Strategic Optimization of Biomass and Product Yield in Metabolic Engineering: From Foundational Principles to Industrial Translation

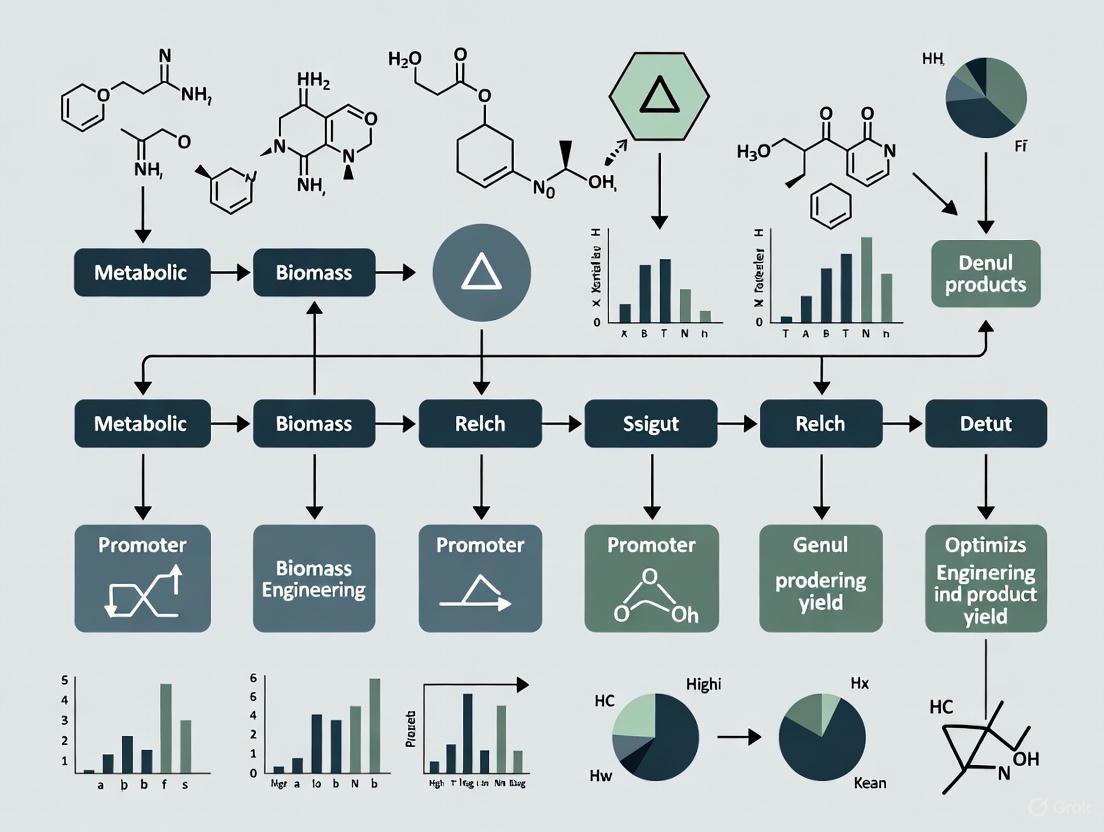

This comprehensive review addresses the central challenge of optimizing biomass utilization and product yield in metabolic engineering, a critical pursuit for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strategic Optimization of Biomass and Product Yield in Metabolic Engineering: From Foundational Principles to Industrial Translation

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the central challenge of optimizing biomass utilization and product yield in metabolic engineering, a critical pursuit for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles of microbial cell factories and feedstock design, followed by an in-depth analysis of advanced engineering methodologies including CRISPR-Cas systems and dynamic pathway control. The article provides systematic troubleshooting frameworks for overcoming metabolic bottlenecks and burden, and evaluates validation strategies through analytical technologies and economic viability assessment. By synthesizing current knowledge and emerging trends, this work serves as a strategic guide for advancing microbial production systems toward industrial-scale application in biomedical and chemical synthesis.

Building the Foundation: Microbial Cell Factories and Feedstock Design for Enhanced Bioproduction

The field of biofuels has undergone a profound evolution, transitioning from first-generation fuels derived from food crops to advanced biofuels produced through sophisticated metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. This progression addresses critical limitations of early biofuels, including the "food versus fuel" debate, low energy densities, and incompatibility with existing infrastructure. Modern biofuel research now focuses on engineering microbial cell factories to efficiently convert non-food biomass into high-energy, infrastructure-compatible fuels. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for researchers optimizing biomass and product yield in this rapidly advancing field.

Biofuel Generations: Technical Specifications and Evolution

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of different biofuel generations, highlighting the technological evolution in this field.

Table 1: Evolution of Biofuel Generations from Feedstock to Technical Challenges

| Generation | Primary Feedstocks | Representative Biofuels | Key Advantages | Technical Limitations & Research Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Corn, Sugarcane, Vegetable Oils | Bioethanol, Biodiesel | Mature technology, high production volume | "Food vs. fuel" conflict, lower energy density than gasoline [1] [2] |

| Second | Agricultural residues (e.g., straw), non-food crops, lignocellulosics | Cellulosic ethanol, Biomass-to-Liquid (BTL) fuels | Utilizes non-edible biomass, reduces land-use conflict | Recalcitrance of lignocellulose, inhibitor formation during pretreatment, inefficient C5 sugar fermentation [2] [3] |

| Third/Advanced | Algae, non-edible oils, synthetic syngas/COâ‚‚ | Isobutanol, n-Butanol, Farnesene, Fatty Acid-derived biofuels | Higher energy density, infrastructure compatibility, use of waste carbon streams | Low native yields in industrial hosts, metabolic burden, toxicity of products to microbial hosts [4] [1] [3] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges in Metabolic Engineering

FAQ 1: How can I overcome the inherent recalcitrance of lignocellulosic biomass for efficient sugar release?

Challenge: The complex structure of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose in plant biomass limits enzyme accessibility, reducing sugar yields for fermentation [5] [3].

Solutions:

- Enzyme Cocktail Optimization: Use a synergistic mixture of endoglucanases (break internal cellulose bonds), exoglucanases (act on chain ends), and β-glucosidases (convert cellobiose to glucose). For hemicellulose, incorporate xylanases and β-xylosidases [3].

- Engineer Microbial Consortia: Develop a co-culture system where one specialist strain produces mini-scaffoldins (e.g., mini CipA) and others produce different cellulases. This biomimicry of natural cellulosomes has been shown to enable direct ethanol production from cellulose [3].

- Host Engineering: In S. cerevisiae, overexpress genes for β-glucosidase and cellobiose transporters to enhance the uptake and utilization of cellodextrins [3].

FAQ 2: My microbial host shows inhibited growth and low productivity when using pretreated lignocellulosic hydrolysate. What are the main inhibitors and how can I mitigate their effects?

Challenge: Pretreatment generates microbial growth inhibitors like furfural, hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), and acetic acid, which derail metabolism and fermentation [3].

Solutions:

- Genetic Engineering for Tolerance:

- In E. coli: Furfural depletes NADPH via the enzyme YqhD. Delete the

yqhDgene and overexpress thepntABtranshydrogenase to rebalance NADPH/NADH pools. Supplementing with cysteine can further alleviate growth inhibition [3]. - Overexpress native oxidoreductases like

FucOto convert inhibitors into less toxic alcohols [3].

- In E. coli: Furfural depletes NADPH via the enzyme YqhD. Delete the

- Process Optimization: Develop a robust detoxification protocol post-pretreatment, such as overlining (pH adjustment) or use of adsorbent resins, to remove inhibitors before fermentation.

FAQ 3: I have engineered a synthetic pathway for an advanced biofuel (e.g., isobutanol), but the titer remains low. How can I re-route metabolic flux to my product?

Challenge: Native metabolism efficiently directs carbon towards growth, not the desired product, leading to low yields [4] [1].

Solutions:

- Delete Competing Pathways: Knock out genes involved in byproduct formation. For n-butanol production in E. coli, deleting

ldhA(lactate),adhE(ethanol),frdBC(succinate), andpta(acetate) redirected carbon flux and increased n-butanol production three-fold [1]. - Dynamic Metabolic Regulation: Implement biosensor-regulated circuits. A transcription factor-based biosensor can detect a key intermediate and dynamically upregulate your pathway enzymes or downregulate competing pathways in real-time, optimizing flux without manual intervention [5].

- Enzyme Engineering: Use directed evolution or computational design to improve the catalytic efficiency (

kcat/Km) of rate-limiting enzymes in your synthetic pathway and reduce feedback inhibition [4].

FAQ 4: The biofuel I am producing is toxic to the microbial host at low concentrations, limiting the final titer. What strategies can improve tolerance?

Challenge: Advanced biofuels like butanol are often toxic to production hosts, limiting the achievable titer, rate, and yield [1].

Solutions:

- Evolutionary Engineering: Subject the engineered host to gradually increasing concentrations of the biofuel over many generations. Select for mutants with improved growth and use whole-genome sequencing to identify underlying tolerance mutations.

- Membrane Engineering: Modify membrane lipid composition by overexpressing genes for saturated fatty acids or trans-unsaturated fatty acids to reduce membrane fluidity and permeability to the biofuel.

- Efflux Pumps: Engineer or introduce specific transporter systems that actively export the biofuel from the cell, reducing intracellular accumulation.

FAQ 5: How can I efficiently screen large mutant libraries for strains with improved biofuel production or tolerance?

Challenge: Identifying high-performing clones from a library of thousands or millions of variants is slow and labor-intensive with traditional analytics.

Solution: Implement Biosensor-Driven High-Throughput Screening.

- Principle: Genetically encode a biosensor that produces a fluorescent signal (e.g., GFP) in response to the intracellular concentration of your target biofuel or a key pathway intermediate [5].

- Workflow:

- Construct a Library: Create a diverse mutant library of your production host.

- Integrate the Biosensor: Incorporate a biosensor circuit that is activated by your product.

- Sort Cells: Use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to isolate the most fluorescent cells, which are the highest producers.

- Validate: Cultivate the sorted clones and analytically confirm improved biofuel production.

Diagram: Biosensor Workflow for High-Throughput Screening

Experimental Protocols for Key Metabolic Engineering Workflows

Protocol 1: Constructing a Biosensor for Dynamic Metabolic Regulation

This protocol outlines the creation of a transcription factor (TF)-based biosensor for real-time monitoring and control of a metabolic pathway [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Plasmid Backbone: A low/medium-copy number plasmid with a multiple cloning site (e.g., pSC101 ori).

- Reporter Gene: A gene encoding a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP, mCherry) or an enzyme for selection (e.g., antibiotic resistance).

- Inducible Promoter: A promoter sequence recognized by the chosen transcription factor (e.g.,

Ptrc,Plac). - Transcription Factor Gene: The gene for the TF that specifically binds your molecule of interest (e.g., a LuxR homolog for acyl-homoserine lactones).

Methodology:

- Identify Components: Select a transcription factor (TF) and its cognate promoter (

P_sensor) that is naturally activated/repressed by your target metabolite or a suitable proxy. - Clone Biosensor Circuit: Assemble a genetic circuit where

P_sensorcontrols the expression of your reporter gene. Clone the gene for the TF onto the same plasmid or integrate it into the genome under a constitutive promoter. - Characterize In Vivo: Transform the biosensor into your host strain. Grow cultures and expose them to a range of known concentrations of the target metabolite. Measure the resulting fluorescence (or other output) to create a standard curve of response.

- Integrate with Control Circuitry: For dynamic regulation, use

P_sensorto control the expression of a key metabolic enzyme in your biofuel pathway, creating a feedback loop.

Protocol 2: Engineering n-Butanol Production inE. colifrom the Traditional Fermentative Pathway

This protocol details the expression of a heterologous n-butanol pathway in the user-friendly host E. coli [1].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Host Strain: E. coli MG1655 or a derivative.

- Pathway Genes: Genes from Clostridium acetobutylicum:

thl(thiolase),hbd(3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase),crt(crotonase),bcd(butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase),etfAB(electron transfer flavoprotein),adhE2(butanol dehydrogenase). - Expression Vectors: Use plasmids with compatible origins of replication and selective markers (e.g., pETDuet series, pCDFDuet series) for balanced expression.

- Knockout Primers: Designed for deleting competing pathway genes (

ldhA,adhE,frdBC,pta).

Methodology:

- Pathway Assembly: Codon-optimize and synthesize the clostridial n-butanol pathway genes. Assemble them on one or more expression plasmids under the control of inducible promoters (e.g.,

P_BAD,P_T7). - Delete Competing Pathways: Use CRISPR-Cas9 or λ-Red recombineering to sequentially delete genes encoding lactate dehydrogenase (

ldhA), alcohol dehydrogenase (adhE), fumarate reductase (frdBC), and phosphate acetyltransferase (pta). - Evaluate Gene Variants: Test the performance of alternative genes, such as substituting the native

thlwith E. coli'satoB(acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase), to optimize flux. - Fermentation and Analysis: Cultivate the engineered strain anaerobically in a bioreactor with glucose or other carbon sources. Monitor growth and analyze broth samples for n-butanol and byproducts using GC-MS or HPLC.

Diagram: Engineered n-Butanol Pathway in E. coli

Advanced Tools and Reagents for Next-Generation Biofuel Research

The following table catalogs essential reagents and tools for constructing and optimizing microbial biofuel producers, as discussed in the protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering of Biofuels

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precise genome editing for gene knockouts, knock-ins, and repression. | Deleting competing pathway genes (ldhA, adhE) in E. coli to enhance n-butanol yield [3]. |

| Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor | Detects specific intracellular metabolites and outputs a measurable signal (e.g., fluorescence). | High-throughput screening of mutant libraries for improved production of isoprenoid-based biofuels [5]. |

| Heterologous Pathway Genes (Codon-Optimized) | Introduces non-native metabolic capabilities into a user-friendly host. | Expressing the Clostridium n-butanol pathway in E. coli [1] or the xylose utilization pathway in S. cerevisiae [2]. |

| Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) | Enables simultaneous, automated mutagenesis of multiple genomic sites across a cell population. | Rapidly optimizing the expression levels of multiple genes in a synthetic operon without constructing individual plasmids [3]. |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) Software | Computational modeling of intracellular reaction rates to identify flux bottlenecks. | Identifying which enzyme in a fatty acid-derived biofuel pathway is limiting yield, guiding targeted overexpression [3]. |

Lignocellulosic biomass (LB), the most abundant renewable bioresource on Earth, presents a promising alternative for sustainable energy and industrial applications in the transition from a petro-economy to a bioeconomy [6] [7]. However, its inherent recalcitrance poses a significant challenge for successful deployment in biorefineries [6]. This recalcitrance stems from the complex and rigid structure of the plant cell wall, primarily composed of cellulose (30-60%), hemicellulose (20-40%), and lignin (15-25%) [8] [9]. These components form a dense, heterogeneous matrix where lignin acts as a protective barrier, binding cellulose and hemicellulose and making them resistant to microbial and enzymatic action [6] [8]. An efficient pretreatment process is therefore indispensable to deconstruct this complex structure, remove lignin, reduce cellulose crystallinity, and increase the accessibility of carbohydrates for subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation into valuable products like biofuels and biochemicals [6] [9].

Troubleshooting Common Pretreatment Challenges

Table 1: Common Pretreatment Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Sugar Yield After Hydrolysis | Incomplete lignin removal; Low cellulose accessibility; Inhibitor formation [6] [9]. | Optimize pretreatment severity (T, t, catalyst); Use combined pretreatment [8]; Apply inhibitor removal steps (overliming, washing) [6]. |

| High Inhibitor Concentration (e.g., Furans, Phenolics) | Overly severe pretreatment conditions (high T, low pH) leading to sugar degradation [6]. | Switch to milder methods (e.g., Liquid Hot Water, Alkali) [10]; Optimize process conditions; Employ detoxification methods [6]. |

| High Energy Consumption | Use of energy-intensive methods (e.g., mechanical comminution) alone [9]. | Combine mechanical with chemical pretreatment to reduce energy input [8] [9]; Use low-temperature biological pretreatments [9]. |

| Inefficient Lignin Removal | Pretreatment method not suited for feedstock lignin type (S/G/H ratio) [8]. | Select targeted methods like Organosolv or Alkali pretreatment [10]; Use solvent-based systems like Ionic Liquids [11] [10]. |

| Poor Mass Transfer & Handling | High solids loading leading to viscous slurries; Fiber and silica clogging pipes and valves [6]. | Reduce solids loading; Implement mechanical agitation; Use flow aids; Design equipment for high-solids operation [6]. |

Table 2: Feedstock Composition and Pretreatment Selection Guide

| Feedstock Type | Example | Key Compositional Traits | Recommended Pretreatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Residues | Corn Stover, Sugarcane Bagasse [6] | Moderate lignin content; High hemicellulose [9]. | Dilute Acid, Hydrothermal [10]. |

| Herbaceous Biomass | Switchgrass, Grasses [9] | Variable lignin; High ash/silica [6]. | Alkali, Ionic Liquids [10]. |

| Hardwoods | Poplar, Aspen [11] | High Syringyl (S) lignin unit content [8]. | Organosolv, Ionic Liquids [11] [10]. |

| Softwoods | Pine, Spruce | High Guaiacyl (G) lignin unit content; High recalcitrance [8]. | Sulfite-based, Organosolv, Ionic Liquids. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is pretreatment considered a major bottleneck in lignocellulosic biorefineries? Pretreatment is a crucial yet costly step that significantly impacts all downstream processes [10]. The high recalcitrance of biomass requires severe operational conditions (high temperature/pressure, chemicals), leading to high capital and operating costs [6]. Furthermore, an inefficient pretreatment can generate inhibitors that hamper subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation, reducing overall product yields and process economics [6] [8].

Q2: What are the key criteria for selecting an effective pretreatment method? An ideal pretreatment should: (a) avoid significant biomass size reduction, (b) preserve the hemicellulose fraction where possible, (c) minimize the formation of degradation products (inhibitors), (d) be energy-efficient, and (e) use a low-cost and/or recyclable catalyst while producing a high-value lignin co-product [9]. It must also be compatible with the specific feedstock and improve the overall economics of the integrated process [10].

Q3: My single pretreatment method is not yielding good results. What are my options? Combined pretreatment strategies are increasingly popular as they can overcome the limitations of single methods [8] [9]. For instance, a mild mechanical pretreatment (e.g., ball milling) can be combined with a chemical method (e.g., hot compressed water) to reduce particle size and crystallinity while minimizing energy consumption and inhibitor formation, leading to higher sugar yields with lower enzyme loading [8].

Q4: What are "green solvents" and how are they used in pretreatment? Green solvents are environmentally friendly alternatives to conventional, often harsh, chemicals. Key examples include:

- Ionic Liquids (ILs): Salts in liquid state that can effectively dissolve biomass components under mild conditions and are potentially recyclable [12] [10].

- Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES): Mixtures of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors with low toxicity and biodegradability, effective for lignin extraction [13] [12].

- Liquid Hot Water (LHW) & Supercritical COâ‚‚: Use water or COâ‚‚ under specific conditions to disrupt biomass structure without added chemicals [12] [10]. These solvents aim to selectively separate biomass components with intact structures for valorization, reducing environmental impact [12].

Q5: How can I reduce the cost and environmental footprint of my pretreatment process? Strategies include:

- Process Integration: Combining pretreatment steps or integrating them with downstream operations [11].

- Solvent Recovery: Developing facile and scalable methods to recover and recycle solvents like ILs [11].

- Utilizing Waste: Using waste streams, such as seawater in IL pretreatment, to reduce freshwater and chemical consumption [11].

- AI and Machine Learning: Employing predictive models to optimize pretreatment conditions and identify effective solvents, reducing experimental time and costs [13] [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Combined Mechano-Chemical Pretreatment

This protocol outlines a combined ball milling and hot water pretreatment for enhanced sugar recovery from woody biomass, adapted from recent research [8].

1. Principle: Mechanical milling reduces cellulose crystallinity and particle size, while subsequent hot water treatment removes hemicellulose, synergistically improving enzyme accessibility.

2. Materials:

- Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., poplar, pine)

- Planetary ball mill

- High-pressure reactor (e.g., Parr reactor)

- Deionized water

- Sieve shaker

3. Procedure: Step 1: Mechanical Pre-treatment.

- Air-dry biomass and knife-mill to pass a 2-mm screen.

- Load 10g of biomass and grinding balls (10mm diameter, 1:20 w/w biomass-to-ball ratio) into a ball mill jar.

- Mill at 300 rpm for 2 hours. Periodically reverse rotation to prevent caking.

- Sieve the milled powder to obtain a particle size of < 0.5 mm.

Step 2: Hydrothermal Pretreatment.

- Prepare a 10% (w/v) slurry of the ball-milled biomass in deionized water.

- Transfer the slurry to the high-pressure reactor.

- Treat at 180°C for 30 minutes with constant stirring.

- Rapidly cool the reactor to room temperature.

Step 3: Solid-Liquid Separation.

- Filter the slurry through a 0.22μm membrane.

- Wash the solid fraction (pretreated biomass) thoroughly with deionized water until neutral pH.

- Store the wet solid for hydrolysis or air-dry for composition analysis.

4. Analysis:

- Analyze the solid fraction for glucan, xylan, and acid-insoluble lignin content.

- Analyze the liquid hydrolysate for oligomeric and monomeric sugars (e.g., glucose, xylose) and potential inhibitors (furfural, HMF).

Protocol 4.2: Ionic Liquid (IL) Pretreatment for High-Quality Lignin

This protocol describes biomass pretreatment with a protic ionic liquid to produce highly digestible cellulose and a high-quality lignin stream suitable for valorization [11].

1. Principle: Ionic liquids effectively dissolve lignin and disrupt the crystalline structure of cellulose, leading to a highly amorphous cellulose-rich material upon regeneration.

2. Materials:

- Biomass (e.g., sorghum, switchgrass)

- 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([Câ‚‚Câ‚Im][OAc])

- Deionized water

- Oil bath with magnetic stirring

- Vacuum oven

3. Procedure:

- Biomass Preparation: Air-dry and mill biomass to 0.5-1.0 mm particle size.

- Loading: Mix 0.5g of biomass with 10g of [Câ‚‚Câ‚Im][OAc] in a 50mL round-bottom flask (5% w/w loading).

- Dissolution: Heat the mixture to 120°C with constant stirring (500 rpm) for 3 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere.

- Regeneration: Cool the solution to ~80°C and add 30 mL of anti-solvent (deionized water) with vigorous stirring to precipitate the biomass.

- Recovery: Recover the regenerated biomass by filtration using a Buchner funnel.

- Washing: Wash the solid cake thoroughly with deionized water (3 x 50 mL) to remove residual IL.

- Drying: Dry the pretreated biomass in a vacuum oven at 60°C overnight.

4. Downstream Processing & IL Recovery:

- The washed filtrate containing dissolved lignin and IL can be processed to recover both the IL (for reuse) and the lignin. Techniques such as evaporation or membrane separation can be used to concentrate the IL, while lignin can be precipitated by further dilution or pH adjustment [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Pretreatment Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Pretreatment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [Câ‚‚Câ‚Im][OAc]) | Dissolves lignin and cellulose, reducing cellulose crystallinity [11] [12]. | Effective for a wide range of feedstocks, including hardwoods and grasses [10]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Eco-friendly solvent for selective extraction of lignin and hemicellulose [13] [12]. | Choline chloride-Urea DES for lignin removal from agricultural residues. |

| Dilute Sulfuric Acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Catalyzes hemicellulose hydrolysis into monomeric sugars, disrupts lignin structure [10]. | Standard pretreatment for herbaceous biomass and agricultural residues [10]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Breaks ester bonds between lignin and carbohydrates (saponification), causing lignin solubilization [10]. | Alkali pretreatment is highly effective for low-lignin feedstocks like straws [10]. |

| Organosolv (e.g., Ethanol-Water) | Dissolves and extracts lignin, producing a high-purity, reactive lignin co-product [10]. | Often used with a catalyst (e.g., acid) for hardwoods and non-woody biomass. |

| Cellulase Enzyme Cocktails | Hydrolyzes pretreated cellulose into glucose. Contains endoglucanases, exoglucanases, and β-glucosidases [6]. | Used in enzymatic saccharification following pretreatment. |

| Nardosinonediol | Nardosinonediol, MF:C15H24O3, MW:252.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| hRIO2 kinase ligand-1 | hRIO2 kinase ligand-1, MF:C17H14N2O, MW:262.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Process Visualization and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the integrated decision-making process for selecting and optimizing a pretreatment strategy within a metabolic engineering research context.

Central Metabolic Pathways and Carbon Flux Fundamentals

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental trade-off in microbial metabolic engineering and how can it be managed? The primary trade-off is between cell growth and product synthesis. Engineered microbial cell factories often face inherent conflicts where optimizing for high product yield depletes metabolites and energy (ATP, NADPH) required for biomass synthesis, leading to diminished cellular fitness [14]. This can result in reduced volumetric productivity and increased process costs. Management strategies include:

- Pathway Engineering: Rewiring central metabolism to either decouple growth from production or create growth-coupled production where product formation is essential for survival [14].

- Dynamic Regulation: Implementing genetic circuits that temporally separate growth phase from production phase in response to cellular cues [14].

- Fermentation Process Control: Precisely tuning parameters like nutrient feed to direct metabolic flux toward the desired product [14].

FAQ 2: How does the presence of multiple nutrient sources influence biomass yield? In natural environments, microbes are often co-limited by multiple nutrients. Contrary to simple models, the overall biomass yield on a specific nutrient is not always independent of other available nutrients [15]. The interaction depends on the type of nutrients:

- Degradable nutrients (e.g., glucose) can be catabolized for energy.

- Non-degradable nutrients (e.g., some amino acids) can only serve as biomass precursors. The presence of one nutrient can negatively or positively affect the utilization efficiency of another, meaning the total produced biomass is influenced by both the combination and relative amounts of nutrients [15].

FAQ 3: What are the key considerations when selecting a microbial chassis for production? Choosing the right host organism is critical and should be based on [16]:

- Metabolic Resources: The host must supply ample precursors and cofactors (ATP, NADPH) for the target pathway.

- Toxicity: inherent tolerance to the product or intermediates.

- Secretion Capability: Efficiency in secreting the product for easier recovery.

- Available Toolkits: Ease of genetic engineering.

- Metabolic Adjustment: The extent of rewiring required for the host to optimally use the new pathway.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low or Unexpected Biomass Yield

Issue: The final biomass concentration in your fermentation is lower than predicted, or it varies unexpectedly with different nutrient mixtures.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Antagonism | Check if the yield of one nutrient decreases when a second is added [15]. | Experimentally determine the optimal ratio of nutrient sources. Avoid combinations that show strong negative mutual effects on utilization [15]. |

| Insufficient Energy Supply | Analyze the ATP and reducing power demands of your product pathway. | For products with high energy demands, consider strategies to boost ATP generation, such as using more energy-rich substrates or engineering energy metabolism [17]. |

| Incorrect Yield Assumption | Verify that the assumed biomass yield (Y_X/S) for your base nutrient is accurate. |

Determine the biomass yield for each nutrient individually in a defined medium before using them in mixtures [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Biomass Yield on Multiple Nutrients

- Medium Preparation: Prepare a series of M9 minimal media cultures with varying initial amounts of a single carbon source (e.g., 0 to 1.2 g/L glucose).

- Inoculation: Inoculate each culture with a standardized pre-culture of your microbial strain.

- Growth Monitoring: Incubate and monitor growth until stationary phase is reached, ensuring all nutrients and byproducts are consumed.

- Biomass Measurement: Record the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) at stationary phase. Convert OD600 to cellular dry weight using a pre-determined conversion factor.

- Calculation: Plot the produced biomass (∆B) against the initial nutrient amount. The slope of the linear fit is the overall biomass yield (

Y_X/D) for that nutrient [15]. - Co-utilization Test: Repeat the experiment, titrating a "measured nutrient" (e.g., xylose) while keeping a "base nutrient" (e.g., acetate) constant. A change in the slope for the measured nutrient indicates an interaction [15].

Problem 2: Poor Product Titer Due to Growth-Production Trade-Off

Issue: The microbial strain grows well but produces little of the target compound, or high production comes at the cost of severely impaired growth.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden | The heterologous pathway drains excessive precursors/energy from growth. | Implement dynamic regulation: design a genetic circuit that delays product synthesis until after the growth phase [14]. |

| Competition for Precursors | Key central metabolites (e.g., Acetyl-CoA, E4P) are limiting. | Employ orthogonal design: create parallel metabolic pathways to decouple precursor supply for growth and production [14]. |

| Lack of Selective Pressure | The product is not essential, so low-producing mutants outcompete high-producers. | Use growth-coupling: rewire metabolism so that product formation is essential for biomass synthesis [14]. |

Experimental Protocol: Growth-Coupling via a Pyruvate-Driven System This strategy couples the production of a target compound (e.g., anthranilate) to the regeneration of a central metabolite (pyruvate), essential for growth [14].

- Strain Engineering:

- Gene Disruption: Knock out key native pyruvate-generating genes (

pykA, pykF, gldA, maeB) in E. coli. This impairs growth on glycerol minimal medium due to insufficient pyruvate.

- Gene Disruption: Knock out key native pyruvate-generating genes (

- Pathway Introduction:

- Plasmid Expression: Introduce a plasmid expressing a feedback-resistant anthranilate synthase (

TrpEfbrG). - Coupling Logic: The anthranilate biosynthesis pathway releases pyruvate. This provides the only route to regenerate pyruvate, thereby directly linking product synthesis to the restoration of growth [14].

- Plasmid Expression: Introduce a plasmid expressing a feedback-resistant anthranilate synthase (

- Validation:

- Growth & Production: Cultivate the engineered strain in glycerol minimal medium. Monitor growth (OD600) and anthranilate production (e.g., via HPLC).

- Expected Outcome: Restoration of robust growth is accompanied by enhanced anthranilate production, demonstrating growth-coupling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|

| M9 Minimal Medium | A defined growth medium allowing precise control over nutrient sources and concentrations for yield studies [15]. |

| Degradable Carbon Sources (e.g., Glucose, Xylose) | Serve as primary substrates that can be catabolized to generate energy (ATP) and carbon skeletons for both biomass and product synthesis [15]. |

| Non-degradable Nutrients (e.g., Methionine for E. coli) | Function primarily as building blocks for biomass, used to study the effects of precursor availability on yield and metabolic flux [15]. |

| Feedback-resistant Enzymes (e.g., TrpEfbr) | Key engineered enzymes in biosynthetic pathways that are insensitive to end-product inhibition, enabling high-level metabolite overproduction [14]. |

| High-Fidelity (HF) Restriction Enzymes | Engineered enzymes for DNA assembly that minimize "star activity" (non-specific cutting), ensuring precise and reliable genetic constructs [18]. |

| Antimalarial agent 24 | Antimalarial agent 24|C20H16N4O2 |

| PAR4 antagonist 1 | PAR4 antagonist 1, MF:C26H21FN6O4S, MW:532.5 g/mol |

Selecting an optimal microbial chassis is a critical first step in metabolic engineering for optimizing biomass and product yield. A microbial chassis is the physical, metabolic, and regulatory foundation for engineering genetic circuits and pathways [19]. The ideal chassis is not a one-size-fits-all solution; rather, it is a strategic choice based on the target product, available feedstock, and process conditions [20] [19]. Historically, metabolic engineering has relied on a narrow set of well-characterized organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. However, a modern approach known as Broad-Host-Range (BHR) Synthetic Biology advocates for rationally selecting hosts from a diverse biological spectrum, treating the chassis itself as a tunable design parameter to enhance system performance and stability [20]. This guide provides a comparative analysis and troubleshooting resource for researchers navigating chassis selection among the three primary microbial platforms: bacteria, yeast, and microalgae.

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Chassis

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the three main types of microbial chassis to guide initial selection.

| Feature | Bacteria (e.g., E. coli, B. subtilis) | Yeast (e.g., S. cerevisiae) | Microalgae (e.g., C. reinhardtii, P. tricornutum) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Strengths | Rapid growth, high-yield protein synthesis, extensive genetic toolkits, well-understood physiology [19] | GRAS status, eukaryotic protein processing (PTMs), tolerance to low pH and organic acids, robust in fermentation [19] [21] | Photoautotrophic growth (uses COâ‚‚ and light), produces high-value natural products (e.g., carotenoids, PUFA), can use wastewater [20] [22] [23] |

| Common Products | Bioethanol, organic acids, recombinant proteins, secondary metabolites [19] [21] | Bioethanol, recombinant proteins, vaccines, organic acids, isoprenoids [24] [21] | Biodiesel (lipids), carotenoids (astaxanthin), omega-3 LC-PUFAs (EPA, DHA), terpenoids [22] [24] [23] |

| Typical Yield Metrics | MK-7: ~442 mg/L in optimized B. subtilis [25] | Xylose-to-ethanol conversion: ~85% in engineered S. cerevisiae [24] | Lipid content for biodiesel can exceed 50% of dry weight in engineered strains [24] |

| Key Metabolic Pathways | Native and engineered pathways in cytoplasm [21] | MVA pathway for isoprenoids in cytosol/ER [23] | MEP pathway in chloroplasts; some diatoms have both MEP and MVA pathways [23] |

| Genetic Tractability | High; vast collection of plasmids, CRISPR tools, and promoters available [19] | High; well-developed genetic systems, CRISPR tools, and episomal plasmids [21] | Moderate; tools are advancing (CRISPR/Cas9), but can be species-specific and hindered by complex metabolism [22] [23] |

To further aid in the selection process, the following decision pathway visualizes the logical workflow for choosing a chassis based on project goals.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does my genetic construct behave differently when moved from one host to another?

This is a common problem known as the "chassis effect," where identical genetic manipulations exhibit different behaviors depending on the host organism [20].

- Primary Cause: The introduced genetic construct interacts with the host's unique cellular environment. This includes competition for finite cellular resources (e.g., RNA polymerase, ribosomes, nucleotides), direct molecular interactions (e.g., transcription factor crosstalk), and differences in metabolic burden [20].

- Underlying Mechanisms:

- Resource Allocation: Expression of foreign genes perturbs the host's metabolic state, triggering resource reallocation that can unpredictably influence circuit function and growth [20].

- Divergent Parts Activity: Genetic parts like promoters and RBSs are host-dependent. A promoter's strength can vary based on host-specific sigma factors, and codon usage can affect translation efficiency [20].

- Metabolic Burden: High expression of heterologous pathways can overburden the host, leading to reduced growth, genetic instability, and selection for non-producing mutants [19].

- Solutions:

- Host-Agnostic Design: Use BHR genetic parts, such as promoters and origins of replication from the Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA) database, when possible [20].

- Resource-Aware Engineering: Model and engineer circuits to minimize resource competition. This can include using lower-copy plasmids or tuning expression levels to an optimal, non-burdening range [20].

- Rational Chassis Matching: Select a host whose native metabolism and physiology are aligned with your product. For example, use a host that naturally produces a precursor for your target compound [20] [19].

FAQ 2: My microalgal strain shows low yield of the target isoprenoid. How can I enhance flux through the pathway?

Microalgal metabolic pathways are often compartmentalized and regulated by many gene homologs, making pathway engineering complex [22] [23].

- Primary Cause: Limitation of key precursors Isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), and/or insufficient expression of limiting enzymes in the biosynthetic pathway [23].

- Underlying Mechanisms:

- Precursor Supply: The carbon flux from photosynthesis may not be efficiently directed toward the MEP/MVA pathways that generate IPP and DMAPP [22] [23].

- Rate-Limiting Enzymes: Specific enzymes in the pathway, such as DXS (1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase) in the MEP pathway, may have low native flux [23].

- Competing Pathways: Carbon may be diverted to storage molecules like starch or neutral lipids instead of the desired isoprenoid [22].

- Solutions:

- Overexpress Limiting Enzymes: Identify and overexpress rate-limiting enzymes (e.g., DXS, DXR, IDI) in the MEP pathway to increase precursor supply [23].

- Knock Out Competing Pathways: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to disrupt genes involved in storage compound synthesis (e.g., starch, lipids) to redirect carbon flux [22] [23].

- Engineer Key Synthases: Overexpress the terpene synthase genes responsible for the final cyclization or formation of your target isoprenoid (e.g., limonene synthase, bisabolene synthase) [23].

- Cofactor Engineering: Ensure an adequate supply of essential cofactors like NADPH and ATP by engineering central carbon metabolism [23].

FAQ 3: My engineered bacterium suffers from low productivity despite high yield in shake flasks. What is the issue when scaling up?

This often indicates a problem with bioprocess stability and strain robustness under industrial conditions.

- Primary Cause: The strain may lack the physiological robustness to tolerate stresses encountered in a bioreactor, such as substrate inhibition, product toxicity, or shear stress [19] [21].

- Underlying Mechanisms:

- Substrate/Product Toxicity: Accumulation of the target product or inhibitory compounds in the feedstock (e.g., furfurals in lignocellulosic hydrolysates) can halt growth and production [21].

- Genetic Instability: The engineered pathway may impose a metabolic burden, leading to plasmid loss or mutations that inactivate the pathway over time, especially in long-term fermentation without antibiotic selection [20] [19].

- Poor Mass Transfer: Inadequate mixing or gas transfer (Oâ‚‚, COâ‚‚) in large-scale fermenters can create gradients, forcing the cells to operate in suboptimal and dynamic environments [26].

- Solutions:

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Subject the engineered strain to prolonged growth under selective pressure (e.g., high product concentration) to evolve mutants with enhanced tolerance and productivity [24].

- Process Optimization: Use statistical methods like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to optimize critical parameters such as pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and induction timing [25].

- Pathway Integration: Integrate the heterologous pathway into the host genome to improve genetic stability, as an alternative to plasmid-based expression [19].

- Use Specialized Chassis: Employ non-traditional hosts with built-in tolerances. For example, Halomonas bluephagenesis is engineered for high-salinity production, reducing contamination risks [20].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Media Optimization for Enhanced Metabolite Production using RSM

This methodology details the statistical optimization used to significantly increase Menaquinone-7 (MK-7) production in Bacillus subtilis [25].

- Initial Screening (One Factor at a Time - OFAT): Systematically test individual factors (carbon source, nitrogen source, pH, temperature, inoculum size) to identify their rough optimal ranges and determine which have the most significant impact on yield [25].

- Experimental Design (Box-Behnken): Select the most influential factors identified in OFAT (e.g., carbon, nitrogen, incubation time) for a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design. A Box-Behnken design is efficient, requiring fewer experimental runs than a full factorial design [25].

- Regression Model Fitting: Perform the experiments as per the RSM design. Use the resulting yield data to fit a second-order polynomial equation that describes the relationship between the factors and the response (yield) [25].

- Analysis of Variance (ANOVA): Use ANOVA to validate the statistical significance of the model and its terms. A high R² value indicates the model explains most of the variation in the data [25].

- Prediction and Validation: The software (e.g., Design-Expert) will predict the optimal factor levels for maximum yield. Conduct a validation experiment under these predicted conditions to confirm the model's accuracy [25].

Protocol 2: Metabolic Engineering Workflow for Isoprenoid Production in Microalgae

This protocol outlines a general strategy for engineering microalgae, as demonstrated in diatoms and green algae for terpenoid production [22] [23].

- Pathway Analysis and Gene Selection:

- Identify the biosynthetic pathway for the target isoprenoid.

- Select key heterologous genes (e.g., terpene synthases) or native genes to overexpress (e.g., DXS from the MEP pathway).

- Choose species-specific, inducible or constitutive promoters (e.g., from the chloroplast) [23].

- Vector Construction and Transformation:

- Clone the selected genes into an expression vector suitable for the target microalga. For chloroplast engineering, use a vector with homologous regions for site-specific integration [22].

- Introduce the construct into the microalgal cells via biolistic particle delivery (gene gun) or agitation with silicon carbide whiskers [23].

- Screening and Selection:

- Screen transformants on selective media (e.g., containing antibiotics).

- Confirm integration of the transgene via PCR and Southern blotting.

- Analyze transcript levels using RT-qPCR [23].

- Phenotypic and Metabolomic Analysis:

- Iterative Engineering:

The following diagram illustrates this multi-step engineering workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their applications for chassis engineering and optimization, as cited in the literature.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Precision genome editing for gene knockout, knock-in, and regulation [22] [24] | Generating stable Phaeodactylum tricornutum mutants with improved lipid and carotenoid production [22]. |

| Broad-Host-Range Vectors (e.g., SEVA) | Modular plasmid systems that function across diverse bacterial species, promoting genetic part interoperability [20] | Deploying the same genetic circuit in different Proteobacteria to study and leverage chassis effects [20]. |

| Design-Expert Software | Statistical software for designing experiments (e.g., RSM, OFAT) and modeling complex variable interactions [25] | Optimizing concentrations of lactose, glycine, and incubation time to maximize MK-7 yield in Bacillus subtilis [25]. |

| Non-Enzymatic Dissociation Buffers | Gently detach adherent cells without degrading surface proteins, preserving epitopes for analysis [27] | Preparing adherent mammalian or microalgal cells for flow cytometry analysis without damaging surface markers [27]. |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., BMIMCl) | Efficient solvents for pretreating and fractionating lignocellulosic biomass to release fermentable sugars [21] | Pretreatment of agricultural residues (e.g., corn stover) to create feedstock for bacteria or yeast fermentations [21]. |

| DL-01 formic | DL-01 (formic)|ADC Drug-Linker Conjugate|RUO | DL-01 (formic) is a drug-linker conjugate for synthesizing Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs). For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| RS Domain derived peptide | RS Domain derived peptide, MF:C44H85N25O15, MW:1204.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Economic and Sustainability Considerations in Feedstock Selection

For researchers and scientists in metabolic engineering, selecting the appropriate feedstock is a critical decision that intersects with experimental success, economic viability, and environmental sustainability. This technical support guide addresses common challenges encountered during biomass and product yield optimization, providing targeted troubleshooting advice framed within a rigorous scientific context.

★ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How do I select a feedstock that does not compete with food resources? First-generation feedstocks, derived from food crops like maize and sugarcane, are increasingly criticized for creating food-versus-fuel dilemmas and contributing to deforestation [28]. To avoid this, prioritize second-generation feedstocks, such as agricultural residues (e.g., straw, husks) and forestry by-products, or third-generation feedstocks like algae [28]. These non-food biomass sources align with circular economy principles by promoting waste valorization and resource recovery [28].

2. What are the primary bottlenecks in achieving high yields from lignocellulosic biomass? The inherent recalcitrance of lignocellulosic biomass is a major barrier [29]. Its complex structure of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin resists enzymatic breakdown. To enhance yields:

- Employ advanced enzymes: Utilize engineered cellulases, hemicellulases, and ligninases to improve deconstruction [29].

- Leverage synthetic biology: Use CRISPR-Cas systems for precise genome editing of microbial hosts to enhance their resilience and substrate processing capabilities [29].

- Decouple energy and carbon metabolism: A novel strategy involves engineering microorganisms like E. coli to utilize external energy sources like hydrogen gas (Hâ‚‚) or formate, which frees more carbon from the feedstock to be directed toward the desired product instead of being oxidized for energy [30].

3. How can I improve the economic viability of my bio-production process? Focus on strategies that maximize product output per unit of feedstock.

- Strain Optimization: Use adaptive laboratory evolution and AI-driven strain optimization to enhance microbial performance [29].

- Process Integration: Implement consolidated bioprocessing to combine enzyme production, biomass hydrolysis, and sugar fermentation into a single step, reducing costs [29].

- Feedstock Efficiency: Technologies that decouple energy from carbon metabolism can redirect up to 86.6% of electrons from alternative energy sources like Hâ‚‚, significantly increasing product titers without requiring more sugar [30].

4. What guardrails are necessary to ensure the sustainability of biomass feedstocks? Adequate guardrails and accurate carbon accounting are essential to prevent negative impacts on climate, ecosystems, and food systems [31]. Key considerations include:

- Source Selection: Favor wastes and residues from municipalities, agriculture, and forestry over purpose-grown biomass crops [31].

- Land Use Change: Avoid feedstocks that risk inducing direct or indirect land use change, as this can increase greenhouse gas emissions [31].

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Apply standardized LCA frameworks to evaluate the true environmental impact of your feedstock choice [28].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Recalcitrance | Low sugar release after enzymatic hydrolysis | Lignin barrier, crystalline cellulose, insufficient pretreatment | 1. Optimize pretreatment (thermochemical, biological).2. Use enzyme cocktails with enhanced ligninases.3. Engineer feedstock plants for reduced lignin content [7]. |

| Microbial Performance | Low product titer/yield despite high sugar availability | Metabolic burden, inefficient pathway flux, toxicity | 1. Use CRISPR-Cas for precise pathway engineering [29].2. Implement modular co-culture systems.3. Decouple growth and production phases [32]. |

| Process Scalability | Inconsistent results when scaling from lab to bioreactor | Mass transfer limitations, feedstock heterogeneity, inhibitory compound buildup | 1. Employ high-throughput screening with mimicked industrial conditions.2. Use consolidated bioprocessing (CBP) [29].3. Integrate real-time monitoring and adaptive control. |

| Sustainability Metrics | High calculated carbon footprint | Energy-intensive pretreatment, feedstock transportation emissions | 1. Switch to waste-derived feedstocks (e.g., MSW, agricultural residues) [31] [28].2. Integrate process energy with renewable sources.3. Design processes for carbon capture and utilization (CCU). |

Quantitative Data for Feedstock Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for different feedstock categories to aid in evidence-based selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Feedstock Performance in Bio-production

| Feedstock Category | Example Organisms / Feedstocks | Max Reported Yield / Titer | Key Advantages | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Generation | Sugarcane, Maize | High ethanol yields (well-established) | Established supply chains, high fermentable sugar content | Food-vs-fuel conflict, high water/land use [28] |

| Second-Generation (Lignocellulosic) | Pennycress, Agricultural residues | ∼85% xylose-to-ethanol conversion in engineered S. cerevisiae [29] | Abundant, non-food resource, waste valorization | Recalcitrance to breakdown, requires pretreatment [29] [7] |

| Third-Generation (Algae) | Microalgae (e.g., Chlorella, Spirulina) | 91% biodiesel conversion efficiency from lipids [29] | High growth rate, does not require arable land | High cultivation cost, challenging biomass harvesting [28] |

| Engineered Microbes (C1 Feedstocks) | C. glutamicum, E. coli | 223.4 g/L lysine in C. glutamicum [32] | High growth rates, well-established genetic tools | Substrate cost, can require complex media |

| Decoupled Energy Systems | E. coli with Hâ‚‚ supplementation | 57.6% increase in mevalonate titer with formate [30] | Maximizes carbon conversion to product; theoretical max electron efficiency | Handling of gaseous substrates (Hâ‚‚), system integration |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Overcoming Lignocellulosic Recalcitrance

Objective: To efficiently liberate fermentable sugars from lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover, switchgrass) for downstream microbial fermentation.

Materials:

- Feedstock: Milled and dried lignocellulosic biomass (particle size ~2 mm).

- Enzymes: Commercial cellulase and hemicellulase cocktail (e.g., CTec3).

- Reagents: Sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0), sodium azide (to prevent microbial contamination).

- Equipment: Shaking incubator, centrifuge, HPLC system for sugar analysis.

Methodology:

- Pretreatment: Subject 1g of biomass to a dilute acid (e.g., 1% H₂SO₄) or alkaline (e.g., 1% NaOH) pretreatment at 121°C for 30-60 minutes. Neutralize the slurry afterward [28].

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Resuspend the pretreated biomass in sodium acetate buffer to a 10% (w/v) solid loading. Add cellulase enzymes at a loading of 15-20 mg protein/g glucan. Include 0.02% sodium azide.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at 50°C with constant agitation (150 rpm) for 72 hours.

- Analysis: Centrifuge samples at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 6, 24, 48, 72h). Analyze the supernatant via HPLC to quantify glucose, xylose, and inhibitor (e.g., furfural, HMF) concentrations.

- Troubleshooting: If sugar yield is low, consider optimizing pretreatment severity or supplementing with lignin-degrading enzymes.

Protocol 2: Decoupling Energy and Carbon Metabolism with Hâ‚‚/Formate

Objective: To enhance product yield by providing an external source of reducing power, thereby preventing carbon loss as COâ‚‚.

Materials:

- Strain: E. coli engineered to express an Oâ‚‚-tolerant hydrogenase (e.g., from Cupriavidus necator) and/or a formate dehydrogenase [30].

- Growth Media: Defined minimal media (e.g., M9) with acetate or glucose as carbon source.

- Gaseous Substrate: Hâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ gas mixture (e.g., 80/20) or sodium formate.

- Equipment: Bioreactor with gas impellers, gas cylinders, off-gas analyzer.

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow the engineered strain overnight in a suitable medium.

- Fermentation Setup: Inoculate a bioreactor containing minimal media with a carbon source. For Hâ‚‚ supplementation, sparge the culture with the Hâ‚‚/COâ‚‚ mixture at a controlled flow rate (e.g., 0.1 vvm). For formate supplementation, add a sterile stock solution to a final concentration of 10-50 mM.

- Monitoring: Monitor cell density (OD600), substrate consumption, and product formation (e.g., mevalonate) over time. Use an off-gas analyzer to measure COâ‚‚ evolution rates, which should decrease with effective Hâ‚‚/formate utilization.

- Metabolomic Analysis: Quench culture samples at mid-log phase for metabolomics to confirm redirection of carbon flux through target pathways like the glyoxylate shunt [30].

- Calculation: Calculate electron usage efficiency and the percentage reduction in COâ‚‚ evolution compared to a control without Hâ‚‚/formate.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Feedstock Selection Decision Pathway

Decoupling Carbon and Energy Metabolism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Advanced Feedstock Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Precise genome editing for strain and feedstock optimization. | Knocking out lignin biosynthesis genes in plants to reduce recalcitrance [7]. |

| Specialized Enzymes (Cellulases, Hemicellulases, Ligninases) | Breakdown of lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars. | Formulating enzyme cocktails for efficient hydrolysis of agricultural residues [29]. |

| Oâ‚‚-Tolerant Hydrogenase | Enables use of Hâ‚‚ as an energy source in aerobic bioprocesses. | Engineering E. coli to utilize Hâ‚‚, decoupling energy generation from carbon metabolism [30]. |

| Formate Dehydrogenase | Converts formate to COâ‚‚, generating reducing power (NADH). | Supplementing E. coli fermentations to enhance mevalonate production by providing external electrons [30]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Models | AI-driven prediction of optimal gene edits and fermentation parameters. | In silico design of microbial strains with enhanced product yield and substrate utilization [29] [7]. |

| Sirt2-IN-12 | Sirt2-IN-12|Potent SIRT2 Inhibitor for Research | |

| 5-HT7R antagonist 2 | 5-HT7R antagonist 2, MF:C16H16N2O, MW:252.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Engineering Methodologies: Pathway Design and Precision Editing Tools

CRISPR-Cas Systems for Precision Genome Editing and Regulation

Troubleshooting Guides

Common CRISPR Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Low Editing Efficiency

- Symptoms: Low frequency of indels or desired edits in the target cell population.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inefficient guide RNA (gRNA): Test 2-3 different gRNAs to identify the most effective one. Bioinformatics tools can predict efficiency, but empirical testing is best [33].

- Suboptimal delivery: Ensure your delivery method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors) is effective for your specific cell type [34].

- Low expression of CRISPR components: Verify that the promoters driving Cas and gRNA expression are active in your chosen cell line. Codon-optimize the Cas gene for your host organism and check the quality of your DNA/mRNA [34].

- Inaccessible chromatin state: Target a different region within the same exon that is not in a tightly packed chromatin structure [35].

Problem: Off-Target Effects

- Symptoms: Unintended indels or mutations at genomic sites with sequence similarity to your target.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Low gRNA specificity: Design gRNAs with high specificity using online tools that predict potential off-target sites. Select a gRNA sequence with minimal homology to other parts of the genome [35] [34].

- High nuclease concentration: Use a lower concentration of Cas nuclease and gRNA. Deliver CRISPR components as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex, which can reduce off-target effects compared to plasmid-based methods [33] [34].

- Cas9 variant: Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) engineered for greater specificity [34].

Problem: Irregular or Unexpected Protein Expression After Edit

- Symptoms: Inconsistent protein levels, unexpected isoform expression, or no knockout observed despite confirmed DNA edit.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Targeting the wrong exon: For gene knockouts, design gRNAs to target an exon common to all major protein-coding isoforms, preferably near the 5' end of the gene to increase the chance of introducing a premature stop codon [35].

- Alternative splicing: Use resources like Ensembl to map all gene isoforms and design your gRNA strategy accordingly [35].

- Mosaicism: The cell population may be a mixture of edited and unedited cells. Isolate single-cell clones and expand them to obtain a pure, homogeneously edited population [35] [34].

Problem: Cell Toxicity or Low Cell Survival

- Symptoms: High levels of cell death following transfection.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- High CRISPR component concentration: Titrate the concentrations of Cas nuclease and gRNA downwards to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [34].

- Innate immune response: Use chemically synthesized, modified gRNAs (e.g., with 2'-O-methyl analogs) instead of in vitro transcribed (IVT) gRNAs, as they can reduce immune stimulation and improve stability [33].

- Off-target activity: The toxicity may be due to excessive off-target cleavage. Re-assess gRNA specificity and consider using high-fidelity Cas variants [34].

Table 1: Quantitative Data from Metabolic Engineering Studies Utilizing CRISPR

| Product / Goal | Host Organism | Key Performance Metric | CRISPR or Metabolic Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Hydroxypropionic acid | Corynebacterium glutamicum | 62.6 g/L, Yield: 0.51 g/g glucose | Substrate engineering & Genome editing engineering [32] |

| L-Lactic acid | Corynebacterium glutamicum | 212 g/L, Yield: 97.9 g/g glucose | Modular pathway engineering [32] |

| Lysine | Corynebacterium glutamicum | 223.4 g/L, Yield: 0.68 g/g glucose | Cofactor engineering, Transporter engineering & Promoter engineering [32] |

| Butanol Yield Increase | Engineered Clostridium spp. | 3-fold increase in yield | CRISPR-Cas for precise genome editing to rewire metabolic pathways [36] |

| Biodiesel Conversion | Lipids | 91% conversion efficiency | Metabolic engineering optimized with enabling technologies like CRISPR [36] |

Experimental Protocol: Testing Guide RNA Efficiency

A critical step for a successful CRISPR experiment is validating the efficiency of your gRNA.

- Design: Select 2-3 gRNAs using a reputable design tool. Prioritize sequences with high predicted on-target scores and low off-target potential.

- Delivery: Introduce the gRNAs and Cas nuclease (as plasmid, mRNA, or RNP) into your target cells using an optimized transfection method.

- Harvest and Extract: 48-72 hours post-transfection, harvest the cells and extract genomic DNA.

- Analyze:

- Amplify: Use PCR to amplify the genomic region surrounding the target site.

- Assess Editing: Use one of the following methods:

- Sanger Sequencing: Sequence the PCR products and use trace decomposition software (e.g., TIDE, ICE) to quantify editing efficiency.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Provides the most accurate quantification of editing and can assess off-target effects.

- Enzymatic Mismatch Cleavage (T7EI): Digest heteroduplex DNA with T7 Endonuclease I and analyze by gel electrophoresis to estimate efficiency [33].

CRISPR Experiment Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General CRISPR Concepts

Q: What is CRISPR-Cas and how does it work? A: CRISPR-Cas is an adaptive immune system found in bacteria and archaea that has been repurposed for precise genome editing. The system consists of two key components: a guide RNA (gRNA) and a Cas nuclease (e.g., Cas9). The gRNA directs the Cas protein to a specific DNA sequence. The Cas protein then cuts the DNA at that location. When the cell repairs this cut, it can introduce changes to the DNA sequence, enabling gene knockouts, insertions, or corrections [37].

Q: What are the main types of CRISPR-Cas systems? A: CRISPR-Cas systems are divided into two classes [38]:

- Class 1 (Types I, III, and IV): Use multi-protein complexes to effect interference. For example, Type I uses a Cascade complex and the Cas3 nuclease [39] [38].

- Class 2 (Types II, V, and VI): Use a single, large Cas protein. This class is most widely used in biotechnology and includes:

Q: What is a PAM sequence and why is it important? A: The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) that lies immediately next to the DNA sequence targeted by the Cas nuclease. The Cas protein requires the presence of the PAM to recognize and bind to the target DNA. The PAM sequence varies depending on the specific Cas protein used (e.g., SpCas9 requires "NGG") and is a critical factor in determining where in the genome CRISPR can be targeted [40].

Application in Metabolic Engineering

Q: How can CRISPR-Cas systems be used to optimize biomass and product yield? A: CRISPR enables precise rewriting of cellular metabolism in several ways [36] [32]:

- Knockout Competing Pathways: Precisely delete genes that divert metabolic flux away from the desired product.

- Knockin Heterologous Pathways: Introduce entire new metabolic pathways from other organisms to produce novel compounds.

- Fine-Tuning Gene Expression: Use CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) to modulate the expression of key enzymes without altering the DNA sequence permanently, allowing for dynamic control of metabolic fluxes.

- Multiplexed Editing: Simultaneously edit multiple genomic loci, which is essential for complex traits influenced by many genes.

Q: What are some specific examples of CRISPR in metabolic engineering for biofuels? A: Advances in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, powered by CRISPR, have led to significant achievements in biofuel production [36]:

- Engineering S. cerevisiae for ~85% conversion efficiency of xylose to ethanol.

- A 3-fold increase in butanol yield in engineered Clostridium spp.

- Production of advanced biofuels like isoprenoids and jet fuel analogs with superior energy density.

Metabolic Engineering with CRISPR

Technical and Ethical Considerations

Q: What are the biggest safety concerns with CRISPR? A: The primary technical concerns are [37] [38]:

- Off-target effects: Unintended cuts at similar DNA sequences.

- On-target rearrangements: Large, unintended deletions or insertions at the correct target site after cutting.

- Immunogenicity: In therapeutic applications, the patient's immune system may react against the bacterial-derived Cas protein. Robust genotyping and careful gRNA design are essential to mitigate these risks. Regulatory agencies like the FDA provide oversight for clinical applications [37].

Q: What delivery methods are available for CRISPR components? A: Common delivery methods include [37]:

- Physical/Chemical: Electroporation or lipofection, which create temporary pores in the cell membrane.

- Viral Vectors: Engineered viruses (e.g., AAV, lentivirus) that deliver DNA encoding CRISPR components.

- Direct Delivery: Using pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes of Cas protein and gRNA, which can reduce off-target effects and be "DNA-free." [33]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Cas Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease (e.g., Cas9, Cas12a) | The enzyme that cuts the target DNA. | Choose based on PAM requirement, editing efficiency, and size for delivery (e.g., Cas12a for AT-rich genomes) [33]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | A synthetic RNA that directs the Cas nuclease to the specific target DNA sequence. | Chemically synthesized, modified gRNAs can improve stability and editing efficiency and reduce immune stimulation [33]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | A pre-complexed unit of Cas protein and gRNA. | Enables rapid, DNA-free editing; can increase efficiency and reduce off-target effects [33]. |

| Delivery Vehicle | Method to introduce CRISPR components into cells (e.g., electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors). | Optimization is critical; choice depends heavily on cell type (immortalized, primary, stem cells) [35] [37]. |

| Genotyping Tools | Methods to confirm edits (e.g., T7EI assay, Sanger sequencing, NGS). | NGS is the gold standard for assessing on-target efficiency and profiling off-target sites [33] [34]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Tools for gRNA design, off-target prediction, and sequencing analysis. | Essential for designing specific gRNAs and analyzing the results of editing experiments [35] [34]. |

| Antibacterial agent 167 | Antibacterial agent 167, MF:C12H12F3N2NaOS, MW:312.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SSTR5 antagonist 3 | SSTR5 antagonist 3, MF:C31H36F2N2O5, MW:554.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Dynamic metabolic control represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, moving beyond static genetic modifications to implement genetically encoded systems that allow microbes to autonomously adjust their metabolic flux in response to internal metabolic states or external environmental cues [41]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing the fundamental challenge in bioprocessing: the inherent trade-off between cell growth and product formation. By decoupling these competing objectives, dynamic control strategies enable researchers to optimize both biomass accumulation and product yield, leading to significant improvements in the critical titer, rate, and yield (TRY) metrics that determine commercial viability [42] [41].

The core principle involves engineering biological circuits that function similarly to process control systems in traditional chemical manufacturing, using sensors to detect metabolic states and actuators to implement flux adjustments. These systems can operate through various control logics, including two-stage switches that separate growth and production phases, or continuous controllers that maintain optimal flux distributions throughout fermentation [43] [41]. As this field advances, researchers are developing increasingly sophisticated tools to implement these strategies effectively, addressing common experimental challenges through systematic troubleshooting and protocol optimization.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

FAQ: Addressing Frequent Implementation Issues

Q1: Why is my two-stage system failing to properly switch from growth to production phase?

A: This common issue typically stems from three main causes:

- Suboptimal Inducer Timing: Switching too early sacrifices biomass, while switching too late reduces productivity. Monitor growth phase carefully using OD600 measurements and initiate switching at mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8) for most E. coli systems [41].

- Insufficient Metabolic Burden Management: Production pathways impose substantial burden. Implement resource allocator circuits to balance heterologous expression with native cellular functions [41].

- Signal Degradation or Insensitivity: Ensure inducer stability and consider promoter engineering to increase sensitivity to lower inducer concentrations if using chemical inducers like IPTG or aTc [43].

Q2: How can I improve the stability of my autonomous dynamic control system over long fermentation periods?

A: Genetic instability and mutational escape are common in extended fermentations:

- Implement Redundancy: Use multiple parallel sensors for the same metabolite to reduce failure probability [41].

- Incorporate Population Control: Utilize quorum-sensing systems to synchronize behavior and suppress non-productive mutants [43] [41].

- Apply Evolutionary Pressure: Design systems where production capability correlates with survival, such as coupling antibiotic resistance genes to production pathway activation [41].

Q3: What causes low product yield despite high pathway expression in my dynamically controlled system?

A: This indicates potential metabolic imbalances:

- Cofactor Imbalance: Monitor NADPH/NADP+, ATP/ADP ratios and implement cofactor engineering strategies such as transhydrogenase expression [3].

- Toxic Intermediate Accumulation: Implement intermediate sensors to dynamically regulate flux before toxicity occurs [43].

- Insufficient Precursor Supply: Use flux analysis to identify bottleneck metabolites and engineer enhanced precursor supply through push-pull strategies [41].

Q4: How can I adapt dynamic control strategies for non-model organisms or novel pathways?

A: Expanding beyond model systems requires:

- Native Part Mining: Identify and characterize indigenous promoters, riboswitches, and biosensors from the host's regulatory network [41].

- Orthogonal System Implementation: Use heterologous sensors and circuits that function independently of host regulation [43].

- Modular Design: Build systems with standardized parts that can be tested and optimized independently before integration [41].

Performance Comparison of Dynamic Control Strategies

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Dynamic Control Implementations

| Control Strategy | Organism | Target Product | Improvement Achieved | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-stage (IPTG/aTc) | E. coli | Malate | 2.3-fold increase | Titer [43] |

| Two-stage (Temperature) | E. coli | L-threonine | 1.4-fold increase | Yield [43] |

| Two-stage (Light) | S. cerevisiae | Isobutanol | 1.6-fold increase | Titer [43] |

| Positive Feedback (Acetyl phosphate) | E. coli | Lycopene | 3-fold increase | Productivity [43] |

| Oscillation (FPP) | E. coli | Amorphadiene | 2-fold increase | Titer [43] |

| Quorum Sensing (LuxR/LuxI) | E. coli | Naringenin | 6.5-fold increase | Titer [43] |

| Two-stage (aTc) | E. coli | 1,4-BDO | ~2-fold increase | Titer [43] |

Optimization Parameters for Dynamic Control Systems

Table 2: Key Optimization Parameters for Dynamic Control Systems

| Parameter | Optimization Strategy | Measurement Technique | Target Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Switching Time | Monitor growth curve; switch at mid-log phase | OD600 measurements | OD600 0.6-0.8 for E. coli |

| Inducer Concentration | Dose-response curves for minimal burden | Fluorescence assays, growth rate monitoring | Lowest effective concentration |

| Sensor Sensitivity | Promoter engineering, ribosome binding site modification | Transcriptional reporter fusions | Dynamic range >10-fold |

| Response Time | Circuit minimization, elimination of bottlenecks | Time-course metabolomics | <1 cell division cycle |

| Metabolic Burden | Resource allocation circuits, orthogonal systems | Growth rate comparison, omics analysis | <20% growth impairment |

Experimental Protocols for Dynamic Metabolic Control

Protocol 1: Implementing a Two-Stage Fermentation System

Objective: Establish a robust two-stage fermentation process that decouples growth and production phases for enhanced product yield.

Materials:

- Engineered strain with inducible production pathway

- Appropriate culture medium

- Inducer molecules (e.g., IPTG, aTc, arabinose)

- Bioreactor or controlled fermentation system

- Analytics: HPLC, GC-MS, or spectrophotometer for product quantification

Methodology:

- Strain Engineering: Integrate a tightly regulated inducible system (e.g., T7, Tet, Ara) controlling your production pathway. Ensure the growth phase promoter shows minimal leakage [41].

- Growth Phase Optimization:

- Inoculate primary culture and grow overnight.

- Dilute to OD600 0.05 in fresh medium and monitor growth kinetics.

- Sample regularly to determine growth rate and metabolite profiles.

- Switch Point Determination:

- Induce at varying cell densities (OD600 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0) in parallel cultures.

- Compare final product titers to identify optimal switching point.

- Production Phase Optimization:

- After induction, monitor nutrient consumption and product formation.

- Adjust feeding strategy to maintain essential nutrients while limiting growth.

- Consider temperature shift or oxygen limitation to further suppress growth if needed.

- Process Validation:

- Perform triplicate fermentations using optimized parameters.

- Compare TRY metrics against constitutive expression controls.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If growth impairment occurs pre-induction, check for promoter leakage and consider alternative inducible systems.

- If product formation is low post-induction, verify inducer penetration and stability, and check for metabolic bottlenecks through flux analysis [41].

Protocol 2: Developing an Autonomous Metabolite-Responsive System

Objective: Create a self-regulating system that automatically adjusts metabolic flux in response to key metabolite concentrations.

Materials:

- Biosensor for target metabolite (native or engineered)

- Actuator components (promoters, regulatory proteins)

- Genetic assembly system (Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly)

- Metabolite standards for sensor characterization

- Flow cytometry for population heterogeneity analysis

Methodology:

- Biosensor Selection/Engineering:

- Identify natural transcription factors responsive to your pathway intermediate.

- Clone corresponding promoter elements fused to reporter genes.

- Characterize sensor dynamic range, specificity, and response curve [41].

- Circuit Assembly:

- Connect sensor output to actuator controlling pathway expression.

- Implement appropriate control logic (positive/negative regulation).

- Include selection markers and genomic integration elements.

- System Characterization:

- Challenge with varying metabolite concentrations in controlled culturing.

- Measure response function and hysteresis if applicable.

- Quantify response time from metabolite addition to output detection.

- Population Analysis:

- Use flow cytometry to assess cell-to-cell variability.

- Implement strategies to reduce heterogeneity if needed (e.g., positive feedback loops).

- Fermentation Testing:

- Evaluate performance in bioreactor conditions.

- Compare with constitutive and two-stage systems.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If sensor cross-talk occurs, implement insulation strategies (insulator parts, orthogonal regulators).

- If response function is suboptimal, use promoter engineering to tune input-output relationship [43] [41].

Visualization of Dynamic Control Strategies

Two-Stage Fermentation Control Logic

Title: Two-stage fermentation control logic for growth-production decoupling.

Autonomous Dynamic Control Circuit

Title: Autonomous dynamic control circuit with feedback regulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dynamic Metabolic Control

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|