Synthetic Biology Circuits: Design Principles, Methodologies, and Clinical Translation for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the fundamentals of synthetic gene circuits.

Synthetic Biology Circuits: Design Principles, Methodologies, and Clinical Translation for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the fundamentals of synthetic gene circuits. It explores the core design principles of biological circuits, from individual regulatory devices to complex network topologies. The content details advanced methodologies for circuit construction, including standardization tools and combinatorial optimization strategies, and addresses critical challenges in predictability and host-circuit interactions. Furthermore, it examines rigorous validation frameworks and benchmarking techniques essential for clinical translation. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with current applications in stem cell engineering and therapeutic design, this review serves as a guide for leveraging synthetic biology to create next-generation biomedical solutions.

Core Principles and Components of Synthetic Gene Circuits

Defining Genetic Circuits and Their Role in Understanding Natural Biology

Synthetic biology represents a fundamental shift in genetic engineering, moving from manipulation of individual genes to the bottom-up construction and analysis of interconnected gene networks [1]. Genetic circuits are an application of this approach, defined as assemblies of biological parts inside a cell that are designed to perform logical functions, mimicking operations observed in electronic circuits [2]. These circuits are typically categorized as genetic (transcriptional), RNA, or protein circuits, depending on the types of biomolecules that interact to create the circuit's behavior [2].

The core premise of using synthetic genetic circuits to understand natural biology is that by constructing simplified, well-defined systems from characterized components, researchers can test fundamental principles of cellular regulation, network architecture, and evolutionary design [1]. This methodology complements traditional top-down biological approaches by enabling direct manipulation of circuit parameters and architectures that may be difficult or impossible to isolate in complex endogenous systems.

Historical Foundations and Key Circuit Archetypes

The conceptual foundation for genetic circuits was established through the study of natural regulatory systems, most notably the lac operon in E. coli, which Jacques Monod and Francois Jacob discovered functions as a metabolic switch controlled by a two-part mechanism [2]. The field of synthetic biology proper began with the construction of the first engineered genetic circuits in 2000: a genetic toggle switch and a repressilator [2] [3].

The toggle switch, developed by Gardner, Cantor, and Collins, demonstrated bistability—the ability to switch between two stable states in response to transient stimuli [2]. The design utilized two mutually repressive genes, where each promoter is inhibited by the repressor transcribed by the opposing promoter [2]. The repressilator, created by Elowitz and Leibler, connected three repressor genes in a cyclic negative feedback loop to generate self-sustaining oscillations in protein levels [2] [3]. These pioneering circuits established that engineering principles could be applied to biological systems to create predictable, complex behaviors.

Table 1: Foundational Genetic Circuits in Synthetic Biology

| Circuit Name | Year | Key Components | Function | Biological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Toggle Switch | 2000 | Two mutually repressive genes (e.g., LacI, TetR) [1] | Bistable switching between two stable states [2] | Demonstrates how transient signals can create persistent cellular states [2] |

| Repressilator | 2000 | Three repressor genes in cyclic inhibition (TetR, LacI, λ CI) [4] | Generating sustained oscillations in protein levels [2] | Shows how simple regulatory motifs can create biological rhythms [2] |

| Synthetic Oscillator | 2011 | Activator and repressor with coupled degradation [1] | Self-sustained, tunable oscillations [1] | Revealed importance of time delays and host interactions for robust function [1] |

Quantitative Analysis of Circuit Performance and Stability

A significant challenge in genetic circuit engineering is evolutionary stability—the maintenance of circuit function over multiple generations. Circuit expression imposes a metabolic burden on host cells by diverting resources like ribosomes and amino acids, reducing growth rates and creating selective pressure for loss-of-function mutations [5]. The evolutionary longevity of circuits can be quantified using specific metrics shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Metrics for Quantifying Evolutionary Longevity of Genetic Circuits

| Metric | Definition | Significance | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| P₀ | Initial circuit output prior to mutation [5] | Measures maximal functional performance | Varies by circuit design |

| τ±10 | Time for output to fall outside P₀ ± 10% [5] | Indicates short-term functional stability | Highly dependent on burden [5] |

| τ₅₀ | Time for output to fall below P₀/2 [5] | Measures long-term functional persistence | 3-fold variation across designs [5] |

Recent research has focused on developing genetic controllers that enhance evolutionary longevity. Computational modeling reveals that controller architecture significantly impacts stability: post-transcriptional controllers using small RNAs generally outperform transcriptional controllers, and growth-based feedback extends functional half-life more effectively than intra-circuit feedback [5]. Multi-input controllers that combine these approaches can improve circuit half-life over threefold without coupling to essential genes [5].

Methodologies for Circuit Design and Implementation

Regulatory Mechanisms for Circuit Construction

Genetic circuits operate by controlling the flow of RNA polymerase (RNAP) on DNA using various regulatory mechanisms [6]:

DNA-binding proteins: Repressors (e.g., TetR, LacI homologues) block RNAP binding or progression, while activators recruit RNAP to promoters [6]. Recent efforts have expanded available orthogonal repressors and activators to enable more complex circuits [6].

Invertases: Site-specific recombinases (e.g., Cre, Flp, serine integrases) that flip DNA segments between binding sites, permanently changing circuit state [6]. These are ideal for memory storage applications but operate slowly (2-6 hours) [6].

CRISPRi/a: Catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused to regulatory domains can repress (CRISPRi) or activate (CRISPRa) transcription when guided by specific RNA sequences [6] [3]. This system offers high designability through programmable guide RNAs [6].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Genetic Toggle Switch

The following methodology outlines construction and validation of a classic genetic toggle switch based on the design by Gardner et al. [2]:

Plasmid Design: Clone two mutually repressive genes (e.g., lacI and tetR) onto a plasmid, with each gene under the control of a promoter that is inhibited by the other gene's protein product [2]. Include inducible promoters (e.g., Ptrc-1 for IPTG induction) for external control [2].

Reporter Integration: Incorporate a reporter gene (e.g., green fluorescent protein, GFP) downstream of one repressor gene to enable quantitative monitoring of circuit state [2].

Transformation and Culturing: Transform the constructed plasmid into E. coli and culture in appropriate medium. Maintain selective pressure with antibiotics corresponding to plasmid markers [2].

Circuit Induction: Add chemical inducers (e.g., IPTG for LacI repression, aTc for TetR repression) at varying concentrations to switch between stable states [2].

Validation and Characterization:

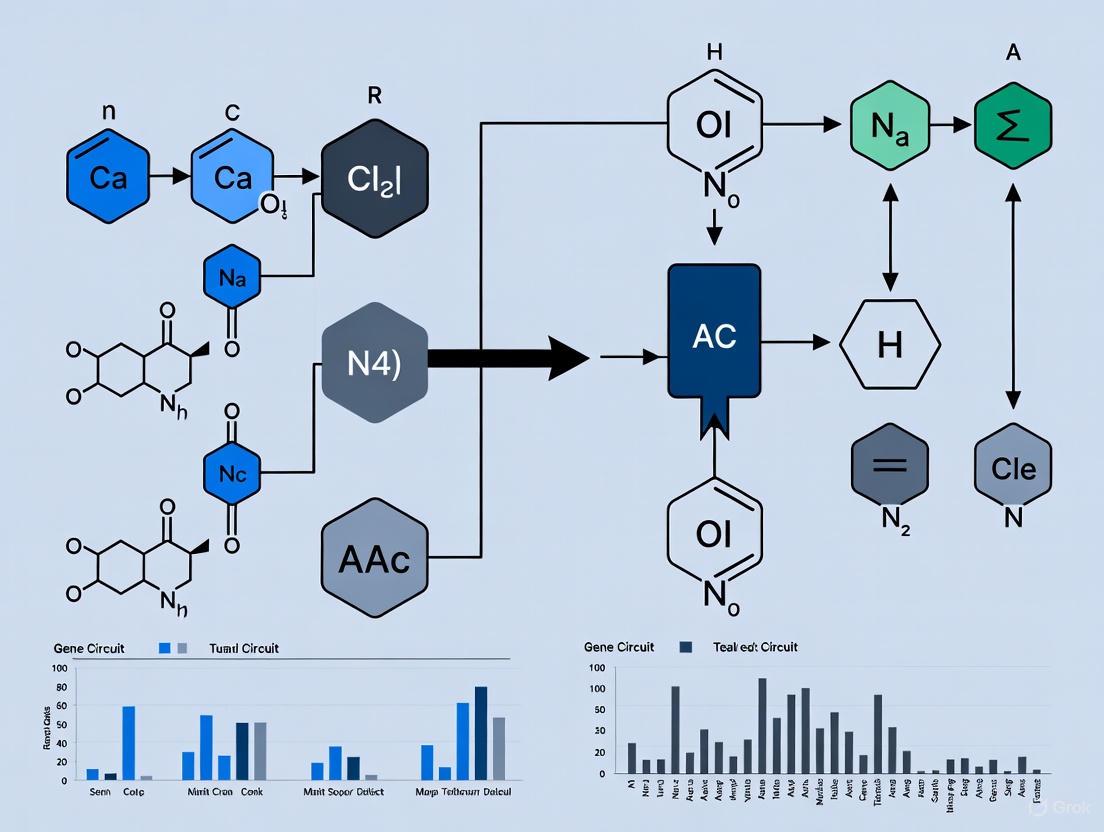

Diagram 1: Genetic toggle switch mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Genetic Circuit Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Example Components | Function in Circuit Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Proteins | TetR, LacI, λ CI homologues [6], Zinc Finger Proteins (ZFPs) [6], TALEs [6] | Transcriptional repressors/activators that control RNAP flux to implement logic operations [6] |

| CRISPR Systems | dCas9, guide RNA scaffolds [6] [3] | Programmable repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) of target genes [6] |

| Invertases/Recombinases | Cre, Flp, serine integrases [6] | Implement permanent genetic memory by flipping DNA segments between orientations [6] |

| Standard Biological Parts | Promoters (Ptac, PLux), RBS libraries, terminators [7] | Modular components for circuit construction with predictable functions [7] |

| Model Organisms | Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis [1], Saccharomyces cerevisiae [7] | Engineering chassis with well-characterized genetics and regulatory systems [1] [7] |

Advanced Applications: Circuit Integration with Endogenous Systems

Early synthetic biology aimed to create circuits that functioned autonomously from host cellular processes. However, a new generation of experiments demonstrates that tighter integration between synthetic circuits and endogenous cellular systems provides fundamental biological insights and enhances circuit performance [1]. This approach has revealed that unintended interactions with host components can sometimes improve circuit function, as demonstrated when proteolytic machinery saturation created beneficial coupling between synthetic oscillator components [1].

Rewiring endogenous circuits provides particularly powerful insights into natural biological design principles. For example, rewiring the competence circuit in B. subtilis to an alternative feedback architecture demonstrated why the inherently more variable natural design may be evolutionarily favored—it allows functional variability in competence duration that benefits the population under different environmental conditions [1]. Similarly, rewiring signaling pathways has elucidated specificity determinants and enabled reprogramming of signaling dynamics [1].

Diagram 2: Rewiring endogenous genetic circuits.

Emerging Frontiers and Computational Tools

The field is advancing toward fully automated genetic design workflows where researchers specify desired functions and computational tools automatically identify parts, construct designs, and evaluate alternatives [7]. Genetic Design Automation (GDA) tools like Cello enable automated design of genetic circuits from truth tables or Boolean logic specifications [7]. However, challenges remain in part characterization, standardization, and software tool development before this vision is fully realized [7].

Recent research addresses the critical challenge of evolutionary longevity through "host-aware" computational frameworks that model interactions between host and circuit expression, mutation, and mutant competition [5]. These models enable evaluation of controller architectures that maintain synthetic gene expression despite evolutionary pressures, with multi-input controllers showing particular promise for extending functional half-life [5]. As these tools mature, they will enable more robust, predictable, and stable genetic circuits for both basic research and applied biotechnology.

Genetic circuits serve as both engineering tools for biotechnology and experimental platforms for investigating fundamental biological principles. The synthetic biology approach of constructing simplified, well-defined systems from characterized components has yielded insights into network architectures, dynamics, and evolutionary constraints that would be difficult to obtain through observation alone. As the field advances toward more sophisticated integration with endogenous systems and computational design automation, genetic circuits will continue to play a central role in deciphering the logic of life and engineering biological systems for therapeutic and industrial applications.

This technical guide delineates the hierarchical structure of biological organization, from atomic-scale interactions to complex cellular networks, establishing the fundamental framework upon which synthetic biology circuits are engineered. For researchers and drug development professionals, a precise understanding of these layers is not merely academic but a prerequisite for the rational design of biological systems. By mapping core biological principles to the tools of synthetic biology—including standardized genetic parts, computational modeling, and experimental validation—this review provides a foundational resource for advancing therapeutic development and basic research. The integration of quantitative data tables, detailed protocols, and computational visualizations offers a practical roadmap for interrogating and reprogramming biological networks.

Synthetic biology operates on the core premise that biological systems can be decomposed into a hierarchy of discrete, functional components. This decomposition is analogous to the organization of computer hardware and software, enabling an engineering-based approach to biological design. The hierarchy begins with simple, fundamental biomolecules and ascends through increasing levels of complexity to the intricate regulatory networks that govern cell fate and function. A rigorous understanding of this hierarchy is the first principle for researchers aiming to construct predictive models and implement novel genetic circuits that reliably function within living cells, particularly for high-stakes applications in stem cell engineering and regenerative medicine [8]. This guide details each level of this organization, explicitly connecting it to the methodologies used to model, perturb, and control biological systems for scientific and therapeutic ends.

The Hierarchical Levels of Biological Organization

Biological organization is a foundational concept in biology, describing a classification system for biological structures, ranging from the simplest at the sub-atomic level to the most complex at the biosphere level [9]. Each level represents an increase in organizational complexity, with new properties emerging at each successive stage. The following sections detail these levels, with a focus on the scales most relevant to synthetic biology and circuit design.

Molecular and Biomolecular Level

The most fundamental levels of biological organization include atoms, molecules, and biomolecules. Atoms are the smallest unit of ordinary matter, consisting of a nucleus and electrons. Molecules are formed when two or more atoms are held together by chemical bonds, such as covalent or ionic bonds [9].

Biomolecules are the molecules essential for life, including proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates. These are often polymers—large molecules constructed from smaller, repeating units known as monomers. For instance:

- Proteins are polymers of amino acids.

- Nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) are polymers of nucleotides [9].

These biomolecules can be endogenous (produced within a living organism) or exogenous (obtained from the external environment) [9]. For synthetic biology, nucleic acids are the primary substrate for engineering, serving as the code for both functional proteins and regulatory elements.

Organelle and Cellular Level

The next hierarchical level is comprised of organelles. Organelles are subcellular structures, or compartments, built from biomolecules that perform specialized functions within eukaryotic cells. Examples include:

- Lysosome: Allows for the degradation of molecules without detrimental effects on other cellular structures.

- Chloroplasts: Enable plants to perform photosynthesis.

- Mitochondria: Generate energy for the cell [9].

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of life [9]. Organisms can be unicellular (consisting of a single cell) or multicellular. It is estimated that the human body consists of approximately 37 trillion cells [9]. In synthetic biology, the cell is often referred to as the "chassis," the foundational platform into which genetic circuits are introduced and must operate.

Tissue, Organ, and Organ System Level

In complex multicellular organisms, cells form higher-order structures:

- Tissues: Groups of cells that have similar structures and functions (e.g., connective tissue in animals) [9].

- Organs: Groups of tissues that carry out a specific function or set of functions (e.g., the heart, which pumps blood) [9].

- Organ Systems: Groups of organs that work together to carry out vital processes (e.g., the cardiovascular system, comprised of the heart, vessels, and blood) [9].

A key challenge in synthetic biology is engineering cellular behaviors so that they integrate correctly into these higher-order structures, a critical consideration for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Population, Community, and Ecosystem Level

Beyond the individual organism, the hierarchy expands to encompass:

- Populations: Several organisms of the same species existing at the same place and time [9].

- Communities: Composed of individuals of different species at the same location and time [9].

- Ecosystems: Comprised of the living (biotic) community and the non-living (abiotic) environmental factors that influence it [9].

The highest level is the biosphere, which encompasses all areas on Earth that harbor living organisms [9]. While microbial synthetic ecology is an emerging field, most synthetic biology circuits are designed to function within the context of a single cell or organism.

The Synthetic Biology Framework for Network Analysis and Design

Synthetic biology (SynBio) is an interdisciplinary field that applies engineering principles to biological systems, aiming to redesign or create novel biological components, devices, and systems [8]. Its integration with the hierarchy of biological organization is the cornerstone of modern genetic circuit research.

Core Concepts and the Engineering Cycle

SynBio is characterized by several key concepts:

- Standardization: The use of characterized, interchangeable biological parts with predictable performance. A prime example is the BioBrick system, which uses standardized prefix and suffix restriction sites (EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, PstI) to facilitate the modular assembly of genetic parts like promoters, ribosomal binding sites (RBS), coding sequences (CDS), and terminators [8].

- Abstraction Hierarchy: A framework that allows engineers to work at one level of complexity without needing to manage all the details of the levels below it (e.g., Parts -> Devices -> Systems) [10] [8].

- Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle: An iterative engineering process used to optimize genetic circuits. The cycle begins with computational design, proceeds to physical construction (e.g., via DNA synthesis), involves experimental testing, and concludes with data analysis to inform the next design iteration [8].

Computational Modeling of Biological Networks

Quantitative modeling is indispensable for predicting the behavior of both natural and synthetic biological networks before experimental implementation. A "bottom-up" approach is often employed, where ordinary differential equations (ODEs) are constructed to model the core interactions of a pathway of interest [10].

Table 1: Fundamental Biochemical Processes for Computational Modeling

| Process | Diagram | Rate Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Binding | X + Y → XY | kb[X][Y] |

| Unbinding | XY → X + Y | ku[XY] |

| Production (constant) | → X | kpX |

| Degradation | X → ∅ | kdX[X] |

| Enzyme Catalysis | E + S → E + P | kcat[E][S] / (KM + [S]) |

| Passive Transport | XA XB | kT([XB] - [XA]) |

| Dilution due to growth | X → | kdil[X] |

Source: Adapted from [10]. k terms represent rate constants, and bracketed terms represent concentrations.

The process of model-building involves:

- Identifying Parts and Processes: Defining all relevant biochemical species and the reactions that change their concentrations [10].

- Translating to ODEs: For each part, a differential equation is written:

d[part]/dt = Σ process rates[10]. - Parameter Estimation: Finding realistic values for rate constants, ideally from direct biochemical measurements or by fitting the model to experimental data [10].

- Numerical Solution and Validation: Using computing packages (e.g., MATLAB, Mathematica, or specialized tools like PySB [10]) to solve the ODEs and assessing how well the model matches experimental observations.

Experimental Protocols for Circuit Design and Implementation

The following protocols outline a standard workflow for designing, building, and testing a synthetic gene circuit to probe a natural biological network, such as a signaling pathway.

Protocol 1: In Silico Circuit Design and Model Perturbation

This protocol details the computational phase of synthetic biology research [10].

1. Define the Natural Circuit of Interest:

- Select a signaling or metabolic pathway for analysis (e.g., the p53 tumor-suppressor pathway).

- Conduct a literature review to identify the key molecular components (proteins, genes, small molecules), their interactions (activation, inhibition, binding), and the network topology.

2. Construct a Computational Model:

- Using the information from Step 1, diagram the core network using conventional notation (e.g., process diagrams from Table 1).

- Translate the diagram into a system of ODEs, using the rate equations from Table 1 as a guide.

- Input the equations and initial estimated parameters into an ODE solver (e.g., in MATLAB or Python).

3. Design Informative Synthetic Perturbations In Silico:

- Use the model to simulate classic perturbations (e.g., gene knockouts, achieved by setting the production rate of a component to zero).

- Design more complex synthetic perturbations to probe regulatory connections:

- Bypass an existing connection: Model the effect of constitutively activating a downstream component independent of its natural upstream regulator.

- Introduce novel feedback: Add a synthetic link where the output of the pathway represses or activates an early component.

- Run simulations to predict the system's output (e.g., protein concentration dynamics, steady-state levels) for each perturbation.

4. Analyze Model Predictions:

- Identify which perturbations are predicted to generate a desired novel output or most effectively reveal the underlying network logic.

- Select the most informative predicted perturbations for experimental testing.

Protocol 2: Molecular Implementation and Testing in a Stem Cell Model

This protocol describes the experimental construction and validation of a genetic circuit in a biologically relevant chassis, such as a stem cell [8].

1. Circuit Construction using Standardized Parts:

- Design the DNA sequence for the synthetic circuit, assembling BioBrick-compatible parts from registries (e.g., promoter, RBS, coding sequence for a transcription factor, terminator).

- For a programmable differentiation circuit, the coding sequence may be for a key lineage-specific transcription factor.

- For safety, incorporate an inducible "suicide switch" (e.g., the inducible caspase-9 system) that can trigger apoptosis upon administration of a small molecule.

- Synthesize the full construct, either via traditional restriction-ligation (using BioBrick standards) or using more modern techniques like Gibson Assembly.

2. Cell Transfection and Selection:

- Culture the target stem cells (e.g., human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells - hiPSCs) under standard conditions.

- Introduce the constructed plasmid into the cells using an appropriate method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection, or lentiviral transduction).

- Select successfully transfected cells using a selective marker (e.g., puromycin resistance) included in the plasmid.

3. Functional Validation of the Circuit:

- Induction: Apply the specific inducer for your circuit (e.g., a small molecule, light pulse) to activate the synthetic program.

- Output Measurement: Quantify circuit function over time.

- For a differentiation circuit: Use flow cytometry to track the expression of lineage-specific surface markers (e.g., CD34 for hematopoietic progenitors) and immunofluorescence microscopy to assess cellular morphology.

- For a suicide switch: Induce apoptosis and measure cell viability using a assay (e.g., MTT) and caspase activity with a fluorescent assay.

- Control Experiments: Always include uninduced controls and untransfected cells to account for background changes and non-specific effects.

4. Data Integration and Model Refinement:

- Compare the experimental data from Step 3 to the computational predictions from Protocol 1.

- If discrepancies exist, refine the model parameters or topology and iterate through the DBTL cycle to improve its predictive power.

Visualization of Biological and Synthetic Networks

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate key relationships and workflows described in this guide. The color palette adheres to the specified guidelines, with explicit text coloring for contrast.

Biological Hierarchy

Synthetic Biology DBTL Cycle

Synthetic Circuit Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Circuit Engineering

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Synthetic DNA (Oligonucleotides) | Building blocks for de novo gene synthesis; allow for codon optimization to enhance heterologous protein expression in the host chassis by aligning with its codon usage bias [8]. |

| Standardized Biological Parts (BioBricks) | Characterized genetic sequences (promoters, RBS, CDS, terminators) with standardized prefix/suffix restriction sites; enable modular, reproducible, and high-throughput assembly of genetic devices [8]. |

| Plasmid Backbones | Vectors for harboring the assembled genetic circuit; typically contain origin of replication and selection markers (e.g., antibiotic resistance) for maintenance in bacterial and target host cells [8]. |

| Restriction Enzymes (EcoRI, XbaI, etc.) | Molecular scissors for BioBrick assembly; cut DNA at specific sequences within the standard prefixes and suffixes to allow for the directional ligation of parts [8]. |

| DNA Ligase | Enzyme that catalyzes the formation of phosphodiester bonds to seal the nicks in the DNA backbone, joining standardized parts together into a single plasmid [8]. |

| Transfection Reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine) | Chemical carriers that form complexes with plasmid DNA to facilitate its entry through the cell membrane of the target chassis (e.g., stem cells) [8]. |

| Inducers (Small Molecules, Light-Sensitive Compounds) | Input signals for synthetic circuits; used to trigger circuit activation (e.g., a small molecule to induce differentiation or activate a suicide switch) [8]. |

| Fluorescent Antibodies & Flow Cytometry Reagents | Critical for measuring circuit output; antibodies against cell surface markers (e.g., CD34) enable quantification of differentiation efficiency, while viability dyes assess suicide switch efficacy [8]. |

The hierarchical organization of biological systems provides the essential scaffold for synthetic biology. By deconstructing complexity into manageable levels—from molecules to networks—researchers can apply engineering principles to design, model, and implement genetic circuits with predictive power. This guide has outlined the core concepts, computational and experimental methodologies, and essential tools required to advance this field. As the integration of synthetic biology with stem cells and therapeutic development progresses, a firm grasp of this hierarchy will be paramount for overcoming challenges such as tumorigenic risk and cellular heterogeneity, ultimately enabling the next generation of precise, programmable cellular therapies.

Sensing and reacting to external and internal stimuli is a fundamental property of all living systems, enabled by molecular regulatory devices that can sense a specific signal and create a corresponding output [11]. In synthetic biology, which is dedicated to engineering life, regulatory systems are frequently lifted from nature and "re-wired" or entirely new synthetic regulatory systems are developed to program cellular behavior rationally [11]. The synthetic biologist's toolbox now boasts a staggering selection of regulatory devices with varied modes of action, operating at different levels of gene regulation [11]. The ability to engineer cellular behavior through these synthetic regulatory systems has enabled numerous applications across biotechnology and medicine, from sustainable bioproduction to therapeutic applications [11].

This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the current state-of-the-art toolkit of regulatory parts for synthetic circuit design, organized by their level of action—transcriptional, translational, and post-translational control. We illustrate their implementation into sophisticated devices and systems through selected examples, experimental protocols, and visualization of key design principles. As the field matures, increasing emphasis is being placed on creating robust and predictable systems through careful characterization of parts, adherence to engineering principles, and computational approaches for automated design [11].

Transcriptional Control Devices

Transcriptional control serves as the foundational layer for genetic regulation in synthetic biology, governing the initial step of gene expression where DNA is transcribed into RNA. These devices primarily function by modulating the accessibility of DNA to RNA polymerase and transcription factors.

CRISPR-Based Synthetic Transcription Systems

CRISPR-based artificial transcription factors (crisprTFs) represent a powerful and programmable platform for transcriptional control. These systems typically employ a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) protein fused to transcriptional activation domains, guided by RNA to specific DNA sequences [12]. The modularity of this system allows for multi-tier gene circuit assembly, enabling precise tunability, versatile modularity, and high scalability [12].

A comprehensive crisprTF platform has been demonstrated to achieve up to 25-fold higher activity than the strong EF1α promoter in mammalian cells [12]. This system enables a wide dynamic range of approximately 74-fold change in reporter signals by manipulating two key parameters: guide RNA (gRNA) sequences and the number of gRNA binding sites in synthetic operators [12]. Optimal gRNA performance is associated with a GC content of approximately 50-60% in the PAM-proximal seed region, with systems utilizing activation domains like VPR (VP64-p65-RTA) showing markedly higher expression levels than VP16 or VP64 alone [12].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of CRISPR-Based Transcriptional Systems

| Component Varied | Range Tested | Effect on Expression | Optimal Value/Design | Host Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gRNA seed GC content | 30-80% | Higher expression at 50-60% GC | ~50-60% GC in seed region | CHO, HEK293T, C2C12, H9c2, hiPSCs |

| Number of gRNA binding sites | 2x-16x | Proportional increase in expression | 16x for maximum expression | CHO, HEK293T, C2C12, H9c2, hiPSCs |

| Activation domain | VP16, VP64, VPR | VPR >> VP16, VP64 | dCas9-VPR | CHO cells |

| Promoter strength (input) | 0.002-6.6 RPU | Sigmoidal response | Tunable based on application | E. coli |

Recombinase-Based DNA Sequence Control

For applications requiring permanent and inheritable genetic changes, devices acting directly on DNA sequence integrity offer distinct advantages. Site-specific recombinases such as tyrosine recombinases (e.g., Cre, Flp) and serine integrases (e.g., Bxb1, PhiC31) enable stable genetic alterations through inversion or excision of DNA segments [11]. These systems are particularly well-suited for implementing stable states such as bistable switches or higher-order memory devices [11].

Gene expression regulation is commonly achieved by inversion of DNA segments, controlling whether a promoter is aligned with the target gene, resulting in distinct stable ON or OFF states [11]. Designed bidirectional switchability can be achieved using pairs of unidirectionally active recombinases catalyzing opposite recombination reactions or using a serine integrase with a cognate excisionase [11]. Through suitable topologies, recombinase-driven inversions have been employed to implement counting circuitry and numerous Boolean logic gates [11].

Experimental Protocol: Programmable crisprTF Transcriptional Control

Objective: To implement and characterize a CRISPR-based synthetic transcription system for programmable gene expression in mammalian cells.

Materials:

- Tier 1 entry vectors encoding crisprTFs, gRNAs, operators

- dCas9-VPR expression vector

- Reporter construct (e.g., mKate, YFP)

- Mammalian cell lines (CHO, HEK293T, or specialized lines)

- Transfection reagent

- Flow cytometer for quantification

Procedure:

- Design and Assembly: Select gRNAs with 50-60% GC content in seed region. Clone synthetic operators with 2x-16x gRNA binding sites upstream of minimal promoter driving reporter gene.

- Transient Transfection: Co-transfect dCas9-VPR, gRNA, and reporter constructs into mammalian cells at 70-80% confluency using appropriate transfection reagent.

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate transfected cells for 48 hours post-transfection. Analyze reporter expression using flow cytometry, measuring fluorescence intensity in single cells.

- Data Processing: Calculate promoter activities in Relative Promoter Units (RPUs) by normalizing to appropriate reference standards. Correlate expression levels with gRNA design and binding site number.

- Validation in Multiple Cell Types: Repeat transfection and analysis in relevant mammalian cell types (mouse C2C12 myoblasts, rat H9c2 cardiac myoblasts, human iPSCs) to assess system portability.

Expected Results: A tunable expression range up to 74-fold, with stronger gRNAs and higher binding site numbers yielding increased expression. System should maintain portability across diverse mammalian cell types with consistent tunability [12].

Translational Control Devices

Translational regulation operates at the level of protein synthesis, providing faster response times than transcriptional control and enabling fine-tuning of gene expression without accumulating mRNA intermediates. Protein-based systems are particularly valuable for synthetic mRNA applications, where transcriptional control is not feasible [13].

RNA-Binding Protein Systems

The most fundamental modules for translational regulation are motif-specific RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that bind to specific sequences in the 5' or 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) of target mRNAs [13]. Microbial RBPs such as bacteriophage MS2 coat protein (MS2CP), PP7 coat protein (PP7CP), archaeal ribosomal protein L7Ae, and the tetracycline-responsive repressor (TetR) are preferred due to their high specificity and orthogonality to mammalian systems [13].

These RBPs can repress translation through multiple mechanisms: by sterically hindering ribosome access when bound to 5' UTRs, or by recruiting mRNA decay-promoting proteins like dead box helicase 6 (DDX6) or the deadenylase CNOT7 when bound to 3' UTRs [13]. The TetR system offers the additional advantage of inducible control through doxycycline addition, which conditionally dissociates the repressor from its target RNA motif [13].

Toehold Switch Tunable Expression System

Toehold switches represent a powerful RNA-based mechanism for translational control that enables dynamic tuning of gene expression after circuit assembly [14]. These systems employ a regulatory motif where two separate promoters control the transcription and translation rates of a target gene, allowing independent adjustment of the system's response function [14].

The core component is a 92 bp DNA sequence encoding a structural region and ribosome binding site (RBS) that folds into a hairpin loop, hampering ribosome accessibility [14]. A separately expressed 65 nt tuner small RNA (sRNA), complementary to the first 30 nt of the toehold switch, unfolds this secondary structure through branch migration, making the RBS accessible to ribosomes [14]. This design enables translation initiation rates to be varied over a 100-fold range, with some toehold switch designs allowing up to 400-fold changes [14].

Table 2: Performance of Translational Regulation Systems

| System Type | Mechanism | Dynamic Range | Induction Ratio | Response Time | Host Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toehold switch | sRNA-mediated RBS exposure | Up to 400-fold | 28-fold (OFF), 4.5-fold (ON) | Faster than transcriptional | E. coli |

| MS2CP-VPg | Cap-independent translation | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Mammalian cells |

| TetR-DDX6 | mRNA decay promotion | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Mammalian cells |

| L7Ae | Steric hindrance | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Mammalian cells |

Experimental Protocol: Toehold Switch-Mediated Tunable Expression

Objective: To implement and characterize a toehold switch-based tunable expression system in E. coli.

Materials:

- Toehold switch variant 20 construct (92 bp)

- Tuner sRNA expression vector (65 nt)

- Reporter gene (YFP) under toehold switch control

- E. coli strain for synthetic biology (e.g., DH10B, MG1655)

- Inducers: aTc (for Ptet input), IPTG (for Ptac tuner)

- Flow cytometer with YFP capabilities

Procedure:

- Strain Construction: Transform E. coli with toehold switch-reporter construct and tuner sRNA plasmid. Include controls without tuner sRNA.

- Culture Conditions: Grow overnight cultures in LB with appropriate antibiotics. Dilute 1:100 into fresh medium and grow to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5).

- Induction: Add varying concentrations of aTc (0-100 ng/mL) to set input levels and IPTG (0-1 mM) to set tuner levels in a matrix format.

- Incubation and Measurement: Induce for 6-8 hours to reach steady state. Measure YFP fluorescence using flow cytometry, collecting at least 10,000 events per sample.

- Data Analysis: Calculate promoter activities in Relative Promoter Units (RPUs). Plot response functions for each tuner level. Calculate fold-change and distribution overlaps between low and high input states.

Expected Results: Sigmoidal increase in YFP fluorescence with increasing input (aTc) at fixed tuner levels. Upward shift of entire response function with increasing tuner (IPTG) concentration, with larger relative increases at lower input promoter activities (28-fold vs. 4.5-fold for low and high inputs, respectively) [14].

Post-Translational Control Devices

Post-translational regulation operates at the protein level, enabling the fastest response times and highly spatially resolved signal processing. These systems can control protein activity, stability, localization, and interactions on timescales of seconds or less, making them ideal for applications requiring rapid responses [15].

Protease-Mediated Control Systems

Protease-based switches offer a powerful method for controlling protein function and localization after translation. The POSH (post-translational switch) system exemplifies this approach by controlling protein secretion through an inducible protease [16]. This system involves a transmembrane domain of a cleavable endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signal fused to a protein of interest, which remains in the ER under resting conditions [16].

The platform depends on a customizable inducer-sensitive protease expressed in two parts, which combine in the presence of an inducer to cleave the ER retention signal [16]. The protein of interest is then released from the ER and undergoes trafficking to the Golgi for secretion [16]. This system has been successfully controlled by chemical inducers, light, and electrostimulation, demonstrating versatility across multiple mammalian cell lines and in vivo applications [16].

Engineered Protein-Protein Interactions and Allosteric Control

Controlled protein-protein interactions (PPIs) form another cornerstone of post-translational regulation. Orthogonal coiled-coil domains engineered to heterodimerize with different affinities have been used to rewire MAP kinase cascades, construct transcriptional logic gates, and engineer cooperation between motor proteins [15]. Computational redesign of protein interfaces has enabled the creation of orthogonal signaling pathways, such as between the GTPase CDC42 and its activator Intersectin, with minimal cross-talk to wild-type components [15].

Light-switchable proteins based on plant phytochrome and LOV (Light-Oxygen-Voltage) domains provide exceptional spatiotemporal control of protein activity in live cells [15]. These optogenetic tools have been used to control an increasing number of post-translational events in real time, enabling precise manipulation of signaling pathways with high temporal and spatial resolution [15].

Table 3: Post-Translational Control Systems and Their Applications

| System Type | Control Mechanism | Input Signals | Response Time | Demonstrated Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POSH protease switch | Inducible cleavage of ER retention signal | Chemical, light, electrostimulation | Faster than transcription | Insulin secretion in diabetes model |

| Orthogonal coiled-coils | Engineered heterodimerization | Chemical induction | Not specified | Rewiring MAPK cascades, logic gates |

| Phytochrome/LOV domains | Light-induced conformational changes | Blue/red light | Seconds | Real-time control of signaling pathways |

| Rapamycin-induced dimerization | Chemical-induced protein interaction | Rapamycin or analogs | Minutes | Inducible control of intracellular processes |

| Computationally designed PPIs | Redesigned protein interfaces | Endogenous signals | Not specified | Orthogonal signaling pathways |

Experimental Protocol: POSH Post-Translational Switch

Objective: To implement and characterize a protease-mediated post-translational switch for controlled protein secretion in mammalian cells.

Materials:

- POSH construct: Transmembrane domain with cleavable ER retention signal fused to protein of interest

- Split-protease components (customizable based on inducer)

- Inducers: chemical (e.g., abscisic acid), light system, or electrostimulation equipment

- Mammalian cell lines (HEK293T, HeLa, HEPG2, COS-7)

- Secretion assay reagents (ELISA kits, Western blot equipment)

- Confocal microscopy for localization studies

Procedure:

- Cell Engineering: Co-transfect POSH construct and split-protease components into mammalian cells. Generate stable cell lines if needed.

- Resting Condition Characterization: Culture engineered cells under resting conditions (no inducer). Confirm intracellular retention of target protein using Western blotting of cell lysates vs. supernatant and visualize ER localization via immunofluorescence.

- Induction Protocol: Apply inducer based on system:

- Chemical: Add abscisic acid (0.1-100 µM)

- Light: Illuminate with appropriate wavelength and intensity

- Electrostimulation: Apply defined electrical field

- Time-Course Analysis: Collect cell lysates and culture supernatant at various time points post-induction (0-24 hours).

- Secretion Quantification: Analyze samples via ELISA or Western blot to quantify protein secretion. Normalize to cell number or constitutive secreted control.

- In Vivo Validation (Optional): Implant engineered cells into rodent model (e.g., type 1 diabetic mice). Administer inducer and monitor blood levels of secreted protein (e.g., insulin) and physiological responses (e.g., blood glucose).

Expected Results: Minimal basal secretion under resting conditions with robust, inducible protein secretion following induction. System should respond within minutes to hours, significantly faster than transcription-based systems. In vivo, induced secretion should produce physiological responses (e.g., prolonged increase in insulin levels and normalization of hyperglycemia in diabetic models) [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Circuit Construction

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Actuators | dCas9-VPR, dCas9-VP64, dCas9-VP16 | Programmable transcription activation | RNA-guided targeting, VPR strongest activator |

| RNA-Binding Proteins | MS2CP, PP7CP, L7Ae, TetR | Translational regulation, mRNA localization | High specificity, orthogonal to host |

| Post-Translational Actuators | Split proteases, engineered proteases | Controlled protein cleavage and secretion | Inducible assembly, fast response times |

| Inducible Systems | aTc-, IPTG-, light-, electrostimulation-responsive components | External control of circuit activity | High dynamic range, minimal basal activity |

| Synthetic Biology Parts | Toehold switches, synthetic promoters, orthogonal sRNAs | Circuit implementation and tuning | Modular, characterized, orthogonal |

| Reporting Systems | Fluorescent proteins (YFP, mKate, GFP), luciferases | Circuit output quantification | Bright, stable, compatible with host |

The comprehensive toolbox of regulatory devices for transcriptional, translational, and post-translational control has dramatically expanded the capabilities of synthetic biology. Each control level offers distinct advantages: transcriptional control for stable, inheritable changes; translational control for rapid, tunable responses; and post-translational control for the fastest, spatially precise regulation. The integration of these different regulatory modalities enables the construction of increasingly sophisticated genetic circuits capable of complex information processing and decision-making in living cells.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on enhancing the orthogonality, predictability, and evolutionary stability of these systems. Recent work on genetic controllers that enhance the evolutionary longevity of synthetic gene circuits represents an important step forward, with post-transcriptional controllers generally outperforming transcriptional ones for long-term circuit maintenance [5]. As synthetic biology moves toward more therapeutic and biotechnological applications, the development of regulatory devices that maintain functionality across diverse environments and over extended timescales will be essential for realizing the full potential of this field.

Synthetic biology aims to program living cells with predictable and controllable behaviors, much like engineers program computers. This discipline is founded on the construction of genetic circuits—sets of interacting molecular components that sense, compute, and actuate responses within a cell [17]. These circuits are the fundamental building blocks for re-engineering organisms, enabling applications ranging from sustainable bioproduction and living therapeutics to advanced diagnostic systems [11] [18] [19].

The inaugural synthetic genetic circuits, the genetic toggle switch and the repressilator, demonstrated that core electronics-inspired concepts such as memory storage and timekeeping could be implemented in living systems [18]. Since then, the field has matured, generating an extensive suite of genetic devices, including pulse generators, digital logic gates, filters, and communication modules [18] [6]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the fundamental topologies of these circuits—switches, oscillators, logic gates, and memory devices—framed within the context of contemporary synthetic biology research. We will explore their design principles, operational characteristics, and experimental implementation, providing a foundation for researchers and scientists to understand and apply these tools in biotechnology and drug development.

Fundamental Circuit Topologies

Switches (Bistable Systems)

Function and Principle: A genetic toggle switch is a bistable network that can flip between two stable gene expression states and maintain that state indefinitely, even after the initial stimulus is removed. This functionality provides synthetic systems with a form of cellular memory, which is crucial for processes like cell fate determination and decision-making [18] [5].

The classic design, as established by Gardner et al. (2000), consists of two repressors that mutually inhibit each other's expression [18] [6]. The system is engineered such that a transient chemical or environmental signal can push the system from one stable state (e.g., Repressor A high, Repressor B low) to the other (Repressor A low, Repressor B high).

Table 1: Characteristic performance metrics of synthetic genetic switches.

| Circuit Characteristic | Typical Performance/Value | Biological Components |

|---|---|---|

| Switching Time | Minutes to hours | Repressor proteins (e.g., LacI, TetR), their promoters, and inducers (e.g., IPTG, aTc) |

| Stability | Stable for many cell generations | Promoters with strong mutual repression |

| Induction Threshold | Tunable via promoter engineering | [6] [5] |

Experimental Protocol:

- Circuit Construction: Clone two constitutive promoters, each driving the expression of a repressor protein for the other's promoter, onto a plasmid. Common repressor pairs include LacI-TetR or CI-LacI [6].

- Host Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into a microbial host, typically E. coli.

- Switching Induction: Grow separate cultures of the engineered strain. To each culture, add a transient pulse of an inducer molecule (e.g., IPTG to inactivate LacI, or aTc to inactivate TetR).

- Output Measurement: Monitor the output state over time using fluorescent reporters (e.g., GFP, RFP) placed under the control of the respective promoters. Flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy can be used to quantify the population's shift from one fluorescent state to the other at a single-cell level.

- Stability Verification: After induction, passage the cells in the absence of the inducer and measure the fluorescence to confirm the state is maintained over multiple generations.

Diagram: Genetic Toggle Switch. Two promoters drive expression of repressors that mutually inhibit each other, creating two stable output states.

Oscillators

Function and Principle: Genetic oscillators generate periodic, rhythmic pulses of gene expression. They are fundamental for engineering biological clocks, implementing time-based processes in bioproduction, and studying circadian rhythms [18] [19].

The repressilator, a landmark three-node oscillator, is built from a ring of three repressors, where each repressor inhibits the next in the cycle [18]. This architecture creates a delayed negative feedback loop, which is a core principle for generating oscillations. The expression of each repressor protein cycles out of phase with the others, resulting in sustained oscillations under appropriate conditions.

Table 2: Characteristic performance metrics of synthetic genetic oscillators.

| Circuit Characteristic | Typical Performance/Value | Biological Components |

|---|---|---|

| Period | Hours (e.g., 2-3 hours in E. coli) | Repressor proteins (e.g., LacI, TetR, CI), their promoters, and fluorescent reporters. |

| Amplitude | Varies with design and tuning | [18] [19] |

| Damping | Can be designed to be sustained or damped | [18] [19] |

Experimental Protocol:

- Circuit Construction: Assemble a plasmid where Gene A encodes a repressor for Gene B's promoter, Gene B encodes a repressor for Gene C's promoter, and Gene C encodes a repressor for Gene A's promoter.

- Host Transformation: Introduce the plasmid into E. coli.

- Time-Lapse Monitoring: Culture the engineered cells and monitor the fluorescence of reporters for each gene node over time using automated time-lapse microscopy or plate readers.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the fluorescence time-series data to determine the period, amplitude, and phase relationships of the oscillations. The robustness of oscillations is highly sensitive to production and degradation rates, often requiring careful tuning of promoter strengths and degradation tags.

Diagram: Repressilator Topology. A three-gene ring network where each repressor inhibits the next, creating oscillatory behavior.

Logic Gates

Function and Principle: Genetic logic gates perform Boolean operations on one or more input signals to produce a specific output. They enable cells to make combinatorial decisions, such as responding to a specific combination of environmental cues, which is invaluable for advanced biosensing and targeted therapeutics [18] [19] [20].

Gates can be implemented using various mechanisms. Transcriptional logic often uses DNA-binding proteins (e.g., repressors, activators) where inputs are inducer molecules and the output is a reporter protein [6]. For example, an AND gate may require two different activators to be present for transcription to occur. Alternatively, recombinase-based logic uses enzyme-driven DNA recombination to permanently alter circuit configuration, often integrating logic with long-term memory [11] [20]. For instance, a two-input AND gate can be built so that two recombinases must be present to invert DNA segments and activate a output gene [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Gate Design & Construction: For a transcriptional AND gate, clone a promoter that requires two different activator proteins (or is repressed by two different repressors) to drive a reporter gene. For a recombinase-based AND gate, clone a construct where a reporter gene is separated from its promoter by two transcription terminators, each flanked by recognition sites for a different orthogonal recombinase.

- Input Application: Transform the gate into E. coli and expose cells to different combinations of the input signals (e.g., Inducer A only, Inducer B only, both inducers, or none).

- Output Quantification: Measure the output (e.g., GFP fluorescence) for each input condition after several hours using a flow cytometer or plate reader. The output level for each condition should match the truth table of the intended logic gate.

Diagram: Recombinase-Based AND Gate. The output gene is expressed only if both integrases are present to invert their respective terminators.

Memory Devices

Function and Principle: Synthetic memory devices allow a cell to permanently record exposure to a transient biological or environmental signal. This is a powerful capability for environmental monitoring, disease diagnostics, and studying cellular history [11] [19] [20].

The most common strategy utilizes site-specific recombinases (e.g., serine integrases like Bxb1 and phiC31) that catalyze an irreversible inversion or excision of a DNA segment flanked by their specific target sites (e.g., attB and attP) [11] [20]. This DNA rearrangement can permanently turn a gene on or off, creating a stable, heritable memory that is passed to daughter cells. More recent approaches also use CRISPR-based systems to make sequential edits to a DNA recording array [11].

Table 3: Characteristic performance metrics of synthetic genetic memory devices.

| Circuit Characteristic | Typical Performance/Value | Biological Components |

|---|---|---|

| Writing Time | 2-6 hours | Serine integrases (e.g., Bxb1, phiC31), their attB/attP recognition sites, and inducible promoters. |

| Stability | Long-term (e.g., >90 generations) | [20] |

| Memory Readout | Fluorescence, antibiotic resistance | Fluorescent proteins, antibiotic resistance genes. |

Experimental Protocol:

- Memory Construction: Clone a plasmid where a promoter drives a reporter gene (e.g., GFP), but the promoter or the gene is in an inverted orientation relative to the other, preventing expression. This inverted segment is flanked by recombinase recognition sites (e.g., attB and attP).

- Signal Exposure: Transform the plasmid into cells along with a second, inducible plasmid that expresses the corresponding recombinase (e.g., Bxb1 under control of an arabinose-inducible promoter). Grow cultures and expose one to a pulse of the inducer (e.g., arabinose) while keeping another as an uninduced control.

- Memory Readout: After removing the inducer, continue to grow the cells for many generations. Periodically sample the cells and analyze them by flow cytometry or plating on selective media. The induced culture should show a permanent, heritable shift to the ON state (fluorescent or resistant), while the control culture should remain OFF.

Diagram: Recombinase Memory Device. A transient input signal induces a recombinase that flips an inverted DNA segment, permanently activating the output gene.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The design and implementation of genetic circuits rely on a standardized toolkit of biological parts and experimental strategies.

Table 4: Essential research reagents and materials for genetic circuit construction.

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Biological Parts | Modular DNA sequences that encode specific functions, enabling predictable circuit assembly. | Promoters, RBSs, coding sequences (CDS), and terminators from the Registry of Standard Biological Parts (e.g., BioBricks). Physical standardization via prefix-suffix restriction sites (e.g., EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, PstI) enables modular cloning [8]. |

| Synthetic Transcription Factors (TFs) | Engineered proteins that bind specific DNA sequences to regulate transcription, providing programmability and orthogonality. | Repressors and anti-repressors with Alternate DNA Recognition (ADR) domains (e.g., TFs responsive to IPTG, D-ribose, cellobiose). Used in platforms like Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) for compressed circuit design [21]. |

| Site-Specific Recombinases | Enzymes that catalyze irreversible DNA recombination at specific target sites, forming the basis of permanent memory devices and complex logic. | Serine integrases (Bxb1, phiC31) and tyrosine recombinases (Cre, Flp). Their activity can be made inducible by light or small molecules via fusion to ligand-binding domains (e.g., estrogen receptor) [11] [20]. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 Systems | A programmable platform for transcriptional regulation (CRISPRi/a) and DNA recording, offering high orthogonality through guide RNA design. | Catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressor/activator domains. Guide RNA libraries allow for targeting many promoters simultaneously, facilitating large-scale circuit construction [11] [6]. |

| Model Chassis Organisms | Well-characterized host cells for prototyping and testing genetic circuits. | Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are the primary model systems due to their fast growth, ease of genetic manipulation, and extensive available toolkits [6] [19]. |

Current Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite significant advances, the field of genetic circuit design continues to face several challenges. A primary issue is context-dependence and lack of true modularity, where the function of a biological part can change depending on its genetic environment, host cell type, and growth conditions [6] [19]. Furthermore, introducing synthetic circuits imposes a metabolic burden on the host, which can reduce growth rates and select for mutant cells that have inactivated the circuit, thereby limiting its evolutionary longevity [21] [5].

Future progress hinges on developing more robust and predictable engineering frameworks. Key strategies include:

- Host-Aware Modeling: Using multi-scale models that account for host-circuit interactions, resource competition, and evolutionary dynamics to design more stable circuits [5].

- Circuit Compression: Designing smaller, more efficient circuits with fewer genetic parts to minimize metabolic burden, as exemplified by Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) [21].

- Advanced Control Strategies: Implementing genetic feedback controllers that can sense and regulate circuit function or burden to enhance long-term performance [5].

As these tools and principles become more sophisticated, the potential for genetic circuits to revolutionize therapeutics, bioproduction, and fundamental biological research will continue to expand.

In synthetic biology, the relationship between input signals and output gene expression is governed by transfer functions, which are quantitative representations of how biological components process dynamic information. These functions are fundamental to engineering predictable genetic circuits, as they define the input-output relationships that determine circuit behavior [22]. Biological information can be encoded within the dynamics of signaling components, which has been implicated in a broad range of physiological processes including stress response, oncogenesis, and stem cell differentiation [22]. Transfer functions enable researchers to move beyond simple qualitative understanding of gene regulation to a quantitative, predictive framework essential for robust circuit design.

The study of transfer functions intersects with multiple disciplines, including control theory, information theory, and molecular biology. By applying principles from information theory, promoters can be viewed as information transfer channels, with their capacity measured in bits [22]. Similarly, drawing from process control, promoters can be treated as unit processes with dynamic input-output transfer functions [22]. This multidisciplinary approach provides powerful insights into the fundamental principles governing gene regulation and enables more sophisticated engineering of biological systems for therapeutic applications, biosensing, and bioproduction.

Theoretical Framework: Concepts and Quantitative Principles

Key Concepts in Gene Expression Dynamics

The quantitative analysis of gene expression dynamics relies on several fundamental concepts:

Transfer Functions: Mathematical representations that describe the relationship between input signals (e.g., transcription factor concentration, light induction) and output responses (e.g., protein expression, fluorescence). These can be represented as equations or curves showing how output depends on input levels [22] [23].

Gene Expression Noise: Fluctuations in gene expression that occur even in isogenic populations under homogeneous conditions. Noise originates from various sources including transcriptional bursting, epigenetic modifications, and stochastic biochemical reactions with finite biomolecules [23].

Mutual Information: An information theory metric that quantifies the reliability of information transfer through biological channels. In gene expression, it measures how much information about input dynamics can be extracted from output responses [22].

Filtering Behaviors: The ability of promoters to selectively respond to specific dynamic patterns in input signals, analogous to electronic filters. These include low-pass, high-pass, and band-pass behaviors that allow frequency-dependent response patterns [22].

Mathematical Foundations

The quantitative description of gene expression dynamics often employs differential equation models that capture the kinetics of transcription and translation. For a simple gene expression process, the rate of change of protein concentration can be described as:

d[P]/dt = k_t*[mRNA] - δ_p*[P]

Where [P] is protein concentration, k_t is the translation rate constant, [mRNA] is mRNA concentration, and δ_p is protein degradation rate. More sophisticated models incorporate additional factors such as resource competition, feedback mechanisms, and epigenetic effects [5].

The transfer function can be represented as a normalized input-output relationship. For many inducible systems, this follows a sigmoidal function:

Output = (Input^n) / (K^n + Input^n)

Where K is the activation coefficient and n is the Hill coefficient representing cooperativity [23]. This mathematical formalism enables quantitative prediction of circuit behavior and facilitates the design of synthetic genetic systems with desired properties.

Experimental Methods for Mapping Transfer Functions

Optogenetic Approaches for Dynamic Control

Optogenetic systems provide unparalleled temporal precision for probing transfer functions by enabling dynamic control of transcription factor activity with light. The experimental workflow involves several key components:

Optogenetic Hardware: Programmable LED arrays controlled by platforms such as Arduino Due enable precise delivery of light patterns with varying amplitude, frequency, and pulse width to cells cultured in multi-well formats [22].

Biological Components: A light-sensitive system such as GAVPO or CRY2/CIB1 is implemented, where a cryptochrome (CRY2) fused to a DNA-binding domain interacts with its partner (CIB1) fused to a transcriptional activation domain (e.g., VP16) upon blue light exposure [22] [23].

Reporter System: Genomically integrated fluorescent reporters (e.g., mCherry, mRuby3) under control of synthetic promoters containing binding sites for the optogenetic transcription factor enable quantitative readout of gene expression [22] [23].

A representative experimental protocol for mapping transfer functions using optogenetics includes the following steps:

System Calibration: Expose cells to constant light of varying intensities to determine the dynamic range and identify sub-saturation amplitudes that enable comprehensive coverage of the parameter space [22].

Dynamic Stimulation: Program LED arrays to deliver 119 or more distinct input patterns modulating pulse frequency (2×10⁻⁵ to 1×10⁻¹ sec⁻¹), amplitude (6×10⁹ to 6×10¹⁰ au), and pulse width (5 to 3600 seconds) [22].

Output Measurement: Harvest cells after 14 hours of stimulation and measure reporter fluorescence using flow cytometry to obtain single-cell resolution expression data [22].

Noise Characterization: For pulse-width modulation studies, implement light periods of 400 minutes or longer to investigate effects on expression heterogeneity [23].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters for Optogenetic Transfer Function Mapping

| Parameter | Range Tested | Biological Significance | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude | 6×10⁹ to 6×10¹⁰ au | Determines activation strength | Flow cytometry |

| Frequency | 2×10⁻⁵ to 1×10⁻¹ sec⁻¹ | Encodes dynamic information | Time-lapse imaging |

| Pulse Width | 5 to 3600 seconds | Affects epigenetic memory | Single-cell RNA imaging |

| Total Signal (AUC) | Product of parameters | Relates to total activation | Endpoint fluorescence |

Chromatin Regulation Screening

Chromatin state significantly influences transfer functions by modifying epigenetic landscape and chromatin accessibility. A systematic approach to investigating these effects involves:

Chromatin Regulator Library: Construction of a library of over 100 orthogonal chromatin regulators (CRs) including histone modifiers, chromatin remodelers, and DNA methylation enzymes [22].

Locus-Specific Targeting: Fusion of chromatin regulators to DNA-binding domains enabling specific recruitment to the reporter promoter, bypassing pleiotropic effects of global chromatin perturbations [22].

Screening Platform: Combination of targeted CR recruitment with dynamic optogenetic stimulation to comprehensively map how different chromatin states affect promoter transfer functions [22].

The experimental workflow for chromatin regulation studies involves:

CR Library Delivery: Introduce chromatin regulator fusion constructs into cells containing the optogenetic reporter system.

Dynamic Stimulation with CR Recruitment: Apply dynamic light patterns while constitutively recruiting specific chromatin regulators to the target promoter.

Multiparameter Analysis: Measure effects on mean expression, noise, filtering behavior, and mutual information to characterize how different chromatin modifications alter the promoter's transfer function [22].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Mapping Transfer Functions

Quantitative Analysis of Transfer Functions

Information-Theoretic Approaches

Information theory provides powerful tools for quantifying the reliability of information transfer through gene regulatory systems. The mutual information between input signals and output responses measures how much uncertainty about the input is reduced by observing the output [22].

The experimental approach involves:

Stimulus Design: Application of diverse dynamic input patterns covering the parameter space of amplitude, frequency, and pulse width modulation.

Response Characterization: Measurement of output distributions for each input pattern using single-cell fluorescence data.

Mutual Information Calculation: Computation of mutual information using the equation:

MI(S;R) = ∑_s∈S ∑_r∈R p(s,r) log₂(p(s,r)/(p(s)p(r)))

Where S represents the set of input signals, R represents the set of output responses, p(s) and p(r) are marginal probability distributions, and p(s,r) is the joint distribution [22].

Application of this approach to eukaryotic promoters has revealed an information transfer limit of approximately 1.7 bits for a single promoter, with frequency modulation carrying the greatest amount of transmittable information and amplitude the least [22].

Noise Analysis and Control Strategies

Gene expression noise presents a significant challenge for precise circuit control. Quantitative analysis has revealed that in mammalian light-inducible systems, constant induction results in bimodality and large noise in gene expression [23]. The coefficient of variation (CV) follows a bell-shaped profile across light intensities, with the highest noise levels (CV ~2.5) induced at intermediate light intensities [23].

Mechanistic studies indicate that this noise originates from an interplay between transcriptional activators and histone regulators. The transcriptional activator stochastically binds to the promoter and recruits CBP/p300 coactivators, which facilitate recruitment of the pre-initiation complex while also acetylating histones to maintain chromatin in an active state [23].

Strategies for noise control include:

Pulse-Width Modulation: Illumination with long periods (400 minutes or longer) reduces noise by alternating cells between high and low states with smaller heterogeneity [23].

Epigenetic Manipulation: Simultaneous attenuation of CBP/p300 and HDAC4/5 reduces heterogeneity in expression of endogenous genes [23].

Feedback Control: Implementation of negative feedback loops using transcriptional or post-transcriptional regulators to suppress expression fluctuations [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Gene Expression Analysis

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Information | MI(S;R) = ∑∑ p(s,r) log₂(p(s,r)/(p(s)p(r))) |

Information transfer capacity | 1.7 bit limit for single promoter [22] |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | σ/μ |

Relative noise level | CV ~2.5 at intermediate induction [23] |

| Half-Life (τ₅₀) | Time for output to fall by 50% | Evolutionary longevity | Circuit persistence metric [5] |

| Filtering Behavior | Frequency-dependent response | Signal processing capability | Band-pass, low-pass patterns [22] |

Computational Modeling of Gene Regulatory Networks

Modeling Frameworks and Approaches

Computational models are essential for integrating multi-scale data and generating predictive understanding of gene regulatory networks. Several modeling frameworks have been developed, each with distinct strengths and limitations:

Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs): Use continuous variables and differential equations to represent gene expression changes as a function of other genes. Advantages include accurate dynamic modeling, while disadvantages include computational complexity with large networks [24] [25].

Bayesian Networks: Combine probability and graph theory to model GRN properties based on conditional dependencies. Advantages include flexibility in combining data types, while disadvantages include sensitivity to algorithm choices [25].

Information Theory Methods: Use scores such as mutual information and conditional mutual information to identify gene interactions. Advantages include low computational cost and ability to discover large GRNs from limited data [25].

Boolean Networks: Represent genes with Boolean variables and discrete expression levels using logical functions. Advantages include easy interpretation and capturing dynamic behavior, while disadvantages include information loss from discretization [25].

Multi-Scale Host-Aware Modeling

For synthetic biology applications, host-aware modeling frameworks that capture interactions between synthetic circuits and host physiology are particularly valuable. These models incorporate:

Resource Competition: Accounting for competition for limited cellular resources such as ribosomes, nucleotides, and energy [5].

Burden Effects: Modeling how circuit expression impairs host growth fitness, creating selection pressure for loss-of-function mutations [5].

Evolutionary Dynamics: Simulating mutation events and competition between different strains in a population over multiple generations [5].

A representative host-aware model structure includes:

Gene Expression Module: Describing transcription, translation, and degradation of circuit components.

Host Physiology Module: Capturing growth rate dependence on resource availability.

Population Dynamics Module: Simulating competition between strains with different circuit mutations.

This multi-scale approach enables prediction of evolutionary longevity and guides design of more robust genetic circuits [5].

Figure 2: Computational Modeling of Gene Regulation

Applications in Therapeutic Development

Synthetic Gene Circuits for Cancer Therapy

Transfer function principles enable design of intelligent therapeutic systems with enhanced specificity and safety profiles. In oncology, key applications include:

CAR-T Cell Control: Engineering chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells with synthetic gene circuits that improve safety through regulated activity. These include small molecule-inducible caspase suicide switches for mitigating toxicity and protease-regulated CAR-T cell receptors that enhance tumor selectivity [26].

Solid Tumor Targeting: Developing circuits that respond to intracellular cancer markers such as transcription factors, microRNAs, and splicing factor mutations that are inaccessible to conventional surface-targeting approaches [26].

Combination Therapies: Implementing circuits that coordinate delivery of multiple therapeutic agents in response to tumor-specific signals, enhancing efficacy while reducing off-target effects [26].

Metabolic Disease Management

Synthetic gene circuits offer promising approaches for dynamic regulation of metabolic disorders through self-regulating systems:

Closed-Loop Therapy: Designing circuits that sense metabolic biomarkers and respond with appropriate therapeutic outputs without external intervention [26].

Glucose Homeostasis: Developing insulin-secreting circuits that maintain physiological glucose levels through appropriate feedback control mechanisms [26].

Precision Modulation: Creating systems that titrate therapeutic activity based on disease severity and temporal patterns, providing personalized treatment profiles [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Transfer Function Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optogenetic Systems | CRY2/CIB1, GAVPO, PhyB/PIF | Dynamic control of TF activity | High temporal resolution, reversibility [22] [23] |

| Chromatin Regulators | CBP/p300, HDAC4/5, histone methyltransferases | Epigenetic landscape manipulation | Tunable gene expression, noise control [22] [23] |

| Reporter Systems | mCherry, mRuby3, GFP, GUS | Quantitative output measurement | Single-cell resolution, flow compatibility [22] [27] |

| Inducible Systems | Tet-On, LightOn, chemical inducers | Controlled gene expression | Adjustable dynamics, minimal background [23] |

| Computational Tools | Host-aware modeling frameworks, ARACNe, WGCNA | Network analysis and prediction | Multi-scale integration, predictive power [5] [25] |

The quantitative foundation of transfer functions provides essential principles for understanding and engineering gene expression dynamics in synthetic biology. Key insights emerging from current research include:

Eukaryotic promoters function as sophisticated information processing units with quantifiable limits to their information transfer capacity [22].

Chromatin state serves as a tunable parameter that can completely alter the input-output transfer function of a promoter without changing its sequence [22].

Noise in gene expression originates not only from stochastic biochemical reactions but also from dynamic interactions between transcriptional activators and epigenetic regulators [23].