Engineering Life: How Standardization and Modularity are Revolutionizing Synthetic Biology for Drug Development

This article explores the pivotal role of engineering principles, specifically standardization and modularity, in advancing synthetic biology for biomedical applications.

Engineering Life: How Standardization and Modularity are Revolutionizing Synthetic Biology for Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the pivotal role of engineering principles, specifically standardization and modularity, in advancing synthetic biology for biomedical applications. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational concepts of biological part standardization and chassis engineering, details the implementation through automated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles in biofoundries, and addresses critical challenges in predictability and systems integration. Further, it examines real-world validation in therapeutic production and biosensing, highlighting how these principles accelerate the development of personalized medicines, on-demand therapeutics, and sophisticated diagnostic tools, ultimately shaping the future of biomedicine.

The Engineering Paradigm: Foundational Principles of Biological Standardization and Modularity

The field of synthetic biology is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from artisanal tinkering towards a future of predictable engineering. This shift is underpinned by the core engineering principles of standardization, abstraction, and modularity, which aim to make biological systems easier to design, model, and implement [1] [2]. Historically, the construction of biological systems has been hampered by context-dependent effects, cellular resource limitations, and an overall lack of predictability [3] [2]. The emerging discipline of predictive biology seeks to overcome these challenges by integrating diverse expertise across biology, physics, and engineering, resulting in a quantitative understanding of biological design [3].

A crucial goal is to apply engineering principles to biotechnology to make life easier to engineer [1]. This involves a hierarchical organization of biological complexity, where well-characterized DNA "parts" are combined into "devices," which are then integrated into larger "circuits" or "systems" that perform complex functions [1]. The successful use of modules in engineering is expected to be reproduced in synthetic biological systems, though this requires a deep understanding of both the similarities and fundamental differences between man-made and biological modules [1]. This whitepaper explores the key quantitative methods, experimental validations, and computational tools that are enabling this transformative shift.

Quantitative Foundations for Prediction

The predictability of a biological design is fundamentally constrained by the cellular economy. Engineering complex functions often involves the expression of multiple synthetic genes, which compete for finite cellular resources such as free ribosomes, nucleotides, and energy [3]. This competition can lead to unexpected couplings between seemingly independent circuits and a failure to achieve the desired output.

Key Principles of Resource Allocation

Quantitative studies have elucidated several key principles that govern resource allocation and its impact on predictability. The following table summarizes the core concepts and their experimental validations:

| Concept | Description | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Ribosome Allocation | Expression of synthetic genes is limited by the concentration of free ribosomes, creating a trade-off between endogenous and synthetic gene expression [3]. | Empirical models show that ribosome allocation limits the growth rate and maximal expression of synthetic genes [3]. |

| Expression Burden | High expression of synthetic circuits can overburden the host cell, reducing viability and circuit performance [3] [4]. | Quantifying cellular capacity identifies gene expression designs with reduced burden, improving predictability and long-term stability [3]. |

| Indirect Coupling | Competition for shared resources creates hidden interactions between co-expressed genes, making their combined output unpredictable from their individual behaviors [3]. | Computational and experimental strategies, such as tuning mRNA decay rates and using orthogonal ribosomes, successfully reduce this coupling [3]. |

Mathematical Frameworks for Modeling

To manage this complexity, quantitative frameworks have been developed. The concept of "isocost lines" describes the cellular economy of genetic circuits, graphically representing the trade-offs in resource allocation when expressing multiple genes [3]. Furthermore, the relationship between resource availability and gene expression has been formalized in a minimal model of ribosome allocation dynamics, which accurately captures the observed trade-offs [3]. These models transform biology from a descriptive science into a predictive one, allowing engineers to simulate system behavior before physical construction.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Modularity and Predictability

A critical step in the engineering cycle is the experimental validation of designed systems. The following section details a standardized methodology for quantifying the modularity of biological components, a foundational requirement for predictable engineering.

Protocol: Quantifying Context-Dependence of Promoter Activity

This protocol assesses whether a promoter's activity remains consistent when placed in different genetic contexts, a key aspect of modularity [2].

- Objective: To measure the activity variation of a set of promoters when characterized via different biological measurement systems.

- Materials:

- Strain: E. coli TOP10.

- Promoters: A set of five constitutive promoters of varying strengths (e.g., BBaJ23100, BBaJ23101, BBaJ23106, BBaJ23107, BBaJ23114).

- Reporter Devices: Three reporter expression devices combining different fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP) and Ribosome Binding Sites (RBSs BBaB0032 and BBaB0034).

- Plasmids: Low-copy and high-copy number plasmid backbones.

- Reference Standard: A standard in vivo reference promoter (e.g., BBaJ23101) for normalization.

- Method:

- Assembly: Assemble each promoter upstream of each reporter device in both low-copy and high-copy plasmid vectors.

- Transformation: Transform each constructed plasmid into the E. coli host strain.

- Cultivation and Measurement: Grow three biological replicates for each construct under defined conditions. For induced promoters, use 1 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Measure fluorescence output using a flow cytometer or plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Relative Promoter Unit (RPU) for each construct by normalizing its fluorescence output to that of the standard reference promoter measured in the same experimental conditions [2].

- Validation: The promoter activity is considered modular if the calculated RPU values for a given promoter are not statistically different (p ≥ 0.05, ANOVA) across the different measurement systems (reporter genes, RBSs, and plasmid copy numbers) [2]. This protocol revealed that while some promoters show high consistency (low context-dependence), others exhibit significant variability, defining the boundaries of their modular application.

Workflow: The Systems Biology Modeling Cycle

The iterative cycle of model-building and experimental validation is central to predictive biology. The BioPreDyn project formalized this into a "systems-biology modeling cycle" supported by integrated software tools [5]. The workflow below illustrates this iterative process for developing predictive dynamic models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The advancement of predictive biological design relies on a suite of standardized materials and computational tools. The following table catalogs essential resources for researchers in this field.

| Category | Item/Solution | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Biological Parts | BioBricks [1] [2] | Standardized DNA parts (promoters, RBSs, coding sequences) that facilitate the modular assembly of genetic circuits. |

| Measurement Standards | Relative Promoter Unit (RPU) [2] | A standardized unit for quantifying promoter activity relative to a reference standard, enabling reproducible measurements across labs. |

| Software & Modeling Tools | BioPreDyn Software Suite [5] | An integrated framework supporting the entire modeling cycle, including parameter estimation, identifiability analysis, and optimal experimental design. |

| CellNOptR [5] | A toolkit for training protein signaling networks to data using logic-based formalisms. | |

| Standardized Metabolic Models | Consensus Yeast Metabolic Network (yeast.sf.net) [5] | Community-curated, genome-scale metabolic reconstructions for key model organisms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae. |

| Data Analysis Methods | Structure-Augmented Regression (SAR) [4] | A machine learning platform that learns the low-dimensional structure of a biological response landscape to enable accurate prediction with minimal data. |

| 4-chloro-1H-indol-7-ol | 4-Chloro-1H-indol-7-ol|RUO | 4-Chloro-1H-indol-7-ol is a chemical building block for pharmaceutical and biochemical research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 6-(Oxetan-3-YL)-1H-indole | 6-(Oxetan-3-YL)-1H-indole, MF:C11H11NO, MW:173.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Computational and Machine Learning Approaches

As biological systems and the questions asked of them grow in complexity, purely mechanistic models can become limiting. This has spurred the development of advanced data-driven modeling and control strategies.

Exploiting Low-Dimensional Structure with Machine Learning

A significant challenge in predicting biological responses to multi-factor perturbations (e.g., drug combinations, nutrient variations) is the exponential number of possible experiments required. A novel machine learning platform, Structure-Augmented Regression (SAR), addresses this by exploiting the intrinsic, low-dimensional structure of biological response landscapes [4]. SAR first learns the characteristic structure of a system's response (e.g., the boundary between high and low output states) from limited data. This learned structure is then used as a soft constraint to guide subsequent quantitative predictions of the full response landscape. This approach has been shown to achieve high prediction accuracy with significantly fewer data points than other machine-learning methods on systems ranging from microbial communities to drug combination responses [4].

Comparison of Data-Driven Control Strategies

For the real-time control of biotechnological processes (e.g., bioreactors), two primary data-driven optimal control strategies are emerging: Data-Driven Model Predictive Control (MPC) and Model-Free Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) [6]. A quantitative comparison reveals a trade-off between data efficiency and final performance. The table below summarizes their characteristics based on applications in chemical and biological processes:

| Feature | Data-Driven MPC | Model-Free DRL |

|---|---|---|

| Core Learning Target | A dynamic model of the system [6]. | The value function or control policy directly [6]. |

| Data Efficiency | High performance with less data; efficient learning [6]. | Requires more interaction data to learn; less data-efficient [6]. |

| Maximum Attainable Performance | Superior and reliably high in standard processes [6]. | Can match or exceed MPC in complex, non-linear systems [6]. |

| Handling of Constraints | Explicit and reliable [6]. | Challenging, with no strong guarantees [6]. |

| Applicable Data Type | Primarily open-loop data; closed-loop identification is difficult [6]. | Can learn from closed-loop operational data [6]. |

The Future: Generative Biology and AI-Driven Design

The next frontier in biological design is the move from predictive to generative biology, where artificial intelligence (AI) is used not just to model, but to design biological systems from first principles [7]. Generative AI models are trained on vast datasets of genetic sequences, allowing them to learn the underlying patterns and rules of biology. Once trained, these models can be used to design novel DNA and protein sequences with user-specified properties, such as optimized gene expression, new therapeutic proteins, or enzymes with novel functions [7].

This approach is being pioneered in initiatives like the Generative and Synthetic Genomics research programme, which aims to build foundational datasets and models to engineer biology with a level of precision comparable to electronics [7]. This paradigm shift promises to drastically accelerate the design-build-test cycle, moving biology from a descriptive and tinkering discipline to a truly predictive and generative engineering science. As with all powerful technologies, this progression necessitates the parallel development of robust ethical frameworks to guide its responsible application [7].

Synthetic biology represents a fundamental shift in the life sciences, applying rigorous engineering principles to the design and construction of biological systems. This emerging discipline aims to make biology easier to engineer by creating standardized, modular components that can be reliably assembled into complex, predictable systems [8] [9]. The core framework of synthetic biology rests upon three foundational concepts: standard biological parts (the basic functional units), chassis (the host organisms that harbor engineered systems), and abstraction hierarchies (the methodological approach that manages biological complexity) [9]. This tripartite toolkit enables researchers to move beyond traditional genetic manipulation toward true engineering of biological systems with predictable behaviors.

The paradigm of synthetic biology draws direct inspiration from more established engineering fields, particularly computer engineering. In this analogy, biological parts correspond to electronic components, cellular chassis serve as the hardware platform, and abstraction hierarchies provide the organizational framework that allows engineers to work at appropriate complexity levels without being overwhelmed by underlying details [9]. This engineering-driven approach has enabled the construction of increasingly sophisticated biological systems, including genetic switches, oscillators, logic gates, and complex metabolic pathways [10] [8]. As the field advances, the continued refinement of this toolkit promises to transform biotechnology applications across medicine, agriculture, industrial manufacturing, and environmental sustainability [11] [8].

Standard Biological Parts: The Building Blocks of Synthetic Biology

Definition and Classification

Standard biological parts are functional units of DNA that encode defined biological functions and adhere to physical assembly standards [12]. These parts are designed to be modular, interoperable, and characterized, allowing researchers to combine them in predictable ways to create novel biological systems [9]. The Registry of Standard Biological Parts, established at MIT, maintains and distributes thousands of these standardized components, providing the foundational infrastructure for the synthetic biology community [12].

Biological parts can be categorized by their functional roles in engineered systems:

- Promoters: DNA sequences that initiate transcription, serving as key regulatory control points [12]

- Protein-coding sequences: Genes that specify the amino acid sequences of proteins

- Terminators: Sequences that signal the end of transcription

- Ribosome binding sites: Elements that control translation initiation in prokaryotes

- Non-coding RNAs: Regulatory RNAs that control gene expression at post-transcriptional levels [10] [9]

The functional composition of these parts enables the construction of devices that perform defined operations, such as logic gates, switches, and oscillators, which can be further combined into complex systems [8] [9].

Characterization and Measurement Standards

A critical challenge in synthetic biology is the quantitative characterization of biological parts. Unlike electronic components with standardized specifications, biological parts exhibit context-dependent behavior that varies with cellular environment, growth conditions, and genetic background [12]. To address this challenge, researchers have developed standardized measurement units and reference standards.

The Relative Promoter Unit (RPU) was established as a standard unit for reporting promoter activity, defined relative to a reference promoter (BBa_J23101) [12]. This approach reduces variation in reported promoter activity due to differences in test conditions and measurement instruments by approximately 50%, enabling comparable measurements across laboratories and experimental conditions [12]. Similarly, the conceptual Polymerases Per Second (PoPS) unit provides a standardized way to describe promoter activity in terms of RNA polymerase molecules that clear the promoter per second, creating a universal metric for transcription initiation rates [12].

Table 1: Standard Units for Characterizing Biological Parts

| Unit of Measurement | Biological Function Measured | Definition | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Promoter Unit (RPU) | Promoter activity | Activity relative to reference promoter BBa_J23101 | BBa_J23101 constitutive promoter |

| Polymerases Per Second (PoPS) | Transcription initiation rate | Number of RNA polymerases clearing promoter per second | Not applicable (conceptual unit) |

| Miller Units | β-galactosidase activity | Protocol-dependent measure of enzyme activity | Requires calibration against common standard |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Promoter Activity

Accurate characterization of promoter parts follows a standardized experimental workflow:

Plasmid Construction: Clone the test promoter upstream of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding sequence in a standardized BioBrick vector [12].

Reference Standard Preparation: Include a control plasmid containing the reference promoter (BBa_J23101) driving GFP expression in parallel experiments [12].

Cell Culture and Measurement:

- Transform plasmids into appropriate host cells (typically E. coli)

- Grow cultures under defined conditions (media, temperature, aeration)

- Measure GFP fluorescence and optical density at regular intervals

- Calculate GFP synthesis rates from fluorescence trajectories [12]

Data Analysis:

- Compute promoter activity in absolute fluorescence units

- Normalize to reference promoter activity: RPU = (Test promoter activity)/(Reference promoter activity)

- Report results with appropriate metadata (growth phase, media, strain background) [12]

This protocol emphasizes the importance of parallel measurements with reference standards to account for experimental variability and enable cross-laboratory data comparison.

Chassis Organisms: Host Platforms for Engineered Systems

Concept and Selection Criteria

In synthetic biology, a chassis refers to the host organism that provides the foundational cellular machinery for engineered biological systems [13]. The chassis supplies essential functions including transcription, translation, metabolism, and cellular replication, creating the context in which engineered parts and devices operate [9]. Selection of an appropriate chassis is critical to the success of synthetic biology applications and depends on multiple factors:

- Genetic stability: Ability to maintain engineered genetic constructs without mutation

- Metabolic compatibility: Native metabolic networks that support engineered functions

- Growth characteristics: Doubling time, achievable cell density, and nutrient requirements

- Regulatory considerations: Safety profile and regulatory status for intended application

- Tool availability: Existence of genetic tools for manipulation and characterization [13]

The ideal chassis provides a "clean background" with minimal interference with engineered systems while supplying all essential cellular functions reliably and predictably.

Conventional and Next-Generation Chassis

Traditional synthetic biology has relied on well-characterized model organisms with extensive toolboxes for genetic manipulation. However, recent advances have expanded the range of available chassis to include non-conventional organisms with specialized capabilities.

Table 2: Comparison of Chassis Organisms for Synthetic Biology

| Chassis Organism | Key Features | Advantages | Applications | Genetic Tools Available |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Gram-negative bacterium | Extensive characterization, rapid growth, well-developed tools | Protein production, metabolic engineering, genetic circuit design | Comprehensive toolkit available |

| Bacillus subtilis | Gram-positive bacterium | Protein secretion capability, generally regarded as safe (GRAS) status | Industrial enzyme production | Standardized parts developing |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Eukaryotic yeast | Complex cellular organization, GRAS status | Metabolic engineering, eukaryotic protein production | Well-developed genetic tools |

| Halomonas spp. | Halophilic bacterium | Contamination resistance, low-cost cultivation | Industrial biomanufacturing under non-sterile conditions | Tools under active development [13] |

The development of Halomonas species as next-generation industrial biotechnology (NGIB) chassis represents significant progress in expanding the chassis repertoire [13]. These halophilic (salt-tolerant) bacteria enable growth under high-salt conditions where most microorganisms cannot survive, minimizing contamination risks and allowing cultivation under open, non-sterile conditions [13]. This capability dramatically reduces production costs by eliminating the need for energy-intensive sterilization procedures and enabling the use of low-cost bioreactors [13]. Halomonas bluephagenesis TD01 has emerged as a particularly promising chassis, demonstrating high yields of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) bioplastics (64.74 g/L) with productivity of 1.46 g/L/h under continuous cultivation in seawater [13].

Chassis-Device Compatibility: A Central Challenge

A fundamental challenge in synthetic biology is the unpredictable interaction between engineered genetic devices and their host chassis [10] [9]. Unlike engineered systems where components are designed to be orthogonal, biological parts interact with native cellular networks through multiple mechanisms:

- Metabolic burden: Engineered systems consume cellular resources (ATP, nucleotides, amino acids) that would otherwise support host functions [9]

- Unexpected regulatory cross-talk: Host transcription factors may regulate engineered sequences, and engineered regulators may affect host genes [10]

- Toxic effects: Overexpression of foreign proteins may stress cellular quality control systems [9]

- Evolutionary instability: Engineered constructs without selective advantage may be lost during cell division [9]

Strategies to address these compatibility issues include engineering orthogonal systems that minimize interaction with host networks, using regulatory systems from distantly related organisms, and implementing dynamic control systems that balance metabolic load [10]. The development of more predictable chassis-device integration represents an active area of research in synthetic biology.

Abstraction is a fundamental engineering strategy for managing complexity by hiding detailed information at lower levels while providing simplified representations at higher levels [9]. In synthetic biology, abstraction enables researchers to work with biological systems without requiring complete knowledge of underlying molecular details. The synthetic biology abstraction hierarchy typically includes:

- DNA Parts: The lowest level consisting of actual DNA sequences (promoters, coding sequences, etc.)

- Devices: Functional units created by combining multiple parts (logic gates, switches, sensors)

- Systems: Complex functional assemblies created by combining devices (metabolic pathways, communication systems)

- Multicellular Consortia: Populations of engineered cells coordinating to perform complex tasks [9]

Each level of the hierarchy uses standardized interfaces that allow components to be connected without considering internal details, enabling specialization and division of labor in engineering biological systems [9].

Information Encapsulation and Standard Interfaces

The power of abstraction hierarchies depends on effective information encapsulation between levels. At each level, components should exhibit predictable behavior without requiring knowledge of internal implementation details [9]. This approach allows researchers with different expertise to collaborate effectively – for example, a specialist designing a genetic circuit need not understand the detailed biochemistry of protein-DNA interactions, just as a software engineer need not understand transistor physics.

Standardized interfaces are crucial for enabling abstraction in biological systems. BioBrick parts use standardized flanking sequences that enable physical assembly regardless of the specific biological function [12]. However, true functional abstraction requires more than physical compatibility – it demands predictable functional composition where the behavior of composite systems can be reliably predicted from characterized components [12]. Achieving this level of predictability remains a significant challenge in synthetic biology due to context-dependent effects in biological systems.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The synthetic biology toolkit encompasses both biological and computational resources that enable the design, construction, and testing of engineered biological systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Synthetic Biology

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Assembly Standards | BioBrick, Golden Gate, MoClo | Standardized physical assembly of DNA parts | BioBrick provides simplest standardization for educational use [12] |

| Genetic Toolkits | Plasmid vectors, CRISPR-Cas systems, transposons | Genetic manipulation of chassis organisms | Tool availability varies by chassis [13] |

| Measurement Standards | Reference promoters, fluorescent proteins, assay protocols | Quantitative characterization of parts and devices | RPU system enables cross-lab comparisons [12] |

| Software Tools | Genetic circuit design tools, modeling platforms, data repositories | In silico design and simulation | Increasingly integrated with AI/ML approaches [14] |

| Automation Platforms | Liquid handlers, colony pickers, high-throughput screeners | Scaling design-build-test-learn cycles | Essential for advanced metabolic engineering [15] |

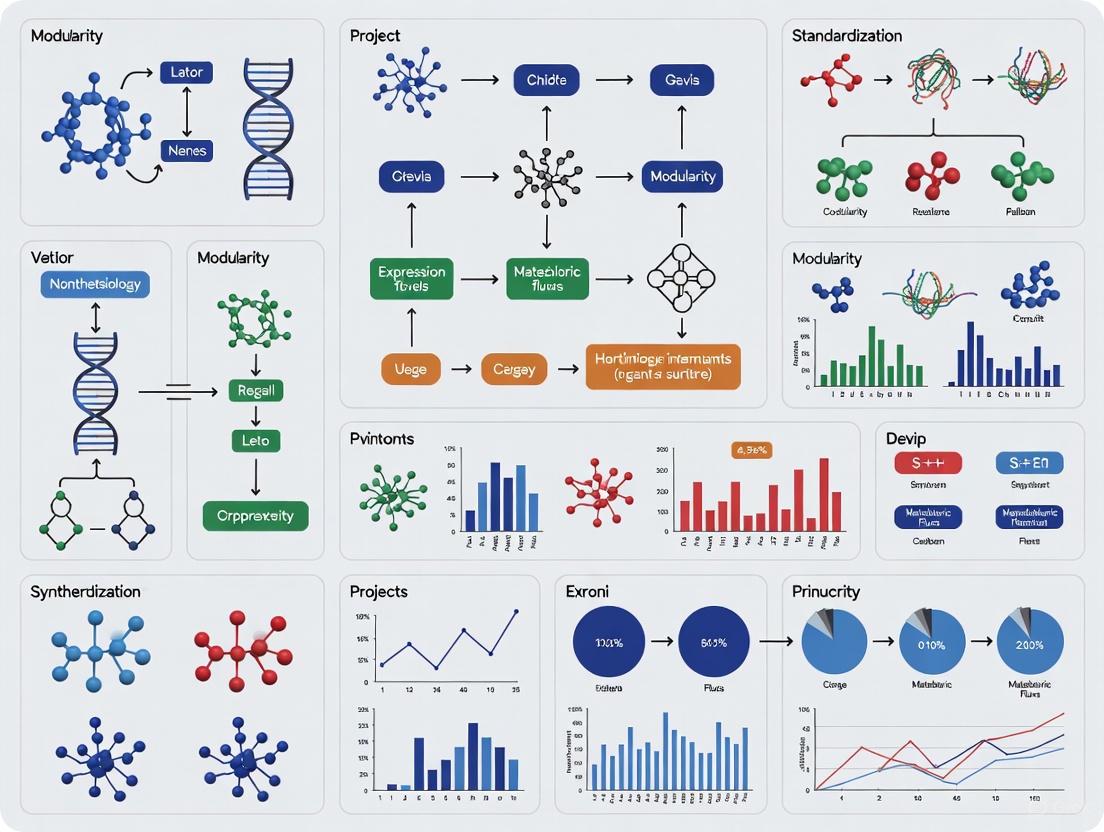

The following diagram illustrates the abstraction hierarchy in synthetic biology, showing how basic biological parts are combined into increasingly complex systems:

Synthetic Biology Abstraction Hierarchy

This hierarchical organization enables researchers to work at appropriate levels of complexity, with lower-level details encapsulated behind standardized interfaces.

Future Directions and Challenges

Expanding the Standardized Toolkit

Current research aims to expand the synthetic biology toolkit in several key directions. The development of non-traditional chassis organisms like Halomonas represents progress toward specialized platforms for industrial applications [13]. Similarly, the creation of synthetic genetic codes using non-natural amino acids promises to expand the chemical functionality of biological systems [10]. These advances require parallel development of standardized parts and characterization methods tailored to new chassis and applications.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with synthetic biology represents another frontier [14]. AI-driven tools can accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle by predicting part behavior, optimizing genetic designs, and identifying context effects that impact system performance [14]. As these tools mature, they may help overcome the predictability challenges that currently limit the scale and complexity of engineered biological systems.

Standardization and Interoperability

Global efforts to develop standardization frameworks for synthetic biology are underway, led by institutions including the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the United States, the Centre for Engineering Biology Metrology and Standards in the United Kingdom, and the International Cooperation for Synthetic Biology Standardization Project (BioRoBoost) in the European Union [16]. These initiatives aim to establish common standards for data, measurement, and characterization that will enable reliable integration of components from different sources and applications.

However, significant challenges remain in achieving true interoperability. Biological systems exhibit inherent context-dependence that complicates standardization efforts [10] [12]. Additionally, the rapid expansion of synthetic biology applications across diverse sectors necessitates specialized standards for different implementation contexts, from clinical therapeutics to environmental remediation [16]. Addressing these challenges will require ongoing collaboration between researchers, industry partners, and regulatory bodies across international boundaries.

The synthetic biology toolkit of standard biological parts, chassis organisms, and abstraction hierarchies provides a powerful framework for engineering biological systems with defined functions. While significant progress has been made in developing each component of this toolkit, challenges remain in achieving true predictability and reliability in engineered biological systems. The continued refinement of standardized parts, expansion of chassis options, and development of more effective abstraction methods will enable increasingly sophisticated applications across medicine, manufacturing, agriculture, and environmental sustainability. As the field advances, the integration of computational design tools and automated experimental platforms promises to accelerate the engineering cycle, potentially democratizing biological design capabilities and transforming our relationship with the living world.

The concept of genome modularity represents a fundamental architectural principle in biological systems, where genetic elements are organized into functional units that operate semi-independently to control specific phenotypic outcomes. This paradigm is crucial for understanding how complex biological functions emerge from genetic information and provides a powerful framework for synthetic biology applications. In essence, modularity in genetic systems describes the organization of genes into discrete functional groups where elements within a module interact extensively but maintain limited connections with elements in other modules [17]. This architecture enables biological systems to evolve and adapt more efficiently by allowing modifications within one module without disrupting the entire system.

The principles of modularity are deeply rooted in engineering disciplines and have been successfully applied to synthetic biology to streamline the design and construction of biological devices. The core premise involves treating biological components as standardized parts that can be assembled in various configurations to produce predictable outcomes [18]. This approach mirrors strategies used in other engineering fields where complex systems are built from interchangeable, well-characterized components. The application of modularity principles to biological systems has transformed our ability to program cellular behavior and engineer novel biological functions [19].

From an evolutionary perspective, modular genetic architectures are favored when organisms face complex spatial and temporal environmental challenges [17]. Theoretical models predict that modular organization allows populations to adapt more efficiently to multiple selective pressures simultaneously. When mutations are subject to the same selection pressure, clustering of adaptive loci in genomic regions with limited recombination can be advantageous, while selection acts to increase recombination between genes adapting to different environmental factors [17]. This evolutionary insight provides a foundation for understanding the natural genetic architecture that synthetic biologists seek to harness and emulate.

Theoretical Framework of Genetic Modules

Defining Genetic Modules and Their Properties

Genetic modules can be formally defined as sets of genetic elements that work together to perform a specific function, with minimal interference from or effect on other modules within the system. These modules exhibit key properties that distinguish them from random collections of genetic elements, including functional coherence, limited pleiotropy, and encapsulated interfaces. The theoretical underpinnings of genetic modularity suggest that modules arise through evolutionary processes that favor organizations where components within a module have high functional connectivity while maintaining limited cross-talk with external elements [17].

A crucial aspect of module definition involves understanding pleiotropy—the phenomenon where a single gene influences multiple distinct traits. From a modularity perspective, extensive pleiotropy can hinder adaptation by creating genetic constraints [17]. Modular architectures suppress pleiotropic effects between different functional units while allowing extensive pleiotropy within modules. This organization allows adaptation to occur in one trait without undoing the adaptation achieved by another trait, particularly important when traits are under stabilizing selection within populations but directional selection among populations [17].

The property of linkage among genetic elements is another fundamental consideration in module definition. Theory predicts that when local adaptation is driven by complex and non-covarying stresses, increased linkage is favored for alleles with similar pleiotropic effects, while increased recombination is favored among alleles with contrasting pleiotropic effects [17]. This principle explains why genes involved in related functions are often found in close genomic proximity or within the same regulatory networks, forming the physical basis for genetic modules.

Types of Genetic Modules and Their Functions

Genetic modules can be categorized based on their organizational principles and functional roles within biological systems. The major types include:

- Gene regulatory modules: Collections of genes controlled by common regulatory elements that coordinate expression in response to specific signals.

- Metabolic pathway modules: Enzyme-coding genes that function in consecutive biochemical reactions to transform substrates into products.

- Protein complex modules: Genes encoding subunits of multi-protein assemblies that work together as functional units.

- Signaling modules: Components of signal transduction pathways that process environmental or intracellular information.

- Structural modules: Genes encoding physically associated components that form cellular structures.

Table: Classification of Genetic Module Types and Their Characteristics

| Module Type | Primary Function | Key Components | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory | Coordinate gene expression | Transcription factors, cis-regulatory elements | toggle switch, oscillators |

| Metabolic | Transform biochemical compounds | Enzymes, transporters | artemisinin pathway |

| Signaling | Process environmental information | Receptors, kinases, phosphatases | two-component systems |

| Structural | Form cellular architecture | Cytoskeletal proteins, cell wall components | flagellar motor |

| Protein Complex | Execute coordinated functions | Multiple subunit proteins | ribosome, RNA polymerase |

| Protegrin-1 | Protegrin-1, MF:C88H147N37O19S4, MW:2155.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (S)-TCO-PEG2-Maleimide | (S)-TCO-PEG2-Maleimide, MF:C22H33N3O7, MW:451.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The functional significance of these modules lies in their ability to perform defined operations that can be reused in different contexts. For instance, synthetic biology has successfully engineered genetic toggle switches and oscillators that function as regulatory modules [18]. These modules maintain their core functionality when transferred between different genetic backgrounds, demonstrating the principle of modularity in practice.

Computational Approaches for Mining Genetic Modules

Matrix Factorization Methods for Module Identification

Matrix factorization techniques have emerged as powerful computational tools for identifying functional gene modules from large-scale genomic data. These methods decompose complex genetic association matrices into lower-dimensional representations that reveal underlying modular structures. Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF) has been particularly successful in this domain due to its ability to produce interpretable parts-based representations and handle the sparse, high-dimensional data typical in genomics [20].

The fundamental NMF approach for mining functional gene modules involves factorizing a gene-phenotype association matrix to derive cluster indicator matrices for both genes and phenotypes. Given a nonnegative matrix A ∈ â„^(n×m) representing associations between n genes and m phenotypes, NMF approximates this matrix as the product of two lower-dimensional matrices: A ≈ GP, where G ∈ â„^(n×k) represents the gene cluster indicator matrix, and P ∈ â„^(k×m) represents the phenotype cluster indicator matrix [20]. The factorization is achieved by minimizing the following objective function:

L({}{NMF})(G,P) = ||A - GP||²({}{F}

where ||·||({}_{F}) denotes the Frobenius norm. This basic formulation can be enhanced by incorporating additional biological constraints to improve the biological relevance of the identified modules.

Consistent Multi-view Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (CMNMF) represents an advanced extension that leverages the hierarchical structure of phenotype ontologies to identify more biologically meaningful gene modules [20]. This approach simultaneously factorizes gene-phenotype association matrices from different levels of the phenotype ontology hierarchy while enforcing consistency constraints across levels. The CMNMF framework incorporates: (1) separate factorization of association matrices at parent and child levels of the phenotype hierarchy, (2) consistency constraints ensuring gene clusters derived from different hierarchy levels are identical, and (3) phenotype mapping constraints that enforce consistency between learned phenotype embeddings at different hierarchical levels [20].

Table: Comparison of Matrix Factorization Methods for Genetic Module Mining

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic NMF | Parts-based representation, nonnegativity constraints | Interpretable results, handles high-dimensional data | Does not incorporate biological constraints |

| GNMF | Incorporates graph Laplacian constraints | Preserves local geometric structure | Limited to single view of data |

| ColNMF | Shared coefficient matrix across multiple views | Identifies consistent patterns across data types | Does not exploit hierarchical relationships |

| CMNMF | Multi-view factorization with hierarchical consistency | Leverages phenotype ontology structure, improves biological relevance | Computational complexity, parameter tuning |

Network-Based and Hierarchical Approaches

Beyond matrix factorization, network-based methods provide powerful alternatives for identifying genetic modules by representing biological systems as graphs where nodes represent genetic elements and edges represent functional relationships. These approaches can naturally capture the complex interconnectivity within biological systems and identify densely connected subnetworks that correspond to functional modules.

A significant advancement in module mining involves leveraging the hierarchical structure of biological ontologies. Methods like Hierarchical Matrix Factorization (HMF) incorporate ontological relationships by constraining the embedding of child-level phenotypes to be informed by their parent-level phenotypes [20]. This approach recognizes that phenotypic annotations exist at different levels of granularity, and leveraging these hierarchical relationships can improve the biological relevance of identified gene modules.

Graph-regularized NMF variants incorporate network information as constraint terms in the factorization objective. For example, Graph Regularized Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (GNMF) incorporates a Laplacian constraint based on phenotype similarity graphs to enforce that correlated phenotypes share similar latent representations [20]. Similarly, GC²NMF extends this approach by introducing weighted graph constraints that vary with the depth of phenotypes in the ontology hierarchy, giving more importance to lower-level phenotypes whose associations are typically more informative [20].

The experimental workflow for computational module mining typically involves several standardized steps: data collection and preprocessing, construction of association matrices, application of clustering or factorization algorithms, validation of identified modules using independent biological data, and functional interpretation through enrichment analysis. This pipeline has been successfully applied to both model organisms and humans, demonstrating its generalizability across species [20].

Experimental Methodologies for Module Validation

Protocol for Co-association Network Analysis

Co-association network analysis provides a robust experimental framework for validating computational predictions of genetic modules and characterizing their environmental interactions. This methodology is particularly valuable for studying local adaptation to complex environmental factors, where multiple selective pressures may act on interconnected genetic modules [17]. The protocol involves systematic steps from data collection through network construction and interpretation:

Step 1: Candidate SNP Identification - Identify candidate single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) through univariate associations between allele frequencies and environmental variables. Significance thresholds should be established through comparison with neutral expectations, typically using methods such as genome-wide association studies or environmental association analysis [17].

Step 2: Hierarchical Clustering - Perform hierarchical clustering of candidate SNPs based on their association patterns across multiple environmental variables. This clustering groups loci with similar response profiles to different environmental factors, providing the initial evidence for modular organization [17].

Step 3: Network Construction - Construct co-association networks where nodes represent loci and edges represent similar association patterns across environments. Network visualization reveals clusters of loci that may covary with one environmental variable but exhibit different patterns with other variables, highlighting relationships not evident through univariate analysis alone [17].

Step 4: Module-Environment Mapping - Define distinct aspects of the selective environment for each module through their specific environmental associations. This mapping allows inference of pleiotropic effects by examining how SNPs associate with different selective environmental factors [17].

Step 5: Recombination Analysis - Analyze recombination rates among candidate genes in different modules to test evolutionary predictions about linkage relationships. Theory suggests that loci experiencing different sources of selection should have high recombination between them, while those responding to similar pressures may show reduced recombination rates [17].

This protocol has been successfully applied to study local adaptation to climate in lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), identifying multiple clusters of candidate genes associated with distinct environmental factors such as aridity and freezing while demonstrating low recombination rates among some candidate genes in different clusters [17].

Co-association Network Analysis Workflow

Functional Validation Through Phenomic Analysis

Phenomic analysis provides a complementary approach to validate genetic modules by systematically examining the relationship between modular organization and phenotypic outcomes. This methodology is particularly valuable for understanding human disease genetics, where modular nature of complex disorders can be attributed to clinical feature overlaps associated with mutations in different genes that are part of the same biological module [21].

The experimental protocol for phenomic analysis involves:

Phenotype Matrix Construction - Create a binary matrix where rows represent diseases or genetic variants and columns represent clinical features. Assign a value of '1' for presence and '0' for absence of each clinical feature associated with each genetic entity [21]. This matrix representation enables computational analysis of phenotype-genotype relationships.

Semantic Normalization - Map clinical feature terms to standardized concepts using biomedical ontologies such as the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS). This step addresses inconsistencies in clinical terminology and enables integration of data from multiple sources [21]. Natural language processing tools like MetaMap can automate this process by mapping free-text descriptions to controlled concepts.

Dimensionality Reduction - Apply principal components analysis (PCA) or other dimensionality reduction techniques to address the high dimensionality and sparsity of phenotypic data. Selecting the optimal number of principal components balances information retention with computational efficiency [21].

Similarity Measurement and Clustering - Calculate similarity between genetic entities using appropriate distance metrics applied to the reduced-dimensionality data. Hierarchical clustering then groups diseases or genes based on phenotypic similarity, revealing modules with shared phenotypic profiles [21].

Validation Through Genomic Correlations - Validate identified modules by testing for correlations with independent genomic data, including shared protein domains, common pathway membership, or similar Gene Ontology annotations. This validation confirms that phenotypic similarity reflects underlying genetic and functional relationships [21].

This approach has demonstrated that phenotypic similarities correlate with multiple levels of gene annotations, supporting the biological significance of genetically identified modules and providing functional validation of their organization [21].

Applications in Synthetic Biology and Drug Development

Engineering Synthetic Genetic Circuits

The principles of genome modularity form the foundation for engineering synthetic genetic circuits—networks of genes and regulatory elements designed to perform specific functions within cellular systems. These circuits represent the practical implementation of modular design in synthetic biology, enabling programmed control of cellular behavior for biotechnological and therapeutic applications [18].

Genetic toggle switches constitute one of the earliest and most fundamental examples of synthetic genetic modules. A classic implementation in E. coli consists of two repressors and two constitutive promoters arranged in a mutually inhibitory configuration [18]. Each promoter is inhibited by the repressor transcribed by the opposing promoter, creating a bistable system that can be switched between stable states using chemical inducers. The mathematical model describing this system accounts for repressor concentrations, synthesis rates, and cooperativity of repression to ensure bistability [18]. This modular design principle has been extended to create more complex logical operations in cellular systems.

Genetic oscillators represent another important class of synthetic modules that implement dynamic behaviors. Early implementations used three transcriptional repressors in a negative feedback loop, with mathematical models predicting conditions that favor sustained oscillations [18]. More advanced designs incorporate both negative and positive feedback loops to create tunable oscillators with adjustable periods. For example, a dual-feedback circuit oscillator utilizes three copies of a hybrid promoter driving expression of araC, lacI, and GFP genes, creating interacting feedback loops that generate oscillatory behavior with periods tunable from 15 to 60 minutes by varying inducer concentrations [18].

Basic Structure of a Synthetic Genetic Circuit

Metabolic Pathway Engineering for Therapeutic Applications

Synthetic biology leverages modularity principles to engineer metabolic pathways for production of valuable compounds, including pharmaceutical agents. This application demonstrates how natural genetic modules can be reconfigured or completely redesigned to achieve industrial-scale production of therapeutic molecules.

The artemisinic acid pathway represents a landmark achievement in metabolic pathway engineering for drug development. Artemisinin is a potent antimalarial compound naturally produced by the plant Artemisia annua, but its structural complexity makes chemical synthesis challenging and expensive [18]. Synthetic biologists addressed this limitation by engineering a complete biosynthetic pathway for artemisinic acid (a direct precursor of artemisinin) in microbial hosts including E. coli and S. cerevisiae [18].

The engineering process involved multiple modular components:

- Amorphadiene synthase module: Introduction of the amorphadiene synthase gene from A. annua into microbial hosts to convert farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) to amorphadiene.

- Oxidation module: Engineering of cytochrome P450 enzymes to oxidize amorphadiene to artemisinic acid through multiple intermediate steps.

- Precursor enhancement module: Optimization of the host's native metabolic pathways to increase production of isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), the building blocks for FPP synthesis.

- Regulatory control module: Implementation of genetic controls to balance expression of pathway components and minimize metabolic burden.

This modular approach enabled separation of optimization efforts, with different teams focusing on specific pathway segments before integration into a complete production system. The resulting microbial production platform significantly reduced artemisinin production costs, making this essential antimalarial more accessible in developing regions [18].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Module Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Module Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, guide RNA | Targeted modification of module components |

| DNA Synthesis & Assembly | Gibson assembly, Golden Gate | Construction of synthetic modules |

| Regulatory Elements | Synthetic promoters, RBS | Control of module expression |

| Reporter Systems | GFP, luciferase | Monitoring module activity |

| Chassis Organisms | E. coli, S. cerevisiae | Host systems for module implementation |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance | Maintenance of synthetic constructs |

Advanced Analytical Frameworks

Synergistic Interactions in Modular Systems

Beyond simple modular organization, biological systems often exhibit synergistic interactions between modules that create emergent functionalities not present in individual components. Understanding and engineering these synergistic relationships represents the cutting edge of synthetic biology and module mining approaches [19].

Synergy in biological systems can be formally defined as the concerted action of multiple factors that produces an amplified or cancelation effect compared to the sum of their individual effects. Mathematically, synergy can be expressed using several frameworks:

- Superadditivity model: For a property x and observed activity f(x), synergistic effects occur when f(xâ‚ + xâ‚‚) ≥ f(xâ‚) + f(xâ‚‚), with synergy measured as Syn(xâ‚,xâ‚‚;f) = f(xâ‚ + xâ‚‚) - [f(xâ‚) + f(xâ‚‚)] [19].

- Supermodularity model: For set functions, two subsets Xâ‚ and Xâ‚‚ show synergistic effects when f(Xâ‚∪Xâ‚‚) + f(Xâ‚∩Xâ‚‚) ≥ f(Xâ‚) + f(Xâ‚‚) [19].

- Information-theoretic framework: Synergy between factors Xâ‚ and Xâ‚‚ with respect to activity f is defined as Syn(Xâ‚,Xâ‚‚;f) = I(Xâ‚,Xâ‚‚;f) - [I(Xâ‚;f) + I(Xâ‚‚;f)], where I represents mutual information [19].

In synthetic biology, synergistic effects can be harnessed to create functionalities that exceed the capabilities of individual modules. For instance, combining multiple genetic modules with weakly interacting components can produce strong emergent behaviors through constructive interference, similar to wave interference patterns in physical systems [19]. This approach contrasts with the traditional emphasis on orthogonality in synthetic biology, where cross-talk between modules is minimized. Instead, strategic integration of synergistic interactions can amplify desired behaviors and create novel system functionalities.

Engineering synergistic systems requires careful modeling and characterization of interactions between modules. Directed evolution approaches can optimize these interactions by selecting for combinations that produce desired emergent behaviors [19]. Additionally, computational models that account for non-linear interactions between module components can help predict synergistic effects before experimental implementation.

Multi-view Data Integration for Enhanced Module Discovery

Advanced module mining approaches increasingly leverage multi-view data integration to capture the complexity of biological systems from multiple perspectives. This framework recognizes that different data types provide complementary information about modular organization, and integrating these views can reveal more biologically meaningful patterns than analysis of single data types alone [20].

The CMNMF (Consistent Multi-view Nonnegative Matrix Factorization) framework exemplifies this approach by simultaneously analyzing gene-phenotype associations from multiple levels of phenotype ontology hierarchy [20]. This method:

- Factorizes gene-phenotype association matrices at consecutive levels of the hierarchical structure separately

- Constrains gene clusters derived from different hierarchy levels to be consistent

- Incorporates phenotype mapping constraints that enforce learned phenotype embeddings to respect hierarchical relationships

- Restricts identified gene clusters to be densely connected in the phenotype ontology hierarchy

This multi-view approach significantly improves clustering performance over single-view methods, as demonstrated in experiments mining functional gene modules from both mouse and human phenotype ontologies [20]. Validation against known KEGG pathways and protein-protein interaction networks confirmed that modules identified through multi-view integration have stronger biological significance than those identified through conventional single-view approaches.

The multi-view framework can be extended to incorporate additional data types beyond phenotype associations, including gene expression profiles, protein-protein interactions, epigenetic modifications, and metabolic network data. Each data type provides a different perspective on functional relationships between genes, and their integration can reveal consensus modules that represent fundamental functional units within biological systems.

The mining and characterization of genetic modules represents a cornerstone of modern synthetic biology and genomics research. Through computational approaches like multi-view nonnegative matrix factorization and experimental validation using co-association network analysis, researchers can identify functionally coherent genetic units that underlie complex biological processes. The principles of modularity—encapsulated functionality, limited pleiotropy, and standardized interfaces—provide a powerful framework for both understanding natural biological systems and engineering novel functionalities.

The applications of these principles in synthetic biology, from genetic circuit design to metabolic pathway engineering, demonstrate the practical utility of modular approaches for addressing real-world challenges in therapeutics and biotechnology. As the field advances, integration of synergistic interactions and multi-view data analysis will further enhance our ability to mine, characterize, and harness genetic modules for increasingly sophisticated biological engineering applications.

Moving forward, the integration of modularity principles with emerging technologies in genome synthesis and editing will continue to transform our approach to biological design, enabling more predictable and robust engineering of living systems for diverse applications across medicine, agriculture, and industrial biotechnology.

The pursuit of a minimal genome represents a fundamental endeavor in synthetic biology, aiming to define and construct the simplest set of genetic instructions capable of supporting independent cellular life. This concept is intrinsically linked to the core engineering principles of standardization and modularity that form the foundation of synthetic biology. By stripping cells down to their essential components, researchers seek to create optimized chassis organisms with reduced complexity that serve as predictable platforms for engineering novel biological functions [22] [23]. These minimal cells provide the foundational framework upon which synthetic biological systems can be built, mirroring the approach in electronics where standardized components are assembled into complex circuits.

The theoretical and practical implications of minimal genome research extend across multiple domains of biotechnology. A minimal chassis offers improved genetic stability by eliminating non-essential genes that can accumulate mutations or cause unwanted interactions. It provides increased transformation efficiency, allowing for more straightforward genetic manipulation, and enables more predictable behavior for industrial applications through the removal of redundant or regulatory complexity [23]. Furthermore, minimal cells serve as powerful experimental platforms for investigating the fundamental principles of life, allowing researchers to probe the core requirements for cellular existence without the confounding factors present in natural organisms [24].

Theoretical Foundation: Design Principles for Genome Minimization

Defining Essentiality: Conceptual Frameworks

The conceptual foundation of minimal genome research rests on precisely defining what constitutes an essential gene. In practical terms, essential genes are those strictly required for survival under ideal laboratory conditions with complete nutrient supplementation [24]. However, this definition presents several conceptual challenges that researchers must navigate. First, gene essentiality is context-dependent, varying based on environmental conditions, available nutrients, and genetic background. Second, there exists the phenomenon of synthetic lethality, where pairs of non-essential genes become essential when both are deleted. Third, the distinction between essential and useful genes is often blurred, as some genes significantly enhance fitness without being strictly necessary for viability [24].

From an engineering perspective, genome minimization applies the principle of functional abstraction through hierarchical organization. In this framework, basic biological parts are combined to form devices, which are integrated into systems within the minimal chassis [25]. This approach enables researchers to apply modular design principles, where discrete functional units can be characterized, optimized, and recombined with predictable outcomes. The minimal chassis itself represents the ultimate abstraction – a platform stripped of unnecessary complexity that maximizes predictability for engineering applications [2].

Computational and Experimental Approaches to Essential Gene Identification

Multiple complementary approaches have been developed to identify essential genes and define minimal gene sets. Comparative genomics analyzes evolutionary relationships to identify genes conserved across diverse lineages, suggesting core essential functions [24]. Systematic gene inactivation studies, including large-scale transposon mutagenesis and targeted gene knockouts, provide experimental evidence for gene essentiality by determining which disruptions are lethal [23] [24]. Metabolic modeling reconstructs biochemical networks to identify genes indispensable for maintaining core metabolic functions [24].

Table 1: Approaches for Identifying Essential Genes

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Advantage | Notable Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Genomics | Identification of genes conserved across multiple species | Leverages natural evolutionary data | May include genes not essential in laboratory conditions |

| Systematic Gene Inactivation | Experimental disruption of individual genes | Provides direct empirical evidence | Context-dependent results; misses synthetic lethals |

| Metabolic Modeling | Reconstruction of biochemical networks in silico | Systems-level perspective | Limited by knowledge gaps in metabolic pathways |

| Hybrid Bioinformatics | Integration of multiple data types and algorithms | Comprehensive coverage | Complex implementation requiring specialized expertise |

Each method provides partial insight, but integration of multiple approaches yields the most reliable minimal gene sets. The combination of computational prediction with experimental validation has proven particularly powerful in advancing the field toward functional minimal genomes [23] [24].

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Realization of Minimal Genomes

Top-Down Genome Reduction

The top-down approach to minimal genome construction begins with naturally occurring organisms and systematically removes genomic material to eliminate all non-essential genes. This method typically utilizes homologous recombination techniques to precisely delete targeted genomic regions in a sequential manner [24]. Model organisms with relatively small native genomes, particularly Mycoplasma species, have been favored starting points for these studies due to their reduced initial complexity.

Several notable achievements have demonstrated the feasibility of top-down genome reduction. Researchers have successfully generated streamlined versions of model bacteria including Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Mycoplasma mycoides through systematic deletion programs [24]. These reduced genomes frequently exhibit unanticipated beneficial properties for bioengineering applications, including high electroporation efficiency and improved genetic stability of recombinant genes and plasmids that were unstable in the parent strains [24]. These emergent properties make top-down minimized strains particularly valuable as chassis for synthetic biology applications.

The experimental workflow for top-down genome reduction involves multiple stages of design, construction, and characterization. The process begins with bioinformatic identification of potential deletion targets, followed by iterative cycles of genomic modification and phenotypic characterization. At each stage, viability, growth characteristics, and morphological properties are assessed to determine the success of the reduction step and guide subsequent modifications.

Figure 1: Top-Down Genome Reduction Workflow

Bottom-Up Genome Synthesis

In contrast to the reductive approach, bottom-up genome synthesis involves the de novo design and chemical construction of minimal genomes. This method applies principles of modular design and standardized assembly to build genomes from synthesized DNA fragments [26]. The bottom-up approach represents the ultimate engineering perspective on genome design, enabling complete control over genomic architecture and content.

The technical workflow for bottom-up synthesis has been dramatically accelerated through development of advanced tools and semi-automated processes. Modern methods enable researchers to progress rapidly from oligonucleotides to complete synthetic chromosomes, reducing assembly time from years to just weeks [26]. Key technological advances include improved DNA synthesis fidelity, advanced assembly techniques in yeast, and high-throughput validation methods to verify synthetic genome integrity.

The landmark achievement in bottom-up genome synthesis came from the J. Craig Venter Institute with the creation of JCVI-syn3.0, a minimal synthetic bacterial cell containing only 531,000 base pairs and 473 genes [26]. This organism was developed through an iterative design-build-test cycle using genes from the previously synthesized Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn1.0. The creation of JCVI-syn3.0 demonstrated that a self-replicating organism could be maintained with a genome significantly smaller than any found in nature.

Table 2: Comparison of Minimal Genome Organisms

| Organism/Strain | Genome Size | Number of Genes | Approach | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JCVI-syn3.0 | 531 kbp | 473 | Bottom-up synthesis | Smallest self-replicating organism; minimal genome factory [26] |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | 580 kbp | 482 | Natural minimal genome | Naturally occurring human pathogen with smallest known genome [24] |

| E. coli MDS42 | Reduced by ~15% | N/A | Top-down reduction | Improved genetic stability; useful for biotechnology [24] |

| B. subtilis MGB874 | Reduced by ~20% | N/A | Top-down reduction | High protein secretion capacity; model minimal factory [24] |

Case Study: JCVI-syn3.0 – A Landmark Minimal Genome

Design, Construction, and Unexpected Discoveries

The development of JCVI-syn3.0 represents a watershed moment in minimal genome research, showcasing the power of integrated design-build-test-learn cycles. The project began with the previously synthesized JCVI-syn1.0 genome, which served as the starting template for systematic minimization [26]. Researchers divided the genome into eight segments and methodically tested combinations of deletions to identify essential genomic regions. Through iterative cycles, they discovered that approximately 32% of the JCVI-syn1.0 genome could be eliminated while maintaining cellular viability under laboratory conditions.

Unexpectedly, the minimization process revealed that nearly a third of the genes retained in JCVI-syn3.0 (149 of 473 genes) had unknown or poorly characterized functions [26]. This striking finding highlights significant gaps in our fundamental understanding of cellular life, suggesting that essential biological processes remain to be discovered and characterized. These genes of unknown function are referred to as quasi-essential genes – while not strictly required for viability, their inclusion significantly enhances growth rates and overall fitness.

The experimental methodology employed in creating JCVI-syn3.0 exemplifies the synthetic biology approach to biological design. The process leveraged semi-automated genome engineering tools, yeast-based genome assembly, and genome transplantation techniques to construct and activate the minimal genome. The resulting organism, while capable of self-replication, exhibits a markedly different morphology compared to its parent strain, forming spherical shapes rather than the typical rod-like structures, indicating profound effects of genome minimization on cellular architecture and division.

Research Reagent Solutions for Minimal Genome Construction

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Minimal Genome Engineering

| Reagent/Technology | Function in Minimal Genome Research | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Assembly System | Recombination-based assembly of large DNA fragments in Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Bottom-up construction of complete synthetic genomes [26] |

| Genome Transplantation | Activation of synthetic genomes by transfer into recipient cells | Rebooting synthetic chromosomes in recipient cytoplasm [26] |

| Transposon Mutagenesis | Random insertion mutagenesis for essentiality mapping | High-throughput identification of essential genomic regions [24] |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Targeted genome editing for precise deletions | Top-down genome reduction through precise excision [24] |

| Homologous Recombination | Precise genetic modification using endogenous repair systems | Sequential genome streamlining in model organisms [24] |

Applications and Benefits: Minimal Cells as Optimized Chassis

Enhanced Properties for Biotechnology and Basic Research

Minimal genome strains exhibit several advantageous properties that make them particularly valuable as chassis for synthetic biology applications. Extensive studies have demonstrated that streamlined genomes often display superior genetic stability compared to their wild-type counterparts, likely due to the elimination of repetitive sequences and mobile genetic elements that promote recombination and genomic rearrangements [23] [24]. This stability is crucial for industrial biotechnology applications where consistent performance over many generations is required.

Additionally, minimal cells typically show increased transformation efficiency, making them more receptive to genetic modification. This property stems from the elimination of restriction-modification systems and other defense mechanisms that normally protect bacteria from foreign DNA uptake [24]. The combination of genetic stability and high transformability makes minimal cells ideal platforms for metabolic engineering and the production of valuable compounds.

Beyond applied biotechnology, minimal genomes serve as powerful tools for fundamental biological research. The JCVI-syn3.0 platform has enabled investigations into essential cellular processes including cell division, metabolism, and genome replication [26]. By providing a simplified background, minimal cells allow researchers to study biological systems with reduced complexity, making it easier to attribute functions to specific genetic elements and identify synthetic lethal interactions that are obscured in more complex organisms.

Metabolic Engineering and Therapeutic Applications

Minimal chassis organisms provide optimized platforms for metabolic engineering applications, where they serve as simplified factories for compound production. The removal of non-essential metabolic pathways reduces competition for precursors and energy, potentially directing more cellular resources toward the production of target compounds [22] [24]. This approach has been successfully applied in engineered E. coli and Bacillus strains for the production of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and specialty chemicals.

In therapeutic applications, minimal cells offer potential as targeted drug delivery systems with enhanced safety profiles. The reduced genomic content decreases the likelihood of horizontal gene transfer and eliminates many virulence factors present in natural strains [22]. Engineered minimal cells have been developed for applications including cancer therapy, where they can be designed to specifically target tumor cells while minimizing off-target effects on healthy tissues. The simplified regulatory networks in minimal cells also make their behavior more predictable when engineered with synthetic genetic circuits for therapeutic purposes.

Challenges and Future Directions: The Path Toward Optimized Minimal Genomes

Current Limitations and Research Challenges

Despite significant advances, several formidable challenges remain in the pursuit of optimally designed minimal genomes. The high percentage of genes with unknown functions in even the most minimized genomes represents a major knowledge gap that limits our ability to design genomes from first principles [26]. Until the essential functions of all retained genes are understood, truly rational genome design remains out of reach.

Another significant challenge lies in the context-dependent nature of gene essentiality. Genes that appear non-essential under ideal laboratory conditions with rich nutrient supplementation may become critical in more challenging environments [24]. This limitation restricts the utility of current minimal strains to controlled laboratory settings and highlights the need for condition-specific minimal genomes tailored to particular applications.

Technical hurdles also persist in the synthesis and assembly of large DNA molecules. While dramatic improvements have been made, the construction of error-free megabase-scale genomes remains challenging and resource-intensive [26]. Additionally, the booting up of synthetic genomes in recipient cells through genome transplantation is still an inefficient process with success rates that vary considerably between different genomic designs and recipient strains.

Emerging Approaches and Future Applications

Future advances in minimal genome research will likely be driven by integrated computational-experimental approaches. Whole-cell modeling that incorporates all cellular processes into unified simulation frameworks shows particular promise for predicting minimal genome designs in silico before physical construction [26]. These models, when sufficiently accurate, could dramatically accelerate the design-build-test cycle by prioritizing the most promising designs for experimental implementation.

The development of conditionally essential genomes represents another promising direction. Rather than seeking a universal minimal genome, researchers are designing strains with context-dependent essentiality, where different sets of genes are required in different environments or industrial applications. This approach acknowledges that optimal genome content varies based on intended function and growth conditions.

Figure 2: Minimal Genome Research Evolution

Looking further ahead, minimal genome technology may enable the creation of secure production platforms for sensitive applications in medicine and biotechnology. By eliminating transferable genetic elements and incorporating genetic safeguards, minimal cells could be designed with built-in biocontainment features that prevent environmental spread or unintended transfer of engineered traits. Such secure chassis would address important safety concerns while expanding the range of applications for engineered biological systems.

As synthetic biology continues to mature, the minimal genome concept will likely evolve from a research curiosity to an enabling technology that supports diverse applications across medicine, industry, and environmental management. The continued refinement of minimal chassis through iterative design cycles represents a crucial step toward predictable biological engineering, ultimately fulfilling the synthetic biology vision of making biology easier to engineer.

The advancement of synthetic biology is fundamentally linked to the principles of standardization and modularity, which aim to make biological engineering more predictable, reproducible, and scalable. A central question in this pursuit is the choice of platform for executing biological functions: traditional whole-cell systems or increasingly popular cell-free systems. Whole-cell systems utilize living microorganisms as hosts for bioproduction and biosensing, leveraging their self-replicating nature and complex metabolism. In contrast, cell-free systems consist of transcription and translation machinery extracted from cells, operating in an open in vitro environment devoid of membrane-bound barriers [27] [28]. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these platforms, examining their technical specifications, performance metrics, and suitability for different applications within the framework of synthetic biology standardization.

Core Principles and System Architectures

Fundamental Operational Differences

The architectural differences between whole-cell and cell-free systems create distinct operational paradigms. Whole-cell systems function as integrated, self-contained units where biological reactions occur within the structural and regulatory constraints of the cellular envelope. This enclosed architecture provides natural compartmentalization but imposes permeability barriers and places engineered functions in direct competition with host cellular processes [29] [28].

Cell-free systems reverse this paradigm by liberating biological machinery from cellular confinement. These systems typically contain RNA polymerase, ribosomes, translational apparatus, energy-generating molecules, and their cofactors, but operate without cell membranes [27] [30]. This open architecture provides direct access to the reaction environment, enabling real-time monitoring and manipulation that is impossible in whole-cell systems [28]. The fundamental distinction in system architectures underpins all subsequent differences in capability, performance, and application suitability.

System Preparation and Workflow Considerations