Taming the Variability: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimizing Cell-Free System Batch-to-Batch Consistency

Batch-to-batch variability remains a significant hurdle in the widespread adoption of cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems for research and biomanufacturing.

Taming the Variability: A Comprehensive Guide to Optimizing Cell-Free System Batch-to-Batch Consistency

Abstract

Batch-to-batch variability remains a significant hurdle in the widespread adoption of cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems for research and biomanufacturing. This article provides a holistic guide for scientists and drug development professionals, addressing the fundamental causes of variability, established and emerging AI-driven methodological solutions, practical troubleshooting protocols, and comparative analyses of system performance. By synthesizing the latest advancements, from optimized extract preparation to fully automated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles, this resource aims to equip researchers with the strategies needed to achieve robust, reproducible, and high-yielding cell-free reactions, thereby accelerating the development of therapeutics, biosensors, and other synthetic biology applications.

Understanding the Sources of Cell-Free System Variability

Troubleshooting Guide: Batch-to-Batch Variability

Common Problems and Solutions

Problem: Inconsistent protein yield between different batches of cell-free reagents

- Possible Cause: Natural variation in the composition of cell extracts between production lots. Lysate-based systems contain complex mixtures of ribosomes, tRNAs, cofactors, and enzymes, where slight differences in production can affect performance [1].

- Solution: Implement rigorous quality control. For each new reagent batch, run a standardized control reaction with a well-characterized template DNA and quantify the protein output. Use this data to establish acceptable performance ranges and normalize experimental conditions accordingly.

Problem: Variable results in nanoparticle toxicity studies

- Possible Cause: Significant physicochemical variability between nanomaterial batches, affecting biological outcomes [2]. A multi-laboratory study characterized 46 different batches of OECD priority nanomaterials (SiOâ‚‚, ZnO, CeOâ‚‚, TiOâ‚‚) and found batch-to-batch differences in properties like size, surface chemistry, and agglomeration state [2].

- Solution: Fully characterize nanomaterial batches using a standardized protocol. The OECD WPMN recommends assessing parameters including composition, impurities, size distribution, shape, and surface characteristics to identify the source of variability [2].

Problem: Fluctuating feeding performance in continuous manufacturing

- Possible Cause: Variability in excipient properties like particle size and flowability. One study evaluated over 200 batches of spray-dried lactose and found that in a "stretched" feeder set-up, this variability introduced significant variation in the feed factor [3].

- Solution: Optimize processing equipment and parameters. For the optimized feeder set-up, the impact of batch-to-batch variation was negligible compared to natural feeding variability [3].

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing Reagent Batch Variability

Objective: To quantify the performance differences between multiple batches of a cell-free protein synthesis system.

Materials:

- Batches of cell-free expression kit (e.g., NEBExpress E. coli System) [4] [5]

- Standardized control plasmid DNA (e.g., encoding a 30 kDa fluorescent protein)

- Nuclease-free water

- Equipment: Thermomixer or incubator with shaking, SDS-PAGE setup, spectrophotometer or imager for quantification

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: For each batch of cell-free reagents, set up a minimum of three replicate 50 µL protein synthesis reactions according to the manufacturer's instructions. Use the same master mix of purified control DNA for all reactions [4].

- Incubation: Incubate reactions at a constant temperature (e.g., 37°C) for a defined period (e.g., 2-4 hours) with shaking [6] [5].

- Analysis: Analyze the synthesized protein yield by SDS-PAGE. Visualize proteins with Coomassie stain and quantify band intensity using densitometry [4] [5].

- Data Calculation: For each batch, calculate the average yield and the coefficient of variation (CV). Compare the average yields and CVs between batches using statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA).

Expected Outcome: This protocol will reveal the magnitude of yield variability attributable to the reagent batches themselves, providing a quantitative basis for assessing the significance of experimental results.

Quantitative Data on Batch-to-Batch Variability

The following table summarizes key findings from published studies that have quantified batch-to-batch variability.

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Batch-to-Batch Variability in Research Systems

| System/Product | Key Finding on Variability | Quantifiable Impact | Primary Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials (SiOâ‚‚, ZnO, etc.) | Significant variability in physicochemical properties (size, surface chemistry) across 46 batches [2]. | Leads to different protein adsorption patterns and unpredictable biological outcomes, creating uncertainty in safety assessments [2]. | [2] |

| Spray-Dried Lactose (Excipient) | Variability in material properties (e.g., particle size, flowability) across >200 batches [3]. | Negligible impact in an optimized feeder setup (22 mm screws, 342 rpm). Introduced significant variation in a stretched setup (11 mm screws, 514 rpm) [3]. | [3] |

| Commercial Animal Diets | Significant batch-to-batch variability in estrogenic content (e.g., phytoestrogens) [7]. | Alters experimental outcomes in endocrine and cancer research, potentially leading to conflicting findings between labs [7]. | [7] |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis | AI can optimize buffer composition to improve productivity and reduce effects of variability [1]. | An active learning approach achieved a 34-fold increase in protein production by identifying critical parameters [1]. | [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Cell-Free Protein Synthesis and Batch Control

| Reagent / Material | Function | Considerations for Batch Variability |

|---|---|---|

| S30 Synthesis Extract | Contains the cellular machinery (ribosomes, tRNAs, enzymes) for transcription and translation [4] [5]. | The most complex component; sensitive to production and storage conditions. Minimize freeze-thaw cycles; aliquot and store at -80°C [4]. |

| T7 RNA Polymerase | Drives transcription from the T7 promoter in the DNA template [4] [5]. | A defined, purified component. Its absence will halt synthesis. Ensure it is added to every reaction [4]. |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects mRNA in the reaction from degradation [4]. | Critical when template DNA is prepared using commercial kits that may contain RNase A. Use the supplied inhibitor to improve reproducibility [4]. |

| Purified Template DNA | The genetic blueprint for the target protein. | Concentration and purity are critical. Contaminants (e.g., salts, SDS, ethidium bromide) can inhibit reactions. Use high-quality purification kits [4] [6]. |

| Amino Acid Mixture | Building blocks for protein synthesis. | Concentration can be optimized. Amino acid-free systems (e.g., WEPRO8240) allow for custom mixtures and labeling [8]. |

| PURExpress Disulfide Bond Enhancer | Promotes the formation of correct disulfide bonds in synthesized proteins [4]. | A defined supplement to improve the activity and solubility of specific protein targets, reducing functional variability [4]. |

| VU6008677 | VU6008677, MF:C14H13ClN4O, MW:288.73 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lp(a)-IN-5 | Lp(a)-IN-5, MF:C43H56N4O7, MW:740.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary sources of batch-to-batch variability in cell-free lysates? The primary sources stem from the inherent complexity of the cell extract, which is a crude mixture of thousands of cellular components. Minor differences in the growth conditions of the source cells, the lysis efficiency, and the subsequent processing and storage of the extract can all lead to variations in the final concentration of critical components like ribosomes, tRNAs, and energy-regenerating enzymes [1].

Q2: How can I control for batch variability when planning a long-term research project? When possible, purchase a sufficient quantity of a single batch of critical reagents (like cell-free systems) to complete the entire project. For materials that cannot be stockpiled, such as certain nanoparticles, implement a strict quality control protocol. Characterize each new batch against the previous one using a standardized bioassay or physicochemical analysis to understand the scope of any variation before using it in critical experiments [2].

Q3: Can AI and machine learning really help reduce the impact of batch variability? Yes, active learning approaches are being used to optimize complex systems like cell-free protein synthesis. By exploring a vast combinatorial space of buffer compositions, AI can identify critical parameters that maximize productivity and consistency, effectively reducing the negative impact of underlying component variability [1]. This leads to more robust and reproducible processes.

Q4: Is batch-to-batch variability only a problem with complex biological reagents? No, variability is a significant challenge across many material types. Studies have shown that even engineered materials like nanoparticles and common pharmaceutical excipients like lactose exhibit meaningful batch-to-batch differences that can impact downstream applications and research reproducibility [3] [2].

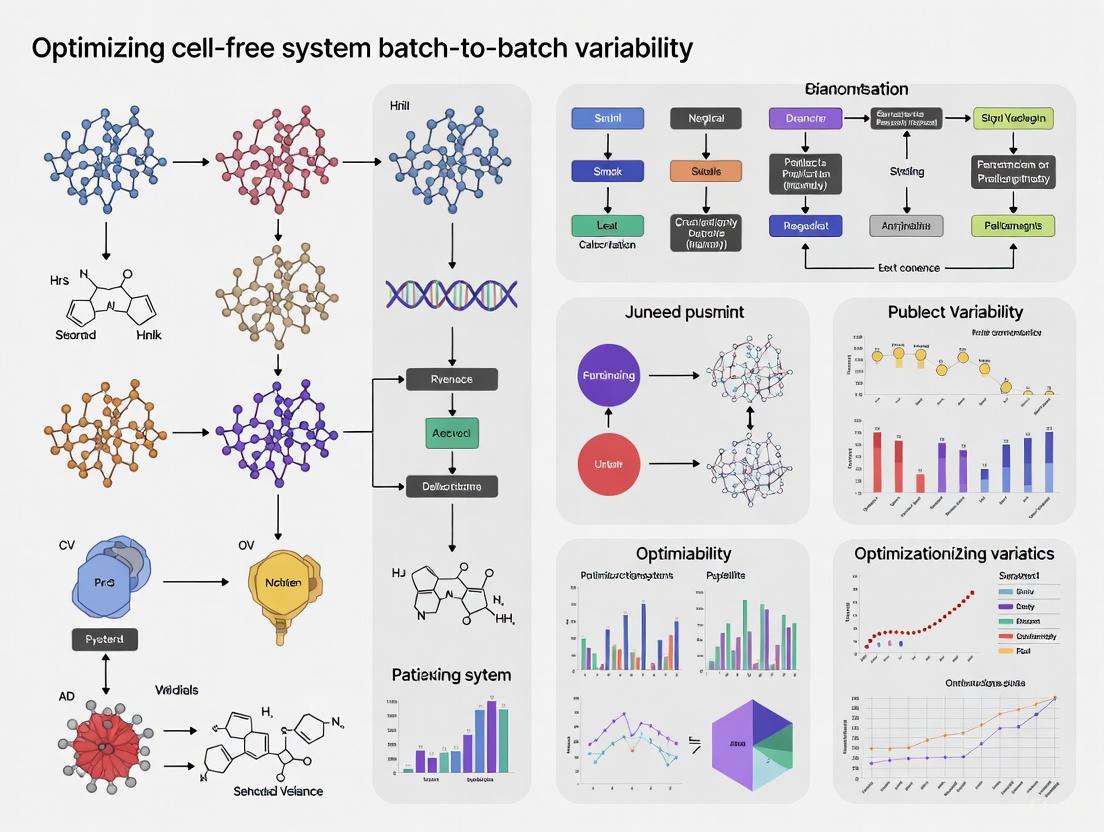

Workflow Diagram for Batch Variability Management

Workflow for Managing New Reagent Batches

AI-Optimization Diagram for Cell-Free Systems

AI-Driven Optimization of Cell-Free Systems

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) has emerged as a transformative technology in synthetic biology, enabling rapid in vitro protein expression without the constraints of cell viability. This platform is invaluable for applications ranging from protein engineering and metabolic pathway prototyping to biosensor development and on-demand biomanufacturing [9]. However, a significant challenge hindering its reproducibility and broader adoption is batch-to-batch variation, which can originate at multiple stages of the workflow. This technical support article, framed within a broader thesis on optimizing batch-to-batch variability, identifies the major hotspots of this variation—from cell extract preparation to reaction assembly—and provides targeted troubleshooting guides to enhance experimental consistency and reliability for researchers and drug development professionals.

Identifying Major Variability Hotspots

Variability in CFPS systems is not attributable to a single source but is an aggregate effect of inconsistencies across multiple steps. The diagram below maps the primary sources of variability and the recommended strategies to mitigate them.

Quantitative Data on Variability Across Systems

The performance and inherent variability of a CFPS system are influenced by the choice of source organism. The table below summarizes key characteristics of common systems, highlighting their respective advantages and optimization status.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems and Their Typical Yields

| Organism | Protein Expression Yield (µg/mL) | Key Advantages | Inherent Variability Challenges | Reported Optimization Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 2,300 (batch) [10] | Low cost, high yield, easy to prepare, well-documented [10] | Prokaryotic limitations (limited PTMs, folding issues) [10] | High [10] |

| Wheat Germ | 20,000 [10] | Superior folding for complex proteins, suitable for disulfide bonds [8] [10] | Laborious and expensive lysate preparation; limited PTMs [8] [10] | High [10] |

| CHO Cells | 980 (continuous) [10] | Contains ER-derived microsomes, high acceptance for therapeutics [10] | High cultivation cost, relatively low yield in batch mode [10] | Medium [10] |

| S. frugiperda | 285 [10] | High microsome level aiding membrane protein production and PTMs [10] | Relatively low protein yield, high cultivation cost [10] | Medium-High [10] |

| S. cerevisiae | 8 (batch) [10] | High chassis knowledge for bioproduction [10] | Low protein yield, no mammalian-like PTMs [10] | Low [10] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

A. Cell Extract Preparation

Q: Our lab-made cell extracts show significant batch-to-batch variation in protein synthesis yield. What are the critical factors to control?

- A: The primary sources of variation during extract preparation are the lysis method and the quality of the source cells.

- Lysis Method Consistency: The method of cell disruption (e.g., sonication, French press, enzymatic) must be standardized. Different methods can vary in efficiency and generate varying levels of heat, potentially damaging the transcription-translation machinery. Adhere to one validated protocol for all preparations [10].

- Source Cell Health and Passage Number: The health and passage number of cells used for lysate preparation are critical. For mammalian cells like HEK293, keep the passage number between 5 and 20. Older cells may exhibit slower growth, poorer transfection efficiency, and altered post-translational modifications, all contributing to variability [11]. Use clonal cell lines where possible to limit biological fluctuations.

- Lysate Processing and Storage: After lysis, ensure consistent steps for clarification (e.g., centrifugation) and nuclease treatment. Aliquot the final lysate to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, which can degrade sensitive components [10].

Q: How does the choice of source organism impact the variability and functionality of the cell-free system?

- A: The source organism defines the system's capabilities and its inherent noise.

- E. coli systems are highly optimized and generally offer the lowest variability for standard protein production [10].

- Eukaryotic systems (e.g., wheat germ, insect cells) are essential for complex proteins but introduce more variables. For instance, wheat germ extracts contain a methionine aminopeptidase, and its activity can vary, leading to inconsistent N-terminal methionine processing [8]. Furthermore, while some post-translational modifications (PTMs) like phosphorylation can occur, they may not match native patterns, and glycosylation is absent due to the removal of the endoplasmic reticulum during extract preparation [8].

- Non-model organisms may offer unique functionalities (e.g., specific transcription factors for biosensors) but are far less optimized, leading to higher batch-to-batch variation [10].

B. Reaction Assembly and Components

Q: We observe inconsistent results even when using the same lysate batch. Which reaction components are most likely to be at fault?

- A: Inconsistencies in reaction assembly are a major variability hotspot. Key components to monitor include:

- Energy Regeneration System: The system that maintains ATP/GTP levels (e.g., based on phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) or creatine phosphate) is crucial for reaction longevity. The quality and stability of these components are vital; degraded energy sources will lead to low yield and high variability [9].

- Divalent Cations (Mg²âº): The concentration of Mg²⺠is critical for translation efficiency. Even small deviations can significantly impact protein yield. Optimize and consistently use a specific concentration for your system [8] [9].

- DNA Template Quality and Quantity: The DNA template must be pure and intact. Using a validated expression vector (e.g., the pEU series for the wheat germ system) is recommended. Linear PCR products can be used but often give lower and more variable yields compared to plasmid DNA [8]. Prepare large, high-quality DNA stocks and use a precise quantification method to ensure the same template amount is used in every reaction.

Q: Can we add detergents or lipids to the reaction to improve the solubility of membrane proteins, and how might this affect variability?

- A: Yes, detergents can be added to increase solubility, and lipids can be added in the form of liposomes (e.g., asolectin liposomes) to create proteoliposomes for membrane proteins [8].

- Impact on Variability: The use of these additives must be rigorously standardized. Detergents can inhibit translation if used above a critical concentration, which must be determined empirically for each detergent and lysate batch [8]. Similarly, the size and composition of liposomes (e.g., a monodisperse preparation with a peak of 150 nm) can affect incorporation efficiency [8]. Any deviation in the concentration or quality of these additives will introduce variability.

C. Analytics and Measurement

Q: How can we improve the accuracy and consistency of measuring key outputs like protein yield and viral titer?

- A: Historical methods like plaque assays for viral titer are prone to human error [11].

- Adopt Orthogonal Analytics: Use multiple methods to cross-validate results. For viral vectors, combine methods like UV absorbance, anion-exchange chromatography, and electron microscopy to determine the ratio of full/empty capsids more robustly than with a single method [11].

- Automate Where Possible: Utilize automated systems for image acquisition and analysis of assays like plaque counts or use flow cytometry-based methods to reduce subjectivity [11].

- Standardize with Controls: Include a well-characterized control protein or viral preparation in every experiment to normalize results and track the performance of the CFPS system or analytics over time.

Experimental Protocols for Variability Assessment

Protocol 1: Assessing Lysate Batch Consistency

Objective: To quantitatively compare the performance of different lysate batches and identify outliers. Materials:

- Lysate batches to be tested.

- Standardized control DNA template (e.g., encoding GFP).

- Master mix of reaction components (energy source, amino acids, salts).

Method:

- Prepare Reaction Master Mix: Create a large, homogeneous master mix containing all reaction components except the DNA template and lysate. This eliminates variability from pipetting these components.

- Assemble Reactions: For each lysate batch, assemble multiple reactions using the same volume of master mix, the same amount of control DNA, and the same volume of the respective lysate.

- Incubate and Measure: Incubate reactions under standard conditions (e.g., 2-6 hours at 30°C). Measure the output (e.g., GFP fluorescence, soluble protein yield via Bradford assay) at defined time points.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean yield and coefficient of variation (CV) for replicates of each batch. A lysate batch with a significantly lower mean yield or a higher CV than others should be investigated or excluded.

Protocol 2: Optimizing and Validating Critical Reaction Components

Objective: To determine the optimal concentration of a variable component (e.g., Mg²âº) and establish a robust operating window. Materials:

- A single batch of high-performance lysate and control DNA.

- Stock solutions of the component to be optimized (e.g., 1M Mg(OAc)â‚‚).

Method:

- Design a Dilution Series: Prepare the reaction master mix without the target component. Set up a series of reactions where the concentration of the target component is varied (e.g., Mg²⺠from 1 mM to 10 mM in 1 mM increments).

- Run Reactions and Quantify: Incubate all reactions in parallel and quantify the functional output (e.g., yield of an active enzyme).

- Model the Response: Plot the yield against the component concentration. Identify the concentration that provides the peak yield and the range where yield is ≥90% of the maximum. This range defines your robust operating window, and the center of this window should be your standard concentration to minimize the impact of small pipetting errors [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Managing Cell-Free System Variability

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale | Variability Mitigation Role |

|---|---|---|

| Clonal Producer Cell Line | Genetically identical cells used for lysate preparation [11]. | Reduces biological variation at the source, a foundational step for consistency. |

| Validated Expression Vector (e.g., pEU) | DNA template with optimized promoter (e.g., SP6) and regulatory elements (e.g., E01 enhancer) [8]. | Ensures high and consistent transcription/translation initiation, reducing template-induced variability. |

| Master Mix of Reaction Buffers | A pre-mixed, aliquoted solution of salts, nucleotides, and energy regeneration components [9]. | Eliminates pipetting error of individual components during reaction assembly, a major technical hotspot. |

| Stable Isotope/Labeled Amino Acids | For quantitative tracking of protein synthesis and mass spectrometry analysis [8]. | Enables precise, direct measurement of yield, bypassing indirect assays that may have their own variability. |

| Affinity Tag Resins (e.g., Ni-NTA, Glutathione) | For purification of tagged proteins (His-tag, GST-tag) [8]. | Allows for specific isolation of the target protein from background lysate proteins, improving accuracy of functional assays. |

| Liposome Preparations (e.g., Asolectin) | Lipid vesicles for incorporating membrane proteins during synthesis [8]. | Provides a consistent lipid environment for membrane protein folding, reducing aggregation-related variability. |

| Bacithrocin C | Bacithrocin C, MF:C18H27N5O3, MW:361.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ARN14988 | ARN14988, MF:C16H24ClN3O5, MW:373.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of Cellular Health and Lysis Methods in Extract Consistency

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary sources of batch-to-batch variability in cell-free extracts? Batch-to-batch variability primarily stems from inconsistencies in the source cells' health and the methods used to lyse them. Key factors include:

- Cellular Health: The growth conditions, passage number, and contamination status (e.g., mycoplasma) of the source cells can significantly alter the biochemical composition of the final extract [13] [14].

- Lysis Method: Different physical lysis methods (e.g., sonication, French press) apply varying shear forces and can generate localized heat, leading to the differential inactivation of sensitive enzymes crucial for protein synthesis [15] [10].

- Parameter Sensitivity: Research on Leishmania tarentolae systems has shown that extract activity is highly sensitive to specific reaction conditions, such as the concentration of magnesium and the ratio of feed solution to lysate. Minor pipetting errors in these parameters can lead to major differences in protein yield [16].

2. How does the choice of lysis method impact the quality of a cell-free extract? The lysis method directly influences the integrity and activity of the translational machinery released from the cells.

- Physical Methods: Methods like sonication and homogenization are efficient but can generate heat and shear forces that denature proteins and cause inconsistent disruption, where some cells break earlier and expose their contents to disruptive forces for longer [15] [17].

- Enzymatic/Chemical Methods: Using lysozyme or detergents offers a gentler and more reproducible approach. However, these components may need to be removed before downstream applications and can be ineffective for some tough tissues [15]. The choice of chassis organism (e.g., E. coli, wheat germ, insect cells) for the extract also determines the native biochemical environment, affecting the ability to produce functional, properly modified proteins [10].

3. What are the best practices to ensure consistency in cell-free extract preparation? To minimize variability, adhere to the following protocols:

- Standardize Cell Culture: Use low-passage cells, maintain consistent growth conditions, and regularly authenticate cell lines and test for contaminants like mycoplasma [13] [14].

- Optimize and Control Lysis: Pre-chill all equipment and keep samples on ice to prevent heat denaturation. For a given cell type, empirically determine the optimal lysis protocol (e.g., number of sonication pulses, homogenization strokes) and apply it consistently [15] [18].

- Precisely Manage Reaction Components: Fully solubilize all master mix components and carefully control pipetting to ensure accurate concentrations, particularly for critical ions like Mg²⺠[16] [18]. Adding protease inhibitors and nucleases (DNase/RNase) during lysis can protect the extract from degradation and reduce viscosity [15].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common problems encountered when preparing cell-free extracts.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low protein synthesis yield | Cell lysis method is too harsh or gentle; suboptimal Mg²⺠concentration; degraded cellular machinery. | Optimize lysis efficiency [15]; Titrate Mg²⺠concentration for each new lysate batch [16]; Use fresh, healthy source cells and include protease inhibitors [15] [13]. |

| High variability between replicate reactions | Inconsistent pipetting; incomplete solubilization of reaction components; uneven cell lysis. | Use master mixes for all common components [18]; Vortex and centrifuge master mix stocks to ensure they are fully solubilized [18]; Standardize the lysis protocol (time, power, pressure) [15]. |

| Loss of protein activity/function | Protease degradation during lysis; denaturation from localized heating; incompatible detergent in lysis buffer. | Always perform lysis on ice and include a protease inhibitor cocktail [15] [17]; For sonication, use short pulses with cooling intervals [15]; For functional studies, use mild, non-ionic detergents [15] [17]. |

| High viscosity of the lysate | Release of genomic DNA from cells during lysis. | Add DNase I (25–50 µg/mL) to the lysis buffer [15]; Note: Sonication shears DNA, reducing the need for nuclease treatment [15]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized Physical Lysis for Bacterial Extracts using Sonication This protocol is designed to maximize yield while maintaining the activity of the translational machinery.

- Cell Harvest: Grow source cells (e.g., E. coli) to mid-log phase. Pellet cells by centrifugation (e.g., 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C).

- Wash and Resuspend: Wash cell pellet with cold S30 buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-acetate, 14 mM magnesium acetate, 60 mM potassium glutamate). Resuspend cells in a minimal volume of the same buffer to create a dense suspension.

- Lysis by Sonication:

- Transfer the cell suspension to a pre-chilled tube and keep on ice.

- Sonicate using a probe sonicator with the following parameters: Amplitude: 40%; Pulse: 15 seconds ON, 45 seconds OFF; Total ON time: 2-3 minutes.

- This intermittent pulsing prevents sample overheating [15].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C) to remove cell debris.

- Incubation and Dialysis: Transfer the supernatant (S12 extract) to a dialysis cassette and dialyze against S30 buffer for 3-4 hours at 4°C. This step removes small molecules and allows the extract to recover.

- Aliquoting and Storage: Aliquot the clarified extract, flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Reaction Conditions to Reduce Variability This procedural adjustment can dramatically improve consistency.

- Master Mix Preparation: Create a master mix of all common reaction components (e.g., energy sources, amino acids, salts, DNA template) for all replicates in an experiment. Vortex thoroughly and briefly spin down to ensure a homogenous solution [18].

- Magnesium Titration: For a new batch of lysate, set up a series of small-scale (e.g., 10 µL) test reactions where the Mg²⺠concentration is varied in 1-2 mM increments around a typical starting point (e.g., 8-16 mM) [16].

- Reaction Assembly: Combine the master mix, lysate, and water/Mg²⺠solution carefully by pipetting. Avoid introducing bubbles.

- Analysis: Incubate reactions at the desired temperature and measure protein yield (e.g., via fluorescence, radioactivity). The Mg²⺠concentration that gives the highest yield should be used for all subsequent experiments with that lysate batch [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Cell-Free System Optimization |

|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents degradation of enzymes and expressed proteins in the lysate by endogenous proteases [15] [17]. |

| DNase I | Reduces lysate viscosity by digesting genomic DNA released during lysis, facilitating pipetting and mixing [15]. |

| Lysozyme | Digests the peptidoglycan cell wall of bacteria, enabling gentler and more efficient lysis, often used in combination with other methods [15]. |

| Magnesium Acetate (Mg²âº) | A critical cofactor for translation. Its optimal concentration is lysate-batch-specific and must be determined empirically for consistent high-yield protein synthesis [16]. |

| Non-ionic Detergents | Gentle detergents (e.g., Triton X-100) used to solubilize membrane proteins without denaturing the sensitive translational machinery [15] [17]. |

Visualizing the Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing sources of batch-to-batch variability.

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) has emerged as a powerful platform technology for protein expression, metabolic engineering, and therapeutic development. Unlike in vivo systems, CFPS offers an open environment that eliminates reliance on living cells and channels all system energy toward producing the target protein [19]. However, as the field advances toward applications in biomanufacturing, diagnostic sensors, and drug development, reproducibility challenges have become a significant bottleneck. Researchers increasingly report difficulties reproducing results between laboratories, and sometimes even between individuals within the same laboratory [20].

This technical support center addresses the critical need to quantify, understand, and troubleshoot both intralaboratory (within-lab) and interlaboratory (between-lab) variations in cell-free systems. For researchers and drug development professionals working to optimize batch-to-batch consistency, recognizing that "materials prepared at each laboratory, exchanged pairwise, and tested at each site resulted in a 40.3% coefficient of variation compared to 7.64% for a single operator across days using a single set of materials" provides both a challenge and a benchmarking opportunity [20]. The following sections provide comprehensive troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks to systematically address these variability sources and enhance the reliability of your cell-free protein synthesis research.

Quantitative Landscape of CFPS Variability

Understanding the magnitude and sources of variability requires robust quantitative assessment. The following data, compiled from controlled interlaboratory studies, provides critical benchmarking metrics for evaluating your own system performance.

Table 1: Quantitative Assessment of Interlaboratory CFPS Variability

| Variability Source | Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Experimental Context | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Interlaboratory | 40.3% | Materials prepared and tested at different sites [20] | Primary contributor to total variability |

| Single Operator (Intralaboratory) | 7.64% | Single operator across days using identical materials [20] | Benchmark for best-case performance |

| Reagent Preparation | Significant contributor | Reagents prepared in different laboratories [20] | Major factor in observed variability |

| Cell Extract Preparation | Not significant | Extracts prepared in different laboratories by different operators [20] | Surprisingly minimal contribution |

| Site & Operator Effects | Significant contributors | Controlled exchange experiments [20] | Both factors independently important |

The profound impact of variability extends beyond CFPS to other sophisticated biological assays. In HIV-1 latent reservoir quantification using quantitative viral outgrowth assays (QVOA), typical results are expected to differ from the true value by a factor of 1.6 to 1.9 up or down, while systematic differences between laboratories showed a 24-fold range between the highest and lowest scales [21]. Similarly, in clinical HbA1c measurement, interlaboratory variation decreased significantly to 2.1%-2.6% by 2023, with 58.9% and 79.8% of laboratories achieving intra-laboratory coefficients of variation <1.5% for low and high QC levels, respectively [22]. These comparative metrics highlight both the challenge and potential for improvement through systematic quality control.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between intralaboratory and interlaboratory variability?

A: Intralaboratory variation (within-lab) compares results within the same facility, checking repeatability between different analysts, instruments, or batches. Interlaboratory variation (between-lab) compares results across different facilities, assessing standardization and detecting systematic biases across sites [23]. In CFPS, intralaboratory variation for a single operator using identical materials can be as low as 7.64% CV, while interlaboratory variation often exceeds 40% CV [20].

Q2: Why does my protein yield decrease significantly when the protocol is transferred to another laboratory?

A: This common issue typically stems from multiple factors: reagent preparation differences (significant contributor), subtle variations in technique by different operators, and site-specific environmental conditions [20]. Even with identical protocols, studies show that both the site and operator independently contribute to observed variability. Implementing material exchanges and personnel training exchanges between sites has been shown to help quantify and reduce these differences [20].

Q3: What are the most common sources of intralaboratory fluctuation in CFPS experiments?

A: Primary sources include: (1) RNase contamination introduced during template DNA preparation, (2) DNA template quality and concentration issues, (3) variations in reagent storage conditions and freeze-thaw cycles, (4) incubation temperature fluctuations, and (5) differences in feeding schedules during extended reactions [6] [24].

Comprehensive Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common CFPS Variability Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Variability Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low or no protein yield | RNase contamination; Improper DNA template design; Inactive kit components | Use nuclease-free materials; Verify sequence and regulatory elements; Minimize freeze-thaw cycles [24] | Interlab: Different lab practices introduce varying contamination levels |

| Inconsistent results between operators | Technique differences in reagent preparation; Variation in incubation conditions | Standardize protocols; Implement hands-on training; Use calibrated equipment [20] | Intralab: Operator technique significantly affects reproducibility |

| Truncated protein products | Proteolysis; Degraded DNA/RNA templates; Premature termination | Add protease inhibitors; Repurify DNA templates; Optimize codon usage [6] | Both: Template quality issues manifest differently across scales |

| High background smearing | Too much protein loaded; Ethanol contamination in reaction; Gel issues | Precipitate proteins with acetone; Reduce sample load; Ensure proper gel handling [6] | Intralab: Technical execution affects result quality |

| Inactive or insoluble protein | Incorrect folding; Lack of required co-factors | Reduce incubation temperature (25-30°C); Add molecular chaperones; Include essential co-factors [6] [24] | Interlab: Different folding conditions across labs |

Advanced Troubleshooting for Persistent Variability:

For challenging variability issues that persist after addressing common problems, consider these advanced strategies:

Reagent Standardization: Implement a centralized reagent preparation and distribution system where critical components are aliquoted from a single master batch to minimize preparation variability [20].

Cross-Laboratory Calibration: Establish a sample exchange program with collaborating laboratories using shared reference materials to identify and quantify systematic biases [21].

Process Controls: Introduce internal control reactions with standardized DNA templates that produce easily quantifiable reporter proteins to normalize results across batches and locations [6].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Standardized Interlaboratory Comparison Protocol

Controlled studies to quantify variability sources follow this rigorous methodology:

Participant Laboratory Selection: Include multiple laboratories (4-5 minimum) with varying expertise levels [21] [25].

Reference Material Preparation: Create a large, homogeneous batch of cell-free system components or DNA templates from a single preparation. Aliquot and distribute to all participants [20].

Controlled Exchanges: Implement a structured exchange plan including:

- Material exchanges (reagents, extracts, templates)

- Personnel exchanges between sites

- Split-sample testing with balanced batch designs [20]

Standardized Analysis: Centralize final analytical measurements where possible, or implement rigorous cross-calibration of instruments between sites [25].

Statistical Analysis: Apply appropriate statistical methods including robust algorithms for outlier detection, Bayesian methods for rare event analysis, and variance component analysis to attribute variability to specific sources [21].

This protocol revealed that reagent preparations contributed significantly to observed variability, while extract preparations surprisingly did not explain significant variation even when prepared in different laboratories by different operators [20].

DNA Template Quality Control Protocol

Ensure consistent template quality through this standardized approach:

Purification: Use commercial mini-prep kits (e.g., Monarch Plasmid Miniprep Kit) but add RNase Inhibitor to counteract potential RNase A contamination. Avoid DNA purified from agarose gels due to inhibitor contamination [24].

Quantification: Measure DNA concentration using UV absorbance (260/280 ratio ~1.8) and verify by agarose gel electrophoresis for correct size, degradation check, and contaminant nucleic acid detection [24].

Optimization: Test different amounts of template DNA (e.g., 25-1000 ng for a 50 μL reaction) to find the optimal balance between transcription and translation. For large proteins (>100 kDa), increase DNA template to 20 μg in a 2 mL reaction [6].

Verification: Confirm sequence integrity, especially ATG initiation codon, reading frame, stop codons, and regulatory elements [6].

Diagram 1: DNA Template Quality Control Workflow. This standardized protocol ensures consistent template preparation across experiments and laboratories.

Interlaboratory Variability Assessment Protocol

Implement this systematic approach to quantify and reduce between-lab differences:

Sample Design: Prepare split samples from homogenized biological material (e.g., PBMCs from single donors or cell cultures from identical passages) [21].

Blinding: Code all samples to conceal participant identity and aliquot information from testing laboratories to prevent cognitive bias [21].

Batch Balancing: Design balanced batches within each laboratory that include samples from multiple sources in controlled combinations to enable separation of batch effects from true biological variation [21].

Control Materials: Include standardized control materials with known expected values in each batch to monitor assay performance over time [22].

Data Analysis: Apply robust statistical algorithms per ISO 13528 guidelines, calculate manufacturer-specific biases when applicable, and use variance component analysis to attribute variability to different sources [22].

This approach in HIV reservoir studies found that controlled-rate freezing and storage of samples did not cause substantial differences compared to fresh cells (95% probability of <2-fold change), supporting continued use of frozen storage to allow transport and batched analysis [21].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Variability Control in CFPS Research

| Reagent/Category | Function & Importance | Variability Control Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| S30 Synthesis Extract | Source of transcription/translation machinery; Critical for system performance | Store at -80°C; Minimize freeze-thaw cycles (<2 cycles); Prepare large master batches [24] |

| T7 RNA Polymerase | Drives transcription from T7 promoters; Essential for protein yield | Use consistent concentration (1-1.5 μL in 50 μL reaction); Verify activity regularly [6] |

| RNase Inhibitor | Prevents mRNA degradation; Critical for yield consistency | Add to reactions especially when using commercial plasmid prep kits; Standardize concentration across labs [24] |

| Amino Acid Mixtures | Building blocks for protein synthesis; Affect yield and fidelity | Use consistent quality sources; Prepare large master mixes; Verify concentration [6] |

| Energy Sources | Fuel translation and transcription; Impact reaction longevity | Standardize ATP, GTP concentrations; Prepare fresh aliquots regularly [19] |

| Molecular Chaperones | Improve protein folding; Reduce aggregation | Add for difficult-to-express proteins; Standardize concentrations across experiments [6] |

| Detergents | Enhance solubility of membrane proteins | Use consistent types and concentrations (e.g., up to 0.05% Triton-X-100) [6] |

| (S)-BI-1001 | (S)-BI-1001, MF:C19H15BrClNO3, MW:420.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SL-176 | SL-176, MF:C24H48O4Si2, MW:456.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Systematic Approach to Variability Reduction

Diagram 2: Systematic Variability Reduction Framework. This structured approach identifies and addresses multiple sources of experimental variation.

Implementing a systematic framework for variability reduction involves continuous monitoring and improvement. Studies demonstrate that sustained focus on quality control significantly enhances performance over time. In HbA1c measurement, interlaboratory variation decreased from 2.6%-3.5% in 2020 to 2.1%-2.6% by 2023 through rigorous quality assurance programs [22]. Similarly, the percentage of laboratories achieving desirable precision levels increased substantially with systematic monitoring and feedback.

Key Performance Monitoring Strategies:

Regular Proficiency Testing: Implement quarterly sample exchanges between collaborating laboratories to maintain awareness of interlaboratory differences [22].

Statistical Process Control: Track quality control metrics using Levey-Jennings charts with Westgard rules to detect systematic shifts or increased random error [22].

Root Cause Analysis: When variability exceeds acceptable limits, conduct structured investigations to identify whether sources are technical, reagent-related, operator-dependent, or instrumental [20].

The journey toward minimized variability requires acknowledging that "bias-free extraction methods are not available, especially not for complex and highly variable matrices" [25], while simultaneously working to render this bias quantifiable and manageable through standardization, controls, and continuous process improvement.

Implications of Variability for Genetic Circuit Prototyping and Data Reproducibility

FAQs: Addressing Common Challenges in Genetic Circuit Prototyping

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of batch-to-batch variability in cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems, and how can I minimize them? Batch-to-batch variability in CFPS is often caused by inconsistencies in cell extract preparation, incomplete solubilization of master mix components, and imprecise reaction assembly [18]. To minimize this, you should:

- Optimize Extract Preparation: Use standardized lysis and centrifugation protocols. Physical methods like sonication or French press can reduce inhibitors in the final extract [10].

- Ensure Complete Solubilization: Vortex and incubate master mix components to ensure they are fully dissolved before setting up reactions [18].

- Practice Careful Mixing: Mix reactions gently but thoroughly to avoid concentration gradients and ensure homogeneity. Implementing these methods has been shown to reduce the coefficient of variation in CFPS experiments from over 97% to 1.2% [18].

FAQ 2: Why does my genetic circuit behave differently when transferred from a cell-free system to a living chassis? This discrepancy often arises from cellular burden—the metabolic load imposed by the synthetic circuit on the host cell's resources, such as ribosomes and nucleotides [26]. This burden reduces the host's growth rate, creating a selective pressure for mutant cells that have inactivated the circuit to outcompete the engineered population [26]. In cell-free systems, which are growth-independent, this evolutionary pressure is absent.

FAQ 3: How can I improve the evolutionary longevity of my genetic circuit in a living chassis? Implementing genetic feedback controllers can help maintain circuit function over time. "Host-aware" computational models suggest that controllers using post-transcriptional regulation (e.g., via small RNAs) generally outperform transcriptional controllers [26]. Furthermore, growth-based feedback, where circuit activity is tied to host fitness, can significantly extend the functional half-life of a circuit [26].

FAQ 4: What practical steps can my lab take to improve the reproducibility of genetic circuit data?

- Automate Processes: Using liquid handling robots or microfluidic devices reduces human error in tedious tasks [27].

- Use Detailed Protocol Platforms: Employ online protocol editors like

protocols.ioto create and share detailed, step-by-step experimental instructions, capturing tacit knowledge that is often missing from standard method sections [27]. - Standardize Measurements: Use methods to standardize data from instruments like plate readers to enable cross-experiment comparisons [28].

- Leverage Biofoundries: Outsourcing circuit construction and testing to automated biofoundries can provide highly standardized and reproducible results [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low or no protein yield in CFPS | Inefficient cell lysis during extract prep [10]. | Optimize lysis method (e.g., sonication parameters, lysozyme concentration) [10]. |

| Incomplete solubilization of reaction components [18]. | Vortex and incubate master mix on ice until fully clear before use [18]. | |

| Depletion of energy/resources in the reaction [10]. | Supplement the reaction with additional energy sources and adjust component concentrations; studies show this can lead to a 34-fold yield increase [10]. | |

| High variability between CFPS replicates | Inconsistent mixing of reactions [18]. | Adopt a careful, standardized mixing procedure (e.g., pipette mixing a set number of times) [18]. |

| DNA template quality and preparation method [28]. | Use a standardized, high-quality DNA template preparation protocol (e.g., kit-based) to minimize variation [28]. | |

| Batch-to-batch differences in cell extract [10]. | Prepare large, single-batch extracts, aliquot, and store at -80°C; characterize each batch with a standard test circuit [10]. | |

| Circuit performance degrades over microbial generations | High metabolic burden selects for loss-of-function mutants [26]. | Re-design the circuit to be more efficient (e.g., using "compressed" designs with fewer parts) [29] or implement negative feedback control to reduce burden [26]. |

| Mutations in circuit DNA [26]. | Use host strains with reduced mutation rates and avoid long repetitive DNA sequences in the circuit design [26]. | |

| Circuit works in one chassis but not another | Lack of specific machinery (e.g., for folding, PTMs) [10]. | Choose a chassis that matches the circuit's requirements (e.g., eukaryotic extracts for complex PTMs) [10]. |

| Non-orthogonal parts interacting with the new host's native regulation [30]. | Select highly orthogonal regulatory parts (e.g., synthetic TFs, CRISPRi) that minimally crosstalk with the host [31] [30]. |

Table 2: Quantifying Variability and Its Impact

| Metric / Factor | Description | Impact on Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | A standardized measure of variability (ratio of standard deviation to mean). | A high CV indicates poor precision. Optimized CFPS protocols can achieve a CV as low as 1.2% [18]. |

| Circuit Half-Life (Ï„50) | The time taken for a population's circuit output to fall to 50% of its initial value due to evolution [26]. | Quantifies the evolutionary longevity of a circuit design. A longer Ï„50 means more reproducible function over time in continuous cultures. |

| Batch-to-Batch Variation | Natural variability in the performance of lab-made cell extracts and reagents [10] [28]. | A major source of frustration that can change the qualitative function of genetic circuits (e.g., an oscillator may stop working) [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Tasks

Protocol 1: Reducing Variability in E. coli-Based CFPS Reactions

This protocol summarizes methods that significantly reduce variability in CFPS experiments [18].

Key Reagents:

- E. coli strain for extract (e.g., BL21)

- Lysis buffer

- CFPS master mix components (amino acids, energy sources, salts, etc.)

- DNA template

Methodology:

- Cell Extract Preparation:

- Grow cells to the optimal density (e.g., mid-log phase).

- Lys cells using a consistent and optimized method (e.g., sonication on ice with defined parameters).

- Centrifuge to remove cell debris and run a runoff reaction to deplete endogenous mRNA.

- Aliquot the extract, flash-freeze, and store at -80°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Reaction Assembly:

- Thaw all components on ice.

- Prepare a master mix for all replicates plus ~10% excess to account for pipetting loss.

- Vortex the master mix thoroughly and ensure all components are fully solubiled. A clear solution is critical.

- Dispense the master mix into reaction tubes.

- Add DNA template using careful pipetting technique.

- Mix the complete reaction carefully by pipetting up and down several times, avoiding bubble formation.

- Incubate at the desired temperature (e.g., 30-37°C) for protein synthesis.

Protocol 2: A Framework for Enhancing Circuit Longevity via Feedback Control

This protocol outlines a model-driven approach for designing more stable genetic circuits [26].

Key Reagents:

- "Host-aware" computational model

- DNA parts for the feedback controller (e.g., promoters, genes for repressors or sRNAs)

Methodology:

- Modeling and Design:

- Use a multi-scale "host-aware" computational model that integrates circuit expression, host resource usage, mutation, and population dynamics [26].

- Simulate different feedback controller architectures (e.g., transcriptional vs. post-transcriptional, sensing different inputs like growth rate).

- Select a controller design that maximizes metrics like τ50 (half-life) and τ±10 (time within 10% of initial output).

Implementation:

- Build the selected controller circuit using standardized, orthogonal parts to minimize crosstalk [30].

- Prefer post-transcriptional controllers using small RNAs (sRNAs) for actuation, as they can provide strong control with lower burden [26].

- Consider designs that separate the controller from the main circuit gene, as this can lead to evolutionary trajectories that favor short-term production boosts [26].

Validation:

- Serially passage the engineered strain in batch culture, measuring both circuit output (e.g., fluorescence) and population dynamics over many generations.

- Compare the experimental τ50 and τ±10 with the model's predictions to validate and refine the design.

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

Diagram 1: Genetic Circuit Evolutionary Stability

Diagram 2: Variability Mitigation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Genetic Circuit Prototyping and Optimization

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors (TFs) | DNA-binding proteins (e.g., TetR, LacI homologs) that control synthetic promoters without crosstalk with the host genome, enabling predictable circuit connections [31] [30]. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 System | A programmable tool for transcriptional repression (CRISPRi) or activation. Its RNA-based programmability allows for a large library of orthogonal regulators for complex circuits [31] [32]. |

| Site-Specific Recombinases | Enzymes (e.g., Cre, Flp, serine integrases) that invert or excise DNA segments. They are ideal for building stable memory devices and logic gates in genetic circuits [31] [32]. |

| Small RNAs (sRNAs) | Non-coding RNA molecules used for post-transcriptional regulation. They are effective for implementing feedback control with lower metabolic burden than protein-based controllers [26]. |

| Cell-Free Systems (Various Chassis) | Extracts from E. coli, wheat germ, or CHO cells used for rapid, growth-independent circuit prototyping. Each chassis offers unique advantages (e.g., yield, post-translational modifications) [10]. |

| Standardized Part Libraries | Collections of well-characterized genetic elements (promoters, RBSs, terminators) with known performance data, crucial for modular and predictable circuit design [30]. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Robots (e.g., Opentrons systems) that automate pipetting, drastically improving throughput and reducing human error in assay setup and reagent dispensing [27]. |

| NTU281 | NTU281, MF:C25H31N2O6S+, MW:487.6 g/mol |

| HDHD4-IN-1 | HDHD4-IN-1, MF:C12H22NO11P, MW:387.28 g/mol |

Proven Protocols and AI-Driven Methods for Enhanced Consistency

Optimized Step-by-Step Protocols for Reducing Variability in E. coli Extract Preparation

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most critical factor to control when preparing E. coli extract to minimize batch-to-batch variability? Research indicates that consistent lysis efficiency and precise magnesium ion (Mg²âº) concentration in the reaction mixture are among the most critical factors [16] [33]. Inadequate lysis leads to low yields, while over-lysing can inactivate crucial translational components. Furthermore, the optimal Mg²⺠concentration can vary between lysate batches, and small pipetting errors can have major effects on protein yields [16].

My cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) yields are inconsistent, even though I follow the same protocol. What could be wrong? Beyond lysis and Mg²âº, inconsistent cell growth is a common culprit. The physiological state of the cells at harvest profoundly impacts the extract's activity [34] [35]. Ensure cells are harvested at a consistent optical density (OD600) and that growth conditions (temperature, aeration, media) are highly reproducible. Even using cells from non-growing, stressed cultures can produce active extract, but the growth endpoint must be consistent [34].

Are there simpler, high-throughput methods for extract preparation that are still robust? Yes, sonication-based lysis methods have been developed as a robust and scalable alternative to traditional French Press. These methods can produce highly active extracts from culture volumes ranging from 10 mL to 10 L, standardizing the process across labs [33]. The key is to identify and consistently apply the optimal sonication energy input per volume of cell suspension [33].

How can I stabilize my CFPS reactions? Using a lower ratio of feed solution to lysate in the reaction has been shown to make the system more stable to fluctuations in Mg²⺠concentration, thereby reducing variability [16]. Additionally, employing energy regeneration systems like creatine phosphate/creatine kinase can help maintain homeostasis and extend reaction duration [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low or Inconsistent Protein Yield

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Consistently low yield across all batches | Inefficient cell lysis [33] | Calibrate lysis method. For sonication, optimize total energy input (Joules) per mL of cell suspension [33]. |

| High variability in yield between batches | Inconsistent cell growth physiology at harvest [34] | Standardize growth protocol: use the same media, harvest at the same OD600, and ensure consistent incubation time. |

| Batch-to-batch variability in lysate activity | Suboptimal Mg²⺠concentration in the reaction [16] | Titrate Mg²⺠concentration for each new lysate batch. Use a lower feed-to-lysate ratio to improve stability to Mg²⺠changes [16]. |

| High initial yield that decreases over time | Depletion of energy substrates [34] | Use a robust energy regeneration system (e.g., creatine phosphate/creatine kinase) and ensure sufficient concentration of amino acids [36]. |

Problem: Issues with Cell Lysis and Extract Preparation

| Step | Challenge | Solution for Standardization |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture | Inconsistent pre-lysis biomass | Grow cells in a rich, defined medium (e.g., 2xYTPG) [34] [35]. Monitor growth and harvest at a specific, consistent OD600. |

| Cell Lysis | Variable efficiency; requires specialized equipment | Adopt a sonication protocol. Determine the optimal energy input (Joules) for your strain and volume, and use short burst/cooling cycles (e.g., 10s on/10s off) to avoid heat inactivation [33]. |

| Post-Lysis | Presence of ribosome hibernation factors (e.g., 100S dimers) from stationary phase cells | Check ribosome profiles via sucrose gradient centrifugation. Control culture conditions to prevent hibernation factor expression [34]. |

The following table consolidates key parameters from research on standardizing E. coli extract preparation.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Reducing Variability in E. coli Extract Preparation

| Parameter | Optimal Range / Condition | Impact on Variability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg²⺠Concentration | Must be optimized per batch; higher optimum can be stabilizing. | Small pipetting errors can cause major yield differences. Titration is critical [16]. | [16] |

| Feed-to-Lysate Ratio | Lower ratio (e.g., lower than typical) | Makes system more robust to variations in Mg²⺠concentration [16]. | [16] |

| Sonication Energy | Strain and volume-specific (e.g., ~309 J for 0.5 mL, ~556 J for 1.5 mL of BL21) | Must be optimized; too little fails to lyse cells, too much inactivates machinery [33]. | [33] |

| Cell Harvest Point | Mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 3) or consistent stationary phase (after 15h) | Using a defined and consistent harvest point, even in stationary phase, is key to reproducibility [34] [33]. | [34] [33] |

| Energy Regeneration | Creatine phosphate (e.g., 60 mM) / Creatine kinase | Provides a consistent, exogenous energy source, reducing reliance on variable endogenous metabolism [34]. | [34] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for E. coli Extract Preparation and CFPS

| Reagent | Function in the Protocol | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 2x YTPG Medium | A nutrient-rich growth medium for cultivating E. coli to high density. | Promotes fast growth and high ribosome content, leading to more active extracts [34] [35]. |

| Sonication Equipment | Used for physical cell disruption in high-throughput protocols. | Delivers controllable and scalable lysis. Requires optimization of energy input to prevent catalyst inactivation [33]. |

| S30 Buffer | Standard buffer for resuspending cell pellets and dialysis of the extract. | Contains Mg²⺠and other salts essential for stabilizing the translational machinery during preparation [33]. |

| Creatine Phosphate & Kinase | An exogenous energy regeneration system. | Regenerates ATP from ADP, fueling extended protein synthesis and standardizing energy supply across batches [34]. |

| T7 RNA Polymerase | A highly specific and efficient polymerase for driving transcription. | Decouples transcription from endogenous E. coli RNA polymerase, simplifying reaction optimization [36] [34]. |

| (R)-ND-336 | (R)-ND-336, MF:C16H18ClNO3S2, MW:371.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| RWJ-58643 | RWJ-58643, CAS:287183-00-0, MF:C20H26N6O4S, MW:446.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

The following diagrams outline optimized and standardized protocols for extract preparation.

Standardizing Reagent Formulation and Master Mix Assembly

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers address the critical challenge of batch-to-batch variability, specifically within the context of optimizing cell-free system performance.

Quantitative Data on Variability in Cell-Free Systems

Understanding the typical scope of variability is crucial for diagnosing issues in your experiments. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from published research on Cell-Free Expression (CFE) systems.

Table 1: Documented Sources and Magnitude of Variability in CFE Systems

| Source of Variability | Documented Impact / Variability Range | Key Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-lab (Same Operator) | 6-10% variability [37] | Across different days and batches of material [37] |

| Inter-lab (Shared Materials) | High variability reported [37] | Using common materials shared between laboratories [37] |

| Batch-to-Batch (Materials) | High variability reported [37] | Different batches of CFE lysates and materials within the same lab [37] |

| Impact on Circuit Complexity | Consistent qualitative performance for simpler circuits; performance varied considerably for more complex circuits [37] | DNA titrations of seven genetic circuits of increasing complexity [37] |

Experimental Protocols for Reducing Variability

Implementing standardized and optimized protocols is the most effective strategy to minimize batch-to-batch variability. The following sections provide detailed methodologies.

Protocol for Consistent Cell-Free Lysate Preparation

A core source of variability in CFE systems stems from the preparation of the cellular lysate. This protocol outlines critical control points based on established methods [37] [35].

Key Steps:

Host Cell Culturing:

- Medium: Use a nutrient-rich medium like 2x Yeast Extract Tryptone (2xYT) [37] [35].

- Supplementation: Add phosphate buffers (e.g., 40 mM dibasic phosphate, 22 mM monobasic phosphate) to stabilize pH and reduce phosphatase activity [37] [35].

- Growth Phase: Harvest cells during exponential growth. Critical Point: Achieve a high growth rate, not just high cell mass, as faster-growing cells contain more ribosomes per unit mass, which is essential for efficient translation [35]. Harvest at an OD600 of ~1.6 [37].

Cell Lysis and Lysate Processing:

- Lysis Method: Use a consistent, high-efficiency method such as high-pressure homogenization (e.g., 16,000 psi) [37] or French Press (e.g., 14,000 psi) [37].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate to remove cellular debris.

- Run-off Reaction: Incubate the clarified lysate at 37°C with shaking for ~90 minutes to degrade endogenous mRNA [37].

- Dialysis: Dialyze the lysate against a suitable buffer (e.g., S30B buffer) for approximately 1 hour to remove small metabolites [37].

- Aliquoting and Storage: Flash-freeze aliquots in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C [37]. Test a portion for protein content using a Bradford assay [37].

Protocol for "Cellular Reagents" to Minimize Variability

Using dried, engineered bacteria ("cellular reagents") as a source of enzymes can bypass the need for protein purification and reduce cold-chain-related variability [38].

Basic Protocol 1: Preparation of Cellular Reagents [38]

- Transformation: Transform an appropriate E. coli strain (e.g., BL21(DE3) for T7-based expression) with your protein expression plasmid.

- Culture and Induction: Grow cultures in liquid medium with antibiotics. Induce protein expression under pre-optimized conditions (e.g., specific inducer concentration, temperature, and duration).

- Cell Collection: Pellet the induced bacteria by centrifugation.

- Drying: Wash the cell pellet and resuspend. Aliquot the suspension and dry overnight at 37°C in the presence of a chemical desiccant like calcium sulfate. The resulting dry pellets are stable at ambient temperatures for months.

Protocol for Master Mix Assembly

Standardizing the assembly of the master mix is critical for reaction-to-reaction consistency.

- Component Quality: Use high-quality, nuclease-free water and molecular biology-grade reagents.

- Thawing and Mixing: Thaw all components completely on ice and mix them thoroughly by vortexing followed by a brief centrifugation before use.

- Assembly Order: Follow a consistent order of addition. A common sequence is: nuclease-free water, buffer, nucleotide mix, amino acid mix, energy solution, lysate, and finally DNA template.

- Avoiding Contamination: Use dedicated filtered pipette tips and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of components. Prepare a master mix without the DNA template for multi-sample reactions to ensure consistency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Familiarity with core reagents and their functions is essential for troubleshooting.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cell-Free Expression Systems

| Reagent / Component | Function / Description | Considerations for Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Lysate (S30 Extract) | Provides the core cellular machinery (ribosomes, enzymes, tRNAs) for transcription and translation [35]. | The single largest source of variability. Strict adherence to a standardized preparation protocol is critical [37]. |

| Energy Mix | Supplies ATP, GTP, and other energy sources to fuel the reaction. Often includes a buffer like HEPES (e.g., 700 mM, pH 8) [37]. | Concentration and pH must be highly consistent. Aliquot to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Amino Acid Mixture | The building blocks for protein synthesis [37]. | Ensure it is complete and free of contamination. Prepare large, single-use batches if possible. |

| DNA Template | The plasmid or linear DNA encoding the gene of interest. | Quality and quantity are crucial. Use reliable midi- or maxi-prep kits and quantify accurately [37]. |

| Cellular Reagents | Dried, engineered bacteria expressing a protein of interest (e.g., polymerase), used directly without purification [38]. | Reduces variability from protein purification and cold chain failures. Enables local reagent production [38]. |

| Tyrosinase-IN-28 | Tyrosinase-IN-28, MF:C21H22N4O4, MW:394.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CX08005 | CX08005, MF:C28H39NO4, MW:453.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Common Variability Issues

My protein yield is low or inconsistent between batches. What should I check first?

- Investigate your lysate preparation. This is the most common source of variability. Ensure host cell culturing conditions are strictly reproducible, focusing on achieving a consistently high growth rate, not just high cell mass [35]. Verify that lysis efficiency (e.g., pressure for homogenization) is consistent every time [37].

- Audit your master mix assembly. Check that the order of addition and mixing steps are rigorously followed. Confirm that all pipettes are calibrated and that reagents are thawed completely and mixed properly before use. Inconsistent pipetting is a frequent culprit.

My complex genetic circuit fails to perform as expected, even with standardized reagents.

- Consider moving beyond standardization to robust design. Research indicates that while simpler circuits show consistent qualitative performance across variable conditions, more complex circuits can show significant functional differences [37].

- Explore engineering solutions. One promising approach is to design circuits with inherent robustness, such as feedback controller circuits, which have been shown to help mitigate the impact of CFE reaction variability [37].

I observe high variability between technical replicates using the same master mix.

- Review your pipetting technique and reagent homogeneity. Ensure the master mix is mixed thoroughly before aliquoting. Use reverse pipetting for viscous solutions.

- Implement stringent controls. Always include positive and negative controls in every run to distinguish between technical errors and true experimental outcomes [39].

- Aliquot reagents. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles of any core component (lysate, energy mix, etc.), as this can degrade their activity. Create single-use aliquots wherever possible.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can data from variable CFE batches still be used for qualitative analysis?

Yes, in many cases. Studies show that although raw activity (e.g., absolute protein yield) can vary widely between batches, normalizing the data within each circuit across conditions can reveal reasonably consistent qualitative performance for simpler genetic circuits [37]. This makes normalized, relative comparisons (e.g., Promoter A is stronger than Promoter B) more reliable than absolute measurements.

What is the simplest change I can make to improve reproducibility?

Meticulously standardize the growth conditions of the cells used for lysate preparation. The health and growth rate of the source cells profoundly impact the quality and performance of the final lysate [35]. Using a defined, rich medium like 2xYT and strictly controlling the growth phase at harvest (e.g., OD600 ~1.6) is a highly effective starting point [37].

Are there alternatives to traditional purified reagents that might be more consistent?

Yes, consider using "cellular reagents" – dried bacteria engineered to overexpress a specific protein [38]. These can be used directly in reactions without purification. This approach minimizes variability introduced by protein purification processes and the cold chain, as the dry pellets are stable at ambient temperature [38].

The Rise of Automated DBTL Cycles for Systematic Optimization

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using an automated DBTL cycle over a traditional manual approach? Automated DBTL cycles significantly accelerate strain development by integrating robotics, machine learning (ML), and data management systems. This automation reduces human error, increases throughput, and uses data from each cycle to intelligently design the next, leading to faster convergence on optimal strains [40] [41]. For example, one study reported a 500-fold improvement in pathway performance after just two automated DBTL cycles [40].

Q2: Our ML recommendations are not leading to improved production. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge. The issue often lies in the training data or model choice.

- Low-Data Regime: ML models need sufficient data. In early cycles with few strains (<100), ensemble methods like Gradient Boosting and Random Forest have been shown to outperform other models [42].

- Training Set Bias: If your initial library of built strains does not adequately cover the design space, the model cannot learn accurate relationships. Ensure your initial DBTL cycle tests a diverse set of designs [42].

- Input-Output Relationship: The chosen input features (e.g., proteomics data, promoter combinations) must be predictive of the output (production titer). If the underlying biology is not captured, predictions will fail [43].

Q3: How can we reduce batch-to-batch variability in cell-free expression systems used in the 'Test' phase? Batch-to-batch variability in cell-free lysates is a major source of experimental noise. To address this:

- Use Defined Systems: Consider adopting the PURE (Protein synthesis Using Recombinant Elements) system, a fully defined cocktail of purified components, to eliminate extract-based variability [44] [1].

- AI-Optimized Buffers: Actively research AI and active learning approaches to optimize the composition of the cell-free reaction buffer, which has been shown to significantly improve protein production consistency [1].

- Standardized Protocols: Implement strict, standardized protocols for host cell growth and lysate preparation, focusing on maintaining consistent cell health and growth rates [44].

Q4: What is a "knowledge-driven" DBTL cycle and how does it help? A knowledge-driven DBTL cycle incorporates upstream in vitro experiments, such as testing enzyme expression and activity in cell lysates, before moving to in vivo engineering. This provides mechanistic insights and prioritizes the most promising engineering targets for the first in vivo cycle, saving time and resources that might otherwise be spent on non-functional designs [45].

Q5: How many strains should we build in the first DBTL cycle? Simulation studies suggest that when the total number of strains you can build is limited, it is more favorable to start with a larger initial DBTL cycle rather than distributing the same number of strains evenly across multiple cycles. A larger initial data set provides a better foundation for the machine learning model to learn from in subsequent cycles [42].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Failure in DNA Assembly (e.g., Gibson Assembly)

- Symptoms: No colonies after transformation, or sequencing reveals empty backbones.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Incomplete vector linearization. Residual methylated template vector outcompetes the assembled product.

- Solution: Increase DpnI digestion time (e.g., to 1 hour) to degrade more of the template. Use a minimal amount of template DNA for the linearization PCR [46].

- Cause 2: Overly complex assembly with too many long fragments.

- Solution: Simplify the design. Consider ordering the entire construct as a synthetic gene fragment from a commercial vendor to bypass the assembly hurdle entirely [46].

- Cause 3: Short incubation time during assembly reaction.

- Solution: Increase the Gibson Assembly incubation time from 15-30 minutes to 60 minutes [46].

- Cause 1: Incomplete vector linearization. Residual methylated template vector outcompetes the assembled product.

Problem: High "Leaky" Expression (Background Signal) in Biosensors

- Symptoms: Detectable reporter signal (e.g., luminescence) even in the absence of the target molecule.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Promoter choice. Some native promoters have high basal activity.

- Solution: Select promoters with inherently low basal expression levels. Test multiple candidate promoters [46].

- Cause 2: High plasmid copy number.

- Cause 3: Lack of sufficient transcriptional repression.

- Solution: Ensure all necessary regulatory elements (e.g., LacI, TetR) and their binding sites are correctly positioned in the design [46].

- Cause 1: Promoter choice. Some native promoters have high basal activity.

Table 1: Machine Learning Model Performance in Automated DBTL Cycles

| Model / Factor | Performance / Effect | Experimental Context | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting | Outperforms other models with limited data [42] | Simulated metabolic pathway optimization | Robust to training set bias and experimental noise. |

| Random Forest | Outperforms other models with limited data [42] | Simulated metabolic pathway optimization | Effective for early DBTL cycles with small datasets. |

| Initial Cycle Size | Larger initial cycle is favorable with a limited total build budget [42] | Simulated multi-cycle optimization | Provides a richer dataset for ML models to learn from in subsequent cycles. |

| Vector Copy Number | Strongest significant effect on pinocembrin production (P = 2.00 × 10â»â¸) [40] | Flavonoid production in E. coli | Higher copy number (ColE1) positively correlated with production. |

| Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) | 106% increase in tryptophan production from base strain [43] | Yeast metabolic engineering | ML-guided recommendations successfully improved productivity. |

Table 2: Production Titer Improvements via Automated DBTL Cycles

| Target Compound | Host | Key DBTL Strategy | Reported Titer Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2S)-Pinocembrin | E. coli | Automated DBTL with DoE library reduction | 500-fold increase after 2 cycles [40] | [40] |

| Dopamine | E. coli | Knowledge-driven DBTL with RBS engineering | 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L (2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement) [45] | [45] |

| Tryptophan | Yeast | ML-guided recommendations with ART | 106% increase from base strain [43] | [43] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols