Debugging Compositional Context in Genetic Device Function: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Translation

The predictable engineering of genetic circuits is fundamentally challenged by compositional context-dependence, where a device's function is altered by its interconnected parts and host cellular environment.

Debugging Compositional Context in Genetic Device Function: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Translation

Abstract

The predictable engineering of genetic circuits is fundamentally challenged by compositional context-dependence, where a device's function is altered by its interconnected parts and host cellular environment. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, troubleshoot, and validate genetic devices. We explore the foundational sources of context, including resource competition and growth feedback, detail advanced methodological and combinatorial optimization approaches for mitigation, present systematic troubleshooting strategies for robust performance, and finally, outline rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks to ensure reliable translation from benchtop to clinical applications.

Understanding the Sources of Compositional Context in Synthetic Genetic Systems

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Unstable Circuit Output and Performance Drift

Problem: Your genetic circuit exhibits unpredictable output, performance degradation over time, or fails to maintain intended states in the host organism.

| Observed Symptom | Potential Contextual Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solutions & Mitigations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradual loss of circuit function or host viability over multiple generations | Global Growth Feedback: High circuit activity imposes metabolic burden, reducing host growth rate, which in turn alters circuit dynamics [1]. | • Measure correlation between circuit output (e.g., fluorescence) and host growth rate [1].• Use single-cell analysis to quantify cell-to-cell variability. | • Implement burden-balancing feedback control [1].• Use weaker promoters to reduce resource demand [1]. |

| Inconsistent output states in a bistable switch; failure to maintain "ON" or "OFF" state | Emergent Dynamics from Growth Feedback: Altered protein dilution rates due to burden can eliminate or create stable states [1]. | • Construct a rate-balance plot for the circuit to see how growth rate changes affect the number of steady states [1]. | • Re-engineer circuit topology to be more robust to dilution changes (e.g., self-activation switch) [1].• Engineer ultrasensitive response to counteract effects [1]. |

| Co-expression of multiple circuits leads to unexpected repression of all outputs | Resource Competition: Multiple modules compete for a finite pool of shared transcriptional/translational resources (e.g., RNA polymerase, ribosomes) [1]. | • Measure expression of individual modules in isolation vs. together.• Use RNA-seq to monitor global gene expression and resource levels. | • Resource-aware design: Decouple modules using orthogonal resources (e.g., T7 RNAP) [1] [2].• Design modules with matched resource demands to prevent winner-takes-all scenarios [1]. |

| Circuit performance varies significantly between different host strains or growth conditions | Host Context Dependence: Differences in host physiological state (e.g., resource pools, growth rate) directly impact circuit function [1]. | • Characterize circuit performance across a panel of host strains and in different media [1].• Quantify key host parameters like ribosome abundance. | • Host-aware design: Use mathematical models that incorporate host parameters [1].• Pre-adapt the host chassis to the circuit's resource demands. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Inter-Module Interference and Failed Integration

Problem: When individual genetic modules that function correctly in isolation are combined, the integrated system fails or behaves in unexpected ways.

| Observed Symptom | Potential Contextual Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solutions & Mitigations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adding a downstream module reduces the output of an upstream module | Retroactivity: The downstream module sequesters the output signal (e.g., a transcription factor) from the upstream module, acting as an unintended load [1]. | • Measure the input/output characteristics of the upstream module with and without the downstream module connected. | • Insert a "load driver" device (e.g., a high-gain amplifier) between modules to isolate them [1].• Design modules with low-output impedance. |

| Gene expression level is highly dependent on its position and orientation relative to other genes | Circuit Syntax & Supercoiling: Transcriptional activity is influenced by DNA supercoiling from neighboring genes, which varies with their relative orientation (convergent, divergent, tandem) [1]. | • Clone the same gene circuit in different syntactic arrangements (e.g., convergent vs. divergent).• Use inhibitors of DNA topoisomerases to probe supercoiling effects. | • Systematically test and select optimal gene syntax during design [1].• Incorporate insulators or chromatin barriers to decouple transcriptional units. |

| Poor performance of a complex, multi-gene circuit despite optimization of individual parts | Intragenetic Context: Hidden interactions between genetic parts (e.g., promoters, RBSs, coding sequences) affect overall device function [2]. | • Use characterized part libraries to ensure part compatibility.• Employ "parts swapping" to test different combinations. | • Level-Matching: Use computational tools to predict and balance the expression levels of all components [2].• Employ adapter parts (e.g., insulators, spacers) for fine-tuning without major redesign [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental categories of compositional context in synthetic biology? The functionality of a genetic device is influenced by three primary layers of context [1]:

- Intragenetic Context: Interactions between genetic parts within a single module or transcriptional unit.

- Intergenetic Context: Interactions between different genes or modules, including retroactivity and effects mediated by DNA supercoiling due to circuit syntax.

- Host-Level Context: The systemic interplay between the circuit and the host cell, primarily through growth feedback and global resource competition.

Q2: Why does my circuit work in E. coli but fail when transferred to a different bacterial species? This is a classic issue of host-specificity. Many biological parts, like promoters and ribosome binding sites (RBS), are coupled to the host's native gene expression machinery [2]. A part functional in E. coli may not be recognized correctly in another species. The solution is to use facultative or universal parts (e.g., T7 promoter with T7 RNAP, certain RNA aptamers) or to re-engineer the circuit using parts characterized for your specific target host [2].

Q3: We are seeing high cell-to-cell variability (noise) in our circuit output. Could this be related to compositional context? Yes. Contextual factors like resource competition can be a major source of noise [1]. Fluctuations in the shared pool of ribosomes or RNA polymerates can create correlated noise across multiple genes. Furthermore, growth feedback can amplify existing noise. Strategies to reduce noise include using orthogonal resources to decouple circuit expression from host fluctuations and implementing feedback control within the circuit to stabilize its output [1].

Q4: What is the difference between resource competition and retroactivity? While both cause interference between modules, they are distinct mechanisms [1]:

- Resource Competition is an indirect, global interaction. Module A consumes a shared, limited resource (e.g., ribosomes), making less of that resource available for Module B.

- Retroactivity is a direct, signal-specific interaction. Module B directly sequesters the output molecule of Module A (e.g., a transcription factor), preventing it from performing its intended function.

Q5: Are there modeling frameworks to help predict these contextual effects? Yes, "host-aware" and "resource-aware" modeling frameworks are being actively developed. These models move beyond idealized circuits and incorporate dynamic interactions between the circuit, host growth, and resource pools to better predict circuit behavior in vivo [1].

Experimental Protocols for Debugging Context

Protocol 1: Quantifying Growth Feedback and Metabolic Burden

Objective: To measure the coupling between circuit activity and host growth rate.

- Strain Preparation: Clone your genetic circuit into the desired host. Include an appropriate empty vector control and a host with no vector.

- Culture Conditions: Inoculate biological triplicates of each strain into a defined, rich medium and grow in a microplate reader or bioreactor with continuous OD600 monitoring.

- Circuit Activity Induction: Once cultures reach mid-exponential phase (e.g., OD600 ≈ 0.3-0.5), induce circuit expression using the appropriate molecule (e.g., IPTG, aTc).

- Parallel Monitoring: For the duration of the experiment, simultaneously track:

- OD600: As a proxy for host cell growth and biomass.

- Circuit Output: e.g., Fluorescence (GFP) for expression level or a enzymatic activity assay.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the growth rate (μ) from the slope of the ln(OD600) vs. time plot.

- Plot the growth rate against the maximum circuit output or the integrated output over time.

- A strong negative correlation indicates significant growth feedback and metabolic burden [1].

Protocol 2: Testing for Resource Competition Between Modules

Objective: To determine if two functional modules interfere with each other when co-expressed.

- Construct Creation:

- Strain A: Host with Module 1 only (e.g., a GFP reporter).

- Strain B: Host with Module 2 only (e.g., an RFP reporter).

- Strain C: Host with both Module 1 and Module 2 on a single plasmid or on separate, compatible plasmids.

- Calibration & Measurement: Grow all three strains under identical conditions. Use flow cytometry to measure the fluorescence output of each module (GFP and RFP) at the single-cell level.

- Analysis:

- Compare the mean fluorescence intensity of Module 1 in Strain A vs. Strain C.

- Compare the mean fluorescence intensity of Module 2 in Strain B vs. Strain C.

- If the expression of either module is significantly lower in the dual-expression strain (C) than in the single-expression strains (A or B), it indicates resource competition [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Research Reagent | Function & Utility in Debugging Context | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal RNA Polymerases (e.g., T7 RNAP) | Provides a dedicated transcriptional resource that is decoupled from the host's native RNAP, mitigating competition [2]. | Expressing multiple genes simultaneously without cross-talk by driving each with a different orthogonal system. |

| Fluorescent Protein Reporters (e.g., GFP, mCherry, BFP) | Serve as quantitative, real-time proxies for gene expression and circuit output. Essential for measuring burden and competition [2]. | Tagging different modules in a multi-gene circuit to visualize and quantify their individual expression dynamics. |

| Degradation Tags (e.g., ssrA) | Allows for targeted tuning of protein half-life, enabling control over circuit dynamics and dilution rates independent of growth [2]. | Shortening the response time of a circuit or reducing the load of a highly expressed protein. |

| Ribozymes & RNA Aptamers | Facultative parts that can regulate gene expression at the RNA level. Often function across different host species, enhancing portability [2]. | Creating tunable sensors or regulators that are less dependent on host-specific machinery. |

| Mathematical Modeling Software (e.g., MATLAB, COPASI) | Used to build "host-aware" models that simulate circuit behavior by incorporating growth and resource dynamics [1]. | Predicting how a circuit design will perform in vivo before construction, identifying potential failure points. |

| Regadenoson-d3 | Regadenoson-d3, MF:C15H18N8O5, MW:393.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-Erythrose-3-13C | D-Erythrose-3-13C, MF:C4H8O4, MW:121.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

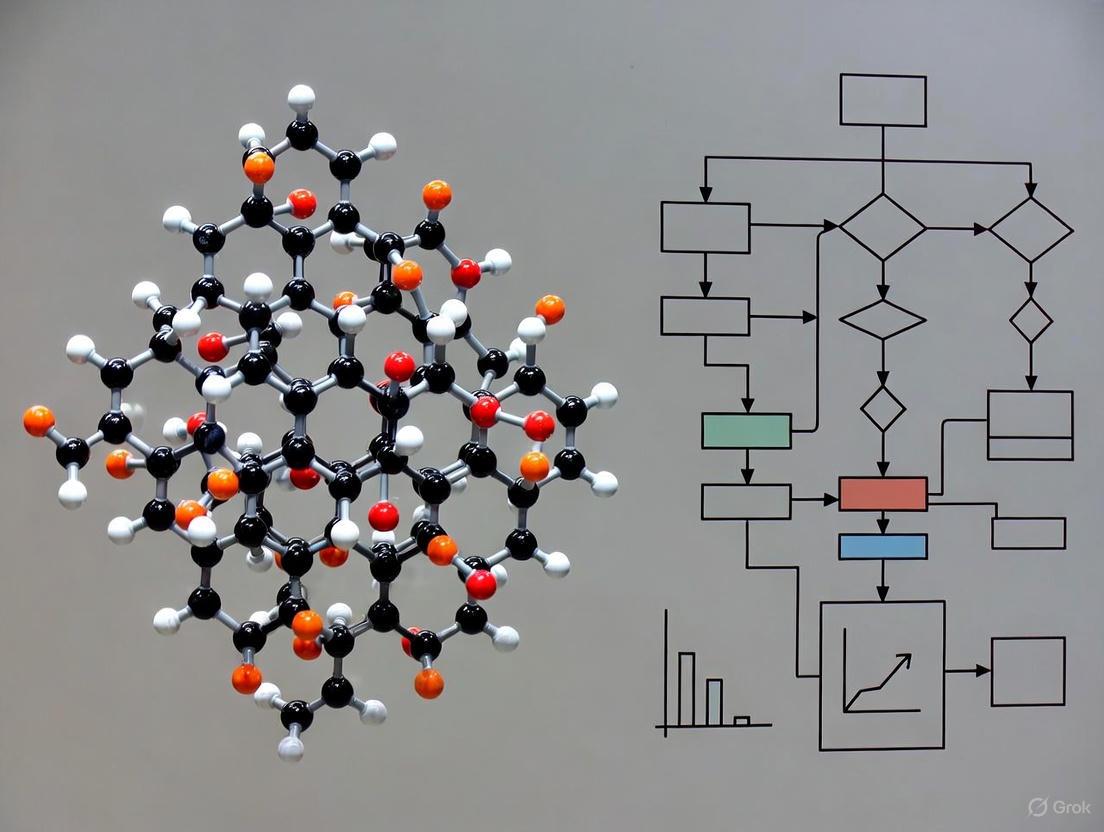

Diagram: Circuit-Host Interaction Framework

The following diagram illustrates the core feedback loops between a synthetic gene circuit, host resources, and cellular growth, which are central to understanding compositional context.

Diagram: Effects of Growth Feedback on Circuit Stability

This diagram visualizes how growth feedback can alter the fundamental stability of a genetic circuit, leading to the emergence or loss of steady states.

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers debugging issues related to compositional context in genetic device function, with a special focus on the interplay between growth feedback and resource competition.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary symptoms that my synthetic gene circuit is being affected by resource competition? The most common symptom is an unexpected, often biphasic, dose-response curve where the output of a gene module decreases as the input to a competing module increases, contrary to design expectations. You might also observe a "winner-takes-all" effect, where one module in a multi-gene circuit becomes dominant and suppresses the activity of others, instead of the expected co-activation [3].

Q2: My two-gene circuit shows cooperative behavior instead of the predicted competition. Is this possible? Yes. While resource competition alone typically leads to suppression, when coupled with growth feedback, it can induce cooperative behavior. This occurs because the expression of one gene (Gene A) can reduce the host cell's growth rate. This slower growth decreases the dilution rate for all cellular components, including the protein expressed by a second gene (Gene B), potentially increasing its steady-state concentration. This positive effect can, under certain conditions, outweigh the negative effects of direct resource competition [3].

Q3: What key parameters determine whether growth feedback leads to cooperation or competition? The switch between cooperative and competitive behavior is non-monotonically controlled by the metabolic burden threshold (J) and the resource capacity (Q). Cooperation is more likely when the metabolic burden thresholds (J1, J2) are low (high burden) and the resource capacities (Q1, Q2) are high (low competition). The specific parameter condition for cooperativity is complex, but fundamentally relies on the balance between these factors [3].

Q4: How can I experimentally test for growth feedback effects in my circuit? A key methodology is to measure the correlation between gene expression and host cell growth rate. The protocol below provides a detailed framework for this.

Troubleshooting Guide: Unexpected Gene Expression Dynamics

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Potential Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biphasic or decreasing dose-response | Resource competition from another active module [3] | Measure the output of other constitutive or inducible modules in the circuit while sweeping the input of the module in question. | Decouple expression by using orthogonal resources or implementing feedback control [3]. |

| Winner-takes-all outcome (one module dominates) | Strong resource competition between modules [3] | Verify that individual modules function correctly in isolation but not when co-expressed. | Incorporate growth feedback by design or use resource allocation controllers to buffer competition [3]. |

| One module activates another | Cooperative behavior mediated by growth feedback [3] | Measure the cell growth rate (e.g., via OD600) concurrently with gene expression. If growth rate decreases as the "activating" module is induced, growth feedback is likely involved. | Model the system with combined resource competition and growth feedback to predict and harness this behavior. |

| Loss of circuit memory in a bistable switch | Growth-mediated dilution affecting state stability [3] | Compare the stability of the switch in fast- and slow-growth conditions (e.g., different media). | Choose a network topology or parameters that are robust to growth-mediated dilution [3]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Growth Feedback Effects

Objective: To determine the impact of synthetic gene circuit expression on host cell growth and subsequent feedback.

Materials:

- Strain with your gene circuit of interest (e.g., an inducible system).

- Appropriate culture medium and inducer molecules.

- Microplate reader or spectrophotometer for measuring optical density (OD).

- Flow cytometer or fluorescence plate reader for measuring gene expression (e.g., GFP).

Method:

- Inoculation: Inoculate cultures with the engineered strain and appropriate control strains (e.g., empty vector).

- Induction: Apply a range of inducer concentrations to create a gradient of gene expression.

- Monitoring: Grow cultures in a microplate reader, periodically measuring:

- OD600: To track population growth.

- Fluorescence: To track circuit output.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the specific growth rate (µ) for each condition during exponential phase.

- Plot the steady-state gene expression and growth rate against the inducer concentration.

- A clear negative correlation between expression and growth rate confirms a significant growth feedback loop.

Protocol 2: Mapping Resource Competition Between Modules

Objective: To characterize the competitive coupling between two gene modules.

Materials:

- Strains with Module A alone, Module B alone, and both modules together.

- If applicable, specific inducers for each module.

Method:

- Baseline Characterization: For each single-module strain, measure the input-output relationship (transfer function) of the module.

- Co-expression Challenge: In the dual-module strain, systematically vary the input to Module A and measure the output of both Module A and Module B.

- Data Analysis: Compare the transfer function of each module in the dual-module context to its function in isolation. A significant suppression of one module's output when the other is active is a hallmark of resource competition.

The following table summarizes key quantitative relationships from the modeling framework that integrates both resource competition and growth feedback [3].

| Parameter / Metric | Symbol | Role in System | Typical Condition for Cooperativity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Capacity | ( Q_i ) | Maximum available resources for gene-i; lower ( Q ) means stronger competition. | High ( Q ) (low competition load) favors cooperation. |

| Metabolic Burden Threshold | ( J_i ) | Level of gene expression that significantly burdens growth; lower ( J ) means higher burden. | Low ( J ) (high burden) favors cooperation. |

| Maximum Growth Rate | ( k_{g0} ) | Host cell growth rate without metabolic burden. | Context-dependent; interacts with degradation rate. |

| Protein Degradation Rate | ( d_i ) | Rate constant for non-dilution degradation of the gene product. | A higher dilution fraction ( \left( \frac{k{g0}}{k{g0} + d_i} \right) ) favors cooperation. |

| Maximum Production Rate | ( v_i ) | Maximum synthesis rate of the gene product. | --- |

| Promoter Activity | ( R_i ) | Concentration of active promoters for gene-i. | --- |

Visualizing System Dynamics and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows. The color palette (#4285F4, #EA4335, #FBBC05, #34A853, #FFFFFF, #F1F3F4, #202124, #5F6368) ensures accessibility and visual clarity.

Diagram 1: Host-Circuit Interaction Logic

Diagram 2: Competition vs. Cooperation Outcomes

Diagram 3: Experimental Diagnostic Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Tunable Expression Vectors | Plasmids with inducible promoters (e.g., aTc, IPTG) allow controlled variation of gene expression to map input-output relationships and burden. |

| Fluorescent Reporters (e.g., GFP, mCherry) | Essential for quantifying gene expression dynamics and circuit output in real-time using flow cytometry or plate readers. |

| Orthogonal RNAPs / Ribosomes | Engineered transcription and translation systems that do not cross-talk with host machinery can mitigate resource competition [3]. |

| Mathematical Modeling Software | Tools like MATLAB or Python are crucial for simulating the combined ODE models of resource competition and growth feedback to predict behavior. |

| Microplate Reader | Instrumentation for high-throughput, parallel measurement of optical density (growth) and fluorescence (expression) over time. |

| Lrrk2-IN-3 | Lrrk2-IN-3, MF:C25H29ClF2N6O2, MW:519.0 g/mol |

| Btk-IN-10 | Btk-IN-10|Potent BTK Inhibitor|For Research Use |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Understanding Core Concepts

Q1: What is retroactivity in synthetic gene circuits? Retroactivity is a phenomenon where downstream nodes in a genetic network adversely affect or interfere with upstream nodes in an unintended manner. This interference occurs when downstream nodes sequester or modify the signals used by upstream nodes, leading to unexpected changes in network dynamics or behavior. For example, a module downstream from a reporter module can reduce the reported circuit output by sequestering the input signal to the reporter module [1].

Q2: How does circuit syntax affect gene expression? Circuit syntax involves the relative order and orientation of genes in a construct. The three basic syntaxes between two operons are convergent, divergent, and tandem orientations. Transcriptional interference in divergent and tandem-oriented genes is primarily mediated by DNA supercoiling, which can cause regions of DNA to become under/over-wound, significantly impacting transcription initiation and elongation [1].

Q3: What are the main sources of context-dependent failure in genetic circuits? The primary sources include:

- Retroactivity: Downstream modules sequestering upstream signals [1]

- Resource competition: Multiple modules competing for finite pools of shared cellular resources like RNA polymerase and ribosomes [1]

- Growth feedback: Reciprocal interactions where circuit burden reduces host growth rate, which in turn alters circuit behavior [1]

- Circuit syntax effects: Supercoiling-mediated feedback between adjacent genes [1]

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnecting Common Failures

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected reduction in circuit output | Retroactivity from downstream module sequestering signals [1] | Measure upstream module output in isolation vs. full circuit [1] | Implement "load driver" devices; Increase insulator parts [1] |

| Altered dynamic behavior (e.g., bistability loss) | Growth feedback diluting circuit components [1] | Measure correlation between growth rate and circuit output dilution [1] | Use burden-balancing elements; Modify promoter strengths [1] |

| Inter-module interference in multi-gene circuits | Resource competition for transcriptional/translational machinery [1] | Measure free RNAP/ribosome pools; Use resource sensors [1] | Implement orthogonal resources; Balance expression demands [1] |

| Variable performance based on gene order/orientation | Circuit syntax and supercoiling effects [1] | Test different gene orientations (convergent, divergent, tandem) [1] | Optimize gene order; Incorporate topological insulators [1] |

| Reduced cellular growth and fitness | Metabolic burden from heterologous gene expression [1] [4] | Monitor growth curves with/without circuit expression [1] | Use inducible systems; Distribute burden temporally [4] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Quantifying Retroactivity

Purpose: Measure how downstream systems affect upstream module performance.

Materials:

- Strains with upstream module only (control)

- Strains with complete circuit (upstream + downstream modules)

- Appropriate reporter genes (e.g., fluorescent proteins)

- Microplate reader or flow cytometer

Procedure:

- Transform constructs into appropriate host cells

- Culture cells under inducing conditions in biological replicates

- Measure upstream module output (e.g., fluorescence) at regular intervals

- Compare output levels between control and complete circuit strains

- Calculate retroactivity coefficient: ( R = 1 - \frac{Output{full}}{Output{control}} )

Interpretation: High R values (>0.3) indicate significant retroactivity requiring mitigation strategies.

Protocol 2: Testing Circuit Syntax Effects

Purpose: Evaluate how gene orientation affects circuit performance.

Materials:

- Constructs with identical genetic parts in different orientations (convergent, divergent, tandem)

- Supercoiling-sensitive reporter systems

- Gyrase inhibitors (e.g., novobiocin) for control experiments

Procedure:

- Design and build syntax variants maintaining identical coding sequences

- Transform into host cells and culture under standard conditions

- Measure expression outputs from all operons simultaneously

- Assess growth rates and circuit stability over multiple generations

- Test sensitivity to supercoiling-modifying drugs

Expected Outcomes: Divergent orientations often show mutual inhibition due to positive supercoiling accumulation [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Regulators | Control timing of gene expression without cross-talk [4] | Reduce resource competition; Implement logic gates [4] |

| "Load Driver" Devices | Mitigate undesirable impact of retroactivity [1] | Buffer upstream modules from downstream loads [1] |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Systems | Designable transcription factors with guide RNA targeting [5] | Create large orthogonal regulator sets; Minimal retroactivity [5] |

| Quorum Sensing Systems | Cell density-based control of expression [4] | Auto-inducible systems that reduce metabolic burden [4] |

| Small RNA Regulators | Post-transcriptional control via RNA-RNA/DNA interactions [4] | Fine-tune expression without transcriptional burden [4] |

| Biosensors | Transduce chemical production into detectable signals [4] | High-throughput screening of optimal pathway variants [4] |

| Combinatorial Libraries | Test multiple genetic variants simultaneously [4] | Optimize expression levels without prior knowledge [4] |

| Neratinib-d6 | Neratinib-d6, MF:C30H29ClN6O3, MW:563.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KRAS G12D inhibitor 15 | KRAS G12D inhibitor 15, MF:C53H71F2N7O5, MW:924.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Table 1: Context-Dependent Effects on Circuit Performance

| Interaction Type | Impact Metric | Typical Range | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retroactivity | Output reduction | 20-80% [1] | Upstream module isolation |

| Resource Competition | Expression correlation | r = -0.4 to -0.8 [1] | Dual-reporter systems |

| Growth Feedback | Growth rate reduction | 10-60% [1] | Growth curve analysis |

| Syntax Effects | Expression variation | 2-10 fold [1] | Orientation comparison |

Table 2: Mitigation Strategy Effectiveness

| Strategy | Complexity | Effectiveness | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Load Drivers | Medium | High for retroactivity [1] | Sensory systems; Multi-stage circuits |

| Orthogonal Regulators | High | Medium-High [5] [4] | Complex multi-gene circuits |

| Combinatorial Optimization | High | High for metabolic pathways [4] | Pathway balancing; Enzyme expression tuning |

| Inducible Systems | Low-Medium | Medium [4] | Reducing metabolic burden |

Signaling Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Retroactivity in Genetic Circuits

Circuit Syntax Orientation Effects

Diagnostic Decision Framework

Key Debugging Principles

Effective debugging of compositional context requires systematic investigation of the interactions between synthetic constructs and their host environment. The most successful approaches combine quantitative measurement of circuit performance with strategic implementation of decoupling elements that minimize unintended interactions. Progress in synthetic biology increasingly depends on recognizing that genetic circuits do not operate in isolation but rather function within the complex, resource-limited environment of living cells where retroactivity, resource competition, and host-circuit interactions fundamentally influence operational outcomes [1] [4].

FAQs on Context-Driven Circuit Failure

What is "context-driven circuit failure" in synthetic biology? Context-driven circuit failure occurs when a genetic circuit that functions as designed in isolation behaves unexpectedly or fails after being integrated into a host cell. This is due to complex and often unpredictable interactions between the synthetic construct, the host's native physiology, and the external environment [6] [7].

What are the most common sources of context-driven failure? Failures primarily arise from three overlapping contexts [7]:

- Construct Context: Intrinsic design of the circuit, such as part choice and relative gene orientation.

- Host Context: The cellular environment of the host organism, including resource competition and genome integration site effects.

- Environmental Context: External conditions like temperature, growth media, and cultivation processes.

Can a circuit be designed to be more robust against these failures? Yes. Systematic studies have identified that certain circuit topologies are inherently more resilient. For example, some circuit motifs maintain optimal performance despite growth feedback, while others fail. Using host-aware design principles and characterizing parts in the relevant context can improve robustness [6] [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Growth Feedback-Induced Circuit Dysfunction

- Problem Description: Circuit performance degrades or fails because the circuit's activity affects the host's growth rate, and the changing growth rate in turn alters circuit dynamics. This can manifest as a deformed response curve, unexpected oscillations, or a sudden switch in circuit output [6].

- Underlying Mechanism: Synthetic circuits consume cellular resources (e.g., nucleotides, RNA polymerase, ribosomes), imposing a metabolic burden that can slow cell growth. The reduced growth rate changes the effective concentrations of circuit components, creating a feedback loop that disturbs the circuit's intended function [6].

- Diagnosis Protocol:

- Measure Growth Curves: Correlate circuit performance (e.g., fluorescence output) with host cell density (OD600) over time in different experimental conditions.

- Vary Induction Levels: Test circuit function at different levels of induction. If higher induction (greater burden) leads to greater performance deviation, growth feedback is likely a factor.

- Utilize the Context Matrix: Systematically document the host strain, cultivation method, and media composition to identify which contextual factors are influencing the outcome [7].

- Solution Strategies:

- Topology Selection: Choose circuit architectures known to be robust to growth feedback. Computational screening of topologies can identify designs that maintain function despite growth coupling [6].

- Resource Burden Minimization: Use weaker promoters and RBSs to reduce the metabolic load imposed by the circuit [7].

- Decoupling Mechanisms: Employ orthogonal expression systems (e.g., T7 RNA polymerase) to insulate the circuit from host resource fluctuations [5].

Problem 2: Failure Due to Resource Competition and Part Interference

- Problem Description: A circuit performs well when characterized individually, but fails when other circuits are present in the same cell, or when parts within the circuit interfere with each other [7].

- Underlying Mechanism: Cellular resources like RNA polymerase and ribosomes are finite. Multiple synthetic constructs compete for these shared pools, leading to unexpected coupling and performance loss. Additionally, genetic parts from different sources may not be fully orthogonal and can cross-talk [5] [7].

- Diagnosis Protocol:

- Test for Orthogonality: Characterize all regulatory parts (promoters, TFs) in combination to identify unintended activation or repression.

- Copy Number and Location: Compare circuit function on high-copy plasmids versus low-copy or genome-integrated versions. Note that genome location can significantly affect expression due to regional transcriptional propensities [7].

- Characterize in Context: Always characterize and validate genetic parts within the final host strain and environmental conditions planned for the application [7].

- Solution Strategies:

- Use Orthogonal Parts: Implement engineered, highly orthogonal regulators, such as CRISPRi/dCas9 or tailored transcription factor libraries, to minimize cross-talk [5] [8].

- Host Engineering: Modify the host to provide more resources (e.g., engineer strains with extra copies of RNA polymerase genes) or to eliminate proteases that degrade circuit components.

- Construct Insulation: Incorporate insulators like strong terminators between transcription units to prevent read-through and interference [7].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Categories of Circuit Failure Induced by Growth Feedback

This table summarizes the failure modes identified from a systematic study of 435 adaptive circuit topologies under growth feedback [6].

| Failure Category | Key Characteristic | Impact on Circuit Function |

|---|---|---|

| Response Curve Deformation | The input-output response curve is continuously distorted. | Loss of sensitivity or precision; the circuit no longer responds to inputs as designed. |

| Induced Oscillations | The system develops strengthened or new oscillatory dynamics. | Unstable, non-steady output makes the circuit unreliable for applications requiring a stable state. |

| Bistable Switching | The system abruptly switches to a different, coexisting stable state. | The circuit "gets stuck" in an ON or OFF state and loses its ability to respond adaptively. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Context-Aware Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal TFs (e.g., TetR, LacI homologs) | Programmable DNA-binding proteins that regulate transcription without cross-talk [5] [8]. | Building larger, more complex circuits with minimal interference between components. |

| CRISPR-dCas Systems | Engineered Cas9 without nuclease activity; can be used as a programmable transcription activator or repressor (CRISPRa/i) [5] [8]. | Provides a highly designable and scalable platform for constructing orthogonal logic gates. |

| Site-Specific Recombinases (e.g., Serine Integrases) | Enzymes that catalyze irreversible DNA inversion or excision between specific target sites [5] [8]. | Creating long-term genetic memory circuits and complex logic in a single layer. |

| Context Matrix Framework | A conceptual framework to categorize experimental factors (Construct, Host, Environment) that affect circuit performance [7]. | Aiding systematic experimental design and troubleshooting by ensuring all relevant contexts are considered. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Growth Feedback Effects

Objective: To measure the impact of growth feedback on a specific genetic circuit's function.

Methodology:

- Circuit Design: Clone the genetic circuit into a suitable expression vector.

- Host Transformation: Transform the circuit into the target host strain.

- Cultivation: Inoculate cultures in biological triplicate and grow them under controlled conditions (e.g., in a microplate reader).

- Induction: At a defined cell density, induce the circuit with a range of input signal concentrations.

- Parallel Monitoring: Continuously monitor both the circuit's output (e.g., fluorescence) and the host's growth (OD600) throughout the experiment.

- Data Analysis: For each induction level, plot the circuit output against the growth rate. A significant correlation indicates strong growth feedback. Compare the input-output response curves obtained in vivo with predictions from context-free models [6].

Protocol 2: Testing for Resource Competition

Objective: To determine if circuit failure is due to competition for shared cellular resources.

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Characterize the performance of a reporter circuit (e.g., a GFP expression cassette) in isolation.

- Burden Application: Introduce a second, "burden" circuit (e.g., a strong, constitutive expression cassette for an inert protein) into the same host cell.

- Comparative Analysis: Measure the performance (e.g., expression level, dynamics) of the original reporter circuit in the presence and absence of the burden circuit.

- Orthogonal Validation: Repeat the experiment using an orthogonal system (e.g., T7 expression system) for the reporter to see if its function is decoupled from the burden [7]. A significant performance drop only with the shared host system confirms resource competition.

Mandatory Visualization

Technical Support Center

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Genetic Device Function Research. This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you debug issues related to compositional context in your genetic circuits.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Unbalanced Component Expression

Problem: My genetic circuit is not generating the proper input-output response. The output dynamics are incorrect.

Diagnosis: This is often caused by the imprecise balancing of component regulators, such as transcription factors, within your circuit [5]. The relative expression levels of these parts are critical for proper function.

Solution:

- Systematic Approach: Use available part libraries and computational tools to systematically tune the expression levels of each regulator [5]. Modern libraries offer more fine-grained control than was previously available.

- Method: Employ "tuning knobs" such as promoter strength libraries and Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) variants to adjust the translation initiation rate. The table below summarizes key tuning parameters.

Table 1: Expression Tuning Parameters for Circuit Balancing

| Tuning Parameter | Description | Common Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter Strength | Alters the rate of transcription initiation. | Libraries of constitutive promoters with varying strengths (e.g., J23xxx, J33xxx series). |

| RBS Strength | Alters the rate of translation initiation. | Computational prediction tools (e.g., RBS Calculator); degenerate RBS libraries. |

| Plasmid Copy Number | Changes the gene dosage. | Use of origins of replication with different copy numbers (e.g., high-copy pUC, low-copy pSC101). |

| Protein Degradation Tags | Adjusts the half-life of the regulator. | Addition of ssrA or other degradation tags to the protein coding sequence. |

Guide 2: Mitigating Failure Modes in Large Circuit Assembly

Problem: My large, multi-part genetic circuit does not function after assembly, or shows highly variable performance.

Diagnosis: The assembly of many DNA parts is technically challenging and can introduce errors. Furthermore, synthetic circuits are often highly sensitive to genetic context in ways that are poorly understood, where the function of one part is influenced by its neighboring sequences [5].

Solution:

- Standardized Assembly: Use modern, robust DNA assembly methods (e.g., Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly) to reduce technical errors [5].

- Insulation: Incorporate genetic insulators between device modules. These can include:

- Transcriptional Terminators: To prevent RNA polymerase read-through.

- RNase Cleavage Sites: To decouple translational units.

- Origin of Replication (ori) Insulators: To minimize transcriptional interference from the plasmid backbone.

- Screening: Design clear screens for circuit function. For digital logic (ON/OFF states), this is more straightforward. For dynamic circuits, this may require time-series measurements with fluorescent reporters [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of context dependence in genetic circuits? A: Context dependence arises from several factors, including the imprecise balancing of regulators, the genetic environment of a part (e.g., upstream and downstream sequences), and the host cell's resource availability (e.g., RNA polymerase, ribosomes) [5]. The interaction between these factors and your synthetic device is often poorly predicted.

Q2: My circuit works in one strain but fails in another. Why? A: Different host strains can have varying levels of endogenous resources like RNA polymerase, nucleases, and transcription factors. Your circuit may be drawing upon a resource that is limited in the new host. Consider characterizing your circuit in a range of strains or using "helper" strains engineered to supply necessary resources.

Q3: How can I better predict how my genetic circuit will behave before I build it? A: While comprehensive predictive tools are still under development, you can:

- Use available computational models that simulate transcriptional and translational processes.

- Build and characterize smaller sub-modules first to gather data on part performance in your specific context.

- Consult the failure mode libraries that are being collated by the synthetic biology community to learn from common design flaws [5].

Q4: What is the difference between a theoretical framework and a conceptual framework in this research context? A: In research, a theoretical framework provides the broader lens or existing theory that shapes your understanding (e.g., applying a specific model from control theory to understand circuit dynamics). A conceptual framework, however, is more specific; it outlines the exact variables and concepts in your study and proposes the potential relationships between them (e.g., a diagram showing how your specific promoter, RBS, and gene of interest interact) [9]. The theoretical framework guides your overall approach, while the conceptual framework operationalizes your specific experiment.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Characterizing a Promoter's Input-Output Function

This protocol describes how to generate a transfer curve for a genetic promoter, a key experiment for quantifying context dependence and predicting device function.

- Cloning: Clone the promoter of interest upstream of a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., GFP) in your desired plasmid backbone and host strain.

- Strain Preparation: For inducible promoters, transform the plasmid into your expression host. For constitutive promoters, you may proceed directly.

- Culturing:

- Inoculate 5 mL of appropriate media with a single colony and grow overnight.

- The next day, dilute the overnight culture to a standard OD₆₀₀ (e.g., 0.05) in fresh media.

- For inducible systems, aliquot the diluted culture into separate flasks and induce with a range of inducer concentrations (e.g., 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 5 mM IPTG). Include an uninduced control.

- Measurement:

- Grow the cultures to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ~ 0.4-0.6).

- Measure the OD₆₀₀ and fluorescence (e.g., Ex: 485 nm, Em: 520 nm for GFP) for each culture using a plate reader or spectrophotometer.

- Data Analysis:

- Normalize the fluorescence of each sample to its OD₆₀₀ to calculate Arbitrary Fluorescence Units (AFU).

- Plot the normalized fluorescence (output) against the inducer concentration (input) to generate the transfer curve.

- Fit the data to a suitable model (e.g., a Hill function) to extract parameters like leakiness, dynamic range, and switching threshold.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Genetic Circuit Design and Debugging Workflow

Diagram 1: Circuit Debugging Workflow

This diagram visualizes the core workflow for designing, building, and debugging a genetic circuit, with a feedback loop for addressing context dependence when experimental results do not match predictions based on the initial conceptual framework [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Circuit Construction and Analysis

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Orthogonal Repressors (e.g., TetR, LacI, CI) | DNA-binding proteins that allow the construction of logic gates (NOT, NOR) and dynamic circuits without cross-talk [5]. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 System | A designable regulator for knockdown (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) of gene expression; enables the construction of large circuits due to the ease of designing guide RNAs [5]. |

| Serine Integrases (e.g., Bxb1, PhiC31) | Unidirectional recombinases used to build permanent memory circuits and logic gates that record exposure to input signals [5]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins (e.g., GFP, mCherry) | Essential tools for measuring circuit output and dynamics in real-time, serving as proxies for gene expression levels [5]. |

| Expression Tuning Toolkits | Libraries of well-characterized biological parts (promoters, RBSs) used to balance the expression levels of circuit components precisely [5]. |

| Standardized Assembly Vectors | Plasmid backbones designed for specific assembly methods (e.g., MoClo, Golden Gate) that facilitate rapid and error-free construction of multi-part devices [5]. |

| Zaltoprofen-13C,d3 | Zaltoprofen-13C,d3, MF:C17H14O3S, MW:302.4 g/mol |

| (R)-Methotrexate-d3 | (R)-Methotrexate-d3|Deuterated Internal Standard |

Advanced Methodologies for Context-Aware Design and Combinatorial Optimization

Host-Aware and Resource-Aware Computational Modeling Frameworks

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common failure modes for genetic circuits, and how can I detect them? Unexpected circuit failures are common and can arise from several mechanisms. Key failure modes include cryptic antisense promoters, terminator failure, and sensor malfunction due to media-induced changes in host gene expression. These can be identified using RNA-seq methods, which provide a comprehensive, system-wide view of circuit performance and host health, moving beyond the limitations of single-output fluorescent reporters [10].

Q2: My genetic circuit functions correctly in isolation but fails when integrated into the host. Why does this happen? This is a classic symptom of resource competition. Synthetic genes compete with native host genes for finite cellular resources, such as ribosomes and nucleotides. This competition can create "gene expression burden," which hinders cell growth and alters the dynamics of your circuit. This interdependence between circuit function and host growth rate must be accounted for in your models [11].

Q3: What modeling approaches can predict how my circuit will affect cell growth? Coarse-grained bacterial cell models are designed for this purpose. These models balance simplicity with an accurate representation of metabolic regulation. They group cellular processes into a few key classes (e.g., ribosomal, metabolic, and housekeeping genes) and incorporate key regulatory pathways like ppGpp signaling. This allows them to reliably capture empirical growth laws and predict how synthetic gene expression impacts growth [11].

Q4: How can I model host-pathway interactions for metabolic engineering projects? A novel strategy integrates kinetic models of your heterologous pathway with Genome-Scale Metabolic (GEM) models of the production host. This combination allows you to simulate the local nonlinear dynamics of your pathway enzymes and metabolites, informed by the global metabolic state predicted by the GEM. Using machine learning surrogates for the GEM can significantly boost the computational efficiency of these simulations [12].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Problems and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Circuit Failures and Resource Competition

| Problem | Symptoms | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptic Antisense Transcription | Unanticipated RNA transcripts interfering with circuit logic [10]. | RNA-seq transcription profiles [10]. | Use bidirectional terminators to disrupt antisense transcription [10]. |

| Terminator Failure | Read-through transcription causing unintended gene expression [10]. | RNA-seq analysis of transcript ends [10]. | Select and validate high-efficiency terminators in the final circuit context [10]. |

| Sensor Malfunction | Inconsistent sensor activity under different culture conditions [10]. | RNA-seq to measure sensor output and host gene expression [10]. | Characterize sensors in the final host and media; use media-inducible systems [10]. |

| Resource Overload & Burden | Reduced cell growth rate and altered circuit dynamics [11]. | Growth rate assays; RNA-seq to monitor host gene expression [10] [11]. | Implement feedback control to manage burden; use orthogonal machinery; lower expression levels [11]. |

Advanced Diagnostics: RNA-Seq for Circuit Characterization

RNA-seq overcomes the limitations of fluorescent reporters by enabling simultaneous measurement of internal gate states, part performance, and the impact on the host [10]. The workflow is as follows:

- Sample Preparation: For a logic circuit, grow cells to steady-state for all relevant combinations of inputs. Flash-freeze aliquots to preserve RNA integrity [10].

- Library Preparation (RNAtag-seq): Fragment the total RNA from each sample. Ligate DNA adaptors with unique barcodes to the 3'-end of RNAs to "tag" each sample. Pool all tagged samples, deplete ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and generate a cDNA library for sequencing [10].

- Data Processing:

- Mapping: Map raw sequencing reads to a reference sequence (host genome + synthetic circuit) using tools like BWA [10].

- Profile Generation: Use tools like SAMtools to generate strand-specific transcription profiles, which show the number of transcripts at every DNA position [10].

- Correction: Apply a model to correct for localized drops in sequencing depth at transcript ends [10].

- Quantification: Use annotation files with HTSeq to count reads mapping to each gene for expression estimates [10].

RNA-seq Circuit Debugging Workflow

Modeling Host-Circuit Interactions

To proactively avoid issues, use a coarse-grained model that captures the essential interactions between your circuit and the host.

Host-Circuit Resource Competition

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Circuit Characterization via RNA-seq

This protocol allows for the in-depth debugging of a genetic circuit by analyzing its performance across all operational states [10].

- Circuit States: Identify all states requiring measurement. For a combinatorial logic circuit, this means cultivating samples for every combination of input signals [10].

- Cell Culture and Harvest: Grow cells containing the circuit under the defined conditions until they reach steady-state. Take aliquots and immediately flash-freeze them in liquid nitrogen to halt RNA degradation [10].

- RNA Extraction: Thaw samples and purify total RNA, concentrating it to the required levels for library preparation [10].

- RNAtag-Seq Library Preparation:

- Fragment the purified RNA.

- Ligate barcoded DNA adapters to the 3' ends of the RNA fragments from each sample.

- Combine all barcoded samples into a single pool.

- Deplete ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from the pooled sample.

- Perform reverse transcription to generate cDNA.

- Ligate 3' adapters and amplify the final library using indexed primers [10].

- Sequencing and Data Analysis: Sequence the library on an appropriate high-throughput platform. Use a customized pipeline to map reads to the host and circuit reference, generate corrected transcription profiles, and extract part activities [10].

Protocol 2: Integrating Kinetic Models with Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

This protocol is for predicting dynamic host-pathway interactions during fermentation [12].

- Model Definition: Define a kinetic model for your heterologous pathway of interest. Obtain a Genome-Scale Metabolic (GEM) model for your production host (e.g., E. coli) [12].

- Coupling: Develop a method to couple the two models. The kinetic model should simulate the local dynamics of pathway enzymes and metabolites. The GEM, solved via Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), should inform the kinetic model of the global metabolic state [12].

- Surrogate Model Training: To overcome the high computational cost of repeatedly running FBA, train machine learning surrogate models (e.g., neural networks) to approximate the FBA solutions for a given set of conditions [12].

- Simulation: Run dynamic simulations of the coupled system. The kinetic model uses the surrogate ML model to efficiently update the metabolic context, enabling the prediction of metabolite dynamics under genetic perturbations or different nutrient sources [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| RNAtag-Seq Reagents | Enables high-throughput, multiplexed RNA-seq by barcoding samples early in the workflow, allowing many conditions to be sequenced simultaneously [10]. |

| Bidirectional Terminators | Genetic parts placed between genes in opposite strands to prevent cryptic antisense transcription, a common failure mode in circuits [10]. |

| Coarse-Grained Cell Model | A computational model that groups cellular components into functional classes to predict how synthetic circuits impact host growth and resource allocation [11]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic (GEM) Model | A computational reconstruction of the entire metabolic network of an organism, used to predict metabolic fluxes under different conditions [12]. |

| Orthogonal Ribosomes | Engineered ribosomes that translate only synthetic mRNAs, reducing competition with host genes and mitigating resource burden [11]. |

| Machine Learning Surrogates | Models trained to approximate complex simulations (like FBA), drastically speeding up integrated dynamic simulations [12]. |

| 11-Beta-hydroxyandrostenedione-d7 | 11-Beta-hydroxyandrostenedione-d7, MF:C19H26O3, MW:309.4 g/mol |

| Cox-2-IN-22 | Cox-2-IN-22|Selective COX-2 Inhibitor|Research Compound |

Combinatorial Optimization Strategies for Multivariate Tuning

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Failures and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Genetic Circuit Optimization

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected circuit output or logic failure | Cryptic antisense promoters, terminator failure, sensor malfunction due to media-induced changes | RNA-seq to measure internal gate states and part performance | Use bidirectional terminators; characterize parts in final circuit context | [10] |

| Poor biosensor performance in heterologous host | Signal saturation at low intracellular metabolite concentrations | Flow cytometry for single-cell analysis; effector titration | Fine-tune regulator activity using different constitutive promoters | [13] |

| Difficulty identifying effective guide RNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 | More than one guide RNA can match a given gene target | High-throughput analysis of guide RNA-target activity | Use predictive software with experimental data to rank guide RNAs | [14] |

| Combinatorial genetic interactions causing unexpected phenotypes | Interactions between multiple synthetic chromosomes | CRISPR Directed Biallelic URA3-assisted Genome Scan (CRISPR D-BUGS) | Fine-map phenotypic variants to specific designer modifications | [15] |

| Suboptimal multivariate performance | Unknown relationship between input variables and response | Sequential Experimental Design (e.g., steepest ascent path) | Fit response surface models to navigate parameter space efficiently | [16] |

Diagnostic Methodologies

RNA-Seq for Circuit Characterization

Purpose: Simultaneously measure internal gate states, part performance, and host gene expression impact [10].

Protocol:

- Data Collection: Grow cells with genetic circuits to steady-state for all input combinations. Flash-freeze aliquots in liquid nitrogen to preserve RNA.

- Library Preparation:

- Fragment total RNA.

- Ligate DNA adaptors with unique barcode sequences to the 3'-end of RNAs (RNAtag-Seq).

- Pool tagged samples.

- Deplete ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

- Generate cDNA via reverse transcription.

- Ligate 3' DNA adaptors and amplify with indexed sequencing primers.

- Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequence using next-generation platforms.

- Map reads to reference sequences (host genome + synthetic circuit).

- Generate strand-specific transcription profiles.

- Use biophysical models to extract part activities and response functions.

RNA-Seq Circuit Characterization Workflow

CRISPR D-BUGS for Genetic Interaction Mapping

Purpose: Map phenotypic variants caused by specific designer modifications in synthetic chromosomes [15].

Protocol:

- Strain Construction: Consolidate multiple synthetic chromosomes using endoreduplication intercrossing.

- Phenotypic Screening: Identify unexpected phenotypes in consolidated strains.

- Fine-Mapping:

- Use CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce biallelic markers (e.g., URA3).

- Systematically scan genome to link phenotypes to specific genetic modifications.

- Identify combinatorial interactions between different synthetic elements.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the advantage of using a generalized combinatorial optimization approach for multiple genetic design problems?

A1: Traditional machine learning approaches often treat each combinatorial optimization problem in isolation, failing to capitalize on underlying relationships between problems. A generalized approach uses a shared encoder to learn solving strategies that capture shared structure among different problems, enabling easier adaptation to related tasks. This allows models trained on several problems to perform comparably on new problems to models trained from scratch [17].

Q2: How can I fine-tune biosensor parameters for optimal performance?

A2: A unified biosensor design allows fine-tuning by controlling the expression level of the regulator gene using different constitutive promoters selected for your specific expression host. This approach enables customization of important sensor parameters and can restore sensor response in heterologous hosts [13]. For systematic optimization, use Design of Experiments (DoE) algorithms to efficiently sample the vast combinatorial design space of biosensor permutations [18].

Q3: What are common failure modes when assembling genetic circuits?

A3: Common failures include:

- Cryptic antisense promoters causing unintended transcription

- Terminator failure leading to read-through transcription

- Sensor malfunction due to media-induced changes in host gene expression

- Genetic context effects where parts function differently in final circuit versus isolation

- Combinatorial genetic interactions between multiple synthetic elements [15] [10]

Q4: How can I efficiently navigate multivariate optimization problems with unknown response functions?

A4: Use a sequential Experimental Design strategy:

- Start with a small region of parameter space using fractional factorial designs (e.g., 2³ + center points)

- Fit a linear regression model and identify significant factors

- Follow the path of steepest ascent to move toward optimal regions

- Once curvature becomes significant, use Response Surface Methodology (e.g., Central Composite Design) to model the optimal region [16]

Q5: What computational tools are available for predicting effective guide RNAs?

A5: Specialized software programs are available that use algorithms based on experimental data from human genomes. These tools hierarchically rank guide RNA effectiveness based on sequence features identified through high-throughput analysis of guide RNA-target activity, eliminating trial-and-error selection processes [14].

Experimental Protocols

Design of Experiments for Multivariate Optimization

Purpose: Efficiently find optimal input parameter combinations when the response function is unknown [16].

Table 2: Experimental Design Strategy for Multivariate Optimization

| Stage | Design Type | Purpose | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Screening | 2³ factorial + center points | Identify significant factors and direction for improvement | Significant main effects; direction of steepest ascent |

| Path of Steepest Ascent | Sequential experiments along gradient | Rapidly move toward optimal region | New center point for detailed analysis |

| Response Surface Characterization | Central Composite Design (CCD) | Model curvature and locate optimum | Quadratic model for optimization |

Protocol:

- Variable Scaling: Scale all input variables to the same range (e.g., 0.0-5.0) to ensure comparable regression coefficients.

- Initial Experiment (2³ + CP):

- Select 12 (x1, x2, x3) combinations from the [0,1] scaled region

- Perform experiments and measure response values

- Fit linear regression model: y = β₀ + βâ‚xâ‚ + β₂xâ‚‚ + β₃x₃

- Steepest Ascent Path:

- Calculate step sizes proportional to regression coefficients: Stepâ‚ = 1, Stepâ‚‚ = β₂/βâ‚, Step₃ = β₃/βâ‚

- Conduct sequential experiments along this path

- Response Surface Methodology:

- Once curvature is detected, perform Central Composite Design

- Fit quadratic model: y = β₀ + Σβᵢxᵢ + Σβᵢᵢxᵢ² + Σβᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ

- Use contour plots to identify optimal settings

Multivariate Optimization Workflow

Biosensor Fine-Tuning Protocol

Purpose: Customize biosensor parameters for specific applications and hosts [13].

Protocol:

- Construct Promoter Libraries: Create libraries of constitutive promoters with varying strengths.

- Control Regulator Activity: Express the biosensor regulator gene using different selected promoters.

- Characterization:

- Analyze response using flow cytometry for single-cell resolution

- Perform effector titration analysis under monoclonal screening conditions

- Measure dose-response curves in liquid cultures

- Optimization:

- Use DoE algorithms for fractional sampling of design space

- Transform expression data into structured dimensionless inputs

- Computationally map full experimental design space

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Circuit Optimization

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RNAtag-Seq | Tags fragmented RNA with barcodes before rRNA depletion | Enables pooling of multiple samples for efficient RNA-seq; reduces cost and preparation time [10] |

| Bidirectional Terminators | Prevents cryptic antisense transcription | Fixes unexpected circuit failures caused by unintended antisense promoters [10] |

| Constitutive Promoter Libraries | Provides graded expression levels for fine-tuning | Balancing regulator activity in biosensors; tuning genetic circuit components [13] |

| dCas9 Variants | Catalytically inactive Cas9 for transcription regulation | CRISPRi and CRISPRa applications; knocking down or activating gene expression [5] |

| Orthogonal Serine Integrases | Unidirectional DNA inversion for memory circuits | Building logic gates with stable memory; counters and switches [5] |

| Predictive Guide RNA Software | Algorithms ranking guide RNA effectiveness | Selecting optimal guide RNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 applications without trial-and-error [14] |

| Design of Experiments Software | Statistical design and analysis of experiments | Efficiently sampling multivariate design spaces; response surface methodology [16] |

| GLS1 Inhibitor-6 | GLS1 Inhibitor-6 is a potent, selective, and orally active glutaminase-1 inhibitor. Explore its anti-tumor activity for your cancer research. For Research Use Only. | |

| Aurora kinase-IN-1 | Aurora kinase-IN-1|Aurora Kinase Inhibitor|For Research Use | Aurora kinase-IN-1 is a potent Aurora kinase inhibitor for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

Leveraging AI and Large Language Models for De Novo Protein and Circuit Design

FAQs: Core Concepts and Workflow

Q1: What is the fundamental shift that AI brings to protein design? AI has transformed protein design from a process reliant on modifying natural templates to a generative discipline where novel, functional proteins can be designed from first principles. This AI-driven de novo design overcomes the constraints of natural evolutionary pathways, allowing researchers to access a vastly larger "protein functional universe" and create bespoke biomolecules with customized folds and functions [19] [20].

Q2: How are Large Language Models (LLMs) like ProGen applied to protein design? Amino acid sequences are treated as sentences in a specialized language. LLMs, such as ProGen, are trained on millions of protein sequences to learn the statistical patterns and "grammar" that dictate protein structure and function. Once trained, these models can generate novel, functional protein sequences from scratch, conditioned on desired properties like protein family or function [21] [22].

Q3: What are the key advantages of using a language model approach over traditional physics-based models? Language models like ProGen can generate functional proteins without explicit biophysical modeling or reliance on scarce experimental structure data. They learn evolutionary conservation patterns directly from sequences, without needing multiple sequence alignments. This allows them to rapidly explore a broader sequence space and generate proteins with low sequence identity (e.g., as low as 31.4%) to natural proteins while retaining function [22].

Q4: What is the "Protein-as-a-Second-Language" framework? This is a novel framework that allows general-purpose LLMs to understand and reason about protein sequences without requiring task-specific fine-tuning. It treats amino acid sequences as a symbolic system and uses in-context learning with protein-question-answer triples to enable the model to infer protein function, achieving performance that can surpass specialized protein language models [23].

Q5: What is a major challenge when integrating de novo designed proteins into cellular systems? A primary challenge is functional unpredictability within the complex compositional context of a cell. A protein that is stable and functional in silico or in vitro may cause unforeseen issues in vivo, such as triggering immune reactions, misfolding, or disrupting native cellular pathways and signaling networks due to unanticipated interactions [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Debugging

Issue 1: AI-Designed Protein is Unstable or MisfoldsIn Vivo

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate energy landscape prediction from physics-based force fields [25]. | Compare predicted structure from multiple tools (AlphaFold2, ESMFold). Check for core packing defects [25]. | Use a hybrid strategy: refine AI-generated sequences with force fields like FoldX or Rosetta for stability scoring [25]. |

| Lack of evolutionary constraints in generative model, leading to "non-native" features [20]. | Analyze sequence similarity to natural proteins (Max ID). Very low identity may indicate high risk [22]. | Fine-tune the generative model (e.g., ProGen) on a curated dataset of the target protein family to bias outputs toward naturalistic sequences [22]. |

| Missing cellular context like chaperones or specific redox conditions [26]. | Test expression in different cellular compartments or hosts. Use proteomics to check for aggregation [26]. | Co-express relevant molecular chaperones or switch to a cell-free expression system for initial functional validation [22]. |

Issue 2: Designed Genetic Circuit Exhibits Unpredicted Behavior

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Improper protein stoichiometry or assembly within the circuit [27]. | Use quantitative Western blot or fluorescence to measure component levels. | Utilize DNA origami scaffolds to control the precise number, distance, and orientation of protein components for predictable signaling [27]. |

| Off-target interactions between de novo proteins and host cellular machinery [24]. | Perform pull-down assays coupled with mass spectrometry to identify unintended interaction partners. | Re-design the protein surface to reduce hydrophobicity and negative design principles to enforce orthogonality to host biology [20] [24]. |

| Context-dependent resource depletion (e.g., ATP, ribosomes). | Use RNA-seq to monitor global cellular stress responses. | Implement dynamic regulatory elements in the circuit design to manage metabolic load and avoid resource competition [24]. |

Issue 3: Poor Functional Activity in Designed Enzyme

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect active site geometry despite overall correct fold [25]. | Solve the crystal structure of the designed protein to compare active site residues with the natural counterpart [22]. | Use inverse folding tools (ProteinMPNN, Esm_inverse) to redesign sequences for a fixed backbone that precisely positions catalytic residues [25]. |

| Generative model fine-tuned on insufficient or low-quality family data [25]. | Check the model's per-residue likelihood score; low scores may indicate poor generation quality [22]. | Expand the fine-tuning dataset with high-quality, curated sequences from the target family. Use adversarial discriminators to filter poor-quality generations [22]. |

| Sub-optimal substrate access or surface properties. | Perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to analyze substrate diffusion pathways. | Employ virtual screening (T6) and docking simulations to optimize the substrate binding pocket and access channels before experimental testing [28]. |

Table 1: Experimental Performance Metrics of ProGen, a Protein Language Model

| Metric | Lysozyme Families | Chorismate Mutase | Malate Dehydrogenase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Data Size | 280 million sequences (>19,000 families) [21] | - | - |

| Model Parameters | 1.2 billion [22] | - | - |

| Sequence Identity to Natural | As low as 31.4% [21] | Functional sequences predicted [22] | Functional sequences predicted [22] |

| Catalytic Efficiency | Similar to natural lysozymes (e.g., Hen Egg White Lysozyme) [21] | - | - |

| Experimental Success Rate | High (X-ray structure confirmed conserved fold) [22] | - | - |

Table 2: Comparison of Key AI Protein Design Tools and Their Applications

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Best For | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProGen | Conditional sequence generation [21] | Generating novel sequences for a target family [22] | May require fine-tuning for specific families [21] |

| ProteinMPNN | Inverse folding (sequence for backbone) [25] | Fixing a sequence to a given structure [28] | Fast, robust for natural-like backbones [25] |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure prediction from sequence [26] | Validating designed sequences in silico [28] | Prediction, not design tool [26] |

| RFDiffusion | De novo backbone generation [28] | Creating entirely new protein folds [28] | Requires sequence design as a subsequent step [28] |

| FoldX/Rosetta | Force field-based energy calculation [25] | Precise stability scoring for point mutations [25] | Computationally expensive; force fields are approximate [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fine-Tuning a Language Model for a Target Protein Family

This protocol is based on the methodology used to develop ProGen for lysozyme families [22].

- Data Curation: Collect a high-quality dataset of protein sequences from the family of interest (e.g., from Pfam, UniProtKB). For the lysozyme study, 55,948 sequences were used [22].

- Model Selection: Start with a pre-trained protein language model (e.g., ProGen).

- Fine-Tuning: Perform computationally inexpensive gradient updates to the model's parameters using the curated family-specific dataset. This adapts the model's general knowledge to the target family.

- Sequence Generation: Generate a large library of novel sequences (e.g., 1 million) by conditioning the model on the target family's Pfam ID.

- Quality Filtering: Rank the generated sequences using a combination of:

- Model Log-Likelihood: The model's own confidence in the sequence.

- Adversarial Discriminator: A separately trained model that distinguishes real from generated sequences to filter out poor-quality designs [22].

- Diversity Selection: Sample from the top-ranked sequences to ensure a range of sequence identities (e.g., 40-90% max identity to natural proteins) for experimental testing.

Protocol 2: Validating AI-Designed Proteins in a Cell-Free System

This protocol is ideal for initial, high-throughput functional screening while avoiding cellular complexity [22].

- DNA Synthesis & Cloning (T7): Translate the final protein designs into optimized DNA sequences and clone them into an appropriate expression vector [28].

- Cell-Free Expression: Express the proteins using a commercial or homemade cell-free protein synthesis system. This bypasses potential cellular toxicity and allows for rapid production.

- Purification: Purify the synthesized proteins using affinity tags (e.g., His-tag).

- Functional Assay: Perform an activity assay specific to the protein's function. For lysozymes, this involved measuring the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) by monitoring the hydrolysis of a bacterial cell wall substrate [22].

- Biophysical Characterization: Assess stability using techniques like circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy or chemical denaturation.

- Structural Validation (If possible): For top-performing designs, determine the high-resolution structure using X-ray crystallography to confirm the predicted fold and active site geometry [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for AI-Driven Protein Design and Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Application in Debugging |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained PLMs (ProGen, ProtGPT2) | Generate novel protein sequences based on evolutionary patterns [21] [22]. | Starting point for creating de novo protein components for genetic circuits. |

| Inverse Folding Tools (ProteinMPNN, Esm_inverse) | Design a protein sequence that will fold into a given 3D backbone structure [28] [25]. | Repacking protein cores or re-engineering interfaces to improve stability or alter function. |

| Structure Prediction (AlphaFold2, ESMFold) | Predict the 3D structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence [28] [26]. | Rapid in silico validation of a designed protein's fold before experimental testing. |

| Force Field Software (FoldX, Rosetta) | Calculate the stability energy of a protein structure or mutant [25]. | Diagnosing and ranking the stability of designed protein variants; most accurate for point mutations [25]. |

| DNA Origami Scaffolds | Programmable nanostructures for precise spatial organization of molecules [27]. | Debugging circuit function by controlling the precise number, distance, and orientation of protein components to isolate stoichiometry issues [27]. |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | In vitro transcription/translation systems for protein synthesis. | Rapidly testing protein expression and function without the complexity of a living cell, isolating cell-level issues [22]. |

| DNA-PK-IN-1 | DNA-PK-IN-1|Potent DNA-PK Inhibitor|RUO | DNA-PK-IN-1 is a potent, selective DNA-PKcs inhibitor. It blocks NHEJ DNA repair for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Xylose-4-13C | Xylose-4-13C, MF:C5H10O5, MW:151.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Diagram 1: AI-Driven Protein Design Workflow

This diagram illustrates the integrated seven-toolkit workflow for de novo protein design, from concept to validated candidate [28].

Diagram 2: Debugging Context in Genetic Circuit Function

This diagram maps the logical relationship between common failure modes in synthetic genetic circuits and the recommended diagnostic and solution pathways.

Orthogonal Regulator Systems and Parts Mining to Bypass Host Interference

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: My orthogonal sigma factor is expressing, but I'm not getting the expected output from its target promoter. What could be wrong?