Precise Metabolic Engineering: A Comprehensive Guide to dCas9 sgRNA Design for Effective Pathway Knockdown

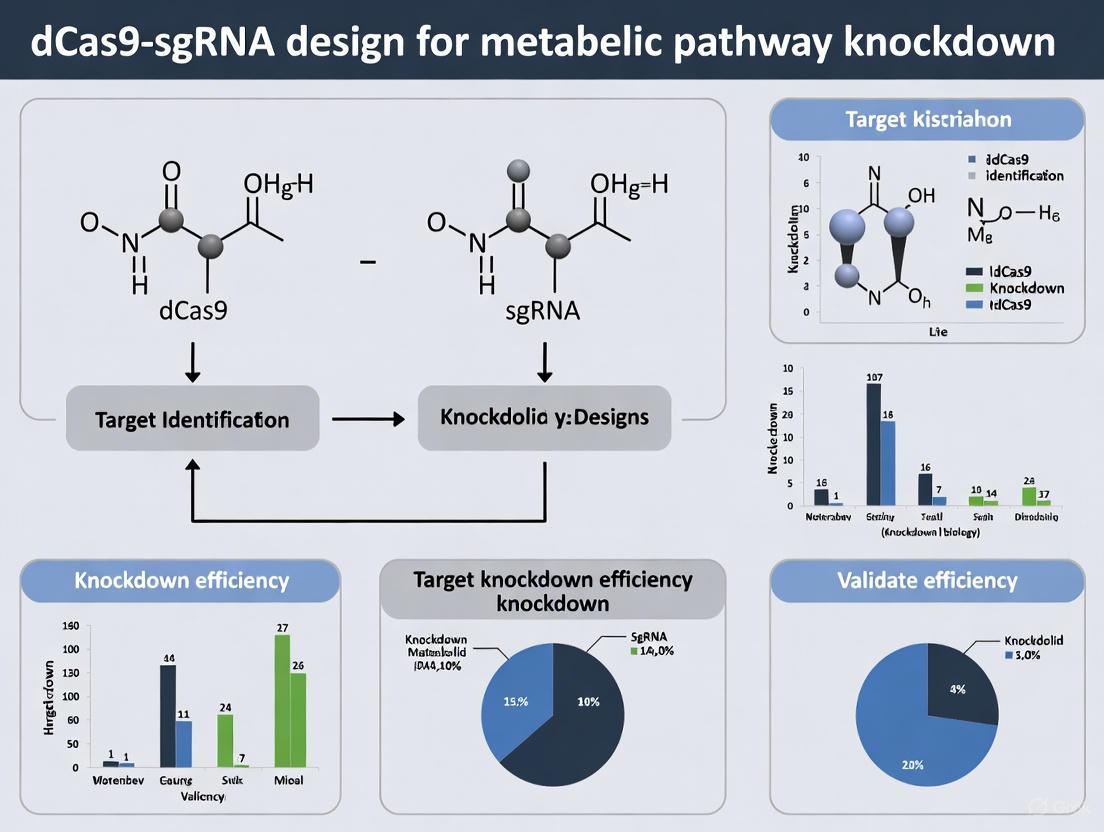

This article provides a complete framework for designing highly effective dCas9 sgRNAs tailored for metabolic pathway knockdown.

Precise Metabolic Engineering: A Comprehensive Guide to dCas9 sgRNA Design for Effective Pathway Knockdown

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for designing highly effective dCas9 sgRNAs tailored for metabolic pathway knockdown. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it bridges foundational concepts and advanced methodologies. The content systematically covers the core principles of CRISPRi/a systems, strategic sgRNA design for transcriptional repression, practical optimization to maximize knockdown efficiency, and robust validation techniques. By integrating the latest algorithmic tools and experimental data, this guide empowers the development of precise genetic tools to dissect and engineer metabolic networks for therapeutic and bioproduction applications.

Understanding dCas9 Systems: From CRISPR Knockout to Transcriptional Control for Metabolic Engineering

Catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) serves as the foundational engine for powerful, non-cutting CRISPR technologies that enable precise transcriptional control without altering DNA sequence. Derived from the CRISPR-Cas9 system, dCas9 retains its programmable DNA-binding capability but lacks nuclease activity due to point mutations in its RuvC and HNH domains. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of dCas9-based CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems, with particular emphasis on their application in metabolic pathway knockdown research. We detail molecular mechanisms, experimental protocols for implementation, and design considerations for single-guide RNA (sgRNA) design, supplemented with structured data tables and workflow visualizations to facilitate robust experimental planning for researchers and drug development professionals.

Catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) represents a groundbreaking engineered variant of the native Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 protein that forms the core of programmable transcriptional regulation systems. The creation of dCas9 involves introducing specific point mutations (D10A in the RuvC domain and H840A in the HNH domain) that completely abolish its DNA-cleavage activity while preserving its robust ability to bind DNA targets in an RNA-guided manner [1] [2]. This fundamental transformation converts a DNA-cutting enzyme into a precision DNA-binding platform that can be targeted to any genomic locus complementary to a designed sgRNA sequence.

The dCas9 system functions as a programmable DNA-binding vehicle that operates independently of permanent genetic modifications. When complexed with sgRNA, dCas9 binds specifically to target DNA sequences through base pairing between the sgRNA spacer region and the complementary DNA strand, adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence [1] [3]. This binding mechanism remains identical to wild-type Cas9, with the critical distinction that dCas9 creates no double-stranded DNA breaks, thus eliminating the error-prone DNA repair processes associated with conventional CRISPR editing [4].

The development of dCas9 has enabled the creation of two powerful transcriptional modulation technologies: CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for gene repression and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) for gene activation [5]. Both systems leverage the programmable DNA-binding capability of dCas9 while fusing or recruiting effector domains to achieve transcriptional control. This non-cutting approach provides significant advantages for metabolic pathway research, including reversible gene modulation, fine-tuned knockdown rather than complete knockout, and the ability to study essential genes without inducing cell death [5] [6].

Molecular Architecture of dCas9 Systems

Structural Basis of dCas9 DNA Binding

The molecular architecture of dCas9 maintains the multi-domain structure of wild-type Cas9, comprising recognition (REC) and nuclease (NUC) lobes that coordinate DNA recognition and binding [7]. Structural studies using cryo-electron microscopy have revealed that dCas9 undergoes significant conformational changes upon sgRNA and target DNA binding, particularly in the HNH domain, which rotates approximately 170° to adopt a DNA cleavage-activating position despite its catalytic inactivation [7]. This structural rearrangement enables stable DNA binding and positions fused effector domains for optimal interaction with transcriptional machinery.

The dCas9-sgRNA complex binds DNA by unwinding the double helix and forming an R-loop structure where the sgRNA spacer forms a heteroduplex with the target DNA strand [7]. This binding is contingent upon the presence of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) immediately downstream of the target site (5'-NGG-3' for S. pyogenes dCas9), which serves as an essential recognition signal for initial DNA binding [1] [4]. The PAM requirement represents a key consideration for targetable sequences in metabolic pathway genes.

Table 1: Core Components of dCas9 Systems for Transcriptional Control

| Component | Function | Key Features | Considerations for Metabolic Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Protein | Programmable DNA-binding platform | Catalytically inactive (D10A, H840A mutations); retains DNA binding specificity | Orthogonal variants available for multiplexing |

| Guide RNA (sgRNA) | Targeting specificity | 20-nt spacer sequence complementary to target; scaffold structure binds dCas9 | Design critical for efficiency; position-dependent effects |

| Effector Domains | Transcriptional modulation | Fused to dCas9 (e.g., KRAB for repression, VP64 for activation) | Strength varies by domain; can impact specificity |

| Promoter Elements | Expression control | Determines dCas9 and sgRNA expression levels | Tunable systems allow dose-response studies |

CRISPRi: Mechanisms of Transcriptional Repression

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) functions as a potent gene repression system that achieves knockdown by sterically hindering RNA polymerase binding or progression during transcription [1] [5]. The fundamental CRISPRi architecture consists of dCas9 alone or fused to repressor domains such as the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB), which recruits additional chromatin-modifying complexes to enhance repression [6] [3]. When targeted to regions near the transcription start site (TSS) of a gene, the dCas9-repressor fusion creates a functional blockade that prevents transcriptional initiation or elongation.

The KRAB domain functions by recruiting endogenous repressive complexes that establish heterochromatin states through histone modifications, including H3K9 trimethylation, which creates a heritably silent chromatin environment [6] [8]. This epigenetic silencing mechanism enables more potent and durable repression than steric hindrance alone, making it particularly valuable for long-term metabolic pathway studies where sustained knockdown is required. Advanced CRISPRi systems have developed enhanced repressor domains such as SALL1-SDS3 fusions that demonstrate improved repression potency compared to traditional KRAB-based systems while maintaining high specificity [9].

CRISPRa: Mechanisms of Transcriptional Activation

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) serves as the functional inverse of CRISPRi, designed to enhance gene expression through recruitment of transcriptional activation machinery to specific promoters [5] [4]. The basic CRISPRa architecture employs dCas9 fused to activator domains such as VP64 (a tetramer of VP16 peptides), which directly interacts with and recruits components of the basal transcription apparatus [6]. Early CRISPRa systems showed limited efficacy with single sgRNAs, prompting the development of enhanced systems that significantly improve activation potency.

Three principal strategies have emerged for enhanced CRISPRa activation:

- Direct activator fusions such as VPR, which combines VP64 with the activation domains of p65 and Rta [6]

- Protein scaffolding systems like SunTag, which employs multiple copies of peptide epitopes to recruit numerous activator molecules [5] [6]

- RNA scaffolding approaches including the Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) system, which uses MS2 RNA hairpins in the sgRNA to recruit additional activation domains [6]

These advanced systems enable robust transcriptional activation of endogenous genes, typically in the range of 3- to 10-fold increases, making them suitable for gain-of-function studies in metabolic engineering [6] [4].

Experimental Framework for dCas9-Mediated Perturbation

sgRNA Design Principles for Metabolic Pathway Engineering

Effective sgRNA design represents the most critical determinant of success in dCas9-based metabolic pathway perturbation. The positioning of sgRNA target sites relative to the transcription start site (TSS) directly impacts system efficacy, with optimal locations varying between CRISPRi and CRISPRa applications [5] [9].

For CRISPRi-mediated repression, sgRNAs should target regions within -50 to +300 base pairs relative to the TSS, with the most potent repression typically achieved when targeting sites immediately downstream of the TSS (+1 to +100) where they can effectively block RNA polymerase progression [9]. This positioning creates a steric hindrance that physically prevents transcription initiation or early elongation. Repression efficiency can be further enhanced by using multiple sgRNAs targeting the same gene, which collectively improve knockdown potency through cooperative binding [9].

For CRISPRa-mediated activation, sgRNAs should be designed to target enhancer regions or promoter elements upstream of the TSS (-50 to -500 base pairs) where transcription factors naturally bind to regulate gene expression [5] [4]. CRISPRa systems perform optimally when targeting accessible chromatin regions without nucleosome occlusion, requiring consideration of local epigenomic context. The activation strength can be significantly improved by using multiple sgRNAs targeting different regions of the same promoter, with synergistic effects observed in systems like SAM that leverage multiple activation domains [6].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of CRISPRi and CRISPRa Systems

| Parameter | CRISPRi | CRISPRa | CRISPR Knockout |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Steric hindrance + chromatin silencing | Recruitment of activators | DNA cleavage + NHEJ repair |

| Genetic Alteration | None | None | Permanent indels |

| Efficiency | 60-95% repression [9] | 3-10x activation [6] | >90% knockout |

| Reversibility | Reversible | Reversible | Permanent |

| sgRNA Targeting | TSS-proximal (0 to +300 bp) [9] | Promoter/enhancer regions | Coding sequences |

| Applications in Metabolic Research | Fine-tuning pathway flux; Essential gene study | Pathway enhancement; Gain-of-function screening | Complete gene elimination |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (dCas9 expressed once) | High (dCas9 expressed once) | Moderate (requires multiple nucleases) |

Delivery and Implementation Protocols

Successful implementation of dCas9 systems requires optimized delivery methods and experimental timelines. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for establishing CRISPRi/a in mammalian cell systems for metabolic pathway engineering:

Day 1: Cell Seeding

- Seed appropriate host cells (HEK293, K562, or iPSCs) at 30-50% confluence in complete growth medium

- Include control wells for normalization and efficiency assessment

Day 2: Delivery of dCas9 Components

- Option A: Lentiviral Delivery - Transduce cells with lentiviral particles encoding dCas9-effector fusions at appropriate MOI (typically 3-10)

- Option B: Transient Transfection - Co-transfect dCas9-effector plasmid (1-2 μg) and sgRNA expression vector (0.5-1 μg) using preferred transfection reagent

- Include selection markers (puromycin, blasticidin) for stable line generation if using lentiviral approach

Day 3-5: Selection and Recovery

- Begin antibiotic selection 24 hours post-transduction/transfection (if applicable)

- Maintain cells in normal growth conditions with regular monitoring

Day 6-8: Functional Validation

- Harvest cells for RNA/protein analysis 72-96 hours post-delivery

- Assess knockdown/activation efficiency via qRT-PCR for transcript level changes

- Validate functional effects through metabolic assays specific to target pathway

Extended Applications:

- For stable cell line generation, continue selection for 7-14 days before expansion

- For inducible systems, add doxycycline (500 ng/mL) or other inducer at Day 5 for timed perturbation [8]

This timeline can be adapted for specific cell types and experimental requirements, with metabolic phenotyping typically conducted 5-10 days post-implementation depending on protein half-life and pathway dynamics.

Validation and Optimization Methods

Rigorous validation of dCas9-mediated perturbations is essential for reliable metabolic pathway research. The following hierarchical approach ensures comprehensive characterization:

Transcript-Level Validation:

- qRT-PCR: Most accessible method for quantifying expression changes; use ΔΔCq method with housekeeping genes (GAPDH, ACTB) for normalization [9]

- RNA-seq: Provides unbiased assessment of on-target efficacy and genome-wide specificity; identifies potential off-target transcriptional effects

- Multiplexed assays: NanoString or other multiplexed platforms enable efficient validation of multiple pathway components

Protein-Level Validation:

- Western blotting: Confirms functional protein level changes; critical for metabolic enzymes where transcript changes may not directly correlate with activity

- Immunofluorescence: Enables single-cell resolution of protein expression in heterogeneous cell populations

- Mass spectrometry: Offers untargeted proteomic profiling to verify pathway-specific effects and identify compensatory mechanisms

Functional Metabolic Validation:

- Target-specific assays: Enzyme activity assays, substrate utilization measurements, or metabolic flux analysis

- Pathway-output readouts: LC-MS metabolomics for comprehensive pathway profiling

- Phenotypic assays: Cell growth, viability, or product formation under selective conditions

Optimization should include titration of dCas9 expression levels (particularly in inducible systems) and testing multiple sgRNAs per target to identify the most effective combinations [8] [9]. For metabolic studies, time-course experiments are recommended to capture both immediate and adaptive responses to pathway perturbation.

Advanced Applications in Metabolic Pathway Research

Bidirectional Epigenetic Editing with CRISPRai

The recently developed CRISPRai platform enables simultaneous activation and repression of distinct genetic loci within single cells, providing powerful capabilities for analyzing regulatory relationships in metabolic pathways [8]. This system employs orthogonal dCas9 proteins from different bacterial species (typically S. pyogenes and S. aureus) fused to opposing effector domains, allowing independent targeting of activation and repression to different genomic locations.

In metabolic engineering, CRISPRai facilitates the study of regulatory hierarchies and pathway control nodes by simultaneously upregulating rate-limiting enzymes while downregulating competing pathways [8]. This approach was successfully applied to study the interaction between transcription factors SPI1 and GATA1 in hematopoietic lineages, demonstrating that bidirectional perturbation enabled enhanced modulation of lineage signatures compared to single perturbations [8]. For metabolic researchers, this technology enables sophisticated pathway optimization strategies that balance flux distribution without permanent genetic changes.

High-Content Screening for Metabolic Engineering

CRISPRi and CRISPRa screens provide powerful platforms for systematic identification of metabolic regulators and potential therapeutic targets. Pooled screening approaches enable genome-scale interrogation of gene function by tracking sgRNA abundance changes in response to metabolic selection pressures [6].

Protocol for Pooled CRISPRi/a Metabolic Screening:

- Library Design: Select genome-wide or focused sgRNA library targeting metabolic genes

- Library Delivery: Transduce target cells at low MOI (<0.3) to ensure single sgRNA integration

- Selection Pressure: Apply metabolic challenge (nutrient limitation, toxin accumulation, or product toxicity)

- Sample Collection: Harvest genomic DNA at initial (T0) and endpoint (Tfinal) time points

- Sequencing & Analysis: Amplify sgRNA regions and sequence to quantify enrichment/depletion

Fitness-based screens identifying essential genes under specific metabolic conditions have revealed cancer-specific metabolic vulnerabilities and genes essential for proliferation in nutrient-limited environments [6]. For industrial biotechnology, similar approaches can identify gene knockdowns that enhance product yield or tolerance to fermentation inhibitors.

Multiplexed Pathway Engineering

The modular nature of dCas9 systems enables simultaneous regulation of multiple metabolic genes, facilitating sophisticated pathway engineering strategies. Multiplexed CRISPRi enables coordinated repression of several genes in a competing pathway, while multiplexed CRISPRa can enhance flux through biosynthetic pathways by upregulating multiple enzymes simultaneously [9].

Advanced implementation involves:

- sgRNA pooling: Combining 3-5 sgRNAs per target gene to enhance efficacy [9]

- Dosage control: Using sgRNAs with varying efficiencies to fine-tune expression levels across pathway steps

- Orthogonal systems: Employing dCas9 variants with different PAM requirements to expand targeting range

This approach has been successfully demonstrated in industrial hosts including E. coli and yeast for metabolic engineering, and in mammalian cells for therapeutic applications [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for dCas9-Mediated Metabolic Pathway Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Effector Plasmids | dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi), dCas9-VPR (CRISPRa), dCas9-SALL1-SDS3 | Provides programmable DNA-binding and transcriptional modulation | Lentiviral backbones for stable integration; inducible systems for temporal control |

| sgRNA Expression Systems | U6-driven sgRNA vectors, multiplexed sgRNA arrays | Targets dCas9 to specific genomic loci | Synthetic sgRNA for rapid screening; lentiviral for stable expression |

| Delivery Tools | Lentiviral particles, lipid nanoparticles, electroporation systems | Introduces dCas9 components into target cells | Choice depends on cell type; primary cells often require optimized methods |

| Validation Assays | qRT-PCR primers, antibody panels, metabolic flux assays | Confirms target engagement and functional effects | Multiplexed approaches recommended for pathway-level analysis |

| Control Reagents | Non-targeting sgRNAs, wild-type Cas9, empty vectors | Establishes baseline and specificity controls | Essential for interpreting screening results and off-target assessment |

dCas9-based CRISPRi and CRISPRa technologies represent a transformative approach for metabolic pathway research, offering precise, reversible transcriptional control without permanent genetic alterations. The strategic implementation of these systems enables sophisticated metabolic engineering strategies, from fine-tuning individual pathway steps to systematically mapping regulatory networks through combinatorial screening. As the field advances, improvements in sgRNA design algorithms, orthogonal dCas9 variants, and synthetic effector domains will further enhance the precision and scope of non-cutting CRISPR perturbations. For researchers investigating complex metabolic systems, these technologies provide an indispensable toolkit for elucidating pathway regulation and optimizing metabolic flux for both basic research and therapeutic development.

The functional analysis of metabolic pathways requires precise methods to modulate gene expression. CRISPR-Cas9 technology has provided two powerful, yet distinct, approaches for this purpose: CRISPR knockout (CRISPR-KO) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi). While both technologies utilize the Cas9 protein and guide RNA (gRNA) for target recognition, their fundamental mechanisms and applications differ significantly. CRISPR-KO permanently disrupts gene function by creating double-strand breaks in DNA, leading to frameshift mutations and gene knockout [10] [11]. In contrast, CRISPRi employs a catalytically inactive "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressive domains to temporarily block transcription without altering the DNA sequence [12] [4]. For researchers investigating metabolic pathways, understanding these distinctions is crucial for selecting the appropriate tool for specific experimental questions, particularly when studying essential genes or attempting to fine-tune metabolic flux.

This technical guide examines the mechanistic foundations of both technologies, provides detailed experimental protocols, and outlines their specific advantages for metabolic studies. The focus is particularly on their application within the context of dCas9 sgRNA design for metabolic pathway knockdown research, offering scientists a framework for implementing these technologies in their investigations of metabolic networks and regulatory mechanisms.

Fundamental Mechanisms: How CRISPR-KO and CRISPRi Work

CRISPR Knockout (CRISPR-KO): Permanent Gene Disruption

CRISPR-KO operates through the introduction of double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA sequence of target genes. The system consists of two key components: the Cas9 nuclease and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus complementary to its 20-nucleotide spacer sequence [10]. Upon recognition of the target site, which must be adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), Cas9 activates its two nuclease domains (RuvC and HNH) to create a DSB [4].

The cellular repair of these breaks primarily occurs through the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway. NHEJ frequently results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site. When these indels are not multiples of three nucleotides, they cause frameshift mutations that introduce premature stop codons, effectively disrupting the production of functional proteins [11]. This permanent alteration makes CRISPR-KO particularly suitable for complete and irreversible gene inactivation.

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): Reversible Transcriptional Repression

CRISPRi utilizes a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) variant, created through point mutations (D10A and H840A for SpCas9) that inactivate the nuclease domains while preserving DNA-binding capability [12] [4]. When dCas9 is directed to a target sequence by a sgRNA, it occupies the DNA without creating cuts, thereby sterically hindering RNA polymerase progression and transcription initiation [10].

The repressive activity of basic CRISPRi can be significantly enhanced by fusing dCas9 to transcriptional repressor domains such as KRAB (Krüppel-associated box). The KRAB domain recruits additional repressive complexes that promote heterochromatin formation, leading to more potent and sustained gene silencing [12] [13]. Advanced CRISPRi systems have been developed by screening numerous repressor domain fusions, with platforms like dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) demonstrating improved gene repression with reduced dependence on guide RNA sequences [14]. Since CRISPRi does not alter the DNA sequence, its effects are reversible, making it suitable for studying essential genes in metabolic pathways where permanent knockout would be lethal [10].

Direct Comparative Analysis: CRISPR-KO vs. CRISPRi

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of CRISPR Knockout vs. CRISPR Interference

| Parameter | CRISPR Knockout (KO) | CRISPR Interference (i) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanism | Catalytically active Cas9 creates double-strand breaks | Catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) blocks transcription |

| DNA Damage | Yes, direct double-strand breaks | No, reversible binding without cleavage |

| Repair Mechanism | Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) | Not applicable (no DNA damage) |

| Genetic Outcome | Permanent indels and frameshift mutations | Reversible transcriptional repression |

| Protein Effect | Complete elimination of functional protein | Partial to near-complete knockdown (70-95%) |

| Persistence | Stable, heritable genetic modification | Transient, requires sustained dCas9 expression |

| Essential Gene Studies | Lethal if gene is essential | Suitable for essential gene analysis |

| Off-Target Effects | DNA-level off-target cleavage possible | RNA-level off-target binding, generally fewer off-target effects than RNAi [10] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High for multiple gene knockouts | High for simultaneous repression of multiple genes |

| Titratable Control | Limited (all-or-nothing) | Possible with inducible systems |

| Key Applications | Complete gene inactivation, disease modeling, functional genomics | Essential gene studies, metabolic flux control, pathway fine-tuning |

Table 2: Applications in Metabolic Pathway Studies

| Research Goal | Recommended Approach | Rationale | Example Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete pathway disruption | CRISPR-KO | Irreversible inactivation of metabolic enzymes | Studying compensatory mechanisms in lipid metabolism [15] |

| Essential gene analysis | CRISPRi | Enables study of lethal gene knockouts | Investigating essential translation factors in stem cells [12] |

| Fine-tuning metabolic flux | CRISPRi | Titratable control of enzyme expression levels | Optimizing precursor synthesis in metabolic engineering [16] |

| High-throughput screening | Both, with CRISPRi advantages for essential genes | CRISPRi shows reduced off-target effects compared to RNAi [10] | Genome-wide identification of metabolic dependencies [12] [14] |

| Long-term metabolic adaptation | CRISPR-KO | Stable genetic modification | Creating stable cell lines for sustained metabolic phenotype |

| Rapid, conditional modulation | CRISPRi | Quick onset/offset of repression | Dynamic studies of metabolic regulation |

Experimental Design and Implementation

sgRNA Design Considerations for Metabolic Studies

Effective sgRNA design is crucial for both CRISPR-KO and CRISPRi applications, but key differences must be considered:

Target Region Selection: For CRISPR-KO, sgRNAs should target early exons to maximize frameshift potential. For CRISPRi, sgRNAs should target the promoter region or transcription start site (TSS) for optimal repression, typically within -50 to +300 bp relative to the TSS [12].

Efficiency Prediction: Computational tools are essential for predicting sgRNA efficiency. Benchling has been shown to provide the most accurate predictions according to recent optimization studies [14]. For CRISPRi screens, tools like CRISPRiaDesign can be employed to design optimized sgRNA libraries [12].

Specificity Considerations: BLAST analysis against the target genome is necessary to minimize off-target effects. For metabolic studies where homologous genes or gene families are common, careful specificity analysis is particularly important.

Multiplexing Designs: For pathway engineering, multiple sgRNAs can be combined to target several metabolic enzymes simultaneously. Recent advances allow high-efficiency double-gene knockouts with INDEL efficiencies exceeding 80% [14].

Delivery Methods and Experimental Workflows

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Metabolic Studies

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations for Metabolic Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Repressor Systems | dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) [14] | Transcriptional repression for CRISPRi | Enhanced repressors improve knockdown efficiency with less sgRNA dependence |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral, adenoviral, plasmid vectors | Introduction of CRISPR components | Lentiviral allows stable integration; non-integrating systems for transient expression |

| Inducible Systems | Doxycycline-inducible dCas9 [12] [14] | Temporal control of gene repression | Enables study of timing effects in metabolic regulation |

| sgRNA Formats | Chemically modified synthetic sgRNAs [10] | Enhanced stability and reduced off-target effects | Improved editing efficiency and reproducibility in primary cells |

| Screening Libraries | Custom-designed sgRNA libraries [12] | High-throughput gene function analysis | Focused libraries targeting metabolic genes available |

| Validation Tools | RT-qPCR, Western blot, metabolomics [12] | Confirmation of knockdown efficiency | Essential for correlating genetic perturbation with metabolic phenotype |

Protocol for CRISPRi Metabolic Pathway Screening

The following detailed protocol outlines the steps for conducting a CRISPRi screen to identify metabolic pathway dependencies:

Library Design and Cloning:

Cell Line Engineering:

- Generate stable dCas9-expressing cell line using AAVS1 safe harbor locus integration [12]

- Validate dCas9 expression and functionality with control sgRNAs

- Transduce at low MOI (0.3-0.5) to ensure single sgRNA integration per cell

Metabolic Selection and Screening:

- Apply relevant metabolic stresses (nutrient limitation, mitochondrial inhibitors, etc.)

- Maintain library representation (500-1000x coverage) throughout selection

- Harvest genomic DNA at multiple time points for sequencing

Analysis and Hit Validation:

- Sequence sgRNA cassettes and quantify abundance changes

- Identify significantly enriched/depleted sgRNAs using specialized analysis pipelines [12]

- Validate top hits with individual sgRNAs and metabolic assays (Seahorse, metabolomics)

Applications in Metabolic Pathway Research

Case Study: mRNA Translation Machinery in Stem Cell Metabolism

A recent comparative CRISPRi screen investigated the essentiality of mRNA translation machinery components across different cell types, including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and derived neural and cardiac cells [12]. The study revealed that human stem cells critically depend on specific quality control pathways for resolving ribosome collisions, with particular sensitivity to perturbations in the E3 ligase ZNF598. This approach demonstrated how CRISPRi can identify cell-type-specific metabolic dependencies that would be challenging to study with permanent knockout approaches, especially for essential genes in core metabolic processes.

Metabolic Engineering Applications

CRISPRi has been successfully applied to metabolic engineering, such as enhancing the production of sustainable aviation fuel precursors in Pseudomonas putida [16]. The technology enabled precise downregulation of competing metabolic pathways without permanent genetic damage, allowing fine-tuning of metabolic flux toward desired products. This application highlights CRISPRi's advantage for metabolic optimization where titratable control of enzyme expression is more valuable than complete pathway inactivation.

Lipid Metabolism Studies

Research in bovine mammary epithelial cells utilized CRISPR-KO to investigate the role of TARDBP in milk fat metabolism [15]. Complete knockout of TARDBP reduced triacylglycerol content and downregulated key lipid metabolism genes (CD36, FABP4, DGAT1, PPARG, and PPARGC1A). This example demonstrates the utility of CRISPR-KO for complete pathway dissection in metabolic studies where the goal is to understand the fundamental role of specific regulators without compensation.

CRISPR-KO and CRISPRi represent complementary tools for metabolic pathway analysis, each with distinct advantages depending on the research objectives. CRISPR-KO provides permanent, complete gene inactivation ideal for creating stable metabolic models and studying non-essential pathways. Conversely, CRISPRi offers reversible, titratable control of gene expression that is particularly valuable for studying essential metabolic genes and fine-tuning pathway flux.

The ongoing development of more precise CRISPR systems, including enhanced repressors like dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) [14] and advanced delivery methods, will further expand applications in metabolic research. Integration of these technologies with multi-omics approaches and computational modeling will enable unprecedented dissection of metabolic network regulation and accelerate both fundamental discoveries and applied metabolic engineering efforts.

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Rejects Interference (CRISPRi) has emerged as a powerful tool for precise transcriptional regulation in metabolic engineering. Derived from the CRISPR/Cas9 system, CRISPRi utilizes a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) protein fused to transcriptional effector domains to selectively repress target genes without altering the DNA sequence [1]. This technology enables systematic optimization of metabolic pathways by downregulating competing or regulatory genes to enhance flux toward desired products [17]. For metabolic pathway knockdown research, CRISPRi offers significant advantages over traditional gene knockout approaches, as it allows reversible and tunable repression, enabling fine-tuning of pathway intermediates without complete pathway disruption. The core system comprises three integrated components: single guide RNA (sgRNA) for target specificity, dCas9 as a DNA-binding scaffold, and transcriptional repressors that execute gene silencing functions [1]. This technical guide examines each component in detail, providing frameworks for their application in metabolic engineering research.

Core Component 1: Single Guide RNA (sgRNA)

Structure and Function

The single guide RNA (sgRNA) is a synthetic RNA molecule that combines two natural RNA components—the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA)—into a single construct [18]. This engineered molecule serves as the targeting module of the CRISPRi system, directing the dCas9-effector complex to specific DNA sequences through Watson-Crick base pairing. The sgRNA consists of a customizable 17-20 nucleotide guide sequence at its 5' end that is complementary to the target DNA, and a scaffold sequence that interacts with the dCas9 protein [18]. The guide sequence determines system specificity, while the scaffold structure ensures proper complex formation with dCas9.

Table 1: sgRNA Design Parameters for Optimal Performance

| Design Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Guide Length | 17-23 nucleotides | Balances specificity and efficiency [18] |

| GC Content | 40-80% (40-60% ideal) | Higher stability; prevents secondary structures [1] [18] |

| PAM Proximity | Immediate 5' adjacent to target | Essential for dCas9 binding [1] |

| Off-Target Potential | Minimal mismatches, especially near PAM | Reduces unintended binding [19] |

Design Considerations for Metabolic Engineering

Effective sgRNA design for metabolic pathway knockdown requires strategic target selection and rigorous specificity validation. For repression of metabolic genes, sgRNAs should be designed to target the template strand within the promoter region or early coding sequences to effectively block transcription initiation or elongation [1]. The identification of appropriate target sites begins with locating protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences adjacent to the target region, as the dCas9-sgRNA complex can only bind sequences with the appropriate PAM motif [18]. For the most commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide [18]. Computational tools are essential for designing high-quality sgRNAs with maximal on-target efficiency and minimal off-target effects. Machine learning platforms like sgDesigner have demonstrated superior performance in predicting sgRNA potency by analyzing sequence and structural features [19]. Additional specialized tools include CHOPCHOP for target site selection, Cas-OFFinder for off-target prediction, and Synthego's design tool which leverages a library of over 120,000 genomes across 8,300 species [18].

Core Component 2: dCas9 Scaffold

Characteristics and Engineering Variations

The catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) protein forms the central scaffold of the CRISPRi system, serving as a programmable DNA-binding platform without endonuclease activity. dCas9 is generated through point mutations in the RuvC (D10A) and HNH (H840A) nuclease domains of the native Cas9 protein, rendering it incapable of creating double-stranded DNA breaks while preserving its DNA-binding capability [4] [1]. This modified protein retains the ability to unwind DNA and form an R-loop structure upon sgRNA guidance, enabling precise positioning of fused effector domains at specific genomic loci. The dCas9-sgRNA complex binds to DNA in a PAM-dependent manner, with binding resulting in steric hindrance that physically blocks RNA polymerase binding or transcription elongation [1].

Recent engineering efforts have developed dCas9 variants with improved characteristics for metabolic engineering applications. These include high-fidelity dCas9 mutants with reduced off-target binding, dCas9 orthologs from different bacterial species with alternative PAM requirements to expand targeting range, and minimized dCas9 versions for improved delivery efficiency [1]. For multiplexed metabolic pathway engineering, the use of orthogonal dCas9 proteins—which recognize different PAM sequences and can function simultaneously without cross-talk—enables coordinated repression of multiple pathway genes.

Selection Criteria for Metabolic Pathway Engineering

Choosing the appropriate dCas9 variant depends on the specific requirements of the metabolic engineering project. The standard dCas9 from S. pyogenes offers reliable performance with well-characterized properties, while dCas12 variants (from Type V systems) provide distinct PAM preferences (5'-TTN-3') and different structural features that may be advantageous for certain targets [18]. Considerations include PAM availability near the target site, delivery constraints (vector size limitations), and the need for orthogonal systems in multiplexed applications. For industrial microbial hosts like Streptococcus thermophilus used in dairy production, codon optimization of dCas9 has been essential for achieving high expression levels and effective pathway repression [17].

Core Component 3: Transcriptional Repressors

Mechanism and Common Repression Domains

Transcriptional repressors fused to dCas9 constitute the functional effector module that executes gene silencing in CRISPRi systems. These protein domains directly interfere with transcription by various mechanisms, including steric obstruction of transcriptional machinery, recruitment of chromatin-modifying enzymes, or direct inhibition of RNA polymerase activity. The most widely used repressor domains for metabolic engineering include:

- KRAB (Krüppel-Associated Box): A potent repressor domain that recruits heterochromatin-forming complexes, leading to histone methylation (H3K9me3) and long-term stable silencing [4]

- Mxi1: A mammalian-derived repression domain that is part of the Mad-Max transcriptional repression complex

- SRDX (Super Repressor Domain X): A plant-optimized repressor effective in eukaryotic systems [4]

The fusion of these repressor domains to dCas9 typically occurs at the N- or C-terminus, with linker sequences optimized to maintain proper folding and functionality of both domains. Multiplexing different repressor domains on orthogonal dCas9 proteins can enable graded repression levels for fine-tuning metabolic pathways.

Table 2: Transcriptional Repressor Domains for Metabolic Engineering

| Repressor Domain | Origin | Mechanism of Action | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| KRAB | Mammals | Recruits histone methyltransferases; establishes heterochromatin | Stable, long-term repression in eukaryotic hosts [4] |

| Mxi1 | Mammals | Forms repression complexes; inhibits basal transcription machinery | Broad-spectrum repression in mammalian cells |

| SRDX | Plants | Recruits plant-specific corepressors; effective in plant systems | Metabolic engineering in crops and plant models [4] |

| SID4X | Synthetic | Four copies of the mSin3 interaction domain; strong repression | High-level silencing in yeast and mammalian systems |

Engineering Considerations for Repressor Efficiency

The effectiveness of dCas9-repressor fusions depends on several factors beyond the choice of repressor domain. The positioning and number of repressor domains significantly impact repression efficiency, with some architectures employing multiple copies of the same domain or combinations of different domains to achieve synergistic effects. Linker length and composition between dCas9 and the repressor domain must balance flexibility and rigidity to allow proper spatial orientation without compromising complex stability. For metabolic pathway optimization, the ability to tune repression strength is crucial, as complete silencing of essential pathway genes may be detrimental to host viability. Strategies for tunable repression include the use of degron tags for controlled protein stability, suboptimal sgRNA designs for reduced binding efficiency, and inducible expression systems that allow temporal control over dCas9-repressor production [20].

Integrated System for Metabolic Pathway Knockdown

Assembly and Delivery Strategies

The functional CRISPRi system requires coordinated expression of both dCas9-repressor fusion and sgRNA components. For metabolic engineering applications, delivery strategies must ensure stable maintenance and appropriate expression levels of both components throughout fermentation or production cycles. Common delivery approaches include:

- Plasmid-based expression: sgRNA sequences are cloned into plasmid vectors under RNA polymerase III promoters (U6, H1), while dCas9-repressor fusions are expressed from polymerase II promoters [18]. This approach allows stable maintenance in microbial systems but may cause burden in extended cultures.

- Chromosomal integration: For long-term, stable repression without selection pressure, both components can be integrated into the host genome at neutral sites [21]. Identification of reliable integration sites using tools like CRISPR-COPIES ensures consistent expression without disrupting native functions [21].

- Multiplexed systems: For simultaneous repression of multiple metabolic genes, sgRNA arrays can be constructed using tRNA processing systems or Csy4 endonuclease sites to produce multiple guide RNAs from a single transcript.

In the non-model yeast Rhodotorula toruloides, successful CRISPRi implementation has required specialized tool development, including the LINEAR system that packages both Cas9/gRNA expression and donor DNA in a single construct to overcome the organism's preference for non-homologous end joining [21].

Experimental Workflow for Metabolic Pathway Engineering

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for implementing CRISPRi-mediated metabolic pathway knockdown:

Application Case Study: EPS Optimization inStreptococcus thermophilus

A representative example of CRISPRi application in metabolic engineering is the optimization of exopolysaccharide (EPS) biosynthesis in Streptococcus thermophilus for improved dairy product quality [17]. In this study, multiplexed gene repression was employed to systematically manipulate uridine diphosphate (UDP) glucose sugar metabolism, redirecting precursor flux toward EPS production. The implementation involved:

- Target identification: Key genes in competing pathways (galE, pgmA, glmU) were selected for repression to enhance UDP-glucose and UDP-galactose precursor availability

- System design: A single plasmid system expressing dCas9-repressor and multiple sgRNAs targeting all selected genes simultaneously

- Evaluation: Repression efficiency was quantified via qRT-PCR, and metabolic flux changes were assessed through extracellular EPS quantification and sugar nucleotide profiling

- Optimization: Strains with varying combinations and strengths of repression were screened to identify optimal EPS production phenotypes

This approach demonstrated the power of CRISPRi for multiplexed metabolic engineering, enabling balanced pathway regulation without the need for sequential gene knockouts.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPRi Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Systems | pLenti-dCas9-KRAB, pORANGE template vector [22] | Provide optimized backbones for dCas9-repressor fusion construction |

| sgRNA Cloning Systems | Lenti-gRNA-Puro [19], BsmBI-digested backbones | Enable efficient sgRNA cloning and expression |

| Delivery Tools | Lentiviral packaging systems (psPAX2, pCMV-VSVG) [19], ELECTROcompetent cells | Facilitate host transformation with CRISPRi components |

| Validation Reagents | qPCR primers for target genes, RNA-seq libraries, metabolic profiling kits | Assess repression efficiency and metabolic outcomes |

| Specialized Tools | CRISPR-StAR [23] for complex screening, LINEAR for NHEJ-proficient hosts [21] | Address specific challenges in advanced applications |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Effective implementation of CRISPRi for metabolic pathway knockdown requires systematic optimization and problem-solving. Common challenges include:

- Incomplete repression: Can result from suboptimal sgRNA positioning, weak repressor domains, or insufficient dCas9 expression. Solutions include testing multiple sgRNAs targeting different regions of the promoter/gene, strengthening repressor domains, or increasing dCas9-repressor expression levels.

- Off-target effects: Addressed through improved sgRNA design using computational tools, high-fidelity dCas9 variants, and validation using RNA-seq to assess transcriptome-wide specificity.

- Host toxicity: May occur from metabolic burden of heterologous protein expression or unintended repression of essential genes. Strategies include promoter engineering to optimize expression levels, inducible systems to minimize burden during growth phases, and careful assessment of sgRNA specificity.

- Variable performance across hosts: Due to differences in codon usage, chromatin accessibility, or cellular machinery. Adaptation through codon optimization, testing of different repressor domains suited to the host, and validation of sgRNA accessibility through chromatin mapping.

For persistent issues, alternative approaches such as CRISPR-StAR—which uses internal controls generated by activating sgRNAs in only half the progeny of each cell—can overcome heterogeneity problems in complex screening scenarios [23].

Future Directions and Advanced Applications

The evolving frontier of CRISPRi technology for metabolic engineering includes several promising developments. Orthogonal CRISPRi systems employing multiple dCas9 variants with distinct PAM requirements will enable more sophisticated multiplexed pathway regulation [20]. Inducible and tunable systems using small molecule controls, light-sensitive domains, or temperature-sensitive components will provide dynamic control over metabolic fluxes in bioprocessing contexts [20]. Integration of machine learning and AI with sgRNA design and outcome prediction will further enhance the precision and efficiency of metabolic engineering efforts [19] [24]. As these tools mature, CRISPRi-mediated metabolic pathway knockdown will continue to transform industrial biotechnology, enabling more sustainable production of biofuels, specialty chemicals, and therapeutic compounds.

The core system components—sgRNA, dCas9, and transcriptional repressors—provide a powerful framework for metabolic pathway optimization. Through thoughtful design, strategic implementation, and continuous refinement, researchers can leverage these tools to address complex challenges in metabolic engineering and bioproduction.

The application of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for metabolic pathway knockdown represents a powerful approach for identifying gene essentiality and vulnerabilities in cellular metabolism. This technical guide outlines a systematic framework for selecting optimal metabolic genes for knockdown, focusing on dCas9 sgRNA design principles, experimental methodologies for combinatorial screening, and validation techniques to confirm metabolic impact. By integrating computational design with functional validation, researchers can effectively identify critical metabolic nodes in pathways such as glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, revealing dependencies that may inform therapeutic targeting in cancer and other diseases. This whitepaper serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in metabolic network analysis.

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has emerged as a powerful tool for probing metabolic network topology and identifying essential genes in various cellular contexts. Unlike CRISPR knockout approaches that introduce permanent DNA breaks, CRISPRi utilizes a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) protein fused to transcriptional repressors to downregulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence [4]. This reversible, tunable knockdown approach is particularly valuable for studying metabolic pathways where complete gene knockout may be lethal or compensated by network redundancies, allowing researchers to probe essential genes that would be impossible to study with conventional knockout techniques.

The foundation of successful metabolic vulnerability identification lies in understanding that metabolic networks are highly redundant at both the isozyme and pathway levels, enabling cells to remodel around single gene knockouts through compensatory mechanisms [25]. This redundancy represents a significant challenge in identifying true metabolic vulnerabilities, as conventional knockout screens may fail to reveal critical dependencies. Combinatorial CRISPR approaches that simultaneously target multiple genes have demonstrated that metabolic network topology can be elucidated through systematic pairwise gene targeting, revealing synthetic lethal interactions and critical nodes that control redox homeostasis and metabolic flux [25].

Fundamental Principles of dCas9 sgRNA Design

Core Components of CRISPRi System

The CRISPRi system consists of two fundamental components: the single guide RNA (sgRNA) and the deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) protein. The sgRNA is a chimeric RNA molecule comprising a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) component that provides target specificity through a 17-20 nucleotide complementary sequence, and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) that serves as a binding scaffold for the dCas9 protein [18]. The dCas9 protein lacks endonuclease activity due to mutations in its RuvC and HNH nuclease domains but retains its DNA-binding capability, enabling targeted transcriptional repression when directed to specific genomic loci by the sgRNA [4].

For effective transcriptional repression, the dCas9 protein is typically fused to repressive domains such as KRAB (Krüppel-associated box), which recruits chromatin-modifying enzymes to establish a repressive chromatin environment at the target locus. This targeted repression approach allows for reversible gene knockdown without permanent genetic alterations, making it particularly suitable for studying essential metabolic genes where permanent knockout would be cell-lethal [4].

Strategic Positioning for Metabolic Gene Knockdown

The positioning of sgRNAs relative to the transcription start site (TSS) of target metabolic genes is a critical determinant of knockdown efficiency. For CRISPRi applications, the optimal window for sgRNA binding is typically within -50 to +300 base pairs relative to the TSS [26]. This positioning ensures maximal interference with transcriptional initiation and early elongation, resulting in effective gene repression. Additionally, sgRNAs should be designed to avoid nucleosome-bound regions, as chromatin accessibility significantly impacts dCas9 binding efficiency [26].

Unlike CRISPR knockout approaches that can target exonic regions throughout the coding sequence, CRISPRi efficiency is highly dependent on proximity to the TSS, requiring careful annotation of TSS locations for each metabolic gene of interest. For metabolic pathway analysis, this often necessitates designing multiple sgRNAs against each target gene to account for potential alternative TSS usage in different cellular contexts or metabolic states [26] [4].

Computational sgRNA Design and Specificity Analysis

GuideScan2 for Enhanced Specificity

The design of high-specificity sgRNAs is paramount for reliable interpretation of metabolic knockdown experiments. GuideScan2 represents a significant advancement in gRNA design technology, utilizing a novel search algorithm based on the Burrows-Wheeler transform for memory-efficient, parallelizable construction of high-specificity CRISPR guide RNA databases [27]. This approach enables comprehensive off-target prediction while maintaining computational efficiency, addressing a critical limitation of earlier design tools that often failed to account for all potential off-target sites.

GuideScan2's algorithm constructs a lightweight genome index that facilitates exhaustive enumeration of off-target sites, accounting for mismatch tolerance and potential bulges in gRNA-to-DNA alignments [27]. This comprehensive specificity analysis is particularly important for metabolic studies, where off-target effects can confound results by indirectly impacting metabolic network states through unintended gene repression.

Design Parameters for Metabolic Gene Targeting

When designing sgRNAs for metabolic pathway knockdown, several key parameters must be considered to ensure optimal performance:

- GC Content: Maintain 40-80% GC content in the sgRNA sequence to ensure stability without excessive secondary structure formation [18]

- Specificity Score: Prioritize sgRNAs with high specificity scores (minimal off-target sites) using tools like GuideScan2 [27]

- PAM Consideration: Select appropriate protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences based on the dCas9 variant being used (typically 5'-NGG-3' for S. pyogenes dCas9) [18]

- Efficiency Prediction: Utilize algorithms that incorporate positional nucleotide preferences to maximize knockdown efficiency [26]

Recent analyses have revealed that sgRNAs with low specificity can produce confounding effects in CRISPRi screens, as dCas9 may become diluted across numerous off-target sites, reducing repression efficiency at the intended target [27]. This effect is particularly problematic in metabolic studies, where precise titration of gene expression may be necessary to observe phenotypic consequences.

Table 1: Comparison of sgRNA Design Tools for Metabolic Studies

| Tool | Key Features | Metabolic Application Strengths |

|---|---|---|

| GuideScan2 | Memory-efficient genome indexing, comprehensive off-target enumeration | Ideal for genome-wide metabolic screens; enables allele-specific targeting [27] |

| CHOPCHOP | Supports multiple Cas variants, efficiency prediction | Useful for designing sgRNAs against metabolic isozymes with different PAM requirements [18] |

| E-CRISP | Multi-species support, off-target filtering | Appropriate for metabolic studies in non-model organisms [26] |

| CRISPR Direct | Specificity-focused design, minimal off-targets | Suitable for targeting metabolic genes with paralogs to avoid cross-reactivity [26] |

Combinatorial Approaches for Metabolic Network Analysis

Dual-Gene Knockdown Strategies

Metabolic networks exhibit remarkable robustness due to redundant pathways and isozyme compensation, making combinatorial gene targeting particularly valuable for identifying vulnerabilities. Combinatorial CRISPRi enables systematic mapping of genetic interactions within metabolic networks by simultaneously repressing pairs of genes and quantifying fitness effects [25]. This approach has revealed that metabolic network topology contains numerous synthetic lethal interactions where simultaneous repression of two genes produces a severe fitness defect, while individual repressions are well-tolerated.

The implementation of combinatorial CRISPRi screening for metabolic studies involves designing a dual-sgRNA library targeting a selected set of metabolic genes, such as those encoding enzymes in glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and related pathways [25]. Each gene pair is typically targeted by multiple sgRNA combinations (e.g., 9 unique constructs per gene pair) to ensure statistical robustness and control for variable knockdown efficiencies [25]. This approach enables the calculation of both individual gene fitness scores (fg) and genetic interaction scores (πgg), providing a comprehensive view of metabolic network structure and dependencies.

Identifying Critical Metabolic Nodes

Combinatorial CRISPRi screens in cancer cell lines have identified several critical nodes in carbohydrate metabolism that represent potential vulnerabilities. Key findings include:

- GAPDH, G6PD, and PGD emerge as critical for cellular growth due to their central roles in maintaining redox homeostasis [25]

- Isozyme families (e.g., hexokinases, aldolases) often display a dominant member with greater indispensability (e.g., HK2, ALDOA) [25]

- Redox-associated genes typically have numerous genetic interactions, reflecting their importance in coordinating metabolic flux [25]

- The KEAP1-NRF2 signaling axis influences dependence on oxidative pentose phosphate pathway genes for NADPH production [25]

These findings demonstrate how combinatorial CRISPRi can reveal context-specific dependencies in metabolic networks, information that is crucial for developing targeted therapeutic strategies, particularly in cancer metabolism.

Table 2: Metabolic Gene Categories for Combinatorial Screening

| Metabolic Pathway | Key Genes to Target | Expected Phenotypic Readouts |

|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | HK2, PFKL, ALDOA, PGK1, PKM | Growth rate, glucose consumption, lactate production [25] |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway | G6PD, PGD, TALDO1 | NADPH/NADP+ ratio, oxidative stress sensitivity, nucleotide levels [25] |

| Antioxidant Response | NRF2 targets, glutathione synthesis genes | ROS levels, sensitivity to oxidative stress, glutathione levels [25] |

| Mitochondrial Metabolism | IDH1/2, SDH subunits, PDH family | Oxygen consumption rate, TCA metabolite levels [25] |

Experimental Workflow for Metabolic Vulnerability Identification

Experimental Workflow for Metabolic Vulnerability Identification

Library Design and Construction

The experimental workflow begins with careful selection of target metabolic pathways and genes based on transcriptomic data, known biology, and research objectives. For a focused metabolic screen, 50-100 genes encompassing multiple interconnected pathways (e.g., glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle) provides sufficient coverage to map network interactions while maintaining practical screen size [25]. Following gene selection, sgRNAs are designed using tools such as GuideScan2, with 3-4 sgRNAs per gene to account for variable efficiency, plus appropriate control sgRNAs (non-targeting, safe-harbor targeting) [27].

The dual-sgRNA library construction involves synthesizing oligonucleotide arrays containing all sgRNA combinations, which are then cloned into a lentiviral vector system [25]. For combinatorial screens, each gene pair is represented by multiple unique sgRNA combinations (typically 9 constructs per pair) to ensure statistical robustness [25]. Quality control steps including next-generation sequencing of the library plasmid pool are essential to verify representation and sequence integrity before proceeding to cellular experiments.

Cell Line Engineering and Screening

Cell lines are engineered to stably express dCas9-KRAB or similar repressive fusion proteins, followed by lentiviral transduction with the sgRNA library at appropriate multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA combination [25]. Following selection, cells are maintained in culture for multiple generations (typically 3-4 weeks) with periodic sampling to track sgRNA abundance dynamics [25].

Fitness measurements are derived from sgRNA abundance changes over time, quantified through next-generation sequencing of integrated sgRNA sequences at multiple timepoints [25]. These quantitative fitness measurements enable calculation of both individual gene essentiality and genetic interaction scores, identifying synthetic lethal/sick interactions that represent potential metabolic vulnerabilities.

Validation and Hit Confirmation

Metabolic Flux Analysis

Candidate vulnerabilities identified through CRISPRi screening require validation using orthogonal methods, particularly metabolic flux analysis. Stable isotope tracing with (^{13})C-labeled glucose or other nutrients provides direct measurement of pathway usage and redistribution following target gene repression [25]. For example, repression of oxidative PPP genes should result in decreased (^{13})C incorporation into nucleotide ribose rings, while compensatory flux through alternative NADPH-producing pathways may be observed through distinct labeling patterns.

Additional validation methods include:

- Seahorse extracellular flux analysis for real-time measurement of glycolytic and mitochondrial function

- LC-MS metabolomics to quantify changes in metabolite pool sizes

- NADPH/NADP+ and GSH/GSSG ratios to assess redox state alterations

- Biomass composition analysis to evaluate impacts on nucleotide, lipid, and protein biosynthesis

Mechanistic Follow-up Studies

Following initial validation, mechanistic studies elucidate how identified vulnerabilities function within specific metabolic contexts. For example, the discovery that KEAP1-NRF2 status influences dependence on oxidative PPP genes revealed that tumors with KEAP1 mutations upregulate alternative NADPH-producing pathways, making them less dependent on traditional PPP flux [25]. Such context-dependencies are critical for developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Additional mechanistic insights can be gained through:

- Time-resolved repression to map adaptive metabolic responses

- Combination studies with metabolic inhibitors or nutrient restriction

- Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses to identify compensatory regulatory changes

- Xenograft models to validate vulnerabilities in vivo

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic CRISPRi Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Systems | dCas9-KRAB lentiviral vectors | Provides transcriptional repression machinery for CRISPRi screens [4] |

| sgRNA Library Resources | Custom oligonucleotide arrays, lentiviral cloning systems | Enables construction of targeted or genome-wide sgRNA libraries [25] |

| Cell Line Models | HeLa, A549, patient-derived organoids | Provide relevant metabolic contexts for vulnerability identification [25] |

| Metabolic Assays | Seahorse XF Analyzers, stable isotope tracers ((^{13})C-glucose) | Validates metabolic phenotypes and measures flux alterations [25] |

| Analytical Platforms | LC-MS systems, next-generation sequencers | Quantifies metabolites and sgRNA abundance for fitness calculations [25] |

The strategic selection of metabolic pathway genes for knockdown through CRISPRi requires integration of sophisticated computational design, combinatorial screening approaches, and rigorous metabolic validation. By implementing the frameworks and methodologies outlined in this technical guide, researchers can systematically identify authentic metabolic vulnerabilities that may be exploited for therapeutic purposes. The continuing evolution of sgRNA design tools, particularly with advancements like GuideScan2, promises to further enhance the specificity and reliability of metabolic CRISPRi screens, accelerating the discovery of critical metabolic dependencies in cancer and other diseases.

The advent of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) technology, utilizing a catalytically inactive "dead" Cas9 (dCas9), has revolutionized metabolic engineering and functional genomics. Unlike editing tools that create permanent DNA breaks, dCas9 functions as a programmable transcriptional repressor by sterically blocking RNA polymerase, allowing for precise, reversible knockdown of target genes without altering the DNA sequence [28] [29]. This capability is particularly powerful for modulating metabolic pathways, where fine-tuning gene expression, rather than complete knockout, is often required to optimize flux toward desired compounds and avoid accumulation of toxic intermediates. The application of dCas9 for metabolic regulation, however, is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Its success is profoundly influenced by species-specific factors, including microbial physiology, endogenous metabolic network architecture, and genetic tool compatibility. This guide details the critical technical considerations and methodologies for implementing effective, species-tailored dCas9 strategies for metabolic pathway knockdown.

Foundational Principles of dCas9 and CRISPRi

Core Mechanism of Transcriptional Repression

The dCas9 protein, guided by a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), binds to specific DNA sequences but cannot cleave the target. Repression occurs through two primary mechanisms:

- Targeting Transcriptional Initiation: When the dCas9-sgRNA complex binds within a promoter region (e.g., the -10 or -35 boxes), it physically prevents the binding and initiation of RNA polymerase. This is typically the most effective strategy for strong gene repression [29].

- Targeting Transcriptional Elongation: Binding the dCas9 complex to the coding sequence of a gene can block the progression of RNA polymerase during transcription. While effective, this blockage can sometimes be bypassed, leading to incomplete repression [29].

The Critical Role of PAM Sequence Compatibility

A fundamental constraint of the CRISPR-Cas9 system is the requirement for a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), a short DNA sequence adjacent to the target site, which is essential for initial DNA recognition. The most common PAM for the Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 is 5'-NGG-3'. This requirement dictates which genomic loci can be targeted and is a major source of species-specific design challenges. Research has shown that dCas9 can exhibit more flexible PAM recognition (e.g., NNG or NGN) compared to the nuclease-active Cas9, expanding the potential target space, though with varying efficiencies [29]. The selection of sgRNAs is therefore entirely dependent on the PAM sequences available in the target organism's genome.

Species-Specific Metabolic and Genetic Landscapes

Analyzing Metabolic Network Architecture

Effective metabolic engineering requires a systems-level understanding of the host's native metabolic network. Publicly available databases are indispensable for this initial analysis. The table below summarizes key pathway databases for mapping species-specific metabolisms.

Table 1: Key Metabolic Pathway Databases for Species-Specific Analysis

| Database Name | Key Features | Application in dCas9 Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG [30] [31] | One of the most complete databases; contains >700 species and 372 reference pathways. | Identify target genes within metabolic pathways (e.g., for SAF precursors in Pseudomonas putida [16] or EPS in Streptococcus thermophilus [17]). |

| MetaCyc [31] | A database of nonredundant, experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways from >1,500 species. | Access curated, experimentally validated pathways for accurate gene target identification. |

| Reactome [31] [32] | A curated, peer-reviewed knowledgebase with pathway data for >20 species, focused on Homo sapiens. | Essential for human metabolic studies and drug development research. |

| BioCyc [31] | A collection of 371 Pathway/Genome Databases (PGDBs), each for a single species. | Obtain a dedicated, organism-specific database for comprehensive gene-reaction-metabolite mapping. |

Advanced tools like MetaDAG can further reconstruct and analyze metabolic networks from KEGG data. MetaDAG computes a reaction graph and then simplifies it into a metabolic Directed Acyclic Graph (m-DAG) by collapsing strongly connected components, providing a high-level topological view that reveals key choke points and regulatory nodes ideal for dCas9 targeting [30].

Case Studies in Diverse Species

- Pseudomonas putida: This bacterium is a promising chassis for bioproduction, such as sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) precursors. A key study used predictive CRISPRi to systematically identify and downregulate target genes, leading to enhanced production of isoprenol. This highlights the need for pre-designed sgRNA libraries tailored to the host's metabolic network [16].

- Streptococcus thermophilus: In this dairy bacterium, multiplex CRISPRi was successfully applied to repress several genes in the uridine diphosphate glucose sugar metabolism pathway. This coordinated repression optimized exopolysaccharide (EPS) biosynthesis, demonstrating the power of dCas9 for balancing flux in tightly regulated primary metabolic pathways [17].

- Human Gut Microbiome (Gammaproteobacteria): A major challenge in complex communities is restricting dCas9 activity to only metabolically relevant species. Researchers ingeniously re-purposed the endogenous GusR transcription factor to create a glucuronide-inducible dCas9 system. This system ensured that dCas9 was only expressed in bacteria possessing glucuronide-utilization enzymes (GUS), precisely targeting the pathway of interest and minimizing off-target effects in other community members [28].

Implementing Species-Tailored dCas9 Systems

Designing the dCas9 Expression System

Constitutive, high-level expression of dCas9 can be toxic to cells, leading to fitness costs and counter-selection [28]. Therefore, inducible promoters (e.g., L-arabinose-inducible PBAD [29]) are strongly recommended for tight control over the timing and level of dCas9 expression. For maximal precision, especially in synthetic biology or therapeutic applications, dCas9 expression can be placed under the control of metabolite-responsive biosensors. As demonstrated with the GUS system, this links dCas9 activity directly to the metabolic state of the cell, enabling autonomous, pathway-specific regulation [28].

sgRNA Design and Validation

sgRNA design is the most critical step for ensuring high on-target efficiency and low off-target effects. The following workflow, implemented in E. coli for galactose metabolism control, provides a robust protocol [29].

Table 2: Key Reagents for dCas9-Mediated Metabolic Repression Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Plasmid | Expresses the catalytically dead Cas9 protein. | Chromosomally integrated PBAD-dCas9 in E. coli [29]. |

| sgRNA Expression Vector | Expresses the target-specific guide RNA. | High-copy plasmid with constitutive promoter [29]. |

| Inducer Molecule | Controls the timing of dCas9 expression. | L-arabinose for the PBAD promoter [29]. |

| Metabolite Biosensor | Enables metabolite-responsive dCas9 expression. | GusR regulator and glucuronide inducers for GUS-positive bacteria [28]. |

| RT-qPCR Assays | Quantitatively measures changes in target gene mRNA levels. | Used to confirm ~100-fold decrease in gusA transcription [28]. |

Advanced Strategies and Future Outlook

The future of species-specific dCas9 application lies in moving beyond single-gene repression toward multiplexed and integrated systems. The ability to simultaneously repress multiple genes within a pathway, as shown in S. thermophilus [17], is key to tackling complex metabolic engineering challenges. Furthermore, the integration of dCas9 with other omics technologies is powerful. For instance, MetaboAnalyst offers robust statistical and functional analysis tools for metabolomics data, allowing researchers to correlate dCas9-induced transcriptional changes with resulting metabolic phenotypes and validate the impact of their interventions [33].

Emerging technologies like CRISPR activation (CRISPRa), which uses dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators to upregulate gene expression, can be combined with CRISPRi to simultaneously repress competitive pathways and enhance desired biosynthetic routes [4]. Finally, the development of novel computational platforms, such as AI-driven foundation models for predicting optimal guide RNA and enzyme combinations, promises to move the field from trial-and-error to rational, predictive design [14].

Strategic sgRNA Design: A Step-by-Step Protocol for Targeting Metabolic Gene Promoters

The CRISPR/dCas9 (catalytically dead Cas9) system has revolutionized metabolic pathway engineering by enabling precise, programmable transcriptional regulation without altering the underlying DNA sequence. For research focused on metabolic pathway knockdown, this technology is indispensable for systematically modulating gene expression to optimize biosynthetic outputs. The core of the CRISPR/dCas9 system consists of two components: a guide RNA (gRNA) that specifies the target DNA sequence and the dCas9 protein, which binds to the DNA but lacks nuclease activity [1]. A critical determinant of successful targeting is the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM)—a short, specific DNA sequence immediately adjacent to the target site that the dCas9 protein must recognize to initiate binding [34]. The PAM requirement is not merely a formality; it is a fundamental constraint that defines the targeting scope of any CRISPR-based experiment. The PAM sequence functions as a binding signal, and its recognition by dCas9 triggers local DNA unwinding, allowing the gRNA to hybridize with the target protospacer [35]. The inherent PAM specificity of wild-type dCas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), which requires a 5'-NGG-3' PAM, limits the fraction of the genome that can be targeted, especially for applications like base editing or transcriptional repression that require precise positioning relative to the transcriptional start site [36]. Consequently, selecting a dCas9 variant with appropriate PAM compatibility is the most critical initial step in designing effective metabolic pathway knockdown experiments, as it directly dictates which genomic loci are accessible for engineering.

Understanding PAM Requirements and dCas9 Variants

The Biological Function of the PAM Sequence

The PAM sequence serves as a fundamental "self" versus "non-self" discrimination mechanism for the CRISPR-Cas system in its native bacterial context. When a bacterium survives a viral infection, it incorporates a fragment of the viral genome (a protospacer) into its own CRISPR array as a genetic memory. During subsequent infections, the Cas9 nuclease uses RNA transcripts from this array to identify and cleave matching viral DNA. The PAM is essential for this process because it allows Cas9 to distinguish between invading viral DNA (which contains the PAM) and the bacterium's own CRISPR array (which lacks the PAM), thus preventing auto-immunity [34]. In engineered CRISPR/dCas9 systems for eukaryotic cells, this biological constraint translates into a technical requirement: any target site must be followed by the specific PAM sequence recognized by the dCas9 variant in use. For instance, when using wild-type SpdCas9, the target sequence must be adjacent to an NGG PAM, where "N" is any nucleotide base. The binding of the dCas9/sgRNA complex to a target gene based on this PAM recognition can then be leveraged for transcriptional interference, effectively knocking down gene expression for metabolic pathway engineering [1].

Catalog of dCas9 Variants and Their PAM Specificities

The limitations of wild-type SpCas9's NGG PAM have driven the discovery of natural orthologs and the engineering of novel variants with altered PAM specificities. The following table provides a comparative overview of key dCas9 variants, their PAM requirements, and primary characteristics relevant to selection for metabolic pathway knockdown.

Table 1: PAM Sequences and Characteristics of Common dCas9 Variants

| dCas9 Variant | Source Organism | PAM Sequence (5' to 3') | Size (aa) | Key Characteristics and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpdCas9 (Wild-type) | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG [34] [35] | 1368 | The canonical workhorse; well-characterized but has a large size and limited PAM scope. |

| xCas9 (Evolved) | Engineered from SpCas9 | NG, GAA, GAT [36] [35] | 1368 | Evolved via PACE; offers broad PAM compatibility and higher DNA specificity than SpCas9 [36]. |

| SpRY (Engineered) | Engineered from SpCas9 | NRN > NYN (Nearly PAM-less) [35] | 1368 | Extremely relaxed PAM requirement, greatly expanding potential target sites [37] [35]. |

| SadCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT (or NNGRRN) [34] [38] | 1053 | Small size ideal for AAV delivery; used in neuronal and liver-specific studies in vivo [38]. |

| NmCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNGATT [34] | 1082 | Longer PAM sequence can enhance specificity but reduces potential target site density. |