Solving the Puzzle: A Comprehensive Guide to Troubleshooting Host Context Problems in Heterologous Expression

Heterologous expression is a cornerstone of biotechnology for producing therapeutics, enzymes, and for natural product discovery.

Solving the Puzzle: A Comprehensive Guide to Troubleshooting Host Context Problems in Heterologous Expression

Abstract

Heterologous expression is a cornerstone of biotechnology for producing therapeutics, enzymes, and for natural product discovery. However, success is frequently hampered by host context problems, where the foreign genetic material fails to function optimally in the new cellular environment. This article provides a systematic, intent-driven guide for researchers and scientists navigating these challenges. It covers the foundational principles of host selection, advanced methodological platforms, targeted troubleshooting strategies for common issues like low protein yield and incorrect folding, and validation techniques to confirm functional success. By integrating the latest research and platform technologies, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to diagnose, overcome, and prevent host context barriers, thereby accelerating bioproduction and drug development pipelines.

Understanding the Host Environment: Why Context is King in Heterologous Expression

Heterologous expression is a fundamental technique in biotechnology and drug development, involving the expression of a gene or gene fragment in a host organism that does not naturally possess it [1]. The success of this process is profoundly influenced by the host context—the specific biological, genetic, and environmental conditions of the chosen expression system. Selecting an inappropriate host or failing to account for its unique context is a primary cause of experimental failure, leading to issues such as low protein yield, improper folding, or a complete lack of expression. This guide is designed to help researchers systematically troubleshoot and resolve these common host context challenges.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: What are the most critical host-related factors to consider before starting a heterologous expression experiment?

The most critical factors are the origin of your gene of interest and the native capabilities of your host. Prokaryotic systems like E. coli are simple and cost-effective but often lack the machinery for essential post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation) that are required for the function of many eukaryotic proteins [1]. Furthermore, the codon usage of your gene must be compatible with the host's tRNA pool; a significant mismatch can lead to translation errors or premature termination [2].

FAQ: My protein is expressed in the host but is insoluble and forms inclusion bodies. What should I do?

This is a common issue, particularly when expressing proteins in large amounts in E. coli [1]. You can pursue several strategies:

- Reduce Expression Temperature: Shifting the growth temperature to 18-25°C can slow down translation, allowing more time for proper protein folding.

- Switch Host Systems: Consider moving to a eukaryotic host like yeast (e.g., P. pastoris) or a baculovirus-insect cell system, which offer better folding machinery and post-translational modifications [1].

- Use Solubility Enhancement Tags: Fuse your protein to tags like Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) or GST, which can improve solubility and serve as a purification handle.

FAQ: I suspect codon bias is causing low expression yields. How can I confirm and fix this?

You can confirm this by using software tools to analyze the Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) of your gene sequence against the host's highly expressed genes. A low CAI indicates poor adaptation [2]. To resolve this, consider gene synthesis to design a "typical gene" where the codon usage is optimized to resemble that of the host's native, highly expressed genes, thereby improving translation efficiency [2].

FAQ: How do I choose between a prokaryotic and eukaryotic host system for my membrane protein?

For membrane proteins, eukaryotic hosts are generally more effective [1]. While E. coli is a popular default host, it lacks the complex lipid composition of eukaryotic membranes and the sophisticated machinery for inserting and folding multi-domain membrane proteins. Mammalian cells, while more costly and slower-growing, provide the most native-like environment for human membrane proteins. Baculovirus-infected insect cells offer a powerful compromise, providing many eukaryotic features with higher yields than mammalian systems [1].

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosing Host Context Issues

Protocol 1: Rapid Assessment of Protein Solubility

Purpose: To quickly determine if your heterologously expressed protein is soluble or has formed inclusion bodies.

Method:

- Harvest and Lyse: Harvest the host cells via centrifugation. Resuspend the cell pellet in a suitable lysis buffer (e.g., containing lysozyme for bacterial cells) and lyse using sonication or a homogenizer.

- Fractionate: Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., 12,000-15,000 x g for 20-30 minutes at 4°C). This separates the soluble fraction (supernatant) from the insoluble fraction (pellet).

- Analyze: Resuspend the insoluble pellet in the same volume of buffer as the supernatant. Analyze equal volumes of the total lysate, soluble fraction, and insoluble fraction by SDS-PAGE.

- Interpretation: If your protein is primarily in the pellet fraction, it has formed inclusion bodies and you should implement solubility enhancement strategies.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Host System Performance Using a Matrix-Based Approach

Purpose: To systematically compare the effectiveness of multiple heterologous hosts for expressing a specific biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC).

Method:

- Host Selection: Select a panel of well-characterized and engineered host strains. A modern approach might include a newly developed high-performance chassis like the Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain, alongside standard hosts like S. coelicolor M1152 and S. lividans TK24 [3].

- Strain Engineering: Engineer each host strain to express the same target BGC using consistent genetic constructs and integration methods (e.g., conjugation or transformation).

- Fermentation and Metabolite Analysis: Grow all engineered strains under standardized fermentation conditions. Harvest and extract metabolites.

- Comparative Analysis: Use analytical methods like LC-MS to detect and quantify the target natural product. Develop a scoring matrix involving multiple parameters (e.g., production yield, growth consistency, sporulation rate) to objectively compare host performance [3].

Table 1: Example Performance Matrix for Streptomyces Host Strains Expressing a Polyketide BGC

| Host Strain | Relative Yield (%) | Growth Robustness | Number of BGCs Successfully Expressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH | 100 | High | 4 out of 4 |

| Streptomyces sp. A4420 WT | 60-80 | High | 3 out of 4 |

| S. coelicolor M1152 | 40-60 | Moderate | 2 out of 4 |

| S. lividans TK24 | 20-40 | Moderate | 2 out of 4 |

| S. albus J1074 | 10-30 | Moderate | 1 out of 4 |

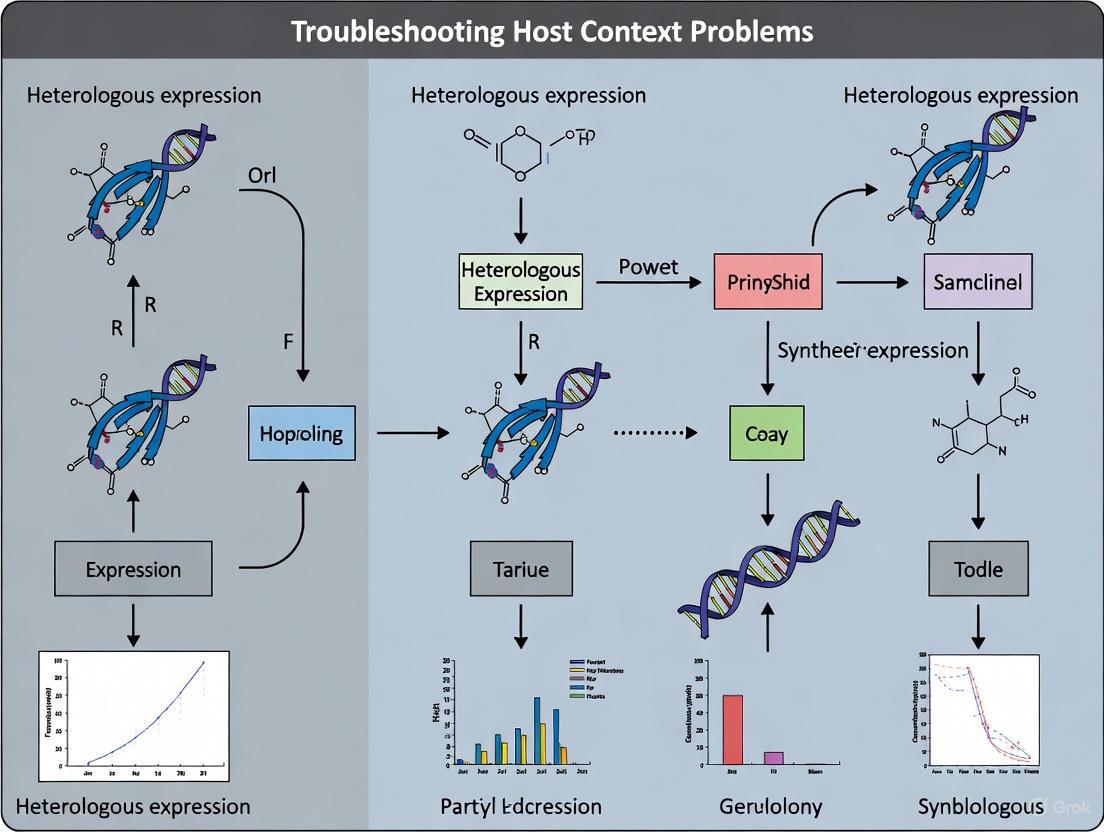

Visualizing the Host Selection and Troubleshooting Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting a host system and troubleshooting common context-related failures.

Host Context Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Heterologous Expression Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Host Systems |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | A workhorse strain for high-level protein expression with T7 RNA polymerase under IPTG control. | Escherichia coli |

| Bacillus subtilis | A Gram-positive host; does not produce endotoxins and can secrete proteins directly into the culture medium [1]. | Bacillus subtilis |

| Pichia pastoris | A methylotrophic yeast for high-density fermentation, capable of strong secretion and some post-translational modifications [1]. | Komagataella phaffii |

| Lentiviral Vectors | For stable integration and long-term expression of genes in mammalian cells, including non-dividing cells [1]. | Mammalian Cells (e.g., HEK293) |

| Codon-Optimized Genes | Synthetic genes designed to match the codon usage frequency of the host organism to maximize translation efficiency [2]. | All Systems |

| Lipofection Reagents | Form lipid-based nanoparticles that encapsulate DNA and fuse with cell membranes for efficient delivery [1]. | Mammalian Cells |

| Electroporation Apparatus | Uses a high-voltage pulse to create transient pores in cell membranes, allowing DNA to enter the cell [1]. | Bacteria, Yeast, Mammalian Cells |

| Hsd17B13-IN-67 | Hsd17B13-IN-67|HSD17B13 Inhibitor|For Research Use | Hsd17B13-IN-67 is a potent inhibitor of the lipid droplet-associated enzyme HSD17B13. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| BTL peptide | BTL peptide, MF:C67H114N18O24, MW:1555.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical factors to consider when selecting a host for heterologous protein expression? The most critical factors include the origin and properties of the target protein (e.g., presence of disulfide bonds, post-translational modification requirements, and codon usage), the intended application (e.g., need for solubility vs. simple production for antibody generation), and the inherent strengths and limitations of the host system itself (e.g., secretion capability, growth speed, and cost) [4]. Matching the protein's native environment to the host's capabilities is paramount for success.

Q2: Our team is expressing a eukaryotic protein in E. coli, but the protein is consistently deposited in inclusion bodies. What strategies can we employ to obtain soluble, functional protein? This is a common challenge. You can pursue several strategies [4]:

- Modify Expression Conditions: Lowering the induction temperature (e.g., to 25-30°C or even as low as 10°C) and using a lower concentration of inducer can slow down protein synthesis, allowing more time for proper folding.

- Use Fusion Tags: Fusing your target protein to a solubility-enhancing tag, such as Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) or glutathione S-transferase (GST), can improve solubility and proper folding.

- Co-express Chaperones: Co-expressing molecular chaperones (e.g., GroEL-GroES, DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE) in the same E. coli strain can assist in the folding of the heterologous protein.

- Switch the Host Strain: Some specialized E. coli strains are engineered for more robust disulfide bond formation (e.g., Origami strains) or possess chaperone plasmids.

Q3: We are experiencing protein truncation, especially in multi-domain cellulases, when using bacterial expression systems. What is the likely cause and how can it be addressed? Protein truncation, particularly the degradation of linker sequences in multi-domain enzymes like cellulases, is a known issue in E. coli [4]. This is often due to proteolytic degradation. Strategies to overcome this include [4]:

- Using E. coli strains deficient in specific proteases (e.g., ompT, lon proteases).

- Expressing the protein as a fusion construct that protects vulnerable regions.

- Switching to a different host system, such as a eukaryotic yeast, which may offer a more compatible proteolytic environment.

Q4: How can we improve the secretion yield of a recombinant protein from a gram-negative bacterial host like E. coli? Enhancing secretion in E. coli is challenging due to its double membrane. Effective methods include [4]:

- Signal Peptide Engineering: Testing different signal peptides compatible with the Sec or Tat secretion pathways.

- Fusion Proteins: Utilizing fusion partners like OsmY, which can facilitate transport across the outer membrane.

- Co-expression of Transport Machinery: Co-expressing proteins that form part of the host's secretion apparatus.

- Chemical Treatment: Mild periplasmic release techniques using EDTA or hyperosmotic shock can improve recovery of secreted proteins.

Q5: When is it advisable to choose a eukaryotic host system like yeast over a prokaryotic one like E. coli? A eukaryotic host like yeast (S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris) is highly advisable when the target protein [4]:

- Requires post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation, disulfide bond formation) for stability and activity.

- Is from a eukaryotic origin and is typically secreted.

- Has proven difficult to fold correctly in a prokaryotic cytoplasm.

- Needs to be expressed at a scale suitable for industrial applications, leveraging yeast's high-density fermentation capabilities.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low or No Protein Expression

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Toxic Protein to Host | Monitor host cell growth pre- and post-induction. Use viability staining. | Use a tighter, inducible promoter (e.g., T7/lac). Decrease induction temperature and IPTG concentration. Use an auto-inducible medium [4]. |

| Inefficient Transcription/Translation | Perform RT-qPCR to check mRNA levels. Check for rare codons in the gene sequence. | Optimize the promoter strength. Use a codon-optimized gene sequence. Use a host strain engineered with plasmids for rare tRNAs [4]. |

| Plasmid Instability | Check plasmid copy number and integrity pre- and post-culture. | Use a different antibiotic selection marker. Use a high-stability origin of replication. Include a post-segregational killing system in the plasmid. |

Problem 2: Protein Insolubility (Inclusion Body Formation)

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Protein Synthesis | Analyze solubility fractions (supernatant vs. pellet) via SDS-PAGE after different induction conditions. | Reduce growth temperature (e.g., to 18-25°C). Reduce inducer concentration. Use a weaker promoter [4]. |

| Lack of Folding Assistance | Compare solubility when co-expressing chaperones. | Co-express chaperone plasmids (e.g., GroEL/GroES, TF). Use strains with enhanced disulfide bond formation (e.g., Origami). Include a solubility-enhancing fusion tag (MBP, SUMO, GST) [4]. |

| Unfavorable Cytoplasmic Environment | Test expression in different cellular compartments (e.g., periplasm) using appropriate signal peptides. | Target the protein for secretion to the periplasm. Change the host species (e.g., to a yeast system). Optimize the lysis buffer conditions (pH, salt) [4]. |

Problem 3: Poor Biological Activity despite High Expression

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Improper Folding | Compare the oligomeric state with a native standard via Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC). Check for correct disulfide bonds. | Refactor the gene to express only the functional domain. Co-express foldases like disulfide isomerase (DsbC). Switch to a host system that provides a more oxidizing environment (e.g., yeast, insect cells). |

| Lack of Essential Post-Translational Modifications | Analyze glycosylation status via enzymatic digestion or mass spectrometry. | Switch to a eukaryotic host (yeast, insect, or mammalian cells) capable of the required PTMs. Use a glyco-engineered yeast strain for human-like glycosylation. |

| Incorrect Protein Localization | Fractionate the cell (cytoplasm, membrane, periplasm) and assay for activity in each fraction. | Use a stronger or more compatible signal peptide for efficient secretion. Target the protein to a different cellular compartment. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Small-Scale Expression Test for Solubility Screening This protocol is designed to quickly identify the best expression conditions for solubility in E. coli.

- Transformation: Transform the expression plasmid into a suitable E. coli strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)).

- Inoculation: Pick a single colony into 5 mL of LB medium with antibiotic. Grow overnight at 37°C, 220 rpm.

- Dilution: Dilute the overnight culture 1:100 into fresh, pre-warmed medium (in triplicate for each condition). Incubate at 37°C, 220 rpm.

- Induction: When OD600 reaches 0.6-0.8, induce expression by adding IPTG to a final concentration (e.g., 0.1 mM, 0.5 mM, 1.0 mM). Simultaneously, shift the incubation temperature for the different cultures (e.g., 37°C, 25°C, 18°C).

- Harvesting: Harvest cells by centrifugation (4,000 x g, 20 min, 4°C) 4-16 hours post-induction.

- Lysis & Fractionation: Resuspend pellets in lysis buffer. Lyse cells by sonication or lysozyme treatment. Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (15,000 x g, 30 min, 4°C) to separate the soluble (supernatant) and insoluble (pellet) fractions.

- Analysis: Analyze both fractions by SDS-PAGE to assess total expression and solubility.

Protocol 2: Assessing Secretion Efficiency in Yeast This protocol measures how effectively a recombinant protein is secreted into the culture supernatant by S. cerevisiae or P. pastoris.

- Culture Inoculation: Inoculate a single colony of the transformed yeast into a small volume of selective medium. Grow overnight at 30°C, 220 rpm.

- Induction & Scaling: Dilute the culture into fresh, induction-specific medium (e.g., methanol for P. pastoris) in a baffled flask. Continue incubation.

- Sampling: At regular intervals (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours), aseptically remove 1 mL of culture.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the sample immediately (13,000 x g, 10 min, 4°C). Carefully transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

- Concentration (Optional): If the protein concentration is low, concentrate the supernatant using a centrifugal filter device.

- Analysis: Analyze the concentrated supernatant and the cell pellet (for intracellular protein) by SDS-PAGE and Western Blot or activity assay to determine the secretion efficiency.

Host Selection and Troubleshooting Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision-making process for selecting an expression host and addressing common failures.

Troubleshooting Protein Insolubility

This diagram visualizes the primary strategies for resolving the common issue of inclusion body formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Codon-Optimized Genes | Synthetic genes designed with host-preferred codons to maximize translation efficiency and yield [4]. | Essential for overcoming translational bottlenecks, especially when expressing genes from evolutionarily distant organisms. |

| Solubility-Enhancing Fusion Tags | Polypeptides fused to the target protein to improve its solubility and proper folding in the cytoplasm [4]. | Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP), Glutathione S-transferase (GST), Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO). Can also aid in purification. |

| Molecular Chaperone Plasmids | Plasmids encoding chaperone proteins that are co-expressed to assist in the folding of the heterologous protein, reducing aggregation [4]. | Plasmids for GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE, and TF in E. coli. |

| Specialized E. coli Strains | Engineered strains that address specific expression challenges like disulfide bond formation, membrane protein expression, or protease deficiency [4]. | Origami (disulfide bonds), C41/C43 (membrane proteins), BL21(DE3) pLysS (tight control, protease reduction). |

| Inducible Promoters | DNA sequences that control the initiation of transcription and can be "turned on" by a chemical or environmental signal, allowing control over expression timing [4]. | T7 lac, araBAD (in E. coli); AOX1 (in P. pastoris). Tight control can prevent toxicity from premature expression. |

| Signal Peptides | Short peptide sequences fused to the N-terminus of a protein to direct its transport through the secretory pathway [4]. | PelB, OmpA (for bacterial periplasm); α-factor (for yeast secretion). Choice of signal peptide critically impacts secretion efficiency. |

| Vitexin caffeate | Vitexin Caffeate|High-Purity Reference Standard | Vitexin caffeate is a flavonoid derivative for research use only (RUO). Explore its applications in oncology, neuroscience, and biochemistry. Not for human consumption. |

| Muc5AC-3 | Muc5AC-3 Glycopeptide|MUC5AC Research Reagent | Muc5AC-3 is a synthetic, O-glycosylated 16-amino acid glycopeptide for mucin research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Selecting an appropriate host organism is a critical first step in the successful heterologous expression of recombinant proteins. The choice fundamentally influences every subsequent aspect of the experimental workflow, from vector design to protein purification. Within the context of troubleshooting host-related issues, understanding the inherent strengths and limitations of the most common platforms is paramount. This guide provides a systematic comparison of three major workhorse hosts: Escherichia coli (a prokaryotic bacterium), Yeasts (single-celled eukaryotes, e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Komagataella phaffii), and Actinomycetes (Gram-positive bacteria, e.g., Streptomyces spp.). Our goal is to equip researchers with the knowledge to make an informed initial selection and to effectively troubleshoot the predictable challenges associated with each system.

Host Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of E. coli, yeast, and actinomycetes to aid in initial host selection.

| Feature | E. coli | Yeast | Actinomycetes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism Type | Gram-negative bacterium | Eukaryote, fungus | Gram-positive bacterium (High G+C) |

| Typical Yield | High (often >100 mg/L) [5] | Variable; can be high with optimized systems [6] | Variable; reported up to ~400 mg/L for some proteins in Streptomyces [7] |

| Growth Speed | Very rapid (doubling ~20 min) | Moderate (doubling ~90 min) | Slow (doubling can be several hours) [7] |

| Genetic Tools | Extensive, well-established, and versatile [5] | Extensive for S. cerevisiae; developing for non-conventional yeasts [6] | Available but less extensive than E. coli; often strain-specific [7] [8] |

| Cost of Cultivation | Low | Low to Moderate | Low to Moderate |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Limited; lacks eukaryotic glycosylation machinery [6] | Capable of many, including glycosylation (but differs from mammalian patterns) [6] | Capable of some modifications; good for disulfide bond formation and bacterial-style modifications [7] |

| Secretion Efficiency | Can target to periplasm; true secretion is rare [9] | Naturally proficient at secreting proteins [6] | Highly efficient secretion systems for many species [7] |

| Ideal Use Case | High-yield production of non-glycosylated, prokaryotic proteins; rapid screening [9] [5] | Production of eukaryotic proteins requiring folding, disulfide bonds, or basic glycosylation; secreted production [6] | Production of complex bacterial natural products (e.g., polyketides), secreted enzymes, and proteins from high G+C bacteria [7] [8] |

Troubleshooting Common Host-Specific Problems

E. coli: The Workhorse with Folding and Toxicity Challenges

Problem 1: The target protein is expressed but forms insoluble inclusion bodies.

- Question: My protein is expressed at a high level according to SDS-PAGE, but it's all in the pellet fraction after centrifugation. How can I recover functional, soluble protein?

- Answer: This is a classic issue in E. coli, often caused by rapid expression that overwhelms the host's folding machinery [10] [5].

- Slow things down: Reduce the induction temperature (e.g., to 18-25°C) and/or lower the concentration of the inducer (e.g., IPTG) [10]. This slows the rate of synthesis, allowing the chaperone systems more time to fold the protein correctly.

- Co-express chaperones: Co-express plasmid systems that overproduce molecular chaperones like GroEL/GroES or DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE. Commercially available chaperone plasmid sets (e.g., from Takara) can be tested [10].

- Use fusion tags: Clone your gene as a fusion with a solubility-enhancing partner such as Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP), Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST), or Thioredoxin (Trx) [10] [9]. These can improve solubility and also aid in purification.

- Target to the periplasm: Use a signal sequence (e.g., pelB, ompA) to direct the protein to the oxidizing environment of the periplasm, which can facilitate proper disulfide bond formation [9].

Problem 2: No expression is detected, or the expressed protein is toxic to the host cells.

- Question: My cultures fail to grow after induction, or growth is severely stunted, and I cannot detect my protein. What could be happening?

- Answer: This is often a sign of protein toxicity, where the heterologous protein interferes with essential host processes [5].

- Use a tighter promoter: Switch to a more tightly regulated expression system. The pET system with T7 RNA polymerase is common, but basal expression can be problematic. Use strains like BL21(DE3)pLysS, which expresses T7 lysozyme to inhibit basal transcription [9] [5].

- Try different E. coli strains: Specialized strains like C41(DE3) and C43(DE3) were evolved from BL21(DE3) to better tolerate the expression of toxic membrane proteins [5].

- Optimize codon usage: Check the gene sequence for codons that are rare in E. coli. These can cause ribosomal stalling, truncation, and toxicity. Use gene synthesis to optimize the codon usage for E. coli or use strains like Rosetta that supply tRNAs for rare codons [10] [5].

Yeast: Balancing Eukaryotic Complexity with Simplicity

Problem 1: Protein expression levels are low despite a good construct.

- Question: I have cloned my gene into a yeast expression vector, but the yield is disappointingly low. What strategies can boost expression?

- Answer: Low yields in yeast can stem from promoter strength, plasmid stability, or the gene sequence itself.

- Choose a stronger promoter: Do not rely solely on a constitutive promoter like ADH1. For high-level expression, use strong inducible promoters such as the alcohol oxidase 1 promoter (AOX1) in K. phaffii (induced by methanol) or the galactose-inducible (GAL1/GAL10) promoters in S. cerevisiae [6] [9].

- Select the right vector type: Ensure you are using an appropriate plasmid. For high-copy, stable maintenance, use Yeast Episomal Plasmids (YEp) based on the 2-micron circle. For single-copy stability, use Yeast Centromere Plasmids (YCp) [11].

- Optimize the secretion signal: If secreting the protein, the choice of signal peptide is critical. Common choices include the α-mating factor pre-pro leader. Inefficient cleavage or secretion can limit yields. Testing different signal sequences can be highly beneficial [6].

Problem 2: The purified protein has incorrect or heterogeneous glycosylation.

- Question: My protein is expressed and secreted, but the glycosylation pattern is non-human or inconsistent, potentially affecting its activity and therapeutic applicability.

- Answer: This is a well-known limitation of yeast systems, as they produce high-mannose type glycosylation, unlike the complex glycosylation in mammalian cells [6].

- Use glyco-engineered yeast strains: A major advancement has been the creation of engineered yeast strains (e.g., in K. phaffii) where the native glycosylation pathway has been modified to produce human-like, complex N-glycans [6].

- Consider a different yeast host: Some non-conventional yeasts, like Kluyveromyces lactis, may have glycosylation patterns that are more suitable for your specific protein than S. cerevisiae [6].

Actinomycetes: Harnessing a Powerful but Finicky Host

Problem 1: Getting DNA into the host and achieving expression is inefficient.

- Question: The genetic tools for my actinomycete host seem limited compared to E. coli. How can I improve transformation and ensure my gene is expressed?

- Answer: Actinomycetes can have tough cell walls and restriction-modification systems that hinder transformation.

- Use a dedicated shuttle vector: Employ E. coli-Actinomycete shuttle vectors that contain a replicon functional in the chosen host (e.g., derived from SCP2, pIJ101) and an E. coli origin (like ColE1) for easy cloning [7] [8].

- Employ a strong, inducible promoter: Don't assume native promoters will be strong. Use well-characterized, heterologous inducible promoters such as the thiostrepton-inducible

tipApromoter or the ε-caprolactam-induciblePnitApromoter from Rhodococcus, which has been shown to drive hyper-expression in some Streptomyces [12] [7]. - Use a restriction-deficient strain: When possible, use strains like Streptomyces lividans, which lacks certain restriction systems, making it more amenable to genetic manipulation with foreign DNA [7].

Problem 2: I am expressing a biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) for a natural product, but no product is detected.

- Question: I have successfully cloned a large BGC into an actinomycete host, but the expected secondary metabolite is not being produced. How can I activate it?

- Answer: This is common with heterologous expression of BGCs, as the native regulatory context is often lost.

- Ensure optimal expression of pathway regulators: Many BGCs contain pathway-specific regulatory genes (e.g., activators). Replace the native promoter of these regulatory genes with a strong, constitutive heterologous promoter (e.g.,

ermE*) to ensure they are adequately expressed in the new host. This has been shown to increase product yield by up to 100-fold [12]. - Choose a "clean" heterologous host: Use a host with a minimal background of secondary metabolites, such as Streptomyces albus, to simplify detection and avoid interference from host-derived compounds [8].

- Utilize advanced cloning techniques: For large BGCs (>50 kb), consider using specialized systems like Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) in yeast, BAC vectors, or Integrase-Mediated Recombination (IR) to ensure intact, stable cloning of the entire cluster [13] [8].

- Ensure optimal expression of pathway regulators: Many BGCs contain pathway-specific regulatory genes (e.g., activators). Replace the native promoter of these regulatory genes with a strong, constitutive heterologous promoter (e.g.,

Essential Reagents and Research Tools

The table below lists key reagents and materials referenced in the troubleshooting guides above.

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| pET Expression System | T7 RNA polymerase-driven, high-level expression in E. coli [9] [5] | Standard, high-yield cytoplasmic protein production. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Sets | Co-expression of folding assistants to improve solubility [10] | Rescuing proteins that form inclusion bodies. |

| Rosetta / Codon Plus E. coli | Supply tRNAs for rare codons not commonly found in E. coli [10] [5] | Expressing genes from eukaryotic or high G+C organisms. |

| pGEX / pMAL Vectors | Fusion protein systems for solubility and affinity purification (GST, MBP) [10] [9] | One-step purification and solubility enhancement. |

| pPIC Vectors (K. phaffii) | Methanol-inducible expression and secretion using the AOX1 promoter [6] [9] | High-level secreted expression of eukaryotic proteins. |

| TAR Cloning System | In vivo assembly of large DNA fragments in yeast [13] [8] | Cloning entire biosynthetic gene clusters (>50 kb). |

| ermE* Promoter | Strong, constitutive promoter for use in actinomycetes [12] | Driving high-level expression of activator genes or target enzymes. |

| tipA Promoter | Thiostrepton-inducible promoter for Streptomyces [12] [7] | Tightly regulated, inducible expression in actinomycetes. |

Experimental Workflow for Host Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical decision-making process for selecting an expression host and troubleshooting initial failures, based on the protein's characteristics and project goals.

There is no single "best" host for heterologous expression. The optimal choice is a strategic balance between the protein's inherent properties and the project's requirements for yield, authenticity, and timeline. E. coli remains the king of speed and yield for simpler proteins, while yeast offers a superb balance of eukaryotic functionality and ease of use. Actinomycetes, though more specialized, are unparalleled for expressing complex bacterial natural products. A methodical approach to host selection, informed by the common pitfalls and solutions outlined in this guide, will significantly increase the likelihood of successful recombinant protein production. When one system fails, the structured troubleshooting steps provided here, combined with the willingness to try an alternative host, often pave the path to success.

The shift towards Streptomyces and fungal chassis for heterologous expression represents a pivotal evolution in biotechnology, moving beyond the traditional E. coli model to access complex natural products and proteins. This transition is driven by the need to express large, sophisticated biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) and recombinant proteins that require specialized cellular machinery, post-translational modifications, and specific metabolic precursors. However, working with these complex hosts introduces unique technical challenges. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate the specific host-context problems encountered when utilizing Streptomyces and fungal systems, thereby enabling more efficient and successful heterologous expression experiments.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Host-Specific Challenges

This section addresses the most frequent technical obstacles and their evidence-based solutions, as identified in recent literature.

Streptomyces Chassis Troubleshooting

Table: Troubleshooting Streptomyces Heterologous Expression

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Research Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low or no product yield | Native BGCs competing for precursors and resources. [3] | Delete multiple native polyketide BGCs to create a metabolically simplified chassis strain. [3] | Engineered Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain with 9 deleted native BGCs successfully expressed 4 distinct polyketides where other hosts failed. [3] |

| Low BGC expression | Inefficient transcription/translation; lack of optimal regulatory elements. | Introduce point mutations in ribosomal proteins (e.g., rpsL) and RNA polymerase (e.g., rpoB) to globally enhance expression. [3] [14] | S. coelicolor M1152 (with rpoB mutation) and M1154 (with rpoB and rpsL mutations) showed 20-40-fold yield increases. [3] |

| Inefficient DNA transfer & integration | Instability of cloned DNA in E. coli; limited genomic integration sites in host. [15] | Use improved E. coli donor strains (e.g., Micro-HEP platform) and chassis with multiple orthogonal recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) sites. [15] | The Micro-HEP system enabled stable transfer and multi-copy integration of BGCs, boosting xiamenmycin production. [15] |

Fungal Chassis Troubleshooting

Table: Troubleshooting Fungal Heterologous Expression

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Research Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal protein secretion | Weak promoter, inefficient signal peptide, or suboptimal 5'UTR. [16] | Systematically screen and combine strong constitutive promoters (e.g., Ppdc), engineered 5'UTRs (e.g., NCA-7d), and efficient signal peptides. [16] | In M. thermophila, the combination of Ppdc, NCA-7d 5'UTR, and native signal peptide increased laccase activity to over 1700 U/L. [16] |

| Unwanted pelleted morphology | Hyphal coagulation and aggregation leading to diffusion limitations and hypoxia. [17] | Genetically engineer strains to control morphology by regulating genes involved in hyphal growth and coagulation (e.g., pkh2). [17] | A library of A. niger strains with conditional expression of morphology-associated genes allowed titratable control of pellet formation. [17] |

| Proteolytic degradation of product | High native extracellular protease activity. | Use host strains with deletions of major extracellular protease genes (e.g., ΔMtalp1 in M. thermophila). [16] | The ΔMtalp1 mutant of M. thermophila was used as a host to prevent potential hydrolysis of the recombinant laccase. [16] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I consider a Streptomyces host over E. coli for expressing natural product BGCs?

Streptomyces offers several critical advantages for expressing complex BGCs, particularly those from actinomycetes. Its high GC-content genome is more compatible with GC-rich actinomycete DNA, reducing the need for codon optimization. [18] More importantly, Streptomyces provides a specialized metabolic background with the necessary precursors (e.g., acyl-CoAs), post-translational modification enzymes, and self-resistance mechanisms that are often essential for the functional expression of large, modular enzymes like polyketide synthases (PKSs) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs). [18] Its efficient protein secretion system also facilitates the production of correctly folded, disulfide-bonded proteins. [18]

Q2: What are the key genetic features of an optimized Streptomyces chassis strain?

A modern, high-performance Streptomyces chassis typically incorporates several key genetic modifications:

- Deletion of Native BGCs: Removal of multiple endogenous BGCs reduces metabolic burden and background interference, simplifying the detection of heterologous products. [3] [15]

- Introduction of Regulatory Mutations: Beneficial mutations in genes like rpoB (RNA polymerase) and rpsL (ribosomal protein S12) globally enhance transcription and translation of heterologous pathways. [3] [14]

- Engineered Attachment Sites: Incorporation of multiple, orthogonal integration sites (e.g., attB sites for ΦC31, loxP, vox, rox) allows for stable, multi-copy integration of BGCs. [15]

Q3: How can I control fungal morphology in submerged fermentations, and why is it important?

Fungal morphology (dispersed mycelia vs. pellets) profoundly impacts product titers and bioreactor rheology. Pelleted growth can cause internal hypoxia, limiting growth and production, while dispersed growth increases medium viscosity. [17] Control strategies include:

- Abiotic Parameters: Adjusting inoculum concentration, stir speed, pH, and adding mineral ions or surfactants. [17]

- Genetic Engineering: Creating chassis strains with defined morphology by manipulating genes involved in hyphal growth, branching, and coagulation. For example, conditional expression of the kinase-encoding gene pkh2 in A. niger can decouple fitness from pellet morphology. [17]

Q4: What strategies can enhance the yield of recombinant proteins in fungal systems?

Maximizing protein yield in fungi requires a multi-faceted approach focusing on expression and secretion:

- Strong Promoters: Use strong, constitutive promoters like Ppdc (pyruvate decarboxylase) or Ptef1 (elongation factor 1-alpha). [16]

- Optimized Leaders: Employ engineered 5' untranslated regions (5'UTRs) that enhance mRNA stability and translation efficiency. [16]

- Efficient Secretion Signals: Utilize native signal peptides proven to drive high-level secretion for your target protein or host. [16]

- Protease Reduction: Use host strains with deletions of major extracellular proteases to minimize product degradation. [16]

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Engineering a High-Yield Streptomyces Chassis

This protocol outlines the creation of a metabolically optimized host, based on the development of the Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain and the S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 strain. [3] [15]

Key Reagents:

- Host Strain: A well-characterized Streptomyces species (e.g., S. coelicolor, S. lividans, or Streptomyces sp. A4420).

- Vector System: Suicide vectors for gene deletion (e.g., pKC1132-based vectors) and integrating vectors for introducing attB sites.

- Culture Media: Suitable liquid and solid media for normal growth and sporulation (e.g., SFM, ISP2).

Methodology:

- Genome Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence the parental strain and use bioinformatics tools like antiSMASH to identify all native BGCs. [3]

- Design Deletion Strategy: Prioritize the deletion of large, metabolically costly BGCs, particularly those that interfere with analytical detection (e.g., pigment producers).

- Sequential BGC Deletion:

- For each target BGC, construct a deletion vector containing ~2 kb homology arms flanking a selectable marker (e.g., apramycin resistance).

- Introduce the vector into the host via conjugation from E. coli and select for single-crossover integrants.

- Allow for a second crossover event and screen for double-crossover mutants that have lost the vector backbone but retain the deleted BGC.

- Verify each deletion by PCR.

- Introduce Beneficial Mutations: Introduce point mutations like rpoB (rifampicin resistance) or rpsL (streptomycin resistance) via similar homologous recombination methods to globally enhance expression. [3]

- Engineer Genomic Integration Sites: Introduce orthogonal attachment sites (e.g., loxP, vox, rox) into "safe havens" in the genome using CRISPR-Cas9 or other genome editing tools to enable future multi-copy, RMCE-based integration of heterologous BGCs. [15]

Protocol: Optimizing Protein Secretion in a Fungal Host

This protocol, adapted from work in Myceliophthora thermophila, describes a systematic pipeline for maximizing recombinant protein secretion. [16]

Key Reagents:

- Reporter Gene: A gene encoding an easily assayed extracellular enzyme, such as a laccase (lcc1).

- Expression Elements: A library of strong constitutive promoters (e.g., Ptef1, Ppdc, Phsp30), various 5'UTRs, and different signal peptides.

- Host Strain: A protease-deficient strain (e.g., ΔMtalp1) is recommended.

Methodology:

- Promoter Screening:

- Construct expression cassettes where your reporter gene is placed under the control of different candidate promoters.

- Transform the cassettes into your fungal host and isolate multiple transformants for each construct.

- Measure the enzymatic activity in the culture supernatant of each transformant to identify the strongest promoter.

- 5'UTR Engineering:

- Fuse the best-performing promoter with a panel of different 5'UTR sequences upstream of the reporter gene.

- Repeat the transformation and activity assay. The 5'UTR can dramatically influence mRNA stability and translation efficiency.

- Signal Peptide Testing:

- Fuse the optimal promoter-5'UTR combination with the coding sequences for different signal peptides (both native and heterologous).

- Compare the levels of secreted protein activity to identify the most efficient signal peptide for your target protein.

- Validation and Scale-Up: Ferment the best-performing engineered strain in a bioreactor to validate high-level production under controlled conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Advanced Heterologous Expression

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Micro-HEP Platform [15] | A bifunctional E. coli system for stable modification and conjugation transfer of large BGCs into Streptomyces. | Addresses DNA instability in standard E. coli donors (e.g., ET12567/pUZ8002) during cloning and conjugation. [15] |

| Orthogonal RMCE Systems [15] | Suite of tyrosine recombinase systems (Cre-loxP, Vika-vox, Dre-rox) for precise, multi-copy, marker-free genomic integration. | Enables simultaneous integration of multiple BGC copies at dedicated genomic loci in S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023, boosting product yield. [15] |

| Morphology-Engineered Fungal Library [17] | A collection of fungal strains (e.g., A. niger) with conditional expression of morphology genes for controllable growth forms. | Allows researchers to rapidly screen for the optimal macromorphology (pellet vs. dispersed) for their specific product. [17] |

| Laccase Gene Reporting System [16] | A rapid screening method using extracellular laccase activity to identify optimal expression elements. | Used in M. thermophila to efficiently screen promoters, 5'UTRs, and signal peptides by visualizing activity on indicator plates. [16] |

| Gpx4/cdk-IN-1 | Gpx4/cdk-IN-1 is a dual GPX4 and CDK inhibitor that induces ferroptosis and cell cycle arrest. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. | |

| TLR8 agonist 6 | TLR8 agonist 6, MF:C19H29N7O2, MW:387.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Streptomyces Chassis Engineering and Expression Workflow

Diagram: Streptomyces Chassis Engineering and Expression Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps for constructing a high-performance Streptomyces chassis and using it for heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), incorporating strategies like BGC deletion and recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE). [3] [15]

Fungal Protein Secretion Optimization Pathway

Diagram: Fungal Protein Secretion Optimization Pathway. This workflow demonstrates the iterative process of enhancing recombinant protein secretion in filamentous fungi by systematically testing and combining optimal genetic elements. [16]

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: What are the major types of barriers in heterologous protein expression? Heterologous protein expression faces a multi-layered challenge. The primary barriers exist at three key regulatory levels:

- Transcriptional Barriers: Inefficiencies in the promoter driving the expression of your gene of interest, or competition from native cellular transcription factors [19].

- Translational Barriers: Issues during the protein synthesis process, including ribosome pausing at rare codons, mRNA instability, and the immense metabolic burden imposed on the host cell's machinery [20] [21].

- Post-Translational Barriers: The failure of the host cell to properly fold, modify, or localize the protein, often leading to destructive protein misfolding and aggregation [22] [23] [24].

Q2: Why is my protein not being expressed, even though the gene is present? This is a classic symptom of a transcriptional barrier. The most common cause is the use of a weak or poorly regulated promoter. Furthermore, even with a strong promoter, native transcription factors can bind to it and either inhibit or enhance its activity in unpredictable ways. For example, in P. pastoris, transcription factors like Loc1p and Msn2p have been identified as inhibitors of the common pGAP promoter [19].

Q3: My mRNA is detected, but the protein yield is low. What could be wrong? This points to a translational barrier. Key factors to investigate include:

- Codon Usage: The presence of rare codons incompatible with the host's tRNA pool can cause ribosome stalling, reducing efficiency and potentially triggering mRNA degradation [20].

- Metabolic Burden: The high energy demand of producing a foreign protein can overwhelm the host, leading to a global downregulation of translation and growth to conserve resources [21].

- mRNA Stability: The lack of a proper 5' cap or poly-A tail, or the action of microRNAs, can lead to rapid degradation of the mRNA before it is fully translated [25].

Q4: My protein is expressed but is insoluble or inactive. How can I fix this? This is a clear indication of post-translational barriers. The cellular machinery is failing to produce a functional protein. Causes include:

- Misfolding and Aggregation: The protein may not be folding into its correct native conformation, causing it to form toxic insoluble aggregates [23] [24].

- Lack of Essential PTMs: The host may lack the enzymes to perform necessary modifications like specific glycosylation patterns or phosphorylation, which are critical for the activity and stability of many eukaryotic proteins [22] [21].

- Saturation of Quality Control: Overexpression can overwhelm the chaperone and proteasome systems, preventing proper folding and degradation of faulty proteins [23] [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Transcriptional Barriers

Symptoms: No mRNA detected, or mRNA levels are low despite confirmed gene integration.

| Step | Investigation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Promoter Strength | Switch to a stronger, well-characterized promoter (e.g., pAOX1 for inducible expression in P. pastoris). Consider a promoter library to find the optimal strength [19]. |

| 2 | Transcription Factor Interference | Use transcriptome analysis and databases like YEASTRACT to identify inhibitory transcription factors. Engineer knockout strains to remove these barriers [19]. |

| 3 | Gene Copy Number | Verify the gene copy number and integration site. Consider using a multi-copy integration strategy if a single copy is insufficient. |

Experimental Protocol: Identifying Inhibitory Transcription Factors

- Strain Comparison: Perform RNA-seq transcriptome analysis on your low-producing strain and a control strain.

- In Silico Prediction: Use the promoter sequence of your expression vector (e.g., pGAP) in a database like YEASTRACT to predict potential transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) [19].

- Target Selection: Cross-reference the transcriptome data with the TFBS prediction. Select transcription factor genes that are significantly differentially expressed.

- Validation: Create knockout and overexpression strains for the candidate transcription factors.

- Assay Activity: Measure the activity of your reporter protein (e.g., xylanase) in the engineered strains. A significant increase in yield upon knockout confirms an inhibitory factor [19].

Guide 2: Diagnosing and Resolving Translational Barriers

Symptoms: mRNA is present, but protein yield is low. Cell growth is severely impaired, indicating high burden.

| Step | Investigation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Codon Optimization | Use gene synthesis to optimize the coding sequence for the host's codon usage bias, paying special attention to the first 10-15 codons [20]. |

| 2 | Ribosome Pausing | Analyze the sequence for known pause-inducing motifs (e.g., poly-proline tracts, specific rare codon clusters) and redesign those regions [20]. |

| 3 | Reduce Metabolic Burden | Use an inducible expression system to separate growth and production phases. Engineer host metabolism to enhance energy and precursor supply [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Ribosome Pausing and Its Impact

- Ribosome Profiling: Perform ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) on your expressing strain. This technique provides a genome-wide snapshot of ribosome positions, revealing where pauses occur [20].

- Sequence Correlation: Correlate ribosome pause sites with specific codon usage or mRNA secondary structures in your gene of interest.

- Codon Replacement: Systematically replace the identified problematic codons with optimal synonyms.

- Validate Improvement: Re-run the ribosome profiling and protein yield assays on the optimized construct to confirm increased translational efficiency and protein production [20].

Guide 3: Diagnosing and Resolving Post-Translational Barriers

Symptoms: Protein is produced but is found in insoluble aggregates (inclusion bodies) or is inactive due to incorrect modification.

| Step | Investigation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aggregation Propensity | Analyze the protein sequence for aggregation-prone regions. Consider targeted mutations to improve solubility. |

| 2 | Chaperone Co-expression | Co-express molecular chaperones (e.g., Hsp70, Hsp90, or trigger factor) to assist with proper folding and prevent aggregation [23] [24]. |

| 3 | Host Selection | If PTMs are incorrect, switch to a more advanced eukaryotic host (e.g., P. pastoris, mammalian cells) that can perform the required modifications [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing and Preventing Protein Aggregation

- Fractionation: Lyse the cells and separate the soluble and insoluble fractions via centrifugation.

- Detection: Run SDS-PAGE and a Western blot on both fractions to determine if your protein is in the soluble fraction or the inclusion body pellet.

- Chaperone Screening: Co-express a library of different chaperone proteins (e.g., Hsp104, Hsp70, Hsp40) in your production strain [23] [24].

- Activity Assay: Re-run the fractionation and blot. Test the soluble fraction for protein activity to confirm that the chaperone not only improved solubility but also helped the protein fold correctly.

Data Presentation: Quantitative Barrier Analysis

| Transcription Factor | Manipulation | Effect on Promoter Activity | Resulting Fold-Change in Protein Expression* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loc1p | Knockout | Increased | Up to 1.96-fold increase |

| Msn2p | Knockout | Increased | Up to 2.43-fold increase |

| Gsm1p | Overexpression | Increased | Up to 2.20-fold increase |

| Hot1p | Overexpression | Increased | Up to 1.65-fold increase |

*Model protein: Xylanase. Combined manipulation of factors showed additive effects.

| Source of Burden | Impact on Host Cell | Consequence for Protein Production |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Competition (Nucleotides, Amino Acids) | Depletion of precursors for growth and native proteins | Reduced cell growth and viability; lower overall protein titer |

| Energy Consumption (ATP) | High demand for transcription, translation, and folding | Metabolic stress; potential activation of stress responses that inhibit production |

| Ribosome Engagement | Saturation of translational machinery | Slowed global translation rates; increased error frequency |

| Secretory Pathway Saturation | Overloading of ER and Golgi | Mislocalization, aggregation, and degradation of the secretory protein |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Multi-level Barriers in Heterologous Expression

Heterologous Expression Barrier Cascade

Diagram 2: Transcriptional Barrier & Engineering Strategy

Transcriptional Inhibition and Resolution

Diagram 3: Workflow for Systematic Troubleshooting

Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Barrier Investigation and Mitigation

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter Library | A set of promoters with varying strengths. | Identifying the optimal transcriptional drive for a specific protein to balance yield and burden [19]. |

| Codon-Optimized Gene | A synthetic gene sequence designed with the host's preferred codons. | Overcoming translational barriers caused by rare codons and improving protein yield [20]. |

| Molecular Chaperones | Proteins that assist in the folding of other polypeptides (e.g., Hsp70, Hsp104). | Co-expressed to prevent aggregation and improve solubility of difficult-to-express proteins [23] [24]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132) | Chemicals that inhibit the proteasome degradation machinery. | Used experimentally to determine if a low-yield protein is being rapidly degraded after synthesis [23]. |

| RNA-seq / Ribo-seq | Next-generation sequencing techniques. | RNA-seq maps the transcriptome to check mRNA levels. Ribo-seq maps ribosome positions to identify translational pausing [19] [20]. |

| Knockout / Overexpression Strains | Engineered host strains with specific genes deleted or overexpressed. | Validating the role of specific transcription factors or chaperones as barriers or helpers in expression [19]. |

| A2AR/A2BR antagonist 1 | A2AR/A2BR antagonist 1, MF:C24H17N9, MW:431.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Icmt-IN-25 | Icmt-IN-25|ICMT Inhibitor|For Research Use | Icmt-IN-25 is a potent ICMT inhibitor for cancer research. It targets Ras protein maturation. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Building a Robust System: Modern Platforms and Genetic Toolkits for Successful Expression

Troubleshooting Guide: Micro-HEP inStreptomyces

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our research group is experiencing low conjugation efficiency when transferring large Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) from E. coli to our Streptomyces chassis. What could be the cause and how can we improve this?

A: Low conjugation efficiency, especially with large BGCs, is a common challenge. The traditional system, E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002), is known to have limitations with the stability of repeated sequences, which can lead to incorrect exconjugants or failed transfers [15].

- Solution: Implement the improved E. coli strains from the Micro-HEP platform. These strains are engineered for superior stability of repeat sequences and offer higher efficiency for the modification and conjugative transfer of foreign BGCs [15].

- Actionable Protocol: When cloning BGCs with repetitive sequences, use the Micro-HEP's bifunctional E. coli strains that feature a rhamnose-inducible

redαβγrecombination system. This system facilitates the precise insertion of RMCE cassettes and enhances the overall stability of the construct prior to conjugation [15].

Q2: After successful integration, the yield of our target natural product is still very low. What strategies can we use to enhance expression?

A: Low yield can stem from various factors, including low gene dosage or metabolic burden on the host.

- Solution 1: Implement Copy Number Amplification. A key advantage of the Micro-HEP platform is the use of Recombinase-Mediated Cassette Exchange (RMCE) for multi-copy integration. Research has demonstrated that increasing the copy number of a BGC can directly correlate with increased product yield. For example, integrating two to four copies of the xiamenmycin (

xim) BGC led to a rising yield of xiamenmycin [15]. - Solution 2: Use an Optimized Chassis Strain. Ensure you are using a dedicated chassis like S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023. This strain is engineered by deleting four endogenous BGCs (for actinorhodin, prodiginine, CPK, and CDA) to minimize native metabolic interference and free up precursor pools for heterologous pathway flux [15] [26]. Further engineering with point mutations in

rpoBandrpsLcan pleiotropically increase secondary metabolite production [26].

Q3: We want to integrate multiple BGCs into the same chassis strain. How can we avoid cross-reaction between different recombination systems?

A: The Micro-HEP platform is designed for this purpose through the use of orthogonal recombination systems.

- Solution: Utilize the modular RMCE cassettes provided by the platform. These cassettes use distinct, non-cross-reacting recombinase-target site pairs: Cre-

lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, andphiBT1-attP[15]. The tyrosine recombinases (Cre, Flp, Dre, Vika) exhibit stringent substrate specificity, meaning they exclusively recognize their own target sites with no cross-reactivity in vivo [15]. - Actionable Protocol: Design your integration strategy to use a different orthogonal system (e.g., Cre-

loxfor one BGC and Vika-voxfor another) for each BGC you wish to introduce. This allows for stable, independent integration of multiple gene clusters into the pre-engineered chromosomal loci of the chassis strain [15].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Two-Step Recombineering for Markerless DNA Manipulation in E. coli [15]

This protocol is central to modifying BGCs in the Micro-HEP platform's bifunctional E. coli strains.

- Strain Preparation: Electroporate the recombinase expression plasmid

pSC101-PRha-αβγA-PBAD-ccdAinto your chosen E. coli strain. Grow this strain at 30°C due to the temperature-sensitive nature of the plasmid. - First Round of Recombineering: Induce the plasmid with a combination of 10% L-rhamnose and 10% L-arabinose. This dual induction expresses the Redα/Redβ/Redγ recombinases and the CcdA protein. The recombinases facilitate the replacement of your target gene with a selectable cassette (e.g.,

amp-ccdBorkan-rpsL). - Selection and Counterselection: Select for clones that have successfully integrated the cassette.

- Second Round of Recombineering: In the second step, induce only the recombinases (using L-rhamnose) to replace the selection cassette with your desired, markerless modification.

Protocol: Heterologous Expression of BGCs using RMCE in S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 [15]

- BGC Modification in E. coli: Clone your target BGC into a suitable plasmid. Using the two-step recombineering protocol above, insert an RMCE integration cassette into this plasmid. This cassette must contain the transfer origin site

oriT, an integrase gene, and its corresponding recombination target site (RTS). - Conjugative Transfer: Mobilize the

oriT-bearing plasmid from the engineered E. coli donor strain into the chassis strain S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 via biparental conjugation. - RMCE Integration: Inside the chassis strain, the expressed integrase catalyzes the precise exchange of the BGC from the plasmid into the pre-engineered chromosomal RTS locus, without integrating the plasmid backbone.

- Fermentation and Analysis: Grow exconjugants in appropriate media, such as GYM medium for relative quantitative analysis [15]. Analyze the culture for the production of the target compound using techniques like liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the Micro-HEP Platform in Streptomyces [15]

| Parameter | Experimental Result | Significance / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| BGC Transfer Stability | Superior to traditional E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) | Improved reliability in obtaining correct exconjugants, especially for large BGCs with repeats. |

| Xiamenmycin Yield vs. Copy Number | Yield increased with 2 to 4 copies of the xim BGC |

Demonstrates copy number as a viable yield optimization strategy. |

| New Compound Discovery | Efficient expression of the grh BGC led to identification of Griseorhodin H |

Validates the platform's utility in activating cryptic BGCs and discovering novel natural products. |

| 3FAx-Neu5Ac | 3FAx-Neu5Ac, MF:C22H30FNO14, MW:551.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Parp7-IN-18 | Parp7-IN-18, MF:C23H26ClF3N6O4, MW:542.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Troubleshooting Guide:Aspergillus nigerChassis

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: The yield of our heterologous protein in A. niger is extremely low (~mg/L) compared to homologous proteins ( ~g/L). What are the primary bottlenecks?

A: This disparity is a well-known challenge. The low yield of heterologous proteins, especially those of non-fungal origin, results from bottlenecks across the entire secretion pathway [27] [28] [29]. Key issues include:

- Transcriptional Level: Weak promoter strength, low gene copy number, and suboptimal genomic integration locus [28] [30].

- Post-Translational Level: Misfolding in the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), triggering of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) and ER-Associated Degradation (ERAD), and inefficiencies in vesicular transport through the Golgi [28] [30].

- Extracellular Degradation: Proteolysis by native extracellular proteases like PepA [28] [30].

Q2: How can we protect our small, hard-to-express heterologous protein from degradation and improve its detection?

A: For small proteins like monellin (~11 kDa), detection itself can be a challenge.

- Solution 1: Use a HiBiT-Tag System. Fuse a small, 1.3 kDa HiBiT peptide to your target protein. This tag generates bright, quantitative luminescence upon complementation with LgBiT, enabling highly sensitive detection without antibodies, which is crucial for tracking ultra-low expression levels [28].

- Solution 2: Implement Protease Knockouts. Genetically disrupt major extracellular protease genes, such as

pepAandpepB. Studies show that single (∆pepA) and double (∆pepA, ∆pepB) knockouts can significantly enhance the stability and final yield of secreted heterologous proteins [28] [30]. - Solution 3: Protein Fusion. Fuse your small heterologous protein to a larger, highly expressed endogenous carrier protein like glucoamylase (GlaA). This strategy can improve stability and leverage the strong secretion signals of the carrier [28].

Q3: We have integrated our gene of interest, but protein titers remain low. What genetic engineering strategies can we use to enhance the host's secretion capacity?

A: Engineering the host's secretory machinery is often necessary.

- Solution 1: Enhance the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR). Overexpress key molecular chaperones like binding protein (BipA) and protein disulfide isomerase (PdiA) to improve folding efficiency in the ER and reduce misfolding [28].

- Solution 2: Modulate the ERAD Pathway. Attenuate the ERAD pathway by knocking down genes like

derAorhrdCto reduce the degradation of correctly folded or foldable proteins [28]. - Solution 3: Engineer Vesicular Trafficking. Overexpress components of the vesicular transport system, such as the COPI component Cvc2. This has been shown to enhance the production of proteins like pectate lyase (MtPlyA) by 18%, likely by optimizing ER-Golgi homeostasis and cargo sorting [30].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Construction of a Low-Background A. niger Chassis Strain [30]

This protocol outlines the creation of a superior host strain for heterologous expression.

- Start with an Industrial Strain: Begin with a high-producing industrial strain like AnN1, which contains ~20 copies of the Talaromyces emersonii glucoamylase (TeGlaA) gene and possesses robust transcriptional and secretory machinery.

- CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Deletion: Use a marker-free CRISPR/Cas9 system to delete 13 of the 20 TeGlaA gene copies. This drastically reduces the background of secreted native proteins.

- Protease Gene Disruption: Further disrupt the major extracellular protease gene

pepAusing the same CRISPR/Cas9 system. - Strain Validation: The resulting chassis strain (e.g., AnN2) exhibits ~61% less extracellular protein and significantly reduced glucoamylase activity, providing a clean background while retaining multiple transcriptionally active integration loci for target genes [30].

Protocol: Strategy for Expressing Ultra-Low Level Heterologous Proteins [28]

This protocol is based on the expression of monellin in A. niger.

- Gene Construction: Codon-optimize the heterologous gene (e.g., monellin) for A. niger. Fuse it C-terminally to a HiBiT-Tag for sensitive detection.

- Strain Engineering: Use a chassis strain with a

∆kusA(KU70 homolog) background to improve homologous recombination efficiency. - Multi-Copy Integration: Increase the copy number of the expression cassette (e.g., from 1 to 5 copies) to boost transcriptional output.

- Secretion Pathway Engineering: Combine the multi-copy integration with:

- Knockout of extracellular proteases (

pepA,pepB). - Overexpression of phospholipid synthesis genes (

ino2,opi3) to enhance biomembrane capacity.

- Knockout of extracellular proteases (

- Fermentation Optimization: Cultivate the best-performing engineered strain in an optimized starch fermentation medium in shake flasks at 30°C. Quantify the target protein in the supernatant using the HiBiT luminescence assay.

Table 2: Performance of Engineered Aspergillus niger Expression Platforms

| Parameter / Strategy | Host Strain / Result | Outcome / Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Background Chassis | AnN2 (∆13xTeGlaA, ∆pepA) | 61% reduction in background protein; yields of 110.8 - 416.8 mg/L for 4 diverse proteins. | [30] |

| Monellin Expression | Engineered SH-2 strain | Achieved 0.284 mg/L in shake flask via multi-copy integration, fusion, and protease knockout. | [28] |

| Vesicular Trafficking Engineering | Overexpression of COPI component Cvc2 | Enhanced MtPlyA production by 18%. | [30] |

| Protease Deletion | Single (∆pepA) and Double (∆pepA, ∆pepB) knockouts | Significantly increased heterologous protein stability and final titer. | [28] [30] |

Secretion Pathway and Engineering Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Advanced Heterologous Expression Platforms

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bifunctional E. coli Strains (Micro-HEP) | Engineered for both Red recombineering and conjugative transfer; offer superior stability for repeated sequences. | Cloning, modification, and transfer of large BGCs in Streptomyces projects [15]. |

| Chassis Strain: S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 | Deletion of 4 endogenous BGCs and introduction of multiple orthogonal RMCE sites. | Clean background host for high-yield heterologous expression of natural products [15]. |

| Modular RMCE Cassettes | Pre-built cassettes with orthogonal recombinase-target sites (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, phiBT1-attP). | Precise, multi-copy, and backbone-free integration of BGCs into the Streptomyces chromosome [15]. |

| Chassis Strain: A. niger AnN2 | Industrial strain engineered by deleting 13/20 glucoamylase genes and the pepA protease. | Low-background host with vacant, high-expression loci for integrating heterologous genes [30]. |

| HiBiT-Tag System | A 1.3 kDa peptide that enables highly sensitive, quantitative luminescence detection of proteins. | Detecting and quantifying ultra-low expression levels of hard-to-express proteins like monellin [28]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System for A. niger | Tool for precise gene knockouts (e.g., proteases), gene insertions, and multi-copy engineering. | Creating chassis strains (e.g., AnN2) and integrating target genes into specific genomic loci [30] [31]. |

| BiP substrate | BiP substrate, MF:C38H57N9O9, MW:783.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Vista-IN-3 | Vista-IN-3|VISTA Inhibitor|For Research Use | Vista-IN-3 is a potent VISTA checkpoint inhibitor for cancer immunology research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

CRISPR/Cas9-Driven Genome Editing for Creating Clean Chassis Strains

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my genome editing efficiency low, and how can I improve it?

Low editing efficiency is a common challenge that can stem from multiple factors. The table below summarizes the primary causes and evidence-based solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Editing Efficiency

| Problem Cause | Evidence-Based Solution | Key Experimental Protocol/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Poor sgRNA Design | - Design 3-4 different sgRNAs targeting the same gene [32].- Use optimized sgRNAs with ~20 nucleotide spacer sequences and 40-60% GC content [33].- Ensure the 12-nucleotide "seed" region adjacent to the PAM is highly specific [32]. | Protocol: Use computational tools (e.g., GuideScan) to design sgRNAs with high on-target scores and minimal off-target potential. Test multiple designs in parallel [33]. |

| Inefficient Delivery | - Use RNP (Ribonucleoprotein) complexes (pre-assembled Cas9 protein + sgRNA) via electroporation or lipofection for precise control and reduced toxicity [34].- For yeast, employ a single-vector system expressing both Cas9 and sgRNA, enabling 70-100% editing efficiency [35]. | Protocol (Yeast): Clone Cas9 under a constitutive promoter (e.g., TEF1) and sgRNA under the SNR52 promoter into a single plasmid. Transform via standard methods and select with G418 [35]. |

| Low HDR Efficiency | - For knock-ins, use Cas9 nickase (Cas9n) with a pair of sgRNAs to create single-strand breaks, which enhances specificity and can improve HDR outcomes [34] [32].- Enrich for edited cells via antibiotic selection or FACS after transfection [32]. | Protocol: When using a nickase, design two sgRNAs targeting adjacent sites on opposite DNA strands. Provide a dsDNA donor template with sufficient homology arms. |

| Host-Specific Barriers | - Harness endogenous CRISPR-Cas machinery. In Clostridium, using the native Type I-B system yielded 100% editing efficiency vs. 25% with heterologous Cas9 [36].- In Gram-negative bacteria like Pseudomonas, use a tailored cytidine base editor (CBE) to introduce point mutations with >90% efficiency [37]. | Protocol (Bacteria): For CBE, express a fusion of cytidine deaminase and nCas9 (nickase). Design sgRNAs to target a C within a 13-19 bp window upstream of an NGG PAM [37]. |

How can I minimize off-target effects in my chassis strain?

Off-target effects pose a significant risk for generating unintended mutations, which is critical to avoid when creating a clean chassis. The following strategies are recommended to enhance specificity.

Table 2: Strategies to Mitigate Off-Target Effects

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | Use engineered Cas9 proteins (e.g., Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9) with reduced off-target activity while retaining on-target potency [34] [33]. | Ideal for therapeutic development and creating high-quality chassis strains. |

| RNP Delivery | Delivering pre-complexed Cas9 protein and sgRNA limits the time the nuclease is active in the cell, reducing opportunities for off-target cleavage [34] [33]. | More precise than plasmid-based delivery, which leads to prolonged Cas9/sgRNA expression. |

| Computational sgRNA Design | Use bioinformatics tools to scan the reference genome and select sgRNAs with minimal sequence similarity to other genomic regions [33]. | Avoids sgRNAs with high homology to repetitive or conserved sequences. |

| "Double-Nicking" Strategy | Use a pair of Cas9 nickases with two adjacent sgRNAs. A double-strand break only occurs when both nickases bind correctly, dramatically raising specificity [32]. | Requires careful design of two sgRNAs in close proximity. |

| Titrate sgRNA and Cas9 | Optimizing the ratio and concentration of CRISPR components can improve the on-target to off-target cleavage ratio [32]. | High concentrations can increase off-target effects; find the minimum effective dose. |

What delivery method should I use for my specific host organism?

The choice of delivery method is highly dependent on the host organism. The table below outlines optimized protocols for different model systems.

Table 3: Recommended Delivery Methods by Host Organism

| Host Organism | Recommended Method | Key Protocols and Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| Mammalian Cells | Lipofection or Electroporation of RNPs [34]. | Protocol: Use the Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 System. For lipofection, complex the RNP with cationic lipid transfection reagent. For electroporation (e.g., Neon System), deliver RNP complexes directly into the cytoplasm [34]. |

| Yeast (S. cerevisiae) | Single-Vector Plasmid System [35]. | Protocol: Use a plasmid with a 2µ origin for high copy number and a dominant selection marker (e.g., G418 resistance). Express Cas9 constitutively (TEF1 promoter) and sgRNA via the SNR52 promoter [35]. |

| Mouse Zygotes | Electroporation or Microinjection of RNPs [34]. | Protocol: Electroporation of RNP complexes into zygotes is an efficient method for generating edited mice without the need for pronuclear injection [34]. |

| Zebrafish Embryos | Microinjection of RNPs [34]. | Protocol: Inject pre-assembled Cas9 protein and sgRNA complexes into one-cell stage embryos [34]. |

| C. elegans | Injection of RNPs [34]. | Protocol: Inject RNP complexes into the germline of adult animals [34]. |

| Gram-Negative Bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas) | Plasmid-based Base Editing [37]. | Protocol: Use a modular plasmid system expressing a cytidine base editor (nCas9-deaminase fusion) and a multiplexable gRNA cassette. Transform via standard methods [37]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: There is no canonical NGG PAM site near my target of interest. What are my options? A1: You have several alternatives:

- Use Cas9 variants with altered PAM specificities. New engineered Cas9 proteins recognize a broader range of PAM sequences.

- Consider the NAG PAM. For S. pyogenes Cas9, NAG can function as an alternative PAM, though with about one-fifth the efficiency of NGG [32].

- Switch to another CRISPR system. The Cas12a (Cpf1) nuclease, for example, recognizes T-rich PAM sequences (e.g., TTTN), which can provide targeting access to different genomic regions [34] [38].

Q2: How can I confirm that my clean chassis strain is free of off-target mutations? A2: A combination of computational and experimental methods is recommended:

- In silico Prediction: Before experiments, use bioinformatics tools to predict potential off-target sites for your sgRNA and avoid designs with high-risk profiles [33].

- Post-editing Analysis: After editing, use highly sensitive genome-wide methods like GUIDE-seq or Digenome-seq to empirically identify double-strand breaks across the entire genome [33] [38]. For a final validation step, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of your edited strain provides the most comprehensive picture of its genomic integrity [33].

Q3: My chassis strain is difficult to transform with CRISPR plasmids. How can I overcome this? A3: Transformation efficiency can be a major bottleneck, especially in non-model organisms.

- Utilize Endogenous Systems: If your host organism possesses a native CRISPR-Cas system, it can be co-opted for editing. This bypasses the need for heterologous Cas9 expression, which was key to achieving 100% efficiency in Clostridium [36].