Molecular Scissors and Glue: How Restriction Enzymes and DNA Ligase Power Modern Cloning

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the indispensable roles restriction enzymes and DNA ligase play in molecular cloning, a cornerstone technique for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Molecular Scissors and Glue: How Restriction Enzymes and DNA Ligase Power Modern Cloning

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the indispensable roles restriction enzymes and DNA ligase play in molecular cloning, a cornerstone technique for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational science, from the historical discovery of restriction-modification systems to the precise molecular mechanisms of DNA cutting and joining. The scope extends to detailed methodological workflows for traditional and advanced cloning techniques, practical troubleshooting guides for common laboratory challenges, and a comparative analysis of modern assembly methods. By synthesizing established protocols with current applications in genomics and therapeutic development, this resource aims to be a definitive guide for efficiently designing, executing, and optimizing cloning experiments.

The Discovery and Mechanism: Understanding the Biology of DNA Cutting and Joining

The discovery of restriction and modification (R-M) systems represents a foundational pillar of modern molecular biology. What began as the observation of a puzzling bacteriophage behavior, termed "host-induced variation," evolved into the understanding of a sophisticated bacterial immune mechanism. This enzymatic system, capable of distinguishing between self and non-self DNA, provided the very tools that enabled the recombinant DNA revolution. This review details the historical trajectory of this discovery, from its genetic origins to the biochemical characterization of the enzymes, and frames its profound significance within the context of molecular cloning. The precise DNA cleavage by restriction endonucleases, coupled with the DNA-joining activity of DNA ligases, created the "cut-and-paste" methodology that underlies most genetic engineering and drug development workflows today.

In the early 1950s, scientists studying bacteriophages encountered a curious and non-hereditary phenomenon. Bacteriophages isolated from one bacterial strain showed a dramatically reduced ability to reproduce in a different strain, yet readily regained this ability after a single growth cycle on the original host [1]. This reversible change, initially termed host-controlled variation or host-induced variation, was first reported by Luria and Human in 1952 and by Bertani and Weigle in 1953 [2] [1]. The efficiency of plating (EOP) of phages on a restricting host could drop to values between 10⁻¹ and 10⁻⁵, indicating a potent, yet reversible, barrier to viral propagation [1]. This phenomenon, which would later be recognized as the genetic manifestation of R-M systems, set the stage for a series of investigations that would unravel a fundamental bacterial defense mechanism and ultimately provide the key tools for manipulating DNA in vitro.

The Genetic Foundation: Key Early Experiments

The initial genetic observations paved the way for more systematic studies that began to outline the molecular nature of host-controlled variation.

Establishing the DNA as the Carrier of Specificity

A critical leap in understanding came from the work of Werner Arber and Daisy Dussoix in 1962 [3]. Using bacteriophage λ as a model, they demonstrated that the phage DNA itself carried the host-range imprint. They observed that phage λ grown on E. coli K12 was restricted when plated on a K12(P1) lysogen (a strain lysogenized by bacteriophage P1), whereas the few progeny phage that did manage to grow were thereafter modified and could grow efficiently on the K12(P1) lysogen [3]. This modification was lost upon passage through a non-lysogenic strain, confirming that the effect was not due to mutation but to a reversible alteration of the DNA. Their work showed that bacterial cells could impart a specific "modification" to DNA that replicated within them, protecting it from "restriction" upon subsequent infection of the same cell type.

Discovery of the EcoP15 and EcoP1 Systems

Parallel genetic studies in E. coli 15T− revealed the presence of multiple, independent R-M systems. Kenneth Stacey and later Werner Arber's group identified that this strain possessed the chromosomal EcoA (Type I) system and a second, plasmid-borne system [3]. This second system, dubbed EcoP15, was found on the p15B plasmid and was closely related to the R-M system of bacteriophage P1 (EcoP1) [3]. These systems, later classified as Type III R-M systems, demonstrated that R-M genes could be encoded on mobile genetic elements and were not solely chromosomal attributes [3] [4].

Table 1: Key Early Experiments in the Discovery of R-M Systems

| Year | Researchers | Experimental System | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1952-1953 | Luria & Human; Bertani & Weigle | Various bacteriophages | Discovery of host-controlled variation as a non-hereditary phenomenon [2] [1]. |

| 1962 | Arber & Dussoix | Phage λ in E. coli K12 and K12(P1) | Identified DNA as the target of host-specific restriction and modification [3] [1]. |

| 1960s | Arber & Linn; Arber & Wauters-Williems | E. coli 15T− and plasmid p15B | Discovery of the EcoP15 R-M system on a plasmid, distinct from the chromosomal EcoA system [3]. |

| 1960s | Arber | Methionine-starved E. coli | Implicated S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and DNA methylation in the modification process [3]. |

| 1970 | Smith & Wilcox | Haemophilus influenzae | Iscribed the first Type II restriction enzyme (HindII), which cleaves DNA at specific sequences [2] [1]. |

| 1971 | Danna & Nathans | SV40 DNA + Endonuclease R | First use of a restriction enzyme to generate a physical map of a genome [2]. |

The Role of Methionine and DNA Methylation

Gunther Stent's suggestion that DNA methylation might be the basis for modification led to a crucial experiment. Arber and colleagues used methionine mutants (met⁻) of E. coli, which are deficient in the synthesis of S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM), the methyl group donor for most DNA methyltransferases [3]. They found that methionine starvation inhibited the modification function of the R-M system, thereby directly linking SAM-dependent DNA methylation to the host-specific modification of DNA [3] [1]. This finding connected the genetic phenomenon to a tangible biochemical process.

The Biochemical Revolution: From Concept to Enzyme

The theoretical framework for R-M systems was established by Werner Arber in 1965, who postulated that restriction enzymes would recognize specific DNA sequences and cleave them, while modification enzymes would methylate the same sequences to protect them [5] [1]. The subsequent isolation of these enzymes confirmed this model and opened a new era of molecular biology.

The First Restriction Enzymes

The first restriction enzymes to be isolated, such as those from E. coli K and B (EcoKI and EcoBI), were classified as Type I R-M systems [2] [1]. These complex enzymes recognized specific sequences but cleaved DNA at variable, often distant, locations, making them unsuitable for practical applications in DNA manipulation [2].

The pivotal breakthrough came in 1970 when Hamilton Smith and Kent Wilcox isolated a restriction enzyme from Haemophilus influenzae serotype d [2] [1]. This enzyme, initially called "endonuclease R," was found to cleave bacteriophage T7 DNA into specific fragments. It was the first characterized Type II restriction enzyme, defined by its ability to recognize a specific DNA sequence and cleave at a fixed location within or adjacent to that sequence [2]. Smith and Kelly soon determined its recognition sequence to be GTY↓RAC (where Y is C or T, R is A or G, and ↓ indicates the cleavage site) [2]. This enzyme was later named HindII.

A Powerful Combination: Restriction Enzymes and Gel Electrophoresis

The full potential of Type II enzymes was realized through the work of Daniel Nathans and Kathleen Danna. Using the enzyme preparation provided by Smith (which was later found to contain both HindII and HindIII), they digested the DNA of simian virus 40 (SV40) [2]. Instead of using sucrose gradients for analysis, they employed polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, a technique adapted from RNA separation methods [2]. This allowed them to resolve the digestion products into discrete, reproducible bands, creating the first "restriction map" [2]. This landmark 1971 paper demonstrated that restriction enzymes could be used to dissect genomes into specific fragments for mapping and analysis, a foundational technique for molecular cloning [2].

Table 2: Classification of Major Restriction-Modification System Types

| Type | Subunit Composition | Recognition Sequence | Cleavage Position | Cofactors | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | 3 subunits (R, M, S) | Bipartite (e.g., EcoKI: AACNNNNNNGTGC) | Variable, >1000 bp away [1] | ATP, SAM, Mg²⁺ [4] | Research |

| Type II | Separate R (homodimer) and M (monomer) enzymes | Short, palindromic (e.g., EcoRI: GAATTC) | Within or close to recognition site [4] | Mg²⁺ [4] | Molecular cloning, DNA analysis |

| Type IIS | Separate R and M enzymes | Asymmetric (e.g., BsaI: GGTCTC) | Outside ( downstream) of recognition site [6] | Mg²⁺ | Advanced DNA assembly (e.g., Golden Gate) |

| Type III | Heterocomplex (R₂M₂ or M₂R) [3] | Short, asymmetric (e.g., EcoP15I: CAGCAG) | 25-27 bp downstream of site [3] | ATP, (SAM?), Mg²⁺ [3] | Research |

| Type IV | Restriction enzyme only | Methylated DNA (e.g., McrBC: RmC) | Variable | GTP (for some) | Research on modified DNA |

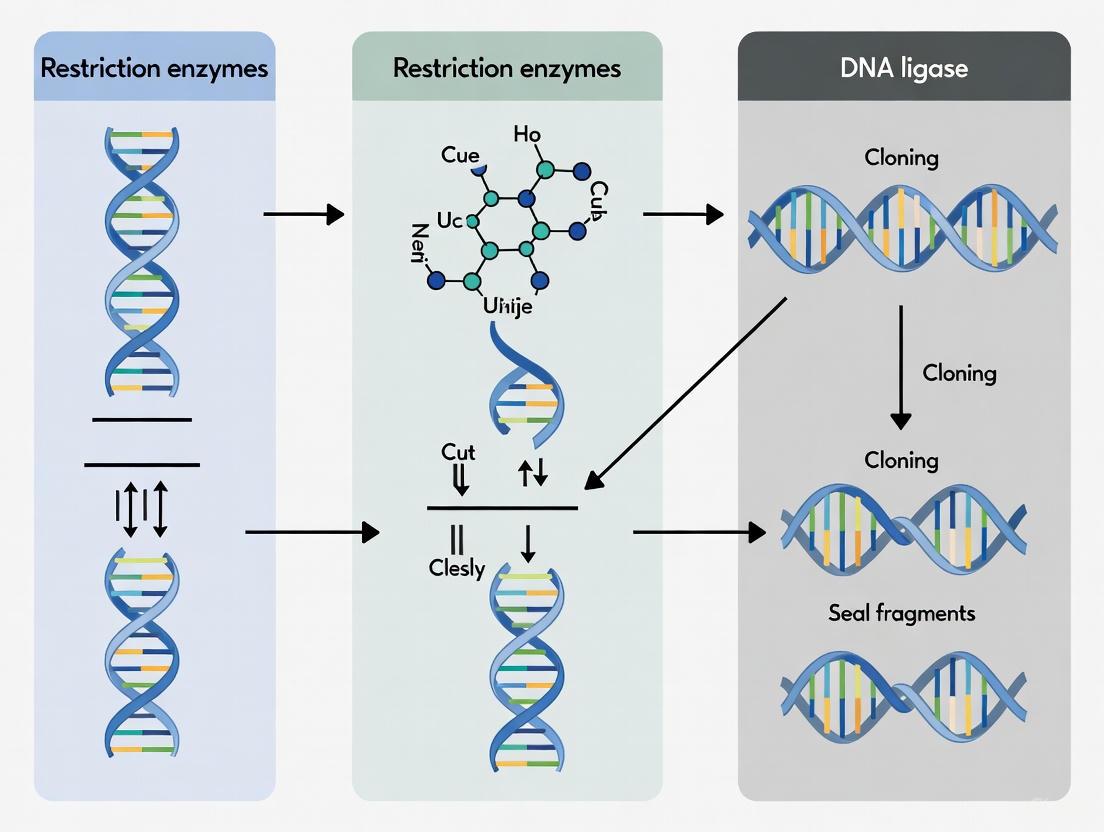

Diagram 1: The Historical Workflow from Phenomenon to Tool. This diagram outlines the key stages in the discovery and development of restriction-modification systems, from initial genetic observations to their application as essential tools in molecular biology.

The Core Technology for Molecular Cloning

The unique properties of Type II restriction enzymes made them ideal for recombinant DNA technology. Their simplicity—a restriction endonuclease for cutting and a separate, sequence-specific methyltransferase for protection—allowed scientists to use the REase in vitro to create defined DNA fragments.

The "Cut and Paste" Paradigm

Molecular cloning via restriction enzymes is a multi-step process that fundamentally relies on the specific cutting and pasting of DNA [7]:

- DNA Digestion: A plasmid vector and the DNA fragment of interest (insert) are cut with the same restriction enzyme(s).

- Ligation: The vector and insert are mixed and joined together by DNA ligase, an enzyme that catalyzes the formation of phosphodiester bonds, creating a recombinant DNA molecule.

- Transformation and Selection: The recombinant plasmid is introduced into a bacterial host (transformation). Bacteria containing the plasmid are selected using antibiotic resistance markers, and those with successful insertions are often identified via cloning selection markers (e.g., blue-white screening) [7].

This process, often called restriction cloning, allows for the precise insertion of a gene into a self-replicating vector for amplification and study [7].

Directional Cloning and Advanced Applications

Early cloning often used a single restriction enzyme, which led to inserts ligating in either orientation. Directional cloning, which uses two different restriction enzymes to create non-compatible ends on the vector and insert, ensures the insert is ligated in the correct orientation and significantly reduces background [7]. Further advancements leveraged Type IIS restriction enzymes, which cut outside of their recognition sequence. This property is exploited in techniques like Golden Gate Assembly, which allows for the seamless, one-pot assembly of multiple DNA fragments without incorporating the restriction site into the final construct [6] [5].

Diagram 2: The Cloning Workflow and its Applications. This diagram illustrates the core "cut and paste" process of restriction enzyme cloning, from digestion and ligation to the creation of a recombinant plasmid, and outlines its major applications in biotechnology and medicine.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Protocols

The practical application of this historical discovery relies on a standardized set of reagents and methodologies.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Restriction Enzyme-Based Cloning

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Cloning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIP Restriction Enzymes | Cut vector and insert DNA at specific palindromic sequences to generate compatible ends. | EcoRI, HindIII, BamHI [6] [7] |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | Cut outside recognition site; enable advanced, seamless assembly of DNA fragments. | BsaI, BsmBI, Esp3I [6] |

| DNA Ligase | Joins the sugar-phosphate backbones of the digested vector and insert fragments. | T4 DNA Ligase [7] |

| Plasmid Cloning Vector | A circular DNA molecule containing an Origin of Replication (ORI), Selectable Marker (e.g., Amp⁺), and a Multi-Cloning Site (MCS). | pBR322, pUC19 [7] |

| Competent Cells | Chemically or electroporation-treated bacterial cells capable of taking up foreign DNA. | E. coli DH5α, BL21(DE3) |

| Selection Media | Growth media containing an antibiotic to select for bacteria that have taken up the plasmid vector. | LB + Ampicillin [7] |

Detailed Protocol: Basic Restriction Cloning

The following methodology outlines a standard restriction enzyme cloning procedure for inserting a DNA fragment into a plasmid vector [7].

Experimental Design and In Silico Simulation:

- Select a plasmid vector with a Multi-Cloning Site (MCS).

- Choose restriction enzymes that cut uniquely in the vector MCS and at the ends of your insert. For directional cloning, use two different enzymes.

- Use software to simulate the digestion and confirm the final recombinant plasmid sequence.

Digestion of Vector and Insert:

- Set up separate reactions for the vector and insert DNA.

- Reaction Mix: 1 µg DNA, 1X Restriction Enzyme Buffer, 10-20 units of each restriction enzyme, Nuclease-free water to final volume.

- Incubation: 1 hour at the enzyme's optimal temperature (typically 37°C).

Purification of Digested Products:

- Run the digestion products on an agarose gel.

- Excise the bands corresponding to the linearized vector and the insert.

- Purify the DNA from the gel slices using a gel extraction kit. Quantify the purified DNA.

Ligation:

- Reaction Mix: 50 ng linearized vector, insert DNA (at a 3:1 molar ratio of insert:vector), 1X DNA Ligase Buffer, 1 µL T4 DNA Ligase, Water to final volume.

- Incubation: 10-30 minutes at room temperature or 16°C for 1-2 hours.

Transformation and Selection:

- Add the ligation mixture to chemically competent E. coli cells. Incubate on ice, heat-shock at 42°C for 30-45 seconds, and return to ice.

- Add recovery media and incubate with shaking for 1 hour.

- Plate the transformation mixture onto agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotic.

- Incubate plates overnight at 37°C.

Screening and Verification:

- Pick individual colonies and grow in small cultures.

- Isolate plasmid DNA (mini-prep).

- Verify the presence and correctness of the insert by restriction digest (analytical gel) and DNA sequencing.

The journey from the observation of host-induced variation to the elucidation of the restriction-modification system is a testament to the power of fundamental scientific research. The discovery of Type II restriction enzymes provided the precise molecular scissors that, when combined with DNA ligase, enabled the controlled manipulation of DNA. This "cut-and-paste" methodology lies at the heart of molecular cloning, forming the technical foundation for the entire biotechnology industry. The cloning and production of therapeutic proteins like human insulin, the mapping of disease genes, and the development of advanced gene therapies all trace their origins to the bacterial immune system and the curious scientists who sought to understand it. As new cloning techniques emerge, the historical and practical framework established by restriction enzymes remains a cornerstone of genetic engineering and drug development.

Restriction endonucleases, often termed "molecular scissors," are enzymatic tools that recognize specific DNA sequences and catalyze the cleavage of double-stranded DNA. These enzymes form the foundation of recombinant DNA technology, enabling the precise manipulation of genetic material essential for cloning research. This technical guide explores the molecular mechanisms underlying their sequence-specific recognition and cleavage activities, detailing how the ends they generate are leveraged by DNA ligase to construct novel recombinant molecules. We provide a comprehensive analysis of enzyme classes, quantitative cleavage data, standardized experimental protocols, and essential reagent solutions to support research and drug development applications.

Restriction endonucleases are fundamental tools in molecular biology, with their natural function serving as a defense mechanism in bacterial cells against invading viral DNA (bacteriophages). The restriction-modification (R-M) system functions through the coordinated activity of two enzymes: a restriction enzyme that cleaves foreign, unmethylated DNA, and a methyltransferase that modifies the host's own DNA by adding methyl groups to specific bases within the recognition sequences, thereby protecting it from cleavage [8] [9]. This selective cleavage ensures that only foreign DNA is targeted and degraded, while the host DNA remains intact. The functionality of restriction enzymes extends beyond this native bacterial immune role, with pivotal applications in genetic engineering processes where they provide the foundational mechanism for DNA manipulation [8].

The discovery of restriction enzymes dates back to the 1950s and 1960s, when researchers observed that bacteriophages exhibited host-controlled variation in their ability to infect different bacterial strains [9] [2]. Werner Arber proposed the restriction-modification system, suggesting that host DNA was protected through methylation while foreign viral DNA was cleaved by restriction enzymes. The full potential of restriction enzymes became apparent with the discovery of Type II restriction enzymes by Hamilton Smith and Kent Wilcox, which cleave DNA at specific symmetrical sequences within their recognition sites [9] [2]. This pioneering work, which earned Daniel Nathans, Hamilton Smith, and Werner Arber the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, laid the groundwork for modern molecular cloning techniques [9].

Classification and Mechanisms of Restriction Enzymes

Restriction enzymes are categorized based on their structural complexity, recognition sequence characteristics, cleavage site position, and cofactor requirements. Understanding these classifications is crucial for selecting appropriate enzymes for specific experimental applications.

Enzyme Classes and Characteristics

Table 1: Classification and characteristics of restriction endonucleases

| Enzyme Class | Recognition Sequence | Cleavage Site | Cofactor Requirements | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Asymmetric and bipartite | Variable distance from recognition site (≥1000 bp) | ATP, Mg²⁺, AdoMet | Limited research applications |

| Type II | Specific palindromic sequences (4-8 bp) | Within or close to recognition site | Mg²⁺ | Molecular cloning, DNA analysis, RFLP |

| Type IIS | Asymmetric sequences | Outside of recognition site (1-20 bp away) | Mg²⁺ | Golden Gate Assembly, advanced DNA assembly |

| Type III | Short asymmetric sequences | Specific distance (24-26 bp) from recognition site | ATP, Mg²⁺ | Limited research applications |

| Type IV | Methylated DNA | Approximately 30 bp from recognition site | Mg²⁺ | Methylation studies |

Molecular Mechanisms of Sequence Recognition and Cleavage

Type II restriction enzymes, the most commonly used class in molecular biology, achieve sequence-specific recognition through intimate interactions between protein domains and specific nucleotide bases within their target sequences. These enzymes typically recognize short palindromic sequences of 4-8 base pairs in length, reading the DNA sequence through a combination of hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and structural complementarity with the DNA double helix [9]. The precise molecular recognition process varies among enzyme families, with some employing a "direct readout" mechanism where amino acid side chains form specific contacts with nucleotide bases, while others use "indirect readout" by sensing sequence-dependent DNA conformation and flexibility.

The cleavage mechanism involves coordinated hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bonds in both DNA strands. Most Type II enzymes generate breaks that produce either sticky ends (5′ or 3′ protruding termini) or blunt ends (evenly cut ends without overhangs) [9]. Sticky ends are particularly valuable in cloning applications as the complementary overhangs facilitate specific annealing of DNA fragments before ligation. The cleavage reaction requires Mg²⁺ as a cofactor, which activates water molecules for nucleophilic attack on the phosphate groups in the DNA backbone and stabilizes the transition state during hydrolysis.

Type IIS restriction enzymes represent a particularly valuable subclass that recognize asymmetric sequences and cleave outside of their recognition site [8]. This unique property enables greater flexibility in DNA assembly, as the cleavage site can be designed independently of the recognition sequence. As explained by Bill Jack, an Emeritus Scientist at New England Biolabs: "Many Type IIS enzymes, when they cut, leave a staggered overhang. Since the single-stranded overhang is not defined by the restriction site, it can be essentially any set of nucleotides, and so, there's a great ability to order the type of sequence or the type of overhang that will be there to allow assembly" [8]. This characteristic makes Type IIS enzymes particularly valuable for advanced cloning techniques such as Golden Gate Assembly, which enables complex DNA assemblies with high efficiency and accuracy [8].

Experimental Applications and Methodologies

Core Restriction Enzyme-Based Protocols

Standard Restriction Digestion and Ligation Protocol

The foundational protocol for molecular cloning involves digesting both the vector and insert DNA with restriction enzymes that generate compatible ends, followed by ligation with DNA ligase to create recombinant molecules.

Materials Required:

- Purified DNA vector and insert

- Appropriate restriction enzymes with compatible buffers

- DNA ligase (typically T4 DNA ligase)

- ATP (cofactor for ligation)

- Thermostable DNA polymerase with proofreading capability for amplification

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

- DNA purification kits or reagents

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Select a cloning vector with an appropriate multiple cloning site (MCS) containing unique restriction sites not present in your insert DNA [10]. Choose restriction enzymes that generate compatible ends for both vector and insert.

- DNA Digestion: Set up separate digestion reactions for vector and insert DNA using the selected restriction enzymes. A typical 50 μL reaction contains:

- 1 μg DNA

- 1× restriction enzyme buffer

- 10-20 units of each restriction enzyme

- Nuclease-free water to volume

- Incubate at the recommended temperature (usually 37°C) for 1-2 hours [9]

- Fragment Purification: Separate digested fragments by agarose gel electrophoresis and extract the desired bands using gel extraction kits to isolate vector and insert fragments.

- Ligation: Combine the purified vector and insert fragments in a molar ratio (typically 1:3 vector:insert) with DNA ligase. A standard 20 μL ligation reaction contains:

- 50-100 ng vector DNA

- Appropriate molar amount of insert DNA

- 1× ligation buffer

- 1 mM ATP

- 1-5 units T4 DNA ligase

- Incubate at 16°C for 4-16 hours [10]

- Transformation and Screening: Transform the ligation reaction into competent bacterial cells, plate on selective media, and screen resulting colonies for correct recombinants using colony PCR or restriction analysis.

Advanced Application: HIV-1 Gag Gene Cloning for Replication Studies

This specialized protocol demonstrates how restriction enzyme-based cloning can be applied to study viral replication capacity, specifically for HIV-1 subtype C gag genes [11].

Materials Required:

- Viral RNA from HIV-1 infected plasma

- MJ4 subtype C HIV-1 proviral backbone

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase with proofreading capability

- Restriction enzymes for insertion into MJ4 vector

- CEM-CCR5 T-cell line for replication assays

- Radiolabeled reverse transcriptase assay components

Methodology:

- RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis: Extract viral RNA from 140 μL thawed HIV-1 infected plasma using a commercial extraction kit. Perform reverse transcription immediately after extraction to maximize RNA integrity [11].

- Nested PCR Amplification: Amplify the gag gene using a two-step nested PCR approach with high-fidelity DNA polymerase to minimize PCR-introduced errors:

- First-round PCR: Use one-step RT-PCR with outer primers

- Second-round PCR: Use 1 μL of first-round product as template with nested primers containing appropriate restriction sites for cloning [11]

- Restriction Digestion and Cloning: Digest both the PCR-amplified gag gene and MJ4 proviral backbone with selected restriction enzymes. Purify fragments and ligate using T4 DNA ligase.

- Virus Production: Transfect recombinant proviral constructs into 293T cells using appropriate transfection reagents. Harvest virus supernatants after 72 hours.

- Replication Capacity Assay: Infect CEM-CCR5 T-cells with normalized virus stocks and monitor replication over 7-10 days using radiolabeled reverse transcriptase assays to quantify virus production [11].

Figure 1: HIV-1 Gag Gene Cloning and Assessment Workflow. This diagram illustrates the key steps in the restriction enzyme-based cloning method for studying HIV-1 replication capacity, from RNA extraction to functional assessment [11].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key research reagents for restriction enzyme-based experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | HindII, EcoRI, BamHI, BsaI-HFv2, BsmBI-v2 | Sequence-specific DNA cleavage for fragmentation and vector linearization | Select based on recognition sequence, cutting frequency, and end type (sticky vs blunt) |

| DNA Ligases | T4 DNA Ligase | Joins compatible DNA ends by catalyzing phosphodiester bond formation | Requires ATP cofactor; works optimally with complementary overhangs |

| DNA Polymerases | High-fidelity proofreading enzymes (e.g., Q5, Phusion) | Amplify DNA fragments with minimal errors for cloning | Critical for PCR amplification of inserts prior to restriction digestion |

| Cloning Vectors | Plasmid vectors with MCS (Multiple Cloning Sites) | Serve as carrier molecules for DNA fragments | MCS contains multiple unique restriction sites for flexible cloning strategies |

| Competent Cells | E. coli strains (DH5α, BL21) | Host organisms for plasmid propagation after ligation | Transformation efficiency critical for obtaining sufficient recombinant clones |

Advanced DNA Assembly Techniques

Golden Gate Assembly

Golden Gate Assembly represents a significant advancement in restriction enzyme-based cloning, leveraging Type IIS restriction enzymes to enable efficient, one-pot assembly of multiple DNA fragments. This technique exploits the unique property of Type IIS enzymes, which cleave outside of their recognition sequence, allowing custom overhangs to be designed for precise fragment assembly [8]. The method typically uses enzymes such as BsaI-HFv2 or BsmBI-v2, which create 4-base overhangs that can be specifically designed for each fragment junction.

The Golden Gate reaction combines the Type IIS restriction enzyme and DNA ligase in a single-tube reaction, with cycles of digestion and ligation enabling directional assembly of multiple fragments. As Bill Jack explains: "Since the single-stranded overhang is not defined by the restriction site, it can be essentially any set of nucleotides, and so, there's a great ability to order the type of sequence or the type of overhang that will be there to allow assembly" [8]. This approach overcomes limitations of traditional cloning by placing restriction sites outside the fragments of interest, allowing seamless assembly without incorporating extra nucleotides at junctions.

The development of new restriction enzymes and improved understanding of ligase fidelity have made Golden Gate Assembly remarkably efficient, with fragment assemblies achieving >90% accuracy and high efficiency [8]. NEB's Ligase Fidelity Tools further aid in designing high-fidelity Golden Gate Assemblies by optimizing experimental conditions. These advances have enabled sophisticated applications in synthetic biology, including construction of complex genetic circuits and metabolic pathways.

Restriction Enzyme Applications Beyond Cloning

While essential for molecular cloning, restriction enzymes serve critical functions in other molecular biology applications:

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) Analysis: RFLP was one of the first DNA fingerprinting methods, relying on restriction enzyme digestion to detect variations in DNA sequences between individuals [12]. The technique involves digesting genomic DNA with restriction enzymes, separating fragments by gel electrophoresis, transferring to membranes (Southern blotting), and hybridizing with labeled probes to reveal unique fingerprint patterns. RFLP markers have been widely used in genetic counseling, forensic analysis, and studying genetic diversity.

DNA Methylation Analysis: Some restriction enzymes are sensitive to DNA methylation, enabling their use in epigenetic studies [12]. Enzymes such as HpaII, which cleaves unmethylated CCGG sites but not methylated ones, allow researchers to map methylation patterns across genomes. This application is particularly valuable for studying epigenetic regulation in development and disease, including cancer research where aberrant methylation patterns are common.

Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP): AFLP combines restriction digestion with PCR amplification to generate genetic fingerprints without prior sequence knowledge [12]. Genomic DNA is digested with two restriction enzymes (typically a rare-cutter like EcoRI and a frequent-cutter like MseI), followed by ligation of adapters and selective PCR amplification. The resulting fragment patterns provide robust markers for genetic mapping, phylogenetic studies, and population genetics.

Restriction endonucleases remain indispensable tools in molecular biology, providing the foundation for DNA manipulation through their precise sequence-specific cleavage activities. From their initial discovery as bacterial defense mechanisms to their current status as workhorses of genetic engineering, these molecular scissors have continuously evolved to meet the demands of increasingly sophisticated research applications. Their synergy with DNA ligase enables the construction of recombinant DNA molecules that form the basis of modern cloning technologies, from basic plasmid construction to advanced assembly methods like Golden Gate cloning.

The continued development of novel restriction enzymes, particularly Type IIS variants with their enhanced flexibility, ensures that these molecular tools will remain relevant in the era of synthetic biology and precision genome engineering. As research progresses, the fundamental principles of restriction and ligation continue to underpin new methodologies, maintaining the central role of these enzymes in advancing both basic research and therapeutic development. For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding the mechanisms and applications of restriction endonucleases remains essential for designing effective genetic engineering strategies and interpreting experimental results in molecular cloning research.

In molecular cloning, the precise manipulation of DNA fragments relies fundamentally on the nature of their terminal ends. Restriction endonucleases, often described as "molecular scissors," cleave DNA at specific sequences to generate these defined ends [13] [9]. DNA ligase then functions as the "molecular glue," catalyzing the formation of phosphodiester bonds to join compatible ends together [14]. This restriction-ligation process forms the cornerstone of recombinant DNA technology, enabling researchers to create novel genetic constructs for applications ranging from basic biological research to pharmaceutical development [9]. The efficiency and outcome of these enzymatic reactions are profoundly influenced by whether the DNA fragments possess sticky ends or blunt ends—a fundamental distinction that dictates experimental design, efficiency, and success in cloning workflows [15] [14]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these DNA end types, their generation, and their strategic implications for research and drug development.

Defining DNA Ends: Structural Characteristics and Formation

Sticky Ends (Cohesive Ends)

Sticky ends, or cohesive ends, are characterized by short, single-stranded DNA overhangs that result from staggered cuts made by restriction enzymes in the double-stranded DNA backbone [13] [15]. These overhangs are typically complementary palindromic sequences, allowing fragments from different origins to associate through hydrogen bonding before being permanently sealed by DNA ligase [13] [15]. The overhangs can be either 5' or 3' protrusions, depending on the specific restriction enzyme used [14]. The discovery of sticky ends by Ronald W. Davis as a product of EcoRI action revolutionized molecular biology by providing a mechanism for precise and efficient joining of DNA fragments [15].

Blunt Ends (Non-Cohesive Ends)

Blunt ends occur when both strands of a DNA molecule are cut at equivalent positions, resulting in terminal ends with no unpaired bases [13] [15] [16]. This straight-across cleavage pattern generates fragments that are universally compatible but lack the stabilizing hydrogen bonds that facilitate fragment association in sticky-end ligations [13] [16]. The absence of these complementary interactions makes the ligation process significantly less efficient and more challenging to control [16] [17].

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Sticky Ends vs. Blunt Ends

| Characteristic | Sticky Ends | Blunt Ends |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Short, single-stranded overhangs (5' or 3') | No overhangs; both strands end at same base position |

| Formation | Staggered cuts by restriction enzymes (e.g., EcoRI, BamHI) | Straight-across cuts by restriction enzymes (e.g., SmaI, EcoRV) [16] |

| Complementarity | Sequence-specific; must be compatible for ligation | Universally compatible with any blunt end |

| Ligation Efficiency | High (due to hydrogen bonding stabilization) | Low (10-100 times less efficient) [16] [17] |

| Directional Cloning | Possible with non-complementary overhangs | Not inherently possible without additional modifications [16] [14] |

| Common Applications | Standard cloning, directional insertion | PCR product cloning, library construction when sticky ends are unavailable |

Enzymatic Formation of DNA Ends

Restriction endonucleases are classified into four major types (I-IV) based on their structural complexity, recognition sites, cleavage positions, and cofactor requirements [13] [9]. Type II restriction enzymes are the workhorses of molecular cloning, as they recognize specific palindromic sequences and cleave at predictable positions within or near these recognition sites [9]. While most Type II enzymes (Type IIP) recognize and cut within palindromic sequences, Type IIS enzymes recognize asymmetric sequences and cut at a defined distance outside them, a property exploited in advanced techniques like Golden Gate assembly [13].

The following diagram illustrates how different restriction enzymes generate sticky versus blunt ends through their distinct cleavage patterns:

Practical Implications for Cloning Research and Drug Development

Ligation Efficiency and Experimental Design

The choice between sticky-end and blunt-end cloning strategies has profound implications for experimental efficiency and design. Sticky-end ligations benefit from hydrogen bonding between complementary overhangs, which stabilizes the DNA fragment association and increases ligation efficiency by 10 to 100-fold compared to blunt-end ligations [16] [17]. This efficiency advantage translates to higher transformation yields and reduced screening effort. For blunt-end ligations, the absence of this stabilizing interaction means successful ligation depends on transient associations between 5' phosphate and 3' hydroxyl groups being captured at the right moment by DNA ligase [17]. This necessitates optimized reaction conditions including higher DNA concentrations, increased ligase amounts, longer incubation times, and often the use of crowding agents like polyethylene glycol (PEG) to improve efficiency [18] [17].

Directional Cloning and Vector Considerations

Directional cloning, which ensures inserts are oriented correctly in vectors, is readily achievable with sticky ends by using two different restriction enzymes that generate incompatible ends on each side of the insert [14]. This approach forces the insert into the vector in a single orientation, saving significant time in downstream screening and validation. In contrast, blunt ends are universally compatible but lack inherent directionality, resulting in a 50% chance of incorrect insertion orientation for each transformant [16]. Advanced techniques such as using monophosphorylated vectors and inserts or implementing selection systems like Staby technology can overcome this limitation, but they add complexity to the experimental design [16].

Vector re-circularization presents another significant consideration. In blunt-end cloning, intramolecular ligation (vector self-ligation) competes effectively with the desired insert-vector intermolecular ligation [16] [17]. This background can be minimized by dephosphorylating the vector ends using alkaline phosphatases (e.g., CIP, SAP, or BAP) to remove 5'-phosphate groups, preventing recircularization [16] [17]. Concurrently, ensuring the insert contains 5'-phosphate groups is essential for successful ligation, which may require phosphorylation of PCR-generated inserts using T4 polynucleotide kinase [16] [17].

Strategic Applications in Research and Drug Development

The different properties of sticky and blunt ends make them suitable for distinct applications in research and pharmaceutical development:

Sticky-end cloning is preferred for standard molecular biology applications where efficiency and directional control are priorities, such as constructing expression vectors for recombinant protein production—a critical step in biopharmaceutical development [14].

Blunt-end cloning is invaluable when working with DNA fragments that lack convenient restriction sites or when multiple internal restriction sites preclude the use of traditional sticky-end approaches [16]. This versatility makes blunt-end cloning essential for library construction and cloning PCR products, particularly those generated with proofreading polymerases that produce blunt-ended fragments [16].

Golden Gate assembly represents an advanced application that leverages Type IIS restriction enzymes, which create custom sticky ends outside their recognition sites [13]. This technique enables seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction and is particularly valuable in synthetic biology applications, including metabolic pathway engineering for therapeutic compound production [13].

Table 2: Optimization Strategies for Different DNA End Types

| Parameter | Sticky-End Ligation | Blunt-End Ligation |

|---|---|---|

| Insert:Vector Ratio | 1:1 to 3:1 (standard) [18] | 10:1 or higher to favor intermolecular ligation [14] |

| Ligase Type/Amount | Standard T4 DNA Ligase (1-1.5 Weiss units) [18] | High-concentration T4 DNA Ligase (1.5-5.0 Weiss units) [14] |

| Reaction Additives | Standard buffer components | PEG 4000 as molecular crowding agent [14] [17] |

| Incubation Time | 10 minutes to 1 hour at 22°C [14] | Up to 24 hours to increase collision probability [17] |

| Phosphorylation State | Standard phosphorylation usually sufficient | Often requires vector dephosphorylation and insert phosphorylation [16] [17] |

| Typical Efficiency | High (benchmark) | 10-100 times lower than sticky ends [16] [17] |

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Restriction Digestion Protocol

The following protocol provides a reliable method for generating either sticky or blunt ends through restriction enzyme digestion [19]:

Reaction Setup: In a sterile microcentrifuge tube, combine the following components:

- 1 μg DNA (plasmid or genomic)

- 2 μL 10X restriction enzyme buffer

- 1 μL restriction enzyme (10 units)

- Nuclease-free water to 20 μL total volume

Digestion: Mix thoroughly by pipetting and centrifuge briefly. Incubate at the enzyme's optimal temperature (typically 37°C) for 1-4 hours.

Verification: Analyze digestion completeness by agarose gel electrophoresis alongside undigested DNA and appropriate size markers.

Critical Considerations:

- Ensure DNA is free from contaminants such as phenol, ethanol, or detergents that may inhibit enzyme activity [19].

- For double digests with two different enzymes, verify compatibility of buffer and temperature requirements [19].

- For enzymes that do not heat-inactivate effectively, purify DNA after digestion using spin columns or phenol/chloroform extraction before proceeding to ligation [19].

Optimized Ligation Workflow

The ligation process differs significantly between sticky-end and blunt-end fragments. The following workflow outlines a standardized approach adaptable to both scenarios [18] [14] [17]:

Blunt-End Specific Optimizations:

- Implement a two-step incubation: 1 hour with high insert concentration followed by dilution (1:20) and extended incubation to favor complete circularization while minimizing concatemer formation [17].

- For PCR-generated inserts, verify the phosphorylation status. Fragments amplified with proofreading polymerases lack 5'-phosphates and require treatment with T4 polynucleotide kinase before ligation [16] [14].

- When using Taq polymerase-generated fragments with 3'A overhangs for blunt-end cloning, remove the overhangs using proofreading polymerase treatment (e.g., Pfu) before ligation [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA End Manipulation

| Reagent | Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Type II Restriction Enzymes | Recognize and cleave specific DNA sequences | Generating sticky or blunt ends for cloning [13] [9] |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Catalyzes phosphodiester bond formation | Joining DNA fragments with compatible ends [18] [14] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (CIP, SAP) | Removes 5'-phosphate groups | Preventing vector self-ligation in blunt-end cloning [16] [17] |

| T4 Polynucleotide Kinase | Adds 5'-phosphate groups | Phosphoryrating PCR inserts for ligation [16] [14] |

| PEG 4000 | Molecular crowding agent | Increasing effective concentration in blunt-end ligations [14] [17] |

| DNA Polymerases (T4, Klenow) | Fills or removes single-stranded DNA | Converting sticky ends to blunt ends; end repair [16] |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

Type IIS Restriction Enzymes and Golden Gate Assembly

Type IIS restriction enzymes represent a powerful tool for advanced cloning strategies. Unlike conventional Type IIP enzymes that cut within their recognition sites, Type IIS enzymes recognize asymmetric DNA sequences and cleave at a defined distance outside these sequences [13]. This unique property enables Golden Gate assembly, a method that allows seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction [13]. In this technique, both inserts and destination vectors contain compatible cleavage sites that generate custom complementary overhangs, enabling precise assembly of up to 35 DNA fragments in the desired order [13]. The recognition sites are positioned such that they are removed from the final construct, eliminating the need for scar sequences and making this approach particularly valuable for sophisticated genetic engineering applications in pharmaceutical development and synthetic biology [13].

Isoschizomers and Neoschizomers in Experimental Design

The availability of isoschizomers (different enzymes that recognize and cleave the same sequence) and neoschizomers (enzymes that recognize the same sequence but cleave at different positions) provides valuable flexibility in experimental design [13]. For example, SmaI and XmaI both recognize the sequence 5'-CCCGGG-3', but SmaI generates blunt ends (CCC↓GGG) while XmaI produces sticky ends (C↓CCGGG) [13]. Isoschizomers may offer advantages such as improved stability, reduced cost, different methylation sensitivities, or absence of star activity (relaxed specificity under suboptimal conditions) [13]. This enzyme diversity enables researchers to select the most appropriate restriction endonuclease based on the specific type of DNA end required for their application.

Implications for Drug Development and Biotechnology

The precise manipulation of DNA ends underpins many advanced applications in biotechnology and pharmaceutical development. In plant genetic engineering, Golden Gate assembly facilitates the construction of complex synthetic constructs for metabolic pathway engineering and genome editing [13]. For therapeutic protein production, control over DNA end joining ensures correct open reading frame maintenance and optimal expression cassette design. The emerging field of gene therapy relies on sophisticated vector construction where the specificity of DNA end joining ensures proper transgene integration and expression. As these technologies advance, the fundamental principles governing DNA end recognition and joining continue to inform the development of more efficient and precise genetic engineering tools for therapeutic applications.

The strategic manipulation of DNA ends represents a foundational skill in molecular biology with far-reaching implications for research and drug development. Sticky ends offer efficiency and directional control through complementary hydrogen bonding, while blunt ends provide versatility at the cost of reduced ligation efficiency. The choice between these approaches depends on multiple factors, including the source DNA, available restriction sites, desired insert orientation, and downstream applications. Mastery of both standard and specialized techniques—from basic restriction cloning to advanced Golden Gate assembly—enables researchers to tackle increasingly complex genetic engineering challenges. As molecular techniques continue to evolve, the precise control over DNA fragment joining remains central to innovations across biological research, therapeutic development, and biotechnology.

This technical guide explores the critical role of DNA ligase in molecular cloning, framing it as the indispensable "paste" function that complements the "cut" function of restriction enzymes. We delve into the enzymatic mechanism of phosphodiester bond reformation, detail the types and applications of DNA ligases in research and drug development, and provide optimized protocols for modern cloning workflows. The integral partnership between restriction enzymes and DNA ligase has powered the recombinant DNA revolution, enabling the construction of novel genetic entities for therapeutic and research purposes. This whitepaper provides researchers with a comprehensive resource on ligase biology and practical methodologies to enhance cloning efficiency.

The revolutionary development of molecular cloning rests on a foundational paradigm: the ability to specifically cut and paste DNA sequences. Restriction enzymes serve as precise molecular scissors, recognizing and cleaving DNA at specific palindromic sequences to generate defined fragments [20] [2]. These catalytic proteins, originally discovered as a bacterial defense mechanism against invading bacteriophages, create either blunt ends or cohesive "sticky" ends with short, single-stranded overhangs that enable specific re-association through base-pair complementarity [20] [10].

However, cleavage alone is insufficient for recombinant DNA technology. The final and crucial step—the "pasting" function—is catalyzed by DNA ligase, an enzyme that seals the sugar-phosphate backbone between adjacent nucleotides [21] [10]. In living organisms, DNA ligases are essential for DNA replication, particularly in joining Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand, and for various DNA repair pathways [21] [22]. In vitro, this sealing function enables the stable insertion of DNA fragments into cloning vectors, forming recombinant molecules that can be amplified and expressed in host organisms [22] [10]. The synergistic partnership between restriction enzymes and DNA ligase has thus been the cornerstone of genetic engineering for decades, enabling everything from basic gene mapping to the production of life-saving biologic drugs [2] [10].

The Molecular Mechanism of DNA Ligase

The Phosphodiester Bond: Foundation of DNA Integrity

A phosphodiester bond is a covalent linkage in which a phosphate group forms two ester-like connections, bridging the 3' hydroxyl (-OH) group of one nucleotide to the 5' phosphate (PO₄) group of the adjacent nucleotide [23] [24]. This creates the characteristic sugar-phosphate backbone of DNA and RNA, with the nucleotide bases projecting from this backbone to form the genetic code [23]. The stability of this bond is crucial for genetic integrity, though its susceptibility to hydrolysis varies depending on flanking nucleotides; for instance, phosphodiester bonds adjacent to pyrimidine-purine sequences (e.g., UA and CA) demonstrate notably higher instability [24].

The Enzymatic Steps of Bond Reformation

DNA ligase catalyzes the formation of phosphodiester bonds in a three-step mechanism that requires energy from either ATP (eukaryotic and T4 ligases) or NAD+ (prokaryotic ligases) [21] [25] [22]. The reaction proceeds as follows:

- Adenylation: The ligase reacts with ATP (or NAD+), releasing pyrophosphate (or nicotinamide mononucleotide) and forming a covalent intermediate where AMP becomes attached to a conserved lysine residue within the enzyme's active site [21] [22].

- Transfer to DNA: The AMP group is subsequently transferred from the enzyme to the 5' phosphate terminus of the "donor" DNA strand, forming a high-energy DNA-adenylate intermediate (AppDNA) [21] [25].

- Nucleophilic Attack and Ligation: The 3' hydroxyl group of the "acceptor" DNA strand initiates a nucleophilic attack on the activated 5' phosphate. This results in the formation of a phosphodiester bond, sealing the DNA nick and releasing AMP [21] [25] [22].

This mechanism is conserved across DNA ligases, though cofactor requirements and specific biological roles differ among enzyme types.

Mechanism of DNA Ligase

The following diagram illustrates the three-step enzymatic mechanism by which DNA ligase reforms the phosphodiester bond, from initial adenylation to final bond formation.

Types of DNA Ligases and Their Applications

Classification and Characteristics

Various DNA ligases have been isolated and are utilized in molecular biology, each with distinct properties that make them suitable for specific applications. The following table summarizes key ligases and their characteristics.

Table 1: Types of DNA Ligases and Their Properties

| Ligase Type | Natural Source | Cofactor | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T4 DNA Ligase | Bacteriophage T4 | ATP | General molecular cloning, blunt & sticky-end ligation, RNA ligation [21] | Most commonly used in labs; ligates blunt ends and cohesive ends; can join RNA-DNA hybrids [21] |

| E. coli DNA Ligase | Escherichia coli | NAD+ | Cohesive-end ligation, in vivo repair [21] | Efficient for sticky ends; less efficient for blunt ends unless under molecular crowding conditions [21] |

| DNA Ligase 1 | Mammals | ATP | Okazaki fragment joining, nuclear DNA repair [21] | Essential for DNA replication; seals nicks in the lagging strand [21] |

| DNA Ligase 3 | Mammals | ATP | Base excision repair, mitochondrial DNA repair [21] | Complexes with XRCC1; only mammalian ligase found in mitochondria [21] |

| DNA Ligase 4 | Mammals | ATP | Non-homologous end joining, V(D)J recombination [21] | Complexes with XRCC4; critical for double-strand break repair and immune system development [21] |

| Thermostable Ligase | Thermophilic bacteria | ATP/NAD+ | PCR-based ligation, detection methods [21] [22] | Stable at high temperatures (>65°C); essential for techniques requiring thermal cycling [21] |

DNA Ligase in Advanced Cloning Techniques

While traditional cloning relies on complementary ends generated by restriction enzymes, advanced techniques leverage the precision of specialized ligases. Golden Gate Assembly is a prominent example that uses Type IIS restriction enzymes, which cut outside their recognition sequence, in conjunction with T4 DNA ligase to enable efficient one-pot assembly of multiple DNA fragments [20]. This method allows for the creation of complex genetic constructs with high efficiency and accuracy, often exceeding 90% success rates [20]. The technique's success depends on the synchronized activity of the restriction enzyme and DNA ligase, facilitated by thermal cycling between their optimal activity temperatures.

Practical Guide: Experimental Protocols for DNA Ligation

Standard Ligation Reaction Setup

A typical ligation reaction involves combining the vector, insert, ligase enzyme, and reaction buffer under optimal conditions. The following table provides a standardized protocol for both sticky-end and blunt-end ligations, which require different optimization strategies.

Table 2: Standardized Ligation Reaction Setup and Conditions

| Reaction Component | Sticky-End Ligation | Blunt-End Ligation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector DNA | 20–100 ng | 20–100 ng | Determine concentration spectrophotometrically |

| Insert DNA | x ng (see ratio calc.) | x ng (see ratio calc.) | 5'-phosphorylation is critical [14] |

| 10X Ligation Buffer | 2 µL | 2 µL | Contains ATP, DTT; freeze-thaw sensitive [14] |

| 50% PEG 4000 | Optional | 2 µL | Crowding agent critical for blunt-end efficiency [14] |

| T4 DNA Ligase | 1.0–1.5 Weiss Units | 1.5–5.0 Weiss Units | Higher concentration needed for blunt ends [14] |

| Nuclease-free Water | to 20 µL | to 20 µL | Dilutes potential inhibitors |

| Incubation | 10 min–1 hr at 22°C | 10 min–1 hr at 22°C | Overnight not typically required [14] |

Critical Optimization Parameters

- Insert:Vector Molar Ratio: The optimal ratio is contingent upon the downstream application and must be determined empirically [14]. A 3:1 ratio is a common starting point for sticky-end ligations, while blunt-end ligations often require higher ratios (e.g., 10:1) to drive the less efficient reaction [14]. The required mass of insert for a 1:1 molar ratio can be calculated as: (ng of vector × length of insert (bp)) ÷ length of vector (bp) [14].

- End Compatibility: For successful ligation, DNA ends must be properly prepared. Sticky ends must be complementary, and 5'-phosphate groups must be present on at least one strand to be joined [14]. PCR products generated by proofreading polymerases lack 5' phosphates and require treatment with T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK) prior to ligation [14].

- Reaction Temperature and Time: While T4 DNA ligase has optimal activity at 37°C, ligation of cohesive ends is often performed at lower temperatures (16–25°C) to stabilize the annealing of short overhangs [21] [14]. Prolonged incubations are generally unnecessary due to the enzyme's high efficiency, with 10 minutes to one hour typically sufficient [14].

Molecular Cloning Workflow

The following diagram outlines the complete workflow for a standard restriction-ligation cloning experiment, from initial DNA preparation to verification of the recombinant construct.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DNA Ligation

Successful DNA ligation experiments require a suite of specialized reagents and enzymes. The following table catalogs essential solutions for the molecular biologist's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Ligation

| Reagent / Enzyme | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins double-stranded DNA fragments with cohesive or blunt ends [21] [14] | Requires ATP and Mg²⁺ as cofactors; most versatile for laboratory use [21] |

| Restriction Enzymes (Type II) | Generate specific cleavage patterns in DNA to create compatible ends for ligation [20] [2] | Selection determines end type (blunt or sticky); unique site in vector is essential [10] |

| T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK) | Adds 5' phosphate groups to DNA fragments, essential for ligating PCR products [14] | Critical when using DNA fragments synthesized by proofreading polymerases [14] |

| PEG 4000 | Molecular crowding agent that dramatically increases ligation efficiency, especially for blunt ends [14] | Included in specialized ligation buffers; promotes macromolecular association [14] |

| ATP | Essential cofactor for T4 DNA ligase activity; provides energy for phosphodiester bond formation [21] [25] | Degrades upon freeze-thaw cycles; requires stable buffer aliquots [14] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (CIP, SAP) | Removes 5' phosphate groups from vectors to prevent self-ligation [14] | Used for vector dephosphorylation to reduce background during cloning [14] |

| DNA Ligase Buffer | Provides optimal ionic conditions (Mg²⁺), ATP, and DTT (reducing agent) for ligase activity [14] | DTT is oxygen-sensitive; aliquot storage is recommended to maintain efficacy [14] |

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Common Challenges and Solutions

Even well-designed ligation experiments can encounter obstacles. Key troubleshooting considerations include:

- Low Efficiency: This can result from insufficient 5' phosphorylation, suboptimal insert:vector ratios, or inadequate ligase concentration. Verify fragment phosphorylation status and perform a ratio titration series (e.g., 1:1, 3:1, 10:1) [14]. For blunt-end ligations, ensure the inclusion of PEG and higher ligase concentrations [14].

- Inhibitor Presence: Common contaminants like salts, EDTA, phenol, ethanol, or excess glycerol can inhibit ligase activity [14]. Ensure proper DNA purification and use recommended reaction volumes (e.g., 20 µL) to dilute potential inhibitors [14].

- Vector Self-Ligation: High background from re-circularized vector without insert can be mitigated by dephosphorylating the vector with alkaline phosphatase prior to ligation [14].

Verification of Ligation Products

Confirming successful ligation is a critical step before proceeding to cellular transformation. Multiple analytical methods can be employed:

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Allows for visualization of ligation products based on size shift; the ligated vector-insert construct should migrate more slowly than the linearized vector alone [22].

- PCR and Sequencing: Colony PCR using insert-specific primers can screen for successful recombinants. Sanger sequencing or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) provides definitive confirmation of the correct ligation product and reading frame [22].

- Enzymatic Assays: Bioluminescent-based assays can quantitatively measure ligation activity and efficiency by detecting ATP consumption or other reaction products [22].

DNA ligase, functioning as the molecular paste that reforms the phosphodiester bond, remains an indispensable component of the genetic engineering toolkit. Its synergy with restriction enzymes has enabled the cloning and manipulation of DNA sequences, forming the technical foundation for modern biologic drug development, functional genomics, and synthetic biology. As cloning techniques evolve toward more complex and high-throughput assemblies, such as Golden Gate and other modular methods, the precision and efficiency of DNA ligation continue to be paramount. A deep understanding of ligase mechanics, types, and reaction optimization—as detailed in this guide—empowers researchers to design and execute robust cloning strategies that accelerate scientific discovery and therapeutic innovation.

In the realm of molecular biology, plasmid vectors serve as fundamental vehicles for gene cloning and manipulation, enabling researchers to study and engineer genetic material. These small, circular DNA molecules replicate independently of the host's chromosomal DNA and have become indispensable tools for life scientists and bioengineers [26]. The process of molecular cloning, which involves making multiple copies of a specific DNA fragment, relies heavily on plasmid vectors to receive, replicate, and express foreign DNA inserts in host cells such as bacteria [7]. This technical guide examines the three core characteristics of plasmid vectors—the origin of replication, selectable markers, and multiple cloning site (MCS)—and frames their function within the essential biochemical context of restriction enzymes and DNA ligase, the enzymes that make recombinant DNA technology possible.

The significance of plasmid vectors extends across diverse applications, from basic research to therapeutic development. Historically, the discovery of restriction enzymes and DNA ligase in the 1970s enabled the creation of the first recombinant DNA molecules, revolutionizing biological research [7]. Today, more than 70% of all molecular biology experiments begin with the restriction cloning of DNA fragments into plasmid vectors [7]. These experiments underpin advancements such as the production of therapeutic proteins like human insulin, the development of CRISPR-based genome editing tools, and the generation of disease-resistant crops [7]. Understanding the key features of plasmid vectors is therefore crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage genetic engineering in their work.

Fundamental Components of Plasmid Vectors

Origin of Replication (ORI)

The origin of replication (ORI) is a specific DNA sequence that enables the initiation of plasmid replication within a host cell by recruiting the necessary replication machinery proteins [26]. This element controls two critical parameters: host range (which organisms can replicate the plasmid) and copy number (the number of plasmid copies maintained per cell) [26]. The copy number varies significantly between different ORI types, directly influencing plasmid yield. High-copy-number plasmids (e.g., pUC series with 500-700 copies/cell) are preferred when large quantities of DNA are required, while low-copy-number plasmids (e.g., pSC101 with ~5 copies/cell) offer greater stability for maintaining hard-to-clone inserts [27]. The choice of ORI must align with experimental goals, as it impacts both DNA yield and the metabolic burden placed on the host cell [27].

Table 1: Common Origin of Replication Types and Their Characteristics

| Origin Type | Approximate Copy Number | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| pUC | 500-700 | High-copy | High-yield DNA preparation |

| pBR322 | 15-20 | Medium-copy | General cloning |

| pSC101 | ~5 | Low-copy | Stable maintenance of large inserts |

| ColE1 | 15-60 | Medium-copy | General molecular biology |

Selectable Marker (Antibiotic Resistance Gene)

The selectable marker, typically an antibiotic resistance gene, enables researchers to identify and isolate cells that have successfully taken up the plasmid after transformation [27]. This selection occurs when transformed cells are grown on media containing a specific antibiotic—only those expressing the resistance gene will survive and form colonies [28]. Common antibiotic resistance genes include those conferring resistance to ampicillin (AmpR), kanamycin (KanR), and tetracycline (TetR) [27]. The choice of selection marker depends on the host system; while antibiotic resistance is standard for bacterial systems, other selection principles apply to different organisms. For example, in yeast, markers often complement nutritional deficiencies by encoding enzymes for biosynthesis of essential nutrients, allowing growth in selective media [28].

Table 2: Common Selectable Markers in Plasmid Vectors

| Antibiotic | Resistance Gene | Mechanism of Action | Selection Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | bla (AmpR) | Inhibits cell wall synthesis | Only resistant bacteria grow |

| Kanamycin | KanR (nptII) | Disrupts protein synthesis | Only resistant bacteria grow |

| Tetracycline | TetR | Inhibits protein synthesis | Only resistant bacteria grow |

Multiple Cloning Site (MCS)

The multiple cloning site (MCS), also known as a polylinker, is a short DNA segment containing numerous unique restriction enzyme recognition sequences [28]. This feature provides flexibility for inserting foreign DNA fragments at precise locations within the plasmid [27]. In expression vectors, the MCS is strategically positioned downstream of a promoter region, ensuring that any inserted gene is properly oriented and positioned for transcription [26]. The MCS typically contains restriction sites for 5-20 different enzymes, with each site appearing only once in the entire plasmid to ensure specific and predictable cutting [7]. While traditional restriction cloning relies on MCS, some modern cloning methods like Golden Gate Assembly or Gibson Assembly may not require a conventional MCS [28].

The Enzymatic Machinery: Restriction Enzymes and DNA Ligase

The utility of plasmid vectors depends entirely on two classes of enzymes: restriction enzymes that cut DNA at specific sequences, and DNA ligases that join DNA fragments together. These enzymes provide the molecular "scissors and glue" that enable precise DNA manipulation.

Restriction Enzymes: Molecular Scissors

Restriction enzymes, also known as restriction endonucleases, recognize specific short DNA sequences (typically 4-8 base pairs) and cleave both strands of the DNA molecule at or near these recognition sites [28]. These enzymes are categorized into three main types based on their cleavage characteristics, with Type IIP enzymes serving as the workhorses of molecular cloning due to their predictable cutting at fixed positions relative to their recognition sites [7]. Restriction enzymes generate three types of DNA ends: 5' protruding ends (overhangs), 3' protruding ends, or blunt ends with no overhangs [7]. The complementary nature of "sticky ends" (5' or 3' overhangs) allows DNA fragments from different sources cut with the same enzyme to anneal through specific base pairing.

Table 3: Types of Restriction Enzymes and Their Applications

| Enzyme Type | Cleavage Characteristics | Ends Generated | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type IIP | Cut at specific, fixed positions within recognition site | 5' overhang, 3' overhang, or blunt | EcoRI (5' overhang), PstI (3' overhang), SmaI (blunt) |

| Type IIS | Cut at defined positions outside recognition site | Custom overhangs | BsaI, BbsI |

| Type IIB | Cut on both sides of recognition site | Fragments without recognition site | BcgI |

DNA Ligase: Molecular Glue

DNA ligase catalyzes the formation of a phosphodiester bond between adjacent 3'-hydroxyl and 5'-phosphate termini in DNA strands, effectively "gluing" DNA fragments together [21]. The ligation mechanism proceeds through three steps: adenylylation of a lysine residue in the enzyme's active site, transfer of AMP to the 5' phosphate of the DNA donor fragment, and finally formation of the phosphodiester bond between the donor and acceptor fragments [21]. Different DNA ligases have varying properties and applications: T4 DNA ligase (from bacteriophage T4) is most common in research, can ligate both cohesive and blunt ends, and requires ATP as a cofactor [21]. E. coli DNA ligase uses NAD+ instead of ATP and is less efficient with blunt ends, while thermostable DNA ligases from thermophilic bacteria remain stable at high temperatures, enabling specialized applications [21].

Diagram: Restriction enzymes cut plasmid and insert DNA, while DNA ligase joins them to form a recombinant plasmid.

Experimental Framework: Restriction Cloning Protocol

The following section provides detailed methodologies for performing restriction cloning, from initial planning to verification of the final construct.

Experimental Planning and Vector Selection

Successful restriction cloning begins with careful experimental design. Researchers must select an appropriate plasmid backbone containing the necessary elements for their application: origin of replication compatible with the host, relevant selectable marker, and MCS with suitable restriction sites [7]. Two primary cloning strategies are employed: single enzyme cloning uses one restriction enzyme to cut both vector and insert, but does not control insert orientation; dual enzyme (directional) cloning uses two different enzymes to ensure the insert is placed in the correct orientation and reduces background from vector self-ligation [7] [29]. Directional cloning is generally preferred as it guarantees proper orientation, which is critical for gene expression applications [29].

Step-by-Step Protocol

Restriction Digest: Set up separate restriction digest reactions for the plasmid backbone (1μg) and insert DNA (1.5-2μg) using the selected restriction enzymes. Ensure digestion proceeds to completion by following manufacturer recommendations for duration and conditions. Fast-digest enzymes may complete digestion in 10 minutes, while conventional enzymes may require several hours [29].

Gel Purification: After digestion, separate the DNA fragments by agarose gel electrophoresis. Visualize DNA using stains like SYBR Safe (sensitivity: 0.5ng), GelRed (sensitivity: 0.1ng), or ethidium bromide (sensitivity: 0.5ng) [29]. Excise the gel slices containing the linearized vector and insert fragments, then purify using a gel extraction kit. This critical step removes enzymes, buffer, and unwanted DNA fragments while allowing quantification of recovered DNA [29].

Ligation: Mix the purified vector and insert fragments in a molar ratio typically between 1:3 to 1:10 (vector:insert), with approximately 100ng total DNA in the reaction. For blunt-end ligations or very small inserts, higher insert ratios (10:1 to 20:1) may be necessary [7] [29]. Include a negative control with vector alone to assess background. Add DNA ligase (T4 DNA ligase is standard) and incubate at 16°C for several hours or overnight. For single-enzyme cloning, treat the vector with phosphatase (CIP or SAP) prior to ligation to prevent self-ligation [29].

Transformation: Introduce the ligation reaction into competent bacterial cells (e.g., DH5α, TOP10) following manufacturer protocols. For most applications, 1-2μL of ligation reaction transformed into chemically competent cells is sufficient. For large constructs (>10kb) or when using very little DNA, consider electro-competent cells for higher efficiency [29].

Selection and Screening: Plate transformed cells on antibiotic-containing agar plates corresponding to the plasmid's resistance marker. Incubate overnight at 37°C. A successful ligation typically shows many colonies on the vector+insert plate and few on the vector-only control plate [29]. Pick 3-10 colonies for further analysis.

Verification: Purify plasmid DNA from selected colonies via miniprep. Verify successful cloning through diagnostic restriction digest (cutting with the original enzymes should release the insert) [29] and sequence critical regions (especially insert-vector junctions) using primers flanking the MCS [7].

Diagram: Restriction cloning workflow from planning to verification.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Restriction Cloning Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Cloning |

|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | EcoRI, HindIII, BamHI, XhoI | Cut DNA at specific sequences to generate compatible ends |

| DNA Ligase | T4 DNA Ligase | Joins vector and insert DNA fragments covalently |

| Competent Cells | DH5α, TOP10, BL21 | Host cells for plasmid transformation and propagation |

| Antibiotics | Ampicillin, Kanamycin | Selection of successfully transformed cells |

| DNA Purification Kits | Gel extraction, Miniprep kits | Purify DNA fragments from gels or bacterial cultures |

| DNA Ladders | 1kb DNA ladder, 100bp ladder | Size standards for agarose gel electrophoresis |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with careful planning, restriction cloning can encounter challenges. Common issues include insufficient colonies, high background (colonies without insert), or incorrect constructs. If few or no colonies appear, verify transformation efficiency with a positive control, ensure antibiotic is fresh and correct, and confirm DNA quality and concentration [29]. High background on the vector-only control indicates insufficient phosphatase treatment or incomplete digestion—optimize restriction enzyme concentration and duration, and ensure phosphatase is properly inactivated [29]. For verification failures, sequence the entire insert and junction regions to identify mutations, deletions, or orientation problems. Always use fresh, high-quality reagents and consider using higher-fidelity enzymes for critical applications. Band purification of fragments after restriction digest is the most effective way to eliminate uncut vector and small fragments, significantly improving ligation efficiency [7].

Plasmid vectors, with their precisely engineered components—origin of replication, selectable markers, and multiple cloning site—remain fundamental tools in molecular biology and biotechnology. Their functionality is intrinsically linked to the enzymatic actions of restriction enzymes and DNA ligase, which together enable the precise cutting and joining of DNA fragments that underpin recombinant DNA technology. As detailed in this guide, successful implementation of restriction cloning requires careful experimental planning, optimization of reaction conditions, and thorough verification of final constructs. While newer cloning methods have emerged, restriction cloning continues to be widely used due to its simplicity, reliability, and the extensive resources available to support it. Understanding these core principles and components empowers researchers to design and execute effective genetic engineering strategies across diverse applications, from basic research to therapeutic development.

From Theory to Bench: A Step-by-Step Guide to Restriction/Ligation Cloning and Its Applications

Molecular cloning, a cornerstone technique of modern biological research and drug development, relies fundamentally on the precise activities of restriction enzymes and DNA ligase. These enzymes provide the molecular tools for cutting and reassembling DNA, enabling researchers to create recombinant DNA molecules for a vast array of applications, from protein expression to gene therapy development [30]. Restriction enzymes serve as highly specific molecular scissors, while DNA ligase acts as a molecular glue, covalently joining DNA fragments [30] [31]. The strategic selection of restriction enzymes is therefore a critical first step in experimental design, directly influencing the efficiency, orientation, and ultimate success of the cloning procedure. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for selecting restriction enzymes and designing robust directional cloning strategies, with a focus on applications relevant to research scientists and drug development professionals.

Core Principles of Restriction Enzyme Selection

The selection of appropriate restriction enzymes extends beyond merely identifying sites that flank a DNA insert. A strategic approach involves evaluating several key enzyme properties and their compatibility with the experimental goal.

Types of Restriction Ends and Their Compatibility

Restriction enzymes are categorized based on the type of ends they generate, which dictates how DNA fragments can be joined [30] [7]. The table below summarizes the primary types of ends and their ligation compatibility.

Table 1: Types of Restriction Enzyme Ends and Their Characteristics

| End Type | Description | Ligation Compatibility | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5' Protruding (Overhang) | Creates a short, single-stranded sequence at the 5' end of the DNA strand [7]. | Joins only to a complementary 5' overhang generated by the same or a different enzyme that produces the same sequence [7]. | Offers high efficiency; complementary overhangs stabilize the association before ligation [31]. |