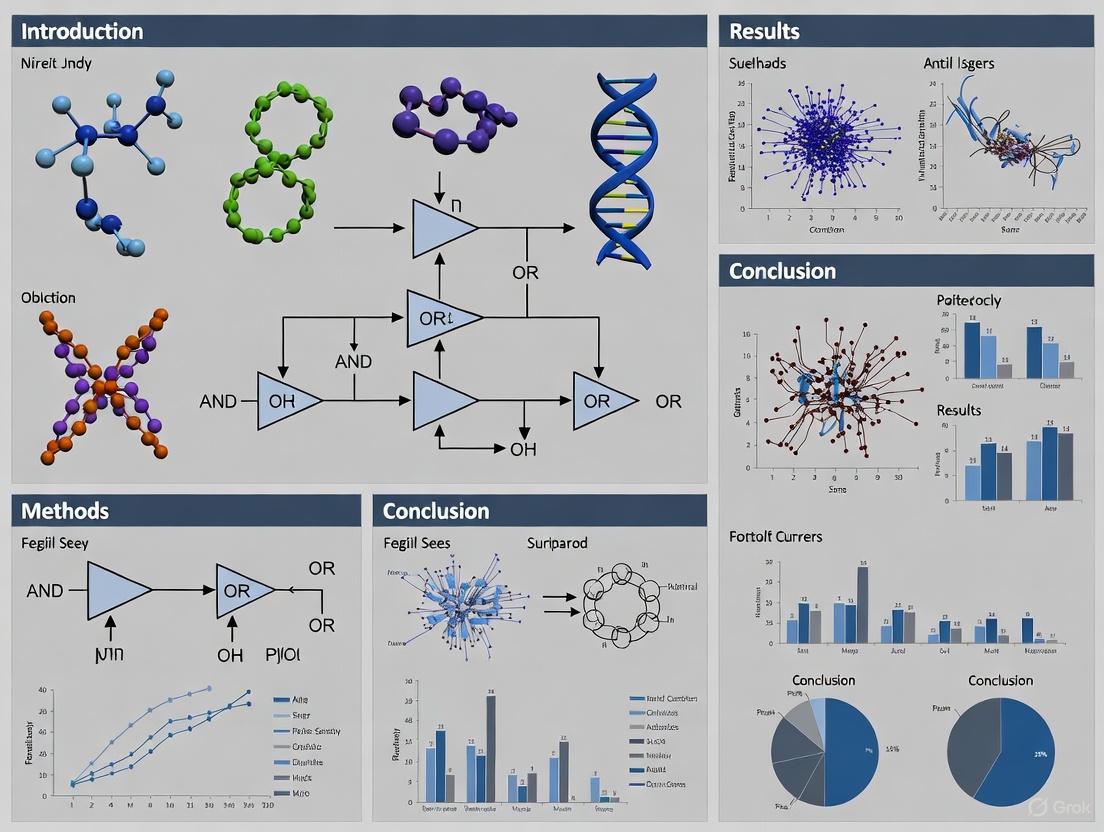

Genetic Circuit Design: Foundational Concepts, Methodologies, and Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the foundational concepts and modern methodologies in genetic circuit design, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Genetic Circuit Design: Foundational Concepts, Methodologies, and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the foundational concepts and modern methodologies in genetic circuit design, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the core principles of transcriptional control, logic gates, and circuit dynamics, before detailing advanced design strategies like circuit compression and multicellular implementations. The scope extends to critical troubleshooting for challenges such as metabolic burden and evolutionary instability, and concludes with a review of predictive modeling and validation frameworks that enhance reliability for therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Core Principles and Components of Genetic Circuits

Genetic circuit design represents a foundational pillar of synthetic biology, aiming to program living cells with novel functions by repurposing the molecular machinery of life. These circuits are engineered networks of genetic components that enable cells to perform complex computations, navigate environments, and build intricate patterns by initiating gene expression in response to specific signals [1]. The potential applications of this technology are revolutionary, spanning from living therapeutics and advanced drug development to the atomic manufacturing of functional materials [1]. Despite this promise, genetic circuit design remains one of the most challenging aspects of genetic engineering due to the necessity of precisely balancing component regulators, the difficulty of screening complex dynamic circuits, and the profound sensitivity of synthetic systems to environmental context and genetic background [1].

This technical guide examines the evolution of biological circuit design from single-cell implementations to distributed multicellular systems. It explores the core principles governing their operation, details advanced methodologies for their characterization, and provides a practical toolkit for their implementation, all framed within the context of foundational concepts for research in genetic circuit design.

Core Components and Regulator Classes

Transcriptional circuits operate primarily by controlling the flux of RNA polymerase (RNAP) on DNA. Several classes of molecular regulators have been engineered to manipulate this flux, each with distinct characteristics and applications [1].

DNA-Binding Proteins

DNA-binding proteins represent the most established class of genetic regulators. They function by binding to specific operator sequences on the DNA to either block (repress) or recruit (activate) RNAP. Simple logic gates, such as NOT and NOR gates, are typically constructed using inducible promoters that drive the expression of these repressors [1]. More complex circuits, including dynamic systems like pulse generators, bistable switches, and oscillators, have been successfully built using DNA-binding proteins, highlighting their versatile signal-processing capabilities [1]. The engineering of zinc finger proteins (ZFPs) and transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) has significantly expanded the library of available orthogonal repressors.

Invertases

Invertases are site-specific recombinase proteins that facilitate the inversion of DNA segments between specific binding sites. Serine integrases, a class of invertases, are particularly valuable for building memory circuits because they catalyze unidirectional reactions that permanently flip DNA orientation, thus storing state information without continuous energy expenditure [1]. All two-input logic gates, including AND and NOR, have been constructed using orthogonal serine integrases. A significant limitation is that these reactions are slow, typically requiring 2–6 hours, and can generate mixed populations when targeting multicopy plasmids [1].

CRISPRi Systems

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) systems utilize a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) protein complexed with a guide RNA (gRNA) to bind specific DNA sequences and form a steric block that interferes with RNAP progression [1]. A key advantage of CRISPRi for synthetic circuit design is the unparalleled designability of the RNA-DNA interaction, which enables the creation of very large sets of orthogonal guide sequences for targeting numerous promoters simultaneously. This capability is critical for the construction of large-scale genetic circuits. CRISPR systems can also be adapted for transcriptional activation (CRISPRa) through the fusion of RNAP-recruiting domains to the dCas9 protein [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Genetic Regulator Classes

| Regulator Class | Core Mechanism | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Proteins | Protein binds operator to block/recruit RNAP | NOT/NOR gates, oscillators, switches [1] | Extensive characterization, dynamic circuits possible [1] | Limited orthogonal sets; can be burdensome [1] |

| Invertases | Recombinase flips DNA segment orientation | Memory circuits, counters, logic gates [1] | Permanent state storage; low energy maintenance [1] | Slow reaction speed (2-6 hrs); potential for mixed populations [1] |

| CRISPRi/a | dCas9-gRNA binds DNA to block/recruit RNAP | Large-scale logic, tunable repression/activation [1] | Highly designable; large orthogonal gRNA sets possible [1] | Requires expression of both dCas9 and gRNA |

Advanced Multicellular Circuit Architectures

A paradigm shift from single-cell to multicellular circuit implementation has emerged to overcome inherent limitations of complexity, resource competition, and functional incompatibility within single cells. Distributed multicellular feedback loops represent a leading approach in this domain [2].

Principles of Distributed Control

This architecture employs a microbial consortium comprising distinct cellular populations, typically a "controller" population and a "target" population, which communicate via orthogonal quorum sensing (QS) molecules [2]. This division of labor allows for the distribution of complex functions across specialized strains, enhancing overall system robustness and modularity. The controller population is engineered to sense the target population's output, compare it to a reference signal, and generate a corrective input based on a pre-defined control logic [2].

Implemented Multicellular Feedback System

Recent work has successfully implemented a multicellular control architecture where a controller E. coli population regulates GFP expression in a target E. coli population [2]. The system utilizes two orthogonal QS molecules: 3–O–C6-HSL (produced by the targets) and 3–O–C12-HSL (produced by the controllers) [2].

The core control logic is an antithetic feedback motif within the controller cells. This motif involves a σ factor and an anti-σ factor that sequesters it [2].

- Sensing & Comparison: The σ factor's production is induced by the reference signal (IPTG), while the anti-σ factor's production is activated by the target-derived 3–O–C6-HSL. The interaction between the σ and anti-σ factors effectively compares the reference and target output signals [2].

- Actuation: The free σ factor induces expression of lasI, which produces the controller output molecule 3–O–C12-HSL. This molecule diffuses to the target population and activates the plas promoter driving gfp and luxI expression [2].

- Closed-Loop Regulation: If GFP expression exceeds the reference level, excess 3–O–C6-HSL from targets increases anti-σ production in controllers. This reduces free σ, lowering 3–O–C12-HSL production and subsequently down-regulating GFP in the targets, thereby achieving robust perfect adaptation [2].

Diagram 1: Multicellular Feedback Control Architecture.

Quantitative Characterization of Circuit Performance

Precise quantification of genetic circuit performance is essential for both understanding natural systems and reliably engineering synthetic ones. This is particularly challenging in complex multicellular organisms like filamentous fungi.

Microfluidic Platform for Fungal GRCs

An advanced microfluidic platform has been developed to characterize Gene Regulatory Circuits (GRCs) in Aspergillus nidulans at the single-cell level [3]. The platform features customized chips with a height of 5 µm, designed to match the diameter of fungal conidia (spores) and to constrain mycelial growth to a single layer, thus preventing signal distortion from multi-layered hyphae [3]. Each chip contains multiple U-shaped channels and chambers with central barriers that trap individual conidia, allowing for long-term, single-layer observation of germination and gene expression under controlled conditions [3].

Characterized Gene Regulatory Circuits

This platform was used to quantitatively characterize 30 transcription factor-promoter combinations from two representative fungal GRCs:

- The PfmaH-GRC, which regulates the synthesis of 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene (DHN) melanin in Pestalotiopsis fici [3].

- The AflR-GRC, which regulates sterigmatocystin biosynthesis in A. nidulans [3].

The dynamic expression data collected for each TF-promoter pair enabled their standardization and subsequent use in refactoring biosynthetic pathways. In a proof-of-concept application, the quantified GRCs were used to precisely control the yields of bioactive metabolites and activate a silenced biosynthetic gene cluster to produce novel dendrobines [3].

Diagram 2: Fungal GRC Quantification Workflow.

Table 2: Quantitative Characterization of Fungal Gene Regulatory Circuits

| Characterization Aspect | DHN Melanin GRC (PfmaH) | Sterigmatocystin GRC (AflR) |

|---|---|---|

| Organism | Pestalotiopsis fici [3] | Aspergillus nidulans [3] |

| Cluster Size | 7 genes [3] | 26 genes [3] |

| Pathway-Specific TF | PfmaH [3] | AflR [3] |

| Biological Role | Fungal pathogenesis & defense [3] | Mycotoxin production [3] |

| Quantified Pairs | 30 TF-Promoter combinations total across both GRCs [3] | |

| Primary Method | Dynamic single-cell fluorescence in microfluidic chips [3] | |

| Key Application | Refactoring pathways for metabolite yield control & novel compound production [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of genetic circuits, particularly advanced architectures like multicellular consortia, requires a specific set of biological tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Circuit Implementation

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Key Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal σ/Anti-σ Factor Pairs | Protein-based regulators | Core comparator in antithetic integral feedback control [2] | Implementing robust perfect adaptation in controller cells [2] |

| Quorum Sensing Systems (e.g., LuxI/LuxR, LasI/LasR) | Intercellular communication module | Enables diffusion-based signaling between distinct cell populations [2] | Relaying sensor and actuator signals in a microbial consortium [2] |

| Degradation Tags (e.g., ssrA tag) | Post-translational control | Accelerates protein degradation, improves response time, prevents toxic accumulation [2] | Tuning dynamics of σ and anti-σ factors in controllers [2] |

| Serine Integrases (e.g., Bxb1, φC31) | DNA recombinase | Catalyzes unidirectional DNA inversion for permanent memory storage [1] | Constructing logic gates and memory locks in genetic circuits [1] |

| dCas9 and Guide RNA (gRNA) | RNA-programmable regulator | Provides highly designable, sequence-specific transcriptional repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) [1] | Creating large-scale, complex logic circuits with minimal orthogonal parts [1] |

| Microfluidic Chips (Customized) | Analytical platform | Enables long-term, single-cell dynamic measurement in multicellular organisms [3] | Quantitative characterization of fungal GRCs and circuit performance [3] |

| Modular DNA Assembly Toolbox (e.g., MoClo) | DNA assembly framework | Facilitates hierarchical, standardized construction of multi-gene circuits [3] | Refactoring biosynthetic gene clusters with standardized regulatory parts [3] |

| Lumisterol-d3 | Lumisterol-d3 Stable Isotope|For Research Use | Lumisterol-d3 is a high-quality stable isotope for research. Study photobiology, vitamin D pathways, and cancer mechanisms. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 2,3-Dichloromaleonitrile | 2,3-Dichloromaleonitrile|High-Purity Building Block | 2,3-Dichloromaleonitrile is a versatile reagent for synthesizing heterocycles like pyrazines and triazoles. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

The field of genetic circuit design is evolving from the assembly of simple, single-cell switches to the engineering of sophisticated, multicellular consortia capable of robust, programmable behaviors. This progression is supported by the development of advanced quantitative characterization methods, such as microfluidic single-cell analysis, and a deeper theoretical understanding of control principles in biological systems. The integration of these tools and concepts—from molecular regulators like CRISPRi and integrases to system-level architectures like distributed antithetic control—provides a comprehensive foundation for researchers to tackle the next generation of challenges in synthetic biology. This will accelerate the development of reliable biological circuits for advanced applications in therapeutics, biosynthesis, and biocomputing.

The engineering of genetic circuits represents a cornerstone of synthetic biology, enabling the programming of cellular behavior for applications ranging from bioproduction to living therapeutics. The functional core of these circuits comprises regulatory proteins that can sense inputs, process signals, and generate specific outputs. Among the diverse arsenal of biological components available to synthetic biologists, three regulator classes have emerged as particularly fundamental: DNA-binding proteins, invertases, and CRISPR-based systems. These molecular workhorses operate at the DNA level to control gene expression through distinct mechanisms, each offering unique advantages for circuit design. DNA-binding proteins provide the foundational logic for transcriptional control through specific promoter interactions [1]. Invertases enable permanent genetic rearrangements that implement cellular memory and state changes [4]. CRISPR-based systems bring unprecedented programmability through RNA-guided targeting, allowing for sophisticated editing and regulation [5] [6]. This technical guide examines the structure, function, and experimental application of these three regulator classes within the context of genetic circuit design, providing researchers with both theoretical understanding and practical methodologies for their implementation.

DNA-Binding Proteins

Structural and Functional Classification

DNA-binding proteins (DBPs) constitute a diverse group of proteins that interact with DNA to regulate essential cellular processes, including transcription, replication, repair, recombination, and chromatin organization [7]. These proteins maintain genomic integrity and orchestrate gene expression through specific or non-specific binding mechanisms. DBPs are broadly classified based on their binding specificity and the nature of their target DNA, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Classification of DNA-Binding Proteins

| Classification | Binding Specificity | Recognition Mechanism | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-specific | Defined nucleotide motifs | Direct readout of base sequences through DNA grooves | Transcription factors (p53, NF-κB), CAP [7] |

| Non-sequence-specific | Structural DNA features | Recognition of DNA bending or electrostatic properties | Histones, HMG proteins [7] [8] |

| Single-stranded DNA-binding | Single-stranded DNA regions | Protection and stabilization of ssDNA | Replication Protein A (RPA), SSBs [7] |

The molecular basis of DNA recognition occurs through two primary mechanisms: direct readout and indirect readout. In direct readout, proteins recognize specific DNA sequences through direct contacts with DNA bases, typically via hydrogen bonds between protein side chains and the edges of bases in the major or minor groove [7]. In indirect readout, proteins recognize the intrinsic structure of DNA or its capacity to change shape upon protein binding, utilizing features such as base pair parameters, dinucleotide step parameters, groove widths, and electrostatic potential [7].

Major DNA-Binding Domains

DNA-binding domains represent the structural modules that facilitate interactions between proteins and DNA. Several well-characterized domains serve as the workhorses of transcriptional regulation in genetic circuits, each with distinct structural features and mechanisms.

The helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif consists of approximately 20 amino acids that form two α-helices separated by a β-turn [7]. The second helix serves as the recognition helix that inserts into the DNA major groove to facilitate base-specific interactions [7]. This motif can be associated with various effector domains that impact biological functions, with structural variations including bi-helical, tri-helical, tetra-helical, and winged HTH configurations [7].

Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) represent another major class characterized by finger-like domains stabilized by zinc ions [7]. These domains bind to the major groove of DNA for gene regulation and function as interaction modules for nucleic acids, proteins, and small molecules [7]. The majority of zinc finger structures fall into three main types: Cys2His2-like fingers, treble clef fingers, and zinc ribbons [7]. In the human genome, ZFN proteins form the largest class of transcription factors and feature diverse DNA-binding motifs that allow them to perform a wide range of biological functions [7].

The leucine zipper motif forms a coiled-coil structure where two α-helices associate through hydrophobic interactions between leucine residues located at every seventh position within a heptad repeat [7]. This simple yet stable tertiary structure is important for protein folding and design, with applications extending to biomaterials for nanobiotechnology and tissue engineering [7].

High mobility group (HMG) box domains consist of approximately 75 amino acid residues and facilitate DNA binding in both sequence-specific and non-sequence-specific manners, with a preference for non-B-type DNA structures like bent or unwound DNA [7]. These domains also participate in diverse protein-protein interactions and are found in various DNA-binding proteins, including chromatin remodelers [7].

Experimental Analysis of DNA-Protein Interactions

The study of DNA-protein interactions requires specialized methodologies to characterize binding specificity, affinity, and functional consequences. Several well-established techniques form the core experimental approaches in this domain.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA), also known as gel shift assay, is a widespread qualitative technique to study protein-DNA interactions of known DNA binding proteins [8]. This method exploits the principle that protein-bound DNA migrates more slowly through a non-denaturing polyacrylamide or agarose gel than unbound DNA. The assay is performed by incubating a purified DNA fragment with a protein extract, followed by electrophoresis and detection through autoradiography, fluorescence, or chemiluminescence. While EMSA provides information about binding occurrence and relative affinity, it does not yield precise binding site information.

DNase Footprinting Assay addresses the limitation of EMSA by identifying the specific binding sites of a protein on DNA at base-pair resolution [8]. In this technique, a radiolabeled DNA fragment is incubated with the DNA-binding protein, followed by partial digestion with DNase I. The protein-bound regions are protected from cleavage, creating a "footprint" visible when the cleavage products are separated by gel electrophoresis and compared to a control without the protein. This method allows precise mapping of protein-binding sites within DNA sequences.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) enables researchers to identify in vivo DNA target regions of known transcription factors under physiological conditions [8]. This method involves cross-linking proteins to DNA in living cells, shearing chromatin, immunoprecipitating the protein-DNA complexes with a specific antibody, and then analyzing the associated DNA sequences. When combined with high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-Seq) or microarrays (ChIP-chip), this technique provides genome-wide binding profiles for DNA-binding proteins.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for DNA-Protein Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Method | Primary Function | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) | Detect protein-DNA complex formation | Qualitative binding analysis, affinity studies | Requires protein purification, qualitative nature |

| DNase I | Nonspecific DNA cleavage | Footprinting assays, binding site mapping | Optimization of digestion conditions critical |

| Protein-specific Antibodies | Target protein immunoprecipitation | ChIP, ChIP-Seq, western blot | Antibody specificity and affinity determine success |

| Biotinylated DNA Oligos | Affinity capture | Pulldown assays, in vitro binding | Can be used with streptavidin beads |

| Fluorescence Reporter Plasmids | Transcriptional activity measurement | Promoter-reporter assays, circuit output | Choice of reporter (GFP, Luciferase, etc.) affects sensitivity |

Invertases and Site-Specific Recombinases

Biochemical Mechanisms and Structural Features

Invertases, more broadly classified as site-specific recombinases, are enzymes that facilitate DNA rearrangement by catalyzing the inversion, excision, or integration of specific DNA segments [4]. These enzymes perform "cut-and-paste" recombination through a mechanism involving DNA looping, cleavage, and re-ligation [1]. Two major classes of recombinases have been extensively utilized in genetic circuit design: tyrosine recombinases (e.g., Cre, Flp, FimBE) and serine integrases (e.g., Bxb1, PhiC31) [4].

The structural biology of invertases reveals key insights into their function. Saccharomyces invertase (SInv) displays an unusual octameric quaternary structure composed of two types of dimers arranged in a tetramer of dimers [9]. This oligomerization pattern plays a determinant role in substrate specificity because the assembly sets steric constraints that limit access to the active site of oligosaccharides exceeding four units [9]. Structural analysis shows that SInv folds into the catalytic β-propeller and β-sandwich domains characteristic of GH32 enzymes, with octamer formation occurring through a β-sheet extension that seems unique to this enzyme [9].

The recombination mechanism involves specific recognition sequences that flank the DNA segment to be rearranged. For tyrosine recombinases, such as Cre recombinase, the reaction proceeds through a Holliday junction intermediate without requiring high-energy cofactors [4]. Serine integrases utilize a different mechanism involving double-stranded breaks and typically catalyze unidirectional reactions, though their directionality can be controlled with cognate excisionases [4].

Applications in Genetic Circuit Design

Invertases and recombinases have become indispensable tools for implementing stable genetic changes in synthetic circuits, particularly for memory storage and state switching applications.

Memory Circuits and State Storage: The ability of recombinases to flip DNA permanently makes them ideal for memory storage, as once flipped, they do not require continuous input of materials or energy to maintain their new orientation [1]. For example, serine integrases without excisionases operate as memory circuits that remember exposure to input signals [1]. This principle has been exploited to build genetic counters using interleaving recombination sites, where inheritable states scale exponentially with the number of used recombinases [4].

Logic Gates: All two-input gates, including AND and NOR logic, have been constructed using orthogonal serine integrases [1]. These gates are organized such that two input promoters express a pair of orthogonal recombinases, which change RNA polymerase flux by inverting unidirectional terminators, promoters, or entire genes [1]. Since these systems typically employ unidirectional serine integrases without excisionases, they function as permanent memory circuits that record exposure to combinatorial input signals without distinguishing temporal sequence [1].

Inducible and Optogenetic Systems: Recombinase activity can be made conditional through various control mechanisms. In eukaryotes, global activity can be regulated by fusing the recombinase to the ligand binding domain of receptors, as demonstrated with Cre recombinase fused to the estrogen receptor, making activity dependent on estrogen receptor agonists [4]. Light-dependent control has been achieved through two primary strategies: splitting the recombinase and reconstituting it through light-inducible dimerization systems, or fusing the recombinase with light-responsive domains like the plant-derived LOV2 domain that unfolds a C-terminal helix upon blue-light illumination [4].

Diagram 1: Invertase-based logic gate implementing AND logic through sequential DNA inversion. Two input signals induce expression of orthogonal recombinases that sequentially invert DNA segments, ultimately producing an output only when both inputs are present.

Experimental Protocols for Recombinase Engineering

The implementation of recombinase-based circuits requires careful design and validation. The following protocol outlines key steps for characterizing recombinase function in genetic circuits.

Recombinase Activity Assay:

- Vector Design: Construct plasmids containing the recombinase gene under control of an inducible promoter, along with a reporter cassette flanked by recognition sites (e.g., loxP for Cre). The reporter should switch expression states upon recombination (e.g., from GFP to RFP or vice versa).

- Transformation: Introduce the construct into the target host cells (bacterial, yeast, or mammalian) via appropriate transformation methods.

- Induction: Activate recombinase expression through the appropriate inducer (small molecule, light, etc.) and incubate for sufficient time to allow recombination (typically 2-6 hours for full recombination).

- Analysis: Quantify recombination efficiency using flow cytometry for fluorescent reporters, or PCR and sequencing to verify specific recombination events.

- Kinetics Assessment: Measure recombination rates over time by sampling at intervals and quantifying the proportion of recombined vs. unrecombined substrates.

To enhance the orthogonality of recombinase systems for complex circuit design, multiple approaches can be employed. Engineering recombinase specificity through directed evolution of both the recombinase and its target sites enables creation of orthogonal pairs that do not cross-react [4]. Additionally, regulation of recombinase activity at specific sites using switchable transcription factors provides another layer of control for complex circuits [4].

Table 3: Research Reagents for Recombinase-Based Circuit Engineering

| Reagent/System | Type | Recognition Site | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cre-lox | Tyrosine recombinase | loxP | Gene knockout, excision, mammalian systems |

| Flp-FRT | Tyrosine recombinase | FRT | Similar to Cre-lox, yeast and mammalian systems |

| Bxb1 | Serine integrase | attB/attP | Unidirectional integration, memory devices |

| PhiC31 | Serine integrase | attB/attP | Large DNA integration, gene therapy |

| FimE | Tyrosine recombinase | Multiple sites | Bidirectional switching, bacterial circuits |

CRISPR-Based Systems

Molecular Mechanisms and System Classification

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) systems have revolutionized genetic engineering by providing RNA-programmable tools for DNA targeting. These systems originate from adaptive immune mechanisms in bacteria and archaea that prevent viral infection by recognizing and cleaving foreign DNA [5]. The core mechanism involves a Cas nuclease complex that uses guide RNA sequences to identify complementary DNA targets for cleavage or binding.

CRISPR systems are broadly classified into two classes based on their effector complex architecture. Class 1 systems (types I, III, and IV) utilize multi-subunit effector complexes, while Class 2 systems (types II, V, and VI) employ single protein effectors [6]. For genetic circuit applications, several Cas variants have been particularly impactful, each with distinct molecular mechanisms and applications.

Cas9, the pioneering CRISPR effector, is a type II system that creates double-strand breaks in target DNA through its HNH and RuvC nuclease domains [5]. The system requires both a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating RNA (tracrRNA), which can be fused into a single guide RNA (sgRNA) for simplicity [5]. Target recognition requires a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site, which varies between Cas9 orthologs.

Cas12 systems (type V) differ from Cas9 in their molecular architecture and cleavage mechanisms. Unlike Cas9, which cleaves using two distinct nuclease domains, Cas12 utilizes a single RuvC domain to generate staggered cuts in both DNA strands [5]. Additionally, upon binding to its target DNA, Cas12 exhibits collateral trans-cleavage activity, non-specifically degrading single-stranded DNA molecules in the vicinity [5]. This property has been harnessed for diagnostic applications like the DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter (DETECTR) system [5].

CRISPRi (CRISPR interference) systems utilize catalytically inactive Cas variants (dCas9, dCas12) that retain DNA-binding capability but lack nuclease activity [1]. These dead Cas proteins can be further fused to transcriptional repressor or activator domains to create programmable transcription factors that knock down or enhance gene expression without altering the DNA sequence [1].

Applications in Genetic Circuit Design

The programmability of CRISPR systems has enabled sophisticated genetic circuit designs with capabilities exceeding those of traditional protein-based regulators.

Complex Logic Operations: CRISPR-based circuits can implement Boolean logic gates by expressing multiple guide RNAs that target different promoter regions [1]. For example, a NOR gate can be constructed by designing a promoter with multiple gRNA binding sites, where binding of any dCas9-repressor complex inhibits transcription. More complex logic operations can be achieved by combining multiple gRNAs with different specificities and regulated expression.

Dynamic Control and Feedback Loops: The ability to rapidly produce guide RNAs enables dynamic control of circuit behavior. Inducible promoters can control gRNA expression, allowing external signals to modulate targeting specificity. Furthermore, circuits can incorporate feedback by designing gRNAs that target their own regulatory elements or those of other circuit components, creating oscillatory behaviors or homeostatic control systems.

Large-Scale DNA Engineering: CRISPR systems have been combined with recombinases and transposases for targeted integration of large DNA fragments. CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems enable RNA-guided insertion of genetic elements without introducing double-strand breaks [6]. Type I-F CAST systems can integrate donor sequences up to approximately 15.4 kb in prokaryotic hosts, while type V-K variants have accommodated inserts up to 30 kb [6]. These systems utilize the conserved DDE-family transposase TnsB, which catalyzes strand transfer during transposition, together with accessory factors TnsC and TniQ [6].

Epigenetic Regulation: Advanced CRISPR systems enable programmable epigenetic control through modifications of DNA bases and histones. The CRISPRoff/CRISPRon system combines dCas9 with either a DNA methyltransferase (DNMT3A/3L) and a transcriptional repressor for programmable epigenetic silencing (CRISPRoff) or with a demethylase (TET) to remove methylation marks (CRISPRon) [4]. This creates stable and heritable transcriptional states without altering the underlying DNA sequence.

Diagram 2: CRISPR-based epigenetic regulation circuit. Input signals induce guide RNA expression, which directs dCas9-effector fusion proteins to specific genomic loci, resulting in chromatin modifications that alter gene expression output.

Experimental Implementation of CRISPR Circuits

The implementation of CRISPR-based genetic circuits requires careful design and optimization. The following protocol outlines key steps for constructing and testing CRISPR circuits in mammalian cells.

CRISPR Circuit Implementation Protocol:

gRNA Design and Validation:

- Identify target sequences with appropriate PAM motifs (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9)

- Select targets with minimal off-potential using computational tools (CRISPOR, CHOPCHOP)

- Clone gRNA sequences into expression vectors with RNA Polymerase III promoters (U6, H1)

- Validate targeting efficiency using reporter assays with fluorescent proteins

Cas Protein Selection and Delivery:

- Choose appropriate Cas variant based on application: wild-type for cleavage, dCas9 for regulation, base editors for point mutations

- Express Cas proteins from constitutive or inducible promoters appropriate for the host system

- Consider codon optimization for the target organism

- Deliver components via lentiviral transduction, transfection, or other appropriate methods

Circuit Assembly and Testing:

- Assemble final circuit architecture with appropriate regulatory elements

- Transduce/transfect target cells and allow for stable integration if required

- Induce circuit operation with appropriate stimuli

- Measure outputs using fluorescence, sequencing, or other relevant assays

Optimization and Characterization:

- Titrate component expression levels to balance circuit function

- Assess dynamics through time-course measurements

- Evaluate specificity through RNA-seq or targeted sequencing

- Test circuit robustness across cell passages and environmental conditions

Table 4: Research Reagents for CRISPR-Based Circuit Engineering

| Reagent/System | Type | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Type II CRISPR | NGG PAM, high efficiency | Gene knockout, transcriptional regulation |

| dCas9-KRAB | CRISPRi | Fusion to KRAB repressor | Transcriptional repression |

| dCas9-VP64 | CRISPRa | Fusion to VP64 activator | Transcriptional activation |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Type V CRISPR | T-rich PAM, staggered cuts | Multiplexed targeting, diagnostics |

| Base Editors | CRISPR-derived | Fusion to deaminase domains | Point mutations without double-strand breaks |

| Prime Editors | CRISPR-derived | Reverse transcriptase fusion | Precise edits without donor templates |

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guidelines

Performance Metrics and Application Fit

Selecting the appropriate regulator class for a specific genetic circuit application requires careful consideration of performance characteristics, experimental constraints, and desired circuit behaviors. Each regulator class offers distinct advantages and limitations across key metrics.

Temporal Dynamics: DNA-binding proteins typically operate on timescales of minutes to hours, with response times influenced by protein expression and turnover rates [1]. CRISPR-based systems can exhibit faster response times when pre-expressed, as guide RNA binding can occur within minutes [5]. Invertases implement permanent changes, making them unsuitable for dynamic control but ideal for long-term state storage [4].

Orthogonality and Scalability: CRISPR systems offer superior scalability due to the ease of programming multiple guide RNAs with minimal cross-talk [1]. DNA-binding proteins require engineering of orthogonal DNA-binding domains, which has been achieved with libraries of zinc finger proteins and TALEs, though with greater design complexity [1]. Invertases exhibit high orthogonality when using diverse recombinase families, but the number of well-characterized orthogonal systems is limited [4].

Efficiency and Reliability: DNA-binding proteins generally show high efficiency in prokaryotic systems but can face challenges in eukaryotic contexts due to chromatin accessibility [7]. CRISPR systems can suffer from off-target effects, though high-fidelity variants have been developed to mitigate this issue [5]. Invertases typically exhibit high efficiency once recombination occurs, though the kinetics can be slow (2-6 hours) and may result in mixed populations when targeting multicopy plasmids [1].

Table 5: Comparative Analysis of Genetic Circuit Regulator Classes

| Parameter | DNA-Binding Proteins | Invertases/Recombinases | CRISPR-Based Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response Time | Minutes to hours | Slow (2-6 hours) | Minutes (if pre-expressed) |

| Persistence | Transient | Permanent | Transient to permanent |

| Orthogonality | Moderate (limited domains) | High within families | High (programmable guides) |

| Scalability | Moderate | Low to moderate | High |

| Efficiency | High in prokaryotes | High once recombination occurs | Variable, can have off-targets |

| Circuit Size | Small to medium | Small to medium | Small to large |

| Key Applications | Logic gates, oscillators | Memory, state switching | Complex logic, regulation, editing |

Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of genetic circuits requires attention to practical experimental factors beyond theoretical performance metrics.

Host System Compatibility: Prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems present different challenges for circuit implementation. DNA-binding proteins like TetR and LacI homologues function well in bacteria but require adaptation for eukaryotic use [1]. CRISPR systems show broad host compatibility but may require optimization of delivery methods and expression levels [5]. Invertases like Cre and Flp work across diverse systems, though efficiency can vary [4].

Resource Requirements: DNA-binding protein circuits typically require standard molecular biology resources with minimal specialized equipment. CRISPR systems may need additional validation for off-target effects through sequencing approaches. Invertase-based circuits require careful characterization of recombination efficiency and potential for mixed populations.

Design Complexity: DNA-binding protein circuits follow well-established design principles but can require balancing of expression levels for proper function [1]. CRISPR circuits offer programmability but need careful gRNA design and consideration of chromatin context in eukaryotes [5]. Invertase circuits have straightforward design but limited operational modes primarily focused on state changes [4].

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of genetic circuit design continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future developments in regulator engineering. Integration of multiple regulator classes within single circuits leverages the strengths of each approach, such as using CRISPR systems for dynamic control alongside recombinases for permanent state storage [4]. Machine learning-assisted design is increasingly applied to predict protein-DNA binding specificities and optimize guide RNA designs, reducing experimental iteration [10]. Portable and resource-compatible applications are driving the development of CRISPR-based diagnostics that function in low-resource settings, addressing challenges like enzymatic stability in non-ideal conditions [5].

The convergence of these technologies points toward a future where genetic circuits become increasingly sophisticated, reliable, and applicable to real-world challenges in therapeutics, bioproduction, and environmental sensing. As our understanding of these fundamental regulator classes deepens, so too does our capacity to program biological systems with precision and predictability.

The engineering of Boolean logic gates in biological systems represents a foundational pillar of synthetic biology, enabling the reprogramming of cellular behavior for advanced applications in biosensing, biocomputation, and therapeutic intervention. Biological Boolean gates are computational modules built from biomolecular components—DNA, RNA, proteins, and small molecules—that process one or more input signals to produce a discrete output according to the principles of Boolean algebra. Unlike their silicon-based counterparts that use electrons as information carriers, biological logic gates utilize diverse signaling molecules including ions, photons, and redox species, offering the distinct advantage of operating within aqueous and physiological environments [11]. Since the development of the first molecular logic gate, the field has evolved from simple single-gate implementations to sophisticated circuits capable of complex decision-making, pushing the boundaries of what is possible in cellular engineering [11].

The implementation of Boolean logic in biological systems faces unique challenges compared to electronic systems. Biological components are not strictly modular or composable, and their performance is influenced by cellular context, resource limitations, and stochastic molecular interactions [12]. Despite these challenges, significant progress has been made in developing standardized frameworks for designing, modeling, and implementing genetic circuits. This guide examines the core principles, implementation platforms, and experimental methodologies for constructing Boolean gates in biological systems, providing researchers with the technical foundation needed to advance the field of genetic circuit design.

Implementation Platforms and Architectures

Transcriptional Programming with Synthetic Transcription Factors

Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) represents an advanced architecture for implementing Boolean logic in living cells. This approach utilizes synthetic transcription factors (TFs) and corresponding synthetic promoters to achieve circuit compression—designing circuits with fewer genetic parts while maintaining complex functionality. T-Pro employs engineered repressor and anti-repressor TFs that coordinate binding to cognate synthetic promoters, eliminating the need for inversion-based logic implementations that require additional genetic components [12]. A significant advantage of T-Pro is its scalability; researchers have successfully expanded this platform from 2-input to 3-input Boolean logic, enabling the implementation of all 256 possible 3-input Boolean functions [12].

The T-Pro architecture relies on the development of orthogonal sets of synthetic TFs responsive to different input signals. For instance, a complete 3-input T-Pro system utilizes TF sets responsive to IPTG, D-ribose, and cellobiose, with each set comprising both repressor and anti-repressor variants [12]. These synthetic TFs are engineered through systematic approaches including site-saturation mutagenesis and error-prone PCR to optimize dynamic range and orthogonality. The corresponding synthetic promoters feature tandem operator designs that enable precise logical operations through coordinated TF binding, substantially reducing the genetic footprint compared to traditional inverter-based circuits [12].

Recombinase-Based Logic and Memory Systems

Site-specific recombinases provide a powerful mechanism for implementing Boolean logic with built-in memory functions. These systems utilize bacteriophage-derived integrases such as Bxb1 and TP901-1 that catalyze unidirectional DNA recombination events in response to input signals [13]. The key advantage of recombinase-based systems is their ability to create permanent, DNA-encoded memory of transient chemical events without ongoing energy expenditure [13]. This approach has been successfully adapted for cell-free environments through the Cell-free Recombinase-Integrated Boolean Output System (CRIBOS), enabling the construction of multi-input-multi-output circuits including 2-input-2-output genetic circuits and a 2-input-4-output decoder [14].

Recombinase-based temporal logic gates can process information about the order, timing, and duration of input signals—capabilities beyond simple presence/absence detection [13]. Strategic interleaving of recombinase recognition sites (attB and attP) creates mutually exclusive recombination outcomes that encode temporal relationships between inputs. For example, a two-integrase temporal logic gate with nested attachment sites can differentiate between five distinct event sequences: no input, inducer A only, inducer B only, A followed by B, and B followed by A [13]. The irreversibility of recombination creates a permanent genetic record that can be read via fluorescent reporters or DNA sequencing long after the triggering events have occurred.

Nucleic Acid-Based Logic Toolkits

Nucleic acids provide a particularly versatile substrate for implementing Boolean logic gates due to their predictable Watson-Crick base pairing and well-characterized enzymatic processing. DNA-based logic gates utilize strand displacement reactions, hybridization events, and enzymatic modifications to perform computations [11]. These systems can be designed to respond to various molecular inputs including nucleic acid sequences, proteins, small molecules, and ions, producing outputs typically measured through fluorescent, colorimetric, or electrochemical signals [11].

The programmability of nucleic acid interactions enables sophisticated circuit architectures including combinatorial logic, sequential logic, and feedback systems. DNA-based gates demonstrate excellent biocompatibility and have been successfully implemented in vitro, on surfaces, and within living cells for applications in genetic analysis, cancer diagnostics, pathogen identification, and point-of-care testing [11]. Recent advances have integrated nucleic acid logic with artificial intelligence-powered detection platforms and smartphone-based readout systems, enhancing their potential for real-world applications [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Biological Boolean Gate Implementation Platforms

| Platform | Core Components | Key Advantages | Complexity Demonstrated | Memory Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) | Synthetic transcription factors, synthetic promoters | Circuit compression, predictable performance, reduced burden | All 3-input Boolean functions (256 operations) | Limited without additional components |

| Recombinase-Based Systems | Serine integrases, recognition sites, reporter genes | Permanent DNA memory, temporal logic, low energy maintenance | 2-input temporal logic with timing detection | Stable, DNA-encoded memory |

| Nucleic Acid-Based Systems | DNA/RNA strands, enzymes, fluorescent reporters | Programmability, biocompatibility, diverse readout methods | Combinatorial and sequential logic | Through stable complex formation |

| Cell-Free Systems (CRIBOS) | Cell-free extracts, DNA templates, recombinases | Portability, stability, minimal resource requirements | 2-input-4-output decoder circuits | 4+ months on paper-based storage |

| 2-Bromo-7-methoxyquinoline | 2-Bromo-7-methoxyquinoline, MF:C10H8BrNO, MW:238.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| (S)-(1-Methoxyethyl)benzene | (S)-(1-Methoxyethyl)benzene, MF:C9H12O, MW:136.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Design and Workflow

Quantitative Design and Modeling Framework

The successful implementation of biological Boolean gates requires integrated wetware and software approaches that enable predictive design. A key challenge in genetic circuit engineering is the limited modularity of biological parts and the increasing metabolic burden as circuit complexity grows [12]. Advanced modeling frameworks address these challenges by combining algorithmic enumeration of possible circuit configurations with quantitative performance prediction.

For T-Pro circuits, researchers have developed an algorithmic enumeration method that models circuits as directed acyclic graphs and systematically enumerates designs in order of increasing complexity [12]. This approach guarantees identification of the most compressed (minimal part) circuit for a given truth table from a search space exceeding 100 trillion possible configurations [12]. The software workflow incorporates genetic context effects and performance setpoints to generate quantitative predictions with average errors below 1.4-fold across multiple test cases [12]. This predictive design capability extends to metabolic engineering applications, enabling precise control of flux through biosynthetic pathways.

Network-based approaches provide additional visualization and analysis capabilities for genetic circuit design. By transforming circuit designs into dynamic network structures, researchers can create interactive visualizations with scalable abstraction levels [15]. These networks represent biological parts as nodes and their interactions as edges, with semantic labeling of relationship types (activation, repression, etc.). The network approach enables automatic generation of tailored visualizations, application of graph theory analysis methods, and coupling of circuit designs with related networks such as metabolic pathways [15].

Diagram 1: Integrated software-wetware workflow for predictive genetic circuit design

Implementation Protocols for Key Gate Architectures

Transcriptional Programming Implementation

The experimental implementation of T-Pro circuits begins with the engineering of synthetic transcription factors. For a complete 3-input Boolean system, develop orthogonal TF sets responsive to distinct inducers (e.g., IPTG, D-ribose, cellobiose) through the following protocol:

TF Engineering: Start with native repressor scaffolds (e.g., LacI, RhaRS, CelR). Generate super-repressor variants through site-saturation mutagenesis at critical amino acid positions to create ligand-insensitive DNA binding variants [12].

Anti-Repressor Development: Subject super-repressor templates to error-prone PCR at low mutation rates to generate variant libraries. Screen ~10⸠variants using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to identify anti-repressors that activate transcription in the presence of ligand [12].

Alternate DNA Recognition Engineering: Equip each repressor and anti-repressor core with 4-5 alternate DNA recognition domains to create orthogonal DNA binding specificities. Verify orthogonality and performance through flow cytometry analysis of reporter strains [12].

Synthetic Promoter Design: Construct synthetic promoters with tandem operator sites matching the DNA recognition domains of the engineered TFs. Position operators to enable cooperative binding and precise logical operations [12].

Circuit Assembly: Clone genetic circuits using standardized assembly methods, placing synthetic promoters upstream of output genes (fluorescent proteins, enzymes). Transform constructs into host cells (typically E. coli) for characterization [12].

Recombinase-Based Logic Gate Construction

For implementing temporal logic gates with serine integrases, follow this experimental protocol:

DNA Architecture Design: Design the DNA module with strategically interleaved integrase recognition sites (attB and attP). For a two-input temporal gate, nest the attB site of integrase B within the attP site of integrase A to ensure mutually exclusive recombination outcomes [13].

Reporter Integration: Incorporate fluorescent protein genes (e.g., mKate2-RFP, superfolder-GFP) as outputs, with expression dependent on recombination-mediated configuration changes. Include a strong constitutive promoter and terminator sequences to control initial expression state [13].

Chromosomal Integration: Integrate the logic gate as a single copy into the host chromosome using established integration systems (e.g., attB/attP phage integration systems for E. coli) [13]. Single-copy integration ensures digital, stochastic responses and reduces variability from copy number effects.

Integrase Expression: Place each integrase gene under the control of inducible promoters responsive to specific chemical inputs. Use well-characterized inducible systems (e.g., arabinose-inducible, aTc-inducible) with minimal cross-talk [13].

Temporal Induction: Expose cells to input inducers in specific sequences, orders, and durations. Use pulse treatments of varying lengths separated by wash steps to characterize temporal response properties [13].

Population Analysis: Analyze population-level responses using flow cytometry to quantify distributions across different genetic states. Model single-cell stochasticity using Markov models and Gillespie algorithm simulations [13].

Diagram 2: Recombinase-based temporal logic gate pathway showing DNA state transitions

Performance Metrics and Characterization

Quantitative Assessment of Circuit Performance

Rigorous characterization of biological Boolean gates requires quantification of multiple performance parameters across different operating conditions. The table below summarizes key metrics and their measurement methods for evaluating genetic circuit performance:

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Biological Boolean Gates

| Performance Metric | Definition | Measurement Method | Target Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Ratio between ON and OFF state expression levels | Flow cytometry of output reporter | >100-fold |

| Response Time | Time to reach 50% of maximum output after induction | Time-course measurements with plate reader | <60 minutes |

| Input Sensitivity | Minimum input concentration that produces detectable output | Titration experiments with varying inducer concentrations | Below physiological relevant levels |

| Orthogonality | Specificity of components with minimal cross-talk | Testing all non-cognate component interactions | <5% cross-activation |

| Cellular Burden | Impact on host cell growth and metabolism | Growth curve analysis, RNA sequencing | <20% growth reduction |

| Noise | Cell-to-cell variability in output expression | Coefficient of variation from flow cytometry | <30% of mean |

| Stability | Consistency of performance over multiple generations | Long-term culturing with periodic measurement | <10% performance loss over 50 generations |

For recombinase-based systems with memory functions, additional metrics include recombination efficiency (percentage of cells that undergo stable recombination after induction), memory stability (persistence of state over generations without selection), and temporal resolution (minimum pulse duration that produces detectable recombination) [13]. These systems typically achieve recombination efficiencies of 70-95% after full induction, with stable memory maintenance for hundreds of generations [13].

Comparative Analysis of Gate Performance

Different Boolean gate architectures demonstrate distinct performance characteristics. Transcriptional Programming circuits achieve significant compression, with 3-input circuits being approximately 4-times smaller than equivalent canonical inverter-based designs [12]. These circuits show quantitative prediction errors below 1.4-fold across multiple test cases, enabling precise forward engineering of circuit behavior [12].

Cell-free systems like CRIBOS offer exceptional stability, with paper-based implementations maintaining functionality for over 4 months with minimal resources and energy costs [14]. This makes them particularly suitable for portable biosensing applications and educational toolkits where refrigeration and sophisticated laboratory equipment may be unavailable.

Nucleic acid-based systems excel in biocompatibility and programmability, operating effectively in complex biological environments including within living cells [11]. While generally slower than transcriptional systems due to diffusion-limited reaction kinetics, DNA-based gates can implement sophisticated computational functions including fuzzy logic and reversible operations that are challenging with protein-based systems [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of biological Boolean gates requires carefully selected research reagents and molecular tools. The following table details essential components and their functions for constructing and testing genetic circuits:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biological Boolean Gate Implementation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Circuit Implementation | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factors | Engineered LacI, RhaRS, CelR variants with ADR domains | Core computing elements that process inputs and regulate outputs | Orthogonal DNA binding, tunable dynamic range, ligand specificity |

| Synthetic Promoters | Tandem operator promoters with specific spacing | Interface between TFs and output genes, determine logic function | Controlled leakiness, appropriate strength, modular architecture |

| Site-Specific Recombinases | Bxb1, TP901-1, ΦC31 integrases | Implement irreversible state changes and memory functions | High efficiency, orthogonality, unidirectional activity |

| Reporter Proteins | GFP, RFP, mKate2, luciferase | Quantitative readout of circuit states and activities | Brightness, stability, minimal metabolic burden |

| Inducer Molecules | IPTG, arabinose, aTc, cellobiose | Chemical inputs that trigger circuit activation | Cell permeability, specificity, minimal side effects |

| Host Strains | E. coli MG1655, DH10B, BL21 | Chassis for circuit implementation and testing | Defined genetic background, compatibility with expression systems |

| Assembly Systems | Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly, BioBricks | Physical construction of genetic circuits | High efficiency, standardization, modularity |

| Characterization Tools | Flow cytometer, plate reader, sequencing | Quantitative measurement of circuit performance | Sensitivity, throughput, single-cell resolution |

Additional specialized reagents include anti-repressor variants for T-Pro circuits [12], orthogonal integrase pairs for recombinase systems [13], and modified nucleotide analogs for nucleic acid-based gates [11]. The selection of appropriate reagents depends on the specific implementation platform, desired circuit complexity, and intended application environment.

Future Directions and Applications

The implementation of Boolean gates in biological systems continues to evolve toward greater complexity, reliability, and real-world applicability. Current research focuses on enhancing circuit predictability through improved modeling approaches that account for context effects and resource competition [12]. The development of additional orthogonal component sets will expand the computational capacity of biological systems, enabling more sophisticated decision-making circuits.

Applications in biosensing represent a near-term implementation, where biological Boolean gates can process multiple environmental signals to make diagnostic decisions. These systems show particular promise for medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and biomanufacturing control [11]. The integration of biological logic gates with electronic interfaces through biohybrid systems creates opportunities for seamless communication between biological and computational domains.

Advanced memory systems based on recombinase-mediated DNA editing enable long-term environmental monitoring and cellular history recording [13]. As single-cell sequencing technologies advance, the readout of complex biological computations stored in DNA will become increasingly accessible, opening new possibilities for understanding and engineering cellular behaviors.

The continuing convergence of biological Boolean gates with artificial intelligence design tools, automated assembly platforms, and microfluidic characterization systems promises to accelerate the development cycle from concept to functional implementation. These advances will solidify the role of biological computation as a transformative technology with broad applications across biotechnology, medicine, and bioengineering.

The engineering of living cells to perform predefined functions represents a frontier in biotechnology, with transformative potential for therapeutics, biosensing, and biomaterial production. Central to this endeavor is the design of genetic circuits—networks of interacting genes and regulatory elements that process cellular information and direct complex biological behaviors. The design of these circuits requires a deep understanding of dynamic behavior and network topology to achieve desired functions such as switching, memory, and oscillation [1]. This technical guide examines two fundamental classes of dynamic behavior in genetic circuits: negative autoregulation, which enhances response kinetics, and oscillators, which generate periodic biological signals. These design principles form the core of sophisticated genetic programming, enabling researchers to move beyond simple gene expression toward complex temporal control of cellular functions [1] [16].

The field has evolved from constructing simple switches and oscillators to implementing increasingly complex circuits that perform computations, process signals, and control metabolic fluxes [1] [17]. This progression has been enabled by the development of diverse regulatory components, including DNA-binding proteins, invertases, and CRISPR-based systems, each offering distinct advantages for circuit design [1]. A critical insight from both natural and synthetic systems is that the dynamic performance of genetic circuits depends not only on their components but also on their network architecture—the specific arrangement of regulatory connections that determines systems-level behavior [16].

Core Regulatory Components in Genetic Circuit Design

Classification of Circuit Elements

Genetic circuits are constructed from biological parts that can be categorized based on their functional role in information processing. The table below summarizes the primary classes of regulators used in synthetic genetic circuits, their mechanisms of action, and their typical applications.

Table 1: Key Regulator Classes in Genetic Circuit Design

| Regulator Class | Mechanism of Action | Dynamic Capabilities | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Proteins (Repressors/Activators) | Bind operator sites to block/recruit RNA polymerase [1] | Switches, logic gates, analog computing, oscillators [1] | Repressilator oscillator [18], toggle switches [1] |

| Invertases (Recombinases) | Catalyze irreversible DNA inversion between specific sites [1] | Memory, counters, sequential logic [1] | Binary memory elements, state machines [1] |

| CRISPRi/a | dCas9-guide RNA complexes block/activate transcription [1] | Logic gates, dynamic regulation [1] | Tunable repression, large-scale circuits [1] |

| Transcriptional Anti-Repressors | Interfere with repressor function [17] | NOT logic, signal inversion [17] | Engineered gene regulation [17] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The design-build-test-learn cycle in genetic circuit engineering relies on a standardized toolkit of biological parts and experimental reagents. The following table catalogues essential materials referenced in foundational studies of circuit dynamics.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Circuit Engineering

| Reagent / Biological Part | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| PLtetO-1 Promoter | Tetracycline-responsive promoter [19] | Inducible expression in negative autoregulation studies [19] |

| GFPmut3 Reporter | Fast-folding green fluorescent protein variant [19] | Real-time monitoring of protein expression dynamics [19] |

| TetR Repressor | Tetracycline-binding transcription factor [19] | Core repressor in synthetic circuits [19] |

| SC101 Origin | Low-copy-number plasmid origin [19] | Maintains consistent plasmid copy number [19] |

| LuxI/LuxR QS System | Acyl-homoserine lactone-based cell-cell communication [20] | Population synchronization in oscillators [20] |

| Serine Integrases | Unidirectional DNA recombinases [1] | Binary memory storage, logic gates [1] |

| Degradation Tags (LVA, AAV) | Signal sequences for protein degradation [20] | Tuning protein half-life in oscillators [20] |

| Guide RNA Libraries | Target-determining component of CRISPR systems [1] | Multiplexed regulation in CRISPRi/a circuits [1] |

| 4-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)butanal | 4-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)butanal|High-Purity Reference Standard | 4-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)butanal: A high-purity compound for research use only (RUO). Explore its applications in chemical synthesis. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Leucylasparagine | Leucylasparagine, MF:C10H19N3O4, MW:245.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Negative Autoregulation: Principle and Functional Advantages

Network Architecture and Mathematical Basis

Negative autoregulation (NAR) represents a fundamental network motif in which a transcription factor represses its own promoter [21] [19]. This self-inhibitory architecture appears in over 40% of known Escherichia coli transcription factors, suggesting strong evolutionary selection for its functional benefits [19]. The NAR motif significantly accelerates the system's response time—the delay between induction and reaching half-maximal protein concentration—compared to simple, unregulated transcription units [21] [19].

The kinetic advantage of NAR circuits can be understood through mathematical modeling. In a simple transcription unit without regulation, protein concentration ( P ) approaches steady state ( P_{st} ) with first-order kinetics characterized by the cell division time ( T ), resulting in a rise-time of approximately one cell cycle [19]. In contrast, an NAR circuit follows different dynamics described by the differential equation:

[ \frac{dP}{dt} = \frac{\beta}{1 + (P/K)^n} - \alpha P ]

where ( \beta ) represents the maximal expression rate, ( K ) is the repression coefficient, ( n ) is the Hill coefficient quantifying cooperativity, and ( \alpha ) is the degradation rate [19]. The negative feedback enables a rapid initial production phase when ( P ) is low, followed by slowing as ( P ) approaches steady state. This dynamic profile reduces the rise-time to approximately one-fifth of a cell cycle while maintaining the same steady-state expression level [21] [19].

Figure 1: Negative Autoregulation Motif. A transcription factor represses its own promoter, creating a self-inhibitory feedback loop that speeds response times.

Experimental Protocol: Measuring NAR Response Times

Circuit Design and Assembly

- Construct Design: Create two plasmid systems for comparative analysis [19]:

- Non-autoregulatory reference circuit: Place a repressor protein (e.g., TetR) under control of an inducible promoter (e.g., PLlacO1) on a low-copy plasmid with SC101 origin. A reporter gene (e.g., gfpmut3) under control of a promoter regulated by the repressor (e.g., PLtetO1) should be placed on a separate plasmid [19].

- NAR circuit: Modify the repressor gene to be under control of its own repressible promoter (e.g., PLtetO1 driving tetR expression) [19].

- Genetic Context: Use consistent plasmid backbones, origins of replication, and antibiotic resistance markers to ensure comparable genetic context [19].

- Host Strain: Use E. coli Dh5α or other appropriate strains that provide any necessary genetic background (e.g., lacI expression for PLlacO1 regulation) [19].

Cultivation and Measurement

- Culture Conditions: Grow overnight cultures in appropriate medium with selective antibiotics. Dilute fresh cultures 1:100 and grow to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.3-0.5) [19].

- Circuit Induction: Add inducer molecule (e.g., IPTG for PLlacO1 or aTc for PLtetO1) at optimized concentration to initiate expression [19].

- Time-Series Sampling: Collect samples at 5-10 minute intervals following induction for 2-3 hours [19].

- Fluorescence Measurement: Analyze GFP fluorescence using flow cytometry or plate readers, normalizing to cell density and autofluorescence [19].

Data Analysis

- Response Time Calculation: Determine the time point at which the protein concentration reaches half of its maximum steady-state value (t½) for both circuits [19].

- Normalization: Normalize fluorescence trajectories to their respective steady-state levels for direct comparison of response kinetics [19].

- Statistical Analysis: Perform multiple biological replicates (n ≥ 3) to calculate mean response times and standard errors [19].

Quantitative Analysis of NAR Performance

The kinetic benefits of negative autoregulation have been quantitatively demonstrated in synthetic gene circuits. The following table summarizes experimental findings comparing the response times of simple regulation versus NAR circuits.

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Circuit Response Times

| Circuit Architecture | Theoretical Rise-Time | Experimental Rise-Time | Steady-State Level | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Regulation | ~1 cell cycle (100 min) | ~100 min [19] | Pst | [19] |

| Negative Autoregulation | ~1/5 cell cycle (20 min) | ~20 min [19] | Pst | [19] |

| Confinement without NAR | N/A | Severely suppressed in small compartments | Reduced in small compartments | [22] |

| Confinement with NAR | N/A | Mitigates size-induced repression | Maintained across compartment sizes | [22] |

Beyond acceleration of response times, NAR provides additional functional benefits including reduced cell-to-cell variability at steady state, increased robustness to mutations, and mitigation of size-dependent expression effects in confined compartments [22] [19]. In confined environments where excluded volume effects suppress gene expression, NAR counterintuitively restores normal size-scaling relationships by compensating for physical repression through its regulatory function [22].

Biological Oscillators: Design Principles and Implementation

Fundamental Requirements for Oscillatory Dynamics

Biological oscillators generate periodic fluctuations in molecular concentrations, enabling temporal organization of cellular processes from circadian rhythms to cell cycle control [16]. Synthetic oscillators implement simplified versions of these natural timing mechanisms, revealing core design principles essential for robust cyclic behavior. The fundamental requirement for oscillation is a negative feedback loop with sufficient time delay and nonlinearity to prevent the system from settling into a stable steady state [16] [18].

From theoretical analysis, three essential conditions must be satisfied for sustained oscillations:

- Negative Feedback: A system component that inhibits its own production through intermediate steps [16] [18].

- Time Delay: Significant delay between the initiation and completion of the feedback process, typically achieved through multi-step biochemical processes (transcription, translation, protein maturation) or explicit delay mechanisms [16].

- Nonlinear Response: A sufficiently steep, nonlinear input-output response in the feedback loop, often achieved through cooperative binding (Hill coefficient n > 1) or ultrasensitivity [16].

The simplest theoretical oscillator, the Goodwin model, consists of a single gene whose product represses its own transcription after undergoing multiple processing steps that introduce time delays [16]. However, most practical synthetic oscillators employ multiple interconnected genes that create the necessary feedback architecture with adequate delay.

Figure 2: Repressilator Architecture. A three-gene ring oscillator where each gene represses the next, creating a delayed negative feedback loop.

Experimental Protocol: Constructing and Testing Synthetic Oscillators

Circuit Design and Optimization

- Topology Selection: Choose an oscillator architecture appropriate for the application:

- Repressilator: Three-gene ring topology with odd-numbered repression cascade [18].

- Dual-Feedback Oscillator: Combines negative and positive feedback for enhanced robustness [16] [20].

- QS-Protease Oscillator: Incorporates quorum sensing and protease elements for population-level synchronization [20].

- Component Selection: Select orthogonal repressors/activators with minimal crosstalk (e.g., TetR, LacI, CI) [1] [18].

- Time Delay Engineering: Incorporate multiple transcriptional/translational steps or protein maturation sequences to increase feedback delay.

- Degradation Tags: Include degradation tags (LVA, AAV) on repressor and reporter proteins to control half-lives and tune oscillation period [20].

Prototyping in Cell-Free Systems

- Cell-Free Transcription-Translation: Use E. coli cell extracts in microfluidic devices for rapid prototyping [18].

- Parameter Screening: Systematically vary component concentrations (DNA templates, nucleotides, amino acids) to identify oscillatory regimes [18].

- Real-Time Monitoring: Use fluorescent reporters (GFP, YFP, RFP) to track dynamics with time-lapse microscopy [18].

Implementation in Living Cells

- Plasmid Construction: Assemble oscillator circuits on low-copy plasmids with orthogonal origins and antibiotic resistance [18] [20].

- Transfer to Cellular Environment: Transform assembled circuits into appropriate host strains (e.g., E. coli MG1655 for repressilator) [18].

- Cultivation Under Controlled Conditions: Grow cells in microfluidic devices or well-plates with constant environmental conditions (temperature, nutrient supply) [18] [20].

- Time-Lapse Microscopy: Monitor fluorescence in single cells or populations at 5-20 minute intervals over multiple cycles [18] [20].

Data Analysis and Characterization

- Oscillation Detection: Apply Fourier analysis or peak-finding algorithms to identify periodic signals [18].

- Parameter Extraction: Quantify period, amplitude, phase, and damping constant from fluorescence trajectories [18].

- Noise Analysis: Calculate coefficient of variation to assess robustness of oscillations [18].

Advanced Oscillator Architectures and Applications

More sophisticated oscillator designs incorporate additional regulatory layers to enhance functionality and enable operation in diverse environments. The QS-protease oscillator represents an advanced architecture that achieves population-level synchronization in non-microfluidic environments through quorum sensing coupling [20]. This circuit employs the Esa quorum sensing system, where the EsaR transcription factor activates its own synthase (EsaI) and reporter genes while repressing expression of a lactonase (AiiA) that degrades the signaling molecule [20]. When the population reaches a critical density, accumulated signal molecule binds EsaR, shutting off synthase expression and activating lactonase production, thereby resetting the system for the next cycle [20].

Table 4: Comparison of Synthetic Oscillator Architectures

| Oscillator Type | Core Architecture | Period Range | Synchronization Mechanism | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repressilator | 3-gene repressive ring [18] | ~60-180 minutes [18] | Reduced noise design [20] | Fundamental studies, pattern formation [18] |

| Dual-Feedback Oscillator | Combined positive+negative feedback [16] | Tunable through inducer levels [16] | Microfluidic control [16] | Metabolic engineering, bioproduction [16] |

| QS-Protease Oscillator | QS signaling + protease regulation [20] | Several hours [20] | Quorum sensing coupling [20] | Large-scale cultures, potential therapeutics [20] |

| Goodwin Oscillator | Single-gene negative feedback [16] | Model-dependent | Not inherently synchronized | Theoretical studies [16] |

Recent innovations have demonstrated oscillators functioning in non-microfluidic environments without frequent dilution or inducer addition, significantly expanding their practical applications [20]. These systems maintain stable oscillations in culture volumes from 1 mL to 400 mL, enabling potential uses in bioproduction, therapeutics, and environmental sensing [20]. The integration of post-translational regulation through orthogonal proteases provides additional timing control and dynamic range expansion beyond purely transcriptional circuits [20].

The principles of negative autoregulation and oscillator design represent foundational concepts in the hierarchical organization of genetic circuit engineering. These dynamic modules function as core components in larger genetic programs, enabling temporal control of metabolic pathways, programmed differentiation sequences, and environment-responsive therapeutic systems [1] [17]. The progressive refinement of these designs—from initial demonstration of function to optimization for robustness, tunability, and context independence—exemplifies the engineering approach central to synthetic biology [1] [17].