Minimizing Indel Mutations in Genome Editing: Strategies for Enhanced Fidelity in Therapeutic Development

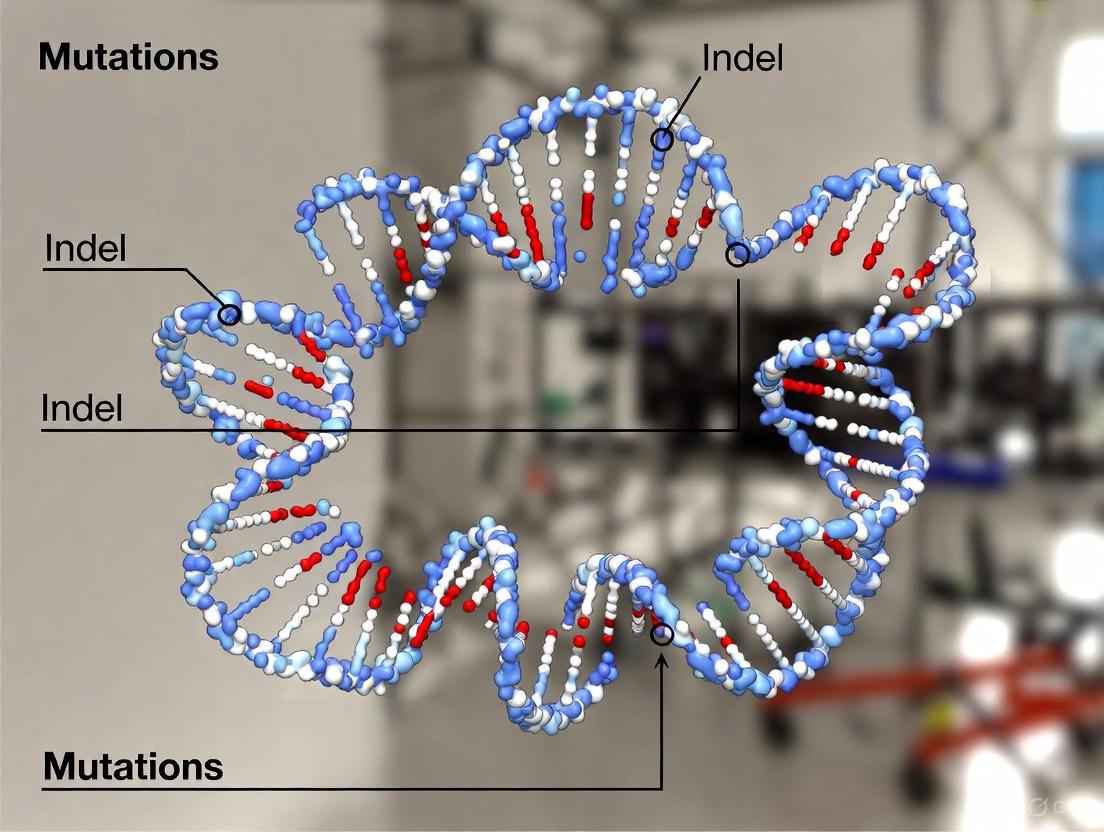

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of insertion/deletion (indel) mutations, a significant byproduct of CRISPR-based genome editing that poses challenges for research and therapeutic applications.

Minimizing Indel Mutations in Genome Editing: Strategies for Enhanced Fidelity in Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of insertion/deletion (indel) mutations, a significant byproduct of CRISPR-based genome editing that poses challenges for research and therapeutic applications. We explore the fundamental mechanisms driving indel formation, from error-prone DNA repair pathways to recently discovered large-scale structural variations. The content details the latest engineered editors, including prime editors and high-fidelity Cas variants, that dramatically reduce indel frequencies. Methodological sections cover advanced detection technologies and optimization strategies for suppressing indels across various editing platforms. Finally, we examine rigorous validation frameworks and comparative performance of emerging editing systems, offering researchers and drug development professionals a practical guide for achieving precise genomic modifications with minimal unintended mutations.

Understanding Indel Mutations: Origins, Mechanisms, and Genomic Risks

In CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing, the genetic modifications you aim to create are not actually performed by the Cas9 nuclease itself. Cas9 acts merely as a pair of "molecular scissors" that creates a precise double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA. The actual editing outcome is determined by the cell's endogenous DNA damage repair (DDR) pathways that are harnessed to join the two cut ends back together. The competition between these pathways—primarily the error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and the precise Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)—directly dictates whether your experiment successfully creates a precise edit or results in unintended insertions and deletions (indels). Understanding this interplay is fundamental to designing, executing, and troubleshooting gene editing experiments. This guide provides a focused FAQ and troubleshooting resource for researchers navigating indel formation within the broader context of addressing mutations in editing research.

Core Mechanisms: NHEJ and HDR

What are the fundamental differences between NHEJ and HDR?

Answer: NHEJ and HDR are distinct cellular mechanisms for repairing double-strand breaks, characterized by different fidelity, template requirements, and efficiency.

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This is a fast, efficient, but error-prone pathway. It operates throughout the cell cycle by directly ligating the two broken DNA ends together without the need for a homologous template. This process often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair site. These indels can disrupt gene function, making NHEJ the preferred pathway for generating gene knockouts [1] [2].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This is a precise, high-fidelity mechanism that uses a homologous DNA sequence as a template for repair, such as a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor template. HDR is ideal for introducing specific sequence changes, such as point mutations, gene corrections, or knockins (e.g., inserting a fluorescent protein tag). However, HDR is less efficient than NHEJ and is restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, where a homologous template is naturally available [1] [3].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each pathway.

Table 1: Comparison of NHEJ and HDR Key Characteristics

| Feature | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Template Required | No | Yes (e.g., sister chromatid, donor DNA) |

| Fidelity | Error-prone (often generates indels) | High-fidelity (precise) |

| Efficiency | High | Low |

| Cell Cycle Phase | Active throughout all phases | Primarily restricted to S and G2 phases |

| Primary Application in Gene Editing | Gene knockouts | Precise knockins, point mutations, gene corrections |

How do NHEJ and HDR pathways operate at the molecular level?

Answer: The following diagrams illustrate the core molecular workflows for NHEJ and HDR pathways following a CRISPR/Cas9-induced double-strand break.

Diagram 1: NHEJ Pathway for Indel Formation. This error-prone repair leads to gene knockouts.

Diagram 2: HDR Pathway for Precise Editing. This high-fidelity repair requires a donor template.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Why is my HDR efficiency low, and how can I improve it?

Answer: Low HDR efficiency is a common challenge due to the innate competition from the more dominant NHEJ pathway. Several strategies can be employed to tilt this balance in favor of HDR.

Table 2: Strategies to Improve HDR Efficiency

| Strategy | Method | Brief Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibit NHEJ | Use chemical inhibitors (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2) or siRNA against key NHEJ proteins [4]. | Reduces competition from the error-prone NHEJ pathway, allowing more DSBs to be repaired via HDR [1]. |

| Synchronize Cell Cycle | Synchronize cells to S/G2 phase using chemical blockers [1] [5]. | HDR is active only in S and G2 phases; enriching for cells in these phases increases the likelihood of HDR. |

| Optimize Donor Template | Use single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) for small edits; ensure long homology arms (350-700 nt) for larger insertions [5]. | ssDNA templates reduce toxicity and random integration. Longer homology arms exponentially improve knock-in efficiency [1] [5]. |

| Modify Target Site | Incorporate silent mutations in the PAM or seed sequence of the donor template [5]. | Prevents re-cleavage of the successfully edited locus by Cas9, allowing HDR-edited cells to persist. |

I am observing complex or imprecise editing outcomes even with HDR. Why?

Answer: Even when using an HDR donor template, you may observe imprecise integration. This can be due to the activity of alternative repair pathways beyond classical NHEJ and HDR.

- Alternative Repair Pathways: Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) and Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) are two other DSB repair pathways that can interfere with perfect HDR. MMEJ relies on short microhomologous sequences (2-20 nt) and often results in deletions, while SSA uses longer homologous sequences and can lead to significant deletions and imprecise donor integration [4].

- Mixed-Type Repair (MTR): Recent studies have documented cases where a single DSB is repaired simultaneously by NHEJ on one side and HDR on the other, leading to chimeric outcomes [6].

- Solution: To suppress these alternative pathways, consider inhibiting key effector proteins. For example, suppressing POLQ (for MMEJ) or Rad52 (for SSA) has been shown to reduce nucleotide deletions around the cut site and improve the accuracy of knock-in [4].

How can I verify INDELs formed by NHEJ?

Answer: Accurately verifying and quantifying indels is critical for analyzing gene knockout experiments.

- Sanger Sequencing & Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): The most direct method is to amplify the target region by PCR and subject the product to sequencing. Sanger sequencing is suitable for initial validation, while NGS (e.g., Illumina MiSeq) provides a comprehensive, quantitative profile of all indel variants in a mixed population.

- Troubleshooting Sequencing Data: When analyzing Sanger sequencing chromatograms from cloned PCR products, a "double sequence" (overlapping peaks) starting from the DSB site often indicates a mixed population of alleles with different indels. This requires sub-cloning and sequencing individual colonies to resolve the specific sequences of each allele [7].

- Importance of Model: Note that traditional alignment algorithms assuming a geometric model of indel lengths can introduce artifacts. Using power-law models (e.g., zeta distribution) provides a more accurate estimation of indel rates and patterns from sequencing data [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Repair Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Generates a site-specific double-strand break (DSB) in the genome, initiating the DNA repair process [1]. |

| Single-Guide RNA (sgRNA) | Directs the Cas9 nuclease to the specific genomic target sequence [1]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2) | Chemical compounds used to suppress the NHEJ pathway, thereby increasing the relative frequency of HDR [4]. |

| HDR Donor Template (ssODN or dsDNA) | Provides the homologous DNA sequence containing the desired edit (flanked by homology arms) for the HDR pathway to use as a repair template [5]. |

| MMEJ/SSA Inhibitors (e.g., ART558 (POLQi), D-I03 (Rad52i)) | Chemical inhibitors targeting key enzymes of alternative repair pathways (MMEJ and SSA) to reduce imprecise repair and improve HDR accuracy [4]. |

| Cell Cycle Synchronization Agents (e.g., Aphidicolin, Nocodazole) | Chemicals used to arrest cells at specific phases (e.g., S/G2) to enhance HDR efficiency [1]. |

While small insertions and deletions (indels) have long been a focus of genetic research, large structural variations (SVs) represent a category of genomic alterations with potentially greater impact on human health and disease. Structural variants are generally defined as genomic rearrangements involving 50 base pairs to several million base pairs of DNA, encompassing deletions, duplications, insertions, inversions, translocations, and copy number variants (CNVs) [9] [10] [11]. These substantial alterations account for more human genetic variation by base count than single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), with approximately 13% of the human genome identified as structurally variant in the normal population [10]. This technical support article explores the detection, interpretation, and analytical challenges of SVs within the broader context of indel mutation research.

FAQs: Understanding Structural Variations

1. What exactly qualifies as a structural variation, and how does it differ from small indels?

Structural variations are genomic alterations typically involving at least 50 base pairs, though many span kilobases to megabases of DNA [9] [10]. This distinguishes them from small indels, which are usually under 50bp. SVs encompass a diverse range of events including:

- Copy Number Variants (CNVs): Deletions and duplications that create genomic imbalances

- Balanced rearrangements: Inversions and translocations that don't alter copy number

- Insertions: Novel sequence additions, including mobile element insertions

- Complex variations: Combinations of the above in a single event [12] [10]

2. Why are structural variations more challenging to detect than small indels?

SV detection presents multiple technical challenges:

- Size limitations: SVs often exceed typical sequencing read lengths

- Complex patterns: Different SV types can produce similar mapping patterns

- Repetitive regions: Breakpoints frequently occur in segmental duplications and repetitive elements

- Overlapping events: Multiple SVs can be nested or overlap, creating complex patterns [13] Short-read sequencing technologies typically achieve only 30-70% sensitivity for SV detection with false discovery rates as high as 85% [14].

3. What methodologies provide the most accurate SV detection?

No single method optimally detects all SV types, but integrated approaches yield the best results:

- Long-read sequencing (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore): Enables detection of SVs >1kb with much higher sensitivity

- Multi-method computational approaches: Combining read-pair, split-read, read-depth, and assembly-based methods

- Orthogonal validation: Using array CGH, FISH, or PCR to confirm computational predictions [13] [14] [15] Recent benchmarking shows that assembly-based methods like SVIM-asm provide superior accuracy and resource consumption for comprehensive SV detection [15].

4. How do structural variations contribute to disease compared to small indels?

SVs can disrupt genetic function through multiple mechanisms:

- Gene dosage effects: Changing copy number of dosage-sensitive genes

- Gene disruption: Directly breaking gene coding sequences

- Gene fusions: Creating novel chimeric genes

- Regulatory alterations: Disrupting topologically associating domains (TADs) and repositioning regulatory elements [9] SVs account for a significant proportion of genomic disorders, including Smith-Magenis syndrome (17p11.2 deletion), Potocki-Lupski syndrome (17p11.2 duplication), and numerous cancer-associated rearrangements [12] [9].

5. What resources are available for interpreting the clinical significance of SVs?

Multiple databases and tools support SV interpretation:

- Population databases: Database of Genomic Variants (DGV), gnomAD-SV

- Clinical databases: ClinVar, DECIPHER, dbVar

- Prioritization tools: AnnotSV, ClassifyCNV, CADD-SV [16] Professional guidelines from ACMG/ClinGen provide standardized frameworks for clinical interpretation, distinguishing pathogenic SVs from benign polymorphisms [9] [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common SV Detection Issues and Solutions

Problem: High false positive rates in SV calling

- Potential causes: Mapping errors in repetitive regions; PCR artifacts; low sequencing quality

- Solutions:

Problem: Inability to resolve exact breakpoints

- Potential causes: Breakpoints in repetitive elements; complex rearrangements; low coverage

- Solutions:

Problem: Difficulty detecting balanced rearrangements

- Potential causes: Standard approaches focus on copy-number changes; breakpoints in inaccessible regions

- Solutions:

SV Validation Workflow

Structural Variation Detection Methods

Comparative Performance of SV Detection Technologies

Table 1: Performance characteristics of major SV detection approaches

| Method Category | Key Tools | Optimal SV Types Detected | Limitations | Accuracy Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-read WGS | DELLY, LUMPY, Manta | Deletions, small insertions, CNVs | Misses large/complex SVs, repetitive regions | Sensitivity: 30-70%, FDR up to 85% [14] |

| Long-read WGS | Sniffles, SVIM, cuteSV | All SV types, complex rearrangements | Higher cost, computational demands | Greatly improved sensitivity for >1kb SVs [13] [15] |

| Read Depth | CNVnator, XHMM | Large CNVs | Misses balanced rearrangements | Strong for large CNVs, weak for precise breakpoints [17] |

| Split Read | Pindel, SVseq2 | Precise breakpoints for indels | Limited to read-length SVs | Excellent for small-medium SVs with precise breakpoints [17] |

| Assembly-based | SVIM-asm, Canu | Novel insertions, complex SVs | Computationally intensive, requires high coverage | Superior accuracy, resolves full SV complexity [13] [15] |

SV Prioritization Tools for Functional Interpretation

Table 2: Computational tools for prioritizing clinically relevant SVs

| Tool Name | Classification Approach | Key Features | Input Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| AnnotSV | Knowledge-driven (ACMG) | Implements ACMG guidelines, comprehensive annotation | VCF file, gene annotations [16] |

| ClassifyCNV | Knowledge-driven (ACMG) | ACMG guidelines for CNVs, user-friendly | VCF file, gene annotations [16] |

| CADD-SV | Data-driven (machine learning) | Evolutionary constraint scores, random forest model | VCF file, pre-computed scores [16] |

| StrVCTVRE | Data-driven (machine learning) | Focus on exonic impacts, random forest | VCF file, exon annotations [16] |

| TADA | Data-driven (machine learning) | Incorporates 3D genomic interactions | VCF file, Hi-C data (optional) [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Comprehensive SV Detection Using Hybrid Sequencing

Objective: Identify and validate structural variations using complementary sequencing technologies.

Materials:

- High-molecular-weight DNA (>50kb)

- Short-read sequencer (Illumina NovaSeq, etc.)

- Long-read sequencer (PacBio Sequel II/Revio, Oxford Nanopore)

- Computational resources (high-memory server, >32 cores, >100GB RAM)

Procedure:

- Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Prepare both short-read (350bp insert) and long-read (15kb+ insert) libraries

- Sequence to minimum coverage: 30x short-read, 15x long-read

- Ensure high DNA quality (QV>30 for short reads, >Q20 for long reads)

Multi-method Computational Analysis

- Process short-read data with 2-3 complementary callers (DELLY, Manta, LUMPY)

- Process long-read data with specialized tools (Sniffles, SVIM)

- Perform de novo assembly for complex regions (Canu, Flye)

- Generate consensus callset requiring support from multiple methods

Variant Filtering and Prioritization

- Remove SVs with population frequency >1% in control databases (gnomAD-SV, DGV)

- Annotate with gene overlaps, regulatory elements, and constraint scores

- Prioritize rare, genic SVs with high quality scores

Experimental Validation

- Design PCR assays across breakpoints for 10-20% of predicted SVs

- Perform orthogonal validation using array CGH or FISH for large events

- Confirm functional impact using RNA-seq for gene fusions and expression outliers

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For low validation rates, increase stringency of quality filters

- For missing known SVs, adjust mapping parameters and try alternative aligners

- For complex regions, target with ultra-long reads (>50kb) or optical mapping [13] [14] [15]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents and resources for structural variation research

| Reagent/Resource | Supplier/Platform | Application in SV Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi Reads | Pacific Biosciences | High-accuracy long-read SV discovery | 15-20kb reads, Q30+ accuracy, ideal for complex regions [18] |

| Oxford Nanopore Ultra-long Reads | Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Spanning massive SVs, complex regions | Reads up to 1Mb+, lower per-base accuracy [14] |

| 10x Genomics Linked Reads | 10x Genomics | Phasing, structural variant haplotyping | Maintains long-range information with short reads [13] |

| Bionano Optical Maps | Bionano Genomics | De novo mapping, large SV validation | Complementary to sequencing-based approaches [14] |

| Cytogenetic Arrays | Affymetrix, Illumina | Genome-wide CNV detection, clinical screening | Established clinical utility, limited resolution [14] |

| FISH Probes | Multiple suppliers | Validation, visualization of SVs | Low-throughput but provides direct visual evidence [14] |

| SV Analysis Tools | Public repositories | Computational SV detection | Use complementary approaches to maximize sensitivity [16] [17] |

Advanced Detection Workflow

Structural variations represent a formidable challenge in genomic medicine, surpassing small indels in both scale and complexity. Successful SV analysis requires integrated approaches combining complementary technologies, rigorous computational filtering, and orthogonal validation. As detection methods continue advancing—particularly with long-read sequencing technologies—our ability to uncover the full spectrum of structural variations will dramatically improve, enabling more comprehensive assessment of their clinical implications in genetic disorders, cancer, and drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between an on-target and an off-target indel?

An on-target indel is an insertion or deletion of nucleotides that occurs at the precise genomic location where the engineered nuclease (such as CRISPR-Cas9) was designed to create a double-strand break (DSB). These are the intended, desired outcomes of a genome editing experiment, often used to knock out a gene's function [19].

An off-target indel is an unintended insertion or deletion that occurs at a different, often genetically similar, genomic site due to non-specific cleavage by the nuclease. These events pose a significant risk as they can disrupt the function of non-targeted genes, potentially leading to confounding experimental results or genotoxic effects in therapeutic contexts [20].

FAQ 2: What are the primary cellular mechanisms that lead to the formation of indels?

Indels are primarily formed when a cell repairs a DSB through error-prone DNA repair pathways [19]:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This is the dominant pathway and directly ligates the broken DNA ends. Because it is error-prone, it often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site [21].

- Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ): This pathway uses short homologous sequences (microhomologies) flanking the break to repair the DNA. The repair process deletes one copy of the microhomology and the intervening sequence, leading to typically larger, more predictable deletions [22] [21].

FAQ 3: Beyond small indels, what larger unintended edits should I be concerned about?

While small indels are common, CRISPR-Cas9 editing can also induce larger, more complex structural variants (SVs), which are defined as insertions or deletions ≥50 bp. These can occur at both on-target and off-target sites and may include large deletions, inversions, and complex rearrangements [23]. One study found that SVs represented 6% of editing outcomes in zebrafish models, and these mutations were passed on to subsequent generations, highlighting their potential stability and impact [23]. Standard short-read sequencing methods often fail to detect these events, requiring long-read sequencing technologies for comprehensive identification [23].

FAQ 4: What are the best methods to detect and quantify on-target editing efficiency?

The choice of method depends on the required sensitivity and the level of detail needed about the mutation spectrum. Table: Common Methods for Detecting and Quantifying Indels

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) / CEL-I Assay [19] | Detects heteroduplex DNA formed by wild-type and indel-containing strands. | ~1-2% | Rapid, economical, gel-based. | Does not reveal the sequence of the indel. |

| Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) [19] | Loss or gain of a restriction site due to editing. | ~1-2% | Quantitative for specific changes. | Requires introduction of a specific sequence change. |

| Sanger Sequencing [19] | Direct sequencing of PCR amplicons. | ~10-15% | Provides exact sequence changes. | Lower sensitivity; requires decomposition software for complex mixtures. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [19] [21] | High-throughput sequencing of PCR amplicons or the whole genome. | ~0.01% | Highly sensitive, provides full mutation spectrum, detects complex variants. | More expensive and complex data analysis. |

FAQ 5: How can I comprehensively identify off-target sites in my experiment?

A combination of in silico prediction and experimental validation is recommended for a thorough analysis. Table: Methods for Off-Target Site Identification

| Method Type | Method Name | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Silico Prediction [24] | Cas-OFFinder, CasOT | Computational tools that scan a reference genome for sequences with high similarity to the gRNA sequence, allowing for mismatches and bulges. | Fast and inexpensive, but can miss sites; results require experimental validation. |

| Cell-Free Experimental [24] | CIRCLE-seq, Digenome-seq | Uses purified genomic DNA (or cell-free chromatin) digested with Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), followed by sequencing to identify cleavage sites. | Highly sensitive and unbiased by cellular context. |

| Cell-Based Experimental [24] | GUIDE-seq, S-EPTS/LM-PCR | Uses tag molecules (e.g., double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides) that are integrated into DSBs in living cells, allowing for amplification and sequencing of off-target sites. | Captures off-target effects in a more biologically relevant cellular environment. |

FAQ 6: What strategies can I employ to minimize off-target indels?

Several well-established strategies can enhance the specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 editing:

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Engineered Cas9 nucleases (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) have mutations that reduce tolerance for gRNA-DNA mismatches [24].

- Utilize Cas9 Nickases: Delivering two gRNAs with a "nickase" mutant of Cas9 (which cuts only one DNA strand) requires two closely spaced, opposite-strand nicks to create a DSB, dramatically increasing specificity [20].

- Employ Dimeric Nucleases: Systems like FokI-dCas9 fuse the FokI nuclease domain to a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9). FokI requires dimerization to cut, meaning two independent gRNAs must bind in close proximity and correct orientation for cleavage to occur, reducing off-target effects by up to 10,000-fold [20].

- Optimize gRNA Design: Truncating the gRNA to 17-18 nucleotides can increase specificity. Also, select gRNAs with minimal potential for off-target binding using prediction software [24] [20].

- Control Delivery and Dosage: Using RNP complexes instead of plasmid DNA can reduce the duration of Cas9 activity, and using the minimum effective concentration of the nuclease can help limit off-target effects [24] [23].

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Assessing On-Target Editing Efficiency using T7E1 Assay

This protocol provides a rapid, gel-based method to estimate nuclease activity [19].

- Extract Genomic DNA: Isolate genomic DNA from edited cells and a control (un-edited) population.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers to amplify a 300-500 bp region surrounding the target site. Perform PCR on both test and control DNA.

- Heteroduplex Formation: Denature and reanneal the PCR products by heating to 95°C and then slowly cooling to room temperature. This allows strands from edited and un-edited alleles to hybridize, forming heteroduplexes at mismatched indel sites.

- Digestion with T7E1: Treat the reannealed PCR product with T7 Endonuclease I, which cleaves at heteroduplex DNA sites.

- Analysis by Gel Electrophoresis: Run the digested products on an agarose gel. Cleaved fragments indicate the presence of indels. The editing efficiency can be estimated by comparing the band intensities of cleaved and uncleaved products.

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Off-Target Analysis using GUIDE-seq

This protocol outlines a sensitive, cell-based method for genome-wide identification of off-target sites [24].

- Transfection: Co-transfect your cells with the Cas9/sgRNA expression constructs (or RNP complexes) and the GUIDE-seq double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 2-3 days post-transfection and extract genomic DNA.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Shear the genomic DNA and prepare a sequencing library. The dsODN tag is used as a primer binding site to selectively amplify and sequence genomic regions that have incorporated the tag—these represent DSB locations.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map the sequenced reads to the reference genome. Clusters of reads with the tag sequence inserted identify potential off-target cleavage sites. These sites should be validated by targeted amplicon sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Indel Analysis in Genome Editing

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 [24] | Engineered nuclease with reduced off-target activity. | Essential for all therapeutic applications and sensitive experiments where specificity is critical. |

| Cas9 Nickase [20] | A Cas9 variant that cuts only one DNA strand. | Used in pairs with two guide RNAs to create a DSB, significantly increasing targeting specificity. |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) [19] | Enzyme that cleaves mismatched DNA in heteroduplexes. | Quick and cost-effective initial screening for nuclease activity and on-target efficiency. |

| GUIDE-seq dsODN Tag [24] | A short, double-stranded DNA oligo that integrates into DSBs. | A critical reagent for the GUIDE-seq protocol to experimentally identify genome-wide off-target sites. |

| Long-Range PCR Kit | For amplifying large genomic regions (several kb). | Required to generate amplicons for detecting large structural variants via long-read sequencing [23]. |

| In Silico Prediction Tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder) [24] | Software to computationally nominate potential off-target sites. | The first step in off-target assessment; used to prioritize sites for experimental validation. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Cellular Pathways for Indel Formation after a DSB. This diagram illustrates the two main competing DNA repair pathways that lead to different types of indel mutations after a nuclease-induced double-strand break (DSB). The classical Non-Homologous End Joining (c-NHEJ) pathway typically results in small insertions or deletions, while the Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) pathway results in larger deletions that utilize flanking microhomology regions [21].

Diagram 2: Workflow for Comprehensive Off-Target Assessment. This workflow outlines a multi-step strategy for a thorough analysis of unintended editing events, moving from computational prediction to experimental validation and finally to the detection of complex structural variants [22] [24] [23].

Prime editing is a precise genome editing technology that enables targeted insertions, deletions, and all possible base-to-base conversions without requiring double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) or donor DNA templates [25] [26]. Despite its precision, a significant challenge remains: the formation of insertion and deletion (indel) byproducts. These unintended mutations often originate from the inefficient displacement of the competing 5' DNA strand by the newly edited 3' strand, creating a barrier to installing clean edits [27]. This technical guide examines the mechanistic basis of this challenge and provides evidence-based troubleshooting strategies to minimize indel formation in prime editing experiments.

FAQs: Understanding the Competing Strand Challenge

Indel byproducts in prime editing arise from several mechanisms [27]:

- Inefficient strand displacement: The edited 3' new strand is often disfavored in displacing the original 5' strand due to being mismatched to the complementary strand.

- Extended reverse transcription: The prime editor may extend the edited 3' new strand past the pegRNA template into the scaffold region.

- Errant double-strand breaks: These can be generated when cellular mismatch repair (MMR) converts nicks into DSBs, leading to indel formation through error-prone repair pathways.

- End joining at unintended positions: The edited 3' new strand can join at incorrect locations, producing large deletions or tandem duplication-like insertions.

How does the competing strand displacement problem limit prime editing efficiency?

The competing strand displacement problem creates a fundamental limitation in prime editing efficiency through several interconnected mechanisms [27]:

- The natural bias of cellular systems toward retaining the original 5' strands hinders the installation of edits written into the 3' new strands.

- This bias not only reduces editing efficiency but actively promotes error formation by creating intermediates that cellular repair pathways may process incorrectly.

- The heteroduplex DNA structure formed (with one edited and one unedited strand) can be recognized and processed by MMR systems in ways that often favor the original sequence or introduce indels.

What recent breakthroughs have addressed the competing strand challenge?

Recent research has identified that relaxing nick positioning through specific Cas9-nickase mutations can promote degradation of the competing 5' strand, thereby enhancing editing efficiency and reducing indel errors [27]. Engineered prime editors with mutations such as K848A and H982A demonstrated dramatically reduced indel errors - up to 118-fold lower than early prime editors - by destabilizing the non-target strand nicked 5' end. The resulting "precise prime editor" (pPE) and next-generation editor (vPE) achieve edit:indel ratios as high as 543:1, representing a substantial improvement over previous systems.

Troubleshooting Guide: Minimizing Indel Formation

Problem: High Indel Rates with Standard Prime Editors

Issue: Unacceptable levels of insertion/deletion byproducts are observed when using PE2 or PE3 systems.

Solution: Implement engineered prime editor architectures with reduced strand displacement bias [27].

Protocol:

- Utilize nick-relaxing Cas9 variants: Replace standard Cas9 nickase with variants containing mutations that promote 5' strand degradation (R780A, K810A, K848A, K855A, R976A, or H982A).

- Employ optimized editor architectures: Use pPE (K848A-H982A) or vPE systems that combine error-suppressing strategies with efficiency-boosting architectures.

- Validate with appropriate controls: Test editors across multiple genomic loci to confirm consistent performance.

Expected Outcomes: pPE reduces indels 7.6-fold for pegRNA-only editing and 26-fold for pegRNA+ngRNA editing compared to PEmax, with similar editing efficiency [27].

Problem: MMR-Mediated Reversion of Edits

Issue: Cellular mismatch repair systems reverse prime edits, reducing efficiency.

Solution: Transiently inhibit MMR during prime editing [25] [28].

Protocol:

- Employ PE4/PE5 systems: Co-express a dominant-negative version of MLH1 (MLH1dn) to temporarily suppress MMR.

- Consider newer approaches: Implement AI-generated MLH1 small binders (MLH1-SB) that can be integrated directly into PE architectures via 2A systems [28].

- Limit inhibition duration: Use transient expression systems to avoid long-term MMR suppression.

Expected Outcomes: PE4 improves editing efficiency by 7.7-fold versus PE2, while PE7-SB2 achieves an 18.8-fold increase over PEmax in HeLa cells [25] [28].

Problem: PegRNA Degradation and Instability

Issue: Extended pegRNAs are prone to degradation, reducing editing efficiency.

Solution: Implement engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) with stabilized architectures [25] [29].

Protocol:

- Incorporate RNA stability motifs: Append structured RNA elements (evopreQ1, mpknot, or Zika virus exoribonuclease-resistant RNA motif) to the 3' end of pegRNAs.

- Explore alternative stabilization: Consider the PE7 system, which fuses the La protein to stabilize pegRNA 3' tails [30].

- Validate pegRNA integrity: Use quality control measures to ensure full-length pegRNA synthesis.

Expected Outcomes: epegRNAs improve prime editing efficiency 3-4-fold across multiple human cell lines and primary human fibroblasts [29].

Quantitative Comparison of Prime Editing Systems

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of different prime editing systems for minimizing indel byproducts:

| Editing System | Key Features | Edit:Indel Ratio | Indel Reduction vs. PEmax | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE3 [25] | Additional nicking sgRNA | Variable (often <30:1) | - | When maximum efficiency is needed and some indels are acceptable |

| PE4/PE5 [25] | MLH1dn expression to inhibit MMR | Improved over PE3 | Moderate | When indels must be minimized and nicking sgRNAs cannot be used |

| pPE [27] | K848A-H982A mutations to relax nick positioning | Up to 361:1 | 7.6-26× reduction | General purpose editing with minimal indels |

| vPE [27] | Combines error-suppression with efficiency boosting | Up to 543:1 | Up to 60× reduction | Applications requiring highest fidelity and efficiency |

| PE7-SB2 [28] | AI-generated MLH1 small binder integrated via 2A | Not specified | Not specified (18.8× efficiency gain over PEmax) | Challenging edits where efficiency is limiting |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Nick-Relaxing Prime Editors

This protocol outlines how to test and validate prime editors with reduced strand displacement bias, based on methodologies from recent literature [27].

Materials Needed

- Prime Editor Plasmids: PE (control), pPE (K848A-H982A), and other variants with nick-relaxing mutations

- Cell Line: HEK293T or other relevant cell types

- Targeting Components: pegRNAs and nicking gRNAs for loci of interest (e.g., TGFB1, KRAS, CXCR4, EMX1)

- Analysis Method: Next-generation sequencing for quantitative assessment of editing outcomes

Procedure

Design pegRNAs with appropriate architecture:

- Include RTT (10-30 nt) encoding desired edit

- Incorporate PBS (10-15 nt) complementary to target site

- Consider epegRNA designs with 3' stability motifs

Cell transfection and editing:

- Co-deliver prime editor plasmids and pegRNAs/ngRNAs

- Include controls with PEmax for comparison

- Use appropriate delivery method (lipofection, electroporation) for cell type

Harvest and analyze outcomes:

- Extract genomic DNA 72-96 hours post-transfection

- Amplify target regions by PCR

- Perform deep sequencing (≥10,000x coverage)

- Quantify: desired edit efficiency, indels with and without edits, edit:indel ratios

Data Interpretation

Calculate key metrics for each editor variant:

- Editing efficiency: (% reads with desired edit)

- Indel frequency: (% reads with indels)

- Edit:indel ratio: (Editing efficiency ÷ Indel frequency)

- Flap degradation: (Ratio of activity marker edit to flap homology deletion)

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential reagents for addressing the competing strand challenge in prime editing:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered Editors | pPE, vPE [27] | Reduce strand displacement bias through nick relaxation | Test multiple variants as performance varies by locus |

| MMR Inhibitors | MLH1dn, MLH1-SB [25] [28] | Temporarily suppress mismatch repair to prevent edit reversion | Transient expression recommended to avoid genomic instability |

| Stabilized Guides | epegRNAs [29] | Protect 3' extensions from degradation | Different motifs (evopreQ1, mpknot) may perform variably |

| Delivery Systems | LNPs, AAV vectors [26] [29] | Enable efficient editor delivery | Size constraints critical for AAV; consider split systems |

Mechanism and Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the core challenge and solution strategy for competing strand displacement in prime editing.

The competing strand displacement challenge represents a fundamental limitation in prime editing technology, directly contributing to unwanted indel byproducts. Through strategic engineering of the Cas9 nickase to relax nick positioning and promote degradation of the non-target 5' strand, researchers can dramatically reduce indel frequencies while maintaining high editing efficiency. Implementation of optimized editor architectures like pPE and vPE, combined with MMR suppression and pegRNA stabilization, provides a comprehensive toolkit for achieving clean, precise genomic modifications with minimal unintended mutations. As prime editing continues evolving toward therapeutic applications, addressing this core mechanistic challenge remains essential for realizing the full potential of precise genome editing.

In the context of therapeutic genome editing, Insertions and Deletions (Indels) are small, unintended genetic modifications that typically occur at the site of a CRISPR-Cas-induced double-strand break (DSB) when the cell repairs the damage via the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway [31]. While intentionally leveraged for gene disruption, their unplanned generation poses a significant challenge, influencing both the safety and efficacy of treatments. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and foundational knowledge for researchers and drug development professionals navigating these complexities.

► FAQ: Indels in Editing Research

What are the primary safety concerns associated with indel formation in therapeutic contexts? The primary safety concerns extend beyond simple gene knockout. While small indels at the on-target site can disrupt the intended gene function, a more pressing risk involves larger, unforeseen genomic alterations. Recent studies reveal that CRISPR/Cas editing can induce large structural variations (SVs), including kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations, particularly when DNA-PKcs inhibitors are used to enhance Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [32]. These alterations can delete critical cis-regulatory elements or affect tumor suppressor genes and proto-oncogenes, raising substantial oncogenic concerns [32].

How can I accurately detect and quantify indel frequencies in my experiments? Accurate detection is method-dependent. Traditional short-read amplicon sequencing can miss large deletions that span primer-binding sites, leading to an overestimation of precise editing rates [32]. For a comprehensive analysis, a combination of methods is recommended:

- Enzymatic Mismatch Cleavage Assays: Using enzymes like T7 Endonuclease I or Authenticase provides a simple and sensitive method to estimate editing efficiency by cleaving heteroduplex DNA formed by re-annealing edited and unedited PCR products [33].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Targeted amplicon sequencing (e.g., using NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kits) allows for accurate genotyping and quantification of indel frequencies. For genome-wide analyses, PCR-free NGS library preparation (e.g., NEBNext Ultra II DNA PCR-free Library Prep) is recommended to avoid PCR bias and provide a higher quality assessment of editing outcomes, including larger structural variations [33] [32].

Why might my gene augmentation therapy be ineffective for a specific inherited retinal disease? The efficacy of gene augmentation therapy is highly dependent on the nature of the underlying genetic mutation. This approach, which involves delivering a functional copy of a gene using viral vectors like AAV, is highly suitable for recessive disorders caused by loss-of-function (LOF) mutations, as demonstrated by Luxturna for RPE65-associated retinal dystrophy [34]. However, it is largely ineffective for dominant-negative or gain-of-function mutations. In these cases, the newly introduced functional gene cannot overcome the toxic effects of the mutant protein already being produced. For dominant conditions, alternative strategies such as allele-specific silencing or gene editing to inactivate the mutant allele are required [34].

What delivery challenges are specific to CRISPR therapies that aim to minimize indels? The main challenge is the limited packaging capacity of the most common delivery vector, adeno-associated virus (rAAV). While base editors and prime editors offer a route to precise editing without DSBs (and thus without indel formation), their larger size makes packaging into a single rAAV vector difficult [31]. Strategies to overcome this include:

- Using hypercompact Cas orthologs (e.g., CasMINI, IscB, TnpB) or engineered effectors like SaCas9.

- Employing dual-rAAV vector systems to deliver the editing machinery in separate parts [31].

- Exploring non-viral delivery systems, such as Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), which offer higher cargo capacity and the potential for re-dosing, unlike rAAVs [34] [35] [36].

► Troubleshooting Guide: Managing Indel-Related Issues

Problem 1: Inaccurate Quantification of HDR and Indel Rates

Symptoms: Reported HDR efficiency is high, but functional recovery of the protein is low. Sanger or short-read amplicon sequencing data shows a high proportion of "noisy" or uninterpretable sequences.

Root Cause: The use of HDR-enhancing small molecules, such as DNA-PKcs inhibitors, can aggravate genomic aberrations, leading to large-scale deletions that remove the primer-binding sites used in PCR [32]. Since these large deletions are not amplified, they remain undetected, artificially inflating the apparent HDR rate and underestimating the true frequency of indels and other deleterious outcomes [32].

Solution:

- Employ Long-Range PCR: Design primers that bind several kilobases upstream and downstream of the target site to amplify larger fragments.

- Utilize Structural Variation Detection Methods: Apply techniques like CAST-Seq or LAM-HTGTS, which are specifically designed to detect large deletions, translocations, and other SVs [32].

- Validate with PCR-Free NGS: For a comprehensive view, use PCR-free whole-genome sequencing to avoid amplification bias and reveal the full spectrum of on- and off-target edits [33] [32].

Problem 2: High Off-Target Indel Activity

Symptoms: Editing is observed at genomic loci with sequence similarity to the intended target guide RNA, even after careful in silico design.

Root Cause: The CRISPR/Cas9 complex can tolerate some mismatches between the guide RNA and the DNA, leading to cleavage at off-target sites and resulting in unwanted indels [32].

Solution:

- Use High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Switch to engineered Cas9 variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9) with enhanced specificity [32].

- Optimize gRNA Design: Select guides with minimal off-target potential using advanced design tools that account for genomic context.

- Consider Alternative Editors: For point mutations, use base editors or prime editors, which have a lower propensity for generating indels at off-target sites compared to nucleases that create DSBs [31].

- Thoroughly Profile Off-Targets: Perform genome-wide off-target analyses (e.g., using CIRCLE-seq or GUIDE-seq) in relevant cell types to empirically determine the risk profile [32].

Problem 3: Low Efficiency of Precisely Edited Clones

Symptoms: After editing with an HDR-based strategy, the proportion of cells with the desired precise edit is low, and the majority of modified cells contain indels.

Root Cause: The NHEJ pathway is more active and efficient in most mammalian cells than the HDR pathway, which is restricted to certain cell cycle phases.

Solution:

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: Synchronize cells in the S/G2 phases where HDR is more active [32].

- Evaluate HDR Enhancers Cautiously: While inhibitors of NHEJ factors like 53BP1 can enhance HDR, avoid DNA-PKcs inhibitors which have been shown to cause severe genomic aberrations [32].

- Consider Enrichment Strategies: For ex vivo editing, implement post-editing selection methods (e.g., FACS or antibiotic selection) to enrich for successfully HDR-edited cells [32].

- Re-evaluate Therapeutic Need: For some diseases, a knockout of the mutant gene via NHEJ may be therapeutic. In dominant disorders, inducing indels that disrupt the mutant allele can be a valid strategy [34].

► Experimental Protocols for Indel Validation

Protocol 1: Enzymatic Detection of Indel Frequencies

This protocol uses the EnGen Mutation Detection Kit or Authenticase for a quick, cost-effective estimation of editing efficiency [33].

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Genomic DNA Isolation: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from edited and control cell populations.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target genomic region from both samples using high-fidelity DNA polymerase. Ensure amplicon size is appropriate for gel resolution (200-1000 bp).

- Heteroduplex Formation: Denature the PCR products at 95°C for 10 minutes, then slowly re-anneal by ramping down to 25°C over 45 minutes. This allows strands with and without indels to hybridize, forming heteroduplexes with bulges at the mismatch sites.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Treat the re-annealed DNA with a mismatch-sensitive nuclease (e.g., T7 Endonuclease I or Authenticase) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Analysis: Separate the digestion products by agarose gel electrophoresis. Cleaved bands indicate the presence of indels. The editing efficiency can be estimated using the formula: Indel frequency (%) = 100 × (1 - √(1 - (b + c)/(a + b + c))), where

ais the integrated intensity of the undigested PCR product, andbandcare the intensities of the cleavage products [33].

Protocol 2: NGS-Based Indel Validation and Analysis

This protocol provides a quantitative and detailed profile of specific indel sequences using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina [33] [37].

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and Amplification: Isolate genomic DNA and perform a first-round PCR to amplify the target region(s) from around 100-200ng of DNA.

- Library Preparation: Use the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit to fragment the amplicons (if necessary), perform end-repair, dA-tailing, and ligate Illumina sequencing adapters. A second, limited-cycle PCR is used to index the libraries.

- Sequencing: Pool the indexed libraries at equimolar concentrations and sequence on an Illumina platform (e.g., MiSeq) to achieve high coverage (>1000x is ideal for detecting low-frequency events).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Read Alignment: Demultiplex the raw sequencing data and align reads to the reference genome using tools like BWA or Bowtie2.

- Variant Calling: Use specialized algorithms (e.g., CRISPResso2, VarDict) to identify and quantify insertions and deletions around the target site [37].

- Interpretation: Generate a summary report detailing the percentage of reads with indels, the spectrum of specific indel sequences, and their potential functional consequences (e.g., frameshift mutations).

► Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents for effective indel analysis in your experiments.

| Research Reagent | Primary Function in Indel Analysis | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Authenticase (NEB #M0689) | A mixture of structure-specific nucleases for enzymatic mismatch cleavage; detects a broad range of CRISPR-induced mutations [33]. | More sensitive than traditional T7 Endonuclease I for detecting heteroduplex mismatches [33]. |

| EnGen Mutation Detection Kit (NEB #E3321) | Provides optimized reagents for a conventional T7 Endonuclease I-based mutation detection assay [33]. | A standardized kit for a simple and rapid estimation of genome editing efficiency. |

| NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA PCR-free Library Prep Kit (NEB #E7430) | Enables preparation of whole-genome sequencing libraries from unsheared DNA without PCR amplification bias [33]. | Critical for unbiased detection of large structural variations and accurate genotyping, as it avoids the under-representation of large deletions [33] [32]. |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB #E7645) | Used for preparing high-quality, high-yield sequencing libraries from amplicons for targeted sequencing [33]. | Ideal for deep sequencing of specific on-target loci to characterize the spectrum and frequency of indels. |

| Cas9 Nuclease (S. pyogenes) | Can be used in an in vitro digestion assay to estimate editing efficiency by digesting unedited, perfectly matched sequences, but not most edited sequences [33]. | Most effective for assessing locus modification when the editing efficiency is above 50%. |

Advanced Editing Platforms and Workflows for Indel Suppression

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main sources of indel errors in prime editing, and how do next-generation editors address them? The main sources of indel errors in traditional prime editing include errant double-strand breaks (DSBs) and the improper integration of the edited 3' DNA strand. A key issue is the natural bias for the original, unedited 5' DNA strand to outcompete and displace the newly written, edited 3' strand. This competition can lead to large deletions, tandem duplications, or other unwanted insertions and deletions (indels) [27]. Next-generation editors like pPE and vPE address this by incorporating specific mutations (e.g., K848A and H982A) into the Cas9 nickase. These mutations relax the positioning of the DNA nick and promote the degradation of the competing 5' strand, making it easier for the edited 3' strand to be successfully incorporated into the genome, thereby drastically reducing indel formation [27] [38].

Q2: My prime editing experiment shows low efficiency. What strategies can I use to improve it? Low editing efficiency can be addressed through several strategies:

- Optimize Component Design: Ensure your pegRNA is well-designed and stable. Consider using engineered architectures that protect the unstable 3' ends of the pegRNA from degradation, a feature integral to the vPE system [27] [38].

- Leverage Advanced Editors: Utilize the latest editor variants. The vPE system was specifically designed to overcome the slight reduction in efficiency seen in earlier precise editors (like pPE and xPE) by boosting editing efficiency 3.2-fold compared to its predecessor [38].

- Inhibit Mismatch Repair (MMR): Co-delivering the prime editor with inhibitors of the cellular mismatch repair pathway can enhance the installation of the desired edit [27].

- Use a Nicking gRNA (ngRNA): Employing a pegRNA alongside a separate nicking gRNA can significantly increase editing efficiency, though this was also a major source of indels in older systems. The pPE and vPE editors show dramatic error suppression specifically in this "pegRNA + ngRNA" editing mode [27].

Q3: How can I accurately detect and quantify indel byproducts in my edited samples? Robust genotyping is essential. While sequencing is the gold standard, alternative methods are more scalable [39].

- High-Resolution Melt Analysis (HRMA): This is a post-PCR method that uses fluorescent dyes and precise temperature control to detect sequence variations, such as indels, based on their unique melt curves. It is sensitive, can be performed on 96-well plates, and allows for non-lethal genotyping using minimal tissue [40].

- Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE): Tools like ICE can use standard Sanger sequencing data to provide quantitative analysis of editing outcomes, including the calculation of indel percentage and the identification of specific edit types. This offers a cost-effective alternative to next-generation sequencing [41].

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) or Surveyor Nuclease Assay: These are enzyme-based methods that cleave mismatched DNA heteroduplexes (formed by annealing wild-type and mutant alleles) and can detect indels via gel electrophoresis [39] [40].

Q4: What are the primary limitations of prime editing technology? The primary limitation has been low efficiency due to its multi-step process, where each step must occur correctly for successful editing [42]. Delivery of the large editor construct into cells can also be challenging. While next-generation editors like vPE have made monumental progress in reducing indel errors, the technology is still relatively new and requires further optimization and validation across different cell types and organisms before widespread clinical application [27] [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Indel Error Rates in Prime Editing Experiments

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Use of a suboptimal prime editor system.

- Solution: Transition to next-generation prime editors. Replace first-generation systems (like PEmax) with the engineered pPE or vPE systems. These are specifically designed to suppress indel formation by destabilizing the competing 5' DNA strand [27].

- Cause: Inefficient installation of the edit allows for error-prone repair.

- Solution: Implement a multi-faceted strategy to boost efficiency. Use the vPE system, which combines error-suppressing mutations with a La protein to stabilize the pegRNA. Additionally, consider transiently inhibiting the cellular mismatch repair (MMR) pathway during editing to favor the desired outcome [27] [38].

- Cause: pegRNA degradation or suboptimal design.

- Solution: Redesign the pegRNA using specialized online tools. Ensure the template is encoded correctly and consider using modified architectures or chemical modifications to enhance the pegRNA's stability within the cellular environment [27].

Problem: Difficulty in Genotyping and Detecting Precise Edits

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The genotyping method lacks the sensitivity to detect a mix of edited and unedited sequences.

- Cause: Primers are designed too close to the edit site or in polymorphic regions.

- Solution: Redesign genotyping primers. Ensure they are positioned at least 20-50 bp away from the CRISPR target site. Use software like Primer3 for design, and perform a BLAST search to ensure specificity. Always sequence your wild-type amplicons to check for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that could interfere with analysis [40].

Quantitative Data on Editor Performance

The following tables summarize key performance metrics for next-generation prime editors compared to a previous standard, PEmax. The data is derived from testing in HEK293T cells across multiple genomic loci [27].

Table 1: Performance Comparison in pegRNA-only Editing Mode

| Editor | Average Indel Reduction (vs. PEmax) | Average Edit:Indel Ratio | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEmax | (Baseline) | ~57:1 | Standard efficiency-optimized editor |

| pPE | 7.6-fold | ~361:1 | Combines K848A and H982A mutations for precision |

| vPE | Comparable to PEmax | ~543:1 | Integrates error-suppression with pegRNA stabilization |

Table 2: Performance Comparison in pegRNA + Nicking gRNA (ngRNA) Mode

| Editor | Average Indel Reduction (vs. PEmax) | Average Edit:Indel Ratio | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEmax | (Baseline) | ~18:1 | High efficiency but with significant indels |

| pPE | 26-fold | ~361:1 | Dramatically reduces errors in dual-nick mode |

| vPE | Up to 60-fold | ~465:1 | Highest precision in the most efficient editing mode |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detecting Indels via High-Resolution Melt Analysis (HRMA) [40]

This protocol allows for rapid, non-lethal genotyping of mutant lines.

- gDNA Extraction:

- Anesthetize the organism (e.g., a mosquito) and remove a small tissue sample (e.g., a leg) using forceps.

- Place the tissue in a tube containing a DNA release additive and dilution buffer.

- Incubate at room temperature for 2-5 minutes, then at 98°C for 2 minutes.

- HRMA Primer Design:

- Target Selection: Choose an exon close to the start codon or a key functional domain. Avoid exon boundaries and regions with known SNPs.

- Design: Use software like Primer3. Set the amplicon size to 90-150 base pairs for optimal sensitivity. The primer binding sites should be ≥20-50 bp away from the CRISPR target site.

- Validation: Perform a BLAST search to ensure primer specificity. Validate primers with a gradient PCR and a thermal melt profile to confirm a single, clean product.

- PCR and HRMA:

- Prepare a PCR master mix with a fluorescent dsDNA-binding dye.

- Run the PCR with the extracted gDNA.

- Perform the high-resolution melt analysis immediately after PCR. The instrument should generate a melt curve by slowly increasing the temperature from 75°C to 95°C in small increments (e.g., 0.2°C).

- Analysis:

- Analyze the melt curves. Samples with different DNA sequences (e.g., wild-type vs. heterozygous or homozygous mutants) will produce distinct, normalized melt curves that can be used to determine the genotype.

Protocol 2: Analyzing CRISPR Edits using the ICE Tool [41]

This protocol uses Sanger sequencing and computational analysis to quantify edits.

- Sample Preparation:

- Extract genomic DNA from edited and control (wild-type) cells.

- Design PCR primers to amplify a region spanning the edit site.

- Purify the PCR product and send it for Sanger sequencing.

- ICE Analysis:

- Go to the ICE webtool.

- Upload the Sanger sequencing file (.ab1) for your edited sample and the control sample.

- Input the gRNA target sequence (excluding the PAM) and the donor sequence if performing a knock-in.

- Select the nuclease used (e.g., SpCas9) from the dropdown menu.

- Run the analysis.

- Interpretation:

- The tool will provide an Indel Percentage (the proportion of sequences with insertions or deletions).

- The Model Fit (R²) Score indicates the confidence in the results (closer to 1.0 is better).

- For knockouts, the Knockout Score estimates the percentage of sequences causing a frameshift.

- For knock-ins, the Knock-in Score shows the percentage with the precise insertion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Prime Editing Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Precision Prime Editors (pPE, xPE, vPE) | Engineered Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusions designed to minimize indel errors during editing. | The vPE system offers an optimal balance of high efficiency and very low indel errors [27] [38]. |

| Stable pegRNA Scaffolds | Modified guide RNA structures that resist cellular degradation, improving editing efficiency. | Can be combined with La protein or other RNA-stabilizing strategies, as seen in the vPE system [27]. |

| Mismatch Repair (MMR) Inhibitors | Chemical or protein-based inhibitors that temporarily suppress the MMR pathway to enhance prime editing outcomes. | Co-delivery can increase editing efficiency and reduce a specific class of errors [27]. |

| HDR Templates / Donor DNA | Single-stranded or double-stranded DNA molecules containing the desired edit, used as a template for the cellular repair machinery. | Required for knock-in experiments; should have homology arms complementary to the target site [43]. |

| Genotyping Tools (HRMA, ICE) | Kits and software for detecting and quantifying successful edits and byproducts like indels. | ICE tool provides NGS-quality data from cheaper Sanger sequencing [40] [41]. |

Experimental Workflow and Editor Mechanism

The diagram below illustrates the key steps and critical innovation of the next-generation prime editing system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental mechanism by which high-fidelity Cas9 variants reduce off-target effects?

High-fidelity Cas9 variants are engineered to minimize non-specific interactions with the DNA backbone. Wild-type SpCas9 possesses excess energy that allows it to cleave DNA even when the guide RNA does not perfectly match the target sequence. Variants like SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9(1.1) address this by introducing mutations that reduce these non-essential contacts, making the system more dependent on perfect guide RNA:DNA complementarity for efficient cleavage [44]. Essentially, they raise the energy threshold required for DNA cleavage, thereby preserving on-target activity while rejecting imperfectly matched off-target sites.

Q2: I am concerned about low on-target editing efficiency after switching to a high-fidelity variant. What could be the cause?

A reduction in on-target efficiency is a common trade-off with high-fidelity variants [45] [46]. This occurs because the mutations that decrease non-target DNA contacts can also slightly weaken the desired on-target binding. The degree of efficiency loss is highly guide-dependent [45]. The sequence context of your sgRNA, particularly in the seed region and positions 15–18 that interact with the Cas9's REC3 domain, significantly influences activity. If your sgRNA has suboptimal sequence features, the high-fidelity variant's mutations in the REC3 domain can lead to a more pronounced drop in efficiency [45].

Q3: Can I use high-fidelity Cas9 variants in base editing systems?

Yes, high-fidelity variants can be integrated into base editors to mitigate Cas9-dependent off-target editing. For example, replacing the wild-type SpCas9 in an adenosine base editor (ABE) with eSpCas9(1.1) to create e-ABE7.10 has been shown to dramatically reduce off-target editing while maintaining on-target activity at many sites [47]. However, the performance is site-dependent, and some high-fidelity variants may cause a substantial reduction in on-target base editing efficiency, so empirical testing is recommended [47].

Q4: Are there any newly developed Cas9 variants that overcome the efficiency-fidelity trade-off?

Recent research is focused on merging hyperactive mutations with high-fidelity mutations. One such engineered enzyme is HyperDriveCas9, which combines beneficial mutations from both high-fidelity and hyperactive Cas9 variants [46]. Initial reports indicate that HyperDriveCas9 can maintain the low off-target profile of high-fidelity parents while achieving higher on-target editing efficiency, offering a promising solution to this classic problem [46].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low On-Target Editing Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Inefficient sgRNA Sequence:

- Cause: The sgRNA sequence may have features that are particularly detrimental to the specific high-fidelity variant being used.

- Solution: Redesign the sgRNA. Utilize computational tools like GuideVar, which incorporates variant-specific sequence rules to predict and prioritize sgRNAs with higher expected on-target activity for variants like HiFi and LZ3 Cas9 [45]. Avoid sequences with high GC content or specific motifs in the PAM-distal region that are known to interact unfavorably with the mutated REC3 domain.

Inherent Trade-off of the Variant:

- Cause: The selected high-fidelity variant may have a significant inherent reduction in activity for your specific target site.

- Solution: Consider using a different high-fidelity variant. As shown in the table below, the performance of variants can vary. Alternatively, use the HyperDriveCas9 variant if maintaining high efficiency is critical [46]. You can also optimize delivery by ensuring high concentrations of the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

Problem: Persistent Off-Target Effects

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Suboptimal Variant Selection for the Target:

- Cause: While high-fidelity variants reduce off-targets, their efficacy can be sgRNA-dependent [45].

- Solution: Employ more sensitive off-target detection methods (e.g., GUIDE-seq [44]) to validate your results. For base editing applications, ensure you are using a high-fidelity variant like eSpCas9(1.1) or Sniper-Cas9 that has been validated to reduce Cas9-dependent off-target editing [47].

High sgRNA Dosage:

- Cause: Using very high levels of sgRNA can saturate the system and overwhelm the fidelity mechanisms of the Cas9 variant.

- Solution: Titrate the sgRNA concentration to the minimum required for efficient on-target editing. Using RNP complexes for delivery can help control stoichiometry and has been associated with reduced off-target effects.

Table 1: Comparison of High-Fidelity Cas9 Variant Performance

| Variant | Development Approach | Key Mutations | Reported On-Target Efficiency (vs. WT) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9-HF1 | Rational Design | N497A, R661A, Q695A, Q926A [44] | >85% for most sgRNAs [44] | Renders nearly all off-target events undetectable in GUIDE-seq for standard sites [44] |

| eSpCas9(1.1) | Rational Design | K848A, K1003A, R1060A [45] | Varies; can be similar to WT [47] | Effective in base editors (e-ABE7.10), showing high specificity ratios [47] |

| HypaCas9 | Rational Design | N692A, M694A, H698A [46] | Can be significantly reduced [47] | Improved specificity by stabilizing the Cas9 active state [46] |

| HiFi Cas9 | Engineered | Not specified in sources | Varies; guide-dependent significant loss for ~20% of sgRNAs [45] | Balanced fidelity and efficiency for many targets [45] |

| HyperDriveCas9 | Hybrid (Hyperactive + High-Fidelity) | Combines mutations from HypaCas9/HiFi and TurboCas9 [46] | High, rescues activity of parent high-fidelity enzymes [46] | Maintains low off-target cleavage while achieving high on-target editing [46] |

Table 2: Performance of High-Fidelity Cas9 in Adenine Base Editors (ABE) Data from HEK293T cells at the HEK4 site [47]

| Base Editor | Underlying Cas9 | On-Target Editing Efficiency | Relative Specificity Ratio (vs. ABE7.10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABE7.10 | Wild-Type SpCas9 | 9.40% ± 1.75% | 1.0 (Baseline) |

| e-ABE7.10 | eSpCas9(1.1) | 10.61% ± 2.42% | 15.8 - 54.5 |

| HF-ABE7.10 | SpCas9-HF1 | 4.25% ± 0.62% | 2.5 - 13.5 |

| Hypa-ABE7.10 | HypaCas9 | 4.25% ± 0.55% | 2.5 - 13.5 |

| evo-ABE7.10 | evoCas9 | 1.71% ± 0.21% | 3.8 - 10.5 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating HDR Efficiency and Off-Target Effects Using Cell Cycle-Dependent Genome Editing

This protocol is adapted from a study that integrated SpCas9-HF1 with cell cycle regulation to enhance editing precision [48].

- Plasmid Construction: Co-express your chosen high-fidelity Cas9 variant (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) with an anti-CRISPR protein (AcrIIA4) fused to Cdt1, a protein degraded after the G1 phase of the cell cycle. This fusion protein inhibits Cas9 during the G1 phase but allows activation in S/G2 phases when HDR is favored [48].

- Cell Transfection: Transfect your target cells (e.g., HEK293T) with the following:

- Plasmid expressing the high-fidelity Cas9 and AcrIIA4-Cdt1 fusion.

- Plasmid expressing the sgRNA targeting your gene of interest.

- A single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donor template for HDR.

- Flow Cytometry & Sorting: After 48 hours, use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate cells that successfully expressed the Cas9/sgRNA construct.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from sorted cells.

- On-Target Analysis: Amplify the target region by PCR and sequence using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to quantify HDR and indel frequencies.

- Off-Target Analysis: Use a method like GUIDE-seq [44] [24] to identify potential off-target sites genome-wide. Perform targeted amplicon sequencing on these nominated sites to confirm the absence of indels.

Protocol 2: Assessing Guide-Dependent Efficiency Loss with High-Throughput Viability Screens

This systematic approach helps identify sgRNAs that are incompatible with specific high-fidelity variants [45].

- Stable Cell Line Generation: Generate stable cell lines (e.g., DLD-1 or H2171) constitutively expressing wild-type SpCas9, HiFi Cas9, or LZ3 Cas9. Use western blotting to confirm comparable Cas9 expression levels across lines [45].

- Library Transduction: Transduce each cell line with a genome-wide lentiviral sgRNA library (e.g., at a low MOI to ensure single integration). Include a non-targeting sgRNA control pool.

- Selection and Cell Culture: Select transduced cells with puromycin. Passage the cells for about 14 days to allow for gene knockout and subsequent depletion of essential genes.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and NGS: Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA at the endpoint. Amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences from the genomic DNA and subject them to NGS.

- Data Analysis: Map the NGS reads to the sgRNA library. For each sgRNA, calculate the depletion fold-change between the initial and final time points. Compare the fold-change profiles across WT SpCas9 and the high-fidelity variants. sgRNAs with a significant loss of depletion signal in the high-fidelity lines indicate a variant-specific efficiency loss [45].

Mechanism Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for High-Fidelity Genome Editing

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Plasmids | Mammalian expression vectors for variants like SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9(1.1), HiFi, and HypaCas9. | Constitutive or transient expression of the nuclease in target cells. |

| GuideVar Software | A transfer learning-based computational framework for predicting on-target efficiency and off-target effects with high-fidelity variants [45]. | Prioritizing sgRNAs with high expected activity for HiFi or LZ3 Cas9. |

| GUIDE-seq Kit | A comprehensive method for the genome-wide unbiased identification of DSBs enabled by sequencing [44] [24]. | Empirically determining the off-target profile of your sgRNA and Cas9 variant combination. |

| Anti-CRISPR AcrIIA4-Cdt1 Fusion Plasmid | A tool for cell cycle-dependent Cas9 activation. Inhibits Cas9 in G1 phase, increasing HDR efficiency and reducing off-targets [48]. | Enhancing the precision of high-fidelity variants like SpCas9-HF1 for precise gene correction. |

| HyperDriveCas9 Plasmid | A hybrid Cas9 variant combining hyperactive and high-fidelity mutations to rescue on-target activity while maintaining low off-target cleavage [46]. | Overcoming the efficiency-fidelity trade-off in challenging-to-edit cell types. |

| Cas-OFFinder / CCTop | In silico tools for the nomination of potential CRISPR off-target sites in a reference genome [24]. | Initial computational prediction of potential off-target sites for a given sgRNA sequence. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Researcher Questions on Cas9 Nickase

Q1: What is a Cas9 nickase and how does it fundamentally differ from wild-type Cas9?

A Cas9 nickase (Cas9n) is a engineered variant of the wild-type Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) nuclease where one of its two nuclease domains is inactivated by a point mutation [49] [50]. Wild-type Cas9 creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) using its RuvC and HNH nuclease domains, which can lead to error-prone repair and off-target mutations [24]. In contrast, a nickase creates only a single-strand break, or "nick," in the DNA [50]. The two primary SpCas9 nickase variants are:

- Cas9 D10A: Carries a mutation in the RuvC domain and nicks the target strand (the strand complementary to the guide RNA) [49] [51].

- Cas9 H840A: Carries a mutation in the HNH domain and nicks the non-target strand [49] [51].

Q2: Why does using a nickase reduce off-target effects compared to wild-type Cas9?

Off-target effects occur when the Cas9-sgRNA complex binds and cleaves genomic sites with high similarity to the intended target sequence [24]. A single nick created by a nickase is typically repaired with high fidelity using the intact complementary DNA strand as a template, resulting in minimal unintended mutations [49] [52]. To create a mutagenic DSB with a nickase system, two proximal nicks on opposite strands are required—a strategy known as "double nicking" or "paired nicking" [53] [50]. The probability of a single off-target site having two functional, closely spaced off-target sequences for a pair of guide RNAs is exponentially lower than the probability of a single off-target site for one guide RNA, thereby dramatically increasing specificity [54] [52].

Q3: What are the key design rules for a double nickase experiment?

For efficient and specific editing using a double nickase system, follow these design parameters [49]:

- Nickase Variant: The Cas9 D10A nickase is generally more potent at mediating homology-directed repair (HDR) than the H840A variant [49].

- gRNA Pair Orientation: Design two gRNAs to target opposite DNA strands with a PAM-out orientation (where the PAM sequences for both gRNAs face away from each other) [49] [53].

- Spacing Between Nicks: The optimal distance between the two nicking sites is:

- 40–70 bp for Cas9 D10A

- 50–70 bp for Cas9 H840A [49]

- Complex Formation: For highest activity, form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for each gRNA separately before co-delivery into cells, rather than mixing all components in a single reaction [49].

Q4: Are there any limitations or undesired on-target effects associated with nickases?

Yes. While paired nickases greatly reduce off-target chromosomal rearrangements [54], they can still cause substantial on-target chromosomal aberrations, including large deletions and inversions [54]. However, the profile of these aberrations may be qualitatively different from those caused by nucleases, often including a higher proportion of insertions [54]. Furthermore, a 2023 study revealed that the commonly used nCas9 (H840A) can sometimes create DSBs instead of single nicks, due to residual activity in its HNH domain [51]. An improved variant, nCas9 (H840A + N863A), was shown to behave as a genuine nickase and significantly reduce unwanted indel formation [51].

Q5: How do nickases integrate into advanced editing systems like Prime Editing?

Prime Editors (PEs) are fusions of a Cas9 nickase (typically nCas9 H840A) to a reverse transcriptase enzyme [55] [27] [51]. They use a specialized guide RNA (pegRNA) to directly write new genetic information into a target site without requiring DSBs [27]. A key challenge with early PEs was the generation of unwanted indel byproducts [27] [51]. Recent advances (2023-2025) have engineered next-generation prime editors by incorporating additional mutations (e.g., K848A, H982A, N854A, N863A) into the Cas9 nickase domain. These "relaxed" or "genuine" nickases minimize the formation of DSBs, leading to a dramatic reduction in indel errors and significantly purer editing outcomes [27] [51].

Troubleshooting Common Nickase Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low Editing Efficiency with Paired Nickases

- Cause 1: Suboptimal gRNA pair design or spacing.