Extending Dynamic Range in Biosensors: Protein Engineering Strategies for Precision Diagnostics and Biomanufacturing

This article explores the critical challenge of the limited dynamic range in protein-based biosensors and details how advanced protein engineering strategies are providing solutions.

Extending Dynamic Range in Biosensors: Protein Engineering Strategies for Precision Diagnostics and Biomanufacturing

Abstract

This article explores the critical challenge of the limited dynamic range in protein-based biosensors and details how advanced protein engineering strategies are providing solutions. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of biosensor dynamic range, the inherent limitations of single-site binding, and the innovative methodologies—from structure-switching aptamers to engineered transcription factors like CaiF—that are expanding detection limits by several orders of magnitude. The content further addresses troubleshooting for common optimization hurdles, comparative analyses of different engineering approaches, and validates these advancements with real-world applications in metabolic engineering, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring, providing a comprehensive roadmap for developing next-generation, high-performance biosensors.

The Dynamic Range Challenge: Why 81-Fold Isn't Enough for Modern Biosensing

Defining Dynamic Range, Operating Range, and Key Performance Metrics in Biosensing

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center provides clear answers and methodologies for researchers working on extending the dynamic range of biosensors via protein engineering.

FAQ 1: What is the difference between "Dynamic Range" and "Operating Range"?

These two terms are often used interchangeably, but they describe distinct concepts in biosensor characterization.

- Dynamic Range is the span between the minimal and maximal detectable signal or analyte concentration. It defines the entire concentration interval over which the biosensor responds, though not necessarily in a linear or optimally precise manner [1].

- Operating Range (also referred to as the Analytical Range) is the specific concentration interval between the upper and lower limits where the sensor has been demonstrated to be precise and accurate. The lower end is typically defined by the Limit of Quantification (LoQ), where the signal is ten times greater than the noise [2].

Troubleshooting Tip: If your biosensor's data is noisy or imprecise within a specific portion of the dynamic range, you are likely operating outside the ideal operating range. Focus on improving the signal-to-noise ratio or recalibrating for that specific concentration window.

FAQ 2: Why is the dynamic range of my biosensor limited, and how can protein engineering help?

A fundamental limitation of biological recognition is the physics of single-site binding, which produces a hyperbolic dose-response curve with a fixed useful dynamic range spanning only an 81-fold change in analyte concentration [3]. This is often insufficient for applications like monitoring viral loads or drug concentrations, which can vary over several orders of magnitude.

Protein engineering provides powerful solutions to overcome this inherent limitation:

- Strategy 1: Extending Dynamic Range. By generating a set of receptor variants (e.g., engineered transcription factors or structure-switching proteins) that display similar specificity but span a wide range of target affinities, you can combine them. When these variants are mixed in optimized ratios, their individual hyperbolic responses merge to create a single, log-linear response over several orders of magnitude. Research has demonstrated the creation of biosensors with a log-linear dynamic range extended to over 900,000-fold using this method [3].

- Strategy 2: Directed Evolution. Computational design and high-throughput screening can be used to create transcription factor variants with altered response profiles. For instance, one study successfully engineered a transcription factor-based biosensor for l-carnitine, resulting in a variant with a 1000-fold wider response range and a 3.3-fold higher output signal [4].

FAQ 3: How do I define the key performance metrics for my newly engineered biosensor?

A robust biosensor is characterized by a set of static and dynamic performance metrics. The following table summarizes the most critical parameters you need to define and optimize.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Biosensors

| Metric | Definition | Importance & Ideal Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | The span between the minimum and maximum detectable analyte concentration [1]. | Must be suited to the application (e.g., clinical range of the target analyte). |

| Sensitivity | The change in the biosensor's signal per unit change in analyte concentration [2]. | A higher sensitivity allows for the detection of smaller concentration changes. |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from background noise (typically Signal/Noise > 3) [2]. | Crucial for detecting trace amounts of an analyte in early disease diagnosis. |

| Selectivity/Specificity | Selectivity: The ability to differentiate analytes in a mixture from each other. Specificity: The ability to assess an exact analyte in a mixture [2]. | High selectivity/specificity minimizes false positives from interfering substances in complex samples like blood or serum. |

| Response Time (T90) | The time it takes for the sensor output to reach 90% of its new stable signal after a change in analyte concentration [2]. | Essential for real-time monitoring and point-of-care applications. A shorter T90 is generally better. |

| Reproducibility | The ability of the biosensor to generate identical responses for a duplicated experimental setup [5]. | High reproducibility ensures reliability and robustness of the data across different batches and users. |

FAQ 4: My biosensor has a good LoD but a narrow dynamic range. What experimental approaches can I take to broaden it?

Here is a detailed methodology for a protein engineering-based approach to extend dynamic range, based on proven research.

Experimental Protocol: Extending Dynamic Range via Affinity-Modulated Receptor Mixtures

Objective: To create a biosensor with a log-linear dynamic range spanning several orders of magnitude by combining affinity-diverse receptor variants.

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 2: Essential Materials for Dynamic Range Extension Experiments

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Structure-Switching Receptor Scaffold (e.g., engineered molecular beacons, transcription factors) | The core bioreceptor platform whose "off-state" stability can be tuned to generate affinity variants without altering target specificity [3]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | To introduce specific mutations that stabilize or destabilize the non-binding conformation of the receptor, creating a library of variants. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) Instrument | For label-free characterization of the binding affinity (Kd) and kinetics of each receptor variant [6]. |

| Microplate Reader (Fluorescence/Luminescence) | For high-throughput screening of variant libraries and measuring the dose-response curves of individual variants and their mixtures. |

| Algorithm for Simulation & Optimization | To simulate dose-response curves of different variant mixtures and determine the optimal ratios that maximize log-linearity [3]. |

Methodology:

- Generate Receptor Variants: Use rational design (e.g., alanine scanning, computational modeling of DNA binding sites) or directed evolution on your protein-based biosensor (e.g., a transcription factor) to create a library of variants [4]. The goal is to produce receptors with a wide range of dissociation constants (Kd) while maintaining high target specificity.

- Characterize Individual Variants: Express and purify each variant. Measure the dose-response curve for each one to determine its affinity (Kd), dynamic range, and signal gain. Confirm that all variants maintain specificity for the target analyte [3].

- Simulate Mixture Responses: Using computational simulations, model the combined output signal of mixtures containing two or more of your characterized variants. The simulation will help identify which variants to combine and in what ratios to achieve the widest possible log-linear response. Research indicates that combining two receptors with a 100-fold difference in affinity, mixed in non-equimolar ratios, can effectively extend the dynamic range [3].

- Validate Optimized Mixture: Physically mix the selected receptor variants in the optimized ratios predicted by your simulation. Measure the dose-response curve of the mixture. The resulting curve should show a significantly extended log-linear dynamic range compared to any single variant.

- Verify Specificity: Confirm that the extended-range biosensor maintains high specificity across the entire new dynamic range by testing against potential interfering molecules [3].

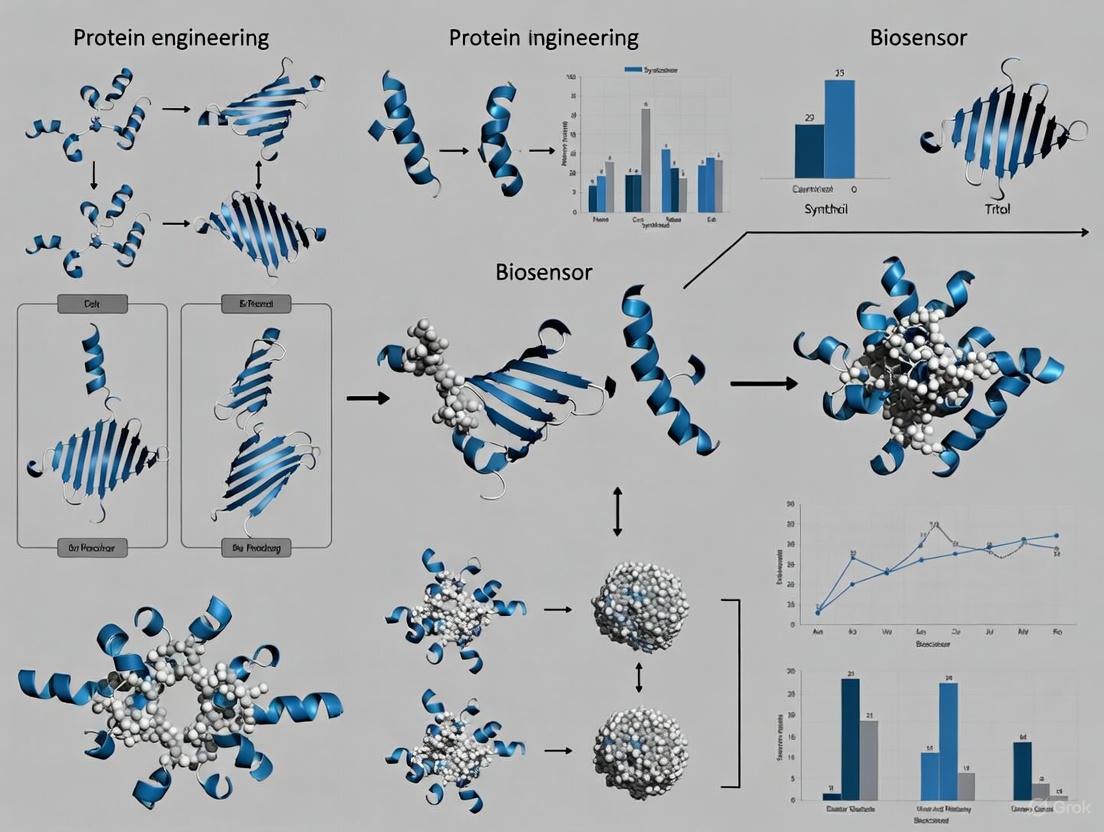

The following diagram illustrates the core concept and workflow of this strategy.

Workflow for Extending Dynamic Range

FAQ 5: How can I visualize the difference between a standard biosensor response and an engineered, extended-range response?

The fundamental difference lies in the shape of the dose-response curve. A natural, single-site binding event produces a hyperbolic curve, whereas an engineered biosensor can produce a log-linear curve over a much wider concentration range.

Comparison of Biosensor Responses

A core principle of biomolecular recognition is the inherent 81-fold dynamic range of single-site binding. This physical law states that transitioning a biosensor's binding site from 10% to 90% occupancy requires an 81-fold increase in target concentration [3]. While this affords high-affinity, high-specificity recognition, it creates significant limitations for real-world applications. Clinically relevant concentrations of targets, such as HIV viral loads, can span over five orders of magnitude (from ~50 to over 10ⶠcopies/mL), far exceeding the 81-fold window [3]. Similarly, monitoring drugs with narrow therapeutic indices requires a precision that is difficult to achieve with a standard hyperbolic binding curve. This article explores the nature of this thermodynamic hurdle and provides a technical toolkit for researchers to overcome it through rational protein engineering.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the origin of the 81-fold dynamic range in single-site binding? The 81-fold range is a direct consequence of the physics of hyperbolic binding described by the Langmuir isotherm. The transition from 10% to 90% site occupancy is a fixed, logarithmic function of concentration, mathematically requiring an 81-fold (9x9) change. This is not a limitation of specific proteins or detection methods, but a fundamental property of single-site binding equilibrium [3].

Q2: My biosensor needs to detect a clinical analyte across 4 orders of magnitude. Is single-site binding sufficient? No. The useful log-linear range of a single receptor variant is inherently limited to approximately 81-fold. For applications requiring quantification over a wider range, such as the 10,000-fold range in your case, you must employ strategies to extend the dynamic range. This is typically achieved by combining multiple receptor variants with different affinities but identical specificity in a single assay [3].

Q3: How can I make my biosensor more sensitive to very small changes in concentration within a critical range? You can narrow the dynamic range to create a steeper, more "switch-like" response. This is often accomplished using a sequestration mechanism, where a high-affinity, non-signaling receptor (a "sink") depletes the target until its concentration surpasses the sink's capacity. This creates a threshold response, allowing a second, signaling receptor to respond dramatically over a very narrow concentration window [3].

Q4: Can I engineer a receptor's affinity without affecting its specificity? Yes. Traditional mutagenesis of the binding site often alters specificity. A more robust strategy is to engineer a structure-switching mechanism. By stabilizing an alternative "non-binding" conformation (e.g., by tuning the stem stability of a molecular beacon), you can alter the apparent affinity without changing the atomic interactions that define specificity [3]. This approach mimics strategies used by naturally occurring intrinsically unfolded proteins.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inadequate Dynamic Range for Target Quantification

Symptoms:

- Sensor signal saturates at high target concentrations, preventing accurate quantification.

- Poor sensitivity at low target concentrations.

- Inability to fit a standard curve across the full required concentration range.

Solutions:

- Implement an Affinity-Variant Mixture:

- Generate a panel of receptor variants with affinities spanning several orders of magnitude. This is best done via structure-switching to preserve specificity [3].

- Optimal Mixing: Combine variants whose affinities differ by about 100-fold for the widest, most log-linear response. Avoid equimolar mixing; instead, use simulation-guided optimization of molar ratios to correct for differences in individual signal gain [3].

- Validation: Ensure the mixed-sensor maintains a consistent specificity profile across the entire extended range.

- Alternative Strategy - Directed Evolution:

- For transcription factor-based biosensors, a Functional Diversity-Oriented Volume-Conservative Substitution Strategy can be applied to key binding site residues.

- As demonstrated with the CaiF biosensor, this can yield variants with a dynamic range extended by 1000-fold and a 3.3-fold higher output signal [4].

Problem: Poor Specificity in Engineered Affinity Variants

Symptoms:

- Broadened dynamic range is achieved, but the sensor loses its ability to discriminate against off-target analogs.

- Specificity profile changes across the concentration range.

Diagnosis: This occurs when affinity is altered by directly mutating the binding site residues, which compromises the precise chemical complementarity required for specificity [3].

Fix:

- Adopt a Structure-Switching Approach: Engineer the stability of a non-binding conformation rather than the binding site itself.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Design a series of receptors (e.g., DNA molecular beacons) where the stability of the "off" state (e.g., the stem duplex) is systematically varied.

- Measure the affinity of each variant for the perfect target and a single-nucleotide mismatch target.

- Select variants that show a wide range of affinities for the correct target but maintain a consistently high discrimination factor against the mismatch [3].

Problem: Suboptimal Log-Linearity in Mixed-Sensor Output

Symptoms:

- Combined sensor output deviates from a straight line on a log(concentration) plot.

- "Gaps" or "plateaus" in the response curve at intermediate concentrations.

Diagnosis: This is often caused by combining receptors with an affinity difference that is too large (>500-fold) or by using non-optimized molar ratios, especially when variants have different maximum signal gains [3].

Fix:

- Simulate and Optimize: Use thermodynamic modeling to simulate the combined dose-response curve before experimental assembly.

- Adjust Molar Ratios: Do not use a simple 1:1 mixture. For example, a 100-fold affinity difference can be optimized for near-perfect log-linearity (R²=0.995) by mixing variants in a non-equimolar ratio (e.g., 59/41) [3].

- Consider a Three-State Sensor: If a large affinity difference is unavoidable, this can be repurposed into a three-state sensor that is highly sensitive to concentrations above and below an intermediate, insensitive window [3].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Core Protocol: Extending Dynamic Range with a Two-Component Mixture

This protocol outlines the creation of a biosensor with an ~8,100-fold dynamic range [3].

1. Generate Affinity Variants:

- System: DNA molecular beacons.

- Method: Design a set of beacons with identical target-binding loops but different stem stabilities (e.g., by changing the GC content or length). This tunes the switching equilibrium constant (K_S), altering apparent affinity without affecting specificity [3].

- Output: A set of beacons with dissociation constants (K_d) spanning at least two orders of magnitude (e.g., 0.012 μM to 128 μM).

2. Characterize Variants Individually:

- For each beacon, measure the fluorescence intensity across a range of target concentrations.

- Fit the data to a binding isotherm to determine the K_d and the maximum signal gain (relative fluorescence change).

- Confirm that all variants maintain similar specificity (e.g., by testing against a single-base mismatch target).

3. Optimize Mixing Ratio:

- Select two variants with a K_d ratio of approximately 100:1.

- Using the known signal gains of each variant, calculate the molar ratio required to produce a combined signal with maximum log-linearity. This is often not a 1:1 ratio [3].

- Example: A beacon with 83% of the max signal change and another with 100% were optimally mixed at a 59/41 ratio [3].

4. Validate the Mixed Sensor:

- Combine the two beacons at the optimized ratio.

- Measure the fluorescence response across a wide concentration range (e.g., 6-8 orders of magnitude).

- Plot the normalized signal vs. log[target] and confirm a wide, log-linear region (R² > 0.99).

Key Quantitative Data

Table 1: Performance of Structure-Switching Biosensor Architectures [3]

| Sensor Architecture | Components | Affinity Span | Dynamic Range | Signal Gain | Log-Linearity (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Beacon | 1 Receptor | N/A | 81-fold | Variable | N/A |

| Extended Range (2-component) | 2 Receptors | 100-fold | 8,100-fold | 9-fold | 0.995 |

| Extended Range (4-component) | 4 Receptors | >10,000-fold | ~900,000-fold | 3.6-fold | 0.995 |

| Three-State Sensor | 2 Receptors | 12,000-fold | Sensitive at high/low ends | Variable | Not Applicable |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Dynamic Range Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Structure-Switching Receptors | Receptors that undergo a conformational change upon binding; affinity is tuned via stability of the "off" state. | Molecular beacons with engineered stem stability [3]. |

| Affinity-Variant Panel | A set of receptors with different affinities but identical binding site specificity. | A panel of six molecular beacons with K_d from 0.012 μM to 128 μM [3]. |

| Non-Signaling Depletant | A high-affinity receptor used in sequestration to create a threshold response. | A non-fluorescent molecular beacon variant used to narrow dynamic range [3]. |

| Competitive Binder | A known, high-affinity ligand used in competition assays to characterize ultra-tight binding. | Nanobodies used in competition ITC to measure pM affinities of IDP-target binding [7]. |

Visualizing the Concepts and Workflows

Engineering Biosensor Dynamic Range

Workflow for a Mixed-Affinity Sensor

Troubleshooting FAQs: Extending Biosensor Dynamic Range

FAQ 1: My engineered biosensor has a low signal-to-noise ratio. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A low signal-to-noise ratio often stems from non-specific interactions or suboptimal sensor-receptor binding kinetics. To address this, first, verify the biosensor's operating range and response threshold using a dose-response curve to ensure it is suited for your target analyte concentration [1]. Second, employ directed evolution strategies to enhance the biosensor's specificity. This involves creating mutant libraries and using high-throughput screening, such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), to select variants with improved binding and reduced background noise [1] [8]. Finally, ensure that the transducer element (e.g., electrode for electrochemical sensors) is properly modified with high-quality nanomaterials to enhance signal capture and minimize interference [9].

FAQ 2: How can I make my protein-based biosensor respond faster to dynamic analyte changes?

Slow response times are frequently due to limitations in the signaling mechanism's kinetics. For faster response, consider incorporating faster-acting components like riboswitches or toehold switches into a hybrid design [1]. For protein-based sensors, explore engineering strategies that utilize mechanisms like protein stability and induced degradation, as these can facilitate more rapid turnover and measurement of the cellular state compared to some traditional transcription factors [8]. Furthermore, tuning the biosensor's dynamic performance by optimizing the plasmid copy number or the position of operator regions can significantly improve its rise time [1].

FAQ 3: My biosensor's dynamic range is too narrow for my application. How can I broaden it?

A narrow dynamic range limits the biosensor's utility across varying analyte concentrations. A primary method for broadening the dynamic range is to engineer the linkage between the recognition element and the output module. This can be achieved by modulating promoter strength, ribosome binding sites (RBS), or the number and position of operator regions [1]. Another powerful approach is to use directed evolution to selectively pressure the biosensor to respond to a wider concentration window of the target analyte, thereby shifting its response threshold and maximum output [8]. For electrochemical biosensors, utilizing nanocomposites like porous gold with polyaniline can enhance sensitivity across a broader concentration range [10].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for integrating a novel biosensor into a genetic circuit for metabolic control?

Integrating a new biosensor into a genetic circuit requires careful characterization to ensure robust performance. Start by thoroughly characterizing the biosensor's dose-response curve, dynamic range, and response time in isolation to establish a baseline [1]. To ensure seamless integration, adopt a decoupled design where possible, similar to the ARTIST platform, which separates the recognition element from the molecular circuit. This modularity allows for independent optimization of the sensor and the actuator modules [11]. Finally, implement real-time validation using multi-omics profiling to assess how the integrated circuit impacts host metabolism and to verify that the dynamic control functions as intended without causing toxicity or pathway imbalances [12].

Performance Metrics for Biosensor Engineering

The table below summarizes key quantitative parameters to monitor when engineering biosensors for an extended dynamic range. These metrics are essential for evaluating performance during troubleshooting [1].

| Performance Parameter | Description | Impact on Dynamic Range | Ideal Characteristics for Extended Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | The ratio between the maximal and minimal detectable signal output. | Defines the operational window of the biosensor. | A high ratio, indicating sensitivity over a wide concentration span. |

| Operating Range | The concentration window of analyte where the biosensor performs optimally. | Determines the upper and lower bounds of usable detection. | A wide linear range within the dose-response curve. |

| Response Time | The speed at which the biosensor reacts to a change in analyte concentration. | Affects the ability to track rapid dynamic changes. | Fast rise-time to quickly reach a new steady-state output. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | The clarity and reliability of the output signal against background variability. | A low ratio can obscure the true signal, effectively narrowing the detectable range. | A high ratio for clear distinction between baseline and activated states. |

| Response Sensitivity | The slope of the dose-response curve, indicating how much output changes per unit change in input. | A steeper slope can lead to a narrower range; requires balancing. | A sufficient slope for detectability without sacrificing range width. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Directed Evolution of a Protein-Based Biosensor for Altered Dynamic Range

This protocol outlines the process of using directed evolution to create biosensor variants with improved dynamic range [8].

- Library Construction: Generate a diverse mutant library of your biosensor gene. Methods include error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, or saturation mutagenesis of key residues in the ligand-binding or allosteric domains.

- Transformation and Screening: Clone the mutant library into an appropriate microbial host (e.g., E. coli or yeast) and transform. Use high-throughput screening based on fluorescence (e.g., FACS) or growth selection to isolate clones that show an output signal (e.g., fluorescence) across a wider range of target analyte concentrations.

- Characterization of Hits: Isolate plasmid DNA from selected clones and sequence to identify mutations. Re-transform individual purified plasmids into a fresh host to confirm the phenotype.

- Dose-Response Analysis: Grow cultures of the confirmed hits and expose them to a gradient of analyte concentrations. Measure the output signal (e.g., fluorescence via plate reader) to generate a new dose-response curve. Calculate the new dynamic range and compare it to the parent biosensor.

- Iteration: Use the best-performing variant as a template for subsequent rounds of evolution to further refine the dynamic range and other properties.

Protocol 2: Tuning Dynamic Range via Promoter and RBS Engineering

This protocol describes a rational design approach to modulate biosensor output by engineering regulatory parts [1].

- Modular Part Assembly: Use standard cloning techniques (e.g., Golden Gate assembly) to create genetic constructs where the biosensor's output gene (e.g., a fluorescent reporter) is controlled by a series of different promoters and ribosome binding sites (RBS) of varying strengths.

- Characterization of Constructs: Transform each construct into your host organism. For each construct, measure the dose-response relationship as described in Protocol 1, step 4.

- Data Analysis: Plot the dose-response curves for all constructs. Analyze how the different promoter-RBS combinations affect the maximum output level (directly influencing the dynamic range) and the response threshold.

- Selection and Integration: Select the construct that provides the most desirable dynamic range and operational range for your specific application. This tuned construct can then be integrated into larger genetic circuits.

Biosensor Engineering and Optimization Pathways

Diagram: Evolutionary Engineering of Biosensors

Diagram: Dose-Response Optimization Concepts

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The table below lists essential reagents and tools for implementing the evolutionary strategies discussed in this guide.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Dose-Response Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Directed Evolution Kits | Commercial kits for error-prone PCR or DNA shuffling to create diverse mutant libraries. | Generates genetic diversity for screening biosensors with altered ligand binding and output properties [8]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | High-throughput instrument that sorts cells based on fluorescent signals. | Essential for screening large mutant libraries to isolate clones with desired dynamic range and output intensity [1]. |

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors | Engineered TFs with modified specificity and sensitivity to a target analyte. | Can be used as the sensing module to re-engineer the input side of the biosensor's dose-response [1]. |

| Riboswitch / Toehold Switch Parts | Synthetic RNA elements that change conformation upon ligand binding or RNA hybridization. | Provide a modular, fast-acting component for hybrid biosensor designs to improve response time and programmability [1]. |

| Protein Degradation Tags | Peptide sequences (e.g., degrons) that target a protein for rapid proteolysis. | Engineering biosensors using stability/degradation mechanisms allows for faster turnover and rapid response to cellular state changes [8]. |

| Nanomaterial Composites | Materials like porous gold, polyaniline, or carbon nanotubes for electrode modification. | Used in electrochemical biosensors to enhance signal transduction, sensitivity, and stability, thereby supporting a wider dynamic range [9] [10]. |

| Trypanothione synthetase-IN-5 | Trypanothione synthetase-IN-5, MF:C35H39F2IN4O3, MW:728.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tubulin polymerization-IN-43 | Tubulin polymerization-IN-43, MF:C17H13F4N3O, MW:351.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

Transcription Factor (TF)-Based Biosensor Issues

Problem: My TF-based biosensor has a restricted dynamic range and low signal output.

- Potential Cause 1: The allosteric transcription factor (aTF) may have suboptimal binding affinity for its ligand or DNA. Protein engineering can modify key residues to alter ligand specificity and binding efficiency [13].

- Solution: Employ directed evolution or computational design to engineer the aTF. A Functional Diversity-Oriented Volume-Conservative Substitution Strategy can be used to create variants. For example, engineering the CaiF transcription factor with Y47W/R89A mutations extended its concentration response range by 1000-fold and increased output signal intensity by 3.3-fold [4].

- Potential Cause 2: Leaky expression or non-specific activity in the genetic circuit [13].

- Solution: Review the biosensor's design architecture (e.g., repression of activator aTF). Minimize cross-talk by selecting orthogonal parts and using background cell strains with reduced native regulatory interference [13].

Problem: The biosensor shows poor performance upon heterologous expression.

- Potential Cause: The host cell environment may not be compatible, leading to improper protein folding or function [13].

- Solution: Optimize codons for your host organism. Test biosensor function in different bacterial or yeast chassis to identify the most suitable expression system [13].

Allosteric Protein Switch Performance

Problem: I cannot identify potential allosteric sites for engineering control.

- Potential Cause: Allosteric sites are not always obvious from a protein's primary structure [14].

- Solution: Utilize computational tools to predict allosteric sites and pathways. Tools like Ohm can identify allosteric sites coupled to an active site and analyze communication pathways. AlloSigMA can explore the energetics of allosteric pathways, and SPACER can quantify allosteric communication [14].

Problem: Engineered allosteric control does not effectively modulate protein activity.

- Potential Cause: The inserted sensor domain may not be effectively coupled to the target protein's functional motions [15].

- Solution: Experiment with different domain insertion sites using flexible linkers. High-throughput screening is often necessary to identify functional switches where the inserted domain allosterically regulates the target protein's activity in response to specific triggers [15].

Aptasensor Functionality

Problem: My DNA or RNA aptamer is unstable in biological fluids.

- Potential Cause: Nucleic acid aptamers are prone to degradation by nucleases [16].

- Solution: Use chemically modified nucleotides (e.g., 2'-fluoro, 2'-amino) during the SELEX process to enhance nuclease resistance. Alternatively, consider using peptide aptamers [16].

Problem: The capacitive aptasensor shows inconsistent signal changes upon target binding.

- Potential Cause: The mechanism of how aptamer-target binding modifies capacitance is complex and can be influenced by factors like conformational change, charge distribution, and ion displacement within the electrical double layer (EDL) [17].

- Solution: Systematically investigate the individual aptamer-target interaction. Ensure consistent surface functionalization and use controlled experimental conditions to better understand and optimize the physical mechanism leading to the capacitance change [17].

General Biosensor & Assay Problems

Problem: The protein assay is providing inaccurate concentration readings.

- Potential Cause: The sample buffer contains incompatible substances that interfere with the assay chemistry. Common interferents include reducing agents, chelators, detergents, and strong acids/bases [18].

- Solution: Dilute the sample several-fold in a compatible buffer, dialyze or desalt the sample, or precipitate the protein to remove interferents. Always consult the assay's compatibility chart [18].

Problem: High background or "Standards Incorrect" error in fluorescent protein assays.

- Potential Cause: The assay kit may have expired, been stored incorrectly, or the sample buffer contains detergents or other interfering components [18].

- Solution: Prepare fresh calibration standards. Check that the composition of your sample buffer is within the acceptable limits for the assay. For Qubit assays, ensure you are using the recommended tubes and pipetting volumes of at least 5 µL for accuracy [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of using aptamers over antibodies in biosensors?

A1: Aptamers offer several key advantages: they are produced entirely in vitro via the SELEX process, eliminating the need for animals and reducing batch-to-batch variation [16]. They can be selected against a wider range of targets, including non-immunogenic toxins and small molecules [16]. Their denaturation is often reversible, leading to a longer shelf life, and they are easily chemically modified for improved stability or labeling [16].

Q2: How can I find a transcription factor for a metabolite that currently has no known biosensor?

A2: You can explore the current knowledge base by mining specialized databases such as RegulonDB (for E. coli), RegPrecise (for prokaryotes), or P2TF (for predicted prokaryotic TFs) [13]. If no known TF exists, homology-based prediction can be used to find TFs in other species that belong to well-known regulator families (e.g., LysR, TetR, AraC) and are likely to respond to your metabolite of interest [13].

Q3: What computational strategies can I use at the start of a project to design a new allosteric protein?

A3: Computational tools are essential for identifying allosteric sites and pathways. You can use:

- Ohm: To identify allosteric sites and communication pathways from a 3D protein structure [14].

- Network-based methods: Treat the protein as a network of interacting residues to identify communication paths between distal sites [14].

- Elastic network models: To study efficient communication pathways and species-specific allosteric sites [14].

Q4: My HCP (Host Cell Protein) ELISA is giving inconsistent results between lots. How can I improve quality control?

A4: For generic impurity assays, the most reliable quality control is to use laboratory-specific control samples. Prepare a bulk lot of controls using your specific analyte (e.g., HCPs from your process) in the same matrix as your critical samples. Aliquot and freeze these controls at -80°C. Establish a statistically valid range for them and use these controls, rather than just curve-fit parameters, to assure run-to-run and lot-to-lot quality [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagents and Databases for Biosensor Development

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| SELEX | A process (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment) to generate high-affinity DNA or RNA aptamers for specific targets [16]. |

| RegulonDB | A primary database for transcriptional regulation in E. coli K-12, useful for finding native transcription factors and their regulons [13]. |

| JASPAR | An open-access database of curated transcription factor binding profiles, useful for designing synthetic promoter elements for biosensors [13]. |

| Allosteric Site Prediction Tools (e.g., Ohm, AlloSigMA) | Computational platforms to identify allosteric sites and communication pathways within a protein structure, guiding engineering efforts [14]. |

| Directed Evolution Tools | A suite of methods, including site-saturation mutagenesis and high-throughput screening, used to engineer properties like the dynamic range of transcription factors [13] [4]. |

| Chemically Modified Nucleotides | Nucleotides (e.g., 2'-fluoro) used during SELEX to create aptamers with enhanced nuclease resistance for use in complex biological fluids [16]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Directed Evolution to Extend Biosensor Dynamic Range

This protocol outlines a strategy for modifying a transcription factor-based biosensor, such as the l-carnitine biosensor CaiF, to broaden its dynamic range [4].

- Computer-Aided Design: Formulate the 3D structural configuration of the TF (e.g., CaiF) using modeling software. Simulate the DNA and ligand binding sites.

- Alanine Scanning: Perform alanine scanning mutagenesis of residues in the predicted functional sites to validate their importance.

- Diversity-Oriented Substitution: Conduct a "Functional Diversity-Oriented Volume-Conservative Substitution Strategy" on the key functional residues identified in steps 1 and 2. This involves creating a library of TF variants with mutations at these sites.

- Library Screening: Clone the variant library into a biosensor circuit with a reporter gene (e.g., GFP). Screen the library under varying concentrations of the target ligand (e.g., l-carnitine).

- Variant Characterization: Isolate variants that show a response over a wider concentration range and/or with higher signal output. Characterize the lead variant (e.g., CaiF_Y47W/R89A) by measuring its response curve from low (e.g., 10â»â´ mM) to high (e.g., 10 mM) ligand concentrations [4].

Protocol 2: SELEX for Aptamer Development

This protocol describes the general process for selecting specific DNA or RNA aptamers [16].

- Library Synthesis: Synthesize a large, diverse library of single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules (up to ~10¹ⴠdifferent sequences) with random central regions.

- Incubation with Target: Incubate the library with the immobilized target molecule (e.g., a protein).

- Partitioning: Remove unbound nucleic acid sequences through washing steps.

- Elution: Elute the target-bound sequences from the immobilization surface.

- Amplification: Amplify the eluted sequences using PCR (for DNA) or RT-PCR (for RNA).

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 for multiple rounds (typically 6-15) to enrich for high-affinity binders.

- Cloning and Sequencing: After the final round, clone and sequence the enriched pool to identify individual aptamer candidates.

- Binding Characterization: Synthesize the candidate aptamers and characterize their binding affinity and specificity under relevant conditions (e.g., temperature, pH).

Supporting Diagrams

Biosensor Engineering Workflow

Allosteric Transcription Factor Mechanism

Technical Support Center: Extending Biosensor Dynamic Range

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) for researchers working on extending the dynamic range of biosensors through protein engineering. The content is designed to help you address specific experimental challenges and implement advanced methodologies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is the inherent dynamic range of a single-site binding biosensor limited, and what is the theoretical basis for this limitation? The fundamental limitation arises from the physics of single-site binding, which produces a hyperbolic dose-response curve (the Langmuir isotherm). For any single-site binding event, the transition from 10% to 90% receptor occupancy requires an 81-fold change in target concentration [3] [20]. This fixed dynamic range is often insufficient for applications where target concentrations vary over several orders of magnitude, such as monitoring viral loads in patients, or where high sensitivity to small concentration changes is critical, such as tracking drugs with narrow therapeutic indices [3].

FAQ 2: What are the primary protein engineering strategies for extending the dynamic range of my biosensor? The main strategies, inspired by mechanisms found in nature, involve combining multiple engineered receptor elements [3].

- Strategy 1: Affinity-Tuned Receptor Mixtures. This involves creating a set of receptor variants (e.g., mutated proteins or DNA stem-loops) that bind the same target with identical specificity but different affinities. When these variants are combined, their individual hyperbolic responses merge to create a single, extended log-linear dynamic range [3] [20]. For instance, combining two receptors with a 100-fold difference in affinity can extend the dynamic range to 8,100-fold [3].

- Strategy 2: The Sequestration/Depletant Mechanism. This strategy narrows the dynamic range to create an ultrasensitive, threshold response. A high-affinity, non-signaling receptor (the "depletant") is used to sequester the target. The signaling receptor, which has a lower affinity, only begins to produce a signal after the depletant is saturated, compressing the response into a very narrow concentration window (e.g., an 8-fold range) [20].

FAQ 3: How can I engineer a protein receptor to alter its affinity without changing its target specificity? A key technique is to engineer a structure-switching mechanism into the receptor. By stabilizing an alternative, non-binding conformation, you can tune the apparent affinity without altering the specific atomic interactions of the binding site itself [3]. This is often achieved by:

- Introducing destabilizing mutations remote from the binding site to couple target binding to a conformational change (folding) [20].

- Employing "alternate frame folding," a strategy involving the duplication of a protein segment to stabilize a non-binding conformation [20]. For example, in DNA-based biosensors, the stem stability can be modified to change affinity while keeping the target-recognizing loop sequence identical [20].

FAQ 4: I have successfully created receptor variants with different affinities. What is the optimal way to combine them for a maximized log-linear range? The optimal combination is not always an equal molar ratio. Simulations and empirical data suggest [3]:

- For a two-variant mixture, a ~100-fold difference in affinity between them produces the widest, most log-linear range.

- If the signal gain of individual variants degrades (e.g., due to an unstable switch), you must adjust the molar ratios to correct for this. For instance, a 59/41 ratio of two variants with a 100-fold affinity difference achieved a dynamic range of 8,100-fold with excellent log-linearity (R²=0.995) [3].

- Using more than two variants (e.g., four) can extend the dynamic range even further, to nearly 900,000-fold, but requires careful optimization of mixing ratios using simulations [3].

FAQ 5: My biosensor's signal output is low. What are some advanced signal transduction methods to improve it? Innovative transducer designs can dramatically enhance signal output. One powerful method is the use of engineered chemogenetic FRET pairs. For example, creating a stable interface between a fluorescent protein (FRET donor) and a fluorescently labeled HaloTag (FRET acceptor) can achieve near-quantitative FRET efficiencies (≥95%) [21]. This design can be adapted to create biosensors for analytes like calcium, ATP, and NAD⺠with unprecedented dynamic ranges. The system is highly tunable, allowing you to change the fluorescent protein or the synthetic fluorophore to shift the biosensor's spectral properties [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The combined biosensor response is not log-linear and shows plateaus or dips.

- Potential Cause 1: The affinity difference between your receptor variants is too large (significantly greater than 100-fold). A large gap can cause deviations from linearity at intermediate target concentrations [3].

- Solution: Characterize the dissociation constants (Kd) of your variants more precisely. Select a set of variants whose affinities differ by approximately 30- to 100-fold for pairing and fine-tune the ratios [3] [20].

- Potential Cause 2: The receptor variants are not combined in the optimal ratio.

- Solution: Do not assume a 1:1 ratio is ideal. Use simulation software to model the expected combined response based on the measured Kd and signal gain of each variant. Empirically test a range of mixing ratios to identify the one that produces the smoothest log-linear response [3].

Problem: The biosensor with a sequestration mechanism has a poor signal-to-noise ratio.

- Potential Cause 1: The density of the signaling probe on the sensor surface is too low, often due to an excessively high [depletant]/[probe] ratio [20].

- Solution: Titrate the ratio of depletant to signaling probe during sensor fabrication. The pseudo-Hill coefficient will increase with the ratio, but it eventually plateaus. Avoid ratios that reduce the signaling probe density to a point where the Faradaic current is no longer measurable [20].

- Potential Cause 2: The sample volume is not controlled.

- Solution: The sequestration mechanism is highly dependent on a fixed, small sample volume to prevent premature saturation of the depletant. Standardize your assay volume precisely [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Extending Dynamic Range via Affinity-Tuned Receptor Combination This protocol outlines the steps for creating a biosensor with an extended dynamic range by mixing affinity-tuned receptor variants [3] [20].

Materials:

- Purified receptor variants (e.g., structure-switching proteins or nucleic acids) with characterized Kd values.

- Immobilization substrate (e.g., gold electrode, microplate).

- Target analyte of interest.

- Buffer solutions for binding assays.

- Signal detection apparatus (e.g., potentiostat for electrochemical detection, fluorimeter).

Procedure:

- Engineer and Characterize Variants: Generate receptor variants using site-directed mutagenesis or other protein engineering techniques to stabilize non-binding conformations. Determine the precise Kd of each variant.

- Select Variant Pair: Choose two or more variants that share the same specificity but have Kd values differing by approximately 100-fold for optimal range extension [3].

- Optimize Mixing Ratio: Based on the Kd and signal gain of each variant, calculate the optimal mixing ratio. For example, a 59/41 ratio was used for a specific 100-fold affinity difference pair [3].

- Co-Immobilize Receptors: Mix the receptor variants in the optimized ratio and immobilize them onto your chosen substrate (e.g., electrode surface).

- Validate Performance: Expose the biosensor to a dilution series of the target analyte spanning several orders of magnitude. Measure the output signal and plot it against the logarithm of the target concentration. A successful sensor will show a linear relationship across a much wider range than any single variant.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Sequestration Mechanism for a Narrowed, Ultrasensitive Response This protocol details the use of a non-signaling depletant to create a biosensor with a threshold response [20].

Materials:

- Signaling receptor (low-affinity variant).

- Non-signaling depletant receptor (high-affinity variant, identical target specificity).

- Immobilization substrate.

- Fixed-volume sample delivery system.

Procedure:

- Prepare Receptors: Produce a signaling receptor (e.g., a structure-switching probe with a redox reporter or fluorophore) and a high-affinity, non-signaling depletant (e.g., a linear version of the same probe without a reporter) [20].

- Co-Immobilize at Set Ratio: Immobilize both the signaling probe and the depletant onto the sensor surface. A typical starting [depletant]/[probe] ratio is 50:1, but this should be optimized [20].

- Test with Fixed Volume: Challenge the sensor with a target concentration series using a precise, fixed sample volume (e.g., 3 µL).

- Analyze Dose-Response: Fit the resulting dose-response curve to the Hill equation. A successful implementation will yield a steep curve with a high pseudo-Hill coefficient (e.g., 2.3) and a useful dynamic range compressed to as little as 8-fold [20].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Biosensor Performance

Table 1: Performance of Biosensors with Engineered Dynamic Ranges

| Sensor Type | Engineering Strategy | Original Dynamic Range | Engineered Dynamic Range | Key Metric / Signal Gain | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Beacon [3] | Affinity-Tuned Mixture (4 variants) | 81-fold | ~900,000-fold | 3.6-fold signal gain | Nucleic acid detection |

| E-DNA Sensor [20] | Affinity-Tuned Mixture (2 variants) | 81-fold | ~1,000-fold | Excellent log-linearity (R²=0.978) | Electrochemical DNA detection |

| E-DNA Sensor [20] | Sequestration Mechanism | 81-fold | 8-fold | Pseudo-Hill coefficient of 2.3 | Ultrasensitive detection |

| CaiF-based Sensor [4] | Directed Evolution (CaiFY47W/R89A) | Not Specified | 10â»â´ mM – 10 mM (1000x wider) | 3.3-fold higher signal intensity | L-carnitine production monitoring |

| Chemogenetic FRET [21] | Engineered FP-HaloTag Interface | Low FRET efficiency | ≥94% FRET efficiency | FRET ratio >14 in cells | Live-cell metabolite imaging (Ca²âº, ATP, NADâº) |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Dynamic Range Engineering

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Structure-Switching Receptors [3] [20] | The core sensing element; affinity is tuned by altering the stability of the non-binding state. | Allows modulation of apparent affinity (Kd) without altering target-binding specificity. |

| HaloTag Protein & Rhodamine Ligands [21] | Components of a chemogenetic FRET pair for high-gain signal transduction. | Enables spectral tunability and near-quantitative FRET efficiency for large dynamic ranges. |

| Electrochemical Electrodes [22] [20] | Platform for immobilizing receptors and transducing binding events into a measurable current. | Often modified with nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, Au-Ag nanostars) to enhance signal transmission [22]. |

| Directed Evolution Platform [4] [23] | A method for generating diverse receptor variants with improved properties. | Used to create transcription factor variants (like CaiF) with extended operational ranges. |

| Non-Signaling Depletant [20] | A high-affinity receptor used in the sequestration mechanism to create a threshold response. | Silently sequesters the target analyte until a concentration threshold is surpassed. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

Engineering Solutions: From Structure-Switching Receptors to Directed Evolution

Troubleshooting Guide: Extending Dynamic Range

| Problem Observed | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution & Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limited Dynamic Range | Switching equilibrium constant (KS) is too large, favoring the bound conformation even at low analyte concentrations [24]. | Measure signal output across a wide analyte concentration range to identify saturation point. | Use directed evolution or rational design to introduce mutations that destabilize the bound state (decrease KS), shifting the equilibrium to favor the unbound state at low [analyte] [24] [4]. |

| Low Signal Intensity | Conformational change does not efficiently transduce into a measurable output signal [24]. | Test sensor with a saturating analyte concentration to determine maximum achievable signal. | Optimize fluorophore/quencher placement (for optical sensors) or redox reporter positioning (for electrochemical sensors) to maximize signal change between states [24]. |

| Loss of Specificity | Mutations intended to tune affinity have disrupted key binding pocket residues [25]. | Perform binding assays against structurally similar off-target molecules. | Focus affinity-tuning mutations outside the primary interaction interface, as these can alter global affinity with less impact on specificity [25]. |

| Insufficient Sensitivity | Sensor has a high KD (low innate affinity) for the target analyte [24]. | Determine the limit of detection (LOD) and the lower limit of the concentration-response curve. | Rationally engineer the binding interface to improve complementary interactions, lowering KD and improving sensitivity for low-concentration targets [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental thermodynamic principle that allows me to tune a biosensor's apparent affinity?

The operation of structure-switching biosensors is governed by a conformational selection mechanism [24]. The biomolecular switch exists in an equilibrium between a non-binding "off" state and a binding-competent "on" state, defined by the switching equilibrium constant (KS = [on]/[off]). The apparent affinity (KD,app) is a function of both this intrinsic KS and the innate binding affinity (KD) for the target to the "on" state. By mutating residues that affect the stability of the "on" vs. "off" state, you can alter KS and thereby tune the KD,app without necessarily changing the fundamental chemical interactions in the binding pocket itself [24].

Q2: How can I experimentally determine if a mutation has altered the switching equilibrium (KS) versus the innate binding affinity (KD)?

Distinguishing between these effects requires careful experimental design. A change in innate KD primarily affects the saturation point of your concentration-response curve. In contrast, a change in KS shifts the entire curve left or right along the concentration axis, effectively changing the analyte concentration at which half-maximal signal is achieved (EC50D, separate from the coupled switching event.

Q3: Are there specific regions on a protein scaffold where mutations are more likely to tune affinity without compromising specificity?

Yes. Mutations at residues outside the direct binding interface are often effective for tuning global affinity with minimal impact on specificity [25]. For instance, in coiled-coil interactions, residues at solvent-exposed positions can influence dimer stability and propensity without directly participating in partner selection [25]. Similarly, mutations that affect the backbone flexibility or allosteric networks linking the binding site to the output domain can modulate KS and thus apparent affinity, while preserving the precise binding interface.

Q4: A directed evolution campaign successfully extended my sensor's dynamic range, but it now responds to an off-target. What is the likely cause, and how can I fix it?

This indicates that the selected mutations have likely altered residues within the binding pocket that are critical for specificity. Specificity is often determined by a combination of features that promote on-target binding and those that actively prevent off-target binding [25]. To fix this, you can employ a counter-selection strategy during screening. In addition to selecting for the desired dynamic range under positive pressure (e.g., with the target analyte), simultaneously apply negative pressure by exposing the library to the off-target molecule and selecting variants that do not respond. This enriches for mutations that confer the desired switching properties while maintaining or even enhancing specificity.

Experimental Protocol: Modulating Dynamic Range via Directed Evolution

This protocol outlines a methodology for extending the dynamic range of a transcription factor-based biosensor, based on a study that successfully modified the l-carnitine biosensor CaiF [4] [26].

Key Reagents and Equipment

| Item | Function/Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Plasmid Library | Contains the gene for your biosensor (e.g., CaiF) with randomized codons at targeted positions. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | High-throughput method to screen and isolate mutant cells based on their fluorescence output in response to different analyte concentrations. |

| Analyte Stock Solutions | Prepare a high-concentration stock (e.g., 10 mM) and a low/no-analyte solution for counter-selection. |

| Microplate Reader | For characterizing the concentration-response curves of isolated clones. |

| Computer-Aided Design Software | For structural analysis and identifying key residues to mutate (e.g., DNA binding domain, allosteric sites). |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Library Construction:

- Rational Targeting: Use structural models (e.g., from computer-aided design) to identify key functional regions, such as the DNA-binding domain or allosteric regulatory sites. Alanine scanning can be used for preliminary validation [4].

- Diversity Generation: Employ a "Functional Diversity-Oriented Volume-Conservative Substitution Strategy" at the identified key sites [4]. This involves substituting residues with amino acids of similar size but different biochemical properties to explore functional changes while minimizing structural disruption.

- Library Quality Control: Sequence a sample of the library to ensure diversity and the absence of wild-type sequence bias.

High-Throughput Screening for Dynamic Range:

- Growth and Induction: Grow the library of mutant cells in a medium that induces the expression of the biosensor construct.

- Dual-Concentration Sorting: Divide the cell population and expose one aliquot to a low (or zero) concentration of the analyte and a second aliquot to a saturatingly high concentration of the analyte.

- FACS Gating: Isolate two populations of cells: i) those showing the lowest fluorescence output in the low-analyte condition (minimal background leakage), and ii) those showing the highest fluorescence output in the high-analyte condition (strong maximum signal). Cells that pass both gates possess a wide dynamic range [4].

Characterization of Hits:

- Clone Isolation: Plate the sorted cells to obtain single colonies.

- Concentration-Response Profiling: Inoculate cultures of individual clones and measure their fluorescence output across a comprehensive range of analyte concentrations (e.g., from 10-4 mM to 10 mM) [4] [26].

- Data Analysis: Fit the response data to a sigmoidal curve (e.g., Hill equation) to determine the EC50 (apparent affinity), Hill slope, and maximum output for each variant.

Specificity Validation:

- Challenge the top-performing variants with structurally similar molecules to ensure that the expanded dynamic range has not come at the cost of specificity. Reject variants that show significant cross-reactivity.

Visualizing the Thermodynamic Principle of Tuning

The following diagram illustrates the core concept of tuning a biosensor's dynamic range by modulating the switching equilibrium.

Modulating the Switching Equilibrium - This diagram shows how mutations can shift the equilibrium between the "off" and "on" states of a biosensor. By making the "on" state less stable (decreasing KS), a higher analyte concentration is required to drive the system to the bound state, thereby shifting the dose-response curve and extending the dynamic range to higher concentrations [24] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function in Tuning Apparent Affinity |

|---|---|

| Bacterial Periplasmic Binding Proteins (bPBPs) | A common protein scaffold that undergoes large hinge-bending motions upon ligand binding, ideal for engineering structure-switching biosensors [24]. |

| Environmentally-Sensitive Fluorophores | Single fluorophores whose quantum yield changes based on the immediate polarity of their microenvironment, used to report conformational changes in single-fluorophore sensors [24]. |

| FRET Donor/Acceptor Pairs | Pairs of fluorophores (e.g., CFP/YFP) used to measure distance changes via Förster Resonance Energy Transfer, ideal for monitoring conformational changes in dual-fluorophore sensors [24]. |

| Electrochemical Reporters (e.g., Methylene Blue) | Redox-active molecules that can be attached to biomolecules; their electron transfer efficiency to an electrode changes with distance/orientation, enabling electrochemical detection of switching [24]. |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (e.g., bPCA) | A high-throughput method (like binding Protein Fragment Complementation Assay) to quantify the effects of thousands of mutations on binding affinity and specificity across many interaction partners [25]. |

Core Concept: Editing Biosensor Dynamic Range

Biomolecular recognition elements, such as antibodies and aptamers, are the cornerstone of artificial biosensors [27]. A fundamental limitation of these single-site binding receptors is their inherently fixed dynamic range: the transition from 10% to 90% receptor occupancy requires an 81-fold change in target concentration [3]. This range is often too narrow for clinical applications, where target concentrations, such as HIV viral loads, can vary by over five orders of magnitude [3].

Inspired by strategies found in nature, researchers can overcome this limitation by rationally combining multiple receptor variants that bind the same specific target but differ in their affinity [3]. This approach thermodynamically "edits" the biosensor's dose-response curve, creating a composite signal that is log-linear across a much wider concentration range.

Key Experimental Data and Workflows

Table 1: Properties of Individual Molecular Beacon Receptor Variants

This table summarizes data from a foundational study that engineered a series of molecular beacon receptors by varying the stability of their non-binding stem structure [3].

| Receptor Variant Name | Dissociation Constant (Kd) | Relative Affinity (Fold Change) | Maximum Fluorescence Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0GC | 0.012 µM | 1 (Highest) | Not Specified |

| 1GC | 0.12 µM | 10 | 83% |

| 2GC | 1.3 µM | ~108 | Not Specified |

| 3GC | 12 µM | 1,000 | 100% |

| 5GC | 128 µM | ~10,667 (Lowest) | Not Specified |

Table 2: Performance of Engineered Receptor Mixtures

By mixing the variants from Table 1 in optimized ratios, the following sensor performances were achieved [3].

| Receptor Mixture Composition | Optimized Mixing Ratio | Log-Linear Dynamic Range | Signal Gain | Linearity (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1GC + 3GC | 59 / 41 | 8,100-fold | 9-fold | 0.995 |

| 0GC + 2GC + 3GC + 5GC | Optimized | ~900,000-fold | 3.6-fold | 0.995 |

| 0GC + 5GC | Not Specified | "Three-State" Response | Not Specified | Not Applicable |

Diagram 1: Strategy for Extending Dynamic Range

Experimental Protocol: Creating an Extended-Range Biosensor

Step 1: Generate a Panel of Affinity-Tuned Receptors

The first step is to create receptor variants that differ in affinity while maintaining identical target specificity.

- Structure-Switching Mechanism: A highly effective method involves engineering a conformational switch into the receptor [3]. For DNA-based receptors like molecular beacons, this is achieved by systematically altering the stability of the stem-loop structure's stem (e.g., by changing its GC content or length) [3]. For protein-based receptors, this can involve stabilizing a non-binding conformation [3].

- Critical Validation: For each variant, confirm that the dissociation constant (Kd) shifts as intended while specificity against non-target molecules remains consistent across all variants [3].

Step 2: Determine Optimal Mixing Ratios

Combining receptors is not a simple 1:1 mixture. Optimal ratios must be calculated and experimentally verified.

- Simulation: Begin with thermodynamic simulations to model the combined dose-response of different variant pairs or groups. A 100-fold difference in affinity between variants often yields the widest log-linear range [3].

- Correction for Signal Gain: Receptors with less stable non-binding states may have lower signal gain. Simulations can be used to correct for this by adjusting molar ratios. For instance, a 59/41 ratio was used for 1GC and 3GC beacons to achieve ideal linearity [3].

- Experimental Titration: Titrate the target analyte across a wide concentration range using the simulated mixture. Measure the output signal and fit the data to a log-linear plot to confirm the dynamic range and adjust ratios if needed.

Step 3: Characterize Composite Sensor Performance

Once the optimal mixture is identified, perform a full characterization.

- Dynamic Range and Linearity: Confirm the log-linear range and calculate the R² value for linearity.

- Specificity Profile: Verify that the mixture maintains a constant and high specificity across the entire extended dynamic range [3].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ): Determine these key analytical parameters for the final mixture.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Developing Affinity-Tuned Biosensors

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Structure-Switching Receptors | Engineered receptors (e.g., molecular beacons, aptamers) where a non-binding conformation is stabilized to tune affinity without altering the binding site's specificity [3]. |

| Computational Design Software | Software platforms (e.g., Rosetta) for de novo protein design and for grafting target-binding domains into switchable scaffold proteins [28]. Tools like HotSpot Wizard can also identify engineering sites [29]. |

| Thermodynamic Modeling Tools | Custom or commercial software for simulating the dose-response of receptor mixtures to predict dynamic range and optimize mixing ratios before experimental testing [3]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Platform | Systems for rapidly expressing and screening many receptor variants and their mixtures for affinity, specificity, and signal output [4] [30]. |

| Myristoylated ARF6 (2-13) | Myristoylated ARF6 (2-13) Peptide|ARF6 Inhibitor |

| Exatecan analogue 1 | Exatecan analogue 1, MF:C23H20FN3O4, MW:421.4 g/mol |

Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: Our receptor mixture does not produce a log-linear response and instead shows a sigmoidal curve with a plateau in the middle. What is the cause? This "three-state" response pattern typically occurs when the difference in affinity between the combined receptor variants is too large (e.g., greater than 500-fold) [3]. The solution is to include one or more intermediate-affinity variants in the mixture to bridge the gap. Simulate the combined response of variants with smaller affinity increments (e.g., 10- to 100-fold differences) to restore log-linearity.

FAQ 2: The mixed sensor shows varying specificity or accuracy across its dynamic range. How can this be fixed? This issue arises if the receptor variants used in the mixture were generated by altering the target-binding site itself, which can inadvertently affect specificity [3]. Ensure all your affinity-tuned variants are generated via a structure-switching mechanism (e.g., by stabilizing a non-binding conformation). This approach decouples affinity from specificity, as the binding site itself remains chemically identical across all variants [3].

FAQ 3: The signal gain (fluorescence change) of our extended-range sensor is unacceptably low. How can we improve it? Low overall signal gain is often caused by including receptor variants with unstable non-binding states, which have a high background signal [3]. To correct this:

- Prioritize variants with high signal gain during the initial selection.

- Use non-equimolar mixing ratios, reducing the proportion of low-signal-gain variants in the mixture.

- Re-engineer your receptor variants to achieve a more favorable balance between affinity and signaling efficiency.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues

This technical support document provides a detailed guide for researchers working to extend the dynamic range of transcription factor-based biosensors, using the CaiF protein for L-carnitine detection as a specific case study. The CaiF transcription factor is notably activated by crotonobetainyl-CoA, a key intermediate in the carnitine metabolic pathway [4]. Capitalizing on this mechanism, sophisticated biosensors have been developed for metabolic engineering applications [4] [31]. The following sections address common experimental challenges and provide standardized protocols to facilitate robust biosensor engineering.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary limitation of wild-type CaiF biosensors that necessitates engineering? The wild-type CaiF biosensor has a relatively restricted detection range, which imposes specific limitations in practical application scenarios [4]. Without engineering, this narrow dynamic range can hinder precise monitoring and control of metabolic pathways in production strains.

Q2: What key engineering strategy was successfully used to expand the CaiF dynamic range? A "Functional Diversity-Oriented Volume-Conservative Substitution Strategy" was employed on key amino acid sites of CaiF [4]. This rational design approach, potentially informed by computer-aided design of the CaiF structure and DNA binding site simulations, yielded variants with significantly improved performance [4].

Q3: What performance metrics were achieved with the engineered CaiF variant? The biosensor based on the CaiFY47W/R89A double mutant exhibited a considerably expanded concentration response range from 0.0001 mM to 10 mM [4]. This represents a 1000-fold wider range and a 3.3-fold higher output signal intensity compared to the control biosensor [4].

Q4: How can I validate the functional expression of L-carnitine pathway enzymes in my host organism (e.g., E. coli)? A genetically encoded L-carnitine biosensor can be utilized to monitor pathway performance in a dose-dependent manner [31]. This provides a convenient method to screen for functional enzyme expression and cascade activity without the need for complex analytical equipment.

Q5: Why is an "entrepreneurial mindset" recommended in biosensor research? Adopting an entrepreneurial mindset during hypothesis formation helps ensure that research addresses a genuine need, is not duplicative, and produces a product that is readily translatable by industry [32]. This approach maximizes the real-world impact of biosensor development efforts.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Signal Intensity from Biosensor

| Possible Cause | Verification Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Expression | SDS-PAGE to check protein levels. | Optimize induction conditions (temperature, inducer concentration, timing). |

| Poor Ligand Binding | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC). | Re-visit computational design; perform alanine scanning on binding pocket [4]. |

| Inefficient Signal Transduction | Compare with a positive control system. | Engineer the linker region between DNA-binding and ligand-binding domains. |

Problem: High Background Signal (Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio)

| Possible Cause | Verification Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter Leakiness | Measure fluorescence in absence of ligand. | Use tighter inducible promoters or incorporate genetic insulators. |

| Non-specific Transcription Factor Binding | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP). | Mutate DNA-binding domain to enhance specificity [33]. |

| Host Cell Interference | Test biosensor in different strain backgrounds. | Use knockout strains for native regulators that might cross-talk. |

Problem: Narrow Dynamic Range

| Possible Cause | Verification Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Allosteric Regulation | Measure dose-response curves. | Apply directed evolution to the allosteric interface [4] [33]. |

| Saturation of Binding Sites | Determine binding affinity (Kd). | Use rational design, like volume-conservative substitutions, to modulate affinity [4]. |

| Cellular Mislocalization | Fluorescence microscopy with tagged protein. | Add appropriate localization tags or check for aggregation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Directed Evolution of CaiF for Expanded Dynamic Range

Purpose: To create CaiF variants with a wider response range to L-carnitine/crotonobetainyl-CoA.

Materials:

- Error-Prone PCR Kit

- Plasmid library containing mutated caiF genes

- Expression host (e.g., E. coli) with reporter (GFP) under CaiF-responsive promoter

- FACS or microplate reader

- L-carnitine (or precursor) for screening

Procedure:

- Generate Diversity: Create a mutant library of the caiF gene using error-prone PCR or site-saturation mutagenesis at targeted residues (e.g., Y47, R89) [4].

- Library Transformation: Transform the plasmid library into your microbial host strain.

- High-Throughput Screening:

- Plate cells on solid media or grow in liquid culture to express the mutant biosensors.

- Key Step: Challenge the population with a gradient of L-carnitine concentrations (e.g., from 0.001 mM to 50 mM).

- Using FACS or a microplate reader, isolate clones that show a functional response (e.g., GFP expression) at both the low and high ends of the concentration gradient. The goal is to find variants that are sensitive at low levels but do not saturate prematurely.

- Characterization: Isolate promising clones and characterize them by measuring the dose-response curve to determine the new operational range (EC50) and maximum output.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Biosensor Performance

Purpose: To generate a dose-response curve and calculate key performance metrics for engineered CaiF variants.

Materials:

- Engineered bacterial strains (wild-type and mutant CaiF)

- Black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well microplates

- Plate reader capable of measuring OD600 and fluorescence (e.g., GFP)

- L-carnitine stock solution for serial dilution

Procedure:

- Inoculation: Inoculate starter cultures of your biosensor strains and grow overnight.

- Induction & Induction: Dilute cultures and aliquot into the microplate. Add a serial dilution of L-carnitine across the plate. Include a no-ligand control.

- Incubation and Measurement: Grow the cultures with shaking in the plate reader, taking periodic measurements of OD600 and fluorescence.

- Data Analysis:

- Normalize fluorescence to OD600 for each well.

- Plot normalized fluorescence against the log of L-carnitine concentration.

- Fit the data to a sigmoidal curve (e.g., 4-parameter logistic model) to determine the EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration), Hill coefficient, and dynamic range (ratio between max and min signal).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Wild-type vs. Engineered CaiF Biosensor

| Biosensor Variant | Response Range (mM) | Dynamic Range (Fold Change) | Signal Intensity (Fold Increase) | Key Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type CaiF | Not specified in results | Baseline (Control) | Baseline (Control) | N/A |

| CaiF Y47W/R89A | 10â»â´ – 10 | 1000 | 3.3 | Y47W, R89A |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CaiF Biosensor Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Notes / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| CaiF Plasmid Library | Source of genetic diversity for directed evolution. | Can be generated via error-prone PCR or site-saturation mutagenesis. |

| Crotonobetainyl-CoA / L-carnitine | Native ligand / Biosensor inducer. | CaiF is activated by crotonobetainyl-CoA, an intermediate in L-carnitine metabolism [4]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter (e.g., GFP) | Quantitative output for biosensor activity. | Allows high-throughput screening via FACS or plate readers. |

| E. coli Production Chassis | Host for biosensor expression and testing. | Engineered E. coli strains can be used for de novo L-carnitine production [31]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Harnessing Directed Evolution and FACS for Biosensor Optimization

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Biosensor Performance

Q: My biosensor shows a weak output signal. What could be the cause? A: A weak signal can stem from several issues related to both the biosensor and your instrumentation. The biosensor itself may have suboptimal ligand-binding affinity or poor expression levels in your host system. Instrumentally, ensure your flow cytometer PMT voltages are set correctly for the fluorochrome used and that your antibody concentrations have been properly titrated. High background noise from cellular autofluorescence can also obscure a weak signal [34] [1].

Q: The dynamic range of my biosensor is too narrow for my application. How can I extend it? A: Narrow dynamic range is a common challenge. Directed evolution is a powerful strategy to address this. By creating a diverse library of biosensor variants, for instance, via site-saturation mutagenesis at key amino acid positions involved in ligand binding and signal transduction, and then screening this library using FACS for cells exhibiting both high ON-state and low OFF-state fluorescence, you can select variants with improved ranges. Research on a CaiF-based biosensor successfully used such a strategy to obtain a variant with a 1000-fold wider response range [4].