Optimizing Gene Expression Using Orthogonal Regulators: From Foundational Concepts to Therapeutic Applications

Orthogonal gene expression systems represent a transformative approach in synthetic biology, enabling precise, independent control of multiple genetic elements without cross-talk with host regulatory networks.

Optimizing Gene Expression Using Orthogonal Regulators: From Foundational Concepts to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

Orthogonal gene expression systems represent a transformative approach in synthetic biology, enabling precise, independent control of multiple genetic elements without cross-talk with host regulatory networks. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of orthogonality from bacterial to mammalian systems and plants. It details cutting-edge methodological applications, including CRISPR-based transcription factors and synthetic promoter design, for programming complex cellular behaviors. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance performance and reduce variability in experimental and therapeutic settings. Finally, it covers rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of orthogonal tools, establishing a clear path for their use in advancing biomedical research, protein evolution, and next-generation gene therapies.

The Principles of Orthogonality: Decoupling Gene Expression from Host Networks

Core Concepts and Terminology: Frequently Asked Questions

What is orthogonal control in synthetic biology? Orthogonal control describes the design of biological systems that operate independently from the host's native cellular processes. The term "orthogonality" refers to the inability of two or more biomolecules, similar in composition or function, to interact with each other or affect one another's substrates. For example, two proteases are mutually orthogonal if they cannot cleave each other's target substrates, and two aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are orthogonal if they do not inappropriately cross-aminoacylate non-cognate tRNAs. This independence prevents unintended interactions, or cross-talk, enabling more predictable and reliable circuit performance [1].

Why is achieving orthogonality crucial for engineered genetic circuits? Engineered gene circuits frequently repurpose components from natural biological systems and are often hampered by inadvertent interactions with host machinery. This cross-talk can:

- Deplete essential host resources, reducing host fitness and circuit performance [1].

- Create unpredictable circuit behavior due to interference from native signaling pathways [2].

- Limit the complexity of circuits that can be built, as the potential for harmful interactions grows with the number of components [1]. Orthogonal systems mitigate these issues by creating insulated functional modules.

At what levels can orthogonal control be implemented? Orthogonal control can be engineered to act at multiple stages of the central dogma and beyond, including:

- DNA Level: Using orthogonal DNA replication systems (e.g., OrthoRep in yeast) [1], site-specific recombinases [3], and synthetic epigenetic regulation with non-canonical nucleobases [1] [3].

- Transcriptional Level: Employing synthetic transcription factors (sTFs) and orthogonal RNA polymerases that recognize custom promoter sequences [3] [4] [5].

- Translational Level: Utilizing orthogonal ribosomes and genetic code expansion to incorporate non-canonical amino acids [1].

- Post-Translational Level: Implementing synthetic receptors that trigger user-defined, self-contained signaling pathways independent of native intracellular signaling [2].

What are the primary design principles for creating orthogonal systems? The design of orthogonal systems relies on several key principles:

- Modularity: Systems are built from discrete, interchangeable parts (e.g., DNA-binding domains, activation domains, and core promoters) that can be mixed and matched [5].

- Self-Contained Signaling: Ideal orthogonal systems function as closed loops. For instance, synthetic receptors like MESA and NatE MESA are designed so that ligand binding directly induces a synthetic intracellular signal (e.g., protease-mediated release of a transcription factor) without relying on native signaling cascades [2].

- Use of Heterologous Components: Sourcing parts from unrelated organisms (e.g., using bacterial LexA DNA-binding domains in yeast) reduces the likelihood of cross-talk with the host's machinery [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High Background Expression (Leakiness) in an Off-State

- Potential Cause 1: Inadequate Insulation of Synthetic Promoters.

- Solution: Ensure synthetic promoters are designed with minimal sequence homology to host promoters. For systems using upstream activating sequences (UAS), verify that the core promoter has low basal activity on its own. Using a stronger or more specific UAS can improve the signal-to-noise ratio [4] [5].

- Potential Cause 2: Non-Specific Interaction of Synthetic Transcription Factors.

- Solution: Characterize the DNA-binding specificity of your sTF using methods like electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). If using a system with multiple sTFs, confirm their mutual orthogonality. Directed evolution can be used to enhance the specificity of DNA-binding domains [5].

- Potential Cause 3: Overexpression of Circuit Components.

Problem: Low Induced Expression or Weak Signal Output

- Potential Cause 1: Suboptimal Component Matching.

- Solution: Systematically test different combinations of functional modules. The output of a synthetic transcription amplifier system, for example, is tunable by selecting different activation domains, varying the number of transcription factor binding sites in the promoter, and swapping the core promoter module [5]. The table below summarizes key tunable parameters from a study in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [5].

- Potential Cause 2: Poor Surface Expression of Synthetic Receptors.

- Solution: When engineering synthetic receptors (e.g., NatE MESA), the choice of transmembrane and juxtamembrane domains is critical. Test designs that retain native domains versus those with validated orthogonal domains (e.g., truncated CD28 TMD) to find the optimal configuration for proper trafficking and function [2].

- Potential Cause 3: Host-Specific Silencing or Instability.

- Solution: Check the stability of your genetic constructs. For eukaryotic hosts, consider using matrix attachment regions (MARs) or insulators to prevent positional effects and epigenetic silencing. Also, ensure that codon optimization is appropriate for your host chassis.

Problem: Unintended Effects on Host Cell Fitness or Growth

- Potential Cause 1: Resource Overload and Metabolic Burden.

- Solution: High-level expression of orthogonal circuits can deplete cellular resources like nucleotides, amino acids, and energy. To mitigate this, use lower-copy-number plasmids or genomic integration, and avoid excessively strong constitutive promoters for circuit components [1].

- Potential Cause 2: Toxicity of Orthogonal Components.

- Solution: Some synthetic parts, such as certain activation domains or proteases, may be toxic to the host. If a design fails to yield viable transformants (as was observed with a modified QF2 AD in Penicillium chrysogenum [4]), try alternative orthologous parts or use inducible systems to control the timing of expression.

- Potential Cause 3: Inadvertent Disruption of Native Pathways.

- Solution: Perform RNA-seq or proteomic analyses on your engineered strain compared to a wild-type control to identify global changes. This can help pinpoint unexpected interactions and guide the re-design of more specific orthogonal parts.

| Module | Function | Tuning Effect on Output |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Domain (AD) | Recruits the transcriptional machinery | Stronger ADs (e.g., VP64) produce higher maximal output. |

| Transcription Factor Binding Site (UAS) | Number and affinity of sTF binding sites | Increasing the number of high-affinity binding sites amplifies the output signal. |

| Core Promoter (CP) | Site for assembly of the general transcription machinery | Different core promoters provide a wide range of baseline and maximal expression levels. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterizations

Protocol: Characterizing Synthetic Transcription Factor Binding

- Objective: To validate the specificity and affinity of a synthetic transcription factor (sTF) for its target DNA sequence using an Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) [5].

- Procedure:

- Protein Purification: Express and purify the sTF, often with an affinity tag (e.g., 6xHis).

- DNA Probe Preparation: Synthesize and label double-stranded DNA oligonucleotides containing the target binding site with a fluorescent dye (e.g., Cy5).

- Binding Reaction: Incubate a fixed amount of the labeled DNA probe with increasing concentrations of the purified sTF in a binding buffer.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load the reactions onto a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The protein-DNA complex will migrate slower than the free DNA probe.

- Imaging and Analysis: Visualize the gel using a fluorescence scanner. A successful, specific interaction is indicated by a clear shift in the probe's migration, which increases with higher sTF concentration. Competition with unlabeled probe can confirm specificity.

- Troubleshooting Tip: If a shift is not observed, optimize buffer conditions (salt, pH, divalent cations) and confirm the activity of the purified sTF.

Protocol: Validating Orthogonality of a Synthetic Receptor

- Objective: To confirm that a synthetic receptor (e.g., a NatE MESA receptor) signals through its intended orthogonal pathway without activating native signaling.

- Procedure:

- Reporter Cell Line: Create a cell line that expresses the synthetic receptor and a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) under the control of the receptor's synthetic output promoter.

- Stimulus Application: Expose the cells to the target ligand. Include controls with no ligand and with a negative control ligand.

- Output Measurement: Quantify the reporter signal (e.g., via flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy).

- Specificity Test: In a separate experiment, use pharmacological inhibitors or genetic knockouts of key components in the native signaling pathways that could be perceived as potential cross-talk targets. The output of the orthogonal receptor should be unaffected by these perturbations.

- Cross-Talk Test: Measure the activity of reporters for native pathways (e.g., NF-κB, MAPK) upon stimulation of your synthetic receptor. A truly orthogonal receptor will not activate these native reporters.

- Troubleshooting Tip: High background in the "no ligand" control may indicate leaky receptor dimerization; consider tuning the transmembrane domain or split protease affinity [2].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Orthogonal System Construction

| Reagent | Function | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal DNA-Binding Domains | Provides sequence-specific targeting to synthetic promoters. | LexA (bacterial) [5], QF (Neurospora crassa) [4], TALEs, dCas9. |

| Activation/Repression Domains | Recruits or blocks the cellular transcription machinery. | VP16, VP64 (strong activation) [4] [5], KRAB, SID (repression). |

| Synthetic Promoters | Drives expression of output genes in response to orthogonal regulators. | A core promoter combined with specific Upstream Activating Sequences (UAS) for a chosen sTF (e.g., QUAS for QF, LexAop for LexA) [4] [5]. |

| Orthogonal Replication System | Enables independent maintenance and evolution of genetic material. | OrthoRep system in yeast, based on cytoplasmic plasmids and an orthogonal DNA polymerase [1]. |

| Synthetic Receptor Platforms | Converts extracellular ligand sensing into a custom intracellular signal. | MESA (Modular Extracellular Sensor Architecture) [2], NatE MESA (using natural ectodomains) [2]. |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acids (ncAAs) | Enables genetic code expansion for novel chemical and biological properties. | Various ncAAs incorporated using orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pairs [1]. |

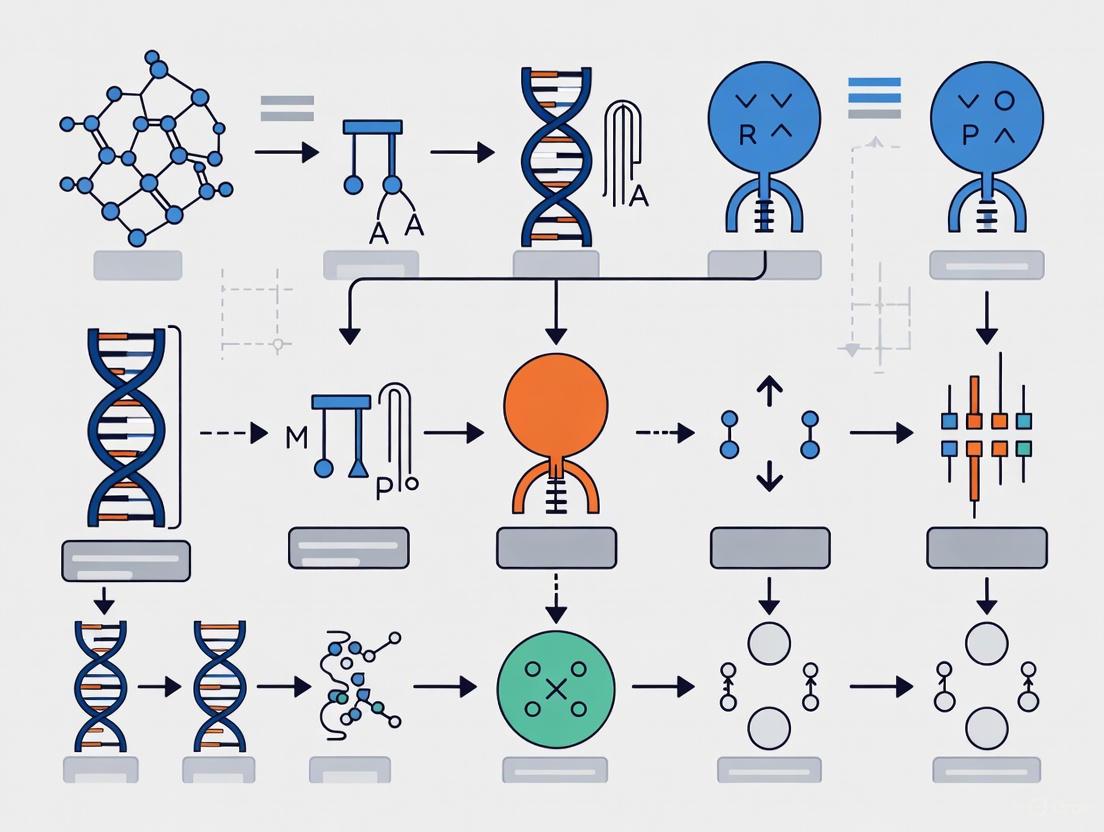

System Architecture and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram Title: Orthogonal Synthetic Receptor Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: Troubleshooting Guide for High Background Expression

The Critical Need for Orthogonality in Basic Research and Complex Phenotype Investigation

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Low Transcriptional Output in Synthetic Orthogonal Systems

Problem: Your synthetic orthogonal transcriptional system is producing unexpectedly low levels of gene expression output.

Question Answer:

- Q: I've assembled an orthogonal CRISPR/dCas9 activation system, but my gene expression output is very low compared to expectations. What could be wrong?

- Solution: Low transcriptional output can stem from several issues in your orthogonal system. First, verify the number and positioning of gRNA binding sites upstream of your minimal promoter. Research shows that varying the number of gRNA binding sites (typically 3-4 repeats) significantly impacts activation strength [6]. Second, ensure your synthetic promoters maintain proper modular architecture with gRNA binding sites followed by a minimal 35S promoter [6]. Third, check the expression level of your dCas9 activator fusion (e.g., dCas9:VP64) and confirm nuclear localization. Finally, validate that your gRNA expression constructs using either Pol III (U6) or inducible Pol II promoters are functioning correctly [6].

Table: Key Variables to Test for Low Transcriptional Output

| Variable to Test | Suggested Test Range | Expected Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Number of gRNA binding sites | 2, 3, 4, 5 repeats | Increased sites typically boost activation [6] |

| dCas9-activator expression level | Low, Medium, High | Higher levels may increase target activation |

| gRNA expression strength | Different promoters (U6, inducible Pol II) | Stronger promoters enhance gRNA production [6] |

| Incubation time post-induction | 24h, 48h, 72h | Longer times may increase output accumulation |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Cross-Talk in Orthogonal Genetic Circuits

Problem: Your designed orthogonal genetic circuits are exhibiting unexpected cross-talk between components that should function independently.

Question Answer:

- Q: My multi-gene circuit with supposed orthogonal regulators shows unexpected activation of off-target genes. How can I identify the source of cross-talk?

- Solution: Cross-talk violates the fundamental principle of orthogonality, where systems should function independently. To resolve this: First, conduct individual testing of each regulator-promoter pair to establish baseline specificity before combining them in full circuits [7] [6]. Second, verify the specificity of your DNA-binding elements (e.g., gRNA sequences for CRISPR systems) by examining potential off-target binding sites in your synthetic promoters through sequence alignment tools. Third, ensure you're using thoroughly characterized orthogonal parts with demonstrated minimal host interaction [6]. Implement proper controls including negative controls with non-targeting gRNAs and positive controls for each independent pathway. If cross-talk persists, consider increasing the sequence divergence between your orthogonal promoter elements or implementing additional insulation strategies with boundary elements.

Diagram: Cross-talk in Genetic Circuits

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Background Expression in Chemically-Induced Systems

Problem: Your chemically induced orthogonal regulation system shows significant background expression in the non-induced state.

Question Answer:

- Q: My chemically induced CRISPR/Cas9 activator shows high background expression even without the inducing ligand. How can I reduce this leakiness?

- Solution: Background expression in chemically induced systems compromises experimental control. To address this: First, optimize the chemical inducer concentration using a dose-response curve to identify the minimal concentration that provides robust induction with minimal background [8]. Second, consider implementing a dual-control system that combines transcriptional control with post-translational control, such as nuclear localization signal masking or conditional degrons. Third, verify the integrity of your inducible dimerization system components - ensure that your chemically induced dimerizing (CID) proteins are properly expressed and functional [8]. Fourth, examine your vector design for potential promoter interference that might cause basal expression of your activators. If using multiple inducible systems, ensure they are truly orthogonal and not cross-reacting with the same ligands.

Table: Troubleshooting Background Expression

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Potential Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter leakiness | Measure uninduced expression with different promoters | Switch to tighter regulated promoters |

| Non-specific CID interaction | Test system with mutated CID domains | Optimize CID domains for orthogonality [8] |

| Non-optimal inducer concentration | Perform dose-response curve | Titrate inducer for optimal window |

| Protein misfunction | Express & purify components for in vitro testing | Use validated protein variants |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Conceptual Questions

Q: What exactly does "orthogonality" mean in the context of genetic regulation? A: In genetic regulation, orthogonality refers to synthetic biological systems that operate independently from the host's native regulatory machinery and from each other [6]. This means orthogonal transcription factors should regulate only their intended synthetic promoters without affecting endogenous genes or other synthetic circuits. Similarly, orthogonal promoters should respond only to their cognate regulators. This concept ensures that complex genetic circuits can be built from modular parts that function predictably without unwanted interactions [3].

Q: Why is orthogonality critically important for investigating complex phenotypes? A: Orthogonality is essential for complex phenotype investigation because it enables precise dissection of individual pathway contributions without confounding cross-talk [7]. When studying multifactorial traits (like disease states or developmental processes), orthogonal systems allow researchers to selectively modulate specific genes or pathways while leaving others unaffected. This precise control is particularly valuable in drug development for validating therapeutic targets and understanding mechanism of action without the noise of pleiotropic effects [3].

Technical Implementation Questions

Q: What are the main advantages of CRISPR-based orthogonal systems compared to traditional transcription factor systems? A: CRISPR-based orthogonal systems offer several key advantages: (1) Programmability - specificity is determined by easily designed gRNA sequences rather than complex protein-DNA interactions; (2) Scalability - multiple orthogonal gRNAs can target different promoters using the same dCas9 activator; (3) Predictability - binding follows simple Watson-Crick base pairing rules; and (4) Versatility - the same dCas9 platform can be fused to various effector domains (activators, repressors, epigenomic modifiers) [6]. Traditional transcription factors require engineering of DNA-binding domains for each new target, which is more technically challenging.

Q: How many truly orthogonal regulatory systems can I realistically combine in a single cell? A: Current research demonstrates successful implementation of 3-4 mutually orthogonal systems in single plant cells [6] and human cells [8]. The theoretical limit is constrained by the number of available non-cross-reacting components (DNA-binding domains, small molecule inducers, etc.). The emerging toolkit includes orthogonal systems based on CRISPR/dCas9 with engineered gRNAs, synthetic zinc fingers, and recombinases with specific target sites [3]. When designing multi-system experiments, it's crucial to empirically validate orthogonality for your specific combination, as context-dependence can cause unexpected interactions in new cellular environments.

Q: Can I achieve temporal control with orthogonal systems? A: Yes, multiple strategies exist for temporal control. Chemically induced dimerization (CID) systems allow ligand-dependent temporal control of CRISPR/Cas9 activators with minimal background [8]. Light-controlled systems using photocleavable linkers or optogenetic dimerization domains provide even finer temporal resolution, enabling precise manipulation of gene expression patterns in the minute-to-hour range [9]. For example, recombinase activity has been made light-dependent by splitting the protein and reconstituting it through light-inducible dimerization systems [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Orthogonality of Synthetic Promoter-Transcription Factor Pairs

Purpose: To empirically confirm that synthetic transcriptional components function without cross-talk.

Materials:

- Plasmids encoding orthogonal transcription factors (e.g., dCas9:VP64) [6]

- Reporter constructs with synthetic promoters containing corresponding gRNA binding sites [6]

- Appropriate host cells (Nicotiana benthamiana, Arabidopsis thaliana, or human cell lines) [7] [6]

- Transfection/transformation reagents

- Reporter assay reagents (microscopy, luciferase, or flow cytometry equipment)

Procedure:

- Clone transcriptional units using modular cloning systems like Golden Gate or MoClo to ensure standardized assembly [6].

- Design a test matrix where each transcription factor is paired with each synthetic promoter in separate experiments.

- Transferd/transform each combination into your host system alongside appropriate controls (empty vector, non-targeting gRNA).

- Measure reporter expression after 24-48 hours using appropriate detection methods.

- Analyze data for orthogonality: True orthogonality is demonstrated when each transcription factor strongly activates only its cognate promoter and shows minimal activation (<5-10% of cognate activation) of non-cognate promoters [6].

Diagram: Orthogonality Validation Workflow

Protocol 2: Implementing Chemically Induced Orthogonal CRISPR Activation

Purpose: To establish temporal control of gene expression using ligand-inducible CRISPR-based orthogonal regulators.

Materials:

- Plasmids encoding chemically inducible dCas9 fused to dimerization domains [8]

- gRNA expression constructs targeting synthetic promoters [6]

- Chemical inducer (specific to your dimerization system)

- Appropriate cell culture materials and reporter assays

Procedure:

- Design synthetic promoters with target sites for your gRNAs upstream of a minimal promoter.

- Clone gRNA expression cassettes under control of Pol III (U6) or inducible Pol II promoters.

- Co-transfect inducible dCas9 activator, gRNA, and reporter constructs into your target cells.

- Treat with chemical inducer at varying concentrations and timepoints to establish kinetic and dose-response profiles.

- Quantify gene expression using appropriate methods (RT-qPCR, fluorescence, luminescence) at multiple timepoints post-induction.

- Verify orthogonality by testing multiple inducible systems with their specific ligands to confirm no cross-activation [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Orthogonal Genetic Regulation

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Specific Instances |

|---|---|---|

| Programmable DNA-binding platforms | Provide targeting specificity to synthetic promoters | dCas9:VP64 [6], TALEs [7], Zinc finger proteins [3] |

| Synthetic promoters | Serve as orthogonal targets for artificial transcription factors | Engineered promoters with gRNA binding sites upstream of minimal promoters [6] |

| Chemical dimerization systems | Enable temporal control of regulator activity | Chemically induced dimerizing (CID) proteins [8] |

| Modular cloning systems | Facilitate standardized assembly of genetic circuits | Golden Gate assembly, MoClo framework [6] |

| Reporter genes | Enable quantification of orthogonal system performance | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, BFP, YFP, RFP), luciferase [6] |

| Cox-2-IN-26 | Cox-2-IN-26, MF:C23H21N7OS3, MW:507.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antibacterial agent 92 | Antibacterial Agent 92|Triple-site aaRS Inhibitor | Antibacterial agent 92 is a potent triple-site aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) inhibitor. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

No or Low Expression Output

| Problem Cause | Underlying Principle | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Orthogonal Crosstalk | Circuit components (e.g., repressors, promoters) interact with host genome or other circuit parts, creating unintended regulation [3]. | Perform BLAST analysis to ensure component uniqueness; use highly orthogonal parts from different microbial species [3]. |

| Host Strain Mismatch | Expression of orthogonal components often requires specific host factors (e.g., T7 RNA polymerase in BL21(DE3) for pET systems) [10]. | Transfer plasmid to an appropriate expression host strain (e.g., BL21(DE3), BL21-AI) [10] [11]. |

| High Basal Expression (Leakiness) | Incomplete repression leads to resource drain and toxicity, compromising circuit function [3] [11]. | Use tighter regulation systems (e.g., BL21(DE3) pLysS/E); add glucose to repress basal T7 polymerase expression; consider arabinose-inducible pBAD system [11]. |

Unstable or Oscillating Expression Dynamics

| Problem Cause | Underlying Principle | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unintended Feedback Loops | Endogenous host regulators create unforeseen interactions with synthetic circuit [3] [12]. | Map host interactions using transcriptomics; insulate circuit with non-regulatory genetic elements [3]. |

| Insufficient Repressor Strength | Weak repressors cannot overcome strong promoter activity, failing to establish linearization [3] [13]. | Characterize repressor-promoter pairs; use chimeric repressors with stronger repression domains [13]. |

| Component Toxicity | Overexpressed regulatory proteins (e.g., repressors) burden the host, causing growth defects and instability [11] [14]. | Lower induction temperature (e.g., 18-30°C); reduce inducer concentration (e.g., 0.1-1 mM IPTG); use low-copy number plasmids [11]. |

High Cell-to-Cell Variability (Noise)

| Problem Cause | Underlying Principle | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Environment Effects | Genomic integration locus influences expression noise; repressed chromatin states associate with higher variability [15]. | Target genomic loci associated with low noise (e.g., open chromatin); use insulators to buffer positional effects [15]. |

| Low Burst Frequency | Expression noise is regulated by transcriptional burst frequency; low frequencies lead to higher variability [15]. | Engineer promoters for higher burst frequencies to reduce noise independent of mean expression levels [15]. |

| Resource Competition | Limited cellular resources (e.g., RNA polymerase, ribosomes) are shared between host and circuit, creating stochastic fluctuations [3]. | Use orthogonal resources (e.g., T7 RNA polymerase, orthogonal ribosomes) to decouple circuit from host [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterizations

Protocol 1: Quantifying Orthogonality and Crosstalk

Objective: Measure interaction between orthogonal system components and host genome.

- Clone Reporter Arrays: Construct fluorescent reporter plasmids for each repressor-promoter pair in your system.

- Transform Single and Multiple Systems: Introduce individual reporters and all possible combinations into your expression host (e.g., BL21(DE3)).

- Flow Cytometry Measurement: Grow cultures to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6), induce with appropriate concentration of inducer, and analyze using flow cytometry after 4-6 hours.

- Calculate Orthogonality Score: For each repressor-promoter pair (i, j), calculate the score as (Expression{ii} - Expression{ij}) / Expression_{ii}. A score of 1 indicates perfect orthogonality [3] [13].

Protocol 2: Characterizing Feedback Loop Dynamics

Objective: Analyze temporal dynamics and stability of repressor-based feedback loops.

- Circuit Assembly: Clone feedback architecture (e.g., autorepression loop) into appropriate vector with fluorescent reporter.

- Time-Course Monitoring: Transform into host, induce, and monitor both OD600 and fluorescence over 12-24 hours using plate readers.

- Single-Cell Analysis: Sample at key time points for flow cytometry to assess population heterogeneity.

- Model Fitting: Fit data to mathematical models (e.g., delayed differential equations: dx/dt = α/(1+x(t-τ)^h) - βx) to parameters like repression strength (h) and critical delay (τ*) [12].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram: Orthogonal Repressor System Architecture

Diagram: Troubleshooting Expression Problems

Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Need | Recommended Reagents | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Tightly Regulated Expression | BL21(DE3) pLysS/pLysE strains; BL21-AI for T7 and pBAD systems [11]. | pLysS/E expresses T7 lysozyme to inhibit basal T7 RNA polymerase; BL21-AI tightly controls T7 pol with arabinose [11]. |

| Orthogonal Transcriptional Parts | Synthetic transcription factors based on TALEs or dCas9; orthogonal RNA polymerases and sigma factors from bacteriophages [3] [13]. | Programmable DNA-binding domains target synthetic promoters without affecting host genes; phage polymerases only transcribe specific promoters [3]. |

| Noise Control & Characterization | Dual-reporter lentiviral systems for noise quantification; chromatin environment modifiers [15]. | Dual reporters distinguish intrinsic vs. extrinsic noise; epigenetic tools control burst frequency and size to tune variability [15]. |

| Circuit Memory & Logic | Serine integrases (Bxb1, PhiC31); tyrosine recombinases (Cre, Flp); CRISPR base/prime editors [3]. | Enable stable, heritable genetic memory through DNA inversion/excision; record stimulus history via sequential DNA edits [3]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: What is orthogonality in genetic engineering, and why is it critical for synthetic biology? Orthogonality refers to the design of synthetic biological systems that function independently from the host organism's native cellular processes. In practice, this means creating genetic regulators, promoters, and circuits that do not recognize the host's natural sequences and are not recognized or interfered with by the host's machinery. This is critical because it prevents unwanted cross-talk that can lead to:

- Circuit Failure: Host interference can disrupt the intended logic of synthetic gene circuits.

- Host Fitness Costs: Unprogrammed interactions can burden the host, causing severe growth and developmental defects, as observed in plants [6].

- Unpredictable Behavior: Without orthogonality, synthetic circuits behave inconsistently across different organisms or even different cell types, hindering reliable engineering [6] [16].

Q2: I am experiencing high basal expression (leakiness) in my orthogonal system. What are the primary causes and solutions? High basal expression is a common challenge. The causes and mitigation strategies are often system-dependent:

- Insufficient Promoter Insulation: Synthetic promoters may not be fully shielded from the host's transcriptional machinery.

- Solution: Ensure the use of well-characterized minimal promoters and consider increasing the number of engineered binding sites for your orthogonal transcription factor to enhance specificity [6].

- Leaky Inducer Systems: The inducible systems themselves may have background activity.

- Solution: Employ a dual-input cascade system. Research in human cell lines using a Tunable Noise Rheostat (TuNR) showed that a serial arrangement of two inducible transcriptional activators can significantly attenuate basal leakiness while achieving over 1000-fold induction [16].

- Context Sensitivity (for Riboswitches): The sequence surrounding a riboswitch, especially the coding region immediately downstream, can drastically affect its folding and function, leading to an "always ON" state [17].

- Solution: Systematically engineer the N-terminal sequence of the gene. Using a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach to optimize the ribosome-binding site (RBS), anti-RBS, and downstream codons can yield riboswitches with a 550-fold dynamic range over basal expression [17].

Q3: My orthogonal system works in one organism but fails in another. How can I improve portability? This typically stems from host-specific factors.

- Cause: Differences in transcriptional/translational machinery, chromatin environments, or innate immune responses against foreign DNA.

- Solutions:

- Use Highly Orthogonal Parts: Leverage regulators derived from distantly related species (e.g., yeast regulators in plants) to minimize recognition by the new host [7].

- Universal Programmable Systems: Adopt CRISPR/dCas9-based transcription factors. These can be programmed to target completely synthetic promoters, making the system inherently portable across eukaryotes. The core dCas9 activator is universal, and only the gRNA needs to be redesigned for new synthetic promoters [6].

- Validate Parts in the Target Host: Always characterize genetic parts (promoters, terminators) in the specific host organism of interest, as performance can vary significantly [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal/Induction | Weak synthetic promoter design | Increase the number of transcription factor binding sites (e.g., from 3 to 4 repeats) upstream of the minimal promoter [6]. |

| Sub-optimal expression of orthogonal regulators | Use stronger constitutive promoters to express the orthogonal transcription factor (e.g., dCas9 fusion) and ensure efficient nuclear localization [6]. | |

| High Cell-to-Cell Variability | Stochastic expression of circuit components | Use the TuNR circuit or similar to titrate the expression of the orthogonal components with small molecules, allowing you to find an induction regime that minimizes noise [16]. |

| Host Growth Defects | Toxicity or burden from circuit components | Implement inducible systems to only activate the circuit during experimentation. Use orthogonal systems to minimize pervasive interference with host genes [6]. |

| Poor Dynamic Range | Context-dependent part performance (esp. riboswitches) | Re-engineer the genetic context. For riboswitches, combine codon optimization of the downstream sequence with RBS and anti-RBS library screening to isolate high-performance variants [17]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a CRISPR/dCas9-Based Orthogonal Control System (OCS) in Plants

This protocol is adapted from the work published in Plant Methods for constructing a fully orthogonal gene expression system in plants using synthetic promoters and dCas9 [6].

1. Principle An artificial transcription factor (dCas9:VP64) is programmed with guide RNAs (gRNAs) to activate synthetic promoters (pATFs). These promoters are designed from scratch with binding sites for the gRNA, making them unresponsive to the plant's native transcription factors, thus achieving orthogonality.

2. Materials

- Molecular Cloning: Modular Cloning (MoClo) framework with Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI).

- Vectors: Agrobacterium shuttle vectors with plant selection markers (e.g., BASTA, hygromycin).

- Genetic Parts:

- Transcription Factor: dCas9:VP64 gene under a strong constitutive promoter.

- Synthetic Promoters (pATFs): Minimal 35S CaMV promoter upstream of 3-4 repeats of a gRNA-binding site.

- gRNA Expression Cassettes: Driven by Pol III (e.g., U6) or inducible Pol II promoters.

- Host: Nicotiana benthamiana for transient expression or Arabidopsis thaliana for stable transformation.

3. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Step 1: Design and Assemble Synthetic Promoters.

- Design oligonucleotides containing the desired gRNA target sequences in tandem repeats (3-4x).

- Clone these repeats directly upstream of a minimal 35S promoter in a MoClo-compatible vector.

- Step 2: Assemble Transcriptional Units.

- Using Golden Gate assembly, construct the following units:

- TU1: Constitutive Promoter -> dCas9:VP64 -> Terminator

- TU2: gRNA Promoter (U6 or inducible) -> gRNA scaffold -> Terminator

- TU3: Synthetic pATF -> Your Gene of Interest -> Terminator

- Using Golden Gate assembly, construct the following units:

- Step 3: Assemble Final Construct.

- Combine the transcriptional units (TUs) into a single final expression vector using the MoClo framework's connector sequences.

- Step 4: Transformation and Validation.

- Transform the final construct into Agrobacterium.

- Infiltrate Agrobacterium into N. benthamiana leaves for transient expression.

- Quantify gene expression (e.g., via fluorescence or luminescence) 2-4 days post-infiltration to validate orthogonal activation.

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Orthogonality Test: Co-express multiple orthogonal pATF-gRNA pairs. Confirm that each gRNA only activates its cognate pATF and shows minimal cross-activation of others.

- Leakiness: Measure the output signal (e.g., fluorescence) in the absence of the gRNA. Compare this to the signal when the gRNA is present. A high signal-to-background ratio indicates a well-insulated promoter.

Diagram 1: Orthogonal system architecture preventing host cross-talk.

Protocol 2: Decoupling Mean and Variability of Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells

This protocol is based on the TuNR (Tunable Noise Rheostat) system described in Nature Communications for the orthogonal control of mean expression and cell-to-cell heterogeneity in a human cell line [16].

1. Principle A synthetic circuit with two orthogonal, small molecule-inducible transcriptional activators connected in a cascade allows for independent titration of a gene's mean expression level and its population variability.

2. Materials

- Cell Line: Mammalian cells (e.g., PC9).

- Inducers: Abscisic Acid (ABA) and Gibberellic Acid (GA).

- Genetic Components:

- Node 1: ABA-inducible system (Gal4 DNA-binding domain fused to a split ABA-binding domain).

- Node 2: GA-inducible system (dCas9 fused to a split GA-binding domain and a VPR activation domain).

- gRNA targeting a promoter of choice (e.g., pTRE).

- Reporter Genes: mRuby (Node 1 reporter) and mAzamiGreen (Node 2/target gene reporter).

- Equipment: Flow cytometer for measuring fluorescence and population variance.

3. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Step 1: Circuit Integration.

- Stably integrate the complete TuNR circuit, along with a gRNA cassette and a reporter gene, into the genome of your mammalian cell line. Isolate single-cell clones to ensure homogeneity.

- Step 2: Characterization of the First Node.

- Treat cells with a dose range of ABA (e.g., 0-400 µM). Replenish media every 24 hours.

- Use flow cytometry to measure mRuby fluorescence daily until steady-state is reached (typically ~3 days). This characterizes the input-output relationship for Node 1.

- Step 3: Characterization of the Second Node.

- Prime cells with a saturating dose of ABA (400 µM) for 3 days.

- While maintaining ABA, treat with a dose range of GA. Measure mAzamiGreen fluorescence daily until steady-state (~6 days).

- Step 4: Isomean and Iso-variance Analysis.

- Treat cells with a full matrix of ABA and GA concentrations.

- For each (ABA, GA) combination, measure the mean fluorescence and the coefficient of variation (CV) or Fano factor of the population.

- Identify pairs of inducer concentrations that yield the same mean expression (isomeans) but different variabilities, and vice-versa.

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Plot the mean expression and population variance (e.g., CV) against the two inducer concentrations.

- Successful implementation is demonstrated by finding at least two different input combinations (e.g., High ABA/Low GA and Low ABA/High GA) that produce statistically identical mean expression but significantly different levels of cell-to-cell variability.

Diagram 2: Dual-input TuNR circuit for orthogonal control of mean and noise.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Goal | Essential Reagents / Tools | Function in Orthogonal Control |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Transcription | dCas9 Activator (e.g., dCas9:VP64, dCas9:VPR) [6] [16] | Programmable DNA-binding scaffold that recruits transcriptional activation machinery to synthetic targets without cleaving DNA. |

| Synthetic Promoters (pATFs) [6] | Engineered DNA sequences containing binding sites for gRNA/dCas9 complexes, minimizing recognition by host transcription factors. | |

| Multiplexed & Tunable Control | Small Molecule Inducers (e.g., ABA, GA) [16] | Orthogonal inputs that control the dimerization of synthetic transcription factors, allowing for precise, external titration of circuit activity. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) [17] | A statistical framework for efficiently optimizing multiple factors (e.g., RBS strength, temperature, inducer concentration) simultaneously to maximize system performance. | |

| Context Insulation | Engineered Riboswitches [17] | Structured RNA elements placed in the 5' UTR that undergo ligand-induced conformational changes to control translation initiation orthogonally from host regulation. |

| Standardized Assembly | Modular Cloning (MoClo) Toolkits [6] | A standardized cloning framework using Type IIS restriction enzymes that enables rapid, modular, and reproducible assembly of complex genetic circuits. |

| LpxC-IN-9 | LpxC-IN-9|LpxC Inhibitor | LpxC-IN-9 is a potent LpxC inhibitor with antibacterial activity. This product is for research use only and not for human use. |

| Ferroportin-IN-1 | Ferroportin-IN-1|Ferroportin Inhibitor|For Research Use | Ferroportin-IN-1 is a potent and selective ferroportin inhibitor for iron homeostasis research. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Table 1: Performance metrics of orthogonal regulatory systems across different hosts.

| System / Host | Key Regulator | Induction / Dynamic Range | Key Performance Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCS / Plants | dCas9:VP64 + Synthetic Promoters | N/A (Validated Orthogonality) | Successful concerted expression of multiple genes; tissue-specific and environmentally responsive. | [6] |

| TuNR / Human Cells | ABA & GA Inducible Cascade | >1000-fold (Transgene) | Decouples mean expression from population variability (noise); 7.2-fold induction of endogenous NGFR. | [16] |

| ORS / Bacteria | PPDA Riboswitch | 72-fold (Riboswitch-dependent); 550-fold (over basal) | Achieved via systematic engineering of RBS and N-terminal codon context to reduce sensitivity. | [17] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: My orthogonal transcription factor system shows high background expression (leakiness) in the absence of an inducer. What could be the cause and how can I resolve this?

High background expression often stems from non-specific interactions or insufficient promoter specificity. To address this:

- Optimize Promoter Design: Ensure your synthetic promoter has minimal sequence identity to the host's endogenous promoters. Using completely synthetic, de novo designed promoters can significantly reduce cross-talk with the host's regulatory machinery [18] [19].

- Verify Transcription Factor Orthogonality: Test your transcription factors for off-target binding to native genomic sequences. For CRISPR/dCas9-based systems, confirm the specificity of the gRNA and check for unintended PAM (protospacer adjacent motif) sites near the target [19].

- Adjust Effector Domains: The choice of activator or repressor domain (e.g., VP64, KRAB) fused to your DNA-binding protein can influence leakage. Screening different effector domains may help identify one with a more favorable ON/OFF ratio [19] [3].

FAQ: I am not achieving a strong enough induction (low dynamic range) with my orthogonal system. How can I improve the output?

A low dynamic range can be caused by weak promoter activation or inefficient transcription factor recruitment.

- Increase Binding Site Multiplicity: Incorporating multiple copies of the transcription factor binding site upstream of a minimal promoter can amplify the transcriptional output. For instance, synthetic promoters for dCas9:VP64 were designed with varying repeats of gRNA binding sites to enhance activation [18].

- Enhance Transcription Factor Activity: Consider using engineered, high-performance variants of your transcription factor. For example, an optimized λ cI mutant (cIopt) was shown to have significantly greater activity than the wild-type protein [20].

- Optimize Inducer Concentration: Systematically titrate the chemical inducer to find the concentration that yields maximum expression without causing cellular toxicity. The performance of some inducible systems is highly dependent on inducer concentration [21] [22].

FAQ: My system works in a model organism like E. coli, but fails in a non-model host. What steps can I take?

Failure in non-model organisms is often due to inefficient parts or host-specific incompatibilities.

- Use Broad-Host-Range Parts: Employ genetic parts and polymerases known to function across diverse species. For example, broad-host expression systems based on MmP1, K1F, and VP4 phage RNA polymerases have been successfully used in non-model organisms like Halomonas bluephagenesis and Pseudomonas entomophila where T7 RNAP fails [21].

- Decouple Regulation from Host Metabolism: Use inducers that the host cannot metabolize. For the rhaBAD promoter, switching the inducer from L-rhamnose (which is metabolized, causing transient expression) to L-mannose provided sustained, strong induction because E. coli could not use it as a carbon source [22]. This principle can be applied to other hosts.

- Check for Orthogonal Replication and Selection: Ensure your plasmid vectors contain origins of replication and selection markers that are functional in the new host [18].

Performance Data for Selected Orthogonal Systems

The following tables summarize key performance metrics for various orthogonal systems as reported in recent literature, providing a benchmark for experimental expectations.

Table 1: Performance of CRISPR/dCas9-Based Orthogonal Systems in Different Hosts

| Host Organism | System Description | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plants (e.g., Nicotiana benthamiana) | dCas9:VP64 + synthetic promoters (pATFs) | Demonstrated complete orthogonality; ratiometric expression output | Ethylene-driven, multiplexed control achieved | [18] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yeast) | dCas9/synTALE + synthetic promoters (synPs) | Induction Factor (ON/OFF ratio) | Up to 400-fold | [19] |

| Escherichia coli | dCas9-Mxi1 repressor | Circuit response | High orthogonality and digital response | [19] |

Table 2: Performance of Orthogonal Mutagenesis and Protein Evolution Systems

| System Name | Host Organism | Core Components | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Transcription Mutator (OTM) | H. bluephagenesis & E. coli | PmCDA1-UGI fused to MmP1 RNAP | On-target mutation frequency increase vs. control | >80,000-fold | [21] |

| Mutation Rate | 2.9 x 10â»âµ substitutions per base (s.p.b.) | [21] | |||

| Off-target rate (genomic) increase vs. control | 5-fold | [21] | |||

| Phagemid-assisted Evolution | E. coli | M13 phagemid + λ cI variants | Enrichment efficiency (strong vs. weak activator) | Enriched from 10³-fold excess in 6 rounds | [20] |

Table 3: Characteristics of Engineered Transcription Factor / Promoter Pairs

| TF / Promoter Class | Number of Orthogonal Pairs | Functionality | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriophage λ cI variants | 12 TFs on up to 270 promoters | Activator, Repressor, Dual Activator-Repressor | First set of dual activator-repressor switches for orthogonal logic gates [23] [20]. |

| synTALE / synP (Yeast) | A characterized set of functional pairs | Activator | Wide range of expression outputs, low background [19]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assembling Multi-Transcriptional Unit Constructs Using a Modular Cloning (MoClo) Framework

This protocol is adapted from a plant synthetic biology study for constructing complex genetic circuits with orthogonal parts [18].

Principle: The MoClo framework uses Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI) to assemble standardized genetic parts (Promoters, Coding Sequences, Terminators) into transcriptional units (TUs), which are then assembled into a final vector in a single pot reaction [18].

Workflow Diagram: Modular Cloning (MoClo) Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Part Preparation: Clone each genetic part (e.g., orthogonal promoter, gene of interest, terminator) into specific "entry" vectors with flanking BsaI sites and unique 4-bp overhangs.

- Level 1 Assembly (Single TU): Mix a promoter, gene, and terminator plasmid in a single tube with BsaI-HFv2 restriction enzyme and T4 DNA ligase. Perform a Golden Gate reaction (e.g., 37°C for 5 mins, then 16°C for 5 mins, cycled 50 times, then 60°C for 10 mins, 80°C for 10 mins). This assembles a single, correct TU in an intermediate vector.

- Final Assembly (Multiple TUs): Mix the Level 1 TU plasmids (now flanked by connector sequences for multi-TU assembly) with the final destination vector in another Golden Gate reaction. This stitches all TUs into the final vector in the correct order.

- Screening: Transform the final assembly reaction into E. coli. Screen colonies for the loss of a GFP dropout cassette present in the backbone to easily identify correct assemblies (white colonies instead of green) [18].

Protocol: Measuring Orthogonality and Cross-Talk in a Multi-Component System

Principle: Systematically test each transcription factor against all non-cognate promoters to ensure that activation or repression only occurs with the intended partner [20].

Workflow Diagram: Orthogonality Testing Matrix

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Construct Reporter Library: Create reporter constructs where each orthogonal promoter drives the expression of a easily quantifiable output protein (e.g., GFP, YFP, RFP, luciferase).

- Express Individual Transcription Factors: Construct plasmids for the inducible expression of each orthogonal transcription factor (e.g., dCas9:VP64 with specific gRNAs, synTALEs, or λ cI variants).

- Co-transformation and Assay: Co-transform a single transcription factor plasmid with each member of the promoter-reporter library into your host organism. Include controls with no transcription factor.

- Quantification: For each combination, measure the reporter output under induced and uninduced conditions. Calculate the induction ratio (ON/OFF) for the intended pair.

- Data Analysis: A system is considered orthogonal if the induction ratio for the intended TF-promoter pair is high, while the output for all non-cognate pairs remains at baseline (uninduced) levels [18] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Orthogonal System Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Effector Fusions | Programmable DNA-binding chassis (e.g., dCas9:VP64 for activation, dCas9:KRAB for repression). | Core component for building CRISPR-based orthogonal transcription factors [18] [19]. |

| Synthetic Promoters (synPs / pATFs) | Minimal, de novo designed promoters containing specific binding sites for orthogonal TFs, with minimal host cross-talk. | Providing the regulatory DNA element that is selectively controlled by a synthetic TF and not by host factors [18] [19]. |

| Modular Cloning Toolkit (e.g., MoClo) | A standardized assembly system using Type IIS restriction enzymes (BsaI) for rapid, modular construction of multi-gene circuits. | Accelerating the design-build-test cycle for assembling complex genetic circuits with orthogonal parts [18]. |

| Orthogonal RNA Polymerases | Phage-derived RNAPs (e.g., T7, MmP1, K1F) that specifically transcribe genes under their cognate promoters. | Enabling orthogonal gene expression streams and in vivo mutagenesis systems, especially in non-model hosts [21]. |

| Non-Metabolizable Inducers | Chemical inducers that trigger expression but are not consumed by the host's metabolism (e.g., L-mannose for the engineered rhaBAD system). | Providing sustained induction and avoiding transient expression profiles caused by inducer depletion [22]. |

| Phagemid-Assisted Continuous Evolution (PACE) Systems | A platform for the directed evolution of biomolecules, linking desired activity to phage propagation. | Engineering non cross-reacting, orthogonal variants of transcription factors like λ cI [20]. |

| Pbrm1-BD2-IN-1 | Pbrm1-BD2-IN-1, MF:C17H19ClN2O, MW:302.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sos1-IN-12 | Sos1-IN-12|Potent SOS1 Inhibitor|For Research | Sos1-IN-12 is a potent SOS1 inhibitor that disrupts KRAS activation. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. |

Implementing Orthogonal Systems: A Toolkit for Multi-Gene Control Across Chassis

CRISPR/dCas9-Based Orthogonal Transcription Factors for Programmable Gene Activation

Orthogonal control in gene regulation refers to the design of synthetic genetic systems that operate independently from the host's native regulatory machinery. For CRISPR/dCas9-based transcription factors, this means creating activator-promoter pairs that function with minimal cross-talk with the host genome or with each other. This orthogonality is crucial for constructing complex genetic circuits and for precise manipulation of gene expression without unintended side effects [6] [24].

The foundational technology uses a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) protein, which retains its DNA-binding capability but lacks nuclease activity. When fused with transcriptional activation domains and guided by specific sgRNAs, dCas9 can be programmed to activate target genes. Orthogonal systems expand this concept by creating multiple, non-interacting dCas9/sgRNA/promoter combinations that can function simultaneously within the same cell [25] [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What constitutes an orthogonal transcription factor system in CRISPR/dCas9 applications? An orthogonal transcription factor system consists of multiple synthetic transcription factors and their corresponding synthetic promoters that function independently without cross-activation or cross-repression. True orthogonality requires that each dCas9/sgRNA complex activates only its intended synthetic promoter and does not interact with other synthetic promoters in the system or endogenous genomic regions. This is typically achieved through careful computational design of sgRNA sequences and their binding sites to minimize off-target interactions [6] [24].

Q2: Why is my dCas9 activator showing low activation efficiency despite optimal sgRNA design? Low activation efficiency can result from several factors. The binding position within the promoter region is critical - sites between -50 to -100 bp upstream of the transcription start site typically work best. The chromatin accessibility of the target region also significantly impacts efficiency. Additionally, using a single activation domain like VP64 may provide insufficient activation strength; consider upgraded systems like VPR (VP64-p65-Rta) or SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator) that incorporate multiple activation domains for stronger effects [27] [28].

Q3: How can I design multiple orthogonal CRISPR/dCas9 systems for simultaneous use? Designing orthogonal systems requires a multi-step computational approach. First, generate candidate sgRNA sequences and screen them against the host genome and circuit components using weighted Hamming distance metrics that account for mismatch sensitivity in the seed region. Select sequences with minimum off-target potential, then test mutual orthogonality between candidate pairs. Experimental validation should include testing all possible combinations to confirm absence of cross-talk [24].

Q4: What strategies can reduce off-target effects in CRISPR/dCas9 activation systems? Multiple strategies can mitigate off-target effects. Bioinformatic selection of sgRNAs with high specificity scores and appropriate GC content (40-60%) is essential. Using Cas9 variants with enhanced specificity, such as eSpCas9 or SpCas9-HF1, can reduce off-target binding. Fine-tuning the expression levels of dCas9 and sgRNA components also helps, as high concentrations increase off-target potential. Additionally, consider incorporating inducible systems that limit the duration of dCas9 expression [25] [29].

Q5: How can I make my orthogonal CRISPR system responsive to specific inducters? Inducible orthogonal systems can be created using chemically-induced dimerization domains. For example, coupling dCas9 activation to small molecules like rapamycin, abscisic acid, or gibberellin allows temporal control. These systems typically split the transcription factor components and fuse them to domains that dimerize only in the presence of the specific inducer, enabling precise control over the timing and duration of gene activation [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Gene Activation Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Suboptimal sgRNA binding position

- Cause: Weak activation domain

- Solution: Upgrade from basic VP64 to stronger activation systems like VPR (VP64-p65-Rta) or SAM (dCas9-VP64 with MS2-p65-HSF1 recruitment). The SAM system has demonstrated 10-100 fold improvements over dCas9-VP64 alone [28].

- Cause: Epigenetic silencing at target locus

Problem: Lack of Orthogonality (Cross-Talk Between Systems)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Insufficient specificity in sgRNA design

- Solution: Implement stricter computational screening using position-weighted mismatch scoring, with particular emphasis on seed region specificity (nucleotides 10-20 of the sgRNA). Ensure a minimum weighted Hamming distance of at least 5 against the host genome and 9 against circuit components [24].

- Cause: Overexpression of dCas9 components

- Cause: Similar promoter architecture across synthetic promoters

- Solution: Design synthetic promoters with varying architectures in terms of gRNA binding site numbers (3-4 sites shown effective) and spatial arrangements. Incorporate different core promoter elements to enhance orthogonality [6].

Problem: High Cytotoxicity or Cellular Stress

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Excessive transcriptional burden

- Cause: Off-target activation of oncogenes or stress response genes

- Solution: Conduct comprehensive off-target prediction using multiple algorithms and validate potential off-target sites using RNA-seq or specific PCR assays. Consider using cell-specific promoters to restrict expression to target cells [29].

- Cause: Viral vector toxicity

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Design and Assembly of Orthogonal CRISPR/dCas9 Systems

Objective: Create multiple non-interacting dCas9 activator-promoter pairs for orthogonal gene regulation.

Materials:

- dCas9-VPR or dCas9-SAM expression vector

- Modular cloning system (e.g., Golden Gate MoClo)

- sgRNA expression scaffolds with appropriate RNA aptamers (for SAM system)

- Synthetic promoter parts with minimal 35S core and transcription factor binding sites

Procedure:

- Computational Design: Generate candidate sgRNA sequences using orthogonal design algorithms that screen against host genome and circuit components with weighted Hamming distance metrics [24].

- Vector Assembly: Use modular cloning framework to assemble transcriptional units:

- Assemble synthetic promoters with 3-4 binding sites for corresponding sgRNAs upstream of minimal core promoter [6].

- Clone sgRNA expression cassettes with appropriate aptamer modifications (e.g., MS2, PP7) for recruiter systems.

- Assemble dCas9-activator fusions (dCas9-VPR or dCas9-VP64 for recruiter systems).

- Orthogonality Testing: Co-transfect each dCas9/sgRNA pair with all synthetic promoter reporters and measure activation specificity. Select pairs showing high on-target activation with minimal cross-talk.

- Validation: Test selected orthogonal pairs in the context of the intended genetic circuit or pathway manipulation.

Protocol: Quantitative Assessment of Orthogonal System Performance

Objective: Measure activation strength and specificity of orthogonal transcription factor systems.

Materials:

- Reporter constructs with orthogonal synthetic promoters driving fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP, etc.)

- dCas9 activator constructs

- sgRNA expression vectors

- Flow cytometer or fluorescence plate reader

Procedure:

- Transfection Setup: Plate cells in multi-well plates and co-transfect with:

- dCas9 activator construct

- sgRNA expression vector(s)

- Reporter construct(s)

- Control Samples: Include controls with individual components missing to establish baseline.

- Incubation: Incubate cells for 48-72 hours to allow gene expression.

- Quantification: Harvest cells and measure fluorescence intensity using flow cytometry or plate reader.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate fold-activation for each pair compared to controls.

- Compute orthogonality score as the ratio of on-target to off-target activation.

- Assess crosstalk by comparing unintended activation to intended activation.

Performance Data and System Comparisons

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR/dCas9 Activation Systems

| System | Components | Activation Fold | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-VP64 | dCas9-VP64 + sgRNA | 2-5x [27] | Simple design; Low size | Weak activation; Limited efficiency |

| dCas9-VPR | dCas9-VP64-p65-Rta + sgRNA | 50-300x [29] | Strong activation; Single sgRNA sufficient | Larger size; Potential cytotoxicity |

| SAM | dCas9-VP64 + MS2-p65-HSF1 + engineered sgRNA | 100-1000x [28] | Very high activation; Synergistic effect | Complex 3-component system |

| CRISPR-Assisted Trans Enhancer | dCas9-VP64 + csgRNA + sCMV enhancer | High (specific numbers not provided) | Uses strong CMV enhancer; Works on endogenous genes | Requires special csgRNA and sCMV components [30] |

| SunTag | dCas9-GCN4 + scFv-VP64 + sgRNA | Similar to VPR/SAM [30] | Modular recruitment; Amplified signal | Multi-component; Large genetic payload |

| Anticancer agent 51 | Anticancer agent 51, MF:C22H20F3N3O2S, MW:447.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Neuroinflammatory-IN-3 | Neuroinflammatory-IN-3|NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitor | Neuroinflammatory-IN-3 is a potent NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor for neuroscience research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Design Parameters for Orthogonal Systems

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA binding position | -50 to -200 bp from TSS [28] | Avoid positions downstream of TSS; Consider chromatin accessibility |

| Number of sgRNA binding sites | 3-4 sites per promoter [6] | More sites increase activation but may reduce orthogonality |

| sgRNA specificity score | Weighted Hamming distance ≥9 against circuit components [24] | Seed region (positions 10-20) requires perfect matching |

| sgRNA GC content | 40-60% [25] | Higher GC near PAM improves efficiency |

| Activation domain selection | VPR or SAM for strong activation [28] [29] | Balance strength with size constraints |

Signaling Pathways and System Architectures

Orthogonal CRISPR/dCas9 System Architecture

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Orthogonal CRISPR/dCas9 Systems

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Activation Domains | VP64, VP160, VPR (VP64-p65-Rta), p300 core | Transcriptional activation with varying strengths; VPR provides strongest activation [27] [31] |

| Synthetic Promoter Parts | Minimal 35S core, synthetic TF binding arrays, orthogonal core promoters | Create target promoters for orthogonal systems; minimal cores reduce background [6] |

| sgRNA Scaffold Modifications | MS2, PP7, com aptamers; tetraloop and stem-loop 2 engineering | Enable recruitment of additional activation domains (e.g., in SAM system) [28] |

| Inducible Systems | Light-inducible, chemically-inducible (rapamycin, gibberellin), tetracycline-controlled | Provide temporal control over dCas9 activity; reduce off-target effects [26] [29] |

| Delivery Tools | AAV vectors (size-optimized), lentiviral vectors, lipid nanoparticles | Enable efficient delivery of multi-component systems; AAV requires compact systems [30] [29] |

| Orthogonality Design Tools | Weighted Hamming distance algorithms, off-target prediction software | Computational design of specific sgRNAs with minimal cross-talk [24] |

Design and Engineering of Fully Synthetic Orthogonal Promoters

Fundamental Concepts and FAQs

What are fully synthetic orthogonal promoters?

Fully synthetic orthogonal promoters are artificially designed DNA sequences that control gene expression without interacting with the host's native regulatory networks. Unlike natural promoters, they are built from scratch using modular components: a core promoter region (containing TATA box and transcription start site) and synthetically arranged cis-regulatory elements (CREs) upstream. Their "orthogonal" nature means they are exclusively controlled by engineered transcription factors, such as CRISPR-based systems, ensuring minimal cross-talk with host cellular machinery [6] [32].

Why is orthogonality critical for synthetic biology applications?

Orthogonality prevents unwanted interactions between synthetic genetic circuits and the host organism's native genes. This isolation is crucial for predictable circuit behavior, as cross-talk can lead to:

- Severe growth and developmental defects in plants and other organisms [6]

- Loss of circuit function and unreliable performance [6]

- Unintended pleiotropic effects or epigenetic silencing of transgenes [32]

What are the key advantages of synthetic over native promoters?

- Precise Control: Enable spatiotemporal and inducible expression patterns unattainable with constitutive native promoters [32] [33]

- Reduced Metabolic Burden: Avoid unnecessary negative feedback and energy loss [32]

- Genetic Stability: Minimal sequence homology to the native genome reduces recombination and silencing events [34]

- Design Flexibility: Cis-element arrangement can be optimized for specific strength and inducibility [35] [32]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Low or No Transcriptional Activation

Problem: Your synthetic promoter shows weak or no activity despite the presence of your orthogonal transcription factor.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal cis-element spacing | Test constructs with 10-50 bp variations in spacing between CREs [32]. | Maintain minimum 50 bp between CREs and core promoter to avoid steric hindrance [32]. |

| Insufficient copy number of CREs | Build a series with 1-6 copies of the target CRE and measure reporter output [35]. | Use 3-4 copies of CREs for strong inducibility; higher copies may increase background [35]. |

| Inefficient gRNA binding (CRISPR systems) | Verify gRNA expression with Northern blot and test different gRNA scaffolds [6]. | Use validated Pol III promoters (e.g., U6) for gRNA expression and optimize gRNA binding sites [6]. |

High Background Expression (Leakiness)

Problem: Significant expression occurs even in the uninduced state or without the orthogonal transcription factor.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Too many CRE copies | Compare leakiness in constructs with 2 vs. 6 copies of the same CRE [35]. | Reduce CRE copies to 2-3; find the "sweet spot" balancing inducibility and background [35]. |

| Cryptic host TF binding sites | Scan synthetic sequence for host transcription factor motifs using databases like JASPAR. | Redesign synthetic promoter sequence to eliminate cryptic binding sites [34]. |

| Core promoter too strong | Test your CRE array with different minimal promoters (e.g., 35S mini vs. mas) [6]. | Use a weaker core promoter or incorporate synthetic insulators [32]. |

Lack of Orthogonality (Cross-talk)

Problem: Your synthetic promoter responds to endogenous cellular signals or affects native gene expression.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| CRE similarity to native elements | Test promoter activity in knockout strains of suspected endogenous TFs. | Use heterologous CREs from distant species and validate orthogonality systematically [36] [34]. |

| dCas9-VP64 off-target effects | Perform RNA-seq in cells expressing dCas9-VP64 without gRNAs. | Include control with catalytically dead dCas9 only; use higher-fidelity Cas9 variants [6]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Designing and Testing a Novel Synthetic Orthogonal Promoter

Principle: Create a synthetic promoter by assembling specific cis-regulatory elements upstream of a minimal core promoter, then validate its orthogonality and inducibility.

Materials:

- Modular Cloning (MoClo) system with Type IIS restriction enzymes (BsaI) [6]

- Agrobacterium shuttle vectors with selection markers (e.g., BASTA, hygromycin) [6]

- Reporter genes: GFP, YFP, RFP, or firefly luciferase (F-luc) [6]

- Nicotiana benthamiana plants for transient expression [6]

Procedure:

- Design Phase:

Assembly Phase:

- Use Golden Gate assembly with BsaI sites for modular construction [6]

- Assemble transcriptional unit in order: Synthetic promoter - Reporter gene - Terminator

- Clone into Agrobacterium binary vector with plant selection marker

Validation Phase:

- Transform Agrobacterium with final construct [6]

- Infiltrate Nicotiana benthamiana leaves for transient expression [6]

- Quantify reporter expression 2-4 days post-infiltration:

- Fluorescence imaging for fluorescent proteins

- Luciferase assays with substrate injection

- Test orthogonality by measuring expression without induction and against different orthogonal transcription factors

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If assembly fails: Verify BsaI site elimination in final construct and use fresh competent cells

- If expression is low: Test different copy numbers (3-6) of CREs and optimize spacing [35]

- If background is high: Reduce CRE copy number or try a weaker minimal promoter

Protocol: Establishing CRISPR/dCas9-Based Orthogonal Control

Principle: Implement orthogonal control by programming dCas9-VP64 artificial transcription factors to target synthetic promoters containing specific gRNA binding sites.

Materials:

- dCas9-VP64 fusion construct [6]

- gRNA expression vectors with U6 or other Pol III promoters [6]

- Synthetic promoters with programmed gRNA binding sites upstream of minimal 35S promoter [6]

Procedure:

- System Design:

- Engineer synthetic promoters with 3-4 repeats of specific gRNA binding sites [6]

- Place binding sites 50-100 bp upstream of minimal core promoter

- Design multiple gRNAs with different target sequences for orthogonal control

Vector Construction:

- Clone synthetic promoters upstream of reporter genes (GFP, YFP, RFP)

- Express dCas9-VP64 from a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., 35S)

- Express gRNAs from U6 or other Pol III promoters

Validation:

- Co-express dCas9-VP64, gRNAs, and reporter constructs in Nicotiana benthamiana

- Measure reporter expression 2-4 days post-infiltration

- Test specificity by measuring cross-activation between different gRNA-promoter pairs

- For inducible systems, place gRNA under chemical or hormone-inducible promoters (e.g., ethylene-responsive promoters) [6]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Tools for Synthetic Orthogonal Promoter Development

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Cloning Systems | Enables rapid assembly of genetic constructs | MoClo system with BsaI sites; YTK (Yeast Toolkit) adapted for plants [6] |

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors | Programmable regulators for synthetic promoters | dCas9-VP64 fusions; synthetic activators from Saccharomyces spp. [6] [36] |

| Minimal Core Promoters | Basal transcription machinery recruitment | 35S CaMV minimal promoter (-46 to +1 or -90 to +1); TATA-box containing minimal promoters [32] [33] |

| Reporter Genes | Quantitative measurement of promoter activity | GFP, YFP, RFP, BFP for fluorescence; Firefly luciferase (F-luc) for sensitive detection [6] |

| gRNA Expression Systems | Delivery of targeting molecules for CRISPR systems | Pol III promoters (U6, U3); ethylene-inducible Pol II promoters for conditional control [6] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Prediction and design of synthetic elements | AI models for expression prediction; CRE databases; motif analysis tools [37] [34] |

Dual Orthogonal Linearizer Circuits for Independent Control of Two Genes in Mammalian Cells

A fundamental challenge in synthetic biology and drug development is the precise, independent control of multiple gene expression levels within the same mammalian cell. Traditional methods, such as simple overexpression or knockdown, often lack the precision and uniformity needed to dissect complex phenotypic outcomes. Dual orthogonal linearizer circuits represent a significant advancement, enabling researchers to simultaneously and independently tune the expression of two genes with linear dose responses and low cell-to-cell variability. These systems utilize chemically inducible synthetic gene circuits built with orthogonal repressor proteins, allowing for the exploration of synergistic or epistatic gene interactions critical for therapeutic development and basic research. This technical support center provides troubleshooting and methodological guidance for implementing these powerful tools in your experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using a linearizer circuit over a standard inducible system like Tet-On? Standard inducible systems (e.g., Tet-On) often have a steep, non-linear dose-response curve, making it difficult to titrate a specific, intermediate level of gene expression. Linearizer circuits incorporate negative feedback to create a linear relationship between the inducer concentration and the output protein level. This results in precise, uniform expression across a cell population, which is essential for mapping gene expression levels to phenotypic outcomes [38] [39].

Q2: What does "orthogonal" mean in the context of these gene circuits? Orthogonality means that the two control systems operate independently without cross-talk. In a dual orthogonal linearizer system, the regulator protein (e.g., TetR) of one circuit does not interact with the promoter or inducer (e.g., Doxycycline) of the second circuit, and vice-versa. This allows you to modulate the expression of two different genes in the same cell without the systems interfering with each other [38] [1].

Q3: My circuit has high basal expression in the uninduced state. What could be the cause? High basal expression, or "leakiness," can occur due to several factors:

- Insufficient Repression: The repressor protein may not be expressed at a high enough level or may not bind strongly enough to its operator sites in your promoter construct. Using a promoter with two operator sites (e.g., PhlFd-mLin) instead of one can improve repression and lower basal levels [38].

- Promoter Strength: The chosen promoter may be inherently too strong. Consider testing a promoter with a different basal strength.

- Integration Site Effects: The genomic location where the circuit is integrated can influence its expression. Using a system like Flp-In to integrate the circuit into a consistent, well-characterized genomic locus can help minimize this variability [38].

Q4: I am not observing a linear dose-response in my experiment. How can I troubleshoot this? A non-linear response can be caused by:

- Incorrect Inducer Concentration Range: The linear range of the circuit might be outside the inducer concentrations you are testing. Consult the literature for your specific repressor protein and perform a broad dose-response experiment to identify the linear regime [38].