CRISPRi for Fine-Tuning Metabolic Pathways: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a detailed exploration of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) as a powerful tool for the precise, multi-level regulation of metabolic pathways in both bacterial and eukaryotic systems.

CRISPRi for Fine-Tuning Metabolic Pathways: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) as a powerful tool for the precise, multi-level regulation of metabolic pathways in both bacterial and eukaryotic systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of dCas9-based transcriptional control, its practical application in metabolic engineering and consortium-based fermentations, and advanced strategies for troubleshooting guide RNA efficiency and minimizing off-target effects. Furthermore, it offers a critical comparison of validation methodologies—from T7E1 assays to next-generation sequencing—and synthesizes key takeaways to outline future directions for biomedical and clinical research, including the integration of AI and machine learning for predictive design.

Beyond Cutting: Understanding CRISPRi as a Versatile Tool for Metabolic Regulation

From Molecular Scissors to a Synthetic Biology Swiss Army Knife

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for CRISPRi in Metabolic Pathways Research

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the recommended sequencing depth for a CRISPRi screen, and how is it calculated? For reliable results, each sample in a CRISPRi screen should achieve a sequencing depth of at least 200x [1]. The required data volume can be estimated using the formula: Required Data Volume = Sequencing Depth × Library Coverage × Number of sgRNAs / Mapping Rate [1]. For a typical human whole-genome knockout library, this translates to approximately 10 Gb of sequencing per sample [1].

Q2: Why do different sgRNAs targeting the same gene show variable repression efficiency? Gene repression efficiency in CRISPRi is highly influenced by the intrinsic properties of each sgRNA sequence, including its specificity and the accessibility of its target DNA region [1] [2]. To ensure reliable and robust results, it is recommended to design and test at least 3–4 sgRNAs per gene. Using a pool of sgRNAs can help mitigate the impact of individual sgRNA performance variability and may even produce enhanced repression compared to the most effective single guide [1] [2].

Q3: If my CRISPRi screen shows no significant gene enrichment, what could be the problem? The absence of significant gene enrichment is more commonly a result of insufficient selection pressure during the screening process rather than a statistical error [1]. When selection pressure is too low, the experimental group may fail to exhibit a strong enough phenotype for detection. To address this, consider increasing the selection pressure and/or extending the screening duration to allow for greater enrichment of cells with the desired phenotype [1].

Q4: How can I fine-tune the dynamic range of CRISPRi repression? The high potency of CRISPRi can be a challenge for inducible systems. Three methods for enhancing controllability are [3]:

- Designed Mismatches: Introducing rationally designed mismatches in the reversibility determining region of the guide RNA sequence can attenuate overall repression.

- Decoy Target Sites: Using decoy target sites can selectively modulate repression at low levels of induction.

- Feedback Control: Implementing feedback control enhances the linearity of induction, broadens the dynamic range of the output, and improves the recovery rate after induction is removed.

Q5: What are the key considerations for designing effective CRISPRi guide RNAs? CRISPRi requires guide RNAs to be designed to target regions 0-300 base pairs downstream of the target gene's transcriptional start site (TSS) [2]. Effectiveness is maximized by using algorithms trained via machine learning that incorporate chromatin, position, and sequence data to predict highly effective guides, as TSSs are not always well-annotated and may be inaccessible due to other protein factors [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low or No Detectable Gene Repression

- Potential Cause 1: Inefficient sgRNA design or targeting an inaccessible genomic region.

- Potential Cause 2: Low efficiency of delivery or expression of the dCas9-repressor construct.

- Solution: Confirm repressor protein expression with Western blotting. Optimize transfection/nucleofection protocols for your cell type and consider using positive control sgRNAs targeting genes with well-established knockdown phenotypes [2].

- Potential Cause 3: Incorrect timing of repression assessment.

- Solution: Repression is typically maximal 48-72 hours post-transfection with synthetic sgRNAs [2]. Ensure you are measuring gene expression at the appropriate time point.

Problem: High Variability Between Replicates

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent library coverage or low cell numbers leading to stochastic sgRNA loss.

- Solution: Ensure adequate library coverage during cell pool generation. For FACS-based screens, increase the initial number of cells and perform multiple sorting rounds where feasible to reduce technical noise [1]. High reproducibility (Pearson correlation coefficient >0.8) between biological replicates allows for combined analysis to increase statistical power [1].

Problem: Excessive Repression or Cell Toxicity

- Potential Cause: Excessive repression of an essential gene or high off-target activity.

- Solution: For essential genes, titrate the expression level of the guide RNA or dCas9-repressor to achieve partial knockdown rather than complete repression. To enhance specificity, use bioinformatic tools to minimize off-target sgRNA designs and consider validated, high-specificity repressor domains like dCas9-SALL1-SDS3 [2].

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Key Quantitative Benchmarks for CRISPRi Screens [1]

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | ≥ 200x per sample | Critical for statistical power. |

| sgRNAs per Gene | 3-4 | Mitigates variability in individual sgRNA efficiency. |

| Library Coverage | > 99% | Ensures all library elements are represented. |

| Replicate Correlation | Pearson R > 0.8 | Indicates high reproducibility for combined analysis. |

Table 2: CRISPRi Repression Performance (Selected Examples)

| Cell Line / System | Target Gene(s) | Repression Efficiency | Key Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U2OS cells | 21 genes with varying basal expression | Down to 20-25% of basal levels | Repression potency is independent of endogenous expression levels [2]. | [2] |

| Pseudomonas putida (Metabolic Engineering) | PP_4118 (α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase) | N/A | Knockdown led to ~1.5 g/L isoprenol titer, demonstrating effective flux redirection [5]. | [5] |

| WTC-11 human iPS cells | PPIB, SEL1L, RAB11A (Multiplexed) | Significant repression of all three | Validated simultaneous knockdown of multiple genes without major viability impact [2]. | [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Basic Workflow for CRISPRi-Mediated Gene Knockdown This protocol outlines the steps for transient gene repression using synthetic sgRNAs in cells expressing a dCas9-repressor.

- sgRNA Design: Design and procure 3-4 synthetic sgRNAs per target gene, using a validated algorithm that targets the region 0-300 bp downstream of the annotated TSS [2].

- Cell Seeding: Plate cells stably expressing the dCas9-repressor protein (e.g., dCas9-KRAB or dCas9-SALL1-SDS3) at an appropriate density (e.g., 10,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate) [2].

- Transfection: Transfect cells with the synthetic sgRNA pool or individual sgRNAs using a suitable transfection reagent (e.g., DharmaFECT 4). Include a non-targeting control (NTC) sgRNA.

- Incubation: Harvest cells at the optimal time point for analysis, typically 72 hours post-transfection [2].

- Validation:

- Molecular: Isolate total RNA and measure relative gene expression changes using RT-qPCR. Calculate relative expression using the ∆∆Cq method normalized to the NTC and a housekeeping gene [2].

- Phenotypic: Perform subsequent functional assays based on the target's function (e.g., metabolic flux analysis, growth assays).

Protocol 2: Computational-Predictive CRISPRi for Metabolic Engineering This advanced protocol integrates computational prediction to identify optimal gene knockdown targets for enhancing bioproduction [5].

- Target Prioritization: Use a computational tool like FluxRETAP (Flux-Reaction Target Prioritization) to analyze the metabolic network and rationally identify gene targets whose knockdown is predicted to enhance the production of your desired compound [5].

- Multiplexed Construct Assembly: Use a versatile assembly method like VAMMPIRE (Versatile Assembly Method for MultiPlexing CRISPRi-mediated downREgulation) to efficiently build CRISPRi constructs containing arrays of multiple sgRNAs (e.g., up to five) targeting the prioritized genes [5].

- Strain Engineering & Screening: Introduce the multiplexed CRISPRi construct into the host microbial system (e.g., Pseudomonas putida).

- Bioreactor Cultivation & Analysis: Grow the engineered strains under production conditions and measure the titers of the target bio-product (e.g., isoprenol) to validate the computational predictions [5].

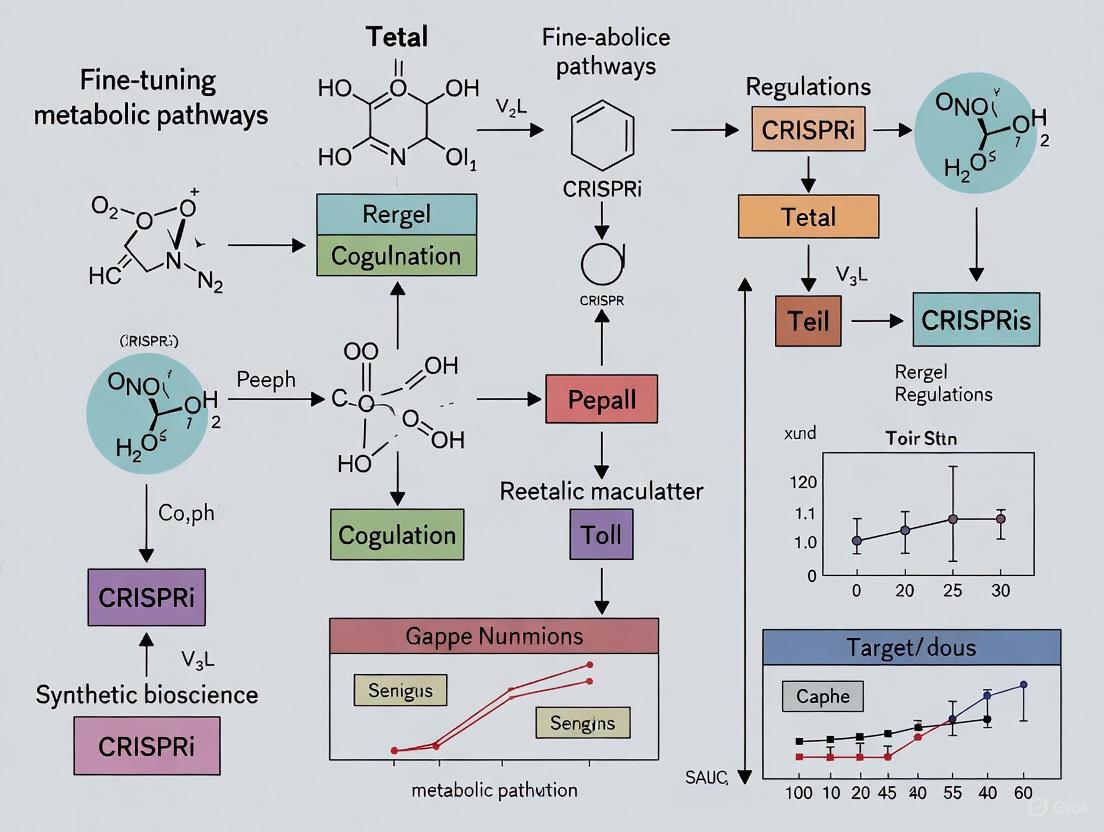

Essential Diagrams and Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPRi Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Repressor Fusion | Core effector protein; binds DNA without cutting and recruits transcriptional repressors. | Choose a potent repressor domain (e.g., KRAB or proprietary SALL1-SDS3). Can be delivered via stable cell line, mRNA, or protein [2] [4]. |

| CRISPRi sgRNA | Guides the dCas9-repressor to the specific DNA target site near the TSS. | Use algorithm-optimized designs. Synthetic sgRNAs offer speed and reduced off-targets; pooled sgRNAs can enhance repression [2] [4]. |

| Delivery Vehicle | Introduces genetic material into cells. | Choice depends on cell type: Lentivirus (stable expression), Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) (e.g., for in vivo), or Electroporation (hard-to-transfect cells) [2] [6]. |

| Validated Positive Control sgRNA | Provides a benchmark for repression efficiency and experimental validation. | Use a well-characterized target (e.g., PPIB) to confirm system functionality in your specific cell type [2]. |

| Non-Targeting Control (NTC) sgRNA | Essential control for distinguishing specific from non-specific effects. | A sgRNA with no perfect match in the host genome, crucial for normalizing RT-qPCR data and assessing background [2]. |

Core Mechanism: How dCas9 Achieves Cleavage-Free Repression

FAQ: What is the fundamental difference between Cas9 and dCas9?

Catalytically deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) is generated by introducing specific point mutations into the two nuclease domains of the native Cas9 protein. The most common mutations, D10A in the RuvC domain and H840A in the HNH domain (for S. pyogenes Cas9), abolish the protein's ability to cleave DNA [7]. While dCas9 cannot cut DNA, it retains its fundamental ability to bind to DNA in a guide RNA-directed manner. This binding forms the basis for its use as a programmable transcription blocker.

FAQ: How does the mere binding of dCas9 to DNA silence gene expression?

dCas9, when complexed with a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), is directed to a specific target DNA sequence adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). Upon binding, it creates a physical, steric barrier that impedes the essential machinery of transcription [8]. dCas9 can be targeted to the transcription start site (TSS) of a gene to prevent the binding and initiation of RNA Polymerase (RNAP). Furthermore, if dCas9 binds within the coding region downstream of the TSS, it can still effectively block the elongation phase of transcription by physically obstructing the progress of the RNAP along the DNA template [9] [8]. This mechanism is known as steric hindrance.

The following diagram illustrates this steric hindrance mechanism.

Enhanced Repression: Beyond Steric Hindrance

FAQ: Why do most CRISPRi systems use dCas9 fused to repressor domains like KRAB?

While dCas9 alone can provide repression via steric hindrance, the level of gene knockdown is often incomplete. To achieve stronger, more potent silencing, dCas9 is commonly fused to transcriptional repressor domains [10]. The most widely used repressor is the Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) domain derived from human proteins. When the dCas9-KRAB fusion is recruited to a gene promoter by the sgRNA, the KRAB domain recruits a complex of co-repressor proteins. This complex initiates a local reorganization of the chromatin into a more closed, transcriptionally inactive state, a phenomenon known as heterochromatinization. This is achieved through the modification of histones, such as the addition of methyl groups (H3K9me3), which effectively silences the target gene [10].

Recent research has focused on engineering more powerful repressors by combining multiple repressor domains. For instance, a novel fusion protein, dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t), which combines a potent KRAB domain (ZIM3) with a truncated MeCP2 repressor domain, has demonstrated significantly improved gene repression across multiple cell lines and gene targets compared to earlier standards like dCas9-KOX1(KRAB) [10]. The table below summarizes key repressor domains and their performance.

Table 1: Key dCas9 Repressor Domains and Their Performance Characteristics

| Repressor Domain | Type | Reported Performance & Characteristics | Key Findings from Recent Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| KOX1(KRAB) | KRAB Domain | The original gold standard; provides strong repression. | Serves as a benchmark, but outperformed by newer KRAB domains [10]. |

| ZIM3(KRAB) | KRAB Domain | Superior repressor; improves gene silencing efficiency. | Demonstrated significantly better knockdown than KOX1(KRAB) in comparative studies [10]. |

| MeCP2 (full) | Non-KRAB | Effective partner for KRAB domains in bipartite repressors. | A 283aa truncation; used in the established dCas9-KOX1(KRAB)-MeCP2 system [10]. |

| MeCP2(t) | Non-KRAB | A minimal, 80aa truncated version. | Retains similar repressive activity as the full MeCP2 domain, offering a size benefit [10]. |

| dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) | Bipartite Fusion | A next-generation CRISPRi platform. | Provides ~20-30% better knockdown than dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB) alone; reduced performance variability across sgRNAs and cell lines [10]. |

The mechanism of this enhanced, multi-domain repression is detailed in the following diagram.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: My CRISPRi repression is inefficient. What could be wrong?

Inefficient repression is a common challenge. The solution requires optimizing several key parameters, as outlined in the troubleshooting guide below.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for CRISPRi Experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Optimization Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Low Repression Efficiency | - sgRNA binds too far from the Transcription Start Site (TSS).- Weak sgRNA binding affinity.- Use of a weak repressor domain. | - Target sgRNAs within -50 to +300 bp relative to the TSS [9].- Use high-fidelity sgRNA design tools to select guides with high on-target scores [11].- Upgrade to a more potent repressor system (e.g., dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t)) [10]. |

| High Variability Across sgRNAs | - Intrinsic differences in sgRNA binding efficiency due to local DNA sequence/structure. | - Test 2-3 different sgRNAs per target to identify the most effective one [12].- Utilize engineered sgRNA libraries with modified scaffolds to achieve more uniform performance [9]. |

| Cell Toxicity or Poor Transfection | - Overexpression of dCas9-repressor fusions can cause cellular stress.- The delivery method is inefficient for your cell type. | - Use tunable induction systems (e.g., aTc-inducible) to express dCas9 at minimal effective levels [9] [13].- Consider switching delivery method (e.g., from plasmid to ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for hard-to-transfect cells) [12]. |

| Off-Target Effects | - sgRNA has partial complementarity to unintended genomic sites. | - Use computationally predicted high-specificity sgRNAs.- Employ high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) as the base for dCas9 to enhance specificity [7]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful CRISPRi experiment depends on having the right molecular tools. The table below lists the essential reagents and their functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPRi Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Vector | Plasmid encoding the catalytically dead Cas9 protein, often fused to a repressor domain. | - Available with various repressor fusions (e.g., dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2).- May use inducible promoters for controlled expression. |

| sgRNA Expression Vector | Plasmid or locus for expressing the single-guide RNA that provides targeting specificity. | - Can be cloned into a vector separate from dCas9 or in an all-in-one system.- Multiplexing vectors allow simultaneous expression of multiple sgRNAs [7]. |

| Repressor Domains | Protein domains fused to dCas9 to actively silence transcription via chromatin modification. | - KRAB Domains: KOX1(KRAB), ZIM3(KRAB), KRBOX1(KRAB).- Other Domains: MeCP2, SCMH1, RCOR1 [10]. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNAs | Synthetic sgRNAs with chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl) to enhance stability and editing efficiency. | - Reduces degradation by cellular RNases.- Can elicit lower immune response and less toxicity than in vitro transcribed guides [12]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | Pre-assembled complexes of dCas9 protein and sgRNA delivered directly into cells. | - Enables "DNA-free" editing, reducing off-target effects and integration concerns.- Leads to rapid, high-efficiency repression and is ideal for hard-to-transfect cells [12]. |

| Delivery Tools | Methods for introducing CRISPRi components into target cells. | - Chemical: Lipofection.- Physical: Electroporation.- Viral: Lentivirus, AAV (particularly useful for in vivo applications and primary cells) [14]. |

| Hdac-IN-42 | HDAC-IN-42|Potent HDAC Inhibitor for Research | |

| PI3K/Akt/mTOR-IN-2 | PI3K/Akt/mTOR-IN-2, MF:C17H13F2NO, MW:285.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocol: Testing a Novel dCas9-Repressor Fusion

This protocol outlines the key steps for evaluating the efficacy of a newly constructed dCas9-repressor fusion protein, such as dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t), using a fluorescent reporter assay [10].

1. Molecular Cloning and Plasmid Preparation:

- Clone the dCas9-Repressor Fusion: Insert the gene encoding your novel dCas9-repressor fusion (e.g., ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t)) into a mammalian expression vector with a selectable marker (e.g., puromycin resistance).

- Clone the sgRNA Expression Vector: Design and clone sgRNAs targeting the promoter region of a reporter gene (e.g., eGFP) into a separate expression vector.

- Prepare the Reporter Construct: Use a plasmid containing eGFP under the control of a constitutive promoter (e.g., SV40 or CMV).

2. Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Culture appropriate cells (e.g., HEK293T) under standard conditions.

- Co-transfect the cells with the three plasmids: the dCas9-repressor fusion vector, the sgRNA vector, and the eGFP reporter vector. Include critical controls:

- Negative Control: Cells transfected with dCas9-repressor + a non-targeting sgRNA.

- Baseline Control: Cells transfected with the eGFP reporter only.

3. Analysis and Validation:

- Flow Cytometry: 48-72 hours post-transfection, analyze the cells using flow cytometry to measure the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of eGFP.

- Calculate Repression Efficiency: Repression efficiency is calculated as:

[1 - (MFI_sample / MFI_negative_control)] * 100%. - Statistical Analysis: Perform the experiment with multiple biological replicates (e.g., n=6) to ensure statistical significance.

- Western Blotting: Confirm the expression and integrity of the dCas9-repressor fusion protein in transfected cells.

By systematically following this protocol and utilizing the troubleshooting guide, researchers can reliably implement and optimize CRISPRi systems for precise metabolic pathway engineering and functional genomic studies.

FAQ: Core Principles and Applications

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between CRISPRi and traditional CRISPR knockout?

Traditional CRISPR-Cas9 knockout uses a nuclease-active Cas9 to create permanent double-strand breaks in DNA, leading to gene disruption. In contrast, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) uses a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) that lacks nuclease activity. dCas9 binds to target DNA without cutting it, thereby physically blocking transcription initiation or elongation. This mechanism allows for reversible and tunable gene repression rather than permanent disruption [9].

Q2: Why are reversibility and tunability critical for metabolic pathway engineering?

In metabolic engineering, complete and permanent gene knockout is often suboptimal. Fine-tuning gene expression is essential to:

- Balance intracellular precursor concentrations and avoid the accumulation of toxic intermediates.

- Redistribute metabolic flux predictably between growth and production pathways.

- Enable dynamic control strategies where gene expression can be adjusted at different fermentation stages, which is impossible with permanent knockouts [9] [15].

Q3: What are the main methods for achieving tunable control with CRISPRi?

Tunability is achieved primarily through two strategies:

- Modulating sgRNA binding affinity: Engineering the sgRNA sequence, particularly in the tetraloop and anti-repeat regions, to create a library of sgRNAs with varying repression strengths [9].

- Using inducible promoters: Controlling the expression of dCas9, sgRNA, or both with inducible systems (e.g., aTc-inducible) to allow dose-dependent repression [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Q4: We observe inconsistent repression efficiencies across different target genes. What could be the cause?

This is a common challenge. The performance of an sgRNA can be highly dependent on its target sequence and genomic context.

- Solution: Do not rely on a single sgRNA per target. Utilize a pre-screened library of sgRNA mutants with modifications in the tetraloop and anti-repeat regions. These libraries provide a range of repression efficiencies (e.g., from 0% to over 95%), allowing you to select an sgRNA that delivers the precise level of knockdown required, independent of the target DNA sequence [9].

Q5: How can we confirm that our CRISPRi system is reversible?

Reversibility is a key advantage. To confirm it in your experiment:

- Method: After inducing repression (e.g., by adding a chemical inducer like aTc), remove the induction agent. For systems where dCas9/sgRNA expression is driven by an inducible promoter, this will halt the production of the CRISPRi machinery. Monitor gene expression (via RT-qPCR) or protein function over time. You should observe a gradual recovery to baseline levels as the dCas9-sgRNA complex dilutes through cell division [9]. For ultimate reversibility, anti-CRISPR proteins can be used to rapidly disassemble the dCas9 complex [16].

Q6: Our CRISPRi repression is too weak for effective flux control. How can we enhance it?

- Solution 1: Use a more potent dCas9 repressor fusion. Screen and employ advanced repressor domains. For instance, a dCas9 fused with a ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) repressor platform has demonstrated improved gene repression with reduced performance variability across guide RNAs and cell lines [17].

- Solution 2: Employ multiplexed sgRNAs. Target multiple sites within the same gene's promoter or coding sequence simultaneously. Using two sgRNAs against essential phage genes has been shown to have a synergistic effect, resulting in near-complete inhibition, whereas single sgRNAs only reduced function [18].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Repression Efficiencies

Table 1: Summary of Tunable CRISPRi Repression Ranges

| System / Method | Repression Efficiency Range | Key Findings / Application Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Library (Tetraloop/Anti-repeat) | >45-fold dynamic range | Library provided a set of sgRNAs enabling predictable, modular repression levels for flux redistribution in violacein and lycopene production. | [9] |

| Inducible dCas9 & sgRNA | >300-fold dynamic range | Controlling both dCas9 and sgRNA expression with an inducible promoter allows for very wide dynamic control of the target gene. | [9] |

| Enhanced dCas9-Repressor (dCas9-ZIM3) | Improved efficiency & reduced variance | This repressor fusion platform showed improved gene knockdown across multiple cell lines and in genome-wide screens, offering greater reproducibility. | [17] |

| Multiplexed sgRNAs (Phage Inhibition) | Synergistic, near-complete inhibition | Using two crRNAs simultaneously against essential genes nearly eliminated plaque formation, while single crRNAs only reduced plaque size. | [18] |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a Tunable CRISPRi System

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing a tunable CRISPRi system for metabolic flux control, based on the methodology used to optimize L-proline production in Corynebacterium glutamicum [15].

Goal: Fine-tune the expression of flux-control genes in a metabolic pathway.

Materials:

- Plasmids: Vectors for expressing dCas9-repressor fusions (e.g., dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2) and sgRNA.

- sgRNA Library: A pre-designed arrayed library of sgRNA mutants targeting the tetraloop and anti-repeat regions.

- Host Strain: Your engineered production strain (e.g., C. glutamicum, E. coli).

- Induction Agent: If using an inducible system (e.g., anhydrous tetracycline, aTc).

- Analytical Equipment: HPLC, GC-MS, or spectrophotometer for measuring metabolite titer; plate reader for fluorescence-based sorting.

Procedure:

In Silico Analysis and Target Selection:

- Use genome-scale metabolic models to predict key flux-control nodes (genes) in your pathway of interest.

- Design sgRNA spacer sequences to target the promoter or 5' coding region of these genes.

Library Construction and Screening:

- Clone the spacer sequences into the mutant sgRNA backbone library.

- Transform the pooled sgRNA library and the dCas9-repressor plasmid into your host strain.

- Use iterative fluorescence-based cell sorting to screen the library. Fuse a fluorescent reporter to your gene of interest or a downstream metabolic proxy. Sort cells based on fluorescence intensity (which correlates with repression level) to isolate clones with desired repression strengths.

Validation of Repression Efficiency:

- Inoculate single colonies from the sorted library and culture with induction (if applicable).

- Measure final product titer (e.g., L-proline) and growth.

- Validate gene knockdown at the mRNA level using RT-qPCR [9].

- Technical Note for RT-qPCR: Use 2.5 ng of total RNA in a 10 µL reaction with a one-step RT-qPCR kit. Perform the reaction in triplicate with the following steps: reverse transcription at 55°C for 10 min; denaturation at 95°C for 1 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 1 min; followed by melt curve analysis. Use a stable reference gene (e.g., CysG for bacteria) for relative quantification via the delta-delta-Ct method [9].

Fermentation and Flux Analysis:

- Scale up the best-performing strains in bioreactors.

- Monitor metabolite concentrations and growth over time to confirm the predicted redistribution of metabolic flux and achieve hyperproduction (e.g., 142.4 g/L L-proline as demonstrated) [15].

Visualizing the CRISPRi Mechanism and Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Tunable CRISPRi Strain Development

Diagram Title: Mechanism of Reversible CRISPRi vs Permanent Knockout

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for CRISPRi-based Metabolic Tuning

| Reagent / Component | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Repressor Fusion (e.g., dCas9-ZIM3) | Binds DNA target without cutting and recruits transcriptional repressors to silence gene expression. | Potent repressor domains (like ZIM3-KRAB) improve knockdown efficiency and reduce performance variability [17]. |

| Tunable sgRNA Library | A collection of sgRNAs with mutations in tetraloop/anti-repeat regions, providing a range of repression strengths. | Enables predictable, modular control of gene expression levels regardless of the target DNA sequence [9]. |

| Inducible Expression System | Allows precise, dose-dependent control over the timing and level of dCas9 and/or sgRNA expression. | Systems like aTc-inducible promoters enable dynamic experiments and reversibility studies [9]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Gene | Serves as a proxy for gene expression or metabolic flux level during high-throughput screening. | Allows for isolation of cells with desired repression levels using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [9]. |

| GMP-Grade gRNA & Nucleases | Critical for transitioning research findings to clinical trials, ensuring purity, safety, and efficacy. | Procuring true GMP-grade (not "GMP-like") reagents is essential for regulatory approval and patient safety [19]. |

| Potentillanoside A | Potentillanoside A: Hepatoprotective Natural Compound | Potentillanoside A is a triterpenoid with proven hepatoprotective effects for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Xylose-d2 | Xylose-d2 Deuterated Sugar for Research | High-purity Xylose-d2 for metabolism, tracer, and MS studies. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues with dCas9-based Systems

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when using dCas9 effectors for metabolic pathway engineering, specifically within the context of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and activation (CRISPRa).

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common dCas9 Experimental Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low editing or regulation efficiency [20] [21] | Suboptimal gRNA design, ineffective delivery method, or low expression of dCas9 components. | Design highly specific gRNAs using prediction tools. Optimize delivery (electroporation, lipofection, viral vectors) for your cell type. Use a strong, cell-type-appropriate promoter for dCas9 and gRNA expression [20]. |

| Off-target effects (dCas9 binds to unintended sites) [20] [22] | gRNA is not specific enough and has homology with other genomic regions. | Utilize online algorithms to design specific gRNAs and predict potential off-target sites. Consider using high-fidelity dCas9 variants engineered for reduced off-target activity [20]. |

| Cell toxicity [20] | High concentrations of CRISPR-dCas9 components. | Titrate component concentrations, starting with lower doses. Use dCas9 protein with a nuclear localization signal to enhance targeting and reduce cytotoxicity [20]. |

| Inability to detect successful regulation | Insensitive genotyping methods or low regulation efficiency. | Employ robust methods like qRT-PCR to measure changes in transcript levels of your target metabolic genes. Use proper positive and negative controls [20]. |

| No regulation effect | The target sequence is inaccessible, or the PAM site is not optimal. | Design a new gRNA targeting a different site within the promoter or gene of interest. Ensure the target site is adjacent to a compatible PAM (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for Sp-dCas9) [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the core difference between CRISPR-Cas9 and CRISPR-dCas9? A: The standard CRISPR-Cas9 system uses an active Cas9 nuclease to create double-strand breaks in DNA, permanently editing the genetic sequence. dCas9 is a "catalytically dead" Cas9 that lacks nuclease activity. It still binds to DNA based on the gRNA guide but does not cut it. Instead, it serves as a programmable platform to block transcription (CRISPRi) or, when fused to effector domains, to activate it (CRISPRa) [22] [23].

Q: For metabolic pathway engineering, when should I use CRISPRi versus CRISPRa? A: Use CRISPRi to downregulate or silence genes in a competitive pathway that drains metabolites away from your desired product, or to reproduce natural feedback inhibition mechanisms. Use CRISPRa to upregulate or overexpress key bottleneck enzymes in your biosynthetic pathway of interest [23]. They can be used in combination to fine-tune metabolic flux.

Q: How can I achieve multiplexed regulation to engineer complex metabolic pathways? A: A powerful approach is to use scaffold RNA (scRNA) systems. By fusing the standard sgRNA with additional RNA aptamer modules (like MS2 or PP7), you can recruit different effector proteins (activators, repressors) to multiple genomic locations simultaneously. This allows for coordinated and complex regulation of several pathway genes at once [24] [23].

Q: What are the key advantages of using a dual dCas9-dCpf1 system? A: dCas9 and dCpf1 (a Type V CRISPR system) are orthogonal, meaning they do not exhibit crosstalk and can function independently in the same cell. This allows for simultaneous and independent activation and repression of different genes. dCpf1 also uses a different PAM (TTN), expanding the range of targetable sequences in the genome [24].

Q: How can I improve the specificity of my dCas9 system to minimize off-target effects? A: Carefully design gRNAs to be highly unique to your target sequence using specialized software [11]. Additionally, you can use "high-fidelity" dCas9 variants that have been engineered to reduce off-target binding. Always include appropriate controls to confirm the on-target specificity of your observed phenotypes [20].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Multiplexed CRISPRa/i for Metabolic Pathway Balancing

This protocol outlines a method for simultaneously activating and repressing multiple genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a modular scRNA system, as demonstrated for β-carotene pathway engineering [24].

- gRNA and scRNA Design: Design gRNAs to target the promoter regions of genes you wish to upregulate (e.g., rate-limiting enzymes in the β-carotene pathway) and those you wish to repress (e.g., competing pathways). For multiplexing, design scRNAs by extending the sgRNA with aptamer loops like MS2 or PP7.

- Effector Plasmid Construction: Clone the gene for dCas9 fused to a transcriptional activator (e.g., VP64-p65-Rta for activation) into one plasmid. Clone the gene for a compatible effector (e.g., dCpf1) fused to a repressor domain (e.g., KRAB-MeCP2) into a second plasmid.

- Expression Library Construction: Clone your designed gRNA/scRNA sequences into expression vectors under RNA polymerase III promoters. For large-scale screening, create a library of 100+ plasmid variants.

- Transformation and Screening: Co-transform the effector plasmids and the gRNA library into your host yeast strain. Culture the transformed cells in selective media.

- Validation and Analysis: Screen for successful pathway engineering by measuring:

- Product Titer: β-carotene production via HPLC.

- Transcript Levels: Gene expression changes for targeted genes via qRT-PCR.

- Flux Analysis: Use metabolomics to confirm redirection of metabolic flux.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Assessment of Promoter Strength Using dCas9 Effectors

This methodology describes how to quantify the regulatory capacity of different promoters or gRNA-effector combinations [24].

- Reporter Strain Construction: Integrate a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., mCherry) downstream of the promoter you wish to characterize into the host genome.

- dCas9-Effector Delivery: Introduce plasmids expressing dCas9 fused to various effector domains (e.g., VP64, p65, Rta, or combinations for activation; KRAB, MeCP2 for repression) along with a gRNA targeting your test promoter.

- Cultivation and Measurement: Grow cultures of the engineered strains under defined conditions and measure the fluorescence intensity of the reporter using a microplate reader or flow cytometer.

- Data Calculation: Calculate the regulation rate as a percentage of the control strain (without dCas9 regulation). The study achieved regulation rates from 81.9% suppression to 627% activation [24].

System Workflows and Logical Diagrams

Diagram 1: Metabolic Pathway Engineering Workflow.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Logic for Low Efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for dCas9-Mediated Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Component | Function in the Experiment | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Vector | Catalytically dead Cas9 base; programmable DNA-binding platform. | Fuse with effector domains (KRAB, VP64) for CRISPRi/a. Ensure codon-optimization for your host organism [23]. |

| Effector Domains | Provides transcriptional regulatory function. | KRAB & MeCP2: For strong repression (CRISPRi). VP64, p65, Rta: For activation (CRISPRa). Fuse to dCas9 [24]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Directs dCas9-effector complex to specific DNA sequence. | Target promoter regions for transcriptional control. Specificity is critical to avoid off-target effects [20]. |

| Scaffold RNA (scRNA) | Enables multiplexed regulation by recruiting multiple effectors. | Extend sgRNA with RNA aptamers (MS2, PP7) to recruit additional activator/repressor proteins [24] [23]. |

| Orthogonal System (dCpf1) | Enables independent, simultaneous regulation with dCas9. | dCpf1 uses a different PAM (TTN) and a shorter crRNA, allowing dual-pathway regulation without crosstalk [24]. |

| Reporter Genes | Quantitatively measures the strength of regulation. | Fluorescent proteins (mCherry, eGFP) are used in reporter systems to measure transcriptional output [24]. |

| L-Methionine-13C5 | L-Methionine-13C5, MF:C5H11NO2S, MW:154.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (Sar1)-Angiotensin II | (Sar1)-Angiotensin II | (Sar1)-Angiotensin II is a potent AT1 receptor ligand for cardiovascular and RAS research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

From Theory to Bioproduction: Implementing CRISPRi in Metabolic Engineering

Engineering Microbial Consortia with CRISPRi for Concurrent Fermentations

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common CRISPRi Experimental Challenges

This guide addresses specific issues researchers may encounter when applying CRISPRi to engineer microbial consortia for fermentation processes.

Q1: My CRISPRi-mediated gene repression in a microbial consortium is showing variable efficiency between different population members. How can I improve consistency?

- Problem: Inconsistent repression efficiency across consortium members can lead to unbalanced metabolic pathways and suboptimal fermentation output.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Variable sgRNA specificity or efficiency. Low-specificity sgRNAs can cause artifacts and inconsistent repression [25].

- Solution: Utilize established design tools and validated sgRNA libraries. Benchmarking studies recommend tools like CASA for conservative and robust CRE (cis-regulatory element) calls, which can be analogously applied to coding gene targets to ensure specificity [25].

- Cause: Differences in dCas9 and sgRNA expression levels between microbial strains.

- Solution: Standardize genetic constructs using validated, compatible vectors. For example, in cyanobacteria, systems like SyneBrick expression vectors for chromosomal integration at neutral sites have been successfully used to ensure stable and comparable expression [26]. Use constitutive promoters with known, similar strengths across your target host species.

- Cause: Cell-to-cell variability in delivery or expression.

- Solution: For plasmid-based systems, ensure the same selection pressure is maintained across all populations in the consortium. Consider using genome-integrated systems for more stable inheritance [26] [27].

Q2: My engineered microbial consortium becomes unstable over multiple fermentation batches, with one strain outcompeting others. How can I enforce stable coexistence?

- Problem: Dominance of a fast-growing population disrupts the division of labor, leading to consortium collapse and process failure.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Unmitigated competition for nutrients and space [28].

- Solution: Engineer stable, mutualistic interactions. Design strains to be mutually dependent by having each strain produce an essential metabolite or signal required by the other. For instance, in a co-culture of E. coli and S. cerevisiae, E. coli's growth-inhibiting acetate was consumed by yeast as a carbon source, creating a stable, productive mutualism [28].

- Cause: Lack of population control mechanisms.

- Solution: Implement programmed population control using synthetic circuits. One demonstrated strategy uses orthogonal synchronized lysis circuits (SLC). Each engineered population produces a quorum-sensing molecule that, at a high density, induces its own lysis. This negative feedback prevents any single population from overgrowing and allows stable co-culture of strains with different inherent growth rates [28].

- Cause: Inadequate spatial structuring.

- Solution: Leverage natural biofilm formation or use engineered living materials (ELMs) to create spatial niches. Inspired by natural systems like kombucha SCOBYs, coculturing specialized cells within a bacterial cellulose matrix can provide a structured environment that supports consortium stability and function [29].

Q3: I am not achieving the expected increase in target metabolite production after using CRISPRi to repress a competing pathway. What could be wrong?

- Problem: Redirecting metabolic flux via gene repression does not yield the expected increase in product titer.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Incomplete repression or hidden metabolic redundancies.

- Solution: Conduct a thorough genetic interaction analysis. Techniques like CRISPRi–TnSeq can map genome-wide interactions between essential and non-essential genes, revealing compensatory pathways or hidden redundancies that buffer against the repression of your target gene [30]. You may need to repress multiple genes simultaneously.

- Cause: Imbalance in precursor pools or unintended metabolic bottlenecks.

- Solution: Perform modular pathway engineering and fine-tune multiple nodes. As demonstrated in cyanobacteria for hyaluronic acid production, simultaneously repressing two genes (zwf and pfk) at key metabolic nodes (F6P and G6P) was far more effective than single gene repressions, leading to a significant 27.5-fold increase in product yield [26].

- Cause: Excessive metabolic burden leading to low growth and productivity.

- Solution: Distribute the metabolic pathway across the consortium via division of labor (DOL). This strategy alleviates the burden on any single strain, simplifies circuit optimization, and can improve overall pathway efficiency and product yield [28] [29].

Q4: The editing efficiency in my non-model microbial host is very low. How can I optimize CRISPRi delivery and function?

- Problem: Low transformation efficiency or poor CRISPRi function hinders genetic engineering of consortium members.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient delivery of CRISPR machinery.

- Solution: Optimize transformation methods. For bacteria with thick cell walls, conjugative transfer from an intermediate E. coli strain is often effective, though library coverage must be carefully managed [27]. Systematically optimize delivery parameters; one platform tests up to 200 electroporation conditions in parallel to find the optimal protocol for a given cell line, boosting editing efficiency from 7% to over 80% in difficult cells [31].

- Cause: Poor expression or function of dCas9/sgRNA in the host.

- Solution: Use codon-optimized genes and host-specific promoters. The heterologous genes in the cyanobacterium S. elongatus were codon-optimized using Gene Designer for effective expression [26]. Ensure the CRISPRi system is functional in your host; in Shewanella oneidensis, a genome-wide CRISPRi library was successfully established by carefully designing sgRNAs and tailoring conjugative transfer [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the key advantages of using CRISPRi over permanent knockout for metabolic engineering in consortia? A: CRISPRi offers several advantages for tuning consortia: First, it allows for tunable and reversible repression using inducible promoters, enabling dynamic control of metabolic fluxes without permanently altering the genome [26]. Second, it enables the study of essential genes that would be lethal if knocked out, which is crucial for understanding core metabolism and network interactions [30]. Third, it avoids off-target mutations associated with double-strand break repair, leading to more genetically stable production strains [32].

Q: How do I design an effective sgRNA for CRISPRi repression? A: Effective sgRNA design follows several key principles [25] [27]:

- Specificity: Ensure the sgRNA sequence is unique to your target to minimize off-target effects. Use prediction tools to check for potential off-target sites.

- Target Location: For CRISPRi using dCas9, target the non-template DNA strand within the promoter region or early in the coding sequence to sterically block transcription initiation or elongation.

- GC Content & Sequence: Follow established design rules for your system. For example, in the Shewanella CRISPRi library, sgRNAs were designed with a specific length (20-bp spacer), and sequences with homopolymers or self-complementarity were avoided [27].

Q: Can I use CRISPRi to simultaneously repress multiple genes in a consortium? A: Yes, multiplexed repression is a powerful application. This can be achieved by expressing multiple sgRNAs from a single array or by using CRISPRi systems based on different Cas proteins (e.g., dCas9 and dCas12a) that have distinct PAM requirements, allowing for orthogonal targeting [26] [30]. In one example, a dCas12a-mediated system in cyanobacteria was used to repress both zwf and pfk genes simultaneously, successfully redirecting carbon flux [26].

Q: What are the primary challenges in screening for desired traits in CRISPRi-engineered electroactive consortia? A: A major limitation is the lack of efficient, growth-based screening methods for complex phenotypes like extracellular electron transfer (EET). Since EET involves intertwined processes like biofilm formation and redox mediation, growth-based assays often fail to capture these electroactive traits directly. Developing advanced, phenotype-specific screening methods is an active area of research [27].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: CRISPRi-Mediated Metabolic Engineering for Hyaluronic Acid Production in Cyanobacteria

This table summarizes the key experimental data from a study that engineered the cyanobacterium Synechoccous elongatus PCC 7942 for photosynthetic HA production from COâ‚‚ using CRISPRi [26].

| Engineered Strain | Genetic Modifications / Repression Target(s) | Hyaluronic Acid Titer (mg/L) | Key Finding / Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (SeHA100) | Expression of heterologous hyaluronan synthase (hasA) only. | Low (Baseline) | Established baseline production capability. |

| SeHA220 | Modular expression of HA-GlcA and GlcNAc precursor pathway genes. | 2.4 ± 0.85 (at 21 days) | A 27.5-fold increase over control, demonstrating the success of modular pathway engineering. |

| SeHA226 | SeHA220 + CRISPRi repression of zwf and pfk. | 5.0 ± 0.3 (at 15 days) | Dual gene repression further enhanced titer and accelerated production, yielding high-molecular-weight (4.2 MDa) HA. |

Detailed Methodology from [26]:

- Strain Construction: Heterologous genes (hasA, hasB, hasC, glmU, glmM, glmS) were codon-optimized for S. elongatus PCC 7942 and assembled into a modular expression system using SyneBrick vectors. These were integrated into specific neutral sites (NSI, NSII) on the chromosome.

- CRISPRi System: A dCas12a protein was expressed from a separate vector integrated at NSIII, under an inducible promoter (Ptrc) with a LacIq repressor. Induction was achieved with 1 mM IPTG.

- crRNA Design: crRNAs were designed to target the chromosomal genes zwf (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) and pfk (phosphofructokinase) for repression.

- Culture & Analysis: Strains were cultured in liquid medium bubbled with air enriched with 2-5% COâ‚‚. HA titer was quantified from the culture supernatant, and molecular weight was analyzed.

Table 2: Genetic Interaction Mapping with CRISPRi-TnSeq inStreptococcus pneumoniae

This table outlines the setup and key results from a study using CRISPRi-TnSeq to map genetic interactions genome-wide [30].

| Experimental Component | Description / Outcome |

|---|---|

| Objective | Map genome-wide genetic interactions between essential and non-essential genes. |

| Method | Combine CRISPRi knockdown of an essential gene with TnSeq knockout of non-essential genes in a pooled library. |

| Scale | Screened ~24,000 gene-gene pairs across 13 essential genes. |

| Identified Interactions | 1,334 significant genetic interactions (754 negative, 580 positive). |

| Key Insight | Identified 17 highly "pleiotropic" non-essential genes that interact with over half of the targeted essential genes, revealing global modulators of cellular stress. |

| Validation | A 7-gene subset of these pleiotropic genes was experimentally validated as protecting against various perturbations. |

Detailed Methodology from [30]:

- Library Creation: Tn-mutant libraries were constructed in 13 different S. pneumoniae strains, each containing an inducible CRISPRi system targeting a specific essential gene.

- Dual Perturbation Screening: Each Tn-mutant library was grown with and without the CRISPRi inducer (IPTG). Fitness of each non-essential gene knockout was measured with and without the simultaneous knockdown of the essential gene.

- Interaction Scoring: A significant deviation from the expected multiplicative fitness effect indicated a genetic interaction (negative if growth was worse, positive if growth was better).

- Analysis: Network analysis and gene set enrichment were used to identify functional modules and pleiotropic genes.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPRi in Microbial Consortia

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9/dCas12a | Catalytically "dead" Cas protein; binds DNA without cutting, blocking transcription. | Core component of the CRISPRi system. dCas9 is most common; dCas12a offers orthogonal PAM targeting [26] [27]. |

| sgRNA/crRNA Expression Vectors | Deliver the guide RNA sequence to target dCas to specific genomic loci. | Can be on plasmids or integrated into the genome. Libraries contain thousands of unique sgRNAs [25] [27]. |

| Codon-Optimized Genes | Ensures high expression of heterologous pathway enzymes in the host chassis. | Critical for metabolic engineering; tools like Gene Designer can be used for optimization [26]. |

| Modular Cloning System (e.g., SyneBrick) | Standardized assembly of genetic circuits for predictable expression. | Allows for rapid, reproducible strain construction by integrating parts at defined neutral sites [26]. |

| Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems | Enables programmed communication and coordination between different strains in a consortium. | Used to build synthetic ecological interactions like mutualism and predator-prey dynamics [28]. |

| Synchronized Lysis Circuit (SLC) | A synthetic gene circuit for programmed population control. | Prevents overgrowth of any single strain, maintaining consortium stability via negative feedback [28]. |

| Cdk4/6-IN-9 | Cdk4/6-IN-9, MF:C22H23FN8, MW:418.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Aculene A | Aculene A, MF:C19H25NO3, MW:315.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: CRISPRi Workflow for Consortium Metabolic Engineering

Diagram 2: CRISPRi-TnSeq for Genetic Interaction Mapping

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers employing CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) to fine-tune metabolic pathways for improved xylitol production. The content is framed within a broader thesis on using CRISPRi for metabolic engineering, focusing on a case study where growth and production are decoupled in E. coli to enhance yields [33]. The following sections address specific experimental challenges through troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed protocols.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Editing Efficiency in Host Strain Engineering

Issue: Low efficiency when creating knockout host strains (e.g., focA-pflB; ldhA; adhE; frdA; xylAB).

Solutions:

- Verify gRNA Design: Ensure your guide RNA (gRNA) sequence is highly specific and unique to the genomic target. Use online prediction tools to minimize off-target effects [20].

- Optimize Delivery Method: Different cell types may require optimized delivery strategies for CRISPR components. Test electroporation, lipofection, or viral vectors to identify the most efficient method for your specific bacterial strain [20].

- Confirm Cas9 Expression: Use a promoter that drives strong, consistent expression of Cas9 in your host organism. Verify the quality and concentration of your plasmid DNA or mRNA to prevent degradation [20].

- Employ High-Fidelity Cas Variants: To reduce off-target cleavage, use high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) [34] [20].

Problem 2: Ineffective Metabolic Switch via CRISPRi

Issue: Repression of cydA (cytochrome BD-I) does not lead to consistent growth arrest, or cells escape arrest prematurely.

Solutions:

- Check dCas9 and gRNA Expression: Confirm that the anhydrotetracycline-inducible promoter is functioning correctly and that both dCas9 and the gRNA targeting

cydAare expressed at sufficient levels [33]. - Validate Growth Medium: The richness of the media can impact the effectiveness of growth arrest. The growth arrest was shown to be more effective and stable in minimal media compared to richer media (e.g., minimal media with 0.5% yeast extract) [33].

- Test Reversibility: If studying reversible arrest, ensure inducer removal is complete via a thorough washing step. The growth arrest has been demonstrated to be reversible upon removal of the inducer [33].

- Assess Long-Term Stability: Monitor the culture over an extended period (e.g., >30 hours). The CRISPRi-mediated growth arrest was shown to be stable for over 96 hours with no escapees [33].

Problem 3: Low Xylitol Yields

Issue: The xylitol yield is below the theoretical maximum after a successful metabolic switch.

Solutions:

- Ensure Anaerobic Physiology: Verify that the metabolic switch to anaerobic physiology under oxic conditions is complete. A successful switch should decouple growth from production, directing resources toward xylitol synthesis [33].

- Check Cofactor Regeneration: The conversion of xylose to xylitol by xylose reductase requires NADPH. Ensure an adequate NADPH supply is available through the pentose phosphate pathway [35] [36].

- Delete Xylitol-Assimilating Genes: In yeast systems, delete endogenous genes responsible for xylitol assimilation (e.g.,

XYL2,SOR1,SOR2,XKS1) to prevent re-consumption of the product [37]. - Quantify By-products: Monitor acetate levels, as it can accumulate and inhibit growth and production. The referenced study designed a co-culture where a second strain consumed the excreted acetate [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why use CRISPRi instead of traditional gene knockouts for essential genes like cydA?

A1: Traditional knockout of essential genes is lethal. CRISPRi allows for tunable, conditional repression of such genes, enabling precise control over metabolism without causing cell death. This facilitates a metabolic switch from growth to production phases [33].

Q2: How is the decoupling of growth and production beneficial for xylitol yield? A2: Decoupling allows cells to utilize resources primarily for product synthesis rather than biomass accumulation. In the case study, this strategy led to a significant increase in the molar yield of xylitol per glucose consumed, achieving up to 3.5 in minimal media under induced conditions compared to 1.9 in uninduced, growing cells [33].

Q3: What strategies can be used to manage inhibitory by-products like acetate? A3: A syntrophic consortium approach can be employed. Engineered partner strains can be designed for co-valorization of by-products. For example, an acetate-auxotrophic E. coli strain was engineered to consume acetate produced by the xylitol producer, converting it into a secondary product like isobutyric acid [33].

Q4: Are there alternative microbial hosts for metabolic engineering of xylitol? A4: Yes, besides E. coli, successful xylitol production has been demonstrated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [37] [38] and Pichia pastoris [39]. Yeasts are often preferred for their natural ability to handle industrial fermentation conditions and cofactor balance for xylose reductase [35] [36].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Experiment: CRISPRi-Mediated Metabolic Switch and Xylitol Production

Objective: To induce anaerobic metabolism under oxic conditions in a engineered E. coli strain for growth-decoupled xylitol production.

Methodology Summary:

- Strain Construction:

- Create a base strain with knockouts in native fermentation pathways (

focA-pflB; ldhA; adhE; frdA) and xylose catabolism (xylAB). - Integrate a xylose reductase gene (e.g., from Candida boidinii).

- Integrate dCas9 under an inducible promoter (e.g., anhydrotetracycline).

- Introduce a plasmid with gRNA targeting the essential gene

cydA(cytochrome BD-I) [33].

- Create a base strain with knockouts in native fermentation pathways (

Fermentation Protocol:

- Inoculate the engineered strain in a suitable bioreactor with oxic conditions.

- Allow initial growth phase.

- Induce CRISPRi system by adding anhydrotetracycline to repress

cydA. - Monitor OD600 (growth) and sample periodically for HPLC analysis of xylitol, glucose, and by-products like acetate [33].

Analytical Methods:

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from the case study and related research.

Table 1: Comparative Xylitol Production Data from Engineered Microbes

| Microbial Host | Engineering Strategy | Carbon Source | Xylitol Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g substrate) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli [33] | CRISPRi of cydA to decouple growth |

Glucose + Xylose | N/R | 3.5 mol/mol (Glucose) | Effective metabolic switch under oxic conditions |

| S. cerevisiae [37] | Deletion of XKS1 |

Glucose + Xylose | 46.17 | 0.92 g/g (xylose) | Blocking assimilation increases yield in SSF |

| P. pastoris [39] | Dual pathway + NADPH-XDH | Glucose | 2.8 | 0.14 g/g | Record yield from glucose in yeast |

| P. pastoris [39] | Dual pathway + NADPH-XDH | Glycerol | 7.0 | 0.35 g/g | High yield from sustainable feedstock |

N/R: Not explicitly reported in the provided excerpt.

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

Metabolic Pathway for Xylitol Production

Diagram Title: Engineered Xylitol Biosynthesis and Assimilation Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Consortium Fermentation

Diagram Title: Single-Bioreactor Consortium Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for CRISPRi-Mediated Xylitol Production

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression System | CRISPRi effector; binds DNA without cutting | Integrated into genome under anhydrotetracycline-inducible promoter [33] |

| gRNA Plasmid | Targets dCas9 to specific gene sequence | Plasmid with gRNA targeting cydA for metabolic switch [33] |

| Engineered E. coli Strain | Production host | Base strain with knockouts in fermentation genes (focA-pflB, ldhA, adhE, frdA, xylAB) and integrated xylose reductase [33] |

| Anhydrotetracycline (aTc) | Inducer for dCas9/gRNA expression | Triggers the metabolic switch from growth to production [33] |

| Xylose Reductase (XR) | Key enzyme for xylitol production | From Candida boidinii; converts xylose to xylitol using NADPH [33] [35] |

| HPLC with RID | Metabolite quantification | Quantifies xylitol, glucose, acetate; Aminex HPX-87H column recommended [39] |

| Acetate-Auxotrophic Partner Strain | By-product valorization | Engineered E. coli (e.g., ΔaceEF, ΔfocA-pflB, ΔpoxB) to consume acetate [33] |

| AChE-IN-14 | AChE-IN-14, MF:C28H35NO3, MW:433.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| t-Boc-N-amido-PEG10-Br | t-Boc-N-amido-PEG10-Br, MF:C27H54BrNO12, MW:664.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Multiplexed CRISPRi for Rewiring Complex Metabolic Networks

Multiplexed CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) represents a revolutionary approach for systematically rewiring complex metabolic networks in microbial and mammalian systems. This technology enables the simultaneous, targeted repression of multiple genes using a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) protein fused to repressor domains, which binds to DNA without cleaving it and blocks transcription [2]. For metabolic engineers, this provides an unparalleled toolset for fine-tuning metabolic pathways, eliminating functional redundancies, and redirecting cellular resources toward the production of valuable compounds without creating lethal mutations [40] [41].

The application of multiplexed CRISPRi addresses a fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering: complex metabolic pathways often involve numerous genes with overlapping functions, where single-gene perturbations rarely yield optimal results [42] [41]. By enabling coordinated repression of multiple pathway components, CRISPRi allows researchers to create balanced metabolic fluxes that maximize product yields while maintaining cellular viability. This technical framework has successfully enhanced production of diverse compounds, including violacein in E. coli [40] and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in tomatoes [42], demonstrating its broad applicability across biological systems.

Technical Foundations: CRISPRi Systems and Mechanisms

Core Molecular Components

The CRISPRi system requires two fundamental components for targeted gene repression:

- dCas9-Repressor Fusion Protein: A nuclease-deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) serves as a programmable DNA-binding scaffold. When fused to repressor domains such as SALL1-SDS3 (proprietary repressors that outperform traditional KRAB domains) or the engineered cAMP receptor protein (CRP) in bacterial systems, it blocks transcription initiation or elongation [2] [40].

- Guide RNA (gRNA) Arrays: Single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) direct the dCas9-repressor complex to specific DNA sequences. For multiplexed applications, multiple gRNAs are expressed as arrays and processed into individual functional units [43].

Table: Key CRISPRi System Components and Their Functions

| Component | Type/Variant | Function | Optimal Targeting |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Repressor | dCas9-SALL1-SDS3 | Eukaryotic transcriptional repression [2] | - |

| dCas9 Repressor | dxCas9-CRP | Bacterial activation/repression [40] | - |

| Guide RNA | CRISPRi sgRNA | Targets dCas9 to specific genomic loci [2] | 0-300 bp downstream of TSS [2] |

| Processing Enzyme | Cas12a, Csy4, tRNA | Processes gRNA arrays into individual units [43] | - |

Mechanisms of Transcriptional Repression

CRISPRi mediates gene repression through several mechanisms depending on the targeting location:

- Transcription Initiation Blockade: When the dCas9-repressor complex binds near the transcription start site (TSS), typically within 0-300 base pairs downstream, it physically prevents RNA polymerase from initiating transcription [2]. This is the most effective approach for strong gene repression.

- Transcription Elongation Interference: Binding within the coding sequence can obstruct progressing RNA polymerase, leading to premature transcription termination [43].

- Chromatin Remodeling: In eukaryotic systems, repressor domains like SALL1-SDS3 recruit proteins involved in chromatin modification, creating a transcriptionally silent environment around the target locus [2].

Figure 1: CRISPRi Mechanism of Transcription Blockade at Transcription Start Site

Implementing Multiplexed CRISPRi: Experimental Workflows

gRNA Library Design and Assembly

Designing effective gRNA libraries is a critical first step in multiplexed CRISPRi experiments. For metabolic engineering applications, the process typically involves:

- Target Identification: Computational analysis of metabolic networks to identify key flux-control points, competing pathways, and regulatory nodes that influence product yield [40].

- gRNA Design: Using algorithms (e.g., CRISPRi v2.1) to design highly specific gRNAs targeting regions 0-300 bp downstream of the TSS of selected genes [2].

Array Assembly: gRNAs are assembled into arrays using various methods:

- Golden Gate Assembly: Efficiently combines multiple gRNA expression cassettes using type IIS restriction enzymes [40].

- Randomized Self-Assembly: Creates diverse CRISPR arrays from oligonucleotide pairs (R-S-Rs: repeat-spacer-repeat) for unbiased combinatorial screening [41] [44].

- tRNA-gRNA Systems: Exploits endogenous tRNA processing machinery (RNase P and Z) to cleave gRNA arrays into individual functional units [43].

Figure 2: gRNA Library Design and Assembly Workflow

System Delivery and Validation

Successful implementation requires efficient delivery of CRISPRi components and validation of their function:

- Delivery Methods: For prokaryotic systems, plasmid transformation is standard, with inducible promoters (e.g., rhamnose-inducible PrhaBAD) controlling dCas9 expression to minimize fitness costs [40]. For mammalian cells, lentiviral transduction enables stable integration of both dCas9 and gRNA arrays [45].

- Validation Techniques:

- qPCR: Measures transcript levels of target genes to confirm knockdown efficiency (expect ≥2-fold repression for most targets) [41].

- Phenotypic Screening: Tracks changes in metabolic output (e.g., violacein or GABA production) or growth characteristics under selective conditions [40] [42].

- Single-Cell RNA-seq: Provides high-resolution analysis of perturbation effects across individual cells in heterogeneous populations [45].

Table: Troubleshooting Common Multiplexed CRISPRi Implementation Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Repression Efficiency | Suboptimal gRNA design, Incorrect dCas9 localization, Inadequate repressor domain | Redesign gRNAs targeting 0-300bp past TSS [2], Verify dCas9 nuclear localization (eukaryotes), Test alternative repressor domains (SALL1-SDS3 vs KRAB) [2] |

| Cellular Toxicity | dCas9 overexpression, Off-target effects, Essential gene repression | Use inducible dCas9 expression system [40], Include non-targeting gRNA controls, Titrate repressor expression to minimal effective level |

| Incomplete Processing of gRNA Arrays | Inefficient processing enzymes, Poor array design | Co-express appropriate processing enzymes (Csy4, RNase III) [43], Incorporate self-cleaving ribozymes or tRNA spacers between gRNAs [43] |

| Variable Repression Across Targets | Chromatin accessibility differences, gRNA sequence efficiency variations | Use chromatin-modulating domains (SALL1-SDS3) [2], Employ pooled gRNAs (3-5 per gene) to enhance repression [2] |

| Library Representation Bias | Unequal gRNA amplification, Selective cellular fitness effects | Use randomized array assembly (MuRCiS approach) [41], Include control gRNAs for normalization, Implement PacBio long-read sequencing for accurate array analysis [41] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Multiplexed CRISPRi Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Repressor Systems | dCas9-SALL1-SDS3 [2], dxCas9-CRP [40] | Eukaryotic vs. bacterial applications; CRP enables dual activation/repression in bacteria |

| gRNA Expression Systems | psgRNA plasmid [40], Perturb-seq vector [45] | Constitutive or inducible gRNA expression; specialized vectors for single-cell analyses |

| Array Processing Systems | tRNA-gRNA arrays [43], Csy4 processing system [43] | Efficient liberation of individual gRNAs from polycistronic transcripts |

| Delivery Tools | Lentiviral particles [2], Plasmid transformation [40] | Stable integration vs. transient expression requirements |

| Validation Assays | qPCR primers [41], Single-cell RNA-seq [45] | Knockdown efficiency verification; high-resolution phenotypic screening |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What distinguishes CRISPRi from traditional CRISPR knockout approaches in metabolic engineering?

CRISPRi enables temporary, tunable gene knockdown without permanent DNA damage, making it ideal for studying essential genes and achieving balanced metabolic states. Unlike knockout approaches that eliminate gene function completely, CRISPRi allows fine-scale modulation of gene expression levels, which is often necessary for optimizing metabolic fluxes without compromising cell viability [2].

Q2: How many genes can be simultaneously targeted with multiplexed CRISPRi systems?

Current systems successfully target up to ten genes simultaneously in bacterial systems [41], with some studies demonstrating repression of even larger gene sets. The practical limit depends on the delivery system, processing efficiency, and cellular tolerance. For comprehensive metabolic engineering, researchers often employ library approaches where different cells receive different gRNA combinations, enabling screening of thousands of potential multiplexed perturbations [40] [41].

Q3: What strategies improve repression efficiency when targeting multiple genes?

- Pooled gRNAs: Use 3-5 gRNAs per gene target to enhance repression [2].

- Optimized targeting: Position gRNAs within 0-300 bp downstream of the transcription start site [2].

- Advanced repressor domains: Utilize SALL1-SDS3 instead of KRAB for enhanced repression in eukaryotic systems [2].

- Validated array processing: Implement efficient processing systems (tRNA, Csy4) to ensure all gRNAs in arrays are functional [43].

Q4: How can I identify synthetic lethal gene combinations in metabolic pathways?

The MuRCiS (multiplex, randomized CRISPR interference sequencing) approach enables unbiased identification of critical gene combinations. This method uses randomized self-assembly of CRISPR arrays from oligonucleotide pools, creating diverse gRNA combinations that can be screened for fitness defects or metabolic phenotypes. Combined with PacBio long-read sequencing, this allows comprehensive interrogation of pairwise or higher-order gene interactions [41] [44].

Q5: What controls are essential for validating multiplexed CRISPRi experiments?

- Non-targeting gRNAs: Control for non-specific effects of dCas9 binding and cellular responses [40].

- Essential gene targeting: Validate system functionality by repressing known essential genes and monitoring fitness defects [41].

- Single-gRNA controls: Compare multiplex effects with individual gene repressions [42].

- Expression verification: Use qPCR to confirm target gene knockdown and rule off-target effects [41].

Genome-Scale CRISPRi Screens for Functional Genomics and Target Identification

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the recommended sequencing depth for a genome-scale CRISPRi screen? For a genome-scale CRISPRi screen, it is generally recommended that each sample achieves a sequencing depth of at least 200x [1]. The required data volume can be estimated using the formula: Required Data Volume = Sequencing Depth × Library Coverage × Number of sgRNAs / Mapping Rate [1]. For a typical human whole-genome library, this often translates to approximately 10 Gb of sequencing per sample [1].

Q2: How can I determine if my CRISPRi screen was successful? The most reliable method is to include well-validated positive-control genes and their corresponding sgRNAs in your library [1]. If these controls show significant enrichment or depletion in the expected direction, it strongly indicates effective screening conditions. In the absence of known targets, you can evaluate performance by assessing the cellular response (e.g., degree of cell killing under selection) and examining bioinformatic outputs like the distribution and log-fold change of sgRNA abundance [1].

Q3: Why do different sgRNAs targeting the same gene show variable performance? Gene editing efficiency is highly influenced by the intrinsic properties of each sgRNA sequence [1]. Consequently, different sgRNAs for the same gene can exhibit substantial variability, with some showing little to no activity. To enhance result reliability, it is recommended to design at least 3–4 sgRNAs per gene to mitigate the impact of individual sgRNA performance variability [1].

Q4: What are the most commonly used tools for CRISPR screen data analysis? MAGeCK (Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout) is one of the most widely used tools [1] [46]. It incorporates two primary statistical algorithms: RRA (Robust Rank Aggregation), well-suited for single treatment and control group comparisons, and MLE (Maximum Likelihood Estimation), which supports joint analysis of multiple experimental conditions [1]. A comparison of analysis tools is provided in the table below.

Q5: If no significant gene enrichment is observed, is this a statistical problem? Typically, the absence of significant enrichment is less likely due to statistical errors and more commonly results from insufficient selection pressure during the screening process [1]. When selection pressure is too low, the experimental group may fail to exhibit the intended phenotype, weakening the signal-to-noise ratio. This can often be addressed by increasing the selection pressure and/or extending the screening duration [1].

Q6: What is the difference between negative and positive screening in CRISPRi?

- Negative Screening: Applies relatively mild selection pressure, leading to the death of only a small subset of cells. The goal is to identify loss-of-function target genes whose knockout causes cell death or reduced viability, detected by the depletion of corresponding sgRNAs in the surviving population [1].

- Positive Screening: Involves strong selection pressure, resulting in the death of most cells, with only a small number surviving due to resistance or adaptation. The focus is on identifying genes whose disruption confers a selective advantage, detected by the enrichment of sgRNAs in the surviving cells [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Mapping Rate in Sequencing Data

Problem: A low percentage of sequencing reads successfully align to the sgRNA reference library. Explanation: A low mapping rate itself typically does not compromise result reliability, as downstream analysis focuses solely on successfully mapped reads [1]. Solution: Ensure the absolute number of mapped reads is sufficient to maintain the recommended sequencing depth (≥200x). Insufficient data volume, not the low mapping rate percentage, is more likely to reduce accuracy [1].

Issue: Substantial Loss of sgRNAs from the Library

Problem: Sequencing results show a large number of sgRNAs are missing from the sample. Explanation & Solution:

- If the sample is from the CRISPR library cell pool prior to screening, substantial sgRNA loss indicates insufficient initial sgRNA representation. The library cell pool should be re-established with adequate coverage [1].

- If sgRNA loss occurs in the experimental group after screening, it may reflect excessive selection pressure [1].

Issue: High False Positive/Negative Rate in FACS-Based Screens

Problem: Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) screens yield many incorrect hits. Explanation: FACS-based screening often allows for only a single round of enrichment and is susceptible to technical noise from cell sorting and stochastic gene expression [1]. Solution: To improve robustness, increase the initial number of cells and perform multiple rounds of sorting where feasible to reduce the impact of technical noise [1].

Issue: Poor Reproducibility Between Biological Replicates

Problem: Results from different biological replicates of the same screen show low correlation. Explanation & Solution:

- If reproducibility is high (Pearson correlation coefficient >0.8), perform a combined analysis across all replicates to increase statistical power [1].