CRISPR-Cas System Classification: From Foundational Types to Therapeutic Applications in Drug Development

This comprehensive review explores the evolving classification of CRISPR-Cas systems, from foundational principles to cutting-edge applications in biomedical research.

CRISPR-Cas System Classification: From Foundational Types to Therapeutic Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the evolving classification of CRISPR-Cas systems, from foundational principles to cutting-edge applications in biomedical research. Covering the updated taxonomy of 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes, we examine the molecular mechanisms distinguishing Class 1 multi-protein complexes from Class 2 single-effector systems. The article details methodological approaches for system identification and annotation, troubleshooting common classification challenges, and comparative analysis of system functionalities. Special emphasis is placed on how this classification framework informs therapeutic development, including CRISPR screening for target validation, creation of precision disease models, and emerging clinical applications in oncology and genetic disorders, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a strategic roadmap for leveraging CRISPR diversity in therapeutic innovation.

Understanding CRISPR-Cas Diversity: An Updated Evolutionary Framework for Researchers

The systematic classification of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) systems is fundamental to advancing both basic research and applied biotechnology. This whitepaper presents an updated evolutionary classification framework, delineating the hierarchy from broad classes down to specific variants. Recent advances have expanded this classification to encompass 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes, reflecting the growing diversity of these adaptive immune systems in prokaryotes [1]. Within this structured taxonomy, we detail the molecular architectures, effector mechanisms, and functional capabilities that define each group. The integration of this classification system is critical for drug development professionals and researchers leveraging CRISPR technologies for therapeutic discovery, diagnostic applications, and precision medicine.

CRISPR-Cas systems are adaptive immune systems found in approximately 50% of sequenced bacterial genomes and nearly 90% of sequenced archaea [2]. They function through three main stages: adaptation, where spacers from invading genetic elements are incorporated into the CRISPR array; expression and processing, involving transcription of the array and maturation of CRISPR RNA (crRNA); and interference, where Cas effector complexes use crRNAs to identify and cleave foreign genetic material [3] [4].

The classification of these systems employs a polythetic approach that combines phylogenetic analysis of conserved Cas proteins with comparative genomics of gene repertoires and arrangements in CRISPR-Cas loci [3]. This multi-faceted methodology is necessary due to the absence of universal markers across all systems, rapid evolution of Cas proteins, and the extensive modularity and recombination observed in these loci [3]. The classification hierarchy organizes CRISPR-Cas systems first into two major classes based on effector complex architecture, then into types defined by their signature genes and effector mechanisms, and further into subtypes characterized by distinct gene compositions and locus organizations [1] [3].

The Updated Classification Hierarchy

High-Level Organization: Class 1 and Class 2 Systems

The fundamental division in CRISPR-Cas classification separates systems into two classes based on the architecture of their effector complexes. This distinction has practical implications for both natural function and biotechnological application.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of CRISPR Classes

| Feature | Class 1 | Class 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Effector Complex | Multi-subunit protein complexes | Single, large effector protein |

| Natural Abundance | ~90% of CRISPR loci [5] | ~10% of CRISPR loci [5] |

| Organismal Distribution | Bacteria and Archaea | Bacteria only [5] |

| Biotech Applications | Less developed for editing | Widely used in genome editing |

| Types | I, III, IV, VII [1] | II, V, VI [1] |

Class 1 systems utilize multi-protein effector complexes for crRNA processing and target interference. These systems represent approximately 90% of all identified CRISPR loci in prokaryotes and are further subdivided into types I, III, IV, and the newly characterized type VII [1] [5]. The complexity of their multi-subunit architecture has historically limited their development for biotechnology applications compared to Class 2 systems.

Class 2 systems employ a single, large effector protein for crRNA processing and target interference. Although they represent only about 10% of naturally occurring CRISPR systems and are found exclusively in bacteria [5], their simplicity has made them the foundation for most CRISPR-based biotechnologies, including the widely used Cas9 (type II) and Cas12 (type V) systems.

Classification by Types and Subtypes

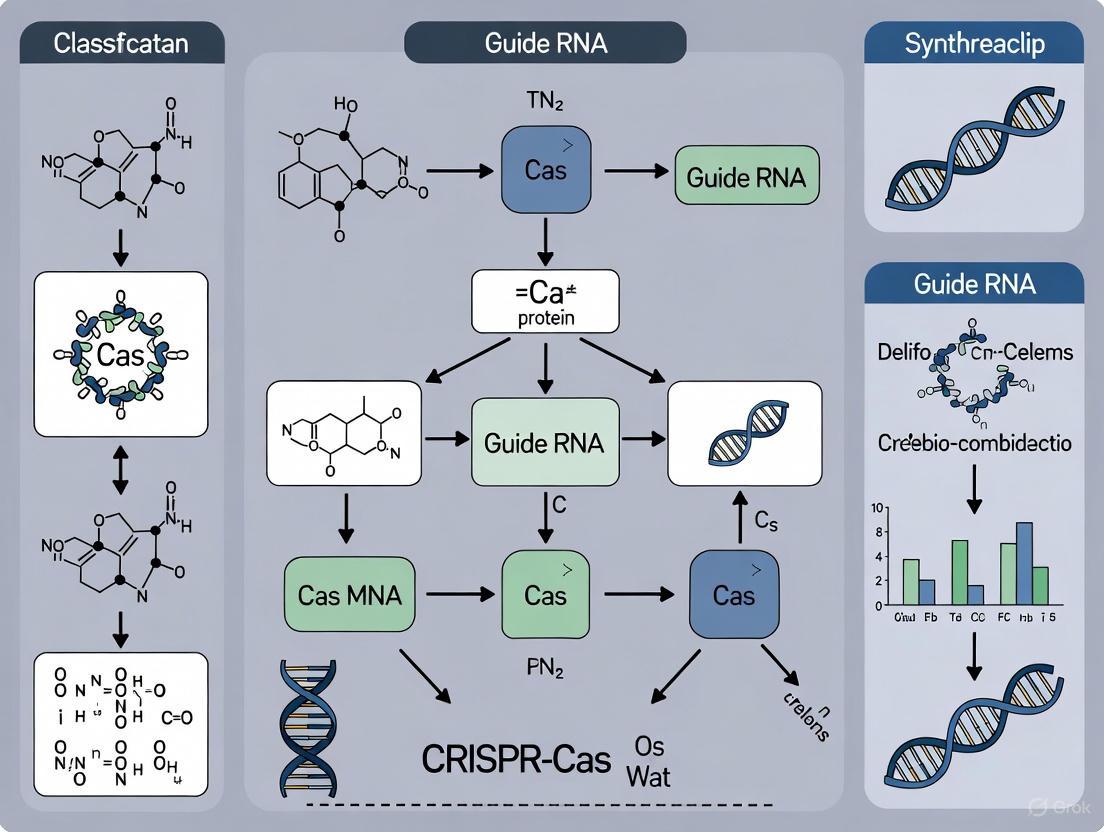

The classification hierarchy further divides each class into types based on signature genes and effector mechanisms, with each type containing multiple subtypes. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships within this classification hierarchy.

The current classification scheme has recently been expanded from 6 types and 33 subtypes to 7 types and 46 subtypes, reflecting the discovery of previously unrecognized diversity [1]. The newly added type VII represents rare systems found mostly in diverse archaeal genomes that contain a metallo-β-lactamase (β-CASP) effector nuclease, Cas14 [1].

Table 2: CRISPR-Cas Types and Their Characteristics

| Type | Signature Gene | Class | Molecular Target | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Cas3 | 1 | DNA | Features Cas3 with helicase-nuclease activity; shreds DNA [1] |

| II | Cas9 | 2 | DNA | Requires tracrRNA; uses single effector protein [4] |

| III | Cas10 | 1 | DNA/RNA | Includes polymerase/cyclase domain; can cleave both DNA and RNA [4] |

| IV | Csf1 | 1 | Unknown | Putative system; effector complex lacks cleavage domains [4] |

| V | Cas12 | 2 | DNA | Includes Cas12a (Cpf1); creates staggered DNA cuts [2] |

| VI | Cas13 | 2 | RNA | RNA-guided RNase; exhibits collateral cleavage activity [2] |

| VII | Cas14 | 1 | RNA | Newly characterized; contains β-CASP effector nuclease [1] |

Rare Variants and the "Long Tail" of CRISPR Diversity

Analysis of CRISPR-Cas variant abundance in genomes and metagenomes reveals that recently characterized systems are comparatively rare, comprising what researchers term the "long tail" of the CRISPR-Cas distribution [1]. These include type VII systems and various subtypes with unique features such as type IV variants that cleave target DNA and type V variants that inhibit target replication without cleavage [1]. The discovery of these rare variants suggests that the full diversity of CRISPR systems remains to be fully characterized and may harbor novel functionalities with potential biotechnological applications.

Experimental Characterization of CRISPR-Cas Systems

Computational Identification and Classification Workflow

The initial characterization of novel CRISPR-Cas systems employs a multi-step bioinformatics pipeline. This methodology allows researchers to identify, classify, and predict the functionality of CRISPR systems from genomic or metagenomic sequence data.

The experimental workflow begins with genomic or metagenomic data as input. The first analytical step involves CRISPR array detection using tools that identify characteristic repeat-spacer patterns [3]. Parallelly, cas gene identification employs sensitive sequence comparison tools like PSI-BLAST and HHpred to detect Cas proteins using curated profile databases such as CDD [3]. Subsequent signature gene analysis focuses on determining the system type by identifying key markers like Cas3 for type I, Cas9 for type II, or Cas10 for type III systems [3]. The locus organization examination assesses gene composition and arrangement to establish subtype characteristics, while evolutionary analysis often uses phylogenetic trees of conserved proteins like Cas1 to validate classification [3]. This integrated approach culminates in comprehensive system classification within the established hierarchy.

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Characterization

The experimental characterization of CRISPR-Cas systems requires specialized reagents and methodologies. The following table outlines essential research tools and their applications in CRISPR research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR System Characterization

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cas-Specific Antibodies | Protein detection and localization | Verify expression of Cas proteins; confirm complex formation in Class 1 systems |

| crRNA/tracrRNA Libraries | Guide RNA synthesis | Test interference functionality; determine PAM requirements |

| Plasmid Vectors for Heterologous Expression | Functional expression in model systems | Characterize systems from uncultivable organisms; test effector function |

| Phage/Plasmid Interference Assays | Functional immunity testing | Validate defense capability; assess targeting specificity |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Spacer acquisition analysis | Study adaptation events; identify natural targets through spacer analysis |

| Metagenomic Sequencing | Discovery of novel systems | Identify rare variants from environmental samples; expand diversity catalog |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutics

The structured classification of CRISPR-Cas systems directly informs their therapeutic application. Class 2 systems, particularly type II (Cas9) and type V (Cas12), have been widely adopted for gene therapy development due to their simplicity and efficiency in creating targeted DNA breaks [6] [7]. The recent characterization of rare variants opens possibilities for novel therapeutic modalities, such as type VI Cas13 systems that target RNA rather than DNA, offering potential for treating viral infections or manipulating gene expression without permanent genomic alteration [4] [2].

The diversity within the CRISPR classification hierarchy enables precision therapeutic approaches. For example, the compact size of some Cas12 variants compared to Cas9 facilitates delivery via viral vectors [7], while the collateral cleavage activity of Cas13 and certain Cas12 family members has been harnessed for highly sensitive diagnostic applications such as SARS-CoV-2 detection [4] [2]. Understanding the fundamental characteristics of each CRISPR type and subtype allows researchers to select the most appropriate system for specific therapeutic challenges, whether it involves gene disruption, base editing, gene activation, or nucleic acid detection.

As the CRISPR classification framework continues to expand with the discovery of new variants, so too does the toolkit available for addressing previously intractable diseases. The ongoing characterization of the "long tail" of CRISPR diversity promises to yield further innovations in genetic medicine, diagnostic technology, and therapeutic development in the coming years.

Class 1 CRISPR-Cas systems represent one of the two primary classes of adaptive immune mechanisms found in prokaryotes, distinguished by their reliance on multi-protein effector complexes for nucleic acid targeting and interference. These systems are fundamentally different from Class 2 systems, which utilize a single, large effector protein (such as Cas9 or Cas12) for the same function [5] [8]. The complexity of Class 1 systems has historically made them less utilized in biotechnology applications compared to their Class 2 counterparts; however, they represent the majority of naturally occurring CRISPR-Cas systems and exhibit remarkable functional diversity [8] [9].

Framed within the broader context of CRISPR-Cas classification research, understanding Class 1 systems is essential for comprehending the evolutionary history and functional spectrum of prokaryotic adaptive immunity. These systems are not only more abundant in nature but are also phylogenetically more ancient, with Type III systems particularly considered potential ancestors of all known CRISPR-Cas variants [9]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of Class 1 CRISPR-Cas systems, detailing their classification, prevalence, molecular mechanisms, and experimental characterization, with specific relevance to research and drug development applications.

Classification and Architectural Principles

Class 1 systems are currently divided into three major types (I, III, and IV) based on their signature genes and effector complex compositions, with continued discovery efforts revealing substantial diversity within these groups [1] [8].

Table 1: Classification of Class 1 CRISPR-Cas Systems

| Type | Signature Gene | Effector Complex Name | Target Nucleic Acid | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Cas3 | Cascade (CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defense) | dsDNA | Utilizes Cas3 helicase-nuclease for target degradation; most abundant CRISPR type overall [8] [9] |

| III | Cas10 | Csm (Type III-A/D) or Cmr (Type III-B/C) | ssRNA and dsDNA | Features Cas10-dependent cyclic oligoadenylate (cOA) signaling; most complex type with multi-layered immunity [1] [8] |

| IV | Csf1 | Not definitively characterized | dsDNA (putative) | Lacks adaptation modules (Cas1-Cas2); often plasmid-encoded; mechanism remains poorly understood [1] [9] |

The classification hierarchy continues to expand with ongoing research. A recent evolutionary classification published in 2025 identifies 7 types and 46 subtypes across both CRISPR classes, reflecting the rapid discovery of novel variants, particularly in the "long tail" of the CRISPR-Cas distribution—rare systems that remain to be fully characterized experimentally [1].

The architectural principle unifying all Class 1 systems is their multi-subunit effector complex, which assembles around a single CRISPR RNA (crRNA) molecule to form a RNA-guided surveillance machinery [8]. This stands in direct contrast to Class 2 systems, where a single protein (e.g., Cas9) performs all functions related to target recognition and cleavage [5]. The evolution of Class 1 systems has followed a path of increasing complexity, with recent analyses suggesting that Type VII systems (now classified as Class 1) likely evolved from Type III via reductive evolution, while maintaining the multi-subunit character definitive of Class 1 [1].

Prevalence and Ecological Distribution

Class 1 systems dominate the CRISPR landscape in prokaryotes, with approximately 90% of identified CRISPR-Cas loci in bacteria and nearly 100% in archaea belonging to this class [10] [8] [9]. This distribution reflects fundamental differences in the evolutionary pressures and defense strategies across these domains.

Table 2: Prevalence of Class 1 CRISPR-Cas Systems Across Prokaryotic Domains

| Domain | Overall CRISPR Prevalence | Class 1 Prevalence | Most Common Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ~40% of genomes [10] | ~75% of CRISPR+ genomes [10] | Type I (most abundant CRISPR type overall) [9] | Higher prevalence of alternative defense systems (e.g., restriction-modification) [10] |

| Archaea | ~90% of genomes [10] | Nearly 100% of CRISPR+ genomes [10] [9] | Type I and Type III [10] | Adaptation to extreme environments with high viral exposure; minimal restriction-modification systems [10] |

The significant prevalence of Class 1 systems, particularly in archaea, is theorized to reflect differential evolutionary pressures. Archaea, especially hyperthermophiles, may face more frequent viral attacks in their extreme environments, potentially favoring the retention of sophisticated multi-component defense systems like Class 1 CRISPR-Cas [10]. Additionally, bacteria have diversified more extensively across habitats and encountered different selective pressures, including antibiotics, which may have favored the evolution and retention of alternative defense mechanisms [10].

Notably, the presence of active CRISPR-Cas systems appears to influence horizontal gene transfer. Research on clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium revealed that the prevalence of CRISPR-Cas systems was significantly reduced in extensively drug-resistant (XDR) isolates (32%) compared to multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates (68%) [11]. This inverse correlation between CRISPR-Cas presence and antibiotic resistance genes supports the hypothesis that these systems act as barriers to the acquisition of foreign DNA, including resistance determinants [11] [10].

Molecular Architecture and Mechanisms

Effector Complex Assembly and crRNA Biogenesis

Class 1 effector complexes share a common architectural principle: multiple Cas protein subunits assemble around a single crRNA molecule to form the functional surveillance complex [8]. Despite this common principle, there is considerable variation in the specific composition and structure across different types.

Type I systems typically form Cascade (CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defense) complexes with a characteristic "seahorse-like" architecture [8]. These complexes generally contain:

- Cas8: The large subunit that facilitates PAM recognition [8]

- Cas11: The small subunit that forms a "belly" filament [8]

- Cas7: Forms a helical backbone that polymerizes along the crRNA spacer region [8]

- Cas5: Binds the 5' end of the crRNA ("foot") [8]

- Cas6: Binds the 3' end of the crRNA ("head") and processes pre-crRNA [8]

Type III systems utilize Csm (for subtypes III-A/D/E/F) or Cmr (for subtypes III-B/C) complexes that adopt a more extended, "wormlike" shape [8]. These complexes feature:

- Cas10 as the large subunit, replacing Cas8 [8]

- Specialized Cas7-like subunits (Csm5 in Type III-A; Cmr1 and Cmr6 in Type III-B) that cap the 3' end of the crRNA, replacing Cas6 [8]

- Similar Cas5 and Cas11 homologs arranged in comparable positions [8]

The crRNA biogenesis pathway in Class 1 systems typically involves Cas6-mediated processing of the pre-crRNA transcript, except in certain Type III systems that utilize host nucleases like polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNP) or RNase E for crRNA maturation [8].

Interference Mechanisms

Type I systems target double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) through a collaborative mechanism between the Cascade complex and the Cas3 protein. After Cascade recognizes and binds to a PAM-adjacent target sequence, it recruits Cas3, which possesses both helicase and nuclease activities. Cas3 processively unwinds and degrades the target DNA, leading to extensive destruction of the invading genetic element [8] [9].

Type III systems employ a more complex interference strategy with unique features:

- Dual targeting: These systems primarily target single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) through the intrinsic RNase activity of the Cas7 subunits in the effector complex [8] [9]

- Collateral DNase activity: Target RNA binding allosterically activates the Cas10 subunit, which cleaves DNA non-specifically in the local environment [8]

- Cyclic oligoadenylate (cOA) signaling: Cas10 synthesizes cOA second messengers that activate ancillary nucleases (Csm6/Csx1), creating an amplified antiviral response through non-specific RNA degradation [8]

The recently identified Type VII systems, now classified as Class 1, employ Cas14 as their signature effector—a β-CASP family nuclease that targets RNA in a crRNA-dependent manner [1]. Type VII loci typically lack adaptation modules and their associated CRISPR arrays often contain multiple substitutions, suggesting reduced frequency of new spacer acquisition [1].

Experimental Analysis and Methodologies

Identification and Characterization Protocols

The experimental characterization of Class 1 CRISPR-Cas systems in clinical or environmental isolates involves a multi-step process that combines phenotypic assays with genomic analyses:

Sample Collection and Strain Identification

- Clinical isolates are collected from various infection sites (e.g., urinary tract, blood, wound) and identified using conventional bacteriology tests and species-specific PCR [11]

- For genomic studies, fully assembled genomes are preferred, with one representative genome per species to avoid redundancy [10]

CRISPR-Cas System Detection

- CRISPR arrays are identified using tools like CRISPRFinder, with default parameters set for repeat length (23-55 bp), gap size between repeats (25-60 bp), and allowing up to 20% nucleotide mismatch between repeats [10]

- CRISPR arrays are validated based on evidence levels (1-4), with levels 2-4 requiring repeat and spacer similarity, while level 1 includes small CRISPRs with 3 or fewer spacers [10]

- cas genes are identified by analyzing open reading frames (ORFs) using Prodigal, followed by homology searches using MacSyFinder with Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) of known CAS proteins [10]

- Alternative methods include BLAST searches of sequences flanking CRISPR loci and TIGRFAM annotations [10]

- CRISPR-Cas subtype determination employs specialized tools like CRISPRCasFinder [10]

Phenotypic and Genotypic Correlation Analysis

- Antibiotic resistance profiles are determined through phenotypic susceptibility testing [11]

- Association between CRISPR-Cas presence and resistance/virulence genes is analyzed using statistical methods (e.g., significance testing with P=0.0001 threshold) [11]

- Phylogenetic analysis of conserved Cas proteins (e.g., Cas1) is performed using UPGMA method with MUSCLE algorithm and MEGA software [10]

- Conservation analysis of effector genes (e.g., csn1) employs structural and sequence comparison to identify potential mutations and their functional impact [11]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Class 1 CRISPR-Cas Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | CRISPRFinder v1.1.2 [10], CRISPRCasFinder [10], MacSyFinder [10] | Identification of CRISPR arrays and cas genes | In silico analysis of genomic sequences |

| Sequence Analysis Software | Prodigal v2.6.3 (ORF finding) [10], BLAST v2.15.0 [10], HHpred [10] | Gene annotation and homology searches | cas gene identification and classification |

| PCR Components | Species-specific primers [11], conventional bacteriology test reagents [11] | Strain identification and CRISPR array screening | Experimental validation in clinical isolates |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Tools | MUSCLE algorithm v3 [10], MEGA v12 [10], Clustal X v2.1 [10] | Multiple sequence alignment and evolutionary analysis | Conservation studies of Cas proteins |

| Structural Analysis Resources | CDD database profiles [3], DALI structural comparison [1] | Protein domain identification and structure-function relationships | Conservation analysis of effector complexes |

Research Applications and Therapeutic Potential

While Class 1 systems have been less exploited biotechnologically than Class 2 systems due to their multi-component nature, recent advances have revealed several promising applications:

Type I Systems for Large-Scale Genomic Deletions The processive DNA degradation activity of Cas3 makes Type I systems particularly suitable for creating large genomic deletions, a challenging task with standard Cas9-based systems [9]. Additionally, engineered Type I systems lacking Cas3 have been repurposed as CRISPR transposases, enabling precise insertion of large DNA fragments [9].

Type III Systems for RNA Targeting and Editing The RNA-targeting capability of Type III systems presents opportunities for transcriptome engineering. Notably, the Type III-E effector Cas7-11 (a single protein derived from a natural fusion of multiple Cas7 subunits and Cas11) has been developed as a RNA editing tool for mammalian cells, combining the multi-subunit heritage of Class 1 with the practical simplicity of Class 2 systems [9].

Modulation of Horizontal Gene Transfer The correlation between CRISPR-Cas presence and reduced antibiotic resistance gene acquisition [11] [10] suggests potential applications in controlling the spread of antimicrobial resistance. Strategic manipulation of Class 1 systems could potentially restore bacterial susceptibility to conventional antibiotics in clinical settings.

Diagnostic Applications Components of Class 1 systems, particularly the cOA signaling pathway of Type III systems, offer potential for developing novel diagnostic platforms analogous to the SHERLOCK and DETECTR systems based on Class 2 effectors [8]. The signal amplification inherent in cOA signaling could provide enhanced sensitivity for pathogen detection.

Class 1 CRISPR-Cas systems, with their multi-subunit effector complexes, represent the most abundant and evolutionarily ancient form of prokaryotic adaptive immunity. Their prevalence across bacterial and archaeal domains, particularly the near-universal presence in archaea, underscores their fundamental role in prokaryotic defense strategies. The complex architecture of these systems—ranging from the DNA-targeting Cascade complexes of Type I to the multi-layered immunity of Type III—provides a rich repertoire of molecular mechanisms that continue to inform our understanding of host-virus coevolution.

While practical applications of Class 1 systems have lagged behind those of Class 2, largely due to the challenges of engineering multi-component complexes, recent advances demonstrate their significant potential for large-scale genomic deletions, RNA editing, and controlling horizontal gene transfer. As our knowledge of Class 1 system diversity continues to expand, particularly through the characterization of rare variants from the "long tail" of CRISPR-Cas distribution, new opportunities will likely emerge for harnessing these sophisticated immune systems in biotechnology and therapeutic development.

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins constitute adaptive immune systems in bacteria and archaea, protecting hosts from mobile genetic elements. The classification of these systems is foundational for understanding their biology and harnessing their capabilities. CRISPR-Cas systems are broadly divided into two classes based on the architecture of their effector complexes. Class 1 systems (encompassing Types I, III, and IV) utilize multi-protein effector complexes for target interference, while Class 2 systems (encompassing Types II, V, and VI) employ single, large effector proteins for the same purpose [12] [5].

This classification is dynamic, reflecting ongoing discovery. A recent update to the evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems highlights the rapid expansion of this field, now encompassing 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes, a significant increase from the 6 types and 33 subtypes defined five years ago [1] [13]. While this update includes the characterization of rare variants, particularly in Class 1 systems, it underscores the biotechnological prominence of Class 2 systems. Class 2 systems are less common in nature than Class 1 systems, found in only about 10% of CRISPR-containing prokaryotes, yet their simplicity has made them the engine of the genome editing revolution [5] [14]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to Class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems, detailing their molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and transformative impact on biotechnology and therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Class 2 Effectors

Class 2 systems are defined by a single effector protein that performs crRNA-guided cleavage of nucleic acid targets. The fundamental mechanism involves three phases: adaptation, expression, and interference. During adaptation, Cas1 and Cas2 proteins integrate fragments of foreign DNA (protospacers) into the host CRISPR array as new spacers. In the expression phase, the CRISPR array is transcribed and processed into mature CRISPR RNA (crRNA). Finally, in the interference phase, the single effector protein complexed with the crRNA scans the cell for matching foreign nucleic acids and cleaves them [15] [16].

The core functional modules of a Class 2 effector protein include a recognition lobe for binding the guide RNA and target, and a nuclease lobe containing the catalytic domains. Target recognition is governed by complementary base pairing between the crRNA spacer and the target DNA or RNA, and is contingent upon the presence of a short protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence in the target, which varies by effector type and subtype [12] [14].

Type II: The Cas9 System

Type II systems, featuring the hallmark effector Cas9, were the first Class 2 systems to be repurposed for genome engineering. Cas9 is a dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease. Its activity requires both a crRNA, which provides target specificity, and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), which is essential for crRNA maturation and Cas9 function [15] [14]. For biotechnological applications, the crRNA and tracrRNA are often fused into a single guide RNA (sgRNA) [12].

Cas9 cleaves double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) through two distinct nuclease domains: the HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the crRNA (target strand), while the RuvC-like domain cleaves the non-complementary strand (non-target strand) [14]. This results in a double-strand break (DSB) that generates blunt ends or ends with short overhangs. The PAM sequence for the canonical Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) is 5'-NGG-3', which is located directly adjacent to the target sequence on the non-complementary strand [12].

Type V: The Cas12 System

Type V systems are characterized by effectors such as Cas12a (Cpf1), Cas12b, and others. Cas12 proteins are generally characterized by a single RuvC-like nuclease domain responsible for cleaving both strands of dsDNA [15]. Unlike Cas9, Cas12a does not require a tracrRNA for its function and can process its own pre-crRNA into mature crRNAs, enabling multiplexed genome editing from a single transcript [15] [14].

A unique functional property of many Cas12 effectors is their trans- or collateral cleavage activity. Upon binding and cleaving its target dsDNA (the cis-activity), Cas12a undergoes a conformational change that activates non-specific single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) cleavage (trans-activity) [14]. This property has been leveraged for sensitive diagnostic tools. Cas12 effectors typically recognize T-rich PAM sequences (e.g., 5'-TTTN-3' for Cas12a) and generate staggered DNA ends with 5' overhangs, unlike the blunt ends typically produced by Cas9 [15] [12].

Type VI: The Cas13 System

Type VI systems deploy Cas13 effectors (e.g., Cas13a, Cas13b, Cas13d) that target single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) rather than DNA. Cas13 proteins contain two Higher Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes Nucleotide-binding (HEPN) domains that mediate RNA cleavage [15] [12].

Similar to Cas12, Cas13 exhibits collateral RNase activity upon target RNA recognition. This nonspecific RNA degradation has been harnessed for powerful nucleic acid detection platforms like SHERLOCK [5]. Cas13's targeting requires a protospacer flanking site (PFS) rather than a PAM, which influences its specificity [15].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Effectors

| Feature | Type II (Cas9) | Type V (Cas12a/Cpf1) | Type VI (Cas13a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Nucleic Acid | dsDNA | dsDNA | ssRNA |

| Nuclease Domains | RuvC & HNH | Single RuvC | 2 x HEPN |

| Guide RNA | crRNA + tracrRNA (or sgRNA) | crRNA only | crRNA only |

| crRNA Processing | Requires tracrRNA/RNase III | Self-processes pre-crRNA | Self-processes pre-crRNA |

| PAM/PFS Sequence | 3' NGG (for SpCas9) | 5' TTTN (for Cas12a) | 3' PFS: non-G |

| Cleavage Products | Blunt ends | Staggered ends (5' overhangs) | RNA cleavage |

| Collateral Activity | No | Yes (ssDNA cleavage) | Yes (ssRNA cleavage) |

| Key Applications | Gene knockout, knock-in | Gene editing, DNA diagnostics | RNA knockdown, RNA diagnostics |

Figure 1: Classification and Key Characteristics of Major Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Systems. The diagram outlines the three primary types, their signature effectors, target requirements, and primary biotechnological applications.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The application of Class 2 systems in research and therapy relies on robust experimental protocols. Below is a detailed methodology for a typical genome-editing experiment using the CRISPR-Cas9 system in mammalian cells.

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout in Mammalian Cells

Principle: The Cas9 nuclease, guided by a target-specific sgRNA, induces a site-specific DSB in the genomic DNA. The cell's repair via the error-prone NHEJ pathway results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the target gene's function [12].

Workflow:

sgRNA Design and Synthesis:

- Design: Identify a 20-nucleotide target sequence immediately 5' to a PAM (NGG for SpCas9) within the exon of the target gene. Use computational tools (e.g., CRISPOR, ChopChop) to minimize potential off-target effects by assessing sequence uniqueness.

- Synthesis: Chemically synthesize the sgRNA oligonucleotide or clone it into a plasmid expression vector (e.g., pX330 or similar) under a U6 or other RNA Polymerase III promoter.

Delivery of CRISPR Components:

- Plasmid Transfection: For most cell lines, co-transfect a plasmid expressing Cas9 with a plasmid expressing the sgRNA using a suitable method (e.g., lipofection, electroporation).

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Transfection: For higher efficiency and reduced off-target effects, complex purified recombinant Cas9 protein with in vitro transcribed sgRNA to form an RNP complex, and deliver it via electroporation.

Validation of Editing Efficiency:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection and extract genomic DNA.

- T7 Endonuclease I Assay: PCR-amplify the target genomic region. Denature and reanneal the PCR products. Heteroduplex DNA formed from wild-type and mutant alleles is cleaved by T7E1 enzyme, which is visualized by gel electrophoresis.

- Sanger Sequencing and TIDE Analysis: Sanger sequence the PCR-amplified target region. Analyze the sequencing chromatograms using tools like TIDE (Tracking of Indels by DEcomposition) to quantify the spectrum and frequency of indels.

Isolation of Clonal Cell Lines:

- Limited Dilution: 24 hours post-transfection, dilute cells to a density of 0.5-1 cell per well in a 96-well plate.

- Screening: After 2-3 weeks of expansion, screen individual clones for indels by PCR and sequencing of the target locus to identify homozygous or heterozygous knockout clones.

Figure 2: A standard experimental workflow for generating gene knockouts in mammalian cells using CRISPR-Cas9, from sgRNA design to the isolation of validated clonal cell lines.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Cas Experimentation

| Reagent / Solution | Function and Description |

|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Plasmid | A vector (e.g., pSpCas9(BB)) expressing the Cas9 nuclease codon-optimized for the target organism (e.g., human cells) under a constitutive promoter (e.g., CBI). |

| sgRNA Expression Vector | A plasmid (e.g., pX330) containing a U6 promoter for driving the expression of the sgRNA transcript. The target-specific sequence is cloned into this vector. |

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | Highly purified, wild-type or mutant Cas9 protein for forming RNP complexes for delivery, offering high efficiency and reduced off-target effects. |

| Delivery Reagents | Lipofection agents (e.g., Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX) or Electroporation systems (e.g., Neon) for introducing CRISPR components into cells. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Donor Template | A single-stranded or double-stranded DNA template containing the desired edit (e.g., point mutation, epitope tag) flanked by homology arms to the target locus for precise genome editing. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | An enzyme that recognizes and cleaves mismatched base pairs in heteroduplex DNA, used to detect CRISPR-induced mutations. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Library Prep Kits | Kits for preparing sequencing libraries from amplified target loci to enable deep, quantitative analysis of editing outcomes and off-target effects. |

Biotechnological and Therapeutic Applications

The simplicity and programmability of Class 2 systems have unlocked a vast array of applications that extend far beyond simple gene knockout.

Genome and Transcriptome Engineering

- Gene Knockout and Knock-in: The primary application of Cas9 and Cas12 is the introduction of DSBs to disrupt genes or, in the presence of a donor DNA template, to insert new sequences (knock-in) via HDR [12] [16]. This is fundamental for functional genomics and gene therapy.

- Base and Prime Editing: To avoid the pitfalls of DSBs (e.g., genomic instability), "base editors" fuse a catalytically impaired Cas9 (dCas9) or a Cas9 nickase to a deaminase enzyme. Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) convert C•G to T•A base pairs, while Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) convert A•T to G•C, enabling precise single-nucleotide changes without a DSB [12].

- Gene Regulation (CRISPRa/i): A catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9) can be targeted to gene promoters without cutting DNA. By fusing dCas9 to transcriptional activators (CRISPRa) or repressors (CRISPRi), researchers can precisely tune gene expression levels [12].

Diagnostic Applications

- DNA Detection (Cas12): The collateral ssDNase activity of Cas12 is harnessed in diagnostic platforms like DETECTR. Upon recognizing a target DNA sequence (e.g., from a pathogen), activated Cas12 cleaves a reporter molecule, generating a fluorescent signal, enabling rapid and sensitive detection of viruses like HPV [14].

- RNA Detection (Cas13): Similarly, the collateral RNase activity of Cas13 is the engine of the SHERLOCK platform. It allows for the attomolar-level detection of specific RNA sequences, enabling the diagnosis of pathogens like Zika and Dengue viruses, and even genetic mutations [5].

Therapeutic Development and Clinical Impact

Class 2 systems are revolutionizing therapeutic development. In cancer immunotherapy, CRISPR-Cas9 is used to engineer chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells, enhancing their potency and persistence [16]. In gene therapy, clinical trials are underway to correct monogenic disorders such as sickle cell anemia and beta-thalassemia by editing hematopoietic stem cells [12] [16]. The first CRISPR-based therapies have now received regulatory approval, marking a milestone for the field.

The field of Class 2 CRISPR systems continues to evolve rapidly. Current research focuses on discovering novel effectors from the "long tail" of microbial diversity [1], engineering existing effectors for improved specificity and altered PAM recognition, and developing ever-more sophisticated delivery systems for therapeutic applications [12]. A groundbreaking recent direction involves the use of artificial intelligence to design novel CRISPR effectors. Researchers have trained large language models on millions of CRISPR operons to generate entirely new, functional Cas9-like proteins, such as "OpenCRISPR-1," which are highly divergent from any known natural sequence but show comparable or even improved activity in human cells [17]. This AI-driven design bypasses evolutionary constraints and promises to vastly expand the CRISPR toolkit.

In conclusion, Class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems, with their single-protein effector architecture, have provided an unparalleled platform for biotechnology. Their impact spans from basic research to transformative clinical therapies. As the classification of these systems expands and our understanding of their biology deepens, the potential for future innovations in genome engineering, diagnostics, and therapeutics remains immense. The integration of computational design and protein engineering ensures that the biotechnological impact of Class 2 systems will continue to grow for the foreseeable future.

The systematic classification of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins represents a fundamental framework for understanding prokaryotic adaptive immunity and developing genome-editing technologies. The dynamic evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems necessitates regular updates to their classification as new variants are discovered through advanced genomic and metagenomic analyses. The 2025 evolutionary classification, published in Nature Microbiology, marks a significant milestone by expanding the taxonomy to 7 types and 46 subtypes, a substantial increase from the 6 types and 33 subtypes recognized in the 2020 classification [1] [18]. This updated classification encapsulates the remarkable diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems identified in recent years, particularly highlighting rare variants that constitute the "long tail" of the CRISPR-Cas distribution in prokaryotes and their viruses [1] [19].

The expansion reflects more than just numerical increases; it reveals new biological mechanisms and evolutionary relationships. The update includes the newly characterized type VII systems, introduces additional subtypes within existing types, and documents variants with unconventional functionalities such as target DNA cleavage without traditional nuclease activity and replication inhibition without cleavage [1]. This refined taxonomy provides researchers with an updated roadmap for exploring the mechanistic diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems and harnessing their capabilities for biotechnological and therapeutic applications.

Updated Classification Framework: From Classes to Variants

Hierarchical Organization of CRISPR-Cas Systems

The 2025 classification maintains the established hierarchical structure of CRISPR-Cas systems while expanding its categories to accommodate new discoveries. This framework organizes systems based on a combination of evolutionary relationships, gene composition, locus architecture, and mechanistic features [1] [9].

Table 1: CRISPR-Cas Classification Hierarchy

| Classification Level | Definition Basis | 2020 Count | 2025 Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes | Effector complex architecture | 2 | 2 |

| Types | Signature effector gene and interference mechanism | 6 | 7 |

| Subtypes | Gene composition and locus organization | 33 | 46 |

| Variants | Specific domain architectures and functional features | Not specified | Multiple (e.g., I-E2, I-F4, IV-A2) |

The classification continues to divide CRISPR-Cas systems into two fundamental classes based on their effector module organization. Class 1 systems (types I, III, IV, and VII) employ multi-subunit effector complexes, while Class 2 systems (types II, V, and VI) utilize single-protein effectors [1] [9]. Class 1 systems dominate natural environments, comprising approximately 90% of identified CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria and nearly 100% in archaea, yet they have been less utilized in biotechnology compared to Class 2 systems [9].

Quantitative Expansion of CRISPR-Cas Taxonomy

The 2025 update represents the most significant expansion of the CRISPR-Cas classification framework since 2020. The addition of 1 new type and 13 new subtypes reflects accelerated discovery efforts powered by advanced sequencing technologies and sophisticated bioinformatic analyses [1] [18].

Table 2: Updated Classification of CRISPR-Cas Systems (2025)

| Class | Type | Subtypes | Signature Effector | Primary Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | I | A-H (8 subtypes) | Cas3 (helicase-nuclease) | DNA |

| III | A-I (9 subtypes) | Cas10 | DNA/RNA | |

| IV | A-C (3 subtypes) | Csf1 (Cas7-like) | DNA | |

| VII | 1 subtype | Cas14 (metallo-β-lactamase) | RNA | |

| Class 2 | II | A-C (3 subtypes) | Cas9 | DNA |

| V | A-I, U (10 subtypes) | Cas12 | DNA | |

| VI | A-D (4 subtypes) | Cas13 | RNA |

The distribution of systems across these categories is not uniform. Analysis of abundance in genomes and metagenomes reveals that previously defined systems are relatively common, while the newly characterized variants are comparatively rare, comprising the "long tail" of CRISPR-Cas distribution that remains to be fully explored [1] [19].

New Additions to the CRISPR-Cas Taxonomy

Type VII: A Novel Archaeal RNA-Targeting System

The newly designated type VII represents a distinct addition to the CRISPR-Cas landscape. These systems are found predominantly in taxonomically diverse archaeal genomes and are characterized by the Cas14 effector, a metallo-β-lactamase (β-CASP) family nuclease [1] [9]. Type VII loci typically lack adaptation modules and are often associated with CRISPR arrays containing repeats with multiple substitutions, suggesting infrequent incorporation of new spacers [1].

Notably, the Cas14 protein contains a carboxy-terminal domain that structurally resembles the C-terminal domain of Cas10, the large subunit of type III effector modules, suggesting an evolutionary connection between these types [1]. This relationship is further supported by specific similarity between the Cas5 proteins of type VII and subtype III-D systems [1]. Despite being classified as Class 1, type VII effector complexes can be quite large, with cryogenic-electron-microscopy structures revealing up to 12 subunits, with Cas14 binding to the Cas7 backbone via its Cas10 remnant domain [1].

Functionally, type VII systems have been demonstrated to target RNA in a crRNA-dependent manner, with cleavage mediated by the nuclease activity of Cas14 [1]. Analysis of the limited number of spacer hits indicates these systems primarily target transposable elements [1]. The evolutionary trajectory suggests type VII systems likely evolved from type III via a reductive pathway, simplifying while maintaining RNA interference capability.

Expanded Type III Subtypes: III-G, III-H, and III-I

The updated classification introduces three new subtypes within type III systems, all exhibiting features suggestive of reductive evolution [1]:

Subtype III-G: Found in Sulfolobales, these systems contain Csx26 as a signature protein that may replace Cas11 in effector complexes. They lack adaptation modules, and interestingly, no CRISPR array has been found associated with III-G loci, suggesting they may recruit crRNAs from other CRISPR-cas loci in trans [1].

Subtype III-H: Present in various archaea and a few bacterial metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), this subtype features a highly diverged small subunit (Cas11) that appears to have replaced the C-terminal domain of Cas10 [1].

Subtype III-I: Identified in more than 160 genomes in the NCBI non-redundant database, primarily from the phyla Thermodesulfobacteriota and Chloroflexota. This subtype possesses an extremely diverged Cas10 lacking the N-terminal polymerase/cyclase domain and a multidomain protein with architecture resembling Cas7–11 but originating independently from a different variant of subtype III-D [1].

A significant feature shared by subtypes III-G and III-H is the inactivation of the polymerase/cyclase domain of Cas10, indicated by replacement of catalytic amino acids [1]. This correlates with the loss of genes encoding ancillary proteins containing cyclic oligoadenylate (cOA)-binding domains (CARF or SAVED) fused to effector domains, resulting in the loss of the cOA signaling pathway that induces collateral RNase activity in most type III systems [1].

(A simplified evolutionary relationships between Type III subtypes and the novel Type VII, highlighting key fusion events and functional outcomes.)

Novel Variants with Unique Functional Capabilities

Beyond the formal classification updates, researchers have identified multiple variants of class 1 CRISPR-Cas systems with unique domain architectures and functional features [1]. Three notable variants—I-E2, I-F4, and IV-A2—incorporate an HNH nuclease fused to Cas5, Cas8f, and CasDinG proteins, respectively [1]. These variants demonstrate robust crRNA-guided double-stranded DNA cleavage activity, with I-E2 and I-F4 typically lacking the Cas3 helicase-nuclease that is responsible for DNA shredding in canonical type I systems [1].

The updated classification also acknowledges type IV variants that cleave target DNA and type V variants that inhibit target replication without cleavage, expanding the functional repertoire of CRISPR-Cas systems beyond traditional nucleolytic activity [1]. These discoveries challenge conventional boundaries between CRISPR types and suggest a more fluid functional landscape than previously recognized.

Experimental Characterization of Novel CRISPR-Cas Systems

Methodological Framework for System Characterization

The discovery and classification of novel CRISPR-Cas systems relies on integrated computational and experimental approaches. Bioinformatic analyses of genomic and metagenomic datasets identify candidate systems, which subsequently require rigorous experimental validation to determine their molecular mechanisms and biological functions [19] [20].

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods for CRISPR-Cas Characterization

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Application in CRISPR Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Analysis | Sequence similarity clustering, Phylogenetic analysis, Neighborhood analysis | Identification of novel cas genes, Evolutionary relationships, Locus organization |

| Biochemical Characterization | Protein purification, In vitro cleavage assays, EMSA, Size exclusion chromatography | Nuclease activity validation, Target specificity, Complex assembly |

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, DALI structure similarity search | Effector complex architecture, Catalytic mechanism, Evolutionary connections |

| In vivo Functional Assays | Plasmid interference assays, Phage challenge tests, CRISPR array sequencing | Immune function validation, Spacer acquisition efficiency, PAM determination |

The characterization of rare variants often presents technical challenges due to their divergence from well-studied systems and potential requirements for specialized host factors or conditions [20]. Recent protocols have emphasized the importance of investigating non-Cas accessory genes, such as Tn7-like transposons and Pro-CRISPR factors, which may confer additional functionalities to CRISPR systems [20].

Case Study: Characterization of Type VII Systems

The experimental characterization of type VII systems illustrates the comprehensive approach required to validate new CRISPR types. Initial identification through terascale clustering of metagenomic data revealed systems with unique cas gene combinations [1] [9]. Subsequent phylogenetic analysis positioned these systems as distinct from established types while revealing evolutionary connections to type III systems through Cas5 and remnant Cas10 domains [1].

Biochemical validation included recombinant expression and purification of the effector complex components, followed by in vitro cleavage assays demonstrating Cas14-mediated, crRNA-dependent RNA targeting [1]. Structural analysis via cryo-EM elucidated the architecture of the type VII effector complex, revealing its multi-subunit composition and the binding mode of Cas14 to the Cas7 backbone [1]. Functional assessment in native or model hosts confirmed interference against natural targets, particularly transposable elements [1].

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas Characterization

The experimental characterization of novel CRISPR-Cas systems requires specialized reagents and methodologies. The following table summarizes key resources for researchers investigating diverse CRISPR systems.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas System Characterization

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Recombinant protein production | E. coli expression systems; optimization for multi-subunit Class 1 complexes |

| Guide RNA Scaffolds | crRNA and tracrRNA design | Synthetic guides for testing targeting specificity; modified bases for stability |

| Reporter Assays | Functional validation | Fluorescent reporters for DNA/RNA cleavage; plasmid interference assays |

| Phage/Bacterial Models | In vivo immunity testing | Phage challenge assays; transformation efficiency tests |

| Structural Biology Platforms | Molecular architecture determination | Cryo-EM for large Class 1 complexes; X-ray crystallography for individual domains |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Sequence analysis and classification | Custom pipelines for cas gene identification; phylogenetic analysis software |

| Metagenomic Databases | Novel system discovery | IMG/M, NCBI WGS; specialized databases for extreme environments |

Advanced delivery systems, including viral vectors and lipid nanoparticles, have become crucial for testing CRISPR systems in eukaryotic contexts, potentially expanding their therapeutic applications [21]. The development of standardized protocols for protein purification and functional characterization has accelerated the validation of novel systems [20].

(The iterative experimental workflow for characterizing novel CRISPR-Cas systems, from computational identification to functional validation and final classification.)

Implications and Future Directions

Evolutionary Insights from the Updated Classification

The expanded classification reveals fascinating patterns in CRISPR-Cas evolution, particularly regarding the emergence of complex systems through gene fusion and simplification through reductive evolution. The identification of type VII systems with their Cas10-derived domains suggests an evolutionary connection to type III systems, possibly representing a simplified descendant that has maintained RNA-targeting capability while losing DNA interference and signaling functions [1].

Similarly, the discovery of the III-I subtype effector protein Cas7-11i, which resembles the Cas7-11 effector of III-E systems but originated independently from a different III-D variant, provides a striking example of convergent evolution in CRISPR-Cas systems [1]. These patterns underscore the modular nature of CRISPR systems and the evolutionary plasticity that enables functional diversification.

Analysis of the abundance distribution of CRISPR-Cas variants shows that newly characterized systems are generally rare compared to previously defined systems [1]. This "long tail" of the CRISPR-Cas distribution represents an extensive reservoir of molecular diversity that remains largely unexplored. Future discoveries will likely continue to fill in this distribution, potentially revealing new types and subtypes with unique properties.

Biotechnological and Therapeutic Applications

The expanding diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems provides an increasingly rich toolkit for biotechnology and medicine. Rare variants with unique properties—such as unconventional PAM requirements, distinct cleavage patterns, or novel targeting specificities—offer solutions to current limitations in genome editing applications [19] [21].

Type VII systems with their RNA-targeting capability join the arsenal of CRISPR tools for transcriptome engineering, potentially offering advantages over existing RNA-targeting systems like Cas13. The compact size of some newly discovered effectors may facilitate delivery for therapeutic applications, a significant challenge in clinical translation of CRISPR technologies [21].

The characterization of type IV variants that cleave DNA and type V variants that inhibit replication without cleavage expands the functional repertoire available for synthetic biology and therapeutic development [1]. These systems enable more precise interventions than traditional nucleases, potentially reducing off-target effects and enabling new classes of genetic control.

The updated classification serves not only as a taxonomic framework but as a roadmap for biotechnology development, highlighting underutilized natural systems that may provide the foundation for next-generation genome engineering tools. As characterization efforts continue, particularly for the rare variants that constitute most of the diversity, the practical applications of CRISPR technology will continue to expand into new domains of research and therapy.

Evolutionary Relationships and the 'Long Tail' of Rare CRISPR Variants

CRISPR-Cas systems represent adaptive immune mechanisms in bacteria and archaea that have revolutionized modern genome engineering. The evolutionary classification of these systems is essential for accurate annotation of CRISPR-cas loci in newly sequenced genomes and metagenomes, forming a critical foundation for both basic research and biotechnological applications [1]. The known diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems continues to expand rapidly through concerted database mining efforts, revealing previously unrecognized variants and functionalities. This whitepaper examines the updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems, with particular emphasis on the "long tail" of rare variants that represent an untapped reservoir of molecular tools and biological insights.

The current classification, updated in 2025, now encompasses 2 classes, 7 types, and 46 subtypes, representing a significant expansion from the 6 types and 33 subtypes recognized just five years prior [1] [13]. This expansion reflects both the increasing sophistication of bioinformatic discovery tools and growing recognition of the extensive natural diversity of CRISPR-Cas systems. The newly characterized variants are comparatively rare, comprising the long tail of the CRISPR-Cas distribution in prokaryotes and their viruses, and most remain to be characterized experimentally [1]. This technical guide provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for understanding these evolutionary relationships and their implications for fundamental science and therapeutic development.

Updated Classification Framework: From Two Classes to Forty-Six Subtypes

Hierarchical Organization of CRISPR-Cas Systems

The classification of CRISPR-Cas systems employs a polythetic approach that combines analyses of signature protein families with features of cas locus architecture to partition systems into distinct classes, types, and subtypes [1] [22]. This evolutionary classification reflects phylogenetic relationships while accommodating the modular nature and frequent rearrangements of CRISPR-cas loci.

Table: Updated CRISPR-Cas Classification Hierarchy (2025)

| Classification Level | Previous System (2020) | Updated System (2025) | Key Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes | 2 | 2 | No change at class level |

| Types | 6 | 7 | Addition of Type VII |

| Subtypes | 33 | 46 | 13 new subtypes added |

At the highest level, CRISPR-Cas systems are divided into two fundamental classes based on their effector module organization. Class 1 systems utilize multi-subunit effector complexes, while Class 2 systems employ single, large effector proteins [23] [5]. This fundamental distinction correlates with significant differences in crRNA processing mechanisms and overall system complexity.

Table: Distribution of Subtypes Across CRISPR-Cas Types

| Class | Type | Number of Subtypes | Signature Effector | Target Nucleic Acids |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | I | 8 | Cas3 | DNA |

| III | 9 | Cas10 | DNA/RNA | |

| IV | 3 | Variant-specific | DNA | |

| VII | 1 | Cas14 | RNA | |

| Class 2 | II | Multiple (not specified) | Cas9 | DNA |

| V | Multiple (not specified) | Cas12 | DNA | |

| VI | Multiple (not specified) | Cas13 | RNA |

Distinct Features of Class 1 Systems

Class 1 systems, which constitute approximately 90% of all CRISPR loci in bacteria and archaea, display remarkable structural and functional diversity [5]. Recent discoveries have expanded our understanding of several type-specific variations:

Type I systems encompass eight subtypes, all sharing the signature Cas3 protein which possesses helicase and nuclease activities responsible for target DNA degradation [1] [5]. Recent work has identified unique variants such as I-E2 and I-F4 that incorporate HNH nucleases fused to Cas5 and Cas8f proteins, respectively [1]. These variants typically lack the Cas3 helicase-nuclease and have demonstrated robust crRNA-guided double-stranded DNA cleavage activity [1].

Type III systems now include nine subtypes, with signatures encoded by the cas10 gene [1]. Newly described subtypes III-G (Sulfolobales-specific), III-H (found in diverse archaea and bacterial MAGs), and III-I (present in over 160 genomes, mostly from Thermodesulfobacteriota and Chloroflexota) show features suggestive of reductive evolution [1]. These subtypes often display inactivated polymerase/cyclase domains in Cas10 and have lost the associated cOA signaling pathway that induces collateral RNase activity in most type III systems [1].

Type IV systems, previously considered "putative" with limited characterization, now include variants demonstrated to cleave target DNA, expanding their functional repertoire [1].

Type VII represents a newly added type with systems found mostly in taxonomically diverse archaeal genomes [1]. These systems contain a metallo-β-lactamase (β-CASP) effector nuclease designated Cas14, which qualifies these loci as a new type according to classification principles [1]. Type VII loci lack adaptation modules and associated CRISPR arrays often contain multiple substitutions, suggesting infrequent incorporation of new spacers [1]. Analysis of limited spacer hits indicates these systems target transposable elements [1].

Evolutionary Connections Between Types

Structural and phylogenetic analyses reveal evolutionary connections between different CRISPR-Cas types. Type VII systems appear to have evolved from type III via a reductive pathway, as evidenced by the C-terminal domain of Cas14 that structurally resembles the C-terminal domain of Cas10, the large subunit of type III effector modules [1]. This connection is further supported by specific similarity between the Cas5 proteins of type VII and subtype III-D [1]. The recently solved cryo-EM structure of the type VII effector complex contains up to 12 subunits, with Cas14 binding to the Cas7 backbone via its Cas10 remnant domain, making it one of the largest among class 1 systems [1].

Diagram Title: Updated CRISPR-Cas Classification Hierarchy

The 'Long Tail' of Rare CRISPR-Cas Variants

Characteristics and Distribution of Rare Variants

Analysis of CRISPR-Cas variant abundance in genomes and metagenomes reveals a striking distribution pattern: previously defined systems are relatively common, while more recently characterized variants are comparatively rare [1]. These low-abundance variants comprise what researchers term the "long tail" of CRISPR-Cas distribution in prokaryotes and their viruses [1]. The discovery of these rare variants highlights that the most prevalent CRISPR-Cas systems may already be known, but significant diversity remains to be characterized in the less frequent systems.

Table: Features of Recently Characterized Rare CRISPR-Cas Variants

| Variant | Abundance | Key Features | Biological Source | Functional Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type VII | Rare | Cas14 effector with β-CASP nuclease; targets RNA; evolved from Type III | Diverse archaea | Experimental characterization ongoing |

| Subtype III-G | Rare | Inactivated Cas10 polymerase/cyclase; lacks cOA signaling; no CRISPR array found | Sulfolobales | Predicted DNA targeting |

| Subtype III-H | Rare | Highly diverged Cas11; inactivated Cas10 polymerase/cyclase | Various archaea and bacterial MAGs | Predicted DNA cleavage |

| Subtype III-I | Rare | Extremely diverged Cas10; Cas7-11i effector protein | >160 genomes (Thermodesulfobacteriota, Chloroflexota) | Predicted RNA cleavage |

| Type IV variants | Rare | Demonstrated DNA cleavage activity | Not specified | Experimental validation |

| Type V variants | Rare | Inhibits target replication without cleavage | Not specified | Experimental validation |

Evolutionary Origins of Rare Variants

The rare variants in the CRISPR-Cas long tail appear to have emerged through multiple evolutionary processes:

Reductive evolution is evident in several rare subtypes, particularly in type III and the newly described type VII systems [1]. This process involves simplification of system architecture, including loss of functional domains and entire modules. For example, subtypes III-G and III-H show inactivated polymerase/cyclase domains in Cas10 and have lost associated genes encoding ancillary proteins with cOA-binding domains [1]. Similarly, type VII systems lack adaptation modules and may recruit crRNAs from other CRISPR-cas loci in trans [1].

Module shuffling and fusion represents another significant evolutionary mechanism. The subtype III-I effector module demonstrates this process through its Cas7-11i protein, which contains three fused Cas7 domains and a Cas11 domain, resembling the architecture of subtype III-E's Cas7-11 but apparently originating independently from a different variant of subtype III-D [1]. This independent convergence on similar architectural solutions highlights the modular nature of CRISPR-Cas systems and the evolutionary potential for creating new functionalities through domain rearrangement.

Horizontal gene transfer continues to play a crucial role in distributing rare variants across taxonomic boundaries, as evidenced by the patchy distribution of systems like type VII across diverse archaeal lineages [1]. The analysis of mobile genetic elements has revealed multiple contributions to the origin of various CRISPR-Cas components, with different biological systems that function by genome manipulation having evolved convergently from unrelated mobile genetic elements [23].

Methodological Approaches for Characterizing Rare Variants

Computational Discovery and Classification

The identification and classification of rare CRISPR variants relies on sophisticated bioinformatic pipelines that combine multiple computational approaches:

CRISPR array detection utilizes tools such as CRISPRDetect, which automatically detects, predicts, and refines CRISPR arrays in genomes with precise determination of array orientation, repeat-spacer boundaries, and sequence variations [24]. Comparative analyses show that CRISPRDetect demonstrates higher sensitivity than earlier tools like PILER-CR and CRT, identifying hundreds of additional arrays in genomic datasets [24].

Machine learning-enhanced identification is implemented in tools like CRISPRidentify, which employs multiple classifier approaches (Support Vector Machine, K-nearest Neighbors, Naive Bayes, Decision Tree, Fully Connected Neural Network, Random Forest, and Extra Trees) to distinguish genuine CRISPR arrays from false positives with significantly lower false positive rates compared to other methods [24]. This tool addresses common issues in CRISPR identification, including arrays with identical spacers, through focused analysis of spacer similarity.

Cas gene annotation and classification leverages Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles derived from known Cas proteins to identify and type associated Cas genes [24]. Integrated platforms like CRISPRminer and CRISPRBank combine multiple prediction algorithms to identify both CRISPR arrays and Cas genes, classifying systems into defined types and identifying self-targeting regions [24].

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Characterizing Rare Variants

Experimental Characterization Protocols

Once identified computationally, rare CRISPR variants require rigorous experimental validation to determine their molecular mechanisms and biological functions:

Effector complex reconstitution involves heterologous expression of candidate Cas genes in model systems like E. coli, followed by protein purification using affinity chromatography tags [1]. For multi-subunit Class 1 effectors, this may require co-expression of multiple subunits or individual expression followed by in vitro assembly. Successful complex formation is typically verified by size exclusion chromatography and native mass spectrometry.

crRNA processing assays determine whether the system can process precursor crRNA into mature guide RNAs. These experiments involve incubating synthetic pre-crRNA with purified effector complexes or individual Cas proteins under appropriate buffer conditions, followed by analysis of cleavage products using denaturing urea-PAGE and northern blotting [22].

Target nucleic acid cleavage profiling evaluates the interference capabilities of the system against potential DNA or RNA targets. Standard protocols include electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) to assess binding and cleavage assays with fluorophore-quencher labeled substrates or radiolabeled targets to characterize cleavage kinetics and specificity [1]. For DNA-targeting systems, plasmid cleavage assays can provide initial functional validation.

Structural characterization using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography has been instrumental in understanding the molecular architecture of rare variants. For example, the cryo-EM structure of the type VII effector complex revealed its multi-subunit organization with up to 12 subunits and detailed the interaction between Cas14 and the Cas7 backbone via its Cas10 remnant domain [1]. Structural analysis also enables identification of catalytic residues and mechanistic insights.

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Characterization

Table: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Variant Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | CRISPRDetect, CRISPRidentify, CRISPRminer | CRISPR array prediction and validation |

| Cas Gene Annotation | HMM profiles, CRISPR-Casdb, CRISPI | Identification and classification of Cas proteins |

| Expression Systems | E. coli BL21(DE3), insect cell systems, mammalian HEK293 | Heterologous protein expression |

| Purification Tags | His-tag, GST-tag, MBP-tag | Protein purification via affinity chromatography |

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM grids, crystallization screens | Determining molecular structures |

| Nucleic Acid Assays | Fluorophore-quencher substrates, radiolabeled nucleotides | Cleavage kinetics and specificity profiling |

| Cell-Based Assays | Reporter constructs, transformation assays | Functional validation in cellular contexts |

Research Implications and Future Directions

Fundamental Evolutionary Insights

The expanded classification of CRISPR-Cas systems, particularly the discovery of rare variants, provides fundamental insights into evolutionary processes:

Modular evolution is evident in the exchange and recombination of functional modules between different CRISPR-Cas types and subtypes [22]. The presence of similar domains in different architectural contexts, such as the Cas10 remnant domain in type VII Cas14, demonstrates how molecular evolution repurposes functional units to create new systems [1].

Lamarckian evolution is embodied in CRISPR-Cas systems, which modify the host genome in direct response to environmental challenges (virus infections) and transmit this acquired immunity to progeny [23]. The rare variants in the long tail represent evolutionary experiments in expanding the capabilities of this adaptive immune system.

Reductive evolution appears to be a common pathway for the emergence of specialized systems, as seen in type VII and subtypes III-G, III-H, and III-I, which have lost various components present in their proposed evolutionary predecessors [1]. This simplification process may create systems with specialized functionalities that operate under specific biological contexts.

Biotechnological and Therapeutic Applications

The characterization of rare CRISPR variants holds significant promise for expanding the genome engineering toolkit:

Novel editing capabilities may be discovered among the rare variants, particularly those with unique cleavage specificities or target preferences. For example, type V variants that inhibit target replication without cleavage represent a potentially new class of genetic manipulation tools [1]. Similarly, type IV variants with demonstrated DNA cleavage activity expand the range of available nucleases [1].

Diagnostic applications could be enhanced through the characterization of rare variants like type VII systems with their RNA-targeting Cas14 effector [1]. The discovery of additional RNA-targeting systems could complement existing CRISPR diagnostics like SHERLOCK which utilizes Cas13 [5].

Safety considerations in therapeutic applications must account for the potential of large structural variations including chromosomal translocations and megabase-scale deletions, particularly in cells treated with DNA-PKcs inhibitors to enhance HDR efficiency [25]. Understanding the cleavage mechanisms and repair outcomes of both common and rare CRISPR systems is essential for developing safer genome editing therapies.

The updated classification of CRISPR-Cas systems reveals both the extensive diversity that has been characterized to date and the substantial remaining unknown territory represented by the long tail of rare variants. As computational tools improve and more diverse genomes and metagenomes are sequenced, additional rare variants will undoubtedly be discovered and characterized, further expanding our understanding of prokaryotic adaptive immunity and providing new molecular tools for biotechnology and medicine.

Signature Proteins and Genetic Markers for Type Identification

The systematic classification of CRISPR-Cas systems is fundamental to both understanding bacterial adaptive immunity and repurposing these systems for biotechnological applications. Current classification organizes these systems into two classes based on their effector module architecture, which are further subdivided into 7 types and 46 subtypes based on signature protein sequences, cas gene composition, and locus architecture [1]. This classification framework provides researchers with a critical roadmap for identifying novel systems and selecting appropriate tools for specific applications, from gene editing to diagnostic platforms.

The evolutionary diversification of CRISPR-Cas systems has resulted in distinct molecular signatures that serve as reliable markers for type identification. This guide provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers engaged in the characterization of CRISPR-Cas systems, with detailed information on signature proteins, experimental methodologies for identification, and essential research tools.

Core Classification Framework and Signature Proteins

Hierarchical Organization of CRISPR-Cas Systems

CRISPR-Cas systems follow a hierarchical classification structure that progresses from broad architectural principles to specific genetic signatures:

- Class 1 systems utilize multi-subunit effector complexes and comprise approximately 90% of CRISPR loci found in bacteria and archaea [5]. These include types I, III, IV, and the newly characterized type VII.

- Class 2 systems employ single, large effector proteins for interference and represent approximately 10% of identified systems, found exclusively in bacteria [5]. These include types II, V, and VI.

The continuous discovery of novel variants has expanded the classification framework significantly, with the current system encompassing 7 types and 46 subtypes compared to the 6 types and 33 subtypes documented five years ago [1]. This expansion reflects the extensive diversity within prokaryotic defense systems and highlights the importance of updated classification standards.

Signature Proteins by CRISPR-Cas Type

Table 1: Signature Proteins and Genetic Markers for CRISPR-Cas Type Identification

| Type | Class | Signature Protein(s) | Key Genetic Markers | Target Substrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1 | Cas3 (helicase-nuclease) [5] | Cas5, Cas6, Cas7, Cas8 family proteins [1] | DNA [5] |

| II | 2 | Cas9 [5] | tracrRNA requirement [5] | DNA [5] |

| III | 1 | Cas10 (polymerase/cyclase domain) [1] [5] | Cas5, Cas6, Cas7, CARF or SAVED domains in ancillary proteins [1] | DNA/RNA [5] |

| IV | 1 | DinG (in type IV-A2) [1] | Minimal effector complex, often lacks adaptation modules [1] [5] | DNA [1] |

| V | 2 | Cas12 (including Cas12a, Cas12f) [26] [5] | RuvC-like domain, tracrRNA requirement in some subtypes [5] | DNA [5] |

| VI | 2 | Cas13 [5] | Two HEPN domains for RNase activity [27] | RNA [5] |

| VII | 1 | Cas14 (metallo-β-lactamase/β-CASP nuclease) [1] | Cas7, Cas5, Cas10 remnant domain in Cas14 [1] | RNA [1] |

Table 2: Characteristic Features of Newly Classified and Rare Subtypes

| Subtype | Parent Type | Distinguishing Features | Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|

| III-G | III | Csx26 signature protein, inactivated Cas10 polymerase/cyclase domain [1] | Rare (Sulfolobales-specific) [1] |

| III-H | III | Highly diverged Cas11, inactivated Cas10 polymerase/cyclase domain [1] | Rare (various archaea and bacterial MAGs) [1] |

| III-I | III | Cas7-11i effector protein, extremely diverged Cas10 lacking N-terminal domain [1] | Rare (>160 genomes in NCBI NR database) [1] |

| I-E2 | I | HNH nuclease fused to Cas5, lacks Cas3 [1] | Rare [1] |

| I-F4 | I | HNH nuclease fused to Cas8f, lacks Cas3 [1] | Rare [1] |

| IV-A2 | IV | HNH nuclease fused to CasDinG [1] | Rare [1] |