Systems vs Synthetic Biology: A Strategic Guide for Next-Generation Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of systems biology and synthetic biology, two transformative disciplines reshaping biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Systems vs Synthetic Biology: A Strategic Guide for Next-Generation Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of systems biology and synthetic biology, two transformative disciplines reshaping biomedical research and therapeutic development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of each field, from the analytical, network-based approach of systems biology to the engineering-driven, constructive paradigm of synthetic biology. The article delves into their distinct methodologies and real-world applications in target identification, drug production, and advanced cell therapies. It further addresses key implementation challenges and optimization strategies, culminating in a direct comparative analysis of their performance, strengths, and synergistic potential for creating more effective and precise medical treatments.

Core Philosophies: Deconstructing Complexity vs. Constructing Function

Systems biology is an interdisciplinary field dedicated to comprehensively characterizing biological entities by quantitatively integrating cellular and molecular information into predictive models [1]. Unlike traditional molecular biology, which investigates molecules and pathways in isolation, systems biology is characterized by the development and application of mathematical, computational, and synthetic modeling strategies to understand the complex dynamics and organization of interconnected biological components [2]. This approach represents a fundamental shift from reductionist strategies toward a holistic perspective that seeks to understand how emergent properties arise from the interactions of system components [2]. As the analytical counterpart to synthetic biology's design-focused approach, systems biology aims to improve our ability to understand and predict living systems by capitalizing on large-scale data production and cross-fertilization between biology, physics, computer science, mathematics, chemistry, and engineering [2].

The philosophical foundation of systems biology engages directly with one of the oldest scientific discussions: reductionism versus holism [2]. Proponents of systems biology stress the necessity of a perspective that goes beyond the scope of molecular biology to account for the dynamics and organization of many interconnected components [2]. While molecular biology has been extremely successful in generating knowledge on biological mechanisms through decomposition and localization strategies, its detailed study of molecular pathways has revealed dynamic interfaces and crosslinks between processes that were previously assigned to distinct mechanisms [2]. Systems biology addresses this complexity through network modeling and computational simulations that provide strategies for recomposing findings in the context of larger systems [2].

Core Methodological Frameworks in Systems Biology

Theoretical and Pragmatic Approaches

Systems biology research is broadly divided into two complementary streams: the systems-theoretical and pragmatic approaches [2]. The systems-theoretical stream is historically related to the initial use of the term 'systems biology' in 1968, denoting the merging of systems theory and biology [2]. This perspective views systems biology as an opportunity to revive important theoretical questions that stood in the shadow of experimental biology's success, including fundamental questions about what characterizes living systems and whether generic organizational principles can be identified [2].

In contrast, the pragmatic stream (sometimes called molecular systems biology) views systems biology as a powerful extension of molecular biology and a successor to genomics [2]. Practitioners within this field relate the emergence of systems biology to the production of data within genomics and other high-throughput technologies from the late 1990s onward [2]. A third dimension recognized by some researchers includes omics-disciplines as a distinct root of systems biology due to the impact of data-rich modeling strategies on the field's development [2].

Quantitative Analytical Techniques

Systems biology employs rigorous computational models and quantitative analyses to decipher complex biological interactions [1]. The quantitative analysis of biological processes typically involves automated image analysis followed by rigorous quantification of the biological process under investigation [3]. Depending on the experiment's readout, this quantitative description may include size, density, and shape characteristics of cells and molecules [3]. For dynamic processes, tracking moving objects yields distributions of instantaneous speeds, turning angles, and interaction frequencies [3].

Table 1: Core Quantitative Methods in Systems Biology

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Primary Applications | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Analysis | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), Bayesian network modeling, Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Analysis [1] | Elucidating gene regulatory networks, protein interactomes, metabolic pathways [1] | Network architectures, hub identification, functional modules |

| Multi-Omics Integration | Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL), methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTL) integration [1] | Identifying SNPs and genes related to diseases, understanding genetic pathogenesis [1] | Comprehensive molecular profiles, biomarker identification |

| Computational Modeling | Artificial intelligence, machine learning, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), random forest [1] | Forecasting genetic alterations, evaluating protein interactions, classifying cells [1] | Predictive models, risk assessments, treatment response predictions |

| Single-Cell Analysis | Single-cell sequencing technologies combined with AI/ML algorithms [1] | Exploring cellular diversity, extracting biological information from individual cells [1] | Cell-type identification, rare cell population detection |

A key innovation in systems biology methodology is the integration of qualitative and quantitative data in parameter identification for models [4]. In this approach, qualitative data are converted into inequality constraints imposed on model outputs [4]. These inequalities are used along with quantitative data points to construct a single scalar objective function that accounts for both datasets [4]. The combined objective function takes the form:

f_tot(x) = f_quant(x) + f_qual(x)

Where f_quant(x) is a standard sum of squares over all quantitative data points, and f_qual(x) is a penalty function based on constraint violations from qualitative data [4]. This approach has been successfully applied to parameterize models ranging from Raf activation to cell cycle regulation in yeast, incorporating both quantitative time courses and qualitative phenotypes of mutant strains [4].

Network Analysis: The Structural Foundation of Emergent Properties

Network Architectures in Biological Systems

Network approaches form the backbone of systems biology representation and analysis [2]. What distinguishes systems biology can be understood through the characteristics of its representational styles, which typically display interactions between vast numbers of molecular components as abstract networks of interconnected nodes and links [2]. This representational shift is epistemically significant because it highlights an increasing focus on the organizational structure of the system as a whole [2].

Systems biologists distinguish between two major classes of networks based on their connectivity distribution [2]. Exponential networks are largely homogeneous with approximately the same number of links per node, making nodes with many links unlikely [2]. In contrast, scale-free networks are inhomogeneous, with most nodes having only a few links but some nodes (called hubs) having a large number of connections [2]. Interestingly, many real-world networks including social networks, the World Wide Web, and regulatory networks in biology display scale-free architectures [2].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Biological Network Properties

| Network Property | Exponential Network | Scale-Free Network | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity Distribution | Homogeneous | Inhomogeneous with hubs | Hubs represent critical regulatory elements |

| Error Tolerance | Low robustness against random node failure | High robustness against random failure | Biological systems remain functional despite random mutations |

| Attack Vulnerability | Distributed vulnerability | Fragile to targeted hub attacks | Critical nodes represent potential therapeutic targets |

| Path Length | Longer average path length | Small average path length | Efficient information flow and coordinated regulation |

| Examples | Synthetic networks | Protein-protein interactions, metabolic pathways [2] | Evolutionary advantages for scale-free architecture |

The scale-free structure provides functional advantages including small average path length between any two nodes, enabling capacities for coordinated regulation throughout the network [2]. Additionally, scale-free networks exhibit high error tolerance—robustness against failure of random nodes and links (e.g., random gene deletion) [2]. However, the functional importance of hubs in scale-free networks also results in fragility to attacks on central nodes [2]. Similarly, bow-tie network structures connect many inputs and outputs through a central core and have been associated with efficient information flow but also with fragility toward perturbations of intermediate core nodes [2].

Network Motifs and Functional Modules

A significant advancement in network analysis has been the identification of network motifs—patterns of interaction that recur in many different contexts within a network [2]. By comparing biological networks to random networks, researchers have discovered that certain circuit patterns occur more frequently than expected by chance [2]. These statistically significant circuits are defined as network motifs and represent fundamental functional units within larger networks [2].

Two prominent examples of network motifs are the coherent and incoherent feedforward loops (cFFL and iFFL) [2]. Mathematical analysis suggests that the cFFL may function as a sign-sensitive delay element that filters out noisy inputs for gene activation [2]. In contrast, the regulatory function of the iFFL was hypothesized to be an accelerator that creates a rapid pulse of gene expression in response to an activation signal [2]. These predicted functions have been experimentally demonstrated in living bacteria, illustrating how systems biology approaches can generate testable hypotheses about emergent functional properties [2].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Integrated Qualitative-Quantitative Parameter Identification

A powerful methodological framework in systems biology combines qualitative and quantitative data for parameter identification [4]. This approach formalizes qualitative biological observations as inequality constraints on model outputs, which are then combined with quantitative data points to construct a single objective function for parameter optimization [4]. The approach is particularly valuable when quantitative time-course data are unavailable, limited, or corrupted by noise [4].

The parameter identification process involves minimizing a total objective function with contributions from both data types [4]:

f_tot(x) = f_quant(x) + f_qual(x)

Where f_quant(x) is a standard sum of squares over all quantitative data points, and f_qual(x) is constructed as a static penalty function that imposes costs proportional to the magnitude of constraint violations derived from qualitative data [4]. This framework enables the incorporation of diverse data types, including categorical characterizations such as activating/repressing, oscillatory/non-oscillatory, or lower/higher relative to control [4].

Multi-Omics Data Integration Framework

The integration of multi-omics data represents a cornerstone of modern systems biology [1]. This approach involves combining heterogeneous and large datasets from various omics studies—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to gain a comprehensive and holistic understanding of biological systems [1]. The challenge is not only conceptual but practical due to the sheer volume and diversity of the data [1].

A representative example of multi-omics integration comes from a study that combined genome-wide association studies (GWAS), expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL), and methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTL) data to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and genes related to different types of strokes [1]. This study explored genetic pathogenesis based on loci, genes, gene expression, and phenotypes, identifying 38 SNPs affecting the expression of 14 genes associated with stroke [1]. Such integrated approaches demonstrate how systems biology can uncover emergent properties not visible when examining individual data types in isolation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Biology

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools in Systems Biology

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms | Single-cell RNA sequencing, Whole-genome sequencing | Comprehensive characterization of molecular pools | Generating omics data for transcriptomics, genomics [1] |

| Proteomics Analysis Tools | Mass spectrometry, Protein arrays | Quantification of protein expression and interactions | Proteomic studies, protein-protein interaction networks [1] |

| Computational Modeling Software | JAXLEY differentiable simulator [5], Bayesian network tools [1] | Predictive modeling and parameter optimization | Simulating biological processes, parameter identification [5] [1] |

| Data Integration Platforms | Omnireg-GPT [5], Multi-omics integration pipelines | Analysis of long-range genomic regulation, combining heterogeneous datasets | Understanding regulatory features across long DNA sequences [5] |

| Image Analysis Systems | Automated cell tracking, Quantitative shape analysis | Extraction of quantitative parameters from microscopy data | Characterizing cell migration, shape dynamics [3] |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Integration

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) represents one of the most significant emerging trends in systems biology [1]. These computational approaches are revolutionizing the field by enabling researchers to process extensive datasets, identify potential drug targets, predict compound efficacy, and categorize cells using omics data [1]. Specific applications include using neural networks such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for sequence alignment, gene expression profiling, and protein structure prediction [1]. Random forest algorithms are applied to classification and regression problems, while clustering algorithms are essential for examining unstructured data to reveal underlying biological processes at the genomic level [1].

Recent advances include differentiable simulators like JAXLEY, which leverage automatic differentiation and GPU acceleration to make large-scale biophysical neuron model optimization feasible [5]. This approach uniquely combines biological accuracy with advanced machine-learning optimization techniques, allowing for efficient hyperparameter tuning and exploration of neural computation mechanisms at scale [5]. Similarly, foundation models such as OmniReg-GPT with hybrid local-global attention architectures enable efficient analysis of multi-scale regulatory features across long DNA sequences [5].

Single-Cell Systems Biology

The advent of single-cell sequencing technologies has elevated systems biology by enabling detailed exploration of intricate interactions at the individual cell level [1]. This advancement transcends the scope of conventional omics techniques by tackling the inherent cellular diversity fundamental to cell biology [1]. Merging AI and ML with single-cell omics is particularly powerful, as AI-driven algorithms can accurately manage the vast amounts of data produced by single-cell technologies, facilitating the extraction of biological information and integration of different omics datasets [1].

Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite significant advances, systems biology faces several ongoing challenges [1]. These include difficulties in integrating diverse data types and computational models, reconciling bottom-up and top-down approaches, and calibrating models amidst biological noise [1]. Multi-omics integration also presents specific hurdles related to data heterogeneity and scale [1].

Future directions include developing advanced computational tools, pursuing comprehensive models of biological systems, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, and adhering to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) for data sharing [1]. The field continues to aim toward deepening the fundamental understanding of biological systems while improving predictive modeling capabilities [1]. As systems biology matures, its integration with synthetic biology creates a powerful cycle of analysis and design that promises to transform our approach to understanding and engineering biological systems [2] [6].

Synthetic biology represents a paradigm shift in the life sciences, moving beyond the analytical approach of traditional biology to embrace the engineering principles of design and construction. This emerging discipline is characterized by the development and application of mathematical, computational, and synthetic modeling strategies to design and construct new biological parts, devices, and systems [2]. While systems biology focuses on understanding natural biological systems through analysis of their components and interactions, synthetic biology aims to create novel biological functions through purposeful design [2]. This complementary relationship positions synthetic biology as a true engineering discipline for biology, with the potential to revolutionize industries ranging from healthcare and agriculture to energy and environmental management.

The foundational principle of synthetic biology is the application of engineering concepts—standardization, abstraction, modularity, and predictability—to biological systems. This approach recognizes that the complexity of biological systems necessitates computational and mathematical strategies to enable prediction and design [2]. By treating biological components as parts that can be assembled into increasingly complex systems, synthetic biologists aim to create a rigorous framework for biological engineering that parallels the maturity of other engineering disciplines.

Philosophical Foundations: Contrasting Systems and Synthetic Biology Approaches

The relationship between systems biology and synthetic biology represents one of the most significant philosophical developments in contemporary life sciences. Systems biology emerged as a response to the limitations of reductionist strategies in molecular biology, focusing instead on the dynamics and organization of interconnected components within biological systems [2]. This approach utilizes network modeling and computational simulations to study integrated systems and their emergent properties, with practitioners often emphasizing the need to go beyond what they perceive as reductionist strategies in molecular biology [2].

Synthetic biology, by contrast, focuses on the complementary aim of designing biological systems rather than merely understanding them. Where systems biology analyzes existing biological networks, synthetic biology constructs new ones. This distinction has been characterized as analysis versus synthesis, or knowledge-driven versus application-driven epistemologies [2]. However, philosophers of science examining research practice have argued that understanding and design are often interdependent in these fields, and that no simple distinction between basic and applied science adequately captures their relationship [2].

Network Approaches in Biological Engineering

A key area where systems and synthetic biology converge is in their use of network approaches. Systems biology research has revealed common patterns in biological networks, including scale-free network architectures and multi-level hierarchies [2]. These network structures exhibit distinct functional properties: scale-free networks, for instance, demonstrate high error tolerance against random failures but particular fragility when central hubs are targeted [2].

Synthetic biologists leverage this understanding when designing genetic circuits. The concept of network motifs—patterns of interaction that recur in many different contexts—provides a foundation for designing predictable biological systems [2]. Examples include:

- Coherent feedforward loops (cFFL): Serve as sign-sensitive delay elements that filter out noisy inputs for gene activation

- Incoherent feedforward loops (iFFL): Function as accelerators that create rapid pulses of gene expression in response to activation signals [2]

These motifs function similarly to electronic circuits, providing synthetic biologists with reusable design patterns that exhibit predictable behaviors when implemented in living systems like bacteria [2].

Table 1: Key Differences Between Systems Biology and Synthetic Biology Approaches

| Aspect | Systems Biology | Synthetic Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Understanding natural systems | Designing artificial biological systems |

| Methodology | Analysis, modeling, simulation | Design, construction, testing |

| Key Questions | How do biological systems function as integrated networks? | How can we build biological systems with desired functions? |

| Relationship to Reductionism | Response to reductionism, emphasizing holism | Application of engineering principles to biological components |

| Network Perspective | Analyzes existing network architectures | Designs and implements novel network architectures |

| Epistemology | Knowledge-driven | Application-driven |

Core Engineering Frameworks and Methodologies

The Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle

The engineering process in synthetic biology follows an iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle that enables continuous improvement of biological systems [7]. This framework provides structure to biological engineering, allowing for systematic refinement of designs:

- Design Phase: Researchers use computational tools to design genetic constructs, drawing from libraries of standardized biological parts. This phase includes specifying DNA sequences, selecting regulatory elements, and modeling predicted system behavior.

- Build Phase: Designed constructs are synthesized and assembled into host organisms using DNA synthesis and assembly techniques [8].

- Test Phase: The constructed biological systems are characterized through experimental assays to measure performance against design specifications.

- Learn Phase: Data from testing informs subsequent design iterations, creating a cycle of continuous improvement.

This framework enables synthetic biologists to treat biological engineering with the same systematic approach used in other engineering disciplines, progressively increasing the complexity and reliability of designed biological systems.

Standardized Visualization: SBOL Visual

Engineering disciplines require standardized visual languages for effective communication of designs, and synthetic biology has developed SBOL Visual to fulfill this need [9]. This standardized visual language allows biological engineers to communicate both the structure of nucleic acid sequences they are engineering and the functional relationships between features of these sequences [9].

SBOL Visual version 2 provides glyphs for representing various biological components and interactions [9]:

- Sequence feature glyphs: Represent promoters, coding sequences, terminators, and other nucleic acid elements

- Molecular species glyphs: Represent proteins, non-coding RNAs, small molecules, and other classes of molecules

- Interaction glyphs: Use arrows to indicate functional relationships like genetic production, inhibition, and degradation

This standardization enables clear communication between researchers and reduces the likelihood of misinterpretation, mirroring the role of circuit diagrams in electrical engineering or schematic plans in mechanical engineering [9].

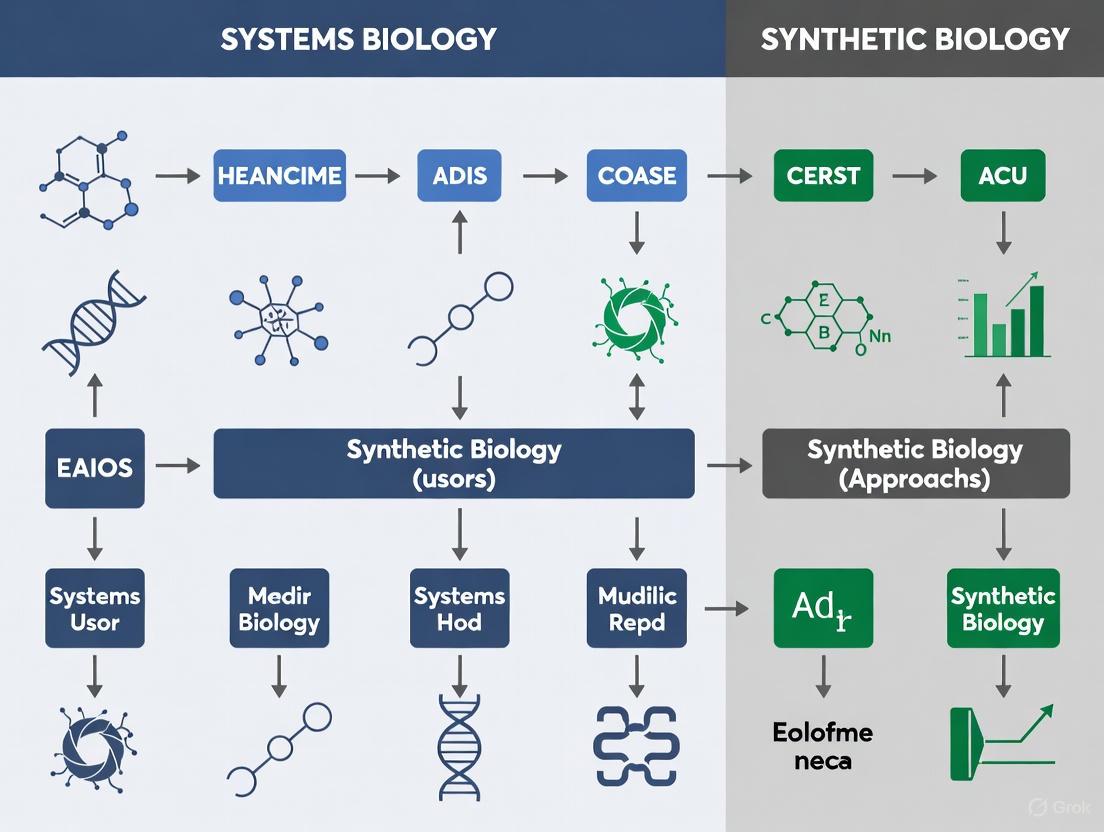

Diagram 1: Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, the core engineering framework in synthetic biology that enables iterative improvement of biological designs [7].

Essential Technical Protocols in Synthetic Biology

Gene Synthesis and Assembly Methods

The technical foundation of synthetic biology relies on methods for constructing genetic material. Key protocols include:

Gene Synthesis Techniques:

- Oligonucleotide Synthesis: Building short DNA fragments (typically 60-100 base pairs) using phosphoramidite chemistry

- Gene Assembly: Combining oligonucleotides into longer DNA fragments through methods like polymerase cycle assembly (PCA)

- Error Correction: Using mismatch-binding proteins or column purification to remove erroneous sequences

Modern gene synthesis has advanced significantly, with synthetic genes now ranging from 10² to 10ⶠbase pairs, with the synthesis of complex genomes approaching 10⹠base pairs projected within 10-30 years [8]. Costs have decreased dramatically, falling by 30-50% annually and approaching $0.01 per base pair [8].

Assembly Methods:

- Restriction enzyme-mediated assembly: Uses Type IIS restriction enzymes that cut outside their recognition sites, enabling seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments

- Gibson Assembly: Employs a one-step isothermal reaction that combines exonuclease, polymerase, and ligase activities to assemble multiple overlapping DNA fragments

- Golden Gate Assembly: Utilizes Type IIS restriction enzymes to create standardized, reusable genetic parts that can be efficiently assembled in various combinations

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Standardization of experimental protocols is essential for reproducibility in synthetic biology. Key areas requiring standardized approaches include:

Antibiotic Selection Systems: Synthetic biology relies on selection systems to maintain engineered genetic elements in host organisms. Common antibiotic selection systems include [10]:

Table 2: Common Antibiotic Selection Systems in Synthetic Biology

| Antibiotic | Working Concentration | Mechanism of Action | Resistance Gene | Resistance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | 100 µg/mL | Interferes with bacterial cell wall synthesis | bla (β-lactamase) | Cleaves β-lactam ring of antibiotic |

| Chloramphenicol | 35 µg/mL | Binds to 50S ribosomal subunit, inhibits peptide bond formation | cat (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase) | Acetylates antibiotic, preventing ribosome binding |

| Kanamycin | 50 µg/mL | Binds to 70S ribosomes, causes mRNA misreading | kan (aminoglycoside phosphotransferase) | Phosphorylates and inactivates antibiotic |

| Tetracycline | 10 µg/mL | Binds to 30S ribosome, disrupts codon-anticodon interaction | tet (transporter protein) | Efflux pumps remove antibiotic from cell |

Enabling Technologies and Computational Tools

CRISPR and Genome Engineering Advances

CRISPR-Cas systems have revolutionized synthetic biology by providing unprecedented precision in genome editing [8]. These systems function as programmable nucleases that can be targeted to specific DNA sequences, enabling:

- Gene Knockouts: Precfficient disruption of gene function through introduction of frameshift mutations

- Gene Insertion: Targeted integration of genetic elements into specific genomic loci

- Gene Regulation: CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and activation (CRISPRa) systems for precise control of gene expression

- Multiplexed Editing: Simultaneous modification of multiple genomic locations in a single experiment

The precision and programmability of CRISPR systems have dramatically accelerated the design-build-test cycle, making complex genetic engineering projects more feasible and predictable.

AI and Machine Learning Integration

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are transforming synthetic biology by enhancing prediction and design capabilities [8] [7]. Key applications include:

- Protein Design: Deep learning models like AlphaFold and RFdiffusion enable de novo protein design with atomic-level precision

- Pathway Optimization: Machine learning algorithms predict optimal genetic configurations for maximizing product yield in metabolic engineering

- Automated Strain Engineering: AI-driven platforms analyze high-throughput experimental data to identify genetic modifications that improve host organism performance

Companies like Ginkgo Bioworks have developed large language models specifically for protein design, making these AI tools accessible to researchers through application programming interfaces (APIs) [11].

The Synthetic Biologist's Toolkit

Synthetic biologists utilize a comprehensive suite of tools and technologies for designing, constructing, and testing biological systems:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Synthetic Biology

| Research Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples/Providers |

|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotides & Synthetic DNA | Basic building blocks for genetic circuit construction | Twist Bioscience, Integrated DNA Technologies [12] [11] |

| Cloning Technology Kits | Standardized systems for DNA assembly | New England Biolabs, Thermo Fisher Scientific [12] [13] |

| Chassis Organisms | Host platforms for engineered genetic systems | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, B. subtilis strains [12] |

| Enzymes for DNA Assembly | Specialized enzymes for molecular cloning | Restriction enzymes, ligases, polymerases [12] |

| Antibiotic Selection Systems | Maintenance of engineered genetic elements in host populations | Ampicillin, Kanamycin, Chloramphenicol, Tetracycline [10] |

| DNA Synthesis Platforms | High-throughput synthesis of genetic constructs | Twist Bioscience silicon-based platform [11] |

| Standardized Visual Language | Communication of biological designs | SBOL Visual glyphs [9] |

| Pentane, 2,2'-oxybis- | Pentane, 2,2'-oxybis-|CAS 56762-00-6 | |

| 5-Ethyl-biphenyl-2-ol | 5-Ethyl-biphenyl-2-ol|Research Chemical | 5-Ethyl-biphenyl-2-ol (CAS 92495-65-3) is a biphenyl scaffold for antimicrobial and pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Applications and Impact Across Industries

Healthcare and Pharmaceutical Applications

The healthcare sector represents the largest application area for synthetic biology, with numerous clinical and commercial successes [12] [13]. Key applications include:

Therapeutic Development:

- Engineered Cell Therapies: CAR-T cells for cancer immunotherapy, such as Kymriah and Yescarta [8]

- Semi-synthetic Artemisinin: Development of microbial production platforms for anti-malarial compounds in collaboration with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [11]

- mRNA Vaccine Production: Engineered enzymes for 5'-capping of mRNA, improving the efficiency of RNA-based vaccine production [11]

Diagnostic Applications:

- Biosensors: Engineered biological components that detect disease biomarkers

- Synthetic Biology Platforms: Companies like Codexis engineer optimized enzymes for drug manufacturing, enabling greener, faster, and more cost-effective chemical processes [11]

Sustainable Solutions and Industrial Applications

Synthetic biology enables more sustainable manufacturing processes across multiple industries:

Biofuels and Energy:

- Advanced Biofuels: Engineering microbes to produce sustainable alternatives to petroleum-based fuels

- Bioremediation: Designing organisms that detoxify environmental pollutants [6]

Sustainable Materials:

- Bio-based Chemicals: Companies like Amyris engineer microbes to convert plant sugars into high-value molecules for cosmetics, flavors, and fragrances [11]

- Enzyme-driven Manufacturing: Arzeda designs novel enzymes that replace petrochemical processes with biological alternatives [11]

Table 4: Synthetic Biology Market Forecast by Application (2024-2029)

| Application Segment | Market Size 2024 (USD Billion) | Projected CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | 5.14 [12] | 25.7% [12] | Engineered gene systems, molecular components for disease treatment [12] |

| Industrial Applications | Significant growth projected | High | Sustainable production methods, bio-manufacturing [13] |

| Food & Agriculture | Growing segment | Accelerating | Bioengineered crops, sustainable food production [6] |

| Environmental Applications | Emerging segment | Rapid expansion | Bioremediation, climate change mitigation [6] |

Future Directions and Challenges

Emerging Trends and Technologies

Synthetic biology continues to evolve rapidly, with several key trends shaping its development:

Technology Integration:

- AI-Driven Biodesign: Increasing sophistication of machine learning models for predicting biological system behavior

- Automation and High-Throughput Screening: Robotics and microfluidics enabling rapid testing of thousands of genetic variants [7]

- DNA Data Storage: Using synthetic DNA as an ultra-high-density medium for information storage [11]

Expanding Applications:

- Climate Change Mitigation: Engineering organisms for carbon capture and greenhouse gas reduction [6]

- Sustainable Agriculture: Developing biological solutions for crop protection and enhancement [6]

- Conservation Biology: Applying synthetic approaches to species protection and habitat restoration [6]

Addressing Technical and Ethical Challenges

Despite significant progress, synthetic biology faces several important challenges:

Technical Hurdles:

- Biological Complexity: The unpredictable behavior of biological systems presents ongoing challenges for reliable engineering [12]

- Standardization Needs: Lack of universal standards for biological parts and measurement methods [8]

- Scalability: Difficulties in moving from laboratory-scale demonstrations to industrial production [12]

Ethical and Safety Considerations:

- Biosecurity: Concerns about potential misuse of synthetic biology technologies [7]

- Regulatory Frameworks: Evolving regulations governing genetically modified organisms [12]

- Public Perception: Need for ongoing engagement about the benefits and risks of synthetic biology [12]

Diagram 2: Example of SBOL Visual standardized notation for synthetic biology designs, showing genetic components and their functional relationships [9].

Synthetic biology has firmly established itself as an engineering discipline for designing biological systems, complementing the analytical approaches of systems biology. Through the application of engineering principles—standardization, abstraction, modularity, and iterative design—synthetic biology enables the construction of biological systems with novel functions. The continued maturation of this field, driven by advances in DNA synthesis, genome editing, computational design, and AI integration, promises to transform industries ranging from medicine to manufacturing while addressing pressing global challenges in sustainability and environmental protection.

As the field progresses, the interplay between systems biology and synthetic biology will continue to be essential: systems biology provides the fundamental understanding of natural biological systems that informs design, while synthetic biology tests and extends this understanding through construction of novel systems. This virtuous cycle of analysis and synthesis positions synthetic biology as a cornerstone of 21st-century biotechnology, with the potential to revolutionize how we interact with and harness the power of biological systems.

The quest to understand and engineer biological systems has crystallized around two powerful, complementary paradigms: systems biology and synthetic biology. While both disciplines operate at the intersection of biology and computation, their fundamental philosophies and immediate goals create a productive tension in biomedical research. Systems biology adopts a analytical, top-down approach, seeking to understand, model, and predict the behavior of existing biological networks through comprehensive data integration and computational modeling [14]. In contrast, synthetic biology employs a constructive, bottom-up approach, designing and implementing novel genetic circuits and cellular functions to create programmable biological machines [15].

Despite their philosophical differences, both fields share the ultimate objective of advancing therapeutic development, albeit through divergent pathways. Systems biology aims to deconstruct disease complexity through network analysis and multi-scale modeling to identify critical intervention points [14] [16]. Synthetic biology seeks to reconstruct biological function by assembling standardized biological parts into functional devices for therapeutic applications, biosensing, and bioproduction [15] [17]. This whitepaper examines the comparative goals, methodologies, and applications of these two fields, with particular focus on their respective contributions to predictive modeling and cellular programming in drug discovery and development.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Systems Biology and Synthetic Biology

| Characteristic | Systems Biology | Synthetic Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Analyze and understand natural systems | Design and construct novel biological systems |

| Primary Approach | Top-down, analytical | Bottom-up, engineering-based |

| Key Methodologies | Omics integration, computational modeling, network analysis | Genetic circuit design, standardization, parts assembly |

| Model Outputs | Predictive simulations of system behavior | Programmable cellular machines with defined functions |

| Therapeutic Applications | Target identification, drug combinations, patient stratification | Cellular therapeutics, engineered microbes, biosensors |

Systems Biology: The Predictive Modeling Paradigm

Conceptual Framework and Methodological Foundations

Systems biology operates on the principle that biological functions emerge from complex, dynamic networks of molecular interactions that cannot be fully understood by studying individual components in isolation [14]. This field has evolved substantially with advancements in high-throughput technologies, enabling the generation of massive multi-scale datasets including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [14]. The core methodological framework involves computational integration of these diverse data types to construct predictive models of biological systems, from metabolic pathways to entire cells and tissues.

The fundamental goal of systems biology in drug discovery is to increase probability of success in clinical trials by delivering data-driven matching of the right mechanism to the right patient at the right dose [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing complex diseases where single-target interventions have consistently failed due to biological redundancy and network robustness. Systems biology provides a framework for understanding pleiotropic mechanisms simultaneously contributing to pathological changes and disease progression across a wide spectrum of diseases [14].

Computational Modeling Approaches

Systems biology employs a diverse arsenal of computational modeling techniques, each with distinct strengths and applications:

Mass action and enzyme kinetics-based models represent interactions between molecular species as ordinary differential equations (ODEs) requiring parameter values for concentrations and rate constants [16]. These biochemically detailed kinetic models can simulate dynamic network behavior under various perturbations. For example, Iadevaia et al. developed a mass-action model of IGF-1 signaling in breast cancer with 161 unknown parameters, fitting the model to temporal protein measurements to identify beneficial drug combinations [16].

Network motif analysis identifies recurring interaction patterns within larger networks that perform specific information-processing functions, providing insights into signal amplification, feedback control, and network robustness properties critical for understanding drug response and resistance mechanisms [16].

Statistical association-based models leverage machine learning and correlation analyses to extract patterns from high-dimensional biological data without requiring detailed mechanistic understanding, enabling biomarker discovery and patient stratification based on molecular signatures [14] [16].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Drug Combination Synergy

| Method | Formula | Interpretation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loewe Additivity | ( CI=\frac{[CA]}{[IA]}+\frac{[CB]}{[IB]} ) | CI<1: Synergy; CI=1: Additivity; CI>1: Antagonism | Drugs with similar mechanisms [16] |

| Bliss Independence | ( ET=EA×E_B ) | Experimental < Expected: Synergy; Experimental > Expected: Antagonism | Drugs with independent mechanisms [16] |

Experimental Workflow for Network Modeling and Drug Combination Prediction

The following diagram illustrates a standardized workflow for developing predictive models of signaling networks and applying them to drug combination discovery:

Diagram 1: Systems Biology Modeling Workflow (81 characters)

Synthetic Biology: The Programmable Cellular Machines Paradigm

Conceptual Framework and Engineering Principles

Synthetic biology represents a fundamental shift from analysis to synthesis, applying engineering principles such as standardization, decoupling, and abstraction to biological systems [15]. The field is driven by the vision of programming cellular behavior through designed genetic circuits, creating biological machines with predictable and reliable functions. The foundational concept involves the design of synthetic cells comprising three core elements: an inducer (small molecule, ligand, or light), a genetic circuit (designed DNA construct), and an output signal (reporter gene or phenotypic change) [15].

The synthetic biology market, exceeding USD 11 billion in 2018 with anticipated growth of over 24% CAGR through 2025, reflects the substantial commercial investment in these approaches [18]. Pharmaceutical and diagnostic applications dominate this market, accounting for over 75% market share in 2018, underscoring the significant impact on therapeutic development [18].

Key Technological Approaches

Genetic circuit engineering involves the assembly of standardized biological parts (promoters, coding sequences, terminators) into functional units that process input signals and generate defined outputs [15]. These circuits can implement logical operations (AND, OR, NOT gates), feedback controllers, and oscillators, enabling sophisticated processing of biological information.

Metabolic engineering redirects cellular metabolism toward the production of valuable compounds, including pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and industrial chemicals [15] [18]. Success in this domain culminated with the bioproduction of artemisinin by engineered microorganisms, demonstrating the potential for scalable production of complex natural products [15].

Genome editing and synthesis technologies have revolutionized our ability to manipulate biological systems, with plummeting DNA synthesis costs and advances in genetic engineering tools accelerating synthetic biology applications [17] [18]. These technologies enable both the editing of endogenous genetic elements and the introduction of entirely synthetic constructs.

The Predict-Explain-Discover Framework for Virtual Cells

A particularly sophisticated application of synthetic biology principles emerges in the development of virtual cells, which aim to simulate the functional response of cells to perturbations [19]. The "Predict-Explain-Discover" (P-E-D) framework establishes key capabilities for these models:

Predict functionality requires accurately forecasting the effects of perturbations on cellular systems across diverse biological contexts, timepoints, and modalities, including gene expression, morphology, protein activity, and other phenotypic changes [19].

Explain capability involves identifying key biomolecular interactions, causal pathways, and context-dependent regulatory mechanisms that underlie predicted responses, enabling generalization beyond training data and reasoning about counterfactuals [19].

Discover functionality utilizes virtual cells as world models for systematic hypothesis generation, testing, and refinement through lab-in-the-loop experimentation, leading to novel biological insights and actionable therapeutic hypotheses [19].

The following diagram illustrates the architecture of this P-E-D framework and its implementation through lab-in-the-loop experimentation:

Diagram 2: Virtual Cell P-E-D Framework (77 characters)

Comparative Analysis: Methodologies and Applications

Cross-Paradigm Methodological Comparison

While systems and synthetic biology originate from different philosophical foundations, their methodologies increasingly converge in practical applications. The following table summarizes key methodological distinctions and overlaps:

Table 3: Methodological Comparison Between Systems and Synthetic Biology

| Methodological Aspect | Systems Biology | Synthetic Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Large-scale omics datasets from natural systems | Defined genetic constructs and characterization data |

| Computational Approaches | Network modeling, machine learning, dynamical systems | Circuit design, optimization, DNA assembly planning |

| Experimental Validation | Measurement of endogenous system perturbations | Characterization of engineered system behavior |

| Success Metrics | Predictive accuracy for natural system behavior | Functionality and reliability of engineered system |

| Therapeutic Output | Identification of intervention points | Implementation of therapeutic functions |

Hybrid Approaches: Machine Learning and Metabolic Modeling

The integration of systems and synthetic biology approaches is particularly evident in emerging hybrid methodologies that combine mechanistic models with machine learning. Hybrid modeling approaches leverage increasing availability of metabolomic and lipidomic data with growing feature coverage to develop predictive models of cell metabolic processes [20]. These models can be trained on longitudinal data for predictive capabilities or on steady-state data for comparative analysis of metabolic states in different environments or disease conditions [20].

The incorporation of metabolic network knowledge enhances model development with limited data, creating powerful predictive tools that combine first-principles understanding with data-driven pattern recognition [20]. This hybrid approach is particularly valuable for optimizing bioproduction in synthetic biology applications, where mechanistic models guide engineering strategies while machine learning extracts complex patterns from high-dimensional characterization data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Implementation of the methodologies described requires specialized reagents, platforms, and technologies. The following table catalogues essential tools for research spanning predictive modeling and cellular programming:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Construction | Synthetic genes, synthetic DNA parts, chassis organisms [18] | Assembly of genetic circuits and pathway engineering |

| Genome Editing | CRISPR-Cas systems, TALENs, zinc finger nucleases [18] | Targeted modification of endogenous genetic elements |

| Omics Technologies | Transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics platforms [14] | Comprehensive molecular profiling for systems models |

| Microfluidics | High-throughput screening systems, organ-on-a-chip platforms [18] [21] | Controlled microenvironment for 3D cell culture and screening |

| Biosensors | Engineered reporters, optogenetic switches [15] | Monitoring pathway activity and controlling cellular functions |

| Computational Platforms | Network modeling software, CAD tools for genetic design [14] [16] | In silico design and simulation of biological systems |

| 4-(Trityloxy)butan-2-ol | 4-(Trityloxy)butan-2-ol, MF:C23H24O2, MW:332.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cyclododecen-1-yl acetate | Cyclododecen-1-yl acetate, CAS:6667-66-9, MF:C14H24O2, MW:224.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mass Action Kinetics Modeling for Drug Combination Prediction

This protocol outlines the development of a mass action kinetics model for predicting synergistic drug combinations, based on methodologies successfully applied to cancer signaling networks [16]:

Step 1: Network Definition and Equation Specification

- Define network topology based on literature mining and curated databases

- Formulate ordinary differential equations (ODEs) for each molecular species

- Specify reaction rate equations using mass action or Michaelis-Menten kinetics

Step 2: Parameter Estimation

- Compile known kinetic parameters from literature and databases

- Use particle swarm optimization or similar algorithms to estimate unknown parameters

- Fit model to experimental time-course data of key signaling nodes

Step 3: Model Validation and Sensitivity Analysis

- Validate model predictions against experimental data not used in parameter estimation

- Perform global sensitivity analysis to identify parameters with greatest impact on outputs

- Assess prediction uncertainty using ensemble modeling approaches

Step 4: Combination Screening and Synergy Quantification

- Simulate single drug responses across concentration ranges

- Predict combination effects using Loewe additivity or Bliss independence models

- Identify synergistic combinations for experimental validation

Step 5: Experimental Validation

- Measure dose-response curves for individual drugs and combinations

- Calculate combination indices using appropriate reference models

- Iteratively refine model based on experimental results

Protocol 2: Genetic Circuit Implementation for Therapeutic Biosensing

This protocol describes the design and implementation of a genetic circuit for therapeutic applications, incorporating design principles from established synthetic biology methodologies [15] [17]:

Step 1: Circuit Design and In Silico Validation

- Define input-output relationship and operational parameters

- Select appropriate biological parts (promoters, RBS, coding sequences, terminators)

- Use computational tools to simulate circuit behavior and identify potential issues

Step 2: DNA Assembly and Parts Characterization

- Assemble genetic circuit using standardized assembly method (Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly)

- Characterize individual parts in isolation to determine transfer functions

- Measure dynamic range, leakiness, and response time of sensing components

Step 3: Circuit Integration and Testing

- Integrate complete circuit into chosen chassis organism

- Measure circuit response to input signals across concentration ranges

- Assess context effects and host-circuit interactions

Step 4: Functional Validation in Relevant Models

- Test circuit function in cell-based models of increasing complexity

- Evaluate specificity, sensitivity, and dynamic range in physiological contexts

- Assess therapeutic efficacy in disease-relevant models

Step 5: Performance Optimization

- Implement design-build-test-learn cycles to improve circuit function

- Use directed evolution or rational design to enhance component performance

- Optimize circuit robustness to environmental and genetic context

Systems biology and synthetic biology represent complementary approaches to understanding and engineering biological systems, with the former focused on predictive modeling of natural systems and the latter on programming novel functions in cellular machines. While their philosophical origins differ, these fields increasingly converge in both methodology and application, particularly as synthetic biology implementations generate rich datasets for systems biology analysis, and systems biology models inform synthetic biology design principles.

This convergence is particularly evident in emerging approaches such as virtual cells, which combine detailed mechanistic understanding with engineering design principles to create predictive models with explanatory power [19]. Similarly, the integration of machine learning with mechanistic models creates hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both data-driven and first-principles methodologies [20].

For drug development professionals and researchers, the strategic integration of both paradigms offers a powerful approach to addressing the persistent challenges of therapeutic development. Systems biology provides the analytical framework for understanding disease complexity and identifying intervention points, while synthetic biology offers the engineering toolkit for implementing sophisticated therapeutic functions. Together, these fields are advancing toward a future where biological systems can be both comprehensively understood and precisely engineered to address pressing human health challenges.

The escalating complexity of biological research demands frameworks that can integrate insights across multiple scales of organization. This whitepaper presents an integrative methodology for examining biological systems across molecular, network, cellular, and societal levels, contextualized within the contrasting yet complementary approaches of systems and synthetic biology. Systems biology focuses on deconstructing and understanding the emergent behaviors of natural biological systems, while synthetic biology employs engineering principles to construct novel biological functions and systems. We provide quantitative comparisons of these approaches, detailed experimental protocols for cross-scale investigation, visualizations of key workflows, and a comprehensive toolkit for researchers. This framework aims to equip scientists and drug development professionals with methodologies to accelerate the translation of basic biological discoveries into therapeutic applications.

Modern biological research grapples with a fundamental challenge: understanding how phenomena at one scale of organization influence and are influenced by other scales. The integration of molecular-level interactions with cellular behaviors, and further with population-level and societal impacts, remains a significant hurdle in fields from microbiology to therapeutic development. This challenge is exemplified in the differing philosophies of systems biology, which seeks to understand the complex, emergent properties of natural biological systems [22], and synthetic biology, which applies engineering principles to design and construct new biological parts, devices, and systems [23].

The need for an integrative framework is particularly pressing given the growing recognition of biotechnology as a potential general-purpose technology that could fundamentally reshape manufacturing, medicine, and sustainability [23]. This whitepaper outlines a structured approach for investigating biological questions across these scales, providing both theoretical context and practical methodological guidance for researchers operating at the intersection of discovery and application.

Quantitative Comparison: Systems Biology vs. Synthetic Biology Approaches

The following tables provide a structured comparison of the core characteristics, methodological approaches, and applications of systems biology and synthetic biology, highlighting their complementary strengths in addressing biological questions across different scales.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics and Philosophical Approaches

| Aspect | Systems Biology | Synthetic Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Understanding emergent properties in natural systems [22] | Designing and constructing novel biological systems [23] |

| Core Philosophy | Analysis, decomposition, and modeling of existing complexity | Synthesis, engineering, and standardization of biological parts |

| Key Question | "How do biological systems function as integrated wholes?" | "How can we build biological systems with desired functions?" |

| Approach to Complexity | Embraces and seeks to understand natural complexity | Aims to simplify and modularize complexity for predictability |

| Model Validation | Agreement with experimental data from natural systems | Performance against design specifications for novel functions |

| Temporal Perspective | Reverse-engineering evolved systems | Forward-engineering new capabilities |

Table 2: Methodologies and Technical Applications

| Aspect | Systems Biology | Synthetic Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Types | Omics data (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [24] | DNA sequences, circuit performance metrics, standardization data |

| Key Modeling Approaches | Quantitative, computational models of system dynamics [25] [22] | Engineering models focusing on input-output relationships |

| Central Techniques | High-throughput measurement, network analysis, computational simulation | DNA assembly, circuit design, host engineering, standardization |

| Host System Considerations | Models host-circuit interdependence as a complex system to understand [25] | Engineers host chassis to minimize unwanted interactions [25] |

| Applications in Sustainability | Analyzing natural systems for bioremediation and conservation [6] | Engineering novel solutions for energy, agriculture, and materials [6] [23] |

| Applications in Medicine | Network-based drug target identification, disease mechanism elucidation | Engineered therapeutics, diagnostic circuits, programmable cells |

Table 3: Cross-Scale Integration Capabilities

| Biological Scale | Systems Biology Approach | Synthetic Biology Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular | Identifies interaction networks and post-translational modifications | Designs synthetic proteins and genetic regulatory elements |

| Network | Models endogenous signaling and metabolic pathways | Implements synthetic gene circuits and logic gates [25] |

| Cellular | Analyzes emergent cellular behaviors from molecular interactions | Engineers novel cellular behaviors and programmed functions |

| Population | Studies tissue-level coordination and microbial ecology | Creates coordinated population-level behaviors (quorum sensing) |

| Societal/Environmental | Assesses ecological impacts and system-level responses | Develops solutions for bioremediation, sustainable production [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Scale Biological Investigation

Protocol 1: Integrative Circuit-Host Modeling Framework

This protocol enables researchers to predict synthetic gene network behaviors by explicitly integrating circuit design with host physiology, addressing a fundamental challenge in synthetic biology where complex interdependencies between circuits and their host often lead to unexpected behaviors [25].

Materials:

- Host organism (e.g., E. coli, yeast, mammalian cells)

- Synthetic gene circuit components (promoters, coding sequences, terminators)

- Molecular biology reagents for circuit assembly and transformation

- Instruments for measuring growth dynamics and gene expression

- Computational resources for modeling

Methodology:

- Circuit Design and Assembly: Design synthetic gene circuits using standardized biological parts. Assemble using appropriate DNA assembly techniques (Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly).

- Host Transformation: Introduce assembled circuits into host organisms using transformation methods appropriate for the host.

- Dynamic Measurement: Measure both circuit performance (reporter expression levels) and host physiology (growth rate, resource allocation) over time.

- Model Training: Train the integrative model using collected experimental data, incorporating:

- Dynamic resource partitioning within the host

- Multilayered circuit-host coupling (both generic and system-specific interactions)

- Detailed kinetics of the exogenous circuits

- Model Validation and Prediction: Test model predictions by comparing simulated behaviors with experimental outcomes for different circuit configurations.

- Iterative Refinement: Use discrepancies between predictions and experimental results to refine model parameters and structure.

This framework has demonstrated utility in examining growth-modulating feedback circuits and revealing toggle switch behaviors across scales from single-cell dynamics to population structure and spatial ecology [25].

Protocol 2: Differentiable Simulation for Biophysical Neural Models

This approach combines biological accuracy with advanced machine-learning optimization, enabling large-scale biophysical neuron model optimization through automatic differentiation and GPU acceleration [22].

Materials:

- Electrophysiological recording equipment

- Neural tissue or cultured neurons

- Computational resources with GPU acceleration

- JAXLEY simulator software [22]

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Record electrophysiological responses from target neurons under various stimulus conditions.

- Model Initialization: Create initial biophysical models incorporating known channel properties and morphological characteristics.

- Gradient-Based Optimization: Use automatic differentiation to efficiently compute gradients of model parameters with respect to error functions.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Systematically explore parameter spaces to identify configurations that best match experimental data.

- Cross-Scale Validation: Validate model predictions at multiple biological scales, from molecular channel dynamics to network-level emergent behaviors.

- Mechanism Exploration: Use optimized models to explore potential mechanisms underlying neural computation at scale.

This methodology uniquely combines biological accuracy with advanced machine-learning optimization techniques, allowing for efficient hyperparameter tuning and the exploration of neural computation mechanisms at scale [22].

Visualizing Cross-Scale Biological Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate key workflows and relationships in integrative biological research across molecular, network, cellular, and societal scales.

Integrative Circuit-Host Modeling Workflow

Figure 1: Integrative circuit-host modeling framework for predicting synthetic gene network behaviors, combining circuit design with host physiology models [25].

Multiscale Analysis from Molecular to Societal Impact

Figure 2: Bidirectional relationships across biological scales, showing how molecular interactions propagate to societal impact while societal priorities influence research directions [6] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Scale Biological Investigation

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function in Research | Application Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Synthesis & Assembly | DNA synthesizers, restriction enzymes, assembly kits | Writing user-specified DNA sequences for circuit construction [23] | Molecular, Network |

| Measurement Tools | UPLC-MS, SPR biosensors, RNA-seq reagents | Quantitative analysis of metabolites, biomolecular interactions, and gene expression [24] | Molecular, Network, Cellular |

| Host Engineering | Transformation reagents, CRISPR-Cas9 systems, shuttle vectors | Introducing and modifying genetic circuits in host organisms | Cellular, Network |

| Modeling Resources | JAXLEY simulator, OmniReg-GPT, stochastic simulation algorithms | Predicting system behaviors and optimizing biological designs [22] [24] | All Scales |

| Standardization Tools | BioLLMs, reference materials, characterized biological parts | Generating biologically significant sequences and ensuring reproducibility [23] | Molecular, Network |

| Distributed Manufacturing | Portable bioreactors, expression strains, defined media | Enabling flexible bioproduction across locations and time [23] | Societal, Population |

| 2-Fluoro-5-phenylpyrimidine | 2-Fluoro-5-phenylpyrimidine, CAS:62850-13-9, MF:C10H7FN2, MW:174.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Difluorostilbene | Difluorostilbene, CAS:643-76-5, MF:C14H10F2, MW:216.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integrative framework presented in this whitepaper provides a structured approach for investigating biological systems across traditional scale boundaries, leveraging the complementary strengths of systems and synthetic biology. As biotechnology continues to evolve toward a general-purpose technology with profound implications for medicine, sustainability, and manufacturing [23], such cross-scale methodologies will become increasingly essential. The quantitative comparisons, experimental protocols, visualizations, and research tools outlined here offer researchers and drug development professionals a foundation for advancing both fundamental understanding and practical applications in biological science. By consciously integrating perspectives from molecular to societal scales, the scientific community can more effectively address complex challenges in human health and environmental sustainability.

From Bench to Bedside: Methodologies and Breakthrough Applications in Biomedicine

Systems biology is an interdisciplinary field that seeks to understand the complex interactions within biological systems through the integration of experimental data, computational modeling, and theoretical frameworks. Unlike synthetic biology, which focuses on designing and constructing new biological parts and systems, systems biology aims to decipher the emergent properties of existing biological networks through holistic analysis. This methodological distinction positions systems biology as primarily analytical and discovery-driven, while synthetic biology is predominantly engineering-oriented. The core mission of systems biology involves mapping biological processes across multiple organizational scales—from molecular interactions to pathway dynamics and ultimately to organism-level phenotypes. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to the essential computational toolbox enabling modern systems biology research, with particular emphasis on multi-omics integration, biological network analysis, and artificial intelligence (AI)-driven modeling approaches that are transforming drug development and basic research.

The foundational principle of systems biology is that biological functionality emerges from complex network interactions rather than isolated molecular components. This perspective requires specialized computational infrastructure to manage, integrate, and interpret heterogeneous biological data. The field has responded by developing standardized data formats, sophisticated visualization platforms, and analytical frameworks capable of handling biological complexity. The convergence of these computational resources with AI technologies represents a paradigm shift in how researchers explore biological systems, enabling more predictive modeling and deeper mechanistic insights than previously possible.

Multi-omics Data Integration Frameworks

Data Standards and Exchange Formats

The integration of diverse omics datasets (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) requires robust data standards that ensure interoperability across platforms and tools. The COmputational Modeling in BIology NEtwork (COMBINE) initiative coordinates the development of community standards and formats for all aspects of computational modeling in biology [26]. These standards are essential for facilitating data exchange, reproducibility, and collaborative research. The table below summarizes the key data formats used in systems biology:

Table 1: Essential Data Formats in Systems Biology

| Format | Full Name | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBML | Systems Biology Markup Language | Mathematical modeling of biological processes | XML-based; supported by >100 tools; enables model simulation [26] |

| BioPAX | Biological Pathway Exchange | Pathway representation and knowledge exchange | RDF/OWL-based; captures molecular interactions; facilitates data sharing [27] |

| SBGN | Systems Biology Graphical Notation | Visual representation of biological networks | Standardized visual language; three complementary languages [26] |

| BNGL | BioNetGen Language | Rule-based modeling of signaling networks | Text-based; concise specification of complex interactions [26] |

| NeuroML | Neural Morphology Language | Definition of neuronal cell and network models | XML-based; describes electrophysiological properties [26] |

| CellML | Cell Modeling Language | Mathematical model representation | Open standard; reusable model components [26] |

AI-Enhanced Multi-omics Integration

Artificial intelligence significantly enhances multi-omics data analysis through advanced algorithms and machine learning techniques that capture complex biological interactions [28]. AI approaches address several critical challenges in multi-omics integration:

Enhanced Data Integration: Machine learning models, particularly deep learning architectures, facilitate the integration of heterogeneous multi-omics datasets, enabling researchers to capture interactions between different biological layers and gain a more comprehensive understanding of biological processes [28]. For instance, AI can combine genomic data with transcriptomic and proteomic data to identify gene regulatory networks and pathways critical in disease states.

Improved Predictive Modeling: Deep learning techniques have demonstrated significant promise in predicting clinical outcomes based on multi-omics data. AI models can predict patient responses to treatments by analyzing patterns across various omics layers, enabling personalized medicine approaches that outperform traditional statistical methods [28].

Discovery of Novel Biomarkers: AI techniques can identify novel biomarkers by analyzing large-scale multi-omics datasets. For example, AI has been used to uncover genetic loci associated with diseases by integrating genomic and phenotypic data, as demonstrated in studies focusing on retinal thickness and its implications for systemic diseases [28].

Handling Missing Data: AI methods, particularly imputation algorithms, effectively address missing data challenges commonly encountered in multi-omics studies. By leveraging patterns in existing data, AI can predict and fill in gaps, enhancing the quality and completeness of analyses [28].

Emerging AI technologies such as Foundation Models (FMs) and Agentic AI are revolutionizing biomedical discovery by enabling more sophisticated analysis of multi-omics data [29]. These models are pre-trained on diverse patient data, including genomics, transcriptomics, and molecular-level data, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interactions between disease mechanisms and individual variability. Agentic AI systems, which are large language model (LLM)-driven systems capable of autonomously planning, reasoning, and dynamically calling tools/functions, are particularly powerful for constructing and executing complex omics workflows without requiring extensive computational expertise [29].

Network Analysis and Visualization

Biological Network Theory and Applications

Biological networks are well-established methodologies for capturing complex associations between biological entities, serving as both resources of biological knowledge for bioinformatics analyses and frameworks for presenting subsequent results [30]. Networks fundamentally represent biological systems as graphs consisting of nodes (biological entities such as proteins, genes, or metabolites) and edges (the interactions or relationships between these entities). The interpretation of biological networks is challenging and requires suitable visualizations dependent on the contained information, which has led to the development of specialized software tools for network analysis and visualization [30].

Biological networks can be categorized based on their biological scope and function:

- Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks: Capture physical interactions between proteins, revealing functional complexes and signaling pathways.

- Metabolic Networks: Represent biochemical reaction pathways and metabolic fluxes within cells.

- Gene Regulatory Networks: Depict transcriptional regulation relationships between transcription factors and target genes.

- Signal Transduction Networks: Illustrate signaling cascades and pathways from cell surface receptors to intracellular effectors.

The information associated with individual nodes or edges in biological networks often extends far beyond basic names and types, including quantitative parameters, experimental evidence, cellular compartments, and functional annotations. This information-rich data provides opportunities for comprehensive visualization but requires powerful tools to effectively represent and analyze [30].

Visualization Tools and Platforms

Cytoscape is the most prominent desktop software for biological network analysis and visualization, supporting large networks with a rich set of features [30]. It employs a data-dependent visualization strategy through "attribute-to-visual-mappings," where a node's or edge's attribute translates to its visual representation, enabling researchers to encode additional information in visual properties like color, size, shape, and line width. However, Cytoscape presents some challenges, including installation requirements and a steep learning curve for quick results [30].

NDExEdit represents a web-based alternative for data-dependent visualization of biological networks within the browser, requiring no installation [30]. This web application provides a lightweight interface to explore network contents and facilitates quick definition of custom visualizations dependent on data. Key features include:

- Import Flexibility: Networks can be loaded from the NDEx platform using UUIDs or URLs, or from local CX files

- Visual Mapping: Implementation of data-dependent visual properties through stylesheets

- Layout Algorithms: Multiple built-in algorithms for node positioning with manual refinement capabilities

- Export Options: Save as CX file or standard image formats (PNG, JPEG)

- Data Privacy: Network data is stored locally within the web browser

NDExEdit complies with the Cytoscape Exchange (CX) data structure, a JSON-based format designed for transmitting biological networks between web applications and servers [30]. The CX format organizes different types of network information into modular aspects, separating basic network structure from additional information and visual representation, which reduces data transfer requirements while maintaining coherence.

Table 2: Network Visualization Tools Comparison

| Tool | Platform | Primary Strength | Data Format | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape | Desktop | Comprehensive analysis and visualization features | CX, SIF, GraphML | Installation required; steep learning curve [30] |

| NDExEdit | Web-based | Quick visual adjustments; no installation | CX | Accessible through browsers; minimal learning curve [30] |

| NDEx Platform | Web-based | Network sharing and collaboration | CX | Requires account for private networks [30] |

| ChiBE | Desktop | BioPAX visualization and editing | BioPAX | Specialized for pathway editing [27] |

| BiNoM | Desktop plugin | Network analysis with import/export | BioPAX Level 3 | Extends Cytoscape functionality [27] |

Effective Visualization Principles

Effective colorization of biological data visualization requires careful consideration to ensure visual representations do not overwhelm, obscure, or bias the findings but rather enhance understandability [31]. The following rules provide guidance for colorizing biological data visualizations:

- Identify Data Nature: Recognize whether data is qualitative (nominal, ordinal) or quantitative (interval, ratio) to inform color scheme selection [31].

- Select Appropriate Color Space: Use perceptually uniform color spaces (CIE Luv, CIE Lab) that align with human vision perception rather than device-dependent spaces (RGB, CMYK) [31].

- Create Suitable Color Palettes: Develop palettes based on the selected color space and data characteristics [31].