Harnessing Synthetic Biology in Actinobacteria: Engineering Microbial Cell Factories for Novel Bioactive Compounds

This article explores the integration of synthetic biology with actinobacterial research to address the urgent need for novel bioactive compounds in an era of rising antimicrobial resistance.

Harnessing Synthetic Biology in Actinobacteria: Engineering Microbial Cell Factories for Novel Bioactive Compounds

Abstract

This article explores the integration of synthetic biology with actinobacterial research to address the urgent need for novel bioactive compounds in an era of rising antimicrobial resistance. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of how advanced genetic tools are being used to unlock the vast, untapped biosynthetic potential of actinobacteria. The scope spans from foundational concepts and genome mining strategies to sophisticated methodological applications for pathway engineering, combinatorial optimization techniques for troubleshooting production bottlenecks, and rigorous validation frameworks for comparative analysis. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this article serves as a strategic guide for leveraging synthetic biology to transform actinobacteria into powerful platforms for drug discovery and sustainable pharmaceutical production.

The Untapped Potential of Actinobacteria: A Treasure Trove for Novel Drug Discovery

Actinobacteria as Prolific Producers of Clinically Vital Natural Products

Actinobacteria, particularly those from the genus Streptomyces, represent one of the most fertile sources of bioactive natural products (NPs) with transformative impacts on modern medicine. These Gram-positive, high GC-content bacteria are renowned for their exceptional biosynthetic capabilities, producing approximately two-thirds of the clinically used antibiotics originating from this phylum [1] [2] [3]. Beyond antibiotics, actinobacterial metabolites encompass a remarkable spectrum of pharmacological activities, including anticancer, immunosuppressive, anti-parasitic, and antiviral agents [1] [3]. The genetic basis for this chemical diversity lies in their complex genomes, which harbor numerous biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) encoding the enzymatic machinery for secondary metabolite production. Notably, a single Streptomyces genome may contain 20–30 BGCs, far exceeding the number of compounds typically detected under standard laboratory conditions [4] [2]. This vast untapped potential, often referred to as the "great biosynthetic gene cluster anomaly," positions actinobacteria as a central focus for future drug discovery efforts, particularly through the application of synthetic biology approaches to access this hidden chemical wealth [5] [6].

Chemical Diversity and Clinical Significance of Actinobacterial Compounds

Structural Classes and Bioactive Potential

Actinobacteria produce an extensive array of structurally diverse natural products that can be categorized into several major chemical classes, each with distinct therapeutic applications. The table below summarizes the primary structural classes and their clinical significance.

Table 1: Major Structural Classes of Clinically Vital Natural Products from Actinobacteria

| Structural Class | Representative Compounds | Biological Activities | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quinones | Doxorubicin, Granaticin | Cytotoxic, Antitumor | Colorectal cancer, Various cancers |

| Lactones | Actinomycin, Lactonamycin | Antibacterial, Cytotoxic | Antibiotic, Anticancer therapy |

| Alkaloids | Staurosporine, Piericidins | Antifungal, Protein kinase inhibition | Precursor for synthetic kinase inhibitors |

| Peptides | Vancomycin, Daptomycin | Antibacterial (against MRSA, VRE) | Last-line antibiotics for resistant infections |

| Glycosides | Streptomycin, Neomycin | Antibacterial | Aminoglycoside antibiotics |

| Polyketides | Erythromycin, Tetracycline | Antibacterial, Antifungal | Macrolide and tetracycline antibiotics |

| Macrolides | Rapamycin, Tacrolimus | Immunosuppressive | Organ transplant rejection prevention |

Quantitative Significance in Drug Discovery

The contribution of actinobacteria to the pharmaceutical arsenal is substantial and quantifiable. Analysis of anti-colorectal cancer compounds alone reveals 232 natural products with demonstrated activity against this deadly disease, with the majority being quinones, lactones, alkaloids, peptides, and glycosides [1]. The Streptomyces genus stands as the predominant producer, generating over 76% of these anti-CRC compounds exclusively [1]. From an ecological distribution perspective, the majority of bioactive compounds are derived from marine actinobacteria (79.02%), followed by terrestrial and endophytic sources, highlighting the importance of exploring diverse ecosystems for bioprospecting [1].

Genomic Foundations of Biosynthetic Capability

Biosynthetic Gene Clusters: The Genetic Blueprint

The remarkable biosynthetic capacity of actinobacteria is encoded within their genomes in the form of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) – physically clustered groups of genes that collectively encode the pathway for a specialized metabolite [2] [7]. These BGCs typically include genes for core biosynthetic enzymes, regulatory proteins, resistance mechanisms, and transporters [2]. The most prominent classes of BGCs include:

- Polyketide Synthases (PKS): Large modular enzymes that assemble polyketide scaffolds through sequential decarboxylative Claisen condensations

- Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS): Multi-domain enzymes that assemble peptide products without ribosomal template

- Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-translationally Modified Peptides (RiPPs): Gene-encoded peptides that undergo extensive enzymatic modifications

- Terpene Synthases: Enzymes that cyclize isoprenoid precursors into diverse terpenoid skeletons

Table 2: Genomic Capacity for Natural Product Synthesis in Actinobacteria

| Actinobacterial Species | Genome Size (Mb) | Number of BGCs | Notable Natural Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces coelicolor | 8.7 | 18 | Actinorhodin, Undecylprodigiosin |

| Streptomyces avermitilis | 9.1 | 30 | Avermectin (antiparasitic) |

| Streptomyces clavuligerus | N/A | 58 | Cephamycin C, Clavulanic acid |

| Streptomyces bottropensis | N/A | 21 | Borrelidin, Bottromycins |

| Saccharomonospora sp. CNQ490 | N/A | 19 (unexplored) | Potential novel compounds |

The "Great Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Anomaly"

A fundamental paradox in actinobacterial natural product research is the discrepancy between the number of BGCs identified genomically and the number of compounds actually detected and characterized – a phenomenon termed the "great biosynthetic gene cluster anomaly" [5]. Genomic analyses have revealed that actinobacteria possess significantly more BGCs than previously identified through bioactivity screening. For instance, before genome sequencing, Streptomyces coelicolor was known to produce only four metabolites, while its sequenced genome revealed 18 BGCs [2]. This disparity arises because many BGCs remain "silent" or "cryptic" under standard laboratory culture conditions, only expressing under specific environmental triggers or genetic manipulations [8] [2].

Synthetic Biology Approaches for Natural Product Discovery and Optimization

Genome Mining and Bioinformatics Tools

The advent of inexpensive genome sequencing has revolutionized natural product discovery through genome mining – the bioinformatic identification and analysis of BGCs in genomic data. Several sophisticated bioinformatics platforms have been developed specifically for this purpose:

- antiSMASH: The most widely used tool for identifying and annotating BGCs in microbial genomes; can detect known BGC classes and predict novel ones [2]

- PRISM: Predicts chemical structures of ribosomally and non-ribosomally synthesized peptides and polyketides

- NaPDoS: Analyzes ketosynthase and condensation domains from PKS and NRPS systems to determine phylogenetic relationships

- MultiGeneBlast: Allows comparison of identified BGCs against databases of known gene clusters

These tools have enabled the discovery of numerous novel compounds, including streptoketides from Streptomyces sp. Tu6314, atratumycin from S. atratus, and nybomycin from S. albus [2].

Activation of Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

A major focus of contemporary research involves developing strategies to activate cryptic BGCs to access their encoded compounds:

- Promoter Engineering: Replacement of native promoters with strong, constitutive promoters to drive expression of silent BGCs [4]

- Transcription Factor Overexpression: Introduction of extra copies of pathway-specific activators or deletion of repressors

- Ribosome Engineering: Introduction of specific antibiotic resistance mutations that pleiotropically enhance secondary metabolism

- Co-cultivation: Simulating ecological interactions by growing actinobacteria with other microorganisms to trigger defense responses

- Epigenetic Manipulation: Use of small molecule modifiers such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors to alter chromatin structure and gene expression [8]

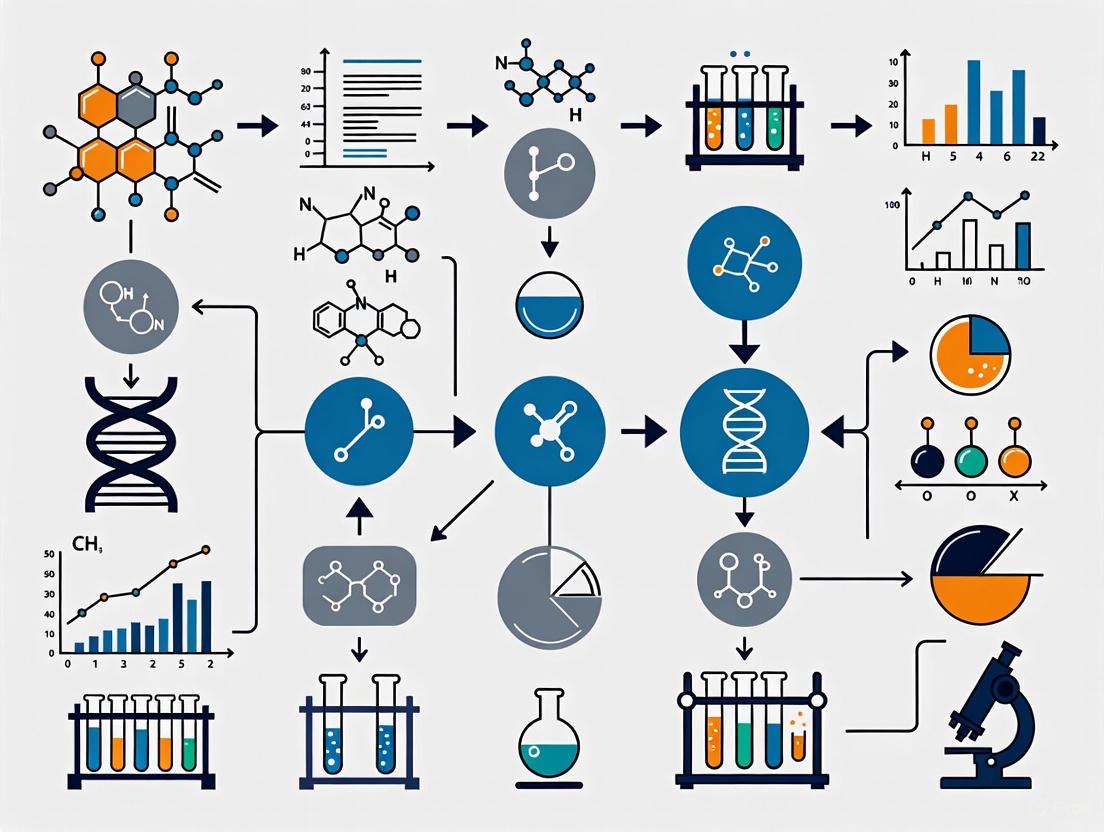

Diagram 1: Strategies for Activating Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

Heterologous Expression and Chassis Development

Due to the genetic intractability and slow growth of many actinobacteria, especially rare genera, heterologous expression in engineered host strains has become a cornerstone strategy. This involves cloning entire BGCs and transferring them into well-characterized, genetically amenable host strains. Key developments include:

- Construction of Genome-Minimized Chassis: Creation of simplified Streptomyces strains with deleted endogenous BGCs to reduce background interference and redirect metabolic flux [4] [6]

- BGC Refactoring: Complete redesign of natural BGCs by replacing all native regulatory elements with synthetic counterparts for optimized expression [4] [6]

- Vector Systems Development: Creation of specialized plasmids (BAC, cosmic, artificial chromosome) for capturing and expressing large BGCs

Notably, researchers have developed cluster-free Streptomyces albus chassis strains that allow improved heterologous expression of secondary metabolite clusters with reduced background [6].

Metabolic Engineering and Pathway Optimization

Once a BGC is expressed, synthetic biology approaches can further optimize production titers for commercially viable manufacturing:

- Precursor Engineering: Amplifying the supply of essential biosynthetic building blocks through overexpression of precursor biosynthesis genes

- Dynamic Metabolic Regulation: Implementing metabolite-responsive promoters or biosensors that autonomously balance bacterial growth and compound biosynthesis [4]

- BGC Amplification: Introducing multiple copies of the target BGC into the production host to enhance gene dosage [4]

A notable example of dynamic regulation involves the use of antibiotic-responsive promoters identified through time-course transcriptome analysis. When applied to oxytetracycline biosynthesis, this approach resulted in a 9.1-fold production increase compared to constitutive promoters [4].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Genome Mining and BGC Identification Protocol

Objective: Identify and annotate biosynthetic gene clusters in actinobacterial genomes.

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

- Sequence actinobacterial genome using Illumina NovaSeq and PacBio platforms for hybrid assembly

- Assemble reads into contigs using dedicated assemblers (SPAdes, Unicycler)

- Annotate genome using Prokka or RAST toolkit

BGC Detection and Analysis

- Submit annotated genome to antiSMASH webserver (latest version)

- Select all analysis options including NRPS/PKS, terpene, RiPP, and secondary metabolite detection

- Download results and examine identified BGCs with known clusters in MIBiG database

Comparative Genomic Analysis

- Use MultiGeneBlast to compare identified BGCs against custom database of known clusters

- Analyze key enzymes (PKS KS domains, NRPS C domains) using NaPDoS for phylogenetic placement

- Predict chemical structures of encoded metabolites using PRISM

Priority Assessment

- Rank BGCs based on novelty (similarity to known clusters), complexity, and presence of unusual biosynthetic features

- Select highest priority targets for experimental activation

BGC Refactoring and Heterologous Expression Protocol

Objective: Refactor a targeted BGC for expression in a heterologous host.

BGC Capture

- Isolate high molecular weight genomic DNA from donor actinobacterium

- Partially digest with appropriate restriction enzyme and size-fractionate by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

- Clone large fragments (>50 kb) into BAC or cosmic vector

- Screen library by PCR targeting specific BGC genes

BGC Refactoring

- Identify all native regulatory elements within BGC (promoters, RBS, transcriptional terminators)

- Design synthetic replacement parts: strong constitutive promoters, optimized RBS, orthogonal terminators

- Use isothermal assembly or CRISPR/Cas9 to systematically replace all regulatory elements

- Verify refactored sequence by whole-plasmid sequencing

Heterologous Expression

- Introduce refactored BGC into optimized Streptomyces chassis (e.g., S. albus J1074) via intergeneric conjugation

- Plate exconjugants on appropriate selection media and verify successful transfer by PCR

- Inoculate production media and culture with optimized parameters (temperature, aeration, media composition)

Metabolite Analysis

- Extract culture broth with organic solvents (ethyl acetate, butanol)

- Analyze extracts by LC-HRMS for detection of new ions not present in control strains

- Scale up production of target compound for purification and structural elucidation (NMR)

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for BGC Refactoring and Expression

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Actinobacteria Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | Bioinformatics tool for BGC identification and analysis | Detects known BGC classes; predicts novel clusters; available as web server or standalone package |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Genome editing; BGC deletion; promoter replacements | Streptomyces-optimized Cas9 expression vectors; sgRNA templates for specific targeting |

| Actinobacterial Artificial Chromosomes | Cloning and maintenance of large BGCs | pCC1BAC, pESAC13; capacity for >100 kb inserts; inducible copy number control |

| Genome-Minimized Chassis Strains | Clean background hosts for heterologous expression | S. albus J1074 delBGC; S. coelicolor M1152/M1154; multiple endogenous clusters deleted |

| Metabolite-Responsive Promoters | Dynamic pathway regulation; biosensor construction | Antibiotic-inducible promoters; pathway-specific regulator-based systems |

| Specialized Actinobacteria Media | Cultivation; secondary metabolite production; conjugation | R2YE, SFM, ISP media; optimized for growth and genetic manipulation |

| Gateway/Type IIS Assembly Systems | Modular genetic parts assembly; pathway refactoring | pSET152, pIJ10257 vectors; Golden Gate toolkit for Streptomyces |

| HPLC-HRMS Systems | Metabolite detection and analysis | UHPLC coupled to Q-TOF mass spectrometer; high resolution for compound identification |

| 1-Hydroxypregnacalciferol | 1-Hydroxypregnacalciferol|CAS 58702-12-8 | 1-Hydroxypregnacalciferol is a vitamin D analog for research in oncology and dermatology. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| Bicyclo[3.3.2]dec-1-ene | Bicyclo[3.3.2]dec-1-ene | Bicyclo[3.3.2]dec-1-ene (C10H16) is a bridged bicyclic alkene for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The convergence of genomics, synthetic biology, and metabolic engineering has positioned actinobacteria research at the forefront of next-generation drug discovery. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and become more accessible, the catalog of characterized BGCs will expand exponentially, providing an ever-growing reservoir of potential therapeutic leads. Future developments will likely focus on increasingly sophisticated heterologous expression platforms capable of producing complex natural products from unculturable organisms, machine learning approaches for predicting BGC function and chemical structures from sequence data, and integrated automation to enable high-throughput screening and optimization of actinobacterial strains and their metabolites.

The application of synthetic biology principles to actinobacterial natural product discovery represents a paradigm shift from traditional bioactivity-guided isolation to genome-guided compound discovery and engineering. By viewing actinobacteria as programmable chassis for natural product production rather than simply as sources of compounds, researchers can overcome the limitations of traditional methods and access the vast untapped chemical potential encoded within actinobacterial genomes. This approach promises to replenish the depleted pipeline of novel antibiotics and other therapeutics needed to address emerging global health challenges, particularly the escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance. As these technologies mature, actinobacteria will undoubtedly continue their indispensable role as nature's premier chemists, providing clinically vital natural products for decades to come.

Genome Mining Reveals a Vast Reservoir of Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), responsible for millions of deaths annually, underscores the urgent need for novel therapeutic agents [9] [8]. Actinobacteria, particularly members of the genus Streptomyces, have for decades been prolific producers of bioactive natural products (NPs) that form the cornerstone of our antimicrobial arsenal [2] [7]. However, traditional bioactivity-guided screening methods have led to frequent compound re-discovery, significantly slowing the pace of novel antibiotic development [10].

The advent of affordable genome sequencing has revolutionized natural product discovery, revealing a profound disparity between the number of known metabolites a bacterium produces and its inherent genetic potential. Genomic analyses have uncovered that actinobacterial genomes are replete with biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs)—groups of co-localized genes encoding the machinery for specialized metabolite production [2] [11]. Astonishingly, it is estimated that only approximately 10% of these BGCs are expressed under standard laboratory conditions; the remaining majority are "silent" or "cryptic," representing a massive untapped reservoir of novel chemical entities [9] [8]. This hidden treasure trove, now accessible through genome mining, positions synthetic biology and advanced genetic engineering as pivotal disciplines for activating these silent clusters and replenishing the depleted pipeline of effective antibiotics [4] [11].

The Scale and Diversity of Silent BGCs in Actinobacteria

Actinobacteria possess some of the largest bacterial genomes, ranging from 6 to 12 Mb in Streptomyces species, reflecting their complex metabolic capabilities [2]. These genomes are packed with a remarkable density of BGCs. For instance, the model organism Streptomyces coelicolor, once thought to produce only four secondary metabolites, was found to harbor 18 BGCs after its genome was sequenced [2]. Similarly, Streptomyces clavuligerus possesses 58 BGCs, and S. avermitilis contains 30 [2]. A broader analysis of 39 streptomycete genomes identified 1,346 BGCs, highlighting the immense, largely unexplored biosynthetic potential within this single genus [2].

The diversity of silent BGCs extends beyond the well-studied Streptomyces. So-called "rare" actinobacteria (non-streptomycetes) belonging to genera such as Micromonospora, Nocardia, and Actinomadura have been increasingly recognized as sources of unique antibiotics [2]. For example, the draft genome of Saccharomonospora sp. CNQ490 revealed 19 unexplored BGCs [2]. Furthermore, bioprospecting in extreme environments like the deep sea has yielded novel actinobacterial species and compounds, with 24 new species and 101 new compounds reported from deep-sea environments between 2016 and 2022 alone [7]. These findings underscore that the reservoir of silent BGCs is not only vast but also highly diverse, offering prospects for discovering compounds with unprecedented structures and modes of action.

Table 1: Examples of BGC Abundance in Actinobacteria

| Organism | Number of BGCs | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces coelicolor | 18 | Genome sequencing revealed ~4.5x more BGCs than previously known from biochemical studies [2]. |

| Streptomyces clavuligerus | 58 | Illustrates the high density of BGCs in some species [2]. |

| Saccharomonospora sp. CNQ490 | 19 | Example of the unexplored potential in rare actinobacteria [2]. |

| General Streptomyces | 20-30 BGCs per genome | The prokaryotic genus with the greatest number of BGCs per genome; prolific producers of clinical antibiotics [2] [4]. |

Bioinformatics Tools for Genome Mining and BGC Identification

The first critical step in tapping into the reservoir of silent BGCs is their identification and preliminary characterization, a process known as genome mining. This relies on sophisticated bioinformatics tools that can scan microbial genomes for signature sequences of BGCs [10].

antiSMASH: The Central Tool for BGC Detection

The Antibiotics and Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell (antiSMASH) is the most widely used platform for BGC identification [2] [12] [10]. This tool detects and annotates BGCs in genomic data by comparing them against a curated database of known clusters. AntiSMASH can identify a wide range of BGC types, including those for polyketide synthases (PKS), non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), terpenes, and siderophores [12] [7]. Its integrated analyses, such as KnownClusterBlast and ClusterBlast, allow researchers to quickly assess the novelty of identified BGCs by comparing them with clusters of known function [12].

Complementary Bioinformatics Tools

Beyond antiSMASH, a suite of other tools provides specialized functionalities:

- PRISM: Predicts the chemical structures of secondary metabolites encoded by NRPS and PKS clusters, offering insights into potential novel compounds [2] [11].

- NaPDoS (Natural Product Domain Seeker): Helps identify and classify ketosynthase (KS) and condensation (C) domains from PKS and NRPS gene clusters, providing phylogenetic insights into BGC evolution and function [2].

- BiG-SCAPE (Biosynthetic Gene Similarity Clustering and Prospecting Engine): Analyzes the sequence similarity of BGCs to group them into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs), aiding in the prioritization of clusters for experimental work based on novelty [12].

- MultiGeneBlast: Facilitates the identification of BGCs within genomic databases by allowing users to search with a query gene cluster [2].

These tools collectively have enabled the discovery of novel bioactive compounds such as humidimycin, atratumycin, and nybomycin directly through genome mining efforts [2].

Synthetic Biology Strategies for Activating Silent BGCs

Identifying silent BGCs is only the beginning. The central challenge lies in activating their expression. Synthetic biology has developed a powerful arsenal of strategies to perturb the native regulation of actinobacteria and elicit the production of cryptic metabolites.

Multi-Pronged Genetic Activation

A highly robust, flexible, and efficient strategy involves the stable integration of global regulatory "activator" genes into the actinobacterial chromosome using the phiC31 integrase system [13]. This approach, demonstrated across 54 diverse actinobacterial strains, involves constitutively expressing a library of key regulatory genes:

- Global Regulators (Crp, *AdpA, SarA):* Modulate the balance between primary and secondary metabolism, sporulation, and morphological differentiation, creating a physiological state more permissive for antibiotic production [13].

- Pathway-Specific Activators (e.g., SARP family like RedD): Directly bind to and activate the promoters of specific BGCs [4] [13].

- Metabolic Flux Enhancers (e.g., Fatty Acyl CoA Synthase, FAS): Mobilize precursor pools, such as triacylglycerols, to increase the flux of building blocks toward secondary metabolite biosynthesis [13].

This multi-pronged activation strategy has proven remarkably effective, nearly doubling the accessible metabolite space and increasing the yield of selected metabolites by over 200-fold in some cases [13]. The workflow for this approach is detailed in the diagram below.

Dynamic Metabolic Regulation

Static overexpression of activators can be suboptimal, as it may impose a metabolic burden or be toxic. Dynamic regulation strategies autonomously control pathway flux in response to cellular metabolites [4].

- Metabolite-Responsive Promoters: These native promoters are activated by intermediates or end-products of a biosynthetic pathway. For example, the actAB promoter in S. coelicolor is induced by actinorhodin and its intermediates, creating a positive feedback loop that synergistically regulates biosynthesis and export [4]. Employing such promoters to drive the expression of key pathway genes has improved antibiotic titers significantly compared to constitutive promoters [4].

- Biosensor-Mediated Screening: Native transcriptional regulators (e.g., TetR-like repressors) that respond to a target antibiotic can be engineered into whole-cell biosensors [4]. By linking the biosensor to a reporter gene (e.g., antibiotic resistance), this system allows for high-throughput screening of mutant libraries. Mutants that hyper-produce the antibiotic can be easily selected based on their resistance phenotype, facilitating the development of overproducing strains without prior knowledge of the cluster's regulation [4].

Cluster-Specific Refactoring and Heterologous Expression

For BGCs that remain stubbornly silent or are found in hard-to-manipulate native hosts, refactoring and heterologous expression provide a powerful alternative.

- BGC Refactoring: This involves the systematic replacement of native regulatory elements and promoters in the BGC with well-characterized, synthetic counterparts to ensure strong and predictable expression in a heterologous host [4] [11].

- Heterologous Expression: The refactored BGC is then cloned and transferred into a genetically tractable "platform" host, such as Streptomyces coelicolor or engineered strains of S. albus [4] [11]. This approach not only activates the cluster but also decouples its expression from the native regulatory network of the original strain.

Table 2: Synthetic Biology Strategies for BGC Activation

| Strategy | Key Feature | Example/Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Pronged Genetic Activation [13] | Integration of global and pathway-specific regulators via phiC31 integrase. | ~2-fold expansion in metabolite space; up to >200-fold yield increase for specific compounds. |

| Dynamic Regulation [4] | Uses native metabolite-responsive promoters or biosensors for autonomous control. | 9.1-fold improvement in oxytetracycline titer in S. coelicolor. |

| BGC Refactoring & Heterologous Expression [4] [11] | Replacement of native regulatory parts and expression in a tractable surrogate host. | Successful production of cryptic metabolites from various actinobacteria in standardized chassis. |

| CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing [9] [13] | Enables precise deletion, insertion, and point mutations to manipulate BGCs and their regulators. | Facilitates cluster activation, deletion of competing pathways, and generation of knock-out mutants for functional studies. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Activation and Discovery

To translate strategic concepts into laboratory practice, detailed and reliable protocols are essential. Below is a synthesis of key methodologies from recent studies.

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a library of activated actinobacterial strains.

Library Plasmid Construction:

- Vector: Use a phiC31 integration vector (e.g., pSET152).

- Cloning: Amplify candidate "activator" genes (e.g., crp, adpA, sarA, redD, FAS). Clone each gene individually into the vector under the control of a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., kasOp).

- Validation: Sequence the constructed plasmids to confirm integrity.

Bacterial Conjugation and Genomic Integration:

- Preparation: Grow the E. coli donor strain (e.g., ET12567/pUZ8002) carrying the library plasmid and the actinobacterial recipient strain to mid-exponential phase.

- Conjugation: Mix donor and recipient cells, plate on appropriate medium, and incubate to allow conjugation.

- Selection: After ~16-20 hours, overlay the plates with antibiotics selective for the integration plasmid and counter-selective against the E. coli donor (e.g., nalidixic acid).

- Isolation: Incubate until exconjugants appear (typically 3-7 days). Pick and purify multiple exconjugants for each strain-activator combination.

Metabolite Profiling and Analysis:

- Fermentation: Inoculate each mutant and the wild-type strain into 3-5 different liquid media known to support diverse secondary metabolism (e.g., R5, SFM, CA07LB). Incubate with shaking for an appropriate period.

- Extraction: Harvest the culture. Extract metabolites from both the broth and the mycelium using a suitable organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze all extracts using Liquid Chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry.

- Molecular Networking: Process the LC-MS/MS data with the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform to visualize the chemical diversity and identify new metabolites that are upregulated or unique to the activated strains.

This protocol uses a biosensor to screen for hyper-producing mutants.

Biosensor Engineering:

- Identify Components: Locate a gene encoding a transporter and its cognate transcriptional repressor (e.g., a TetR-family regulator) within the target BGC.

- Construct Reporter: Place a reporter gene (e.g., for kanamycin resistance) under the control of the promoter regulated by this repressor.

- Optimization: If the native biosensor has a limited dynamic range, engineer the repressor protein through mutagenesis to alter its ligand-binding affinity.

Mutant Library Generation and Screening:

- Mutagenesis: Subject the native actinobacterial strain to random mutagenesis (e.g., using UV light or chemical mutagens).

- Selection: Plate the mutagenized culture on medium containing a high concentration of the antibiotic linked to the reporter (e.g., kanamycin).

- Isolation: Only mutants that produce sufficient amounts of the target natural product to inactivate the repressor and confer resistance will grow. Isolate these resistant colonies.

Validation and Scale-Up:

- Fermentation: Ferment the selected mutants and quantify the target compound production (e.g., via HPLC or bioassay) to confirm the hyper-producing phenotype.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

The experimental workflows described rely on a core set of genetic, bioinformatic, and analytical tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BGC Activation

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Platforms | Identification, annotation, and comparative analysis of BGCs in genomic data. | antiSMASH [2] [12] [10], PRISM [2] [11], BiG-SCAPE [12], NaPDoS [2] |

| Genetic Engineering Systems | Stable integration of DNA into the actinobacterial chromosome for introducing activators or refactored clusters. | PhiC31 integrase system (pSET152 vector) [13], CRISPR-Cas systems (pCRISPomyces-2) [9] [13] |

| Regulatory "Activator" Genes | Key genetic parts for perturbing global and pathway-specific regulation to awaken silent BGCs. | crp, adpA, sarA (global regulators) [13]; SARP genes like redD (pathway-specific) [4] [13] |

| Heterologous Hosts | Genetically tractable chassis for expressing refactored BGCs from recalcitrant or slow-growing native producers. | Streptomyces coelicolor, Streptomyces albus, genome-minimized Streptomyces strains [4] [11] |

| Analytical & Screening Platforms | Detection, identification, and quantification of newly produced metabolites from activated strains. | LC-MS/MS, GNPS (Global Natural Products Social) Molecular Networking [13], Biosensor-based screening [4] |

| Chromium chromate (H2CrO4) | Chromium chromate (H2CrO4), CAS:41261-95-4, MF:Cr2O4, MW:167.99 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Ethoxy-2-heptanone | 1-Ethoxy-2-heptanone (CAS 51149-70-3)|High Purity |

Genome mining has unequivocally revealed that actinobacteria possess a vast, genetically encoded reservoir of silent biosynthetic gene clusters, far exceeding the number of compounds we have identified through traditional means. This hidden potential represents a unparalleled opportunity to address the pressing global challenge of antimicrobial resistance. The path forward is clear: the disciplined application of synthetic biology—through multi-pronged genetic activation, dynamic regulation, and heterologous expression—provides a robust and generalizable toolkit to perturb, activate, and characterize these cryptic clusters. By systematically converting genetic potential into chemical reality, researchers can unlock nature's full chemical repertoire, paving the way for a new generation of therapeutic agents and reaffirming the critical role of actinobacteria in drug discovery.

The phylum Actinomycetota represents one of the largest and most diverse groups of bacteria, renowned for their extraordinary capacity to produce bioactive secondary metabolites. Historically, the genus Streptomyces has been the predominant source of clinically useful antibiotics, contributing approximately 80% of all known microbial bioactive compounds [3]. However, the repeated rediscovery of known compounds from common Streptomyces species has significantly diminished the efficiency of traditional biodiscovery pipelines [14] [15]. This challenge has catalyzed a paradigm shift toward exploring rare actinomycetes—defined as actinobacteria within the order Actinomycetales but not belonging to the genus Streptomyces—and extremophilic actinobacteria from unique ecological niches [14].

These underexplored taxa represent a promising frontier for novel compound discovery. Rare actinobacteria exhibit considerable biosynthetic and chemical diversity, while extremophilic actinobacteria have evolved unique adaptations to thrive in harsh conditions, including hot springs, deep-sea sediments, polar regions, and hypersaline environments [3] [16]. Their specialized metabolic pathways, shaped by extreme selective pressures, often yield structurally novel compounds with potent biological activities. Furthermore, advances in omics technologies have revolutionized our ability to access their biosynthetic potential, revealing that these organisms harbor a wealth of cryptic gene clusters that remain silent under standard laboratory conditions [15]. This technical guide, framed within the context of synthetic biology applications for novel compound research, provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to exploit these remarkable microorganisms.

Biodiversity and Ecological Adaptations of Underexplored Actinobacteria

Rare Actinobacteria from Diverse Habitats

Rare actinobacteria are ubiquitously distributed across both conventional and extreme environments, though they are often overshadowed by Streptomyces in standard isolation practices. Systematic exploration has revealed their significant presence in marine ecosystems, plant tissues as endophytes, and various terrestrial habitats. Unlike their Streptomyces counterparts, many rare actinobacteria possess specific physiological and metabolic traits that enable them to occupy specialized ecological niches [14] [17].

Endophytic actinobacteria, which reside within plant tissues without causing disease, represent a particularly promising source of novel chemistry. These symbionts have been isolated from plants in extreme habitats, including arid zones, mangroves, and saline ecosystems. Studies suggest that the genome sizes of endophytic microbes are often smaller than those of free-living relatives, with fewer mobile genetic elements contributing to genome stability and potentially favoring symbiotic associations [17]. This relationship offers mutual benefits: the host plant provides nutrients and shelter, while the endophyte produces phytohormones and offers protection against pathogens and abiotic stresses [17].

Extremophilic Actinobacteria and Their Survival Strategies

Extremophilic actinobacteria thrive in environments characterized by physical or chemical extremes, such as temperature, pH, salinity, or pressure. Their survival depends on sophisticated biochemical adaptations, which often involve the production of specialized metabolites and enzymes [3].

Table 1: Types of Extremophilic Actinobacteria and Their Habitats

| Extremophile Type | Defining Condition | Example Habitats | Representative Genera |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophile | High temperature (>50°C) | Hot springs, geothermal soils | Thermoactinospora, Thermocatellispora, Nocardiopsis |

| Psychrophile | Low temperature (<15°C) | Polar regions, glaciers, deep sea | Arthrobacter, Rhodococcus, Pseudonocardia |

| Halophile | High salinity | Salt lakes, saline soils, salt marshes | Saccharopolyspora, Nocardiopsis, Actinopolyspora |

| Acidophile | Low pH (<5) | Acid mine drainage, volcanic soils | Acidimicrobium, Acidithermus |

| Alkaliphile | High pH (>9) | Soda lakes, alkaline soils | Saccharomonospora, Nocardiopsis |

| Barophile (Piezophile) | High pressure | Deep-sea sediments, oceanic trenches | Dermacoccus, Microbacterium |

The adaptive strategies of these organisms are remarkably diverse. Thermophiles, isolated from hot spring sediments with temperatures ranging from 62°C to 99°C, produce thermostable polymer-degrading enzymes and heat-shock proteins that prevent aggregation under thermal stress [3]. In contrast, psychrophiles from cold environments synthesize antifreeze proteins and cold-active enzymes, maintaining membrane fluidity at low temperatures through increased unsaturated fatty acids [18]. Halophiles accumulate compatible solutes like ectoine to maintain osmotic balance in high-salt environments, a trait confirmed through genomic analysis of saline-adapted strains [16]. A study of 667 actinomycete isolates from extreme habitats in Kazakhstan found that a significant proportion (one-fifth) of antagonistic isolates produced active antimicrobial substances exclusively under extreme growth conditions, underscoring the critical link between their adaptation and metabolic expression [16].

Bioactive Compounds and Therapeutic Potential

Clinically Relevant Metabolites from Rare and Extremophilic Actinobacteria

The biosynthetic potential of non-Streptomyces actinobacteria is immense, yielding compounds with diverse chemical scaffolds and mechanisms of action. Historically, rare actinobacteria have contributed several clinically important drugs, including the aminoglycoside gentamicin from Micromonospora and the rifamycin group from Amycolatopsis, which are essential for treating tuberculosis and other bacterial infections [14] [19].

Recent biodiscovery efforts have significantly expanded the catalog of bioactive compounds. For instance, psychrophilic actinobacteria have yielded nine new compounds reported between 2017 and 2025, showcasing unique structural features evolved in cold environments [18]. Similarly, marine rare actinobacteria are a rich source of chemotherapeutic agents; indolocarbazoles such as staurosporine and rebeccamycin, produced by various marine actinomycetes, act as potent inhibitors of kinases and DNA topoisomerase I, demonstrating significant anticancer potential [20]. Furthermore, the rufomycin/ilamycin class of compounds from marine Streptomyces strains has exhibited exceptional activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) in the submicromolar range, making them promising candidates for anti-tuberculosis drug development [19].

Table 2: Selected Bioactive Compounds from Rare and Extremophilic Actinobacteria

| Compound/Class | Producing Organism | Source/Habitat | Biological Activity | Potential Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steffimycins | Streptomyces steffisburgensis | Terrestrial soil | Antimycobacterial (sub-µM MIC) | Tuberculosis treatment |

| Ilamycins/Rufomycins | Streptomyces spp. | Marine sediment | Anti-TB, targets MDR strains | Drug-resistant TB therapy |

| Lassomycin | Lentzea sp. | Soil | Bactericidal against M. tuberculosis | Anti-TB drug lead |

| Boromycin | Streptomyces sp. | Soil | Antimycobacterial, antiviral | TB treatment, antiviral therapy |

| Indolocarbazoles | Various Marine Actinomycetes | Marine sponge | Kinase & Topoisomerase I inhibition | Anticancer agents |

| Filipin-type Polyenes | Streptomyces antibioticus | Deep-sea sediment | Antifungal against Candida albicans | Antifungal treatment |

| Goadsporin | Streptomyces sp. | Soil | Ribosomally synthesized peptide | Antibiotic, inducer of differentiation |

Activation of Cryptic Biosynthetic Pathways

A significant challenge in natural product discovery is that many biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) remain "silent" or poorly expressed under standard laboratory conditions. Innovative strategies are being developed to activate these cryptic pathways. One powerful approach is microbial co-culture, which mimics natural ecological interactions. For example, the combined culture of actinomycetes with mycolic acid-containing bacteria has led to the discovery of 42 novel compounds that are not produced in axenic cultures [20]. Genetic and physiological analyses indicate that physical contact, rather than diffusible signals, is often essential for this induction, suggesting that direct cell-surface interactions trigger the activation of specific regulatory mechanisms [20].

Other strategies include the use of small-molecule elicitors, manipulation of culture conditions (e.g., varying medium composition, pH, or temperature), and the application of ribosomal engineering to perturb cellular regulation and awaken silent BGCs [15]. These methods collectively provide a robust toolkit for accessing the hidden chemical diversity encoded in the genomes of rare and extremophilic actinobacteria.

Omics Technologies for Biodiscovery and Synthetic Biology

Genome Mining and Metagenomics

The integration of omics technologies has transformed the field of microbial natural product discovery, enabling researchers to move from traditional bioassay-guided isolation to a more predictive, gene-based approach [15]. Genome sequencing of actinobacteria has consistently revealed a vast untapped biosynthetic potential, with the number of BGCs far exceeding the number of known compounds from any given organism. For instance, genome analysis of the marine-derived Streptomyces poriferorum, isolated from a sponge, revealed 41 BGCs, many of which are likely responsible for novel compounds, including those with activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [15].

Several bioinformatic tools and databases have been developed specifically for the detection and analysis of BGCs, including:

- antiSMASH: For automated identification and annotation of BGCs.

- PRISM: Predicts the chemical structures of secondary metabolites from genomic data.

- MIBiG: A repository for standardized structural and functional data on BGCs.

- DeepBGC: Employs machine learning to identify BGCs in genomic sequences [15].

Metagenomics offers a complementary, culture-independent strategy by directly analyzing the genetic material recovered from environmental samples. This approach is particularly valuable for studying uncultivable actinobacteria. For example, metagenomic analysis of hydrothermal sediments led to the reconstruction of 134 high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from the UBA5794 group, an uncultured order within the class Acidimicrobiia [21]. These MAGs provided insights into the metabolic versatility and heavy metal detoxification capacities of these elusive bacteria, highlighting their potential for biotechnological applications [21].

Diagram 1: Genomics-Driven Workflow for Natural Product Discovery. This pipeline illustrates the process from environmental sample collection to bioactivity testing, highlighting key computational and experimental stages.

Heterologous Expression and Synthetic Biology

A major bottleneck in natural product discovery is that many BGCs from rare or extremophilic actinobacteria are not expressed in their native hosts under laboratory conditions. Heterologous expression provides a powerful solution by transferring these BGCs into well-characterized, genetically tractable host strains, such as Streptomyces coelicolor or S. lividans [15]. This approach requires specialized techniques:

- Cosmid/Fosmid Library Construction: To capture large DNA fragments containing the entire BGC.

- Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR): A yeast-based method for direct cloning and refactoring of large BGCs.

- CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing: For precise manipulation of BGCs in the native or heterologous host.

Furthermore, synthetic biology strategies are being employed to refactor and optimize the expression of cryptic BGCs. This may involve replacing native promoters with strong, inducible counterparts, optimizing codon usage, and balancing the expression of pathway-specific regulatory genes to maximize metabolite production [15].

Experimental Protocols for Isolation and Characterization

Selective Isolation of Rare and Extremophilic Actinobacteria

Protocol 1: Sample Pre-treatment and Selective Isolation

- Sample Collection: Aseptically collect environmental samples (soil, sediment, plant tissue). For extreme environments, maintain in-situ conditions during transport using coolers or thermal containers.

- Sample Pre-treatment:

- Air-drying: Spread sample on sterile petri dishes and air-dry at room temperature for 30 minutes to 1 hour to reduce Gram-negative bacteria.

- Heat treatment: Suspend sample in sterile saline and incubate at 45°C (for moderate thermophiles) or 55-60°C (for strict thermophiles) for 10-20 minutes.

- Chemical treatment: Use 1.5% phenol for 10 minutes or chloramine-B (2 mg/mL) for 30 minutes to select for resistant actinobacteria.

- Selective Media and Incubation:

- Use oligotrophic media such as Humic Acid-Vitamin (HV) agar or Starch-Casein Agar for general isolation.

- For halophiles, supplement media with 5-20% NaCl or artificial seawater.

- For acidophiles/alkaliphiles, adjust media pH to 4.5-5.5 or 9.0-10.5, respectively, using appropriate buffers.

- Add selective antibiotics (e.g., nalidixic acid 20 µg/mL, nystatin 50 µg/mL, cycloheximide 50 µg/mL) to suppress fungi and fast-growing bacteria.

- Incolate plates at appropriate temperatures (4-10°C for psychrophiles, 50-60°C for thermophiles) for 2-8 weeks.

Protocol 2: Enrichment Strategies for Endophytic Actinobacteria

- Surface Sterilization of Plant Material:

- Rinse plant tissue (roots, stems) in running tap water.

- Immerse sequentially in: 70% ethanol (1-2 min), sodium hypochlorite (2-3.5% available chlorine, 3-5 min), 70% ethanol (30 sec).

- Rinse thoroughly 3-5 times with sterile distilled water.

- Validate surface sterilization by imprinting the tissue on nutrient agar.

- Isolation:

- Grind sterilized tissue in sterile phosphate buffer.

- Serially dilute and spread on selective media as described in Protocol 1.

- Alternatively, place small tissue fragments directly on the agar surface.

Screening for Bioactive Metabolites and Eliciting Cryptic Pathways

Protocol 3: Co-culture for Activation of Cryptic BGCs

- Strain Preparation: Grow the actinobacterial strain and the inducer strain (e.g., Tsukamurella pulmonis or other mycolic acid-containing bacteria) in suitable liquid media to mid-exponential phase.

- Co-culture Setup:

- Method A (Agar-based): Spot or streak both cultures on solid agar medium, ensuring physical contact or proximity.

- Method B (Liquid-based): Inoculate the inducer strain into the culture of the actinobacterium after 24-48 hours of growth.

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate for an extended period (7-14 days). Monitor metabolite production through analytical techniques like LC-HRMS and compare the metabolic profile with axenic control cultures [20].

Protocol 4: High-Throughput Fermentation and Metabolite Analysis

- Miniaturized Fermentation: Inoculate 24- or 96-deep well plates with 1-2 mL of production media per well. Test multiple media formulations and culture conditions (pH, temperature, aeration) to stimulate secondary metabolism.

- Metabolite Extraction: After 5-10 days, extract metabolites by adding an equal volume of organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or methanol) to the culture broth. Shake for 1-2 hours, then centrifuge to separate the organic layer.

- Chemical Dereplication: Analyze extracts using LC-HRMS. Compare acquired mass spectra and retention times with in-house or public databases (e.g., Natural Products Atlas, DNP) to rapidly identify known compounds and prioritize novel ones.

- Bioactivity Screening: Screen extracts against a panel of clinically relevant pathogens (e.g., MRSA, Candida albicans, Mycobacterium tuberculosis) using microbroth dilution or disk diffusion assays [16].

Diagram 2: Microbial Interaction-Driven Compound Induction. This diagram outlines the key steps in using co-culture with inducer strains to activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in actinobacteria.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Actinobacteria Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humic Acid-Vitamin (HV) Agar | Selective isolation of actinobacteria | Primary isolation from soil and plant samples | Oligotrophic nature favors slow-growing actinobacteria |

| Starch-Casein Agar | General purpose medium for actinobacteria | Enumerating and isolating diverse actinobacterial strains | Starch and casein serve as complex carbon and nitrogen sources |

| Artificial Seawater | Isolation and cultivation of marine actinobacteria | Cultivation of halophilic and marine strains | Replicates ionic composition of seawater; crucial for osmoadaptation |

| Nalidixic Acid | Antibacterial agent (inhibits DNA gyrase) | Selective agent in media to suppress Gram-negative bacteria | Typically used at 20 µg/mL final concentration |

| Nystatin/ Cycloheximide | Antifungal agents | Suppression of fungal contaminants in isolation plates | Used at 50 µg/mL; filter-sterilize and add to cooled media |

| Ethyl Acetate | Organic solvent for metabolite extraction | Liquid-liquid extraction of culture broths | Effectively extracts a wide range of medium-polarity compounds |

| Super Optimal Broth (SOB) | Medium for high-density growth | Preparation of electrocompetent Streptomyces cells | Contains osmoprotectants for improved cell viability |

| Restriction-Free (RF) Cloning Kit | Seamless DNA cloning | Assembly of large BGCs for heterologous expression | Avoids reliance on restriction sites; ideal for large constructs |

| pSET152 Vector | Integrating E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector | Stable integration of DNA into the attB site of Streptomyces chromosomes | Allows for conjugal transfer from E. coli to actinobacteria |

| AntiSMASH Database | In silico identification of BGCs | Genome mining for novel natural product discovery | Web server and standalone version available for comprehensive analysis |

The exploration of rare and extremophilic actinobacteria represents a strategically vital and underexplored frontier in the quest for novel bioactive compounds. As detailed in this guide, these organisms, adapted to unique ecological niches, possess a tremendous and largely untapped biosynthetic potential. The convergence of traditional microbiology with advanced omics technologies and synthetic biology is creating unprecedented opportunities to access this chemical diversity.

Future success in this field will depend on several key developments: First, the continued refinement of culture-dependent and independent methods to access the "uncultivable" majority. Second, the intelligent integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) to guide the targeted activation and engineering of promising BGCs. Finally, the application of sophisticated synthetic biology tools to design optimized microbial chassis and refactor silent pathways for efficient expression. By systematically exploring the molecular treasures hidden within rare and extremophilic actinobacteria, and by leveraging the powerful toolkit of synthetic biology, researchers are poised to usher in a new era of drug discovery, potentially yielding the next generation of therapeutics to address the mounting challenges of antibiotic resistance and human disease.

In the context of synthetic biology, particularly for engineering actinobacteria to produce novel compounds, the precise identification of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) is a critical first step. BGCs are genomic loci containing all genes necessary for the biosynthesis of a secondary metabolite, such as antibiotics, antifungals, or anticancer agents [2] [22]. Genome mining has transitioned natural product discovery from a traditional activity-based screening process to a sequence-based, rational strategy [2]. This guide provides an in-depth technical analysis of three core bioinformatic tools—antiSMASH, PRISM, and NaPDoS—that form the foundation of modern BGC discovery and characterization, enabling researchers to decode the vast biosynthetic potential encoded within actinobacterial genomes.

The field of computational genome mining has developed a suite of tools, each with distinct strengths and methodological approaches. The table below summarizes the core technical specifications for antiSMASH, PRISM, and NaPDoS.

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications of Key BGC Identification Tools

| Feature | antiSMASH | PRISM | NaPDoS2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Approach | Rule-based detection using curated pHMMs [23] [24] | Chemical structure prediction from genetic assembly [25] | Phylogeny-based classification of KS and C domains [26] |

| Key Functionality | Identifies & annotates BGC boundaries and core genes [23] | Predicts complete 2D chemical structures of metabolites [25] | Classifies PKS and NRPS domains into evolutionary/functional classes [26] |

| Supported BGC Types | 81 cluster types (e.g., NRPS, PKS, RiPPs, terpenes) [24] | 16 classes (e.g., NRPS, PKS, RiPPs, β-lactams, nucleosides) [25] | Type I & II PKS KS domains; NRPS C domains [26] |

| Input Data | Genome sequences (draft/complete); Metagenome assemblies [23] | Genome sequences [25] | Nucleotide or amino acid sequences (genomic, metagenomic, amplicon) [26] |

| Strengths | Comprehensive detection; industry gold standard; extensive visualization [23] [2] | High-accuracy chemical structure prediction; activity prediction [25] | Works with incomplete data; provides evolutionary context; fast [26] |

Table 2: Detection Capabilities for Major Secondary Metabolite Classes

| Metabolite Class | antiSMASH | PRISM | NaPDoS2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Ribosomal Peptides (NRPS) | Primary detection & module analysis [23] | Detailed chemical structure prediction [25] | C domain phylogeny & classification [26] |

| Type I Polyketides (PKS) | Primary detection & module analysis [23] [24] | Detailed chemical structure prediction [25] | KS domain phylogeny & classification (modular/iterative) [26] |

| Type II Polyketides (PKS) | Primary detection [23] | Detailed chemical structure prediction [25] | KS domain phylogeny & subclassification [26] |

| RiPPs | Primary detection; precursor peptide analysis [23] [24] | Structure prediction for specific RiPP classes [25] | Not a primary function |

| Other Classes (e.g., β-lactams, aminoglycosides) | Growing support (e.g., 2-deoxy-streptamine in v7) [24] | Broad support including β-lactams, nucleosides [25] | Not a primary function |

Detailed Tool Specifications & Experimental Protocols

antiSMASH (antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell)

Technical Deep Dive: antiSMASH operates as a modular pipeline using manually curated and validated "rules" to define the core biosynthetic functions that constitute a BGC [23]. It employs profile hidden Markov models (pHMMs) from databases like PFAM, TIGRFAMs, and SMART to identify these core biosynthetic genes [24]. A key feature introduced in version 6 is "sideloading," which allows for the integration of results from other prediction tools (e.g., DeepBGC) into the antiSMASH analysis framework, enabling comparative assessment of different detection methods on the same genomic input [23] [24]. For NRPS and PKS clusters, antiSMASH detects not only enzymatic domains but also the multi-modular structure of these megaenzymes, which is critical for predicting the biosynthetic assembly line [23]. Recent versions have also integrated RRE-Finder to better identify tailoring enzymes in RiPP clusters and added CompaRiPPson to assess the novelty of predicted RiPP precursor peptides against known databases [23] [24].

Standard Operating Procedure (SOP):

- Input Preparation: Prepare your genomic data in FASTA format (complete genome, draft assembly, or BGC region).

- Submission: Access the antiSMASH web server (https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org/) or install the standalone version.

- Job Configuration: Select the appropriate input type and configure analysis parameters. For actinobacteria, the "bacteria" taxon and "strict" detection strictness are typically used. Enable specific analysis modules (e.g., ClusterCompare, KnownClusterBlast) based on your needs.

- Analysis Execution: Submit the job. Processing time varies from minutes to hours, depending on genome size and server load.

- Result Interpretation: Analyze the main results page, which provides:

- Region Overview: A graphical map of all detected BGCs within the genomic context.

- Cluster Details: In-depth information for each BGC, including domain architecture for NRPS/PKS clusters and predicted core biosynthetic genes.

- Comparative Analysis: Results from ClusterBlast (similarity to known clusters in the antiSMASH database) and MIBiG Blast (similarity to experimentally characterized clusters in the MIBiG repository) [23].

Figure 1: The antiSMASH Analysis Workflow. The pipeline progresses from raw genomic input to comprehensive BGC annotations through a series of automated steps including gene calling, rule-based detection, and comparative analysis.

PRISM (PRediction Informatics for Secondary Metabolites)

Technical Deep Dive: PRISM distinguishes itself by moving beyond BGC identification to predict the likely two-dimensional chemical structures of the encoded metabolites [25]. It connects biosynthetic genes to the enzymatic reactions they catalyze, enabling the in silico reconstruction of complete biosynthetic pathways [25]. PRISM uses 1,772 hidden Markov models (HMMs) and implements 618 in silico tailoring reactions to predict structures for 16 different classes of secondary metabolites [25]. A key aspect of its methodology is the combinatorial consideration of all possible sites for tailoring reactions (e.g., halogenation, glycosylation) when multiple potential substrates exist, generating a set of plausible structural variants for a single BGC [25]. This structure-first approach allows for the application of machine learning models to predict the likely biological activity of the encoded molecules, facilitating the prioritization of BGCs for experimental follow-up [25].

Standard Operating Procedure (SOP):

- Input Preparation: Assemble your genomic sequence in FASTA format.

- Submission: Navigate to the PRISM web interface (http://prism.adapsyn.com).

- Analysis Selection: Upload the genome and select the desired analysis type. PRISM will automatically identify BGCs and run its structure prediction algorithms.

- Result Interpretation: The output includes:

- Predicted Structures: One or more 2D chemical structures in a visual format, representing the most likely products of the BGC.

- Combinatorial Plans: A list of generated structural variants, ranked by likelihood.

- BGC Annotation: The genomic location and genes comprising the cluster linked to the structural prediction.

Figure 2: The PRISM Structure Prediction Workflow. The process begins with BGC identification and proceeds to computationally reconstruct the biosynthetic pathway, generating potential chemical structures and predicting their activity.

NaPDoS (Natural Product Domain Seeker)

Technical Deep Dive: NaPDoS2 takes a targeted, phylogeny-based approach by focusing on ketosynthase (KS) and condensation (C) domains from polyketide synthases (PKS) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), respectively [26]. It classifies these domains into one of 41 phylogenetically distinct classes and subclasses that reflect well-supported biosynthetic functions and evolutionary relationships [26]. This method is particularly powerful for assessing biosynthetic potential from incomplete datasets, such as poorly assembled genomes, metagenomes, or PCR amplicon data, where full BGCs cannot be reconstructed [26]. The classification provides direct insight into the type of polyketide or peptide likely produced (e.g., non-reducing, highly reducing, or partially reducing fungal PKSs; trans-AT PKSs) and helps distinguish between biosynthetic KS domains and those involved in primary fatty acid synthesis [26].

Standard Operating Procedure (SOP):

- Input Preparation: Input can be amino acid sequences (for KS or C domains), nucleotide sequences (whole genomes, contigs, or amplicons), or raw sequencing reads.

- Submission: Use the NaPDoS2 webtool (http://napdos.ucsd.edu/napdos2/).

- Domain Selection: Specify whether to search for KS domains, C domains, or both.

- Analysis Execution: Submit the job. The DIAMOND-based pipeline is efficient, with most jobs completing within minutes [26].

- Result Interpretation: Review the "Domain Classification Summary" page, which lists detected domains grouped by their phylogenetic classification. Each result links to a detailed view showing the phylogenetic placement and associated BGC information from the reference database.

Figure 3: The NaPDoS2 Domain Analysis Workflow. This specialized tool extracts and aligns KS and C domains against a curated reference database, classifying them based on phylogenetic analysis.

An Integrated Workflow for BGC Discovery in Actinobacteria

For a comprehensive analysis of actinobacterial genomes, these tools are best deployed in a synergistic, integrated workflow. The sequential application leverages the unique strengths of each platform, from broad discovery to detailed chemical prediction.

Proposed Integrated Protocol:

- Comprehensive Screening with antiSMASH: Begin by processing the entire actinobacterial genome through antiSMASH. This provides a complete overview of all putative BGCs, defines their genomic boundaries, and offers initial functional annotations [27] [2].

- Structure-Focused Interrogation with PRISM: Submit the genome to PRISM, or focus specifically on the BGC regions identified by antiSMASH. PRISM will generate predicted chemical structures for the detectable clusters, providing critical insight into the potential novelty and properties of the metabolites [25].

- Domain-Centric Validation and Classification with NaPDoS2: For BGCs identified as NRPS or PKS (the most common types in actinobacteria), extract the relevant KS and C domain sequences and analyze them with NaPDoS2. This step validates the antiSMASH annotation and provides an evolutionary classification that can reveal novel biosynthetic mechanisms or relate the cluster to known structural classes [26].

- Prioritization and Experimental Design: Synthesize the results from all three tools. Prioritize BGCs that are:

- Novel hybrids of known, productive classes (from antiSMASH and NaPDoS2).

- Predicted to produce structures with desirable physicochemical properties or predicted bioactivity (from PRISM).

- Associated with specific regulatory elements, such as transcription factor binding sites (identified by antiSMASH 7.0) [24].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Function in BGC Research |

|---|---|---|

| MIBiG (Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster) [23] [24] | Database | Repository of experimentally characterized BGCs used as a gold-standard reference for comparative analysis. |

| antiSMASH-DB [23] [24] | Database | A large-scale database of pre-computed antiSMASH results for publicly available genomes, used for comparative analysis. |

| LogoMotif DB [24] | Database | Curated collection of transcription factor binding site profiles, used by antiSMASH to predict cluster regulation. |

| RRE-Finder [23] | Algorithm/Tool | Identifies RiPP Recognition Elements, helping to confidently identify tailoring enzymes in RiPP clusters. |

| BiG-SCAPE / BiG-SLiCE [23] [24] | Analysis Tool | Used for large-scale comparison, classification, and networking of BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs). |

antiSMASH, PRISM, and NaPDoS represent complementary pillars of modern BGC identification. antiSMASH offers unparalleled comprehensiveness in detection, PRISM provides unique insights into chemical output, and NaPDoS delivers robust phylogenetic context. For synthetic biologists engineering actinobacteria, the integration of these tools creates a powerful pipeline for moving from a raw genome sequence to prioritized, high-value BGC targets. This bioinformatic triage is indispensable for efficiently harnessing the genomic potential of actinobacteria to discover and design the novel compounds needed to address pressing challenges in medicine and agriculture.

Synthetic Biology Toolbox: From Genome Mining to Precision Pathway Engineering

CRISPR-Cas Systems for Advanced Genome Editing and BGC Manipulation

Actinobacteria, particularly Streptomyces species, are Gram-positive bacteria renowned for their exceptional capacity to produce structurally complex secondary metabolites. These metabolites, often referred to as natural products, include a vast array of antibiotics, antifungals, and anticancer agents that have been indispensable to human health. It is estimated that approximately 60% of all clinically used antibiotics originate from actinomycetes [28]. Genomic sequencing has revealed that this biosynthetic potential is encoded within Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs), which are sets of co-localized genes responsible for the synthesis of specific natural products. Strikingly, the average actinomycete genome contains approximately 16 BGCs, with some strains harboring more than 60 [28]. However, a significant challenge persists: the majority of these BGCs are "silent" or "cryptic" under standard laboratory cultivation conditions, meaning their corresponding natural products are not produced and thus remain uncharacterized [29] [30].

The activation and manipulation of these silent BGCs is a central challenge in modern natural product discovery. Traditional genetic manipulation methods in actinomycetes are often hampered by their high GC-content genomes, genetic instability, and the presence of native DNA defense systems [29] [28]. The emergence of CRISPR-Cas (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-associated proteins) technologies has revolutionized this field. These systems provide researchers with a programmable, efficient, and versatile toolkit for precise genome editing, activation, and refactoring of BGCs, thereby unlocking the immense hidden chemical potential within actinobacterial genomes for novel drug discovery and development [31].

CRISPR-Cas System Fundamentals and Classification

CRISPR-Cas systems function as adaptive immune systems in prokaryotes, providing sequence-specific defense against mobile genetic elements like viruses and plasmids. Their utility in genome engineering derives from their ability to be reprogrammed to target virtually any DNA sequence of interest. All functional CRISPR-Cas systems consist of a Cas nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA). The gRNA, a short RNA sequence complementary to the target DNA, directs the Cas nuclease to a specific genomic locus, where the nuclease creates a double-strand break (DSB). The cell's subsequent repair of this DSB can be harnessed to introduce specific genetic modifications [32] [31].

These systems are broadly classified into two classes and six major types based on their effector module composition and machinery [32] [33]:

- Class 1 (includes types I, III, and IV) utilizes a multi-subunit Cas protein complex for nucleic acid cleavage.

- Class 2 (includes types II, V, and VI) employs a single, large Cas protein for target interference, making them significantly easier to adapt for biotechnological applications.

Table 1: Key CRISPR-Cas Types and Their Characteristics for Genetic Engineering

| Type | Signature Gene | Class | Target | Key Features for Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type II | cas9 |

2 | DNA | The most widely used system; requires a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9). |

| Type V | cas12/cpf1 |

2 | DNA | Often recognizes a T-rich PAM; can process its own pre-crRNA, enabling multiplexed editing from a single transcript. |

| Type VI | cas13 |

2 | RNA | Targets RNA instead of DNA, useful for gene knockdown without altering the genome. |

Bioinformatic analyses indicate that around 50% of sequenced actinobacterial genomes naturally possess CRISPR-Cas systems, with Type I systems being the most prevalent, followed by Type III and Type II [28]. For example, a study of Streptomyces genomes found that 37.1% (26 out of 70) encode one or more CRISPR-Cas systems, most of which are Type I-E [28]. However, the well-known model strain Streptomyces coelicolor M145 lacks a chromosomal CRISPR-Cas system, facilitating its use as an engineering chassis [28].

CRISPR-Cas Toolkit for Actinobacterial Genome Editing

The development of CRISPR-Cas tools for actinomycetes has primarily involved the heterologous expression of Class 2 systems, which are easier to implement than multi-protein Class 1 systems.

Key Tool Development

The first generation of CRISPR tools for Streptomyces employed the codon-optimized Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 nuclease (SpCas9). Pioneering plasmids such as pCRISPomyces, pKCcas9dO, and pCRISPR-Cas9 demonstrated efficient gene knockouts, deletions, and insertions in various Streptomyces strains [31]. To address limitations such as Cas9 toxicity or the requirement for specific PAM sites, subsequent systems have leveraged alternative nucleases, including:

- FnCpf1 (Cas12a): Offers a different PAM requirement (TTN) and the ability to process its own crRNA array, simplifying multiplexed genome editing [31].

- St1Cas9 and SaCas9: Provide different PAM specificities, expanding the range of targetable genomic sites [31].

Experimental Protocol: CRISPR-Cas Mediated Gene Knockout

The following detailed methodology is adapted from established protocols for creating targeted gene knockouts in Streptomyces species [31].

Step 1: gRNA Design and Vector Construction

- Identify Target Sequence: Select a 20-nucleotide target sequence within the gene of interest that is immediately followed by a PAM sequence (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9).

- Design and Synthesize gRNA Oligos: Design two complementary oligonucleotides corresponding to the target sequence with appropriate 5' overhangs for ligation into the CRISPR plasmid.

- Clone gRNA into Plasmid: Anneal and ligate the oligonucleotides into a Streptomyces-optimized CRISPR-Cas plasmid (e.g., pCRISPomyces-2) downstream of a constitutive promoter.

Step 2: Protoplast Preparation and Transformation

- Culture and Harvest Cells: Grow the Streptomyces strain in a rich liquid medium to mid-exponential phase. Harvest the mycelia by centrifugation.

- Generate Protoplasts: Resuspend the washed mycelial pellet in an osmotic stabilizer solution (e.g., 10.3% sucrose) containing lysozyme (e.g., 1-2 mg/mL). Incubate at 30°C until >95% of cells are converted to protoplasts (visual confirmation under microscope).

- Wash and Concentrate: Gently pellet the protoplasts and wash twice with cold osmotic stabilizer solution.

Step 3: Introduction of DNA and Regeneration

- Transform Protoplasts: Mix ~10^9 protoplasts with 1-10 µg of the purified CRISPR plasmid DNA. Add 50% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 1000 to facilitate DNA uptake.

- Plate for Regeneration: Plate the transformation mixture onto regeneration medium (R2YE or equivalent) lacking the antibiotic selection. Incubate at 30°C for 16-24 hours.

- Overlay with Selective Antibiotic: After the initial regeneration, overlay the plates with soft agar containing the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., apramycin, 50 µg/mL) to select for transformants.

Step 4: Screening and Verification

- Isolate and Culture Transformants: Pick individual colonies to fresh antibiotic-containing media.

- Extract Genomic DNA: Harvest mycelia from liquid cultures and extract genomic DNA using a standard microbial DNA extraction kit.

- Verify Genotype: Use PCR to amplify the targeted genomic region and perform Sanger sequencing of the PCR product to confirm the presence of indels or the intended deletion.

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for performing CRISPR-Cas mediated gene knockout in actinomycetes such as Streptomyces species.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful genetic manipulation of actinomycetes requires a suite of specialized reagents and genetic elements.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas Engineering in Actinomycetes

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Plasmid Backbone | Shuttle vector for E. coli and actinomycetes; contains codon-optimized cas9/cpf1, gRNA scaffold, and selectable marker. |

pCRISPomyces, pKCcas9dO |

| gRNA Scaffold | Structural part of the guide RNA that binds the Cas nuclease. | S. pyogenes gRNA scaffold |

| Constitutive Promoters | Drives constant expression of Cas genes and gRNA. | ermE*, kasOp* |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes for selecting successful transformants. | aac(3)IV (apramycin), tsr (thiostrepton) |

| Templates for HDR | DNA templates for introducing specific mutations or insertions via Homology-Directed Repair. | Double-stranded DNA fragments, cosmid/BAC DNA |

| Protoplasting Solutions | Enzymes and osmotic stabilizers for generating cell wall-free protoplasts. | Lysozyme, 10.3% Sucrose solution |

| PEG 1000 | Polyethylene glycol facilitates DNA uptake during protoplast transformation. | 50% PEG 1000 solution |

| D-methionine (S)-S-oxide | D-methionine (S)-S-oxide, CAS:50896-98-5, MF:C5H11NO3S, MW:165.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Chloro-2-methylpent-2-ene | 4-Chloro-2-methylpent-2-ene, CAS:21971-94-8, MF:C6H11Cl, MW:118.60 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications for BGC Activation and Manipulation

Beyond simple gene knockouts, CRISPR-Cas systems enable sophisticated engineering strategies to activate and refactor silent BGCs.

Transcriptional Activation Using dCas9

A primary strategy for BGC activation involves the use of catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9), which binds DNA without cleaving it. When fused to transcriptional activator domains (e.g., VP64), dCas9 can be targeted to the promoters of silent BGCs to drive their expression [34] [31]. For instance, this approach has been successfully applied to activate the erythromycin BGC in Saccharopolyspora erythraea by integrating strong, synthetic promoters upstream of the biosynthetic genes [31].

BGC Refactoring and Heterologous Expression

CRISPR-Cas systems significantly accelerate the process of BGC refactoring—the replacement of native regulatory elements with standardized, well-characterized parts to optimize expression [29] [34]. This is particularly useful for BGCs from rare or genetically intractable actinomycetes. Refactored BGCs can be efficiently integrated into the chromosomes of optimized heterologous hosts, such as Streptomyces coelicolor or "clean" chassis strains like Streptomyces albus, which have a reduced number of endogenous BGCs to minimize background interference [31].

Diagram 2: Strategic pathways for activating silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) using CRISPR-Cas technologies, either within the native host or via heterologous expression.

In Vitro Capture of BGCs