Overcoming Crosstalk in Synthetic Genetic Circuits: Strategies for Precision Engineering and Therapeutic Applications

Crosstalk in synthetic genetic circuits—the unintended interference between circuit components and native cellular processes—poses a significant barrier to their reliable application in biomedicine and biotechnology.

Overcoming Crosstalk in Synthetic Genetic Circuits: Strategies for Precision Engineering and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

Crosstalk in synthetic genetic circuits—the unintended interference between circuit components and native cellular processes—poses a significant barrier to their reliable application in biomedicine and biotechnology. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational causes of crosstalk, from resource competition to context dependency. It reviews emerging methodological solutions, including the use of orthogonal parts, advanced circuit design, and novel computational frameworks like synthetic biological operational amplifiers. The content further details troubleshooting and optimization protocols to enhance circuit performance and stability, and concludes with an examination of validation techniques and comparative analyses of different engineering approaches. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to build more predictable and robust genetic systems for next-generation therapeutics.

Understanding the Roots of Crosstalk: Foundational Challenges in Circuit Design

In synthetic biology, crosstalk refers to the unintended interactions that compromise the functionality, predictability, and stability of engineered genetic circuits. These interactions can be categorized into three main types: molecular off-target interactions between genetic components, resource competition for shared cellular machinery, and the systemic stress induced by metabolic burden. Understanding and mitigating crosstalk is critical for constructing robust, complex synthetic biological systems for research and therapeutic applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary types of crosstalk in synthetic genetic circuits?

Answer: Crosstalk in synthetic genetic circuits primarily manifests in three forms:

- Molecular Off-Target Interactions: Unintended binding or activation between non-cognate components. For example, in quorum-sensing systems, a signal molecule from one pathway (e.g., LuxI) may inadvertently activate a different receptor (e.g., LasR), a phenomenon confirmed as "signal crosstalk" [1].

- Resource Competition: Circuits compete for the cell's finite pool of essential resources, such as ribosomes, RNA polymerases, nucleotides, and amino acids. This competition can alter intended circuit dynamics and lead to performance degradation [2] [3].

- Metabolic Burden: The cumulative stress from expressing synthetic genes drains cellular energy and resources, triggering global stress responses that slow growth, impair native protein synthesis, and reduce overall circuit performance [2].

FAQ 2: My genetic circuit's output is weaker than expected, and host cell growth is slow. What is the cause?

Answer: This is a classic symptom of high metabolic burden. The expression of your synthetic circuit is consuming excessive cellular resources, leading to a competition for ribosomes and amino acids. This can activate the stringent response, a major stress mechanism triggered by the depletion of charged tRNAs, which globally reprograms cell metabolism away from growth and division [2].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Measure Growth Rate: Quantify the growth curve of your engineered strain compared to a wild-type or empty vector control. A significant reduction in growth rate is a strong indicator of metabolic burden.

- Tune Expression Levels: Reduce the strength of your circuit's expression. This can be achieved by:

- Using weaker promoters or Ribosome Binding Sites (RBS).

- Lowering the copy number of your plasmid.

- Using inducible systems and identifying the minimal inducer concentration that provides sufficient output.

- Consider a Multi-Cellular Solution: Distribute the genetic load of a complex circuit across different cell populations in a consortium. This multicellular control architecture can enhance modularity and improve overall system performance and reliability [4].

FAQ 3: How can I make my biosensor specific when sensing molecules cause cross-activation?

Answer: This issue, known as lack of orthogonality, is common in systems sensing multiple similar molecules. Instead of trying to insulate the pathways completely, a powerful strategy is to design a circuit that actively compensates for the crosstalk at the network level [5] [6].

Experimental Protocol: Crosstalk Compensation Circuitry

This methodology is based on engineering circuits to integrate and subtract signals, thereby canceling out interference [5] [6].

- Objective: To create a gene network that accurately senses a target input in the presence of a crosstalk-inducing input.

Key Components:

- Sensor A: The primary sensor for your target molecule, which also exhibits crosstalk with an interfering molecule.

- Sensor B: A sensor that is specifically activated by the interfering molecule but does not respond to your target.

- Actuator: A genetic output (e.g., fluorescent protein) controlled by a promoter regulated by both sensors.

Procedure:

- Quantitatively Map Crosstalk: Characterize the input-output transfer curves for Sensor A and Sensor B against both the target and interfering molecules. Precisely measure the degree to which the interfering molecule activates Sensor A [5].

- Design a Compensation Circuit: Design a circuit where the output from Sensor B (specific to the interference) is used to subtract the crosstalk signal from the output of Sensor A. This can be implemented using an operational amplifier (OA) inspired circuit that performs a mathematical operation like

Output = α·Signal_A - β·Signal_B[6]. - Implement and Validate: Build the compensation circuit and test its performance in the presence of both the target and interfering molecules. The ideal result is an output that depends only on the concentration of the target molecule, with minimal influence from the interferer [5] [6].

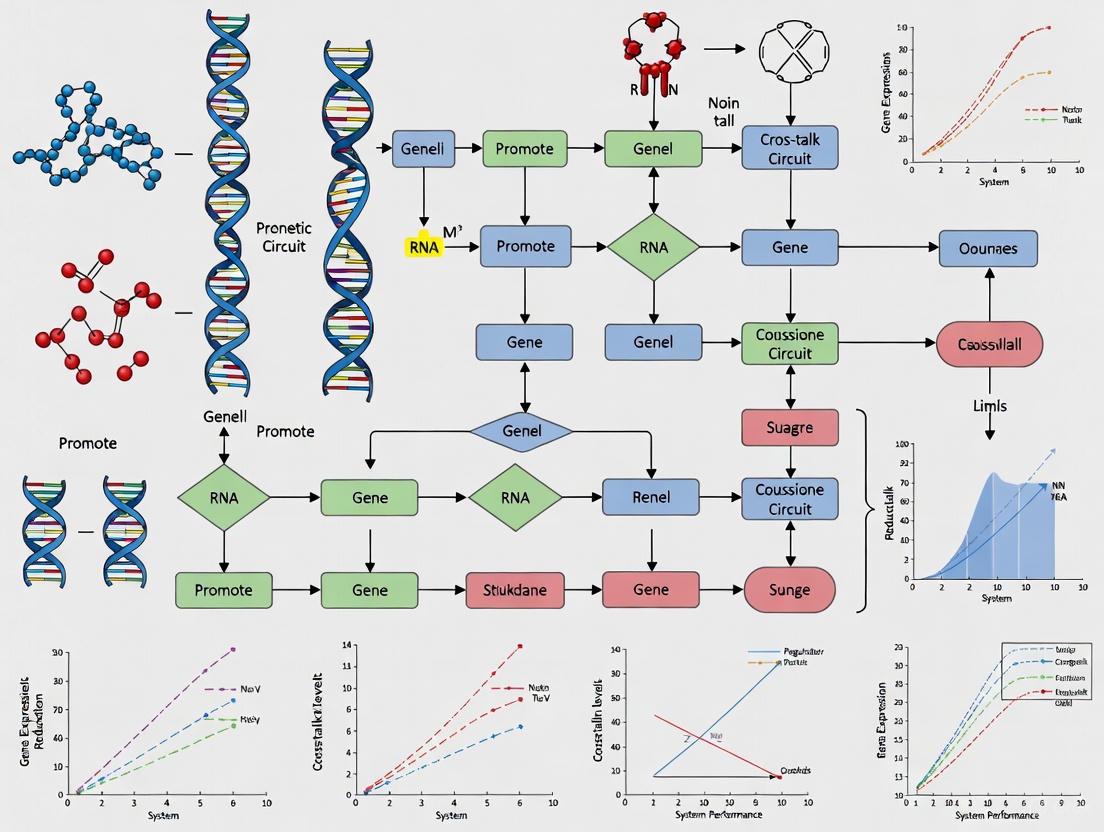

Visualization of the Crosstalk Compensation Concept:

FAQ 4: How does host organism selection affect circuit crosstalk and performance?

Answer: The host organism, or chassis, is not a passive container but an active module that significantly influences circuit behavior—a phenomenon known as the "chassis effect" [3]. Different hosts have varying:

- Resource Allocation Pools: The availability of RNA polymerases, ribosomes, and metabolites differs between species [3].

- Endogenous Regulatory Networks: Your synthetic transcription factors may interact with the host's native regulators, causing off-target activation or repression [3].

- Innate Metabolic Objectives: Some microbes are optimized for rapid growth, while others prioritize resource efficiency or stress survival, affecting how they handle synthetic circuit expression [7].

Recommendation: For applications requiring high reliability, consider adopting a Broad-Host-Range (BHR) synthetic biology approach. By testing your genetic circuit in several different, well-characterized host organisms, you can select the chassis that provides the best performance and lowest crosstalk for your specific application [3].

Quantitative Data and Analysis

Table 1: Quantifying Sensor Crosstalk and Compensation Performance

Data derived from reactive oxygen species (ROS) sensor experiments, demonstrating crosstalk quantification and the efficacy of compensation circuits [5].

| Sensor Type | Target Input | Interfering Input | Output Fold-Induction (Target Only) | Output Fold-Induction (with Interference) | Performance Metric (Utility) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O2 Sensor (OxyR) | H2O2 | Paraquat | 23.6x | Not Explicitly Stated | 1486.8 |

| Paraquat Sensor (SoxR) | Paraquat | H2O2 | 42.3x | Not Explicitly Stated | 4052.3 |

| Dual-Sensor Strain | H2O2 | Paraquat | N/A | Significant Crosstalk Reported | N/A |

| Crosstalk-Compensated Network | H2O2 | Paraquat | N/A | Reduced Crosstalk | N/A |

Table 2: Impact of Resource Utilization on Microbial Community Stability

Analysis of synthetic microbial communities shows how narrow-spectrum resource utilization reduces competition and enhances stability [8].

| Bacterial Strain | Resource Utilization Width | Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) | Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulosimicrobium cellulans E | 13.10 (Narrow) | 0.51 (Low) | High |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri G | 25.59 (Narrow) | Not Specified | High |

| Bacillus megaterium L | 36.76 (Broad) | 0.74 (High) | Low |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring and Alleviating Metabolic Burden

A. Quantifying Burden via Growth Kinetics:

- Inoculate two cultures: one with the engineered circuit and a control with an empty plasmid.

- Grow the cultures in appropriate media, ensuring the inducer is added if needed.

- Monitor the optical density (OD600) at regular intervals.

- Calculate the maximum growth rate (μmax) and the final biomass yield for both cultures. A significant reduction in either parameter for the engineered strain indicates metabolic burden [2].

B. Strategies for Burden Mitigation:

- Promoter and RBS Engineering: Switch to weaker, more tunable promoters and RBS sequences to lower protein expression to the minimal required level [2].

- Dynamic Regulation: Implement circuits that only activate the metabolic pathway under specific conditions, thereby avoiding constant resource drain [6].

- Chromosomal Integration: Where possible, integrate genes into the host chromosome to avoid the high copy number and associated load of plasmids [2].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Synthetic Biological Operational Amplifier (OA)

Objective: To decompose non-orthogonal biological signals into orthogonal components using a synthetic OA circuit [6].

Circuit Design:

- Select Orthogonal Regulator Pairs: Use transcription-translation pairs such as σ/anti-σ factors or T7 RNAP/T7 lysozyme for their linear and orthogonal interactions.

- Configure the OA Circuit: Design an open-loop circuit where:

- Input X1 drives production of an Activator (A).

- Input X2 drives production of a Repressor (R).

- Tune Parameters: Use RBS engineering to adjust the translation rates (r1, r2) of the activator and repressor to set the coefficients α and β for the operation

X_E = α·X1 - β·X2. - Output Module: The effective activator concentration (X_E) drives an output promoter, producing a measurable signal (e.g., fluorescence) [6].

Workflow Diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Crosstalk Mitigation Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example(s) from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors | Provides specific, non-interfering regulation pathways. | ECF σ/anti-σ factor pairs; T7 RNAP/T7 lysozyme [6]. |

| Tunable Expression Systems | Allows precise control over gene expression levels to minimize burden. | IPTG-inducible PLac system; anhydrotetracycline-inducible PTet system [9]. |

| Broad-Host-Range (BHR) Vectors | Enables testing of genetic circuits across diverse microbial chassis. | Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA) plasmids [3]. |

| Crosstalk-Compensation Circuit Motifs | Genetically encodes signal processing to subtract interference. | Circuits performing α·Input_A - β·Input_B operations [5] [6]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational models to predict metabolic burden and resource competition. | Used to calculate Metabolic Resource Overlap (MRO) and Metabolic Interaction Potential (MIP) [8]. |

| AChE-IN-57 | AChE-IN-57, MF:C17H22ClN5, MW:331.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Crm1-IN-3 | Crm1-IN-3 is a cell-permeable CRM1 inhibitor for cancer research. It blocks nuclear export by targeting the NES-binding cleft. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The Impact of Host Cellular Context and Environmental Variability on Circuit Fidelity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is "circuit fidelity" and why is it a problem in synthetic biology? Circuit fidelity refers to the ability of a synthetic gene circuit to maintain its intended function and output over time and across different cellular environments. A core challenge is that gene circuits do not operate in a vacuum; their function is intricately linked to the host cell's genetic background, physiology, and environment. This context dependence leads to unpredictable performance, lengthy design cycles, and limited deployment of synthetic biological constructs [10].

What are the main contextual factors that disrupt circuit function? Contextual factors can be divided into two primary groups:

- Individual Contextual Factors: These can independently influence gene expression and include factors like the specific genetic parts used, their orientation, and their syntax (order and arrangement on the DNA). These factors can introduce issues like retroactivity, where a downstream module interferes with an upstream one [10].

- Feedback Contextual Factors: These are systemic properties arising from complex interactions between the circuit and the host. The two most significant are:

- Growth Feedback: A multiscale loop where circuit activity consumes cellular resources, burdening the host and reducing its growth rate. This slower growth, in turn, alters the dilution rate of circuit components and the cell's physiological state, further impacting circuit behavior [10] [11].

- Resource Competition: Competition between the synthetic circuit and the host's native genes for a finite pool of shared cellular resources, such as RNA polymerases, ribosomes, nucleotides, and energy [10] [11]. In bacteria, competition for translational resources (ribosomes) is often the primary bottleneck, while in mammalian cells, competition for transcriptional resources (RNAP) is more dominant [10].

How does metabolic burden lead to evolutionary instability? Engineered circuits consume cellular resources, diverting them from host processes essential for growth and replication. This "burden" imposes a selective disadvantage on cells carrying the functional circuit. Over time, mutant cells that have acquired loss-of-function mutations in the circuit—and are therefore relieved of this burden—will outgrow and outcompete the original engineered cells. This evolutionary process leads to a progressive decline in the population-level output of the circuit [11].

What is orthogonality and how can it improve circuit performance? Orthogonality is a core design principle that involves using biological components (e.g., transcription factors, enzymes) from foreign organisms that interact strongly with each other but minimally with the host's native cellular processes. This reduces unintended cross-talk and interference, making the circuit's behavior more predictable and reliable. Examples include using bacterial transcription factors or CRISPR/Cas systems in plant or mammalian cells [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Declining Circuit Performance Over Time (Evolutionary Instability)

Potential Cause: Mutant cells with non-functional circuits are taking over your culture due to the metabolic burden imposed by your circuit.

Solutions:

- Implement Genetic Controllers: Integrate feedback control systems that regulate circuit activity.

- Strategy: Use a "host-aware" computational framework to design controllers that sense circuit output or host growth rate and adjust expression accordingly. Simulations suggest that post-transcriptional controllers (e.g., using small RNAs) can outperform transcriptional ones, and growth-based feedback can extend the functional half-life of a circuit [11].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Modeling: Develop an ordinary differential equation (ODE) model coupling your circuit's dynamics with host growth and resource pools. Incorporate mutation rates and population dynamics.

- Controller Design: Model different controller architectures (e.g., negative autoregulation, growth-rate sensing). Evaluate them using metrics like τ±10 (time until output deviates by 10%) and τ50 (functional half-life).

- Implementation: Genetically implement the top controller designs. For growth-based feedback, this could involve linking the expression of a key circuit component to a promoter sensitive to the host's growth state.

- Validation: Conduct long-term serial passaging experiments, measuring both population-level output (e.g., total fluorescence) and culture growth. Use flow cytometry to track the distribution of performance across individual cells over time [11].

- Reduce Burden by Optimizing Expression: Avoid unnecessarily high expression levels. Use promoters and RBSs that provide sufficient, but not excessive, expression of your circuit genes to minimize resource drain [10].

Problem: Unintended Interactions Between Circuit Modules

Potential Cause: Resource competition or retroactivity between modules is causing cross-talk and altering expected behaviors.

Solutions:

- Characterize Resource Competition:

- Experimental Protocol: To quantify the load on transcriptional resources, you can use a fluorescent RNA polymerase (RNAP) sensor. To assess translational resource (ribosome) load, employ a dual-fluorescence reporter system where one reporter is constitutively expressed and the other is induced with your circuit. A drop in the constitutive reporter's output upon circuit induction indicates competition for ribosomes [10].

- Insulate Modules:

Problem: Inconsistent Circuit Behavior Between Different Host Strains or Growth Conditions

Potential Cause: Host-specific factors and environmental variability are altering circuit context.

Solutions:

- Adopt Host-Aware Design:

- Strategy: Use mathematical models that explicitly include the host's resource pools and growth dynamics, rather than modeling the circuit in isolation [10].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Model Calibration: Measure key host parameters (e.g., growth rate, RNAP and ribosome levels) under your standard experimental conditions.

- Predictive Simulation: Run simulations to predict how your circuit will perform in a new host strain or a different medium before building it.

- Validation: Build and test the circuit in the new context to refine the model [10].

Quantitative Data on Circuit Stability

The following table summarizes key metrics for evaluating evolutionary longevity, derived from multi-scale modeling of engineered populations [11].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Quantifying Evolutionary Longevity

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Pâ‚€ | The initial total circuit output from the ancestral population prior to any mutation. | A measure of the circuit's initial performance. |

| τ±â‚â‚€ | The time taken for the total population output (P) to fall outside the range Pâ‚€ ± 10%. | A measure of short-term performance stability. |

| Ï„â‚…â‚€ | The time taken for the total population output (P) to fall below Pâ‚€/2. | A measure of long-term functional persistence or "half-life." |

Table 2: Controller Performance for Enhancing Evolutionary Longevity

| Controller Strategy | Sensed Input | Key Finding | Impact on Longevity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-circuit Feedback | Circuit's own output | Negative autoregulation can prolong short-term performance. | Improves τ±â‚â‚€ [11] |

| Growth-based Feedback | Host cell growth rate | Extends the functional half-life of the circuit. | Improves Ï„â‚…â‚€ [11] |

| Post-transcriptional Control | Circuit output / sRNAs | Outperforms transcriptional control due to an amplification step that reduces controller burden. | Improves both τ±â‚â‚€ and Ï„â‚…â‚€ [11] |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Resource Burden

Objective: To measure the translational burden imposed by a synthetic gene circuit on its host.

Materials:

- Strain 1: Host strain containing a constitutively expressed fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP).

- Strain 2: Host strain containing both the constitutive GFP reporter AND your synthetic gene circuit.

- Control Strain: Host strain with no fluorescent reporters or circuits.

- Equipment: Flow cytometer or microplate reader, shaker incubator.

Method:

- Inoculate triplicate cultures of each strain in the appropriate medium.

- Grow cultures to mid-exponential phase.

- If your circuit is inducible, add the inducer to Strain 2 and continue incubation for a set period.

- Measure the optical density (OD) and fluorescence (GFP) of all cultures.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the mean fluorescence intensity per OD unit for each strain.

- Normalize the fluorescence of Strain 1 (GFP only) and Strain 2 (GFP + Circuit) to the Control Strain (no fluorescence).

- A significant decrease in the normalized fluorescence of Strain 2 compared to Strain 1 indicates that your synthetic circuit is competing for and sequestering translational resources (ribosomes), thereby reducing the expression of the independent GFP reporter [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Application in Circuit Design |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors | TFs from other organisms (e.g., bacteria) that do not recognize host promoters. | Reduces cross-talk with host regulatory networks; core to building insulated circuits [12]. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 System | Catalytically "dead" Cas9 for programmable transcriptional regulation. | Used as an actuator in circuits to repress or activate endogenous genes without cleavage [12]. |

| Site-Specific Recombinases | Enzymes (e.g., from bacteriophage) that catalyze precise DNA rearrangement. | Used to build permanent genetic memory switches and logic gates [12]. |

| Dual-Fluorescence Reporter System | Two independent fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP). | One reporter acts as a circuit output, the other as an internal control to quantify resource competition and burden [10]. |

| Small RNAs (sRNAs) | Short, non-coding RNA molecules. | Used for post-transcriptional regulation in feedback controllers; can provide strong control with low burden [11]. |

| SBOL (Synthetic Biology Open Language) | A standardized data model for representing genetic designs. | Facilitates the exchange, storage, and reproduction of complex genetic circuit designs between researchers and software tools [13]. |

| Boc-QAR-pNA | Boc-QAR-pNA, MF:C25H39N9O8, MW:593.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Maoa-IN-1 | Maoa-IN-1, MF:C13H16Cl2N2O2, MW:303.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Limitations of Traditional Binary (ON/OFF) Logic in Complex Biological Environments

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my genetic circuit, which works perfectly in vitro, show high background noise (leakiness) and low dynamic range in a cellular environment?

Traditional binary logic assumes a clean, isolated system. In a cell, your circuit competes for limited cellular resources like RNA polymerases, ribosomes, and nucleotides. This competition can cause unintended, low-level expression of your output gene even in the "OFF" state (leakiness) and prevent it from reaching a high level in the "ON" state (low dynamic range) [12] [14]. Furthermore, the cell's native regulatory machinery may have crosstalk with your synthetic components, further destabilizing its intended digital behavior [6].

2. My circuit is designed to process two independent signals, but they seem to interfere with each other. What is the cause of this crosstalk?

This is a classic problem of non-orthogonality [6]. Your synthetic components (e.g., transcription factors, promoters) may not be fully insulated from each other. For instance, a transcription factor from one input signal might weakly bind to the promoter intended for another signal. Biological signals are often multidimensional and overlapping, unlike the clean, separate inputs assumed by binary logic [6]. This inherent crosstalk in biological systems leads to unpredictable and erroneous outputs in your circuit.

3. How can I make my genetic circuit respond reliably to the complex, analog signals found in natural biological environments (e.g., tumor microenvironments)?

Binary ON/OFF switches are often insufficient for processing the gradient-based information (e.g., varying concentrations of metabolites, cytokines) found in vivo. A promising solution is to move beyond simple logic gates and implement circuits that can process and decompose complex signals [6]. Frameworks inspired by synthetic biological operational amplifiers (OAs) can be engineered to perform linear operations like subtraction and scaling on input signals. This allows you to isolate a specific signal of interest from a background of noisy or overlapping inputs, enabling more precise and reliable control in complex environments [6].

4. What strategies can I use to reduce the metabolic burden and improve the long-term stability of my synthetic circuits?

A key principle is orthogonality—using genetic parts (e.g., bacterial transcription factors, CRISPR/Cas components) that interact strongly with each other but have minimal interaction with the host's native networks [12]. This reduces cross-talk and unintended side effects on host fitness. Additionally, consider using inducible systems that only activate the circuit when needed, rather than constitutive "always-on" expression [12]. For long-term stability, minimize sequence homology and repetitive elements in your design to avoid homologous recombination and genetic instability [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Leakiness and Unintended Activation

Possible Cause #1: Resource competition and burden. The host cell's machinery is overwhelmed by the synthetic circuit.

- Solution: Implement an orthogonal chassis. Use engineered transcriptional and translational machinery (e.g., T7 RNA polymerase systems, orthogonal ribosomes) that is dedicated to your circuit and does not compete with host genes [16] [6].

Possible Cause #2: Promoter crosstalk. Endogenous transcription factors are activating your synthetic promoter.

- Solution: Use highly specific, synthetic promoters. Design promoters de novo using computational tools, incorporating unique transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) not found in the host genome to ensure insulation [15].

Problem: Signal Crosstalk in Multi-Input Circuits

Possible Cause: Non-orthogonal regulatory components. The parts used for different inputs are biochemically similar and interfere.

- Solution: Deploy signal decomposition circuits. Engineer circuits based on synthetic operational amplifiers (OAs). These use orthogonal regulator pairs (e.g., σ/anti-σ factors) to perform mathematical operations on inputs, effectively separating intertwined signals [6]. The workflow below illustrates this framework for decomposing a 2-dimensional signal.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Orthogonal Signal Transformation (OST) Circuit

- Select Orthogonal Regulator Pairs: Choose independent σ/anti-σ factor pairs or other orthogonal transcriptional systems (e.g., dCas9 with specific gRNAs) [6] [17].

- Tune Circuit Parameters: Use Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) libraries to vary the translation rates (râ‚, râ‚‚) of the activator (A) and repressor (R) components. This tuning sets the coefficients (α, β) for the linear operation α·Xâ‚ - β·Xâ‚‚ performed by the OA circuit [6].

- Configure Feedback Loops: For enhanced stability, implement a closed-loop configuration with negative feedback to maintain output linearity and reduce noise [6].

- Validate with Fluorescent Reporters: Measure the input (Xâ‚, Xâ‚‚) and output (O) signals using normalized fluorescence. The output should follow the equation: O = (Oₘâ‚â‚“ · Xâ‚‘)/(Kâ‚‚ + Xâ‚‘), where Xâ‚‘ is the effective concentration (α·Xâ‚ - β·Xâ‚‚) [6].

Problem: Unreliable Performance in DynamicIn VivoEnvironments

Possible Cause: The binary circuit cannot adapt to changing physiological conditions (e.g., growth phase, nutrient availability).

- Solution: Integrate growth-state-responsive elements. Use promoters that are naturally active during specific growth phases (exponential or stationary) as inputs to an OST circuit. This allows the circuit to autonomously trigger outputs based on the cell's physiological state, without needing an external inducer [6].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from advanced circuit designs that address binary logic limitations.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Advanced Circuits for Complex Signal Processing

| Circuit Type / Strategy | Key Performance Metric | Result | Application / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Operational Amplifier (OA) [6] | Signal Amplification Fold | 153 to 688-fold | Growth-state-responsive induction in E. coli |

| Orthogonal Signal Transformation (OST) [6] | Signal Crosstalk Mitigation | Creation of a diagonal signal matrix (off-diagonal elements ~0) | Processing 3-dimensional bacterial quorum sensing signals |

| Machine Learning-Optimized Toehold Switches (STORM & NuSpeak) [18] | Sensor Performance Improvement | Average 160% improvement (NuSpeak); up to 28x improvement (STORM) | Redesign of SARS-CoV-2 RNA sensors |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Engineering Complex Biological Signal Processing

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal σ/anti-σ Factor Pairs [6] | Core components for synthetic operational amplifiers (OAs) | Enable linear signal operations (e.g., subtraction) without crosstalk. |

| Deactivated Cas (dCas) Proteins [17] | Programmable scaffold for CRISPR-based logic gates and regulation. | Enables transcription modulation (CRISPRa/i) and dynamic control without DNA cleavage. |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Libraries [6] | Fine-tunes translation rates of circuit components. | Allows precise control over the coefficients (α, β) in signal processing equations. |

| Machine Learning Models (e.g., STORM, NuSpeak) [18] | Computational design and optimization of RNA-based parts. | Predicts and generates high-performance components, overcoming unreliable rational design. |

| Synthetic, De Novo Designed Promoters [15] | Provides insulated, context-independent genetic control. | Minimizes host crosstalk and improves circuit predictability and stability. |

| Abz-SDK(Dnp)P-OH | Abz-SDK(Dnp)P-OH, MF:C31H38N8O13, MW:730.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Flurbiprofen-D4 | Flurbiprofen-D4, MF:C15H13FO2, MW:248.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Experimental Workflow

For researchers aiming to implement a full signal-decomposition circuit, the following diagram and protocol detail the workflow from signal characterization to circuit validation.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Addressing Common Experimental Issues

1. Why is my genetic circuit exhibiting unpredictable output or high cell-to-cell variability?

This is frequently caused by gene expression noise, which originates from the inherent stochasticity of biochemical reactions involving low-copy-number molecules [19]. This "intrinsic noise" is a fundamental constraint on circuit performance.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Quantify Noise: Use flow cytometry to measure the distribution of circuit output (e.g., fluorescence) across a cell population, not just the mean. Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) or the Fano factor (variance/mean).

- Increase Component Copy Number: If possible, use high-copy-number plasmids or integrate multiple circuit copies into the genome to increase the molecular count of regulators and reduce relative fluctuations.

- Incorporate Negative Feedback: Design regulatory loops where the circuit's output represses its own production. Negative feedback is a natural mechanism to suppress stochastic fluctuations.

- Utilize Low-Burden Regulators: Switch to regulatory systems like CRISPRi that place a lower metabolic load on the host, as high burden can exacerbate noise and reduce growth rates, leading to population heterogeneity [20].

2. My circuit functions correctly initially but loses performance over multiple cell divisions. What is happening?

This is a classic sign of evolutionary instability. Unintended interactions between the circuit and the host, such as metabolic burden or the expression of toxic components, impose a selective pressure. Cells that inactivate the circuit (e.g., via mutations) gain a growth advantage and outcompete the desired population over time [19] [21].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reduce Metabolic Burden:

- Use Tuned Expression: Avoid overly strong constitutive promoters. Use inducible systems or promoters matched to the required expression level.

- Employ Low-Burden Parts: Implement CRISPRi-based logic gates, which primarily require transcription of sgRNAs and translation of a single dCas9 protein, thereby conserving translational resources [20].

- Minimize Toxicity: Ensure that heterologous proteins, especially those from distant species (e.g., algal transporters in E. coli), are not toxic to the host [19].

- Implement Population Control: For long-term applications, consider incorporating "kill switches" or other population control mechanisms that selectively eliminate cells that lose the circuit.

- Reduce Metabolic Burden:

3. How can I prevent my multi-input sensor from responding to the wrong signal (crosstalk)?

Crosstalk occurs when a component of your circuit (e.g., a transcription factor) inadvertently responds to a non-cognate input. This can be addressed through insulation or network-level compensation [21].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Characterize Crosstalk: Systematically expose your circuit to each input signal individually and in combination. Quantify the output for all scenarios to map the degree of crosstalk.

- Molecular Insulation: Screen for or engineer more orthogonal components. For example, mutate DNA-binding proteins to enhance specificity for their target promoters [19] [21].

- Network-Level Compensation: If insulation is difficult, design a compensatory circuit that integrates signals to cancel out the crosstalk. This involves using a sensor specific to the interfering signal to adjust the output of the crosstalk-prone sensor [21].

4. My circuit design works in a cell-free system but fails in living cells. Why?

Living cells introduce context dependencies absent in cell-free systems. The primary culprits are metabolic burden and unintended interactions with the host chassis [19].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Model Resource Allocation: Use computational models to evaluate the impact of resource (ribosomes, polymerases) titration on both circuit function and host health [19].

- Characterize Parts In Vivo: Always validate part performance (promoter strength, RBS efficiency) within the final host chassis, as their behavior can be highly context-dependent.

- Rationally Design dCas9 Expression: When using CRISPRi, design a dCas9 expression cassette that balances low burden with high repression efficiency. A medium-strength, constitutive promoter on a low-copy plasmid is often a good starting point [20].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Sensor Circuits with Varying Configurations. Utility is calculated as (Output Fold-Induction) × (Relative Input Range) [21].

| Sensor Type | Circuit Architecture | Key Modification | Output Fold-Induction | Relative Input Range | Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H~2~O~2~ (OxyR) | Open-Loop (OL) | Constitutive OxyR (MCP) | 15.0 | 58.4 | 876.0 |

| H~2~O~2~ (OxyR) | Open-Loop (OL) | High OxyR (HCP) | 23.6 | 63.0 | 1486.8 |

| H~2~O~2~ (OxyR) | Positive Feedback (PF) | OxyR-mCherry Fusion | 15.9 | 72.5 | 1152.8 |

| Paraquat (SoxR) | Open-Loop (OL) | Constitutive SoxR (MCP) | 42.3 | 95.8 | 4052.3 |

| Paraquat (SoxR) | Tunable OL | Low IPTG (LCP) | ~100 (est.) | ~116 (est.) | 11,620.0 |

Table 2: Comparison of Transcriptional Regulator vs. CRISPRi NOT Gates. Performance metrics are based on data from [20].

| Feature | Transcriptional Regulator NOT Gate | CRISPRi NOT Gate |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Burden | High (Protein production & degradation) | Lower (Primarily dCas9 protein production) |

| Orthogonality | Limited by protein-DNA specificity | High (Programmable via sgRNA sequence) |

| Design Complexity | Requires specific repressor protein for each target | Requires only new sgRNA for each target |

| Impact on Host | Can significantly deplete translational resources, reducing growth rate | Lower burden, leading to more predictable circuit function |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping Crosstalk and Implementing Compensation in a Dual-Sensor System

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to engineer ROS-sensing circuits in E. coli [21].

Construct Dual-Sensor Strain:

- Clone the primary sensor circuit (e.g., H~2~O~2~-OxyR-sfGFP) and the secondary sensor circuit (e.g., Paraquat-SoxR-mCherry) onto compatible plasmids with different copy numbers (e.g., HCP and MCP).

- Transform the assembled construct into the host strain (e.g., E. coli BW25113).

Characterize Individual Sensor Response:

- Grow cultures of the sensor strain to mid-log phase.

- Expose to a concentration gradient of each input (H~2~O~2~ and paraquat) individually.

- Measure the fluorescence output (sfGFP and mCherry) for each condition using a plate reader or flow cytometry.

- Fit the input-output data to Hill functions to establish the baseline transfer function for each sensor.

Quantify Crosstalk:

- Expose the sensor strain to a fixed concentration of the primary input (e.g., H~2~O~2~) while varying the concentration of the non-cognate, interfering input (e.g., paraquat).

- Measure the output of the primary sensor (sfGFP). An increase in sfGFP upon paraquat addition indicates crosstalk into the H~2~O~2~ sensing pathway.

Design and Build Compensation Circuit:

- Use the quantitative crosstalk data to design a circuit that takes the secondary sensor's output (which detects the interfering input) and uses it to down-regulate the output of the primary sensor.

- This can be achieved by having the secondary sensor's output drive the expression of a repressor (or CRISPRi sgRNA) that targets the primary sensor's output reporter.

Validate Compensated Circuit:

- Introduce the compensation circuit into the dual-sensor strain.

- Repeat the crosstalk quantification experiment (Step 3). A successful design will show a significantly reduced or abolished response of the primary sensor to the interfering input, while maintaining its response to the cognate input.

Protocol 2: Characterizing Burden of CRISPRi Inverters

This protocol outlines how to assess the low-burden properties of CRISPRi-based NOT gates [20].

Design dCas9 Expression Cassette:

- Clone the dCas9 gene under a medium-strength, constitutive promoter (e.g., J23109 from the Anderson collection) on a low-copy plasmid to minimize basal burden.

Construct NOT Gate Variants:

- Design sgRNAs targeting a repressible promoter (e.g., P~lux~, P~lac~, P~tet~) controlling an output reporter (e.g., GFP).

- Clone the sgRNA under the control of an inducible promoter (the input) on a separate plasmid.

Measure Circuit Performance and Burden:

- Transform the dCas9 plasmid and sgRNA plasmid into the host strain.

- Grow cultures with and without the inducer (input ON vs OFF).

- Measure Repression Efficiency: Quantify the output fluorescence. Calculate the fold-repression (OFF/ON ratio).

- Measure Burden: Simultaneously measure the growth rate (OD~600~) of the cultures. Compare the growth rate of cells with the active CRISPRi circuit to cells containing a non-functional control circuit or an empty vector. A smaller reduction in growth rate indicates lower burden.

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Addressing Interference in Genetic Circuits.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 and sgRNA Scaffold | Core components for CRISPR interference (CRISPRi). dCas9 binds DNA without cutting, and the sgRNA programmably targets it to specific sequences. | Constructing low-burden, orthogonal logic inverters and NOR gates [20]. |

| Orthogonal DNA-Binding Proteins | Libraries of well-characterized repressors/activators (e.g., TetR, LacI homologs) that do not cross-react. | Building multi-input circuits with minimized molecular crosstalk [22]. |

| Tunable Promoter Libraries | Sets of promoters with graduated strengths (e.g., Anderson collection). | Balancing expression levels to minimize metabolic burden and optimize signal-to-noise ratios [19] [22]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins | Genes encoding proteins like sfGFP and mCherry with distinct excitation/emission spectra. | Quantifying circuit output, measuring transfer functions, and quantifying cell-to-cell variability (noise) [21]. |

| Standardized Assembly System (e.g., BioBricks) | Genetic parts with standardized prefix/suffix sequences (e.g., EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, PstI sites). | Facilitating modular, reproducible, and high-throughput construction of complex circuits [23]. |

| Inducer Molecules (e.g., IPTG, AHL) | Small molecules that can reliably induce or repress promoter activity. | Providing controlled input signals for characterizing circuit response and tuning expression [21]. |

| Mao-B-IN-26 | Mao-B-IN-26|MAO-B Inhibitor|For Research Use | Mao-B-IN-26 is a potent, selective MAO-B inhibitor for neurodegenerative disease and cancer research. This product is for research use only (RUO). |

| Anti-inflammatory agent 50 | Anti-inflammatory Agent 50 | Anti-inflammatory Agent 50 is a potent research compound for investigating inflammatory pathways. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Engineering Solutions: Orthogonal Systems and Advanced Circuit Architectures

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

FAQ: Core Concepts of Orthogonality

Q1: What does "orthogonal" mean in the context of synthetic genetic circuits, and why is it critical? A: In synthetic biology, "orthogonal" describes bio-molecules that perform their designed functions without interacting with or interfering with the host's native cellular machinery [24]. This is critical because it prevents cross-talk, where unintended interactions can disrupt both the synthetic circuit's function and the host cell's health, leading to unpredictable behavior and circuit failure [24] [6].

Q2: What are the fundamental advantages of using CRISPR-based systems over traditional transcription factors (TFs) in complex circuits? A: CRISPR systems, particularly those using a nuclease-null Cas protein (dCas9), offer superior programmability, modularity, and orthogonality compared to traditional TFs [25]. Modifying the target of a dCas9-based regulator only requires changing the short ~20 nt guide RNA (gRNA) sequence, which is simpler and more predictable than re-engineering protein-DNA interfaces [25]. Furthermore, the theoretical orthogonality pool of gRNAs is vast, supporting the construction of large circuits [25].

Q3: How do σ/anti-σ pairs contribute to orthogonal signal processing? A: σ/anti-σ pairs are naturally orthogonal regulatory units. In engineered circuits, they can be designed to create linear input-output functions, such as subtraction and scaling [6]. This allows them to act as core components in synthetic biological operational amplifiers (OAs), which can decompose complex, overlapping biological signals (like those from different growth phases) into distinct, orthogonal components, thereby mitigating cross-talk [6].

FAQ: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q4: Our CRISPR-dCas9 circuit shows high off-target effects. How can we improve its specificity? A: High off-target activity is a common challenge. To address it:

- gRNA Design: Use online algorithms to design highly specific gRNAs and predict potential off-target sites. Ensure the gRNA sequence is unique within the host genome [26].

- High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Employ engineered high-fidelity Cas9 or Cas12 variants that have reduced off-target cleavage activity [26] [27].

- Cargo Form: Consider delivering CRISPR components as a pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (Cas protein + gRNA). RNP delivery is immediately active and has been shown to increase precision and reduce off-target effects compared to plasmid DNA delivery [27].

Q5: We are experiencing low editing efficiency with our CRISPR system. What factors should we optimize? A: Low efficiency can stem from several factors:

- Delivery Method: Verify your delivery method (e.g., electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors) is effective for your specific cell type. Different cells have varying transfection efficiencies [26].

- Component Expression: Confirm that the promoters driving Cas and gRNA expression are functional in your host cell. Codon-optimization of the Cas gene can also improve expression [26].

- Cargo Integrity: Check for degradation or impurities in your plasmid DNA, mRNA, or RNP complexes [26].

Q6: What delivery strategies are suitable for in vivo therapeutic applications of CRISPR systems? A: Delivery is a primary challenge for in vivo applications. The main strategies include:

- Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs): A popular choice due to their low immunogenicity and non-pathogenic nature. A key limitation is their small ~4.7 kb payload capacity, which can be circumvented by using smaller Cas orthologs or split systems [28] [27].

- Lentiviral Vectors (LVs): Can deliver larger payloads and infect non-dividing cells, but integrate into the host genome, raising safety concerns [27].

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Synthetic, non-viral vehicles that encapsulate CRISPR cargo (e.g., mRNA, RNP). They gained prominence with mRNA vaccines and can be engineered for organ-specific targeting [28] [27].

- Virus-Like Particles (VLPs): Engineered particles that are non-replicative and non-integrating, offering a potentially safer alternative to viral vectors, though manufacturing challenges remain [27].

Q7: Our synthetic circuit imposes a significant metabolic burden, affecting host viability. How can we mitigate this? A: Metabolic burden is a key bottleneck in complex circuit engineering.

- Use CRISPR-i/a: Circuits based on dCas9 and gRNAs impose a lower incremental burden than protein-based TFs, as they require only transcription (not translation) for each additional regulatory node [25].

- Inducible Systems: Implement self-adjustable expression systems for resource-intensive components like dCas9 to avoid constitutive overexpression [25].

- Orthogonal Central Dogma: Explore strategies to fully orthogonalize the circuit, such as using orthogonal DNA replication systems or non-canonical nucleobases, to minimize competition with host resources [24].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Implementing a Synthetic Operational Amplifier with σ/anti-σ Pairs

This protocol details the construction of an open-loop operational amplifier (OA) circuit to orthogonally process two transcriptional input signals [6].

1. Principle: The OA circuit performs a linear operation of the form Output ∠(α · Input₠- β · Input₂), decomposing overlapping input signals into a distinct orthogonal output [6].

2. Reagents and Materials:

- Orthogonal σ/anti-σ pairs or analogous orthogonal activator/repressor pairs (e.g., T7 RNAP/T7 lysozyme) [6].

- Plasmid Backbones: Standardized plasmids for modular cloning (e.g., Golden Gate or MoClo assemblies).

- Host Strain: E. coli or other appropriate chassis.

- Inducers/Media: Required for your specific input promoters.

3. Procedure:

- Circuit Assembly:

- Clone the gene for the activator (A) (e.g., a σ factor) under the control of Input Promoter 1 (Xâ‚).

- Clone the gene for the repressor (R) (e.g., its cognate anti-σ factor) under the control of Input Promoter 2 (X₂).

- Clone an output promoter (O), which is specifically recognized by the activator (A), upstream of your reporter gene (e.g., GFP).

- Parameter Tuning:

- The coefficients α and β in the OA equation are tuned by modifying the Translation Rate of the activator and repressor. This is most commonly achieved by swapping the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) strengths upstream of the activator and repressor coding sequences [6].

- A library of RBSs with varying strengths should be tested to achieve the desired balance (α/β) for effective signal subtraction.

- Characterization and Validation:

- Transform the assembled circuit into your host strain.

- Measure the output (e.g., fluorescence) in response to a matrix of different input signal combinations (Xâ‚ and Xâ‚‚).

- Fit the data to the OA equation to quantify the actual α and β values and the circuit's dynamic range [6].

Data Presentation: Comparison of CRISPR Delivery Methods

The table below summarizes key characteristics of common CRISPR delivery vehicles to aid in selection for your experiments [28] [27].

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR-Cas Delivery Methods

| Delivery Method | Cargo Type | Typical Editing Efficiency | Payload Capacity | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Safety Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | DNA (ssAAV) | Moderate to High | Limited (~4.7 kb) | Low immunogenicity; FDA-approved for some therapies [27]. | Small payload; requires miniature Cas proteins [28] [27]. |

| Lentivirus (LV) | DNA | High | Large (~8 kb) | Infects non-dividing cells; stable genomic integration [27]. | Insertional mutagenesis risk; strong immune response [27]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) | mRNA, RNP | High (transient) | Moderate | Rapid, transient expression; low risk of genomic integration; tunable [27]. | Endosomal escape challenge; potential cytotoxicity at high doses [27]. |

| Electroporation | RNP, mRNA, DNA | High (in amenable cells) | N/A | Highly efficient for ex vivo work (e.g., T-cells) [27]. | Mostly restricted to ex vivo applications [27]. |

| Virus-Like Particle (VLP) | Protein (RNP) | Moderate (transient) | Moderate | Non-infectious; no genetic material; transient activity reduces off-target risk [27]. | Complex manufacturing; stability issues [27]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Orthogonal Circuit Construction

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 (nuclease-null) | CRISPR-based transcriptional regulator. | Serves as a programmable scaffold for activators (CRISPRa) or repressors (CRISPRi); requires guide RNA for targeting [25]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Targets dCas9 to specific DNA sequences. | ~100 nt RNA; 20 nt spacer sequence defines target; high programmability and orthogonality potential [25]. |

| Orthogonal σ/anti-σ pairs | Core components for synthetic operational amplifiers. | Enable linear signal processing (e.g., subtraction); provide orthogonality to host machinery [6]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | Engineered nucleases for improved specificity. | Reduce off-target editing; crucial for therapeutic applications [26] [27]. |

| RBS Library | Tuning translation initiation rates. | A collection of DNA sequences with varying strengths to optimize protein expression levels (e.g., for α/β coefficients in OAs) [6]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | In vivo delivery vehicle. | Preferred for gene therapy due to safety profile; requires small cargo [28] [27]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo and in vitro delivery of nucleic acids and proteins. | Versatile, synthetic vehicle; suitable for mRNA and RNP delivery [27]. |

| Icmt-IN-43 | Icmt-IN-43|ICMT Inhibitor|For Research Use | Icmt-IN-43 is a potent ICMT inhibitor for cancer research. It targets Ras protein maturation. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Icmt-IN-31 | Icmt-IN-31, MF:C19H24ClNOS, MW:349.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Conceptual Diagrams

Orthogonal Signal Processing via Synthetic Biological OA

Diagram 1: Signal decomposition via synthetic biological OA. Overlapping input signals (Xâ‚, Xâ‚‚) drive the expression of an activator and a repressor. The OA circuit performs a linear subtraction operation, producing a single, orthogonal output signal.

CRISPR-Cas Workflow and Delivery Methods

Diagram 2: CRISPR workflow from cargo to outcome. CRISPR components can be delivered as DNA, RNA, or protein (RNP) using viral or non-viral vehicles to achieve gene regulation or editing in the target cell.

Implementing Synthetic Biological Operational Amplifiers for Signal Decomposition

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What is a synthetic biological operational amplifier (OA), and what is its primary function?

A synthetic biological operational amplifier is a genetically encoded circuit designed to process biological signals within a cell. Its primary function is to perform linear operations, specifically weighted subtraction, on input signals to decompose complex, non-orthogonal biological signals into distinct, orthogonal components. This process enhances the precision, adaptability, and signal-to-noise ratio of genetic circuits by mitigating crosstalk, which is the unwanted interference between different signal transduction pathways [6].

Crosstalk frequently occurs when synthetic genetic circuits use components that are not fully orthogonal, leading to a situation where an input intended for one pathway inadvertently activates another [21]. This is a significant challenge when processing signals from complex environments, such as bacterial quorum-sensing systems or growth-phase-dependent promoters, where multiple signals exhibit overlapping expression profiles [6]. OA circuits address this by performing signal decomposition. They apply a linear transformation (e.g., ( \alpha \cdot I{1} - \beta \cdot I{2} )) to the input signals, effectively isolating the desired signal from the interfering one. This network-level integration compensates for molecular-level crosstalk without requiring modification of endogenous genes [6] [21].

FAQ 3: My OA circuit's output is non-linear or saturates. What could be the cause?

The output of an OA circuit is governed by the equation ( O = \frac{O{\max} \cdot X{E}}{K{2} + X{E}} ), where ( X{E} = \alpha \cdot X{1} - \beta \cdot X{2} ) is the effective activator concentration [6]. The output is linear only when ( X{E} \ll K{2} ). Saturation occurs when ( X{E} ) becomes too large relative to the activator binding constant, ( K_{2} ). Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Linear Range: Characterize your circuit's transfer curve by measuring the output over a wide range of input signals. Ensure you are operating within the linear portion of the curve.

- Tune Binding Affinity: The linear range is positively correlated with ( K{2} ). If saturation occurs too easily, consider engineering your activator or its binding site to have a weaker binding affinity (higher ( K{2} )) to extend the linear operational range [6].

- Adjust Circuit Gains: Reduce the gains ( \alpha ) or ( \beta ) by tuning the RBS strengths of the activator or repressor. This will lower the effective concentration ( X_{E} ), bringing it back into the linear range [6].

FAQ 4: How can I improve the signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range of my OA circuit?

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Optimize RBS Strength: Fine-tuning the ribosome binding site (RBS) strength is a primary method for controlling the translation rates of the activator (A) and repressor (R). This directly adjusts the coefficients ( \alpha ) and ( \beta ) in the OA operation, allowing you to maximize the desired output while minimizing background noise [6].

- Implement Negative Feedback: Utilize a closed-loop configuration where the circuit's output, or a component of it, creates negative feedback. This configuration can enhance stability, reduce sensitivity to parameter fluctuations, and improve the circuit's signal-to-noise ratio [6].

- Tune Transcription Factor Levels: For circuits based on transcription factors like OxyR or SoxR, constitutively expressing the TF from plasmids with different copy numbers can significantly enhance performance. For instance, low-level constitutive expression of SoxR was shown to increase the utility metric (a measure combining dynamic range and fold-induction) from 4,052.3 to 11,620.0 [21].

FAQ 5: What strategies can ensure the orthogonality of my OA circuit within the host cell?

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Select Orthogonal Parts: Use genetic components derived from distant species or highly engineered systems that do not natively interact with the host's regulatory networks. Examples include extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ/anti-σ pairs, T7 RNA polymerase/T7 lysozyme, and bacterial transcription factors in eukaryotic cells [6] [12].

- Characterize Parts Individually: Before integration, test all regulatory parts (promoters, RBSs, protein pairs) for unintended interactions with each other and the host genome.

- Manage Metabolic Burden: High expression levels or the use of multiple, high-copy plasmids can stress the host cell, leading to unpredictable behavior and non-orthogonal effects. Use lower-copy plasmids and inducible systems to minimize this burden [6].

Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: Construction and Testing of a Basic Open-Loop OA Circuit

This protocol outlines the steps to build and characterize a synthetic OA circuit designed to perform the operation ( \alpha \cdot X{1} - \beta \cdot X{2} ) in E. coli.

Methodology:

- Plasmid Construction:

- Clone your orthogonal activator (e.g., an ECF σ factor) and repressor (e.g., its cognate anti-σ factor) onto separate expression plasmids [6].

- The activator should be under the control of input promoter ( X{1} ) and the repressor under input promoter ( X{2} ). Use RBS libraries to create variants with different translation strengths.

- Place an output reporter gene (e.g., GFP) under the control of a promoter specific to your activator.

- Transformation and Cultivation: Co-transform the activator and repressor plasmids into your host strain. Grow cultures in conditions that allow you to independently vary the signals for ( X{1} ) and ( X{2} ).

- Circuit Characterization: Measure the output fluorescence (or other reporter signal) across a matrix of different ( X{1} ) and ( X{2} ) induction levels. Fit the input-output data to the theoretical model ( O = \frac{O{\max} \cdot (\alpha X{1} - \beta X{2})}{K{2} + (\alpha X{1} - \beta X{2})} ) to determine the parameters ( \alpha ), ( \beta ), ( O{\max} ), and ( K{2} ) for your circuit [6].

Protocol 2: Implementing Orthogonal Signal Transformation (OST) for Multi-Signal Decomposition

This protocol describes a framework for decomposing N-dimensional, non-orthogonal signals, such as those from different bacterial growth phases or quorum-sensing molecules [6].

Methodology:

- Define Input Vectors: Represent the activity of N promoters in response to different conditions as N-dimensional vectors (e.g., [expression in condition 1, expression in condition 2, ..., expression in condition N]).

- Design the Coefficient Matrix: Construct a matrix that defines the linear transformation needed to convert your non-orthogonal input vectors into a diagonal matrix, where each output is specific to one condition.

- Build the OA Network: Implement this matrix biologically by constructing N OA circuits. Each OA circuit ( i ) should be designed to compute a weighted sum of all inputs, ( Outputi = \sum{j=1}^{N} C{ij} \cdot Inputj ), where the coefficients ( C_{ij} ) are realized by tuning the RBS strengths and regulatory logic of each OA circuit [6].

- Validation: Measure the output of each OA circuit across all conditions. A successful decomposition will show that each circuit responds strongly to its designated condition and weakly to others, effectively diagonalizing the system.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Optimized Sensor Circuits

| Circuit Component | Configuration | Output Fold-Induction | Relative Input Range | Utility Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H~2~O~2~ Sensor (OxyR-oxySp) | Open-Loop (Medium-copy plasmid) | 15.0x | 58.4x | 876.0 | [21] |

| H~2~O~2~ Sensor (OxyR-oxySp) | Open-Loop (High-copy plasmid) | 23.6x | 63.0x | 1486.8 | [21] |

| H~2~O~2~ Sensor (OxyR-oxySp) | Positive Feedback | 15.9x | 72.5x | 1152.8 | [21] |

| Paraquat Sensor (SoxR-pLsoxS) | Open-Loop (Genomic SoxR only) | - | - | 4364.7 | [21] |

| Paraquat Sensor (SoxR-pLsoxS) | Open-Loop (Low induced SoxR) | 42.3x | 95.8x | 11620.0 | [21] |

Table 2: Tuning Parameters for OA Circuit Optimization

| Parameter | Symbol | Biological Implementation | Effect on Circuit Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activator Coefficient | ( \alpha ) | RBS strength & degradation rate of activator [6] | Scales the contribution of input ( X1 ); higher ( \alpha ) increases gain from ( X1 ). |

| Repressor Coefficient | ( \beta ) | RBS strength & degradation rate of repressor [6] | Scales the contribution of input ( X2 ); higher ( \beta ) increases suppression from ( X2 ). |

| Maximum Output | ( O_{\max} ) | Strength of the output promoter [6] | Determines the maximum possible expression level of the output reporter. |

| Binding Constant | ( K_{2} ) | Binding affinity of activator to output promoter [6] | Defines the linear range; a higher ( K_2 ) extends the range of linear operation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Synthetic OA Circuit Construction

| Item | Function in OA Circuits | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal σ/anti-σ pairs | Core components acting as activator and repressor; ensures orthogonality from host machinery. | ECF σ factors and their cognate anti-σ factors [6]. |

| T7 RNAP / T7 Lysozyme | An orthogonal polymerase and its specific inhibitor; can be used as an alternative activator/repressor pair. | T7 RNA Polymerase and T7 Lysozyme [6]. |

| RBS Library | A collection of ribosomal binding sites with varying strengths; crucial for tuning the coefficients ( \alpha ) and ( \beta ). | Synthetic RBS sequences with different translation initiation rates [6]. |

| Orthogonal Promoters | Input promoters that respond to specific signals (e.g., growth phase, small molecules) with minimal crosstalk. | Growth-phase-responsive promoters (e.g., from exponential/stationary phase) [6]. Quorum-sensing promoters [6]. |

| Plasmids of Different Copy Numbers | Vectors (Low, Medium, High copy) to control the dosage of circuit components and manage metabolic burden. | Used to fine-tune transcription factor levels (e.g., OxyR, SoxR) for optimal dynamic range [21]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins | Quantitative output markers for characterizing circuit performance (e.g., transfer curves, crosstalk). | GFP, sfGFP, mCherry [21]. |

| Imperatorin-d6 | Imperatorin-d6, MF:C16H14O4, MW:276.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram Title: Framework for Multi-Signal Decomposition via OA Networks

Diagram Title: Core Architecture of a Synthetic Biological OA

Advanced Logic Gates and Multi-Input Biosensors for Specific Therapeutic Targeting

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My multi-input biosensor shows incorrect output even when only one input is present. What could be wrong?

- A: This is a classic symptom of pathway crosstalk, where a component of one sensing pathway in your circuit unintentionally interacts with a non-cognate component from another pathway. This is a common challenge when using sensitive natural transcription factors like OxyR and SoxR in E. coli. First, quantify the crosstalk using a dose-response curve for each input in isolation and in combination. Your circuit may require the implementation of a crosstalk-compensation circuit that integrates signals from both pathways to correct the erroneous output [21].

Q: The output signal from my genetic circuit is weak, leading to poor differentiation between ON and OFF states. How can I improve this?

- A: A weak output fold-induction often stems from suboptimal expression levels of your circuit's regulators. Consider:

- Tuning Regulator Expression: Use promoters of different strengths or plasmid copy numbers to fine-tune the constitutive expression of your transcription factors (e.g., OxyR, SoxR). Even small changes can significantly impact the output fold-induction and dynamic range [21] [22].

- Circuit Topology: Test different circuit architectures, such as open-loop (OL) configurations versus positive-feedback (PF) loops. For instance, an open-loop OxyR circuit provided higher output fold-induction, while a positive-feedback version offered a wider input range [21].

- A: A weak output fold-induction often stems from suboptimal expression levels of your circuit's regulators. Consider:

Q: My biosensor works perfectly in simple buffer but fails in complex biological samples like serum. What should I investigate?

- A: Performance degradation in complex media is frequently due to non-specific interference or biofouling. Review your signal transduction strategy:

- Electrochemical Biosensors: A drifting reference potential in a combined counter/pseudo-reference electrode can cause significant analytical errors under biological current loads. Using separate counter and reference electrodes can stabilize the potential and restore accuracy [29].

- Optical Biosensors: Ensure your biointerface (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) has high specificity for the target analyte to minimize cross-reactivity with other molecules in the sample [30] [31].

- A: Performance degradation in complex media is frequently due to non-specific interference or biofouling. Review your signal transduction strategy:

Q: I am trying to build a multi-virus detection biosensor. How can I design it to avoid cross-reactivity between different viral probes?

- A: Achieving high specificity in multiplexed biosensors requires careful biointerface design and spatial segregation.

- Spatial Separation: Create discrete detection regions (e.g., multiple sensing chips, micro-wells, or patterned channels on a single sensor die) for each viral target. This physically separates the probes and their resulting signals [31].

- Orthogonal Probes: Select recognition elements (e.g., antibodies, nucleic acid sequences) that are highly specific to their intended target and show minimal affinity for non-target viruses. Thorough validation of orthogonality is crucial [31].

- A: Achieving high specificity in multiplexed biosensors requires careful biointerface design and spatial segregation.

Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting Signal Crosstalk in Genetic Circuits

Problem: The output of a biosensor circuit is influenced by an off-target input, reducing its specificity.

Investigation and Solution Steps:

- Map Individual Dose Responses: For a dual-input sensor, begin by measuring the transfer curve (input concentration vs. output signal) for Input A alone across its dynamic range. Repeat for Input B alone [21].

- Quantify the Crosstalk: Expose the circuit to a fixed, non-saturating concentration of Input A while titrating Input B. Plot the output and calculate the degree to which Input B activates the sensor for Input A. The goal is to determine the crosstalk coefficient [21].

- Implement a Compensation Circuit: Design a second circuit that specifically senses the interfering input (Input B). Use its output signal to adjust the output from your primary crosstalk-sensitive sensor. This network-level integration actively compensates for the crosstalk, restoring specificity [21].

Workflow Diagram: Crosstalk Compensation

Guide 2: Resolving Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Electrochemical Biosensors

Problem: The biosensor's output current is unstable or drifts, making it difficult to distinguish a true positive signal from background noise.

Investigation and Solution Steps:

- Verify the Reference Electrode: This is a critical but often overlooked component. If using a combined counter/pseudo-reference electrode (e.g., a single Ag/AgCl wire), be aware that it is susceptible to potential shifts.

- Symptom: Reference potential shifts approximately 5 mV per 20 mM change in analyte concentration [29].

- Impact: This can lower the measured current and lead to analytical deviations as high as 14% [29].

- Solution: Where possible, use a stable, separate reference electrode to isolate the sensing potential from the current-carrying counter electrode [29].

- Check for Biofouling: Inspect the working electrode surface. A contaminated surface can increase impedance and noise. Clean or re-polish the electrode according to manufacturer protocols.

- Optimize Assay Conditions: Re-check the pH, buffer ionic strength, and temperature to ensure they are optimal for your biorecognition element (enzyme, antibody, etc.).

Troubleshooting Flowchart: Signal Instability

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Crosstalk in a Dual ROS-Sensing Genetic Circuit

This protocol outlines the procedure to characterize and quantify crosstalk between hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) and paraquat (Oâ‚‚â»)-sensing pathways in E. coli [21].

Key Materials:

- Strains: E. coli BW25113 or MG1655Pro with appropriate sensor plasmids.

- Plasmids:

- Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ Sensor: High-copy plasmid (HCP) with sfGFP under control of an OxyR-responsive promoter (e.g., oxySp), and a constitutive OxyR expression cassette.

- Paraquat Sensor: Low-copy plasmid (LCP) with constitutive SoxR and mCherry under control of a SoxR-responsive promoter (e.g., pLsoxS).

- Inducers: Hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) and Paraquat (Methyl viologen).

- Equipment: Plate reader capable of measuring fluorescence (sfGFP: Ex/Em ~485/510 nm; mCherry: Ex/Em ~587/610 nm).

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Co-transform both sensor plasmids into your E. coli host strain. Grow overnight cultures in selective media.

- Dose-Response for Single Inputs:

- Dilute overnight culture and grow to mid-log phase.

- For Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ dose-response: Aliquot culture and induce with a range of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ concentrations (e.g., 0 - 1.2 mM). Do not add paraquat.

- For Paraquat dose-response: Aliquot culture and induce with a range of Paraquat concentrations. Do not add Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚.

- Incubate for a fixed period (e.g., 4-6 hours) and measure both sfGFP and mCherry fluorescence.

- Dose-Response for Dual Inputs (Crosstalk Measurement):

- Aliquot culture and induce with a fixed, sub-saturating concentration of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ (e.g., 0.3 mM).

- To these aliquots, add the same range of Paraquat concentrations from Step 2.

- Incubate and measure fluorescence as before.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the fluorescence of the Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ sensor (sfGFP) against the concentration of the non-cognate input (Paraquat).

- Fit the data to a Hill function. The response of the Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ sensor to Paraquat quantifies the crosstalk from the paraquat pathway into the Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ pathway [21].

Signaling Pathway Diagram

Protocol 2: Implementing a Crosstalk-Compensation Circuit

This protocol follows the quantification of crosstalk and describes the construction of a genetic circuit that compensates for the interference [21].

Procedure:

- Circuit Design: Based on your crosstalk quantification, design a circuit where the output from the sensor detecting the interfering input is used to modulate the primary sensor's output. This creates an integrated network that corrects for the crosstalk.

- Genetic Construction: Assemble the compensation circuit on a plasmid. This may involve using the promoter from the interfering sensor (e.g., the SoxR-responsive promoter) to control the expression of a repressor or activator that fine-tunes the output of the primary sensor (e.g., the OxyR-responsive system).

- Validation: Transform the compensation circuit into your dual-sensor strain. Repeat the dual-input dose-response experiments (Protocol 1, Step 3). A successful compensation circuit will show a significantly reduced response in the Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ sensor output when paraquat is added, while maintaining its correct response to Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚.

Compensation Circuit Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and components used in the development of advanced biosensors and genetic circuits for therapeutic targeting.

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example/Application |

|---|---|---|

| OxyR Transcription Factor | Native E. coli transcriptional activator that senses Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚. Used as the core sensing element in Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-responsive genetic circuits [21]. | Constitutively expressed on a plasmid to build an open-loop Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ sensor with a reporter gene (e.g., sfGFP) under the control of the oxyS promoter [21]. |

| SoxR Transcription Factor | Native E. coli transcriptional activator that responds to superoxide stress induced by paraquat. Core component for building paraquat sensors [21]. | Used in an open-loop configuration with a reporter (mCherry) under a SoxR-responsive promoter (e.g., pLsoxS) for paraquat detection [21]. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 System | A highly programmable tool for transcriptional regulation. Catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) can be fused to repressor/activator domains and targeted to specific DNA sequences via guide RNAs [22]. | Enables the construction of large, orthogonal genetic circuits. Can be used to implement complex logic gates (NOT, AND) by repressing or activating multiple promoter targets [22]. |

| Serine Integrases | A class of site-specific recombinases that catalyze unidirectional DNA inversion between specific attachment sites. Useful for building permanent memory circuits [22]. | Used to construct combinatorial logic gates (e.g., AND, NOR). The DNA sequence is permanently flipped into a new state upon input signal, encoding a memory of the event [22]. |

| Orthogonal Repressors (TetR, LacI) | Libraries of well-characterized, engineered DNA-binding proteins (e.g., TetR, LacI homologs) that do not cross-react. Essential for building multi-layered circuits without crosstalk [22]. | Serve as the core components of logic gates like NOT and NOR. Their genes are placed under inducible promoters, and they repress output promoters [22]. |

| Three-Electrode Electrochemical Cell | An electrochemical setup consisting of separate Working, Counter, and Reference electrodes. Provides a stable and controlled potential for measurements [29]. | Critical for amperometric biosensors to avoid potential shifts and analytical errors associated with combined counter/pseudo-reference electrodes [29]. |

Performance Data from Key Experiments

The tables below summarize quantitative data from foundational experiments on genetic circuit performance and biosensor crosstalk.

| Circuit Configuration | Output Fold-Induction | Relative Input Range | Calculated Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Loop (MCP OxyR) | 15.0x | 58.4x | 876.0 |

| Open-Loop (HCP OxyR) | 23.6x | 63.0x | 1486.8 |

| Positive-Feedback (PF) | 15.9x | 72.5x | 1152.8 |

| Circuit Configuration | Output Fold-Induction | Relative Input Range | Calculated Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Loop (Genomic SoxR only) | Not Reported | Not Reported | 4364.7 |

| Open-Loop (MCP SoxR) | 42.3x | 95.8x | 4052.3 |

| Positive-Feedback (PF) | 10.2x | 82.6x | 842.5 |

| Tunable (Low IPTG) | Maximized | Maximized | 11,620.0 |

Modular Design and Insulation Strategies to Isolate Circuit Function

FAQs: Core Concepts for Researchers

What is circuit crosstalk in synthetic biology? Circuit crosstalk occurs when components of a synthetic genetic circuit, such as transcription factors or regulatory RNAs, unintentionally interact with or interfere with non-targeted parts of the circuit or the host's native cellular machinery. This can lead to incorrect logic outputs, signal bleed-through, and performance failures. It is analogous to crosstalk in electronic systems, where a signal on one channel creates an unwanted effect on another [32] [33].

How does a modular "Parts & Pools" framework reduce crosstalk? The "Parts & Pools" framework enforces a modular design where standard biological parts (promoters, RBSs, coding sequences) are connected via defined common signal carrier pools (e.g., RNA polymerases, ribosomes, transcription factors). This creates clean input/output interfaces between modules. By formally defining these interaction pools, the framework helps isolate module function and minimizes unintended resource competition or regulatory interference between circuit components [34] [35].

Why is my simple two-gene circuit not functioning as predicted? Even simple circuits can fail due to several common crosstalk-related issues:

- Metabolic Burden: Circuit operation consumes cellular resources, burdening the host and causing unexpected behavior [36].