HDR vs NHEJ: Decoding DNA Repair Efficiency for Precision Genome Editing and Therapy

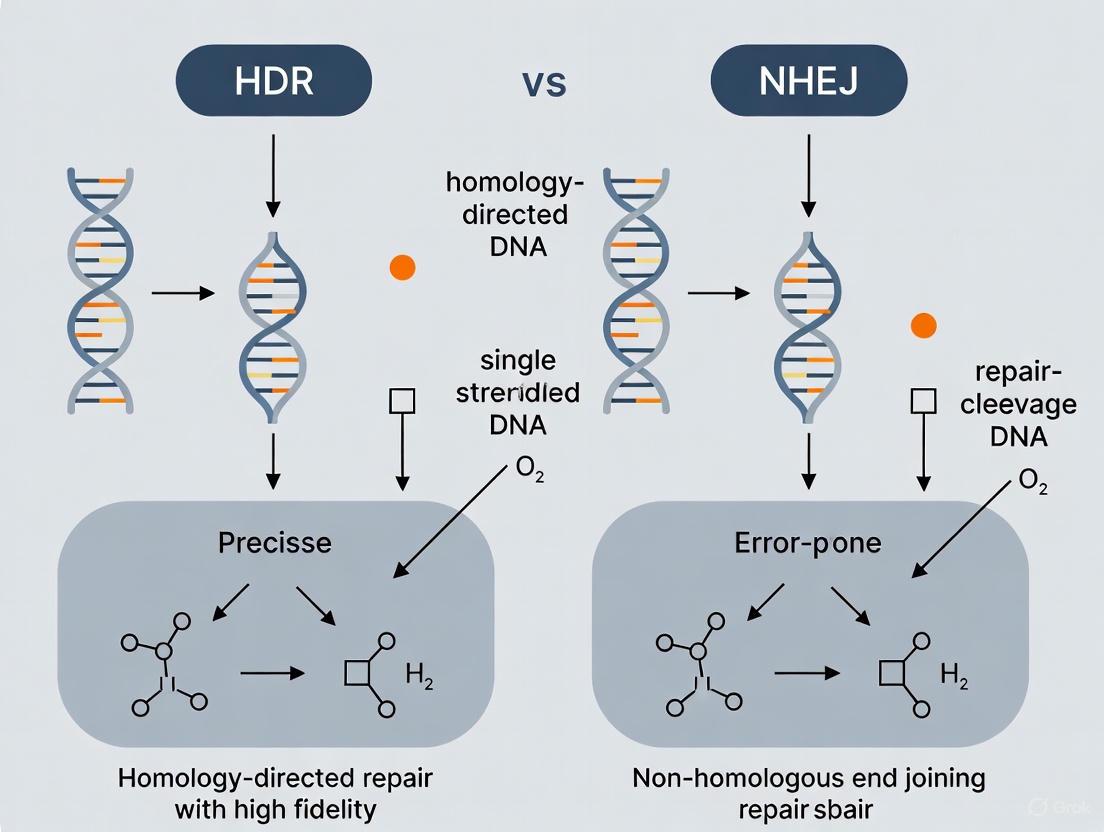

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the efficiency and application of the two primary DNA double-strand break repair pathways: Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) and Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ).

HDR vs NHEJ: Decoding DNA Repair Efficiency for Precision Genome Editing and Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the efficiency and application of the two primary DNA double-strand break repair pathways: Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) and Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental mechanisms of these pathways, their critical roles in CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, and the inherent competition that makes HDR less efficient than the error-prone NHEJ. The review details current methodologies to overcome this limitation, including strategic inhibition of NHEJ factors, cell cycle synchronization, and donor template optimization. Furthermore, we examine advanced validation techniques and comparative outcomes, concluding with the clinical implications of harnessing these repair pathways for targeted cancer therapies and treating genetic disorders.

The Cellular Battlefield: Fundamental Mechanisms of HDR and NHEJ

The Imperative of Genomic Integrity and the DNA Damage Response

The integrity of our genomic DNA is fundamental to cellular function and organismal health. However, DNA is constantly under assault from a variety of sources, including environmental agents like ultraviolet light and ionizing radiation, as well as endogenous threats like reactive oxygen species generated by cellular metabolism. [1] It is estimated that each cell must contend with 10,000 to 100,000 lesions per day. [1] Unrepaired DNA damage can severely disrupt essential processes like replication and transcription, leading to mutations, cellular senescence, apoptosis, and playing a major role in age-related diseases and cancer. [1]

To combat this relentless genomic erosion, cells have evolved a sophisticated network of mechanisms known as the DNA Damage Response (DDR). [1] This defense apparatus includes multiple DNA repair pathways, damage tolerance processes, and cell-cycle checkpoints that work together to safeguard genomic integrity. [1] The biological significance of a functional DDR is starkly illustrated by the severe consequences of inherited defects in DDR factors, which can result in immune deficiency, neurological degeneration, premature aging, and severe cancer susceptibility. [1]

Among the most cytotoxic types of DNA lesions are DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), which affect both strands of the DNA double helix. [1] The two major pathways for repairing DSBs are Homologous Recombination (HR, often used interchangeably with Homology-Directed Repair or HDR) and Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ). [2] These pathways differ fundamentally in their mechanism and fidelity.

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): HDR is a precise, error-free repair mechanism that operates by using an undamaged DNA template—such as a sister chromatid—to accurately repair the break and reconstitute the original DNA sequence. [2] This pathway is most active in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when a homologous template is available. [3]

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): In contrast, NHEJ is a faster but error-prone pathway that repairs breaks by directly ligating the two broken DNA ends together with little or no requirement for homology. [2] This "quick fix" often results in small insertions or deletions (INDELs) at the repair site. [3] A key advantage of NHEJ is that it is active throughout the entire cell cycle. [4]

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these two critical pathways.

| Feature | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) |

|---|---|---|

| Template Required | Yes (homologous DNA, e.g., sister chromatid) | No |

| Fidelity | High (error-free) | Low (error-prone) |

| Primary Phase of Cell Cycle | S and G2 | All phases (G1, S, G2) |

| Kinetics | Slow (7 hours or longer) [2] | Fast (approximately 30 minutes) [2] |

| Key Proteins | RAD51, BRCA1, BRCA2, Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 (MRX) complex [4] | Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer, DNA-PKcs, XRCC4, Ligase IV [5] |

| Primary Cellular Role | Accurate repair, restart of collapsed replication forks | Rapid repair of DSBs to maintain structural integrity |

| Common Outcome in CRISPR | Precise knock-in of genes or point mutations | Gene knockout due to INDEL formation [3] |

Quantitative Comparison of HDR and NHEJ Efficiency

Direct comparisons of the efficiency and kinetics of HDR and NHEJ in normal human cells reveal a clear dominance of the NHEJ pathway. Research using sensitive fluorescent reporter assays integrated into the chromosomes of human cells has allowed for real-time monitoring of these repair processes. [2]

The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings from these studies, providing a clear comparison of the relative performance of HDR and the two subtypes of NHEJ.

| Repair Pathway | Relative Efficiency in Cycling Cells | Average Repair Time | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ (Compatible Ends) | 6 | ~30 minutes | Most efficient form of DSB repair [2] |

| NHEJ (Incompatible Ends) | 3 | ~30 minutes | Best mimics naturally occurring DSBs; three times more efficient than HR [2] |

| HDR (Homologous Recombination) | 1 | 7 hours or longer | Highly accurate but slowest and least efficient pathway [2] |

Note: The "Relative Efficiency" is derived from the experimentally determined ratio of NHEJ-C : NHEJ-I : HR, which is approximately 6:3:1. [2]

Experimental Protocols for Assessing HDR and NHEJ Efficiency

To study these complex biological processes, scientists have developed robust experimental assays. The following are detailed methodologies for quantifying the efficiency of HDR and NHEJ, based on protocols used in recent research.

Protocol 1: Intermolecular Recombination Assay for HDR Efficiency

This protocol measures the frequency of Homologous Recombination (HR) in S. cerevisiae (yeast) using a plasmid-based system where a functional selectable marker is restored via recombination. [4]

Key Steps:

- Strain and Plasmid Preparation: Use yeast strains (e.g., W1588-4C) carrying a non-functional ura3-1 allele in their genome. Transform these strains with a high-copy number plasmid (e.g., pFAT10-G4) containing a different disrupted ura3 allele (ura3G4), which has been interrupted by G-quadruplex-forming DNA sequences. [4]

- Induction of DSBs and Recombination: The G-quadruplex sequences can stall DNA replication forks, leading to the formation of DSBs. The cell then attempts to repair this break via intermolecular HR between the two defective ura3 sequences on the plasmid and the chromosome. [4]

- Selection and Quantification: Plate the transformed yeast cells on synthetic complete (SC) medium lacking uracil. Only cells in which a functional URA3+ gene has been restored through a successful HR event will be able to form colonies. The number of Ura+ colonies is counted and compared to the total number of viable cells to determine the HR frequency. [4]

Protocol 2: "Suicide-Deletion" Assay for NHEJ Efficiency

This protocol, also used in S. cerevisiae, quantitatively measures the cell's ability to repair a specific, enzymatically-induced DSB via the NHEJ pathway. [4]

Key Steps:

- Use of Engineered Strain: Employ a specialized yeast strain (e.g., YW714) in which a cassette containing the gene for the I-SceI mega-endonuclease and a URA3 marker is flanked by parts of the ADE2 gene and integrated into the chromosome. [4]

- Induction of DSB: Grow the cells in a medium containing galactose to induce the expression of the I-SceI endonuclease. The expressed I-SceI enzyme cuts at its specific recognition site within the engineered cassette, creating a precise DSB. This cut also excises the I-SceI gene itself in a "suicide" event. [4]

- NHEJ Repair and Readout: The cell repairs this break via NHEJ, which rejoins the ends of the ADE2 coding sequence. Successful NHEJ restores a functional ADE2 gene. [4]

- Selection and Quantification: Plate the cells on SC medium lacking adenine. The number of Ade+ colonies that grow represents the number of successful NHEJ repair events. The NHEJ efficiency is calculated by comparing the number of Ade+ cells to the total number of viable cells. [4]

Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Repair Studies

The following table lists key reagents and materials essential for conducting the types of experiments described above and for broader research into DNA damage response pathways.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in DNA Repair Studies |

|---|---|

| Reporter Cell Lines | Stably express fluorescent (e.g., GFP) or selectable (e.g., URA3, ADE2) reporter constructs to visually track and quantify DNA repair events in live cells. [2] [4] |

| Site-Specific Endonucleases (e.g., I-SceI) | Used to create precise, controlled double-strand breaks at defined locations in the genome to study the subsequent repair. [2] [4] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | A versatile tool for generating targeted DSBs for gene editing; the cellular outcomes depend on whether the ensuing repair is handled by NHEJ (for knockouts) or HDR (for precise knock-ins). [3] |

| Synchronized Cell Cultures | Allow researchers to study the activity and regulation of DNA repair pathways (e.g., HDR) during specific phases of the cell cycle. [4] |

| Live-Cell DNA Damage Sensor | A recent innovation using a fluorescently tagged natural protein domain that binds reversibly to damaged DNA, enabling real-time imaging of damage and repair dynamics in living cells and organisms without disrupting the process. [6] |

| Specific Inhibitors (e.g., PARPi, ATRi, WEE1i) | Small molecule inhibitors that target specific DDR proteins (like PARP, ATR, or WEE1) are used to probe pathway function and are a major focus of cancer therapeutic development. [7] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathway Choice

This diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process a cell undergoes when a double-strand break is detected, leading to either the HDR or NHEJ repair pathway.

Experimental Workflow for HDR/NHEJ Efficiency Assay

This diagram outlines the key steps in the "suicide-deletion" and intermolecular recombination assays used to quantify NHEJ and HDR efficiency in yeast models.

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is the primary and most versatile DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair pathway in mammalian cells, functioning throughout the cell cycle without requiring a homologous template [8] [9] [10]. This "first responder" role places NHEJ at the forefront of cellular defense against the most dangerous form of DNA damage, including breaks induced by ionizing radiation, reactive oxygen species, and modern genome editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 [8] [10]. Unlike the precision of Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), which is restricted to specific cell cycle phases, NHEJ operates via direct ligation of broken DNA ends, often at the cost of introducing small insertions or deletions (indels) [11] [9]. This guide objectively compares the efficiency, mechanisms, and research applications of NHEJ against alternative repair pathways, providing researchers with the experimental data and methodologies needed to inform their experimental designs.

Quantitative Efficiency Comparison: NHEJ vs. Alternative Pathways

The efficiency of DSB repair pathways varies significantly based on cellular context, experimental system, and the nature of the DNA break. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Efficiency of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

| Repair Pathway | Key Characteristics | Reported Efficiency/Outcome | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Template-independent, error-prone, cell-cycle independent [8] [11]. | Primary repair pathway for CRISPR/Cas9-induced DSBs [10]. | Human cells (e.g., RPE1) using CRISPR-mediated knock-in [12]. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Template-dependent, high-fidelity, restricted to S/G2 phases [13] [11]. | Low efficiency; ~5-7% knock-in efficiency; increased to ~17-22% with NHEJ inhibition [12]. | Human cells (e.g., RPE1) using CRISPR-mediated knock-in [12]. |

| Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) | Uses microhomologies (2-20 nt), results in deletions [12] [10]. | Contributes to imprecise repair; its inhibition can increase HDR accuracy [12]. | Human cells (e.g., RPE1) using CRISPR-mediated knock-in [12]. |

| Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) | Uses longer homologous sequences, Rad52-dependent, causes deletions [12] [10]. | Contributes to asymmetric HDR and imprecise integration; its suppression reduces errors [12]. | Human cells (e.g., RPE1) using CRISPR-mediated knock-in [12]. |

| NHEJ Enhanced by Small Molecules | Pharmacological inhibition of competing pathways or enhancement of NHEJ. | RepSox increased NHEJ-mediated editing efficiency by 3.16-fold in a Cas9-RNP delivery system [14]. | Porcine PK15 cells using CRISPR/Cas9 [14]. |

The NHEJ Mechanism: A Step-by-Step Guide

The NHEJ pathway is a coordinated process involving specific protein complexes that recognize, process, and ligate broken DNA ends. The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism.

Diagram 1: The Core NHEJ Pathway and Key Inhibition Strategy. This illustrates the sequential steps in classical NHEJ, from initial break recognition to final ligation. The dashed line indicates how pharmacological inhibition targets this pathway.

Detailed Mechanism and Key Experimental Evidence:

- Step 1: End Binding and Tethering. The Ku70/80 heterodimer exhibits extraordinary affinity for DNA ends, binding within seconds of break formation in a sequence-independent manner [8] [9]. This binding serves as a scaffold for the recruitment of all subsequent NHEJ factors [8].

- Step 2: Complex Assembly and Stabilization. The DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) is recruited to form the active DNA-PK complex with Ku [8] [15]. The XRCC4-DNA Ligase IV (LIG4) complex, stabilized by XLF, is also recruited during this step [8] [16] [9]. Recent structural studies suggest a "Flexible Synapsis" model where Ku and XRCC4:LIG4 hold the two DNA ends in proximity, allowing for dynamic movement and sampling of different alignments before ligation [16].

- Step 3: End Processing. Most naturally occurring DSBs have damaged or incompatible ends that cannot be directly ligated [16]. Nucleases like Artemis process damaged DNA ends and hairpin structures, while dedicated X-family polymerases (Pol μ and Pol λ) add or remove nucleotides in a template-dependent or independent manner [16] [9] [10]. This step is often iterative, with multiple rounds of processing attempted until a ligatable state is achieved [16].

- Step 4: Ligation. The DNA Ligase IV complex, in conjunction with XRCC4 and XLF, performs the final ligation step, sealing the DNA break [8] [9]. XLF has been shown to promote the ligation of mismatched and non-cohesive ends and is critical for efficient repair [16] [9].

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating NHEJ

Protocol: Quantifying NHEJ Efficiency in CRISPR-Cas9 Editing

This protocol is adapted from studies that used flow cytometry and long-read amplicon sequencing to quantify NHEJ and HDR outcomes in human cell lines [12] [14].

- Cell Line Preparation: Use immortalized cell lines such as hTERT-RPE1 or primary cells like porcine PK15. Culture cells according to standard conditions.

- CRISPR-Cas9 and Donor Delivery:

- For knock-in experiments, design a donor DNA template with homology arms (e.g., 90 base pairs) flanking the desired insertion (e.g., a fluorescent protein like mNeonGreen) [12].

- Form Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes by mixing recombinant Cas9 or Cpf1 (Cas12a) nuclease with in vitro transcribed guide RNA (gRNA).

- Co-deliver the RNP complexes and donor DNA into cells via electroporation [12]. For knockout studies, the donor DNA is omitted.

- Small Molecule Treatment (Optional): Immediately after electroporation, treat cells with small molecules to modulate repair pathways [12] [14].

- Efficiency Quantification (4 Days Post-Electroporation):

- Flow Cytometry: For fluorescent protein knock-in, analyze the percentage of cells exhibiting the fluorescent signal to determine overall knock-in efficiency [12].

- Long-Read Amplicon Sequencing: Harvest genomic DNA. Amplify the target locus by PCR and subject the amplicons to long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio). Use computational frameworks like "knock-knock" to classify and quantify the precise repair outcomes (e.g., perfect HDR, indels from NHEJ, imprecise integration) [12].

Protocol: Measuring NHEJ-Specific Repair Using Reporter Assays

While not detailed in the provided results, a common method to specifically quantify NHEJ activity involves using engineered reporter cell lines (e.g., U2OS-DR or EJ5-GFP reporters). These systems contain a disrupted fluorescent or selectable marker gene that can only be restored upon successful NHEJ-mediated repair of a site-specific DSB induced by CRISPR-Cas9 or other nucleases. The frequency of NHEJ is then directly measured by flow cytometry for the restored marker.

Advanced Research: Pathway Interplay and NHEJ Modulation

The simplistic model of NHEJ competing only with HDR is outdated. Recent research reveals a complex interplay between multiple DSB repair pathways. Even with potent NHEJ inhibition, the proportion of "perfect HDR" events remains below 50%, with the remaining integrations being attributed to other non-HDR pathways like MMEJ and SSA [12]. This underscores that simply inhibiting NHEJ is insufficient for achieving perfect gene integration and suggests that combined inhibition of NHEJ and SSA may be a more effective strategy to boost precise editing efficiency [12].

Furthermore, cancer cells, particularly glioma stem-like cells (GSCs), can upregulate NHEJ to enhance their DNA repair capacity and foster therapeutic resistance. A 2025 study identified AATF (apoptosis antagonizing transcription factor) as a key regulator that stabilizes the core NHEJ protein XRCC4, leading to elevated NHEJ activity and resistance to chemoradiotherapy in glioblastoma [15]. This highlights NHEJ as a promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for NHEJ Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 | Potent NHEJ pathway inhibitor [12]. | Increased HDR-based knock-in efficiency from ~5-7% to ~17-22% in human RPE1 cells [12]. |

| Repsox | Small molecule inhibitor of the TGF-β pathway [14]. | Increased CRISPR/Cas9-mediated NHEJ gene editing efficiency by 3.16-fold in porcine PK15 cells [14]. |

| ART558 | Inhibitor of POLQ, a key effector of the MMEJ pathway [12]. | Reduced large deletions and complex indels, increasing the frequency of perfect HDR events [12]. |

| D-I03 | Specific inhibitor of Rad52, a central protein in the SSA pathway [12]. | Reduced asymmetric HDR and other donor mis-integration events, thereby elevating knock-in accuracy [12]. |

| AATF Depletion (shRNA) | Knocks down AATF to disrupt its stabilization of XRCC4 [15]. | Impaired NHEJ repair, sensitized glioblastoma xenografts to chemoradiotherapy, and increased DNA damage (γ-H2AX foci) [15]. |

NHEJ's role as the cell's dominant and fastest "first responder" to DSBs is well-established, supported by robust quantitative data showing its supremacy in repairing CRISPR-Cas9-induced breaks. However, the emerging paradigm is that efficient and precise genome editing requires a nuanced understanding of the entire network of DSB repair pathways, including the significant contributions of MMEJ and SSA. The experimental data and protocols outlined here provide researchers with a framework to objectively compare repair efficiencies and select appropriate strategies—whether the goal is efficient gene knockout via NHEJ, high-fidelity knock-in via HDR enhancement, or overcoming therapeutic resistance in cancer by targeting upregulated NHEJ. Future research will continue to refine small-molecule modulators and combinatorial targeting of these pathways to achieve ultimate control over genomic integrity.

In the realm of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, two primary DNA repair pathways compete to resolve double-strand breaks (DSBs): the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and the precise homology-directed repair (HDR). While NHEJ is the dominant and faster pathway in most cells, HDR serves as the cell's precision engineer, enabling accurate, template-driven corrections. This guide objectively compares the efficiency of HDR against NHEJ, detailing the experimental strategies that leverage and enhance HDR for applications demanding high fidelity, from basic research to therapeutic development.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research by functioning as a programmable pair of "molecular scissors" to create targeted DSBs in the genome [3]. However, the actual genetic outcome is determined by the cell's own endogenous DNA damage repair (DDR) mechanisms [3]. The competition between HDR and NHEJ is a central challenge in genome engineering.

- NHEJ (The Quick Fix): This pathway operates throughout the cell cycle and functions by directly ligating the broken DNA ends together. It is fast and efficient but inherently error-prone, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the repair site. This makes it ideal for gene knockout studies [3] [17].

- HDR (The Precision Engineer): HDR is a more accurate, template-dependent mechanism. It uses a homologous DNA sequence—such as a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor template—to repair the break in an error-free manner. Its major limitation is that it is restricted primarily to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, making it naturally less efficient than NHEJ in most contexts [3] [17] [18].

The inherent cellular preference for NHEJ significantly limits the efficiency of precise genome editing, driving the need for strategies to shift this balance toward HDR.

Quantitative Comparison: HDR vs. NHEJ Efficiency

The following tables summarize key experimental data highlighting the relative performance and outcomes of HDR and NHEJ across different systems and conditions.

Table 1: Comparative Efficiency of HDR and NHEJ in Different Cell Types

| Cell Type / Organism | Editing System | HDR Efficiency | NHEJ Efficiency | Key Experimental Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K562 (Human cells) | Cas9-DN1S fusion | ~86% | Significantly reduced | Fusion protein locally inhibits NHEJ, dramatically favoring HDR. | [19] |

| Patient-derived B lymphocytes | Cas9-DN1S fusion | ~70% of alleles | ~7% of alleles | Clinically relevant system for precise gene correction in patient cells. | [19] |

| Aspergillus niger (Fungus) | CRISPR/Cas9 | High integration efficiency (91.4%) | - | HDR-based gene integration system shows high success rate. | [20] |

| Potato Protoplasts | RNP + ssDNA donor | Up to 1.12% of sequencing reads | - | ssDNA donors in "target" orientation achieve highest HDR. | [21] |

| General Eukaryotic Cells | Standard CRISPR/Cas9 | Low (requires donor, cell cycle phase) | High (dominant pathway) | HDR efficiency is limited by cell cycle and donor availability. | [3] [17] |

Table 2: Impact of Donor Template Design on HDR Efficiency

| Donor Template Type | Typical Insert Size | Recommended Homology Arm (HA) Length | Reported HDR Efficiency | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-stranded DNA (ssODN) | 1 - 50 bp | 30 - 50 nucleotides | 25% - 50% in mouse models (Easi-CRISPR); up to 1.12% in potato [21] | Shorter HAs possible; high efficiency for small edits [18]. |

| Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) plasmid | Large inserts (e.g., fluorescent proteins) | 500 - 1,000 bp | Generally low | Can be improved using linearized or self-cleaving plasmids [18]. |

| dsDNA (PCR-generated) | 1 - 5 kb | 200 bp - 2,000 bp | Increases with longer HA (from 200 bp to 10,000 bp) [21] | More toxic to cells than plasmids [18]. |

| Circular ssDNA (cssDNA) | - | - | Up to 70% knock-in in iPSCs | Emerging non-viral method for high-efficiency knock-in [22]. |

Methodological Deep Dive: Experimental Protocols for Enhancing HDR

Local Inhibition of NHEJ Using Cas9 Fusion Proteins

A groundbreaking approach to enhance HDR involves fusing Cas9 to a dominant-negative fragment of 53BP1 (DN1S) [19].

- Rationale: 53BP1 is a key cellular protein that promotes NHEJ and inhibits the initiation of HDR by blocking DNA end resection. A dominant-negative version (DN1S) competes with endogenous 53BP1, preventing its recruitment and thereby tipping the balance toward HDR [19].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Construct Design: Fuse the DN1S fragment to Cas9 nuclease.

- Delivery: Co-deliver the Cas9-DN1S fusion construct along with guide RNAs and a donor template into target cells (e.g., via lentiviral transduction or electroporation).

- Mechanism of Action: The Cas9-DN1S fusion is recruited specifically to the Cas9-induced DSB. The DN1S moiety locally displaces endogenous 53BP1, inhibiting NHEJ at the cut site without globally affecting NHEJ throughout the genome. This locally permissive environment promotes the use of the co-delivered donor template for HDR [19].

- Key Data: This method achieved HDR frequencies of 86% in K562 cells and nearly 70% in patient-derived B lymphocytes, while simultaneously reducing NHEJ events at the target site to as low as 7% [19].

Optimization of Donor Repair Template (DRT) Design

The structure and composition of the DRT are critical determinants of HDR success [21] [18].

- Strandedness: Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors often outperform double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) donors, especially for smaller edits [21] [18].

- Orientation: For ssDNA donors, the "target" orientation (matching the strand bound by the sgRNA) frequently results in higher HDR efficiency compared to the "non-target" orientation [21].

- Homology Arm Length: While longer HAs (up to 1-2 kb) are recommended for dsDNA plasmids, ssDNA donors can facilitate HDR even with very short HAs (30-100 nucleotides) [21] [18].

- Disruption of Target Site: The donor template should be designed to disrupt the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) or the guide RNA binding site to prevent continuous re-cutting of the successfully edited allele by Cas9 [18].

Strategic Delivery of CRISPR Components

The method used to deliver the CRISPR machinery and donor template profoundly impacts HDR outcomes [22].

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Delivery: Direct delivery of pre-assembled Cas9 protein and guide RNA complexes (RNPs) via electroporation is a highly effective strategy. It leads to rapid editing, reduces off-target effects, and, because the Cas9 protein degrades quickly, provides a transient window of activity that can favor HDR when a donor is present [22].

- Viral vs. Non-Viral Delivery:

- Viral Vectors (e.g., Lentivirus, AAV) offer high transduction efficiency but have limited packaging capacity (especially AAV) and can trigger immune responses.

- Non-Viral Methods (e.g., Electroporation, Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)) are well-suited for delivering RNP complexes and ssDNA donors. Electroporation is particularly effective in hard-to-transfect cells like stem cells and primary T cells, and parameters (voltage, pulse length) can be optimized to improve cell viability and HDR efficiency [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HDR Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HDR Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9-DN1S Fusion Protein | Local inhibition of NHEJ at the cut site to enhance HDR. | Achieving >80% HDR in human cell lines for precise gene correction [19]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Engineered nucleases with reduced off-target activity. | Improving the safety profile of therapeutic editing by minimizing unintended mutations [23]. |

| Single-Stranded DNA (ssODN) | Donor template for introducing small edits (point mutations, short tags). | High-efficiency HDR (25-50%) for creating specific point mutations in mouse models [18]. |

| Self-Cleaving Donor Plasmid | Circular dsDNA template that releases a linear fragment upon Cas9 cleavage. | Increasing the effective concentration of linear donor template to improve HDR rates [18]. |

| DNA-PKcs Inhibitors | Small molecules that chemically inhibit a key NHEJ protein. | Boosting HDR efficiency; however, recent studies link them to increased genomic structural variations [23]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Non-viral delivery vehicle for mRNA and ssDNA donors. | Clinically relevant delivery of HDR components to primary T cells and stem cells [22]. |

Risks and Considerations in HDR Enhancement

Strategies to enhance HDR, particularly global inhibition of NHEJ, are not without risks. Recent studies reveal that the use of certain small-molecule NHEJ inhibitors, such as DNA-PKcs inhibitors, can lead to severe unintended consequences. These include a significant increase in large-scale, on-target genomic aberrations, such as kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [23].

These findings underscore a critical safety consideration:

- Overestimation of HDR: Traditional short-read sequencing methods can miss these large deletions if they remove the PCR primer binding sites, leading to an overestimation of true HDR efficiency and an underestimation of editing-induced errors [23].

- Safety Advantage of Local Inhibition: In contrast, localized strategies like the Cas9-DN1S fusion, which avoids global NHEJ inhibition, did not show an increased frequency of translocations in studies, suggesting a potentially safer profile for therapeutic applications [19] [23].

HDR remains the gold standard for precision genome editing, enabling everything from single-nucleotide corrections to the insertion of large transgenic elements. The direct comparison with NHEJ reveals a fundamental trade-off: efficiency for precision. While NHEJ is highly efficient for disruption, HDR, though less efficient, is unmatched in its accuracy.

The future of HDR research lies in developing smarter, safer, and more efficient strategies. This includes:

- Next-Generation Fusions: Engineering new Cas9 fusions that more potently recruit HDR factors or inhibit NHEJ with even greater specificity.

- Advanced Delivery Systems: Refining non-viral delivery platforms, like LNPs, for the co-delivery of RNP and donor templates with high efficiency and low toxicity.

- Temporal Control: Using cell-cycle regulators or inducible systems to activate Cas9 specifically during HDR-permissive phases (S/G2).

- Rigorous Safety Profiling: Employing long-read sequencing and other advanced assays to thoroughly evaluate the genomic integrity of cells edited with HDR-enhancing techniques.

As these tools and methodologies continue to mature, the precision engineer that is HDR will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in realizing the full therapeutic potential of CRISPR-based medicine.

This guide provides an objective comparison of the core protein complexes governing the two primary pathways for DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair: the Ku complex in Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and the RAD51 nucleoprotein filament in Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). Understanding their distinct mechanisms, efficiencies, and competitive interplay is fundamental to advancing gene therapy and precision genome editing.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are among the most cytotoxic DNA lesions, and their misrepair can lead to genomic instability, a hallmark of cancer and other diseases [24]. Mammalian cells possess three principal mechanisms to repair DSBs: the rapid but error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), the high-fidelity Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), and the mutagenic Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) [25]. The choice between these pathways is not random but is governed by a hierarchical control system to optimize for both cell survival and genomic integrity [25]. At the heart of this decision are the key protein machineries: the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer (Ku complex) that initiates NHEJ and the RAD51 recombinase that executes the central strand invasion step of HDR [25] [24]. Their functions are largely antagonistic, and the balance between them determines the accuracy and outcome of DSB repair, a critical consideration for therapeutic genome editing where HDR-mediated precision is often desired but competes with the highly efficient NHEJ [26] [27].

Protein Machinery: Core Components and Mechanisms

The Ku Complex: Gatekeeper of Non-Homologous End Joining

The Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer is the essential initiator of the canonical NHEJ pathway. Its primary function is to recognize and bind to free DNA ends with high affinity, acting as a first responder to DSBs [25] [27]. This binding event triggers a cascade of protein recruitment: the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) is recruited and activated, which in turn aligns the broken DNA ends and facilitates the recruitment of processing enzymes like the Artemis nuclease and polymerases Pol μ and Pol λ to modify the DNA ends. Finally, the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex catalyzes the ligation step to reseal the DNA backbone [27]. A key feature of the Ku complex is its role as a barrier to DNA end resection. By binding the ends, Ku physically protects them from nucleolytic degradation and prevents the initiation of the resection process that is a prerequisite for HDR and other homologous recombination pathways [25] [27]. The pro-NHEJ factor 53BP1 further reinforces this blockade by inhibiting the HDR-promoting factor BRCA1 [27]. This mechanism ensures that NHEJ remains the dominant and fastest repair pathway across all phases of the cell cycle.

The RAD51 Filament: Engine of Homology-Directed Repair

In contrast to NHEJ, HDR is a high-fidelity process that requires a homologous DNA template and is restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [24] [27]. The RAD51 recombinase is the central engine of HDR. Its function begins after the initial steps of DSB recognition and 5' to 3' end resection, which generate single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs. These ssDNA tails are first coated by Replication Protein A (RPA). With the assistance of mediators like BRCA2 and the RAD51 paralogs (RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, XRCC2, XRCC3), RAD51 displaces RPA to form a helical nucleoprotein filament on the ssDNA [24]. This filament is a dynamic structure that performs the critical reactions of homology search and strand invasion. It invades a homologous donor DNA duplex (typically the sister chromatid), forms a three-stranded synaptic intermediate called a Displacement Loop (D-loop), and stably pairs the invading strand with the complementary sequence [28]. The structure of this synaptic complex reveals how the RAD51 filament engages the donor DNA, facilitates base-pairing, and captures the displaced strand [28]. The invading 3' end then serves as a primer for DNA synthesis, using the donor template to copy the genetic information lost at the break site, enabling precise, error-free repair.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Ku Complex and RAD51 Machinery.

| Feature | Ku Complex (NHEJ Initiator) | RAD51 Filament (HDR Executor) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Function | DSB end recognition and protection; NHEJ scaffold | Homology search & strand invasion; HDR catalysis |

| Key Components | Ku70, Ku80, DNA-PKcs, Artemis, XRCC4/LigIV | RAD51, BRCA2, RAD51 paralogs, RPA |

| Primary Pathway | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

| Template Used | None (direct end-joining) | Homologous DNA (e.g., sister chromatid) |

| Fidelity | Error-prone (often indels) [27] | High-fidelity (precise repair) [27] |

| Cell Cycle Preference | All phases (G1, S, G2) [24] [27] | Primarily S and G2 phases [24] [27] |

| Initiation Signal | Free double-stranded DNA ends | Resected single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs |

| Dominance Hierarchy | Dominant; suppresses GC and SSA [25] | Recessive; promoted when NHEJ is impaired [25] |

Pathway Competition and Hierarchical Control

The cellular choice between NHEJ and HDR is a tightly regulated, hierarchical process. Experimental evidence from Ku80-deficient cells demonstrates that NHEJ is the dominant pathway, as its loss led to a 6- to 8-fold increase in the use of both Gene Conversion (GC, a form of HDR) and Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) [25]. This establishes a repair hierarchy where NHEJ takes precedence over homologous pathways. The competition occurs primarily at the level of DNA end resection. The binding of the Ku complex to DNA ends creates a physical barrier that inhibits resection, thereby protecting the break from nucleases and locking it into an NHEJ-favored state [27]. The pro-NHEJ factor 53BP1 further stabilizes this block. To initiate HDR, this blockade must be overcome by pro-resection factors like BRCA1 and CtIP, which promote the limited end resection that commits the break to homology-dependent repair [27]. The regulation is also kinetic; NHEJ is a faster process, while HDR involves more slow, complex steps including filament assembly, homology search, and DNA synthesis [27]. Furthermore, the regulation is reversible and can be influenced by effector protein levels. For example, loss of Rad51 function not only impairs HDR but also leads to an increase in the mutagenic SSA pathway, which can subsequently outcompete the remaining NHEJ capacity [25].

Diagram 1: Hierarchical Competition between NHEJ and HDR Pathways. The Ku complex binds DSB ends immediately, promoting NHEJ. Overcoming this blockade initiates end resection, committing the break to high-fidelity HDR via RAD51 filament assembly.

Experimental Data and Efficiency Comparison

Quantitative studies using chromosomal reporter constructs have directly measured the efficiency and interplay of these repair pathways. In wild-type Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells, NHEJ is the most active pathway for repairing a single I-SceI-induced DSB. However, genetic disruption of the Ku complex fundamentally alters this balance. Knocking out Ku80 causes a dramatic shift, increasing the usage of both HDR (Gene Conversion) and SSA by 6- to 8-fold [25]. This finding provides direct evidence for the dominance of NHEJ in pathway choice. Interestingly, impairing HDR by knocking down Rad51 does not alter NHEJ efficiency, suggesting that NHEJ operates independently. However, Rad51 knockdown in a context where SSA is available leads to a further increase in SSA activity, indicating that Rad51 indirectly promotes NHEJ by limiting the mutagenic SSA pathway [25]. In the context of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, this natural dominance of NHEJ presents a major challenge, as the desired precise HDR edits are typically outnumbered by error-prone NHEJ events, with HDR often constituting less than 10-20% of total repair outcomes in many cell types [26] [27].

Table 2: Quantitative Data on DSB Repair Pathway Efficiency and Manipulation.

| Experimental Condition | Effect on NHEJ Efficiency | Effect on HDR (GC) Efficiency | Effect on SSA Efficiency | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type Cells [25] | High (Baseline) | Low (Baseline) | Low (Baseline) | NHEJ is the dominant DSB repair pathway. |

| Ku80 Knock-Out [25] | Decreased | Increased by 6-8x | Increased by 6-8x | Loss of dominant NHEJ unlocks homologous repair. |

| Rad51 Knock-Down [25] | No significant change | Decreased | Increased | Rad51 is not required for NHEJ but suppresses SSA. |

| HDR Enhancement Strategies [26] [27] | Decreased (via inhibition) | Increased | Variable | NHEJ inhibition (e.g., Ku, DNA-PKcs, 53BP1) is a primary strategy to boost HDR for gene editing. |

Research Reagents and Methodologies

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Ku and RAD51 Function.

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|

| I-SceI Endonuclease | System for generating a single, specific DSB in chromosomal reporter constructs to study repair outcomes [25]. |

| GFP-Based Repair Substrates | Fluorescent reporters (e.g., pEJ for NHEJ, pGC for Gene Conversion) to quantitatively measure pathway efficiency via flow cytometry [25]. |

| siRNA/shRNA for Ku80/53BP1 | Tool for transiently knocking down key NHEJ factors to shift repair balance toward HDR in experimental settings [25] [27]. |

| siRNA/shRNA for RAD51 | Tool for impairing HDR function to study its role in repair fidelity and its interplay with SSA and NHEJ [25] [24]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., SCR7) | Small molecule inhibitors of NHEJ components (e.g., DNA Ligase IV) used to enhance HDR efficiency in genome editing [26] [27]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | High-resolution structural biology technique used to determine the atomic structure of complexes like the RAD51 D-loop [28]. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Pathway Hierarchy

The following protocol, adapted from foundational research, is used to quantitatively compare the efficiency of NHEJ, HDR (Gene Conversion), and SSA at a defined genomic locus [25]:

Cell Line Engineering: Stably integrate distinct GFP-based repair substrates into the genome of the chosen cell line (e.g., CHO K1).

- pEJ Substrate: For measuring NHEJ. Contains two out-of-frame I-SceI sites. Successful NHEJ repair restores the GFP reading frame.

- pGC Substrate: For measuring HDR/GC. Contains an inactivated GFP gene with an I-SceI site. A functional GFP is restored via HDR using a downstream homologous template.

- pEJSSA Substrate: For measuring SSA. Contains two directly repeated homologous sequences flanking an I-SceI cut site. Repair via SSA deletes the intervening sequence and restores GFP.

DSB Induction and Repair: Transfect the engineered cell lines with a plasmid expressing the I-SceI meganuclease to induce a single DSB within the integrated substrate. Include a control transfection without I-SceI to measure background fluorescence.

Flow Cytometry Analysis: 48-72 hours post-transfection, harvest the cells and analyze them by flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of GFP-positive cells in each sample.

Data Calculation and Interpretation:

- The percentage of GFP+ cells in the I-SceI-transfected sample (minus the background from the control) represents the absolute efficiency of each repair pathway.

- Comparing these values across pathways reveals their intrinsic hierarchy (e.g., NHEJ >> HDR ≈ SSA).

- Repeating this experiment in isogenic cell lines deficient in specific genes (e.g., Ku80-/- or Rad51-knockdown) directly reveals the genetic control and interdependency of the pathways, as shown in [25].

In the realm of DNA repair, the choice between homology-directed repair (HDR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) represents a fundamental fork in the road for maintaining genomic integrity. This decision becomes particularly crucial in CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing, where the desired editing outcome hinges on which pathway the cell employs to repair the programmed double-strand break (DSB). The HDR pathway enables precise, template-dependent repair, making it invaluable for introducing specific genetic modifications, while NHEJ functions as a rapid, error-prone ligation mechanism ideal for gene disruption [3] [11]. What governs this critical decision? A key determining factor is the cell cycle stage at which the DSB occurs. HDR is restricted primarily to the S and G2 phases, while NHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle, with its activity peaking in G1 and G2/M [29] [30]. Understanding this cell cycle dependence is not merely academic; it has profound implications for optimizing gene editing efficiency, particularly for precision therapeutic applications requiring HDR.

Mechanistic Basis of HDR Restriction to S and G2 Phases

The restriction of HDR to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle is not arbitrary but is enforced by multiple, interconnected molecular mechanisms. These controls ensure that HDR only proceeds when the necessary components are present and, critically, when an appropriate homologous repair template is available.

Template Availability: The Sister Chromatid

The most fundamental reason for HDR's cell cycle restriction is the availability of a homologous template. HDR requires an undamaged DNA sequence homologous to the region surrounding the break to guide accurate repair.

- G1 Phase: Cells in G1 possess only one copy of each chromosome. A DSB occurring in G1 has no homologous sister chromatid to use as a template, effectively eliminating the possibility of HDR and leaving NHEJ as the primary repair option [30].

- S and G2 Phases: After DNA replication in S phase, each chromosome consists of two identical sister chromatids. This provides the perfect template for error-free repair. The presence of this sister chromatid in S and G2 is a prerequisite for HDR, making it the preferred pathway when a break occurs after replication [30] [31].

Cell Cycle-Regulated Expression and Activation of Repair Proteins

The execution of HDR is dependent on a suite of proteins whose activity is tightly controlled by the cell cycle. The following table summarizes the key proteins and their cell cycle-dependent regulation.

Table 1: Key HDR Proteins and Their Cell Cycle Regulation

| Protein/Complex | Role in HDR | Cell Cycle Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| MRN Complex (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1) | Initial DSB recognition and end resection [30]. | Critical for HDR initiation; activity is favored in S/G2. |

| CtIP | Promotes short-range DNA end resection [32]. | Its phosphorylation by CDK is a pivotal step that restricts resection to S/G2 [32]. |

| BRCA1 & BRCA2 | Facilitates RAD51 loading onto single-stranded DNA [30]. | Function in S/G2 to promote homologous recombination. |

| RAD51 | Forms a nucleoprotein filament that catalyzes strand invasion of the homologous template [30]. | Expression and activity are upregulated in S phase [31]. |

The commitment to HDR is initiated by DNA end resection, a 5' to 3' nucleolytic degradation of one strand at the DSB to generate a 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhang. This step is the first and most critical point of cell cycle control. The resection process is activated by phosphorylation events mediated by cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), which are active only in S and G2 phases [32]. Specifically, CDK-dependent phosphorylation of CtIP activates its function, enabling it to work with the MRN complex to initiate resection. Once extensive resection occurs, the resulting 3' ssDNA overhang is coated by RPA and then replaced by RAD51 with the help of BRCA2. The RAD51-ssDNA filament then invades the homologous sister chromatid to initiate the repair synthesis [30]. This series of events makes resection an irreversible commitment point that channels the DSB into the HDR pathway, a process permitted only when CDK activity is high.

Diagram: The HDR Pathway is Gated by Cell Cycle-Dependent Resection

Quantitative Comparison of HDR and NHEJ Efficiency Across the Cell Cycle

The mechanistic control of HDR translates into clear quantitative differences in repair pathway efficiency throughout the cell cycle. A seminal study using hTERT-immortalized diploid human fibroblasts with chromosomally integrated fluorescent reporters provided direct measurements of this phenomenon [29]. The experimental workflow and resulting data are summarized below.

Experimental Protocol for Cell Cycle Analysis

To quantitatively measure HDR and NHEJ efficiency, researchers utilized the following methodology [29]:

- Cell Line Preparation: hTERT-immortalized normal human fibroblasts (HCA2-hTERT) containing integrated GFP-based NHEJ and HR reporter constructs were used.

- Cell Cycle Synchronization:

- G1 Arrest: Achieved via contact inhibition at confluence.

- S Phase Arrest: Induced by treatment with aphidicolin, a DNA polymerase α inhibitor.

- G2/M Arrest: Induced by treatment with colchicine, which prevents microtubule polymerization.

- DSB Induction and Repair Analysis: Synchronized cells were transfected with an I-SceI endonuclease plasmid to create a site-specific DSB within the reporter cassette and a DsRed plasmid to normalize for transfection efficiency.

- Flow Cytometry Quantification: Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry 4 days post-transfection. The ratio of GFP+ to DsRed+ cells was used as a measure of repair efficiency. Reconstitution of a functional GFP gene indicated successful NHEJ or HDR event, depending on the reporter design.

Table 2: Quantitative Efficiency of HDR and NHEJ Across the Cell Cycle in Human Fibroblasts [29]

| Cell Cycle Phase | NHEJ Efficiency (Relative to G1) | HDR Efficiency | Major Repair Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Baseline (1.0X) | Nearly absent | NHEJ (almost exclusive) |

| S | Increased (~1.5 to 3.0X) | Most active | Both active (HDR peaks) |

| G2/M | Highest activity (G1 < S < G2/M) | Declines from S phase peak | NHEJ (dominant) |

This data directly challenges a simplistic model where NHEJ is solely a G1 pathway and HDR is uniformly active in S/G2/M. Instead, it reveals that while HDR is indeed restricted to post-replicative phases, its efficiency peaks specifically during S phase and declines in G2/M. Conversely, NHEJ is not confined to G1 but is active throughout the cycle, with its highest activity observed in G2/M. The overall efficiency of NHEJ was higher than HR at all cell cycle stages, establishing it as the major DSB repair pathway in human somatic cells [29].

Research Reagent Solutions for HDR Studies

To investigate and manipulate HDR, researchers rely on a specific toolkit of reagents and methodologies. The table below details key solutions for studying cell cycle-dependent HDR.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for HDR Studies

| Reagent / Method | Function / Purpose | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Reporter Cassettes | Quantify HDR and NHEJ events via flow cytometry. | Provides direct, quantitative measurement of repair efficiency. Requires stable cell line generation [29]. |

| Cell Cycle Synchronization Agents | Arrest cells at specific cell cycle stages. | Aphidicolin (S phase), Colchicine (G2/M), Contact Inhibition (G1). Essential for delineating cell cycle-specific effects [29]. |

| Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) Donors | Serve as synthetic repair templates for HDR. | Favored for point mutations; lower cytotoxicity and higher specificity than dsDNA donors. Optimal homology arm length is ~40 bases [32] [33]. |

| 5'-Modified Donors (5'-Biotin, 5'-C3 Spacer) | Enhance HDR efficiency and precision. | 5'-modifications can boost single-copy integration by up to 20-fold by preventing donor multimerization and improving recruitment [33]. |

| RAD52 Supplementation | Stimulates RAD51-independent strand exchange. | Can increase ssDNA integration nearly 4-fold, but may increase template multiplication (concatemer formation) [33]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., SCR7) | Shift repair balance towards HDR by suppressing competing NHEJ. | Can be used as small-molecule additives to enhance HDR outcomes [34] [30]. |

Implications for Genome Editing and Therapeutic Development

The cell cycle restriction of HDR presents a significant bottleneck for precision genome editing, particularly in therapeutically relevant non-dividing or slowly dividing cells, such as neurons or stem cells in G0 [34] [32]. Consequently, strategies to enhance HDR efficiency often focus on overcoming this limitation.

- Timing of Nuclease Delivery: Delivering CRISPR-Cas9 components to cells during S phase, when HDR is most active, can significantly improve precise editing outcomes [32].

- Manipulating Cell Cycle Regulators: Co-delivering Cas9 with factors that transiently induce or synchronize cells into S phase is an active area of research.

- Inhibiting the Competing NHEJ Pathway: Using small molecule inhibitors of key NHEJ proteins (e.g., DNA-PKcs inhibitors) can tilt the repair balance in favor of HDR [34] [32].

- Exploiting Alternative Repair Pathways: For certain applications, alternative pathways like Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ), which is more active in S/G2 than G1, can be leveraged for precise edits without a strict requirement for a sister chromatid [30].

Understanding the intricate cell cycle dependence of HDR is therefore not just a biological curiosity but a critical consideration for designing effective gene editing experiments and developing the next generation of genetic therapies.

The integrity of genomic DNA is continuously challenged by a variety of damaging agents originating from both internal cellular processes and external environmental exposures. These insults lead to diverse DNA lesions, which cells must accurately repair to maintain genomic stability and prevent malignant transformation. The choice of DNA repair pathway is heavily influenced by the nature of the DNA damage, with endogenous and exogenous damage types often engaging distinct repair mechanisms. Understanding this complex interplay is crucial for advancing cancer therapeutics, particularly in the context of homology-directed repair (HDR) versus non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) efficiency research.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of endogenous and exogenous DNA damage, focusing on how these damage origins influence repair pathway choice. We present structured experimental data, detailed methodologies for assessing repair efficiency, and key reagent solutions to support research in targeted cancer therapy and drug development.

DNA Damage Origins and Characteristics

Table 1: Comparison of Endogenous vs. Exogenous DNA Damage Characteristics

| Characteristic | Endogenous DNA Damage | Exogenous DNA Damage |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Internal cellular processes [35] [36] | External environmental factors [35] [36] |

| Primary Sources | Reactive oxygen species (ROS), replication errors, hydrolytic damage, cellular metabolites [37] [35] [36] | UV radiation, ionizing radiation, chemical mutagens, environmental pollutants [35] [36] |

| Daily Burden per Cell | Approximately 100,000 lesions per day [36] | Variable depending on exposure |

| Common Lesion Types | Base modifications, single-strand breaks (SSBs), apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites [37] [35] | Double-strand breaks (DSBs), pyrimidine dimers, bulky adducts, crosslinks [37] [35] |

| Representative Lesions | 8-oxoguanine, uracil misincorporation, base deamination [35] [36] | Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, benzo[a]pyrene adducts, DNA-protein crosslinks [38] [35] |

| Repair Pathways Typically Engaged | Base excision repair (BER), mismatch repair (MMR) [39] [35] | Nucleotide excision repair (NER), homologous recombination (HR), non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [39] [35] |

Endogenous DNA damage arises spontaneously from normal cellular metabolic processes, with reactive oxygen species (ROS) representing a significant source. ROS are produced during cellular respiration and can cause various DNA lesions including base modifications, single-strand breaks, and abasic sites [37] [35]. Other endogenous sources include replication errors, hydrolytic damage through deamination and depurination, and base tautomerism [36]. The high daily burden of endogenous lesions necessitates efficient constitutive repair mechanisms.

Exogenous DNA damage results from environmental agents including ultraviolet (UV) and ionizing radiation, chemical mutagens, and pollutants [35]. UV radiation primarily induces pyrimidine dimers and 6-4 photoproducts, while ionizing radiation causes single- and double-strand breaks [35]. Chemical mutagens include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (found in tobacco smoke and vehicle exhaust), alkylating agents, and aromatic amines, which typically form bulky DNA adducts and crosslinks that distort the DNA helix [35] [36]. The diversity of exogenous lesions engages multiple specialized repair pathways.

DNA Damage Repair Pathways

Table 2: DNA Repair Pathways and Their Applications

| Repair Pathway | Key Damage Types Repaired | Mechanism | Fidelity | Cell Cycle Preference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Excision Repair (BER) | Oxidative damage, alkylated bases, base loss [39] [35] | Damage-specific glycosylase recognition, base removal, strand incision, patch synthesis [35] | High | All phases |

| Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER) | Bulky adducts, pyrimidine dimers, crosslinks [39] [35] | Damage recognition, dual incision, oligonucleotide excision, repair synthesis [35] | High | All phases |

| Mismatch Repair (MMR) | Replication errors, base-base mismatches, insertion-deletion loops [35] [36] | Mismatch recognition, strand discrimination, excision, resynthesis [35] | High | S, G2 phases |

| Homologous Recombination (HR) | Double-strand breaks, interstrand crosslinks [4] [39] [35] | End resection, strand invasion, DNA synthesis, resolution [35] [40] | Error-free | S, G2 phases |

| Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Double-strand breaks [4] [39] [35] | End recognition, end processing, ligation [35] [40] | Error-prone | All phases |

The choice between these repair pathways is influenced by multiple factors including the cell cycle phase, chromatin context, and the specific nature of the DNA lesion. Homologous recombination is restricted to S and G2 phases when sister chromatids are available as repair templates, while NHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle [35] [40]. Recent research has revealed that epigenetic landscape and cell identity factors significantly influence DNA repair pathway choice, with certain chromatin states preferentially engaging specific repair mechanisms [41].

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting the appropriate DNA repair pathway based on damage type and cellular context:

Experimental Approaches for Assessing Repair Pathway Efficiency

DSB-Spectrum Reporter Assay for Multi-Pathway Repair Analysis

The DSB-Spectrum system is a Cas9-based fluorescent reporter that simultaneously quantifies the contribution of multiple DNA repair pathways at a single DNA double-strand break [40]. This approach enables researchers to study pathway competition and crosstalk under defined experimental conditions.

Experimental Protocol:

Reporter Design: The DSB-Spectrum_V1 construct contains a CMV promoter driving a modified blue fluorescent protein (BFP) gene with a 46 bp spacer insert, followed by a truncated green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene lacking a promoter [40].

Cell Line Generation:

- HEK 293T cells are infected with DSB-Spectrum_V1 lentivirus at low multiplicity of infection

- Single-cell clones are expanded and validated for single-copy integration using Splinkerette PCR

- Genomic integration sites are mapped and confirmed by Southern blotting [40]

DSB Induction and Repair Analysis:

- Cells are transfected with Cas9 and guide RNAs targeting the edges of the BFP spacer sequence

- After 48-72 hours, cells are analyzed by flow cytometry

- BFP+ cells indicate error-free c-NHEJ repair

- GFP+ cells indicate HR-mediated repair using the truncated GFP as a template

- Double-negative cells indicate mutagenic repair (alternative NHEJ or single-strand annealing) [40]

Applications: This system has been used to demonstrate that inhibiting DNA-PKcs (a c-NHEJ factor) increases not only HR but also mutagenic single-strand annealing, revealing important pathway crosstalk [40].

Yeast-Based Systems for HR and NHEJ Efficiency Quantification

Intermolecular Homologous Recombination Assay in S. cerevisiae:

Strain Preparation: Use S. cerevisiae strains with non-functional ura3-1 allele at the genomic locus [4].

Plasmid Transformation: Transform with pFAT10-G4 plasmid containing ura3G4 allele disrupted by G-quadruplex-forming sequences [4].

HR Induction and Selection:

- Plate transformed yeast on synthetic complete medium lacking uracil

- Failed replication across G-quadruplex structures generates DSBs

- Cells initiate repair via recombination between plasmid and genomic ura3 alleles

- Count Ura3+ papillae to determine HR frequency [4]

Suicide-Deletion Assay for NHEJ Efficiency in S. cerevisiae:

Strain Engineering: Use yeast strains with galactose-inducible I-SceI mega-endonuclease and URA3 cassette flanked by ADE2 sequences integrated into chromosome XV [4].

DSB Induction: Grow cells in galactose-containing medium to induce I-SceI expression, generating specific DSBs.

NHEJ Assessment:

- After DSB generation, the I-SceI coding sequence is deleted

- Broken ends are rejoined via NHEJ, restoring ADE2 coding sequence

- Plate cells on adenine-free medium and count Ade2+ colonies to quantify NHEJ efficiency [4]

Small Molecule Screening for Repair Pathway Modulation

Experimental Approach for Enhancing CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated NHEJ:

Cell Culture and Treatment: PK15 porcine kidney cells are cultured in DMEM with 15% FBS and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [42].

Small Molecule Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of repair-modulating compounds:

- Repsox (TGF-β signaling inhibitor)

- Zidovudine (thymidine analog)

- GSK-J4 (histone demethylase inhibitor)

- IOX1 (histone demethylase inhibitor)

- YU238259 (HR inhibitor)

- GW843682X (PLK1 inhibitor) [42]

CRISPR Delivery and Compound Treatment:

- Deliver Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complexes via electroporation

- Add optimal concentrations of small molecules post-electroporation

- Incubate for 48-72 hours before analysis [42]

Efficiency Assessment:

- Analyze gene editing efficiency by tracking indels via sequencing

- Compare treatment groups to untreated controls

- Repsox demonstrated the strongest effect, increasing NHEJ-mediated editing 3.16-fold [42]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Repair Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Systems | DSB-Spectrum [40], DR-GFP [40] | Simultaneous quantification of multiple DSB repair pathways | Cas9-induced DSBs, fluorescent readout, single-construct design |

| Repair Pathway Inhibitors | DNA-PKcs inhibitors [40], Repsox [42], YU238259 [42] | Selective modulation of specific repair pathways | Alters HR/NHEJ balance, enhances gene editing efficiency |

| Model Organisms | S. cerevisiae strains [4] | Genetic analysis of repair pathway choice | Well-characterized repair mutants, facile genetics |

| CRISPR Components | Cas9 protein [42], sgRNAs [42] | Targeted DSB induction | Specific genomic targeting, compatible with various delivery methods |

| Detection Reagents | Flow cytometry antibodies [40], Southern blot reagents [4] | Assessment of repair outcomes | Quantitative, specific, adaptable to various experimental systems |

The origin of DNA damage—whether endogenous or exogenous—profoundly influences the selection of appropriate repair pathways, with significant implications for genomic stability and cancer development. Endogenous damage typically engages high-fidelity repair mechanisms like BER and MMR to handle frequent but less complex lesions, while exogenous damage often requires more specialized pathways such as NER and DSB repair systems. The competitive relationship between homology-directed repair and non-homologous end joining represents a critical decision point in maintaining genomic integrity, particularly in response to double-strand breaks.

Advanced experimental systems including multi-pathway fluorescent reporters, yeast genetic assays, and small molecule screening platforms provide powerful tools to dissect the complex interplay between different repair mechanisms. Understanding how repair pathway choice is influenced by damage origin and cellular context offers promising opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other age-related diseases characterized by genomic instability.

Harnessing Repair Pathways: CRISPR-Cas9 Strategies for Research and Therapy

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genome engineering by functioning as a programmable nuclease that introduces precise double-strand breaks (DSBs) at targeted genomic locations. This system originates from a bacterial adaptive immune mechanism and comprises two fundamental components: a Cas9 nuclease and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [43]. The sgRNA, through its 20-nucleotide targeting sequence, directs Cas9 to complementary DNA sequences adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), which for the most commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) is the sequence 5'-NGG-3' [44] [43]. Upon binding, the Cas9 nuclease employs two distinct catalytic domains to cleave the DNA: the HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the sgRNA, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary strand [34].

The resulting DSB triggers the cell's endogenous DNA repair machinery, primarily through two competing pathways: the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and the precise homology-directed repair (HDR) [34] [18]. NHEJ directly ligates the broken DNA ends without a template, often introducing semi-random insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function [34]. In contrast, HDR uses a homologous DNA template—either a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor template—to repair the break accurately, enabling precise gene corrections or insertions [34] [18]. The efficiency and outcome of CRISPR-mediated editing are profoundly influenced by the choice of nuclease, the configuration of the DSB ends, and the cellular context, which collectively determine the balance between these repair pathways.

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Nucleases

The expanding CRISPR toolkit now includes various naturally occurring and engineered nucleases, each with distinct properties that make them suitable for specific applications. The following section provides a detailed comparison of their key characteristics, PAM requirements, and performance metrics.

Table 1: Comparison of Key CRISPR Nucleases and Their Properties

| Nuclease | Origin/Type | Size (aa) | PAM Requirement | DSB End Configuration | Key Advantages | Reported Editing Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 1,368 | 5'-NGG-3' | Blunt (can also produce staggered ends [44]) | Broadly applied, well-characterized | Varies by locus and cell type; ~35% of breaks are staggered [44] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | 1,053 | 5'-NNGRRT-3' | Blunt | Small size enables AAV delivery | Efficient indel generation in various cell types [43] |

| Cas12f1 | Type V-F | ~500-700 | 5'-TTTN-3' | Staggered | Ultra-compact size | 100% eradication of KPC-2/IMP-4 resistance genes in model [45] |

| Cas12i (hfCas12Max) | Engineered Type V | 1,080 | 5'-TN-3' | Staggered | High fidelity, broad targeting | Enhanced editing with reduced off-targets [43] |

| Cas3 | Type I Cascade | - | 5'-GAA-3' | Processive degradation | Large deletions, high eradication efficiency | Highest eradication efficiency against resistant plasmids [45] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison in Antibiotic Resistance Gene Eradication [45]

| Nuclease | Target Gene | Eradication Efficiency | Resensitization to Ampicillin | Blocking of Horizontal Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | KPC-2 | 100% | Yes | 99% |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | IMP-4 | 100% | Yes | 99% |

| CRISPR-Cas12f1 | KPC-2 | 100% | Yes | 99% |

| CRISPR-Cas12f1 | IMP-4 | 100% | Yes | 99% |

| CRISPR-Cas3 | KPC-2 | 100% | Yes | 99% |

| CRISPR-Cas3 | IMP-4 | 100% | Yes | 99% |

Quantitative PCR analysis revealed that despite similar eradication rates at the endpoint, CRISPR-Cas3 demonstrated higher eradication efficiency than both CRISPR-Cas9 and Cas12f1 systems, suggesting more potent activity against bacterial resistance genes [45]. This highlights how different nucleases can achieve similar qualitative outcomes but differ significantly in their quantitative efficiency.

Determinants of NHEJ vs. HDR Efficiency

The competition between NHEJ and HDR pathways is influenced by multiple factors. A groundbreaking study using BreakTag technology revealed that approximately 35% of SpCas9 DSBs are staggered (with overhangs) rather than blunt, and these staggered breaks are associated with more predictable repair outcomes, including precise single-nucleotide insertions [44]. The study also found that DNA:gRNA complementarity and the use of engineered Cas9 variants influence the type of incision, which in turn affects the repair outcome [44].

Cell cycle stage represents another critical determinant. HDR is strongly favored in the S and G2 phases because it relies on sister chromatids as templates, while NHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle [34] [18]. This presents a particular challenge for editing postmitotic cells like neurons, where HDR efficiency is notoriously low [34] [46]. Additionally, the spatial organization of the break and local chromatin accessibility can significantly impact which repair pathways are engaged and their relative efficiency.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

BreakTag Protocol for DSB Profiling

The BreakTag methodology represents a significant advancement for systematically profiling Cas9-induced DNA double-strand breaks genome-wide. This versatile protocol maps free DSB ends in genomic DNA digested by ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) in vitro through four streamlined steps [44]:

- End repair/A-tailing: Prepares the DSB ends for subsequent ligation.

- Adapter ligation: Ligates an adaptor containing a Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) for accurate DSB counting and a sample barcode for multiplexing.

- Tagmentation: Uses Tn5 transposase to fragment the DNA.

- PCR amplification: Amplifies ligated fragments to generate sequencing libraries.

This method efficiently enriches for DSBs containing single-stranded DNA overhangs, allowing off-target nomination of staggered-cleaving nucleases like Cas12a with the same protocol. When partnered with the BreakInspectoR bioinformatics pipeline, BreakTag enables precise identification and quantification of Cas9-induced DSBs, achieving excellent reproducibility across different gRNAs [44]. In benchmark comparisons, BreakTag showed an 85% overlap with GUIDE-seq nominated off-targets and correlated strongly with CHANGE-seq (Pearson r = 0.8862) [44].

HDR Efficiency Optimization Protocols

Several experimental strategies have been developed to enhance HDR efficiency for precise genome editing:

- NHEJ Pathway Inhibition: Chemical inhibition of key NHEJ proteins (e.g., Ku70/Ku80, DNA-PKcs) or using dominant-negative mutants can shift repair toward HDR [34].

- HDR Pathway Activation: Overexpression of HDR-related factors such as CtIP or RAD52 can stimulate homologous recombination [34].

- Donor Template Design: Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) generally provide higher HDR efficiency than double-stranded DNA templates for small insertions. Strategies like Easi-CRISPR use in vitro transcribed RNA templates converted to ssDNA via reverse transcriptase, increasing editing efficiency from 1-10% to 25-50% in mouse models [18]. The insertion site should be close to the DSB (ideally <10 bp), and the donor should disrupt the gRNA or PAM sequence to prevent re-cutting [18].

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: Artificially synchronizing cells in S/G2 phase when HDR is more active can improve precise editing rates [34].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nucleases | SpCas9, SaCas9, hfCas12Max, eSpOT-ON (ePsCas9) | Introduce targeted DSBs; engineered variants offer improved specificity or altered PAM requirements [43]. |

| Delivery Systems | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs), AAVs, Lentiviruses, LNP-SNAs | Transport CRISPR machinery into cells; LNP-SNAs show 3x improved entry and reduced toxicity [47]. |

| Donor Templates | ssODNs, dsDNA plasmids, Easi-CRISPR templates | Serve as homologous repair templates for HDR-mediated precise editing [18]. |

| DSB Profiling Tools | BreakTag libraries, BreakInspectoR pipeline | Systematically map genome-wide Cas9-induced DSBs and their end structures [44]. |

| gRNA Libraries | Second-generation genome-scale CRISPR libraries | Enable high-complexity fitness screens identifying core and context-dependent fitness genes [48]. |

| Specialized Systems | ORANGE toolbox, HITI method | Facilitate endogenous protein tagging in neurons via NHEJ-based knock-in strategies [46]. |

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Induced DNA Repair Pathways. This diagram illustrates the competing NHEJ and HDR pathways activated after CRISPR-Cas9 creates a double-strand break.

Advanced Delivery Systems

Recent innovations in delivery vehicles have significantly improved CRISPR efficacy. Northwestern University researchers developed lipid nanoparticle spherical nucleic acids (LNP-SNAs) that wrap CRISPR components in a protective DNA shell [47]. These structures demonstrated a threefold improvement in cell entry and gene-editing efficiency compared to standard LNPs, with a >60% increase in precise DNA repair success rates and markedly reduced cellular toxicity across various human cell types [47]. This structural approach to delivery optimization highlights how nanomaterial design can dramatically enhance functional outcomes in genome editing.

Diagram 2: BreakTag DSB Profiling Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in the BreakTag protocol for genome-wide mapping of Cas9-induced double-strand breaks.

The landscape of programmable nucleases for directing DNA breaks has expanded considerably beyond the foundational CRISPR-Cas9 system. The choice of nuclease—whether SpCas9, the compact SaCas9, the high-fidelity hfCas12Max, or the highly efficient Cas3—depends on specific experimental needs including PAM requirements, delivery constraints, and desired editing outcomes [45] [43]. The critical interplay between nuclease selection, DSB end structure, and cellular repair mechanisms determines the ultimate balance between error-prone NHEJ and precise HDR.

Advanced methodologies like BreakTag provide unprecedented resolution in mapping DSBs and understanding their structural features, revealing that approximately 35% of Cas9 breaks are staggered and associated with more predictable repair outcomes [44]. Concurrently, innovations in delivery platforms, particularly LNP-SNAs, demonstrate that structural engineering of nanoparticles can triple editing efficiency and significantly improve precision [47]. These technological advances, combined with optimized experimental protocols for enhancing HDR, are rapidly accelerating both basic research and therapeutic applications of programmable nucleases. The continued refinement of this toolkit promises to enhance the precision and safety of genome editing across diverse biological contexts and therapeutic domains.

Leveraging NHEJ for Efficient Gene Knockouts and Disruption

In the context of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing, the choice between Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) and Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is fundamental. While HDR and NHEJ are both critical DNA repair pathways, they serve distinct purposes in genetic engineering. HDR is a precise, template-dependent mechanism ideal for inserting specific sequences, such as point mutations or fluorescent tags [3] [11]. In contrast, NHEJ is an error-prone, template-independent pathway that directly ligates double-strand breaks (DSBs), often introducing small insertions or deletions (INDELs) [3] [49]. This inherent characteristic of NHEJ makes it the superior and most widely used mechanism for generating gene knockouts, as these INDELs can effectively disrupt the coding sequence of a target gene, leading to loss of function [3]. This guide objectively compares the efficiency of NHEJ against alternative pathways for gene disruption, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Pathway Mechanics: How NHEJ Mediates Gene Disruption

The process of NHEJ-mediated gene disruption begins when CRISPR/Cas9 induces a DNA double-strand break (DSB) at a targeted genomic locus. The cell's endogenous repair machinery is then activated to fix this break [3]. The NHEJ pathway operates through a series of coordinated steps to repair the break without a template, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Figure 1: The NHEJ Repair Pathway for Gene Knockout. This diagram outlines the key steps in the Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) mechanism, from initial double-strand break (DSB) induction by CRISPR/Cas9 to the formation of a disruptive INDEL mutation.

The core NHEJ factors include the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer, which acts as the initial DSB sensor, DNA-PKcs, and the ligation complex composed of XLF, XRCC4, and DNA Ligase 4 [49] [50]. The pathway is active throughout the cell cycle, giving it a significant temporal advantage over HDR, which is restricted to the S and G2 phases [49]. A key feature of NHEJ is its ability to join ends with minimal processing, but when processing does occur, it is often imperfect, leading to the small insertions or deletions (INDELs) that are the basis of gene knockouts [3] [49].

Quantitative Comparison: NHEJ Outcompetes HDR in Efficiency