable to both activator and repressor systems.

Part Identification and Selection:

- Transcription Factor (TF): Identify a TF that responds to your ligand of interest. This can be done by mining databases like RegulonDB, P2TF, or PRODORIC (see The Scientist's Toolkit) [9] [10]. If a native TF is unavailable, explore homologous TFs from other species or employ directed evolution to alter the specificity of an existing TF [9] [4].

- Promoter: Identify the cognate promoter sequence containing the specific TF binding site (TFBS). The promoter's core strength (weak for activators, strong for repressors) is a key design consideration [11].

- Reporter Gene: Select a reporter gene suitable for high-throughput screening, such as GFP (fluorescence), LacZ (colorimetry), or an antibiotic resistance gene.

Genetic Circuit Assembly:

- Assemble the genetic circuit in your desired host chassis (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae). The standard architecture is: TF gene (constitutively expressed) + Cognate promoter → Reporter gene.

- The TF can be expressed on the same plasmid as the reporter or on a separate plasmid. Ensure the TF gene is under a constitutive promoter with appropriate strength to avoid toxicity or insufficient sensing.

Characterization and Parameterization:

- Cultivation: Grow multiple cultures of the biosensor strain, each exposed to a different, defined concentration of the ligand.

- Measurement: Measure the output signal (e.g., fluorescence) and the cell density (OD600) for each culture during the mid-exponential growth phase.

- Data Analysis: Normalize the output signal to cell density. Plot the normalized output against the ligand concentration and fit the data to the Hill equation to determine the dynamic range, EC50/IC50, and other key parameters [13] [4].

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of Enzyme Variants

This methodology leverages a biosensor to screen a library of enzyme variants for improved activity [13].

- Library Creation: Generate a diverse library of enzyme variants, for example, via error-prone PCR or site-saturation mutagenesis of a key pathway enzyme.

- Biosensor Coupling: Co-express or transform the enzyme variant library into the host strain containing the biosensor circuit. The biosensor must be designed to detect the product of the enzymatic reaction.

- Screening and Sorting:

- Incubate the library to allow enzyme expression and metabolite production.

- Use a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) to isolate cells exhibiting the highest fluorescence intensity, indicating high product concentration and thus high enzyme activity.

- Validation: Isolate the sorted cells, recover them, and validate the performance of the enriched enzyme variants using more precise, low-throughput methods like HPLC.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, databases, and tools essential for research on transcription factor-based biosensors.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for TFB Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Description | Example Sources / Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Allosteric Transcription Factors (aTFs) | Core sensing component; binds ligand and regulates DNA binding. | Families: TetR, LysR, AraC [9]. Sources: Native hosts, metagenomic mining [10]. |

| Cognate Promoters | DNA part containing the TF binding site; controls reporter/output gene expression. | Identified via genomic studies; often sourced from the same operon as the native TF [13]. |

| Reporter Genes | Generates measurable output (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence). | GFP, RFP, LacZ, Luciferase [8] [13]. |

| TF and Promoter Databases | Curated repositories for identifying and characterizing TF-promoter pairs. | RegulonDB (E. coli), P2TF (Prokaryotes), JASPAR (TF binding profiles) [9] [10]. |

| Computational Prediction Tools | AI and bioinformatics tools for predicting new TFs, optimizing circuits, and modeling. | DeepTFactor (TF prediction), Cello (genetic circuit design), AlphaFold (protein structure prediction) [10] [8]. |

| Directed Evolution Platforms | Methods to engineer TFs with altered ligand specificity or improved performance. | Error-prone PCR, site-directed mutagenesis, and high-throughput screening [9] [4]. |

Both activator-based and repressor-based systems offer distinct advantages for constructing dynamic regulatory networks in synthetic biology. The choice between them is not merely binary but depends on the specific application, desired performance metrics, and host context. Activators are often preferred for tightly controlled, inducible expression from weak promoters, while repressors are powerful for turning off constitutive expression in response to metabolic signals. Future research will focus on expanding the library of well-characterized TFs, refining engineering strategies to minimize cross-talk and leakiness, and integrating multiple sensory modalities. The continued development of these sophisticated genetic control systems, powered by computational design and AI, is fundamental to advancing dynamic regulation research and the efficient production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and other high-value chemicals [14] [8] [4].

Transcription factor-based biosensors (TFBs) are indispensable tools in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, enabling real-time monitoring of metabolites and dynamic control of metabolic pathways. Their performance in these roles is governed by three core quantitative metrics: sensitivity, dynamic range, and specificity [15]. Optimizing these parameters is critical for developing robust biosensors capable of precise, high-throughput screening and reliable regulation in complex biological systems [3] [4]. This guide details the definition, measurement, and enhancement of these key metrics for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Performance Metrics Explained

The performance of a transcription factor-based biosensor is typically characterized by its dose-response curve, which plots the output signal (e.g., fluorescence) against the input ligand concentration [3] [4]. Key metrics are derived from this curve to form a complete performance profile.

Table 1: Definition and Significance of Core TFB Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | Formal Definition | Interpretation on Dose-Response Curve | Impact on Biosensor Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity [15] | The concentration change of a metabolite required to produce a measurable change in the biosensor's output signal. | The steepness of the curve's linear phase; a steeper slope indicates higher sensitivity. | Determines the ability to detect subtle fluctuations in metabolite levels; crucial for fine dynamic regulation. |

| Dynamic Range [1] [15] | The fold-change between the maximal output signal (at saturating ligand) and the minimal basal signal (without ligand). | The difference between the upper and lower plateau of the sigmoidal curve. | Defines the resolution for distinguishing high-performing microbial strains and the amplitude of regulatory output. |

| Specificity [15] | The difference in output signal intensity upon binding the target ligand compared to alternative, non-target ligands. | Measured by comparing dose-response curves for the target ligand versus structural analogs. | Reduces false positives in screening and ensures the biosensor responds only to the intended metabolic signal. |

Other critical metrics include the operating range (the concentration window of effective operation) and the response time (the speed to reach half-maximal output) [3]. The limit of detection (LoD) is also a key parameter, representing the lowest ligand concentration that can be reliably distinguished from background noise [1].

Quantification and Experimental Protocols

Accurately quantifying these metrics requires standardized experimental workflows and data analysis.

Standardized Measurement Workflow

A general protocol for characterizing TFB performance involves the following steps [10] [16]:

- Strain Preparation: Clone the biosensor genetic circuit (TF, promoter, reporter gene) into the host microbial chassis.

- Culture and Induction: Grow cultures and expose them to a defined concentration gradient of the target ligand. A minimum of eight data points across the expected concentration range is recommended [15].

- Signal Measurement: In the log or early stationary phase, measure the output signal (e.g., fluorescence intensity, luminescence) for each culture using a plate reader.

- Data Normalization: Normalize the output signal (e.g., fluorescence) to cell density (e.g., OD₆₀₀) to account for growth effects.

- Curve Fitting: Plot the normalized output against the ligand concentration and fit the data to a Hill equation model [4]:

Output = Minimum + (Maximum - Minimum) * [Ligand]^nH / (K^nH + [Ligand]^nH)where:Minimumis the basal signal level.Maximumis the saturated signal level.Kis the ligand concentration at half-maximal output (an indicator of affinity).nHis the Hill coefficient, describing cooperativity.

Quantification from the Dose-Response Curve

After curve fitting, the key metrics are calculated as follows:

- Dynamic Range:

Maximum / Minimum[15]. - Sensitivity: The

Kvalue and thenH(Hill coefficient) together describe the sensitivity and sharpness of the response [15]. - Specificity: Determine the dynamic range for the target ligand and several structurally similar molecules. A biosensor with high specificity will show a significantly higher dynamic range for its intended target [15].

Engineering Strategies for Performance Enhancement

Native TFBs often require optimization for practical application. The following strategies enable fine-tuning of sensitivity, dynamic range, and specificity.

Table 2: Engineering Strategies for Optimizing TFB Performance

| Target Metric | Engineering Strategy | Specific Method | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity & Dynamic Range | Promoter Engineering [15] | Vary the strength of the promoter controlling the reporter gene or the TF itself. | Alters the number of output molecules or TF abundance, directly affecting signal amplitude and background noise. |

| RBS Tuning [4] [15] | Modify the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) sequence upstream of the TF or reporter gene. | Fine-tunes the translation efficiency, controlling the intracellular concentration of the TF and the reporter protein. | |

| Operator Site Modification [15] | Mutate the transcription factor binding site (TFBS or operator) on the promoter. | Alters the binding affinity of the TF for the DNA, which changes the basal expression level and induction threshold. | |

| Plasmid Copy Number [4] | Use plasmids with different origins of replication. | Varies the gene dosage of the biosensor components, impacting the absolute number of sensors per cell. | |

| Specificity | TF Ligand-Binding Domain Engineering [1] [15] [16] | Use directed evolution or rational design to mutate residues in the TF's ligand-binding pocket. | Reshapes the binding pocket to sterically hinder non-target ligands or create new favorable interactions with the target. |

| Chimeric TF Construction [3] | Fuse the DNA-binding domain of one TF with the ligand-binding domain of another. | Creates novel biosensors with hybrid functions, combining the DNA recognition of one TF with the sensing capability of another. |

Advanced high-throughput platforms like Sensor-seq are revolutionizing TFB engineering. This method uses RNA barcoding and deep sequencing to simultaneously quantify the performance (F-score) of thousands of TtgR protein variants in response to various ligands, efficiently identifying rare variants with desired specificity and dynamic range [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Developing and applying high-performance TFBs relies on a suite of core reagents and methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for TFB Research

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor R&D |

|---|---|---|

| Model Transcription Factors | TetR, AraC, TrpR, TtgR, LuxR [10] [16] | Well-characterized scaffolds for engineering new biosensors; their structural and functional data provide a starting point for design. |

| Reporter Genes | GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein), RFP (Red Fluorescent Protein), Luciferase, Enzymatic Reporters (e.g., LacZ) [1] [10] | Generate a quantifiable output signal (optical, luminescent, colorimetric) that is linked to ligand concentration. |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Flow Cytometry, Microfluidics, Sensor-seq [1] [16] | Enable the sorting and analysis of vast libraries of microbial variants to isolate those with superior biosensor performance. |

| Computational & AI Tools | Cello (Genetic Circuit Design), DeepTFactor (TF Prediction), AlphaFold (Protein Structure Prediction) [1] [10] | Facilitate in silico design, optimization, and prediction of biosensor components and their interactions before experimental testing. |

| Directed Evolution Techniques | Error-prone PCR, Site-saturation mutagenesis [15] [16] | Create diverse libraries of TF mutants to evolve novel ligand specificity, sensitivity, and improved dynamic range. |

| Fen1-IN-6 | Fen1-IN-6, MF:C12H8N2O5S2, MW:324.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Wee1-IN-6 | Wee1-IN-6, MF:C45H52FN11O4, MW:830.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application in Dynamic Regulation and Screening

Optimizing these metrics is not an academic exercise; it directly enables advanced applications in metabolic engineering.

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): A large dynamic range is critical for efficiently separating high-producing cells from low-producers in large libraries [1] [4]. For example, TFBs for biofuels like butanol or fatty acid-derived products have been used to screen strain libraries, identifying mutants with significantly improved titers [4].

- Dynamic Metabolic Regulation: Biosensors can be designed to automatically downregulate competitive pathways or upregulate bottleneck enzymes when a key intermediate accumulates [3] [4]. The sensitivity and response time of the biosensor determine how quickly and effectively the metabolic flux can be rebalanced, leading to increased product yields and robustness in scaled-up fermentations [3] [15].

In conclusion, a deep understanding and systematic optimization of sensitivity, dynamic range, and specificity are fundamental to harnessing the full potential of transcription factor-based biosensors. Through strategic engineering and the use of advanced screening and computational tools, researchers can develop precision tools that drive innovation in drug development, bio-based chemical production, and fundamental biological research.

The journey to understanding and engineering cellular control began with the seminal study of the lac operon in E. coli. This system provided the first model for inducible gene regulation, demonstrating how a transcription factor (LacI) could repress a set of genes (lacZYA) in the absence of its inducer (allolactose or the synthetic analog IPTG). Upon inducer binding, LacI undergoes a conformational change, dissociates from the operator site, and allows transcription to proceed [17]. This fundamental "on/off" switch mechanism, governed by the interaction between a transcription factor (TF), a small molecule, and DNA, established the core principle upon which the entire field of synthetic biology would later build. The quest to move from observing this natural system to deliberately engineering it for predefined purposes forms the historical arc that has led to the development of sophisticated transcription factor-based biosensors (TFBs) for dynamic regulation. These biosensors are genetically encoded devices that use transcription factors to convert the intracellular concentration of a specific metabolite into a measurable output, enabling real-time monitoring and control of biological processes [9] [4].

From Natural System to Engineering Framework

The lac operon is more than a biological concept; it is a functional module that can be extracted and repurposed. Synthetic biology, inspired by engineering disciplines, sought to standardize and simplify such biological parts to make them predictable and reliable [18]. The lac system's components—the LacI repressor, its operator sequence, and the inducible promoter—became the first standardized parts in the synthetic biology toolkit.

Early engineering efforts revealed the system's complexity. A theoretical model of a simple regulatory region with three activator binding sites requires accounting for at least eight possible states and nine unique molecular parameters [18]. To make this complexity manageable, synthetic biologists adopted a reductionist approach, systematically simplifying systems to distill them to their essential features. This philosophy of "bending nature to understand it" enabled a predictive understanding of biological processes [18].

Table 1: Evolution from Natural Operon to Engineered Biosensor

| Feature | Natural Lac Operon | Modern Engineered TFB |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Negative inducible genetic switch | Programmable molecular sensor-actuator |

| Primary Function | Metabolic adaptation to carbon source | Dynamic pathway control, high-throughput screening, metabolite detection |

| Key Components | LacI, allolactose, native pLac promoter | Engineered TFs, novel ligands, synthetic promoters & RBSs |

| Typical Output | Metabolic enzymes for lactose digestion | Fluorescent proteins, enzymes for colorimetric change, survival markers |

| Tunability | Limited by natural evolution | Highly tunable via promoter strength, RBS engineering, and TF engineering |

| Application Scope | Single-organism metabolism | Cross-species, cell-free systems, multi-input logic gates |

The conceptual leap from the natural operon to an engineered biosensor is summarized in Table 1. The modern TFB is a modular device comprising a sensing component (the transcription factor) and a reporting component (a promoter controlling a reporter gene) [9]. The fundamental operational logic, however, remains unchanged from the lac paradigm: a small molecule binds to a TF, inducing a conformational change that alters its DNA-binding affinity, thereby regulating downstream gene expression [8].

Figure 1: Core Mechanism of a Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor. The binding of a specific inducer molecule causes a conformational change in the transcription factor, altering its ability to bind DNA and regulate the expression of a reporter gene.

Engineering and Optimizing Biosensor Performance

Wild-type transcription factors like LacI rarely possess the optimal characteristics for applied biosensing. A primary challenge in the field is the limited number of known metabolite-activated TFs compared to the vast number of compounds amenable to biomanufacturing [9] [10]. Consequently, significant research focuses on engineering and optimizing TFBs to enhance their performance for specific tasks. Key performance metrics include:

- Dynamic Range: The fold difference between the fully induced ("ON") and uninduced ("OFF") output states [4] [8].

- Sensitivity: The lowest concentration of ligand that elicits a detectable response, often defined by the EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration) [4].

- Specificity: The ability to distinguish the target ligand from structurally similar molecules [4].

- Operating Range: The concentration window over which the biosensor response is linear [9].

Table 2: Key Engineering Strategies for Optimizing Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

| Engineering Target | Strategy | Purpose & Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor (TF) | Directed evolution & protein engineering [9] [16] | Alter ligand specificity, improve sensitivity, or reduce cross-talk. |

| TF Structure | Rational design of ligand-binding domain [4] | Modulate affinity for the target ligand and allosteric control. |

| Promoter & Operator | Mutagenesis of TF binding site (operator) [8] | Fine-tune the binding affinity of the TF, altering leakiness and dynamic range. |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) | Library-based screening of RBS variants [4] | Optimize translation efficiency of the reporter protein to maximize output signal. |

| Genetic Context | Modulation of plasmid copy number [4] | Balance gene dosage effects to prevent cellular burden and maintain sensitivity. |

| Circuit Architecture | Incorporation of genetic amplifiers [4] | Amplify the output signal, thereby increasing the dynamic range and sensitivity. |

Engineering a TFB requires a holistic approach, as summarized in Table 2. For instance, the TF itself can be engineered through directed evolution. A groundbreaking approach, Sensor-seq, enables highly multiplexed design of allosteric transcription factors for new ligands. This method involves creating vast libraries of TF variants (e.g., 17,737 variants of TtgR) and using RNA barcoding and deep sequencing to quantitatively measure the ligand-induced response (F-score) of each variant in a high-throughput manner [16]. This platform has successfully created biosensors for non-native ligands like the opiate analog naltrexone and the antimalarial drug quinine [16].

Experimental Workflow for Biosensor Development and Validation

The development of a functional biosensor follows a structured pipeline from part identification to performance characterization. The workflow can be broken down into several key stages, as illustrated below and detailed in the accompanying protocol.

Figure 2: Generalized Workflow for Biosensor Construction and Testing.

Protocol: Construction and Characterization of a Phenolic Acid Biosensor

This protocol is adapted from a study that developed biosensors for eleven different phenolic acids [13].

1. Part Identification & Library Design:

- Objective: Identify a transcription factor and its cognate promoter that respond to a target molecule (e.g., a phenolic acid).

- Method:

- Perform a multi-genome bioinformatic screen to identify potential TF-promoter pairs. Key databases include RegulonDB (for E. coli), RegPrecise (for prokaryotes), and P2TF [9] [13].

- Design a genetic library if engineering is required. For a novel ligand, use a platform like Sensor-seq [16]: select a promiscuous aTF scaffold (e.g., TtgR), generate a library of sequence variants via phylogeny-guided diversification, and clone them into a screening construct that links each variant to a unique RNA barcode.

2. Genetic Circuit Construction:

- Objective: Assemble the biosensor circuit in an appropriate plasmid vector.

- Method:

- Clone the identified inducible promoter upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., for fluorescent protein like RFP or GFP) [13].

- Ensure the gene for the cognate transcription factor is also present in the system, typically expressed constitutively from a separate promoter.

- The final plasmid is the "screening construct" used for transformation.

3. Host Transformation & Cultivation:

- Objective: Introduce the biosensor construct into the host chassis.

- Method:

- Transform the plasmid into model bacterial hosts such as Escherichia coli, Cupriavidus necator, or Pseudomonas putida [13].

- Plate transformed cells on selective media and incubate to obtain single colonies.

- Inoculate liquid cultures from single colonies and grow to the desired cell density (typically mid-log phase) under appropriate conditions.

4. Induction Assay & High-Throughput Screening:

- Objective: Measure the biosensor's response to a range of ligand concentrations.

- Method:

- For a characterized biosensor: Distribute cell cultures into a multi-well plate. Add a gradient of the target ligand (e.g., phenolic acids, naltrexone, quinine) to different wells, including a no-ligand negative control. Incubate for a defined period to allow gene expression [13].

- For a large variant library (Sensor-seq): Pool the entire library of clones. Split the culture and dose with either the target ligand or a vehicle control. Harvest samples during log-phase growth for RNA extraction and plasmid DNA isolation [16].

5. Data Acquisition & Analysis:

- Objective: Quantify the output and calculate performance metrics.

- Method:

- For fluorescent reporters: Use a plate reader to measure fluorescence intensity. Normalize fluorescence to cell density (OD600) [13].

- For Sensor-seq: Prepare cDNA from total RNA and sequence it along with the plasmid DNA library. Map each TF variant to its output via the unique barcode. Calculate an F-score for each variant: the normalized ratio of reporter transcript levels in the presence vs. absence of ligand [16].

- Plot dose-response curves (output vs. ligand concentration) and fit with the Hill equation to determine key parameters like dynamic range, EC50, and Hill coefficient [4].

6. Iterative Optimization:

- Objective: Improve biosensor performance based on initial characterization data.

- Method:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TFB Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Model Chassis | Host organism for biosensor construction and testing. | E. coli BL21, Pseudomonas putida, Cupriavidus necator; chosen for genetic tractability and application context [13]. |

| Reporter Genes | Provides a measurable output signal linked to TF activity. | Fluorescent Proteins (GFP, RFP), Enzymes (XylE, LacZ), RNA Aptamers (Mango III) [13] [17]. |

| Database Resources | In silico source for identifying native TF-promoter pairs. | RegulonDB, RegPrecise, P2TF, JASPAR [9]. |

| Screening Platform | High-throughput method for identifying functional biosensors from large variant libraries. | Sensor-seq: uses RNA barcoding and deep sequencing [16]. FACS: for screening based on fluorescence [19]. |

| Cell-Free Systems | Simplified, rapid prototyping environment bypassing cell walls and complex physiology. | Freeze-dried crude extracts (e.g., from E. coli); enable biosensing by just adding water, DNA, and the ligand [14] [17]. |

| Directed Evolution Tools | Methods to generate genetic diversity in TF sequences for new functions. | Error-prone PCR, Site-saturation mutagenesis, DNA shuffling [9] [16]. |

| Vem-L-Cy5 | Vem-L-Cy5, MF:C63H68F5N7O9S, MW:1194.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Liproxstatin-1-15N | Liproxstatin-1-15N|Ferroptosis Inhibitor | Liproxstatin-1-15N is a potent N-15 labeled ferroptosis inhibitor for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology

The transition of TFBs from research tools to core components in engineering biology is most evident in their applications. A primary use case is in high-throughput screening (HTS) for metabolic engineering. TFBs can be used to screen vast libraries of engineered microbes to identify rare, high-producing variants. By linking the production of a desired metabolite (e.g., an advanced biofuel) to the expression of a fluorescent reporter, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) can be used to isolate top producers from a population of millions of cells [4] [19].

Beyond screening, TFBs enable dynamic metabolic regulation. In this approach, a biosensor detecting an intermediate metabolite automatically upregulates or downregulates key pathway enzymes to balance metabolic flux. This creates a self-regulating cell factory that optimizes production in real-time, overcoming the limitations of static engineering strategies [9] [4]. For example, a TFB for a key intermediate can be designed to downregulate a competing pathway, thereby redirecting carbon flux toward the desired product [4].

Furthermore, the utility of TFBs extends into environmental and clinical monitoring. Engineered biosensors for specific molecules, such as the opiate naltrexone or the antimalarial quinine, can be deployed in cell-free systems for diagnostic purposes [16]. These systems, often lyophilized for stability, function as low-cost, field-deployable sensors for contaminants or health biomarkers [17].

The field of transcription factor-based biosensors is poised for transformative growth, driven by several emerging trends. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning is accelerating the design process. Tools like DeepTFactor predict new transcription factors from sequence data, while platforms like Sensor-seq generate large datasets ideal for training models to predict the functional outcomes of specific mutations, moving the field toward predictive biosensor design [14] [9] [10].

There is also a strong push toward applying these tools in non-model organisms and complex consortia, which may be more robust for industrial bioprocesses [14]. Finally, the use of cell-free systems is democratizing access to synthetic biology and enabling the creation of portable, shelf-stable biosensors for applications ranging from education to point-of-care diagnostics [14] [17].

In conclusion, the path from the Lac operon to modern synthetic biology represents a profound shift from observation to mastery. The simple switch discovered in E. coli has been deconstructed, understood, and rebuilt into a versatile engineering paradigm. Today's TFBs are sophisticated devices capable of sensing, computing, and actuating within living cells, enabling unprecedented control over biological systems for manufacturing, medicine, and environmental sustainability. As our ability to design and optimize these biological tools continues to improve, their impact on science and technology is bound to deepen, firmly establishing synthetic biology as a predictive engineering discipline.

Engineering and Deploying Biosensors: From Laboratory Design to Real-World Solutions

The engineering of genetic circuits represents a cornerstone of synthetic biology, enabling the programming of living cells to perform complex functions, from bio-based chemical production to advanced therapeutic applications [20]. These circuits require the precise integration of core components—promoters, operators, and reporter genes—to process biological information and generate measurable outputs. Within the broader research context of transcription factor-based biosensors for dynamic regulation, the construction of reliable genetic circuits is paramount [10]. Such biosensors, which often utilize allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) to detect specific metabolites and elicit a programmed response, depend on well-characterized genetic parts to function predictably inside living cells [10]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the fundamental principles and methodologies for constructing these circuits, framing them as essential enabling technologies for the development of sophisticated biosensing and regulatory systems.

Core Components of Genetic Circuits

Promoters

Promoters are DNA sequences where RNA polymerase binds to initiate transcription. In synthetic biology, both constitutive and inducible promoters are used. Inducible promoters are particularly valuable for biosensor applications, as their activity can be regulated by specific transcription factors that, in turn, respond to effector molecules [20] [10]. The strength of a promoter, determined by its -35 and -10 box sequences, dictates the baseline and maximum levels of gene expression, which must be carefully balanced for a circuit to function as intended [20].

Operators

Operators are short DNA sequences that serve as binding sites for transcription factor (TF) proteins. When a TF binds to its operator, it can either activate or repress transcription from an adjacent promoter. In the context of biosensors, allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) undergo a conformational change upon binding a specific ligand (e.g., a small molecule metabolite), which alters their ability to bind DNA and thereby regulates gene expression [10]. The precise number, type, and arrangement of operator sites in a regulatory region is a key determinant of the logical operation (e.g., AND, NOT) performed by the circuit [21].

Reporter Genes

Reporter genes produce a measurable output that correlates with the activity of a genetic circuit. The Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) is a widely used reporter that allows for quantitative measurement of gene expression using fluorometry [21]. The choice of reporter is critical, as its degradation rate and expression level can impact the ability to accurately measure circuit dynamics [20].

Table 1: Core Components of a Genetic Circuit

| Component | Function | Key Characteristics | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter | Initiates transcription by recruiting RNA polymerase. | Defined by -35/-10 sequences; can be constitutive or inducible. | Placq (constitutive), luxpR (inducible) [21] |

| Operator | Protein-binding site for transcriptional regulation. | Specific DNA sequence recognized by a transcription factor. | LacI operator, LuxR activator binding site [21] |

| Reporter Gene | Encodes a measurable output for monitoring circuit activity. | Must produce a quantifiable signal (e.g., fluorescence). | Green Fluorescent Protein (gfp) [21] |

Figure 1: Information flow in a TF-based biosensor. An effector molecule binds a transcription factor, which then interacts with an operator to regulate promoter activity and reporter gene output.

Genetic Circuit Design and Function

The design of genetic circuits involves the strategic interconnection of promoters, operators, and coding sequences to create a desired logical function. A foundational goal is to establish a common signal carrier, such as RNA polymerase flux controlled by promoters, which simplifies the connection of smaller circuits into larger, more sophisticated systems [20]. Circuit dynamics are profoundly influenced by the chosen regulatory molecules, which can include DNA-binding proteins, invertases, and CRISPR-based systems [20].

Regulator Classes for Circuit Design

- DNA-Binding Proteins: These are the most common regulators, including repressors like LacI and TetR, and activators. They function by binding to specific operator sequences to either block (repress) or recruit (activate) RNA polymerase [20]. Simple NOT and NOR logic gates can be built using repressible promoters, while AND gates have been constructed using activators that require chaperones or split proteins [20].

- CRISPRi/a: Catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) can be fused to repressor or activator domains and targeted to specific DNA sequences via guide RNAs. This system offers high designability, as the targeting is determined by an RNA sequence, allowing for a large set of orthogonal regulators [20].

- Invertases: These are site-specific recombinases that permanently invert DNA segments between binding sites. They are ideal for building memory circuits, as the flipped state is maintained without continuous energy input [20].

Construction of a Genetic AND Gate: A Case Study

This section details a specific experimental methodology for constructing a genetic AND gate, demonstrating the assembly of core components to create a Boolean logic function within a cell [21].

Experimental Protocol

1. Plasmid Design and Standardization:

- A reporter plasmid (

pSB-GFP) is used, which contains a promoterlessgfpgene. - The regulatory region upstream of

gfpis standardized to include an upstream multi-cloning site (for promoter parts) and a downstream standard region designed for the sequential insertion of operator parts using specific restriction enzymes (BglIIandMluI).

2. Assembly of Operator Parts:

- An operator part is synthesized as a DNA module flanked by

BamHIandMluIrestriction sites. TheBamHIsticky end is compatible with theBglIIsite on the plasmid. - The operator part is ligated into the

BglII/MluI-digested plasmid. This ligation destroys the originalBglIIsite but leaves a newBglIIsite on the inserted part, allowing for the repeated insertion of additional operator parts using the same procedure.

3. Circuit Construction:

- A constitutive promoter part (

Placq) is first inserted into the upstream multi-cloning site to createPlacq-GFP. - To build a LacI-repressed gate, a single

LacIoperator part is inserted into the downstream standard region, creatingPlacq-LacI-GFP. A version with two operators (Placq-LacItandem-GFP) is also constructed for stronger repression. - To build a LuxR-activated gate, a

LuxRoperator part (containing aluxpRpromoter, a LuxR-binding site, and aLuxRexpression cassette) is assembled. - Finally, the AND gate (

PLuxR-LacItandem-GFP) is constructed by inserting the twoLacIoperator parts into the downstream standard region of thePLuxR-GFPplasmid.

4. Reporter Assay and Validation:

- Each constructed plasmid is transformed into an E. coli strain expressing

LacI(e.g.,DH5αLacI). - Transformed cells are grown in culture with different combinations of inducers: Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for LacI and N-(β-ketocaproyl)-DL-homoserine lactone (AHL) for LuxR.

- After a suitable incubation period, GFP fluorescence is measured using a fluorometer. Fluorescence intensity is normalized to cell density.

- A functional AND gate will show high fluorescence output only in the presence of both IPTG and AHL.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| pSB-GFP Plasmid | Backbone vector with promoterless GFP reporter gene [21]. |

| Operator Parts | Standardized DNA modules containing protein-binding sites (e.g., for LacI, LuxR) [21]. |

| Restriction Enzymes | Molecular tools for digesting DNA at specific sequences for assembly (e.g., BglII, MluI, BamHI) [21]. |

| E. coli DH5αLacI | Host cell strain that provides the LacI repressor protein for inducible system function [21]. |

| Inducers (IPTG, AHL) | Small molecules that trigger the biosensor by binding to and altering their respective transcription factors [21]. |

| Fluorometer | Instrument for quantifying the output signal (GFP fluorescence) from the genetic circuit [21]. |

Figure 2: Genetic AND gate logic. Only when AHL activates LuxR AND IPTG inactivates LacI repression does transcription of GFP occur.

Expected Results and Analysis

In the case study [21], the constructed AND gate (PLuxR-LacItandem-GFP) exhibited the following behavior:

- No Inducers: Background fluorescence.

- IPTG Only: Low fluorescence (LacI repression is lifted, but LuxR is not activated).

- AHL Only: Low fluorescence (LuxR is activated, but LacI repression blocks transcription).

- IPTG and AHL: High fluorescence (5.7-fold increase over background), as both repression is lifted and activation occurs.

This result confirms the successful integration of two biological inputs into a single transcriptional output via the modular assembly of standardized operator parts.

Advanced Applications in Biosensing and Dynamic Regulation

The construction of basic logic gates provides the foundation for developing advanced transcription factor-based biosensors. These biosensors are crucial tools for two primary applications in synthetic biology: screening and dynamic regulation [10].

Screening Production Strains: Biosensors can be designed to detect and respond to the intracellular accumulation of a desired product, such as a bio-based chemical. A biosensor circuit can be linked to a reporter gene like GFP, allowing researchers to use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to identify and isolate high-producing microbial strains from a library [10].

Dynamic Regulation of Metabolic Pathways: Biosensors enable dynamic control strategies within engineered cells. Instead of constitutively expressing all enzymes in a metabolic pathway, a biosensor can detect an intermediate metabolite's buildup. This signal can then trigger the expression of downstream enzymes, automatically balancing metabolic flux to maximize product yield and minimize the accumulation of toxic intermediates [10].

The reliability of these advanced applications hinges on the precise construction and predictable performance of the underlying genetic circuits, underscoring the necessity for robust design principles, well-characterized parts, and standardized assembly methods [20] [10].

The engineering of biological systems for applications in therapeutics, diagnostics, and bioproduction relies heavily on the precise control of gene expression. Within the specific context of transcription factor (TF)-based biosensors, dynamic regulation has emerged as a critical capability for advancing metabolic engineering and synthetic biology [14] [10]. These biosensors, which convert the presence of a target metabolite into a measurable genetic output, enable real-time monitoring and control of biosynthetic pathways, thereby overcoming limitations in natural product yield [14]. The performance and evolutionary longevity of these systems are governed by two fundamental layers of control: transcriptional and translational.

Transcriptional control operates at the level of RNA synthesis, where transcription factors and promoters regulate when and how frequently a gene is transcribed. Translational control, in contrast, acts at the protein synthesis level, fine-tuning the efficiency with which mRNA is translated into functional protein, often through mechanisms involving ribosome binding sites, small RNAs, and upstream open reading frames (uORFs) [22]. While transcriptional control provides the primary on/off switch for gene expression, translational regulation offers a faster, more direct means to modulate protein output, which is crucial for rapid cellular adaptation [22]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the core strategies for tuning both transcriptional and translational processes, with a specific focus on their application in TF-based biosensors for dynamic regulation research.

Transcriptional Control Strategies

Transcriptional control forms the foundational layer of genetic regulation in engineered biosensors. It encompasses the suite of mechanisms that regulate the initiation and rate of transcription, primarily through the interaction of transcription factors with specific DNA sequences.

Allosteric Transcription Factors (aTFs) and Their Engineering

Allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) are proteins that undergo conformational changes upon binding to specific small molecules (ligands), which in turn alters their affinity for operator DNA sequences and modulates downstream gene expression [10]. This inherent switching mechanism makes them ideal sensing components for synthetic genetic circuits. The design space for aTFs includes several modes of action: repression of activator aTF, activation of repressor aTF, repression of repressor aTF, or activation of activator aTF [10].

A significant challenge in biosensor engineering is the limited number of natural aTFs relative to the vast array of compounds targeted for detection. To address this constraint, several advanced engineering strategies have been developed:

- Sensor-seq Platform: This high-throughput method designs aTFs to sense non-native ligands. It involves creating vast libraries of aTF variants (e.g., 17,737 variants of TtgR) and screening them against target ligands using RNA barcoding and deep sequencing to quantify ligand-induced responses (F-score) [16]. This platform successfully created biosensors for diverse ligands, including the opiate analog naltrexone and the antimalarial drug quinine.

- Structure-Guided Design: Computational tools, including molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, guide the rational design of artificial TFs. For instance, a progesterone biosensor was designed by fine-tuning the linker between the DNA-binding domain (QFDBD) and activation domain (QFAD) to achieve the desired conformational change upon ligand binding [23].

- Homology and AI-Based Prediction: Bioinformatics approaches leverage known transcriptional regulator families (e.g., LysR, TetR, AraC) to discover new aTFs through sequence homology in genomic and metagenomic databases [10]. Furthermore, artificial intelligence tools like DeepTFactor predict novel TFs from sequence data, expanding the discoverable space of potential biosensors [10].

Promoter Engineering and Synthetic Promoters

The promoter region is a critical determinant of transcriptional activity and specificity. Engineering these regions allows for fine-tuning of biosensor performance characteristics, such as dynamic range, leakiness, and host compatibility.

- Synthetic Promoter Design: The creation of entirely synthetic promoters, such as the promoter QT (composed of QUAS, a 10-bp spacer, and a T7 promoter), enables precise control over transcription initiation by designed artificial TFs [23].

- Operator Sequence Modification: Altering the operator sequences to which aTFs bind can significantly impact the binding affinity of the TF and, consequently, the repression or activation strength of the promoter. This is a key parameter for tuning the transfer function of the biosensor.

- Library-Based Screening: Generating diversified promoter libraries through mutagenesis of core promoter elements allows for the experimental screening and selection of variants with desired expression levels and induction profiles.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Transcriptional Biosensor Performance

| Metric | Description | Typical Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | The ratio of output signal in the presence of a saturating ligand concentration to the output signal in its absence (basal expression). | Flow cytometry, microplate reader (e.g., GFP fluorescence). |

| ECâ‚…â‚€ / ICâ‚…â‚€ | The effective concentration of ligand that induces 50% of the maximum activation or repression. | Dose-response curve with ligand titration. |

| Sensitivity (LOD) | The lowest concentration of ligand that produces a detectable output signal significantly above the background noise. | Limit of Detection (LOD) calculation from dose-response data. |

| F-score | A normalized ratio of reporter transcript levels with and without ligand, used in high-throughput screens like Sensor-seq [16]. | RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). |

| Half-life (Ï„â‚…â‚€) | The time taken for the population-level functional output of a circuit to fall by 50% due to evolutionary degradation [24]. | Long-term growth and measurement assays (e.g., over serial passaging). |

Experimental Protocol: Sensor-seq for High-Throughput aTF Screening

The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing the Sensor-seq platform to identify aTF variants responsive to new ligands [16].

- Library Construction: Clone a diversified library of aTF variants (e.g., via site-saturation mutagenesis) into a screening plasmid. Each variant is placed in cis with a randomized 16-nucleotide barcode, separated by a constant region containing the aTF's native promoter driving a reporter transcript.

- Ligand Exposure and Cell Harvesting: Transform the pooled plasmid library into the host organism (e.g., E. coli). Grow separate cultures dosed with the target ligand and a vehicle control. Harvest cells during the log-phase growth for both total RNA and plasmid DNA extraction.

- RNA Sequencing and Mapping Genotype to Phenotype:

- RNA-seq: Prepare cDNA from the total RNA and sequence it to quantify the abundance of each reporter barcode transcript, which reflects the activity of the corresponding aTF variant under the given condition.

- Genotype-Barcode Linkage: Use PCR and Golden Gate Assembly to physically link each aTF variant sequence in the plasmid DNA to its associated barcode. Sequence these constructs to create a mapping between every variant and its barcode(s).

- Data Analysis and F-score Calculation: For each variant, calculate the F-score using the formula:

F-score = (Normalized cDNA count with ligand) / (Normalized cDNA count without ligand)Normalization is performed using the plasmid DNA counts for each barcode. Variants with an F-score significantly greater than 1 are considered functional biosensors for the target ligand.

Translational Control Strategies

While transcriptional control initiates gene expression, translational regulation provides a faster, more direct layer of tuning that determines the final protein output from an mRNA transcript. This post-transcriptional control is crucial for rapid adaptive responses and for minimizing the metabolic burden associated with transcription, thereby enhancing the evolutionary stability of genetic circuits [24] [22].

Mechanisms of Translational Regulation

Translational regulation fine-tunes protein synthesis at several key stages:

- Initiation Control: This is the most critical rate-limiting step. Efficiency is primarily governed by the affinity of the ribosome binding site (RBS) for the ribosome, the secondary structure of the mRNA around the start codon, and the availability of initiation factors [22]. Engineering the RBS sequence is a primary method for tuning translation initiation and, consequently, protein expression levels.

- Small RNA (sRNA) Mediated Control: Small RNAs can act as post-transcriptional regulators by base-pairing with target mRNAs, which can block ribosome access or promote mRNA degradation. In synthetic biology, sRNAs are exploited in post-transcriptional controllers that silence circuit RNA. These controllers have been shown to outperform transcriptional controllers in extending the evolutionary longevity of gene circuits because they provide strong control with reduced burden [24].

- Upstream Open Reading Frames (uORFs): uORFs are short coding sequences located in the 5' untranslated region (5' UTR) of an mRNA. The translation of a uORF can regulate the translation of the downstream main ORF by modulating ribosome progression and re-initiation. uORFs are a natural mechanism for fine-tuning gene expression in response to cellular conditions, and their manipulation (e.g., using antisense oligonucleotides to block the uORF start codon) is an emerging translational control strategy [22].

- Elongation and Termination: The speed of ribosomal elongation and the efficiency of termination can also impact overall protein yield and co-translational folding. While more complex to engineer, these processes represent additional points of potential control.

Experimental Protocol: Ribosome Profiling (Ribo-Seq) for Translational Efficiency Analysis

Ribosome profiling is a powerful method that provides a genome-wide, nucleotide-resolution snapshot of translation by sequencing ribosome-protected mRNA fragments [22].

- Cell Lysis and Nuclease Digestion: Rapidly lyse cells to freeze translational states. Treat the lysate with RNase I, which degrades mRNA regions not protected by bound ribosomes.

- Ribosome-Protected Fragment (RPF) Purification: Isolate the ribosome-protected mRNA fragments (typically ~30 nucleotides) by size selection through sucrose cushion centrifugation or gel extraction.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Convert the purified RPFs into a sequencing library. In parallel, prepare a standard RNA-seq library from the same sample's total mRNA.

- Data Analysis and Translational Efficiency (TE) Calculation:

- Map the RPF sequencing reads and the RNA-seq reads to a reference genome.

- Quantify the ribosome density for each gene from the RPF data.

- Quantify the mRNA abundance for each gene from the RNA-seq data.

- Calculate the Translational Efficiency (TE) for each gene using the formula:

TE = (Normalized RPF read count) / (Normalized RNA-seq read count) - Changes in TE (ΔTE) under different conditions (e.g., with/without ligand, or in a disease state) reveal genes that are subject to specific translational regulation.

Table 2: Core Methodologies for Studying Translational Regulation

| Method | Principle | Key Output | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUnSET Assay | Incorporation of puromycin, a tRNA analog, into nascent peptides during active translation, detected via immunoblotting. | Global rate of protein synthesis. | Simple, measures translation in whole cells/tissues. |

| Ribosome Profiling (Ribo-Seq) | Deep sequencing of ribosome-protected mRNA fragments (RPFs). | Genome-wide map of ribosome positions and density. | Nucleotide resolution; identifies actively translated ORFs (including uORFs); calculates TE. |

| Polysome Profiling | Sucrose gradient centrifugation to separate mRNAs based on the number of bound ribosomes. | Transcriptome-wide assessment of translation activity. | Distinguishes highly translated from poorly translated mRNAs. |

| TRAP / Ribo-tag | Immunoprecipitation of epitope-tagged ribosomes from specific cell types in a complex tissue. | Translatome of a specific cell population. | Cell-type-specific translational information in vivo. |

Integration and Application in Dynamic Regulation

The true power of transcriptional and translational control is realized when they are intelligently integrated to create robust, dynamic regulatory systems for TF-based biosensors.

Dynamic Control in Metabolic Engineering

TF-based biosensors enable two primary application paradigms in metabolic engineering:

- High-Throughput Screening: Biosensors can be designed to link the production of a desired metabolite to a easily measurable output (e.g., fluorescence). This allows for the rapid screening of vast mutant libraries to identify high-producing strains, dramatically accelerating the strain optimization process [14] [10].

- Closed-Loop Dynamic Regulation: In this advanced strategy, a biosensor continuously monitors the concentration of a key pathway intermediate. The output of the biosensor is then linked to a genetic controller that dynamically regulates the expression of pathway enzymes. This allows the cell to autonomously balance metabolic flux, avoid the accumulation of toxic intermediates, and maximize product yield without researcher intervention [14] [10]. For example, a TF that senses a fatty acid intermediate could dynamically control the expression of upstream enzymes in the biofuel synthesis pathway.

Enhancing Evolutionary Longevity with Genetic Controllers

A major challenge in synthetic biology is the evolutionary degradation of engineered gene circuits due to mutations that reduce metabolic burden [24]. "Host-aware" computational frameworks have been used to design genetic controllers that extend circuit functional half-life.

- Negative Autoregulation: This transcriptional feedback topology, where a TF represses its own promoter, can reduce expression noise and burden, prolonging short-term performance [24].

- Growth-Based Feedback: Controllers that couple circuit output to host growth rate can significantly extend the functional half-life (Ï„â‚…â‚€) of a circuit. Simulations show that growth-based feedback can outperform intra-circuit feedback in the long term [24].

- Multi-Input Controllers: The most effective designs combine multiple control inputs (e.g., circuit output and growth rate) and actuation methods (transcriptional and post-transcriptional). These complex controllers can improve circuit half-life over threefold without needing to couple to an essential gene [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Transcriptional and Translational Control Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Allosteric Transcription Factor (aTF) Scaffolds | The core sensing component of a biosensor. Can be engineered for new ligands. | TtgR, a promiscuous multidrug efflux regulator, was used as a scaffold to design biosensors for naltrexone and quinine [16]. |

| Reporter Genes | Generate a measurable output (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) linked to biosensor activity. | GFP for fluorescence-based screening and quantification via flow cytometry or plate readers [23] [10]. |

| Synthetic Promoters | Engineered DNA sequences that control transcription initiation in response to a specific TF. | The synthetic promoter QT was designed to be controlled by the artificial TF ProB [23]. |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Libraries | A diverse collection of RBS sequences with varying strengths to tune translation initiation. | Fine-tuning the expression level of a pathway enzyme to balance metabolic flux and reduce burden. |

| Small RNAs (sRNAs) | Used for post-transcriptional regulation by targeting specific mRNAs for silencing. | Implementing a post-transcriptional controller to enhance the evolutionary longevity of a gene circuit [24]. |

| Puromycin | An aminoacyl-tRNA analog that incorporates into nascent chains and halts translation. | Used in the SUnSET assay to label and quantify global protein synthesis rates [22]. |

| Ribo-tag / TRAP System | Enables cell-type-specific isolation of translating mRNAs from complex systems or in vivo models. | Studying the translatome of cardiomyocytes within heart tissue to understand cardiac disease [22]. |

| Cbz-Gly-Pro-Ala-O-cinnamyl | Cbz-Gly-Pro-Ala-O-cinnamyl, MF:C27H31N3O6, MW:493.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SORT-PGRN interaction inhibitor 3 | SORT-PGRN interaction inhibitor 3, MF:C15H19Cl2NO3, MW:332.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Transcription factor-based biosensors (TFBs) are genetically encoded devices that utilize allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) to sense intracellular metabolite concentrations and convert this biological signal into a measurable output, typically fluorescence [8] [10]. This fundamental operating principle has positioned them as powerful tools for high-throughput screening (HTS) in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. They enable researchers to rapidly sift through vast libraries of engineered microbial strains to identify rare high-performers, overcoming a critical bottleneck in the development of efficient microbial cell factories [25] [26]. By linking the production of a desired compound, such as a natural product or bio-chemical, to a simple fluorescence readout, TFBs transform the complex task of quantifying metabolite titers into a straightforward process of measuring fluorescence intensity, either in liquid culture or directly from colonies on agar plates [27] [14]. This review details the core mechanisms, applications, and methodologies for implementing TFB-driven HTS in strain and enzyme engineering programs.

Core Principles of TF-Based Biosensors for HTS

Mechanism of Action

The operation of a TFB follows a coherent logic that can be broken down into three key steps, as illustrated in the diagram below.

- Analyte Recognition: An intracellular transcription factor (TF) specifically binds to a target metabolite (the inducer or ligand), causing a conformational change in the TF [8].

- Signal Transduction: This ligand-induced change alters the TF's affinity for its specific DNA operator sequence located within a synthetic promoter. Depending on the biosensor design (activator- or repressor-based), this binding either initiates or relieves repression of transcription [8] [10].

- Output Generation: The change in promoter activity regulates the expression of a downstream reporter gene, such as Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) or Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP). The fluorescence intensity of the cell population becomes a quantifiable proxy for the intracellular concentration of the target metabolite [8] [27].

Key Performance Metrics for HTS

For a TFB to be effective in HTS, it must be optimized for specific performance characteristics. A suboptimal biosensor can lead to high rates of false positives or negatives, failing to identify the best producers.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for HTS-Optimized Biosensors

| Metric | Definition | Impact on HTS | Ideal Value/Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | The fold-change in output signal between the fully induced and uninduced (basal) states [8]. | A large dynamic range improves the resolution between high- and low-producing strains, making them easier to separate. | >10-fold to 100-fold is often desirable. |